Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

31 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Briefing on national development models

2.2. Global Competitiveness

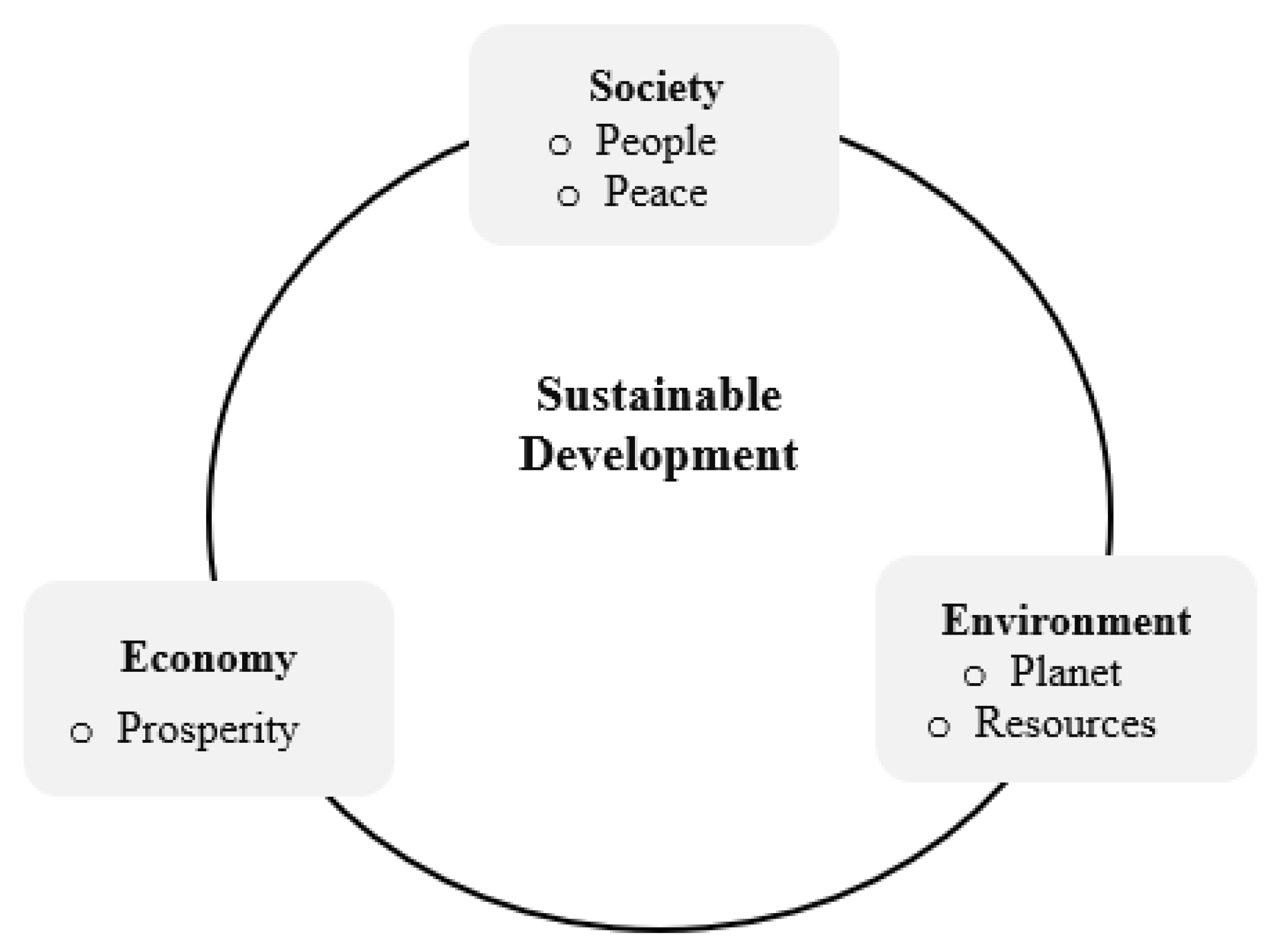

2.3. Sustainable Development

2.3.1. Economic dimension

- Prosperity

2.3.2. Social dimension

- People

- Peace

2.3.3. Environmental dimension

- Planet

- Resources

2.4. Happiness &Life Satisfaction

2.5. Foreign Direct Investment

2.5.1. FDII

2.5.2. FDIO

2.5.3. FDII-FDIO relationship

2.6. Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Measures selection and data sources

3.2. Country cluster determination

| Country Cluster | Countries |

|---|---|

| Advanced Economies |

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hon Kong SAR, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States. |

| Emerging & Developing Europe |

Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia. |

| Emerging & Developing Asia |

Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Vietnam. |

| Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan |

Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Islamic Rep., Jordan, Kuwait, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates. |

| Latin America & the Caribbean |

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela. |

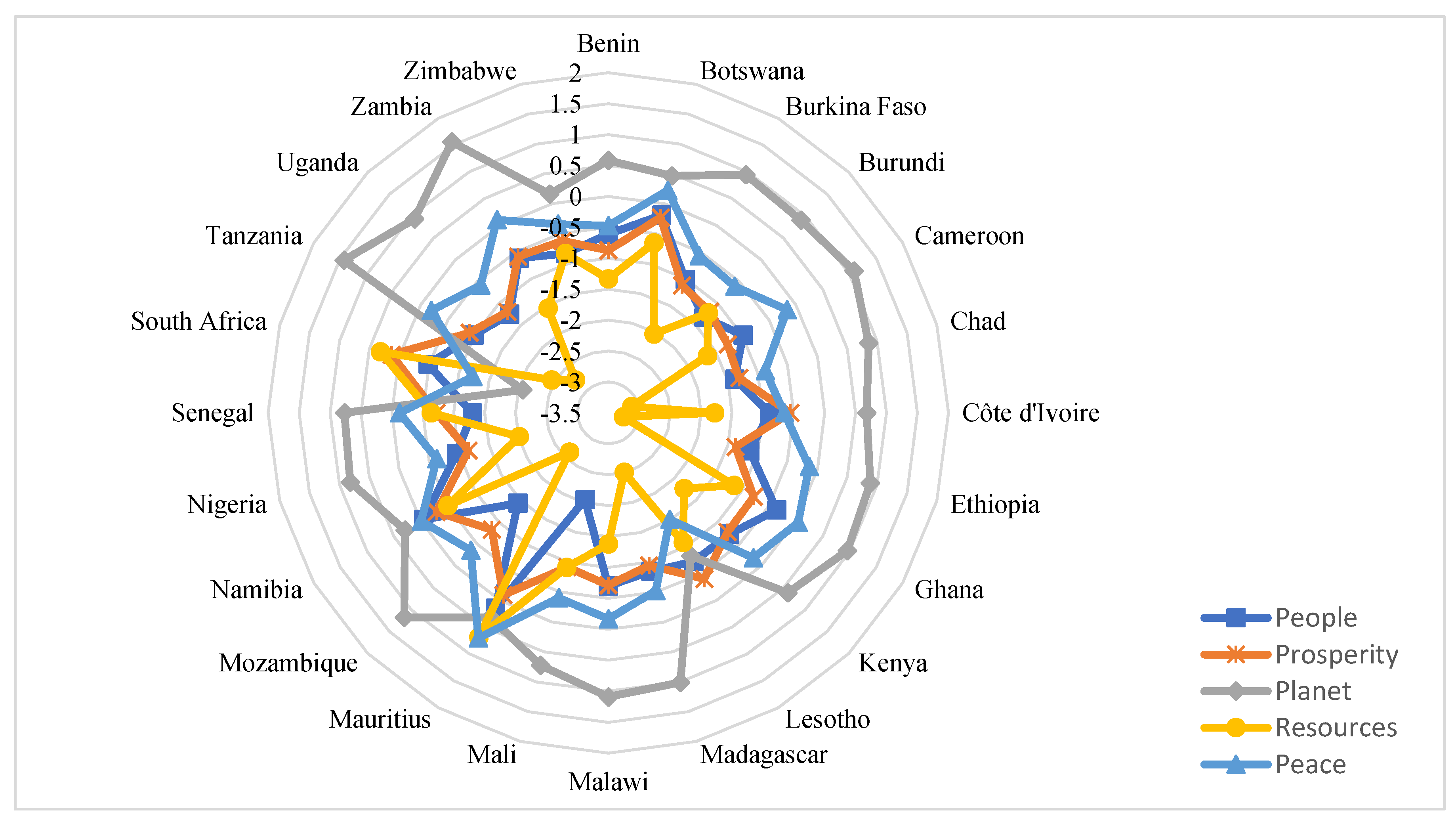

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe. |

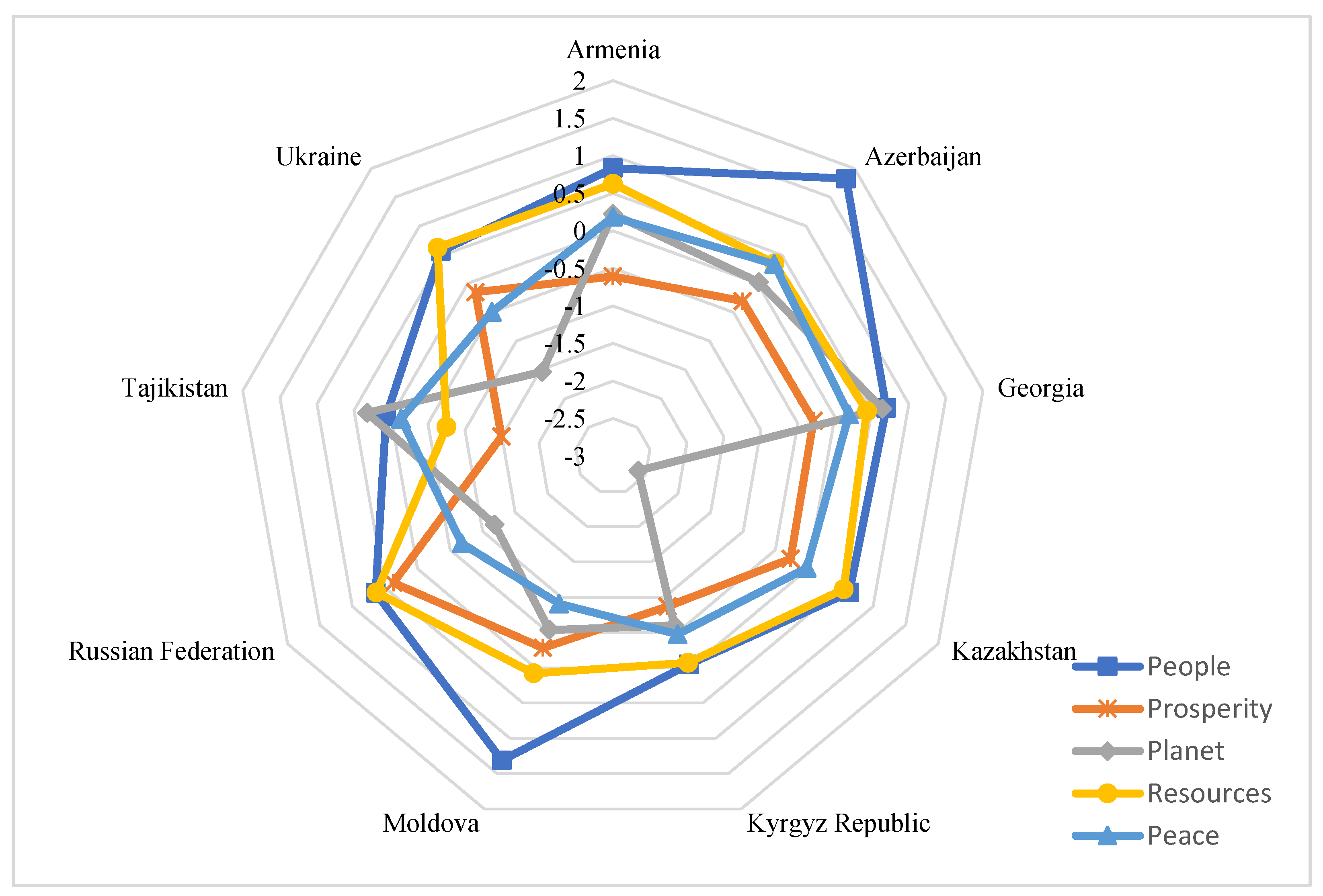

| Commonwealth | Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Ukraine. |

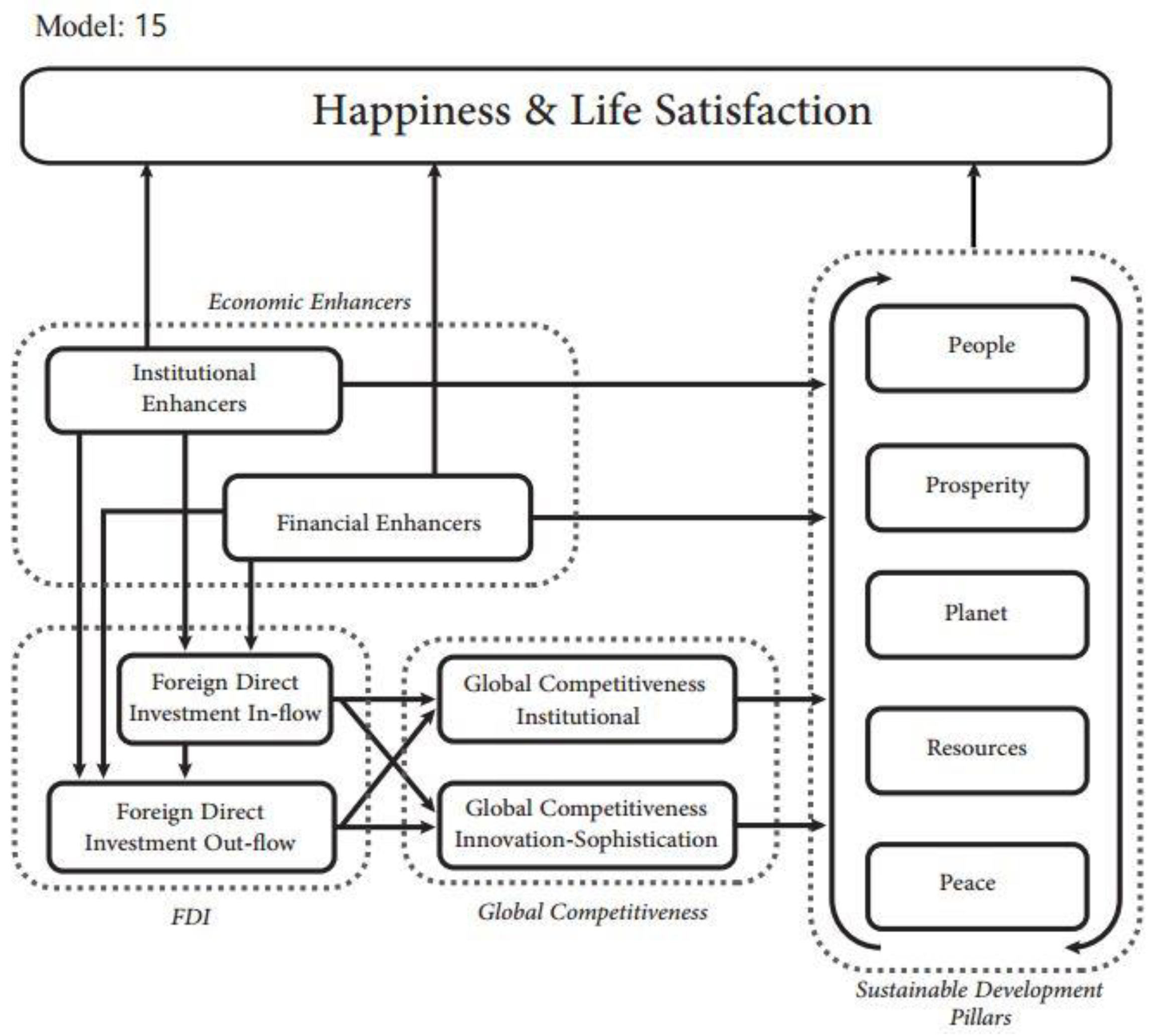

3.3. Model selection

3.4. Creating scores for 129 countries for the relationships among SD pillars and H&LS and country outlier determination.

