1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for over 19.2 million deaths in 2023 and one in three global fatalities.[

1] Innovations in diagnosis and management have significantly improved outcomes; however, the burden persists, especially in low-resource settings.

CAD, resulting from occlusion of the coronary arteries and causing a demand-supply mismatch of oxygen, can lead to severe complications such as acute coronary syndrome and heart failure.[

2] Despite significant progress in prevention and treatment, the global burden of CAD continues to rise, highlighting the need for advancements in diagnostic, interventional, and therapeutic strategies.[

3]

Dyslipidaemia, hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes, genetics, immune responses, and infections can increase the risk of developing CAD. These conditions contribute to the gradual buildup of plaque in the arteries.[

4] Many personal factors affect how individuals respond to CAD treatment. Using a tailored approach based on individual risks—like bleeding or ischemia—can lead to better outcomes, but choosing the proper treatment for each person is still a challenge.[

5] Risk stratification is essential for guiding treatment decisions in both acute and chronic cases of the disease. A range of invasive and non-invasive methods can be used to tailor care based on individual patient profiles.[

5]

This review brings together the most recent developments in CAD management, with an emphasis on three primary areas: advancements in diagnostics, progress in interventional cardiology, and breakthroughs in pharmacological therapy.

Despite these advancements, several critical challenges remain unaddressed in CAD management, including the need for validated biomarkers and imaging modalities to identify vulnerable atheroma before symptoms arise.[

5]

2. Methods

This narrative review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in the diagnosis, intervention, and pharmacological management of CAD, with a focus on emerging technologies shaping its future. A narrative review approach was employed to integrate evidence from diverse sources, including clinical trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and preclinical studies, to provide a comprehensive overview of the current landscape and emerging trends in CAD management. This review is structured around four key domains —diagnostic innovations, advances in interventional cardiology, pharmacological breakthroughs, and future directions —that reflect the multifaceted evolution of CAD care.

The literature included in this review was sourced from original research articles and review papers published between January 2010 and December 2025. These references were identified through systematic literature search on PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and institutional websites (e.g., The University of Edinburgh), using keywords such as "coronary artery disease," "CT angiography," "artificial intelligence," "fractional flow reserve," "high-sensitivity troponin," "lipoprotein(a)," "drug-eluting stents," "robotic PCI," "SGLT2 inhibitors," "nanomedicine," "3D bioprinting,” " lipid-lowering agents, " and " drug-coated balloons.” Case reports, series, and editorials were excluded.

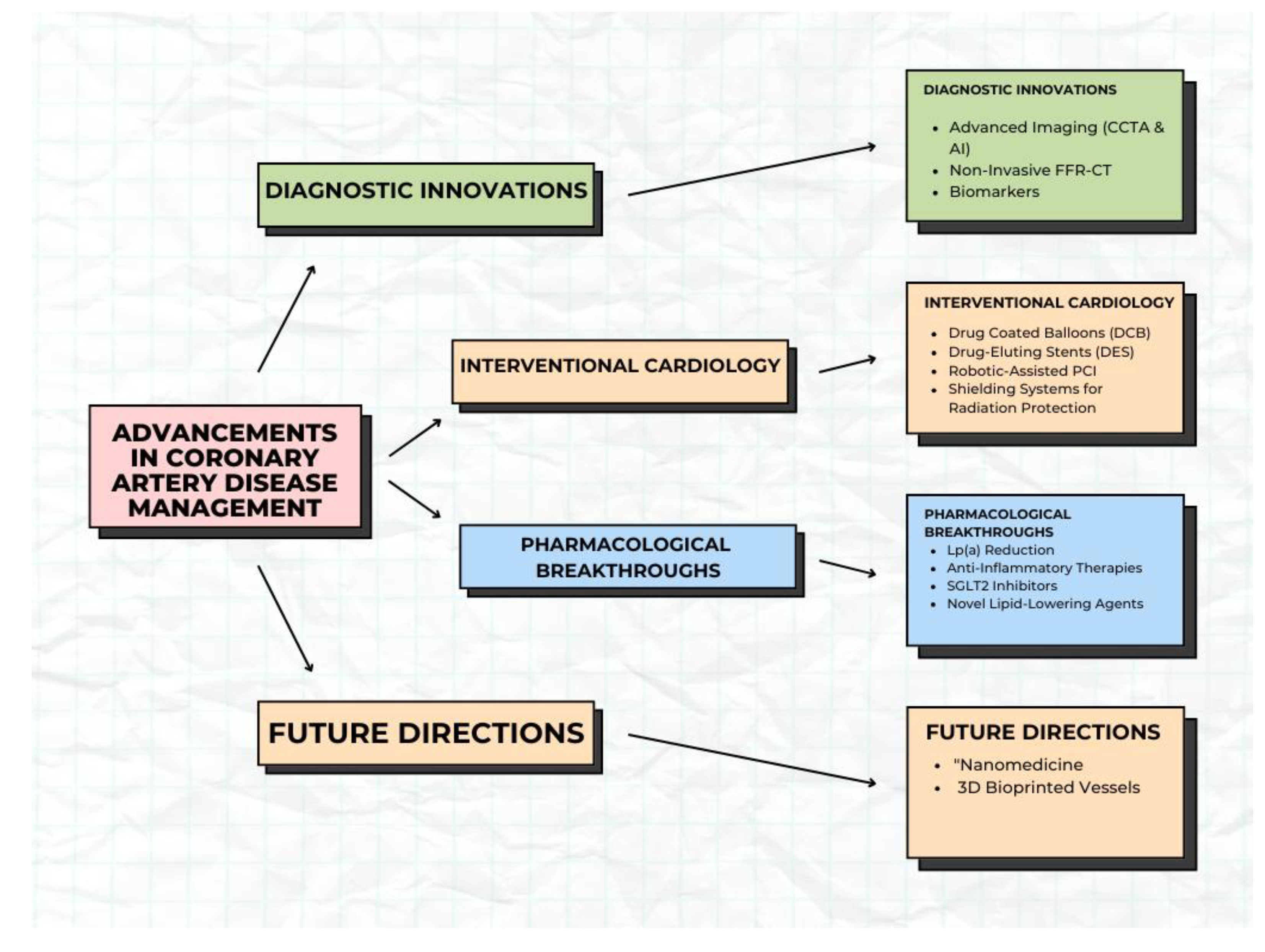

Figure 1.

