1. Introduction

Globally, healthcare-associated communicable infectious diseases affect 100 million patients and 35 million of healthcare workers (HCWs) annually due mainly to poor adherence to infection prevention and control guidelines. According to the World health Organization (WHO), approximately 3 million of HCWs experience percutaneous exposure to bloodborne infectious agents such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), resulting in psychological stress associated health outcomes and socioeconomic loss [

1,

2,

3]. Accumulated evidences suggest that healthcare settings often play an important role in the spread of infection and epidemic amplification [

4]. Preparing for epidemic threats is a dynamic state requiring periodic capacity-building of healthcare workers (HCWs) and compliance with hospital infection prevention and control (HIPC) guidelines [

5].

WHO Central Africa remains one the most affected regions by emerging epidemics of communicable infectious diseases in the world. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), highly transmissible pathogens have spread throughout several provinces of this well-known epidemic-prone country. Between 2018 and 2020, DRC has faced major public health emergencies, with Ebola virus disease (EVD), Yellow fever, Measles, Cholera and Chikungunya outbreaks occurring concurrently. Regarding the spread of EVD in DRC, it has been reported that health settings in affected areas play a significant role in outbreak amplification. When a hospital infection occurs, it is susceptible to serve as the source of pathogen transmission to hospital personnel, inpatients and outpatients who might propagate the infection to other areas [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Furthermore, insufficient number of trained frontline HCWs, limited resource and inadequately equipped wards and the exhausted health system further increase the risk of outbreak occurrence [

10]. Previous works that explored hospital hygiene status have shown serious failings that might be associated with the high incidence of hospital infection among HCWs, particularly due to lack of compliance to occupational safety guidelines for HWCs [

11,

12,

13].

Previous works from our team and other researchers in the field have shown markedly high frequency of occupational percutaneous injury and blood and other body fluids (BBF) splash events in Congolese health settings. Among factors that exposed HCWs to such events, the absence of periodic training on infection prevention, limited provision of personal protective medical equipment (PPE), and the lack of use of safety engineered medical devices (SEDs) were the most prevalent [

11,

14,

15]. These factors increase the risk of hospital-acquired infection not only among healthcare personnel but also healthcare users.

Furthermore, unprepared HCWs, nurses in particular who are frontline healthcare service providers, combined with unsatisfactory working conditions, are likely to increase the risk of outbreak of communicable infectious diseases in DRC. This study aimed to assess occupational safety status and outbreak preparedness in Congolese nurses and laboratory technicians in Kongo central and Katanga area in DRC. We hypothesized that at least 50% of the participants would have sustained at least one percutaneous injury, BBF event or both in the previous 12-month period preceding this the implementation of this study, and that those events would affect their mental wellbeing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Sample Size Estimation

This was a multicenter analytical cross-sectional study conducted in five referral hospitals, including two university hospitals, between 2019-2020, amidst Ebola, Yellow fever, Cholera, and Chikungunya outbreaks. The study sites are located in two located in two provinces of DRC, Kongo central in the western area and Haut-Katanga in the southern area. They are among areas not affected by the longstanding eastern Congo armed conflict, involving regular armies of two neighbor countries, Rwanda and Uganda.

The study population comprised all nurses and medical laboratory technicians working full-time at each of the participating health settings. The single proportion formula was used to calculate the sample size of this study, with the assumption that 50% of participants comply with consistent use of personal protective medical equipment (PPE), as we previously reported [

16]. Thus, the expected sample size was 158 participants per province, for a total of 316 nurses and laboratory technicians for both Kongo central and Haut-Katanga provinces. Each participant was given an individually identifiable code used only for research purpose.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Recruitment of the participants was carried out by direct contact at their respective unit or department by hospital staff who served as survey facilitators based on the following criteria: being 18 years old or older, working full-time as a nurse or laboratory technician at the selected health setting, not having a part-time work at any other health setting. Each participant was given an individually identifiable unique number (code) that was solely used for research purpose.

2.3. Survey Questionnaire and Data Collection

A structured, self-administered questionnaire related to standard or universal precautions for infection prevention was used. It was divided into five sections:

(1) Sociodemographics; (2) Training and knowledge on Universal or standard Precautions (UP); (3) Exposure to accidental injury and skin contact with blood or other body fluid (BBF) in the hospital or health setting; (4) Compliance to preventive measures for occupationally-acquired infection; (5) Compliance to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) guidelines and mental health impact of occupational injury or BBF events.

