1. Introduction

Advances in autonomous aerial systems have garnered considerable attention as both a practical engineering challenge and a domain of strategic importance. Realistic flight agents underpin next-generation flight simulators and serious video games. Despite this broad interest, most deployed autonomy solutions are rule-based, consisting of expert-designed state machines or hierarchical controllers that are adequate for auto cruise control or obstacle-avoidance tasks, but fall short in more complex engagements such as suppression of enemy air defenses, escorting, and point protection.

Within-Visual-Range (WVR) aerial maneuver game encompasses basic flight maneuvers and requires split-second decisions, and mastering it is a critical step toward fully autonomous flight agents. Recent work has explored Reinforcement Learning (RL) for WVR engagements [

1], demonstrating that agents can learn basic tactics in simplified settings. However, many of these methods rely on handcrafted architectures that stitch learned sub-policies into high-level coordinators. Such designs lack scalability and generality, and they require substantial domain expertise, which has impeded broader research efforts.

In this work, we aim to train a single, end-to-end reinforcement learning policy to master a full one-on-one WVR engagement. Motivated by recent empirical findings of Model-Based Reinforcement Learning (MBRL) applied in competitive settings [

2], we adopt the Dreamer framework as the foundation for our algorithm, given its state-of-the-art performance on a wide range of continuous control benchmarks. However, applying Dreamer out of the box in a full aerial maneuver game reveals several key challenges: first, the mutual influence between imagination-driven background planning and self-play dynamics remains understudied; second, abrupt terminations, coupled with the stochastic, discontinuous nature of aerial maneuver dynamics, undermine standard latent-rollout techniques that rely on smooth transitions. In addition, balancing aggression with survival through tuning of crash vs. kill rewards proves sensitive to reward scales. To address these issues, we design a Dreamer-style algorithm with enhanced termination sensitivity and robust self-play training. Our main contributions are threefold:

We extend the Dreamer architecture and introduce a learning paradigm that improves the model’s predictive accuracy in the vicinity of rare crash events, and also the robustness of actor-critic learning.

We derive a risk-aware learning objective that facilitates high-speed maneuver learning while bounding the overall crash rate, without extensive reward scale tuning.

We design a pipeline that bootstraps learning with curriculum initialization, drives strategy discovery through self-play exploration, and finetunes against specific opponents for rapid adaptation.

We demonstrate that, with these modifications, a single Dreamer-style policy can learn effective aerial maneuver tactics from scratch, without relying on expert domain knowledge.

2. Related Works

Efforts to

automate competitive air-to-air flight games began with rule-based expert systems, exemplified by TacAir-Soar in the late 1990s [

3]. With regard to learning-based approaches, earlier studies [

4,

5] demonstrated that autonomous agents could learn basic WVR manuerver tactics through deep RL but were constrained by low-fidelity, 3-DoF environments and limited computational resources. In 2019–20, DARPA’s AlphaDogfight Trials saw a Heron Systems deep RL agent defeat a seasoned F-16 pilot 5-0 in a 6DoF simulated engagement [

6], and academic teams using hierarchical RL architectures achieved top placements [

1]. However, most recent deep RL approaches surveyed [

7,

8,

9] still abstracted the action space to high-level behaviors or tactics, or employ complex hierarchies to cover the vast state space. In contrast, our work explores truly end-to-end model-based reinforcement learning of WVR high-speed maneuver techniques and tactics with a single policy and minimal domain priors.

Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) learns a World Model (WM) to simulate the true dynamics of the environment. This WM can be employed either for decision-time planning [

10,

11] or for background planning [

12,

13]. Decision-time planning methods(e.g., Model Predictive Control [

14] or Monte Carlo Tree Search [

15]) conduct online look-ahead by simulating candidate action sequences under the WM and selecting actions that maximize predicted returns at each step. In contrast, background-planning algorithms amortize model rollouts by generating imagined experiences to update actor and critic networks. A second, orthogonal axis of distinction is whether the WM is a generative observation model, capable of reconstructing raw sensory inputs [

12], or a latent-only model(e.g., contrastive or predictive state representations), trained in self-supervised manners without an explicit decoder [

10]. A third axis concerns how uncertainty is represented and managed within the WM. Classical approaches employ probabilistic ensembles [

16] or Bayesian neural networks [

17] to estimate epistemic uncertainty and mitigate its impact on planning explicitly; More recent methods leverage powerful generative architectures to holistically model both aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty without disentangling their sources. The Dreamer family of MBRL algorithms, which form the basis of our work, occupies the quadrant defined by background planning, generative WM(via a latent bottleneck), and holistic uncertainty modeling. Readers can refer to [

18] for a more comprehensive review of MBRL.

Self-play has been explored extensively in the multi-agent reinforcement learning literature, ranging from simply matching against past versions of selves [

19,

20,

21] to more complex, game-theoretic frameworks such as PSRO [

20] and NeuPL [

22]; Readers can refer to, e.g., [

23] for a more comprehensive review. However, the majority of the empirical studies are based on model-free RL methods; efforts to couple MBRL with self-play remain scarce. WMs offer the promise of explicitly capturing opponent strategies and thereby improving generalization, but the non-stationarity induced by self-play poses a significant challenge for stable model learning. In this work, we take a first step toward bridging this gap by integrating a recurrent WM into a population-based self-play regime, showing that a single model-based policy can robustly master competitive senarios of highly specialized domains.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Zero-Sum Stochastic Games & Neural Self-Play

One-on-one aerial maneuver game is an instance of a two-player zero-sum stochastic game, where both players interact with the environment simultaneously. Such a game can be formally defined by the tuple

, where

S is a finite set of states,

is the finite action set for player

i,

is the transition kernel,

is the reward for player 1 (player 2 receives

), and

is the discount factor. At each step

t, in state

, players sample actions

and

; then the environment transitions to

, and player 1 receives reward

. The cumulative return is

which player 1 seeks to maximize and player 2 to minimize. The corresponding state-value function under policies

is

The minimax value

characterizes the value of the game, and under standard compactness assumptions, there exists a stationary Nash equilibrium

achieving

[

24,

25]. Exact dynamic-programming methods for solving stochastic games suffer from the “curse of dimensionality”. Self-play has therefore emerged as a scalable, model-free paradigm: the agent iteratively refines its policy by playing against itself or mixtures of past policies, using reinforcement-learning updates on the generated data. Variants of self-play (e.g., Neural Fictitious Self-Play [

26]) have proven instrumental in developing superhuman agents in complex competitive zero-sum domains such as Go, chess [

27], and StarCraft II [

21].

3.2. The Dreamer Algorithm

Our approach branches from DreamerV3 [

28], the latest heritage of the Dreamer family of model-based reinforcement learning algorithms. Dreamer utilizes a recurrent state-space model (RSSM) to learn a compact latent state

that predicts future rewards/discounts and reconstructs raw observations via a variational decoder. At each training iteration, Dreamer:

The learned decoder is not used at inference; the reconstructions serve solely as a self-supervision signal to regularize and stabilize learning of latent representation. This architecture yields a purely reactive policy at runtime and achieves state-of-the-art data efficiency and asymptotic performance on popular vision and proprietary benchmarks.

3.3. Constrained MDPs

In real-world flights, ensuring survival is indispensable, yet this imperative does not always align with maximizing offensive impact. To encode this dual objective, we employ the framework of

Constrained Markov Decision Processes (CMDPs) [

30]. A CMDP augments the standard MDP

with a cost function

and a cost budget

. The learning problem is

where

is the usual discounted return and

the expected discounted cost (e.g. crash probability). Solving for the CMDP fosters SafeRL [

31], where one seeks policies that satisfy

while optimizing performance. A common approach is to form the augmented Lagrangian

where

parameterizes the policy,

is a Lagrange multiplier, and

a penalty coefficient. By tuning

b, one balances utility and safety. This methodology is shown to integrate seamlessly with model-based agents [

32].