Subtopics under the advancement in coronary artery disease.

Figure 1.

Subtopics under the advancement in coronary artery disease.

3. Diagnostic Innovations

3.1. Advanced Imaging Techniques

3.1.1. High-Resolution CT Angiography and AI-Driven Analysis for Early Plaque Detection

High-resolution coronary computerised tomography coronary angiography (CTCA), enabled by multidetector CT scanners, provides detailed imaging of the heart and coronary arteries, making it a class 1, evidence level A tool for detecting CAD.[

6] While effective in identifying coronary calcium, plaque, and stenosis significance, its labour-intensive nature and demands highly skilled experts for image interpretation limit accessibility.[

7] Advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, enhance CTCA by accelerating analysis, detecting high-risk plaque features, and enabling precise risk stratification.[

8] AI also supports longitudinal studies on plaque progression and treatment efficacy, advancing personalised CAD management.[

8] This integration promises improved early detection, diagnosis, and patient outcomes.[

8]

3.1.2. Non-Invasive Fractional Flow Reserve (FFR-CT) to Assess Blood Flow

FFR-CT is a computational post-processing technique that is applied to standard CT (CTCA) images. It employs artificial intelligence and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to analyse hemodynamic parameters, aiding in the identification of ischemia-inducing coronary lesions. Unlike traditional CTCA, which provides only anatomical details, FFR-CT adds a functional perspective, enhancing diagnostic accuracy. By combining FFR-CT with plaque characterisation, clinicians can better stratify patient risk and make informed treatment decisions.[

9,

10,

11,

12]

FFR-CT can effectively minimise unnecessary invasive procedures, thereby reducing the potential complications associated with them. Specifically, individuals with FFR-CT values exceeding 0.80 generally exhibit results similar to those without substantial coronary artery disease. Integrating FFR-CT into diagnostic workflows also contributes to lower healthcare expenses, mainly by reducing the need for invasive angiography. For example, data from the PLATFORM trial show that using CTCA combined with FFR-CT can substantially reduce costs in comparison to traditional approaches relying on immediate ICA.[

9,

13]

Despite the ongoing advancements in FFR-CT technology, including improved AI models and real-time analysis, challenges such as image quality dependency, computational demands, and the need for widespread clinical validation remain. Further research is needed to expand its applicability to more complex cases, such as multi-vessel disease and in-stent restenosis assessment.[

14]

3.2. Biomarkers

3.2.1. High-Sensitivity Troponin Assays for Early Detection of Myocardial Injury

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays have revolutionised the early detection of myocardial injury, particularly in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction (AMI). These assays enable the measurement of very low concentrations of cardiac troponins, allowing for the identification of minor myocardial injuries that were previously undetectable with conventional assays.[

15]

The primary advantage of hs-cTn assays lies in their ability to rapidly and accurately rule out AMI in patients with chest pain. Studies have demonstrated that a single hs-cTn measurement at presentation, with thresholds near the assay's limit of detection, can effectively exclude AMI. For instance, a systematic review highlighted that a single test at presentation using a threshold at or near the assay limit of detection could reliably rule out non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) for various hs-cTn assays.[

15]

Moreover, serial hs-cTn measurements enhance diagnostic accuracy by detecting dynamic changes in troponin levels and distinguishing acute from chronic myocardial injury. This approach is particularly beneficial for patients presenting early after symptom onset, as initial troponin values may be normal owing to the time dependency of troponin release. A meta-analysis indicated that serial measurement strategies are necessary in early presenters to overcome the troponin-blind period typically seen in the early hours of AMI.[

16]

Due to the increased sensitivity, troponin elevations can be observed in a broader range of conditions, including type 1 myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, cardiac arrhythmias, myocarditis, sepsis and other cardiac and non-cardiac conditions. It is crucial to interpret troponin results within the context of the patient’s clinical presentation, including symptoms and ECG findings. Serial troponin sampling is essential not only to permit the safe rule-out of myocardial infarction but also to minimise the risk of misdiagnosis in patients with elevated cardiac troponin concentrations.[

17,

18]

3.2.2. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a crucial role in immune response and inflammation. IL-6 is involved in the activation of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and has been shown to promote endothelial dysfunction, which is a critical step in the development of atherosclerosis.[

19]

Elevated IL-6 levels have been consistently associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, including higher rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. For instance, a narrative review summarising data from prospective studies found that higher IL-6 levels correlate with adverse cardiovascular outcomes across diverse populations.[

19]

The relationship between IL-6 and CAD severity has also been explored using angiographic assessments. A study stratified by IL-6 levels in patients with CAD found that higher IL-6 levels are associated with greater disease severity, as indicated by higher Gensini scores and more extensive arterial involvement. This finding underscores IL-6’s role as a predictor of CAD progression.[

20]

3.2.3. Lipoprotein [Lp(a)]

Lipoprotein (Lp [a] ) is a lipoprotein variant consisting of an LDL-like particle attached to a specific protein called apolipoprotein(a). Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, particularly CAD. Unlike other lipoproteins, Lp(a) levels are primarily determined by genetics and remain relatively stable throughout an individual’s life.[

21,

22]

Lp(a) has been shown to promote atherogenesis through several mechanisms, including inhibition of fibrinolysis, endothelial dysfunction, and increased arterial wall cholesterol deposition. Elevated Lp(a) levels have been linked to an increased risk of CAD, particularly in individuals who have a family history of premature cardiovascular disease.[

21]

Lp(a) is associated with coronary artery calcification, a marker of atherosclerotic burden. Research indicates that elevated Lp(a) levels are associated with increased coronary artery calcification, suggesting a role in plaque development and stability.

