1. Introduction

Autoinflammatory diseases (AID) constitute a group of rare, hereditary disorders characterized by dysregulation of the innate immune system, leading to chronic systemic inflammation [

1]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-1 (IL-1), play a pivotal role in driving inflammatory cascades that result in recurrent clinical manifestations such as fever, rash, arthralgia, and, notably, fatigue [

1,

2,

3]. The advent of IL-1–targeted therapies have revolutionized disease management, effectively controlled systemic inflammation and ameliorated many clinical features [

2,

4,

5].

Fatigue, however, has emerged as one of the most pervasive and disabling symptoms in AID. Unlike ordinary tiredness, it is severe, persistent, and disproportionate to exertion or rest, substantially impairing quality of life and daily functioning [

6]. Importantly, fatigue often persists even when systemic inflammation is adequately controlled by IL-1 blockade, suggesting that its aetiology is complex and extends beyond direct inflammatory activity [

7,

8]. This residual fatigue contributes to long-term disability and diminished productivity. It results in a considerable societal burden [

8].

In parallel, depressive symptoms have increasingly been recognized in patients with AID; they often remain underdiagnosed and undertreated. Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression, with cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α linked to altered mood regulation, neuroplasticity, and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function [

9]. Moreover, the psychosocial consequences of living with a chronic, unpredictable illness further heighten vulnerability to depression and other mental health disorders [

10]. Depression in this context not only worsens overall disease burden but also interferes with adherence, functional capacity, and quality of life [

7,

10,

11].

Despite the high prevalence of fatigue and depression in AID, their interrelationship has not been systematically examined to date. This knowledge gap hinders comprehensive patient management. It underscores the need for studies that characterize both symptoms, explore their correlation, and identify disease- and patient-related factors that contribute to their persistence.

Therefore, the aims of this study were: 1) To characterize fatigue and depression in a longitudinal cohort of paediatric and adult patients with AIDs on effective therapy including global measures of fatigue severity, 2) to compare overall fatigue and its domains and depression across diseases and 3) to identify modifiable risk factors associated with debilitating fatigue in patients with treated autoinflammatory diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

A single-centre cohort study of consecutive paediatric and adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of an autoinflammatory disease including CAPS and Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) between January 2007 and June 2024 was performed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) an established diagnosis of CAPS or FMF according to published criteria [

1,

4,

12]; 2) age ≥8 years at the last visit [

13] and 3) evidence of inactive disease either on or off treatment at the last follow-up visit [

14]. Patients with comorbidities known to be independently associated with fatigue, including diagnosed malignancies and mental health disorders, were excluded. All clinical and laboratory data were prospectively recorded in the institutional electronic registry (Arthritis and Rheumatism Database and Information System). Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, Eberhard Karls University of Tuebingen, and the University Hospital Tuebingen (Project Number: 070/2024BO2). All participants (or their legal guardians) provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

2.1. Data and Assessments

Patient- and disease-related variables included biological sex, ethnicity, age at symptom onset, at diagnosis, and at treatment start. Follow-up intervals were captured. Disease-associated clinical manifestations and phenotypes were recorded. Laboratory parameters comprised inflammatory markers, including serum amyloid A (SAA) and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as identified gene variants and their classification according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines [

15]. Therapy data were documented, including medication type, dosage, and administration frequency.

The baseline visit was defined as the initial patient assessment conducted prior to or at initiation of therapy; the last follow-up visit was defined as the final patient assessment during the study period. Disease duration was defined as the interval from symptom onset to the last clinical visit, and treatment delay as the interval from symptom onset to initiation of effective anti-inflammatory therapy. For the analysis, both timeframes were dichotomized into ≤10 years and >10 years.

2.2. Concepts, Definitions and Instruments

1)

Disease activity was assessed using validated instruments, including the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) and the Patient/Parent Global Assessment (PPGA), with both quantifying disease activity along a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 indicated no disease activity and 10 represented maximal disease activity. Categories of clinical disease activity were determined by PGA on a 10 cm VAS and categorised as mild (<2), moderate (2-4), and high (>4) as described previously (REF).