In this study, primary outcome variables were (1) occupational percutaneous injury caused by needlestick or sharp medical devices, (2) skin exposure to blood or other body fluid (BBF) event. The secondary outcomes were the frequencies of post-exposure seropositive test results for HBV, HCV and HIV; however, sociodemographics and occupational characteristics of the respondents were considered as the covariates.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The present study used anonymous data collected from nurses (all categories from A0 to A2 grades) and laboratory technicians who voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey. Each questionnaire sheet had a serial number that was used during data transcription into a prepared excel file. A statement on informed consent (IC) was provided on the questionnaire. Thus, only workers who agreed with the IC statement answered the questions. The survey was part of the “Congo Communicable Diseases Research Project” that was approved by the Ethics committee of University of Lubumbashi School of Public Health, DRC (Approval number: UNILU/CEM/070/2016).

2.5. Data Analysis

Data related to categorical variables are expressed as proportions or percentages, those from continuous variables as means with their corresponding standard deviation (SD). For each item of the survey questionnaire, descriptive statistical tests were employed. Adherence to the standard precautions suggests that healthcare providers should execute the preventive measures at 100%; otherwise it would be considered a failure. Regarding questions related to the professional practices or medical procedures, a respondent was attributed 100% or 0% if he/she performed or not.

For comparison of the outcomes by categories of the respondents, chi-squared test or Fisher exact test was performed where appropriate. However, when outcomes were continuous variables, the Student’s t or Wilcoxon ranksum test was used after performing the normality test (Shapiro-Wilk). Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression models were constructed, with adjustments for age and gender, in order to identify the predictors of the outcome variables (accidental injury, BBF event and viral infection seropositivity) for which p-values were lower than 0.25 in the univariate analysis. Data analysis was performed with STATA software version 18 (StataCorp LLC, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Occupational Characteristics of the Respondents

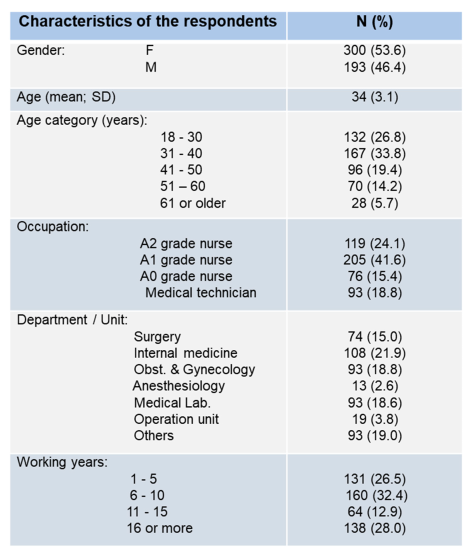

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. There were more female workers, 53.6% (300/493), as compared with their male counterparts. The majority of the respondents were middle aged workers (31-40 years; 33.8%) and A1 grade nurses (41.6%), and worked in the internal medicine departments (21.9%) of the participating healthcare settings, 21.9%. Furthermore, a greater proportion of the respondents have been working for 6-10 years (32.4%) either as a nurse or a medical laboratory technician.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of survey respondents.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of survey respondents.