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that elevated Lp(a) levels predict plaque progression in patients with CAD. This finding highlights the potential of Lp(a) as a biomarker for monitoring disease progression and tailoring therapeutic strategies.[

23]

A subsequent analysis revealed that elevated Lp(a) concentrations exceeding 100 mg/dL were independently associated with an increased risk of severe degenerative aortic stenosis and the subsequent need for aortic valve replacement, irrespective of the initial severity of stenosis.[

24]

In summary, accumulating evidence positions IL-6 and Lp(a) as crucial markers for predicting CAD progression. Their measurement could enhance risk stratification and inform personalised treatment strategies. Ongoing research is essential to fully elucidate their roles and develop targeted interventions to mitigate their pro-atherogenic effects.

4. Advances in Interventional Cardiology for Coronary Artery Disease

The evolution of interventional cardiology has significantly improved the management of CAD, which is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. This review focuses on three pivotal areas: drug-coated balloons, drug-eluting stents (DES), and robot-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). These technologies address complex clinical challenges and enhance outcomes for CAD patients by enabling precision, ensuring safety, and reducing complication rates.[

25]

4.1. Drug-Coated Balloons in CAD Management

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) are a promising therapeutic modality for the management of CAD, providing targeted pharmacological intervention without the need for permanent vascular scaffold placement. Originally designed to address in-stent restenosis (ISR), their utility has expanded to include small-calibre vessels and bifurcation lesions, where conventional stenting may pose technical or long-term challenges.[

26,

27]

4.1.1. DCBs for ISR

ISR remains the most well-established indication for DCB therapy, primarily because it allows avoiding the use of multiple metallic stent layers. Among the available technologies, paclitaxel-coated balloons have undergone extensive evaluation in randomised controlled trials and now serve as the standard for emerging DCB platforms. Comparative studies have consistently demonstrated the superiority of DCBs over conventional balloon angioplasty for ISR management, with notable reductions in luminal narrowing and the need for repeat revascularisation procedures.[

27,

28,

29]

4.1.2. DCB in Denovo Lesion

Early comparisons between DCBs and DES for de novo small vessel lesions, such as in the PICOLETTO trial, revealed limitations of first-generation DCBs. It was primarily due to suboptimal drug delivery and inadequate vessel preparation.[

30] However, subsequent randomised trials using improved paclitaxel-coated balloons demonstrated noninferiority to DES, supporting a DCB-only strategy in select cases.[

31,

32]

4.1.3. Future of DCBs

Bifurcation lesions pose procedural challenges and are associated with suboptimal long-term outcomes, making drug-coated balloons (DCBs) in the side branches an attractive alternative to conventional angioplasty. While observational data suggest improved patency and safety at 12 months, randomised trials remain limited and mixed in outcomes.[

33,

34]

In addition to bifurcations, DCBs may offer distinct advantages in specific populations. Their scaffold-free design reduces vessel trauma and may lower the risk of thrombosis, potentially shortening the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. This is particularly beneficial for patients at high risk of bleeding.[

35] DCBs hold particular promise in patients with diabetes, where coronary disease tends to diffuse with longer lesions and DES underperforms with a higher incidence of ISR. DCBs may allow for shorter stented segments but longer areas of treatment, with the option of bail-out stenting if required, thereby decreasing the risk of restenosis.[

27]

4.2. Drug-Eluting Stents in CAD Management

4.2.1. Historical Context

Bare-metal stents (BMS) were the first breakthrough in CAD treatment, reducing acute vessel recoil and restenosis rates. However, the limitations of BMS, including high rates of in-stent restenosis (up to 30%), led to the development of DES. These stents combine a metallic scaffold, a polymer coating, and an antiproliferative drug to prevent neointimal hyperplasia. [

36]

4.2.2. Modern Innovations

Contemporary DES are engineered with ultrathin struts, typically below 80 microns, enhancing deliverability through tortuous vessels, minimising vessel trauma, and accelerating endothelial healing. At the same time, clinical studies highlight their improved outcomes in patients with complex anatomies, including bifurcations and calcified lesions.[

37]

- 2.

Biodegradable Polymers

Bioresorbable polymer coatings in drug-eluting stents, such as the Orsiro DES and Synergy stent, release their therapeutic drug over a predetermined period before degrading, leaving a bare-metal scaffold that reduces the long-term risk of late stent thrombosis.[

38,

39]

- 3.

Polymer-Free Stents

The BioFreedom stent exemplifies an innovative approach to stent design by employing microporous or nanoporous surfaces for drug delivery, eliminating the need for a polymer coating and thereby addressing concerns about polymer-induced inflammation and hypersensitivity.[

40]

- 4.

Advanced Drugs

Antiproliferative Agents: Modern DES employ sirolimus analogues such as everolimus, zotarolimus, and biolimus, which are more effective and better tolerated than earlier agents, such as paclitaxel.[

39]

4.2.3. Clinical Benefits

DES have significantly reduced restenosis rates to 2–10%, compared to 30% with BMS. At the same time, biodegradable polymers lower the risk of late thrombosis, and faster endothelial coverage shortens the required duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, offering particular benefits for patients at high bleeding risk.[

39,

41]

4.2.4. Challenges

Neoatherosclerosis, characterised by the development of new atherosclerotic plaques within the stent, poses a challenge for advanced DES, which, despite their benefits, are more expensive and thus less accessible in specific healthcare settings. At the same time, research continues to explore personalised approaches to stent selection.[

42]

4.3. Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Robotic percutaneous coronary intervention (R-PCI) is an innovative method for PCI, enabling operators to remotely manipulate guidewires and catheter devices via advanced, precision-controlled technology.[

10,

43]

4.3.1. Key Features

Robotic systems, such as the CorPath GRX, provide sub-millimetre accuracy, essential for navigating complex lesions, including bifurcations and chronic total occlusions, enabling precise stent and balloon placement.[

43,

44]

- 2.