3.5. Assessment of selected models.

| Model 4 | Model 7 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.251, p<0.001 | 0.186, p<0.001 | 0.225, p<0.001 | 0.170, p<0.001 |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | 0.430, p<0.001 | 0.569, p<0.001 | 0.409, p<0.001 | 0.478, p<0.001 |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | 3.598 | 3.598 | 3.421 | 3.421 |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | 0.510 | 0.560 | 0.511 | 0.552 |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | 0.953 | 0.987 | 0.953 | 0.985 |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Global level results

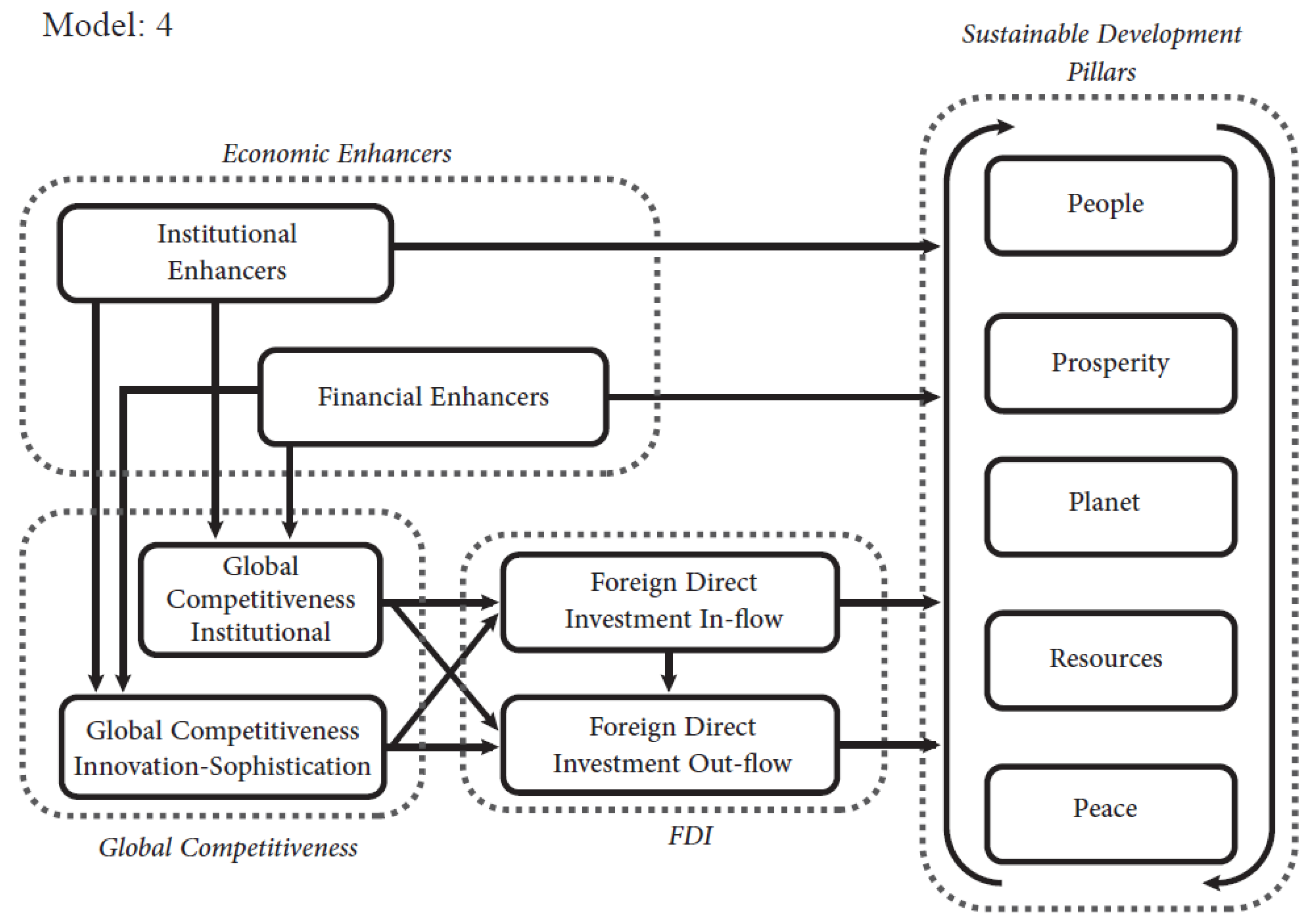

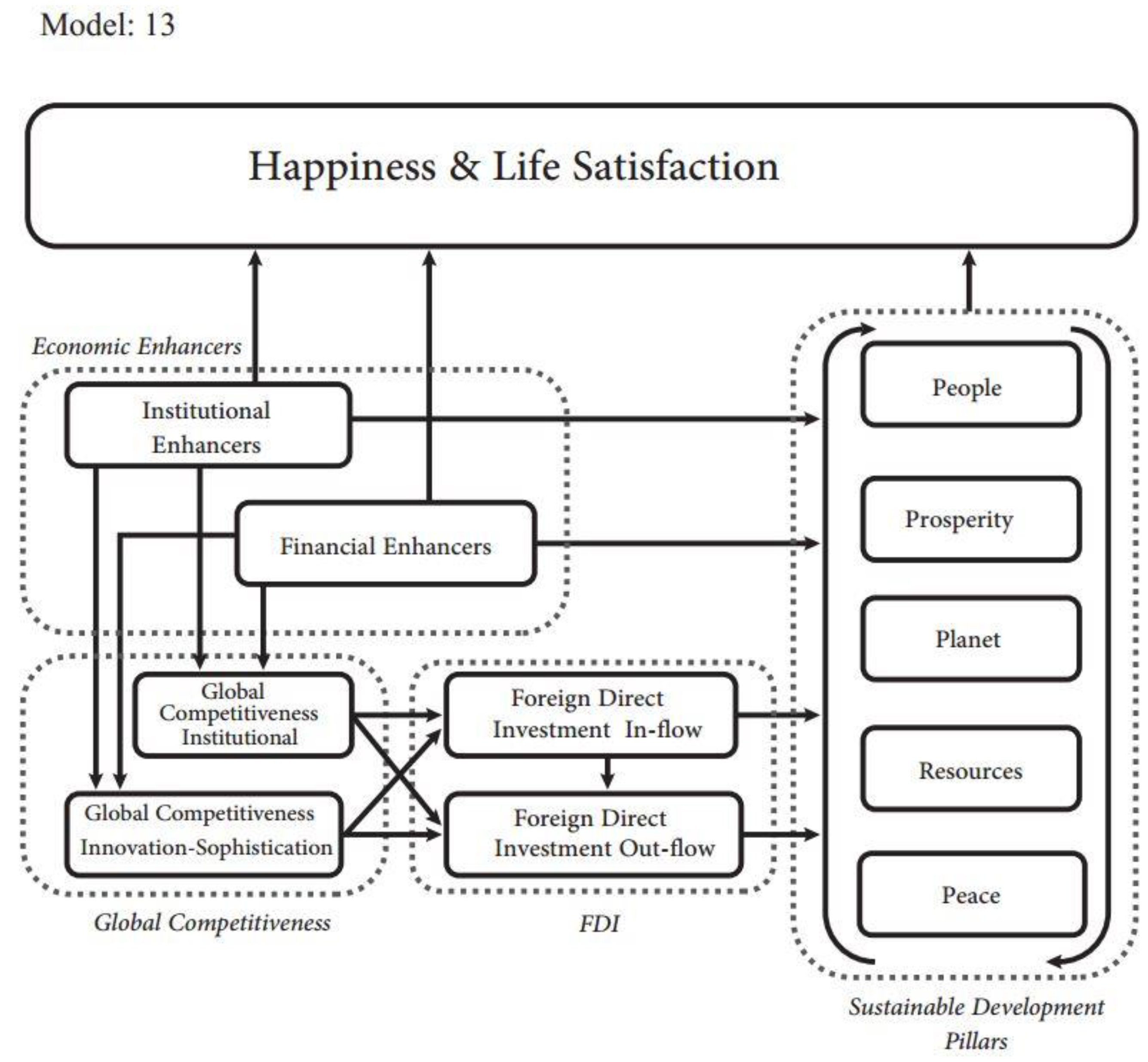

4.1.1. Global level results for “Social-turn 1” models (Models 4 and 13)

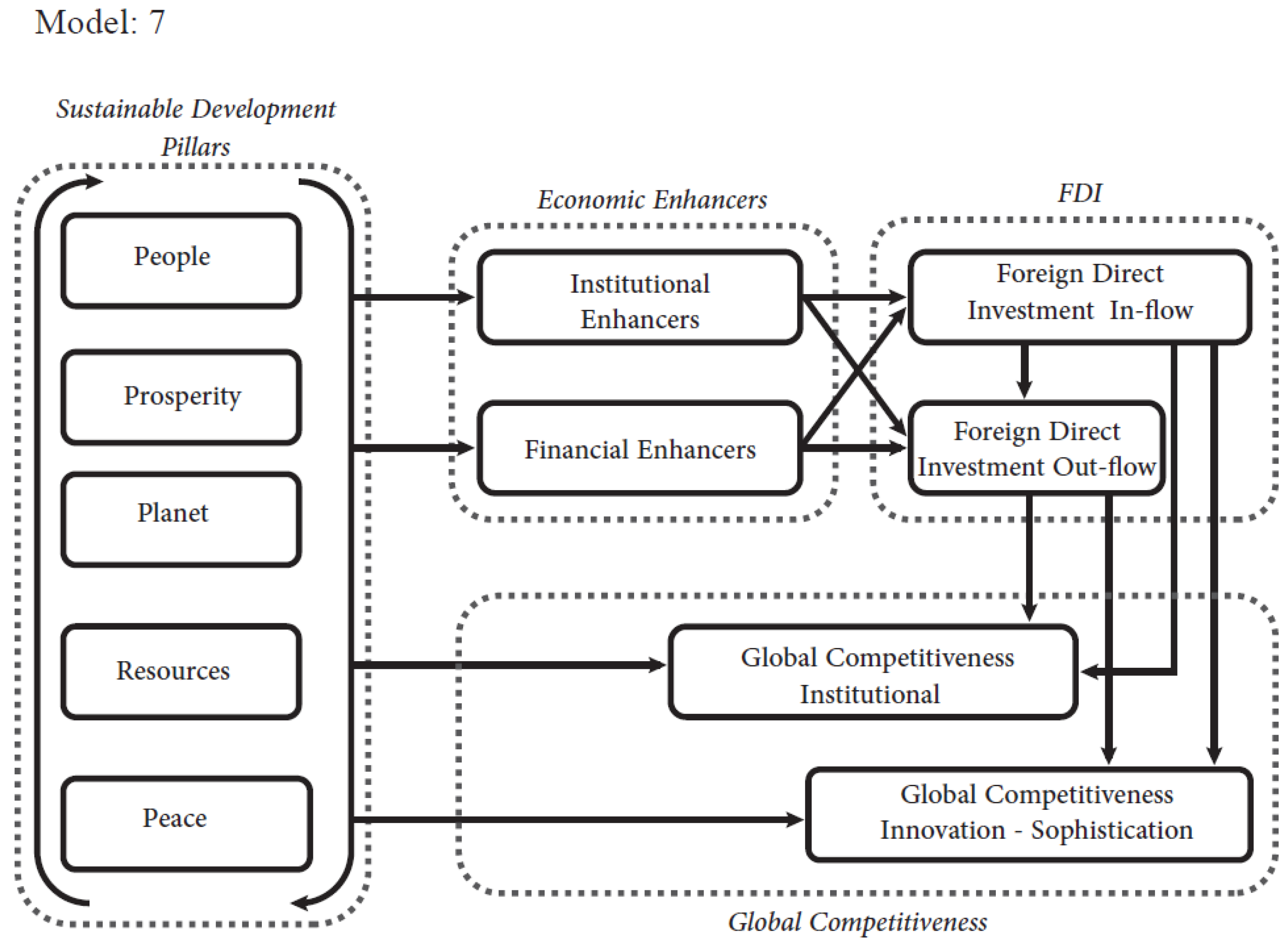

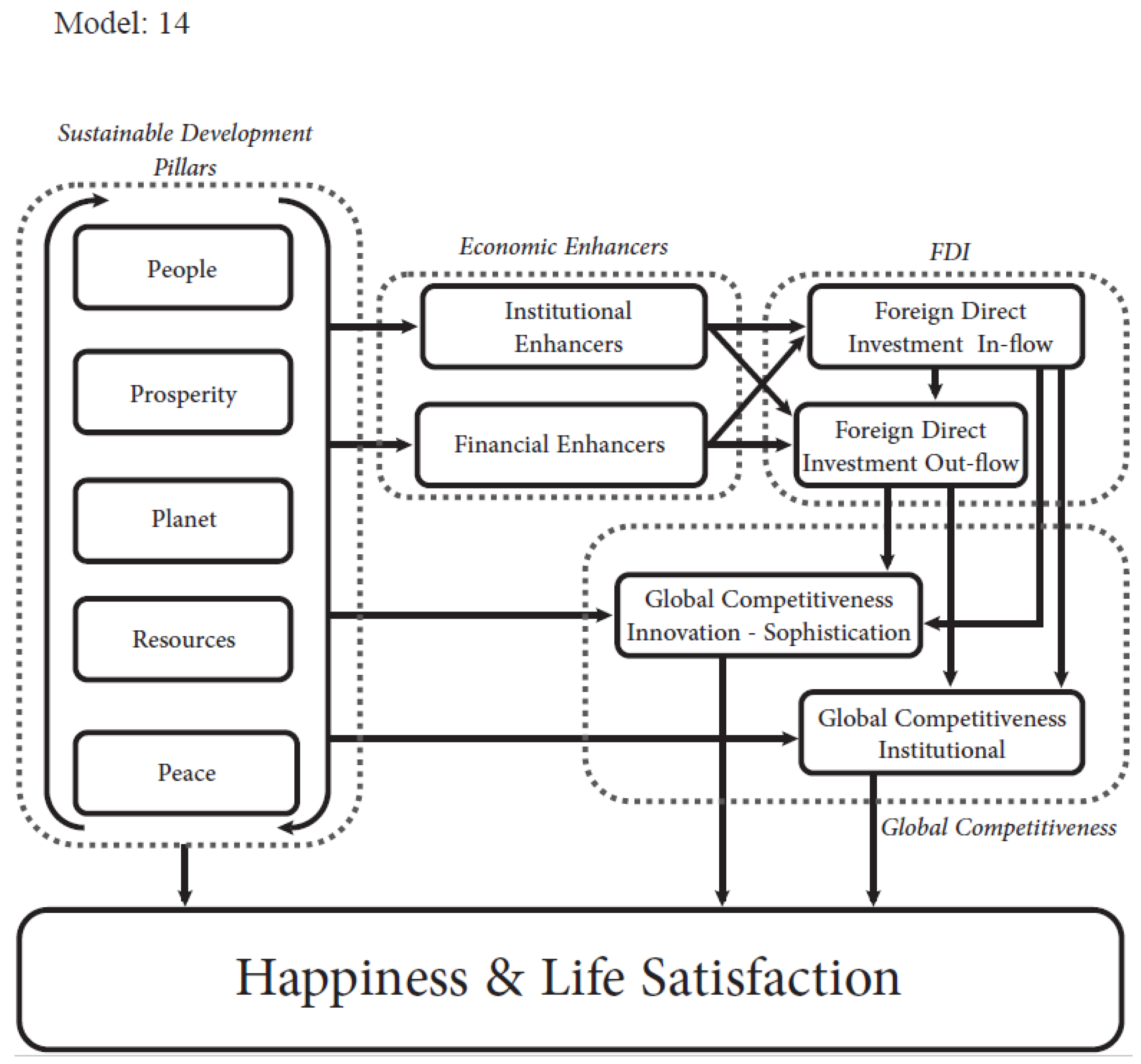

4.1.2. Global level results for “Social-turn 2” (Models 7 and 14)

| Relationships |

Model 4 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 7 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 13 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 14 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

| People → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.020 0.022 / 0.010 |

0.372*** 0.202 / 0.101^ |

0.020 0.222 / 0.10 |

| People → GC-InnS | N/A | -0.026 -0.024 / 0.012 |

0.596*** 0.213 / 0.142^ |

-0.164 -0.024 / 0.012 |

| People → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.029 0.029 / 0.008 |

0.037 0.036 / 0.011 |

| Prosperity → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.276*** 0.296 / 0.178^^ |

0.530*** 0.102 / 0.052^ |

0.276*** 0.296 / 0.178^^ |

| Prosperity → GC-InnS | N/A | 0.440*** 0.468 / 0.329^^ |

0.669*** 0.678 / 0.426^^^ |

0.440*** 0.468 / 0.329^^^ |

| Prosperity → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.130*** 0.130 / 0.053^ |

0.152*** 0.232 / 0.094^ |

| Planet → GC-Ins | N/A | -0.031 -0.030 / 0.008 |

0.204*** 0.390 / 0.214^^ |

-0.031 -0.030 0.008 |

| Planet → GC-InnS | N/A | -0.006 -0.006 / 0.001 |

0.216*** 0.598 / 0.456^^^ |

-0.006 -0.006 / 0.001 |

| Relationships |

Model 4 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 7 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 13 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 14 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

| Planet → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.153*** 0.153 / 0.002 |

0.054* 0.051 / 0.011 |

| Resources → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.177*** 0.185 / 0.099^ |

0.101*** 0.534 / 0.326^^ |

0.177*** 0.185 / 0.099^ |

| Resources → GC-InnS | N/A | 0.159*** 0.170 / 0.095^ |

0.066*** 0.678 / 0.426^^^ |

0.159*** 0.170 / 0.095^^ |

| Resources → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.241*** 0.241 / 0.091^ |

0.189*** 0.224 / 0.092^ |

| Peace → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.359*** 0.373 / 0.223^^ |

0.029 0.029 / 0.008 |

0.359*** 0.373 / 0.223^^ |

| Peace → GC-InnS | N/A | 0.279*** 0.299 / 0.171^^ |

0.130*** 0.130 / 0.053^ |

0.279*** 0.299 / 0.171^^ |

| Peace → H&LS | N/A | N/A | -0.050* -0.050 / 0.010 |

0.084*** 0.149 / 0.043^ |

| Institutional Enhancers → GC-Ins | 0.832*** | 0.040 / 0.032^ | 0.802*** | 0.040 / 0.049^ |

| Institutional Enhancers → GC-InnS | 0.854*** | 0.061* / 0.049^ | 0.854*** | 0.061* / 0.078^ |

| Institutional Enhancers → FDII | 0.276*** / 0.082^ | 0.265*** | 0.276*** / 0.082^ | 0.265*** |

| Institutional Enhancers → FDIO | 0.329*** / 0.118^ | 0.162*** | 0.329*** / 0.118^ | 0.162*** |

| Institutional Enhancers → People | 0.372*** 0.390 / 0.214^^ |

N/A | 0.372*** 0.390 / 0.214^^ |

N/A |

| Institutional Enhancers → Prosperity | 0.596*** 0.598 / 0.456^^^ |

N/A | 0.596*** 0.598 / 0.456^^^ |

N/A |

| Institutional Enhancers → Planet | -0.342*** -0.361 / 0.085^ |

N/A | -0.342*** -0.361 / 0.085^ |

N/A |

| Institutional Enhancers → Resources | 0.530*** 0.534 / 0.326^ |

N/A | 0.530*** 0.534 / 0.326^ |

N/A |

| Institutional Enhancers → Peace | 0.669*** 0.678 / 0.426^^^ |

N/A | 0.669*** 0.678 / 0.426^^^ |

N/A |

| Institutional Enhancers → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.134*** 0.262 / 0.103^ |

0.011 / 0.004 |

| Financial Enhancers → GC-Ins | 0.016 | 0.004 / 0.002 | 0.016 | 0.004 / 0.002 |

| Financial Enhancers → GC-InnS | 0.074* | -0.003 / 0.002 | -0.074** | -0.003 / 0.002 |

| Financial Enhancers → FDII | -0.011 / 0.003 | 0.040 | -0.011 / 0.003 | 0.040 |

| Financial Enhancers → FDIO | -0.034 / 0.009 | -0.049* | -0.034 / 0.009 | -0.048* |

| Financial Enhancers → People | 0.204*** 0.202 / 0.101^ |

N/A | 0.204*** 0.202 / 0.101^ |

N/A |

| Financial Enhancers → Prosperity | 0.216*** 0.213 / 0.142^ |

N/A | 0.216*** 0.213 / 0.142^ |

N/A |

| Financial Enhancers → Planet | 0.166*** 0.166 / 0.018 |

N/A | 0.166*** 0.166 / 0.018 |

N/A |

| Financial Enhancers → Resources | 0.101*** 0.102 / 0.52^ |

N/A | 0.101*** 0.102 / 0.0.52^ |

N/A |

| Financial Enhancers → Peace | -0.066*** -0.678 / 0.030^ |

N/A | -0.066*** -0.66 / 0.032^ |

N/A |

| Financial Enhancers → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.083*** 0.170 / 0.063^ |

-0.000 / 0.000 |

| FDII → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.102*** | N/A | 0.102*** |

| FDII → GC-InnS | N/A | -0.003 | N/A | -0.003 |

| FDII → FDIO | 0.785*** | 0.787*** | 0.785*** | 0.787*** |

| FDII → People | -0.007 | N/A | -0.007 | N/A |

| FDII → Prosperity | -0.117*** | N/A | -0.117*** | N/A |

| Relationships |

Model 4 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 7 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 13 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