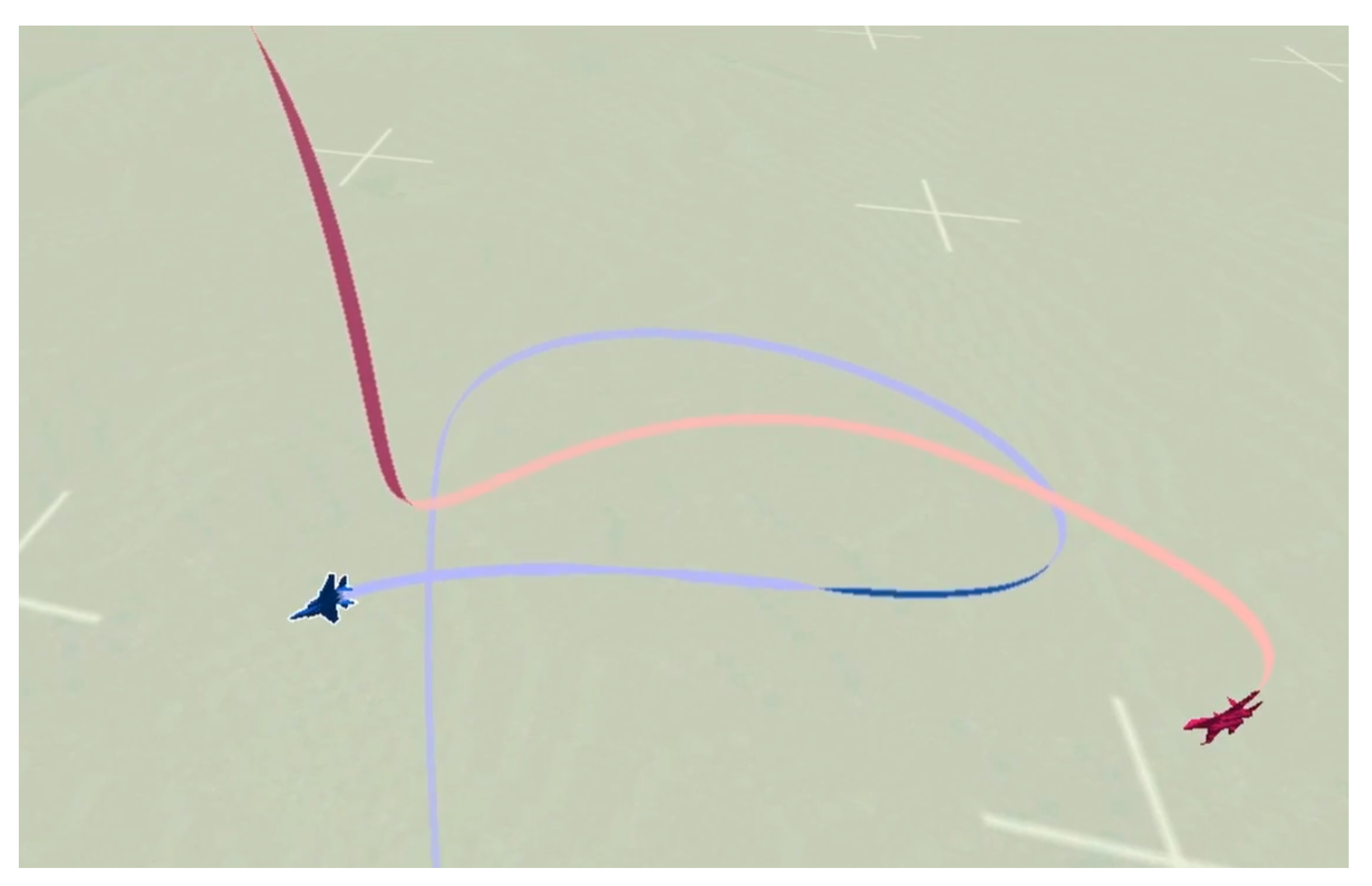

3.4. Aerial Manuever Game Environment

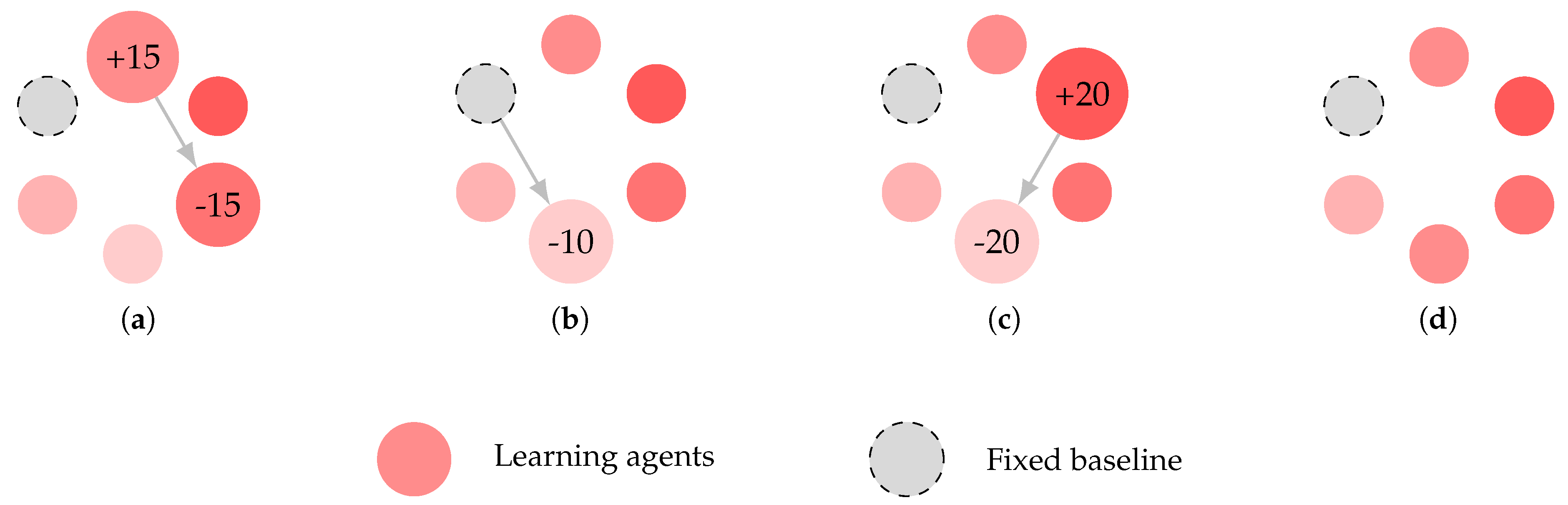

We investigate one-to-one (red versus blue) WVR pursuit-evasion games, as demonstrated in

Figure 1. The physics of aircraft is simulated using JSBsim [

33], an open-source, high-fidelity 6DoF flight dynamics model. We expose proprietary vector observations and a discrete action space. Details of the scenario, simulation parameters, and environment specifications are provided in

Appendix A.

4. Learning Algorithm

Overview

Dreamer-style algorithms typically consist of four components: the World Model (WM) predicts the outcomes of potential action sequences, the critic evaluates the expected return of each outcome, the actor chooses actions to reach the most valuable outcomes, and the replay buffer accumulates experiences for replay. Aerial manuever environments bring abrupt termination events, discontinuous dynamics, and aggressive-survival tradeoff; challenges largely absent from standard control benchmarks. First and foremost, we elucidate the major adaptations to vanilla Dreamer’s WM, critic, actor, and replay modules that accommodate the unique difficulties of learning aerial manuevers.

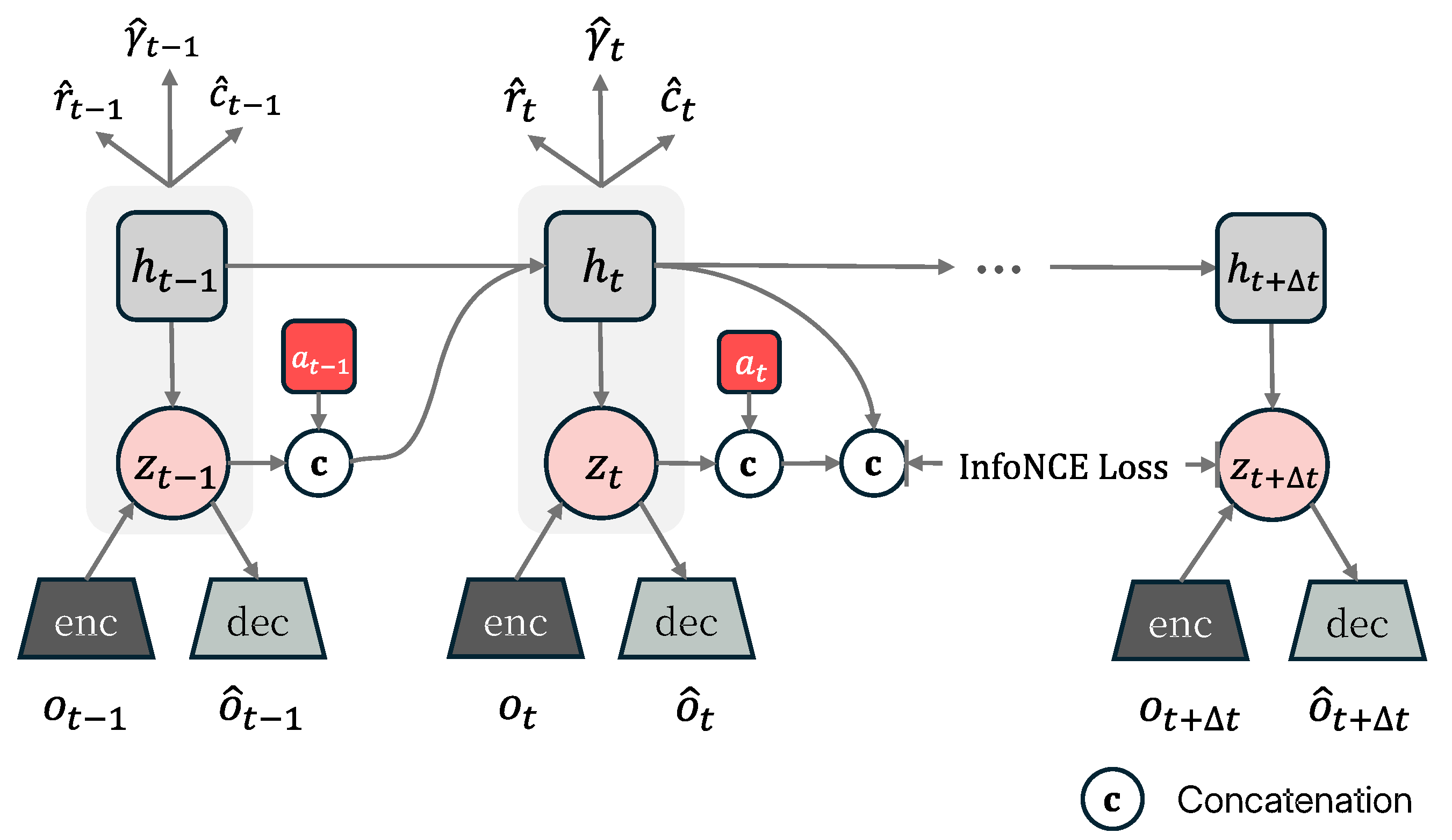

World model architecture and objectives. We replace Dreamer’s GRU sequence model with an RWKV-style linear attention backbone, enabling parallelizable training via scan while preserving long-context credit assignment. Beyond the ELBO reconstruction objective, we add a termination-aware CPC loss: This explicitly biases the latent dynamics toward long-horizon, crash-relevant structure.

