In order to establish a detailed reaction mechanism and validate its suitability and general use, the influence of a series of key variables was evaluated. Once, the mechanism of elemental reactions was proposed, the set of linear differential equations derived from the reactions carried out in a discontinuous batch reactor was numerically solved.

2.1. Effect of Fe(III) Concentration

The system PMS/Fe(II) is believed to act in a similar way to Fenton´s chemistry [

6], i.e. generation of highly reactive radicals is postulated to occur:

k=3x104 M-1s-1 (1)

Additionally, some authors also claim the formation of Fe(IV) species, suggesting the absence of hydroxyl radicals [

4]:

k=2.2 x104 M-1s-1 (2)

k=9.0 x104 M-1s-1 (3)

k=1.5 s-1 (4)

k=1.2 x106 M-1s-1 (5)

k=2.8 x105 M-1s-1 (6)

Formation of Fe(IV) species has also been reported to occur in the classical Fenton´s reaction under circumneutral pH conditions, while HO• radicals are generated at acidic pH [

7].

If the reactivity of FeO2+, HO• and SO4-• with pCtchA is assumed to be similar, the nature of the reactive species generated in the PMS/Fe system is irrelevant in terms of simulation purposes (notice that peroxymonosulfate scavenging of the three oxidants is comparable). Accordingly, in this work it was decided to ignore FeO2+ formation, assuming that model results would not significantly change.

Together with the initiation reaction (eq. 1), the following mechanism was therefore adopted [

1,

2,

4,

8]:

HSO5- + Fe(III) → Fe(II) + H+ + SO5-• k=unknown (7)

SO4-• + Fe(II) → SO42- + Fe(III) k = 4.6 x109 M-1s-1 (8)

HO• + Fe(II) → HO- + Fe(III) k = 3.2 x108 M-1s-1 (9)

H2O2+ Fe(II)→ HO• + Fe(III)+OH- k = 50-70 M-1s-1 (10)

SO5-• + Fe(II) +H+→ HSO5- + Fe(III) k = 4.3 x107 M-1s-1 (11)

Fe(III) + HO2• → Fe(II) + O2 + H+ k = 7.8 x105 M-1s-1 (12)

Fe(II) + HO2• → Fe(III) + H2O2 k = 1.3 x106 M-1s-1 (13)

SO4-• + HSO5- → HSO4- + SO5-• k < 1 x 105 M-1s-1 (14)

HO• + HSO5- → SO5-• + H2O k = 1.7 x107 M-1s-1 (15)

HO• + SO52- → SO5-• + OH- k = 2.1 x109 M-1s-1 (16)

k = 2.7 x107 M-1s-1 (17)

k = 7.5 x109 M-1s-1 (18)

k = 3.0 M-1s-1 (19)

k = 0.13 M-1s-1 (20)

k = 6.6 x102 s-1 k- = 6.9x105 M-1s-1 (21)

k = 6.5x107 M-1s-1 (22)

k = 2.15 x 108 M-1s-1 (23)

k = 7.5 x 108-3.6 x 109 M-1s-1 (24)

k = 3.5 x 108 M-1s-1 (25)

2HO• → H2O2 k = 5.2 x 109 M-1s-1 (26)

+HO• → HSO5- k = 1.0 x 1010 M-1s-1 (27)

k = 6.5 x 105 M-1s-1 (28)

k = 1.4 x 107 M-1s-1 (29)

k = 8.3 x 105 M-1s-1 (30)

k = 9.7 x 107 M-1s-1 (31)

k = 6.6 x 109 M-1s-1 (32)

k = 7.0 x 109 M-1s-1 (33)

k = 7.5 x 10-5 M-1s-1 (34)

pKeq = 9.4 (35)

pKeq = 14 (36)

k = 0.012 s-1 (37)

pKeq = 11.6 (38)

HO2• H+ + O2-• k = 3.2 x 105, k- = 2.0 x 1010 (39)

pCtchA + SO4-• Intermediate + SO42- k = 1.2 x 109 M-1s-1 (40)

pCtchA + HO• Intermediate + HO- k = 2.2 x 1010 M-1s-1 (41)

pCtchA + HSO5- Intermediate k = 0.02 M-1s-1 (42)

Intermediate + SO4-• Intermediate2 + HSO42- k = 109-1010 M-1s-1 (43)

Intermediate + HO• Intermediate2 + HO- k = 109-1010 M-1s-1 (44)

Intermediate2 + SO4-• Product + HSO42- k = 109-1010 M-1s-1 (45)

Intermediate2 + HO• Product + HO- k = 109-1010 M-1s-1 (46)

In the previous reaction mechanism, the following aspects have been considered. First, pCthA can be directly oxidized by peroxymonosulfate (eq. 42) through a non-radical pathway similarly to other reported compounds [

1]. Additionally, two intermediates have been considered with assumed reactivity with radicals similar to that of the parent compound (eqs. 43-46).

