1. Introduction

Implementing biosecurity practices to combat viral and bacterial infections on turkey farms is crucial to the farm's economic viability. Avian reoviruses are important pathogens of turkeys, causing tenosynovitis, arthritis, hepatitis, myocarditis, and encephalitis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The last decade has seen a surge in turkey reovirus (TRV) cases, accompanied by the continuous evolution of the virus, which has resulted in the emergence of pathogenic variants. Currently, seven genotypic clusters of avian reoviruses have been recognized [

5]. The turkey reoviruses belong to one of those clusters as defined by sigma C sequences. Based on M2 gene genotyping, however, three different genotypes of TRV have been recognized [

6]. Currently, there is no commercial vaccine available to combat TRV.

Technologies to minimize viral entry onto farms are always in demand because viruses, after being shed by their infected hosts, can contaminate and survive on inanimate fomites [

7]. Once contaminated, fomites serve as vehicles for the transmission of pathogens to susceptible hosts. The survival of viruses on fomites varies depending on intrinsic factors such as virus strain, initial viral load, and fomite properties, as well as extrinsic factors including relative humidity, sunlight, and temperature. These factors may enable the virus to remain viable long enough to contact new hosts. Both porous and non-porous fomites are found on poultry farms, and viruses generally survive longer on porous surfaces compared to non-porous ones, though some exceptions do exist [

8].

Recently, new devices have become available that are purported to inactivate viruses in the environment. One such device is the UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station (UV-SSS) developed by PathO3Gen Solutions, St. Petersburg, FL. This device generates ozone using ultraviolet (UV) light. Based on wavelength range (100–400 nm), UV comprises four different regions: UVA, UVB, UVC, and vacuum UV. UVA (315–400 nm) has the longest wavelength with the lowest energy, while UVB (280–315 nm) represents the medium wavelength range. UVB is often used for tanning, but has the potential to cause skin burning and even cancer. The UVC (200–280 nm) exhibits germicidal effects, while vacuum UV (100–200 nm) is transmitted only in a vacuum [

9]. The UVC can inactivate fungi, viruses, and bacteria [

10,

11,

12] by damaging the DNA/RNA of microbial pathogens and producing photo-dimers between the pyrimidine nucleotide molecules of the genome [

13]. In addition, UVC lamps at a wavelength of 185 nm can generate ozone in ambient air. The generated ozone, along with UVC, produces synergistic germicidal effects against fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens [

14,

15,

16]. In this study, we compared the inactivation of six strains of turkey reovirus on fomites using the UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station.

2. Materials and Methods

Viruses. Six strains of TRV, namely turkey enteritis reovirus (TERV), highly pathogenic turkey arthritis reovirus-1 (TARV-1), mutated turkey arthritis reovirus-2 (TARV-2), turkey hepatitis reovirus (THRV), a brain isolate of turkey reovirus (TBRV), and a highly pathogenic strain of TARV (TARV-3 or O’Neil strain), were used in this study. These designations (TERV, TARV, THRV, TBRV) are widely used in the field to differentiate turkey-origin reovirus isolates based on clinical presentations or tissue tropism; however, they do not represent formal taxa recognized by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). All isolates are classified within the species Avian orthoreovirus, family Reoviridae, genus Orthoreovirus. All viruses were grown and titrated in Japanese quail fibrosarcoma (QT-35) cells. The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 8% fetal bovine serum, 1 µg/ml fungizone, 50 µg /ml neomycin, 150 IU/ml penicillin, and 150 µg g/ml streptomycin.

Source of UV and ozone. A commercial device called the “PathO3Gen Solutions UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station (UV-SSS)” was obtained from the manufacturer. The device has two ozone-generating lampsFigure and four UV generating lamps, measuring approximately 357 mm and 386 mm in length, respectively. The ozone generating lamps emit at 185 nm, a wavelength that photolyzes molecular oxygen (O

2) to produce ozone (O

3), while the UV-C lamps emit at 254 nm, a germicidal wavelength that directly damages nucleic acids. It is certified to be safe by a Nationally Recognized Test Laboratory. During operation, the UVZone device produces an average irradiance of approximately 2000 µW/cm

2 of UV-C at a wavelength of 254 nm and an ozone concentration of approximately 6.0 ppm. There are two glass shields (left and right) on the device, which are activated automatically for an 8-second disinfection cycle when someone stands on them (

Figure 1). A beeping sound indicates the end of the 8-second cycle.