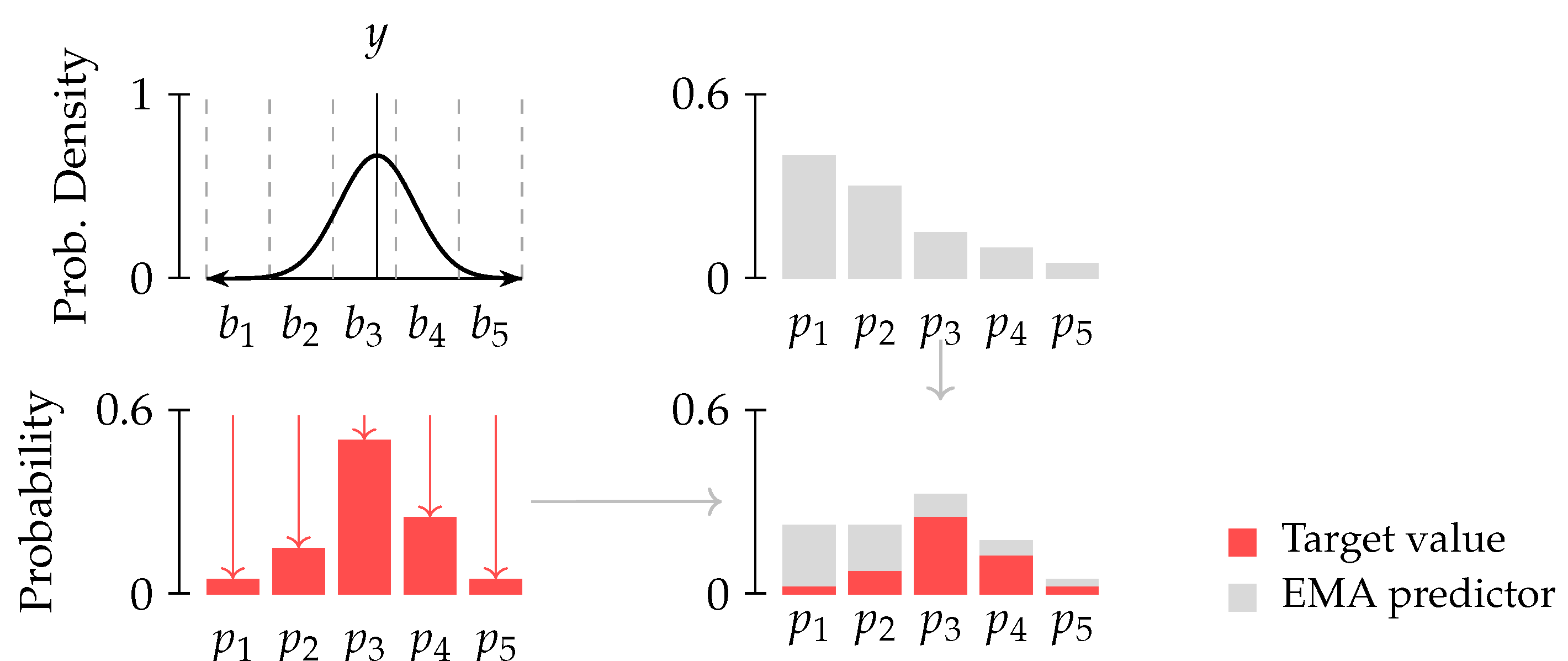

Distributional parameterization of reward and value. Instead of scalar regression used in standard Dreamer heads, we model reward, return, and cost as categorical distributions on finite support with exponentially spaced bins. Targets are formed by fusing a Gaussian-smoothed histogram of the scalar label with an EMA teacher distribution, and optimized via cross-entropy.

Constrained policy optimization under learned dynamics. Rather than tuning reward scales to break stalemates, we cast learning as a constrained MBRL problem: Maximizing expected return while constraining expected crash probability/cost under the learned model.

Dyna-style actor–critic updates. In contrast to Dreamer’s purely imagined updates, we mix imagined rollouts with off-policy real updates computed via V-trace on replayed data.

Value-aware robustness regularization. To mitigate value amplification of small model errors, we add a Lipschitz-consistency penalty on the critic’s output distribution.

Multiagent Learning Pipline. Unlike single-agent Dreamer on control tasks, we use a three-phase scheme including cirriculum initailization, population self-play and few-shot adaptation.

4.1. World Model Learning

We denote by

the symlog [

28] transformed raw vector observation at time

t, by

the deterministic recurrent state of the sequence model, and by

the stochastic states.

constitutes the history-encoding model states. Each network within the WM models a conditional distribution:

Contrastive Predictive Coding

The standard ELBO objective in Dreamer relies on a reconstruction term that only enforces next-step predictions, which exploit the local smoothness of the signal. This biases the Dreamer’s WM to generate locally plausible segments without a globally coherent structure, which exacerbates the difficulty in anticipating rare termination events. To remedy this, we incorporate a

Contrastive Predictive Coding (CPC) [

34] objective that encourages the latent representation to capture long-range dependencies and to be particularly sensitive to dynamics near termination, as shown in

Figure 2.

Formally, we want to maximize the Mutual Information(MI)

between the context

and some future observation

that is both (i) not imminent, i.e., at least

k steps ahead (ii) in the vicinity of a termination event i.e., within

m steps of a termination flag. Directly modeling conditional distribution

captures redundant local dependency in

. Instead, we estimate a density ratio using contrastive samples from

and

and regularize the WM with the InfoNCE lower bound. We introduce a critic function

and form one positive pair

(same trajectory,

) and negatives

sampled from other time indices or trajectories. The InfoNCE loss is

where

is a temperature parameter. Minimizing

maximizes a lower bound on

. In practice, we integrate this into WM learning by augmenting the ELBO with weight

:

Modeling Categorical Reward Distributions

Training the reward model to predict a stochastic regression target is prone to outliers, especially when termination events correspond to large rewards. Instead, we model symlog transformed reward

r as a categorical distribution supported on

with

B bins. The predictor is trained to produce a probability vector

that parameterizes this distribution, which is derived from the logits through the softmax function. The major hurdle here is to define a procedure to construct the target distribution and its associated projection onto the set of categorical distributions. We revise the approach in [

35] and construct the target distribution as described below:

Treat the observed scalar target

r as a random variable

, where

is a fixed hyperparameter. Define exponentially spaced bin boundaries

on

. Compute the histogram

of the Gaussian [

36]:

-

Form the target distribution by combining the histogram

with the outputs of a target predictor

, whose parameters are the Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of the online predictor:

Finally, update the online predictor

via the cross-entropy loss

This process is visualized in

Figure 3. At inference time, we recover a scalar estimate via the Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) at level

:

where

is the quantile function of

and we set

.

Figure 3.

Visualization of categorical target value projection for cross-entropy based learning. We distribute the probability mass to neighbouring locations (which is akin to smoothing the target value).

Figure 3.

Visualization of categorical target value projection for cross-entropy based learning. We distribute the probability mass to neighbouring locations (which is akin to smoothing the target value).

Experience Replay

We store full episodes in the replay buffer and sample fixed-length trajectories of

steps (12.8 simulation seconds) for each WM update. To assemble a minibatch of size 16, we mix:

Trajectories shorter than

T are padded to include the final transition. We store latent states into the replay buffer during data collection, and use burn-in [

37] to initialize the WM on replayed trajectories.

Network Architecture

DreamerV3’ original sequence model uses GRU recurrence to generate model states

, but GRUs’ sequential steps impede parallel training. We therefore replace them with an RWKV style linear-attention [

38,

39] with RMSNorm [

40] and GELU activations [

41], which can be parallelized via scan [

42]. Other components are implemented as dense MLPs with LayerNorm [

43] and GELU activations.

4.2. Actor-Critic Learning

Although our scenario is formally a zero-sum game, the allowance for draws introduces a practical challenge: once both agents master evasive maneuvers, matches often end in stalemate, diluting the learning signal. Hand-tuning kill rewards versus crash penalties to break these ties is brittle—small changes in their relative scale can tip the agent toward overly aggressive tactics causing crashes or extreme terminal states, or otherwise overly cautious, non-engaging behavior. To address this, we adopt a constrained model-based reinforcement learning formulation. We assign a cost of 1 only when the aircraft is destroyed by accident, i.e. crash and overload, and terminations due to reaching maximum episode duration incur zero cost. Accordingly, we optimize

where

is the expected reward,

the expected crash probability(or cumulative costs) under the learned dynamics

, and

b is a user-specified crash-rate budget. This constraint enforces a controllable aggression–survival trade-off: the agent maximizes its score while keeping the likelihood of being shot down below

b. By adopting the relaxation technique of the Lagrangian method, the formulation above is transformed into an unconstrained optimization problem, where

is the Lagrangian multiplier:

To estimate cumulative costs, we additionally learns a cost critic

along with the return critic

. The actor and critics operate on model states

and thus benefit from the Markovian representations learned by the WM. We use the REINFORCE estimator [

29] and obtain the surrogate actor loss for the unconstrained policy objective:

where sg denotes the stop-gradient operator,

and

are bootstrapped

-return and

-cumulative costs, and

denotes the Augmented Lagrangian. Define

, and let the non-decreasing penalty term

corresponds to current gradient step

k, the update rules for

and

are as follows [

44]:

Modeling Categorical Return Distributions

We adopt the same categorical-projection procedure as for rewards: each scalar target (or ) is first transformed into a Gaussian distribution, then discretized into B bins to form a histogram on , then merged with the EMA-updated target critic output and finally normalized to . The online critics are updated by minimizing the respective cross-entropy loss against this target distribution. At inference time, we recover the scalar return estimate from CVaR with , and the cumulative cost estimate from distribution mean.

Dyna-Style Actor-Critic Updates

Most recent model-based methods (including Dreamer) perform actor-critic updates solely on imagined rollouts, risking over-reliance on an imperfect WM, especially near terminations. We instead adopt a Dyna-style scheme that mixes imagined trajectories with real experiences for policy learning. At each actor-critic update, we generate on-policy imagined rollouts of horizon

starting from replayed states during WM learning, and compute the

-returns

and advantages

; Simultaneously, on the replayed real trajectories we compute off-policy V-trace [

45] returns

and advantages

. The combined surrogate actor loss and cross-entropy critic loss are formed as weighted sums of their imagined and real components.

Regulating Model-Aware Value Error

Even when the learned WM is approximately accurate in terms of the ELBO, the prediction error can still be amplified by the value function updates. Value-aware model error [

46] measures the difference between the simulated and true Bellman operator acting on a given value function, and can be made small by promoting the local smoothness of the value function. To this end, we add a Lipschitz-consistency regularizer [

47]. For each model state

, We define a consistency loss:

with

. In practice, we approximate this maximum by a single FGSM [

48] step in latent space, then add

to the standard value loss.