Model 14 Path Coefficients Total Effects / Total Effect Sizes |

| FDII → Planet | -0.089*** | N/A | -0.089*** | N/A |

| FDII → Resources | 0.107*** | N/A | 0.107*** | N/A |

| FDII → Peace | 0.070* | N/A | 0.070* | N/A |

| FDII → H&LS | N/A | N/A | -0.006 / 0.001 | 0.025 / 0.004 |

| FDIO → GC-Ins | N/A | 0.034 | N/A | 0.034 |

| FDIO → GC-InnS | N/A | 0.168*** | N/A | 0.168*** |

| FDIO → People | 0.062* | N/A | 0.062* | N/A |

| FDIO → Prosperity | 0.105*** | N/A | 0.105*** | N/A |

| FDIO → Planet | 0.019 | N/A | 0.019 | N/A |

| FDIO → Resources | -0.077* | N/A | -0.077* | N/A |

| FDIO → Peace | -0.033 | N/A | -0.033 | N/A |

| FDIO → H&LS | N/A | N/A | 0.001 / 0.000 | 0.024 / 0.004 |

| GC-Ins → FDII | 0.154*** | N/A | 0.154*** | N/A |

| GC-Ins → FDIO | -0.180*** | N/A | -0.180*** | N/A |

| GC-Ins → People | -0.005 / 0.002 | N/A | -0.005 / 0.002 | N/A |

| GC-Ins → Prosperity | -0.024 / 0.015 | N/A | -0.024 / 0.015 | N/A |

| GC-Ins → Planet | -0.015 / 0.004 | N/A | -0.015 / 0.004 | N/A |

| GC-Ins → Resources | 0.021 / 0.011 | N/A | 0.021 / 0.011 | N/A |

| GC-Ins → Peace | 0.013 / 0.008 | N/A | 0.013 / 0.008 | N/A |

| GC-Ins → H&LS | N/A | N/A | -0.001 / 0.000 | 0.071** |

| GC-InnS → FDII | 0.179*** | N/A | 0.179*** | N/A |

| GC-InnS → FDIO | 0.299*** | N/A | 0.299*** | N/A |

| GC-InnS → People | 0.026 / 0.012 | N/A | 0.026 / 0.012 | N/A |

| GC-InnS → Prosperity | 0.025 / 0.018 | N/A | 0.025 / 0.018 | N/A |

| GC-InnS → Planet | -0.008 / 0.002 | N/A | -0.008 / 0.002 | N/A |

| GC-InnS → Resources | -0.015 / 0.008 | N/A | -0.015 / 0.008 | N/A |

| GC-InnS → Peace | -0.002 / 0.001 | N/A | -0.002 / 0.001 | N/A |

| GC-InnS → H&LS | N/A | N/A | -0.001 / 0.000 | 0.125*** |

| Notes: Significance Level: *p < 0.05, **p <0.01, ***p< 0.001. Effect Sizes ^ 0.02 < e < 0.15 = Low effect size, ^^ 0.15 < e < 0.35 = Medium effect size, ^^^ e > 0.35 = Strong effect size. N/A: The results of the relationships are not available. | ||||

4.2. Comparison of country clusters (“Social-turn 1.2” (Model 15) and “Social-turn 2” (Model 14)).

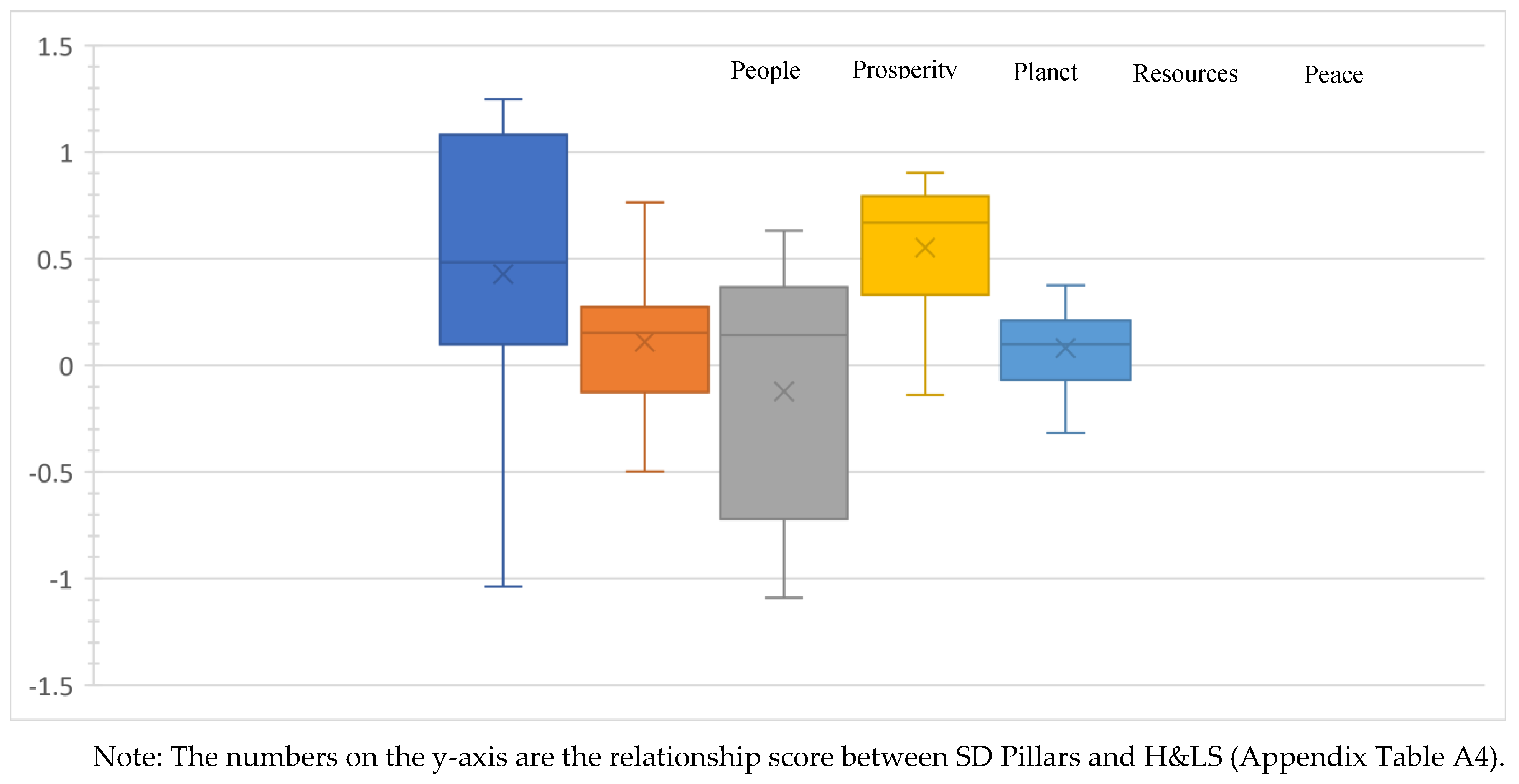

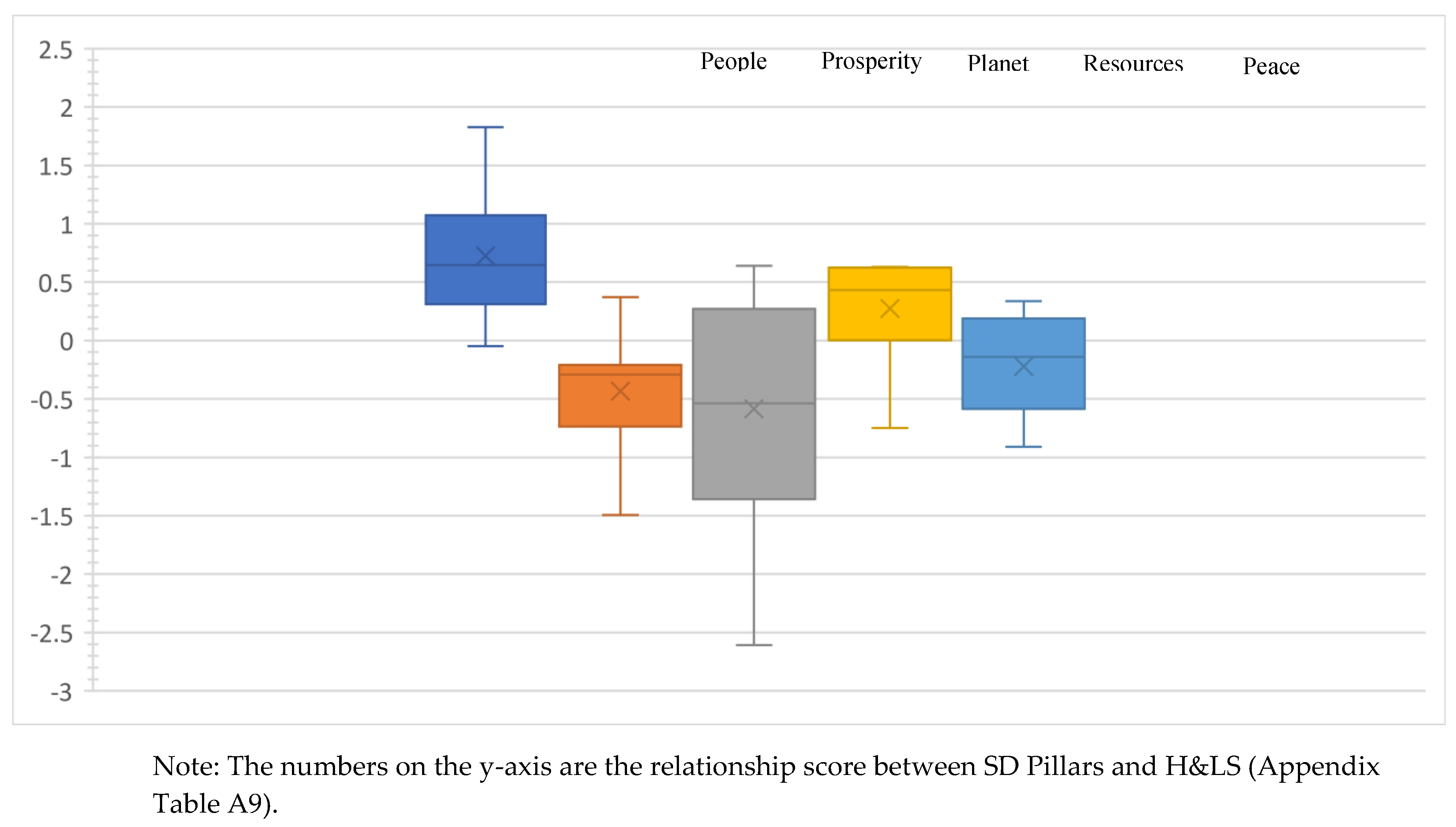

4.3. Country Cluster Level Comparison of SD Pillars’ relationships with H&LS for “Social-turn 1” (Model 13), “Social-turn 1.2” (Model 15), and “Social-turn 2” (Model 14).

