1. Introduction

Access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy is indispensable for economic development (World Bank, 2018). The inclusive growth literature emphasises the crucial role of electricity access in human capital development (Banerjee et al., 2021), entrepreneurship (Pueyo et al., 2020), economic growth (Adom et al., 2021), and equitable income distribution (Adams et al., 2024). Recent evidence also suggests that the socioeconomic impacts of energy equity transcend economic growth to include environmental sustainability (see, e.g., Ofori et al., 2024; Sovacool, 2012).

This study contributes to this emerging body of scholarly discourse by investigating the impact of distributional energy justice (defined as rural-urban equality in electricity access irrespective of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or political affiliation) on inclusive human development in Africa. This conceptualisation builds on prior research on Africa that fails to account for locational disparities in electricity access. The main argument underpinning this empirical scrutiny is that progress in distributional energy justice (hereafter: energy justice) can foster fairer outcomes across three fundamental pillars of human development: education, health, and income.

Two significant developments motivate our focus on energy justice and inclusive human development (IHDI). First, according to UNDP (2023) data, Africa reports the lowest IHDI compared to other continents. Notably, the current IHDI score for Africa (0.448) is conspicuously lower than that of Europe (0.815), Asia (0.511), Oceania (0.736), North America (0.830), and Latin America and the Caribbean (0.667). Second, Africa remains the continent with the highest levels of energy poverty and insecurity, with over 600 million people lacking access to electricity (IEA, 2024). In this context, energy justice can promote IHDI in several ways. From the income generation perspective of IHDI, it can be impactful by facilitating open innovation, entrepreneurship, and firm performance (Pueyo et al., 2020; Geginat & Ramalho, 2018). Energy justice can, thus, be transformative in spurring growth (Stern et al., 2019) and lifting millions of people out of poverty in Africa.

Energy justice can also play a critical role in human capital development. Particularly in low-income African households, it can free up resources to invest in education by reducing both the time and financial burdens associated with using unclean fuels (e.g., firewood, charcoal, and crop residue). Additionally, energy justice can expand access to quality education, regardless of location, by facilitating distance learning, promoting effective teacher-student interaction, and enabling productive practical sessions. The role of energy justice in creating a modern learning environment through adequate lighting, internet connectivity, and access to digital resources is also documented in the literature (see e.g., Armey & Hosman, 2016).

Energy justice can also prolong life expectancy by reducing indoor and outdoor air pollution. Research suggests that access to modern electricity can lessen healthcare burden and premature mortalities by decreasing respiratory diseases and health risks, such as cataracts, heart attacks, miscarriages, and infant mortality (Ajide et al., 2023; Youssef et al., 2015). Gains in this direction can be lifesaving, as per information from Fisher et al. (2021), which indicates that over 1 million people in Africa die annually from air pollution alone. Additionally, energy justice can enable healthcare providers to deliver quality healthcare through proper cold-chain vaccine storage, blood banking, heating, and effective utilisation of medical devices (Banerjee et al., 2021).

Notwithstanding, we argue that an empirical scrutiny concerning the role of energy justice in IHDI in developing countries should also consider the level of climate change readiness (hereafter referred to as climate readiness). Climate readiness refers to a country’s institutional and infrastructural capacity to leverage investments and convert them into effective adaptation solutions (Adger et al., 2015). That is, in countries with high climate vulnerability, such as those in Africa, institutional proactiveness and infrastructural capacity enable all to navigate socioeconomic and environmental shocks.

1 This suggests that countries with high social, economic, or governance readiness capacity are more likely to cushion their citizens to leverage incentives such as energy justice to promote IHDI. For instance, governance readiness, in the form of regulatory efficiency and political stability, can promote and/or safeguard businesses, infrastructure, and livelihoods (Fay, 2012). This way, climate readiness can sustain progress in IHDI by mitigating the vulnerability of enterprises, healthcare systems, and educational systems to extreme events. Social readiness dynamics, including technological innovation and digital infrastructure, can also enhance livelihoods while promoting inclusiveness, empowerment, and pollution abatement (Lybbert & Sumner, 2012; Adger et al., 2009). Similarly, economic readiness channels such as business freedom can complement energy justice to promote IHDI through private-sector competition, innovation, employment, and access to eco-friendly technologies (Ofori et al., 2023).

Reviewing the energy justice and economic development literature on Africa, we identify three knowledge and policy gaps. First, previous studies have not examined the effect of energy justice on IHDI. The few empirical contributions that explore the impacts of energy justice focus on economic growth (Opoku & Acheampong, 2023) and environmental quality (Ofori et al., 2024). Instead, the literature is inundated with studies investigating the impact of energy access, energy burden or energy insecurity on development outcomes such as education, income, health, and human development (see e.g., Ajide et al., 2023; Adom et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Banerjee et al., 2021; Acheampong et al., 2021; Sarkodie & Adams, 2020; Ouedraogo, 2013). Second, to our knowledge, no study has examined how climate readiness (disaggregated into social, economic, and governance aspects) moderates the relationship between energy justice and HDI in Africa. Adopting a holistic view of climate readiness is imperative for comprehensive analysis, as low-income African countries, relative to their high-income counterparts, report glaring frailties in institutional and infrastructural capacity for climate change mitigation and adaptation (see, e.g., Sarkodie & Strezov, 2019; Chen et al., 2015). Thus, failure to capture these climate-specific dynamics can mask nuances in the relationship between energy justice and IHDI. Third, the question of whether the conditional effect of energy justice on IHDI differs across low- and high-income African countries remains unexplored. To address these gaps, this study pursues the following research objectives:

What is the impact of energy justice on IHDI in Africa?

How does climate readiness condition the impact of energy justice on IHDI in Africa?

Does the conditional effect of energy justice on IHDI differ between low- and high-income African countries?

To this end, we employ macro data for 36 African countries for the analysis. Robust evidence from the data analysis reveals that energy justice promotes IHDI, with notable impacts in high-income African countries. The findings further demonstrate that the contingency effect of climate readiness within the energy justice and IHDI nexus is nuanced. Specifically, while economic and governance readiness augment the IHDI-enhancing effects of energy justice, social readiness undermines this impact. The sensitivity analysis also suggests that the joint effect of energy justice and climate readiness on IHDI is striking in high-income African countries.

Through these findings, we make three clear contributions to the economic development literature. First, we contribute to policy formulation by demonstrating that enhancing energy justice is critical in reducing inequalities in income, life expectancy, and education. Policy-wise, our evidence underscores the importance of equitable electricity access in achieving Aspiration 1.1 of Africa’s Agenda 2063, which seeks to enhance access to employment, human capital development, and improved life expectancy for all. Within the remit of SDG 7, this study presents evidence to inform policymaking on the crucial role of energy equity in socioeconomic sustainability.

Second, we advance the energy and development literature by examining the contingent effects of three climate readiness domains, economic, social, and governance, on the relationship between energy justice and IHDI. Our evidence highlights the non-linear impact of energy justice on IHDI across low- and high-income African countries. We support policymaking in this regard by revealing that deficits in social readiness in low-income countries undermine the IHDI gains from energy justice. This is imperative for targeted policy recommendations given that high-income African countries have better infrastructure, including energy systems, and institutional capacity for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

We structure the remainder of this study as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature on energy justice, climate readiness and IHDI, while

Section 3 presents the research methods. We present the findings in

Section 4 and conclude with some policy recommendations in

Section 5.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Energy Justice in Inclusive Human Development

In the context of social justice, distributional energy justice is widely recognised as a critical driver of economic development. (McCauley & Heffron, 2018; McCauley et al., 2013). According to Sovacool and Dworkin (2015), energy justice refers to a global energy system that equitably distributes the benefits and burdens of energy production and services, while ensuring inclusive participation in decision-making processes. Energy justice, therefore, denotes equitable access to energy services regardless of race, geography, gender, political affiliation, or socioeconomic status (McCauley et al., 2013). In highly informal and marginalised societies such as those of Africa, fairness in energy services can yield multidimensional benefits, for instance, by improving health outcomes, expanding labour market participation, and fostering the development of knowledge and skills essential for long-term prosperity.

On the empirical front, a review of the economic development literature reveals a notable gap, with only a handful of studies examining the influence of energy justice on development outcomes within the African context. Indeed, only Opoku and Acheampong (2023) have demonstrated that energy justice has a significant impact on economic growth in Africa. Instead, most studies focus on the role of energy access/poverty in human development, or their impact on income, health, and education, without addressing within-country inequalities in these outcomes. For instance, Acheampong et al. (2021) assess the impact of electricity access on human development using a panel of 79 countries. The authors present evidence based on instrumental variable regression to establish that access to electricity promotes human development. The analysis reveals distinct regional patterns, with electricity access promoting human development in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, yet having a detrimental effect in South Asia. The study attributes the negative impact on the latter to the region’s high reliance on traditional fuels. Similarly, Ouedraogo (2013) analyses the energy access and human development nexus in 15 developing countries from 1998 to 2008. The study finds that electricity consumption enhances human development, concluding that access to energy can be a key pathway to promoting the quality of life in developing countries.

In Ghana, a comprehensive study by Adom et al. (2021) highlights the multifaceted role of energy access in wellbeing. The authors reveal that energy poverty reduces per capita income growth, education, employment, and life expectancy while positively influencing income poverty, inequality, and the risk of drinking unsafe water. Ajide et al. (2023) confirm the conclusion of Adom et al. (2021) with data from 45 African economies over the period 2001-2018. Results from the dynamic generalised method of moments indicate that energy poverty reduces life expectancy but increases infant mortality rates and per capita health expenditure.

