1. Introduction

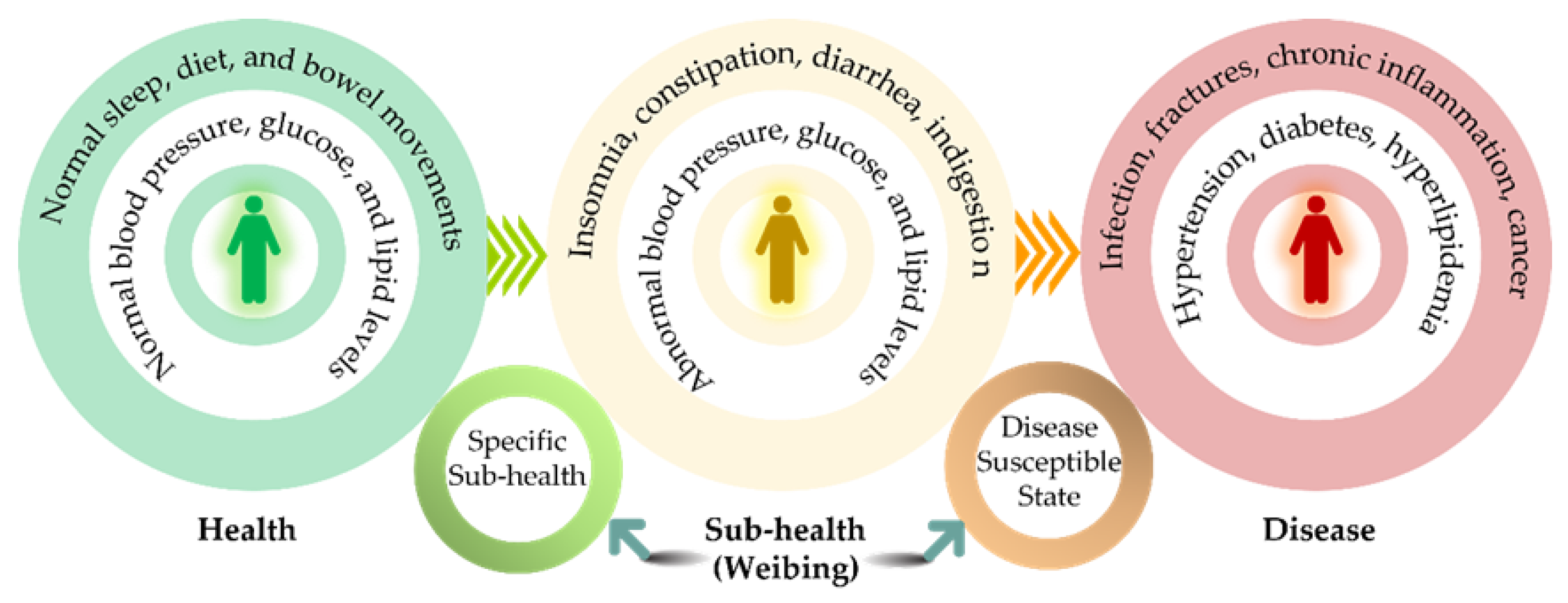

Suboptimal health status (SHS) is a modern medical concept that emerged in China in the late 1980s/early 1990s. This concept, also known as 'suboptimal health', 'sub-health' or 'subhealth', is used to describe a range of subjective physical symptoms such as fatigue, drowsiness, and headaches that persist over time [

1]. Similarly, ”Weibing” (Chinese expression in pinyin), a pivotal ancient concept in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), refers to a health status characterized by a subtle decline in an individual’s innate abilities for self-organization, adaptation, and repair, without significantly compromising physiological or social functions [

2]. The traditional Weibing theory revolves around four core principles: forestalling disease onset, arresting its progression, mitigating exacerbation, and averting recurrence [

3] (

Figure 1).

For example, 'Shanghuo', a concept based on TCM theory, describes a situation of Yin-Yang imbalance when Yang overwhelms Yin. When Yin-Yang becomes imbalanced, it is like a breakdown of homeostasis, which leads to impaired physiological functions and the onset, recurrence, and progression of illnesses [

4].

Medicine and food homology (MFH), as a modern concept and theory, originated and evolved from the description of ΄Consumed on an empty stomach, it is food; consumed by the sick, it is medicine΄ in the distinguished ancient Chinese medical literature-΄Huangdi Neijing Taisu΄ (edited by Shangshan Yang, Suitang Dynasty). So far, the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China has selected and publicized the MFH item, including 110 species of MFH materials (MFHMs) from Traditional Chinese Medicines (TCMs), which have been practiced for thousands of years in China and play a major role in health care. By combining TCM and food virtues, MFHMs can prevent, improve, and treat physical dysfunction and disorders known as subhealth. MFH has become popular among consumers worldwide as a natural medicinal and food product that promotes health and prevents chronic diseases.

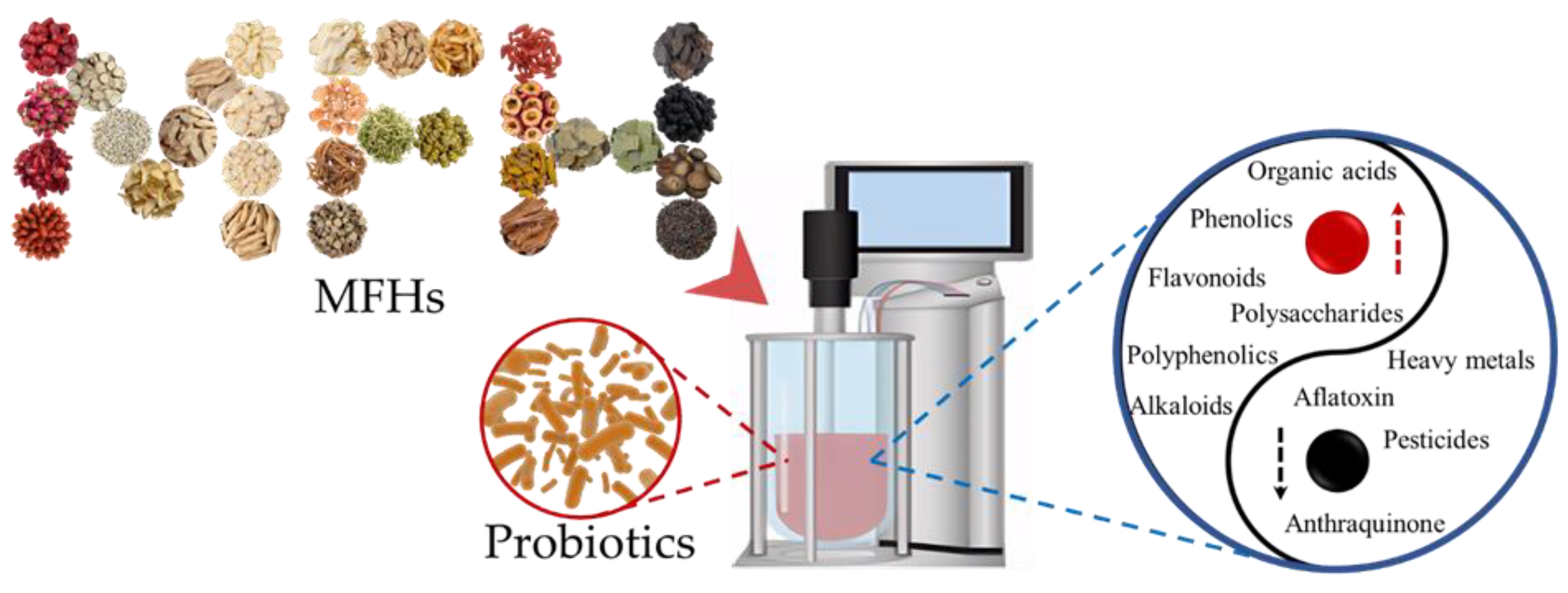

Fermentation is a biochemical process where microorganisms use their vital activities to transform raw materials into desired metabolites. It is a complex, natural, and valuable processing technology. The composition of MFHs is changed by the metabolism of probiotics during probiotic fermentation, which leads to the increase of active ingredients, the decrease of toxic substances, and the change of flavor. Recent studies have demonstrated that probiotic-fermented MFH has more effective activity in the prevention and control of human diseases compared to the unfermented MFH [

5,

6]. Additionally, MFH fermented with probiotics is a fresh source of active ingredients, including secondary metabolites and bio-transformants that help maintain physiologic balance and prevent disease [

7]. Thus, the probiotic fermentation of MFH provides a fresh method for achieving the high medicinal value and commercialization of MFH.

Herein, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the advantages and mutual effects of fermented MFHs and probiotics, as well as the pharmacological activities of MFH fermentation products, the establishment of a scientific probiotic fermentation system of MFHs, and quality control of probiotic-fermented MFHs. Furthermore, the review highlights the challenges of MFH probiotic fermentation and proposes future perspectives using modern technologies such as AI and synthetic biology.

2. The Reciprocal Impact of Fermented MFHs and Probiotics

2.1. Increase of Active Ingredients and Flavors of MFHs

Generally, the content of effective active ingredients in some MFHs is relatively low, which hinders the application of MFHs. Recent studies have confirmed that the probiotic fermentation of MFH can obviously increase the active components. What is the mechanism for increasing the content of active ingredients? The accumulated research evidence found that the increase of active components is mainly due to the destroy of cell walls by a variety of hydrolytic enzymes produced by probiotics to promote the release of bioactive natural ingredients. A study found that Castilla Rose's solid-state fermentation with

Aspergillus niger GH1 resulted in an increase in polyphenolic content through the enzymatic decomposition of the fungus [

8]. Another research demonstrated that the polyphenol content of rose residue was significantly increased from 16.37±1.51 mg/100 mL to 41.02±1.68 mg/100 mL by liquid fermentation with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum B7 and Bacillus subtilis natto [

9]. Solid fermentation with

Monascus purpureus resulted in an increase of approximately 4, 25, and 2 times in the content of lipophilic tocols, λ-oryzanol, and coixenolide from Coix Seed [

10]. Bifidobacterium breve strain CCRC 14061 fermentation resulted in a 785% and 1010% increase in daidzein and genistein contents, resulting in the enhancement of skin health by stimulating the production of hyaluronic acid in NHEK cells [

11].

