1. Introduction

Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary (HPB) surgery stands as one of the most demanding domains in surgical oncology [

1,

2]. It is characterized by its technical complexity, high perioperative morbidity and mortality risk, and complicated vasculo-biliary anatomy with significant inter-patient variability. Even small tumors can abut critical structures like the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), portal vein, or hepatic artery, challenging the feasibility of achieving a radical oncologic (R0) resection. This surgical challenge is compounded by the necessity to preserve an adequate future liver remnant (FLR) or a viable pancreatic remnant to prevent endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, a critical factor for postoperative outcomes and a core dilemma in operative planning.

For decades, conventional imaging, primarily multiphasic Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), has been the backbone of preoperative planning. These methods are highly effective for diagnosis and staging, yet they display inherent limitations, as they present three-dimensional anatomy as a series of two-dimensional slices [

3,

4]. This forces the surgeon to perform a mental reconstruction, a cognitive process that is inherently subjective and can lead to misinterpretations of tumor boundaries, vascular encasement, and anatomical variations, even for experienced clinicians. This potential gap between preoperative perception and operative reality can lead to unexpected intraoperative findings and alterations to the surgical plan, making essential the adoption of more advanced visualization tools.

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction offers a significant step forward. By processing thin-slice imaging data, this technology generates patient-specific volumetric models that reproduce anatomy with high fidelity [

5]. Surgeons can interactively manipulate these models, rotating, zooming, and making structures transparent, to gain a unique understanding of the spatial relationships between tumors, vessels, and bile ducts. The applications are highly practical: 3D models clarify vascular involvement in pancreatic tumors infiltrating the SMV/SMA, enable precise calculation of the FLR, and improve donor safety in living donor liver transplantation by depicting small anatomical branches. Crucially, this enhanced understanding is not merely academic; it has a direct clinical impact. It is reported that insights from 3D models can alter the planned surgical strategy in up to a third of complex cases, fostering more precise resections and reducing intraoperative surprises [

6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) further augments these capabilities by addressing key workflow bottlenecks and adding a predictive dimension to surgical planning [

7]. Its most immediate application is the automated segmentation of imaging data [

8,

9]. Using deep learning algorithms, this once-laborious manual process can be completed rapidly and consistently, making 3D modeling a clinical reality [

10]. Beyond image processing, AI is moving into the predictive domain, with algorithms trained to estimate the risk of specific postoperative complications, like post-hepatectomy liver failure or clinically relevant pancreatic fistula. This allows for proactive risk stratification and personalized perioperative management. The synergy between 3D visualization and AI, thus, creates a continuous digital thread that extends into the domains of surgical training and real-time surgical execution. Virtual reality (VR) platforms immerse surgeons in patient-specific simulations to rehearse complex procedures and shorten the learning curve, while intraoperative augmented reality (AR) overlays provide a real-time “roadmap” by projecting the 3D model onto the live surgical field [

1].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current evidence, evaluating how the integration of 3D reconstruction and artificial intelligence is reshaping the management of complex HPB pathologies. This study will examine their contributions to preoperative planning, intraoperative navigation, and patient outcomes, while also discussing their potential role in complication prediction and surgical training. The rationale for this review lies in the increasing complexity of cases, the well-recognized limitations of conventional imaging, and the mounting evidence that digital innovations are driving a paradigm shift toward a more precise and personalized standard of care in HPB surgery.

2. Methods

This study is a narrative review of the literature. A comprehensive search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published up to October 1st, 2025. The search terms included “3D reconstruction”, “artificial intelligence”, “virtual reality”, and “hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery.” Priority was given to English-language clinical studies, systematic reviews, and relevant technical papers. Reference lists of included studies were also screened to identify additional sources. Case reports were included only when they provided unique or illustrative insights into the practical application of 3D or AI technologies.

3. Preoperative Planning

3.1. Technical Requirements

Preoperative imaging is the foundation upon which three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions are built. For reliable results, imaging must provide very thin slices, ideally ≤1 mm, to allow accurate segmentation of vascular, biliary, and parenchymal structures [

2,

3]. Multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) remains the golden standard, as it captures arterial, venous, and delayed phases essential for mapping tumor–vessel relationships. Modern protocols emphasize arterial phase scanning to assess involvement of the celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and hepatic arterial system, and portal venous phase acquisition to evaluate the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), portal vein, and splenic vein. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly when combined with MRCP sequences, can be fused with CT to enhance the delineation of the biliary tree and pancreatic ductal system, offering complementary information that CT alone cannot provide [

1].