Complete remission was defined as PGA ≤ 2, with CRP ≤0.5 mg/dl and/or SAA ≤10 mg/l. Partial remission was PGA >2 and ≤5, with CRP >0.5 mg/dl but ≤3 mg/dl and/or SAA >10mg/l but ≤30 mg/l. Non-remission was defined as PGA >5, with CRP >3 mg/dl and/or SAA >30mg/l [

14].

2)

Fatigue was evaluated and quantified using two approaches: a) A 10 cm VAS embedded within the

PedsQL Present Functioning Visual Analogue Scales questionnaire [

16], which comprises six parameters, including fatigue, and is routinely completed by patients prior to their outpatient visit. A score of 0 indicated no fatigue, whereas a score of 10 indicated maximal fatigue. Fatigue was considered present if the VAS score was ≥1.

b) The

PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (MFS) [

17], an 18-item questionnaire comprising three subscales—General Fatigue, Sleep/Rest Fatigue, and Cognitive Fatigue—scored on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating lower fatigue and better functioning. For the statistical analyses, scores were reverse-transformed (100 – original score) so that higher values consistently reflected greater fatigue burden. The instrument has been validated for both child self-report (ages 5–18 years) and parent proxy-report (ages 2–18 years) [

17].

3)

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [

11] and its revised version, the CESD-R [

18]. Both are 20-item self-report questionnaires measuring depressive symptomatology in the general population. While the original CES-D employs a 0–3 scoring system, the CESD-R uses a 0–4 scale. In accordance with previously described and widely applied practice, responses scored as 4 on the CESD-R were recoded to 3 to facilitate comparability and simplify the assessment of clinical depression risk [

18]. A cut-off score of ≥16 was applied to define clinically relevant depressive symptoms [

19].

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome was overall fatigue as determined by the PedsQL-MFS at last follow-up. Secondary outcomes included 1) fatigue subdomain scores og General, Sleep/Rest and Cognitive Fatigue as determined by PedsQL-MFS, 2) fatigue score by VAS and 3) depression scores as measured by CES-D/CESD-R at the last follow-up visit.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median (minimum–maximum) and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Group comparisons used the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Paired baseline–last visit comparisons employed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlations were assessed using Spearman’s ρ for non-parametric and Pearson’s r for parametric data (|ρ|/|r| < 0.3 = weak, 0.3–0.5 = moderate, > 0.5 = strong). To identify independent determinants of fatigue, relevant variables including age group, pathogenicity of variants, disease duration, treatment delay, and depression risk were first tested in univariable analyses. Those showing significant associations were subsequently included in multivariable linear regression models. Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics v28.0.1.1, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 66 AID patients were included in the study, comprising 34 females (52%) and 32 males (48%). Thirty-nine patients (59%) were children, 27 (41%) were adults. The cohort consisted of 35 patients (53%) with CAPS and 31 (47%) with FMF. Genetic testing identified a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in 27 patients (41%), a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in 15 (23%), and no variant in 24 (36%). Fifty-two patients (79%) were of German and 14 (21%) of Turkish background.

3.2. Clinical Presentation

The median age at symptom onset was 4.0 years (range 0–20); it was 8.0 years (range 0–70) at diagnosis and treatment start, respectively. The median follow-up was 7.0 years (range 1–22). At the last follow-up, all patients met criteria for complete remission. A total of 61 patients (93%) were in complete remission on medication (CRM) and five (7%) in complete remission off medication (CR). Among treated patients, 25 (38%) were receiving colchicine, 32 (49%) canakinumab, and four (6%) anakinra (

Table 1).

In FMF patients (n=31), the most common findings were abdominal pain (97%) and febrile attacks (94%), followed by arthritis/arthralgia (48%), stress- or infection-triggered attacks (45%), myalgia (42%), headache (39%), irritability (36%), and lymphadenopathy (23%). All CAPS patients (n=35) had flares triggered by stress, cold, or infection. Urticarial rash (89%), arthralgia (74%), headache and conjunctivitis (71% respectively), myalgia and irritability (66% respectively) were frequently seen. Complications included hearing loss (40%), tinnitus (26%), amyloidosis and skeletal abnormalities (14%, respectively), and aseptic meningitis (6%).

