Introduction

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) offers distinct advantages over anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (aTSA) in select patient populations. Notably, rTSA provides superior improvements in postoperative forward elevation and abduction, particularly in patients with preoperative limitations due to glenohumeral osteoarthritis and an intact rotator cuff [

1,

2]. Additionally, rTSA is associated with lower complication and revision rates, suggesting greater long-term reliability compared to aTSA [

3,

4]. Patients undergoing rTSA frequently report more favorable outcomes on functional and pain assessment scales, including the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score [

1,

3]. Furthermore, rTSA may facilitate a more rapid recovery in terms of forward elevation and external rotation within the early postoperative period [

2]. Nevertheless, aTSA remains advantageous for patients with higher functional demands and intact rotator cuffs, as it may yield superior external rotation outcomes [

5,

6]. The selection between rTSA and aTSA should be individualized, considering factors such as rotator cuff integrity, preoperative range of motion, and patient-specific functional goals.

Several studies have substantiated the efficacy of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) in younger patient cohorts. Ek et al. demonstrated significant and sustained improvements in shoulder function and pain relief in patients younger than 65 years with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears, with favorable outcomes persisting for up to a decade postoperatively [

7]. Similarly, Sershon et al. reported enhanced shoulder function following RTSA in patients younger than 60 years presenting with complex shoulder pathology, including failed rotator cuff repairs and fracture sequelae [

8]. However, younger patients undergoing RTSA may exhibit higher complication rates relative to their older counterparts. Ernstbrunner et al. documented a considerable complication rate in patients younger than 60 years, despite functional improvements remaining durable beyond 10 years [

9]. Furthermore, Neel et al. reported that patients younger than 60 years demonstrated inferior clinical outcomes and increased revision rates when compared to older patients [

10].

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is associated with several in-hospital complications that can adversely affect patient outcomes. Among the most frequently reported are acromial and scapular fractures, occurring in 2.5% to 5.4% of cases [

7,

8,

9]. Glenoid loosening is observed in approximately 0.7% to 4.3% of patients [

7,

8,

10], while prosthetic instability, including dislocation, has an incidence of 0.7% to 2.7% [

7,

10].

Periprosthetic fractures, occurring intraoperatively or postoperatively, are reported in 0.8% to 3.0% of cases [

11,

12], whereas periprosthetic joint infections have an incidence of 0.7% to 1.6% [

11,

12,

13]. Additionally, scapular notching, a complication unique to RTSA, is noted in 14.4% of patients.[

4] Neurologic injuries, particularly brachial plexus involvement, affect approximately 2.0% of cases,[

2] and hematoma formation, though less common, has also been documented [

11,

15].

Despite observed associations, comprehensive, large-scale investigations delineating the age-stratified distribution of patients undergoing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) and its subsequent impact on postoperative sequelae encompassing length of hospital stay, complication incidence, healthcare expenditure, and discharge disposition remain conspicuously deficient.

To mitigate this salient knowledge deficit, the present study employs a nationally representative cohort derived from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), spanning the period 2016–2021. Through a meticulous comparative analysis of 48,460 patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, specifically within the cohort aged below 65 years, this investigation endeavors to furnish a robust assessment of epidemiological trends, patient demographic characteristics, comorbid profiles, surgical complications, hospital length of stay, and associated healthcare expenditures. The resultant findings are poised to contribute substantively to evidence-based perioperative management protocols, inform refined clinical decision-making algorithms, and ultimately, augment patient care by elucidating differential risk profiles and outcome trajectories across discrete patient subgroups.

Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study utilized data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a large, nationally representative database maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS captures approximately 20% of all inpatient discharges from hospitals affiliated with HCUP across the United States, representing an estimated seven million unweighted hospitalizations annually. By applying discharge weights provided by the NIS, these data can be extrapolated to generate reliable national estimates, thereby offering a robust foundation for epidemiological and healthcare utilization research.

For this analysis, the dataset spanning 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2021 was used, reflecting the most recent data available at the time of study initiation. Each entry in the dataset, referred to as a “case,” represents a discharge-weighted sample equivalent to a cohort of approximately five patients. This weighting approach is intrinsic to the NIS’s complex survey design, ensuring that the results accurately reflect national inpatient trends.