3.2. Awareness, Outbreak Preparedness and Participation in Outbreak Response

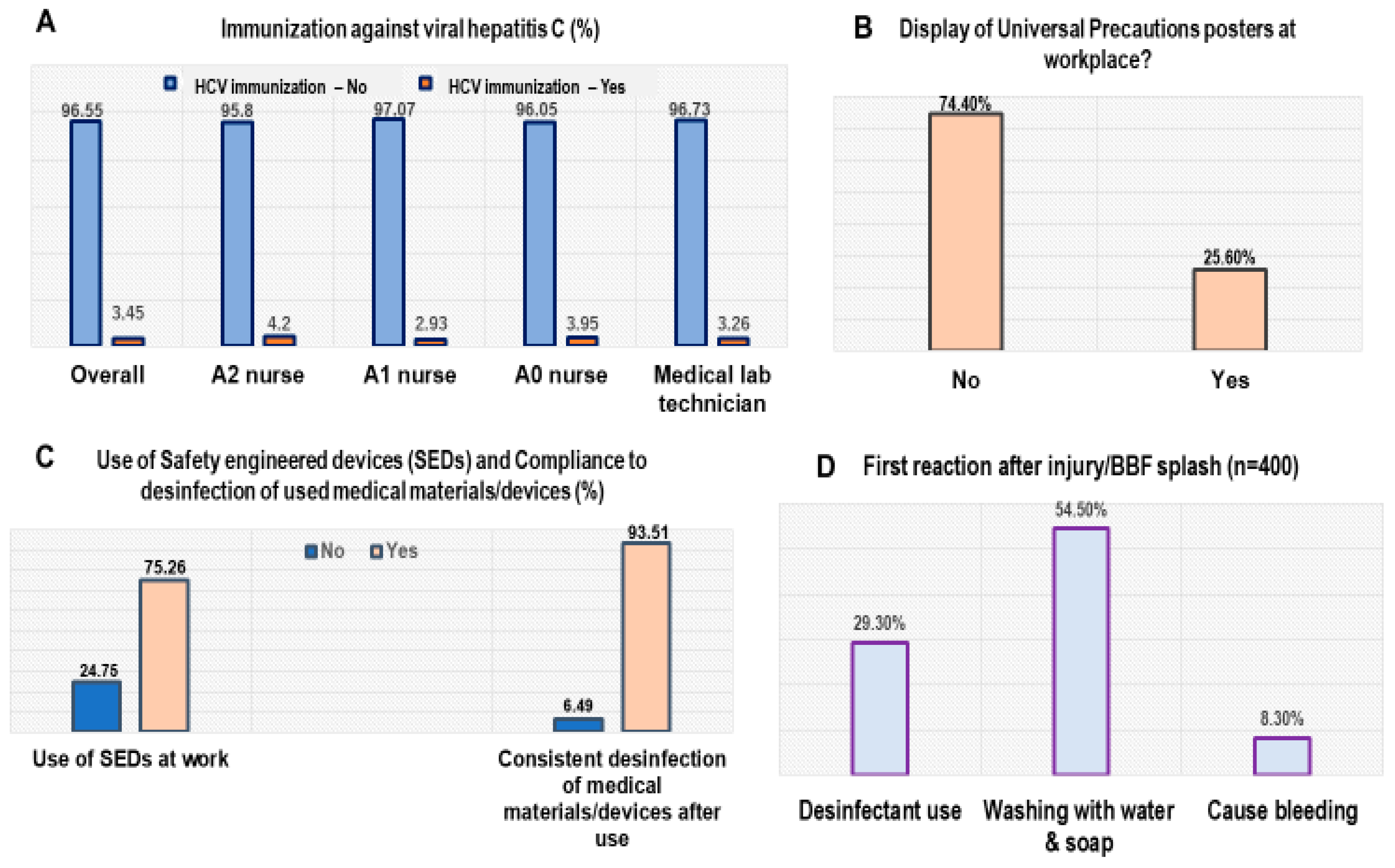

The proportion of the responders who have been immunized against VHC was extremely low, 3.45% (

Figure 1A); there were and 16.5% of the respondents immunized against VHB (not shown). Displaying posters at workplace or unit in the hospital that remind healthcare providers the safety guidelines related to standard precautions for infection prevention is a common practice. The majority of the survey responders, 74.4% (vs. 25.4%), had no such posters displayed at their workplaces (

Figure 1B). Additionally, 30.1% (vs. 69.9%) had never participated in training sessions related to occupational safety and standard precautions on infection prevention in their career (not shown). Higher proportions of the respondents used safety engineered medical devices (SEDs; 75.26%) consistently and disinfected medical materials and devices after use (93.51%) (

Figure 1C). Over 78% of the respondents used gloves consistently and the proportion of those wearing mask consistently was high, 92.2% (not shown). Regarding participation in outbreak response within the country, 24.5% and 12.2% the respondents have worked as Cholera and Chikungunya outbreak responders, respectively, whereas only 1.8% have served as Ebola outbreak responders. A large majority of the respondents (82.93%) have been recapping the needles after medical procedures (not shown).

