Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients and Clinical Characteristics

2.3. Coronary Angiographic Analysis

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

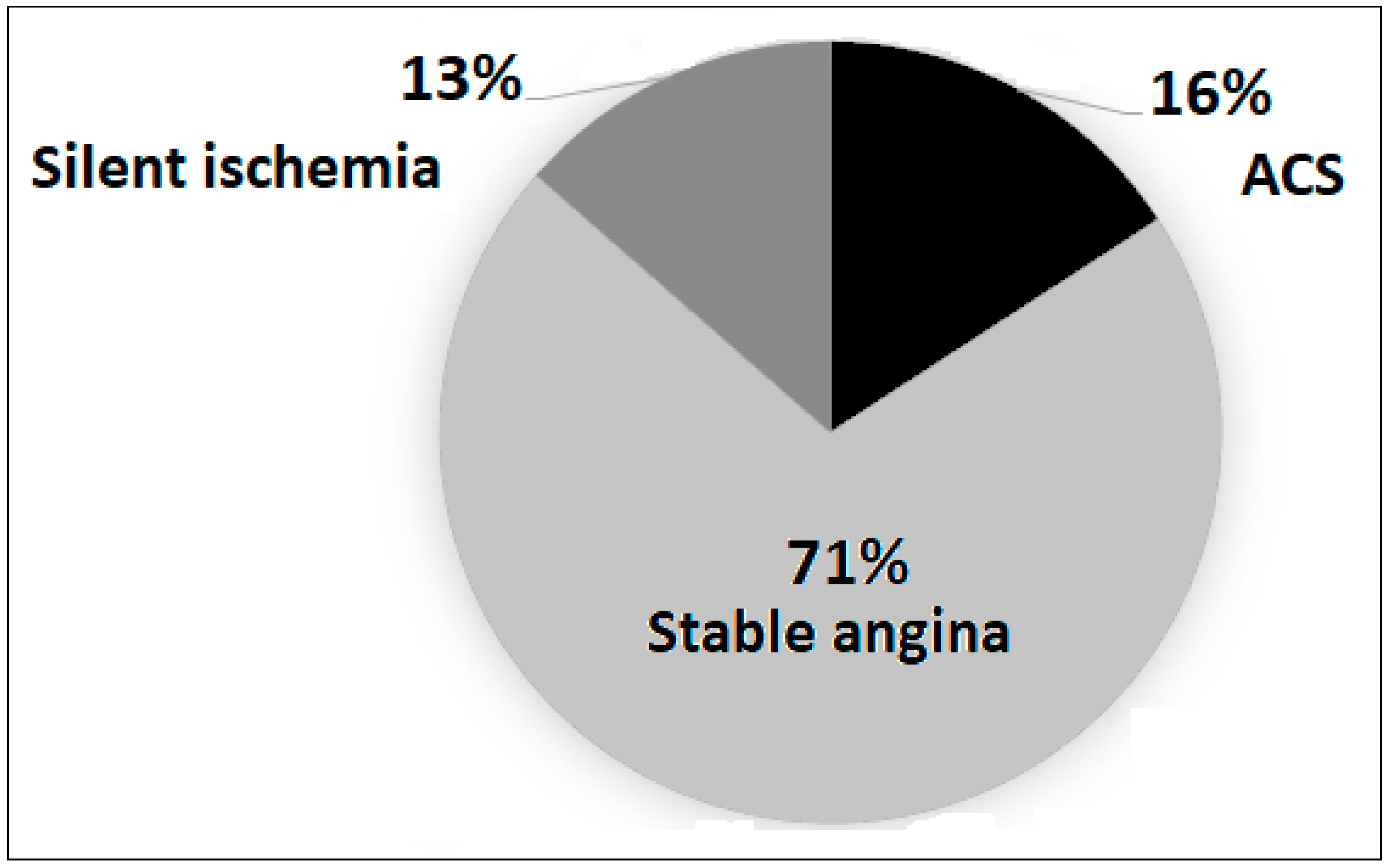

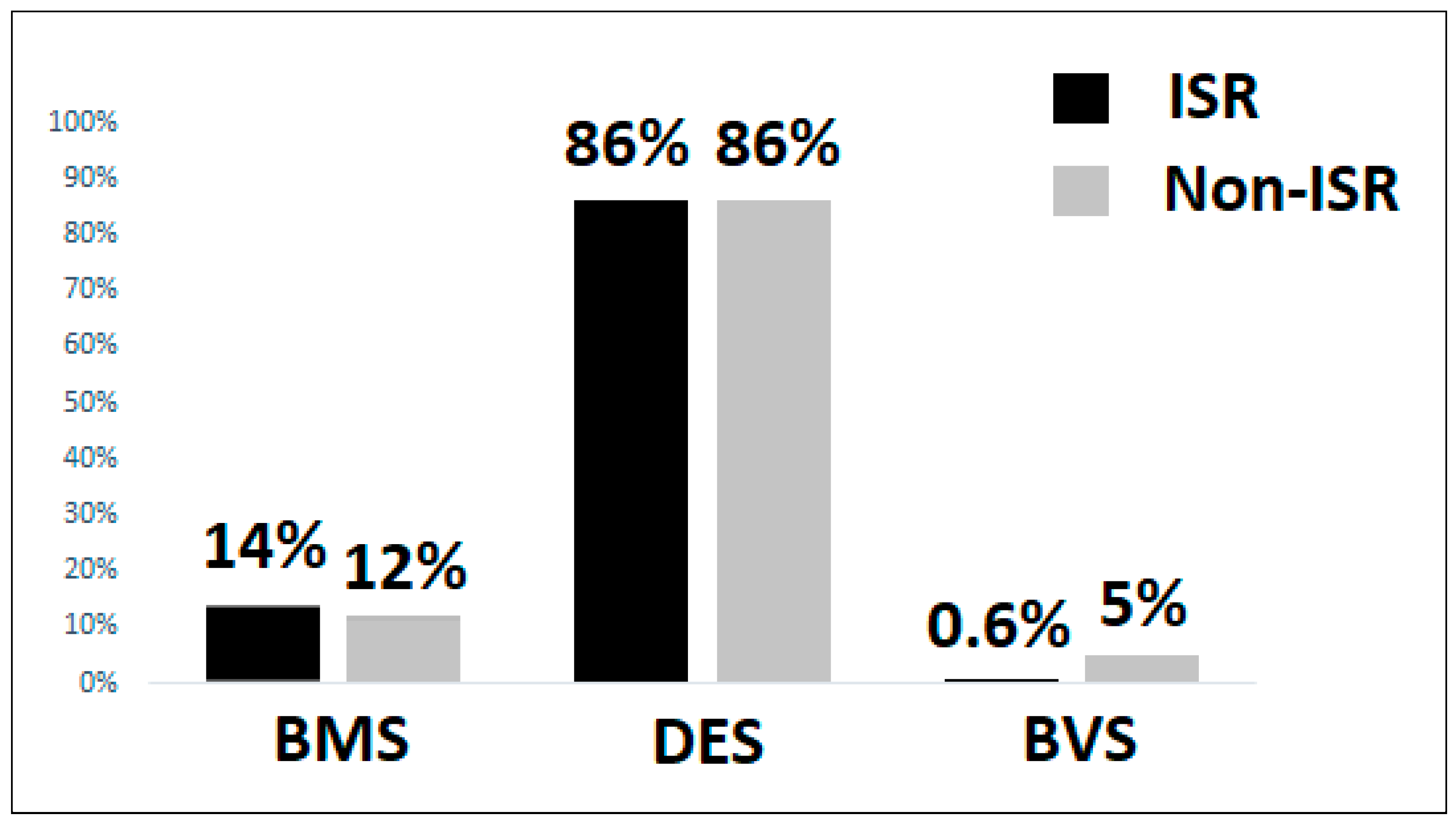

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Independent Clinical Predictors of Coronary ISR