4.4. Country-Level Results per Cluster (“Social–turn 2” model)

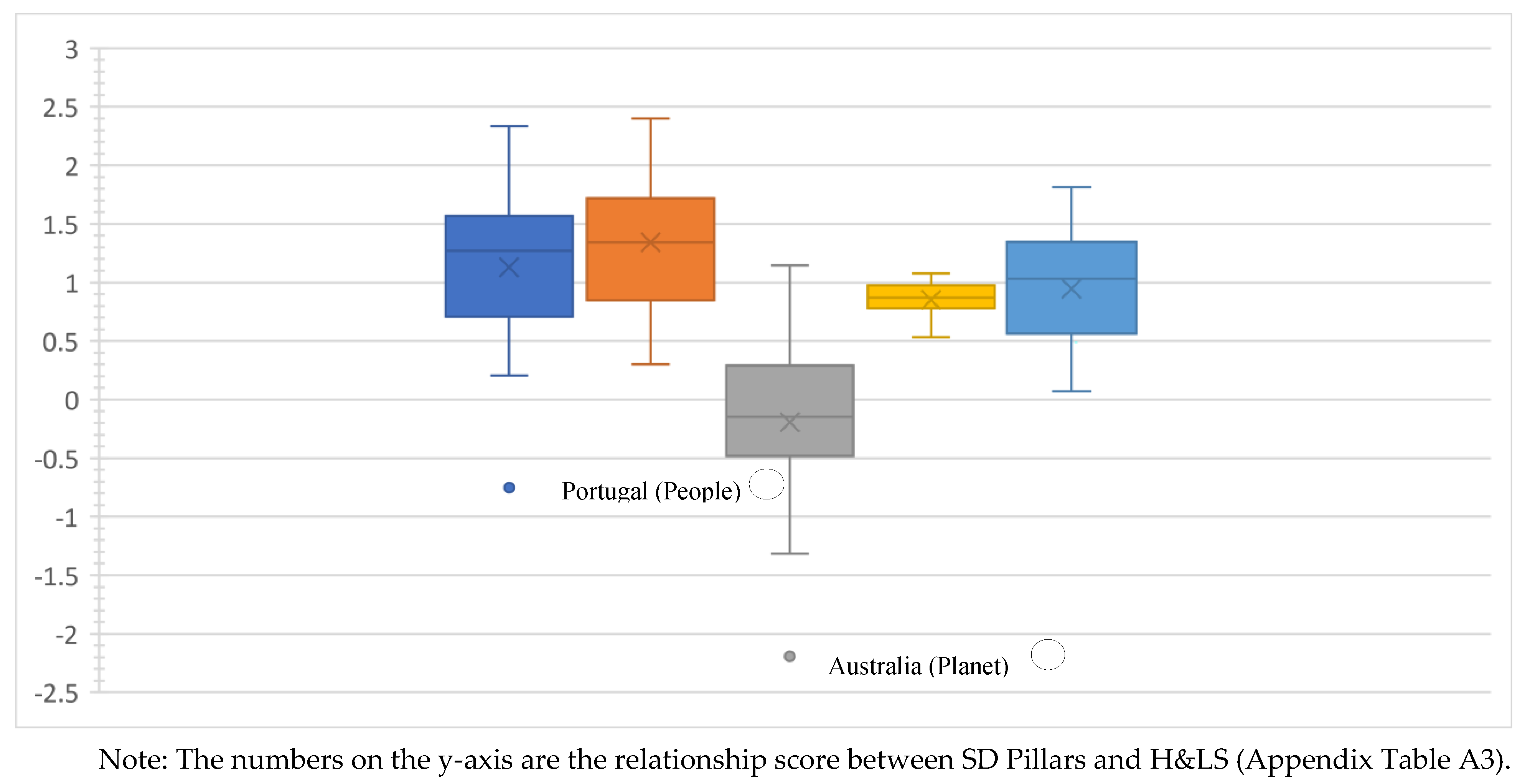

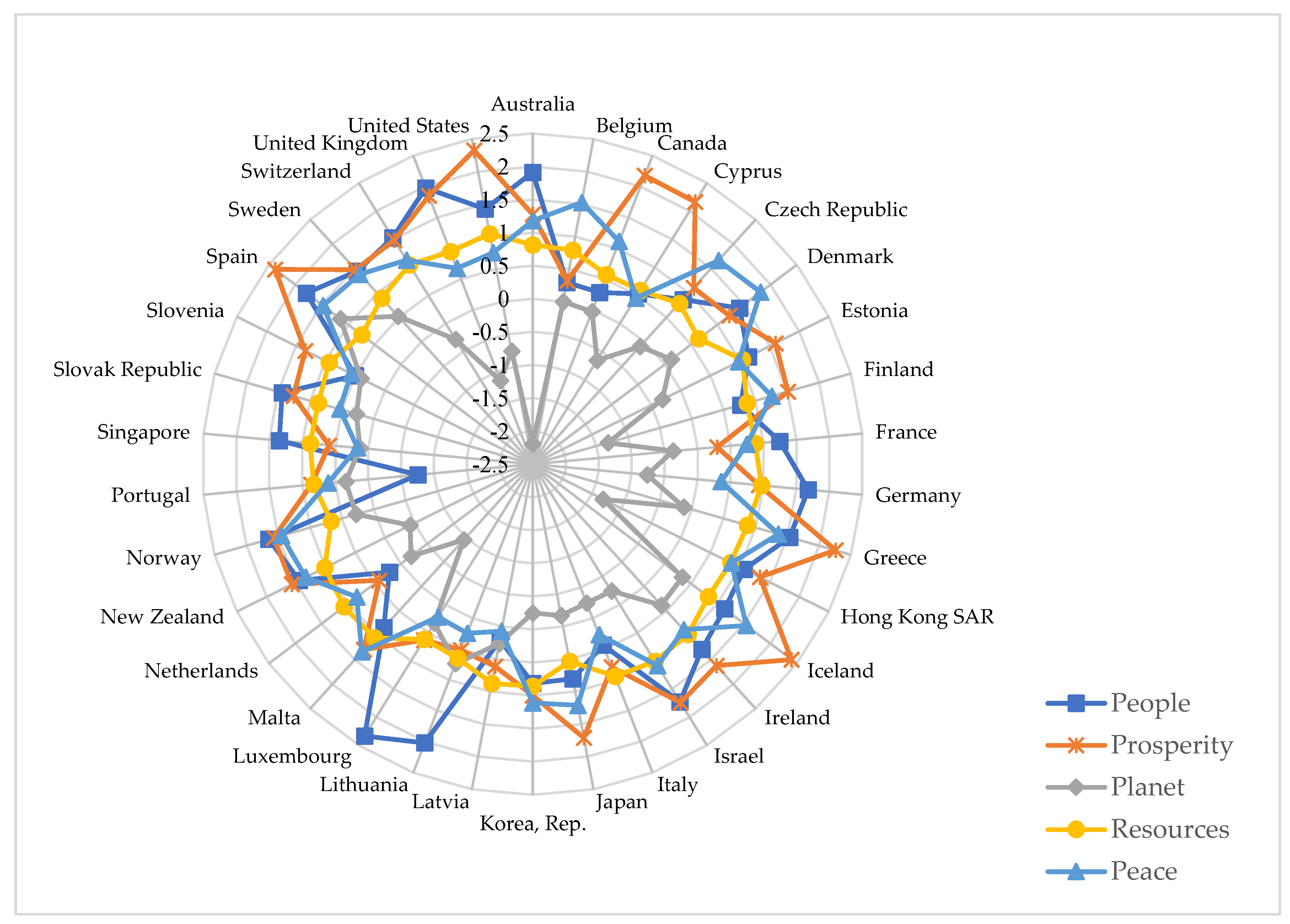

4.4.1. Advanced economies

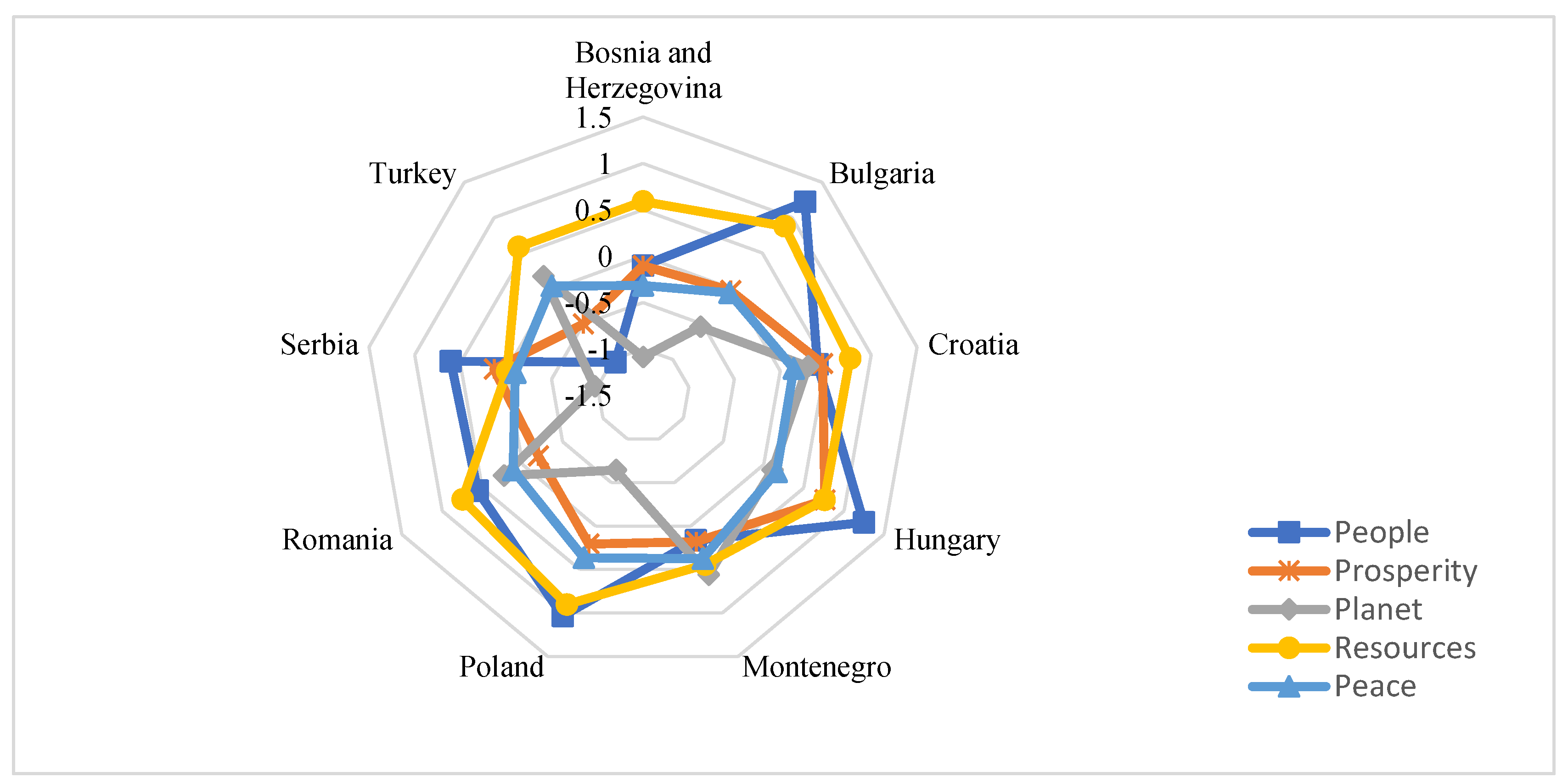

4.4.2. Emerging & Developing Europe

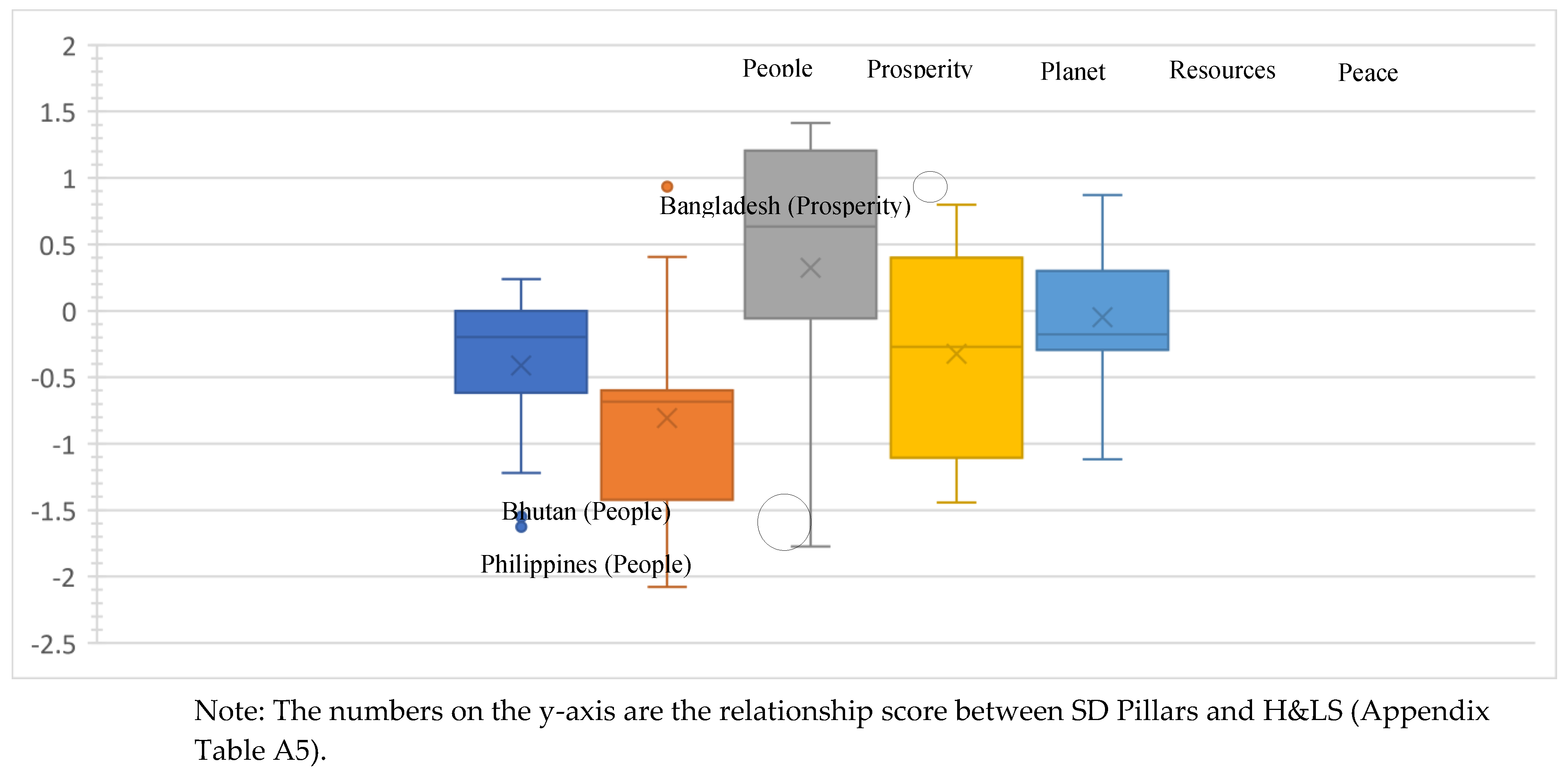

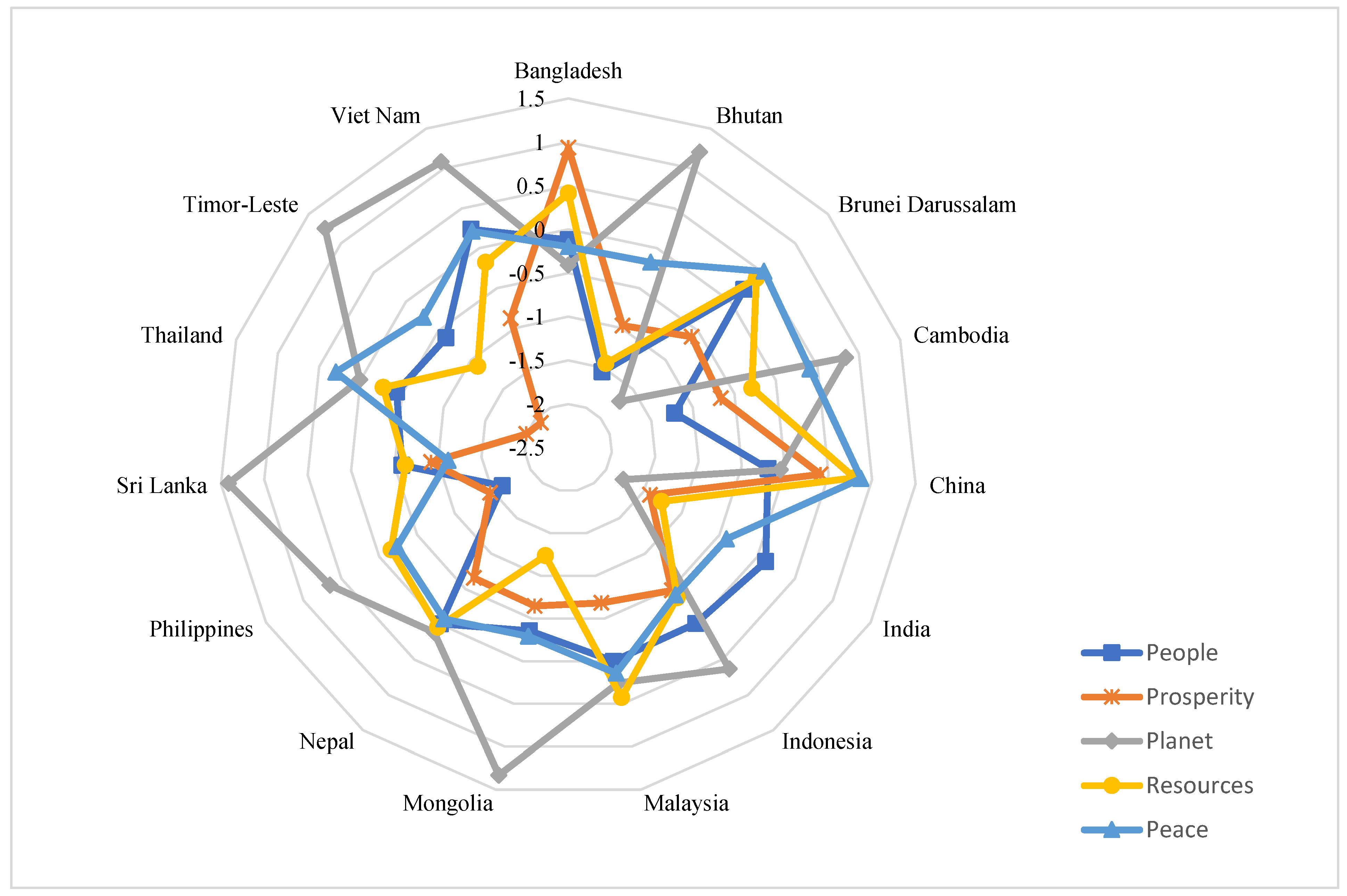

4.4.3. Emerging & Developing Asia

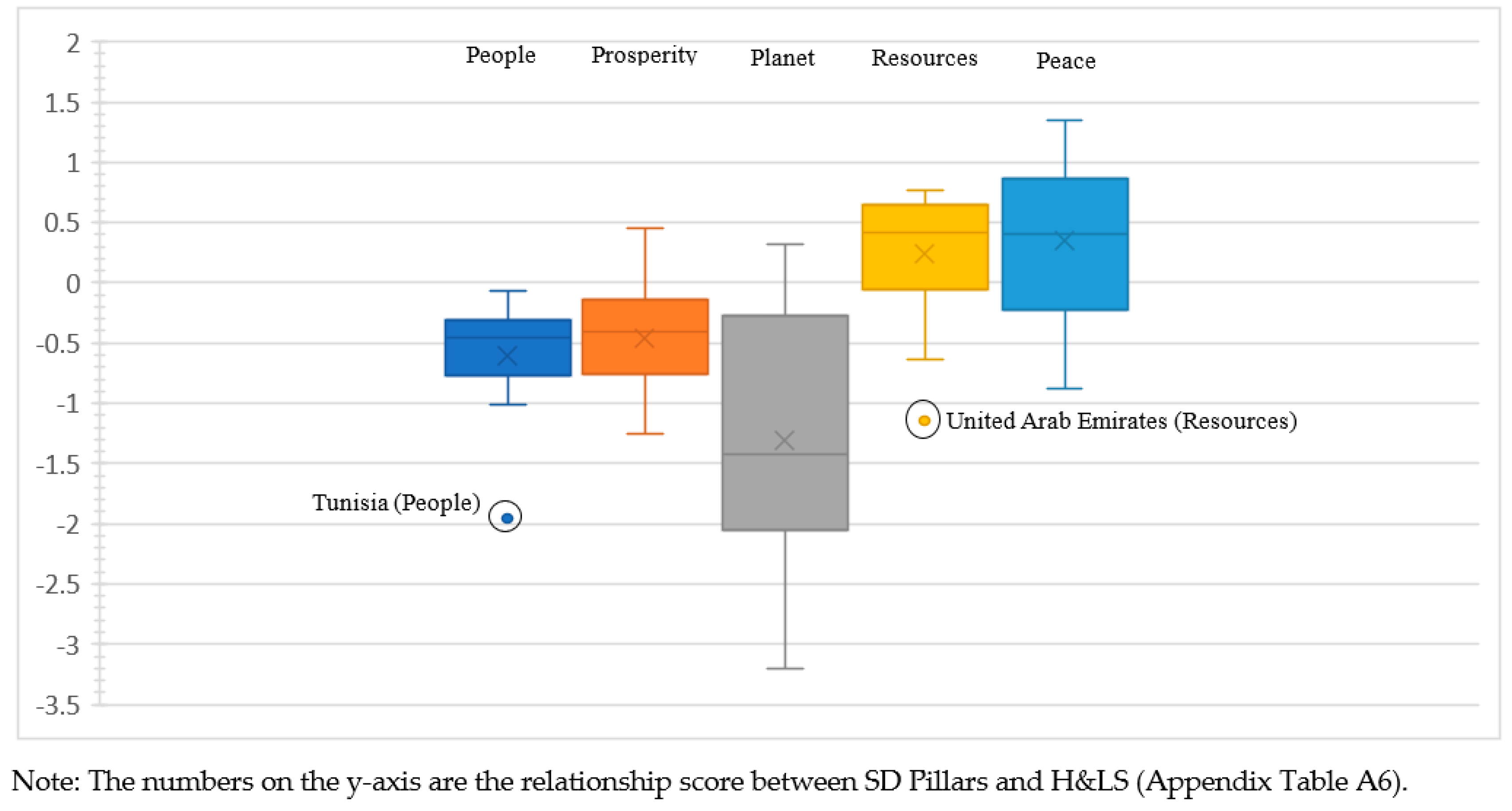

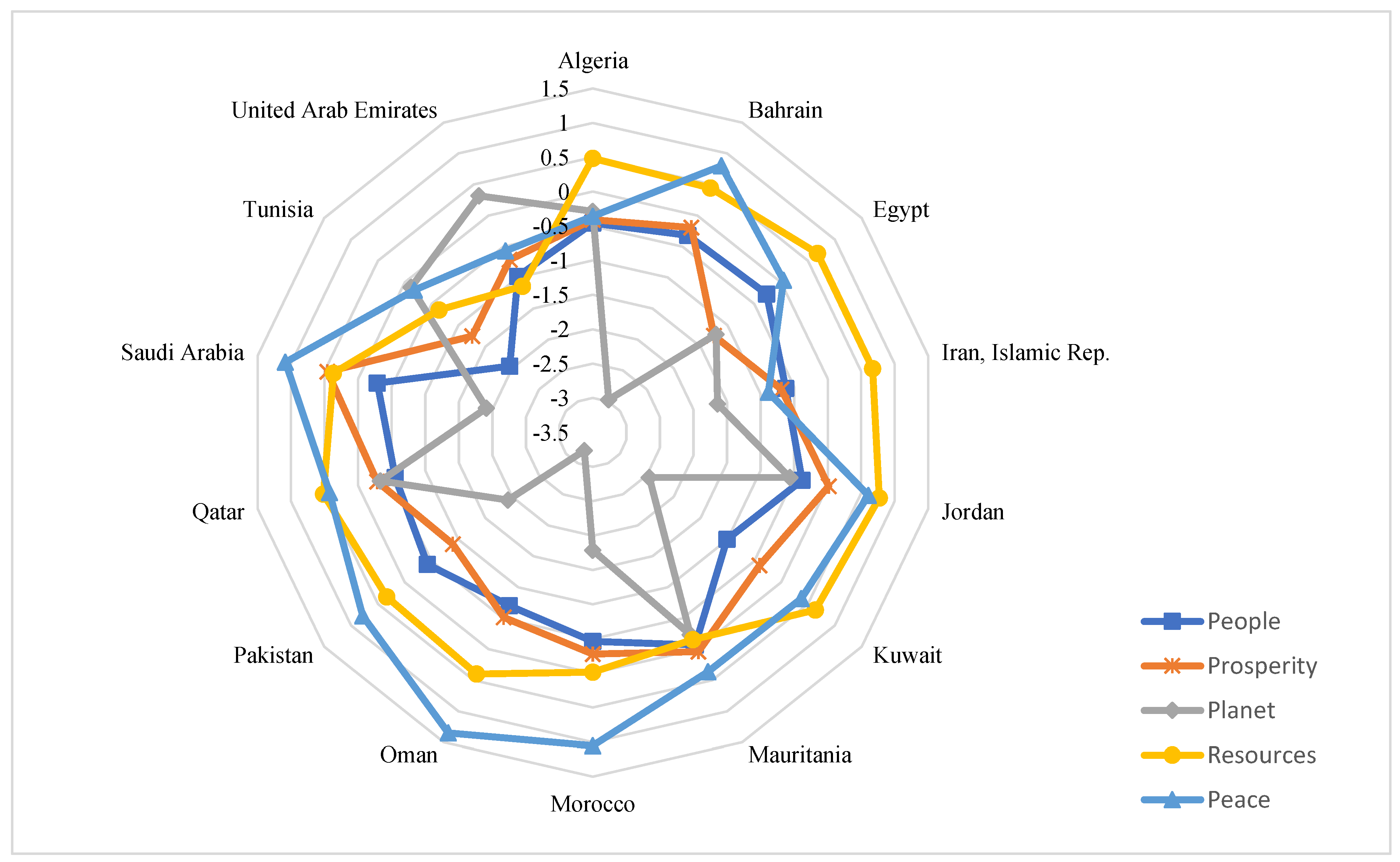

4.4.4. Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan

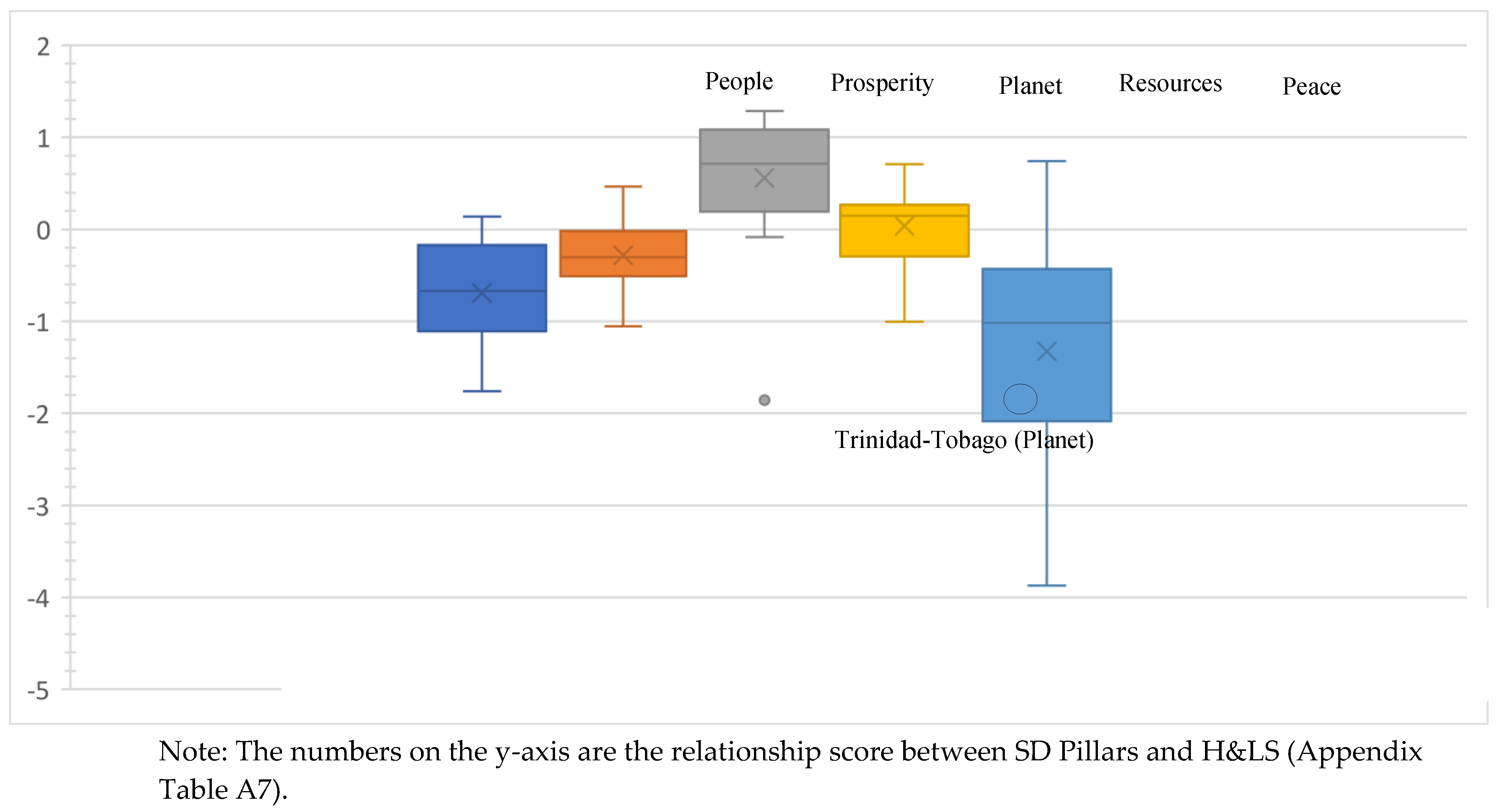

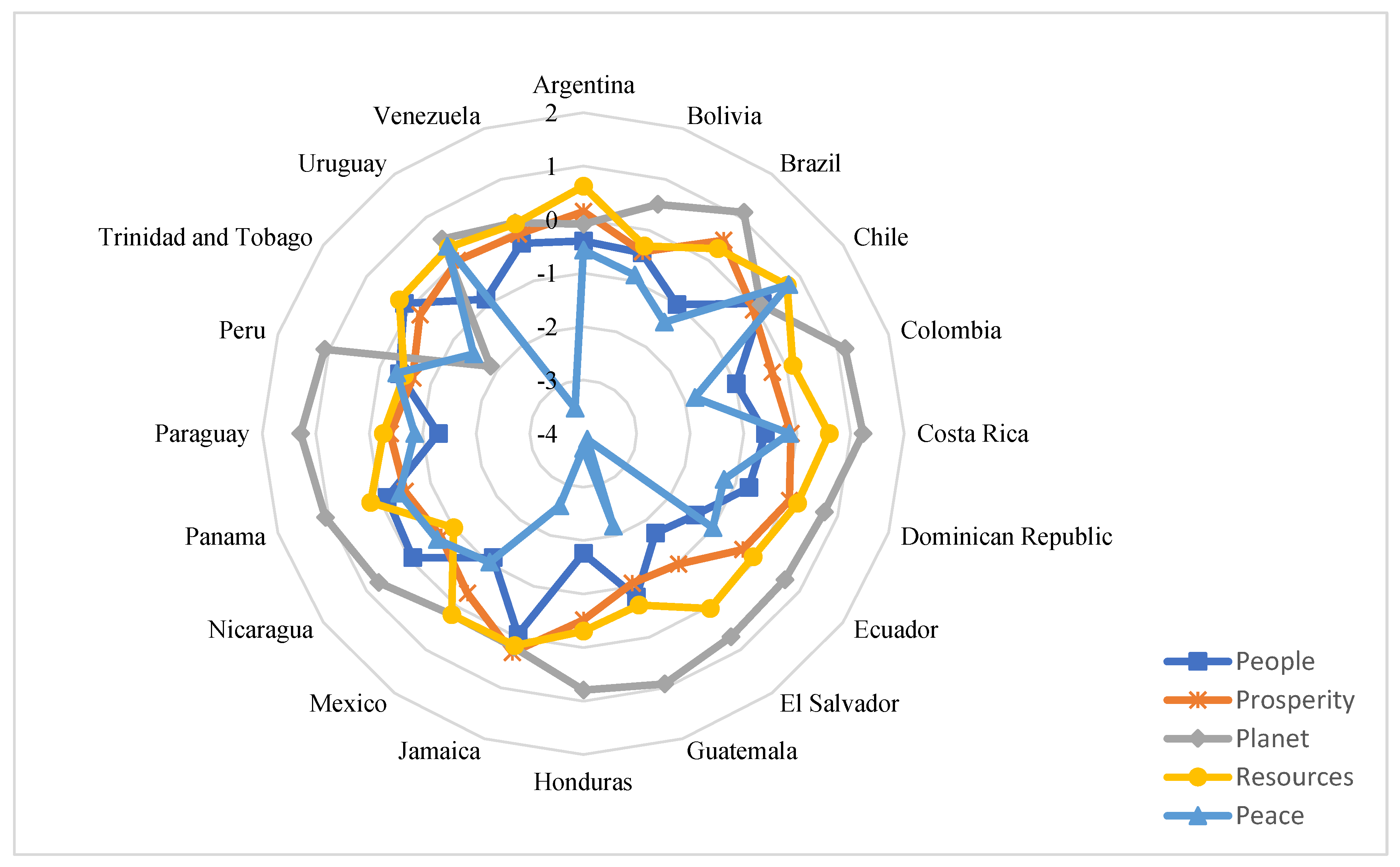

4.4.5. Latin America & the Caribbean

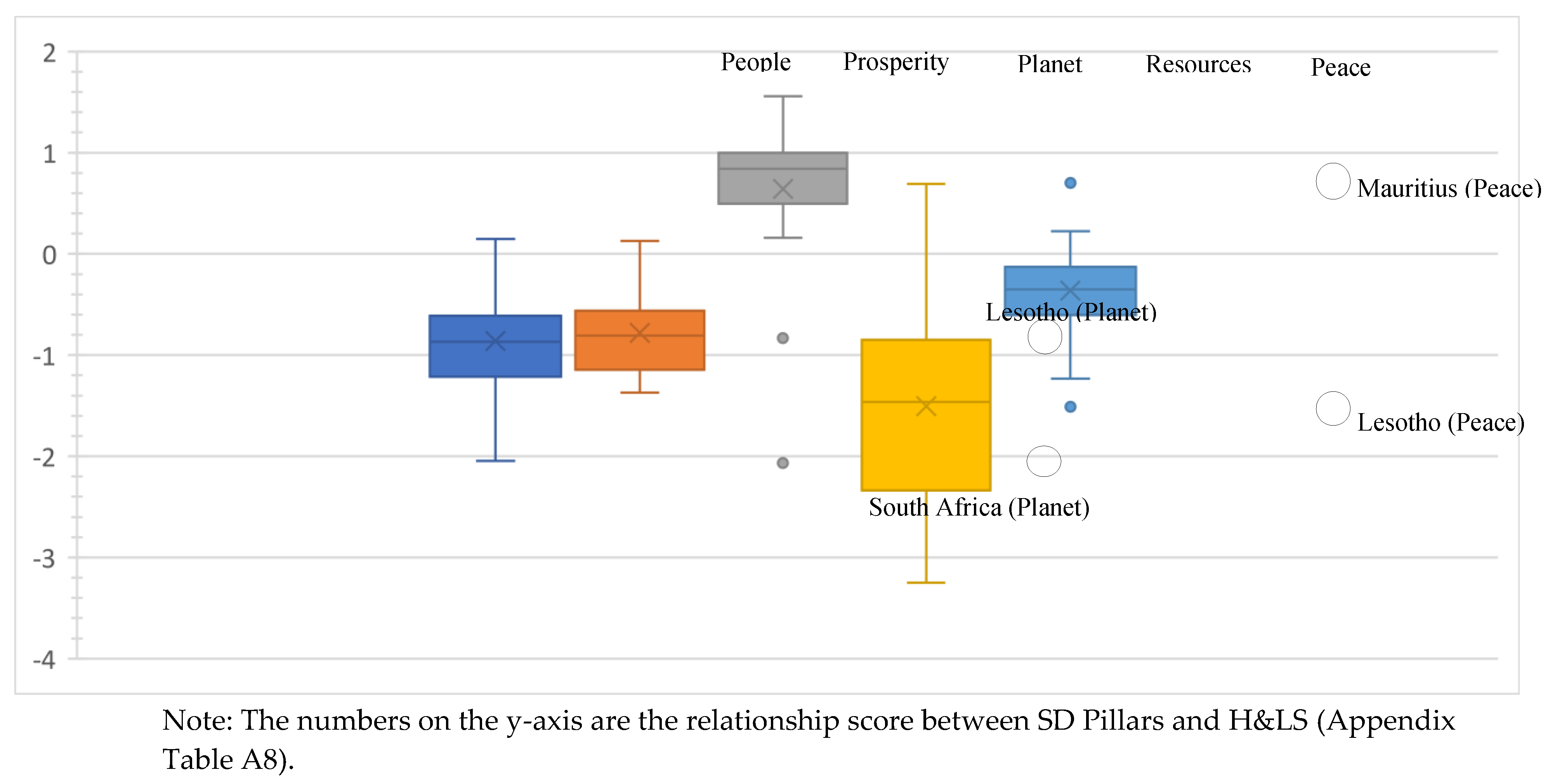

4.4.6. Sub-Saharan Africa

4.4.7 Commonwealth

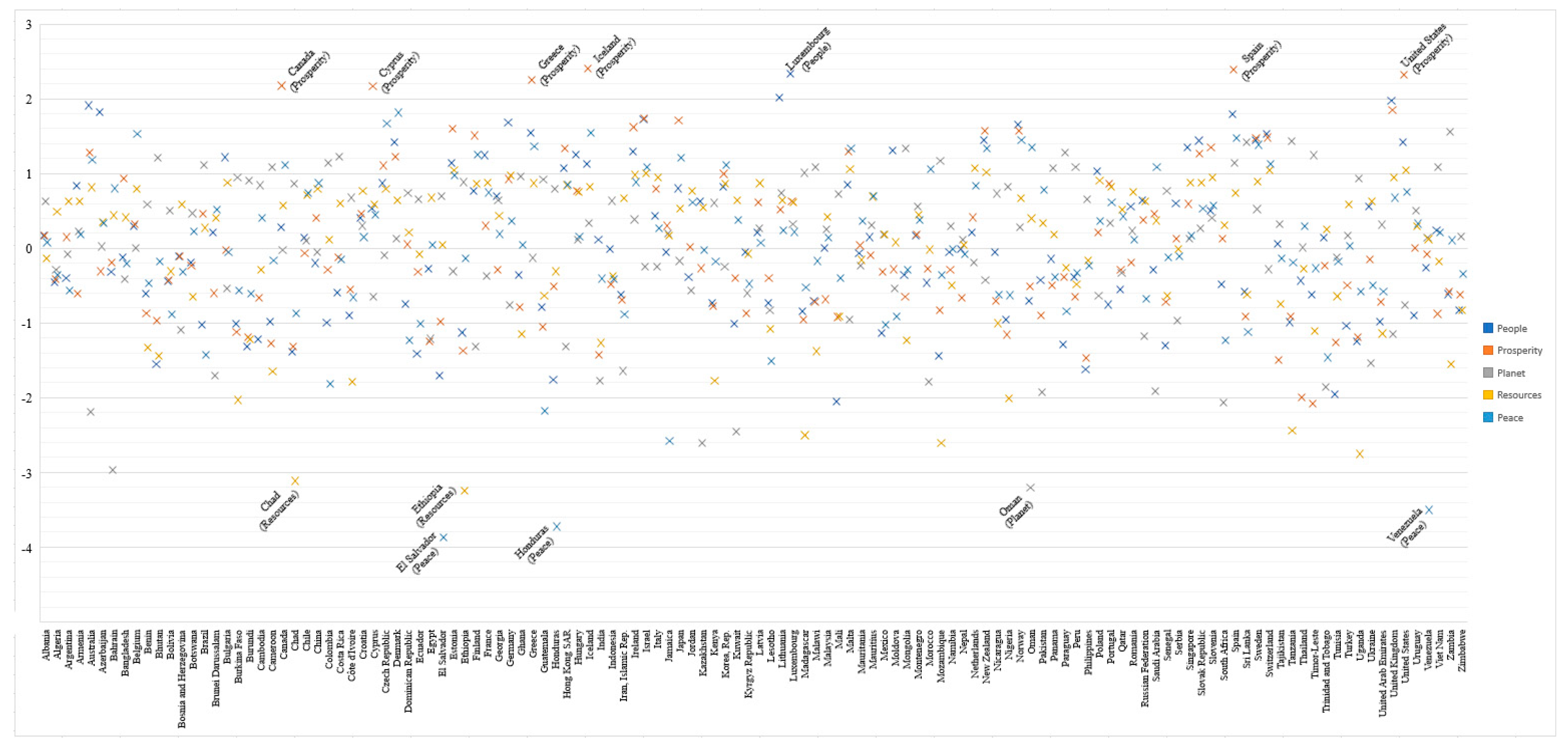

4.4.8. Country outliers, globally and per country cluster

5. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

5.1. Theoretical implications

5.2. Practical implications

5.3. Limitations and future research

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Global Competitiveness (Institutional) (41) | |

| Higher Education and Training |

Secondary education enrollment, gross %* |

| Tertiary education enrollment, gross %* | |

| Quality of the education system, 1-7 (best) | |

| Quality of math and science education, 1-7 (best) | |

| Quality of management schools, 1-7 (best) | |

| Internet access in schools, 1-7 (best) | |

| Availability of research and training services, 1-7 (best) | |

| Extent of staff training, 1-7 (best) | |

| Goods Market Efficiency |

Intensity of local competition, 1-7 (best) |

| Extent of market dominance, 1-7 (best) | |

| Effectiveness of anti-monopoly policy, 1-7 (best) | |

| No. procedures to start a business* | |

| No. days to start a business* | |

| Agricultural policy costs, 1-7 (best) | |

| Total tax rate, % profits* | |

| Prevalence of trade barriers, 1-7 (best) | |

| Prevalence of foreign ownership, 1-7 (best) | |

| Business impact of rules on FDI, 1-7 (best) | |

| Table A1.Cont. | |

| Goods Market Efficiency |

Burden of customs procedures, 1-7 (best) |

| Imports as a percentage of GDP* | |

| Trade tariffs, % duty* | |

| Degree of customer orientation, 1-7 (best) | |

| Buyer sophistication, 1-7 (best) | |

| Labor Market Efficiency |

Cooperation in labor-employer relations, 1-7 (best) |

| Hiring and firing practices, 1-7 (best) | |

| Flexibility of wage determination, 1-7 (best) | |

