Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

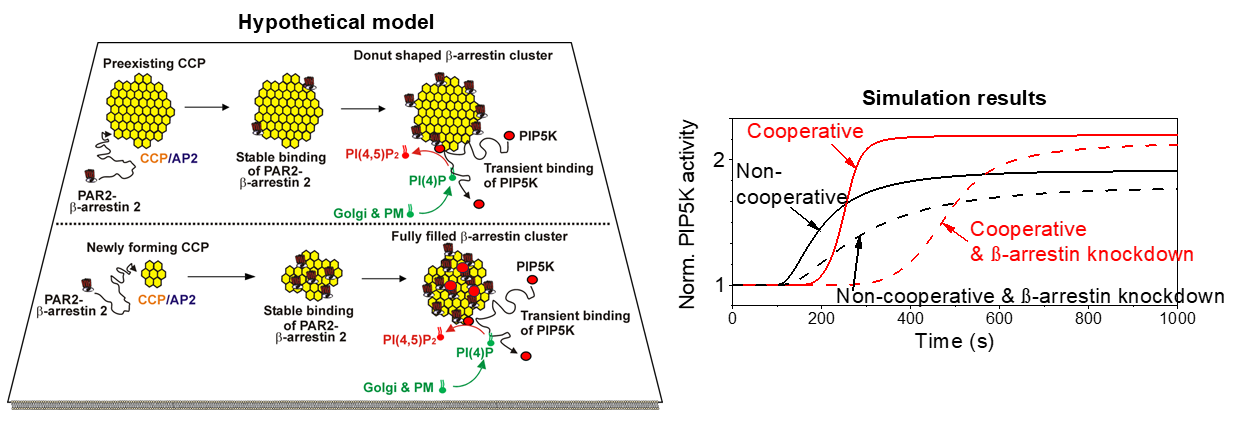

2.1. Model Overview

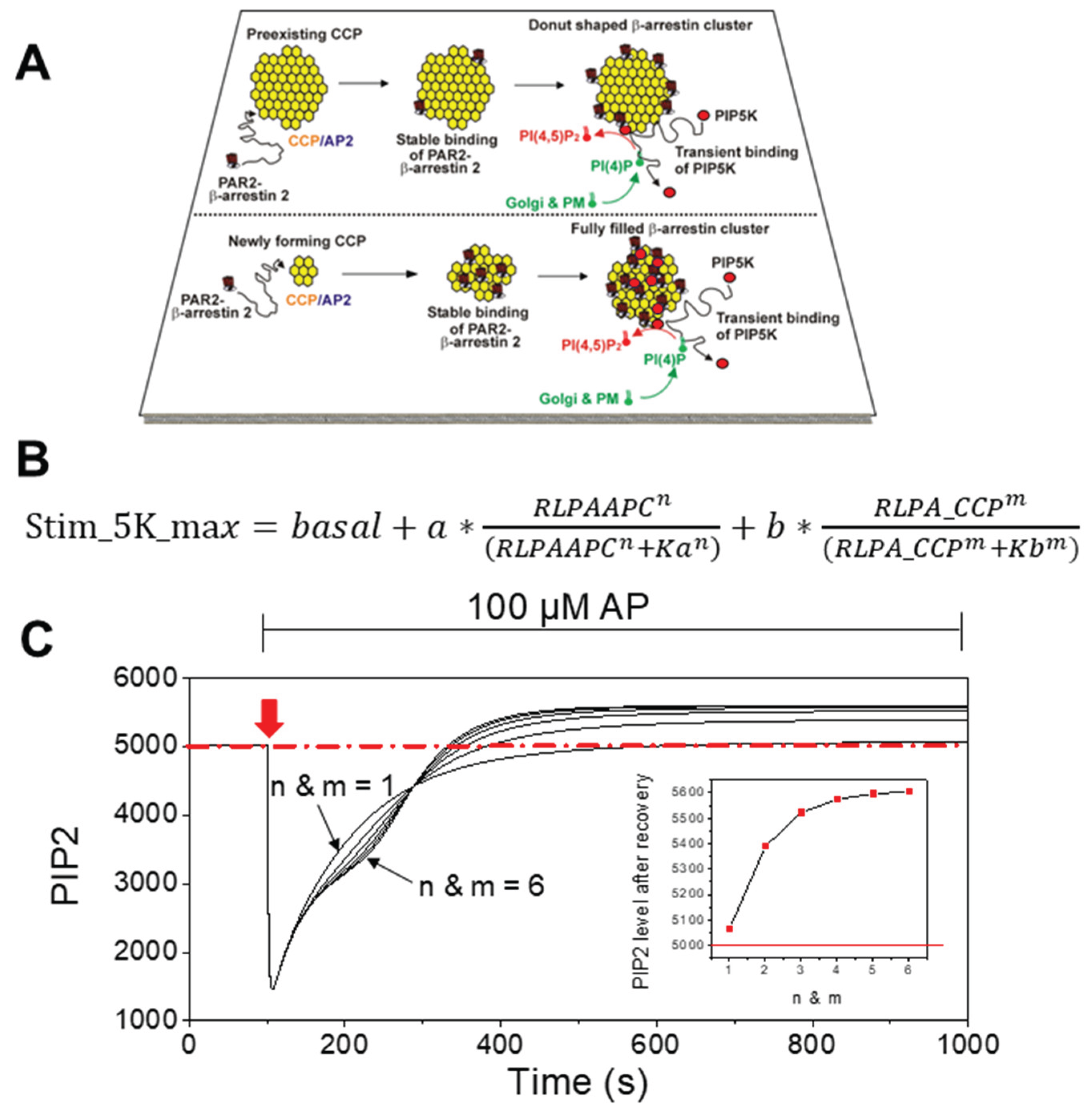

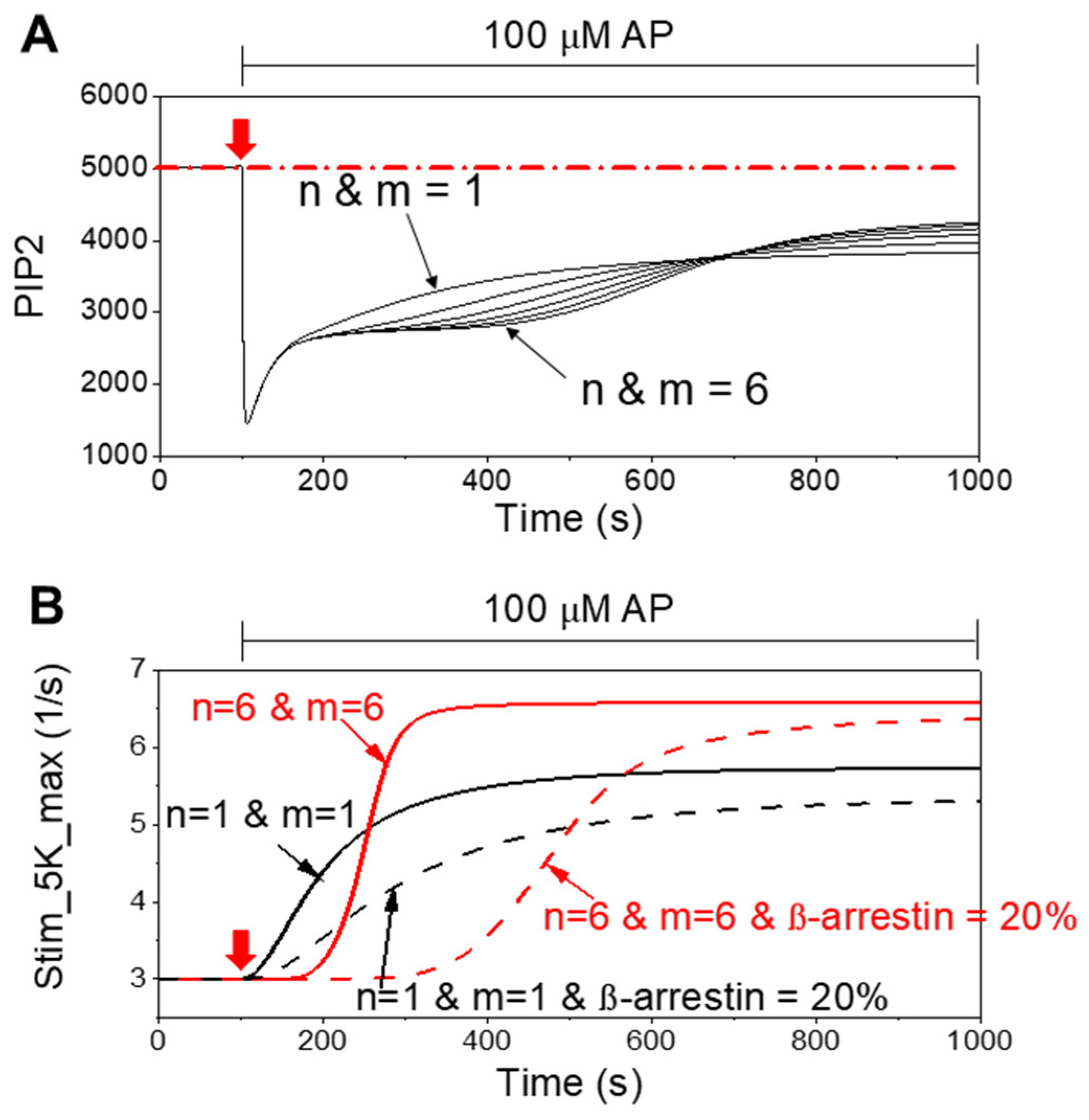

2.2. Mathematical Formulation

2.3. Parameter Selection

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Cooperative PIP5K Activation as the Key Regulatory Principle

4.2. Functional Difference Between Newly Forming and Preexisting CCPs

4.3. Broader Implications of Transient and Weak Interactions

4.4. Potential Crosstalk of PAR2–PIP2–PIP5K Signaling with Oncogenic KRAS

4.5. Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIP5K | Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) |

References

- Krauss, M.; Haucke, V. Phosphoinositide-metabolizing enzymes at the interface between membrane traffic and cell signalling. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8(3), 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, G.; De Camilli, P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 2006, 443 (7112), 651–657. [CrossRef]

- Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93(3), 1019–1137. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Marsland III, R.; Upadhyayula, S.; Song, E.; Dand, S.; Capraro, B.R.; Wang, W.; Skillern, W.; Gaudin, R.; Ma, M.; Kirchhausen, T. Dynamics of phosphoinositide conversion in clathrin-mediated endocytic traffic. Nature 2017, 552 (7685), 410–414. [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, M.; Roux, A. Mechanisms of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19 (5), 313–326. [CrossRef]

- Zoncu, R.; Perera, R.M.; Sebastian, R.; Nakatsu, F.; Chen, H.; Balla, T.; Ayala, G.; Toomre, D.; De Camilli, P. Loss of endocytic clathrin-coated pits upon acute depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc. of the Natl. Acad. of Sci. USA 2007, 104 (10), 3793–3798. [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, T.P.; Ahn, S.; Meyer, T. Receptor-induced transient reduction of plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr. Biol. 1998, 8(6), 343–346. [CrossRef]

- Antonescu, C.N.; Aguet, F.; Danuser, G.; Schmid, S.L. Phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate regulates clathrin-coated pit initiation, stabilization, and size. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22(14), 2588–2600. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, K.L.; Premont, R.T.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 639–650. [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, R.J. Historical review: A brief history and personal retrospective of seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends in Pharmacol. Sci. 2004, 25(8), 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Czech, M.P. PIP2 and PIP3: Complex roles at the cell surface. Cell 2000, 100(6), 603–606. [CrossRef]

- Naslavsky, N.; Weigert, R.; Donaldson, J.G. Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15(2), 444–455. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, G.J.; McMahon, H.T. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 857–902. [CrossRef]

- von Zastrow, M.; Sorkin, A. Mechanism for regulating and organizing receptor signaling by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 709-737. [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, B.E.; Melero, C.; Temkin, P.; Lei, C.; Hong, W.; Kortemme, T.; von Zastrow, M. SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190(4), 565-574. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S.K.; Lefkowitz, R.J. β-arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32(9), 521–533. [CrossRef]

