1. Introduction

Superior cerebellar artery (SCA) infarction represents a rare but clinically relevant subtype of posterior circulation stroke, accounting for less than 2% of all ischemic strokes and approximately 15% of cerebellar infarctions [

1,

2]. The SCA supplies the superior cerebellar hemispheres, the vermis and parts of the rostral brainstem and midbrain. Infarction in this territory typically presents with dizziness, ataxia, dysarthria, diplopia, skew deviation or sensory disturbances, but often spares the lower brainstem and cranial nerve nuclei, making early diagnosis challenging [

1,

3].

A critical complication of cerebellar stroke is malignant cerebellar edema, which may develop in 17–54% of cases and is associated with mortality rates of up to 80% without surgical intervention [

4]. In SCA infarction, swelling often causes downward compression of the brainstem rather than direct parenchymal involvement. This can mimic brainstem infarction on early computed tomography (CT) scans, potentially leading to premature treatment withdrawal [

3,

5,

6]. Differentiating true ischemia from reversible edema is therefore crucial for timely and appropriate therapeutic decisions.

CT remains the most widely used initial imaging modality in acute stroke due to its availability and speed. However, its sensitivity in the posterior fossa is limited because of beam-hardening artifacts and the compact anatomy of this region [

5,

6]. Hypodensity in the brainstem may reflect either true infarction or secondary mass effect from cerebellar swelling [

6]. MRI, particularly diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping, offers higher sensitivity for detecting infratentorial ischemia and can distinguish between cytotoxic edema and infarction [

5]. Early MRI evaluation is therefore essential in cases of suspected malignant cerebellar stroke to prevent misinterpretation and guide appropriate treatment.

Several clinical and radiological markers have been proposed to predict malignant course and poor outcome in cerebellar infarction. Volumetric thresholds—such as an infarct volume exceeding 25–30 mL or an infarct-to-posterior-fossa ratio > 0.25—have been associated with neurological deterioration and the need for early surgical intervention [

7,

8,

9]. Additional predictors include bilateral lesions, brainstem compression, and reduced level of consciousness at presentation [

8,

9,

10].

Despite this existing knowledge, specific evidence for SCA-territory infarctions remains scarce, as most studies combine SCA with Posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) and Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) infarctions. Given the unique topographic and radiological characteristics of SCA stroke, further synthesis of current evidence is warranted. This review therefore aims to: 1) illustrate a representative clinical case of malignant SCA infarction, 2) provide a structured synthesis of the literature published since 2015, and 3) discuss diagnostic and therapeutic implications with a particular focus on imaging-based decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Documentation

Clinical, radiological and therapeutic data of a patient with acute ischemic stroke in the SCA territory were retrospectively analyzed. Neuroimaging included non-contrast cranial CT, MRI sequences—DWI, ADC, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and time-of-flight angiography (TOF)—as well as digital subtraction angiography (DSA). The diagnostic process, therapeutic decisions, and clinical course were thoroughly documented and jointly reviewed by a neurologist, neuroradiologist and neurosurgeons. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s next of kin. Approval by the local ethics committee was waived for publication of a case report.

2.2. Literature Review Methodology

A systematic literature search was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines, incorporating predefined eligibility criteria, a structured screening process and transparent reporting of included and excluded studies.

The search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, covering publications from 1 January 2015 onward. The strategy targeted studies reporting imaging findings, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches in patients with space-occupying cerebellar infarctions involving the SCA territory—either isolated or as part of mixed cerebellar stroke cohorts.

The following search terms were used:

“superior cerebellar artery infarction” OR “SCA stroke” OR “cerebellar infarction” OR “posterior fossa infarction” AND “malignant cerebellar infarction” OR “decompressive craniectomy” OR “ventricular drainage” OR “computed tomography” OR “magnetic resonance imaging”.

Search results were imported into a reference management system and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text evaluation of potentially eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria were:

1) adult patients with cerebellar infarction involving the SCA territory,

2) availability of imaging and/or clinical data relevant to diagnosis, prognosis, or surgical management, and

3) original clinical or radiological data.

Exclusion criteria included non–space-occupying infarctions, pediatric populations, experimental or animal studies and single case reports lacking clinically relevant outcome data.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data from each included study were systematically extracted using a structured template capturing authorship, year of publication, study design, imaging modality, infarct location (SCA vs. other cerebellar territories), prognostic variables and reported outcomes. Due to methodological and clinical heterogeneity, a quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a qualitative synthesis was performed, structured around four thematic domains:

Imaging characteristics, including CT–MRI comparisons, volumetric assessments and posterior fossa ratios;

Prognostic markers, such as infarct volume, brainstem involvement and bilateral cerebellar lesions;

Therapeutic strategies, covering timing of intervention, decompressive surgery, ventricular drainage and minimally invasive techniques;

Functional outcomes, including reported recovery patterns and long-term neurological status.

