1. Introduction

Asserting program correctness is an important part of software development, and by far the most common strategy is using software testing, i.e., executing a program with certain inputs and asserting that the actual reached state is what is expected [

1]. It is well known that the software testing part takes major resources in development processes [

2]. The testing can occur at different levels, e.g., component testing, integration testing and unit testing. The latter refers to the verification of small, isolated units of a larger program [

3]. The purpose of unit testing is to verify the components on a low level such that when a test fails it is clear where the fault lies (i.e., the fault is in the test component and not due to an interaction with another part of the program). Traditionally, unit testing is accomplished by writing unit tests in the same language as the source code, and with a unit testing framework execute the system under test (SUT) and observe that the resulting state is as the test requires. Writing such tests can be a tedious task and guaranteeing isolation of the unit can require lots of effort. In discussion with industrial partners it was established that major time was spent stubbing code to achieve this. Therefore it is interesting to find methods to assist in this task.

On the other hand, there are formal approaches which attempts to

prove a program correct, via translation to a formal model and an automated reasoning tool. Such methods can also be applied to a unit level, thus verifying the behaviour of a smaller component. These approaches are powerful in the sense that (in the words of Dijkstra) ”

program testing can be a very effective way to show the presence of bugs, but is hopelessly inadequate for showing their absence” [

4]. Applying formal tools (e.g., model checkers and theorem provers) to verify software is an active research area with annual conferences and competitions [

5]. However, these approaches have barriers to adoption, e.g., requiring expert education in formal methods or great tool integration [

6]. Therefore, it is worthwhile to find means of making formal approaches more accessible by non-experts.Recently, there have been several successful applications of formal approach on a unit level, e.g., of Amazon Web Services [

7] and the Linux kernel [

8]. However, they still require knowledge about the underlying technology and the relationship to ordinary software testing is informal. These aspects leads us to a research inquiry as follows:

Research question: How can formal methods be leveraged for unit testing in a manner which is clearly defined and more accessible to non-experts?

We attempt to address in this paper by outlining the concept of

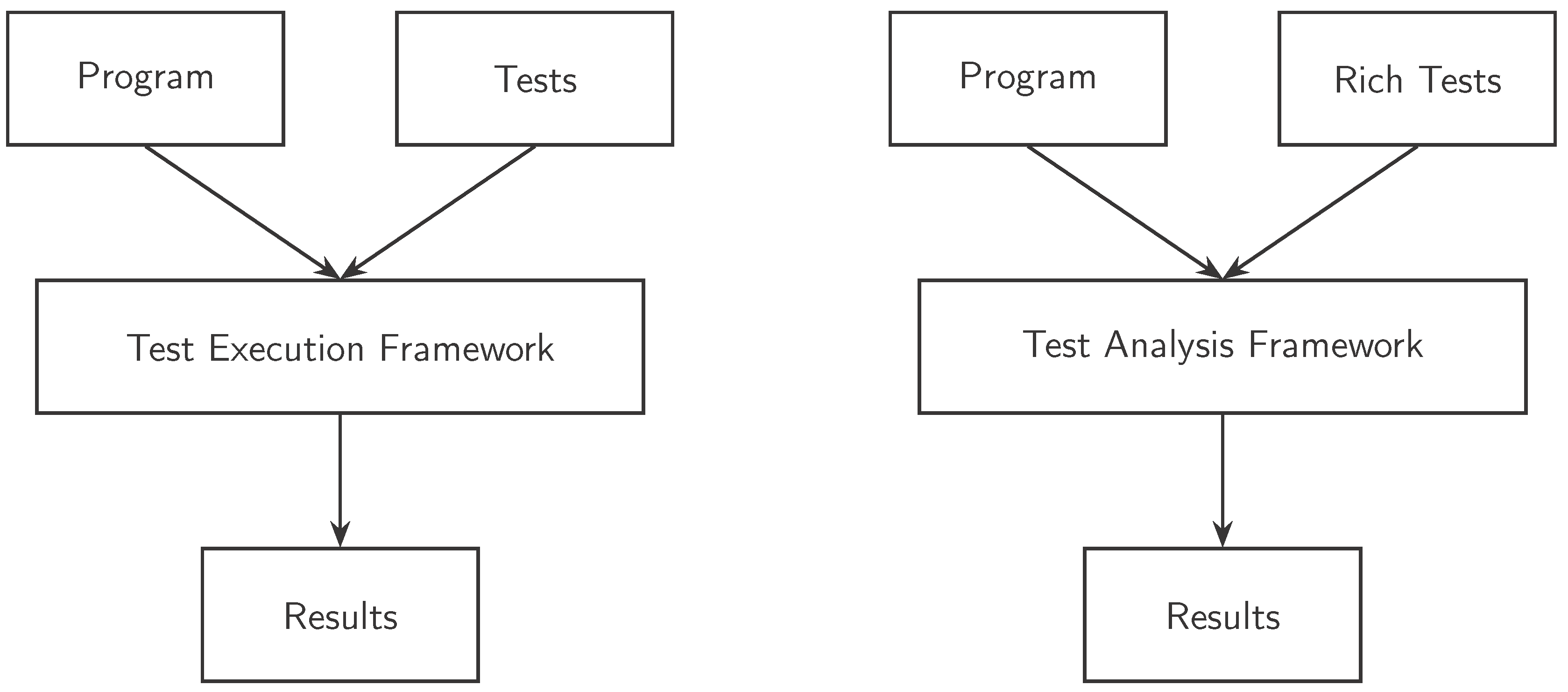

test analysis, which is an approach towards program verification that combines (normal) testing and formal methods. Ordinarily, a software test is (compiled and) executed to determine its outcome (pass or fail). We propose an alternative approach,

test analysis, where instead a formal analysis is applied to determine if the test passes or fails.

1 In this work, we do not apply formal tools to establish full formal verification of software, but instead partial verification of units. While earlier work have been using formal tools directly, we propose the introduction of (middle-layer) framework – a

test analysis framework – with the goal of making the underlying formal techniques more accessible by non-expert user (e.g., software testers without experience of formal tools) through the introduction of rich testing templates. Furthermore, by the usage of syntactic restrictions of test to our template

rich tests, we can enable novel extensions (enrichments) to the framework, in this paper exemplified by

property-based stubbing and

non-deterministic string values. In sum, we present the following contributions:

The introduction and formalization of test analysis and rich tests,

a prototype implementation working with rich tests for C code using CBMC,

-

Two enrichments:

- -

Enrichment 1: introduction of property-based stubs,

- -

Enrichment 2: regular expression specification of string values,

and a few select examples demonstrating the capabilities of the approach.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 gives background information before the formalization of test analysis and rich tests in

Section 3. After this we introduce our framework

rUnit in

Section 4 followed by a presentation of two enrichments: property-based stubbing in

Section 5 and non-deterministic string values in

Section 6. We consider related work in

Section 7 and present a few selected examples in

Section 8. Finally we conclude in

Section 9 with discussions of future work.

2. Background

Before presenting test analysis we introduce some preliminary background material on software testing and formal methods.

2.1. Software Testing

Software testing is the process of asserting program correctness by the means of executing it under certain conditions and observing the outcome (see, e.g., [

9]). Testing can be done on various levels, e.g., integration level testing, component testing or unit testing.

Unit testing refers to testing individual units of the software in isolation [

3]. Unit tests are often considered to consist of

phases [

10]:

arrange,

act and

assert. During arrange, an initial state is established for the test, to which the act phase then performs the execution of the inspected part. The assert phase finally checks if the test passes or fails. There is sometimes also a clean-up (a.k.a. tear-down) phase, which restores the program state.

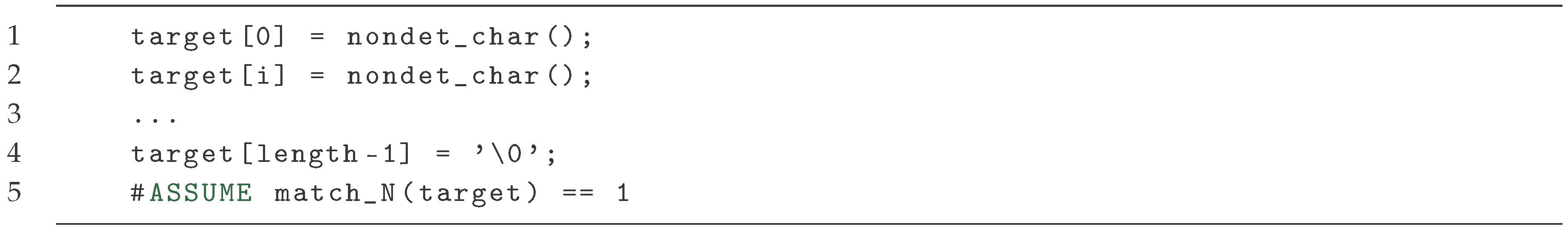

Example 1.