- Nuber, S.; Zabel, U.; Lorenz, K.; Nuber, A.; Milligan, G.; Tobin, A.B.; Lohse, M.J.; Hoffmann, C. β-arrestin biosensors reveal a rapid, receptor-dependent activation/deactivation cycle. Nature 2016, 531(7596), 661–664. [CrossRef]

- Sungkaworn, T.; Jobin, M.-L.; Burnecki, K.; Weron, A.; Lohse, M.J.; Calebiro, D. Single-molecule imaging reveals receptor–G protein interactions at the plasma membrane. Nature 2017, 550(7677), 543–547. [CrossRef]

- Eichel, K.; Jullié, D.; von Zastrow, M. β-arrestin drives MAP kinase signalling from clathrin-coated structures after GPCR dissociation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18(3), 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-R.; Seo, J.B.; Deng, Y.; Asbury, C.L.; Hille, B.; Koh, D.S. Contributions of protein kinases and β-arrestin to termination of protease-activated receptor 2 signaling. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 147(3), 255-271. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-R.; Jiang, Y.; Seo, J.B.; Chiu, T.; Hille, B; Koh, D.-S. β-arrestin-dependent PI(4,5)P2 synthesis boosts GPCR endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118(17), e20111023118. [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.K.; Cullati, S.N.; Activation is only the beginning: mechanisms that tune kinase substrate specificity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2025, BST20241420. [CrossRef]

- Hoeflich, K.P.; Ikura, M.; Calmodulin in action: Diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell 2002, 108(6):739-742. [CrossRef]

- Boire, A.; Covic, L.; Agarwal, A.; Jacques, S.; Sherifi, S.; Kuliopulos, A. PAR1 is a matrix metalloprotease-1 receptor that promotes invasion and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cell 2005, 11, 748–754. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gangadharan, B.; Brass, L.F.; Ruf, W.; Mueller, B.M. Protease-activated receptors (PAR1 and PAR2) contribute to tumor cell motility and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004, 2(7), 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Prakash, P.; Liang, H.; Cho, K.J.; Gorfe, A.A.; Hancock, J.F. Lipid-sorting specificity encoded in K-Ras membrane anchor regulates signal output. Cell 2017, 168:239-251.e16. [CrossRef]

- Eser, S.; Reiff, N.; Messer, M.; et al. Selective requirement of PI3K/PDK1 signaling for KRAS oncogene-driven pancreatic cell plasticity and cancer. Cancer Cell 2013, 23(3),193–206. [CrossRef]

- Fruman, D.A.; Chiu, H.; Hopkins, B.D.; Bagrodia, S.; Cantley, L.C.; Abraham, R.T. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell 2017, 605–635. [CrossRef]

| Species/constants | Value | Rationale |

| R for PAR2 | 5,000 µm-2 | Receptor density [20]. If the receptors were able to dissolve in cytosol, it would be 5 µM. |

| G (G-protein) | 40 µm-2 | Number of free G-protein at the plasma membrane |

| PLC | 10 µm-2 | Number of free PLC at the plasma membrane |

| PI | 140,000 µm-2 | Number of free PI at the plasma membrane |

| PIP | 3,600 µm-2 | Number free PIP at the plasma membrane |

| PIP2 | 5,000 µm-2 | Number of free PIP2 at the plasma membrane |

| IP3 | 0.015 µM | IP3 at cytosol before receptor activation: Steady state balance from PLC and IP3ase |

| DAG at PM | 23 µm-2 | Number of DAG at the plasma membrane before receptor activation |

| β-arrestin (cytosol) = β-arrestin1+β-arrestin2 |

15 µM | β-arrestin 1 (Arrestin 1) and β-arrestin 2 (Arrestin 2) have 7.5 µM, respectively, to leave proper amount β-arrestins in the cytosol after their binding to the PAR2 at the plasma membrane. |

| PKC_cyto (PKC Cytosol) | 1 µM | The concentration was chosen to make reasonable fitting of DAG bound PKC |

| GRK | 600 | Fixed value to similar to the peak value of PKC_DAG |

| Weighting_factor_PKC_DAG or Weighting_factor_GRK |

0.5 | Active PKC (PKC_DAG) gives the same contribution to phosphorylation of ligand bound receptor as GRK. |