A total of 9,692 cases involving shoulder arthroplasty were identified, corresponding to a weighted population of 48,460 patients. These cases were classified into seven distinct procedural categories based on ICD-10 procedure codes, as detailed in

Table 1. The majority of procedures involved synthetic prosthetic joint replacements, while a smaller subset employed advanced techniques that targeted specific joint surfaces or utilized biologic tissue substitutes.

Approval for this study was obtained from the relevant institutional review board (IRB). Given the anonymized nature of the NIS data, informed consent was waived in accordance with established guidelines for secondary analysis of de-identified administrative data.

2.2. Cohort Definition and Selection Criteria

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried for the period spanning 2016 to 2021 to identify adult patients (aged 18 to 64 years) who underwent shoulder arthroplasty. Patients were stratified into age-based subgroups to facilitate comparative analysis of outcomes across different stages of adulthood. The age cohorts were defined as follows: 35–45 years, 46–55 years, and 56–64 years.

A total of seven distinct procedural categories were identified, primarily involving the implantation of synthetic prosthetic devices. The dataset comprised 9,692 unique cases, representing a nationally weighted population of 48,460 patients. In accordance with the NIS sampling methodology, each case reflected a discharge-weighted cohort equivalent to approximately five patients, ensuring that the data accurately represent national inpatient trends for shoulder replacement procedures.

2.3. Outcome Variables (End Points)

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate trends, clinical indications, and postoperative outcomes associated with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA). The analysis focused on a range of outcome measures, including inpatient mortality, length of hospital stay (LOS), total hospital charges, and the incidence of inpatient postoperative complications.Postoperative complications were categorized into several domains for comprehensive assessment. Vascular complications included venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Infectious complications were defined by the presence of surgical site infections. Cardiovascular events included myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest. Respiratory complications encompassed conditions such as pneumonia and respiratory failure. Finally, renal complications were assessed through the occurrence of acute kidney injury.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2). Missing data were addressed through single multivariate imputation using the mice package, ensuring robustness of the dataset. Categorical variables were compared across age groups (35–45, 46–55, and 56–65 years) using chi-square tests, while continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Temporal trends from 2016 to 2021 were evaluated through chi-square tests to assess shifts in key demographic and clinical parameters over time.

To identify factors independently associated with cardiac complications, a weighted multivariate logistic regression model was employed. Predictor variables included age group, sex, hospital characteristics, insurance status, and race. The results of the regression analysis are reported as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). A two-tailed significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests. Additionally, post-hoc power analysis confirmed that the study had greater than 80% power to detect medium effect sizes within the sample size of 48,460 patients, ensuring the reliability of the study’s findings.

Results:

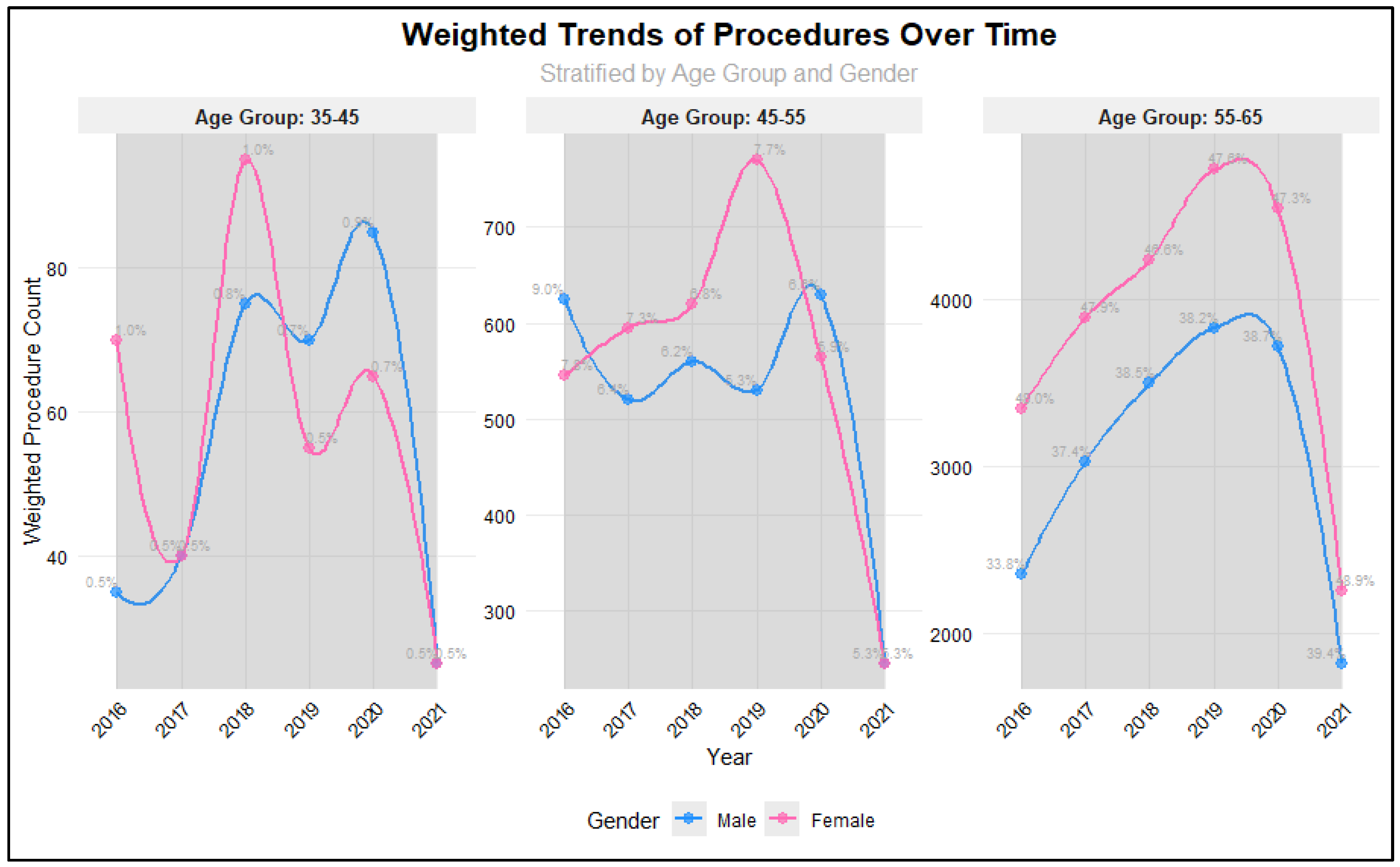

Analysis of procedure volumes from 2016 to 2021 revealed significant variations across age groups and years (p = 0.001). The majority of procedures were consistently performed in the 55-65 age group, with proportions increasing from 81.7% in 2016 to 88.3% in 2021. The 45-55 age group showed a steady decline in representation, decreasing from 16.8% in 2016 to 10.6% in 2021, while the 35-45 age group maintained relatively stable but low proportions (ranging from 0.98% to 1.87%). Procedure volumes showed positive year-over-year growth from 2016 through 2019, with increases of 16.4% (2016-2017), 11.9% (2017-2018), and 10.4% (2018-2019). However, a notable decline began in 2020 (-4.2%), followed by a substantial decrease in 2021 (-51.9%), likely reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gender analysis revealed no significant differences in procedure distribution between males and females across the study period (p = 0.74), suggesting that access to procedures was not influenced by gender. Total procedure volumes peaked in 2019 (n = 2,007) before declining to their lowest point in 2021 (n = 924).

Figure 1.

Weighted Trends in Different Age groups among RTSA patients.

Figure 1.

Weighted Trends in Different Age groups among RTSA patients.

Our analysis comprised 48,460 patients stratified into three age groups: 35-45 years (n=680, 1.4%), 45-55 years (n=6,455, 13.3%), and 55-65 years (n=41,325, 85.3%). Hospital characteristics were similarly distributed across all age groups, with no significant differences in bed size (p=0.63), location/teaching status (p=1.0), or regional distribution (p=1.0). Large, urban teaching hospitals treated the highest proportion of patients across all age groups (44.0-44.1%), while the South region consistently managed the largest share of patients (38.0-38.2%). Patient demographic characteristics showed comparable distributions across age groups (

Table 2). Race distribution was similar (p=0.98), with White patients comprising the majority (65.0-65.4%) across all age groups, followed by Black (14.0%) and Hispanic (11.0%) patients. Private insurance was the predominant primary payer across all age groups (75.0%), with no significant differences in payer mix (p=0.84).