3.3. Exposure to Hospital Infection Risk, Frequency of Percutaneous Injury and Blood/Body Fluid Splash Events, Post-Exposure Measures, Viral Hepatitis and HIV Testing and Mental Health Impact of Occupational Exposure to the Risk of Bloodborne Infection

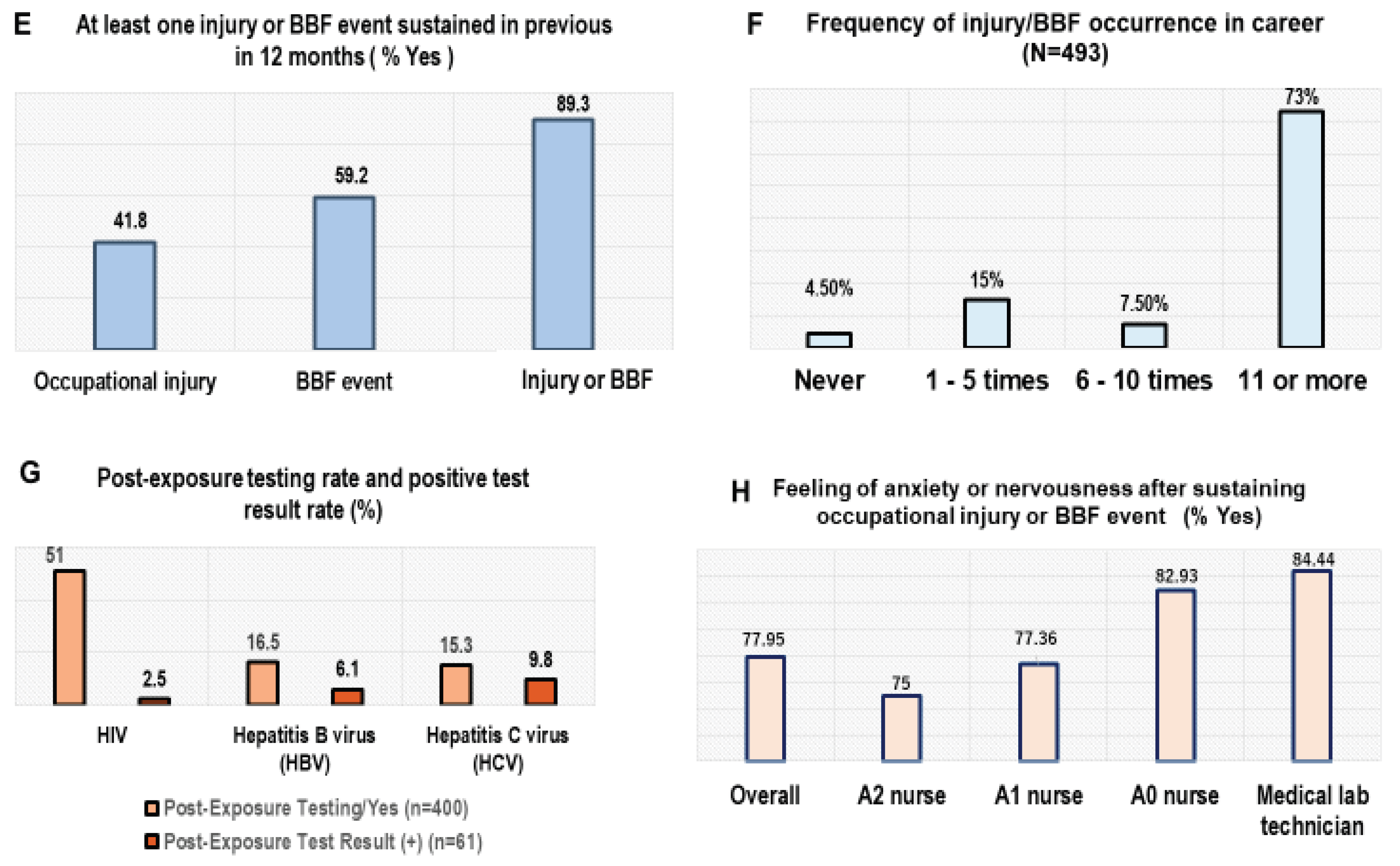

The occurrence of accidental injury with sharp and other medical devices and skin contact with contaminated body fluids are factors that increase the risk of hospital infection not only for healthcare providers, but also service users who visit the hospitals. This study showed extremely higher proportion of the respondents, 89.3%, who have sustained at least one injury, BBF event or both (41.8% for injury, 59.2% for BBF event) in the previous 12 months that preceded this survey (

Figure 1E). Most of those respondents reported multiple events occurring within a 12-month period, with 73% having sustained over 11 events (

Figure 1).