Radiation Protection

Operators work from a shielded console, minimising radiation exposure and alleviating the need for heavy lead aprons.[

10,

44,

45,

46]

- 3.

Remote Operation (Tele-Stenting)

When controlled remotely, robotic systems enable the expansion of advanced treatment capabilities to underserved regions. For instance, proof-of-concept trials have demonstrated the success of tele-stenting procedures, showcasing the potential of this technology to revolutionise access to specialised care.[

47]

4.3.2 Clinical and Operator Benefits

Improved procedural accuracy, achieved through enhanced precision, minimises complications, such as malposition and edge dissection. This advancement has led to higher success rates, particularly in cases involving high-risk or anatomically challenging lesions. [

43]Furthermore, operator ergonomics are significantly improved, reducing physical strain and occupational hazards, which contribute to a safer and more efficient procedural environment. [

47]

Challenges

The adoption of robotic systems is hindered by their high cost, which makes them less accessible in low-resource settings. Additionally, their practical use requires extensive training and experience to achieve optimal outcomes. Current robotic systems also face limitations when addressing complex cases, such as multi-vessel disease and highly tortuous anatomies, further restricting their application in specific scenarios.[

48]

4.4. Shielding Systems for Radiation Protection

Interventional cardiology procedures expose medical personnel to significant ionising radiation, leading to occupational health risks such as cataracts, thyroid disorders, and musculoskeletal issues from heavy lead aprons.[

49,

50] To address these concerns, advanced fixed shielding systems have emerged as vital innovations. These systems create a protective barrier between the operator and the radiation source, aligning with the "As Low As Reasonably Achievable" (ALARA) principle and facilitating a shift towards a "lead-free" environment in cardiac catheterisation laboratories by minimising the reliance on traditional personal protective equipment.[

49]

Innovations in fixed shielding include comprehensive integrated systems, such as the Protego radiation shielding system (Image Diagnostics Inc.), and suspended-body shielding units, such as the Zero-Gravity system (BIOTRONIK). The Protego system features an angulated upper shield, a lower shield, accessory side shields, flexible drapes with vascular access portals, and specialised arm boards, all designed to allow unimpeded C-arm motion while providing superior protection against radiation exposure.[

50] The Zero-Gravity system, a 1-mm lead body shield suspended from the floor or ceiling, effectively reduces operator radiation exposure and alleviates the orthopaedic strain associated with lead aprons.[

49]

The adoption of these fixed shielding systems offers substantial benefits, including enhanced and consistent radiation protection and significantly reduced operator radiation exposure, well below recommended safety limits. They also mitigate the orthopaedic burden on interventional cardiologists, improving comfort, focus, and career longevity. These technologies represent a critical advancement in occupational radiation safety within interventional cardiology, ultimately benefiting both medical staff and patients.[

49,

50]

5. Pharmacological Breakthroughs

5.1. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction

Elevated lipoprotein (a) [Lp (a)] levels are an independent risk factor for CAD. Muvalaplin demonstrated a reduction in lipoprotein(a) levels, as assessed through both intact lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a)-based assays, while exhibiting good tolerability. Further studies are required to evaluate their impact on cardiovascular outcomes.[

51]

Furthermore, Evolocumab effectively lowers lipoprotein(a) levels, with patients who start with higher levels showing larger drops and gaining more heart-related benefits from PCSK9 inhibitor treatment.[

52]

5.2. Anti-Inflammatory Therapies

Chronic inflammation plays a pivotal role in atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular events. The CANTOS trial investigated canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, and revealed that targeting inflammation without affecting cholesterol levels can significantly reduce recurrent cardiovascular events. This approach represents a transformative change in CAD management, focusing on the inflammatory component of the disease.[

53,

54]

5.3. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

Initially developed for the management of type 2 diabetes, SGLT2 inhibitors have shown cardiovascular benefits. [

55] Sotagliflozin (Inpefa), a novel SGLT inhibitor, demonstrated a 23% reduction in heart attacks, strokes, and cardiovascular-related deaths compared to placebo. This positions sotagliflozin as a multifaceted therapeutic agent addressing interconnected health issues such as heart failure and diabetes.[

56]

Among the available SGLT2 inhibitors, dapagliflozin has emerged as a cornerstone therapy for cardiovascular care. The DAPA-HF trial established dapagliflozin’s efficacy in reducing the risk of worsening heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with reduced ejection fraction, regardless of diabetes status.[

57] More recently, the DAPA-MI trial evaluated dapagliflozin in patients with acute myocardial infarction without prior diabetes or chronic heart failure. The study demonstrated improved cardiometabolic outcomes, including reduced incidence of new-onset type 2 diabetes and favourable weight reduction. However, it did not show a statistically significant reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events compared to placebo.[

58]

5.4. New, Novel Lipid-Lowering Agents for Reducing Cardiovascular Risk

Advancements in lipid-lowering therapies beyond traditional statins for managing coronary artery disease (CAD), like proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors (evolocumab and alirocumab), which effectively reduce LDL cholesterol levels and lower cardiovascular risk, particularly in patients intolerant to statins. [

59,

60]Another breakthrough is inclisiran, an siRNA-based therapy that provides sustained LDL reduction with biannual dosing, enhancing patient adherence.[

60] In a recent meta-analysis, inclisiran was shown to substantially reduce total cholesterol, ApoB, and non-HDL-C, respectively, by 37%, 41%, and 45%.[

61]

6. Future Directions & Challenges

Atherosclerosis, a leading cause of heart attacks and strokes, is primarily driven by hypercholesterolemia and chronic inflammation within arterial walls.[

3] Although statins and other standard therapies can slow disease progression, they often come with limitations such as side effects, high costs, and an inability to reverse established plaques.[

62] In advanced cases, surgical interventions like coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are necessary, yet these procedures face significant hurdles, including limited graft availability and complications related to surgical trauma.[

63] Given these challenges, innovative approaches such as nanomedicine and 3D bioprinting have emerged as promising alternatives for improving cardiovascular treatment.