Once the imaging is obtained, data are imported into specialized software for reconstruction. These platforms, which range from research-based tools to commercially available systems, allow segmentation of the pancreas, peripancreatic vasculature, biliary tract, duodenum, and surrounding organs. Some workflows incorporate semi-automatic algorithms, while others still rely heavily on manual tracing by radiologists or engineers. The result is a patient-specific 3D model that can be manipulated, rotated, and dissected virtually. In many centers, these reconstructions can also be exported into 3D-printed models or projected in augmented reality (AR) environments for intraoperative use [

3,

6]. This combination of CT, MRI, segmentation software, and—increasingly—printing or AR visualization forms the technical backbone of modern 3D surgical planning

3.2. Advantages of 3D over Conventional Imaging

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) imaging has served HPB surgeons for decades, yet it presents inherent limitations. Surgeons are required to mentally reconstruct a three-dimensional anatomy from stacks of axial slices [

6]. This mental process is subjective and highly dependent on individual experience, and subtle findings, such as the degree of venous encasement or small arterial variants, may be overlooked. 3D reconstruction reduces this subjectivity by providing an objective, interactive map of the operative field [

6].

The evolution from conventional 2D imaging toward 3D reconstruction represents a natural response to the increasing anatomical and technical complexity of HPB surgery. Early efforts in multiplanar CT and MR fusion paved the way for volumetric rendering and semi-automatic segmentation. As computational power advanced, surgeons transitioned from static visualization to interactive 3D models that mirror true patient-specific anatomy. In recent years, artificial intelligence has accelerated this evolution by automating segmentation, improving image fidelity, and linking visual data to predictive analytics. This integration of 3D reconstruction and AI marks the beginning of a new digital era in surgical planning and execution.

The most widely acknowledged advantage is enhanced anatomical clarity, as 3D models display the spatial relationships between tumor and vessels more intuitively than 2D images, highlighting encasement, abutment, or displacement of critical structures such as the SMA, SMV, portal vein, and hepatic artery [

2,

6]. Anatomical variants, which occur with considerable frequency in hepatic arterial and portal venous systems, are more easily identified in 3D space. A second benefit lies in tumor assessment. Volume rendering permits precise measurement of tumor size and infiltration into adjacent organs. Comparative studies have shown that tumor volumes derived from 3D models correlate closely with pathological specimens, whereas conventional CT measurements often underestimate or overestimate the true dimensions [

2].

Furthermore, 3D models significantly improve resection planning. They allow the surgeon to simulate potential resection planes, anticipate the need for vascular reconstruction, and estimate the volume of remnant tissue. The concept of volumetric planning, well established in liver surgery for calculating the future liver remnant (FLR), has begun to influence pancreatic surgery as well, particularly in complex resections where the balance between oncologic clearance and functional preservation is delicate [

11,

12,

13].

Finally, these models carry educational and communicative value. For trainees, they provide an immersive understanding of anatomical complexity that surpasses textbook diagrams [

1,

14]. For patients, printed or virtual reconstructions offer a tangible way to appreciate the planned operation, facilitating informed consent and shared decision-making [

15].

3.3. Impact on Surgical Strategy

The strongest argument for integrating 3D reconstruction into preoperative planning is its demonstrated ability to alter surgical strategy. Several clinical series have reported changes in operative planning in 20–30% of cases once 3D reconstructions were reviewed. These changes typically involve revised judgments about vascular invasion, resectability, and the extent of resection required. For example, in a study of pancreatoduodenectomies, surgical plans were modified in more than one-fifth of patients after 3D evaluation, with the most frequent adjustments relating to anticipated venous resection or reconstruction [

2]. In borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (BR-PDAC), where accurate assessment of venous and arterial involvement determines operability, 3D reconstructions have proven particularly useful [