Of the respondents who sustained injury of BBF event at work, approximately half of them (54.5%) reported washing the exposed body area, whereas only 29.3% of them used a disinfectant or caused the exposed site to bleed (8.30%) (

Figure 1D). Moreover, medical laboratory technicians and A0 grade nurses were the most mentally affected responders by the occurrence of occupational injury and BBF events, 84.44% and 82.93% respectively, followed by A1 grade nurses, 77.36% (

Figure 1H). Overall, there were 51% of the responders who got tested for HIV, and the seropositivity rate was 2.5%. However, the proportions of the responders who have undergone VHB and VHC testing was markedly low, 16.5% and 15.3%, respectively; and the rates of positive tests were 6.1% and 9.8%, respectively (

Figure 1G).

3.4. Comparison of Frequency of Occupational Injury, Blood/Body Fluid Splash Event Occurrence, HIV and Viral Hepatitis Testing and Seropositivity

In order to compare the frequency of injury and BBF events occurrence according to occupational category of the responders, this variable was dichotomized; thereafter, we performed a comparison of the mean values of outcome variables related to nurses and medical laboratory technicians. It was observed that nurses had a higher frequency of injury and BBF events occurring in their career as compared with laboratory technicians, 3.56 (0.85) vs. 3.24 (1.09) (p=0.0011); post-exposure hepatitis C testing was more frequent among laboratory technicians than nurses, 1.29 (0.73) vs. 1.14 (0.35) (p=0.037), respectively, and similar result were observed for viral hepatitis B and HIV testing as shown in

Table 2. Furthermore, self-reported prevalence of VHC seropositivity [1.50 (1.37) vs. 1.11 (0.31); p=0.025], VHB seropositivity [1.44 (1.29) vs. 1.07 (0.25); p=0.019] and HIV seropositivity [1.17 (0.81) vs. 1.03 (0.17); p=0.023] were higher in medical laboratory workers as compared with nurses (

Table 2). Regarding medical procedures involved in the injury or BBF occurrence, injection accounted for 6.55% of the events, followed by blood transfusion, 4.79%, and surgical intervention, 4.79% (not shown).

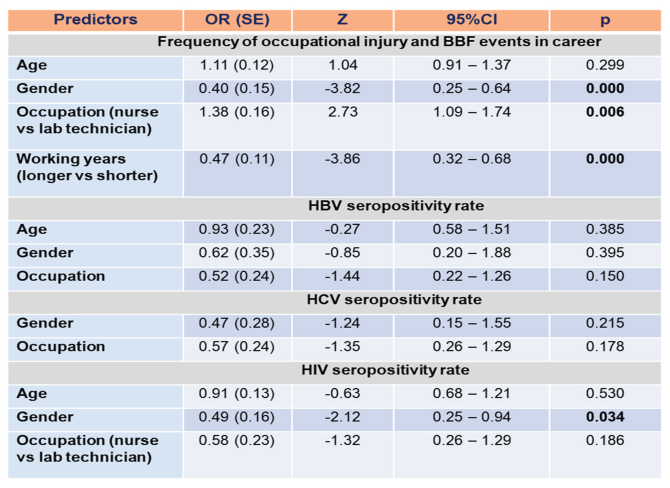

3.5. Predictors of the Outcomes by Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

Table 3 shows the result of the multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and gender, after dichotomization of the primary (occupational injury, BBF event) and secondary (post-exposure serological test result) outcome variables. It was observed that the frequency of work-related injury and BBF events occurring in the career of the respondents was associated with female gender [OR=0.40 (0.15), 95%CI: 0.25 – 0.64; p<0.001], and working years [OR=0.47 (0.11), 95%CI: 0.32 – 0.68; p<0.001], whereas it was positively associated with occupation [OR=1.38 (0.16), 95%CI: 1.09-1.74; p<0.01]. Furthermore, HIV seropositivity was inversely associated with gender [OR=0.49 (0.16), 95%CI: 0.25 – 0.94; p<0.005].

Table 3.

Predictors of events that increase risk of hospital infection.

Table 3.

Predictors of events that increase risk of hospital infection.