In general, MFHs have volatile off-flavor substances and an unpleasant smell. Probiotic fermentation has been found to enhance or alter the flavor of MFHs in previous studies. For example,

Pueraria Lobata (PL) is an edible plant known for its significant nutritional properties and contains a range of bioactive compounds, including flavones, isoflavones, and their derivatives. The flavor was enhanced by the fermentation of PL with

Limosilactobacillus fermentum NCU001464, which resulted in an increase in the sweet fruit aroma [

12].

2.2. Generation of New Active Ingredients

The abundance and complex metabolism of probiotics determine the excellent biotransformation capacity that generates new active ingredients from probiotic-fermented MFHs. For example, compound K (C-K), one of the most bioactive ginsenosides, is highly efficiently bio-transformed by hydrolyzing the glycoside moieties of pro-topanaxadiol (PPD)-type glycosylated ginsenosides from American ginseng extract by the fed-batch fermentation of

Aspergillus tubingensis [

13,

14]. The concentration (3.94 g/L) and productivity (27.4 mg/L/h) of C-K after feed optimization in fed-batch fermentation of

A. tubingensis increased 3.1-fold compared to those (1.29 g/L and 8.96 mg/L/h) in batch fermentation, and a molar conversion of 100% was achieved [

13]. In addition, fermentation of

Dioscorea opposite with

Saccharomyces boulardii generates a series of novel low molecular weight polysaccharides, and these polysaccharides, which are easy to digest and have improved antioxidant activity and radioprotection effects [

15].

2.3. Degradation of Toxins

Some MFHs, such as almond, cassia seed, ginkgo biloba, sword bean, and peach kernel, have certain toxicities that may hinder their consumption. For instance, the free anthraquinones from cassia seed are the main active ingredient, which is an effective antioxidant compound, and while the conjugated anthraquinones are regarded as toxins and result in severe diarrhea when it was taken in the body overdose. According to a study,

Kluyveromyces marxianus KM12 fermentation of rhubarb can lead to the conversion of conjugated anthraquinone to free anthraquinone [

16]. The same treatment of probiotic fermentation could be applied to reduce the conjugated anthraquinone in cassia seed. Another study showed that the content of conjugated anthraquinone derivatives was decreased after fermentation with probiotics, while the content of free anthraquinones with antitumor effects increased six-fold [

17]. In addition, the fermentation of Ginkgo biloba with Bacillus subtilis natto could significantly reduce the content of ginkgolic acid to safe levels, which suggests that the decrease of ginkgolic acid may be caused by the enzymic degradation of the probiotic bacteria [

18].

2.4. Reduction of Heavy Metals and Pesticides

Pesticide and heavy metal residues in TCM, including MFH, are a very serious safety issue, which seriously hinders the application of TCM in China. Probiotic-fermented MFH provides an effective method to reduce or eliminate pesticide and heavy metal residues from MFH (

Figure 2). Biosorption of heavy metals by probiotic bacteria is a passive non-metabolic process, which mainly involves chelation, complexation, metal adsorption, ion exchange, and microprecipitation [19-21]. Gram-positive bacteria are the most common type of probiotics, and their cell walls are made up of thick layers of negatively charged peptidoglycans and teichoic acid, which serves as a significant factor in the interaction between probiotics and heavy metals in vitro. Peptoglycans and teichoic acid polymers that are present on

Lactobacillus rhamnosus and

Bifidobacterium longum cells have a remarkable capability to absorb metal cations [22-25]. Some studies demonstrated that the special species of Lactobacillus, such as

Lactobacillus rhamnosus,

Lactobacillus plantarum, and

Lactobacillus brevis, can bind Cd, Pb, and Cu (Ⅱ) heavy metal ions in vitro [

19,

26]. Similarly, lactic acid bacteria [

27] are used as probiotics in MFH fermentation to decompose pesticides [

27]. For instance, the high population of LAB could effectively degrade flubendiamide in soils [

28].

2.5. The Promotion Effect of MFH on Probiotics

The viability and population of probiotics in fermented MFH are influenced by the prebiotics contained in the MFH, including oligosaccharides, polysaccharides, dietary fiber, peptides, and proteins. For example, wolfberry fermented with LAB could remarkably increase the cell density of LAB, which was due to the rich content of nutrients in wolfberry, such as amino acids and polysaccharides [

29]. In addition, the probiotics

L. plantarum BC114 and

S. cerevisiae SC125 showed different responses in the fermentation of mulberry, respectively. The latter probiotic had a higher colony count [

30]. In addition to the benefits of promoting growth, MFH could improve the biosynthesis and accumulation of bioactive metabolites such as organic acids, amino acids, vitamins, and biotin. A study reported that gamma-aminobutyric acid was synthesized in large quantities after fermentation with

Levilactobacillus brevis F064A [

31]. GABA, which is a metabolite of LAB, is an important inhibitory neurotransmitter that participates in many metabolic activities of the human body. It has the effects of sedation, antianxiety, lowering blood ammonia, improving brain function, and promoting alcohol metabolism [

32].

3. Pharmacological Activities of MFH Fermentation Product

Complex biochemical catalysis reactions and metabolism processes are involved in MFH fermentation with probiotics. During fermentation, microorganisms utilize polysaccharides, fibers, proteins, and other medicinal components as nutrients to transform low-activity components into high-activity components, thereby enhancing the efficacy of MFH in the prevention and treatment of sub-health or diseases.

3.1. Anti-Inflammation and Antibacterial Activity

Inflammation is the adaptive protective response of the human body against infection and tissue injury. Anti-inflammation is a process of eliminating infectious factors and repairing tissue. Many evidences indicate that fermentation of MFH with probiotics could enhance its anti-inflammatory effect. A study was carried out to investigate the effect of LAB-fermented turmeric on the content of the bioactive ingredient curcumin and its anti-inflammatory activity in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW 264.7 cells. The results demonstrated that the fermented turmeric with

L. fermentum significantly increased the curcumin content and presented promising DPPH scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities by reducing the nitrite level and suppressing the tumor necrosis factor-alpha and Toll-like receptor-4 [

33]. Another study showed that

Platycodon grandiflorum fermented by

Lactobacillus rhamnosus 217-1 improved a significant increase in polyphenol and flavonoid content, which significantly restored dextran sulfate sodium-induced colonic shortening in the ulcerative colitis (UC) mouse model [

34]. The fermentation of

Curcuma longa by

Lactobacillus fermentum significantly decreased the expression of pro-apoptotic tumor necrosis factor-αand Toll-like receptor-4 in RAW 246.7 cells compared with unfermented

C. longa [

33]. Similarly, another study presented that

Astragalus membranaceus fermented by

L. plantarum enhanced its anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting NO production and downregulating inflammatory factors in RAW 264.7 cells treated with LPS [

35]. The anti-inflammatory benefits of

P. ginseng fermented with

L. plantarum KP-4 were more potent than those of

P. ginseng untreated due to the formation of novel minor ginsenosides such as CK and Rh3, as determined using LC–MS/MS analysis [

36]. Liu et al. used the probiotics

L. plantarum,

L. royale, and Streptococcus spp. to ferment

Lycium barbarum juice, respectively, and further to improve the inflammation of a dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis mouse model [

37]. Morus alba extract fermented by

L. acidophilus A4 was applied to intervene in the intestinal mucositis in a rat model induced by 5-fluorouracil by upregulating MUC2 and MUC5AC gene expression to improve mucin production and reduce IL-1β expression [

38].

A study was conducted to examine the antibacterial properties of fermented

Hippophae rhamnoide juice against 10 foodborne pathogens and discovered that its efficiency increased after being fermented with

L. plantarum RM1. The antimicrobial potential of fermented

H. rhamnoide juice may be enhanced by an increase in phenolic content and acidity during fermentation [

39].

In addition to contributing to the release of antibacterial substances from MFH, probiotics synthesize a variety of metabolites, including acetic acid, lactic acid, bacteriocins, diacetyl, and hydrogen peroxide, all of which are natural antibacterial substances [

40]. For example, nisin, which is produced by Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus, has antibacterial properties against both spore-forming bacteria and Gram-positive bacteria [

41].

3.2. Regulation of Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension, and Hyperglycemia

Panax ginseng fermented with Monascus spp. had an enhanced effect on obesity in female ICR high-fat diet (HFD)-fed rats. The mechanism for regulating hyperlipidemia relies on a significant decrease in adipocyte diameter per ovary, abdominal fat pads, and abdominal fat thickness in a dose-dependent manner [

42]. The Liu group reported that

Gynoacemma pentaphllum fermented with

Lactobacillus spp. Y5 contained a higher content of anthraquinones, polysaccharides, and cyclic allyl glycosides than the unfermented

G. pentaphllum. The application of fermented

G. pentaphllum for 8 weeks in the treatment of diabetic rats resulted in a decrease in blood glucose levels and an increase in body weight of the rats [

43]. Another study by the Li group evaluated the hypoglycemic effect of

Lactobacillus shortus YM 1301-fermented

Polygonatum sibiricum by analyzing glucolipid metabolism in streptozotocin-induced T2DM rats fed a high-fat diet. These findings indicate that fermented

P. sibiricum demonstrated superior effects on insulin resistance and glycated hemoglobin compared to unfermented

P. sibiricum. Fermented

P. sibiricum not only enhances AMPK activation, but also raises the ratio of phosphorylated AKT/AKT to prevent problems with glucose tolerance and insulin resistance [

44]. In addition, the fermented

P. ginseng with Monascus can reverse the decrease in species abundance and diversity of the intestinal flora in rats fed a high-fat diet, which improves the biotransformation of ginsenosides to regulate the lipid metabolism [

45]. Similarly,

P. ginseng fermented with

Lactobacillus fermentum can enhance the growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which can improve the alcoholic liver injury in a murine model [

46].

Laminaria japonica fermented by

Lactobacillus shortcombicus FZU0713 affected primary and secondary bile acid biosynthesis in a rat model of hyperlipidemia by regulating the gut flora.

Solid-state fermentation of

Astragalus membranaceus was conducted using

Paecilomyces cicadidae and used as a treatment for diabetic nephropathy (DN). The results indicated that fermented

A.

membranaceus significantly reduced urinary proteins, serum creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen in mice with DN and resulted in a notable mitigating effect on mice with DN through the autophagy of podocytes, which may delay the onset of DN by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [

47].