This thematic framework was chosen to provide a clinically relevant synthesis of diagnostic and prognostic factors that inform treatment decisions in malignant SCA infarction.

3. Results

3.1. Illustrative Case

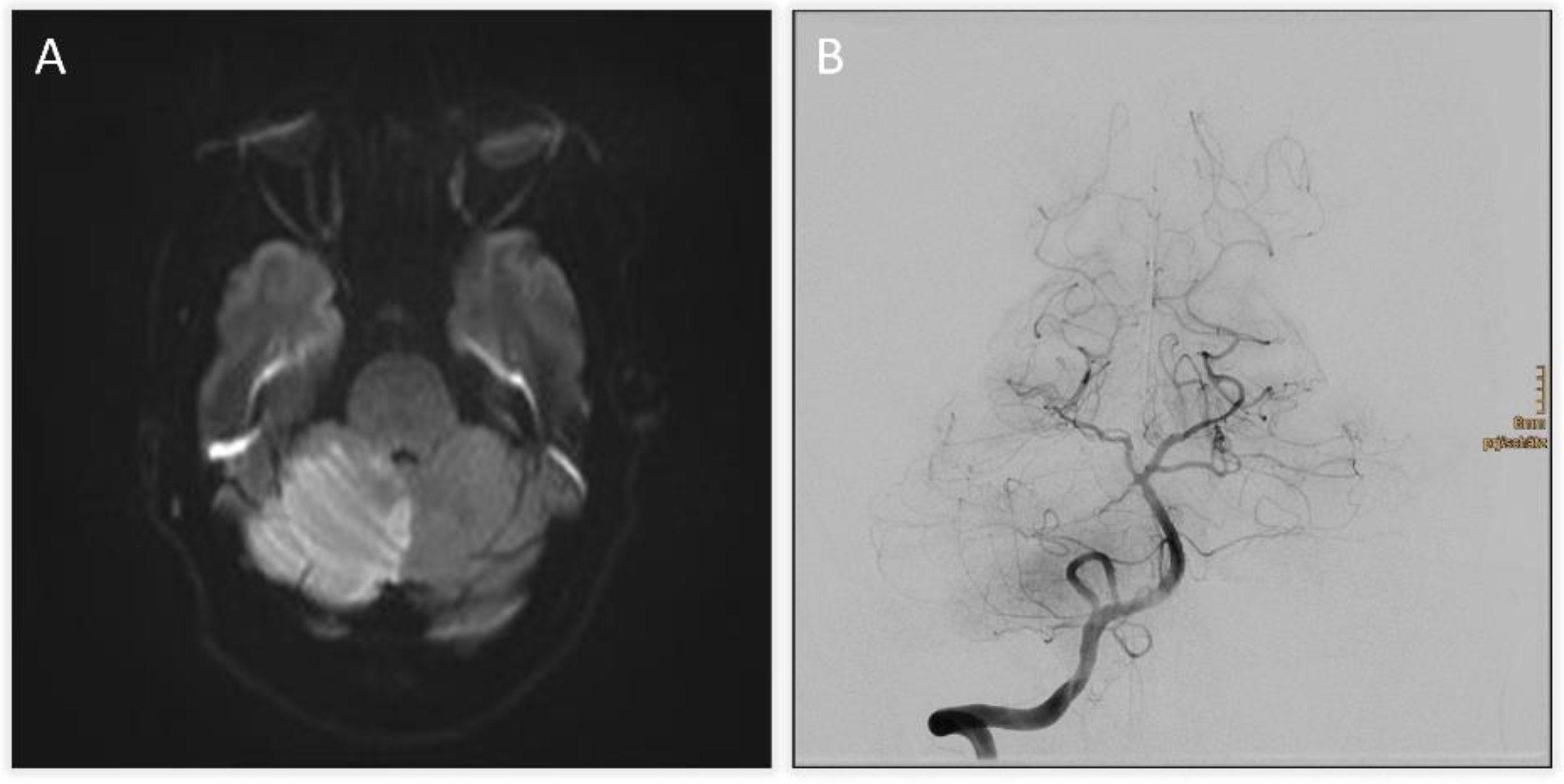

A 50-year-old woman with no prior medical history presented with acute severe vertigo, dysphagia, dysarthria, and diplopia. Neurological examination revealed skew deviation, left-sided hemihypesthesia, bilateral bradykinesia, and ataxia (NIHSS score 7). Initial diffusion-weighted MRI showed acute ischemia of the right cerebellum and vermis (

Figure 1A).