3.3. Disease Activity

Across the total cohort, median PGA and PPGA scores at baseline were similar, with PGA scores at 4 (range 2–9) and PPGA at 4 (range 2–9), indicating moderate disease activity. Both measures dropped to 0 at the last visit, indicating inactive disease. Baseline VAS fatigue scores were significantly higher in CAPS compared with FMF patients (median 8.0, range 0–10 vs. median 5.0, range 4–7, p <0.001, see

Table 2). Adults showed a trend toward higher baseline PGA scores compared with children (median PGA 5 (range 3–9) vs. 3 (range 2–9), p = 0.08).

3.3.1. Fatigue

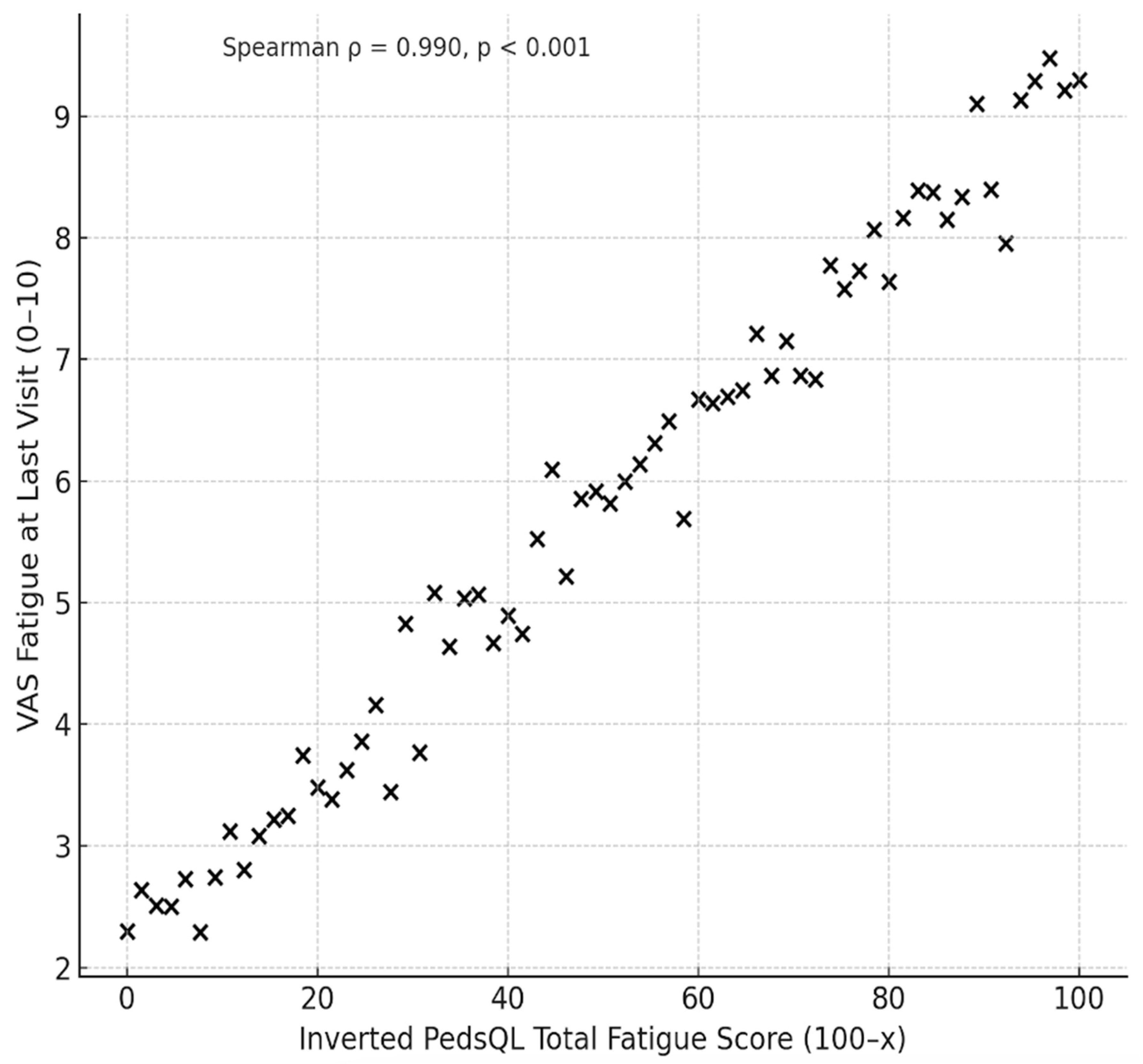

At baseline, overall fatigue as measured by VAS score, was found to be high (median 6). It remained in the high/moderate range at 4.5 despite well controlled disease activity at the last visit. The inverted PedsQL-MFS scores (100–x, established for consistency with VAS fatigue scores where higher scores indicate greater fatigue) were 45.8 (range 0-100) for General Fatigue, 41.6 (0-100) for Sleep/Rest Fatigue, 33.3 (0-91.6) for Cognitive Fatigue and 38.8 (0-91.6) for Overall Fatigue. All values were significantly higher than the general population (REF). A significant correlation between the inverted PedsQL Overall Fatigue Score (100–x) and VAS fatigue at the last visit was observed (Pearson’s r = 0.918, p < 0.001; Spearman’s ρ = 0.942, p < 0.001) (