In a global study comprising 68 countries, Lee et al. (2022) find that energy security widens (narrows) the income gap of countries in their early (advanced) stages of development. This evidence is corroborated by Song et al. (2023), who demonstrate that access to electricity reduces income inequality in 77 developing countries. Youssef et al. (2015) also contribute to the discourse by examining the effect of electricity consumption on infant mortality and life expectancy in 16 African countries. The findings show that electricity consumption reduces (increases) infant mortality (life expectancy). Banerjee et al. (2021) also analysed the effects of energy use and electricity access on health and education using a sample of 50 developing countries. The authors find that access to electricity improves health and educational outcomes. These findings have been established in Honduras, Vietnam, and India by Squires (2015), Khandker et al. (2013) and Ahmad et al. (2014), respectively. Studies using microdata also demonstrate that access to electricity drives entrepreneurship, firm performance, education, and good health (see, e.g., Pueyo et al., 2020; Bridge et al., 2016; Vernet et al., 2019; de Groot et al., 2017).

A section of the extant literature also finds a negative or no significant impact of energy access/poverty on human development. For instance, Van Tran et al. (2019), through a panel study of 90 countries from 1990 to 2014, conclude that energy consumption has no statistically significant impact on human development in developing economies. Similarly, Ahmed and Azam (2016) find robust evidence that energy consumption has no significant impact on economic growth in 36 countries (comprising 15 high-income OECD, 2 high-income non-OECD, 14 middle-income and 5 low-income countries). Apergis and Payne (2010) also document an adverse effect of energy consumption on economic growth in the case of 9 South American countries from 1980 to 2005.

The literature review reveals two key insights regarding the impact of energy justice on human development. First, most prior studies measure energy justice using indicators such as energy access or energy poverty, but often fail to account for disparities in electricity access across the rural-urban divide. Second, the few studies that incorporate distributional equity to capture energy justice do not employ the inclusive human development index (i.e., the inequality-adjusted human development index) as the outcome variable (see e.g., Ofori et al., 2024; Opoku & Acheampong, 2023).

The focus on inclusive human development as the response variable builds on prior studies that capture economic development through composite measures, such as the Human Development Index, or individual outcomes, including economic growth, income inequality, infant mortality, and poverty. According to UNDP (2022), the index offers a more comprehensive assessment by accounting for within-country inequalities across its three core dimensions: income, education, and health. Specifically, the IHDI adjusts the average achievement in each dimension to reflect its distribution among the population, thus providing a clearer picture of inclusive development.

2.2. The Moderating Role of Climate Change Readiness

The political economy literature emphasises the role of social overhead capital and institutional quality in economic development (Mikulewicz & Taylor, 2020; Acemoglu, 2005). In the context of human development, climate change readiness is regarded as a crucial strategy for building resilience, protecting developmental gains, and fostering sustainable and inclusive progress for both present and future generations. Climate readiness is, therefore, viewed as a compensating (complementary) mechanism for consolidating gains (mitigating harms) in the energy transition. This notion is ingrained in resilience theory, which emphasises building climate-adaptive capacities to cushion societies against socioeconomic shocks, of which climate shocks remain impactful in developing countries (Moench, 2018; Pelling, 2010). At the heart of this theory lies the importance of proactive institutions that continuously monitor, assess, and refine strategies to improve living conditions for everyone amid climate change (Rodima-Taylor, 2012; Adger et al., 2009). In this context, governance readiness, which encompasses regulatory quality, political stability, corruption control, and the rule of law, as well as economic readiness, measured by the ease of doing business, emerges as a crucial factor in shaping the impact of energy justice on HDI. For example, economic readiness can foster business and investment freedom, enabling economic agents across all regions to access electricity for health, education, and labour market activities.

A related concept is social learning theory, which emphasises the role of social interactions and knowledge-sharing in climate change mitigation and human development (Bandura & Walters, 1977, 1966). This theory recognises the role of infrastructural quality in adapting to and mitigating the impacts of climate change. This way, social readiness mechanisms such as digital and educational infrastructure can support countries in climate readiness by deepening knowledge exchange, facilitating collaboration, and fostering stronger networks of stakeholders (Hallegatte et al., 2019). Therefore, societies that are socially prepared are better equipped to use energy access as a means to advance fairness in education, healthcare, and workforce inclusion.

Upon reviewing the socioeconomic sustainability literature, we find that studies linking climate readiness to economic development in developing countries primarily focus on outcomes such as economic growth, income inequality, food insecurity, employment, and poverty. For example, Adom and Amoani (2021) use instrumental variable regression with data from 44 African countries (2006–2016) to analyse whether climate readiness moderates the impact of climate change on economic growth. The study reveals that climate change, as measured by temperature, hampers economic growth and productivity; however, these adverse effects are mitigated as countries strengthen their climate adaptation capacities.

In North Africa, Schilling et al. (2020) investigated the impact of climate change vulnerability on water availability and agricultural productivity, finding that higher vulnerability (indicating lower climate readiness) exacerbates social instability by intensifying water stress and reducing agricultural productivity. Wens et al. (2022) also contribute to the discourse by revealing that social readiness factors (financial aid and climate change awareness) improve the food security, income, and financial stability of smallholder farmers in Kenya. Expanding the scope, Sarkodie et al. (2022) examine the effects of climate change vulnerability on ecosystem services, food security, health, human habitats, infrastructure, and water resources, while considering the moderating role of climate readiness. Their findings indicate that although climate change vulnerability hampers progress across these sectors, countries with strong social, governance, and economic readiness capacities experience significantly reduced impacts.

Cevik and Jalles (2023) examine the impact of climate vulnerability on income inequality across 158 developing and advanced countries. Their results indicate that climate vulnerability exacerbates inequality in developing countries, while its effect is insignificant in advanced economies. The authors attribute this difference to the stronger climate adaptation and mitigation capacities in developed countries. Similarly, Burke et al. (2015) demonstrate that climate vulnerability hampers economic growth in developing economies. However, the effect is not statistically significant in developed countries due to their robust institutional frameworks for managing climate risks.

It is evident from the literature survey that previous studies have not explored the effect of climate readiness on inclusive human development in Africa. Additionally, prior studies have not examined the moderating role of climate readiness (disaggregated into social, economic, and governance readiness) in the relationship between energy justice and inclusive human development. Finally, whether the conditional effect of climate readiness differs across low- and high-income African countries remains unexplored. This study bridges these gaps by employing the empirical strategy detailed in the next section.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Data and Justification for the Inclusion of Variables

The empirical analysis utilises macro data from a panel of 36 African countries from 2010 to 2020.

Table A.1 provides a list of the countries. We selected the countries and study period based on data availability. Specifically, data for the inequality-adjusted human development index is conspicuously scanty or missing for several countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cape Verde, Comoros, Chad, Eritrea, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Libya, South Sudan, Somalia, Djibouti, Madagascar, Mauritania, and Zimbabwe, both prior to and after the designated study period.

Our outcome variable is the inequality-adjusted human development index (IHDI). According to the UNDP (2022), the IHDI is a key indicator of wellbeing and development because it captures equity in achievements across three dimensions of human development: (i) a decent standard of living, (ii) long and healthy life, and (iii) knowledge. The inclusive bit of this measure is derived by accounting for within-country inequalities across its three components. In other words, the IHDI differs from the widely used human development index in the literature by adjusting gains in labour market participation, human capital development, and life expectancy to reflect inequalities within the population. Recent works employing the IHDI for empirical research include Nchofoung et al. (2021) and Andrès et al. (2017). It is imperative to note that the IHDI ranges between 0 (Lowest) and 1 (Highest), with higher levels indicating greater equality in human capital development, life expectancy and income. We retrieve the IHDI series from UNDP (2022).

The primary predictor variable in this study is distributional energy justice. Following Ofori et al. (2024), this study captures the variable as the ratio of the rural population with access to electricity to the urban population with access to electricity. We source access to electricity data from the World Development Indicators [WDI] (World Bank, 2023). Also, the moderating variable in this study is climate readiness. According to Chen et al. (2015), climate readiness denotes the institutional and infrastructural framework for mitigating and adapting to climate change. The study further disaggregates climate readiness into economic, social, and governance readiness to offer targeted policy recommendations. We collect the climate readiness data from ND-GAIN (2023).

The study controls for financial development, foreign direct investment, climate change vulnerability, and foreign aid in the estimation. The finance and economic development literature acknowledges the role of financial development in driving IHDI. For instance, it provides opportunities for individuals to acquire resources to invest in education, healthcare, and businesses (Conning & Morduch, 2011, p. 410). Evidence also shows that financial development promotes inclusive growth by reducing income inequality and poverty (Imai et al., 2012; Beck et al., 2007). The financial development variable is an index measuring the depth, efficiency, and accessibility of a country’s financial system. This index, therefore, encapsulates various dimensions, reflecting the sophistication and functionality of a country’s financial institutions in facilitating capital allocation and promoting economic development. This study obtains the corresponding data from the IMF’s Findex database (Svirydzenka, 2016).

The choice of foreign aid aligns with anecdotal evidence that development assistance enables recipient countries to expand access to social overhead capital (Jones & Tarp, 2015). For instance, foreign aid can promote IHDI by creating enabling conditions for social mobility and poverty alleviation. We source the foreign aid series from the World Bank (2023). We also consider foreign direct investment in line with neoliberal growth theory, which posits that foreign investors introduce human capital and technological shocks that developing countries can leverage to enhance competition, growth, and poverty reduction. Additionally, foreign direct investment can accelerate the diffusion of green technologies, improving the environmental quality of life (Herzer & Klasen, 2008). However, some studies also show that foreign direct investment may hinder inclusive human development by exacerbating unemployment, income inequality, and environmental degradation (Bokpin, 2017). We obtain the data from the World Bank (2023).

Finally, we consider climate vulnerability in line with the argument by Chen et al. (2015) that such vulnerabilities undermine the contributions of food, ecosystem services, health, human habitat, water, and infrastructure systems to human development. Climate vulnerability is an index measuring a country’s exposure, sensitivity, and ability to adapt to the negative impact of climate change. The index ranges from 0 (no vulnerability) to 1 (absolute vulnerability). We extract the data from the ND-GAIN (2023) database.

Table 1 summarises the description and data sources of all the variables.