Fomite Materials and Preparation. Six different fomite types were tested: stainless steel (SS), cardboard (CB), rubber boot (RB), polypropylene (PP), denim fabric (FB), and aluminum (AL). Circular coupons approximately 1 cm2 in area were cut using sterile scissors and placed into three separate 24-well tissue culture plates designated as the Control Plate, the Single-Cycle Plate, and the Double-Cycle Plate. The Control Plate contained fomites that were not exposed to UV or ozone, the Single-Cycle Plate contained fomites exposed to one 8-second disinfection cycle, and the Double-Cycle Plate contained fomites exposed to two consecutive 8-second disinfection cycles (total of 16 seconds exposure). Each fomite type was tested in triplicate for each plate and the entire experiment was independently repeated three times. Each coupon was inoculated with 60 µl of virus suspension and the inoculum was evenly spread across the surface using a micropipette tip. Plates were placed inside a biosafety cabinet at room temperature and left undisturbed to allow the inoculum to air dry.

Figure 1.

Glass shield of PathO3Gen Solutions UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station (SSS).

Figure 1.

Glass shield of PathO3Gen Solutions UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station (SSS).

Procedure. The UVzone device was operated in a room at an ambient temperature of approximately 25ºC and 50% relative humidity. The plates with dried, inoculated fomites were placed upside down directly on the glass shield of the device, with the inoculated surface facing the UV-ozone lamps, ensuring direct exposure of the fomites to both the UV and ozone emissions. Fomites in the Control Plate were handled identically to the exposed samples and placed on the glass surface for 8 seconds without activation of the lamps to account for handling and desiccation effects. Fomites in the Single-Cycle Plate were exposed to activated disinfection cycle by placing the plate on one glass shield while stepping on the other to trigger the device. Fomites in the Double-Cycle Plate were exposed to two consecutive 8-second cycles using the same procedure. Following exposure, fomites were allowed to aerate for 2 minutes at ambient conditions to dissipate residual ozone before elution. This step was a non-chemical way to prevent potential care over effects during virus recovery.

Viruses were eluted from each fomite using 100 µl of elution buffer composed of 3% beef extract in 0.05 M glycine. The eluates were serially diluted 10-fold and were prepared in DMEM containing 2% fetal bovine serum, 50 µg/ml neomycin, 1 µg/ml fungizone, 150 IU/ml penicillin, and 150 µg/ml streptomycin. Each dilution was inoculated in triplicate onto monolayers of QT-35 cells grown in 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated in a 5% CO

2 incubator at 37ºC and examined daily for 5-7 days for the appearance of virus-induced cytopathic effects (CPE). Virus titers were calculated using the Karber method [

17].

UV-Ozone Source Controls. The UVZone device produces UV-C and ozone simultaneously, meaning the two disinfection mechanisms could not be independently isolated. The results represent the combined UV-ozone disinfection effect of the device under normal operating conditions.

Statistical analysis. The effect of exposure time and fomite type on the inactivation of reovirus strains was tested by two-way ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was performed for multiple pairwise comparisons for observed means using the Tukey HSD model. Significance was considered at P<0.05.