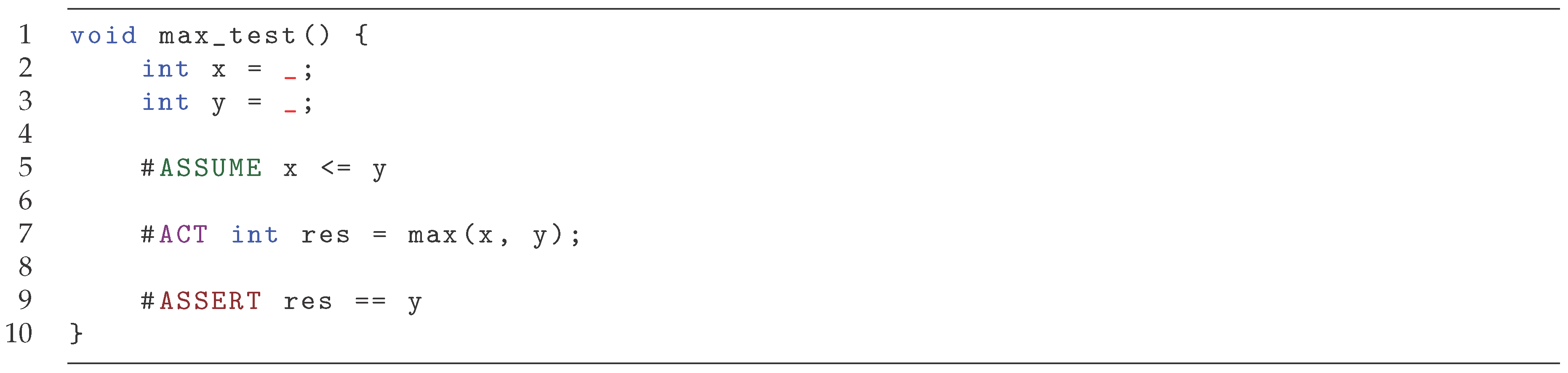

In Figure 1 a simple unit test is provided, testing the max function (which returns the greater of its arguments). The arrange phase initializes the values of a and b, the act phase calls the tested function max, and the assert phase ensures that the res is equal to b (as that is the greater of the two values).

When performing unit testing, the goal is to test the unit in isolation. Thus it is desirable to remove external dependencies. There are two main schools of unit testing on how to achieve this: London and Detroit (also known as Chicago or Classical). The schools difference can be highlighted through their definition of a unit. In the Detroit school, a unit is a unit of behaviour, which might include code from different modules interacting which each other. On the other hand, in the London school, a unit is a a piece of code (e.g., a class or a function). In the London school, the focus lies in asserting that the unit of code is interacting in the correct manner with the code around it and There is a heavy reliance on stubbing and mocking. The former refers to replacing a dependency with a constant or simplified value (e.g., a function retrieving the current time could always return 12:34), while the latter also focuses on tracking function calls made by the replaced function.

When employing unit testing, a unit testing framework is often used, e.g., JUnit [

11] or the Google Test framework [

12]. The role of such a framework is to provide support for writing and checking tests. This includes both software which will run the unit under test (UUT) as well as programming libraries enabling, e.g., different kinds of assertions, error handling, stubbing and mocking, etc. We will refer to such frameworks as

test execution frameworks, as their main purpose is to execute the UUT.

2.2. Formal Methods

Using formal methods to identify software faults is mature research area, with various approaches. One approach gaining more and more popularity in recent years is to apply model checking to find software faults via unit proofs or test harnesses [

7]. Each such component tries to verify a small piece of a software system (akin to unit testing). These approaches works by creating a context which correspond to a desired testing set-up, and then the execution of the unit under tests, followed by one or more assertions to establish the desired outcome, very much like an ordinary software test. However, instead of actually executing the code it is passed to a verification engine which analyses whether the assertions hold under all possible context (constrained by the set-up).

2.2.1. Bounded Model Checking

A technology for verifying assertions in code is

bounded model checking. Model checking means that a (mathematical) model of the program is constructed in such a way that a if an error (i.e., an assertion fails) exists in the original program, it will manifest in the model. Then verification algorithms can check the model and provide counter-examples (traces where an assertion fails) or confirm that the model is correct (and thus also the original program). It is common that the verification is done by trying to find an execution which makes the assertion false, and if no such execution exists, the assertion is guaranteed to hold. Thus the absence of a counter-example guarantees the correctness of the code. A tool which supports model checking of C code is CBMC [

13], which works by utilizing special statements CPROVERassume and CPROVERassert to constrain and check the state space.

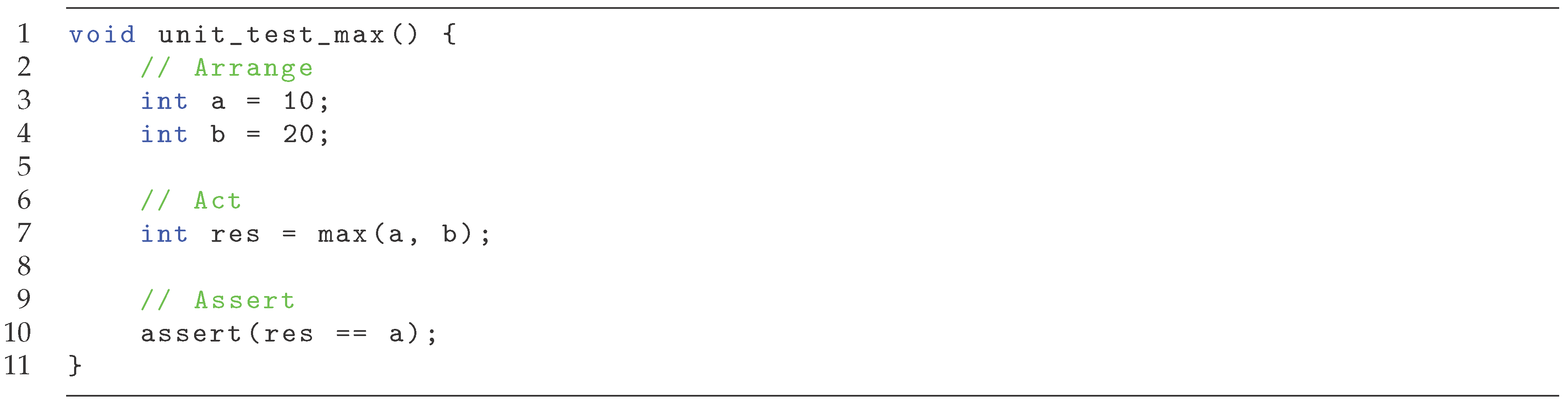

Example 2.

Consider the code in Figure 2 (for more realistic example see, e.g., [7]). It establish that a,b are unconstrained integers s.t. a >= b. At the end it asserts that res (the result of max(a, b)) should be equal to a (which is correct as a is the larger integer). Running CBMC on this code (assuming a correct implementation of max is referenced) will yield that no values of a and b can be found such that the assertion fails, and thus the functionality is verified.

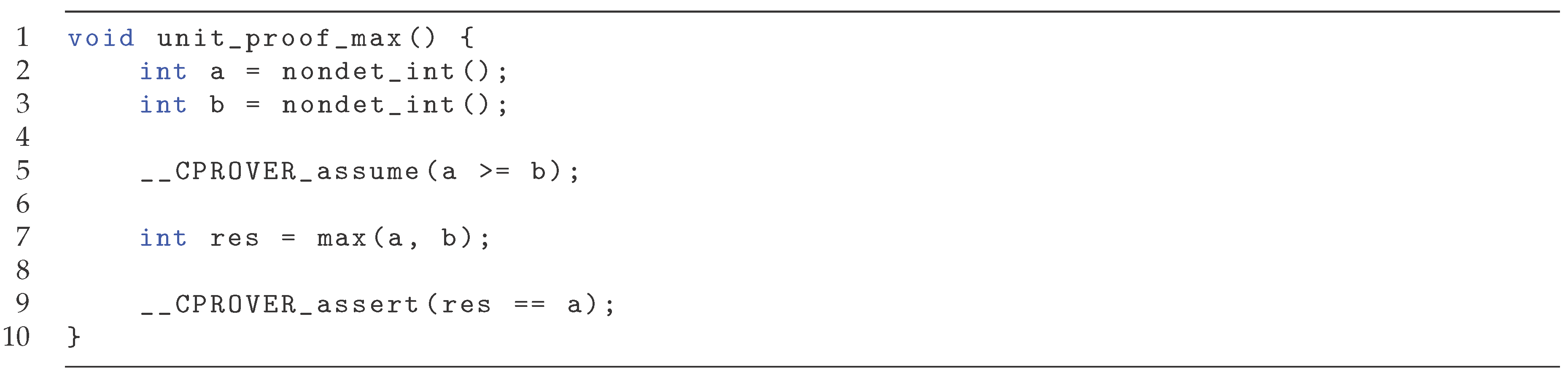

The bounded part of bounded model checking means that the model is made finite, to ensure model checking will terminate.