3.2. Model Specification

This study examines the impact of energy justice on inclusive human development, with a specific focus on the moderating role of climate readiness. The theoretical foundation for analysing this non-linear relationship is grounded in the concepts of energy justice and resilience theory, as detailed in

Section 2. Building on this framework, we model IHDI using the reduced-form econometric specification of Andrès et al. (2017), and Asongu and Nwachukwu (2017):

where

is inclusive human development in country

at time

. Also,

is financial development,

means foreign direct investment,

denotes climate change vulnerability,

stands for foreign aid, and

is distributional energy justice.

As elaborated in

Section 2.2, we argue that the effect of energy justice on inclusive human development can be moderated by the degree of climate readiness in the sampled countries. In light of this, we modify Equation (1) by introducing an interaction term for energy justice and climate readiness, as expressed in Equation (2):

where,

denotes climate readiness (overall), which is further disaggregated into (i) economic readiness (

), (ii) social readiness (

), and (iii) governance readiness (

). Also,

is the interaction term for energy justice and climate readiness.

Consistent with Objectives 1 and 2, we pay particular attention to parameters

(i.e., the unconditional effect of energy justice on IHDI),

(i.e., the direct effect of climate change readiness on IHDI), and

(i.e., the coefficient of the energy justice and climate change readiness interaction term). Following Brambor et al. (2006), we compute the corresponding total/marginal effect from this interaction term as:

where

is the median value of climate readiness, while all other symbols remain, as earlier mentioned. Calculating total effects at the median values is crucial for mitigating the influence of outliers in the data. This means that we compute the marginal effect of energy justice by combining its direct effect, the coefficient of the interaction term between energy justice and climate readiness, and the median value of climate readiness. Consistent with the energy justice concept, we expect equality in electricity access to enhance IHDI (

). Similarly, we expect higher levels of climate readiness to enhance IHDI (

). Correspondingly, a synergistic effect between climate readiness and energy justice on IHDI is anticipated (

> 0).

The energy justice-climate readiness interaction term serves two important purposes. First, it allows the slope coefficient of energy justice to vary with climate readiness, providing a nuanced understanding of how these variables jointly influence inclusive human development. Second, it enables us to pinpoint where investments in climate readiness are most impactful for policy strategisation. If the interaction term is positive (negative) and statistically significant, it implies that enhancing climate readiness amplifies (offsets) the favourable (adverse) impacts of energy justice on inclusive human development.

3.3. Data and Preliminary Issues

In panel data regression analysis, issues such as multicollinearity, cross-sectional dependence, autocorrelation, and endogeneity pose significant risks to the unbiasedness, consistency, and reliability of parameter estimates. These issues can render inference and policy recommendations flawed. To circumvent these risks, this study conducts rigorous preliminary tests, specifically examining (i) unit roots, (ii) strong correlations, (iii) autocorrelation, and (iv) cross-sectional dependence. For the latter, this study employs the Pesaran (2004) cross-sectional dependence test for the assessment. The test is based on the null hypothesis of no cross-sectional dependence. Failure to reject the null hypothesis at the 1%, 5%, or 10% significance levels indicates the absence of cross-sectional dependence in the dataset. Depending on whether cross-sectional dependence is present, we employ either first-generation or second-generation unit root tests to examine the stationarity properties of the variables. Conducting these stationarity tests is essential to avoid misleading or spurious regression results (Pesaran, 2007).

To assess bivariate relationships among variables, we conduct pairwise correlation tests. Additionally, we apply Wooldridge’s (2002) autocorrelation test, which examines the null hypothesis of no first-order autocorrelation in the data. The results from these preliminary tests are as follows: First, the correlation test results in

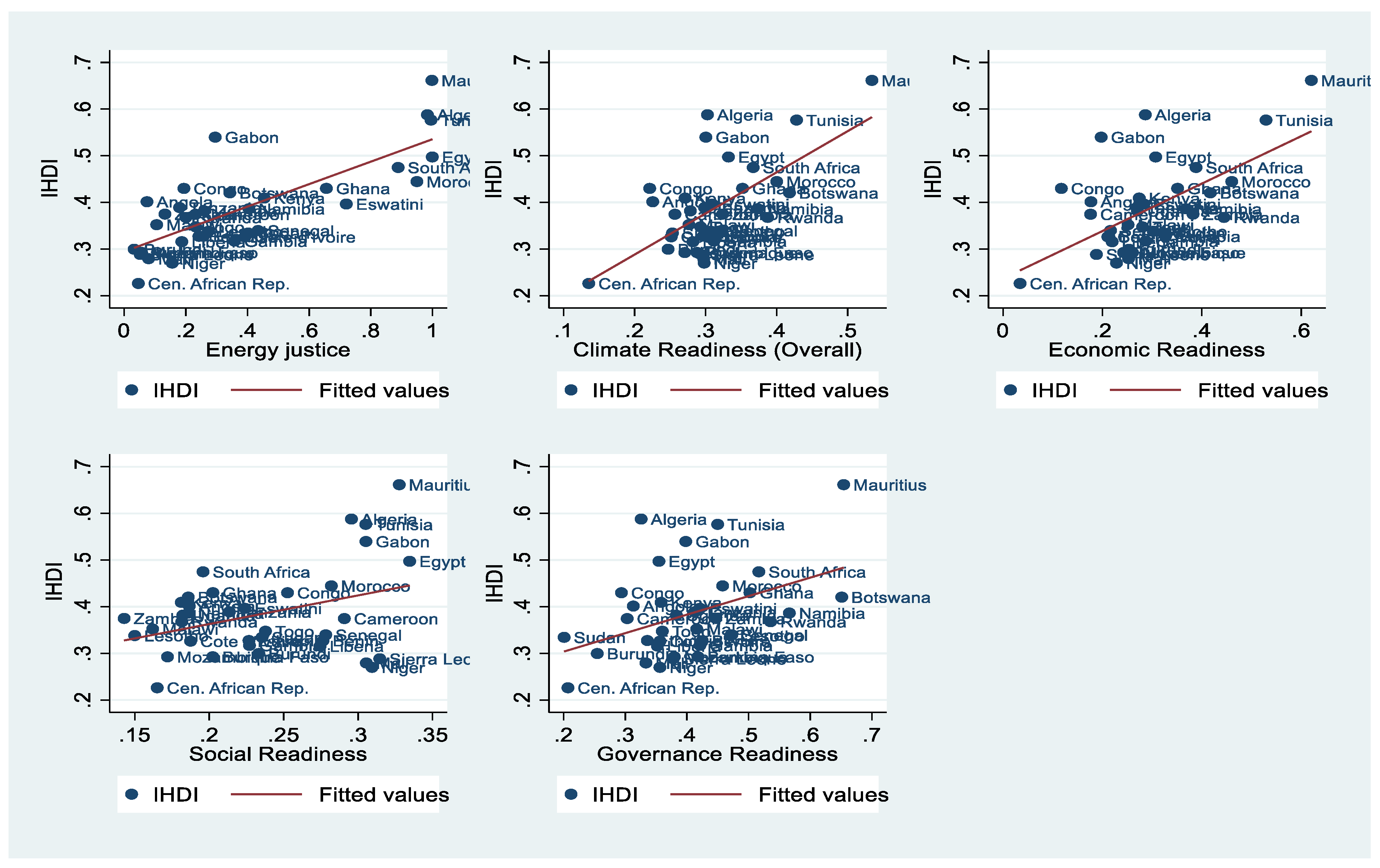

Table A.2 show that energy justice is positively correlated with IHDI. Also, consistent with intuition, the climate readiness variables positively correlate with IHDI. For the control variables, we observe that foreign aid, foreign direct investment, and climate change vulnerability are inversely correlated with IHDI. The graphical relationships presented in

Figure 1 reinforce these findings.

Table A.3 also presents the results of the serial correlation test. The evidence suggests the presence of serial correlation in the dataset (F-statistic = 127.806; p < 0.001). Further, the results in

Table A.4 reveal the presence of strong cross-sectional dependence in the data. We observe that variables such as IHDI and climate readiness are highly correlated across panels, which we account for in the estimation.

Source: Author’s calculations, with data sourced from the UNDP (2022b) and the World Bank (2024)Having established the presence of cross-sectional dependence, we assess the stationarity properties of the variables using the second-generation unit root tests. Precisely, we apply the cross-sectionally augmented panel unit root test (CIPS) and the Pesaran (2007) cross-sectionally augmented Dickey-Fuller (PESCADF) test. According to the CIPS and PESCADF estimates in

Table A.5, variables such as financial development, foreign aid, and climate change readiness exhibit no unit root either at the level or in first differences. For energy justice, IHDI, economic readiness, foreign direct investment, and governance readiness, stationarity is established only after the first difference is taken.

Although this preliminary data analysis is essential for understanding the developments in the underlying dataset, it provides no parameter estimates for inference. Accordingly, we subject the dataset to rigorous empirical analysis, taking into account the established issues of autocorrelation and cross-sectional dependence.

3.4. Identification and Estimation Strategy

This study employed the Schaffer (2010) fixed effect instrumental variable (FE-IV) regression with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors for the estimation. The rationale for employing this estimator is based on the established data and estimation challenges. First, the Schaffer (2010) FE-IV estimator is robust to general forms of cross-sectional and temporal dependence. In this study, cross-sectional dependence is evident, as confirmed by Pesaran’s (2004) cross-sectional independence test. We address this econometric challenge by invoking Driscoll and Kraay’s (1998) standard errors in the estimation procedure. Second, compared to competing estimation techniques such as Beck and Katz’s (1995) panel-corrected standard errors, the Schaffer (2010) FE-IV estimator is more efficient when the cross-sections exceed the study period. This study fulfils this requirement because the number of sampled countries (36) exceeds the length of the study period (11). Third, the Schaffer FE-IV estimator accounts for constant differences across countries and, thus, reduces the likelihood of heterogeneity bias by incorporating country-specific fixed effects in the estimation. Fourth, the Schaffer FE-IV estimator is flexible in handling endogeneity problems. The estimator accommodates both internal and external instruments to address endogeneity concerns.