3. Results

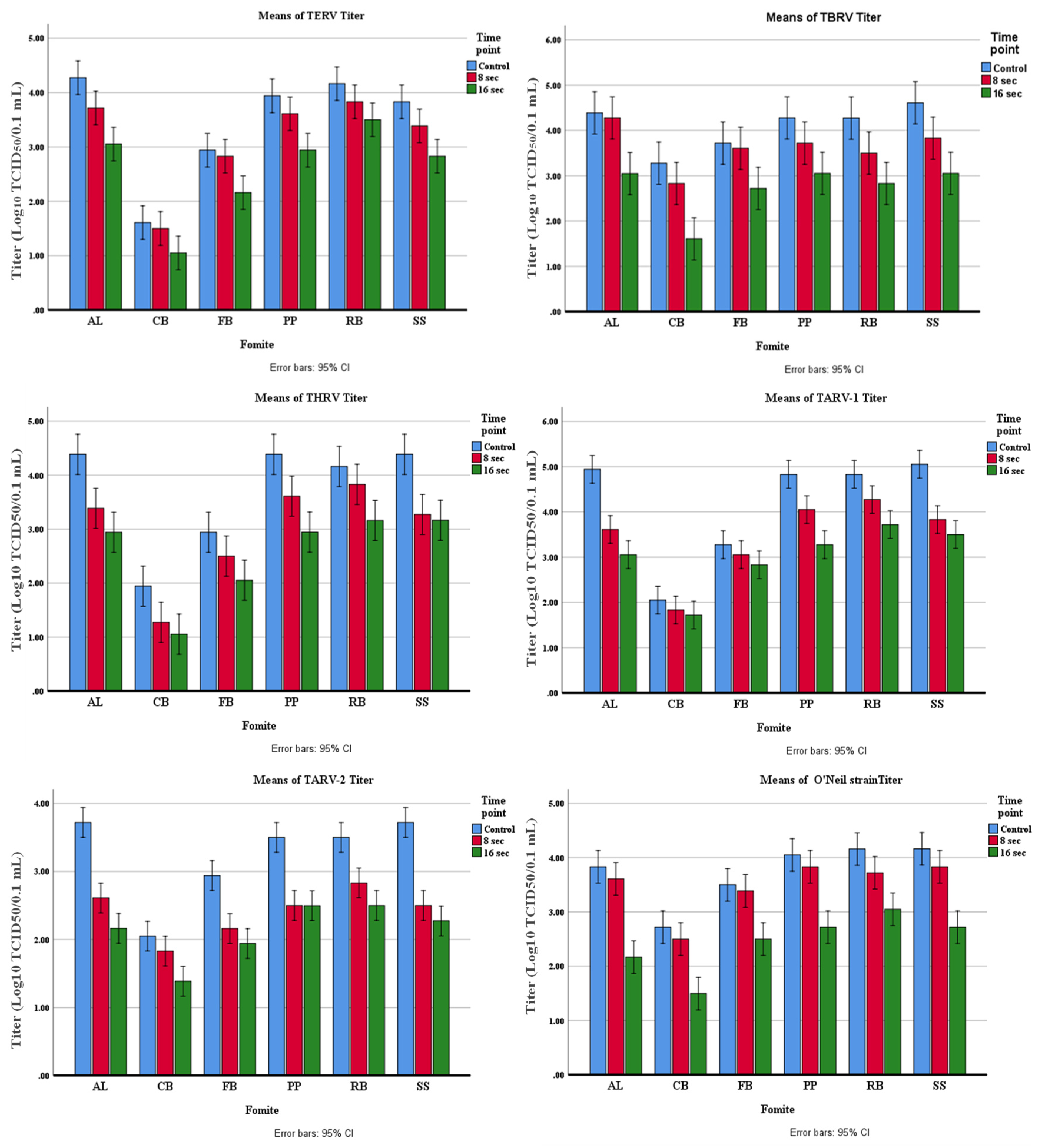

The amount of virus inactivation was higher at 16-sec exposure than at 8-sec exposure for all reovirus strains on all fomites, although some variation was observed. As shown in

Table 1, the highest inactivation of TERV was observed on AL (71.82%) and SS (63.69%) at 8 sec, and on AL (93.98%), SS (90.00 %), and PP (90.00%) at 16 sec. The lowest inactivation of TERV was observed on FB (22.37%) and CB (39.96%) at 8 sec, and CB (70.26%) and RB (78.12%) at 16 sec. At 16-sec exposure, the TERV inactivation was between 70% and 94% on various fomites (

Table 1).

The highest TARV-1 inactivation was observed on AL (95.32%), SS (93.97%), and PP (83.40%) at 8 sec and on AL (98.71%), PP (97.25%), and SS (97.18%) at 16 sec (

Table 2). The lowest inactivation was observed on CB (39.74%) and FB (39.74%) at 8 sec, and CB (53.23%) and FB (63.70%) at 16 sec. At 16-sec exposure, the TARV-1 inactivation was between 53% and 98.7% on various fomites (

Table 2).

Table 1.

Inactivation of TERV on different fomites using the UV-SSS device.

Table 1.

Inactivation of TERV on different fomites using the UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

TERV (Initial titer= 4.5) |

Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

4.270* ± 0.196 |

3.720 ± 0.509 |

71.82 |

3.050± 0.386 |

93.98 |

| CB |

1.610 ± 0.190 |

1.500 ± 0.000 |

39.96 |

1.050 ± 0.190 |

70.26 |

| FB |

2.940± 0.381 |

2.830 ± 0.000 |

22.37 |

2.160 ± 0.000 |

83.40 |

| PP |

3.940± 0.190 |

3.610 ± 0.190 |

53.23 |

2.940 ± 0.190 |

90.00 |

| RB |

4.160± 0.335 |

3.830 ± 0.330 |

53.23 |

3.50 ± 0.000 |

78.12 |

| SS |

3.830± 0.330 |

3.390 ± 0.196 |

63.69 |

2.830 ± 0.330 |

90.00 |

Table 2.