4. Discussion

This study explored the status of preparedness and the magnitude of percutaneous exposure to the risk of infection as well as the rate of seropositive test for viral infections among different categories of Congolese nurses and medical laboratory workers from five referral health settings. It was observed that over 95% of each category of the study participants were not immunized against common viral hepatitis. Additionally, though high proportions of the participants used SEDs and disinfected medical materials and devices after their utilization, it can be considered that both nurses and medical laboratory workers failed to adhere to the standard precautions given that not all of them underwent periodic training on infection prevention, used SEDs, consistently disinfected medical devices, and consistently used disinfectant or running water to wash the exposed body area while sustain percutaneous injury or BBF event.

Previous studies conducted in other African and Asian countries also showed poor adherence to infection prevention practice, in Lesotho, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana and Bangladesh [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Moreover, in our study, the proportion of the respondents who sustained at least either one percutaneous injury or BBF event or both in the previous 12 months was abnormally high, 89%. Recent studies conducted in Africa showed far lower rates of needlestick and sharp devices related occupational injuries among healthcare providers. An Ethiopian study that included 196 health professionals found approximately 19% of the participants sustaining such injuries [

25]. In addition, Laher and McDowal [

26] reported 26.3% incident injury caused by needlestick in a 12-month period amongst 240 prehospital emergency medical service personnel in a South African study.

Furthermore, male respondents, nurses and those with shorter working experience had higher odds of sustaining occupational injury by needle stick, sharp devices or BBF event, whereas male respondents had higher odds for having positive post-exposure HIV test result. We also observed a high proportion (78%) of the respondents who felt anxious or nervous in the aftermath of percutaneous injury or BBF occurrence. A study conducted in Lao PDR showed high score of anxiety and perceived psychological distress in healthcare providers who experienced needlestick and sharp injuries in the previous 6 months [

27]. This illustrates the importance strict adherence to infection prevention and control guidelines, reinforcement of related policies and the provision of psychological support for HCWs immediately after exposure.

5. Strengths and Limitations

The present study is the first investigation to explore the status of occupational safety, occupationally-acquired hospital infection and compare the infection risk between categories of a relatively large sample of Congolese nurses and laboratory technicians. It highlights the poor work safety and high risk for occupational infection these categories of HCWs in D.R. Congo. Nonetheless, infection rates reported in this work derive from self-reported hematological test results.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, findings from this study, which is the first to explore compliance to standard precautions and the magnitude of occupational injury and BBF in different nurse categories and medical laboratory staff serving in DRC, suggest that HCWs remain at high risk of occupationally-acquired infection and spread of outbreak of infectious diseases.

Funding

This study is part of the Congo Communicable Infectious Diseases Research project that has been supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No JP17H04675).

Informed Consent Statement

Each participant provided informed consent prior his/her enrollment in this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.N., S.K. and N.L.K.; Validation, D.K.T., G.B.M. and A.T.; formal analysis; N.R.N., K.K., TK, H.A.; data curation, H.S., C.O. and C.W.M.; resources, H.A., TK and A.N.; investigation, B.N.F., B.M.K. and N.M.K.; supervision, N.R.N. and N.L.K.; project administration, N.M., SK and N.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the version of the manuscript submitted to the journal.

Data Availability Statement

The study data can be accessed upon request to the corresponding author (N.R.N.).

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- ILO/WHO Joint ILO/WHO guidelines on health services and HIV/AIDS. International Labour Organization and World Health Organization, 2005. Available at: Joint ILO/WHO guidelines on health services and HIV/AIDS | International Labour Organization.

- Lee, J.H., Cho, J.H., Kim, Y.J. et al. Occupational blood exposures in health care workers: incidence, characteristics, and transmission of bloodborne pathogens in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 827.

- Babore. G.O., Eyesu, Y., Mengistu, D., Foga, S., Heliso, A.Z., Ashine, T.M. Adherence to infection prevention practice standard protocol and associated factors among healthcare workers. Glob. J. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 2024, 7(2), 50-58.

- Knight, G.M., Pham, T.M., Stimson, J. et al. The contribution of hospital-acquired infections to the COVID-19 epidemic in England in the first half of 2020. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 556.

- Lee, V.J., Aguilera, X., Heymann, D., Wilder-Smith, A. Lancet Infectious Disease Commission. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 20(1), 17-19.

- Nachega, J.B., Mbala-Kingebeni, P., Otshudiema, J., Zumla, A., Muyembe-Tamfun, J.J. The colliding epidemics of COVID-19, Ebola and measles in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 8(8), e991-992.