Loop unrolling is a common technique to turn a program with loops, which has an unbounded number of states, into a program without loops. In principle, loop unrolling takes a loop and converts it to an if-statement, and then copies it

x times. This leads to a program which is semantically equivalent to the original one, as long as the loop would not be taken more than

x times. To guarantee that the chosen

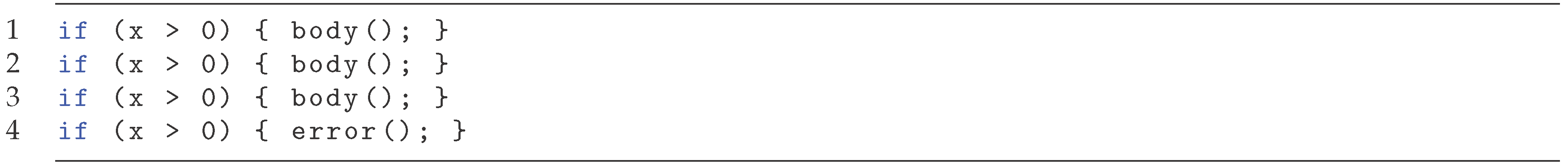

x is not too small, unwinding assertions can be added, i.e., after the last copy of the loop the condition is checked one more time, and if it holds an error is raised. Unwinding is illustrated in

Figure 3, with the original loop, and

Figure 4 with an unwinding of

and including an unwinding assertion.

3. Test Analysis

In this section we outline the formalization of our proposed approach named test analysis. The general idea is to analyse test (using formal tools) instead of executing them and observing the resulting state.

3.1. Traditional Testing

We begin with a formalization of traditional software testing, i.e., where assertions are checked by execution, to be able to relate it with the concept of test analysis. Given a a system-under-test (SUT) , and a test t, the purpose of test execution is to observe the final state after executing t on (for simplicity, we assume that the checking of a test outcome is done after the whole test finishes executing). Let be the variables of the SUT and be the variables of the test. then we define an (integer) state as follows:

Definition 1.

Astate, is a mapping . Let be the value of x in state s, and is the state identical to s except the value of x is assigned to c.

Thus, a particular state

s will assign one value to each variable in the SUT and the test. For this paper, we consider only integer states, i.e., mappings of variables to integer values. In principle it should also represent the contents of the registers, the value of the program counter and the memory on the stack/heap, as well as different types, e.g., strings. However, the general approach remains unmodified. To

test a system

, we use software tests

and consider them to consist of three phases (see Sec.

Section 2.1). We formalize the notion as follows:

Definition 2.

We define atestas a tuple , such that:

We say that a testpasses(orfails) in a state s if (or ⊥).

For simplicity we do not care about the tear-down phase, i.e., how to restore the system to the initial state to ensure isolation between tests. We call the process of evaluating the expression to check the test (where s should be some initial state).

Example 3.

Consider a test such that:

,

,

,

The function, the unit under test, is defined elsewhere. This test ensures that when is applied with 10 and 20, the result should be equal to 20.

In practice tests are not described as mathematical functions but in source code (e.g., in C). Given semantics for a programming language, there is a natural translation function from source code to mathematical functions which maps each phase to a function corresponding to its effect. We do not go into details about that here since it is beyond the scope of this paper, but assume the existence of the translation (in practice this is provided by a back-end). To ensure that source code would adhere to the format of arrange, act and assert in Definition 2, we restrict tests in source code to follow a strict template. We will here present the template in C, but it could be defined for a different language as well.

Definition 3.

A function in C is atestif it follows the following rules:

The restriction to the act, arrange, assert pattern is done intentionally as many tests do adhere to this pattern [

14]. The stronger restriction of a single assert is for simplicity, and can be easily changed (for example, assert(A) and assert(B) can be replaced by assert(A B) as long as the assert-phase is monolithic. The restriction on a single act is done to enable enrichments (see below) and adheres to the principle that a unit test should "test a single thing".

After creating one or more test cases (forming a test

suite), the next step is to evaluate each individual test passes or not. We denote this process

test evaluation. The process of

test evaluation refers to checking if a test

pass or

fail. If a test suite is evaluated, it passes if each individual test is evaluated to pass. Traditionally, test evaluation is performed by test execution. As an an alternative approach towards evaluating a test, instead of using a test execution function, we propose to use formal methods to establish this instead. Given a

, its state

s and test

t, we let

test analysis refer to the process of analysing the

and the test and decide whether executing and observing the assertions would indicate pass or fail. It is important to note that in test analysis, there are cases where termination is not guaranteed (due to the halting problem [

15]). Therefore, we must allow for an additional output

when dealing with test analysis. Using test analysis, the outlook is that from a users (i.e., testers) point of view the testing process looks a lot the same, with only the test evaluation part being replaced, see

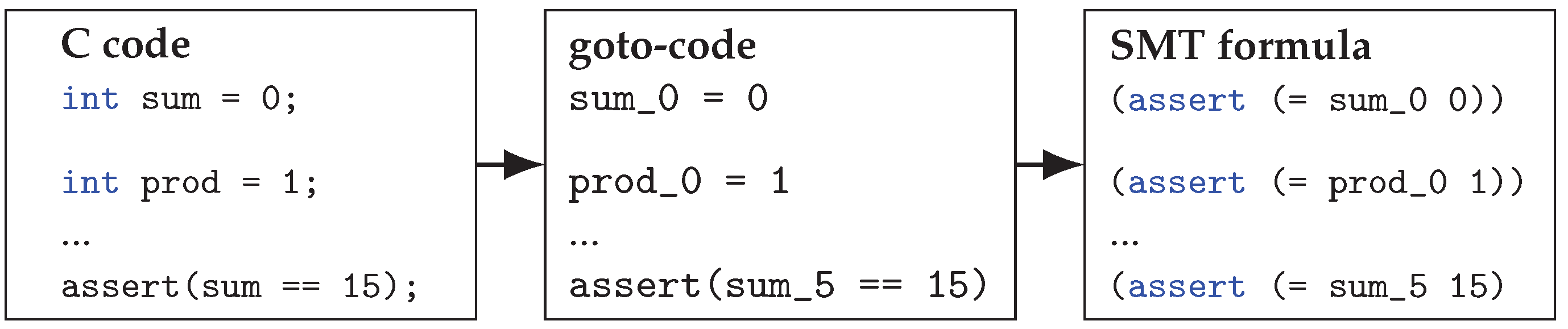

Figure 5. This requires an translation from the source code to a formal model, analysis of the model, and parsing of output back (e.g., if formal analysis finds a failing test, which test is it in source code). We do not go into detail here, but one can use, for example, CBMC [

13], which translation would look similar to

Figure 6.

3.2. Rich Tests

With the formalization of testing and definition of test analysis in place, we can now introduce the key concept of this paper. In this section, we introduce the notion of rich tests, which are enabled when we are using test analysis. The main difference between ordinary tests and rich tests are that the latter can handle abstract states.

Definition 4.

Anabstract state is a non-empty set of (concrete) states.

Intuitively, an abstract state represents a set of possible concrete states. A rich test is defined as an ordinary test, but the arrange phase yields an abstract state, and the the act phase maps abstract states to abstract states. The assert phase still considers concrete states:

Definition 5.

We define arich testas a tuple , such that:

yields the abstract state after arrangement.

yields the abstract state after act.

is true if a concrete state would pass the test.

We say that a testpasses(orfails) in a state if , or equivalently .

Since the arrange and act functions of a rich test returns an abstract state, a rich test works over sets of states and checks that the assert holds for all these states. Intuitively, the phases can be thought of the arrange phase setting up a set of possible arranged states. The act phase will return all possible reachable states from the set of arranged states. Finally, the assert phase checks if any one of the reachable states violates the assertion, and in the case return ⊥, otherwise ⊤.

Example 4.

Consider a rich test such that:

,

,

While the test in Example 3 defined the arrange phase to set x and y to constant values, in this rich test instead returns the abstract state containing all states where x is less or equal to y. The act phase merely sets to the result of in each concrete state, and the assert is identical (as it works over concrete and not abstract states). The test checks that if is applied with the result is always equal to y.

In a traditional execution environment, it would be very hard to evaluate a rich test, as a computer is (generally) only in a single state during execution. However, when translating to a formal model, it is possible to reason over a large amount of states in parallel. Of course, we would like to express rich tests as source code, and we describe again a template in C code (differences between this definition of ordinary tests are emphasized):

Definition 6.

A function in C is arich testif it follows the following rules:

The key difference between ordinary tests and rich tests is the use of non-deterministic assignments. A rich test allows for assignment to a non-deterministic value, i.e., a variable can be assigned a special value indicating that it can have a set of values. Assumptions in the arrange phase of a rich test can restrict possible states of non-deterministic variables. It can be used to In general, this set can be any possible collection of values, but to be more easy to reason about it is reasonable to use intervals or easy-to-understand properties, e.g., odd values. With these capabilities, it is possible for a rich test to arrange and act over abstract states, with an assert stating what the desired outcome of the test should be. Since a rich test works over abstract states, it is not only interesting to check for the precise state, but also properties of the state (e.g., the value should always be positive). In the next section a syntax for supporting these things is introduced.