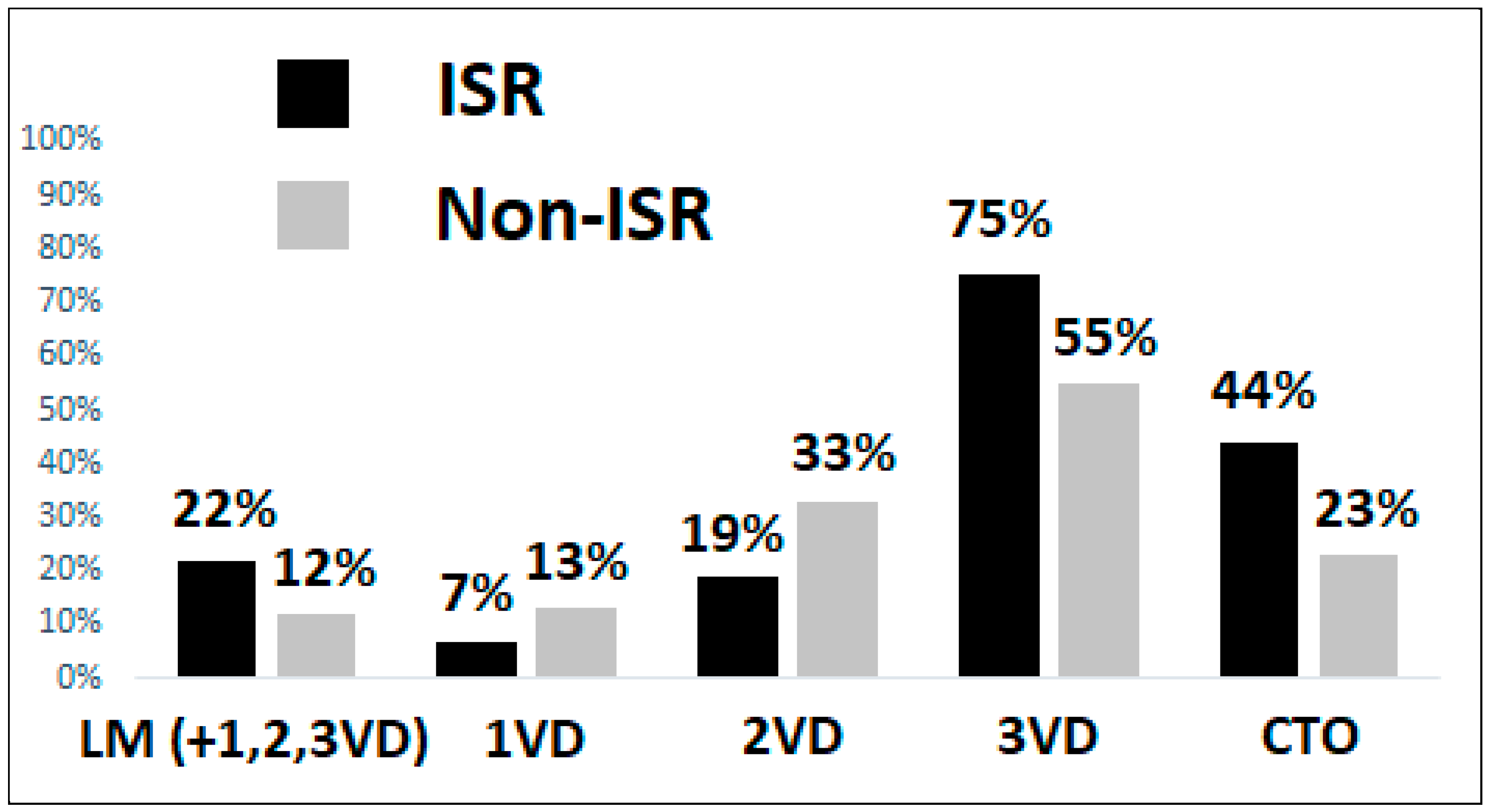

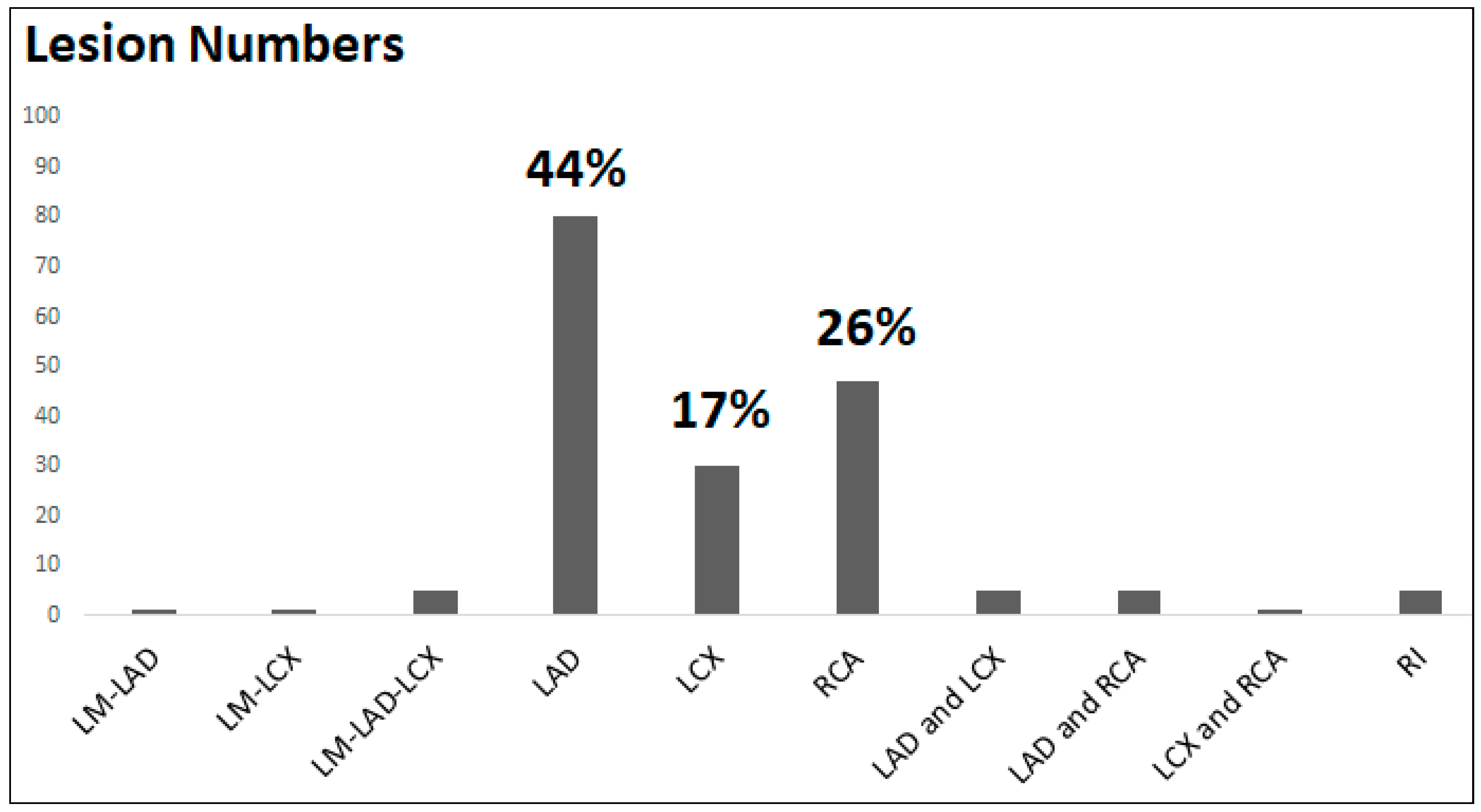

3.3. Coronary Angiography and Lesion Characteristics

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nobuyoshi M, Kimura T, Nosaka H et al, Restenosis after successful percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: serial angiographic follow-up of 229 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988, 12, 616–623. [CrossRef]

- Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, et al. A randomized comparison of coronarystent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1994, 331, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniwaki M, Stefanini GG, Silber S, et al. 4-Year clinical outcomes and predictors of repeat revascularization in patients treated with new-generation drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 63, 1617–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kereiakes DJ, Onuma Y, Serruys PW, et al. Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds for coronary revascularization. Circulation. 2016, 134, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangas GD, Claessen BE, Caixeta A, et al. In-stent restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 56, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes MA, Minha S, Chen F, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of coronary in-stent restenosis across 3-stent generations. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014, 7, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukema JW, Verschuren JJ, Ahmed TA, et al. Restenosis after PCI. Part 1: pathophysiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011, 9, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aoki J, Tanabe K. Mechanisms of drug-eluting stent restenosis. Cardiovasc Interv Ther.