TOF-angiography identified a thrombus at the basilar tip. Intravenous thrombolysis was administered, followed by DSA confirming right SCA occlusion with preserved basilar patency (

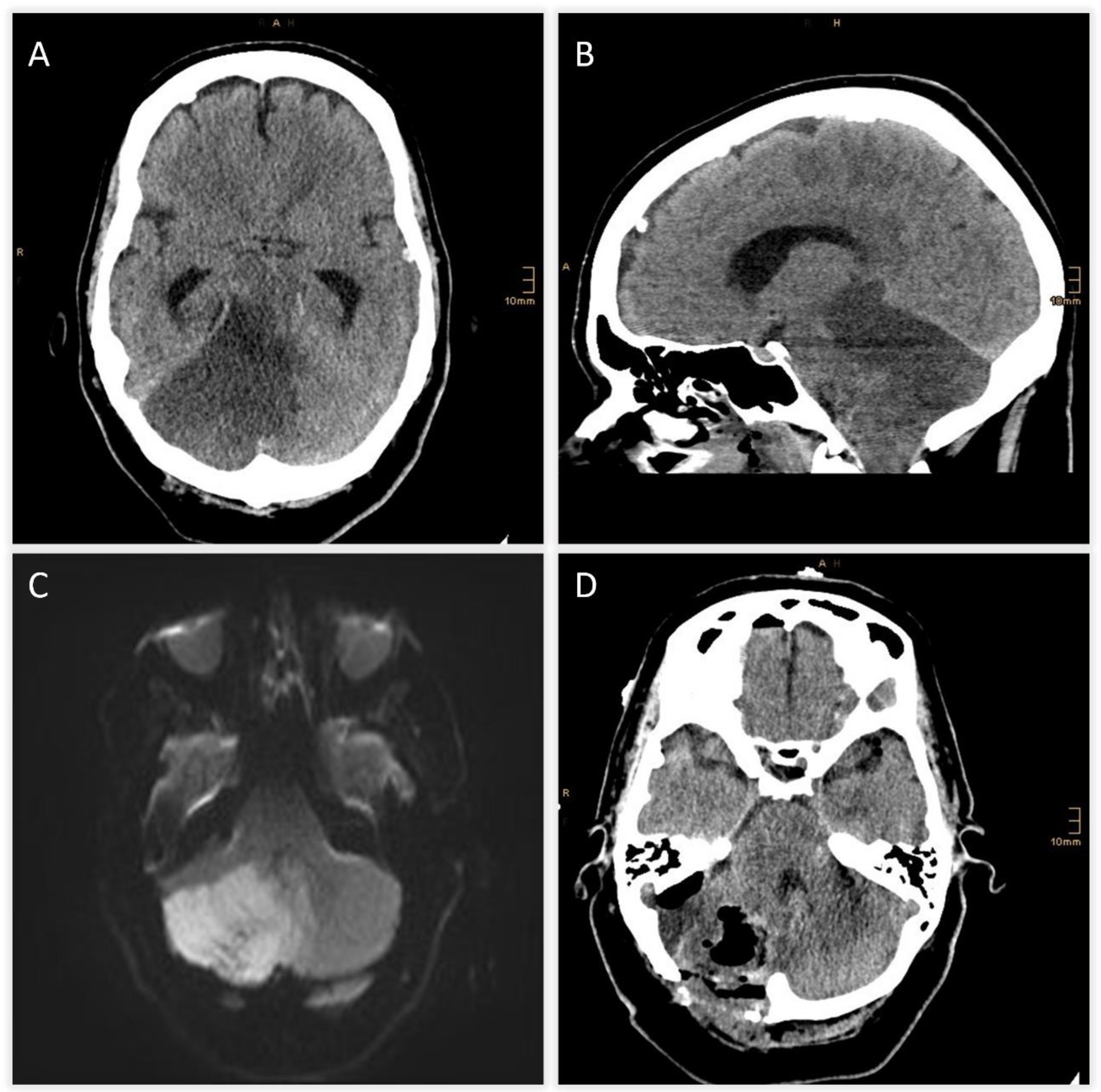

Figure 1B). Mechanical thrombectomy was attempted but unsuccessful. Follow-up CT revealed extensive hypodensity in the right cerebellum with mass effect and apparent extension into the brainstem, raising concern for infarction and poor prognosis (

Figure 2A and

Figure 2B). Immediate MRI, however, excluded brainstem infarction and confirmed predominantly reversible edema (

Figure 2C). Emergency suboccipital decompression, partial resection of infracted parenchyma and ventricular drainage were performed (

Figure 2D).

The patient was extubated after 10 days. Further etiological work-up revealed a patent foramen ovale with atrial septal aneurysm, which was treated by interventional cardiology. A detailed timeline of clinical events and interventions is provided in

Table 1.