- Ilunga-Kalenga, O., Moeti, M., Sparrow, A., Nguyen, V.K., Lucey, D., Ghebreyesus, T.A. The ongoing Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018-2020. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 373-383.

- Muzembo, B.A., Ntontolo, N.P., Ngatu, R.N. et al. Local perspectives on Ebola during its tenth outbreak in DR Congo: a nationwide qualitative study. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0241120.

- Kasereka, M.C., Hawkes, M.T. The cat that kills people: community beliefs about Ebola origins and implications for disease control in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pathog. Glob. Health 2019, 113, 149-57.

- Kinghton, S.C., Richmond, M., Zabarsky, T., Dolansky, M., Rai, H., Donskey, C.J. Patients’ capacity, opportunity, motivation, and perception of inpatient and hygiene. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020, 48(2), 157-161.

- Ngatu, R.N., Phillips, E.K., Wembonyama, O.S., Yoshikawa, T., Jagger, J., Suganuma, N. Practice of universal precautions and risk of occupational blood-borne viral infection among Congolese healthcare workers. Am. J. Infect. Control 2012, 40, 68-70.

- Ngatu, R.N., Kayembe, N.J.M., Phillips, E.K. et al. Epidemiology of ebolavirus disease (EVD) and occupational EVD in healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa: necessity for strengthened public health preparedness. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 27, 455-461.

- Aruna, A., Mbala, P., Mukadi, D. et al. Ebola virus disease outbreak – Democratic Republic of the Congo, August 2018 – November 2019. Mrb. Mrtal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 1162-1165.

- Shindano, T.A., Horsmans, Y. Low level of awareness and prevention of hepatitis B among Congolese healthcare workers: urgent need for policy implementation. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1463455.

- Doshi, R.H., Hoff, N.A., Bratcher, A. et al. Risk factors for Ebola Exposure in Health Care Workers in Boende, Tshuapa Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 226(4), 608–615.

- Kabamba, M.N., Ngatu, R.N., Kabamba, L.N. et al. Occupational COVID-19 prevention among Congolese healthcare workers: knowledge, practices, PPE compliance, and safety imperatives. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020; 6(1), 6.

- Omisakin, F.D. Nurses’ practices towards prevention and control of nosocomial infections in Madonna University Teaching Hospital Elele Rivers State. Nurs. Primary Care 2018; 2: 1-7.

- Bhebhe, L.T., Van Rooyen, C., Steinberg, W.J. Attitudes, knowledge and practices of healthcare workers regarding occupational exposure of pulmonary tuberculosis. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2014, 6, E1–6.

- Yazie, T.D., Sharew, G.B., Abebe, W. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare professionals regarding infection prevention at Gondar University referral hospital, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 563.

- Desta, M., Ayenew, T., Sitotaw, N., Tegegne, N., Dires, M., Getie, M. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of infection prevention among healthcare workers in Debre Markos referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 465.

- Hussein, S., Estifanos, W.M., Melese, E.S., Moga, F.E. Knowledge, attitude and practice of infection prevention measures among health care workers in Wolaitta Sodo Otona teaching and referral hospital. J. Nurs. Care 2017, 6, 2167-1168.

- Kabir, A.A., Akhter, F., Sharmin, M. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of staff nurses on hospital acquired infections in tertiary care hospital of Dhaka city. North Int. Med. Coll. 2018, 10, 347-350.

- Ogoina, D., Pondei, K., Adetunji, B., Chima, G., Isichei, C., Gidado, S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of standard precautions of infection control by hospital workers in two tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. J. Infect. Prev. 2015, 16, 16-22.

- Gebresilassie, A., Kumei, A., Yemane, D. Standard precautions practice among health care workers in public health facilities of Mekelle special zone, Northern Ethiopia. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2014, 4, 286.

- Yosef, T., Asefa, A., Amsalu, H. et al. Occupational exposure to needle stick and sharp injuries and postexposure prophylaxis utilization among healthcare professionals in Southwest Ethiopia. Can J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 3792442.

- Laher, A.E., McDowall, J. Cross-sectional survey on occupational needle stick injuries amongst prehospital emergency medical service personnel in Johannesburg. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 9(4), 197-201.

- Matsubara, C., Sakisaka, K., Sychreun, V., Phensavanh, A., Ali, M. Anxiety and psychological impact associated with needle stick and sharp device injury among tertiary workers, Vientiane, Lao PDR. Ind. Health 2020, 58, 388-396.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).