| Redundancy costs, weeks of salary* | |

| Pay and productivity, 1-7 (best) | |

| Reliance on professional management, 1-7 (best) | |

| Women in labor force, ratio to men* | |

| Financial Market Efficiency |

Financing through local equity market, 1-7 (best) |

| Ease of access to loans, 1-7 (best) | |

| Venture capital availability, 1-7 (best) | |

| Soundness of banks, 1-7 (best) | |

| Regulation of securities exchanges, 1-7 (best) | |

| Technological Readiness |

Legal rights index, 0–10 (best)* |

| Availability of latest technologies, 1-7 (best) | |

| Firm-level technology absorption, 1-7 (best) | |

| FDI and technology transfer, 1-7 (best) | |

| Individuals using Internet, %* | |

| Fixed broadband Internet subscriptions/100 pop. * | |

| Global Competitiveness (Innovation Sophistication) (14) | |

| Business Sophistication |

Local supplier quantity, 1-7 (best) |

| Local supplier quality, 1-7 (best) | |

| State of cluster development, 1-7 (best) | |

| Nature of competitive advantage, 1-7 (best) | |

| Production process sophistication, 1-7 (best) | |

| Control of international distribution, 1-7 (best) | |

| Extent of marketing, 1-7 (best) | |

| Value chain breadth, 1-7 (best) | |

| Innovation | Capacity for innovation, 1-7 (best) |

| Quality of scientific research institutions, 1-7 (best) | |

| Company spending on R&D, 1-7 (best) | |

| University-industry collaboration in R&D, 1-7 (best) | |

| Gov’t procurement of advanced tech products, 1-7 (best) | |

| Available of scientists and engineers, 1-7 (best) | |

| Economic Enhancers (Institutional) (4) | |

| Business Freedom | |

| Table A1. Cont. | |

| Property Rights | |

| Government Integrity | |

| Judicial Effectiveness | |

| Economic Enhancers (Financial) (5) | |

| Government Spending | |

| Monetary Freedom | |

| Trade Freedom | |

| Investment Freedom | |

| Financial Freedom | |

| Foreign Direct Investment | |

| FDI IN % of the GDP and Annual USD | |

| FDI OUT % of the GDP and Annual USD | |

| Sustainable Development Dimension (People) (7) | |

| SDG1 | Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of the population) |

| Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of the population) | |

| SDG3 | Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate per 100,000 live births) |

| SDG4 | Educational attainments, at least completed upper secondary, population 25+, total (%) (cumulative) |