Figure 1).

Comparing CAPS and FMF patients: Median inverted PedsQL-MFS scores in CAPS patients were 45.8 for General Fatigue, 41.6 for Sleep/Rest Fatigue, and 37.5 for Cognitive Fatigue, with an overall fatigue score of 40.2. Baseline VAS fatigue was high at 8 and remained elevated at 5 at the last visit. The FMF subgroup had a median inverted PedsQL-MFS score of 41.6 for General Fatigue, 45.8 for Sleep/Rest Fatigue, and 25.0 for Cognitive Fatigue, with an overall fatigue score of 36.1. Baseline fatigue VAS score was high at 5 and only minimally decreased to 4 at the last visit (

Table 2). CAPS patients had higher Cognitive Fatigue scores than FMF patients (37.5 vs. 25.0; p = 0.04). They also exhibited significantly higher baseline VAS fatigue scores (8 vs. 5; p < 0.001). No other significant between-group differences were observed (

Table 2).

3.3.2. Depression

The median CES-D/CESD-R depression score in the total cohort was elevated at 13 (0–50) with higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms and a greater overall risk of clinical depression. Subgroup analyses showed a median score of 14 (0–50) in CAPS and 12 (0–39) in FMF patients (p = 0.28) (

Table 2). Adults had slightly higher scores than children, with median values of 15 (0–42) versus 13 (0–45). This difference did not reach statistical significance (ρ = 0.244).