Network Architecture

Both actor and critic networks are implemented as MLPs with LayerNorm and GELU activations, and are trained concurrently with the WM. We alternate two WM gradient updates with one actor-critic update to ensure stable learning. Inspired by [

49], we replaced each critic’s penultimate MLP layer with a soft-MoE block [

50] and observed an incremental performance gain as the number of experts increases; applying the same modification to the actor network yielded no benefit.

4.3. Learning Curriculum & Self-Play

Pure self-play agents (using only a win–loss reward signal) learn slowly and are susceptible to converging on a single, easily countered offensive pattern. In this section, we outline a three-phase pipeline that (i) initializes learning via a curriculum of heuristic opponents, (ii) promotes strategic discovery through self-play exploration, and (iii) fine-tunes against specific adversaries for rapid adaptation. Throughout all phases, the WM is conditioned on learnable embeddings of the ego and opponent policy identities, accounting for the dynamics introduced by different ego-opponent policy pairs.

Curriculum initialization

We design three rule-based bots to bootstrap training:

Pursuit Agent: Seeks a pursuit position behind the opponent.

Maneuver Agent: Does not actively pursue, but executes various escape maneuvers if engaged.

Aggressive Agent: Adopts a risk-seeking policy that approaches the opponent frontally to induce high-intensity interactions.

These heuristics capture core pursuit-evasion tactics and serve as initial benchmarks. Our curriculum pool comprises the rule-based bots and under-trained PPO [

51] self-play agents. In each episode, an opponent is sampled uniformly from this pool. During curriculum initialization, we employ handcrafted pseudo-rewards to encourage human-like flight behaviors, as described in [

1].

Self-Play Exploration

We employ a population-based self-play framework with Elo-based matchmaking to drive strategic discovery as shown in

Figure 4. Rather than updating a single agent against static past versions as in fictitious self-play, we train a fixed population of

N policies in parallel to introduce diversity and scalability [

52]. Each member of the population is initialized with the curriculum-trained agent and participates in repeated self-play tournaments. During each self-play training cycle, we iterate over all

N policies in sequence. For a given policy, we conduct a batch of 10 training episodes in which the opponent is sampled according to current Elo ratings, except that with probability

a PPO-trained baseline with fixed Elo rating is selected instead. After each episode, we update the Elo ratings of the matched policies immediately, without dedicating separate evaluation sessions. If a policy’s Elo falls below a threshold

, it is evicted and replaced by a copy of a randomly chosen peer from the remaining

policies. During self-play,

and

remain active, while each other’s pseudo-reward is activated independently with probability

to regulate policy behavior. To reduce computational overhead, all

N policies share a single WM, which is trained on the aggregated replay buffer.

Finetuning

During fine-tuning, the agent with the highest final Elo rating is matched against the designated target opponent, but with probability

, the opponent is sampled from the population to maintain exposure to diverse strategies. Only

and

are active during finetuning, and the opponent embedding is initialized as a random vector [

11].

5. Experiments

We benchmark the performance of the proposed approach applied to each stage of the training pipeline as outlined in

Section 4.3. Based on experiment results, we seek to answer the following core research questions: compared to the model-free pure self-play baselines,

Policy Performance and Efficiency: Does a model-based approach produce stronger, more resilient policies, and do the reductions in sample complexity justify the additional computational cost?

Agression/Survival Tradeoff: To what extent can a constrained learning objective be used to balance an agent’s tendency for aggression versus survival?

Rapid Adaptation: Can the learned WM accelerate fine-tuning against novel opponents to a degree that is practical for real-world deployment?

We also perform an ablation study to assess the impact of each design choice in

Section 5.4.

All experiments use a discount factor

, which corresponds to a half-life of approximately 346 steps. Our agent includes a total of 10.7 M learnable parameters, matching the parameter count of a size XS DreamerV3 agent. As a model-free baseline, we choose a high-quality implementation of a PPO agent from the open-source CleanRL library [

53].

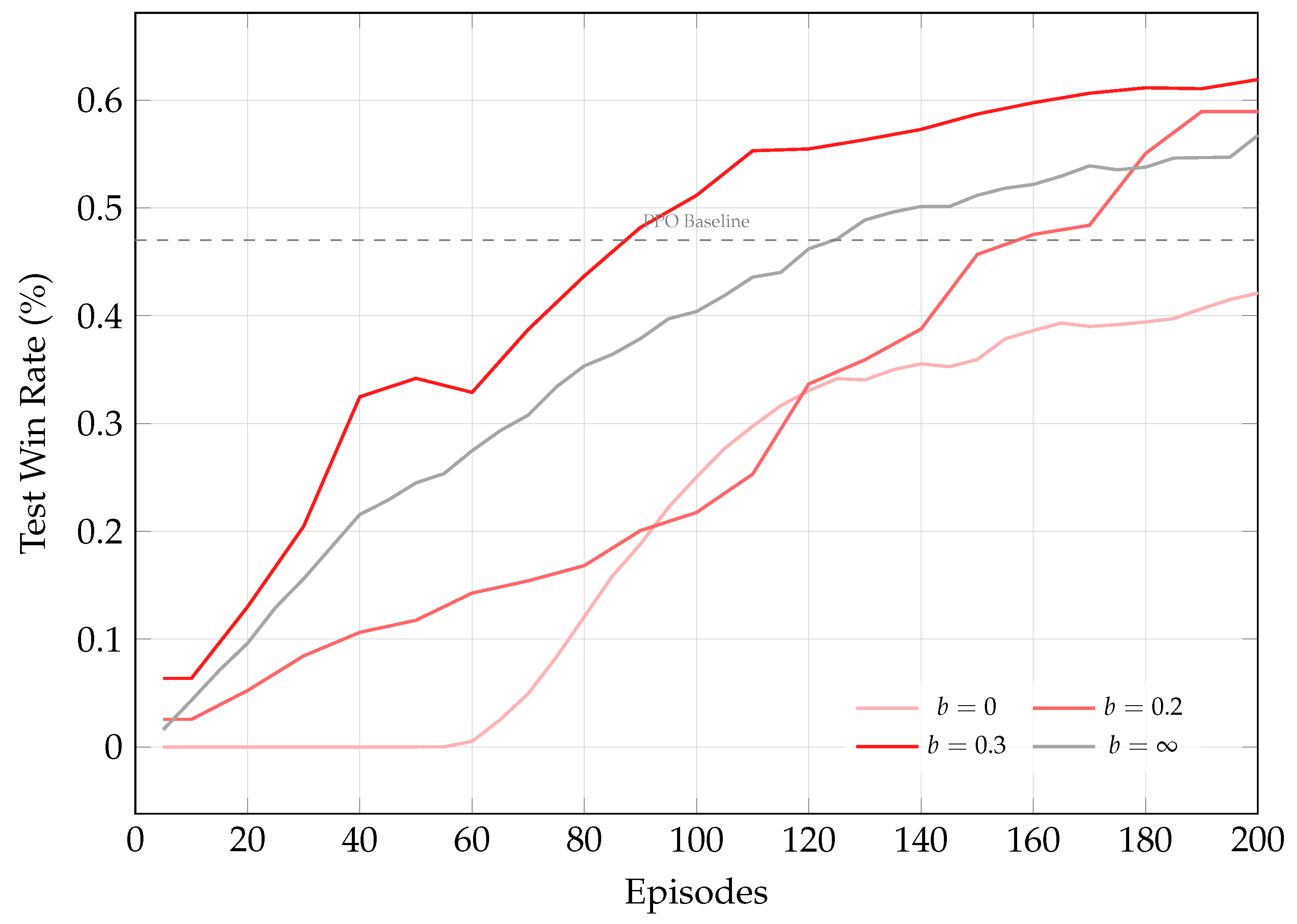

5.1. Curriculum Learning

To shed light on the first and second research questions, we first evaluate curriculum initialization under varying crash rate budgets

b and benchmark it against the PPO baseline, as shown in

Figure 5. The training is paused after every 10000 environment steps, during which 30 test episodes are run with a randomly chosen opponent from the curriculum pool. At the extreme