| Educational attainment, at least completed post-secondary, population 25+, total (%) (cumulative) | |

| Educational attainment, at least completed lower secondary, population 25+, total (%) (cumulative) | |

| SDG5 | Women Business and the Law Index Score (scale 1-100) |

| Sustainable Development Dimension (Prosperity) (6) | |

| SDG8 | GDP per capita growth (annual %) |

| Unemployment, total (% of the total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) | |

| SDG9 | Research and development expenditure (% of GDP) |

| Individuals using the Internet (% of the population) | |

| SDG10 | Adjusted net savings, excluding particulate emission damage (% of GNI) |

| SDG11 | PM2.5 air pollution, mean annual exposure (micrograms per cubic meter) |

| Sustainable Development Dimension (Planet) (4) | |

| SDG13 | CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) |

| SDG14 | CO2 emissions (kg per PPP $ of GDP) |

| SDG15 | Forest area (% of land area) |

| Annual freshwater withdrawals, total (% of internal resources) | |

| Sustainable Development Dimension (Resources) (5) | |

| SDG2 | Prevalence of undernourishment (% of the population) |

| SDG6 | People using at least basic drinking water services, rural (% of rural population) |

| People using at least basic drinking water services, urban (% of urban population) | |

| People using safely managed drinking water services (% of the population) | |

| Table A1. Cont. | |

| SDG7 | Renewable energy consumption (% of total final energy consumption) |

| Sustainable Development Dimension (Peace) (19) | |

| SDG16 | Intentional homicides (per 100,000 people) |

| SDG17 (adjusted average of following indicators) |

Property rights, 1-7 (best) |

| Intellectual property protection, 1-7 (best) | |

| Diversion of public funds, 1-7 (best) | |

| Public trust in politicians, 1-7 (best) | |

| Judicial independence, 1-7 (best) | |

| Favoritism in decisions of government officials, 1-7 (best) | |

| Wastefulness of government spending, 1-7 (best) | |

| Burden of government regulation, 1-7 (best) | |

| Transparency of government policymaking, 1-7 (best) | |

| Business costs of terrorism, 1-7 (best) | |

| Business costs of crime and violence, 1-7 (best) | |

| Organized crime, 1-7 (best) | |

| Reliability of police services, 1-7 (best) | |

| Ethical behavior of firms, 1-7 (best) | |

| Strength of auditing and reporting standards, 1-7 (best) | |

| Efficacy of corporate boards, 1-7 (best) | |

| Protection of minority shareholders’ interests, 1-7 (best) | |

| Strength of investor protection, 0–10 (best)* | |

| Happiness & Life Satisfaction | |

| Adjusted to 100 (score) Life Satisfaction in Cantril Ladder (Helliwell, Huang, & Wang, 2019) (The underlying source of the happiness scores in the World Happiness Report is the Gallup World Poll—a set of nationally representative surveys undertaken in more than 160 countries in over 140 languages. The main life evaluation question asked in the poll is: “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” (Also known as the “Cantril Ladder.”) |

|

| Populations | Percentages | GDP | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Economies | 977,693,601.00 | 15.76057015 | 36,083,063,161,670.50 | 54.14794 |

| Emerging Europe | 164,754,708.00 | 2.655871052 | 1,880,760,824,314.84 | 2.822358 |

| Emerging Asia | 3,208,431,222.00 | 51.72040125 | 16,993,899,236,746.00 | 25.50184 |

| Middle East | 475,969,475.00 | 7.672700622 | 5,467,148,817,836.51 | 8.204261 |

| Latin America | 542,274,035.00 | 8.741540254 | 3,752,384,843,371.03 | 5.631005 |

| Sub Saharan | 598,914,908.00 | 9.654599776 | 849,177,983,890.26 | 1.274316 |

| Commonwealth | 235,377,230.00 | 3.794316892 | 1,611,488,033,222.07 | 2.418275 |

| Clusters Total | 6,203,415,179.00 | 66,637,922,901,051.30 | ||

| World | 6,674,000,000.00 | 67,500,000,000,000.00 | ||

| % Of World | 92.94% | 98.72% |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1.913 | 1.278 | -2.192 | 0.816 | 1.179 |

| Belgium | 0.296 | 0.319 | 0 | 0.79 | 1.526 |

| Canada | 0.285 | 2.177 | -0.026 | 0.569 | 1.114 |

| Cyprus | 0.529 | 2.164 | -0.652 | 0.59 | 0.453 |

| Czech Republic | 0.87 | 1.108 | -0.092 | 0.79 | 1.665 |

| Denmark | 1.414 | 1.224 | 0.127 | 0.644 | 1.814 |

| Estonia | 1.144 | 1.599 | -0.309 | 1.04 | 0.976 |

| Finland | 0.768 | 1.509 | -1.318 | 0.869 | 1.257 |

| France | 1.247 | 0.301 | -0.372 | 0.878 | 0.747 |

| Germany | 1.68 | 0.928 | -0.763 | 0.973 | 0.36 |

| Greece | 1.539 | 2.257 | -0.127 | 0.872 | 1.361 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 1.072 | 1.336 | -1.312 | 0.844 | 0.853 |

| Iceland | 1.131 | 2.4 | 0.333 | 0.823 | 1.547 |

| Ireland | 1.291 | 1.62 | 0.384 | 0.981 | 0.886 |

| Israel | 1.727 | 1.742 | -0.241 | 1.007 | 1.083 |

| Italy | 0.432 | 0.792 | -0.249 | 0.943 | 0.269 |

| Japan | 0.802 | 1.711 | -0.169 | 0.535 | 1.21 |

| Korea, Rep. | 0.817 | 0.997 | -0.247 | 0.859 | 1.111 |

| Latvia | 0.207 | 0.612 | 0.262 | 0.871 | 0.071 |

| Lithuania | 2.021 | 0.512 | 0.736 | 0.646 | 0.241 |

| Luxembourg | 2.334 | 0.629 | 0.328 | 0.614 | 0.218 |

| Malta | 0.848 | 1.293 | -0.949 | 1.054 | 1.341 |

| Netherlands | 0.214 | 0.413 | -0.191 | 1.076 | 0.838 |

| New Zealand | 1.448 | 1.57 | -0.424 | 1.013 | 1.339 |

| Norway | 1.652 | 1.571 | 0.278 | 0.668 | 1.452 |

| Portugal | -0.753 | 0.866 | 0.342 | 0.828 | 0.613 |

| Singapore | 1.348 | 0.593 | 0.123 | 0.882 | 0.165 |

| Slovak Republic | 1.441 | 1.264 | 0.272 | 0.873 | 0.536 |

| Slovenia | 0.499 | 1.347 | 0.402 | 0.944 | 0.571 |

| Spain | 1.789 | 2.388 | 1.146 | 0.744 | 1.476 |

| Sweden | 1.445 | 1.477 | 0.524 | 0.897 | 1.385 |

| Switzerland | 1.525 | 1.482 | -0.282 | 1.048 | 1.13 |

| United Kingdom | 1.978 | 1.85 | -1.148 | 0.949 | 0.678 |

| United States | 1.423 | 2.327 | -0.761 | 1.045 | 0.754 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | -0.104 | -0.104 | -1.09 | 0.589 | -0.32 |

| Bulgaria | 1.219 | -0.028 | -0.54 | 0.874 | -0.06 |

| Croatia | 0.408 | 0.467 | 0.303 | 0.765 | 0.15 |

| Hungary | 1.248 | 0.764 | 0.112 | 0.758 | 0.16 |

| Montenegro | 0.166 | 0.182 | 0.561 | 0.444 | 0.376 |

| Poland | 1.035 | 0.208 | -0.64 | 0.902 | 0.364 |

| Romania | 0.558 | -0.194 | 0.232 | 0.749 | 0.117 |

| Serbia | 0.605 | 0.132 | -0.97 | -0.011 | -0.1 |

| Turkey | -1.038 | -0.498 | 0.172 | 0.586 | 0.034 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | -0.12 | 0.935 | -0.41 | 0.413 | -0.2 |

| Bhutan | -1.549 | -0.969 | 1.206 | -1.443 | -0.18 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.207 | -0.599 | -1.71 | 0.401 | 0.519 |

| Cambodia | -1.219 | -0.662 | 0.842 | -0.29 | 0.408 |

| China | -0.199 | 0.406 | -0.06 | 0.798 | 0.872 |

| India | 0.113 | -1.421 | -1.77 | -1.266 | -0.41 |

| Indonesia | -0.012 | -0.479 | 0.635 | -0.376 | -0.41 |

| Malaysia | 0 | -0.683 | 0.254 | 0.425 | 0.142 |

| Mongolia | -0.357 | -0.647 | 1.331 | -1.235 | -0.29 |

| Nepal | -0.007 | -0.658 | 0.114 | 0.044 | -0.08 |

| Philippines | -1.626 | -1.468 | 0.653 | -0.158 | -0.23 |

| Sri Lanka | -0.585 | -0.918 | 1.414 | -0.624 | -1.12 |

| Thailand | -0.433 | -1.995 | 0.011 | -0.271 | 0.3 |

| Timor-Leste | -0.617 | -2.079 | 1.247 | -1.105 | -0.27 |

| Viet Nam | 0.238 | -0.878 | 1.082 | -0.176 | 0.212 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | -0.457 | -0.408 | -0.29 | 0.485 | -0.36 |

| Bahrain | -0.321 | -0.196 | -2.97 | 0.442 | 0.801 |

| Egypt | -0.273 | -1.246 | -1.21 | 0.678 | 0.048 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | -0.625 | -0.688 | -1.64 | 0.674 | -0.88 |

| Jordan | -0.38 | 0.016 | -0.56 | 0.771 | 0.609 |

| Kuwait | -1.008 | -0.399 | -2.45 | 0.637 | 0.373 |

| Mauritania | -0.071 | 0.037 | -0.24 | -0.157 | 0.361 |

| Morocco | -0.462 | -0.278 | -1.79 | -0.017 | 1.053 |

| Oman | -0.705 | -0.515 | -3.21 | 0.399 | 1.348 |

| Pakistan | -0.422 | -0.894 | -1.92 | 0.334 | 0.782 |

| Qatar | -0.554 | -0.285 | -0.33 | 0.519 | 0.427 |

| Saudi Arabia | -0.285 | 0.459 | -1.91 | 0.371 | 1.085 |

| Tunisia | -1.956 | -1.255 | -0.12 | -0.641 | -0.18 |

| United Arab Emirates | -0.983 | -0.714 | 0.317 | -1.142 | -0.57 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | -0.398 | 0.15 | -0.08 | 0.624 | -0.57 |

| Bolivia | -0.446 | -0.423 | 0.506 | -0.309 | -0.88 |

| Brazil | -1.021 | 0.466 | 1.11 | 0.273 | -1.42 |

| Chile | 0.138 | -0.071 | 0.099 | 0.709 | 0.742 |

| Colombia | -0.992 | -0.29 | 1.143 | 0.118 | -1.81 |

| Costa Rica | -0.594 | -0.117 | 1.23 | 0.598 | -0.14 |

| Dominican Republic | -0.747 | 0.052 | 0.74 | 0.209 | -1.23 |

| Ecuador | -1.41 | -0.313 | 0.654 | -0.077 | -1.01 |

| El Salvador | -1.702 | -0.98 | 0.696 | 0.04 | -3.87 |

| Guatemala | -0.788 | -1.056 | 0.922 | -0.63 | -2.18 |

| Honduras | -1.761 | -0.514 | 0.795 | -0.309 | -3.72 |

| Jamaica | -0.051 | 0.302 | 0.199 | 0.168 | -2.58 |

| Mexico | -1.136 | -0.315 | 0.188 | 0.18 | -1.02 |

| Nicaragua | -0.054 | -0.708 | 0.731 | -1.003 | -0.62 |

| Panama | -0.143 | -0.498 | 1.068 | 0.179 | -0.39 |

| Paraguay | -1.293 | -0.389 | 1.285 | -0.259 | -0.85 |

| Peru | -0.382 | -0.649 | 1.087 | -0.482 | -0.33 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.139 | -0.227 | -1.86 | 0.249 | -1.46 |

| Uruguay | -0.898 | -0.002 | 0.498 | 0.296 | 0.33 |

| Venezuela | -0.261 | -0.078 | 0.144 | 0.121 | -3.5 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | -0.609 | -0.87 | 0.584 | -1.331 | -0.47 |

| Botswana | -0.191 | -0.23 | 0.468 | -0.654 | 0.224 |

| Burkina Faso | -1.011 | -1.117 | 0.947 | -2.03 | -0.57 |

| Burundi | -1.319 | -1.185 | 0.907 | -1.215 | -0.61 |

| Cameroon | -0.983 | -1.276 | 1.088 | -1.652 | -0.16 |

| Chad | -1.384 | -1.31 | 0.86 | -3.112 | -0.87 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | -0.894 | -0.557 | 0.678 | -1.786 | -0.66 |

| Ethiopia | -1.129 | -1.371 | 0.886 | -3.249 | -0.14 |

| Ghana | -0.357 | -0.784 | 0.963 | -1.154 | 0.044 |

| Kenya | -0.729 | -0.77 | 0.608 | -1.77 | -0.18 |

| Lesotho | -0.729 | -0.403 | -0.83 | -1.083 | -1.51 |

| Madagascar | -0.846 | -0.949 | 1.009 | -2.503 | -0.52 |

| Malawi | -0.701 | -0.714 | 1.09 | -1.379 | -0.17 |

| Mali | -2.046 | -0.919 | 0.726 | -0.911 | -0.4 |

| Mauritius | 0.148 | -0.099 | 0.313 | 0.69 | 0.703 |

| Mozambique | -1.435 | -0.832 | 1.17 | -2.608 | -0.36 |

| Namibia | -0.055 | -0.293 | 0.296 | -0.5 | -0.01 |

| Nigeria | -0.959 | -1.155 | 0.82 | -2.009 | -0.63 |

| Senegal | -1.302 | -0.718 | 0.766 | -0.638 | -0.12 |

| South Africa | -0.483 | 0.13 | -2.07 | 0.311 | -1.23 |

| Tanzania | -0.989 | -0.914 | 1.438 | -2.44 | -0.19 |

| Uganda | -1.243 | -1.186 | 0.935 | -2.751 | -0.59 |

| Zambia | -0.615 | -0.582 | 1.56 | -1.546 | 0.107 |

| Zimbabwe | -0.833 | -0.619 | 0.159 | -0.831 | -0.35 |

| Countries | People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 0.833 | -0.607 | 0.223 | 0.626 | 0.185 |

| Azerbaijan | 1.826 | -0.309 | 0.024 | 0.35 | 0.337 |

| Georgia | 0.694 | -0.29 | 0.641 | 0.432 | 0.192 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.631 | -0.266 | -2.608 | 0.549 | -0.019 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | -0.048 | -0.868 | -0.601 | -0.072 | -0.475 |

| Moldova | 1.312 | -0.281 | -0.536 | 0.079 | -0.91 |

| Russian Federation | 0.645 | 0.373 | -1.182 | 0.632 | -0.675 |

| Tajikistan | 0.063 | -1.495 | 0.321 | -0.749 | -0.14 |

| Ukraine | 0.559 | -0.151 | -1.536 | 0.625 | -0.495 |

| Top 25 Countries’ H&LS |

Top 25 Countries’ Pillars Avg |

Bottom 25 Countries H&LS |

Bottom 25 Countries Pillars Avg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia | Cyprus | Ecuador | Chad |

| France | Finland | Saudi Arabia | El Salvador |

| Ukraine | Singapore | Benin | Honduras |

| Hungary | Germany | Belgium | Ethiopia |

| Azerbaijan | Korea, Rep. | Tunisia | Uganda |

| Brazil | Malta | Czech Republic | India |

| Australia | Slovenia | Venezuela | Lesotho |

| Egypt | Japan | Paraguay | Tunisia |

| Nicaragua | Canada | Bolivia | Mozambique |

| Netherlands | Luxembourg | Slovenia | Nigeria |

| Algeria | Lithuania | Luxembourg | Madagascar |

| Malta | United Kingdom | Bahrain | Burkina Faso |

| Croatia | Czech Republic | Dominican Republic | Guatemala |

| United Kingdom | Slovak Republic | Indonesia | Venezuela |

| Qatar | Estonia | Jamaica | Mali |

| Tanzania | United States | Mozambique | Burundi |

| Cameroon | Switzerland | Timor-Leste | South Africa |

| Sweden | New Zealand | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Switzerland | Ireland | Burkina Faso | Iran, Islamic Rep. |

| Malawi | Denmark | Italy | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Uganda | Israel | Zimbabwe | Tanzania |

| Guatemala | Norway | China | United Arab Emirates |

| Philippines | Sweden | Colombia | Cameroon |

| Sri Lanka | Greece | Mexico | Bhutan |

| Tajikistan | Iceland | Germany | Kuwait |

References

- Perry, K.K. Innovation, institutions and development: a critical review and grounded heterodox economic analysis of late-industrialising contexts. Camb. J. Econ. 2020, 44, 391–415, . [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2002). Competition and competitiveness in a new economy. Competition and Competitiveness in A New Economy, 11-26.

- Zizek, S. (2006). The Parallax View. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- van Vuuren, D.P.; Zimm, C.; Busch, S.; Kriegler, E.; Leininger, J.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockstrom, J.; Riahi, K.; Sperling, F.; et al. Defining a sustainable development target space for 2030 and 2050. One Earth 2022, 5, 142–156, . [CrossRef]

- Pianta, S.; Brutschin, E. Emissions Lock-in, Capacity, and Public Opinion: How Insights From Political Science Can Inform Climate Modeling Efforts. Politi- Gov. 2022, 10, 186–199, . [CrossRef]

- Rosile, G.A.; Boje, D.M.; Carlon, D.M.; Downs, A.; Saylors, R. Storytelling Diamond. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 557–580, . [CrossRef]

- Gore, C. The Rise and Fall of the Washington Consensus as a Paradigm for Developing Countries. World Dev. 2000, 28, 789–804, . [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2018). What do trade agreements really do? Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 32 (2), Spring 2018, Pages 73–90.

- Arrighi, G., & Zhang, L. (2011). Beyond the Washington consensus: a new Bandung? Globalization and beyond: New Examinations of Global Power and Its Alternatives, 25-57.

- Ravetz, J.R. Post-Normal Science and the complexity of transitions towards sustainability. Ecol. Complex. 2006, 3, 275–284, . [CrossRef]

- Peneder, M. Competitiveness and industrial policy: from rationalities of failure towards the ability to evolve. Camb. J. Econ. 2017, 41, 829–858, . [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Abraham, E.; Aggarwal, S.; Khan, M.A.; Arguello, R.; Babbar-Sebens, M.; Bereslawski, J.L.; Bielicki, J.M.; Campana, P.E.; Carrazzone, M.E.S.; et al. Emerging Themes and Future Directions of Multi-Sector Nexus Research and Implementation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Wiederkehr, C.; Dimitrova, A.; Hermans, K. Agricultural livelihoods, adaptation, and environmental migration in sub-Saharan drylands: a meta-analytical review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 083003, . [CrossRef]

- Brutschin, E.; Andrijevic, M. Why Ambitious and Just Climate Mitigation Needs Political Science. Politi- Gov. 2022, 10, 167–170, . [CrossRef]

- Koehler, G., Kühner, S., & Neff, D. (2021). Social policy development and its obstacles: an analysis of the South Asian welfare geography during and after the social turn. In Handbook of Development Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- West, W., Jamila Haider,L., Stålhammar, S., & Woroniecki, S. (2020) A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations, Ecosystems and People, 16:1, 304-325.