In this study, endogeneity arises from two sources: reverse causality and measurement error. For the latter, climate readiness and energy justice can be challenging to measure accurately, as they often rely on composite indicators or self-reported data, which can introduce measurement error. This measurement error could correlate with the error term in Equations 1 and 2, leading to endogeneity. Concerning reverse causality, we argue that IHDI can influence both climate readiness and energy justice. This occurs because, as IHDI improves, countries tend to innovate or allocate greater resources toward strengthening climate change resilience and advancing energy justice. As argued succinctly in this study, progress in these two dimensions can also enhance IHDI. Endogeneity can also arise from a reverse causality between IHDI and financial access, as documented in the finance- and growth-led hypotheses (McKinnon, 1973).

Baum et al. (2003) submit that these endogeneity concerns can be accounted for in the estimation procedure by using in(ex)ternal instruments. However, due to data availability and measurement issues, we employ the first lags of the explanatory variables as instruments, and critically evaluate their appropriateness. In Africa, accurate data on potential external instruments such as historical climate policies, environmental trade, climate aid, energy infrastructure, and public awareness are limited due to resource constraints, inconsistent documentation, and political sensitivities. Furthermore, using dummy variables to address endogeneity in this context can be misleading, as they oversimplify complex and dynamic influences, thereby masking essential nuances. This simplification risks omitted variable bias, ultimately weakening the robustness of inferences.

Against this background, internal instruments can help predict current values of financial development, energy justice and climate readiness, while being uncorrelated with the error term. This approach is consistent with Schaffer (2010) and Wang and Bellemare (2020), who contend that lags of the regressors can be employed as instruments (i) in cases where identifying strictly exogenous instruments is cumbersome and (ii) provided they do not violate the independence assumption and exclusion restrictions. This is corroborated by Lewbel’s (2012) argument that introducing poor external instruments can aggravate the endogeneity problem, leading to biased and misleading inferences.

Additionally, we assess the robustness of the Schaffer FE-IV estimates by employing the two-step generalised method of moments (IV-GMM) estimator proposed by Baum et al. (2003). Similar to the Schaffer FE-IV estimator, Baum et al. (2003)’s IV-GMM estimator is robust to serial correlation and heteroskedasticity as it accommodates panel clustering and robust standard errors. More importantly, both the Baum and Schaffer techniques address endogeneity problems arising from reverse causality, omitted variable bias and measurement error using moment conditions. Their instrumentation procedure is ascertained by applying the weak identification tests of Cragg-Donald (1993) and Kleibergen-Paap (2006). We assess the latter by comparing the Kleibergen-Paap rank Wald statistic to the rule-of-thumb threshold of 10 suggested by Staiger and Stock (1997). The former is evaluated by comparing the relevant Fisher statistics to the Stock-Yogo (2005) critical values. For this study, the Stock-Yogo critical values used to assess the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistics are 11.04 (5%), 7.56 (10%), and 5.5 (20%). Instruments are considered relevant if the Wald or Fisher statistics exceed their corresponding critical values. Finally, we assess whether the instruments satisfy the exclusion restriction using the Hansen (1982) overidentification test. The Hansen test evaluates the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid against the alternative that they are invalid. Accordingly, the instruments are considered valid if the associated p-values are greater than 5%.

Finally, the Baum et al. (2003) IV-GMM estimator addresses concerns about multicollinearity and overparameterisation by accommodating interactive models, which means that all constitutive terms are included in the model, as specified in Equation 2 (see Brambor et al., 2006,

Section 3). This is crucial because, in contrast to linear additive models, the estimated coefficients for the interactive variables are interpreted as total effects of the modified variable (i.e., energy justice) rather than elasticities.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Summary Statistics

Table 2 provides the summary statistics for the variables. The data show an average energy justice score of 0.37 (37%). This indicates a high disparity in energy access across the rural-urban divide in Africa. Additionally, the data reveal an average climate readiness score of 0.309, which, according to Chen et al. (2015), signifies a low institutional and infrastructural capacity for mitigating and adapting to climate change.

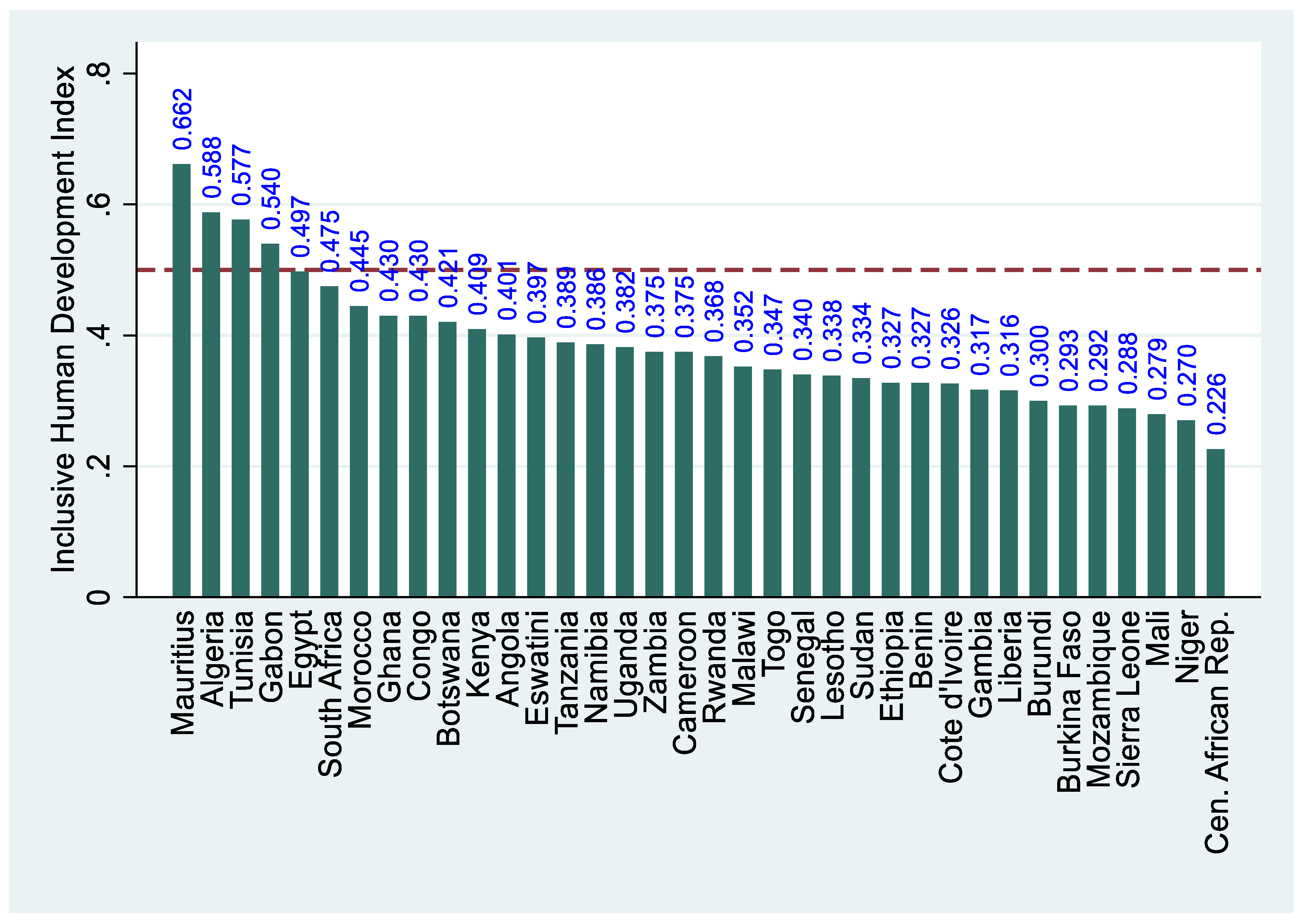

For the outcome variable, IHDI, the data reveal a mean value of 0.384. However, graphical analysis uncovers notable variation in inclusive human development across the sampled countries.

Figure 2 shows that among the 36 countries, only Mauritius, Algeria, Tunisia, Gabon, and Egypt achieve an IHDI score of 0.5 or higher. This highlights the generally low levels of inclusive human development in Africa, with countries such as the Central African Republic, Niger, Sierra Leone, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Burundi ranking among the lowest.

4.2. Effects of Energy Justice and Climate Change Readiness on IHDI

Table 3 presents the findings for the direct and conditional effects of energy justice on IHDI in the entire sample. For the first objective, the study finds that energy justice promotes IHDI. This result is statistically significant at the 1% significance level. The magnitude of the coefficient indicates that a 1% increase in energy justice results in a 0.087-point increase in IHDI (Column 1). Evidence in Column 2 also reveals that climate readiness enhances IHDI. We show that a 1% improvement in climate readiness raises IHDI by a remarkable 0.281 points. Across the economic, social and governance domains of readiness, the results suggest that only social and economic readiness are statistically significant in promoting IHDI. Specifically, for every 1% increase in economic and social readiness, the IHDI score rises by 0.091 and 0.830 points, respectively.

We now focus on the second objective, examining how climate readiness moderates the relationship between energy justice and IHDI. The results, presented in Columns 6–9, indicate that overall climate readiness interacts synergistically with energy justice to increase IHDI by 0.055 points (Column 6). This total effect is obtained by engaging the unconditional effect of energy justice on IHDI (-0.610), the coefficient of the energy justice and climate readiness interaction term (0.3870), and the median climate readiness score of 0.299 (see

Table 2). Following similar computations, we report total effects of 0.060, 0.046, and 0.205 points for the economic readiness-, social readiness-, and governance readiness-energy justice interaction terms, respectively.