3.2. Review of the Literature

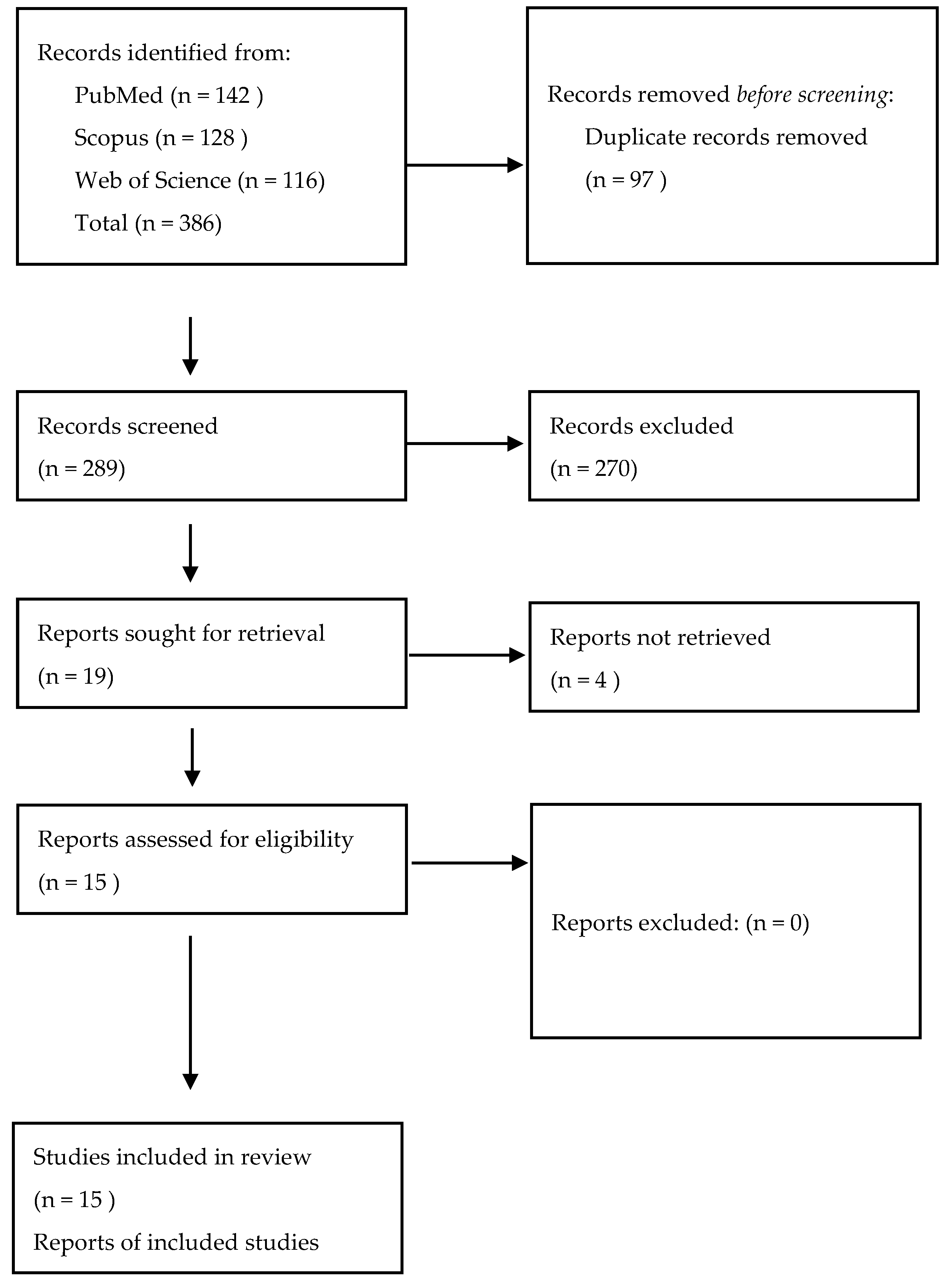

Initial literature screening yielded 386 records. After removal of 97 duplicates, 289 studies remained for title and abstract screening. A total of 270 studies were excluded because they did not meet the predefined eligibility criteria.

Nineteen full-text articles were retrieved for detailed assessment. Four were excluded due to insufficient imaging or clinical data relevant to the study objectives.

Ultimately, 15 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis (

Figure 3).

3.2.1. Study Characteristics

A total of fifteen studies published between 2016 and 2025 met the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. Thirteen were retrospective observational studies, three of which were multicenter in design. Two additional systematic reviews were incorporated. Together, these studies provided a comprehensive overview of the diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic aspects of space-occupying cerebellar infarctions involving the SCA territory.

3.2.2. Diagnostic Imaging

Initial brain CT is often performed in patients with suspected SCA infarction; however, CT has limited sensitivity in detecting posterior fossa strokes, particularly in the brainstem region. Several studies emphasized the diagnostic value of MRI—especially diffusion-weighted imaging—for confirming cerebellar infarction and identifying brainstem involvement when CT findings are inconclusive. Kim et al. (2016) reported that MRI was crucial for detecting brainstem infarcts in cases where CT findings did not align with clinical symptoms. Similarly, Kapapa et al. (2024) found that although 60% of patients underwent CT initially, MRI was required in 40% to establish the diagnosis. MRI consistently revealed the true extent of ischemia in the SCA territory, which CT often underestimated. These findings underscore the importance of early MRI in guiding management when CT results are equivocal or show only subtle changes.