Development of direct pCtchA oxidation was confirmed in discontinuous runs in the presence of PMS at the pH obtained after reagents addition (pH around 3.4).

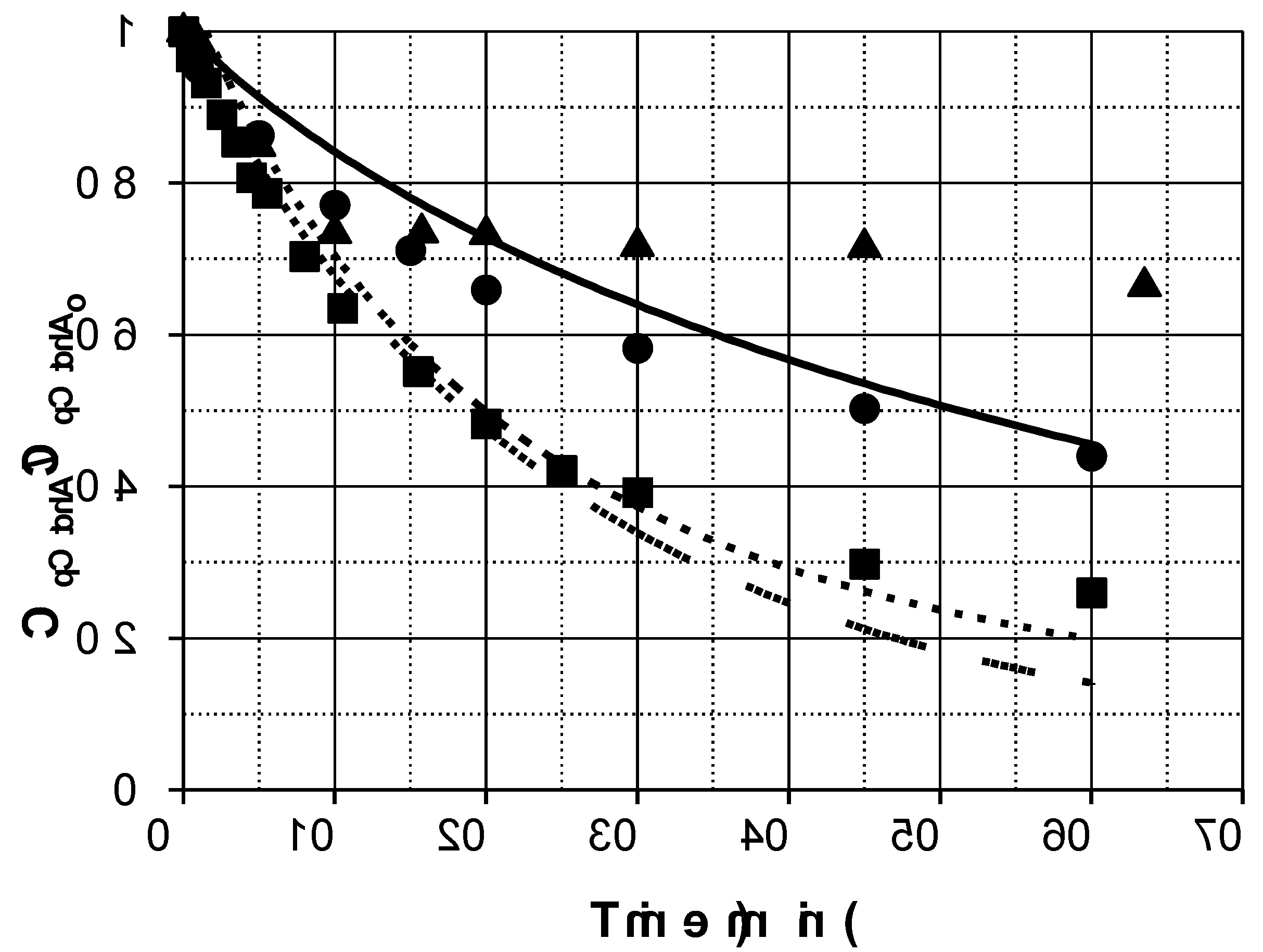

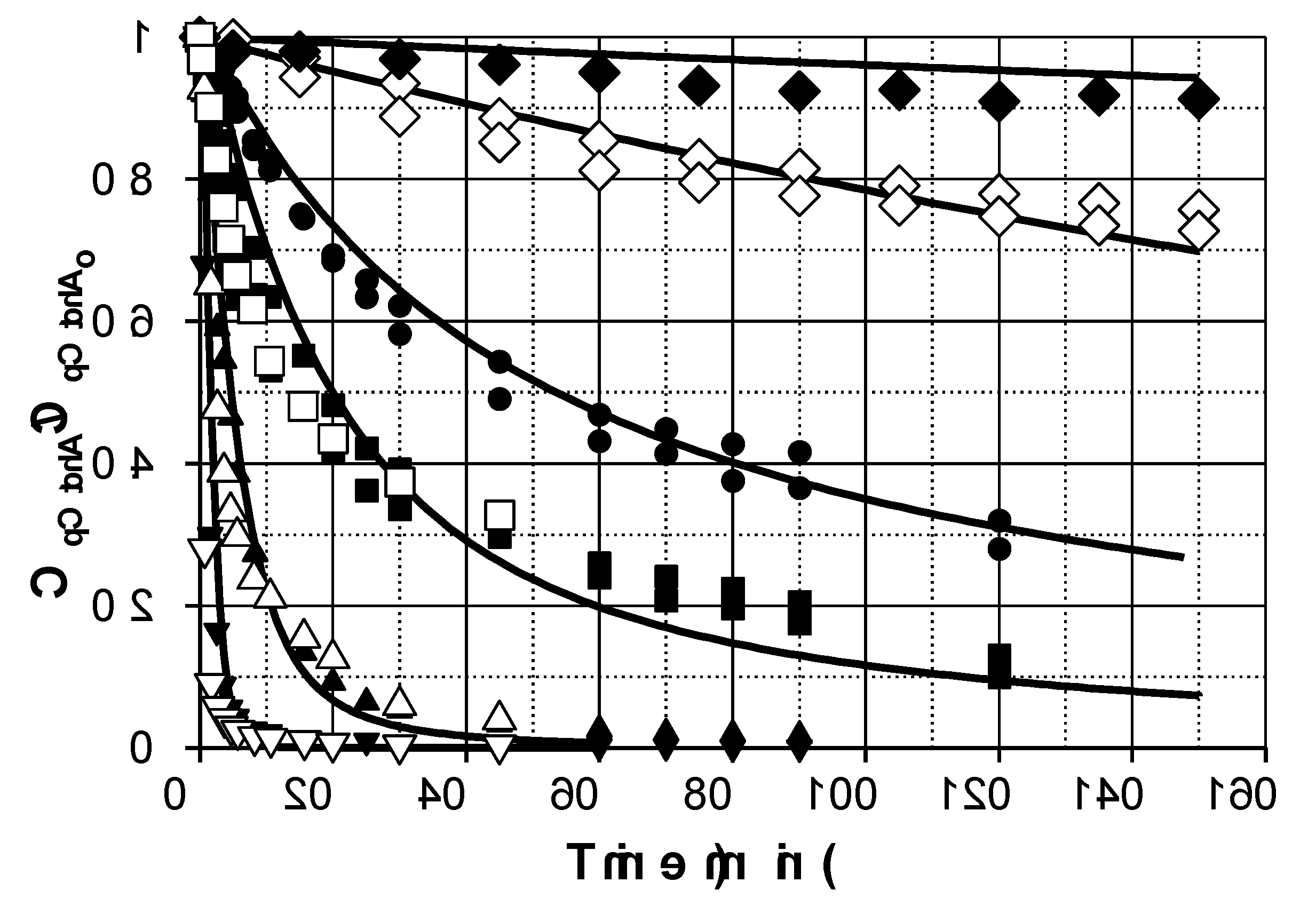