However, significant age-related differences emerged in comorbidity profiles. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes increased markedly with age, from 5.9% in the 35-45 group to 22.8% in the 55-65 group (p<0.001). Similar age-related increases were observed for hypertension (27.9% to 55.3%, p<0.001), dyslipidaemia (10.3% to 40.5%, p<0.001), and sleep apnea (8.1% to 20.4%, p<0.001). Mental disorders showed a unique pattern, peaking in the middle age group (56.5% in 45-55 years) compared to both younger (49.3%) and older (47.5%) groups (p<0.001). Chronic renal disease demonstrated a significant age-gradient, increasing from 1.5% in the youngest group to 6.0% in the oldest group (p<0.001). Notably, certain comorbidities including anemia (p=0.22), Alzheimer’s disease (p=0.93), Parkinson’s disease (p=0.36), and congestive heart failure (p=0.29) showed no significant differences across age groups, though this may be partially attributed to their overall low prevalence in the study population.

Table 3.

Comorbidities in Different Age groups among RTSA patients.

Table 3.

Comorbidities in Different Age groups among RTSA patients.

| |

Age Groups |

|

| Characteristic |

35-45 |

45-55 |

55-65 |

P value |

| Sample size, n |

680 |

6,455 |

41,325 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Comorbidities, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Type 2 Diabetes |

40 (5.9) |

1,300 (20.1) |

9,420 (22.8) |

<0.001 |

| Hypertension |

190 (27.9) |

3,090 (47.9) |

22,840 (55.3) |

<0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia |

70 (10.3) |

1,760 (27.3) |

16,740 (40.5) |

<0.001 |

| Sleep apnea |

55 (8.1) |

1,045 (16.2) |

8,425 (20.4) |

<0.001 |

| Anemia |

10 (1.5) |

295 (4.6) |

1,885 (4.6) |

0.22 |

| Alcohol abuse |

15 (2.2) |

295 (4.6) |

1,130 (2.7) |

0.001 |

| Mental disorders |

335 (49.3) |

3,645 (56.5) |

19,645 (47.5) |

<0.001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease |

0 (0.0) |

5 (0.1) |

25 (0.1) |

0.93 |

| Parkinson’s disease |

5 (0.7) |

20 (0.3) |

260 (0.6) |

0.36 |

| Chronic renal disease |

10 (1.5) |

215 (3.3) |

2,500 (6.0) |

<0.001 |

| COPD |

20 (2.9) |

825 (12.8) |

5,225 (12.6) |

0.003 |

| Congestive heart failure |

10 (1.5) |

195 (3.0) |

1,465 (3.5) |

0.29 |

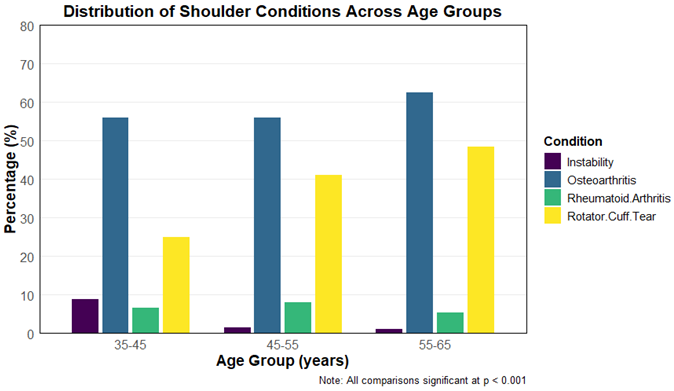

The distribution of clinical characteristics among patients undergoing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty varied significantly across age groups (35–45 years, 46–55 years, and 56–65 years). As presented in