6,

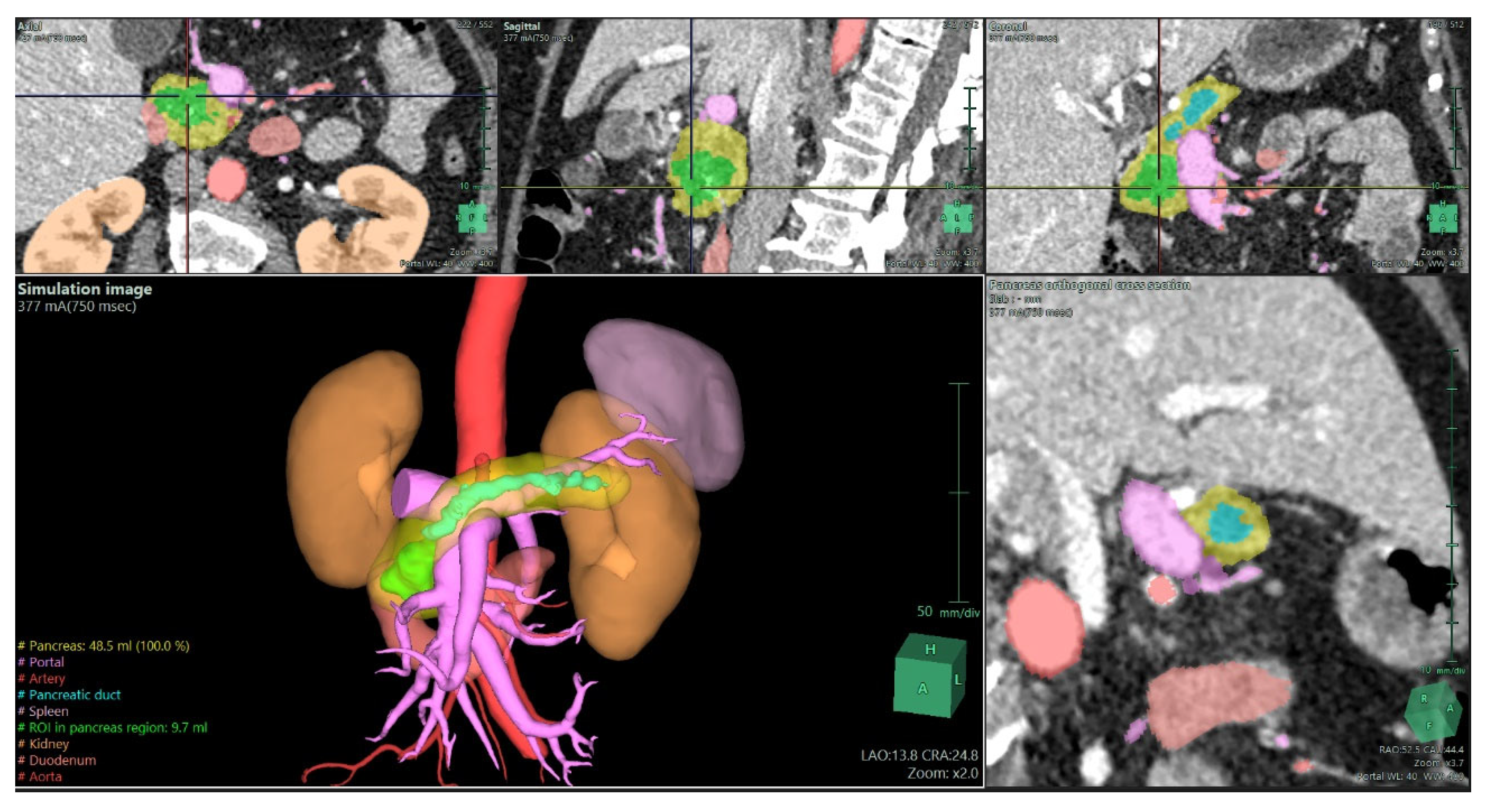

11]. They allow surgeons to visualize tumor abutment of the SMV–portal vein confluence or encasement of arterial branches in a way that 2D slices cannot, as shown in

Figure 1. This not only aids in selecting candidates for upfront surgery versus neoadjuvant therapy, but also prepares the surgical team for complex vascular procedures if required.

The influence of 3D planning is equally evident in liver surgery, where its adoption is more advanced [

4,

16]. 3D-based volumetry leads to shorter operative times, reduced intraoperative blood loss, and decreased transfusion requirements compared with conventional imaging [

4,

16]. Moreover, early evidence suggests that 3D planning contributes to higher rates of R0 resections and fewer intraoperative surprises. Another relevant impact concerns operative efficiency. By clarifying vascular anatomy and resection planes before the incision, 3D planning can shorten the learning curve for young surgeons and provide confidence for senior surgeons facing complex cases [

4]. Beyond individual benefit, these tools may help standardize surgical planning across institutions by reducing reliance on subjective mental reconstruction.

In summary, 3D reconstruction has transformed preoperative planning for complex HPB surgery from a largely interpretative exercise into a reproducible, data-driven process. By ensuring high-quality imaging, accurately segmenting relevant anatomy, and delivering models that improve clarity, precision, and strategy, these technologies directly influence patient outcomes. They allow surgeons not only to plan the procedure with greater certainty but also to anticipate difficulties, avoid unnecessary exploratory laparotomies, and individualize surgical strategies. As 3D software becomes more automated and as AR/VR platforms mature, these reconstructions are poised to become standard practice, not an optional adjunct, in the preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cancer.

4. Intraoperative Applications of 3D Reconstruction in Liver and Pancreatic Surgery

The role of three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction in HPB surgery has steadily expanded over the last decade [

16]. Initially developed as a planning tool to understand complex anatomy before surgery, it is now moving into the operating room itself. Surgeons can rely on interactive 3D visualizations, augmented reality (AR), and even tangible printed organ models while operating. These technologies provide a dynamic way to interpret anatomy and pathology. This is especially relevant in liver and pancreatic operations, where the close relationship between tumors, vessels, and ducts leaves very little margin for error. The goal is not only to improve precision, but also to lower the risks of complications and improve the patient’s recovery afterwards.

4.1. Intraoperative Applications in Pancreatic Surgery

Pancreatic surgery often presents a great challenge with operations, such as pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), involving dissection around the superior mesenteric vein, the portal vein, and the celiac axis, where a small error in vascular dissection can have catastrophic consequences. Miyamoto et al. studied 117 patients undergoing PD and reported that those with 3D simulation had significantly less blood loss compared to conventional planning [

17]. This result is particularly relevant since blood loss and transfusions are well-known risk factors for postoperative morbidity.