| kf_PKC_DAG | 0.02 µM-1*s-1 | Forward rate constant for binding of PKC and DAG |

| Kr_PKC_DAG | 0.06 s-1 | Reverse rate constant for dissociation of DAG from PKC, giving Kd = 3 µM |

| Ca2+ (cytosol) | 0.13 µM | Typical intracellular Ca2+ level is 0.1-0.2 µM |

| foldPIP2 | 3 | Making the size of the total PIP2 (bound plus free) 3 times the free pool |

| k_4K (basal) | 0.00078 s-1 | FoldPIP2*0.00026 s-1 |

| k_5K (basal) | 0.06 s-1 | FoldPIP2*0.02 s-1 |

| k_4K (stimulated) | 6* k_4K (basal) | To fit the recovery kinetics of PIP2 probe |

| k_5K (stimulated) | 3* k_5K (basal) | To fit the recovery kinetics of PIP2 probe |

| k_4P (basal) | 0.03 s-1 | 0.03 s-1*k4r_basal (k4r_basal = 1) |

| k_5P (basal) | 0.014 s-1 | 0.014 s-1*k5r_basal (k5r_basal = 1) |

| k_4P (stimulated) | 0.19 s-1 | 0.03 s-1*k4r_stim (k4r_stim = 6.25) |

| k_5P (stimulated) | 0.042 s-1 | 0.014 s-1*k5r_stim (k5r_stim = 3) |

| kf_RL | 0.75 µm2*molecules-1*s-1 | Rate constant for phosphorylation of ligand-bound receptor |

| kr_RLP | 0.0125 s-1 | Rate constant for dephosphorylation of ligand-bound phosphorylated receptor |

| kf_R (basal) | 0.0001 s-1 | Basal phosphorylation rate constant of receptor |

| kr_RP (basal) | 2 s-1 | Basal dephosphorylation rate constant of phosphorylated receptor |

| kf_R (stimulated) | 10 s-1 | Stimulated phosphorylation rate constant of receptor |

| kr_RP (stimulated) | 4 s-1 | Stimulated dephosphorylation rate constant of receptor. We assumed that rate of dephosphorylation of RP doubles after ligand treatment |

| kf_L2 | 0.09333 µM-1*s-1 | Binding rate constant of ligand to RP, depending on the dissociation constant (K_L2) and dissociation rate constant (kr_L2) |

| kr_L2 | 5.6 s-1 | Dissociation rate constant of ligand from RP, assuming that it has same dissociation rate constant compared to the native receptor (R) |

| K_L2 | 60 µM | Dissociation constant of ligand bound to RP, which has slightly lower affinity compared to native receptor (R) based on the supplementary data |

| kf_RLP | 0.003 s-1 | Rate constant of β-arrestin 2 binding to phosphorylated ligand-bound receptor to make best fitting compared to Figure 4F and 8F. For β-arrestin 1, we used 0.006 s-1. |

| kr_RLPA1 or kr_RLPA2 | 10-6 s-1 | Dissociation rate constant of β-arrestin from phosphorylated ligand-bound receptor. Same for β-arrestin 1 and 2 |

| Kd_arrestin 1_RLP_PIP2 or Kd_arrestin 2_RLP_PIP2 | 5000 molecules*µm-2 | Dissociation constants of β-arrestin 1 or β-arrestin 2 from RLPA1 or RLPA1 complexes, respectively |

| Kd_PIP2 | 5000 molecules*µm-2 | Dissociation constant of PIP2 dependent clathrin/AP2 binding to the RLPA1 or RLPA2 complexes |

| kf_RLPA1 or kf_RLPA2 | 0.001 µm-2*s-1 | Binding rate constants of RLPA1 or RLPA2 to clathrin/AP2 bound RLPA complexes (RLPAAPC) |

| kr_RLPAAPC | 0.00001 s-1 | Rate constant of clathrin/AP2 dissociation from PLPAAPC complex |

| kf_CCP | 0.01 molecules*µm--2*s-1*µM-1 | Binding rate constant of RLPA1 or RLPA2 to preexisting CCP |

| kr_CCP | 0.00006 s-1 | Dissociation rate constant of RLPA1 or RLPA2 from preexisting CCP |