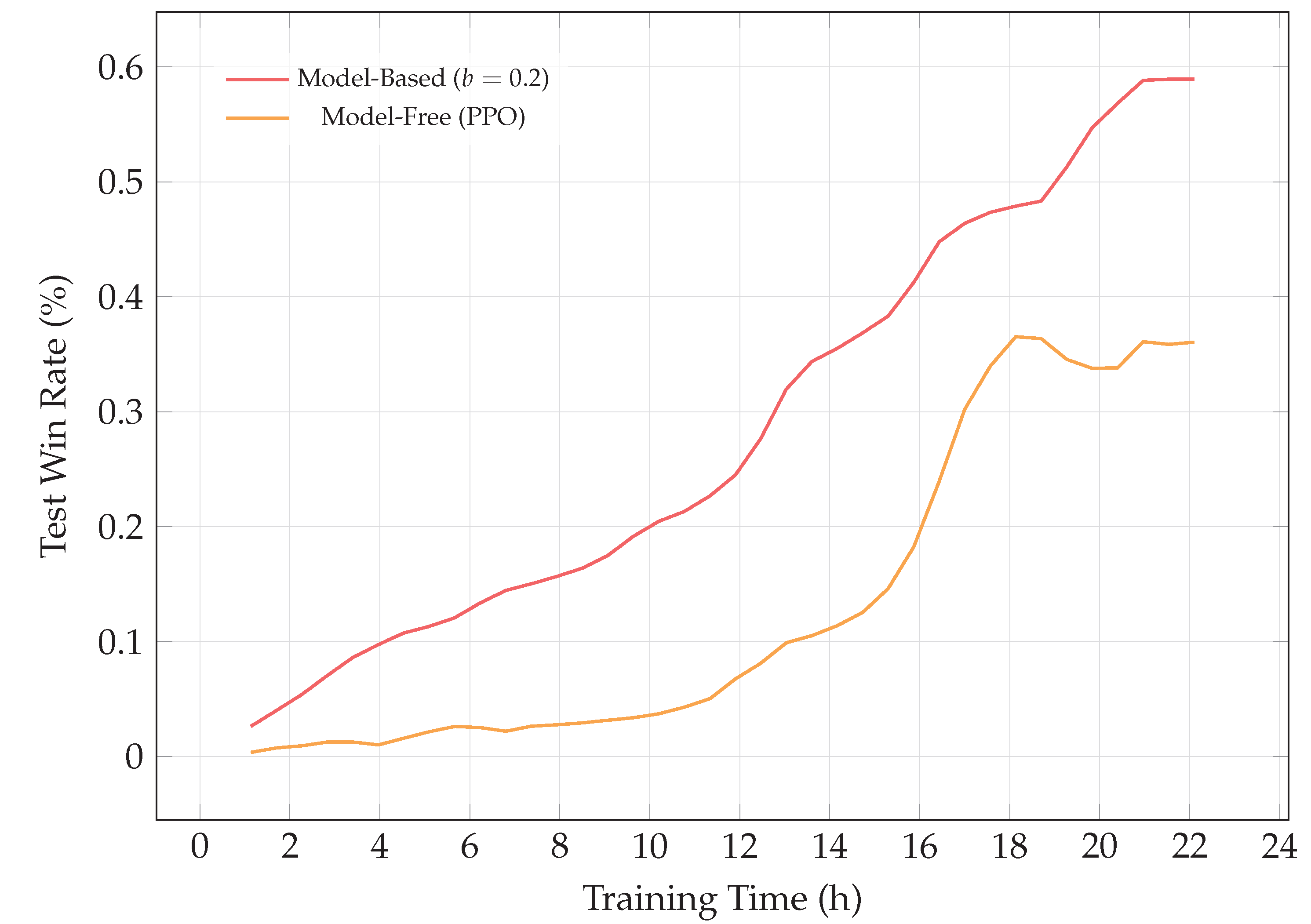

, the agent adopts a passive strategy, yielding fewer wins and frequent draws, which is consistent with our expectations. For moderate crash rate budgets, the agent swiftly matches the performance of the heuristic and under-trained learning-based opponents within 200 episodes, resulting in significantly higher exchange rates than training with an unlimited crush budget, while dramatically outperforming PPO in sample efficiency. When measured in wall-clock time as shown in

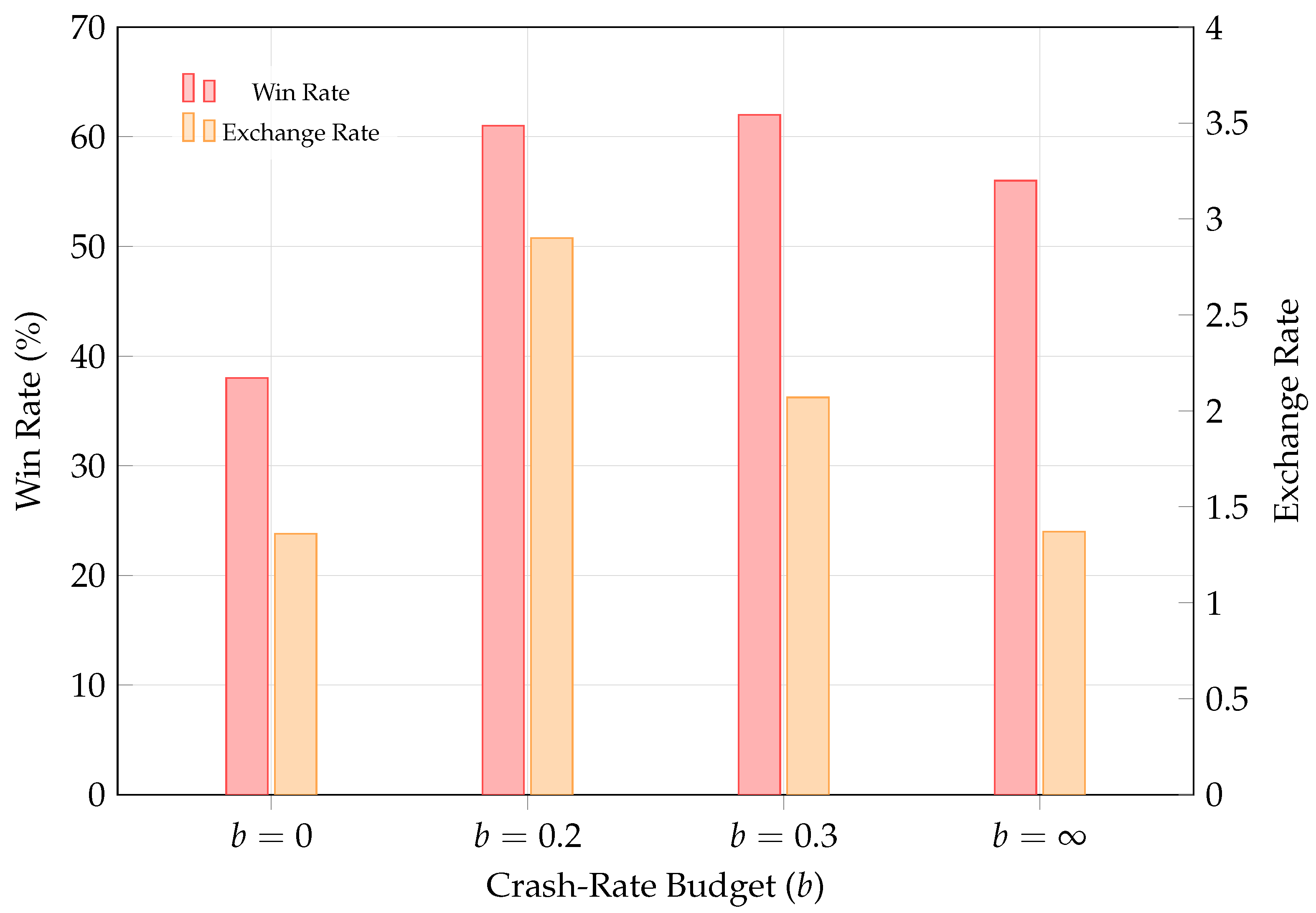

Figure 6, the margin narrows, but the model-based agent still outperforms PPO using a replay ratio of 512; lowering this ratio would further improve runtime at the cost of additional environment samples. The final performance of curriculum-trained agents are displayed in

Figure 7. In light of the preliminary results, we opt for a crash rate budget of

during self-play and fine-tuning, as it yields an agent with a satisfying win rate and the highest exchange rate.

5.2. Self-Play

We employ a population of

learning agents and inject three fixed PPO-trained opponents, all initialized at 1000 Elo.

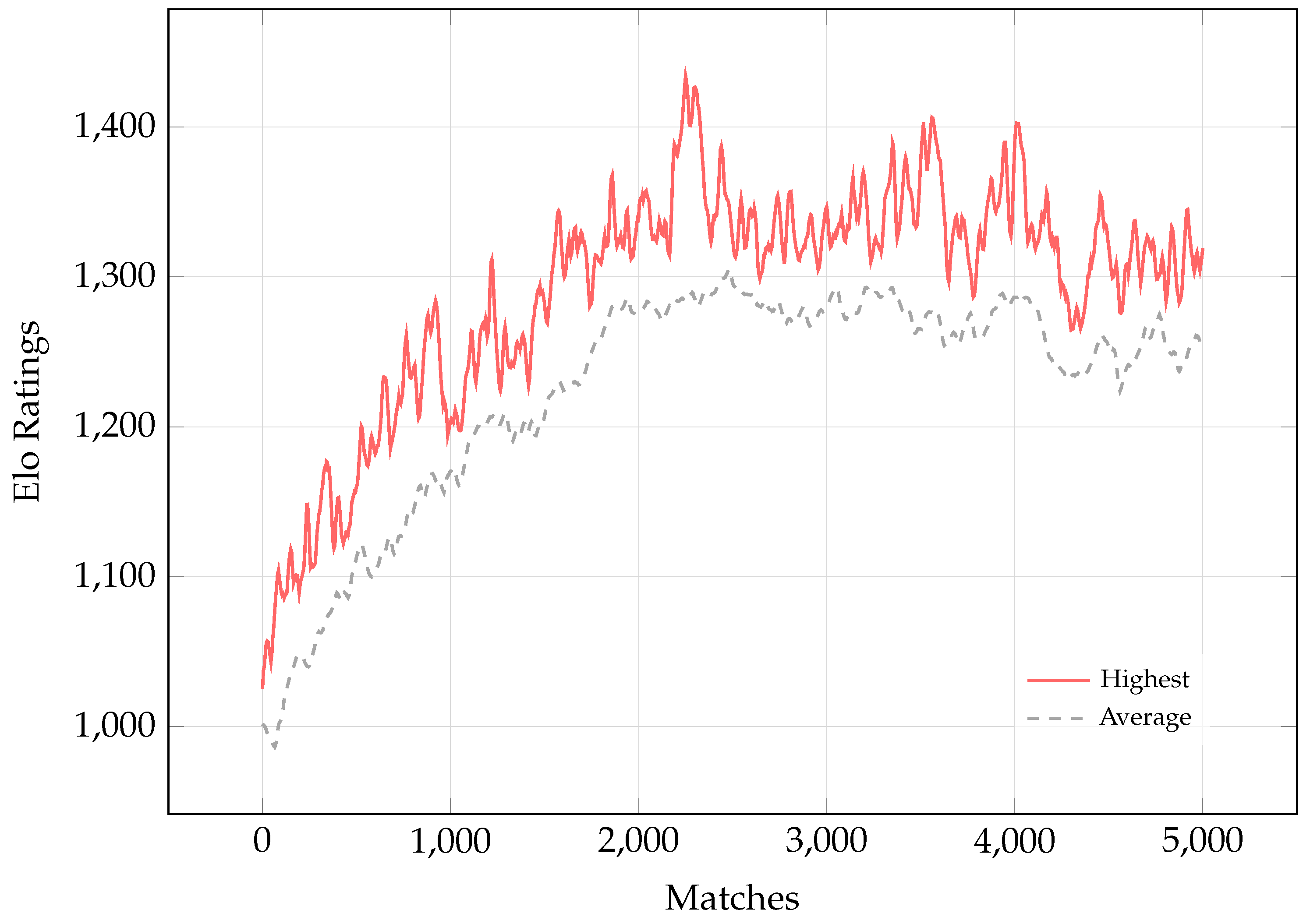

Figure 8 plots the maximum and mean Elo of the learning population over time. We observe a steady rise in Elo reaching a plateau around 1350. Beyond the limited rounds of self-play iterations, this stagnation likely stems from insufficient strategic diversity: lower-ranked agents tend to converge on diluted versions of the champion’s tactics, preventing further gains. We hypothesize that enforcing population diversity, so that agents discover non-transitive, complementary strategies, would sustain collective improvement. We leave the exploration of such diversity-promoting mechanisms to future work.