Inactivation of TARV-1 on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Table 2.

Inactivation of TARV-1 on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

TARV-1 (Initial titer= 5.5) |

Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

4.940* ± 0.190 |

3.61 ±0.190 |

95.32 |

3.05 ±0.508 |

98.71 |

| CB |

2.05 ±0.190 |

1.83 ±0.000 |

39.74 |

1.72 ±0.190 |

53.23 |

| FB |

3.27 ±0.509 |

3.05 ±0.508 |

39.74 |

2.83 ±0.000 |

63.70 |

| PP |

4.83± 0.000 |

4.05 ±0.190 |

83.40 |

3.27 ±0.196 |

97.25 |

| RB |

4.83 ±0.000 |

4.27± 0.196 |

72.46 |

3.72 ±0.190 |

92.23 |

| SS |

5.05 ±0.386 |

3.83± 0.000 |

93.97 |

3.50 ± 0.000 |

97.18 |

The highest TARV-2 inactivation was observed on SS (93.97%), AL (92.24%), and PP (90.00%) at 8 sec and on AL (97.24%) and SS (96.45%) at 16 sec (

Table 3). The lowest inactivation was observed in CB (39.74%), RB (78.62%), and FB (83.40%) at 8 sec, and CB (78.12%) at 16 sec. One log reduction in virus titer was observed on FB, PP, and RB after 16 seconds of exposure.

The highest THRV inactivation was observed on SS (92.41%), AL (90.00%), and PP (83.40%) at 8 sec, and on AL (96.45%), PP (96.45%), and SS (94.11%) at 16 sec (

Table 4). The lowest inactivation was observed on RB (53.22%), FB (63.69%), and CB (78.62%) at 8 sec, and CB (87.11%) and FB (87.11%) at 16 sec.

Table 3.

Inactivation of TARV-2 on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Table 3.

Inactivation of TARV-2 on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

TARV-2 (Initial titer= 4.16) |

| Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

3.72*±0.381 |

2.61± 0.190 |

92.24 |

2.16 ±0.335 |

97.24 |

| CB |

2.05±0.190 |

1.83 ±0.000 |

39.74 |

1.39 ±0.196 |

78.12 |

| FB |

2.94±0.190 |

2.16 ±0.000 |

83.40 |

1.94 ±0.190 |

90.00 |

| PP |

3.50±0.000 |

2.50 ±0.000 |

90.00 |

2.50 ±0.335 |

90.00 |

| RB |

3.50±0.000 |

2.83 ±0.000 |

78.62 |

2.50 ±0.000 |

90.00 |

| SS |

3.72±0.190 |

2.50 ±0.000 |

93.97 |

2.27 ±0.196 |

96.45 |

The highest TBRV inactivation was observed on SS (83.40%) and RB (83.02%) at 8 sec, and SS (97.25 %), CB (97.86%), and RB (96.36%) at 16 sec (

Table 5). The lowest inactivation was observed on AL (22.38%) and FB (22.38%) at 8 sec, and FB (90.00%) at 16 sec.

The highest inactivation of the O’Neil strain was observed on RB (63.69%) and SS (53.23%) at 8 sec, and AL (98.52%), SS (96.36%), and PP (95.32%) at 16 sec (

Table 6). The lowest inactivation was observed on FB (22.37%), AL (39.74%), CB (39.74%), and PP (39.74%) at 8 sec, and in RB (92.23%) and FB (90.00%) at 16 sec.

Table 4.

Inactivation of THRV on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Table 4.

Inactivation of THRV on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

THRV (Initial titer= 4.83) |

Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

4.39*± 0.196 |

3.390± 0.196 |

90.00 |

2.940± 0.190 |

96.45 |

| CB |

1.94 ± 0.767 |

1.270± 0.196 |

78.62 |

1.050± 0.386 |

87.11 |

| FB |

2.94± 0.190 |

2.500± 0.000 |

63.69 |

2.050± 0.508 |

87.11 |

| PP |

4.39± 0.196 |

3.610± 0.190 |

83.40 |

2.940± 0.509 |

96.45 |

| RB |

4.16± 0.00 |

3.830± 0.330 |

53.22 |

3.160± 0.000 |

90.00 |

| SS |

4.39 ± 0.196 |

3.270± 0.196 |

92.41 |

3.160± 0.335 |

94.11 |

Table 5.