| kf_ClathrinAP2 | 0.01 molecules*µm--2*s-1*µM-1 | Binding rate constant of clathrin/AP2 to form preexisting CCP |

| kr_ClathrinAP2 | 0.00006 s-1 | Dissociation constant of clathrin/AP2 from preexisting CCP |

| k_endocytosis | 0.001 µM | Binding rate constant of dynamin for receptor endocytosis |

| k_fail | 0.01 molecules*µm-2*s-1 | Dissociation constant of dynamin for failed endocytosis |

| Kd_dynamin | Where, Kd_PIP2 = 2500 molecules/µm2. Dissociation constant of dynamin molecules from endocytic vesicles which have cooperative enhancing mechanisms by PIP2. | |

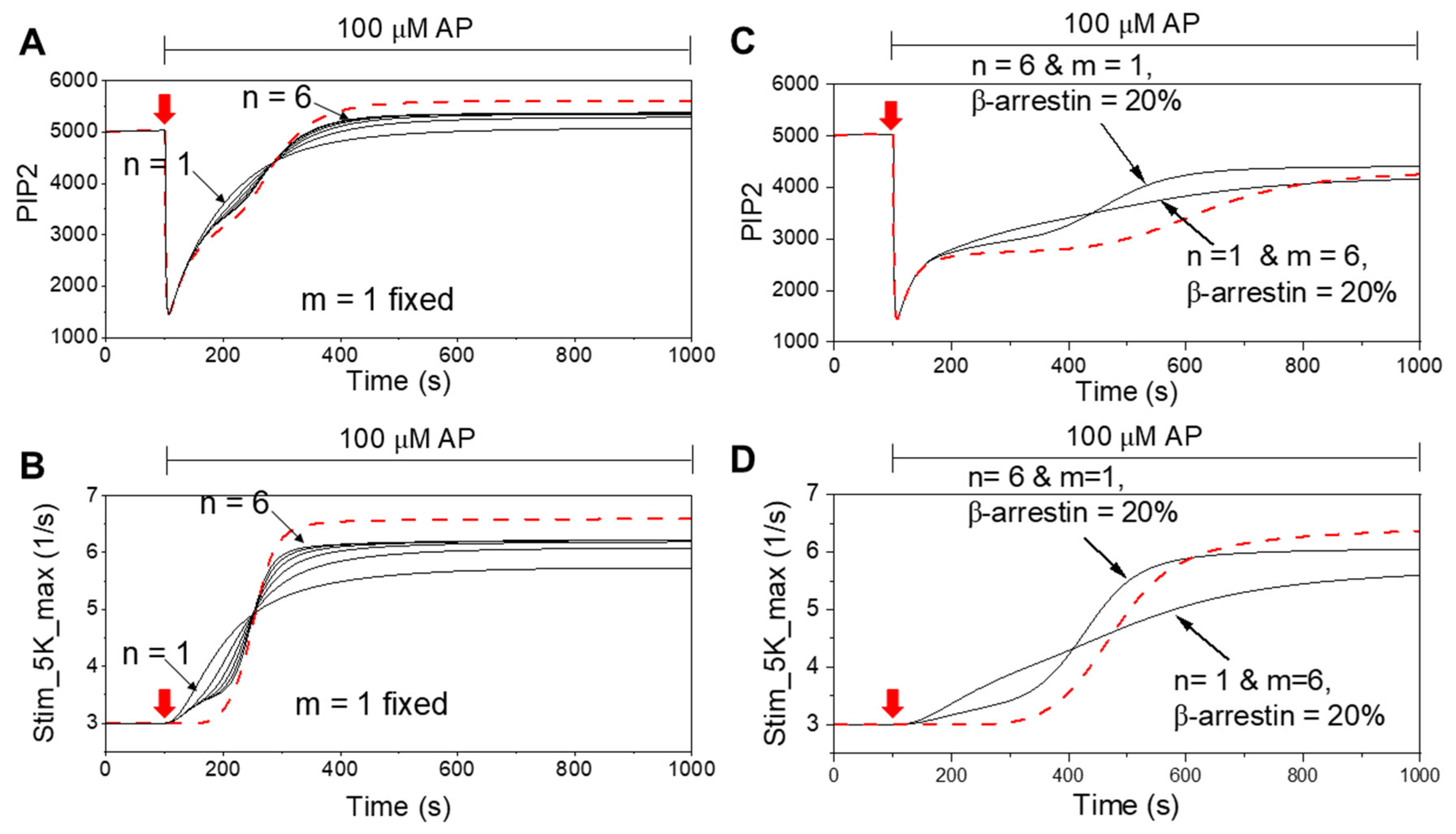

| The rate constant for the PI4K (k_4K during stimulation) = foldPIP2*(k_4K_rest + (stim_4K – k_4K_rest + k_4K_basal)*scale_4K*(1 – exp(-t/tau_on))). Where, tau_on = 1 s, foldPIP2 = 3, scale_4K = 0.75, k_4K_rest = 0.00026 s-1, k_4K_basal = 0.0002353 s-1, stim_4K = 0.00117 s-1). The rate constant for the PIP5K (k_5K during stimulation) = foldPIP2*(k_5K_rest + (stim_5K – k_5K_rest + k_5K_basal)*scale_5K*(1 – exp(-t/tau_on))), where tau_on = 1 s, foldPIP2 = 3, scale_5K = 1, k_5K_rest = 0.02 s-1, k_5K_basal = 0.0181 s-1, stim_5K = . Where, Stim_5K_max = stim_5K_max_basal+stim_5K_max_constant_a*beta_arrestin_contribution_a* + stim_5K_max_constant_b*beta_arrestin_contribution_b* Where, stim_5K_basal = 3, stim_5K_max_constant_a = 3, beta_arrestin_contribution_a = 0.8, Stim_5K_max_constant_b = 6, beta_arrestin_contribution_b = 0.2. | ||

| Reaction | Flux | |