3.3. Antioxidation, Immune Enhancement, and Antitumor

Jujube’s active components include polysaccharides, dietary fiber, total flavonoids, and carotene, etc., and it has the power to invigorate Qixue in Chinese medicine, nourish blood, and soothe nerves. A study investigated the potential anti-neurodegenerative properties of yeast-fermented

Ziziphus jujuba using an amyloid β-protein (25–35)-induced rat disease model. The findings indicate that fermented

Z. jujuba has a beneficial effect on cognitive function and memory by reducing oxidative stress. It should be noted that fermented

Z. jujuba had stronger antioxidant effects than unfermented

Z. jujuba [

48].

Different probiotic strains were utilized in the fermentation process of

L. barbarum juice, such as

B. subtilis,

B. licheniformis,

L. reuteri, and a combined strain of

L. rhamnosus and

L. plantarum. The results showed that the fermentation of

L. barbarum juice affected the conversion of free and bound forms of phenolic acids and flavonoids and increased their antioxidant capacity [

49]. In addition,

Dimocarpus longan fermented with the LABs of

L. plantarum and

L. mesenteroides improves the antioxidant activity, depending on the increase of alkaline amino acids and a decrease in the content of free amino acids responsible for the bitter taste [

50]. Furthermore,

H. rhamnoide juice fermented by

L. plantarum increased the phenolic compound content of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2’-azobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), which had strong scavenging activity of free radicals through hydrogen atoms or direct electron transfer [

39].

The antioxidant mechanism of the probiotic-fermented MFH might be related to the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. For instance, the relaxation of oxidative stress in H2O2-induced cell model was achieved by the fermented

C. lacrymajobi with

L. reuteri, which could significantly activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and reduce the level of intracellular ROS by upregulating the COL-I gene and downregulating the MMP-1 expression [

51].

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) are neuronal dysfunction diseases caused by the loss of neurons and their myelin sheaths, which mainly include Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and show clinical symptoms such as motor dysfunction, cognitive decline, and dementia according to the affected brain regions. The fermentation of ginseng with

L. paracasei has been found to enhance spatial memory deficits caused by cerebral ischemia and beta-amyloid injection, as well as protect hippocampal neurons from cell death in rats [

52]. Another study found that the fermented

Zingiber officinale extracts with

A. niger exhibited greater neuroprotective properties than unfermented

Z. officinale extracts, which was attributed to the biotransformation of α, β-unsaturated ketones to 6-paradol by fermentation. Enhancing neuroprotective effects was attributed to the increase in bioavailability of 6-paradol [

53].

Ganoderma lucidum is not only a fungus, but also a type of MFH. Li and coworkers conducted a study to investigate the impact of fermented

G. lucidum with

Lactobacillus acidophilus and

Bifidobacterium bifidum on dexamethasone (DEX)-induced immunosuppression in a rat model. According to the results, the fermentation broth significantly enhanced immunity, restored and corrected intestinal flora dysbiosis in rats treated with DEX [

54]. In addition, the Liu group investigated the effect of LAB-fermented

A. membranaceus and

Raphani Semen on the immune function of immunosuppressed mice. The results demonstrated that the probiotic fermentation could increase the abundance of beneficial bacteria and the production of short-chain fatty acids in the gut of mice, resulting in the restoration of intestinal microecology and the improvement of immunosuppression [

55].

The fermented coix seed with

Monascus purpureus demonstrated remarkable antioxidant and anticancer activity, depending on the increase in the content of lipophilic tocols, γ-oryzanol, and coixenolide. The fermentation product showed a 42% decrease in inhibitory concentrations for 50% cell survival (IC50) in treating human laryngeal carcinoma cells Hep2, compared to the raw product [

10].

3.4. Regulation of Intestinal Microecology

Many studies have demonstrated that fermented MFHs can influence and improve the intestinal microecology and maintain intestinal health. The Shi group reported that the fermented-Astragalus polysaccharides (APS) with

Lactobacillus rhamnosus significantly regulated the microbial composition and diversity in fecal samples from 6 healthy volunteers by anaerobic incubation in vitro [

56]. Another study found that the fermented

H. rhamnoide with probiotics significantly increased the content of total flavonoids, total triterpenes, and short-chain fatty acids, which effectively improved alcohol-induced liver injury by reversing the decline of the gut microbiota Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio caused by alcohol [

57]. In addition, the fermented raspberry juice (FRJ) increased the valeric/isovaleric acids content in vitro and improved the production of acetic, butyric, and isovaleric acids as well as the cell adhesion molecules-related gene expression in vivo, and meanwhile, the low and median doses of FRJ regulated the microbiota to a healthier state compared to the high dose supplementation [

58].

L. barbarum juice fermented with LAB, including

L. paracasei E10,

L. plantarum M, and

L. rhamnosus LGG, enhanced intestinal integrity, reconstructed the gut flora by increasing the beneficial LAB and their metabolites [

59]. Similarly,

A. membranaceus fermented by

L. plantarum alleviated colitis and altered the composition of the gut microbiota, which enhanced the amount of Akkermansia and Alistipes correlated with short-chain fatty acid production [

60].

4. Establishment of the Effective Probiotic Fermentation System

4.1. Selection of MFHs

After thousands of years of inheritance and development, the fermentation of TCM is not only limited to the fermentation of a few Chinese medicine varieties such as Massa Medicata Fermentata (MMF), Monascus, Semen Sojae Preparatum, Pinellia Fermentata, and Arisaema cum bile, but has expanded to more TCM, especially MFHs. Among 110 species of MFH materials (MFHMs), there are about 40 kinds of MFHMs are used for probiotic fermentation, as shown in

Supplementary Table S1, accounting for about one third of the total MFH items. These MFHs suitable for fermentation mainly include fruits, rhizomatous roots, and seeds such as

Crataegus pinnatifida,

Dioscorea opposite,

Panax ginseng,

Polygonatum sibiricum,

Polygonatum odoratum,

Astragalus membranaceus,

Asparagus cochinchinensis,

Lycium barbarum,

Dimocarpus longan,

Rubus chingii,

Morus alba,

Curcuma Longa, and

Cornus officinalis, etc.

4.2. Determination of Probiotics

4.2.1. Experimental and Empirical Method

In the screening and determination of the probiotic microorganisms for MFH fermentation, the initial step involves safety screening, physiological and functional characteristics of the target probiotic. The probiotics should meet the crucial principles, which are the cornerstone for ensuring safety and effectiveness. As for the safety of probiotics, the microorganisms should be included in the species list used for food, which is approved by the governmental administration. So far, a total of 41 species or subspecies of microbes have been approved in China as edible probiotics, including bacterial species and fungal species such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lacticaseibacillus, Limosilactobacillus, Lactiplantibacillus, Ligilactobacillus, Latilactobacillus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus, Propionibacterium, Acidipropionibacterium, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, Weizmannia, Mammaliicoccus, Staphylococcus, Saccharomyces, Kluyveromyces. These probiotics do not produce mycotoxins, bacterial toxins, or other harmful metabolites and are generally recognized as safe [

61].

Secondly, the probiotics should have a special and highly active enzyme system, such as cellulase, pectinase, protease, amylase, and esterase, to decompose the cell wall of MFH and promote the dissolution, transformation, and release of active ingredients. For example, the filamentous fungus Aspergillus spp. can produce a variety of cellulases, proteases, and glucoamylase, and is suitable for rhizome MFH such as Ginseng, American ginseng, and

Codonopsis pilosula, etc [

13,

62,

63]. Furthermore, LAB can decompose botanical polysaccharides to improve the dissolution and are suitable for MFHs containing polysaccharides such as Astragalus,

Polygonatum sibiricum, Chinese Wolfberry, Mulberry, Ginseng,

Eucommia Ulmoides, Longan pulp, Longan, and Jujube, etc [27,35,44,64-66].