Although all the total effects are positive and statistically significant, they reveal some interesting perspectives about the moderating role of climate change readiness in Africa. Notably, the analysis demonstrates that whereas governance and economic readiness interact with energy justice to promote IHDI, social readiness dampens the effect. The results further reveal that, relative to social and economic readiness, governance readiness is crucial for conditioning energy justice to promote IHDI. These heterogeneities become glaring when one juxtaposes the conditional effects of energy justice with their corresponding unconditional effects (Columns 6-9). Conspicuously, the direct effects of energy justice in Column 6 (-0.610), Column 7 (0.022) and Column 9 (-0.077) are lower than their attendant total effects of 0.054, 0.060, and 0.205 points. However, in Column 8, it is evident that in the presence of social readiness, the effect of energy justice on IHDI reduces from 0.120 points to 0.046 points.

The model diagnostics, which we report as part of the general regression statistics, confirm that the results are unbiased, consistent, and reliable for inference and policy recommendations. First, the study satisfies the overidentification restriction (instrument validity), as evidenced by the statistically insignificant Hansen J probability values at the 5% level. Finally, the Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic and Kleibergen-Paap rank Wald F-statistic are markedly higher than the corresponding Stock-Yogo (2005) and Staiger and Stock (1997) critical values, suggesting that the instruments are not weakly identified.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis: Effects of Energy Justice Across Income Groups

Thus far, the analysis shows that energy justice promotes IHDI in Africa, conditionally or unconditionally. While these findings provide fresh insights into the roles of energy equity and climate readiness in inclusive human development, a key question remains: do these effects differ between low- and high-income African countries? Accordingly, the study classifies the sampled countries into two groups—low-income and high-income—using the UNDP (2022) income classification. This yields two distinct sub-samples: 17 high-income countries and 19 low-income countries.

The findings in

Table 4 and

Table 5 reveal that while energy justice enhances IHDI in both income groups, the effect is more pronounced in high-income countries (0.112) compared to low-income countries (0.081). Conditioning the effect on climate readiness reveals a statistically significant synergistic impact in both groups. Two important patterns emerge across the dimensions of climate readiness. First, in high-income African countries, economic, governance, and social readiness each reinforce the impact of energy justice on IHDI. However, in low-income countries, such complementarities emerge only through economic and governance readiness. Second, where synergy exists, the total effect of energy justice is consistently more pronounced in high-income than in low-income countries. For example, the total effect from the energy justice–economic readiness interaction is 0.099 points in high-income countries, compared to 0.039 points in low-income countries (see Column 7 of

Table 4 and

Table 5). These results underscore the importance of institutional and infrastructural quality in conditioning the extent to which energy justice translates into inclusive human development across different income contexts in Africa.

4.4. Robustness Check

This section deepens the robustness of the findings by employing a different estimator. Precisely, we assess whether the results in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 remain the same when the Baum et al. (2003) IV-GMM estimator is employed. Despite marginal differences in parameter estimates, the results in

Table 6,

Table A.6 and

Table A.7 demonstrate robustness of our earlier findings. For instance, the results in Column 1 of

Table 6 confirm the IHDI-enhancing effect of energy justice. The evidence shows that every 1% increase in energy justice raises the IHDI score by 0.136 points, confirming the positive impact reported in

Table 3.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that climate readiness increases HDI by 0.354 points. Consistent with the evidence in

Table 3, the findings reveal that all climate change dynamics are statistically significant in prompting IHDI, except for governance readiness. The evidence further demonstrates that every 1% improvement in economic and social readiness accelerates Africa’s progress in IHDI by 0.214 points and 0.272 points, respectively. Concerning Objective 2, the estimates in Columns 6-9 confirm the synergistic effect of energy justice and climate readiness on IHDI. Consistent with the evidence in

Table 3, we find that governance readiness is the most crucial channel for conditioning energy justice to promote IHDI (0.117 points). The findings in

Table A.6 and

Table A.7 also show that while energy justice and climate readiness jointly enhance HDI in middle- and high-income African countries, this synergy is absent in low-income countries, plausibly due to their glaring weaknesses in climate readiness.