- Ellis, B.J.; Figueredo, A.J.; Brumbach, B.H.; Schlomer, G.L. Fundamental Dimensions of Environmental Risk. Hum. Nat. 2009, 20, 204–268, . [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (1992). One more turn after the social turn: Easing science studies into the non-modern world. The Social Dimensions of Science, 292, 272-94.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Sato, R. The Harrod-Domar Model vs the Neo-Classical Growth Model. Econ. J. 1964, 74, 380, . [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. Perspectives on Growth Theory. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 45–54, . [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R. (2009) "The Co-Evolution of the Washington Consensus and the Economic Development Discourse," Macalester International: Vol. 24, Article 8. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol24/iss1/8.

- Acemoglu, D., Gallego, F. A., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Institutions, human capital, and development. Annu. Rev. Econ., 6(1), 875-912.

- Street, J.H. The Institutionalist Theory of Economic Development. J. Econ. Issues 1987, 21, 1861–1887, . [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.A. Challenging Institutional Theory’s Critical Credentials. Organ. Theory 2020, 1, . [CrossRef]

- Lebaron, F. (2003). Pierre Bourdieu: economic models against economicism. Theory and Society, 32(5/6): 551-565.

- Syll, L. (2018). The main reason why almost all econometric models are wrong. World Economics Association Commentaries, 8(3). June 2018. https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/newsletterarticles/econometric-models-wrong/ (accessed in June 2022).

- Mardani, A.; Kannan, D.; Hooker, R.E.; Ozkul, S.; Alrasheedi, M.; Tirkolaee, E.B. Evaluation of green and sustainable supply chain management using structural equation modelling: A systematic review of the state of the art literature and recommendations for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119383, . [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Streimikiene, D.; Jusoh, A.; Khoshnoudi, M. A comprehensive review of data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach in energy efficiency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1298–1322, . [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G. & Hynes, W. (2019). Beyond growth: Towards a new economic approach. OECD, General Secretariat. https://www.oecd.org/naec/averting-systemic-collapse/SG-NAEC(2019)3_Beyond%20Growth.pdf (accessed in September 2022).

- Ghag, N.; Acharya, P.; Khanapuri, V. Prioritizing the Challenges Faced in Achieving International Competitiveness by Export-Oriented Indian SMEs: a DEMATEL Approach. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Competitiveness 2022, 17, 12–24, . [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J.; Paliwoda-Pękosz, G. ICT for Global Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: Economic, Cultural, and Social Innovations for Human Capital in Transition Economies. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2017, 34, 304–307, . [CrossRef]

- Wojewódzka-Wiewiórska, A.; Kłoczko-Gajewska, A.; Sulewski, P. Between the Social and Economic Dimensions of Sustainability in Rural Areas—In Search of Farmers’ Quality of Life. Sustainability 2019, 12, 148, . [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, A. (2008). How many dimensions does sustainable development have? Sustainable Development, 16(2), 81-90.

- Alam, M. S., & Kabir, N. (2013). Economic growth and environmental sustainability: empirical evidence from East and South-East Asia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 5(2).

- Cebula, R. J. (2013). Which economic freedoms influence per capita real income? Applied Economics Letters, 20(4), 368-372.

- Ekins, P. (2002). Economic growth and environmental sustainability: the prospects for green growth. Routledge.

- Chai, J.; Hao, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y. Do constraints created by economic growth targets benefit sustainable development? Evidence from China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 4188–4205, . [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814, . [CrossRef]

- Albright, A.; Bundy, D.A.P. The Global Partnership for Education: forging a stronger partnership between health and education sectors to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal. 2018, 2, 473–474, . [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi M.A. & O. Oladele. (2005). Public Education Expenditure and Defense Spending in Nigeria: An Empirical Investigation. http//www.saga. cornell. educ /saga/educconf/adebiyi.pdf (accessed February 10, 2010).

- Bende-Nabende, A. (2017). Globalisation, FDI, regional integration and sustainable development: theory, evidence, and policy. Routledge.

- Bečić, E.; Mulej, E.M.; Švarc, J. Measuring Social Progress by Sustainable Development Indicators: Cases of Croatia and Slovenia. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 458–465, . [CrossRef]

- de Angelis, E.M.; Di Giacomo, M.; Vannoni, D. Climate Change and Economic Growth: The Role of Environmental Policy Stringency. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2273, . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J. Global Sustainable Development Governance: Institutional Challenges from a Theoretical Perspective. Int. Environ. Agreements: Politi- Law Econ. 2002, 2, 361–388, . [CrossRef]

- Declaration, M. (2000, May). Malmö Ministerial Declaration, adopted by the Global Ministerial Environment Forum—Sixth Special Session of the Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme. In Fifth Plenary Meeting (Vol. 31).

- Frey, B.S.; Luechinger, S.; Stutzer, A. The Life Satisfaction Approach to Environmental Valuation. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2010, 2, 139–160, . [CrossRef]

- Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser (2013) - "Happiness and Life Satisfaction". Published online at Our World in Data.org. https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction (accessed in August 2022).

- Duffy, B. (2018). The perils of perception: Why we’re wrong about nearly everything. Atlantic Books.

- Petrunyk, I.; Pfeifer, C. Life Satisfaction in Germany After Reunification: Additional Insights on the Pattern of Convergence. 2016, 236, 217–239, . [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Happiness inequality in the United States. The Journal of Legal Studies, 37(S2), S33-S79.

- Diener, E., & Diener, M. (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. In Culture and Well-Being (pp. 71-91). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Clark, A.E.; Flèche, S.; Senik, C. Economic Growth Evens Out Happiness: Evidence from Six Surveys. Rev. Income Wealth 2015, 62, 405–419, . [CrossRef]

- Fosfuri, A.; Motta, M.; Rønde, T. Foreign direct investment and spillovers through workers’ mobility. J. Int. Econ. 2001, 53, 205–222, . [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., & Mehboob, F. (2014). Impact of FDI on GDP: An analysis of global economy on production function.

- Fernandez, M.; Alnuaimi, A.A.A.A.; Joseph, R. FDI Environment in China: A Critical Analysis. Int. J. Financial Res. 2020, 11, 238, . [CrossRef]

- Anh, N. T. N., & Huong, M. N. L. (2019). Impacts of Foreign Direct Investment on Vietnam’s Economy in a Relation to Natural Environment. Socio-Economic And Environmental Issues in Development, 977.

- Kumar, N. (1998). Globalization, Foreign Direct Investment and Technology Transfers. Taylor & Francis.

- Cooper, R.N.; Moran, T.H. Foreign Direct Investment and Development: The New Policy Agenda for Developing Countries and Economies in Transition. Foreign Aff. 1999, 78, 166, . [CrossRef]

- Glass, A.J.; Saggi, K. Multinational Firms and Technology Transfer. Scand. J. Econ. 2002, 104, 495–513, . [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanyam, V. N., Salisu, M., & Sapsford, D. (1996). Foreign direct investment and growth in E.P. and I.S. countries. The Economic Journal, 106(434), 92-105.

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115-135.

- Alguacil, M.; Cuadros, A.; Orts, V. Foreign direct investment, exports and domestic performance in Mexico: a causality analysis. Econ. Lett. 2002, 77, 371–376, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Burridge, P., & Sinclair, P. J. (2002). Relationships between economic growth, foreign direct investment, and trade: evidence from China. Applied Economics, 34(11), 1433-1440.

- Delevic, U., & Heim, I. (2017). Institutions in transition: is the E.U. integration process relevant for inward FDI in transition European economies? Eurasian Journal of Economics and Finance, 5(1), 16-32.

- Kok, R.; Ersoy, B.A. Analyses of FDI determinants in developing countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2009, 36, 105–123, . [CrossRef]

- Akkemik, K. A. (2008). Industrial Development in East Asia: A Comparative Look at Japan, Korea, Taiwan, And Singapore (With Cd-rom). World Scientific, (Vol. 3).

- Görg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2004). Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? The World Bank Research Observer, 19(2), 171-197.

- Wooster, R.B.; Diebel, D.S. Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2010, 14, 640–655, . [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, S.M. Foreign direct investment and technology spillovers: Evidence from panel data analysis of manufacturing firms in Zambia. J. Dev. Econ. 2006, 81, 514–526, . [CrossRef]

- Gorg, H., & Strobl, E. (2001). Multinational companies and productivity spillovers: A meta-analysis. The Economic Journal, 111(475), F723-F739.

- Javorcik, B. S., & Spatareanu, M. (2008). To share or not to share: Does local participation matter for spillovers from foreign direct investment? Journal of Development Economics, 85(1-2), 194-217.

- Kugler, M. (2006). Spillovers from foreign direct investment: within or between industries? Journal of Development Economics, 80(2), 444-477.

- Sjöholm, F. Productivity Growth in Indonesia: The Role of Regional Characteristics and Direct Foreign Investment. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1999, 47, 559–584, . [CrossRef]

- Smeets, R. Collecting the Pieces of the FDI Knowledge Spillovers Puzzle. World Bank Res. Obs. 2008, 23, 107–138, . [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sheng, Y. Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: Firm-Level Evidence from China. World Dev. 2012, 40, 62–74, . [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. In The International Allocation of Economic Activity (pp. 395-418). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Dunning, J.H. Globalization and the new geography of foreign direct investment. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 1998, 26, 47–69, . [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.P. The evolution of Indian Outward Foreign Direct Investment: changing trends and patterns. Int. J. Technol. Glob. 2008, 4, 70, . [CrossRef]

- Sauvant, K.P. China: Inward and Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2011, 3, 1–4, . [CrossRef]

- Sauvant, K. P., Mallampally, P., McAllister, G., Xian, G., Bellak, C., Mayer, S., ... & Garcia, D. (2013). Inward and outward FDI country profiles.

- Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. (1976). A long-run theory of multinational enterprise. In The Future of the Multinational Enterprise (pp. 32-65). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Irandoust, J. E. M. (2001). On the causality between foreign direct investment and output: a comparative study. The International Trade Journal, 15(1), 1-26.

- de Vita, G.; Kyaw, K.S. Growth effects of FDI and portfolio investment flows to developing countries: a disaggregated analysis by income levels. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2009, 16, 277–283, . [CrossRef]

- Lensink, R., & Morrissey, O. (2006). Foreign direct investment: Flows, volatility, and the impact on growth. Review of International Economics, 14(3), 478-493.

- Al-Sadiq, M. A. J. (2013). Outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: The case of developing countries. International Monetary Fund.

- Carkovic, M., & Levine, R. (2005). Does foreign direct investment accelerate economic growth. Does foreign direct investment promote development, 195, 220.

- Blomström, M., Kokko, A., & Mucchielli, J. L. (2003). The economics of foreign direct investment incentives. In Foreign Direct Investment in The Real and Financial Sector of Industrial Countries (pp. 37-60). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Wei, S. J. (1995). The open-door policy and China’s rapid growth: Evidence from city-level data. In Growth theories in light of the East Asian experience, 4, 73-104.

- Dees, S. Foreign Direct Investment in China: Determinants and Effects. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 1998, 31, 175–194, . [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.T. (1983) Third World Multinationals: The Rise of Foreign Investments from Developing Countries, Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Buckley, P.J.; Clegg, J.; Wang, C. The Impact of Inward FDI on the Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 637–655, . [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B.S. Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 605–627, . [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N. Examining the Long Run Effects of Export, Import and FDI Inflows on the FDI Outflows from India: A Causality Analysis. 2009, 10, 65–88, . [CrossRef]

- Gorynia, M., Nowak, J., & Wolniak, R. (2008). Poland’s investment development path and industry structure of FDI inflows and outflows. Journal of East-West Business, 14(2), 189-212.

- Alfaro, L.; Chanda, A.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Sayek, S. Does foreign direct investment promote growth? Exploring the role of financial markets on linkages. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 91, 242–256, . [CrossRef]

- Vasa, L.; Angeloska, A. Foreign direct investment in the Republic of Serbia: Correlation between foreign direct investments and the selected economic variables. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 13, 170–183, . [CrossRef]

- Markusen, J.R.; Venables, A.J. Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1999, 43, 335–356, . [CrossRef]

- Lin, P., Liu, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2009). Do Chinese domestic firms benefit from FDI inflow? Evidence of horizontal and vertical spillovers. China Economic Review, 20(4), 677-691.

- Marcin, K. How does FDI inflow affect productivity of domestic firms? The role of horizontal and vertical spillovers, absorptive capacity and competition. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2008, 17, 155–173, . [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Clare, A. (1996). Multinationals, linkages, and economic development. The American Economic Review, 852-873.

- World Bank database (2019). https://databank.worldbank.org/source/sustainable-development-goals-(sdgs) (accessed on January 2021).

- Selim, S. Life Satisfaction and Happiness in Turkey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 88, 531–562, . [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2019). Changing world happiness. World Happiness Report, 2019, 11-46.

- The Heritage Foundation. (2021a). Business Freedom. Business Freedom Index: Regulations on Starting & Operating a Business, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/index/business-freedom (accessed in February 2021).

- The Heritage Foundation. (2021b). The 12 economic freedoms: Policies for lasting progress and prosperity. Business Freedom Index: Regulations on Starting & Operating a Business.

- World Economic Forum. (2018). Introduction. Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018, http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-index-2017-2018/introduction/ accessed February 2022).

- Dima, A.M.; Begu, L.; Vasilescu, M.D.; Maassen, M.A. The Relationship between the Knowledge Economy and Global Competitiveness in the European Union. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1706, . [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.P.; Moesen, W. Composite competitiveness indicators with endogenous versus predetermined weights. Competitiveness Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2011, 21, 129–151, . [CrossRef]

- Bucher, S. The Global Competitiveness Index As an Indicator of Sustainable Development. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2018, 88, 44–57, . [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2010). Mismeasuring our lives: Why GDP doesn’t add up. The New Press.

- World Economic Forum. (2019) Global Competitiveness Report 2019: How to End a Lost Decade of Productivity Growth?

- World Bank Group. (2019). Bhutan Development Report, January 2019: A Path to Inclusive and Sustainable Development. World Bank.

- McLeod, S. (2020). What does a box plot tell you? Simply psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/boxplots.html on November 2022.

- Kock, N. (2017). Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In Partial least squares path modeling (pp. 245-257). Springer, Cham.

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJEC), 11(4), 1-10.

- Tenenhaus, M., Amato, S., & Esposito Vinzi, V. (2004, June). A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling. In Proceedings of the XLII SIS scientific meeting (Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 739-742).

- Hayes, T. R-squared change in structural equation models with latent variables and missing data. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 2127–2157, . [CrossRef]

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions?. Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031, . [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, T.O.; Chan, D.W. A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 231–250, . [CrossRef]

- Kinda, S. (2011). Democratic institutions and environmental quality: effects and transmission channels. Available at SSRN 2714300.

- Kulin, J.; Sevä, I.J. The Role of Government in Protecting the Environment: Quality of Government and the Translation of Normative Views about Government Responsibility into Spending Preferences. Int. J. Sociol. 2019, 49, 110–129, . [CrossRef]

- Stringham, E. P., & Levendis, J. (2010). The relationship between economic freedom and homicide. Economic Freedom of the World: 2010 Annual Report, 203-217.

- Hockett, R. (2014). The Macroprudential Turn: From Institutional Safety and Soundness to Systematic Financial Stability in Financial Supervision. Va. L. & Bus. Rev., 9, 201.

- Ferrara, A.R.; Nisticò, R. Does Institutional Quality Matter for Multidimensional Well-Being Inequalities? Insights from Italy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 1063–1105, . [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Mutascu, M. The relationship between environmental degradation and happiness in 23 developed contemporary economies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2015, 26, 301–321, . [CrossRef]

- Collins, M., Knutti, R., Arblaster, J., Dufresne, J. L., Fichefet, T., Friedlingstein, P., ... & Booth, B. B. (2013). Long-term climate change: projections, commitments, and irreversibility. In Climate change 2013-The physical science basis: Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1029-1136). Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, J. (2017). Addressing the Completion Challenge in Portuguese Higher Education. M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series, 8.

- Dawson, R. F., Kearney, M. S., & Sullivan, J. X. (2020). Comprehensive approaches to increasing student completion in higher education: A survey of the landscape (No. w28046). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Arvin, B. M., Barillas, F., & Lew, B. (2002). Is democracy a component of donors’ foreign aid policies. New Perspectives on Foreign Aid and Economic Development, 171-198.

- Branden, J.B. and Bromley, D. (1981), ‘The economics of cooperation over collective bads’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp.134–150.

- Khan, S.A.R.; Sharif, A.; Golpîra, H.; Kumar, A. A green ideology in Asian emerging economies: From environmental policy and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 1063–1075, . [CrossRef]

- Islam, R. (2017). The Role of Macro-Economic Variables for Determining Happiness: The Empirical Evidence from South Asian Region.

- Childs, A.; Tenzin, W.; Johnson, D.; Ramachandran, K. Science Education in Bhutan: Issues and challenges. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 375–400, . [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, C.; Yadav, R.K.; Timilshina, P.; Ojha, R.; Gaire, D.; Ghimire, A. Proportion and factors affecting for post-natal care utilization in developing countries: A systematic review. J. Manmohan Mem. Inst. Heal. Sci. 2016, 2, 14–19, . [CrossRef]

- Tobgay, T.; Dophu, U.; Torres, C.; Bangchang, N. Health and Gross National Happiness: review of current status in Bhutan. J. Multidiscip. Heal. 2011, 4, 293–298, . [CrossRef]

- Weiffen, B. The Cultural-Economic Syndrome: Impediments to Democracy in the Middle East. Comp. Sociol. 2004, 3, 353–375, . [CrossRef]

- Ramzi, S.; Afonso, A.; Ayadi, M. Assessment of efficiency in basic and secondary education in Tunisia: A regional analysis. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2016, 51, 62–76, . [CrossRef]

- Gaaloul, N. Water resources and management in Tunisia. Int. J. Water 2011, 6, 92, . [CrossRef]

- Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2009). Does inequality matter to individual welfare? An initial exploration based on happiness surveys from Latin America. In Happiness, Economics and Politics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wolff, L., Schiefelbein, E., & Schiefelbein, P. (2002). ͞Primary education in Latin America. The unfinished agenda. Technical Paper Series Nº EDU-120. Washington, DC: Interamerican Development Bank.