3.3.3. Risk Factors Associated with Increased Fatigue

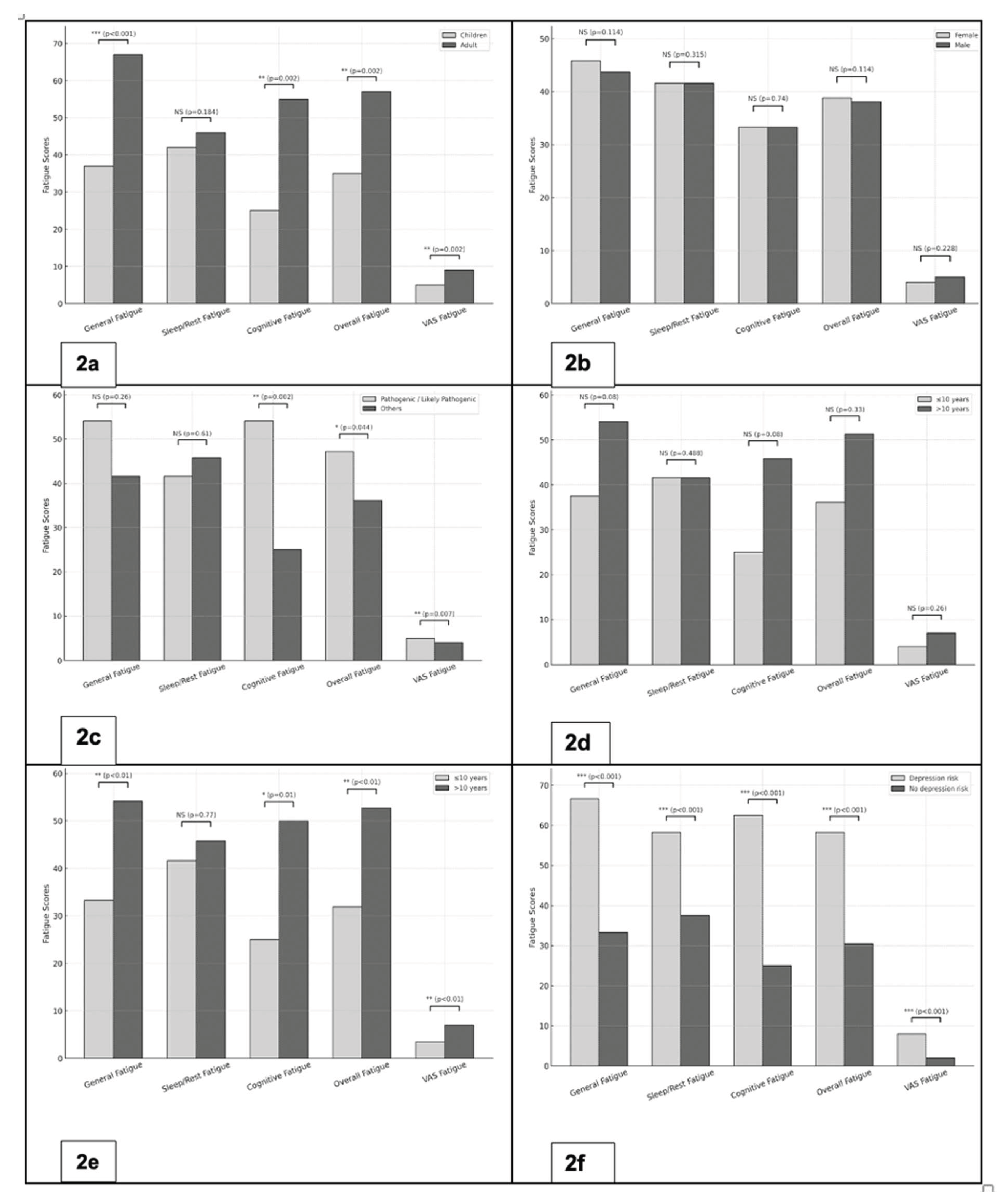

1) Age: Adults reported significantly higher fatigue scores across multiple domains compared to children. Median inverted PedsQL-MFS scores were 66.6 vs. 37.5 for General Fatigue (p < 0.001), 54.1 vs. 25.0 for Cognitive Fatigue (p = 0.002), and 56.9 vs. 34.7 for Overall Fatigue (p = 0.002). Similarly, the VAS fatigue was significantly higher among adults (median 7 vs. 4; p = 0.002) (

Figure 2a).

2) Biological sex: No significant differences in fatigue were observed. Median inverted PedsQL-MFS scores for General, sleep/rest, Cognitive, and overall Fatigue as well as fatigue VAS scores were comparable between females and males (

Figure 2b).

3) Pathogenicity of the gene variant: Patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants exhibited significantly higher levels of fatigue compared to those with other or no variants. Median inverted PedsQL-MFS scores were 54.1 vs. 25.0 for Cognitive Fatigue (p = 0.002) and 47.2 vs. 36.1 for Overall Fatigue (p = 0.044). VAS fatigue scores were also higher in the pathogenic/likely pathogenic group (median 5 vs. 4; p = 0.007) (

Figure 2c).

4) Delay to effective treatment: Patients with a treatment delay longer than 10 years tended to report higher fatigue levels. This trend was observed across PedsQL-MFS domains; particularly general and cognitive fatigue; as well as in VAS fatigue (

Figure 2d)

5) Disease duration: Patients with a disease duration of more than 10 years reported significantly higher fatigue scores. Median inverted PedsQL-MFS scores were 54.1 vs. 33.3 for General Fatigue (p < 0.01), 50.0 vs. 25.0 for Cognitive Fatigue (p = 0.01), and 52.7 vs. 31.9 for Overall Fatigue (p < 0.01). Correspondingly, the fatigue VAS scores were higher in the group with longer disease duration (median 7 vs. 3.5; p < 0.01) (

Figure 2e).