Table 4, rotator cuff tears were increasingly prevalent with age, affecting 25% of patients in the 35–45 age group, 41.2% in the 46–55 group, and 48.5% in the 56–65 group (

p < 0.001). Conversely, rheumatoid arthritis was most prevalent in the 45–55 age group (8.0%) compared to 6.6% and 5.4% in the youngest and oldest groups, respectively (

p = 0.001). Osteoarthritis was the most common indication overall, with rates increasing significantly with age: 56.6%, 56.0%, and 62.5% in the respective age groups (

p < 0.001). Instability was more frequently observed in the youngest cohort (8.8%) compared to 1.4% and 1.1% in the older groups (

p < 0.001). These findings highlight notable variations in the underlying indications for surgery across different age demographics.

Table 5.

Postoperative Hospitalization Metrics and Complication Rates Following Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Stratified by Age Group (35–65 Years).

Table 5.

Postoperative Hospitalization Metrics and Complication Rates Following Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Stratified by Age Group (35–65 Years).

| |

Age Groups |

|

| Characteristic |

35-45 |

45-55 |

55-65 |

P value |

| Sample size, n |

680 |

6,455 |

41,325 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Hospital Stay Metrics |

|

|

|

|

| Length of Stay (days), mean (SD) |

1.89 (1.86) |

1.73 (1.89) |

1.72 (2.02) |

0.55 |

| Total Charges ($), mean (SD) |

92,696 (63,372) |

82,260 (51,836) |

81,576 (49,780) |

0.12 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Complications, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Surgical Site Infection |

5 (0.7) |

0 |

40 (0.1) |

0.02 |

| Urinary Tract Infection |

0 |

60 (0.9) |

430 (1) |

0.45 |

| Cardiac Complications |

15 (2.2) |

245 (3.8) |

2,105 (5.1) |

0.04 |

| Respiratory Complications |

5 (0.7) |

135 (2.1) |

745 (1.8) |

0.48 |

| Acute Renal Failure |

5 (0.7) |

80 (1.2) |

595 (1.4) |

0.67 |

| Embolism (DVT, PE) |

0 |

0 |

95 (0.2) |

0.19 |

| Blood Loss |

60 (8.8) |

580 (9.0) |

3,340 (8.1) |

0.55 |

Analysis of hospital stay metrics revealed comparable patterns across age groups. Mean length of stay was slightly higher in the 35-45 age group (1.89 ± 1.86 days) compared to the 45-55 (1.73 ± 1.89 days) and 55-65 (1.72 ± 2.02 days) groups, though this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.55). Similarly, while mean total charges were highest in the youngest age group ($92,696 ± $63,372) compared to the middle ($82,260 ± $51,836) and older ($81,576 ± $49,780) groups, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12).

Postoperative complications showed varying patterns across age groups. Cardiac complications demonstrated a significant age-related increase (p=0.04), affecting 2.2% of patients aged 35-45, 3.8% of those aged 45-55, and 5.1% of those aged 55-65. Surgical site infections showed an unusual distribution (p=0.02), occurring in 0.7% of the youngest group and 0.1% of the oldest group, with no cases reported in the middle age group. Blood loss complications were relatively consistent across groups, affecting 8.8%, 9.0%, and 8.1% of patients in ascending age order (p=0.55). Other complications showed no significant differences across age groups, including urinary tract infections (p=0.45), respiratory complications (p=0.48), and acute renal failure (p=0.67). Notably, thromboembolic events (DVT, PE) were observed only in the oldest age group (0.2%), though this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.19). Overall, while most complications showed similar rates across age groups, the significant increase in cardiac complications with age and the unique distribution of surgical site infections warrant particular clinical attention in age-specific perioperative management. In a weighted multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with heart complications, age group comparisons showed varying odds ratios (45-55 years: OR=0.726, 95% CI: 0.316-2.100; 55-65 years: OR=1.272, 95% CI: 0.582-3.582), these differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05).

Demographic factors played a significant role. Female patients had 54.8% higher odds of complications compared to males (OR=1.548, 95% CI: 1.315-1.825, p<0.001). Hospital characteristics were significant predictors. Medium and large hospital bed sizes were associated with lower odds of complications compared to small hospitals (Medium: OR=0.756, 95% CI: 0.617-0.925, p=0.007; Large: OR=0.715, 95% CI: 0.599-0.855, p<0.001). Teaching status also showed a protective effect, with urban teaching hospitals having the lowest odds of complications (OR=0.573, 95% CI: 0.453-0.731, p<0.001).