Inactivation of TBRV on different fomites using the UV-SSS device.

Table 5.

Inactivation of TBRV on different fomites using the UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

TBRV (Initial titer= 4.83) |

Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

4.39*±0.509 |

4.28±0.692 |

22.38 |

3.05±0.190 |

95.43 |

| CB |

3.28±0.386 |

2.83±0.670 |

64.51 |

1.61±0.692 |

97.86 |

| FB |

3.72±0.190 |

3.61±0.508 |

22.38 |

2.72±0.190 |

90.00 |

| PP |

4.28±0.386 |

3.72±0.190 |

72.46 |

3.05±0.386 |

94.11 |

| RB |

4.27±0.196 |

3.50±0.000 |

83.02 |

2.83±0.330 |

96.36 |

| SS |

4.61±0.190 |

3.83±0.000 |

83.40 |

3.05±0.386 |

97.25 |

Table 6.

Inactivation of O’Neil reovirus on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Table 6.

Inactivation of O’Neil reovirus on different fomites using UV-SSS device.

Fomites |

O’Neil (Initial titer= 4.5) |

Titer of control Mean± SD |

Treatment for 8 sec |

Treatment for 16 sec |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

Titer after inactivation

Mean± SD |

log₁₀ reduction values |

| AL |

3.83*±0.000 |

3.61±0.190 |

39.74 |

2.167±0.577 |

98.52 |

| CB |

2.72±0.190 |

2.50±0.000 |

39.74 |

1.50±0.665 |

93.97 |

| FB |

3.5±0.000 |

3.39±0.196 |

22.37 |

2.50±0.000 |

90.00 |

| PP |

4.05±0.190 |

3.83±0.000 |

39.74 |

2.72±0.190 |

95.32 |

| RB |

4.16±0.000 |

3.72±0.190 |

63.69 |

3.05±0.190 |

92.23 |

| SS |

4.16±0.335 |

3.83±0.000 |

53.23 |

2.72±0.190 |

96.36 |

Statistical analysis demonstrated that for four TRV strains (TERV, TBRV, THRV, and O’Neil), both exposure time and fomite type significantly influenced viral inactivation (P<0.05). However, no significant interaction between exposure time and fomite type was detected for these strains, indicating that the effect of exposure duration was consistent across fomites (

Figure 2). Post hoc comparisons confirmed significant differences between untreated controls and both exposure groups, as well as between the 8- and 16-second treatments. In contrast, both exposure time (F=2.36, P<0.05) and fomite type (F=5.36, P<0.05) significantly affected the inactivation of TARV-1 and TARV-2, and a significant interaction was observed between these two factors (F=10.36, P<0.05). This interaction suggests that the magnitude of viral inactivation at different exposure times varied depending on the type of fomite.

4. Discussion

The reovirus strains used in this study were isolated from different clinical conditions in turkeys and some of them had different molecular features. Because of these differences, we reasoned that they might differ in response to UV exposure. The THRV strains were isolated from cases of hepatitis in turkeys. This virus replicated in tendons, causing tenosynovitis in addition to producing hepatic lesions and a drop in body weight on experimental inoculation in turkey poults [

18]. The brain isolate (TBRV) was associated with non-suppurative encephalitis in poults with ataxia. Isolation of reovirus from the brain of a broiler chicken with a nervous system disorder has previously been reported [

2,

19].

Turkey arthritis reoviruses (TARVs) are the main cause of tenosynovitis in turkeys, leading to lameness, hock joint swelling in one or both legs, severe lesions in the hock joint, excessive fluid in tendon sheaths, periarticular fibrosis, cartilage erosion, and rupture of the digital flexor tendon [

20]. Of the three TARV strains used in this study, TARV-1 is very similar to enteric reovirus (TERV) [

20]. The TARV-2 strain is characterized by an insertion/deletion in the S1 gene. Although this strain was isolated from a case of lameness, it did not cause arthritis in turkeys after experimental inoculation. TARV-O'Neil is a highly pathogenic reference strain causing significant tenosynovitis and lameness in infected birds [

21].

Contaminated fomites can be a source of huge disease outbreaks, especially in intensive breeding systems [

22]. However, transmission via fomites is difficult to evaluate due to the mixing of virus entry routes and individual susceptibility of birds due to varying degrees of immunity [

23]. After air, food, and water systems are excluded as the routes of transmission, fomites are then suspected to be the cause of the outbreaks.