6.1. Advancements in Nanomedicine

Nanomedicine, which utilises nanoparticles and nanocarriers to deliver drugs directly to atherosclerotic plaques, is revolutionising the management of cardiovascular disease.[

64]These nanoparticles can be engineered to target inflamed arterial sites, increasing drug accumulation in plaques while minimising off-target effects.[

65]

Cholesterol clearance is a promising application of nanomedicine. Supramolecular nanotherapy has demonstrated the ability to dissolve cholesterol crystals, reducing plaque burden in preclinical studies.[

65] Additionally, nanoparticles designed to inhibit macrophage-driven inflammation have been shown to stabilise plaques by blocking inflammatory signals. [

66] Beyond plaque reduction, some nanosystems also facilitate vascular repair by restoring endothelial function, stabilising vessel walls, and preventing further narrowing of arteries.[

67]

Although these advancements are promising, translating nanomedicine from preclinical models to clinical applications remains challenging. Although lipid nanoparticle-based cholesterol efflux therapies have demonstrated efficacy in laboratory studies, only a few nanomedicine treatments have progressed to human trials.[

68] Further research is needed to refine nanoparticle formulations, improve targeting precision, and ensure safety before widespread clinical adoption.[

68,

69]

6.2. 3D-Printed Artificial Blood Vessels

In addition to nanomedicine, 3D bioprinting is emerging as a revolutionary technology in cardiovascular surgery. Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have developed a novel 3D bioprinting technique to fabricate artificial blood vessels that mimic natural veins.[

70] The process involves printing a tubular gelatin hydrogel on a rotating spindle, followed by electrospinning an ultrathin biodegradable polyester nanofiber coating to enhance mechanical strength.[

71]

These 3D-printed vascular grafts offer several advantages over conventional grafts. By eliminating the need for vein harvesting, they reduce surgical trauma, post-operative pain, and the risk of infection.[

70,

71] Additionally, they are designed to be more biocompatible than synthetic small-diameter grafts, which often fail due to poor integration and thrombosis. [

71,

72] Future iterations of these grafts may incorporate patient-derived cells, creating living vessels that promote long-term integration and function.[

72]

Despite their potential, 3D-printed blood vessels remain in the preclinical stages. Ongoing studies are evaluating their durability, patency, and integration with native tissue in animal models. Before they can be used widely in cardiovascular surgery, large-scale human trials will be necessary to confirm their safety and efficacy.[

72]

6.3. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Emerging technologies such as nanomedicine and 3D bioprinting have the potential to enhance current cardiovascular treatment strategies significantly. Targeted nanoparticle therapies have the potential to stabilise or shrink plaques, potentially reducing the need for invasive procedures. [

73] Meanwhile, customised 3D-printed grafts may serve as durable and biocompatible replacements for diseased blood vessels, addressing a long-standing challenge in CABG surgery.[

70,

71,

72]

However, several hurdles remain before these technologies can be fully integrated into clinical practices. For nanomedicine, concerns about safety, scalability, and regulatory approval must be addressed.[

69] Similarly, for 3D-printed blood vessels, extensive testing in human trials is required to establish long-term outcomes and reliability.[

73]

As research progresses, these advancements in nanomedicine and 3D bioprinting are expected to revolutionise cardiovascular therapy, offering new hope to patients with atherosclerosis and other vascular diseases.

7. Discussion

Despite significant advancements in the diagnosis, intervention, and pharmacological treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD), several challenges continue to hinder optimal patient outcomes clinically and economically.

Clinically, current care pathways remain heavily focused on late-stage ischemia and obstructive lesions, often overlooking the early detection of subclinical atheroma. This reactive model delays intervention until irreversible myocardial damage has occurred. Although emerging imaging modalities and biomarkers offer promise for earlier diagnosis, their routine implementation remains limited by cost, availability, and guideline inertia.

From the economic prospective, the burden of CAD is profound. In 2023, global healthcare spending on cardiovascular disease exceeded

$1 trillion, with CAD accounting for a substantial proportion of direct and indirect costs.[

74] Hospitalizations, long-term pharmacotherapy, and productivity losses due to disability contribute to this financial strain. Investment in early detection and population-based prevention strategies could hold substantial long-term savings and reduce reliance on high-cost interventions.

8. Conclusion

While technological and therapeutic advances have reshaped the landscape of CAD management, addressing these persistent clinical, economic, and accessibility challenges is vital to reducing the global burden of disease. Future efforts must prioritize early detection, equitable access, and cost-effective, personalized care to achieve sustainable improvements in cardiovascular outcomes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AMI |

Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| BMS |

Bare-Metal Stents |

| BVS |

Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds |

| CABG |

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| CTCA |

Computerised tomography Coronary Angiography |

| CFD |

Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| DCB |

Drug Coated Stent |

| DES |

Drug-Eluting Stents |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| FFR-CT |

Fractional Flow Reserve derived from CT |

| hs-cTn |

High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin |

| ICA |

Invasive Coronary Angiography |

| ISR |

In-Stent Restenosis |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| Lp(a) |

Lipoprotein(a) |

| NSTEMI |

Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| PCI |

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PCSK9 |

Protein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 |

| R-PCI |

Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| SGLT2 |

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 |

References

- Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2023. JACC [Internet]. 2025 Sep [cited 2025 Oct 6]; Available from: http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2flatest-in-cardiology%2fjournal-scans%2f2025%2f09%2f24%2f21%2f17%2fnew-global-burden.