5.3. Zero-Shot Evaluation and Few-Shot Fine-Tuning

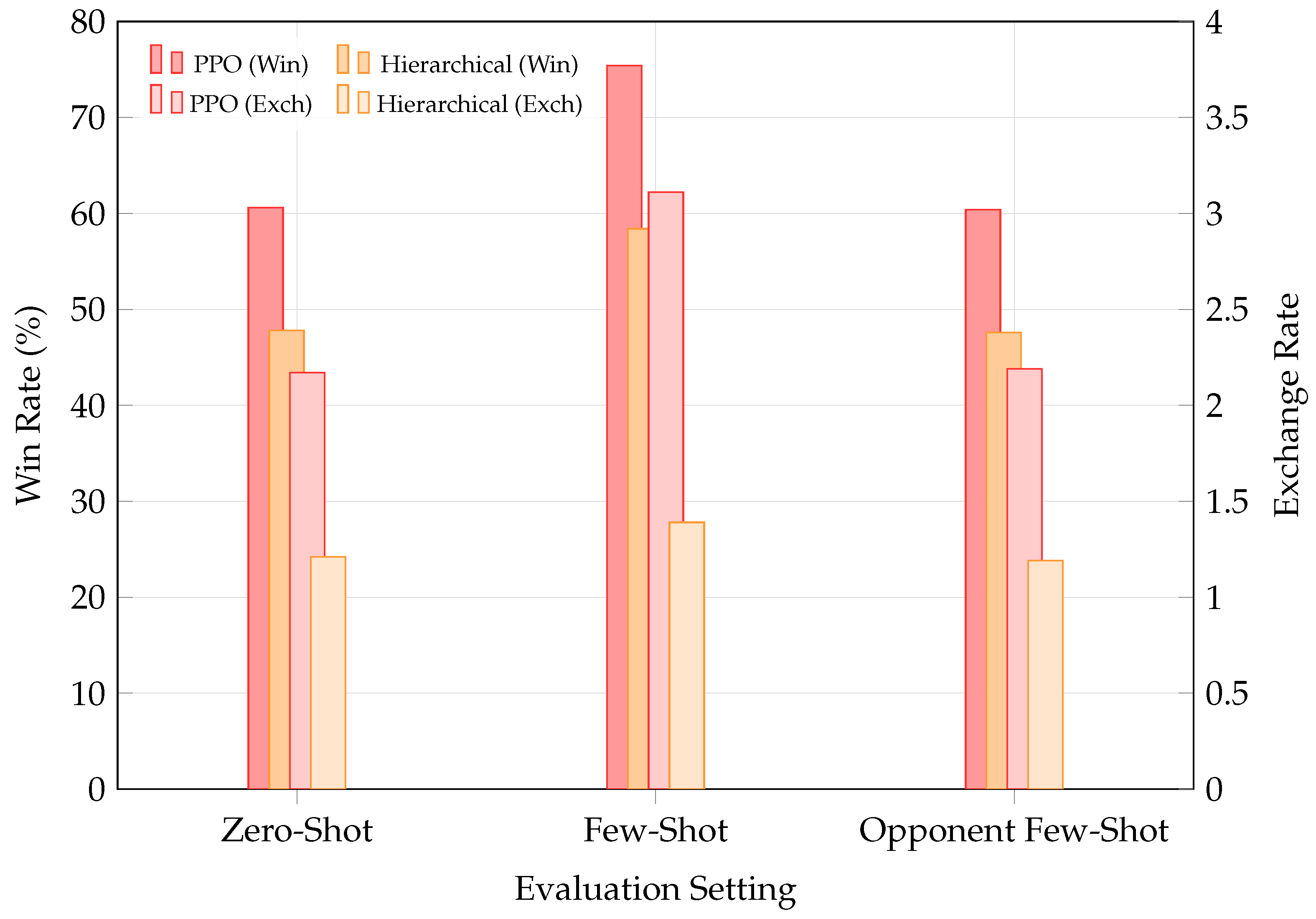

To address our final research question, we evaluate the pretrained model-based agent head-to-head against two benchmarks:

In the

zero-shot setting, each agent is tested against its opponent without any additional training. In the

few-shot setting, either our agent or the benchmark is fine-tuned for up to 50,000 transitions (approximately three hours of real-world experience) before facing the unmodified opponent.

Figure 9 reports the average win rate and exchange rate over 100 test episodes per opponent. Our agent demonstrates strong zero-shot performance against unseen opponents, and this performance improves substantially after a brief fine-tuning phase. In contrast, naive fine-tuning of the PPO baseline or the intra-option policy of the hierarchical agent [

54] yields negligible improvement against our agent. These findings highlight the robustness of our pipeline and the WM’s ability to rapidly adapt to specific opponents, approaching the sample efficiency required for real-world deployment.

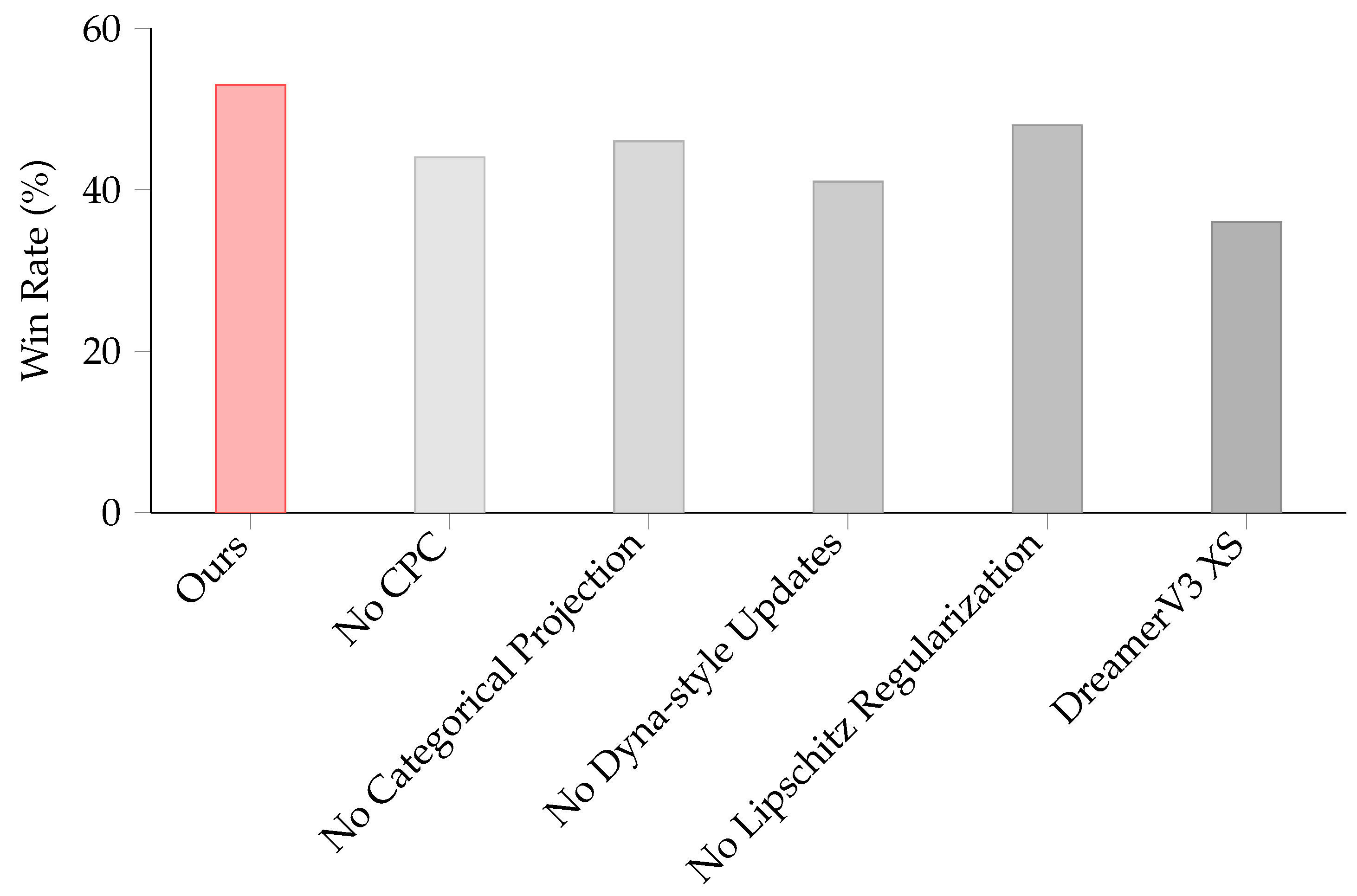

5.4. Ablation Studies

To validate our design choices, we conduct a series of ablation studies during the curriculum learning stage, systematically removing key components of our model to assess their impact on performance. The components evaluated include: contrastive predictive coding, categorical target projection, the Dyna-style mixing of real and imagined rollouts, and value-function Lipschitz regularization.

Figure 10 illustrates the win rates of the ablated models after 200 training episodes. The results unequivocally demonstrate that the removal of any single component leads to a degradation in performance. This confirms that each modification is integral to achieving the robustness and high performance of our single, monolithic policy.