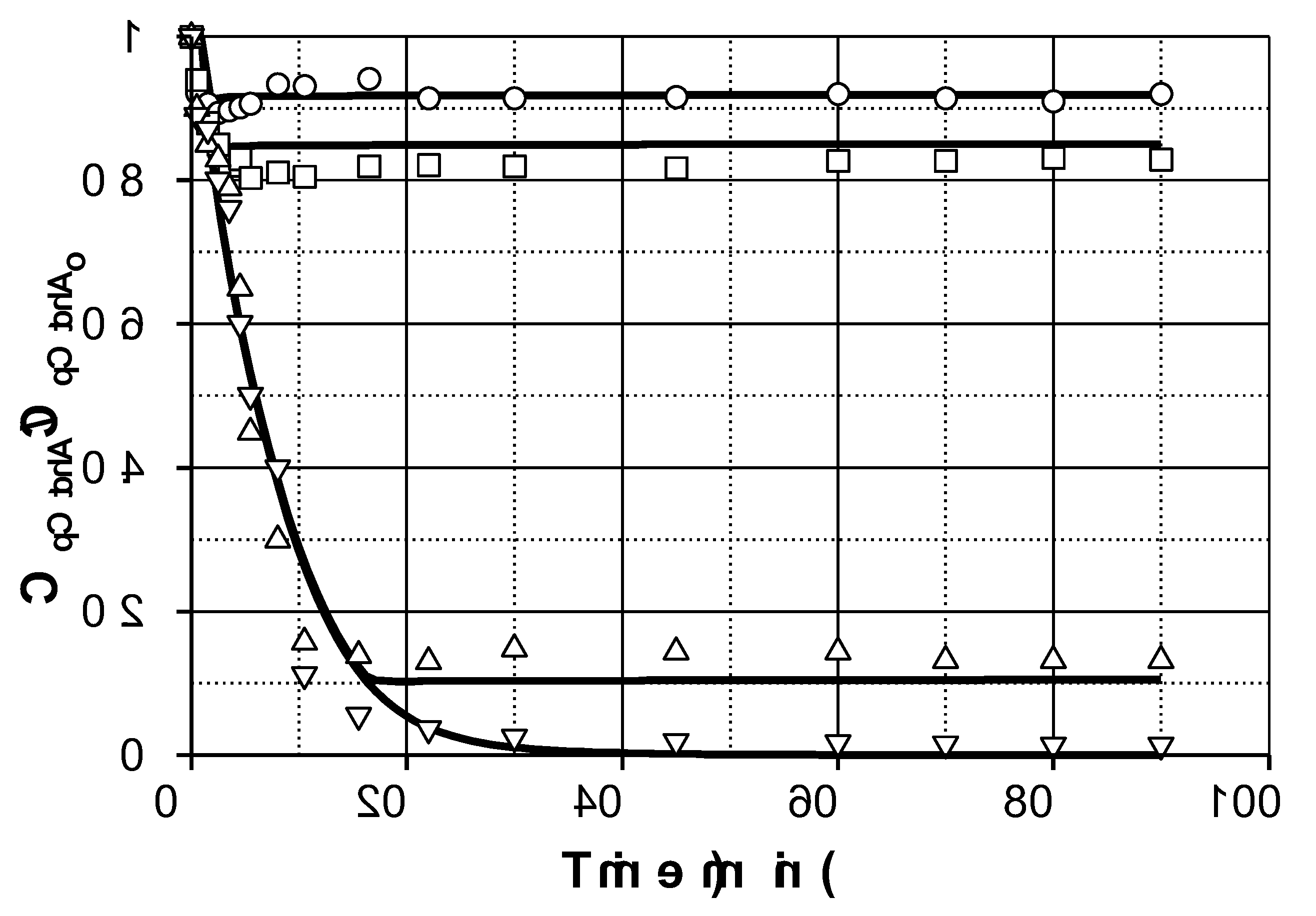

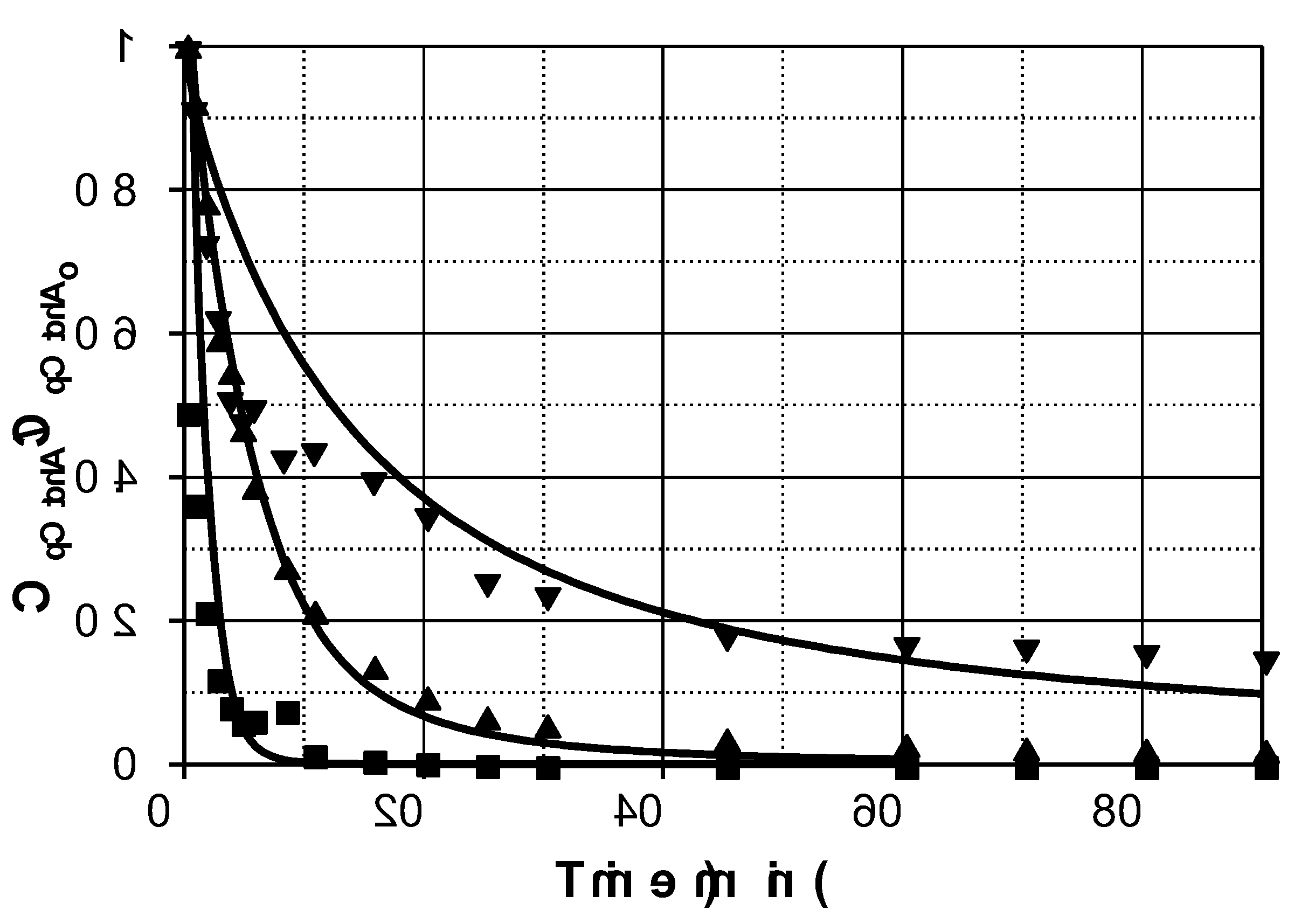

Figure 1 shows the results obtained at two different initial PMS concentrations. Hence, under the conditions investigated, for a discontinuous