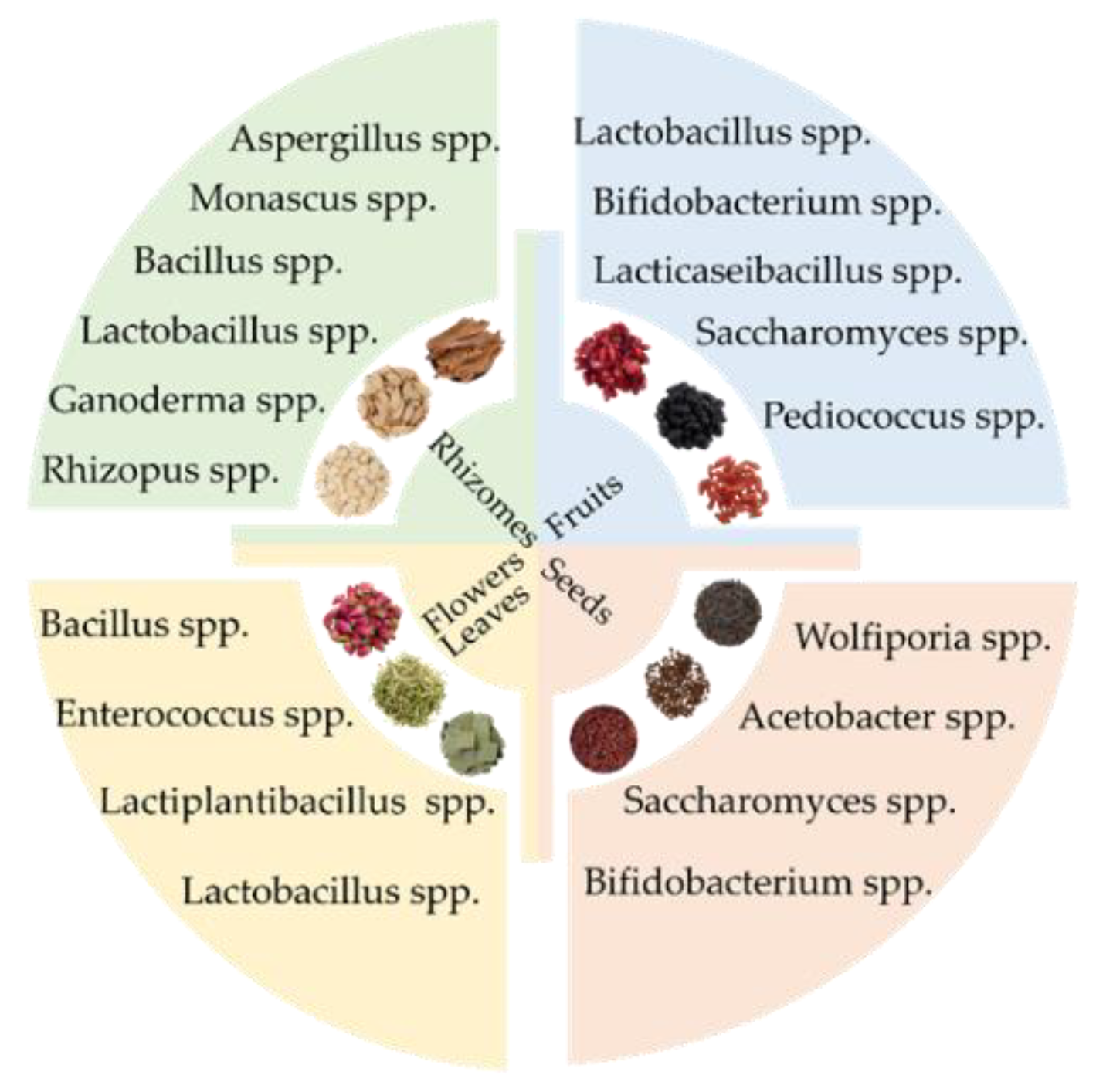

Summarily, rhizome MFHs such as Astragalus root,

Codonopsis pilosula,

Ganoderma lucidum, and American ginseng are generally fermented by Aspergillus spp., Monascus spp., and Bacillus spp., etc. Aromatic MFHs such as Rose, Honeysuckle, Citrus aurantium, and Sophora flower generally select Bacillus spp., Enterococcus spp., Lactiplantibacillus spp., and Lactobacillus spp. as probiotics to convert glycoside components to release volatile substances. Fruit MFHs are fermented by LAB probiotics to regulate intestinal flora and enhance polysaccharide absorption (

Figure 3).

Except for the above characteristics, the probiotics should possess genetic stability and not be easily mutated or degraded during the fermentation process. In addition, the probiotics should be able to adapt to the special environment of MFHs. For example, many medicinal materials such as alkaloids, flavonoids, and volatile oils from MFHs show obvious antibacterial function [

67,

68]. Therefore, the probiotics should be able to tolerate the antibacterial components and grow and reproduce using them as a source of nutrients. Furthermore, the probiotics should demonstrate strong environmental adaptability and be easily able to grow vigorously under the set fermentation parameters, including temperature, pH, oxygen, relative humidity, and redox potential.

4.2.2. AI Assistant Selection of Probiotics

Artificial intelligence (AI) has made significant changes to the evaluation of probiotics in the related fields of research and application. The Zhang group developed a novel and free online platform, iProbiotics, which effectively screens and identifies probiotics from LAB with a high prediction accuracy of 97.77%. This bioinformatics algorithm tool introduced machine learning to analyze the k-mer composition (k-mer is a substring of length K in DNA sequence data) from whole-genome primary sequences, which significantly enhances the efficiency of evaluating a single probiotic strain from the common 3–6 months to just 2 hours per strain without the consumption of extensive time and effort for experimental validation [

69]. Furthermore, an AI-based method for screening interactive starter combinations for dairy fermentation was developed. This method has been validated by humidity experiments and can accurately predict the interaction between two probiotics with a high precision rate of 85%, which can lead to improvements in the quality and production of dairy products [

70]. Therefore, using AI and machine learning, the screening and evaluation of probiotics for MFH fermentation can be achieved efficiently and accurately.

4.3. Fermentation Mode

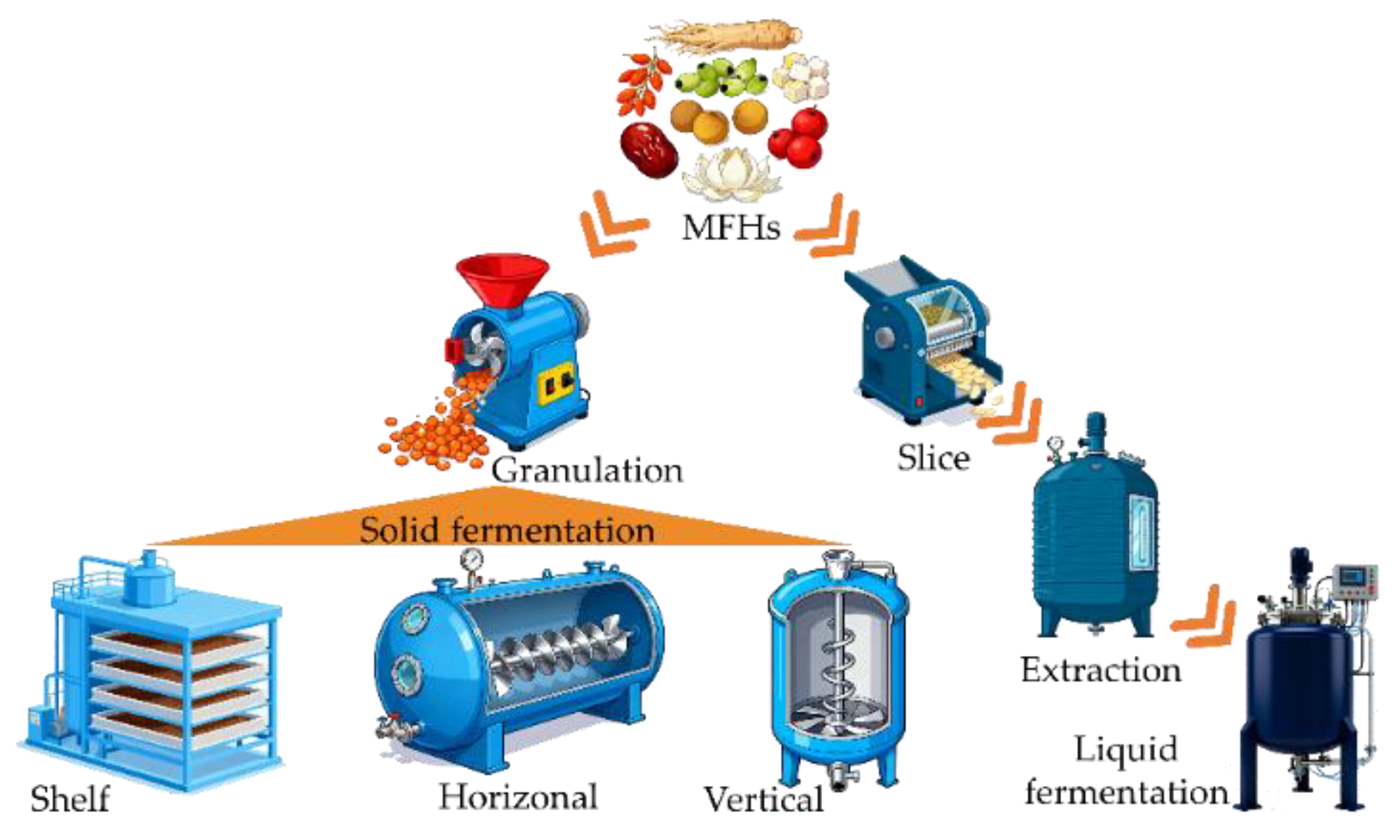

4.3.1. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

At present, SSF and liquid fermentation are the main modes of MFH fermentation. SSF has existed in China for a long time and is characterized by low humidity, low water activity, and a non-continuous physical phase. Aspergillus, Mucor,

Ganoderma lucidum,

Cordyceps militaris, and Rhizopus are better suited for SSF, along with single-cell yeast [8,71-73]. The MFH substrates for solid fermentation were generally crushed into granules before fermentation, as shown in