| PI to PI(4)P | k_4K*[PI] – k_4P*[PIP] | |

| PI(4)P to PI(4,5)P2 | k_5K*[PIP] – k_5P*[PIP2] | |

| PLC (basal) | [PIP2]*(PLC_basal + k_ PLC*foldPIP2*Ga_GTP_PLC), where PLC_basal = 0.0001 s-1, k_PLC = 0.2 µm2molecule-1s-1, and foldPIP2 = 3 |

|

| PLC (stimulated) | [PIP2]*(PLC_basal + k_PLC*foldPIP2*Ga_GTP_PLC) + [PIP2]*PLC_stim*Ga_GTP_PLC*[Ca_C/(Ca_C+Kd_PLC_Ca)], where PLC_basal = 0.0001 s-1, k_PLC = 0.2 µm2molecule-1s-1, foldPIP2 = 3, where PLC_stim = 7 s-1, Kd_PLC_Ca = 1 µM | |

| RL to RLP | kf_RL*[RL]*(weighting_factor_PKC_DAG*[PKC_DAG] + weighting_factor_GRK*[GRK]) – kr_RLP*[RLP] | |

| PKC to active PKC | kf_PKC_DAG*[PKC]*[DAG] – kr_PKC_DAG*[PKC_DAG] | |

| R to RP | kf_R*[R]*[PKC_DAG] – kr_RP*[RP] | |

| RP to RLP | kf_L2*AP_Ex*[RP] – kr_L2*[RLP] | |

| RLP to RLPA1 | – kr_RLPA1*[RLPA1] | |

| RLP to RLPA2 | – kr_RLPA2*[RLPA2] | |

| RLPA1 to RLPAAPC | – kr_RLPAAPC*[RLPAAPC] | |

| RLPA2 to RLPAAPC | – kr_RLPAAPC*[RLPAAPC] | |

| RLPA1 & RLPA2 to RLPA_CCP | kf_CCP*[CCP]*[RLPA1]*[RLPA2] – kr_CCP*[RLPA_CCP] | |

| ClathrinAP2 to CCP | kf_ClathrinAP2*[ClathrinAP2] – kr_ClathrinAP2*[CCP] | |

| RLPAAPC to vesicle | – kr_fail*[vesicle] | |

| Many additional reactions which have been already described in our previous paper are not on this table. The parameters are in previous papers [20]. I added arrestin/clathrin/AP2/dynamin dependent endocytosis mechanism in the current model. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).