4. rUnit—Rich Testing with CBMC

A rich test can not be compiled and executed, but is only possible to evaluate using test analysis. Analogously to test execution, we can create a

test analysis framework supporting automatic analysis of (rich) tests and present the outcomes. In our work, we use the state-of-the-art formal verification tool CBMC ([

13]) and rely on the correctness and soundness of it (which have been reviewed and tested in the scientific community). In this section, we present our implementation of test analysis and show how to translate the template introduced in the previous section, with some extra syntactic shortcuts, into C-code which can handle the semantics introduced test analysis section. Our framework is named

rUnit (rich unit testing framework) and is implemented in python working over C code. The test framework has been designed such that no annotations are required in the source code which is tested. For many formal verification approaches it is common that the source code itself is marked with invariants or pre- and post-conditions. We have carefully chosen to ensure that whether a test analysis framework or a test execution framework is applied should not be visible in the source code, but only in the test code.

4.1. Syntax

We begin by introducing the syntax of a test. It is a C function which returns void and accepts no parameters. It is prefaced by the BEGINTEST statement to mark the function as a rich test. A test can contain ordinary C code with the addition of the ASSUME, ACT and ASSERT statements as well as non-deterministic assignment. In general, all assumes will come before the (single) act, which is followed by a (single) assert. A test should be interpreted as follows. All code coming before the act is the arrange-phase of the test. Assignments may include assigning of (an underscore) signifying a non-deterministic assignment. ASSUME expr states that expr is assumed to hold from this line onwards, meaning that any non-deterministic variables are restricted to those fulfilling the expression. If no such assignments exists, the test is aborted (but not failing). The act line has no special semantics but is used to identify the line of the tests act phase. Finally, the ASSERT expr checks that the expression does indeed hold, and if it doesn’t, the test fails.

4.2. Back-End

The back-end of

rUnit is the C Bounded Model Checker (CBMC) [

13]. The strength of a bounded model checking is that it turns any verification problem into a finite one and is thus guaranteed to terminate (although it can take a very long time). Moreover, since it works by unrolling loops, there is no need to work with invariants or termination condition. The weakness is that it is incomplete, which will lead to cases where the test analysis of a rich test results in an unknown result. There is a possibility of using a different back-end, but is currently not in the scope of this project. The rich tests are converted to a syntax meaningful for the back-end. We present the translation for the different statements.

#ASSUME

The assumption of a condition exp is replaced by the CBMC command CPROVERassume(exp).

#ASSERT

The assertion of a condition exp is replaced by the CBMC command CPROVERassert(exp, "exp"), where the second argument is the string representation of the expression.

x =

Assignment by non-deterministic values are replaced by an assignment to a corresponding function defined by CBMC, e.g., int i = is replaced by int i = nondetint().

4.2.0.4. x = [l,b]

Interval assignment is replaced by a non-deterministic assignment followed by assumptions restricting the interval. For example, i = [0, 10] is replaced by i = nondetint(); ASSUME 0 <= i i <= 10.

Example 5.

Consider the source code in Figure 7. It is a rich test of the max function. Line 2 and 3 has non-deterministic assignment to variables x and y, while line 5 uses an assumption to restrict the values to obey the inequality x <= y. The assertion states that the returned value should be equal to y, which is correct as it will be the larger of the two variables.

4.3. Analysing Rich Tests

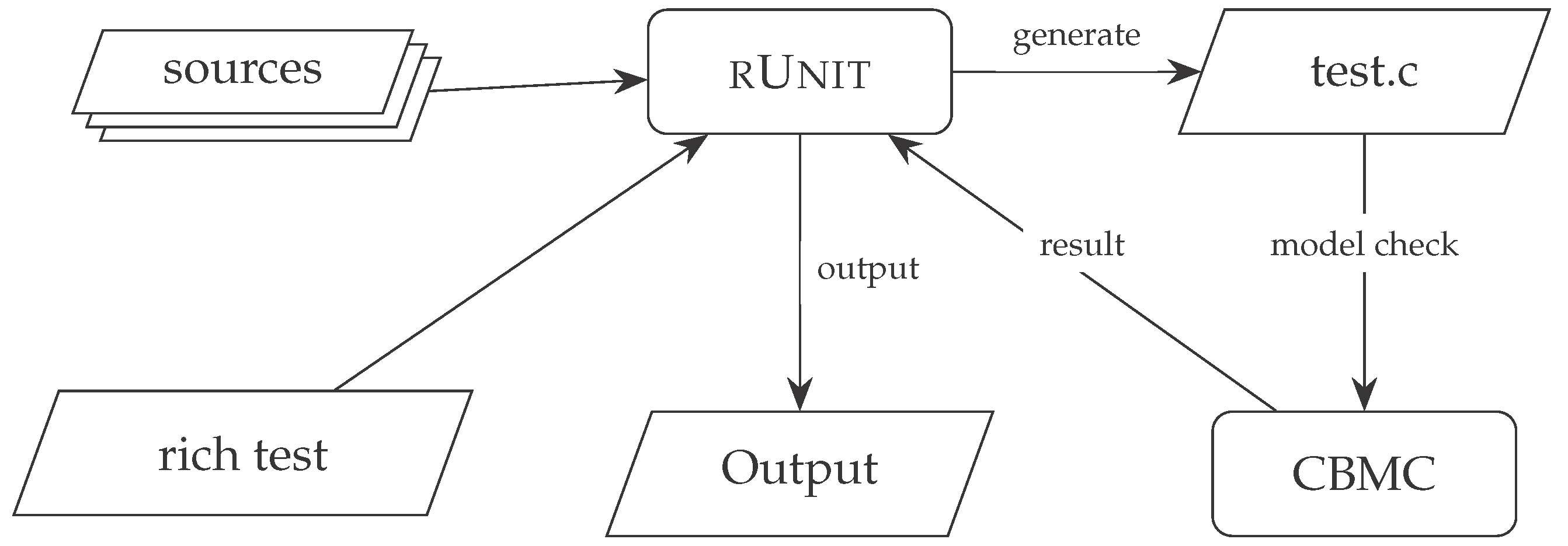

The frameworks workflow is outlined in

Figure 8.

rUnit is fed a set of sources and a rich test and uses them to generate a file

test.c which contains the rich test converted to a format supported by CBMC. Next, the

test.c is model checked by CBMC and the result is fed back to

rUnit. This in turn parses the output from CBMC and presents the relevant information to the user (multiple loops can occur for the same test if counter-examples are required). When running the framework to analyse rich tests, one factor which can greatly affect performance is the choice of how many unwindings should be done (see

Section 2.2.1). It is set to a default value of 3 which is only sufficient for small examples. If a too small value is set, the user will be notified that the amount of unwindings is too small and can manually increase the value.