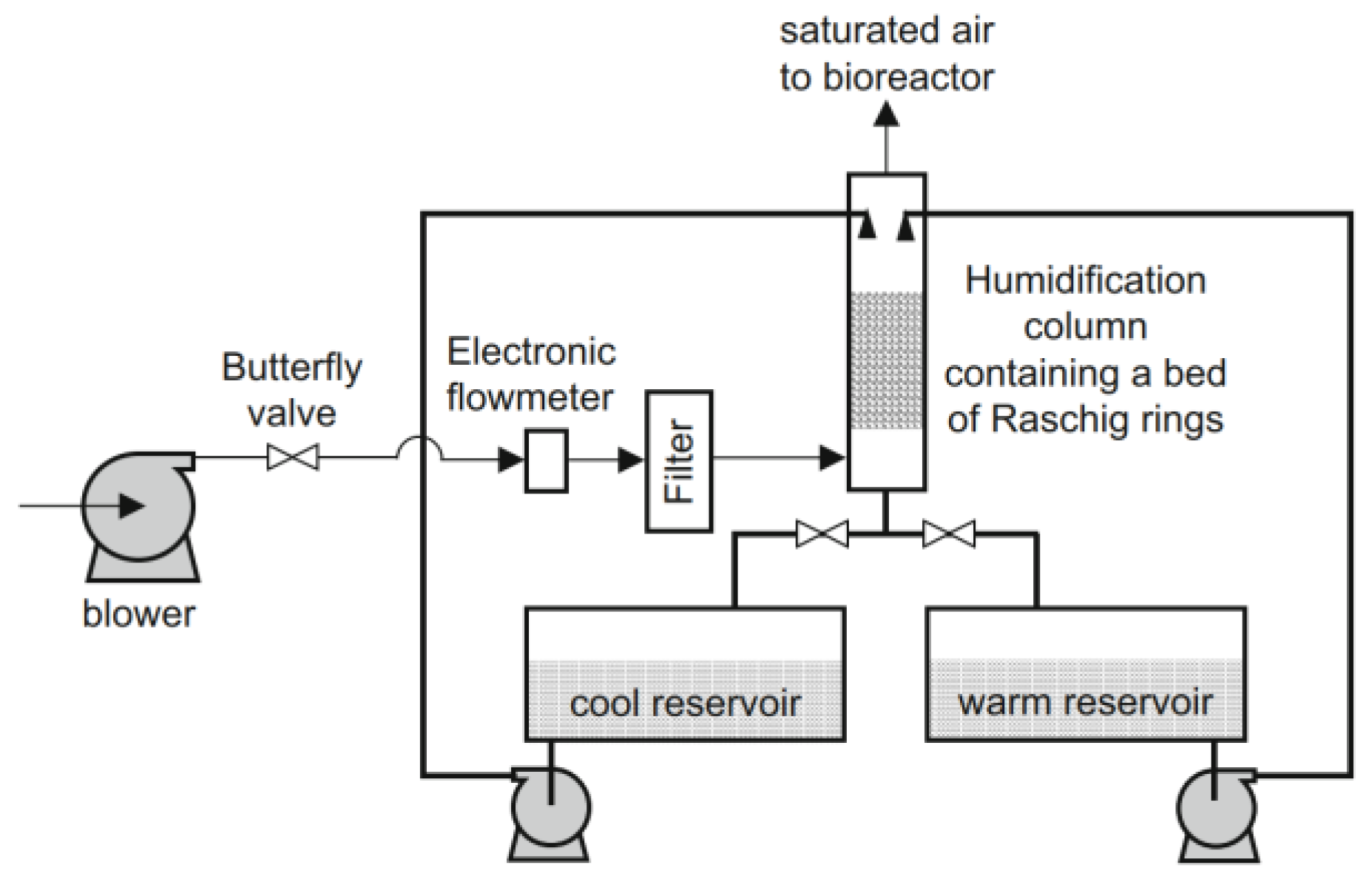

Figure 4. In the industrial practice of MFH solid fermentation, scaling up SSF for MFH is a challenge, which means it is mostly focused on flask or laboratory bioreactor scale. The shelf or bed manner of MFH solid fermentation is the preferred method because it is easy to scale up (

Figure 4). Furthermore, at the pilot scale, it is crucial to pay attention to a few aspects that are not typically problematic at the laboratory scale. For example, the pilot bioreactor requires a well-designed air preparation system. DA Mitchell and colleagues designed an effective air supply system with temperature regulation [

74]. The humidification column is capable of receiving water from either the cool reservoir or the warm reservoir. When one reservoir is working, the pump of the other reservoir is in standby mode, and the return valve of the other reservoir is closed. The temperature of reservoirs is maintained using heating coils controlled by thermostats (

Figure 5).

4.3.2. Liquid Fermentation

Compared with SSF, liquid fermentation has many advantages, such as higher automation, more efficient substrate and oxygen transfer rates, and more stable batch differences. Thus, MFH fermentation is better suited for modern liquid fermentation technology. For example, medicinal fungi such as

Ganoderma lucidum,

Poria cocos, and

Cordyceps militaris have been applied to produce the biomass or the medical substance, including polysaccharides, ganoderma acid, cordycepin, and pachyman in a large-scale liquid fermentation tank [

75]. As depicted in

Figure 4, the raw materials of MFH should be cut before being extracted with a water solvent. Liquid fermentation of MFH can improve the generation of active ingredients efficiently, and its fermentation scale can be easily expanded. The bacterial contamination is the most important challenge for the continual liquid fermentation of MFH, as most MFH lack antibacterial activity. Thus, liquid fermentation demands strict sterilization.

4.3.3. Single-, Bidirectional-, and Multispecies-Probiotic Fermentation

The most popular mode of fermentation is single-strain probiotic fermentation due to its clear metabolic characteristics, predictable metabolic components, and easy control of fermentation. The typical application of this mode involved modifying the structure of certain substrates from MFH through enzymatic catalysis of a single probiotic. The probiotic strains of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Yeast, and some medicinal fungi are often used for single-strain MFH fermentation. For example, the metabolites of Lonicera japonica fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum can alleviate osteoporosis through intestinal bacteria and serum metabolites [

76]. Moreover, SSF of

Purshia plicata with

A. niger GH1 can enhance the content of bioactive polyphenol compounds and present strong antioxidative properties [

8]. In addition to single-strain fermentation, there are other fermentation modes such as bidirectional fermentation and multispecies fermentation. Bidirectional fermentation is a special fermentation technology that utilizes medicinal fungi to ferment edible TCM or MFH substrates, which offers synergistic and complementary advantages and better pharmacological effects. When MFH substrates are fermented bidirectionally, medicinal fungi receive various nutrients, and fungal fermentation enhances the yield of the bioactive components of the substrates. In addition, this fermentation mode can produce a large number of new bioactive metabolites during fermentation. For instance, bidirectional SSF of fresh ginseng and G. lucidum mycelium could result in better immunomodulatory activity [

77]. Another study demonstrated that the bidirectional fermentation of Monascus and mulberry leaves enhanced the production of γ-aminobutyric acid and Monascus pigments, which can regulate blood lipid and improve sleep by decreasing blood lipid levels [

78].

Due to the synergistic effects of multiple probiotic strains, the multispecies-fermentation mode has attracted more and more attention and has been widely used in MFH fermentation. This mode can produce a diverse assortment of enzymes, including amylase, protease, lipase, cellulase, hemi-cellulase, chitinase, glucoamylase, pectinase, isomerase, and oxidoreductase. By using these enzymes, MFH substrate can be decomposed efficiently, bioactive ingredients can be produced more efficiently, and new pharmacological substances can be created. For example, fermentation of rose petals with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum B7 and Bacillus subtilis natto remarkably enhanced the levels of phenolic compounds, enzyme activity, and antioxidant capacity [

9]. Moreover, multispecies fermentation of

Cornus officinalis fruit (COF) with

Bifidobacterium bifidum and

Bacillus subtilis significantly increased the amount of gallic acid in the COF culture broth [

79]. In addition, the Ma group obtained high-quality mulberry juice with enhanced antioxidant capacity by fermenting it using five different probiotic strains [

80].

5. Quality Control of MFH Fermentation

Controllable quality and safety are paramount concerns during the process of probiotic-fermented MFH to prevent the reoccurrence of the 'Red Yeast Rice' incident caused by Kobayashi Pharmaceutical in Japan. Therefore, it is vital to have a process quality and risk control system, which can be achieved by introducing or integrating Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) into the MFH fermentation process.

5.1. Quality Control of MFH Raw Materials

Although MFHs are considered food materials, they do not require the same level of quality control as drugs, as required by the Pharmacopoeia in China. It is highly advisable to use the latest edition of the China Pharmacopoeia for probiotic fermentation to ensure quality standards meet origin identification, heavy metal residues, mycotoxins, and pesticide residues. In addition, the audit and investigation process for MFH suppliers needs to be improved by enterprises, and MFH management should be standardized throughout their entire life cycle, including purchasing, transportation, acceptance, inspection, transfer, and storage. For example, DNA barcode technology has been widely utilized to confirm the origin of TCM [

81,

82]. To assess the chemical quality consistency of Panax ginseng, a new method of quality control that is gene-based was developed by analyzing the whole genome, chloroplast genome, and ITS2 DNA barcode [

83]. Additionally, a portable near-infrared spectrometer was utilized to detect the major bioactive compounds in blueberry leaves and further determine the optimal harvest time [

84]. The application of modern detective methods and quality standards can effectively guarantee the quality of MFH. Furthermore, the process of "nine cycles of steaming-drying" for

Polygonati Rhizoma gives rise to health-promoting activities due to the abundant active metabolites, including alkaloids, amino acids and derivatives, flavonoids, organic acids, phenolic acids, and saccharides, which are detected by UPLC-MS/MS. The traditional processing of

Polygonata Rhizoma was confirmed as necessary and more efficient [

85].

In summary, the evaluation standard for the applicability of probiotic fermentation in MFH should be established. Additionally, it is necessary to have strict requirements for crucial control points like the origin of MFH, active component content, heavy metals, microorganisms, and pesticide residue limitation.

5.2. Screening of Adaptive Probiotics

Different types of MFH need to be adapted to different types of probiotics. Hence, screening adaptive probiotics is the primary and essential task. To begin with, the candidate probiotic strain must comply with safety standards, which suggests that the strain needs to be approved and recognized by regulatory authorities. In the case of a new species, it is necessary to identify and evaluate it by sequencing its entire genome and confirming its safety through experimental animal tests. For instance, the phenotypic and genomic analyses were used to verify and characterize

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus strain 484, a newly isolated strain derived from human milk. Moreover, the research shows that

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus 484 is a promising and safe probiotic candidate that has potential applications in both medical and food industries [

86].

In order to obtain an effective fermented MFH product, it is crucial to have probiotics that are both active and adaptable. The core microorganisms used in yogurt production and other fermented foods are LAB because they offer exact healthy functions and have a reliable safety profile. Moreover, LAB possess the ability to tolerate very low pH states and survive in acidic conditions in the stomach. In particular, certain Lactobacillus strains are also able to resist antibiotics [

87]. In the near future, LAB will continue to be the primary option for MFH fermentation. Additionally, filamentous fungi and yeast are significant probiotics in MFH fermentation.

In China, a group standard of 'General standard of probiotics for food use' was released by the Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology in 2022. In accordance with the standard, probiotics must be identified, assessed for safety and health function at the strain level, and evaluation items and methods should be chosen based on the strain's characteristics. The biological characteristics of probiotics, such as gastric acid tolerance, bile acid tolerance, human epithelial cell adhesion, conditional pathogenic bacteria antagonistic resistance, and bile salt hydrolase activity, should be evaluated. To assess the safety of probiotics, strains must be tested to determine their resistance to antibiotics, pathogenicity, hemolysis, toxin production, and other active substances [

88].