Although the UV-SSS device is designed primarily to disinfect shoes, we studied the disinfecting action of this device on the most common fomites that may be present on poultry farms and hatcheries. The use of devices that depend on UVC and ozone emission may reduce the cost of cleaning and disinfection on the farm. It may help reduce the cost of labor in addition to minimizing acute and chronic health impacts associated with the misuse and overuse of disinfecting and/or cleaning chemicals. The UV-SSS device was found to be effective against most bacteria on the soles of shoes [

24]. Epelle et al.[

25] observed that the virucidal activity of UVC was variable among different fomites and that a combination of UVC and ozone generally yielded a better inactivation effect than their individual actions. This combination is one of the most promising methods for the disinfection of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) [

26].

The virus elimination power of shoe sanitizer for 16 seconds was equivalent to that of the most common chemical disinfectants, e.g., Virocid (1:256), Keno X5 (1:400), Synergize (1:200), One Stroke (1:250), and Tek Trol (1:200) after 1 minute of exposure, especially in non-porous fomites [

20]. Schuit et al. [

27] tested 16 different wavelengths of UVC and found wavelengths of <280 nm to be the most virucidal for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Tomás et al. [

28] found that the 254-nm UV-C lamp was less efficient on porous surfaces than on non-porous surfaces. However, the inactivation of viruses may differ because of variations in the structure of viruses and/or their surrounding media.

The TERV was found to have the highest resistance as compared to the other reovirus strains. This is not surprising because enteric viruses are known to have developed a strategy to adapt to natural stressors [

29]. Alidjinou et al. [

30] also showed a long survival time for enteric viruses on certain fomites. In contrast, TBRV was highly susceptible to UV-SSS, probably because of its lower exposure to natural stressors and hence lower adaptation. In general, reovirus survival was lower on cardboard (CB) and fabric (FB), probably due to the porous nature of these fomites. In a previous study, we used the UV-SSS to determine its effect on three different strains of avian influenza virus (AIV); all were inactivated within one 8-sec cycle of exposure [

16]. In the present study, however, the reoviruses were not inactivated within 8 sec but needed 2 cycles of 8 sec each. The difference in inactivation of AIV and reoviruses may be due to the absence of a viral envelope in the latter virus. It is known that UV-C (254 nm) is more effective against enveloped viruses than non-enveloped ones [

31]. In contrast, Canh et al. [

32] showed that UV-LED (265 nm and 280 nm) did not affect the lipid bilayer of enveloped viruses. They believed that the key factor for virus sensitivity to UV-LED is due to the characteristics of the viral genome, e.g., nucleic acid content and length, and structure of the genome.

The presence of the organic matter in the media used to grow reovirus may alter the effect of the UV-SSS device. Organic matter may protect the virus particles, thereby increasing the chance of virus survival due to the lack of penetration power of UV; a phenomenon known as the canyon wall effect [

33]. However, long exposure to UV under experimental conditions may dissolve the organic matter, leading to virus inactivation [

34].

In conclusion, the device using UV light and ozone was shown to eliminate turkey reoviruses, albeit after an exposure time of 16 sec as opposed to 8 sec required for AIV inactivation. Also, there was variation in viral inactivation based on virus strain and the type of fomite. Increasing the time of exposure or using the device for more than one round is efficient in virus inactivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SMG. and SKM; methodology, NMS; validation, SKM; formal analysis, JSH; writing—original draft preparation, NMS; writing—review and editing, JSH; supervision, SMG; project administration, SMG and SKM; funding acquisition, SKM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health’s National. Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grants 1T32TR004385 and 1UM1TR004405. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This project was funded in part by a grant from the USDA’s National Institute of Food And Agriculture, Critical Agricultural Research and Extension: 2023-68008-40546.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Wiese and Lotus Smasal of the Virology Section of the Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for technical assistance. We also thank Sebastian. Lora for access and use of the PathO3Gen Solutions UVZone Shoe Sanitizing Station.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement

No animal or human subjects were used in this study. All experimental procedures were conducted in compliance with institutional biosafety guidelines at the appropriate biosafety level. Standard practices for handling and disposal of biological materials were strictly followed to ensure personnel safety and environmental protection.