- Zhang DM, Chen S. In-stent restenosis and a drug-coated balloon: insights from a clinical therapeutic strategy on coronary artery diseases. Cardiol Res Pract 2020, 20, 8104939. [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Gersh BJ, McClelland RL, et al. Clinical and angiographic predictors of restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Prevention of Restenosis with Tranilast and Its Outcomes (PRESTO) trial. Circulation 2004, 109, 2727–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne RA, Joner M, Kastrati A. Stent thrombosis and restenosis: what have we learned and where are we going? The Andreas Gruntzig Lecture ESC 2014. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 3320–3331.

- Cassese S, Byrne RA, Tada T, et al. Incidence and predictors of restenosis after coronary stenting in 10 004 patients with surveillance angiography. Heart 2014, 100, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama Y, Hirayama H, Ishii H, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on a re-percutaneous coronary intervention for sirolimus-eluting stent restenosis. Coron Artery Dis 2012, 23, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastrati A, Dibra A, Mehilli J, et al. Predictive factors of restenosis after coronary implantation of sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation 2006, 113, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang JL, Qin Z, Wang ZJ et al. New predictors of in-stent restenosis in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent. J Geriatr Cardiol 2018, 15, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Paramasivam G, Devasia T, Jayaram A, et al. In-stent restenosis of drug-eluting stents in patients with diabetes mellitus: clinical presentation, angiographic features, and outcomes. Anatol J Cardiol 2020, 23, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Her AY, Shin ES, Kim S, et al. Drug-coated balloon-based versus drug-eluting stent-only revascularization in patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori H, Torii S, Kutyna M, et al. Coronary artery calcificationand its progression: What does it really mean? J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2018, 11, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnak MJ, Amann K, Bangalore S, et al. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 74, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elezi S, Kastrati A, Pache J, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the clinical and angiographic outcome after coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998, 32, 1866–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozza JP Jr, Kuntz RE, Fishman RF, et al. Restenosis after arterial injury caused by coronary stenting in patients with diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 1993, 118, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanini GG, Holmes DR. Drug-eluting coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med 2013, 368, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo R, Bonaa KH, Efthimiou O, et al. Drug-eluting or bare-metal stents for percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2019, 393, 2503–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas S, Duffy SJ, Lefkovits J, et al. Australian trends in procedural characteristics and outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2018, 121, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymer JA, Harrison RW, Dai D, et al. Trends in bare-metal stent use in the united states in patients Aged >/=65 Years (from the CathPCI Registry). Am J Cardiol 2016, 118, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo A, Giannini F, Briguori C. Should we still have bare-metal stents available in our catheterization laboratory? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elezi S, Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, et al. Vessel size and long-term outcome after coronary stent placement. Circulation 1998, 98, 1875–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutlip DE, Chauhan MS, Baim DS, et al. Clinical restenosis after coronary stenting: perspectives from multicenter clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002, 40, 2082–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changal KH, Mir T, Khan S, et al. Drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in large coronary artery revascularization: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2021, 23, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice MC, Urban P, Greene S, et al. Why are we still using coronary bare-metal stents? J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61, 1122–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi I, Klersy C, Black AJ, et al. In-stent restenosis: long-term outcome and predictors of subsequent target lesion revascularization after repeat balloon angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000, 35, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen MS, John JM, Chew DP, et al. Bare metal stent restenosis is not a benign clinical entity. Am Heart J 2006, 151, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx SO, Totary-Jain H, Marks AR. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in restenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011, 4, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya J, Meyer CA, Timmins LH, et al. Effects of stent design parameters on normal artery wall mechanics. J Biomech Eng 2006, 128, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Qiao H, Wang R, et al. The characteristics and risk factors of in-stent restenosis in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: what can we do. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020, 20, 510. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | 1VD (n = 55) | 2VD(n = 144) | 3VD(n = 318) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.80 ± 11.28 | 68.10 ± 11.98 | 67.77 ± 10.78 | 0.762 |

| Gender (Male) | 39 (70.91) | 116 (80.56) | 270 (84.91) | 0.036 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.95 ± 3.79 | 25.94 ± 3.58 | 26.23 ± 3.62 | 0.685 |