5.3. Development of Fine-Regulated Fermentation

Regulating the fermentation technology for the single-probiotic mode is relatively simple and mature. However, the process of bidirectional or multispecies-probiotic fermentation is complex. Ecological theory is applied to the design of multispecies probiotic fermentation, and the interaction between strains can be either negative or positive. For instance, one species can stop the growth of another species because of nutrient competition or chemical substances in metabolites. Conversely, one strain could enhance the growth of another strain by increasing the availability of nutrients and creating new niches. The interaction between strains is a result of one-way interaction between strains, and common interaction mechanisms include cross-feeding, functional complementarity, niche competition, and others [

89]. Cross-feeding refers to the cooperative relationship in which one microorganism depends on the metabolic activity of another microorganism and obtains the key factors needed for its growth. For instance, the co-cultivation of certain bifidobacterial strains with

B. bifidum PRL2010 causes enhanced metabolic activity, which results in increased lactate and/or acetate production. The presence of other bifidobacterial strains is beneficial to PRL2010 cells [

90]. Furthermore,

B. infantis engraftment, which is dependent on HMOs, correlates with an increase in lactate-consuming Veillonella, a faster acetate recovery, and changes in indolelactate and p-cresol sulfate, metabolites that affect host inflammation status. In addition, when Veillonella co-cultures with

B. infantis and HMO in vitro and in vivo, it transforms lactate produced by

B. infantis into propionate, which is a significant mediator of host physiology [

91]. High-density fermentation is no longer the main focus of fermentation optimization in probiotic-fermented MFH. Nevertheless, the aim is to investigate how probiotics interact with MFH and how they interact with each other, to enhance the physiological functions of fermented products. In this way, the ecological interaction theory provides theoretical guidelines for the probiotic fermentation of MFH.

6. Challenges of MFH Fermentation

Although the probiotic-fermented MFH has obvious advantages in contrast to that of the traditional MFH and more benefits for human health, exogenous contaminants, including pesticide residues, heavy metals, mycotoxins, sulfur dioxide residues, and microorganism contamination, pose significant risks in the application of the probiotic-fermented MFH. Environmental pollution, including soil, water, and air, is the primary cause of heavy residues in MFH. A study demonstrated that analysis of 1773 batches of samples from 86 kinds of TCM revealed 30.51% exceeded pharmacopoeia limitation for at least one heavy metal, with exceedance rates ranked Pb > Cd > As > Hg > Cu [

92]. Organochlorines, organophosphates, pyrethroids, carbamates, and neonicotinoids are the main types of pesticide residues found in MFH cultivation. Pesticide organochlorine and organophosphate had the highest detection frequencies among MFHs. Organochlorine residues are dominant in the perennial roots and rhizomes, while organophosphate is predominantly present in the overground parts such as flowers, leaves, and fruits [

93]. The accumulation of pesticides and heavy metals could cause physiological dysfunction in the human body, which could result in health problems, including cancer, genetic mutations, asthma, leukemia, and other diseases [

94].

The absolute dominance of the target bacterial community is necessary for the successful fermentation of MFH, just as in classical microbial fermentation. Consequently, it is a challenge to ensure sterile control of MFH fermentation. For example, the 'Red Yeast Rice' incident at Kobayashi Pharmaceutical in Japan was a painful lesson. Red yeast rice is a typical fermentation product that uses rice as the main raw material. However, during the fermentation process of the product of this incident, the toxic compound 'penicillic acid', which may be produced by Penicillium contamination, was detected, causing serious kidney damage and even death to consumers [

95]. Furthermore, it was reported that the fruit enzymes, commonly known as Jiaosu in Chinese, caused diarrhea, which is the typical symptom of miscellaneous bacterial contamination [

96].

The determination of optimal fermentation systems and parameters is still a challenge, except for exogenous contamination. The dynamic system of probiotic fermentation-fermented MFH is complicated because it is dependent on the type of probiotic, supplemental medium, fermentation time, temperature, pH, ventilation level, and inoculum amount. How to effectively identify the optimal fermentation conditions for each practical probiotic-MFH fermentation case is always a difficult and complicated task, which requires a comprehensive study of the best conditions.

7. Perspective of MFH Fermentation

7.1. From Screening to Creating Probiotics for Fermentation

The majority of probiotics utilized in MFH fermentation are derived from traditional fermented foods and the livestock gut microbiota. The range of probiotics is extremely limited, and is primarily comprised of LAB, edible filamentous fungi, and yeasts. The development of synthetic biology and artificial intelligence (AI) has resulted in the emergence and application of novel microbiological technology, integrated AI design, genetic editing, and high-throughput screening, which has been continuously increasing [

97,

98]. Thus, the conventional screening of probiotics will be replaced with the direct creation and development of engineered probiotics. For example, the phage RecT/RecE-mediated recombineering and CRISPR/Cas counter-selection can achieve the scarless point edits, seamless deletions, and multi-kilobase insertions in probiotics for therapeutic applications [

99,

100]. An engineered probiotic

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) that stably expresses interleukin-18 binding protein (IL-18BP) was created and can be used to successfully treat human ulcerative colitis [

101]. Thus, it is of great importance to develop efficient and safe probiotic strains.

7.2. Establishment of a Quality Standard System

The recognition of TCM for the prevention and treatment of health problems or diseases worldwide has increased after the COVID-19 pandemic. An innovative and effective health product is the probiotic-fermented MFH, which perfectly combines modern biotechnology and TCM. It is a significant way to achieve the modernization of TCM. The lack of a quality standard system is a major impediment to the development of MFH fermentation. Recently, there have been several standards and expert consensus related to probiotics that have been released and published. A consensus of experts stated that the combination of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus powder/capsule can be used for digestive system diseases [

102]. Moreover, the industry standard of “Edible composite Jiaosu” was issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People's Republic of China (QB/T 5760-2023, in Chinese), which can guide the fermentation of MFH. Furthermore, it is imperative to create innovative fermentation strategies that can regulate the generation pathway of active ingredients of probiotics for MFH fermentation. In addition, a standard fermentation process must be created that incorporates process parameters, product quality, and inspection methods.

7.3. Application of AI in MFH Fermentation

If AI technology is used in the probiotic fermentation of MFH, it will overcome the limitations of traditional humidity experiments and enable effective prediction of the complex interactions between microbial communities and the substrate of MFH. AI has had a significant impact on the research and application of probiotics up until now. By using a deep learning tool, a method was developed to predict metabolite responses to dietary interventions based on individuals' gut microbial compositions [

103]. A study developed an AI model to recommend the combination of probiotic strains to improve the intestinal health of the individual by analyzing the association pattern between the intestinal flora composition of an individual and the specific metabolite short-chain fatty acids [

104]. In addition, AI technology can combine metagenomics and metatranscriptomics data to predict how microbial functional genes are expressed, which is useful for evaluating the impact of probiotics on different physiological states [

105].

To sum it up, there have been many previous studies that have shown that probiotic-fermented MFH has significant effects on human health. These benefits cannot be solely attributed to MFH or functional probiotics, but the interaction between probiotics and MFH is also a factor. In spite of this, systematic and in-depth research is still required to enhance its efficacy after MFH fermentation. The use of diverse probiotics during MFH fermentation leads to a range of compositions and functional changes, which require additional efforts to determine their regularity. In addition, fermented MFH is also exposed to health and safety risks, especially during the fermentation process, whether risky substances are produced or other microbiological contamination, which requires improved safety assays and quality control of the fermentation process. The combination of modern technologies helps to break through the limitations of traditional technologies, such as combining high-throughput screening, synthetic biology, and AI techniques to mine or create new probiotic strains to improve fermentation efficiency, and the use of molecular biology and deep learning techniques is expected to personalize probiotic-fermented MFH-based functional foods for the person of desire.

Probiotic-fermented MFH has value beyond just improving the safety and efficacy of MFH, as it redefines the boundary between 'food' and 'medicine'. It is certain that probiotic-fermented MFH will shift from niche products to mass-consumer functional foods, allowing individuals to benefit from their daily diets.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., Y.C. and H.D.; methodology, D.B. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B., Y.C. and W.G.; writing—review and editing, F.H. and H.D.; supervision, H.D.; project administration, F.H. and H.D.; funding acquisition, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shandong Province Science and Technology-based Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Innovation Capacity Enhancement Project (2024TSGC0896).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Science & Technology of Shandong Province for their funding support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, L. "Am I in 'Suboptimal Health'?": The Narratives and Rhetoric in Carving out the Grey Area Between Health and Illness in Everyday Life. Sociol Health Illn 2025, 47, e70005. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Kong, K.W.; Xiang, P.; He, X.; Zhang, X. Probiotic fermentation improves the bioactivities and bioaccessibility of polyphenols in Dendrobium officinale under in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion and fecal fermentation. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1005912. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, R.; Ouyang, S.; Liang, W.; Duan, J.; Gong, W.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Kurihara, H.; et al. "Weibing" in traditional Chinese medicine-biological basis and mathematical representation of disease-susceptible state. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025, 15, 2363-2371. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.H.; Zhu, S.R.; Duan, W.J.; Ma, X.H.; Luo, X.; Liu, B.; Kurihara, H.; Li, Y.F.; Chen, J.X.; He, R.R. "Shanghuo" increases disease susceptibility: Modern significance of an old TCM theory. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 250, 112491. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tao, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xu, W.; Huang, X.; Wei, H.; Tao, X. Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) Leaf-Fermentation Supernatant Inhibits Adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes and Suppresses Obesity in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Mo, Q.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Zhong, H.; Feng, F. Enhancement in the metabolic profile of sea buckthorn juice via fermentation for its better efficacy on attenuating diet-induced metabolic syndrome by targeting gut microbiota. Food Res Int 2022, 162, 111948. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Yeboah, P.J.; Ayivi, R.D.; Eddin, A.S.; Wijemanna, N.D.; Paidari, S.; Bakhshayesh, R.V. A review and comparative perspective on health benefits of probiotic and fermented foods. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2023, 58, 4948-4964. [CrossRef]

- Jose Carlos, L.M.; Leonardo, S.; Jesus, M.C.; Paola, M.R.; Alejandro, Z.C.; Juan, A.V.; Cristobal Noe, A. Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus niger GH1 to Enhance Polyphenolic Content and Antioxidative Activity of Castilla Rose (Purshia plicata). Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Qin, C.Q.; Li, T.T.; Liu, W.H.; Ren, D.F. Fermentation of rose residue by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum B7 and Bacillus subtilis natto promotes polyphenol content and beneficial bioactivity. J Biosci Bioeng 2022, 134, 501-507. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Miao, S. Increases of Lipophilic Antioxidants and Anticancer Activity of Coix Seed Fermented by Monascus purpureus. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.C.; Lin, S.P.; Yu, C.P.; Chiang, H.M. Comparison of Puerariae Radix and its hydrolysate on stimulation of hyaluronic acid production in NHEK cells. Am J Chin Med 2010, 38, 143-155. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yin, X.; Fang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Peng, F. Effect of Limosilactobacillus fermentum NCU001464 fermentation on physicochemical properties, xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity and flavor profile of Pueraria Lobata. Food Chem 2025, 476, 143490. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.S.; Shin, K.C.; Oh, D.K. Production of ginsenoside compound K from American ginseng extract by fed-batch culture of Aspergillus tubingensis. AMB Express 2023, 13, 64. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.S.; Kim, M.J.; Shin, K.C.; Oh, D.K. Increased Production of Ginsenoside Compound K by Optimizing the Feeding of American Ginseng Extract during Fermentation by Aspergillus tubingensis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 32, 902-910. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Kang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, C.; Hao, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; Jia, S.; Yi, J. Antioxidant properties and digestion behaviors of polysaccharides from Chinese yam fermented by Saccharomyces boulardii. LWT 2022, 154, 112752. [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Shan, H.; Xueru, L.; Bo, Z.; Tao, M. Study on Conversion of Conjugated Anthraquinone in Radix et Rhizoma Rhei by Yeast Strain. Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica-World Science and Technology 2013.