Regarding payment status, patients with private insurance showed higher odds of complications (OR=1.570, 95% CI: 1.227-2.001, p<0.001) compared to other payment types. Race also emerged as a significant factor, with varying odds ratios across different racial groups, notably showing lower odds for Native Americans compared to white people (OR=0.308, 95% CI: 0.110-0.668, p=0.009).

Discussion:

This nationwide analysis of 48,460 patients undergoing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty between 2016 and 2021 revealed distinct temporal, demographic, and clinical patterns. Procedure volumes increased steadily until 2019 before declining sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic, with most surgeries performed in patients aged 55–65 years. Across hospitals, regional distributions and gender representation remained stable, suggesting equitable access to care. Older patients demonstrated significantly higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and sleep apnea, while mental health disorders peaked in the middle-aged group. Surgical indications varied notably by age, with instability predominating among younger patients, rheumatoid arthritis peaking in midlife, and osteoarthritis and rotator cuff tears increasing with age. Despite these differences, hospital stay duration and total charges were comparable across age groups, indicating consistent perioperative efficiency. Complications were generally infrequent, though cardiac events increased significantly with age, and female sex, small hospital size, and private insurance emerged as independent predictors of higher complication risk.

Patients aged 55 to 65 years do not have the highest rates of shoulder replacement surgery; rather, the highest rates are observed in patients older than 65 years. Multiple large cohort studies and national registry analyses demonstrate that while the incidence of shoulder arthroplasty is increasing across all age groups, the most substantial growth and absolute numbers occur in those over 65 years of age [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The reasons for this age distribution are multifactorial. First, the prevalence of degenerative shoulder conditions such as primary osteoarthritis and rotator cuff arthropathy increases with age, making older adults more likely to require surgical intervention [

17,

21,

22]. Second, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA), which is increasingly used for complex cases and rotator cuff pathology, is preferentially performed in older patients due to lower functional demands and higher rates of rotator cuff deficiency [

16,

22]. Third, younger patients (including those aged 55–65) are more likely to have complex or secondary pathologies (e.g., post-traumatic arthritis, osteonecrosis) and are at higher risk for revision surgery and complications, which may temper surgical indications in this group [

23,

24].

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is independently associated with increased length of stay (LOS) and higher hospital charges compared to anatomic shoulder arthroplasty, regardless of age [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Cost analyses consistently show that RSA incurs greater index hospitalization costs than anatomic procedures, with median costs for RSA exceeding those for TSA by

$1,700–

$3,400 [

27,

28].

In our research, length of stay (LOS) and total hospital charges demonstrated no statistically significant differences across the examined age groups, with a mean LOS of approximately 1.7 days and mean total hospitalization costs ranging from

$80,000 to

$90,000. Younger patients (<65 years) undergoing RSA have higher complication and revision rates, and younger age itself is associated with increased total costs and economic burden, especially in those under 50 years [

10,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Specifically, patients under 40 years have the highest charges for both primary and revision procedures, with mean costs for primary surgery exceeding

$41,000, compared to

$39,000 in those aged 40–50 years [

29]. This increased economic burden is driven by higher revision rates, more complex indications (e.g., post-traumatic arthritis, inflammatory arthropathy), and greater resource utilization [

10,

28,

29].

While older age and comorbidities are strong predictors of extended LOS, younger patients undergoing RSA still experience higher costs, and the literature supports that younger age is a nonmodifiable risk factor for increased total charges [

28,

29,

32]. However, the increase in LOS among younger RSA patients may be less pronounced than in older, comorbid populations, and is more strongly linked to the complexity of cases and revision risk.