perfectly mixed reactor, in the absence of catalyst, pCtchA removal could be modelled by a simple second order reaction of the type:

(47)

The direct rate constant k was estimated to be 0.02 + 0.003 M-1s-1, leading to a 25-30% conversion in 150 min when the highest PMS concentration was used.

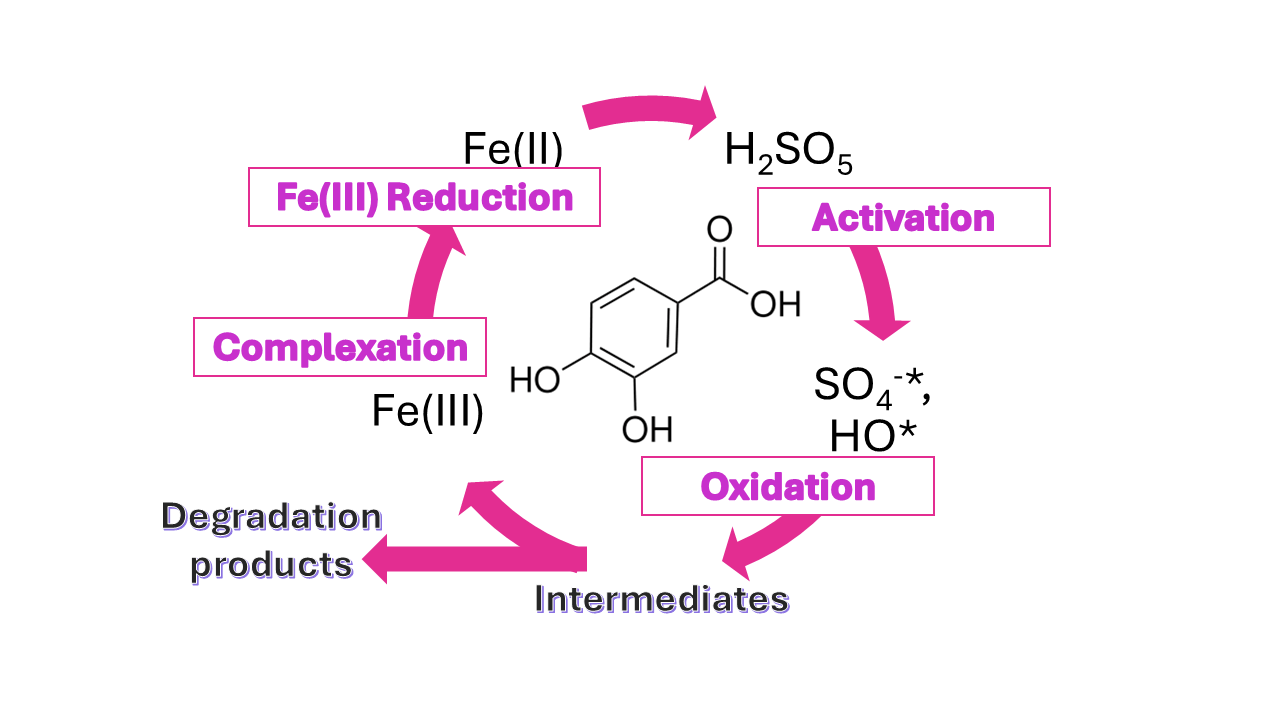

Moreover, the interaction of polyphenols and iron species has also been reported in the literature. Hence, Pan and co-workers [