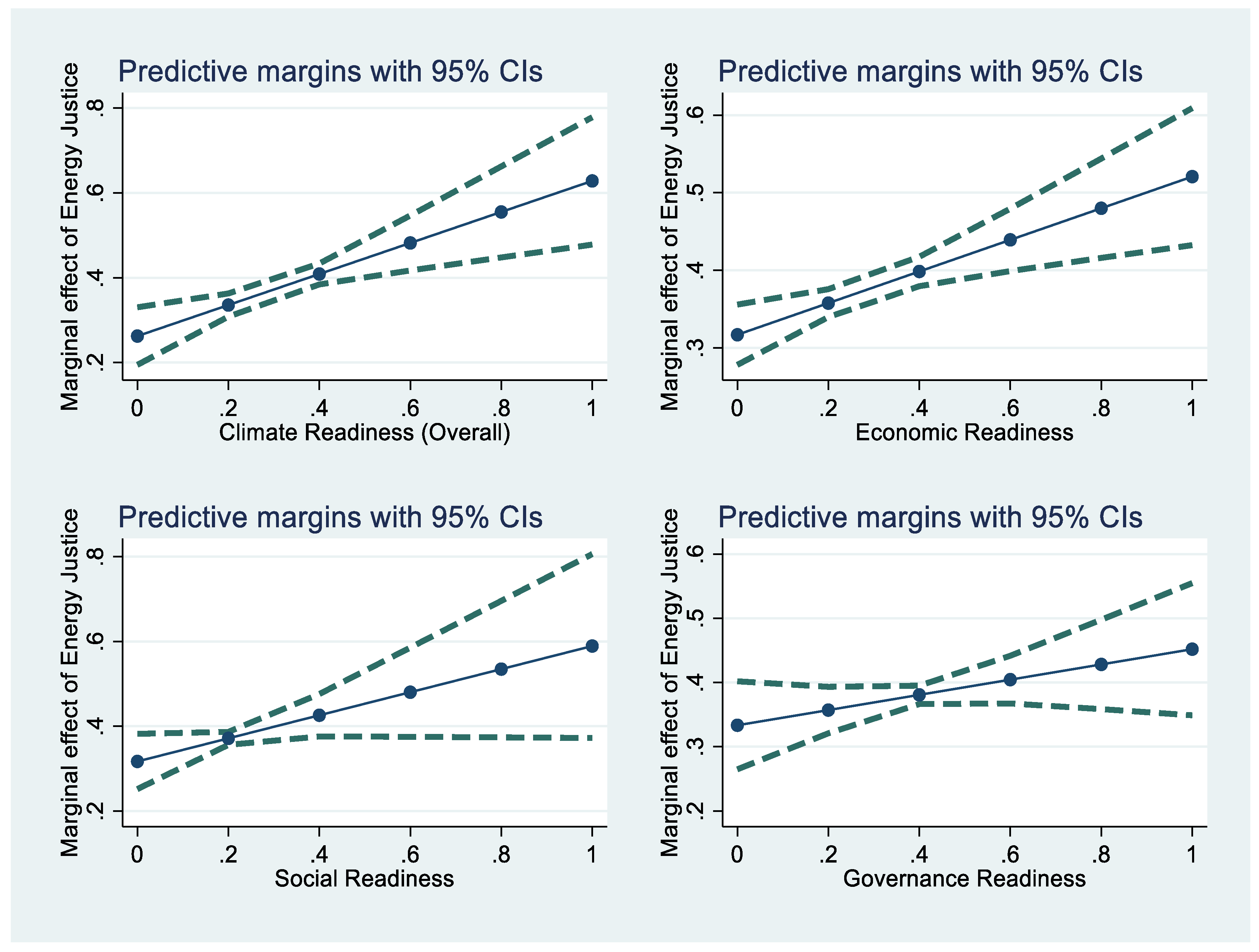

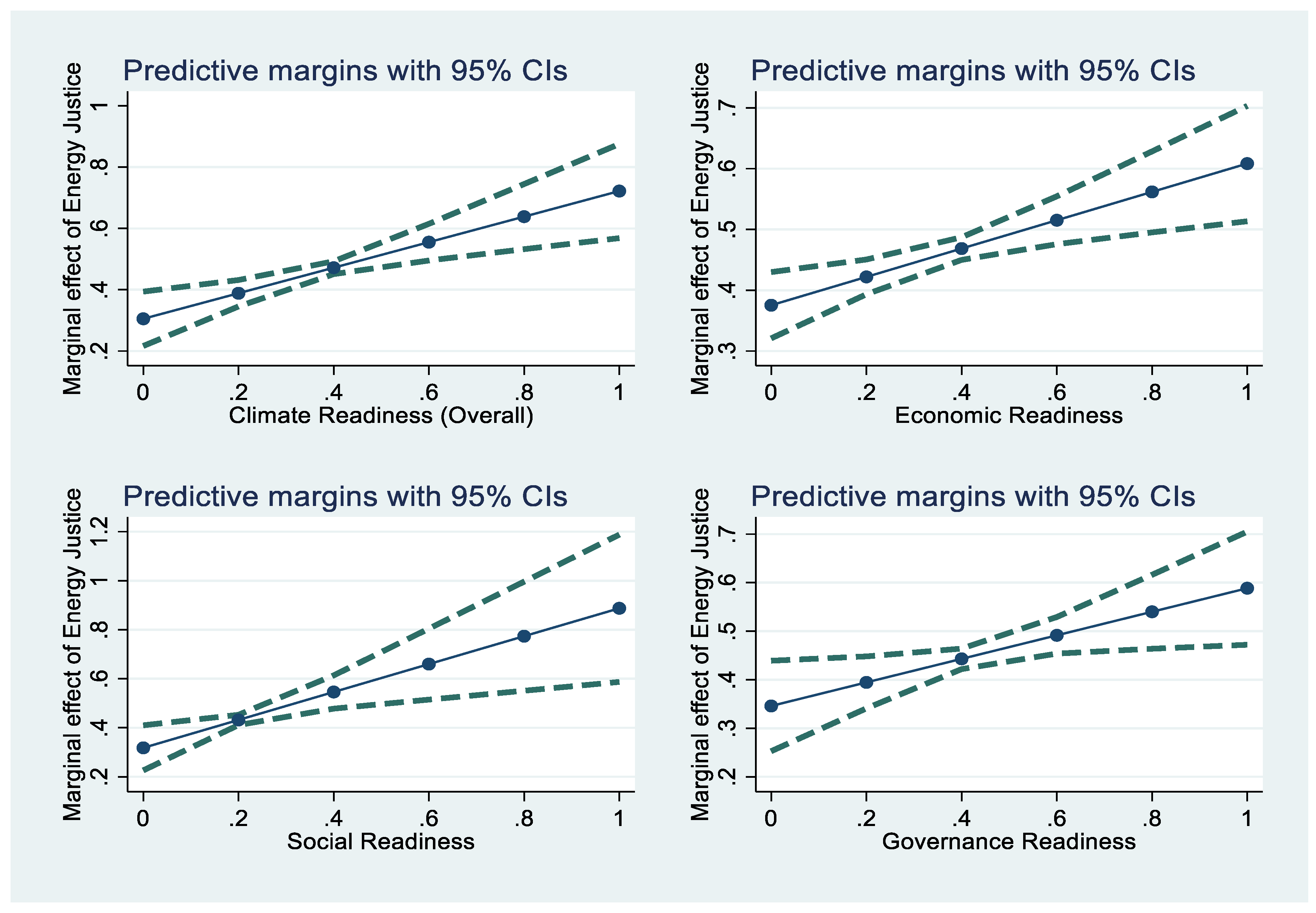

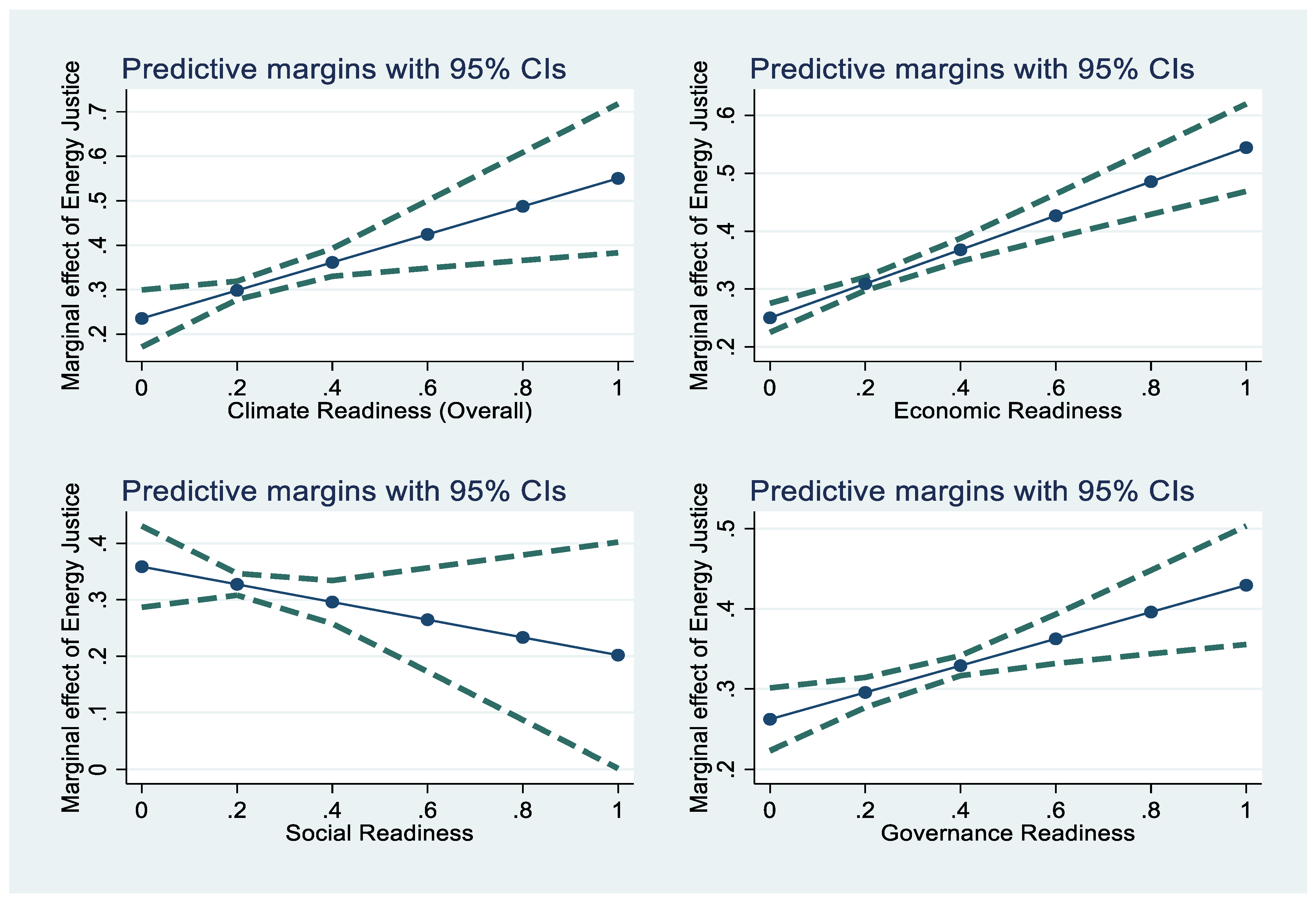

We extend the robustness checks by investigating whether the marginal effect of energy justice, evaluated at the median of climate readiness, on IHDI is not spurious or arbitrary. This assessment is policy-relevant as it demonstrates whether the positive impact of energy justice on IHDI strengthens with successive gains in climate readiness, underscoring the importance of advancing both in tandem to foster inclusive development. For the overall sample, evidence from

Figure A.1 shows that the positive impact of energy justice on the IHDI increases significantly with improvements across all dimensions of climate readiness. Similar patterns emerge for high-income African countries, indicating that gains from energy justice are amplified by advances in economic, social, and governance readiness (see

Figure 3). However, consistent with the contingency analysis,

Figure 4 reveals that in low-income African countries, all dimensions of climate readiness, except social readiness, enhance the IHDI-boosting effect of energy justice.

4.5. Contribution to the Economic Development Literature

This study advances the emerging body of research on the socioeconomic impacts of energy justice and climate readiness on three fronts. First, we demonstrate that energy justice promotes IHDI. One channel through which this can be feasible is human capital development, considering the indispensable role of energy justice in enabling remote learning, expanding access to digital resources, and enhancing effective student-teacher interaction. Energy justice can also enable people, regardless of location, to leverage ICT tools (e.g., tablets, computers, and Generative AI) to develop critical skills, sharpen competencies, stay competitive in the ever-evolving job market, and/or mitigate socioeconomic challenges. Moreover, energy justice can facilitate quality healthcare delivery and long life by powering essential medical equipment, storing medicines and blood, and the effective deployment of technologies such as 3D printing for surgeries. Additionally, in labour markets, energy justice can reduce the cost and risk associated with establishing family businesses and small-scale enterprises. This can stimulate decent job creation and enhance the overall standard of living. Our contribution builds on recent studies investigating the impact of energy justice on social progress in developing countries (see e.g., Adams et al., 2024; Banerjee et al., 2021; Adom et al., 2021; Youssef et al., 2015)

The second significant lesson from this study is that governance and economic readiness amplify the positive impact of energy justice on IHDI, while social readiness dampens it. Economic readiness can be instrumental, for instance, in refining regulatory frameworks, securing property rights, and fostering investment autonomy. In predominantly informal economies, such as those in Africa, economic readiness can significantly reduce business operation costs and empower firms and households to better mitigate energy burdens. This can drive open innovation and accelerate the adoption of frontier technologies (e.g., drones, robotics, and 5G) by firms and households, which, according to Ofori et al. (2025), increases average income. Given Africa’s youthful and growing digitally skilled population, these advancements can lift millions out of poverty by enhancing socioeconomic mobility, entrepreneurship, and private sector performance. Governance readiness in the form of territorial stability, sound economic policies, and efficient resource allocation can also condition energy justice to yield substantial IHDI impacts. For instance, governance readiness can ensure that energy resources are allocated based on need and impact rather than political or economic bias (Best & Burke, 2017; Ahlborg et al., 2015). In this context, energy equity can play a pivotal role in narrowing rural–urban disparities in education, healthcare, and employment outcomes. Moreover, governance readiness enhances the protection of energy infrastructure and reduces inefficiencies in energy systems, thereby ensuring more reliable, affordable, and inclusive energy distribution. This, in turn, enables businesses, educational institutions, and healthcare facilities to improve operational efficiency, fostering more equitable outcomes in human development.

Conversely, the dampening effect of social readiness, especially in low-income countries, reflects persistent structural inequalities in access to social infrastructure and barriers to integrating innovations (Chen et al., 2015). In such contexts, improvements in energy justice may disproportionately benefit affluent households and established enterprises, marginalising lower-income groups and small businesses. This can undermine the effectiveness of energy justice in fostering equitable outcomes in income, quality healthcare, employment, and human capital.

The third major finding from this study is that conditionally or unconditionally, the impact of energy justice on IHDI is striking in high-income African countries relative to their low-income counterparts. This evidence highlights how heterogeneities in institutional fabric and infrastructure quality across low- and high-income African countries influence the translation of energy equity into more equitable outcomes in terms of income, education, and health. By highlighting these structural heterogeneities, this research enriches the evolving scholarly discourse on the role of infrastructure and institutional quality in the link between energy justice and outcomes such as (un)employment, income inequality, human capital development and life expectancy (see e.g., Adams et al., 2024; Ajide et al., 2023; Sarkodie & Adams, 2020).