6) Depression: Overall, 27 of 66 patients (41%) met the threshold for high depression risk, defined as a CES-D/CESD-R score ≥16. Patients with high depression risk had markedly higher fatigue scores across all domains of the PedsQL-MFS compared with those without elevated depression risk. Median scores were 66.6 vs. 33.3 for General Fatigue, 58.3 vs. 37.5 for Sleep/Rest Fatigue, 62.5 vs. 25.0 for Cognitive Fatigue, and 58.3 vs. 30.5 for Overall Fatigue (all p < 0.001). Consistently, VAS fatigue scores were significantly higher in the high depression risk group (median 8 vs. 2; p < 0.001) (

Figure 2f).

3.3.4. Risk Model for Fatigue in Inactive AID

Depression consistently emerged as the strongest independent predictor of fatigue in multivariable regression analyses accounting for age group (adult vs child), pathogenicity of the gene variant, delay to effective treatment and disease duration. Depression risk was significantly associated with higher fatigue burden across all PedsQL domains and VAS fatigue (all p <0.001). Adult age was independently associated with greater cognitive fatigue (B=15.7, p=0.039) and disease duration showed a trend towards higher sleep/rest and general fatigue (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study provided a systematic evaluation of fatigue and depression in patients with inactive autoinflammatory diseases. Despite controlled disease activity fatigue scores were significantly elevated reflecting the ongoing burden. Importantly, disease specific impact on distinct fatigue domains such as cognitive fatigue in CAPS patients were documented. The demonstrated strong correlation between VAS fatigue and PedsQL-MFS highlights the clinical utility of both measures in capturing highly relevant patient-reported outcomes. Depression emerged as the strongest independent determinant of fatigue. Other putative risk factors such as age, disease duration, and pathogenic variants were found to be less relevant in well-controlled autoinflammatory disease. These findings underscore the need for a precision health approach that addresses fatigue as a distinct and clinically relevant burden in autoinflammatory diseases, beyond control of inflammatory disease activity, to prevent overtreatment and ensure optimal patient care.

Fatigue persisted in autoinflammatory diseases despite adequate disease control. Our findings demonstrating consistently higher levels of fatigue across all domains in inactive disease compared with general population [

20]. Distinct disease-related fatigue patterns were identified. CAPS patients reported significantly higher cognitive fatigue than those with FMF supporting a critical biological role of the central nervous system as disease target in CAPS—including aseptic meningitis, brain atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss [

2]— and contributing to attentional and memory-related impairment. Fatigue needs to be explored and addressed at all stages of disease including its distinct domains to enable targeted strategies through precision health approaches. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to adequately address fatigue in autoinflammatory diseases.

Depression emerged as the strongest independent determinant of fatigue in patients with inactive AID. Factors such as adult age, longer disease duration and pathogenic variants were also found to be associated with higher fatigue in univariable analyses, however their explanatory power diminished in multivariable models. Meta-analyses in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus have demonstrated a high prevalence of depression and strong associations with greater fatigue, impaired quality of life, and reduced adherence to therapy [

7,

21,

22]. While an inflammatory etiology of depression has been proposed [

9], depression in inactive inflammation remains poorly understood. In pediatric cohorts, depression and fatigue often remain underdiagnosed; nevertheless, their presence strongly predicted impaired school attendance, reduced social participation, and adverse developmental outcomes [

8]. Our findings support depression being an important mechanistic driver of fatigue even independent of disease activity in autoinflammatory disease. This creates important opportunities to optimize care by addressing modifiable psychological factors.

There were several limitations to this study. The small sample size from a single center limits its generalizability. Socioeconomic factors and life circumstances, as well as their impact, were not fully captured; however, the data reflect a real-life cohort within a generally well-supported health and social care system in Germany. In addition, a contemporaneous healthy control group was lacking, however large normative population data for the PedsQL-MFS [

20] provided validated comparators.