- Malakar AK, Choudhury D, Halder B, Paul P, Uddin A, Chakraborty S. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J Cell Physiol [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];234(10):16812–23. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30790284/.

- Kim MS, Hwang J, Yon DK, Lee SW, Jung SY, Park S, et al. Global burden of peripheral artery disease and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2023 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];11(10):e1553–65. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2214109X23003558.

- Dave T, Ezhilan J, Vasnawala H, Somani V. Plaque regression and plaque stabilisation in cardiovascular diseases. Indian J Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Oct 10];17(6):983. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3872716/.

- Buccheri S, D’Arrigo P, Franchina G, Capodanno D. Risk Stratification in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Practical Walkthrough in the Landscape of Prognostic Risk Models. Interventional Cardiology Review [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Oct 10];13(3):112. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6234492/.

- Mézquita AJV, Biavati F, Falk V, Alkadhi H, Hajhosseiny R, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Clinical quantitative coronary artery stenosis and coronary atherosclerosis imaging: a Consensus Statement from the Quantitative Cardiovascular Imaging Study Group. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet]. 2023 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Mar 27];20(10):696–714. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37277608/.

- Föllmer B, Williams MC, Dey D, Arbab-Zadeh A, Maurovich-Horvat P, Volleberg RHJA, et al. Roadmap on the use of artificial intelligence for imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in coronary arteries. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Mar 27];21(1):51–64. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37464183/.

- van Herten RLM, Lagogiannis I, Leiner T, Išgum I. The role of artificial intelligence in coronary CT angiography. Netherlands Heart Journal [Internet]. 2024 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Mar 27];32(11):417–25. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12471-024-01901-8.

- Wu J, Yang D, Zhang Y, Xian H, Weng Z, Ji L, et al. Non-invasive imaging innovation: FFR-CT combined with plaque characterization, safeguarding your cardiac health. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Mar 28];19(1):152–8. Available from: https://www.journalofcardiovascularct.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1934592524004337.

- Bottardi A, Prado GFA, Lunardi M, Fezzi S, Pesarini G, Tavella D, et al. Clinical Updates in Coronary Artery Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, Vol 13, Page 4600 [Internet]. 2024 Aug 6 [cited 2025 Apr 7];13(16):4600. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/16/4600/htm.

- Nørgaard BL, Sand NP, Jensen JM. Is CT-derived fractional flow reserve superior to ischemia testing? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 7];20(3):165–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35345959/.

- Yang J, Shan D, Wang X, Sun X, Shao M, Wang K, et al. On-Site Computed Tomography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide Management of Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The TARGET Randomized Trial. Circulation [Internet]. 2023 May 2 [cited 2025 Oct 6];147(18):1369–81. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Douglas PS, De Bruyne B, Pontone G, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. 1-Year Outcomes of FFRCT-Guided Care in Patients With Suspected Coronary Disease: The PLATFORM Study. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2016 Aug 2 [cited 2025 Mar 28];68(5):435–45. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27470449/.

- Mastrodicasa D, Albrecht MH, Schoepf UJ, Varga-Szemes A, Jacobs BE, Gassenmaier S, et al. Artificial intelligence machine learning-based coronary CT fractional flow reserve (CT-FFRML): Impact of iterative and filtered back projection reconstruction techniques. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Mar 28];13(6):331–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30391256/.

- Westwood ME, Armstrong N, Worthy G, Fayter D, Ramaekers BLT, Grimm S, et al. Optimizing the Use of High-Sensitivity Troponin Assays for the Early Rule-out of Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting with Chest Pain: A Systematic Review. Clin Chem [Internet]. 2021 Jan 8 [cited 2025 Apr 2];67(1):237–44. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Arslan M, Dedic A, Boersma E, Dubois EA. Serial high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurements to rule out acute myocardial infarction and a single high baseline measurement for swift rule-in: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];9(1):14–22. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Shah ASV, Newby DE, Mills NL. High-sensitivity troponin assays and the early rule-out of acute myocardial infarction. Heart [Internet]. 2013 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];99(21):1549–50. Available from: https://heart.bmj.com/content/99/21/1549.

- Maayah M, Grubman S, Allen S, Ye Z, Park DY, Vemmou E, et al. Clinical Interpretation of Serum Troponin in the Era of High-Sensitivity Testing. Diagnostics 2024, Vol 14, Page 503 [Internet]. 2024 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Oct 6];14(5):503. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/14/5/503/htm.

- Mehta NN, deGoma E, Shapiro MD. IL-6 and Cardiovascular Risk: A Narrative Review. Curr Atheroscler Rep [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];27(1):1–16. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11883-024-01259-7.

- Bouzidi N, Gamra H. Relationship between serum interleukin-6 levels and severity of coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Cardiovasc Disord [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];23(1):1–9. Available from: https://bmccardiovascdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12872-023-03570-8.

- Qiu Y, Hao W, Guo Y, Guo Q, Zhang Y, Liu X, et al. The association of lipoprotein (a) with coronary artery calcification: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];388. Available from: https://www.atherosclerosis-journal.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0021915023053261.

- Chung YH, Lee BK, Kwon HM, Min PK, Choi EY, Yoon YW, et al. Coronary calcification is associated with elevated serum lipoprotein (a) levels in asymptomatic men over the age of 45 years: A cross-sectional study of the Korean national health checkup data. Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Mar 5 [cited 2025 Apr 2];100(9):E24962. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655963/.