3.2.3. Prognostic Factors

Infarct volume emerged as the most consistent and clinically relevant prognostic marker across nearly all studies. Baki et al. (2025) and Kapapa et al. (2024) identified critical volumetric thresholds between 31 and 38 cm3—or an infarct-to-posterior fossa ratio greater than 0.25—that were strongly associated with malignant edema and neurological deterioration. Won et al. (2024), analyzing a large multicenter cohort, reported improved survival with surgical decompression in patients whose infarct volumes exceeded 35 mL. Hernández-Durán et al. (2024) showed that early infarct volume reduction correlated with better functional outcomes, highlighting the importance of timely intervention.

In contrast, Goulin Lippi Fernandes et al. (2022) found that neither surgical timing nor the degree of mass effect alone reliably predicted outcomes, reinforcing the greater prognostic utility of volumetric assessment. Additional studies (Kim 2016; Suyama 2019; Villalobos-Díaz 2022) emphasized that clinical presentation—particularly low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and the presence of hydrocephalus—was also predictive of outcome and essential for surgical decision-making. Lucia et al. (2023) specifically found that patients with preoperative GCS scores of 12–15 experienced significant benefit from early suboccipital decompression (SDC).

3.2.4. Surgical Management and Timing

Suboccipital decompressive craniectomy (SDC) was consistently reported as an effective and often lifesaving, intervention for managing large cerebellar infarctions with mass effect. Kim et al. (2016) demonstrated that early, preemptive SDC (performed within approximately 72 hours of symptom onset, before clinical deterioration) led to significantly better 12-month outcomes, with 67% of patients achieving functional independence (modified Rankin Scale score 0–2) and lower mortality compared to medically managed controls.

A systematic review by Ayling et al. (2017) reported favorable outcomes across pooled data, with a mortality rate of ~20% and most survivors retaining good to moderate functional status. External ventricular drainage (EVD) was commonly employed in conjunction with SDC, particularly to manage obstructive hydrocephalus. Hernández-Durán et al. (2025) found that 86% of neurosurgical centers routinely used EVD during SDC procedures for cerebellar stroke. Meta-analytic data suggested that higher EVD usage was associated with reduced mortality by Ayling et al. (2017). Larger infarcts were more likely to undergo surgical intervention, with mean infarct volumes around 53 cm3 in surgically treated patients versus 26 cm3 in those treated conservatively. Volume thresholds of ~30–31 cm3 were frequently cited as indicative of high risk for deterioration, warranting decompression.

Importantly, the presence of concurrent brainstem infarction was not regarded as a contraindication for surgery, although patients without brainstem involvement tended to have more favorable outcomes showed by Kim et al. (2016). Across studies, the best outcomes were consistently observed when SDC (often combined with EVD) was performed early—before irreversible brainstem compression or deep coma occurred.

3.2.5. Minimally Invasive and Endoscopic Alternatives

Several studies explored less invasive surgical strategies aimed at reducing the morbidity associated with open craniectomy. Mostofi et al. (2024) compared traditional SDC with a minimally invasive endoscopic necrosectomy (MEN) technique and found similar postoperative neurological improvements in both groups. The endoscopic approach offered procedural advantages, including shorter operative time and faster wound healing due to the use of a keyhole craniectomy.

Hernández-Durán et al. (2020) reported comparable outcomes using a limited osteoplastic suboccipital craniotomy with direct infarct removal (cerebellar necrosectomy), achieving good functional outcomes in 76% of cases (Glasgow Outcome Scale ≥4) and a 30-day mortality rate of 21%. Additionally, this technique appeared to lower the risk of complications such as infection or CSF leakage by preserving the bone flap and avoiding wide dural opening.

Table 2.

summary of the key findings from the reviewed studies.

Table 2.

summary of the key findings from the reviewed studies.

| First Author |

Year |

Title (short) |

Study Type |

Population |

Key Findings |

| Ayling OGS |

2018 |

Suboccipital decompression for cerebellar infarction |

Systematic review / meta-analysis |

Cerebellar infarction |

SDC is associated with better outcomes compared with decompressive surgery for hemispheric infarctions |

| Baki E |

2025 |

Predictors of malignant swelling |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Infarct volume > 38 cm3 is associated with a swelling rate of >50% |

| Baek BH |

2023 |

SCA occlusion after thrombectomy |

Retrospective cohort |

SCA infarction |

Attempts to recanalize remnant SCA occlusion may be unnecessary after basilar artery thrombectomy. |

| Goulin Lippi Fernandes E |

2022 |

Volumetric analysis and outcomes |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Surgical timing, including preventive surgery and mass effect of the infarct, in the posterior fossa is not predictive of the patients’ functional outcomes. |