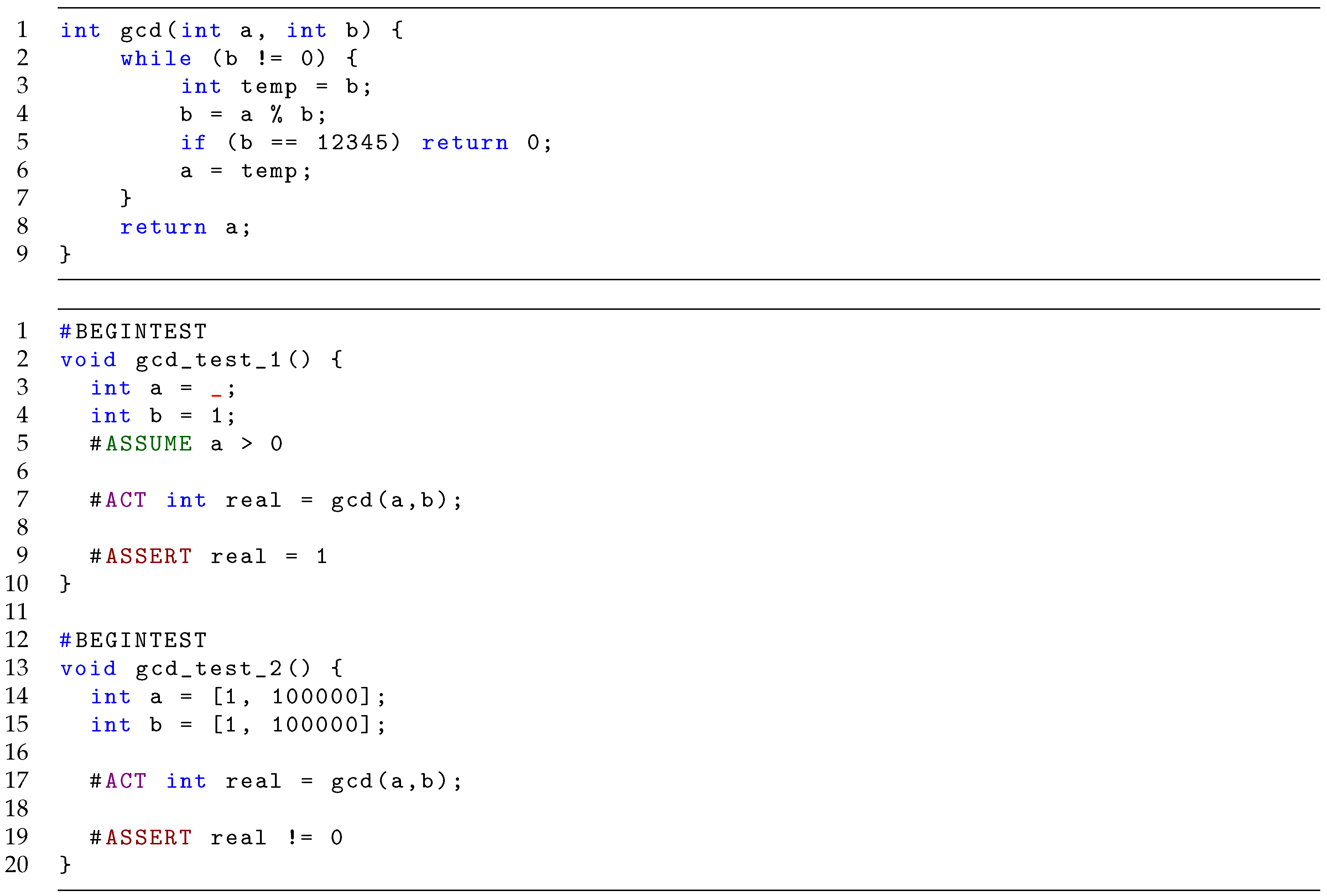

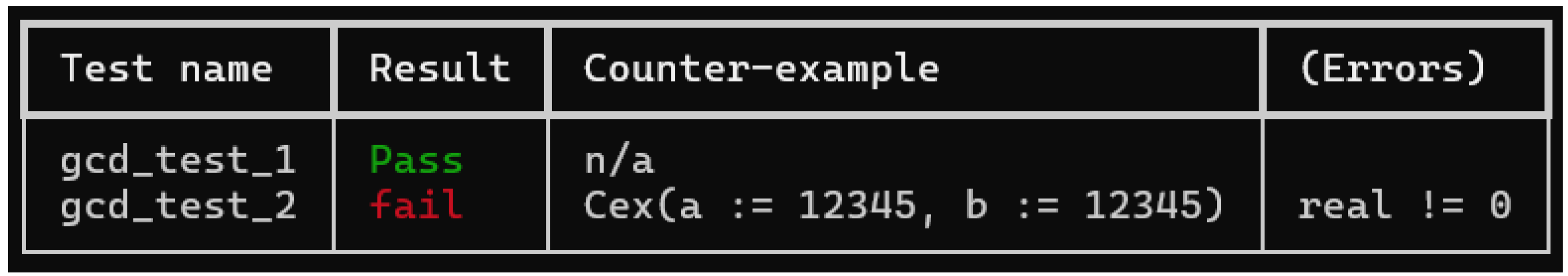

Example 6.

Consider Figure 9. The top of the figure contains the source code of a faulty implementation to compute the greatest common denominator (the fault in this case is a constructed bug when b is equal to 12345). The bottom contains two rich tests testing the function gcd. An ordinary unit test would test gcd for two particular values of a and b. In contrast, a rich test can allow a set of values to be tested. The first test checks that if argument is any positive value, and the second argument is one, then the GCD should be one. The second test does not check that the computed value is the GCD of the two arguments, but it checks a property of the result. In this particular case, we check that if the two arguments are in the interval the output should be greater than zero. This test will discover the introduced bug and provide a counter-example (i.e., values for a and b) which yields a return value failing the assertion. The output is shown in Figure 10.

In the following sections we present two enrichments to the framework which extends the capabilities in various directions.

5. Enrichment 1: Property-Based Stubbing

In this section we discuss how the template presented above can be utilized to extract specifications of tests, and how to translate these into a (smart) stubbing table, enabling the automatic extraction of mocks from rich tests. We show how to use these (smart) stubs in our introduced framework. A testing stub is a piece of code intended to replace real code to isolate a test case from its surrounding environment. A stub can be at various levels of complexity, but usually it is as simple possible, e.g., returning a constant value. While in traditional testing a stub must return a concrete value when executed, when using test analysis this restriction does not apply. We can leverage this by allowing a stub to specify a property of the return value instead of specifying a concrete value. We will call such stubs property-based stubs. It is similar to property-based testing, but properties are not only specified for inputs, but also for outputs. We illustrate with an example.

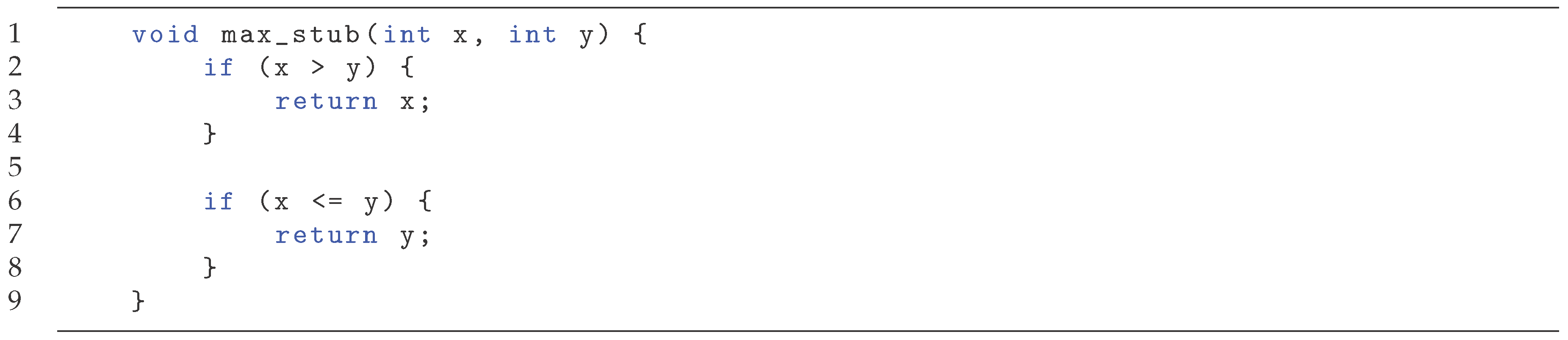

Example 7.

Consider the max function. A stub could for example always return a constant value of 42, or the value of the first argument. This would be easy to automatically generate. Using a property-based stub, we could instead have two cases: if the first argument is greater than the second, return the first argument; if the second argument is greater or equal to the first, return the second argument.

In the example of max it happens to be that the two cases covers the entire input space. Since this is not always the case, it can be useful have a catch-all with the input property of true, and a constant return value to handle unspecified cases. The core component of property-based stubbing is the stub table:

Definition 7.

Astub tableis a table with each row consisting of aninput propertyand anoutput property.

Each row of the stub table corresponds to a case, interpreted as if the input property holds, the output property will hold after executing the stubbed function. In this way, it is possible to specify different properties which can be utilized when stubbing the function.

Example 8.

Consider the property-based stub in Example 7. It could be summarized in a stub table:

| Input Property |

Output Property |

|

|

|

|

where corresponds to the value of the returned value.

A stub is often implemented as a function in traditional testing, which returns a constant value, or a return value based on some simple computation. A property-based stub could be implemented by a sequence of if-statements, matching the input property, and then returning a value satisfying the output property.

Example 9.

Consider the stub table from Example 8. It could be implemented with two if-statements as shown in Figure 11. In this particular scenario, the stub replicates the functionality of the original function, but in general this is note the case.

When a stub has been created, all function calls to the original function are replaced by calls to the stub (or the original function is replaced by the stub), ensuring that the test is not dependent on the original implementation.

Example 10.

Consider the function maxinlist shown in Figure 12, which returns the maximum element of a list (implemented as an array). It works by calling max repeatedly, keeping the result for the next iteration. The row r = max(a,b) could be replaced by a property-based stud (i.e., r = maxstub(a, b) and the functionality would remain the same.

5.1. Automatic Stubs

Since we require rich tests to be written in accordance to a strict template, we can extract information from them. Assuming they are correct, one can consider a rich test as a

partial specification of a unit: we take what is before the ACT-section as a

pre-condition , whatever comes after the

post-condition, and the ACT-section itself as an operation

. With this in mind, if we assume a test is correctly written we can automatically extract a rule:

This means that for all states which satisfies the pre-condition, the post-condition will satisfy the states reachable by applying the operation. Note that the states satisfying the post-condition is an over-approximation of the actually reachable states – the condition expresses something which holds for all reachable states, not that all states satisfying the condition is reachable. For our purpose of automatic stubbing, this over-approximation can be problematic in the sense that we might not be able to find a proof when there is one, but it will not cause unsoundness.

Example 11.

Consider the rich test in Figure 7. It can be seen as a specification with and . The operation is .

Note the relation between a stubbing table and an extracted rule from a specification. The pre-condition is the same as the input property and the post-condition is the output property, and we create one stubbing table for each operation. We will treat the rows of a stubbing table and the specifications they are obtained from interchangeably. We can automate the process of creating a property-based stub. The idea is that whenever an operation for which we have a stubbing table is encountered, if the pre-condition can be known to hold, the operation can be replaced with the post-condition. In regular testing we would have to select a single rule to apply, but when dealing with test analysis we can allow multiple rules to be active at the same time. We utilize a construction which we denote stubbing choice:

Definition 8.