5. Summary, Concluding Remarks and Policy Implications

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on the role of energy justice in inclusive human development. Specifically, it examines how distributional energy justice, operationalised as rural–urban equality in electricity access, and climate change readiness (disaggregated into governance, economic, and social readiness) influence inclusive human development in Africa. Our focus on distributional energy justice is motivated by the widespread energy poverty of over 600 million people across the African continent. Furthermore, recent data from ND-GAIN (2023) suggests that climate change undermines economic development. Within the context of energy justice and resilience theory, it is expected that progress in energy justice and institutional capacity to mitigate climate threats and impacts can foster inclusive human development. However, empirical evidence pinpointing the extent to which energy justice affects IHDI, including how economic, governance, and social readiness moderate the relationship, remains grey in the extant scholarship. We address these gaps through contingency and sensitivity analyses, assessing whether the impacts differ across 36 low- and high-income African countries over the period from 2010 to 2020.

To ensure robustness against common panel data issues, including endogeneity, heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence, we employ instrumental variable regression techniques for the analysis. The results demonstrate that energy justice promotes IHDI in Africa, with a remarkable impact in high-income countries. Findings from the contingency analysis also reveal that economic and governance readiness amplify the positive effect of energy justice on IHDI in both low- and high-income African countries. However, this synergy eludes low-income countries when social readiness is considered. Sensitivity analysis also indicates that, compared with their low-income counterparts, high-income African countries derive greater benefits from progress in both energy justice and climate readiness.

Three critical conclusions emerge from this study. First, expanding rural–urban equality in electricity access constitutes a vital pathway for advancing inclusive human development in Africa. Second, strengthening the economic and governance dimensions of climate change readiness serves as a critical complementary mechanism for amplifying the positive impact of energy justice on inclusive human development. Finally, in low-income countries, weaknesses in social readiness undermine the IHDI-enhancing benefits of energy equity.

These findings lead us to the following policy recommendations. First, African governments must intensify efforts to tackle the widespread energy poverty and the rural-urban access disparity by investing in renewable energy generation, modernising distribution systems, and eliminating inefficiencies and hazards in existing infrastructure. Policymakers should channel resources into these areas while fostering partnerships with the private sector in electricity distribution and complementary investments in quality education and healthcare. Second, given the complementary role of economic readiness in amplifying the impact of energy equity on inclusive human development, governments should streamline regulatory processes, remove punitive taxes, and support households in leveraging improved electricity access to enhance economic participation, education, and access to health services. Equally important is strengthening governance readiness to create an enabling investment climate through public financial integrity, transparent institutions, and political stability. Third, given the technical, financial, and institutional constraints many African countries face in expanding electricity access and addressing climate change, international development partners such as the World Bank, European Union, African Development Bank, and International Finance Corporation should provide coordinated financial and logistical assistance, particularly in building digital infrastructure, supporting political stability, and advancing climate-resilient innovation. Fourth, for low-income countries, policymakers should prioritise investment in smart education and healthcare infrastructure to broaden accessibility. In contrast, higher-income African countries should focus on consolidating economic freedom and scaling up investments in digital systems and climate-smart technologies to protect all against emerging socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

This study adopts a distributional perspective of energy justice, driven by data limitations for other dimensions, such as restorative, recognition, and procedural justice, within the African context over the study period. Additionally, our final analytical sample comprises 36 African countries, reduced from the original 54 due to missing IHDI data for the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cape Verde, Comoros, Chad, Eritrea, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Libya, South Sudan, Somalia, Djibouti, Madagascar, Mauritania, and Zimbabwe. However, by focusing on the most fundamental aspect of energy justice—equality in electricity access—and employing robust estimation techniques, including sensitivity checks, this research offers both substantial scholarly value and clear policy relevance.

To advance this field, we propose two key extensions. First, future studies should investigate how other domains of energy justice, such as affordability and community decision-making, shape human development outcomes, including assessing whether green finance mechanisms exert a moderating influence within these relationships. Second, while this study analyses the joint effect of energy justice and climate readiness on inclusive development, subsequent research could explore how energy justice influences the environmental quality of life (wellbeing). Such work would provide a valuable complement to the present study and generate more targeted policy insights in support of Africa’s Agenda 2063.

Declaration: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Table A1.

List of sampled countries.

Table A1.

List of sampled countries.

| Country |

IHDI Average |

EJ

Average |

CCR

Average |

Income

Group |

| Algeria |

0.588 |

0.984 |

0.303 |

High |

| Angola |

0.401 |

0.074 |

0.225 |

Middle |

| Benin |

0.327 |

0.243 |

0.305 |

Low |

| Botswana |

0.421 |

0.343 |

0.418 |

Middle |

| Burkina Faso |

0.293 |

0.057 |

0.288 |

Low |

| Burundi |

0.300 |

0.032 |

0.247 |

Low |

| Cameroon |

0.375 |

0.231 |

0.257 |

Middle |

| Central African Republic |

0.226 |

0.046 |

0.135 |

Low |

| Congo |

0.430 |

0.194 |

0.221 |

Middle |

| Cote d'Ivoire |

0.326 |

0.392 |

0.252 |

Middle |

| Egypt |

0.497 |

0.999 |

0.332 |

High |

| Eswatini |

0.397 |

0.721 |

0.309 |

Middle |

| Ethiopia |

0.327 |

0.257 |

0.297 |

Low |

| Gabon |

0.540 |

0.295 |

0.300 |

High |

| Gambia |

0.317 |

0.358 |

0.312 |

Low |

| Ghana |

0.430 |

0.656 |

0.352 |

Middle |

| Kenya |

0.409 |

0.454 |

0.271 |

Middle |

| Lesotho |

0.338 |

0.274 |

0.308 |

Low |

| Liberia |

0.316 |

0.187 |

0.282 |

Low |

| Malawi |

0.352 |

0.105 |

0.276 |

Low |

| Mali |

0.279 |

0.079 |

0.297 |

Low |

| Mauritius |

0.662 |

0.998 |

0.534 |

Very High |

| Morocco |

0.445 |

0.950 |

0.400 |

Middle |

| Mozambique |

0.292 |

0.056 |

0.271 |

Low |

| Namibia |

0.386 |

0.405 |

0.373 |

Middle |

| Niger |

0.270 |

0.156 |

0.298 |

Low |

| Rwanda |

0.368 |

0.200 |

0.387 |

Low |

| Senegal |

0.340 |

0.434 |

0.322 |

Low |

| Sierra Leone |

0.288 |

0.052 |

0.293 |

Low |

| South Africa |

0.475 |

0.889 |

0.367 |

High |

| Sudan |

0.334 |

0.402 |

0.253 |

Low |

| Tanzania |

0.389 |

0.180 |

0.298 |

Low |

| Togo |

0.347 |

0.233 |

0.293 |

Low |

| Tunisia |

0.577 |

0.995 |

0.428 |

High |

| Uganda |

0.382 |

0.260 |

0.279 |

Low |

| Zambia |

0.375 |

0.132 |

0.324 |

Middle |

Table A2.

Pairwise correlation matrix.

Table A2.

Pairwise correlation matrix.

| Variables |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

| (1) Inclusive human development |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (2) Gender inequality |

-0.761***

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (3) Energy justice |

0.778***

|

-0.666***

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (4) Climate change readiness |

0.630***

|

-0.717***

|

0.618***

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (5) Economic readiness |

0.584***

|

-0.766***

|

0.606***

|

0.912***

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (6) Social readiness |

0.376***

|

-0.117*

|

0.381***

|

0.294***

|

0.118*

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| (7) Governance readiness |

0.409***

|

-0.521***

|

0.354***

|

0.832***

|

0.650***

|

-0.0875 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| (8) Financial development |

0.505***

|

-0.597***

|

0.578***

|

0.640***

|

0.600***

|

0.0100 |

0.613***

|

1 |

|

|

|

| (9) Foreign direct investment |

-0.146**

|

0.176***

|

-0.171***

|

-0.0852 |

-0.140**

|

0.0416 |

-0.0363 |

-0.0874 |

1 |

|

|

| (10) Climate change vulnerability |

-0.805***

|

0.678***

|

-0.729***

|

-0.501***

|

-0.452***

|

-0.190***

|

-0.399***

|

-0.582***

|

0.147**

|

1 |

|

| (11) Foreign aid |

-0.560***

|

0.399***

|

-0.504***

|

-0.354***

|

-0.320***

|

-0.123*

|

-0.288***

|

-0.382***

|

0.444***

|

0.538***

|

1 |

Table A3.

Serial correlation test result.Test

Table A3.

Serial correlation test result.Test

| |

Test statistic |

p-value |

| Wooldridge’s (2002) test of autocorrelation in panel data |

127.806*** |

0.000 |

Table A4.

Cross-sectional dependence test results.

Table A4.

Cross-sectional dependence test results.

| Variable |

CD-test |

correlation |

Absolute correlation |

P-value |

| Inclusive human development |

68.81*** |

0.827 |

o.827 |

0.000 |

| Financial development |

12.67*** |

0.152 |

0.401 |

0.000 |

| Foreign aid |

10.42*** |

0.125 |

0.336 |

0.000 |

| Climate change vulnerability |

23.96*** |

0.288 |

0.484 |

0.000 |

| Foreign direct investment |

3.55*** |

0.043 |

0.324 |

0.000 |

| Energy justice |

31.14*** |

0.374 |

0.579 |

0.000 |

| Climate change readiness |

37.44*** |

0.450 |

0.550 |

0.000 |

| Economic readiness |

46.55*** |

0.559 |

0.639 |

0.000 |

| Social readiness |

76.44*** |

0.918 |

0.918 |

0.000 |

| Governance readiness |

2.70*** |

0.032 |

0.457 |

0.007 |

Table A5.

PESCADF and CIPS unit root test results.

Table A5.