- Psacharopoulos, G.; Ng, Y.C. Earnings and Education in Latin America. Educ. Econ. 1994, 2, 187–207, . [CrossRef]

- A Montenegro, R.; Stephens, C. Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet 2006, 367, 1859–1869, . [CrossRef]

- Mascayano, F.; Irrazabal, M.; Emilia, W.D.; Vaner, S.J.; Sapag, J.C.; Alvarado, R.; Yang, L.H.; Sinah, B. Suicide in Latin America: a growing public health issue.. 2015, 72, 295–303.

- Briceño-León, R. Urban violence and public health in Latin America: a sociological explanatory framework. 2005, 21, 1629–1648, . [CrossRef]

- Shelley, T. (2005). Oil: Politics, poverty, and the planet. Zed Books.

- Kravdal, . Education and fertility in sub-Saharan africa: Individual and community effects. Demography 2002, 39, 233–250, . [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Income, Health, and Well-Being around the World: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 53–72, . [CrossRef]

- Amavilah, V.; Asongu, S.A.; Andrés, A.R. Effects of globalization on peace and stability: Implications for governance and the knowledge economy of African countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 122, 91–103, . [CrossRef]

- Millennium ecosystem assessment, M. E. A. (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being (Vol. 5, pp. 563-563). Washington, DC: Island press.

- Matlosa, K. Pondering the culture of violence in Lesotho: a case for demilitarisation. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2020, 38, 381–398, . [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, O. Hydropolitics, Ecocide and Human Security in Lesotho: A Case Study of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project *. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2007, 33, 3–17, . [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, G. D. T. (1996). South Africa’s water resources and the Lesotho highlands water scheme: a partial solution to the country’s water problems. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 12(1), 65-78.

- Letcher, T. M. (2021). Global warmingda complex situation. Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth, 2.

- Aumeerally, N., Chen-Carrel, A., & Coleman, P. T. (2022). Learning with Peaceful, Heterogeneous Communities: Lessons on Sustaining Peace in Mauritius. Peace and Conflict Studies, 28(2), 3.

- Baker, M. (2013). Poverty, Social Assistance, and the Employability of Mothers in Four Commonwealth Countries. In Women’s Work is Never Done (pp. 87-112). Routledge.

- M’Cormack-Hale, F. A., & M’Cormack-Hale, F. A. O. (2012). Gender, peace, and security: women’s advocacy and conflict resolution. Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Lu, W.; Kasimov, I.; Karimov, I.; Abdullaev, Y. Foreign Direct Investment, Natural Resources, Economic Freedom, and Sea-Access: Evidence from the Commonwealth of Independent States. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3135, . [CrossRef]

| “Social-turn 1” models | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| 0.379 | 0.367 | 0.325 | 0.430 | 0.321 | 0.373 | |

| “Social-turn 2” models | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 8 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 |

| 0.569 | 0.551 | 0.519 | 0.497 | 0.399 | 0.387 |

| People | Prosperity | Planet | Resources | Peace | Financial Enhancers | InstitutionalEnhancers | GC-Ins | GC-InnS | FDIIn-flow | FDIOut-flow | H&LS | |

| People | (0.651) | |||||||||||

| Prosperity | 0.588 | (0.542) | ||||||||||

| Planet | 0.220 | 0.181 | (0.623) | |||||||||

| Resources | 0.523 | 0.627 | 0.437 | (0.808) | ||||||||

| Peace | 0.423 | 0.468 | 0.244 | 0.362 | (0.802) | |||||||

| Financial Enhancers | 0.501 | 0.668 | 0.111 | 0.509 | 0.451 | (0.774) | ||||||

| Institutional Enhancers | 0.547 | 0.763 | 0.236 | 0.611 | 0.628 | 0.760 | (0.818) | |||||

| GC-Ins | 0.462 | 0.602 | 0.269 | 0.534 | 0.600 | 0.626 | 0.814 | (0.889) | ||||

| GC-InnS | 0.475 | 0.702 | 0.240 | 0.562 | 0.574 | 0.575 | 0.798 | 0.890 | (0.980) | |||

| FDI In-flow | 0.203 | 0.198 | 0.135 | 0.224 | 0.225 | 0.242 | 0.296 | 0.313 | 0.316 | (0.770) | ||

| FDI Out-flow | 0.243 | 0.279 | 0.133 | 0.227 | 0.247 | 0.265 | 0.358 | 0.333 | 0.388 | 0.823 | (0.783) | |

| H&LS | 0.291 | 0.405 | 0.010 | 0.376 | 0.194 | 0.369 | 0.392 | 0.343 | 0.382 | 0.147 | 0.178 | (1.000) |

| Relationships | Advanced Economies |

Emerging & Developing Europe |

Emerging & Developing Asia |

Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan | Latin America & the Caribbean | Sub Saharan Africa |

Commonwealth |

| Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

|

| Institutional Enhancers → FDII (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.097* | n.s. | -0.212** | n.s. | 0.370*** | 0.130* | n.s. |

| Institutional Enhancers → FDII (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.067* | 0.248** | -0.212** | n.s | 0.370*** | n.s | n.s |

| Institutional Enhancers → FDIO (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.094* | 0.211* | 0.354*** | 0.457*** | 0.433*** | 0.251*** | n.s. |

| Institutional Enhancers → FDIO (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.094* | n.s | 0.354*** | 0.457*** | 0.433*** | 0.251*** | n.s |

| Financial Enhancers → FDII (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.103* | n.s. | 0.141* | 0.142* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Financial Enhancers → FDII (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.103* | n.s | 0.141* | 0.142* | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| Financial Enhancers → FDIO (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | -0.204*** | -0.103* | -0.287** |

| Financial Enhancers → FDIO (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | -0.13* | -0.287** |

| FDII → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.264*** | 0.746*** | n.s. | n.s. | 0.444*** | n.s. | 0.246** |

| FDII → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.154** | 0.669*** | n.s | 0.158** | 0.318*** | n.s | n.s |

| FDII → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

-0.169*** | 0.248** | n.s. | n.s. | 0.480*** | 0.118* | n.s. |

| FDII → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.209*** | 0.264** | n.s | 0.141* | 0.379*** | 0.109* | -0.216* |

| FDII → FDIO (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.819*** | 0.980*** | 0.403*** | n.s. | 0.500*** | 0.192*** | 0.573*** |

| FDII → FDIO (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.819*** | 0.939*** | 0.403*** | n.s. | 0.500*** | 0.192*** | 0.573*** |

| Relationships | Advanced Economies |

Emerging & Developing Europe |

Emerging & Developing Asia |

Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan | Latin America & the Caribbean | Sub Saharan Africa |

Commonwealth |

| Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

|

| FDIO → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | -0.551*** | 0.159* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| FDIO → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.085* | -0.444*** | 0.546*** | 0.395*** | 0.146* | 0.127* | n.s |

| FDIO → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.380*** | n.s. | 0.227** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.338*** |

| FDIO → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.438*** | n.s | 0.576*** | 0.383*** | 0.186** | 0.239*** | 0.500*** |

| People → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.143** 0.147 / 0.055^ |

n.s. | n.s. | 0.216** 0.225 / 0.096^ |

0.032* 0.115 / 0.031^ |

0.278*** 0.268 / 0.126^ |

n.s. |

| People → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.315*** 0.326 / 0.152^^ |

n.s. | 0.228*** 0.209 / 0.098^ |

0.287*** 0.502 / 0.105^ |

| People → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.172*** 0.190 / 0.038^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.130*** 0.220 / 0.024^ |

n.s. |

| Prosperity → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.390*** 0.398 / 0.280^^ |

0.308*** 0.303 / 0.088^ |

0.211*** 0.235 / 0.087^ |

0.416*** 0.428 / 0.228^^ |

n.s. | 0.394*** 0.427 / 0.231^^ |

n.s. |

| Prosperity → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.596*** 0.608 / 0.424^^^ |

0.202* 0.096 / 0.041^ |

0.146* 0.117 / 0.055^ |

0.411*** 0.427 / 0.205^^ |

n.s. | 0.398*** 0.439 / 0.234^^ |

n.s. |

| Prosperity → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.096** 0.156 / 0.026^ |

n.s. | 0.331*** 0.388 / 0.142^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.498*** 0.575 / 0.331^^ |

| Planet → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | 0.241** 0.238 / 0.075^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.321*** 0.268 / 0.090^ |

n.s. |

| Planet → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.169* 0.173 / 0.076^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Planet → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.446*** 0.472 / 0.197^^ |

n.s. | n.s. |

| Resources → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | 0.361*** 0.365 / 0.109^ |

0.529*** 0.539 / 0.380^^^ |

n.s. | 0.407*** 0.458 / 0.150^^ |

0.364*** 0.359 / 0.195^^ |

0.440*** 0.431 / 0.165^^ |

| Resources → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | 0.632*** 0.642 / 0.374^^^ |

0.464*** 0.484 / 0.330^^ |

n.s. | 0.599*** 0.635 / 0.357^^^ |

0.183*** 0.187 / 0.085^ |

0.241* 0.195 / 0.076^ |

| Resources → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.167** 0.141 / 0.029^ |

0.122* 0.164 / 0.026^ |

0.151*** 0.263 / 0.071^ |

n.s. | 0.204*** 0.280 / 0.051^^ |

n.s. | n.s. |

| Peace → GC-Ins (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.528*** 0.549 / 0.349^^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.181* 0.115 / 0.033^ |

0.041** 0.156 /0.025^ |

0.381*** 0.378 / 0.150^^ |

| Peace → GC-InnS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.173*** 0.205 / 0.112^ |

n.s. | 0.144* 0.130 / 0.050^ |

0.012* 0.176 / 0.083^ |

0.105* 0.122 / 0.044^ |

0.165*** 0.295 / 0.031^ |

0.295** 0.289 / 0.045^ |

| Peace → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.103* 0.175 / 0.042^ |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.183*** 0.254 / 0.027^ |

n.s. |

| GC-Ins → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

0.124** | -0.354*** | 0.406*** | n.s. | -0.531*** | n.s. | n.s. |

| GC-InnS → H&LS (“Social-turn 2”) |

n.s. | 0.646*** | -0.221** | -0.314*** | 0.493*** | 0.435*** | -0.276** |

| Institutional Enhancers → People (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.113* -0.099 / 0.026^ |

0.392*** 0.366 / 0.088^ |

0.137* 0.169 / 0.042^ |

0.753*** 0.740 / 0.388^^^ |

0.618*** 0.647 / 0.310^^ |

0.562*** 0.588 / 0.313^^ |

n.s |

| Institutional Enhancers → Prosperity (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.148** 0.178 / 0.116^ |

0.548*** 0.540 / 0.292** |

0.211** 0.231 / 0.074^ |

n.s | 0.635*** 0.667 / 0.219^^ |

0.757*** 0.779 / 0.560^^^ |

n.s |

| Institutional Enhancers → Planet (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | 0.314*** 0.276 / 0.051^ |

-0.500*** -0.517 / 0.266^^ |

n.s | -0.730*** -0.758 / 0.346^^ |

n.s |

| Institutional Enhancers → Resources (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.106* 0.121 / 0.028^ |

n.s | 0.221** 0.334 / 0.164^^ |

0.844*** 0.822 / 0.309^^ |

0.529*** 0.617 / 0.305^^ |

0.604*** 0.619 / 0.390^^^ |

0.324*** 0.326 / 0.090^ |

| Institutional Enhancers → Peace (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.556*** 0.566 / 0.403^^^ |

n.s | n.s | 0.509*** 0.514 / 0.355^^^ |

0.653*** 0.628 / 0.375^^^ |

-0.574*** -0.582 / 0.242^^ |

n.s |

| Institutional Enhancers → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.302*** -0.238 / 0.023^ |

0.272** 0.251 / 0.078^ |

0.139* 0.263 / 0.075^ |

-0.443*** -0.403 / 0.064^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s |

| Financial Enhancers → People (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | 0.284*** 0.309 / 0.100^ |

n.s | -0.246*** -0.247 / 0.037^ |

n.s | -0.278*** -0.285 / 0.068^ |

-0.349*** -0.398 / 0.183^^ |

| Relationships | Advanced Economies |

Emerging & Developing Europe |

Emerging & Developing Asia |

Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan | Latin America & the Caribbean | Sub Saharan Africa |

Commonwealth |

| Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects / Effect Sizes |

|

| Financial Enhancers → Prosperity (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | 0.378*** 0.377 / 0.207^^ |

0.439*** 0.443 / 0.231^^ |

0.255*** 0.253 / 0.103^ |

-0.534*** -0.539 / 0.166^^ |

-0.238*** -0.244 / 0.093^ |

-0.402*** -0.445 / 0.165^^ |

| Financial Enhancers → Planet (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.625*** 0.626 / 0.131^ |

0.544*** 0.552 / 0.025^ |

0.483*** 0.485 / 0.194^^ |

| Financial Enhancers → Resources (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | 0.205* 0.226 / 0.062^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s | -0.213*** -0.216 / 0.070^ |

n.s |

| Financial Enhancers → Peace (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.101* -0.099 / 0.028^ |

0.496*** 0.528 / 0.229^^ |

-0.286*** -0.248 / 0.037^ |

0.273*** 0.272 / 0.155^^ |

0.179** 0.182 / 0.059^ |

0.321*** 0.323 / 0.036^ |

0.578*** 0.540 / 0.262^^ |

| Financial Enhancers → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | 0.212* 0.155 / 0.039^ |

n.s | 0.237** 0.331 / 0.032^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s |

| GC-Ins → People (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.425*** | -0.257* | -0.135* | -0.283*** | n.s | n.s | -0.234** |

| GC-Ins → Prosperity (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.352*** | n.s | 0.533*** | 0.186** | -0.411*** | n.s | n.s |

| GC-Ins → Planet (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.221*** | 0.656*** | 0.556*** | -0.152* | -0.758*** | 0.269*** | n.s |

| GC-Ins → Resources (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | -0.533*** | 0.653*** | -0.434*** | -0.444*** | 0.249*** | n.s |

| GC-Ins → Peace (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.192*** | -0.427*** | 0.230** | n.s | -0.452*** | n.s | n.s |

| GC-InnS → People (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | -0.160* | 0.327*** | 0.210** | n.s | 0.309*** | 0.397*** |

| GC-InnS → Prosperity (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.362*** | -0.340*** | -0.418*** | 0.223** | 0.459*** | 0.316*** | 0.324*** |

| GC-InnS → Planet (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.167*** | -0.569*** | -0.784*** | n.s | 0.558*** | -0.509*** | n.s |

| GC-InnS → Resources (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.251*** | 0.979*** | n.s | n.s | 0.708*** | n.s | 0.502*** |

| GC-InnS → Peace (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | 0.331*** | 0.155* | 0.273*** | -0.101* | 0.230** |

| People → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.198*** | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.110* | 0.223*** | 0.254** |

| Prosperity → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

-0.099* | n.s | 0.465*** | n.s | -0.311*** | 0.212*** | 0.556*** |

| Planet → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | -0.213** | n.s | 0.524*** | n.s | -0.643*** |

| Resources → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

n.s | n.s | 0.185** | -0.146* | 0.316** | -0.231*** | -0.597*** |

| Peace → H&LS (“Social-turn 1.2”) |

0.153*** | n.s | -0.325*** | 0.202** | n.s | 0.252*** | n.s |

| Notes: Significance Level: *p < 0.05, **p <0.01, ***p<0.001. Effect sizes ^ 0.02 < e < 0.15 = Low effect size, ^^ 0.15 < e < 0.35 = Medium effect size, ^^^ e > 0.35 = Strong effect size. n.s.: Nonsignificant results. | |||||||

| SD Pillars ↓ H&LS |

Advanced Economies |

Emerging & Developing Europe |

Emerging & Developing Asia |

Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan | Latin America & the Caribbean | Sub Saharan Africa | Commonwealth |

| Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

|

| People → H&LS “Social-turn 1” |

0.234*** 0.234 / 0.046^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.265* 0.265 / 0.107^ |

| People → H&LS “Social-turn 1.2” |

0.198*** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.110* | 0.223*** | 0.254** |

| People → H&LS “Social-turn 2” |

0.172*** 0.190 / 0.038^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.123* 0.220 / 0.024^ |

0.207* 0.123 / 0.050^ |

| Prosperity → H&LS “Social-turn 1” | n.s | n.s | 0.453*** 0.453 / 0.166^^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.560*** 0.560 / 0.366^^^ |

| SD Pillars ↓ H&LS |

Advanced Economies |

Emerging & Developing Europe |

Emerging & Developing Asia |

Middle East, North Africa & Pakistan | Latin America & the Caribbean | Sub Saharan Africa | Commonwealth |

| Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

Path Coeff. Total Effects/ Effect Sizes |

|

| Prosperity → H&LS “Social-turn 1.2” | -0.099* | n.s. | 0.465*** | n.s. | -0.311*** | 0.212*** | 0.556*** |

| Prosperity → H&LS “Social-turn 2” | 0.096 0.156 / 0.026^ |

0.120 0.148 / 0.027^ |

0.331*** 0.388 / 0.142^ |

n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.498*** 0.502 / 0.331^^ |

| Planet → H&LS “Social-turn 1” |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.474*** 0.474 / 0.198^^ |

n.s | 0.630*** 0.630 / 0.341^^ |

| Planet → H&LS “Social-turn 1.2” |

n.s. | n.s. | -0.213** | n.s. | 0.524*** | n.s. | -0.643*** |

| Planet → H&LS “Social-turn 2” |

n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.446*** 0.472 / 0.197^^ |

n.s | 0.322*** 0.275 / 0.149^^ |

| Resources- H&LS “Social-turn 1” |

n.s | n.s | n.s | 0.193 0.201 / 0.333^^ |

0.200** 0.200 / 0.036^ |

0.273*** 0.273 / 0.019^ |

0.583*** 0.583 / 0.058^ |

| Resources- H&LS “Social-turn 1.2” |

n.s. | n.s. | 0.185** | -0.146* | 0.316** | -0.231*** | -0.597*** |

| Resources- H&LS “Social-turn 2” |

0.167*** 0.141 / 0.029^ |

0.122 0.164 / 0.026^ |

0.151 0.263 / 0.071^ |

n.s | 0.204*** 0.208 / 0.051^ |

n.s | n.s |

| Peace → H&LS “Social-turn 1” |

0.217*** 0.217/ 0.034^ |

n.s | n.s | 0.195 0.150 / 0.023^ |

n.s | 0.187*** 0.187 / 0.020^ |

0.085 0.085 / 0.028^ |

| Peace → H&LS “Social-turn 1.2” |

0.153*** | n.s. | -0.325*** | 0.202** | n.s. | 0.252*** | n.s. |

| Peace → H&LS “Social-turn 2” |

0.103 0.175 / 0.042^ |

n.s | 0.342*** 0.327 /0.062^ |

0.208 0.208 / 0.025^ |

n.s | 0.183** 0.254 / 0.027^ |

n.s |

| Notes: Significance level: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 Effect Sizes ^ 0.02 < e < 0.15 = Low effect size, ^^ 0.15 < e < 0.35 = Medium effect size, ^^^ e > 0.35 = Strong effect size. n.s.: Nonsignificant results. | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).