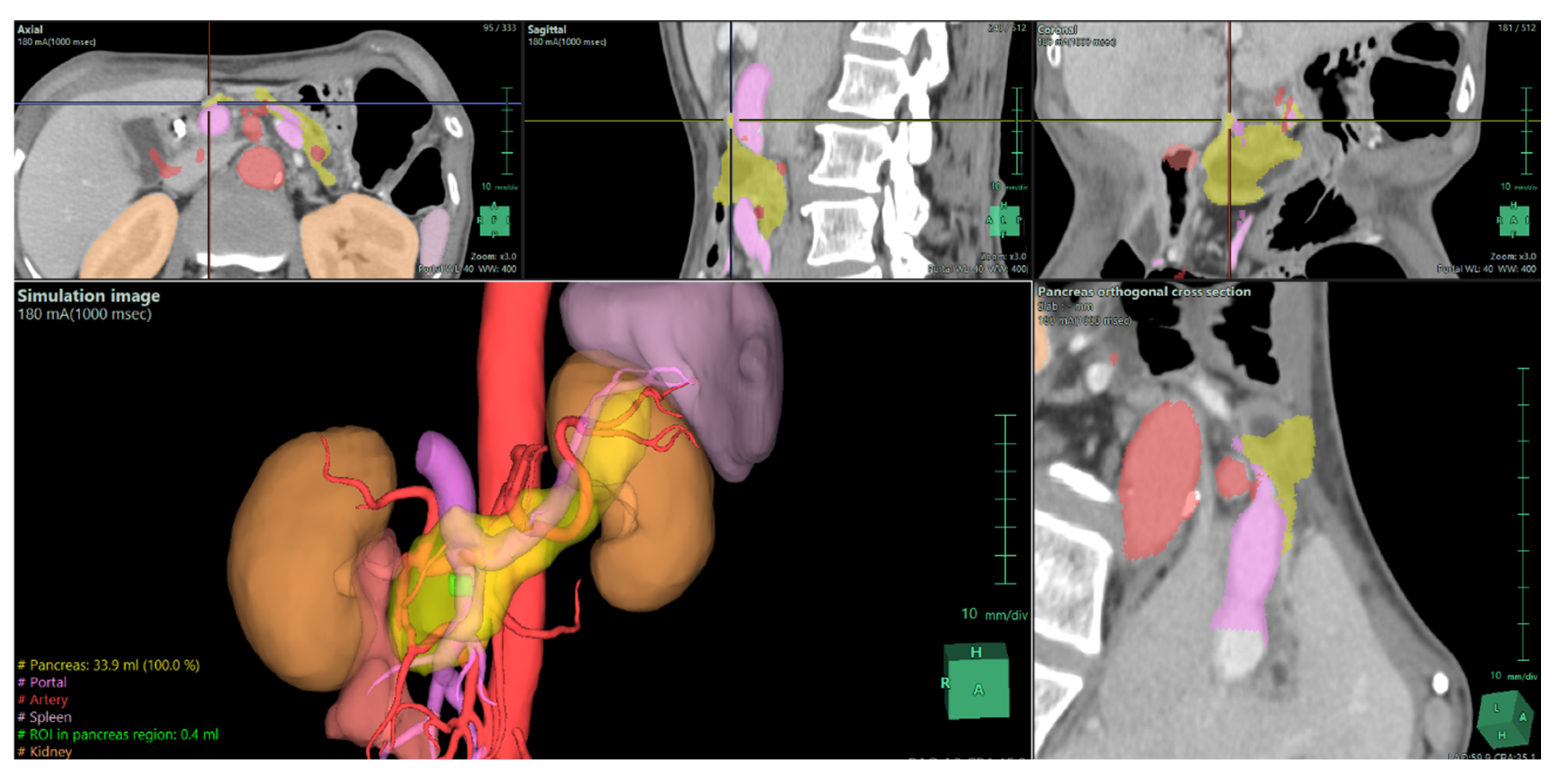

Isolated reports also highlight the ability of 3D reconstructions to reveal details that traditional imaging may miss, as shown in

Figure 2. Templin et al. described a case in which interactive 3D vascular reconstruction revealed a rare Bühler’s anastomosis, not visible on standard CT [

7]. This information, confirmed during surgery, changed the operative strategy and likely prevented serious complications. Vicente et al. went further, showing that 3D vascular models achieved nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity in predicting vascular invasion in pancreatic cancer, outperforming CT and MRI [

3]. This level of accuracy allows for better planning of vascular resections and helps avoid unnecessary or unsafe procedures.

Tang et al. reported AR-assisted PD procedures that required venous resection [

18]. By projecting 3D reconstructions onto the operative field, they improved the surgeon’s orientation and helped to achieve negative resection margins. Together, these studies and reports show that 3D support during pancreatic surgery does more than enhance visualization; it actively contributes to safer dissection, reduces the risk of vascular injury, and lowers the likelihood of complications such as postoperative pancreatic fistula.