| Hernández-Durán S |

2020 |

Cerebellar necrosectomy vs decompression |

Retrospective cohort |

Malignant cerebellar infarction |

No significant differences between mortalitiy or functional outcomes |

| Hernández-Durán S |

2024 |

Surgical infarct volume reduction and outcomes |

Retrospective multicenter cohort |

Malignant cerebellar infarction |

Early infarct volume reduction associated with better functional outcomes |

| Kapapa T |

2024 |

Volumetry as a criterion for decompression |

Retrospective multicenter cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Volumetric cut-of >31 cm3 is more probable for decompression |

| Kim MJ |

2016 |

Preventive vs reactive suboccipital decompression |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Favorable clinical outcomes including overall survival can be expected after preventive SDC in patients with a volume ratio between 0.25 and 0.33 |

| Lindeskog D |

2019 |

Long-term outcome after decompression |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

After SDC, half of the patients achieved a functionally acceptable level (mRS 0–3) at 12-month follow-up |

| Lucia K |

2023 |

Predictors of clinical outcomes |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Patients with space-occupying cerebellar infarction and a preoperative GCS of 12–15 significantly benefit from early SDC |

| Mostofi K |

2024 |

Craniectomy vs endoscopic surgery |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Endoscopic vacuation of

necrotic tissue is a promising alternative to decompressive craniectomy with comparable clinical outcomes. |

| Suyama Y |

2019 |

Significance of decompression |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Early DSC should be considered for treating cerebellar infarction in patients with GCS 13 or worse |

| Villalobos-Díaz R |

2022 |

Long-term outcomes of cerebellar strokes |

Retrospective cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

GCS and hydrocephalus are crucial factors in therapeutic decision-making |

| Won SY |

2024 |

Surgical vs conservative treatment |

Retrospective multicenter cohort |

Cerebellar infarction |

Surgery beneficial for infarcts >35 mL |

| Yoh N |

2023 |

Minimally invasive evacuation |

Systematic review and case series |

Spontaneous cerebellar hemorrhage |

Minimally invasive evacuation is safe and effective. |

4. Discussion

SCA infarction represents a rare but clinically significant subtype of posterior circulation stroke [

1,

2]. Its distinct vascular supply and predilection for the upper cerebellum and rostral brainstem lead to variable and sometimes deceptive imaging findings. As highlighted in previous work, early differentiation between primary brainstem infarction and secondary compression from cerebellar edema is vital, since management and prognosis differ substantially [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The present synthesis, together with the illustrative case, emphasizes the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of malignant SCA infarction. In the reported patient, initial CT suggested extensive brainstem involvement, raising concern for irreversible injury and poor prognosis. However, subsequent MRI demonstrated that the apparent hypodensity represented predominantly vasogenic edema rather than cytotoxic infarction—an observation that directly altered the clinical course by prompting timely decompressive surgery. This diagnostic pitfall underscores the limitations of CT in the posterior fossa, where beam-hardening artifacts and partial-volume effects can obscure subtle differences between infarction and swelling.

Across the reviewed literature, infarct volume emerged as the most robust and reproducible prognostic parameter. Thresholds above 30–35 mL, or an infarct-to-posterior-fossa ratio exceeding 0.25, consistently predicted malignant edema and neurological decline [

7,

9,

14]. Early SDC, particularly in patients with preserved consciousness (GCS ≥ 12), was associated with favorable functional outcomes and reduced mortality [

8,

12,

18]. Conversely, delayed or purely conservative management often resulted in rapid deterioration due to progressive brainstem compression. The case presented here aligns with these findings, supporting early surgical intervention once mass effect becomes evident.

Suboccipital decompressive craniectomy, with or without ventricular drainage, remains the cornerstone of therapy in space-occupying cerebellar infarction [

4,

7,

8,

11]. More recently, minimally invasive and endoscopic approaches have emerged as potential alternatives, but current evidence remains limited [

12,

13,

14].

However, some authors have cautioned that preemptive decompression may expose patients to surgical risks who might otherwise have had a benign course. Reported complication rates of suboccipital decompression—including CSF leakage, wound infection, and postoperative hydrocephalus—range approximately from 10–25% in contemporary series, underscoring the need for careful selection and volumetric thresholds to avoid overtreatment [

15,

24].

Emerging minimally invasive approaches, including endoscopic or osteoplastic necrosectomy, offer potential advantages in selected patients by minimizing surgical trauma and promoting faster recovery [

11,

13,

26]. However, evidence remains limited and these techniques should currently be considered complementary rather than replacements for standard SDC. Their use may be particularly justified in patients with moderate edema and localized necrosis, but not as substitutes for decompression in space-occupying lesions with threatened brainstem herniation.

Notably, compared with PICA or AICA territory infarctions, SCA infarctions more often present with isolated cerebellar swelling and downward brainstem compression while less frequently showing primary brainstem ischemia on definitive imaging. This topographic distinction—also reflected in several of the included cohorts—supports analyzing SCA infarctions separately rather than pooling them with other cerebellar territories for prognostic and therapeutic decision-making [

7,

10,

14].