PESCADF and CIPS unit root test results.

| Variable |

PESCADF

Level statistic |

PESCADF

First difference statistic |

CIPS

Level statistic |

CIPS

First difference statistic |

| IHDI |

-1.822 |

-2.930*** |

-1.818 |

-2.509 |

| Financial development |

-2.692** |

-3.075*** |

-2.727** |

-3.543*** |

| Foreign aid |

-1.908 |

-2.927*** |

-2.402*** |

-3.740*** |

| Climate change vulnerability |

-2.267 |

-2.920*** |

-2.724** |

-3.336*** |

| Foreign direct investment |

-1.737 |

-2.023 |

-2.419 |

-3.306*** |

| Energy justice |

1.175 |

-0.742 |

-2.023 |

-3.007*** |

| Climate change readiness |

-2.464 |

-3.150*** |

-2.101 |

-2.876** |

| Economic readiness |

-1.869 |

-3.614*** |

-1.696 |

-2.331 |

| Social readiness |

-1.659 |

-3.388*** |

-2.188 |

-2.951** |

| Governance readiness |

-1.906 |

-1.744 |

-2.072 |

-2.834*** |

Figure A1.

Marginal effects of energy justice on IHDI in African countries (Full sample).

Figure A1.

Marginal effects of energy justice on IHDI in African countries (Full sample).

Table A6.

Effects of energy justice on IHDI in Middle- and High-income Countries (Baum et al. 2003 IV-GMM Estimates).

Table A6.

Effects of energy justice on IHDI in Middle- and High-income Countries (Baum et al. 2003 IV-GMM Estimates).

| Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Energy justice (EJ) |

0.1014**

|

0.0857**

|

0.0811**

|

0.0578 |

0.0896**

|

-0.1736*

|

-0.0684 |

-0.1223 |

-0.1598 |

| |

(0.045) |

(0.037) |

(0.035) |

(0.045) |

(0.045) |

(0.099) |

(0.071) |

(0.088) |

(0.116) |

| Climate change readiness |

|

0.4671**

|

|

|

|

-0.0136 |

|

|

|

| |

|

(0.224) |

|

|

|

(0.154) |

|

|

|

| Economic readiness |

|

|

0.2623**

|

|

|

|

-0.0381 |

|

|

| |

|

|

(0.121) |

|

|

|

(0.085) |

|

|

| Social readiness |

|

|

|

0.6104***

|

|

|

|

0.1548 |

|

| |

|

|

|

(0.194) |

|

|

|

(0.305) |

|

| Government readiness |

|

|

|

|

0.0840 |

|

|

|

-0.1155 |

| |

|

|

|

|

(0.146) |

|

|

|

(0.112) |

| EJ x Climate change readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

0.7504***

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

(0.284) |

|

|

|

| EJ x Economics readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.4726**

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.196) |

|

|

| EJ x Social readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.7227 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.458) |

|

| EJ x Governance readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.6243**

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.273) |

| Total effect (median) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.0717** |

0.0847** |

0.0410 |

0.1036*** |

| |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.0353 |

(0.0340) |

(0.0341) |

(0.0381) |

| Constant |

0.7697***

|

0.5454**

|

0.6367***

|

0.4795**

|

0.7731***

|

0.6933***

|

0.6831***

|

0.5939***

|

0.8382***

|

| |

(0.184) |

(0.224) |

(0.216) |

(0.193) |

(0.200) |

(0.202) |

(0.205) |

(0.178) |

(0.196) |

| Observations |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

| Fisher statistics |

14.310*** |

10.391*** |

12.832*** |

6.4958*** |

13.272*** |

10.512*** |

8.1241*** |

8.1416*** |

7.3463*** |

| Hansen J p-value |

0.1115 |

0.1223 |

0.1557 |

0.5085 |

0.0880 |

0.1608 |

0.1950 |

0.5295 |

0.0687 |

| Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic |

8.3666** |

8.1418** |

8.3234** |

7.5989** |

8.1513** |

8.0673** |

8.0547** |

7.2760* |

8.0240** |

| Kleibergen-Paap rank Wald F Statistic |

104.36*** |

92.910*** |

99.539*** |

62.695*** |

92.640*** |

76.118*** |

86.604*** |

50.282*** |

62.666*** |

Table A7.

Effects of energy justice on Low-income Countries (Baum et al. 2003 IV-GMM Estimates).

Table A7.

Effects of energy justice on Low-income Countries (Baum et al. 2003 IV-GMM Estimates).

| Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Energy justice (EJ) |

0.1129***

|

0.0806**

|

0.0572*

|

0.1146***

|

0.1050***

|

0.4869***

|

0.2371***

|

0.2965*

|

0.4388***

|

| |

(0.031) |

(0.038) |

(0.032) |

(0.027) |

(0.036) |

(0.152) |

(0.077) |

(0.169) |

(0.103) |

| Climate change readiness |

|

0.3452***

|

|

|

|

0.5743***

|

|

|

|

| |

|

(0.101) |

|

|

|

(0.130) |

|

|

|

| Economic readiness |

|

|

0.3049***

|

|

|

|

0.4177***

|

|

|

| |

|

|

(0.054) |

|

|

|

(0.073) |

|

|

| Social readiness |

|

|

|

-0.1312 |

|

|

|

-0.0055 |

|

| |

|

|

|

(0.149) |

|

|

|

(0.176) |

|

| Government readiness |

|

|

|

|

0.1167*

|

|

|

|

0.3340***

|

| |

|

|

|

|

(0.063) |

|

|

|

(0.094) |

| EJ x Climate change readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

-1.3138**

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

(0.523) |

|

|

|

| EJ x Economics readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.6255**

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.245) |

|

|

| EJ x Social readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.7667 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.666) |

|

| EJ x Governance readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.8442***

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.278) |

| Total effect (median) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.1072*** |

0.0713** |

0.1225*** |

0.1154*** |

| |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

(0.0340) |

(0.0316) |

(0.0295) |

(0.0316) |

| Constant |

0.4636***

|

0.3736***

|

0.4763***

|

0.4556***

|

0.3441***

|

0.3456***

|

0.4466***

|

0.4276***

|

0.3141***

|

| |

(0.090) |

(0.088) |

(0.076) |

(0.087) |

(0.105) |

(0.075) |

(0.070) |

(0.089) |

(0.088) |

| Observations |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

| Fisher statistics |

5.0430*** |

7.8465*** |

12.4045*** |

5.2826*** |

3.948** |

23.383*** |

18.570*** |

15.202*** |

6.207*** |

| Hansen J p-value |

0.4800 |

0.1814 |

0.0824 |

0.5663 |

0.3573 |

0.1373 |

0.0999 |

0.5382 |

0.1447 |

| Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic |

203.68*** |

198.45*** |

174.69*** |

201.96*** |

202.38*** |

195.25*** |

174.10*** |

200.39*** |

193.81*** |

| Kleibergen-Paap rank Wald F Statistic |

458.12*** |

731.74*** |

1123.22*** |

390.79*** |

404.61*** |

530.18*** |

1716.85*** |

465.72*** |

429.29*** |

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. Handbook of Economics Growth, 1A, 385-472.

- Acheampong, A. O., Dzator, J., & Shahbaz, M. (2021). Empowering the powerless: Does access to energy improve income inequality? Energy Economics, 99, 105288. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L. A., Pineda, J., Galotto, L., Maharja, P., & Sheng, F. (2019a). Assessment of complementarities between GGGI’s Green Growth Index and UNEP’s Green Growth Progress Index. GGGI Technical Report No. 10, Green Growth Performance Measurement (GGPM) Program, Global Green Growth Institute, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

- Adams, S., Ofori, I. K., & Gbolonyo, E. Y. (2025). Energy consumption, democracy, and income inequality in Africa. Empirical Economics, 1-40. [CrossRef]

- Adams, S., & Klobodu, E. K. M. (2017). Capital flows and the distribution of income in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 55, 169-178. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Black, R., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., & Thomas, D. S. (2015). Focus on environmental risks and migration: causes and consequences. Environmental Research Letters, 10(6), 060201. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. Neil, Suraje Dessai, Marisa Goulden, Mike Hulme, Irene Lorenzoni, Donald R. Nelson, Lars Otto Naess, Johanna Wolf, and Anita Wreford. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change 93(3), 335-354. [CrossRef]

- Adom, P. K., & Amoani, S. (2021). The role of climate adaptation readiness in economic growth and climate change relationship: An analysis of the output/income and productivity/institution channels. Journal of Environmental Management, 293, 112923. [CrossRef]

- Adom, P. K., Amuakwa-Mensah, F., Agradi, M. P., & Nsabimana, A. (2021). Energy poverty, development outcomes, and transition to green energy. Renewable Energy, 178, 1337-1352. [CrossRef]

- Ahlborg, H., Boräng, F., Jagers, S. C., & Söderholm, P. (2015). Provision of electricity to African households: The importance of democracy and institutional quality. Energy policy, 87, 125- 135. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Mathai, M. V., & Parayil, G. (2014). Household electricity access, availability, and human wellbeing: Evidence from India. Energy Policy, 69, 308-315. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M., & Azam, M. (2016). Causal nexus between energy consumption and economic growth for high, middle, and low-income countries using frequency domain analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60, 653-678. [CrossRef]

- Ajide, K. B., Dauda, R. O., & Alimi, O. Y. (2023). Electricity access, institutional infrastructure and health outcomes in Africa. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(1), 198-227. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, A. R., Amavilah, V., & Asongu, S. (2017). Linkages between Formal Institutions, ICT Adoption, and inclusive human development in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 175-203). Springer International Publishing.

- Apergis, N., & Payne, J. E. (2009). Energy consumption and economic growth: Evidence from The Commonwealth of Independent States. Energy Economics, 31(5), 641-647. [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A., Nwachukwu, J.C. (2017). Increasing Foreign Aid for Inclusive Human Development in Africa. Social Indicator Research, 138, 443–466. [CrossRef]

- Armey, L. E., & Hosman, L. (2016). The centrality of electricity to ICT use in low-income countries. Telecommunications Policy, 40(7), 617-627. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1, pp. 141-154). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R.H. (1963). Social learning and personality development. Holt Rinehart and Winston: New York.

- Banerjee, R., Mishra, V., & Maruta, A. A. (2021). Energy poverty, health, and education outcomes: evidence from the developing world. Energy economics, 101, 105447. [CrossRef]