- Nurmohamed N, Gaillard E, Bom M, De Groot R, Ibrahim S, Jukema R, et al. Lipoprotein(A) is associated with long-term plaque progression on serial coronary CT angiography. Atherosclerosis [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];379:S49. Available from: https://www.atherosclerosis-journal.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0021915023049092.

- Kim AR, Ahn JM, Kang DY, Jun TJ, Sun BJ, Kim HJ, et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) With Severe Degenerative Aortic Valve Stenosis. JACC Asia [Internet]. 2024 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Oct 6];4(10):751. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11561479/.

- Colombo A, Chiastra C, Gallo D, Loh PH, Dokos S, Zhang M, et al. Advancements in Coronary Bifurcation Stenting Techniques: Insights From Computational and Bench Testing Studies. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng [Internet]. 2025 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];41(3):e70000. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11909422/.

- Shahrori ZMF, Frazzetto M, Mahmud SH, Alghwyeen W, Cortese B. Drug-Coated Balloons: Recent Evidence and Upcoming Novelties. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis [Internet]. 2025 May 1 [cited 2025 Oct 6];12(5):194. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12112549/.

- Korjian S, McCarthy KJ, Larnard EA, Cutlip DE, McEntegart MB, Kirtane AJ, et al. Drug-coated balloons in the management of coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2024 May 1 [cited 2025 Oct 6];17(5):E013302. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo D, Gargiulo G, Aruta P, Capranzano P, Tamburino C, Capodanno D. Treatment strategies for coronary in-stent restenosis: systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian network meta-analysis of 24 randomised trials and 4880 patients. BMJ [Internet]. 2015 Nov 4 [cited 2025 Oct 6];351. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26537292/.

- Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, Pinieck S, Wolff B, Tiroch K, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Oct 6];381(9865):461–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23206837/.

- Cortese B, Micheli A, Picchi A, Coppolaro A, Bandinelli L, Severi S, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent during PCI of small coronary vessels, a prospective randomised clinical trial. The PICCOLETO study. Heart [Internet]. 2010 Aug [cited 2025 Oct 6];96(16):1291–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20659948/.

- Jeger R V., Farah A, Ohlow MA, Mangner N, Möbius-Winkler S, Leibundgut G, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2018 Sep 8 [cited 2025 Oct 6];392(10150):849–56. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30170854/.

- Scheller B, Rissanen TT, Farah A, Ohlow MA, Mangner N, Wöhrle J, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon for Small Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With and Without High-Bleeding Risk in the BASKET-SMALL 2 Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Oct 6];15(4):E011569. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35411792/.

- Jim MH, Lee MKY, Fung RCY, Chan AKC, Chan KT, Yiu KH. Six month angiographic result of supplementary paclitaxel-eluting balloon deployment to treat side branch ostium narrowing (SARPEDON). Int J Cardiol [Internet]. 2015 May 6 [cited 2025 Oct 6];187(1):594–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25863309/.

- Herrador JA, Fernandez JC, Guzman M, Aragon V. Drug-eluting vs. conventional balloon for side branch dilation in coronary bifurcations treated by provisional T stenting. J Interv Cardiol [Internet]. 2013 Oct [cited 2025 Oct 6];26(5):454–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24106744/.

- Capodanno D, Alfonso F, Levine GN, Valgimigli M, Angiolillo DJ. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: JACC Guideline Comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2018 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Oct 6];72(23 Pt A):2915–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30522654/.

- Stefanini GG, Byrne RA, Windecker S, Kastrati A. State of the art: coronary artery stents - past, present and future. EuroIntervention [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];13(6):706–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28844032/.

- Stefanini GG, Holmes DRJr. Drug-Eluting Coronary-Artery Stents. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2013 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Apr 2];368(3):254–65. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Abizaid A, Costa JR. New drug-eluting stents an overview on biodegradable and polymer-free next-generation stent systems. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2010 Aug [cited 2025 Apr 2];3(4):384–93. [CrossRef]

- Senst B, Goyal A, Basit H, Borger J. Drug Eluting Stent Compounds. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023 Jul 4 [cited 2025 Apr 2]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537349/.

- Chiarito M, Sardella G, Colombo A, Briguori C, Testa L, Bedogni F, et al. Safety and efficacy of polymer-free drug-eluting stents: Amphilimus-eluting Cre8 versus biolimus-eluting biofreedom stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];12(2). Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim T, Muller O, Heg D, Roffi M, Kurz DJ, Moarof I, et al. Biodegradable- Versus Durable-Polymer Drug-Eluting Stents for STEMI: Final 2-Year Outcomes of the BIOSTEMI Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2021 Mar 22 [cited 2025 Apr 2];14(6):639–48. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Romero ME, Yahagi K, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Neoatherosclerosis from a pathologist’s point of view. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol [Internet]. 2015 Oct 25 [cited 2025 Apr 2];35(10):e43–9. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson A, Kirresh A, Ahmad M, Candilio L. Robotic-Assisted PCI: The Future of Coronary Intervention? Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine. 2022 Feb 1;35:161–8.

- Göbölös L, Ramahi J, Obeso A, Bartel T, Hogan M, Traina M, et al. Robotic Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes from the Past two Decades. Innovations [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 7];14(1):5–16. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Weisz G, Metzger DC, Caputo RP, Delgado JA, Marshall JJ, Vetrovec GW, et al. Safety and feasibility of robotic percutaneous coronary intervention: PRECISE (Percutaneous Robotically-Enhanced Coronary Intervention) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2013 Apr 16 [cited 2025 Apr 2];61(15):1596–600. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23500318/.

- Biso SMR, Vidovich MI. Radiation protection in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];12(4):1648. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7212171/.