Taken together, current evidence and the illustrative case converge on a crucial diagnostic principle: in SCA infarction, a hypodense brainstem on CT does not necessarily indicate infarction. Whenever CT suggests brainstem involvement or when clinical findings and imaging appear discordant, urgent MRI—preferably with diffusion-weighted and ADC sequences—must be performed. Only MRI can reliably distinguish between cytotoxic edema and infarction and thereby guide life-saving surgical decision-making [

5,

6].

5. Conclusions

SCA infarction is a rare but diagnostically challenging posterior circulation stroke. Due to its anatomy, cerebellar swelling can cause downward brainstem compression that mimics primary brainstem infarction on CT, risking misdiagnosis and premature treatment withdrawal. MRI—particularly diffusion and perfusion imaging—offers critical diagnostic clarity by distinguishing true infarction from reversible edema. Volumetric and topographic assessments support timely surgical decisions, with early decompressive craniectomy, with or without ventricular drainage, remaining the mainstay of treatment. Minimally invasive and endoscopic techniques show potential but require further validation. Future studies should focus on defining standardized imaging thresholds and refining criteria for patient selection. In all cases with suspected brainstem involvement, early MRI and a structured, interdisciplinary approach are essential to improving outcomes in malignant SCA infarction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and B.A.; methodology, M.G. and T.R.; validation, A.H., formal analysis, M.G and K.A.; investigation, .T.R and K.A..; resources, A.G.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., B.A., T.R, V.S., G.S., A.H. and K.A; writing—review and editing, B.A.; M.G., T.R, and K.A, visualization, M.G, K.A., V.S. and E.H,.; supervision, A.G and K.A..; project administration, M.G. and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for publication, including all clinical data and imaging, was obtained from the patient’s next of kin in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Johannes Kepler University Linz.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication, including all clinical data and imaging, was obtained from the patient’s next of kin in accordance with institutional and journal guidelines. Approval by the local ethics committee was waived for publication of a case report.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC |

Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AICA |

Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| DSA |

Digital Subtraction Angiography |

| DWI |

Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| EVD |

External ventricular drainage |

| FLAIR |

Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| MEN |

Minimally invasive endoscopic necrosectomy |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NIHSS |