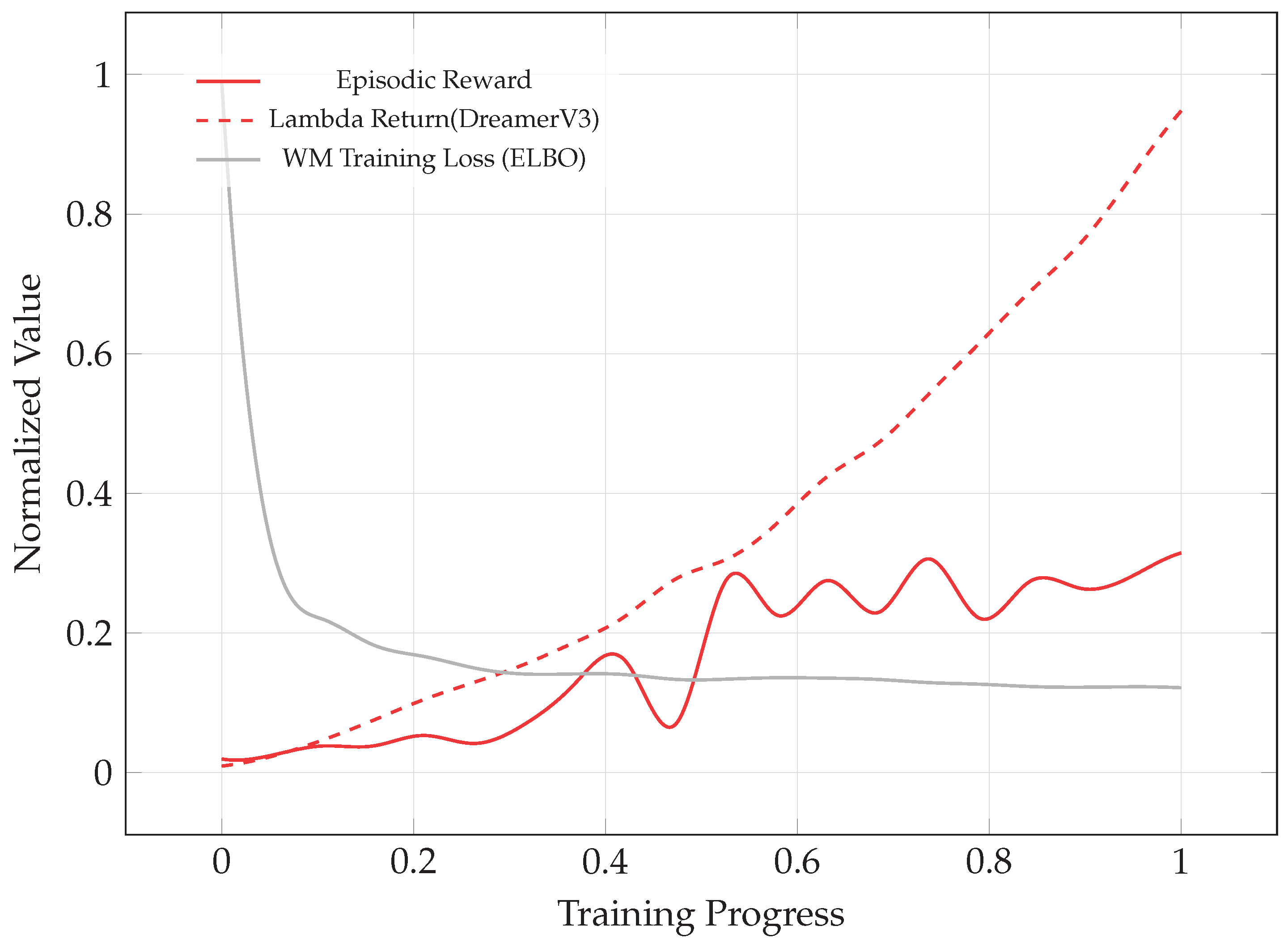

We further contextualize these findings by comparing our model to a vanilla DreamerV3-XS agent with a similar parameter count. The vanilla agent not only underperforms significantly but also falls behind a much simpler PPO baseline. This highlights a critical insight: state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks does not necessarily translate to robustness in complex, specialized domains. A common failure mode observed in the vanilla DreamerV3 agent is its tendency to settle on rudimentary tactics; for instance, it quickly learns basic evasion maneuvers in favorable scenarios but fails to discover more complex and effective tactics, such as the barrel roll or fake overshoot. Moreover, the agent sometimes exhibits a lack of sensitivity to imminent threats, often cruising idly into danger. We hypothesize that these shortcomings stem from the WM’s inaccuracy in predicting critical future states, which leads to value overestimation in dangerous situations.

A deeper investigation, illustrated in

Figure 11, substantiates this hypothesis. We observe a significant mismatch between the model’s training error as measured by the ELBO and the actual deviation in value predictions along imagined trajectories. For the vanilla DreamerV3 agent, the model-aware value error remains substantial even when the ELBO, a reconstruction-based metric, is optimized. This discrepancy confirms that relying solely on reconstruction losses can be misleading, as they do not adequately capture errors in long-term value prediction. In contrast, our incorporated features directly mitigate this issue: CPC module improves the WM’s sensitivity to termination events, categorical value distribution paired with Lipschitz regularization promotes smoother and more reliable value landscapes, while the Dyna-style blending of real and imagined rollouts provides corrective learning signals from ground-truth trajectories.

It is worth noting that the design of the population-based self-play pipeline, i.e., population initialization, policy conditioning, and the opponent sampling strategy, could also impact the agent’s final performance. Regrettably, due to substantial resource constraints, a thorough ablation of these self-play mechanics is deferred to future work.

Figure 11.

Discrepancy between imagined value and actual epsisodic return during curriculum learning of vanilla DreamerV3-XS agent. The lambda return of imagined trajectories serves as a proxy for the agent’s self-assessed performance. As the WM loss decreases, the model-based agent tends to overestimate its performance more rather than reduce this bias. Values are normalized for comparability.

Figure 11.

Discrepancy between imagined value and actual epsisodic return during curriculum learning of vanilla DreamerV3-XS agent. The lambda return of imagined trajectories serves as a proxy for the agent’s self-assessed performance. As the WM loss decreases, the model-based agent tends to overestimate its performance more rather than reduce this bias. Values are normalized for comparability.

6. Discussions and Future Directions

This work has introduced a modified Dreamer algorithm, enhanced with a self-play mechanism, to develop a single, end-to-end monolithic policy for the complex domain of automating within-visual-range air manuevers. Our model-based agent not only demonstrates robust zero-shot performance against diverse opponents but also shows amenability to rapid, gradient-based fine-tuning with minimal domain-specific knowledge. A key contribution of this research is demonstrating that by integrating a WM with a meticulously designed self-play pipeline, the expressiveness and performance of a learning-based monolithic policy can be significantly extended, challenging the prevailing view that such policies lag behind hierarchical baselines in this context.

Nevertheless, this study has two principal limitations. First, the scarcity of open-source implementations of leading hierarchical automated aerial agents prevented a direct, fair comparative analysis against State-of-the-Art solutions. Second, the substantial computational resources required for our experiments constrained this investigation to a JSBSim-level simulator.

Future research will focus on overcoming these limitations by scaling our approach to higher-fidelity simulations and, eventually, real-world platforms. Such efforts will be crucial to validating whether the robustness of our architecture and training methodology persists in genuinely operational environments. Ultimately, this research represents a significant step toward making scalable, stable reinforcement learning more accessible to non-practitioners in specialized fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tianyu Lu and Bing Chen; methodology, Tianyu Lu; software, Tianyu Lu; validation, Tianyu Lu; formal analysis, Tianyu Lu; investigation, Tianyu Lu; resources, Tianyu Lu; data curation, Tianyu Lu; writing—original draft preparation, Tianyu Lu; writing—review and editing, Tianyu Lu and Bing Chen; visualization, Tianyu Lu; supervision, Bing Chen; project administration, Tianyu Lu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant 62061146002 and Grant 62176122.

Data Availability Statement

The study relies exclusively on the open-source flight dynamics simulator JSBSim (

https://github.com/JSBSim-Team/jsbsim), which was used to generate all simulation data for training and evaluation. No proprietary or sensitive datasets were used. The training scripts supporting the reported results are available from the corresponding author upon request.

DURC Statement

Current research is limited to the field of autonomous control and reinforcement learning, which is beneficial for the development of intelligent decision-making algorithms and general-purpose simulation technologies. The study focuses on aerial maneuver games as abstract dynamic benchmarks for evaluating model-based reinforcement learning under high-dimensional and stochastic dynamics. It does not involve any real weapon systems, military data, or defense applications, and therefore poses no threat to public health or national security. Authors acknowledge the dual-use potential of research involving autonomous control and confirm that all necessary precautions have been taken to prevent potential misuse. As an ethical responsibility, authors strictly adhere to relevant national and international laws about DURC. The authors advocate for responsible deployment, ethical considerations, regulatory compliance, and transparent reporting to mitigate misuse risks and foster beneficial outcomes for society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or financial conflicts to disclose. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| MBRL |

Model-Based Reinforcement Learning |

| WVR |

Within-Visual-Range |

| DoF |

Degree-of-Freedom |

| MDP |

Markov Decision Process |

| WM |

World Model |

| RSSM |

Recurrent State Space Model |

| ELBO |

Evidence Lower Bound |

| CMDP |

Conditional Markov Decision Process |

| CPC |

Contrastive Predictive Coding |

| MI |

Mutual Information |

| InfoNCE |

Information Noise-Contrastive Estimation |

| EMA |

Exponential Moving Average |

| CVaR |

Conditional Value-at-Risk |

| MLP |

Multi-layer Perceptron |

| GELU |

Gaussian Error Linear Units |

| MoE |

Mixture-of-Experts |

| PPO |

Proximal Policy Optimization |

Appendix A. Aerial Manuever Game Environment Setup

Appendix A.1. Game Scenario and Rules

We evaluate two autonomous aircraft (red vs. blue) engaged in a close-range aerial pursuit-evasion task. Both agents are initialized under randomized conditions, including relative separation, headings, attitudes, altitudes, and body-frame velocities, all sampled uniformly from feasible flight envelopes.

Both agents attempt to maintain positional advantage by minimizing the line-of-sight (LOS) angle and distance to the opponent agent. At each simulation step, a continuous reward is assigned based on relative geometry:

where

is the relative distance,

is the angle between the pursuer’s forward axis and the line of sight, and

are weighting coefficients. This encourages the pursuer to stay close and aligned, and the evader to escape alignment.

Each encounter terminates when (1) the distance between aircraft exceeds the disengagement threshold , (2) one aircraft departs from the valid flight envelope, or (3) the elapsed time exceeds 1000s. At the end of the encounter, the aircraft with the higher accumulated reward wins.