5] claim that ortho-dihydroxy groups in polyphenols (as it is the case of pCtchA) can reduce Fe(III) to Fe(II) via a one-electron reaction leading to the formation of semiquinones. The previous assumption was corroborated in this work by conducting oxidation experiments of caffeic and p-coumaric acids. These experiments revealed a high conversion in the first case and no effect when p-coumaric acid was used (results not shown). Accordingly, the following reactions were incorporated to the overall mechanism to account for the Fe(III) reduction stage [

8]:

Keq = 1.18 x 104 M-1 (48)

k = 3.3 x10-2 s-1 k- = 3.0 x104 M-1s-1 (49)

k = 1.0 x105 M-1s-1 k- = 1.0 x101 M-1s-1 (50)

Reactions 48 and 49 are key stages in the process. The forward rate constant of the complex formation (eq. 48) is reported to highly depend on pH. Hence, deprotonation of polyphenols is required for metal chelation [

5], although some controversy is raised about this statement [

9]. Hence, Mentasti et al. report a complex formation rate constant depending on proton concentration according to the mechanism [

9]:

(51)

(52)

(53)

From the mechanism 51-53 it is seen that an increase in protons concentration promotes the reverse reactions in equilibriums 51 and 52 while a decrease in H+ favours formation of Fe(OH)2+.