4.2. Intraoperative Applications in Liver Surgery

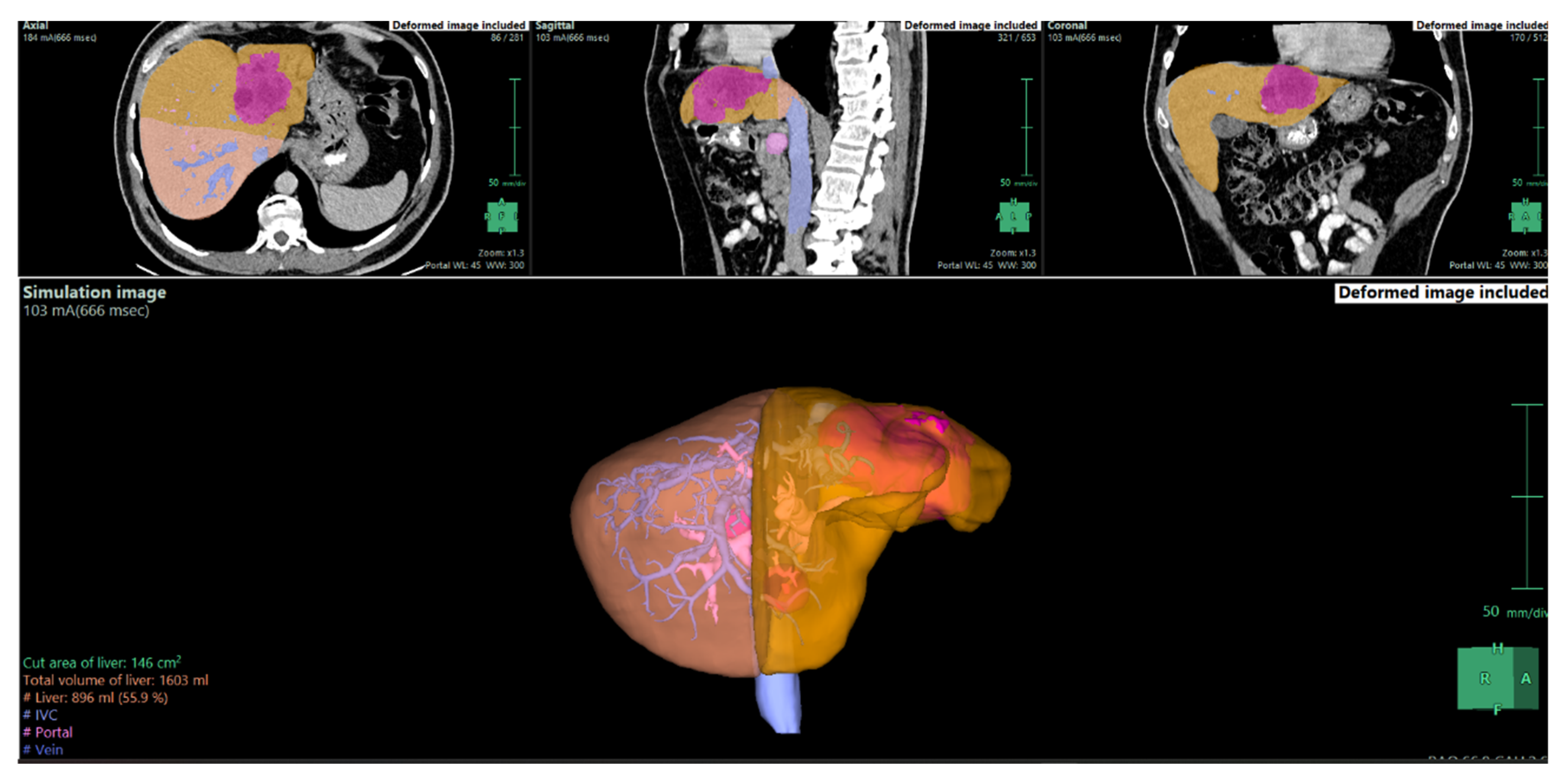

Liver surgery is one of the main areas where 3D reconstruction has demonstrated its potential. During major resections, a precise understanding of the vascular inflow, venous drainage, and bile duct anatomy is essential, as well as an accurate calculation of future liver remnant (FLR) is crucial (

Figure 3). Conventional CT can provide this information but often requires the surgeon to mentally reconstruct 3D relationships from 2D slices. Cotsoglou et al. carried out a multicentric international survey and demonstrated that 3D reconstructions significantly improved the recognition of tumor–vessel relations compared with standard CT [

4]. Surgeons reported that this information reduced intraoperative uncertainty and allowed for more confident intraoperative decisions.

Another breakthrough comes from AR-guided approaches. Wang and colleagues combined 3D reconstruction with intraoperative fluorescence guidance in laparoscopic hepatectomy [

19]. They found shorter operative times, reduced blood loss, and even lower postoperative stress responses, suggesting that intraoperative navigation not only makes the surgery more efficient but also reduces systemic strain on the patient. Rossi et al., in a systematic review, emphasized the role of patient-specific 3D-printed liver models [

20]. These models helped surgeons anticipate variations in vascular and biliary anatomy, reducing the risk of unexpected injury during the procedure.

This evidence is also supported by pooled analyses. For instance, Zeng et al. included more than 1,600 patients in a meta-analysis and confirmed that 3D-assisted hepatectomy is associated with reduced operative time, less bleeding, fewer complications, lower recurrence rates, and improved survival [

21]. These data suggest that the intraoperative use of 3D reconstructions is not just an additional gadget, but a real clinical tool with meaningful impact.