5. Conclusions

Fatigue is a key symptom of active and inactive autoinflammatory disease, significantly contributing to its individual and societal burden. Depression was found to be the strongest risk factor for debilitating fatigue in patients with inactive disease. There is an urgent need for diagnostic and therapeutic precision health approaches to depression and fatigue when caring for children and adults living with autoinflammatory diseases. These data emphasize the urgent need of systematic screening and integrated approaches targeting both inflammatory and psychological domains of disease.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the work as follows: Conceptualization: Y.S., Ö.S., S.M.B., and J.B.K.-D.; Methodology: Y.S., Ö.S., S.M.B., and J.B.K.-D.; Formal analysis: Y.S. and J.B.K.-D.; Writing—original draft preparation: Y.S.; Review and Editing: Ö.S., S.M.B., and J.B.K.-D. Each author made substantial contributions to the manuscript and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Infrastructural support was provided by the participating centers. No other specific funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Karl Eberhard University Tuebingen (Project Number: 070/2024BO2).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the local ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request and with obtained ethical approval, the dataset can be made available by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Tübingen.

Competing Interests

J.B.K.-D. has received research grants and speaker’s fees from Novartis and SOBI. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Gattorno, M., et al., Classification criteria for autoinflammatory recurrent fevers. Ann Rheum Dis, 2019. 78(8): p. 1025-1032.

- Welzel, T. and J.B. Kuemmerle-Deschner, Diagnosis and Management of the Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes (CAPS): What Do We Know Today? J Clin Med, 2021. 10(1).

- Cardona Gloria, Y. and A.N.R. Weber, Inflammasome Activation in Human Macrophages: IL-1beta Cleavage Detection by Fully Automated Capillary-Based Immunoassay. Methods Mol Biol, 2023. 2696: p. 239-256.

- Ozen, S., et al., EULAR recommendations for the management of familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis, 2016. 75(4): p. 644-51.

- Kone-Paut, I., et al., Use of the Auto-inflammatory Disease Activity Index to monitor disease activity in patients with colchicine-resistant Familial Mediterranean Fever, Mevalonate Kinase Deficiency, and TRAPS treated with canakinumab. Joint Bone Spine, 2022. 89(6): p. 105448.

- Duruoz, M.T., et al., Fatigue in familial Mediterranean fever and its relations with other clinical parameters. Rheumatol Int, 2018. 38(1): p. 75-81.

- Gouda, W., et al., Sleep disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with quality of life, fatigue, depression levels, functional disability, disease duration, and activity: a multicentre cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res, 2023. 51(10): p. 3000605231204477.

- Özlem Satirer, Y.S., Anne-Kathrin Gellner, Susanne M. Benseler, Jasmin B. Kuemmerle-Deschner Burden of fatigue in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. EULAR Rheumatology Open, 2025.

- Dantzer, R., et al., From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2008. 9(1): p. 46-56.

- Tsuboi, H., et al., Validation of the Japanese Version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised: A Preliminary Analysis. Behav Sci (Basel), 2021. 11(8).

- Siddaway, A.P., A.M. Wood, and P.J. Taylor, The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale measures a continuum from well-being to depression: Testing two key predictions of positive clinical psychology. J Affect Disord, 2017. 213: p. 180-186.

- Kuemmerle-Deschner, J.B., et al., Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis, 2017. 76(6): p. 942-947.

- Faulstich, M.E., et al., Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). Am J Psychiatry, 1986. 143(8): p. 1024-7.

- Lachmann, H.J., et al., Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(23): p. 2416-25.

- Richards, S., et al., Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med, 2015. 17(5): p. 405-24.

- Sherman, S.A., et al., The PedsQL Present Functioning Visual Analogue Scales: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2006. 4: p. 75.

- Panepinto, J.A., et al., PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in sickle cell disease: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2014. 61(1): p. 171-7.

- Eaton, W.W., Smith, C., Ybarra, M., Muntaner, C., & Tien, A., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R). In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults L.E.A. Publishers., Editor. 2004.

- Lewinsohn, P.M., et al., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging, 1997. 12(2): p. 277-87.

- Haverman, L., et al., Psychometric properties and Dutch norm data of the PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale for Young Adults. Qual Life Res, 2014. 23(10): p. 2841-7.

- Fonseca, R., et al., Silent Burdens in Disease: Fatigue and Depression in SLE. Autoimmune Dis, 2014. 2014: p. 790724.

- Kawada, T., The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2014. 53(3): p. 578.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).