Appendix A.2. Action Space of Aircraft Agent

We define two action levels:

Raw Action Space The low-level control action, which feeds directly into the simulator control interface

where

indexes evenly spaced bins for aileron, elevator, rudder (

) and throttle (

).

Hierarchical Action Space Directly learning

can be challenging due to its high dimensionality. Following [

55], we introduce a coarse high-level action space used by the model-based policy:

where

,

, and

select among roll angle, pitch angle, and velocity increments. These commands are concatenated with the ego-state and fed into a learned low-level policy network, which outputs

. The low-level controller is trained via Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO); The training recipe is provided in Appendix ??.

References

- Pope, A.P.; Ide, J.S.; Mićović, D.; Diaz, H.; Rosenbluth, D.; Ritholtz, L.; Twedt, J.C.; Walker, T.T.; Alcedo, K.; Javorsek, D. Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning for Air-to-Air Combat. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), 2021, pp. 275–284. [CrossRef]

- Orsula, A. Learning to Play Air Hockey with Model-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning, 2024, [arXiv:cs.RO/2406.00518]. [CrossRef]

- SoarTech. Automated Intelligent Pilots for Combat Flight Simulation. https://soartech.com/knowledge_center/, 1998.

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shi, G.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y. Maneuver decision of UAV in short-range air combat based on deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Gold, D.; Hagen, J.; Kochhar, A.K.; Lohn, A.J.; Osoba, O.A. Air dominance through machine learning. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DARPA. AlphaDogfight Trials Go Virtual for Final Event. https://www.darpa.mil/news/2020/alphadogfight-trials-final, 2020.

- Hu, D.; Yang, R.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. Application of deep reinforcement learning in maneuver planning of beyond-visual-range air combat. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32282–32297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Y.; Huang, C. Autonomous maneuver decision-making method based on reinforcement learning and Monte Carlo tree search. Frontiers in neurorobotics 2022, 16, 996412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, Q. A novel decision-making algorithm for beyond visual range air combat based on deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 37th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC). IEEE, 2022; pp. 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Hubert, T.; Simonyan, K.; Sifre, L.; Schmitt, S.; Guez, A.; Lockhart, E.; Hassabis, D.; Graepel, T.; et al. Mastering atari, go, chess and shogi by planning with a learned model. Nature 2020, 588, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, N.; Su, H.; Wang, X. TD-MPC2: Scalable, Robust World Models for Continuous Control, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2310.16828]. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, L.; Babaeizadeh, M.; Milos, P.; Osinski, B.; Campbell, R.H.; Czechowski, K.; Erhan, D.; Finn, C.; Kozakowski, P.; Levine, S.; et al. Model-Based Reinforcement Learning for Atari, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/1903.00374]. [CrossRef]

- Micheli, V.; Alonso, E.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are sample-efficient world models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00588 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mayne, D.Q. Model predictive control: Recent developments and future promise. Automatica 2014, 50, 2967–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulom, R. Efficient Selectivity and Backup Operators in Monte-Carlo Tree Search. In Proceedings of the Computers and Games (CG 2006); van den Herik, H.J.; Ciancarini, P.; Donkers, H.H.L.J., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; Vol. 4630, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 72–83. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computers and Games, Turin, Italy, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.; Calandra, R.; McAllister, R.; Levine, S. Deep reinforcement learning in a handful of trials using probabilistic dynamics models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depeweg, S.; Hernández-Lobato, J.M.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Udluft, S. Learning and policy search in stochastic dynamical systems with bayesian neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.07127 2016. [CrossRef]

- Moerland, T.M.; Broekens, J.; Jonker, C.M. Model-based Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. CoRR 2020, abs/2006.16712, [2006.16712]. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.L. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM Journal of research and development 2000, 44, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanctot, M.; Zambaldi, V.; Gruslys, A.; Lazaridou, A.; Tuyls, K.; Pérolat, J.; Silver, D.; Graepel, T. A unified game-theoretic approach to multiagent reinforcement learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Marris, L.; Hennes, D.; Merel, J.; Heess, N.; Graepel, T. NeuPL: Neural population learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.07415 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, Z.; Ma, C.; Yu, C.; Tu, W.W.; Tang, W.; Huang, S.; Ye, D.; Ding, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. A Survey on Self-play Methods in Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2408.01072]. [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. Stochastic Games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1953, 39, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman, M.L. Markov Games as a Framework for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 1994, pp. 157–163.

- Heinrich, J.; Lanctot, M.; Silver, D. Fictitious Self-Play in Extensive-Form Games. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; Bach, F.; Blei, D., Eds., Lille, France, 07–09 Jul 2015; Vol. 37, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 805–813.

- Silver, D.; Hubert, T.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Lai, M.; Guez, A.; Lanctot, M.; Sifre, L.; Kumaran, D.; Graepel, T.; et al. A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play. Science 2018, 362, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, D.; Pasukonis, J.; Ba, J.; Lillicrap, T.; et al. Mastering diverse control tasks through world models. Nature 2025, 640, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, R.S.; McAllester, D.; Singh, S.; Mansour, Y. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. Advances in neural information processing systems 1999, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, E. Constrained Markov decision processes; Routledge, 2021.

- Gu, S.; Yang, L.; Du, Y.; Chen, G.; Walter, F.; Wang, J.; Knoll, A. A review of safe reinforcement learning: Methods, theories and applications. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ji, J.; Xia, C.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y. SafeDreamer: Safe Reinforcement Learning with World Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2307.07176]. [CrossRef]

- Berndt, J. JSBSim: An open source flight dynamics model in C++. In Proceedings of the AIAA modeling and simulation technologies conference and exhibit, 2004, p. 4923.

- Oord, A.v.d.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.03748 2018. [CrossRef]

- Farebrother, J.; Orbay, J.; Vuong, Q.; Taïga, A.A.; Chebotar, Y.; Xiao, T.; Irpan, A.; Levine, S.; Castro, P.S.; Faust, A.; et al. Stop regressing: Training value functions via classification for scalable deep rl. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03950 2024. [CrossRef]

- Imani, E.; White, M. Improving regression performance with distributional losses. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018, pp. 2157–2166.

- Kapturowski, S.; Ostrovski, G.; Quan, J.; Munos, R.; Dabney, W. Recurrent experience replay in distributed reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International conference on learning representations, 2018.

- Peng, B.; Alcaide, E.; Anthony, Q.; Albalak, A.; Arcadinho, S.; Biderman, S.; Cao, H.; Cheng, X.; Chung, M.; Grella, M.; et al. Rwkv: Reinventing rnns for the transformer era. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13048 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Long, J.; Zhang, Y. Parallelizing Model-based Reinforcement Learning Over the Sequence Length. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Globerson, A.; Mackey, L.; Belgrave, D.; Fan, A.; Paquet, U.; Tomczak, J.; Zhang, C., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2024, Vol. 37, pp. 131398–131433.

- Zhang, B.; Sennrich, R. Root mean square layer normalization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. Gaussian error linear units (gelus). arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08415 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kogge, P.M.; Stone, H.S. A parallel algorithm for the efficient solution of a general class of recurrence equations. IEEE transactions on computers 2009, 100, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06450 2016. [CrossRef]

- As, Y.; Usmanova, I.; Curi, S.; Krause, A. Constrained policy optimization via bayesian world models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.09802 2022. [CrossRef]

- Espeholt, L.; Soyer, H.; Munos, R.; Simonyan, K.; Mnih, V.; Ward, T.; Doron, Y.; Firoiu, V.; Harley, T.; Dunning, I.; et al. Impala: Scalable distributed deep-rl with importance weighted actor-learner architectures. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018, pp. 1407–1416.

- Farahmand, A.M.; Barreto, A.; Nikovski, D. Value-Aware Loss Function for Model-based Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Singh, A.; Zhu, J., Eds. PMLR, 20–22 Apr 2017, Vol. 54, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 1486–1494.

- Zheng, R.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Huang, F. Is Model Ensemble Necessary? Model-based RL via a Single Model with Lipschitz Regularized Value Function. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572 2014. [CrossRef]

- Obando Ceron, J.S.; Sokar, G.; Willi, T.; Lyle, C.; Farebrother, J.; Foerster, J.N.; Dziugaite, G.K.; Precup, D.; Castro, P.S. Mixtures of Experts Unlock Parameter Scaling for Deep RL. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning; Salakhutdinov, R.; Kolter, Z.; Heller, K.; Weller, A.; Oliver, N.; Scarlett, J.; Berkenkamp, F., Eds. PMLR, 21–27 Jul 2024, Vol. 235, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 38520–38540.

- Puigcerver, J.; Riquelme, C.; Mustafa, B.; Houlsby, N. From Sparse to Soft Mixtures of Experts, 2024,. [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347 2017.

- Jaderberg, M.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Dunning, I.; Marris, L.; Lever, G.; Castaneda, A.G.; Beattie, C.; Rabinowitz, N.C.; Morcos, A.S.; Ruderman, A.; et al. Human-level performance in 3D multiplayer games with population-based reinforcement learning. Science 2019, 364, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Dossa, R.F.J.; Ye, C.; Braga, J.; Chakraborty, D.; Mehta, K.; Araújo, J.G. CleanRL: High-quality Single-file Implementations of Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhai, H.; Li, G. Hierarchical reinforcement learning with automatic curriculum generation for unmanned combat aerial vehicle tactical decision-making in autonomous air combat. Drones 2025, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, X. Light Aircraft Game: A lightweight, scalable, gym-wrapped aircraft competitive environment with baseline reinforcement learning algorithms. https://github.com/liuqh16/CloseAirCombat, 2022.

Short Biography of Authors

|

Tianyu Lu is an undergraduate student in the Department of Computer Science and Technology at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. His research focuses on decision intelligence and reinforcement learning, exploring model-based planning with real-world applications. He has served as a research assistant on projects involving autonomous systems and multi-agent coordination. |

|

Bing Chen received the B.S. and M.S. degrees in computer engineering from the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (NUAA), Nanjing, China, in 1992 and 1995, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from the College of Information Science and Technology, NUAA, in 2008. Since 1998, he has been with NUAA, where he is currently a Professor with the Department of Computer Science and Technology. His main research interests include AI security, federated learning, control policy, and the security of UAVs. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).