4.3. Posτoperative Outcomes and Clinical Impact

The influence of intraoperative 3D support does not end when the operation is finished. Its benefits extend into the postoperative course. In liver surgery, reduced bleeding and shorter operative times translate into fewer bile leaks, lower risk of postoperative liver failure, and shorter hospital stays [

22]. In pancreatic surgery, accurate recognition of vascular involvement allows for safer resections, which reduces intraoperative injury and decreases the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula [

23]. Importantly, by helping to achieve R0 resections, intraoperative 3D guidance may also lower recurrence rates and support better long-term survival [

24]. The cumulative evidence from surveys, retrospective cohorts, prospective trials, and meta-analyses paints a consistent picture: intraoperative 3D support improves not only technical precision but also clinical outcomes [

14]. Patients benefit from fewer complications, quicker recovery, and in selected cases, better oncological control. These gains are especially valuable in HPB surgery, where morbidity remains high despite advances in perioperative care.

Overall, the intraoperative use of 3D reconstruction represents a major advancement in HPB surgery. By providing real-time orientation and facilitating safer resections, it reduces intraoperative risks and improves recovery. The evidence, drawn from multicentric surveys, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, shows that these technologies are not just experimental, but they are effective clinical tools. Looking ahead, integration with AI-based segmentation, robotics, and immersive AR platforms will likely make intraoperative 3D guidance an everyday part of surgical practice.

5. Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality in HPB Surgery

Artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) are now appearing increasingly in HPB surgery. They rely on the progress of 3D reconstruction but go a step further, as they not only help in showing anatomy before an operation, but also create tools that predict risks, allowing rehearsal before surgery and supporting the surgeon during the operation.

AI predictive models are mainly used for risk estimation. By analyzing imaging data together with clinical variables, machine learning can identify patients who are more likely to develop complications. In pancreatic surgery, one of the biggest issues is postoperative pancreatic fistula. AI models that incorporate duct size, gland texture, and vessel contact seem to outperform older risk scores. Vicente et al. showed that 3D-based modeling was more accurate than CT or MRI in detecting vascular infiltration, which directly influenced the surgical plan [

3]. In liver surgery, algorithms that process 3D reconstructions have been used to predict whether the future liver remnant is sufficient, helping to avoid postoperative liver failure. Meta-analyses such as that of Zeng et al. have confirmed that patients operated with 3D support have fewer complications and better survival [

21].

VR for training and education is another rapidly growing field. Hepatic and pancreatic operations are among the most demanding in surgical oncology, and VR tools provide a safe way to train [

14]. Based on patient-specific 3D models, VR systems allow the surgeon to “walk through” the anatomy before actually entering the operating room. Studies such as Oshiro et al. and Rossi et al. described how VR or 3D-printed models improved spatial understanding, especially of vascular and biliary variations. More importantly, these tools are not only for residents, as even experienced surgeons can use them to test different strategies or rehearse rare scenarios [

20,

25].

Intraoperative VR guidance closes the circle. Real-time overlays of 3D anatomy onto the surgical field are already used in both liver and pancreatic operations. Tang et al. reported the use of VR during pancreatoduodenectomy with vascular resection; the 3D overlay made dissection safer and helped to achieve negative margins [

18]. In liver surgery, Wang et al. combined VR navigation with fluorescence imaging, which resulted in less blood loss and shorter procedures [

13]. A striking example comes from Templin et al., who showed that an unexpected vascular variant, missed on conventional CT, was identified with 3D vascular reconstruction and confirmed during surgery, preventing possible major complications [

7].

These developments are not only about technology but also have a real effect on patients. They result in fewer complications such as bleeding, bile leaks or pancreatic fistula, shorter hospital stay, and in some cases better long-term control of disease. VR-guided resections improve margin status, which may reduce recurrence. AI-based prediction allows better patient selection, avoiding high-risk operations in fragile individuals. At the same time, VR training ensures that younger surgeons are better prepared for complex anatomy. Of course, challenges remain. Production of 3D/VR models can be time-consuming and costly, as Rossi pointed out [

20]. AI models need large, high-quality datasets to be reliable, and this requires collaboration across centers. Yet, the trend is clear: predictive AI, VR training, and VR intraoperative guidance are gradually becoming part of routine HPB surgery.

In conclusion, these three elements form a complementary triad. AI helps to forecast complications, VR training improves preparation, and intraoperative VR supports safe execution. Together, they reduce perioperative risk and hold the promise of better outcomes for patients facing complex liver and pancreatic operations.

6. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the abundance of evidence demonstrating the benefits of 3D reconstruction and AI in complex HPB surgery, the clinical translation of these tools still faces significant practical and scientific hurdles. A primary obstacle is the current workflow’s reliance on resource-intensive model production. Generating a patient-specific 3D model often involves a time-consuming manual or semi-manual segmentation process by specialized technical staff, which limits the rapid turn-around needed in urgent clinical scenarios and adds substantial cost [

10]. Furthermore, current research is often limited by a lack of standardization, with many reports originating from single centers with relatively small patient cohorts and heterogeneous study endpoints. This limits the ability to draw definitive, generalizable conclusions about the superiority and cost-effectiveness of these digital technologies, creating a barrier to widespread adoption into routine surgical practice

To establish these technologies as the standard of care, future investigations must prioritize large multicenter prospective trials that adhere to standardized outcome measures. These measures should include metrics such as operative time, transfusion rates, major complications (Clavien–Dindo grade > 3), and specific complication rates like postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) as defined by established international societies (ISGPS, ISGLS). From a technical standpoint, the predictive AI models require a shift towards larger, high-quality, and diverse datasets achieved through inter-institutional collaboration. This is necessary to enhance the reliability and consistency of risk stratification algorithms, allowing AI to accurately forecast complications by combining imaging-based anatomical metrics with clinical data.

In addition to the technical and logistical barriers, ethical and regulatory considerations must not be overlooked. The implementation of AI-based surgical tools involves sensitive imaging data, raising concerns about patient privacy, data security, and ownership of algorithm-generated insights. Moreover, the absence of standardized validation and regulatory frameworks for surgical AI poses challenges for safe clinical translation. The establishment of ethical guidelines, transparent data governance, and international regulatory harmonization will be essential before full integration into daily surgical workflows. A realistic future vision, therefore, must balance innovation with accountability, ensuring that the digital transformation of HPB surgery remains both effective and ethically sound.

7. Limitations

Although the available literature demonstrates encouraging results, several limitations should be acknowledged. Most of the evidence derives from case reports, small cohort studies, or single-center experiences, often with heterogeneous endpoints and lack of randomization. The absence of standardized metrics for evaluating 3D and AI tools limits comparability across studies. Additionally, the rapid technological turnover may outpace clinical validation, while cost, data storage demands, and dependence on specialized personnel remain substantial barriers. These factors highlight the need for multicenter, prospective trials to confirm the reproducibility and long-term clinical benefits of these digital tools.

8. Conclusions

Three-dimensional reconstruction, artificial intelligence, and immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality are steadily transforming HPB surgery. Across both liver and pancreatic procedures, these tools have consistently demonstrated benefits in terms of anatomic clarity, operative safety, and postoperative outcomes. Evidence indicates shorter operative times, reduced intraoperative blood loss, fewer major complications, and in certain cases, improved oncologic results such as higher R0 resection rates and lower recurrence. Their greatest value lies in shifting surgery from a subjective, experience-driven process into a reproducible and data-driven workflow that can benefit both surgeons and patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P., E.F., M.V.; methodology: A.P., I.K., M.V.; data curation: A.P., I.K., M.S., A.M., D.M., A.S., C.V.; writing—original draft preparation: A.P., I.K., M.S., A.M. D.M., A.S.; writing—review and editing: P.S, S.K., C.V., D.S., E.F., M.V; visualization: A.P., S.M., P.S., S.K., M.V.; supervision: D.S., E.F., M.V.; project administration: M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained for presenting images of individual patients.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Laga Boul-Atarass, I.; Cepeda Franco, C.; Sanmartín Sierra, J.D.; Castell Monsalve, J.; Padillo Ruiz, J. Virtual 3D models, augmented reality systems and virtual laparoscopic simulations in complicated pancreatic surgeries: state of art, future perspectives, and challenges. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2025, 111, 2613–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Ji, J.; Ge, H.; Huang, H. Clinical application of 3D reconstruction in pancreatic surgery: a narrative review. Journal of Pancreatology 2023, 6, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, E.; Quijano, Y.; Ballelli, L.; Duran, H.; Diaz, E.; Fabra, I.; Malave, L.; Ruiz, P.; Garabote, G.; Scarno, F.; et al. Preoperative 3D Imaging Reconstruction Models for Predicting Infiltration of Major Vascular Structures in Patients During Pancreatic Surgery. Surgical innovation 2025, 15533506251376468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotsoglou, C.; Granieri, S.; Bassetto, S.; Bagnardi, V.; Pugliese, R.; Grazi, G.L.; Guglielmi, A.; Ruzzenente, A.; Aldrighetti, L.; Ratti, F.; et al. Dynamic surgical anatomy using 3D reconstruction technology in complex hepato-biliary surgery with vascular involvement. Results from an international multicentric survey. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association 2024, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzenente, A.; Alaimo, L.; Conci, S.; De Bellis, M.; Marchese, A.; Ciangherotti, A.; Campagnaro, T.; Guglielmi, A. Hyper accuracy three-dimensional (HA3D™) technology for planning complex liver resections: a preliminary single center experience. Updates in Surgery 2023, 75, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, S.; J, V.; F, P.; Da, B.; A, L.; E, G.; A, F.; C, T.; L, B.; B, E. 3D modeling to predict vascular involvement in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, R.; Tabriz, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Uslar, V.N.; Lück, T.; Schenk, A.; Malaka, R.; Zachmann, G.; Kluge, A.; Weyhe, D. Case Report: Virtual and Interactive 3D Vascular Reconstruction Before Planned Pancreatic Head Resection and Complex Vascular Anatomy: A Bench-To-Bedside Transfer of New Visualization Techniques in Pancreatic Surgery. Frontiers in surgery 2020, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconi, S.; Pugliese, L.; Del Chiaro, M.; Pozzi Mucelli, R.; Auricchio, F.; Pietrabissa, A. An innovative strategy for the identification and 3D reconstruction of pancreatic cancer from CT images. Updates Surg 2016, 68, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Li, H.; Dong, S.; Gao, Z. Feasibility Study of Intelligent Three-Dimensional Accurate Liver Reconstruction Technology Based on MRI Data. Frontiers in medicine 2022, 9, 834555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szydlo Shein, G.; Bannone, E.; Seidlitz, S.; Hassouna, M.; Baratelli, L.; Pardo, A.; Lecler, S.; Triponez, F.; Chand, M.; Gioux, S.; et al. Surgical optomics: a new science towards surgical precision. npj Gut and Liver 2025, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Albir, M.; Muñoz-Forner, E.; Dorcaratto, D.; Sabater, L. What does preoperative three-dimensional image contribute to complex pancreatic surgery? Cirugia espanola 2021, 99, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzenente, A.; Alaimo, L.; Conci, S.; De Bellis, M.; Marchese, A.; Ciangherotti, A.; Campagnaro, T.; Guglielmi, A. Hyper accuracy three-dimensional (HA3D™) technology for planning complex liver resections: a preliminary single center experience. Updates Surg 2023, 75, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Luo, P. Evaluation of the effectiveness of preoperative 3D reconstruction combined with intraoperative augmented reality fluorescence guidance system in laparoscopic liver surgery: a retrospective cohort study. BMC surgery 2025, 25, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanani, F.; Zoabi, N.; Yaacov, G.; Messer, N.; Carraro, A.; Lubezky, N.; Gravetz, A.; Nesher, E. Clinical outcomes, learning effectiveness, and patient-safety implications of AI-assisted HPB surgery for trainees: A systematic review and multiple meta-analyses. 2025, 5, 387-417.