References

- Shivaprasad, H. L.; Franca, M.; Woolcock, P. R.; Nordhausen, R.; et al. Myocarditis Associated with Reovirus in Turkey Poults. Avian Diseases 2009/12, 53 (4). [CrossRef]

- Dandár, E.; Bálint, Á.; Kecskeméti, S.; Szentpáli-Gavallér, K.; Kisfali, P.; Melegh, B.; Farkas, S. L.; Bányai, K.; Dandár, E.; Bálint, Á.; et al. Detection and characterization of a divergent avian reovirus strain from a broiler chicken with central nervous system disease. Archives of Virology 2013 158:12 2013-06-16, 158 (12). [CrossRef]

- Ngunjiri, J. M.; Ghorbani, A.; Jang, H.; Waliullah, S.; Elaish, M.; Abundo, M. C.; KC, M.; Taylor, K. J. M.; Porter, R. E.; Lee, C.-W. Specific-pathogen-free Turkey model for reoviral arthritis. Veterinary Microbiology 2019/08/01, 235. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Selim, M.; Armien, A. G.; Goyal, S. M.; Vannucci, F. A.; Deshmukh, S.; Porter, R. E.; Mor, S. K.; Kumar, R.; Selim, M.; et al. Reoviral Hepatitis in Young Turkey Poults—An Emerging Problem. Pathogens 2025, Vol. 14, Page 865 2025-09-01, 14 (9). [CrossRef]

- Egana-Labrin, S.; Broadbent, A. J. Avian reovirus: a furious and fast evolving pathogen: This article is part of the JMM Profiles collection. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2023/10/06, 72 (10). [CrossRef]

- Mor, S. K.; Marthaler, D.; Verma, H.; Sharafeldin, T. A.; Jindal, N.; Porter, R. E.; Goyal, S. M. Phylogenetic analysis, genomic diversity and classification of M class gene segments of turkey reoviruses. Veterinary Microbiology 2015/03/23, 176 (1-2). [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Smith, R. L.; Pongolini, S.; Bolzoni, L.; Rossi, G.; Smith, R. L.; Pongolini, S.; Bolzoni, L. Modelling farm-to-farm disease transmission through personnel movements: from visits to contacts, and back. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1 2017-05-24, 7 (1). [CrossRef]

- Boone, S. A.; Gerba, C. P. Significance of Fomites in the Spread of Respiratory and Enteric Viral Disease. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007-March-15, 73 (6). [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Mohseni, M.; Taghipour, F. Application of ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (UV-LEDs) for water disinfection: A review. Water Research 2016/05/01, 94. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.-C. Mitigating fungal contamination of cereals: The efficacy of microplasma-based far-UVC lamps against Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium graminearum. Food Research International 2024/08/01, 190. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, L. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation: A prediction model to estimate UV-C-induced infectivity loss in single-strand RNA viruses. Environmental Research 2024/01/15, 241. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Oliveira, I. M.; Correia, L.; Gomes, I. B.; Sousa, C. A.; Braga, D. F. O.; Simões, M. Far-UV-C irradiation promotes synergistic bactericidal action against adhered cells of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Science of The Total Environment 2024/03/20, 917. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Padilla, N. S. UVC photon-induced denaturing of DNA: A possible dissipative route to Archean enzyme-less replication. Heliyon 2019/06/01, 5 (6). [CrossRef]

- Epelle, E. I.; Amaeze, N.; Mackay, W. G.; Yaseen, M. Efficacy of gaseous ozone and UVC radiation against Candida auris biofilms on polystyrene surfaces. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024/10/01, 12 (5). [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Huang, Y.-W.; Wang, Y.; Hao, W.; Huang, Y.-W.; Wang, Y. Bioaerosol size as a potential determinant of airborne E. coli viability under ultraviolet germicidal irradiation and ozone disinfection. Nanotechnology 2024-01-17, 35 (14). [CrossRef]

- Sobhy, N. M.; Muñoz, A. Q.; Youssef, C. R. B.; Goyal, S. M. Inactivation of Three Subtypes of Influenza A Virus by a Commercial Device Using Ultraviolet Light and Ozone. Avian Diseases 2023/12, 67 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kärber, G.; Kärber, G. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 1931 162:4 1931/07, 162 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharafeldin, T. A.; Sobhy, N. M.; Goyal, S. M.; Porter, R. E.; Mor, S. K. Comparative pathogenesis of turkey reoviruses. Avian Pathology 2022-09-03, 51 (5). [CrossRef]

- Zande, S. V. d.; Kuhn, E.-M. Central nervous system signs in chickens caused by a new avian reovirus strain: A pathogenesis study. Veterinary Microbiology 2007/02/25, 120 (1-2). [CrossRef]