Given a set of specifications , astubbing choiceis constructed by the following components:

For each specification we introduce achoice variable indicating whether the pre-condition is met or not.

-

We introduce a covering assertion which ensures that at least one of the specifications apply, by asserting the disjunction of the pre-conditions>

ASSERT Pre(s1) || ... || Pre(sn)

-

For each specification we introduce apre-condition choiceof the following form

ASSUME (si == 0 || Pre(si)) (si != 0 || !Pre(si))

-

For each specification we introduce apost-condition assumptionof the following form

ASSUME si == 0 || Post(si)

Finally, an assignment of the form target = op(s) can be replaced by a stubbing choice through the following steps:

- (1)

The target line is removed and replaced by a non-deterministic assignment to target.

- (2)

Before the target line, each is declared (but with no value).

- (3)

Before the target line, after declaration of , each pre-condition choice is introduced.

- (4)

After the target line, the post-condition assumptions are introduced.

Intuitively, a stubbing choice allows the search to select one (or more) pre-conditions to hold, and then requiring the corresponding post-condition to be assumed. The non-deterministic assignment to the target variable allows for post-conditions to hold. We illustrate with an example.

Example 12.

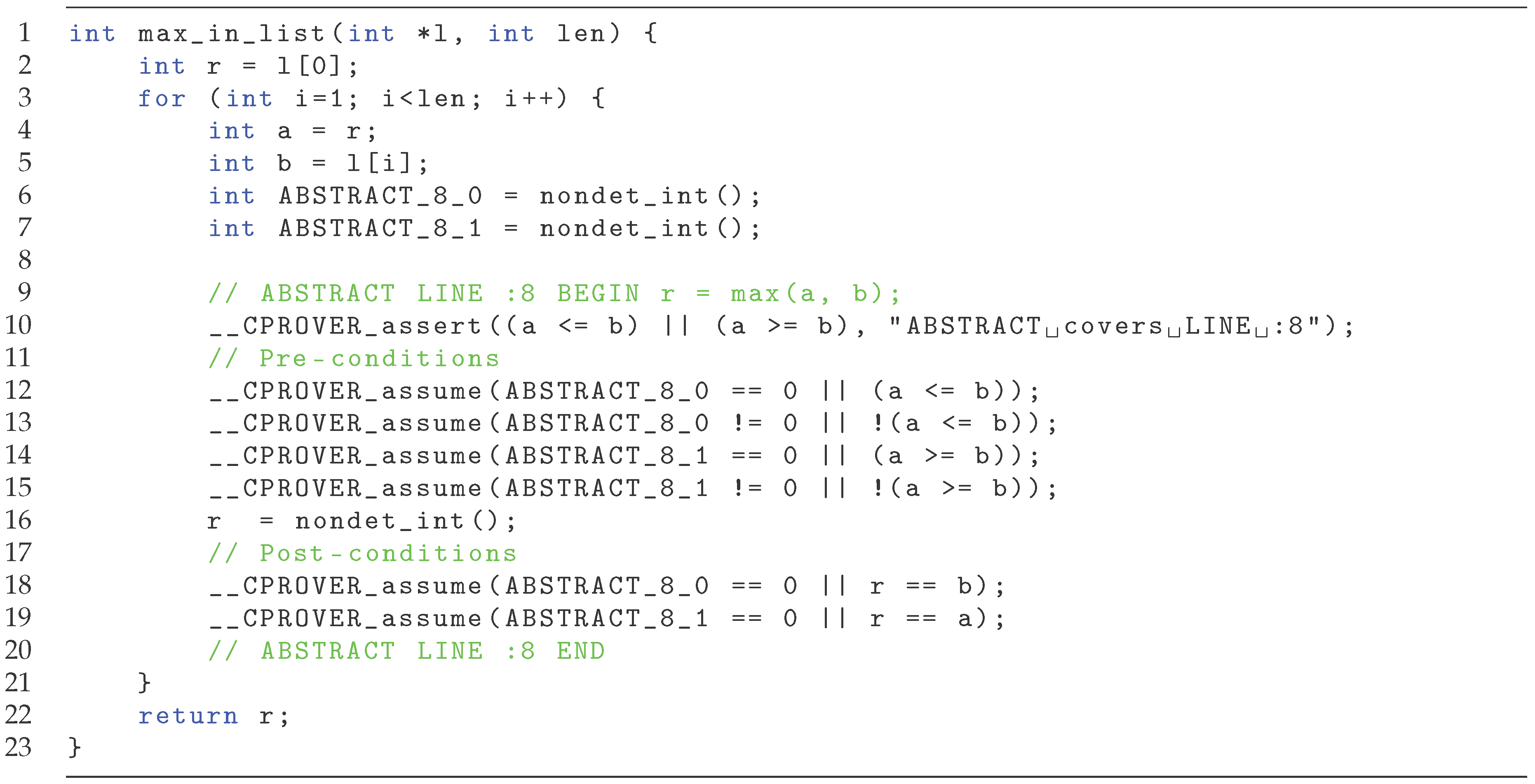

Once again we consider the function maxinlist shown in Figure 12. We present in Figure 13 the automatically stubbed version obtain from runningrUnit. On lines 6-7 the choice variables are introduced, and on line 10 it is checked that at least one of the cases always applies. On lines 12-15 the two cases are enforced, i.e., ABSTRACT80 is set to zero if and only if a is not less or equal to b (and respectively for ABSTRACT81). Line 16 sets r (which is from the original program) to a non-deterministic value such that it is unconstrained. Finally, lines 18 and 19 ensures the post-conditions, i.e., if ABSTRACT80 is set to non-zero (first case applies), then the r is equal to b (and respectively for ABSTRACT81). This modified code can be used in test analysis without relying on a specific implementation of max.

6. Enrichment 2: Non-Deterministic Strings

As shown above, rich tests has the capability of handling non-deterministic values of integer variables, constrained them using interval boundaries or assumption constraints. Extending this support to variables of other types poses different challenges. To the best of the authors knowledge, there is no support for specifying string constraints (i.e., char arrays in C) using regular expressions. In this section, we show how we can extend the framework to support non-deterministic assignment of string, by utilizing generated implementations of NFA (non-deterministic finite automatons).

6.1. (Simple) Regular Expressions

We begin by describing the regular expressions currently supported by our framework. For simplicity, we only allow recognition of string consisting of regular characters and three special symbols: ., \w and *. The dot (.) is, as usual the representation of any symbol, \w is an alphanumeric character, and the star (*) allows for zero or more repetition of the previous symbol. Since we do not have parenthesis, star only follows one specific character.

Table 1 has a list of example regular expressions. Next we provide a formal definition of a NFA to aid in our presentation of an automatic translation to C code.

Definition 9.

Anon-deterministic finite automaton(NFA) is defined as a tuple , where

is a set of states,

Σ is the input alphabet,

is the transition function,

is the initial state,

and is the set of accepting states.

We define recognition of words and languages as usual. Moreover, given a regular expression, it is straightforward to construct a NFA recognizing it. For more details see a standard text, e.g., [

16]. It should be noted that from our restricted form of regular expressions, all states in a constructed NFA will have zero, one or two outgoing edges. If it is the final state, it will have zero outgoing edges. If it is a symbol not followed by a star, it will have one outgoing edge marked with the symbol. If it is a symbol followed by a star, it will have one self-loop and one outgoing edge, both marked with the symbol.