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| PICA |

Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery |

| PFO |

Patent Foramen Ovale |

| PWI |

Perfusion-Weighted Imaging |

| SANRA |

Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

| SCA |

Superior Cerebellar Artery |

| TOF |

Time-of-Flight (angiography) |

References

- Ortiz de Mendivil, A.; Alcalá-Galiano, A.; Ochoa, M.; Salvador, E.; Millán, J.M. Brainstem stroke: Anatomy, clinical and radiological findings. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2013, 34, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines. Stroke. 2019, 50, e344–e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsava, E.M.; Helenius, J.; Avery, R.; Sorgun, M.H.; Kim, G.M.; Pontes-Neto, O.M.; et al. Assessment of the Predictive Validity of Etiologic Stroke Classification. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijdicks, E.F.; Sheth, K.N.; Carter, B.S.; Greer, D.M.; Kasner, S.E.; Kimberly, W.T.; et al. Recommendations for the management of cerebral and cerebellar infarction with swelling. Stroke. 2014, 45, 1222–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazzelli, M.; Sandercock, P.A.; Chappell, F.M.; Celani, M.G.; Righetti, E.; Arestis, N.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging versus Computed Tomography for Detection of Acute Vascular Lesions in Patients Presenting with Stroke Symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 4, CD007424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauss, M.; Müffelmann, B.; Krieger, D.; Zeumer, H.; Busse, O. A Computed Tomography Score for Assessment of Mass Effect in Space-Occupying Cerebellar Infarction. J Neuroimaging. 2001, 11, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapapa, T.; Pala, A.; Alber, B.; Mauer, U.M.; Harth, A.; Neugebauer, H.; et al. Volumetry as a Criterion for Suboccipital Craniectomy after Cerebellar Infarction. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, K.; Reitz, S.; Hattingen, E.; Steinmetz, H.; Seifert, V.; Czabanka, M. Predictors of clinical outcomes in space-occupying cerebellar infarction undergoing suboccipital decompressive craniectomy. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1165258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, E.; Baumgart, L.; Kehl, V.; Hess, F.; Wolff, A.W.; Wagner, A.; et al. Predictors of malignant swelling in space-occupying cerebellar infarction. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2025, 10, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Park, S.K.; Song, J.; Oh, S.Y.; Lim, Y.C.; Sim, S.Y.; et al. Preventive Suboccipital Decompressive Craniectomy for Cerebellar Infarction: A Retrospective-Matched Case-Control Study. Stroke. 2016, 47, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, N.; Abou-Al-Shaar, H.; Bethamcharla, R.; Beiriger, J.; Mallela, A.N.; Connolly, E.S.; Sekula, R.F. Minimally invasive surgical evacuation for spontaneous cerebellar hemorrhage: A case series and systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2023, 46, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeskog, D.; Lilja-Cyron, A.; Kelsen, J.; Juhler, M. Long-Term Functional Outcome after Decompressive Suboccipital Craniectomy for Space-Occupying Cerebellar Infarction. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019, 176, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofi, K.; Shirbache, K.; Shirbacheh, A.; Peyravi, M. Neurosurgical treatment of cerebellar infarct: Open craniectomy versus endoscopic surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2024, 15, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.Y.; Krause, M.; Badik, J.; Lee, J.S.; Horn, P.; Kasuya, H.; et al. Functional Outcomes in Conservatively vs Surgically Managed Cerebellar Infarcts. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayling, O.G.S.; Alotaibi, N.M.; Wang, J.Z.; Fatehi, M.; Ibrahim, G.M.; Benavente, O.; Field, T.S.; Gooderham, P.A.; Macdonald, R.L. Suboccipital Decompressive Craniectomy for Cerebellar Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018, 110, 450–459.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Durán, S.; Walter, J.; Behmanesh, B.; Bernstock, J.D.; Czabanka, M.; Dinc, N.; Dubinski, D.; Freiman, T.M.; Konczalla, J.; Melkonian, R.; Mielke, D.; Mueller, S.; Naser, P.; Rohde, V.; Senft, C.; Schaefer, J.H.; Unterberg, A.; Won, S.Y.; Gessler, F. Surgical infarct volume reduction and functional outcomes in patients with ischemic cerebellar stroke: Results from a multicentric retrospective study. J Neurosurg. 2024, 141, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Díaz, R.; Ortiz-Llamas, L.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, L.A.; Flores-Vázquez, J.G.; Calva-González, M.; Sangrador-Deitos, M.V.; et al. Characteristics and Long-Term Outcome of Cerebellar Strokes in a Single Health Care Facility in Mexico. Cureus 2022, 14, e28993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, Y.; Wakabayashi, S.; Aihara, H.; Ebiko, Y.; Kajikawa, H.; Nakahara, I. Evaluation of clinical significance of decompressive suboccipital craniectomy on the prognosis of cerebellar infarction. Fujita Med J. 2019, 5, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulin Lippi Fernandes, E.; Ridwan, S.; Greeve, I.; Schäbitz, W.R.; Grote, A.; Simon, M. Clinical and Computerized Volumetric Analysis of Posterior Fossa Decompression for Space-Occupying Cerebellar Infarction. Front Neurol. 2022, 13, 840212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, B.H.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, S.K.; et al. Superior cerebellar artery occlusion remaining after thrombectomy for acute basilar artery occlusion. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttler, E.; Schweickert, S.; Ringleb, P.A.; Huttner, H.B.; Köhrmann, M.; Aschoff, A. Long-Term Outcome after Surgical Treatment for Space-Occupying Cerebellar Infarction: Experience in 56 Patients. Stroke. 2009, 40, 3060–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsopoulos, P.P.; Tobieson, L.; Enblad, P.; Marklund, N. Surgical treatment of patients with unilateral cerebellar infarcts: Clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Acta Neurochir. 2011, 153, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, P.; Arnold, M.; Hungerbühler, H.J.; Müller, F.; Staedler, C.; Baumgartner, R.W.; Georgiadis, D.; Lyrer, P.; Mattle, H.P.; Sztajzel, R.; Weder, B.; Tettenborn, B.; Nedeltchev, K.; Engelter, S.; Weber, S.A.; Basciani, R.; Fandino, J.; Fluri, F.; Stocker, R.; Keller, E.; Wasner, M.; Hänggi, M.; Gasche, Y.; Paganoni, R.; Regli, L.; Swiss Working Group of Cerebrovascular Diseases with the Swiss Society of Neurosurgery and the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Decompressive craniectomy for space occupying hemispheric and cerebellar ischemic strokes: Swiss recommendations. Int J Stroke. 2009, 4, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferkorn, T.; Eppinger, U.; Linn, J.; Birnbaum, T.; Herzog, J.; Straube, A.; Dichgans, M.; Grau, S. Long-term outcome after suboccipital decompressive craniectomy for malignant cerebellar infarction. Stroke. 2009, 40, 3045–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Duran, S.; Ridwan, S.; Kranawetter, B.; Dubinski, D.; Freiman, T.M.; Rohde, V.; Gessler, F.; Won, S.Y. Surgical indications and techniques in ischemic cerebellar stroke - results from an international survey. Brain Spine. 2025, 5, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Durán, S.; Wolfert, C.; Rohde, V.; Mielke, D. Cerebellar Necrosectomy Instead of Suboccipital Decompression: A Suitable Alternative for Patients with Space-Occupying Cerebellar Infarction. World Neurosurg. 2020, 144, e723–e733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).