| Underlying diseases | ||||

| HTN | 37 (67.27) | 115 (79.86) | 268 (84.28) | 0.010 |

| T2DM | 15 (27.27) | 60 (41.67) | 179 (56.29) | <0.001 |

| DLP | 35 (63.64) | 116 (80.56) | 229 (72.01) | 0.033 |

| PAOD | 1 (1.82) | 6 (4.17) | 15 (4.72) | 0.615 |

| CKD | 3 (5.45) | 10 (6.94) | 53 (16.67) | 0.003 |

| ESRD | 2 (3.64) | 5 (3.47) | 35 (11.01) | 0.010 |

| AF/AFL | 10 (18.18) | 17 (11.81) | 27 (8.49) | 0.078 |

| HFrEF | 5 (9.09) | 22 (15.28) | 47 (14.78) | 0.499 |

| History of CABG | 0 (0) | 2 (1.39) | 25 (7.86) | 0.002 |

| Medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 27 (49.09) | 99 (68.75) | 228 (71.70) | 0.003 |

| Clopidogrel | 21 (38.18) | 53 (36.81) | 158 (49.69) | 0.020 |

| Ticagrelor | 1 (1.82) | 5 (3.47) | 20 (6.29) | 0.030 |

| Prasugrel | 2 (3.64) | 5 (3.47) | 13 (4.09) | 0.946 |

| NOAC | 7 (12.73) | 9 (6.25) | 19 (5.97) | 0.176 |

| Statin | 35 (63.64) | 102 (70.83) | 235 (73.90) | 0.276 |

| ACEi /ARB | 17 (30.91) | 59 (40.97) | 133 (41.82) | 0.309 |

| Beta blockers | 30 (54.55) | 75 (52.08) | 180 (56.60) | 0.661 |

| ARNI | 0 (0) | 5 (3.47) | 13 (4.09) | 0.311 |

| Previous stent type | ||||

| BMS | 6 (10.91) | 17 (11.81) | 43 (31.52) | 0.797 |

| DES | 43 (78.18) | 120 (83.33) | 280 (88.05) | 0.099 |

| BVS | 6 (10.91) | 10 (6.94) | 1 (0.31) | - |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| ISR | 12 (21.82) | 33 (22.92) | 132 (41.51) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Model 1 | P value | Model 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | ||||

| Group of VD | 1VD (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2VD | 1.05 (0.49 – 2.24) | 0.889 | 1.04 (0.48 – 2.25) | 0.917 | |

| 3VD | 2.58 (1.30 – 5.13) | 0.006 | 2.34 (1.14 – 4.79) | 0.020 | |

| Variables | Model 3 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | |||

| Group of VD | 1VD (ref) | 1 | |

| 2VD | 0.96 (0.44 – 2.10) | 0.934 | |

| 3VD | 2.15 (1.03 – 4.46) | 0.039 | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.04) | 0.037 | |

| Gender | Female (ref) | 1 | |

| Male | 1.00 (0.59 – 1.71) | 0.976 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.99 (0.94 – 1.05) | 0.920 | |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| HTN | 0.68 (0.40 – 1.17) | 0.169 | |

| T2DM | 1.42 (0.93 – 2.16) | 0.100 | |

| DLP | 0.75 (0.47 – 1.21) | 0.254 | |

| PAOD | 1.42 (0.55 – 3.63) | 0.643 | |

| CKD | 0.91 (0.50 - 1.66) | 0.761 | |

| ESRD | 1.45 (0.68 – 3.08) | 0.328 | |

| AF/AFL | 1.53 (0.67 – 3.47) | 0.308 | |

| HFrEF | 1.28 (0.70 – 2.34) | 0.407 | |

| History of CABG | 1.69 (0.73 – 3.98) | 0.218 | |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 1.39 (0.87 – 2.23) | 0.165 | |

| Clopidogrel | 1.04 (0.67 – 1.62) | 0.838 | |

| Ticagrelor | 0.92 (0.37 – 2.30) | 0.867 | |

| Prasugrel | 0.80 (0.28 – 2.28) | 0.681 | |

| NOAC | 0.74 (0.26 – 2.06) | 0.565 | |

| Statin | 1.29 (0.80 – 2.07) | 0.288 | |

| ACEi /ARB | 1.03 (0.68 – 1.55) | 0.887 | |

| Beta blockers | 1.07 (0.72 – 1.60) | 0.707 | |

| ARNI | 0.69 (0.21 – 2.22) | 0.540 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).