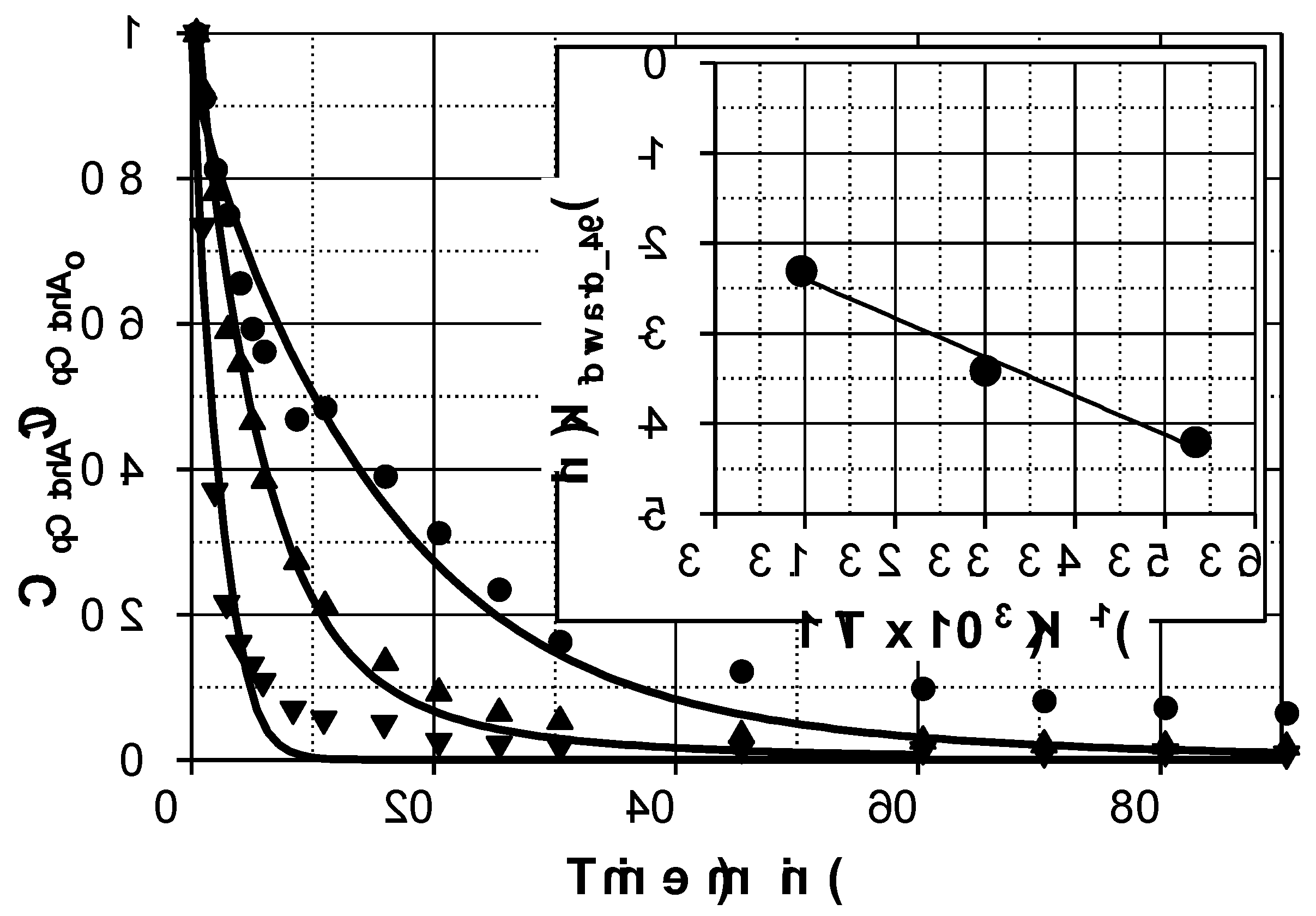

Based on the previous reasoning, a negative effect of H+ concentration (pH decrease) is assumed and accounted for in the kinetic analysis. A value of 1.7 x 103 M-1s-1 is reported in the literature for the forward reaction in equilibrium 48. This value was randomly assigned to occur at pH 3 so the forward rate constant was supposed to inversely change with protons concentration according to kforward_48 =1.7/CH+.

According to the previous statement, the presence of Fe(III) would be able to remove pCtchA when PMS is added due to iron reduction and formation of radicals through equation 1.

Figure 1 shows the evolution profiles of pCtchA removal when different amounts of Fe(III) were added in the presence of PMS. As commented previously, pH evolution was taken into account since this parameter highly affects Fe(III) reduction. A linear decrease of pH was experienced in all the experiments from 3.5 to 1.7-2.0 depending on operating conditions.