- Dai, W.S.; Zhao, R.H. Effect of fermentation on the anthraquinones content in Radix et Rhizoma Rhei. 2005.

- Guo, N.; Song, X.-R.; Kou, P.; Zang, Y.-P.; Jiao, J.; Efferth, T.; Liu, Z.-M.; Fu, Y.-J. Optimization of fermentation parameters with magnetically immobilized Bacillus natto on Ginkgo seeds and evaluation of bioactivity and safety. LWT 2018, 97, 172-179. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Lim, J.M.; Jeong, H.J.; Lee, G.M.; Seralathan, K.K.; Park, J.H.; Oh, B.T. Lead (Pb) removal and suppression of Pb-induced inflammation by Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus A6-6. Lett Appl Microbiol 2025, 78. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, H. Biosorption of Heavy Metals by Lactic Acid Bacteria for Detoxification. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2851, 201-212. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Ren, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. The Involvement of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Exopolysaccharides in the Biosorption and Detoxication of Heavy Metals in the Gut. Biol Trace Elem Res 2024, 202, 671-684. [CrossRef]

- Halttunen, T.; Salminen, S.; Tahvonen, R. Rapid removal of lead and cadmium from water by specific lactic acid bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2007, 114, 30-35. [CrossRef]

- Teemu, H.; Seppo, S.; Jussi, M.; Raija, T.; Kalle, L. Reversible surface binding of cadmium and lead by lactic acid and bifidobacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2008, 125, 170-175. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Sinha, V.; Kannan, A.; Upreti, R.K. Reduction of Chromium-VI by Chromium Resistant Lactobacilli: A Prospective Bacterium for Bioremediation. Toxicol Int 2012, 19, 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhai, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Narbad, A.; Zhang, H.; Tian, F.; Chen, W. Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM639 alleviates aluminium toxicity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 1891-1900. [CrossRef]

- Mirza Alizadeh, A.; Hosseini, H.; Mohseni, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Hashempour-Baltork, F.; Hosseini, M.J.; Eskandari, S.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Aminzare, M. Bioremoval of lead (pb) salts from synbiotic milk by lactic acid bacteria. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 9101. [CrossRef]

- Labus, J.; Tang, K.; Henklein, P.; Krüger, U.; Hofmann, A.; Hondke, S.; Wöltje, K.; Freund, C.; Lucka, L.; Danker, K. The α(1) integrin cytoplasmic tail interacts with phosphoinositides and interferes with Akt activation. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2024, 1866, 184257. [CrossRef]

- Gopal, A.; Swamidason, J.; Mariappan, P.; Bojan, V. Microbial degradation of flubendiamide in different types of soils at tropical region using lactic acid bacteria formulation. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 29271. [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Zhao, M.; Xia, T.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Qiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Lv, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M. Effect of Different Fermentation Methods on the Physicochemical, Bioactive and Volatile Characteristics of Wolfberry Vinegar. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, L.; Tang, J.; Xiang, W. Characterization of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing Saccharomyces cerevisiae and coculture with Lactobacillus plantarum for mulberry beverage brewing. J Biosci Bioeng 2020, 129, 447-453. [CrossRef]

- Kanklai, J.; Somwong, T.C.; Rungsirivanich, P.; Thongwai, N. Screening of GABA-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria from Thai Fermented Foods and Probiotic Potential of Levilactobacillus brevis F064A for GABA-Fermented Mulberry Juice Production. Microorganisms 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, K.; Douglass, H.; Erritzoe, D.; Muthukumaraswamy, S.; Nutt, D.; Sumner, R. The role of GABA, glutamate, and Glx levels in treatment of major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2025, 141, 111455. [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.C.; Yoon, Y.; Yoo, H.S.; Oh, S. Effect of Lactobacillus Fermentation on the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Turmeric. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 29, 1561-1569. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; He, X.; Xu, K.; Xue, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X. Platycodon grandiflorum root fermentation broth reduces inflammation in a mouse IBD model through the AMPK/NF-kappaB/NLRP3 pathway. Food Funct 2022, 13, 3946-3956. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Kang, C.-H.; Hwang, H.S. Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Astragalus membranaceus Fermented by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cells. Fermentation 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Liu, S.; Ai, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y. Fermented ginseng attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses by activating the TLR4/MAPK signaling pathway and remediating gut barrier. Food Funct 2021, 12, 852-861. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, H.; Liu, H.; Cheng, H.; Pan, L.; Hu, M.; Li, X. Goji berry juice fermented by probiotics attenuates dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Journal of Functional Foods 2021, 83, 104491. [CrossRef]

- Oh, N.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, Y. Mulberry leaf extract fermented with Lactobacillus acidophilus A4 ameliorates 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis in rats. Lett Appl Microbiol 2017, 64, 459-468. [CrossRef]

- El-Sohaimy, S.A.; Shehata, M.G.; Mathur, A.; Darwish, A.G.; Abd El-Aziz, N.M.; Gauba, P.; Upadhyay, P. Nutritional Evaluation of Sea Buckthorn “Hippophae rhamnoides” Berries and the Pharmaceutical Potential of the Fermented Juice. Fermentation 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.P.; Capozzi, V.; Russo, P.; Drider, D.; Spano, G.; Fiocco, D. Immunobiosis and probiosis: antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria with a focus on their antiviral and antifungal properties. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 9949-9958. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.M.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; Cotter, P.D. Antimicrobial antagonists against food pathogens: a bacteriocin perspective. Current Opinion in Food Science 2015, 2, 51-57. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.M.; Yi, S.J.; Cho, I.J.; Ku, S.K. Red-koji fermented red ginseng ameliorates high fat diet-induced metabolic disorders in mice. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4316-4332. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Bao, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Zhou, L.; Fu, Q. Fermented Gynochthodes officinalis (F.C.How) Razafim. & B.Bremer alleviates diabetic erectile dysfunction by attenuating oxidative stress and regulating PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 307, 116249. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Shang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Xue, N.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Li, J. Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Activity of Polygonatum sibiricum Fermented with Lactobacillus brevis YM 1301 in Diabetic C57BL/6 Mice. J Med Food 2021, 24, 720-731. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qu, Q.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, P.; Han, L.; Shi, X. Monascus ruber fermented Panax ginseng ameliorates lipid metabolism disorders and modulate gut microbiota in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 278, 114300. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; You, Y.; Ai, Z.; Dai, W.; Piao, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Fermented ginseng improved alcohol liver injury in association with changes in the gut microbiota of mice. Food Funct 2019, 10, 5566-5573. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Z.; Han, L.; Shi, X. Paecilomyces cicadae-fermented Radix astragali activates podocyte autophagy by attenuating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways to protect against diabetic nephropathy in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 129, 110479. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jung, J.E.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J.; Kim, H.Y. Effects of the fermented Zizyphus jujuba in the amyloid beta(25-35)-induced Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Nutr Res Pract 2021, 15, 173-186. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, H.; Ma, R.; Ma, J.; Fang, H. Fermentation by Multiple Bacterial Strains Improves the Production of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Goji Juice. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Liu, L.; Lai, T.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Z.; Xiao, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, M. Phenolic profile, free amino acids composition and antioxidant potential of dried longan fermented by lactic acid bacteria. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 4782-4791. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; You, S.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, M. Protection Impacts of Coix lachryma-jobi L. Seed Lactobacillus reuteri Fermentation Broth on Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Yamano, S.; Imagawa, N.; Igami, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Ito, H.; Watanabe, T.; Kubota, K.; Katsurabayashi, S.; Iwasaki, K. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei A221-fermented ginseng on impaired spatial memory in a rat model with cerebral ischemia and β-amyloid injection. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2019, 6, 96-104. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-Y.; Choi, J.W.; Park, Y.; Oh, M.S.; Ha, S.K. Fermentation enhances the neuroprotective effect of shogaol-enriched ginger extract via an increase in 6-paradol content. Journal of Functional Foods 2016, 21, 147-152. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Qi, H.; Tang, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Kong, Z.; Jia, S.; et al. Probiotic fermentation of Ganoderma lucidum fruiting body extracts promoted its immunostimulatory activity in mice with dexamethasone-induced immunosuppression. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 141, 111909. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Rui, B.; Du, Y.; Lei, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Yuan, D.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; et al. Probiotic Fermentation of Astragalus membranaceus and Raphani Semen Ameliorates Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression Through Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Dependent or -Independent Regulation of B Cell Function. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, M.; Li, R.; Qu, Q.; Li, Z.; Feng, M.; Tian, Y.; Ren, W.; et al. Exploring the Prebiotic Potential of Fermented Astragalus Polysaccharides on Gut Microbiota Regulation In Vitro. Curr Microbiol 2024, 82, 52. [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Guo, C.E.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Qian, J.; Li, H. Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) fermentation liquid protects against alcoholic liver disease linked to regulation of liver metabolome and the abundance of gut microbiota. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 2846-2854. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Chu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, S.; Zogona, D.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Lactobacillus casei Fermented Raspberry Juice In Vitro and In Vivo. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zhou, L.; Ren, Y.; Liu, F.; Xue, Y.; Wang, F.Z.; Lu, R.; Zhang, X.J.; Shi, J.S.; Xu, Z.H.; et al. Lactic acid fermentation of goji berries (Lycium barbarum) prevents acute alcohol liver injury and modulates gut microbiota and metabolites in mice. Food Funct 2024, 15, 1612-1626. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; et al. Fermented Astragalus and its metabolites regulate inflammatory status and gut microbiota to repair intestinal barrier damage in dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1035912. [CrossRef]