Multivariate regression analysis identified several noteworthy predictors of postoperative complications following reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Female sex emerged as an independent risk factor, with women demonstrating 55% higher odds of experiencing complications compared with men (p < 0.001). Multiple studies demonstrate that female sex is an independent risk factor for intraoperative and postoperative fractures following reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA), with odds ratios ranging from 2.0 to 2.75 for fracture risk compared to men [

33,

34,

35]. This increased risk is likely multifactorial, including lower bone mineral density and a higher prevalence of osteoporotic changes in women, as well as a greater proportion of women presenting with rotator cuff tear arthropathy and rheumatoid arthritis—both associated with higher complication rates [

33,

35]. Large database analyses and meta-analyses confirm that RTSA is associated with higher overall complication rates than anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty, including infection, instability, and acromial/scapular fractures, and women are disproportionately affected due to their higher representation in the RTSA population and increased susceptibility to fracture [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Conversely, hospital characteristics such as larger bed capacity and urban teaching status were found to be protective, underscoring the advantages of institutional experience, specialized perioperative teams, and access to comprehensive multidisciplinary care. Interestingly, patients with private insurance exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of complications (p < 0.001), an unexpected finding that may reflect differences in case complexity, patient selection, or documentation and coding practices rather than intrinsic risk. Racial differences were modest overall, though Native American patients showed markedly lower odds of complications compared with White patients (p = 0.009). Multiple large database studies demonstrate that Black patients undergo reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) at lower rates than White patients, yet have increased odds of perioperative complications—including acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, sepsis, and surgical site infection—as well as higher mortality and longer hospital stays [

16,

39]. Propensity-matched analyses confirm that while overall 30-day complication rates are similar between Black and White patients, Black patients have significantly higher mortality, longer operative times, and longer hospital stays after shoulder arthroplasty [

39].

This study has several important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis was based on the NIS database, an administrative database that relies on ICD-10 coding, which may be subject to miscoding or underreporting of diagnoses and complications. The database captures only inpatient hospitalizations and does not include postoperative follow-up data, outpatient complications, readmissions, or long-term functional outcomes, limiting the ability to assess implant survival or patient-reported results. Second, the retrospective design precludes establishing causality between demographic factors, comorbidities, and postoperative outcomes. Third, while the dataset is nationally representative, certain variables such as surgical approach, implant type, surgeon experience, and perioperative protocols are not recorded and may confound the observed associations. Fourth, complications were identified only during the index hospitalization, likely underestimating true complication rates. Additionally, socioeconomic and behavioral factors that may influence outcomes, including body mass index, smoking status, and adherence to rehabilitation, were not available. Finally, the analysis period included the COVID-19 pandemic years, which may have introduced external biases due to changes in healthcare access, elective surgery prioritization, and hospital resource allocation. Despite these limitations, the large sample size and weighted national representation enhance the generalizability and robustness of the findings.

The present study possesses several notable strengths that enhance the validity and clinical relevance of its findings. Foremost, it represents one of the largest and most contemporary analyses of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) in the United States, encompassing more than 48,000 patients across a six-year period. The use of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) provided a broad, nationally representative cohort, capturing a diverse range of hospital settings, geographic regions, and patient demographics, thereby improving the generalizability of the results. The study also offers a comprehensive evaluation of temporal, demographic, and comorbidity-related trends, providing valuable insight into evolving patient selection and surgical indications across age groups. Furthermore, the inclusion of detailed analyses of hospital characteristics and payer status adds an important health systems perspective, highlighting institutional and socioeconomic factors associated with perioperative outcomes. The use of weighted multivariate regression models strengthened the robustness of the conclusions by controlling for potential confounders. Collectively, these methodological advantages support the reliability of the observed trends and underscore the study’s contribution to understanding contemporary practice patterns and outcomes in RTSA.

In conclusion, this large, nationally representative analysis provides a comprehensive overview of demographic, clinical, and hospital-related factors influencing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) outcomes among patients aged 35 to 65 years in the United States. Procedure utilization increased steadily until 2019 before sharply declining during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting external healthcare disruptions. Older patients demonstrated a higher burden of metabolic comorbidities, whereas surgical indications varied notably by age, with instability predominating in younger individuals and degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis and rotator cuff pathology driving procedures in older adults.

DVT – Deep Vein Thrombosis

LOS – Length of Stay

HCUP - Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

NIS – National Inpatient Sample