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhou, B.; Tang, L.; Liang, Y. Integrating mixed reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence in complex liver surgeries: Enhancing precision, safety, and outcomes. iLIVER 2025, 4, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.B.; Bai, L.; Aji, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, J.M.; Zhang, J.H.; Shao, Y.M.; Liu, W.Y.; Wen, H. Application of 3D reconstruction for surgical treatment of hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. World journal of gastroenterology 2015, 21, 10200–10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, R.; Oshiro, Y.; Sano, N.; Inagawa, S.; Ohkohchi, N. Three-dimensional surgical simulation of the bile duct and vascular arrangement in pancreatoduodenectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012) 2018, 36, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Yang, W.; Hou, Y.; Yu, L.; Wu, G.; Tong, X.; Yan, J.; Lu, Q. Augmented reality-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy with superior mesenteric vein resection and reconstruction. Gastroenterology research and practice 2021, 2021, 9621323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Luo, H.; Zhu, W.; Yang, J.; Zeng, N.; Fan, Y.; Wen, S.; Xiang, N.; Jia, F.; Fang, C. Real-time navigation for laparoscopic hepatectomy using image fusion of preoperative 3D surgical plan and intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. Surgical endoscopy 2020, 34, 3449–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, T.; Williams, A.; Sun, Z. Three-Dimensional Printed Liver Models for Surgical Planning and Intraoperative Guidance of Liver Cancer Resection: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, P. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Three-Dimensional Visualized Medical Techniques Hepatectomy for Liver Cancer with and without the Treatment of Sorafenib. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2022, 2022, 4507673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumori, D.; Tschuor, C.; Penninga, L.; Hillingsø, J.; Svendsen, L.B.; Larsen, P.N. Learning curves in robot-assisted minimally invasive liver surgery at a high-volume center in Denmark: Report of the first 100 patients and review of literature. Scandinavian journal of surgery : SJS : official organ for the Finnish Surgical Society and the Scandinavian Surgical Society 2023, 112, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwart, M.J.W.; van den Broek, B.; de Graaf, N.; Suurmeijer, J.A.; Augustinus, S.; Te Riele, W.W.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Hagendoorn, J.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.M.; van Dam, J.L.; et al. The Feasibility, Proficiency, and Mastery Learning Curves in 635 Robotic Pancreatoduodenectomies Following a Multicenter Training Program: "Standing on the Shoulders of Giants". Annals of surgery 2023, 278, e1232–e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavesi, F.; Urban, I.; Bartsch, C.; Simharl, J.; Bogner, K.; Kreuzhuber, K.; Rappold, D.; Trattner, M.; Baumgartner, D.; Dopler, C.; et al. Implementing MIS HPB Surgery Including the First Robotic Hepatobiliary Program in Austria: Initial Experience and Outcomes After 85 Cases. HPB 2023, 25, S554–S555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, Y.; Ohkohchi, N. Three-Dimensional Liver Surgery Simulation: Computer-Assisted Surgical Planning with Three-Dimensional Simulation Software and Three-Dimensional Printing<sup/>. Tissue engineering. Part A 2017, 23, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).