- Ratzinger, S.; Grässel S Fau - Dowejko, A.; Dowejko A Fau - Reichert, T.E.; Reichert Te Fau - Bauer, R.J.; Bauer, R.J. Induction of type XVI collagen expression facilitates proliferation of oral cancer cells. Matrix Biol 2011, 30, 118-125. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.I.; Song, W.S.; Oh, D.K. Enhanced production of ginsenoside compound K by synergistic conversion of fermentation with Aspergillus tubingensis and commercial cellulase. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1538031. [CrossRef]

- Lodi, R.S.; Dong, X.; Jiang, C.; Sun, Z.; Deng, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Mesa, A.; Huang, X.; et al. Antimicrobial activity and enzymatic analysis of endophytes isolated from Codonopsis pilosula. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2023, 99. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, Y.; He, W.; Song, X.; Peng, Y.; Hu, X.; Bian, S.; Li, Y.; Nie, S.; Yin, J.; et al. Exploring the Biogenic Transformation Mechanism of Polyphenols by Lactobacillus plantarum NCU137 Fermentation and Its Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties in Wolfberry Juice. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 12752-12761. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Xiong, L.; Hu, H.; Liu, H. Lactobacillus acidophilus-Fermented Jujube Juice Ameliorates Chronic Liver Injury in Mice via Inhibiting Apoptosis and Improving the Intestinal Microecology. Mol Nutr Food Res 2024, 68, e2300334. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Guo, F.; Li, C.; Xiang, D.; Gong, M.; Yi, H.; Chen, L.; Yan, L.; Zhang, D.; Dai, L.; et al. Aqueous extract of fermented Eucommia ulmoides leaves alleviates hyperlipidemia by maintaining gut homeostasis and modulating metabolism in high-fat diet fed rats. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155291. [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.F.; Yu, W.N.; Zhang, B.L. Manufacture and antibacterial characteristics of Eucommia ulmoides leaves vinegar. Food Sci Biotechnol 2020, 29, 657-665. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; Zhang, K.Q.; Shen, Y.M. [The fermentation of 50 kinds of TCMs by Bacillus subtilis and the assay of antibacterial activities of fermented products]. Zhong Yao Cai 2006, 29, 154-157.

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Hong, Y.; Liang, P.; Kwok, L.Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. iProbiotics: a machine learning platform for rapid identification of probiotic properties from whole-genome primary sequences. Brief Bioinform 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, M.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Zhong, Z.; Kwok, L.Y.; Dong, G.; Sun, Z. Predicting Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus-Streptococcus thermophilus interactions based on a highly accurate semi-supervised learning method. Sci China Life Sci 2025, 68, 558-574. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Song, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; An, X.; Qi, J. The effects of solid-state fermentation on the content, composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of flavonoids from dandelion. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0239076. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, G.; Ling, J. New flavonoid and their anti-A549 cell activity from the bi-directional solid fermentation products of Astragalus membranaceus and Cordyceps kyushuensis. Fitoterapia 2024, 176, 106013. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Gurumurthy, K. An overview of probiotic health booster-kombucha tea. Chin Herb Med 2023, 15, 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Pitol, L.O.; Biz, A.; Finkler, A.T.J.; de Lima Luz, L.F., Jr.; Krieger, N. Design and Operation of a Pilot-Scale Packed-Bed Bioreactor for the Production of Enzymes by Solid-State Fermentation. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 2019, 169, 27-50. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhao, L.; Chen, L.; Shi, G.; Ding, Z. Refined regulation of polysaccharide biosynthesis in edible and medicinal fungi: From pathways to production. Carbohydr Polym 2025, 358, 123560. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, W.; Luo, J.; Liu, L.; Peng, X. Lonicera japonica Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum Improve Multiple Patterns Driven Osteoporosis. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Suh, H.J.; Kang, C.M.; Lee, K.H.; Hwang, J.H.; Yu, K.W. Immunological activity of ginseng is enhanced by solid-state culture with Ganoderma lucidum mycelium. J Med Food 2014, 17, 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Jia, J.; Wu, Q. Bidirectional fermentation of Monascus and Mulberry leaves enhances GABA and pigment contents: establishment of strategy, studies of bioactivity and mechanistic. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2024, 54, 73-85. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, L.; Xu, G. Bacillus subtilis and Bifidobacteria bifidum Fermentation Effects on Various Active Ingredient Contents in Cornus officinalis Fruit. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, S.; Gouda, M.M.; Mubeen, B.; Imtiaz, A.; Murtaza, M.S.; Awan, K.A.; Rehman, A.; Alsulami, T.; Khalifa, I.; Ma, Y. Synergistic enhancement in the mulberry juice's antioxidant activity by using lactic acid bacteria co-culture fermentation. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 19453. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yan, L.; Jing, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Y. Insights into traditional Chinese medicine: molecular identification of black-spotted tokay gecko, Gekko reevesii, and related species used as counterfeits based on mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene sequences. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal 2025, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mei, R.; Zhao, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Surface enhanced Raman scattering tag enabled ultrasensitive molecular identification of Hippocampus trimaculatus based on DNA barcoding. Talanta 2025, 294, 128289. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Liao, X.; Xi, Y.; Chu, Y.; Liu, S.; Su, H.; Dou, D.; Xu, J.; Xiao, S. Screening and Application of DNA Markers for Novel Quality Consistency Evaluation in Panax ginseng. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gan, X.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Li, T.; et al. Seasonal variation of antioxidant bioactive compounds in southern highbush blueberry leaves and non-destructive quality prediction in situ by a portable near-infrared spectrometer. Food Chem 2024, 457, 139925. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, F.; Hu, R.; Wan, X.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Ho, C.T.; Li, S. Dynamic Variation of Secondary Metabolites from Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua Rhizomes During Repeated Steaming-Drying Processes. Molecules 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, N.; Jankowska, M.; Nawrot, S.; Nogal-Nowak, K.; Wasik, S.; Czerwonka, G. Phenotypic and Genetic Characterization and Production Abilities of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Strain 484-A New Probiotic Strain Isolated From Human Breast Milk. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13, e70980. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Bi, C. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Insights into Its Genetic Diversity, Metabolic Function, and Antibiotic Resistance. Genes (Basel) 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Release of Group Standard of General Principles of Probiotics for Food. CHINA FOOD 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Maldonado-Gomez, M.X.; Martinez, I. To engraft or not to engraft: an ecological framework for gut microbiome modulation with live microbes. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018, 49, 129-139. [CrossRef]

- Turroni, F.; Ozcan, E.; Milani, C.; Mancabelli, L.; Viappiani, A.; van Sinderen, D.; Sela, D.A.; Ventura, M. Glycan cross-feeding activities between bifidobacteria under in vitro conditions. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 1030. [CrossRef]

- Button, J.E.; Cosetta, C.M.; Reens, A.L.; Brooker, S.L.; Rowan-Nash, A.D.; Lavin, R.C.; Saur, R.; Zheng, S.; Autran, C.A.; Lee, M.L.; et al. Precision modulation of dysbiotic adult microbiomes with a human-milk-derived synbiotic reshapes gut microbial composition and metabolites. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1523-1538 e1510. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Heavy Metal Contaminations in Herbal Medicines: Determination, Comprehensive Risk Assessments, and Solutions. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 595335. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Zhang, W.S.; Wu, J.S.; Xin, W.F. [Research progress of pesticide residues in traditional Chinese medicines]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 48-52. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pant, K.; Brar, D.S.; Thakur, A.; Nanda, V. A review on Api-products: current scenario of potential contaminants and their food safety concerns. Food Control 2023, 145, 109499. [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kodama, K.; Sengoku, S. The Co-Evolution of Markets and Regulation in the Japanese Functional Food Industry: Balancing Risk and Benefit. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Galai, K.E.; Dai, W.; Qian, C.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, M.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Isolation of an endophytic yeast for improving the antibacterial activity of water chestnut Jiaosu: Focus on variation of microbial communities. Enzyme Microb Technol 2025, 184, 110584. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Gan, Q.; Ruan, W.; Liu, T.; Yan, Y. Leveraging artificial intelligence for efficient microbial production. Bioresour Technol 2025, 439, 133286. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yin, J.; Ding, L.; Li, P.; Xiao, H.; Gu, Q.; Han, J. New perspectives on key bioactive molecules of lactic acid bacteria: integrating targeted screening, key gene exploration and functional evaluation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2025, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Shaposhnikov, L.A.; Rozanov, A.S.; Sazonov, A.E. Genome-Editing Tools for Lactic Acid Bacteria: Past Achievements, Current Platforms, and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, R.; Zarimeidani, F.; Ghanbari Boroujeni, M.R.; Sadighbathi, S.; Kashaniasl, Z.; Saleh, M.; Alipourfard, I. CRISPR-Assisted Probiotic and In Situ Engineering of Gut Microbiota: A Prospect to Modification of Metabolic Disorders. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2025. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Gong, Z.; Jiang, J.H.; Chu, X. Engineered Probiotics Secreting IL-18BP and Armed with Dual Single-Atom Catalysts for Synergistic Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025, 17, 50337-50348. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xie, W. Chinese expert consensus on the application of live combined Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus powder/capsule in digestive system diseases (2021). J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 38, 1089-1098. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Holscher, H.D.; Maslov, S.; Hu, F.B.; Weiss, S.T.; Liu, Y.Y. Predicting metabolite response to dietary intervention using deep learning. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 815. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Piao, X.; Mahfuz, S.; Long, S.; Wang, J. The interaction among gut microbes,the intestinal barrier and short chain fatty acids. Animal Nutrition 2022, 9, 159-174.

- Bikel, S.; Valdez-Lara, A.; Cornejo-Granados, F.; Rico, K.; Canizales-Quinteros, S.; Soberón, X.; Del Pozo-Yauner, L.; Ochoa-Leyva, A. Combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics and viromics to explore novel microbial interactions: towards a systems-level understanding of human microbiome. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2015, 13, 390-401. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).