As inferred from

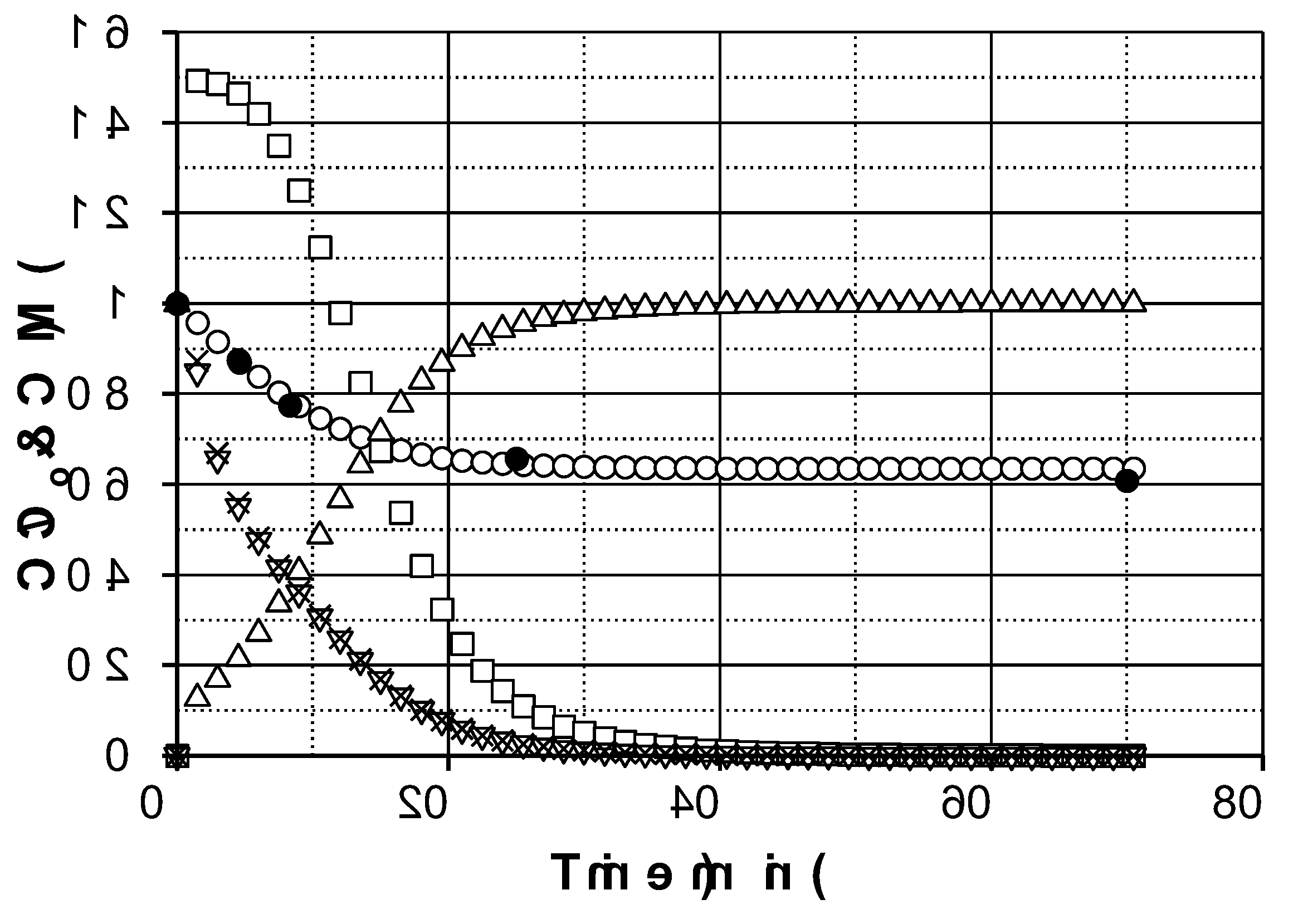

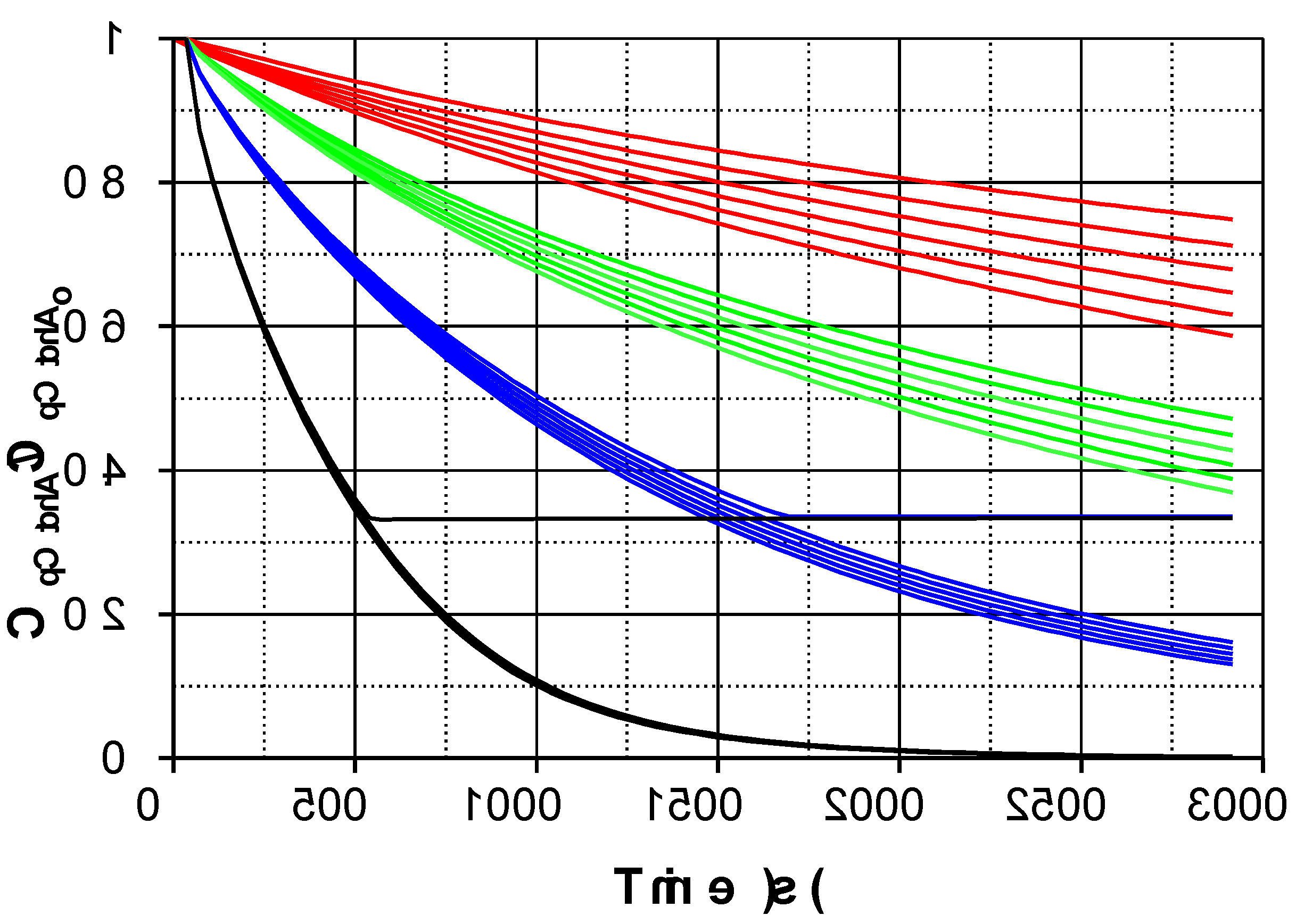

Figure 1, addition of Fe(III) significantly accelerates pCtchA oxidation even when the ratio Fe(III):pCtchA is extremely low. The model is capable of acceptably simulate the influence of Fe(III) initial concentration not only on the pCtchA disappearance but also in the evolution of PMS. Peroxymonosulfate undergoes a relatively fast initial reduction coinciding with the decrease in Fe(III) concentration. Once pCtchA disappears, Fe(III) concentration recovers its initial value while PMS stabilizes in time. As an example,

Figure 2 shows the evolution profiles of PMS (experimental and simulated), iron species and radicals in a typical experiment obtained from the model.