- Mor, S. K.; Sharafeldin, T. A.; Porter, R. E.; Ziegler, A.; Patnayak, D. P.; Goyal, S. M.; Mor, S. K.; Sharafeldin, T. A.; Porter, R. E.; Ziegler, A.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Turkey Arthritis Reovirus. Avian Diseases 2012/11, 57 (1). [CrossRef]

- Sharafeldin, T. A.; Mor, S. K.; Bekele, A. Z.; Verma, H.; Goyal, S. M.; Porter, R. E. The role of avian reoviruses in turkey tenosynovitis/arthritis. Avian Pathology 2014-7-4, 43 (4). [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. L.; Kramer, A.; Gaither, M.; Gerba, C. P. Role of fomite contamination during an outbreak of norovirus on houseboats. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2007-4-1, 17 (2). [CrossRef]

- CCozad, A.; Jones, R. D. Disinfection and the prevention of infectious disease. American Journal of Infection Control 2003/06/01, 31 (4). [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Poblete, K.; Amadio, J.; Hasan, I.; Begum, K.; Alam, M. J.; Garey, K. W. Evaluation of a shoe sole UVC device to reduce pathogen colonization on floors, surfaces and patients. Journal of Hospital Infection 2018/01/01, 98 (1). [CrossRef]

- Epelle, E. I.; Macfarlane, A.; Cusack, M.; Burns, A.; Mackay, W. G.; Rateb, M. E.; Yaseen, M. Application of Ultraviolet-C Radiation and Gaseous Ozone for Microbial Inactivation on Different Materials. ACS Omega November 15, 2022, 7 (47). [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Romero, J. C.; Pardo-Ferreira, M. d. C.; Torrecilla-García, J. A.; Calero-Castro, S. Disposable masks: Disinfection and sterilization for reuse, and non-certified manufacturing, in the face of shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Safety Science 2020 May 13, 129. [CrossRef]

- Schuit, M. A.; Larason, T. C.; Krause, M. L.; Green, B. M.; Holland, B. P.; Wood, S. P.; Grantham, S.; Zong, Y.; Zarobila, C. J.; Freeburger, D. L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 inactivation by ultraviolet radiation and visible light is dependent on wavelength and sample matrix. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2022/08/01, 233. [CrossRef]

- Tomás, A. L.; Reichel, A.; Silva, P. M.; Silva, P. G.; Pinto, J.; Calado, I.; Campos, J.; Silva, I.; Machado, V.; Laranjeira, R.; et al. UV-C irradiation-based inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in contaminated porous and non-porous surfaces. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2022/09/01, 234. [CrossRef]

- Meister, S.; Klinger, M.; Kohn, T. Isolation and Characterization of Disinfection-Resistant Enteroviruses; Presented at the 74th Annual Swiss Society for Microbiology Meeting, 2016.

- Alidjinou, E. K.; Sane, F.; Firquet, S.; Lobert, P.-E.; Hober, D. Resistance of Enteric Viruses on Fomites. Intervirology 2017 Jun 15, 61 (5). [CrossRef]

- Blázquez E.; Rodríguez C.; Ródenas J.; Navarro N.; Riquelme C.; Rosell R.; Campbell J.; Crenshaw J.; Segalés J.; Pujols J.; Polo J. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the SurePure Turbulator ultraviolet-C irradiation equipment on inactivation of different enveloped and non-enveloped viruses inoculated in commercially collected liquid animal plasma - PubMed. PloS one 02/21/2019, 14 (2). [CrossRef]

- Canh, V. D.; Canh, V. D.; Yasui, M.; Yasui, M.; Torii, S.; Torii, S.; Oguma, K.; Oguma, K.; Katayama, H.; Katayama, H. Susceptibility of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses to ultraviolet light-emitting diode (UV-LED) irradiation and implications for virus inactivation mechanisms. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2023/08/24, 9 (9). [CrossRef]

- Kreitenberg, A.; Martinello, R. A. Perspectives and Recommendations Regarding Standards for Ultraviolet-C Whole-Room Disinfection in Healthcare. Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology 2021 Aug 20, 126. [CrossRef]

- Suyamud, B.; Lohwacharin, J.; Ngamratanapaiboon, S. Effect of dissolved organic matter on bacterial regrowth and response after ultraviolet disinfection. Science of The Total Environment 2024/05/20, 926. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).