- Patel TM, Shah SC, Pancholy SB. Long Distance Tele-Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Report of First-in-Human Experience. EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2019 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];14:53–8. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2589537019301373.

- Fernandez-Garcia C, Ternent L, Homer TM, Rodgers H, Bosomworth H, Shaw L, et al. Economic evaluation of robot-assisted training versus an enhanced upper limb therapy programme or usual care for patients with moderate or severe upper limb functional limitation due to stroke: results from the RATULS randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2021 May 25 [cited 2025 Apr 2];11(5):e042081. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8154983/.

- Roguin A, Wu P, Cohoon T, Gul F, Nasr G, Premyodhin N, et al. Update on Radiation Safety in the Cath Lab – Moving Toward a “Lead-Free” Environment. Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions. 2023 Jul 1;2(4):101040.

- Biso SMR, Vidovich MI. Radiation protection in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Oct 13];12(4):1648. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7212171/.

- Nicholls SJ, Ni W, Rhodes GM, Nissen SE, Navar AM, Michael LF, et al. Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA [Internet]. 2025 Nov 18 [cited 2025 Apr 2];333(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39556768/.

- O’Donoghue ML, Fazio S, Giugliano RP, Stroes ESG, Kanevsky E, Gouni-Berthold I, et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 inhibition, and cardiovascular risk insights from the FOURIER trial. Circulation [Internet]. 2019 Mar 19 [cited 2025 Oct 6];139(12):1483–92. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2017 Sep 21 [cited 2025 Apr 2];377(12):1119–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28845751/.

- Pitt B, Steg G, Leiter LA, Deepak ·, Bhatt L, Bhatt DL, et al. The Role of Combined SGLT1/SGLT2 Inhibition in Reducing the Incidence of Stroke and Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];36(3):561. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9090862/.

- Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, Brown JM, Januzzi JL, Kalyani RR, et al. 2020 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Novel Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 2];76(9):1117–45. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32771263/.

- Aggarwal R, Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, Inzucchi SE, et al. Effect of sotagliflozin on major adverse cardiovascular events: a prespecified secondary analysis of the SCORED randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet]. 2025 Feb 13 [cited 2025 Apr 2];13(4):321–32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39961315.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2019 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Oct 6];381(21):1995–2008. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Rossello X, Gimenez MR. The dapagliflozin in patients with myocardial infarction (DAPA-MI) trial in perspective. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care [Internet]. 2023 Dec 21 [cited 2025 Oct 6];12(12):862–3. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Ginsberg HN, Choi SH. New, Novel Lipid-Lowering Agents for Reducing Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Statins. Diabetes Metab J [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];46(4):517. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9353557/.

- Shapiro MD, Tavori H, Fazio S. PCSK9: From Basic Science Discoveries to Clinical Trials. Circ Res [Internet]. 2018 May 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];122(10):1420. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5976255/.

- Khan SA, Naz A, Qamar Masood M, Shah R. Meta-Analysis of Inclisiran for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2020 Nov 1;134:69–73.

- Kim BK, Hong SJ, Lee YJ, Hong SJ, Yun KH, Hong BK, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet [Internet]. 2022 Jul 30 [cited 2025 Apr 4];400(10349):380–90. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0140673622009163.

- Tamargo IA, Baek KI, Kim Y, Park C, Jo H. Flow-induced reprogramming of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];20(11):738–53. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37225873/.

- Gao M, Tang M, Ho W, Teng Y, Chen Q, Bu L, et al. Modulating Plaque Inflammation via Targeted mRNA Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. ACS Nano [Internet]. 2023 Sep 26 [cited 2025 Apr 4];17(18):17721–39. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37669404/.

- Tao Y, Lan X, Zhang Y, Fu C, Liu L, Cao F, et al. Biomimetic nanomedicines for precise atherosclerosis theranostics. Acta Pharm Sin B [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];13(11):4442. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10638499/.

- Nankivell V, Vidanapathirana AK, Hoogendoorn A, Tan JTM, Verjans J, Psaltis PJ, et al. Targeting macrophages with multifunctional nanoparticles to detect and prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res [Internet]. 2024 May 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];120(8):819. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11218693/.

- Luo X, Pang Z, Li J, Anh M, Kim BS, Gao G. Bioengineered human arterial equivalent and its applications from vascular graft to in vitro disease modeling. iScience [Internet]. 2024 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Apr 4];27(11):111215. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11565542/.

- Guo Y, Yuan W, Yu B, Kuai R, Hu W, Morin EE, et al. Synthetic High-Density Lipoprotein-Mediated Targeted Delivery of Liver X Receptors Agonist Promotes Atherosclerosis Regression. EBioMedicine [Internet]. 2017 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];28:225. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5835545/.

- Lin Y, Lin R, Lin H Bin, Shen S. Nanomedicine-based drug delivery strategies for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Med Drug Discov. 2024 Jun 1;22:100189.

- Artificial blood vessels could improve heart bypass outcomes | The University of Edinburgh [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.ed.ac.uk/news/2024/artificial-blood-vessels-could-improve-heart-bypas.

- Lang Z, Chen T, Zhu S, Wu X, Wu Y, Miao X, et al. Construction of vascular grafts based on tissue-engineered scaffolds. Mater Today Bio. 2024 Dec 1;29:101336.

- Ratner B. Vascular Grafts: Technology Success/Technology Failure. BME Front [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 4];4:0003. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10521696/.

- Pang ASR, Dinesh T, Pang NYL, Dinesh V, Pang KYL, Yong CL, et al. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems for the Targeted Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Molecules [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];29(12):2873. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11206617/.

- Shakya S, Shrestha A, Robinson S, Randall S, Mnatzaganian G, Brown H, et al. Global comparison of the economic costs of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2025 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Oct 6];15(1):e084917. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/15/1/e084917.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).