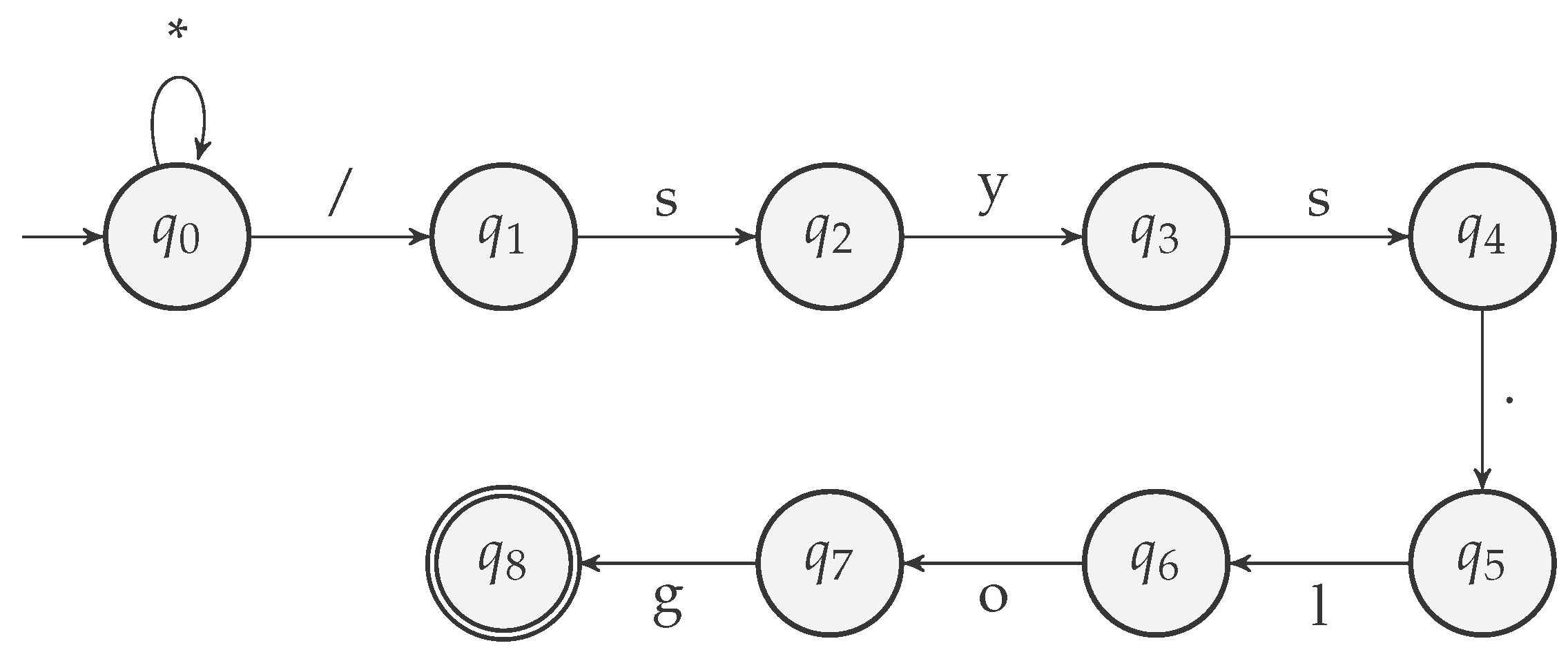

Example 13.

A NFA for recognizing the regular expression .*.sys.log is shown in Figure 14.

The next step is to create C code which implements the NFA. One approach is to utilize a generic algorithm, which takes a regular expression and a target string as inputs and checks if the target string belongs to the langauge of the regular expression. However, since the C code will be anaylzed rather than executed, it is desriable to keep it as simple as possible. Therefore, we propose for a given regular expression, to generate an implementation which recognizes only the language of the expression and no others. This trade-off means that for every regular expression in the code, we need to generate a new set of matching functions. We begin next to describe how the code is generated. Given a NFA

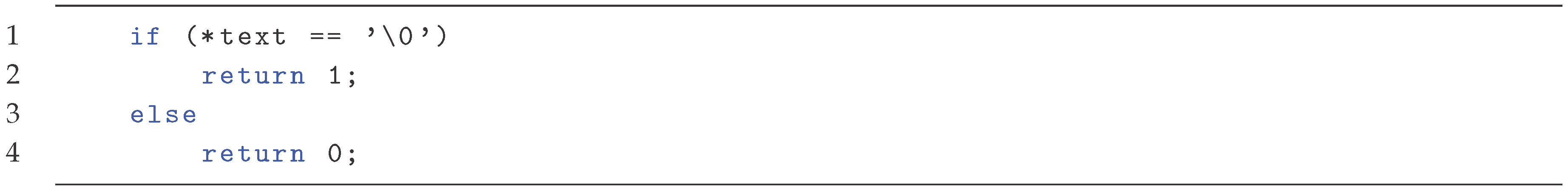

, we introduce for each state

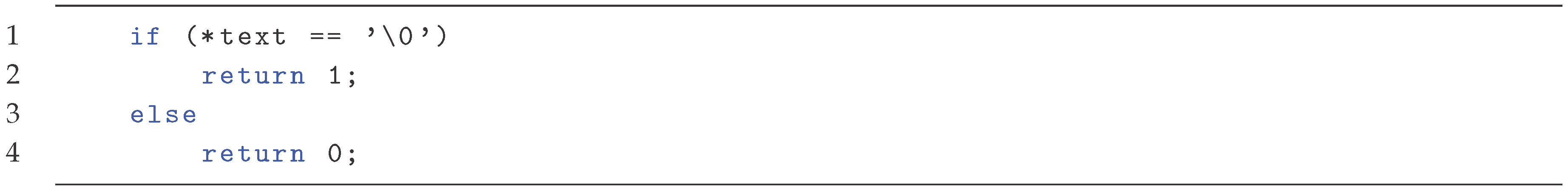

a function stateq.The body of the function is defined for the three cases of zero, one, or two outgoing edges. We begin in the case of zero outgoing edges:

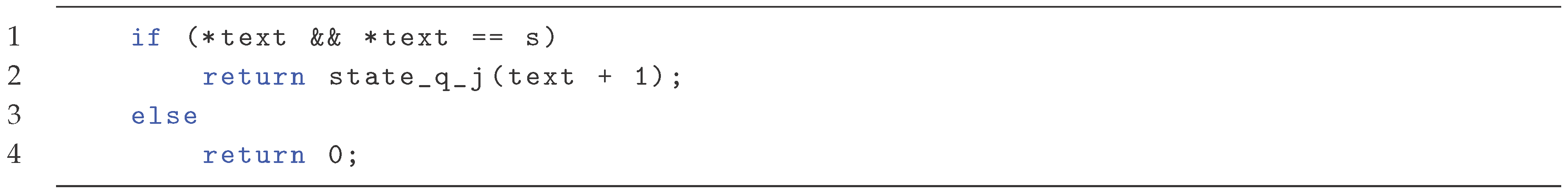

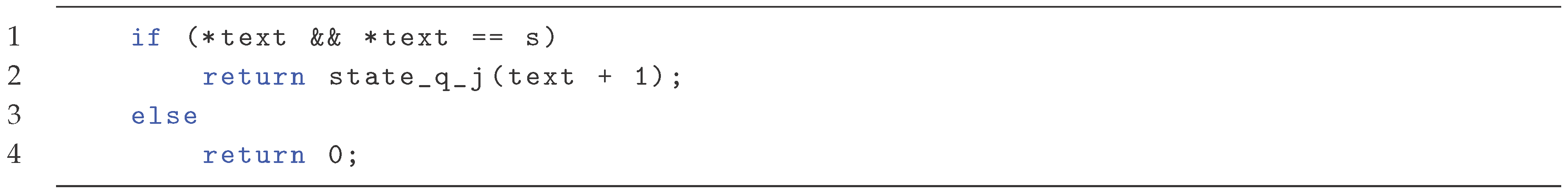

In this case, we just want to ensure that the end of the string has been reached. Next, we consider one outgoing edge to state

with label

s:

The first line checks that the next symbol of the string is indeed

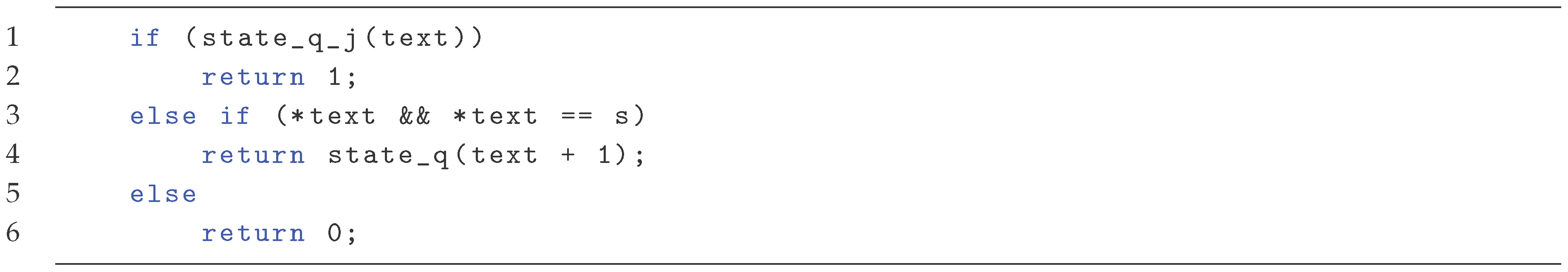

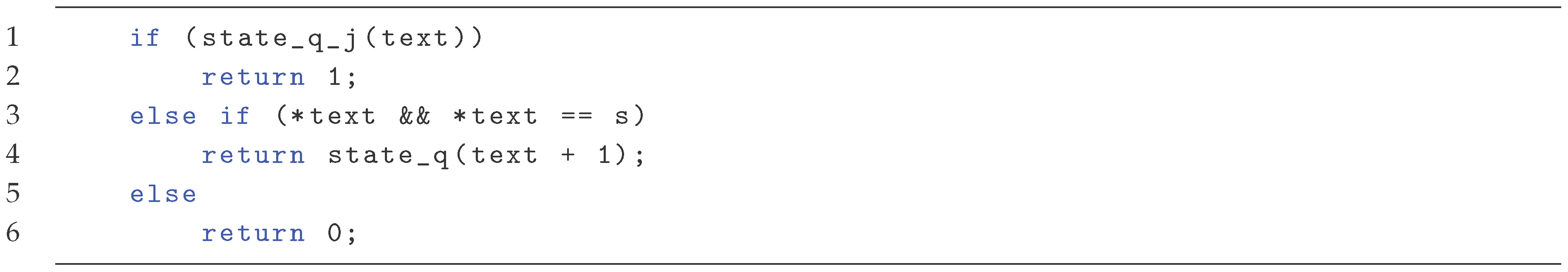

s. If the symbol to check is . the condition is changed to if (*text) and if the symbol is \w it is changed to if (*text ((*text >= ’a’ *text <= ’z’) || (*text >= ’A’ *text <= ’Z’) || (*text >= ’0’ *text <= ’9’)) ensuring the character is alphanumeric. If the if-statement is true, the function for the next state is called with the argument moved forward one step. If it is the false symbol, the function ends with a zero as there is no potential match from this point. Finally, we consider the case of two outgoing edges:

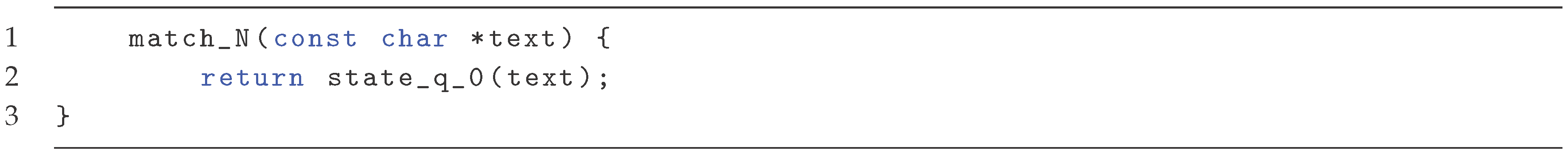

The first case corresponds to ignoring the star symbol completely and proceeding to the next state (observe text is not advanced); second case is to consume one symbol and then repeat the current state (stateq, i.e., the same state function is called). Finally if we are at the end of the string we must return zero. Thus given an NFA

N we can introduce the functions stateqi for each

, and create a final function which returns one if the provided string is accepted by

N and one otherwise:

Given the above construction, we can utilize it to replace a regular expression with corresponding NFA N with a call to the function matchN in an appropiate manner. We implement this in our framework in variable assignments with the following syntax:

REGEX target length regex

This means that variable target should be non-deterministically assigned every null-terminated string up to length length which is generated by regex. The requirement of length stems from that we need to know the size of the target character array to ensure null-termination at the end of it.

Example 14.

Consider the following statement: REGEX url 30 https://.* It states that url should be all strings up to length 30 beginning with "https://" and followed by an arbitrary suffix.

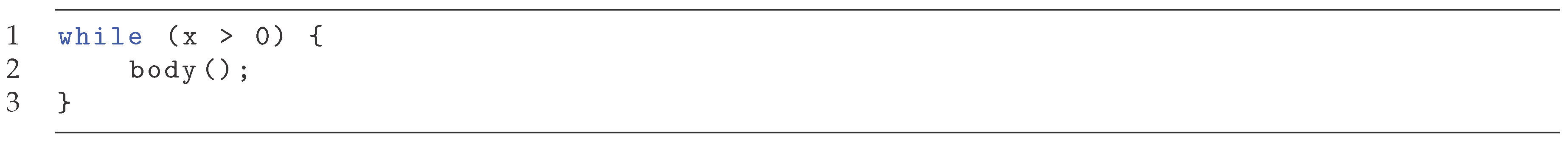

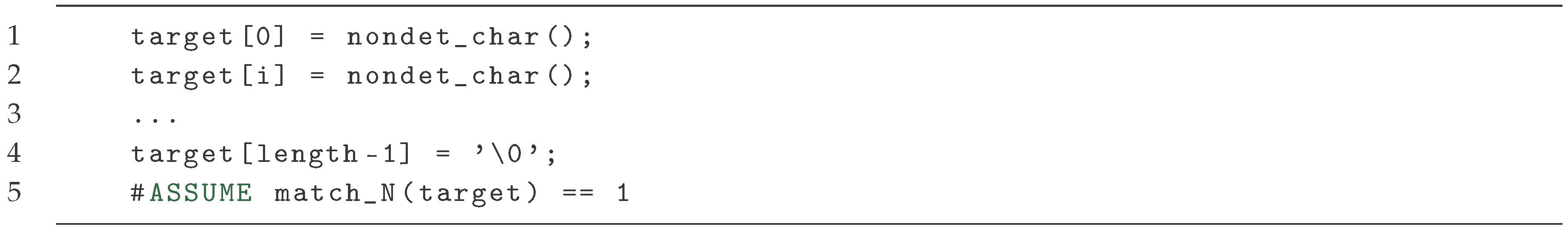

To enable an analysis of a rich test containing a regular expression, we replace the REGEX-statement with the following:

The first assignments to target, non-deterministically assigns characters to the whole string (up to length length). The final assignment ensures the string is null-terminated (a future extension could allow regular expressions to also express non-terminated strings). Finally, we have an ASSUME statement ensuring that target is indeed of the form of the regular expression.

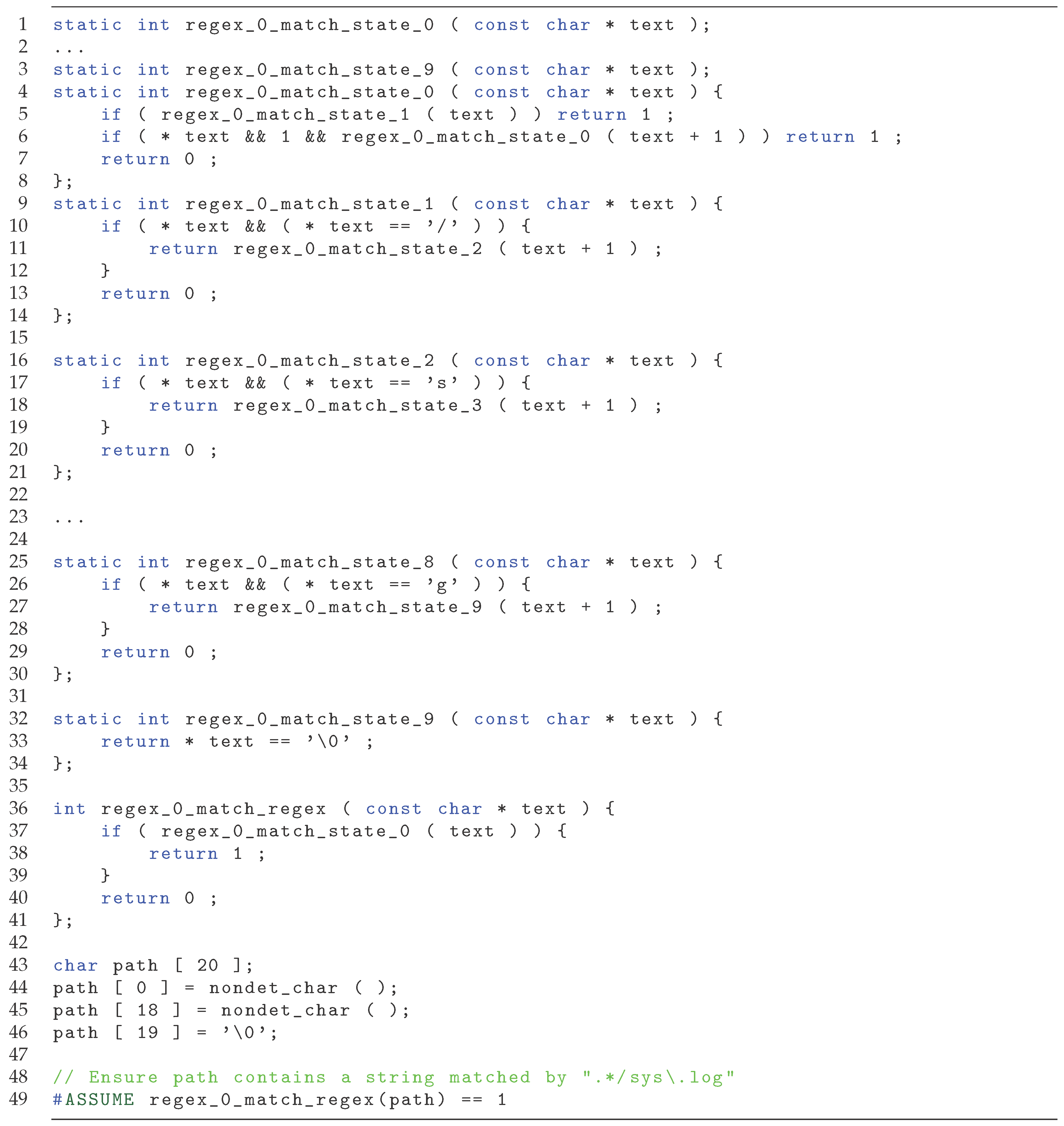

Example 15.

Consider the regex statement REGEX name 7 .*/sysŀog , it will be transformed into code as shown in Figure 15. The ASSUME on line 56 ensures that afterwards the variable path contains a string which adheres to the regular expression.

7. Related Work

The idea of

unit proofing, i.e., replacing unit testing with formal verification of units is now new, and have been applied, e.g., in avionics [

17,

18], in model checking boot code [

19], verification of the Linux kernel [

8], as well as an general approach [

7,

20]. The efficacy of unit proofing is being investigated by Amusuo et. al [

21,

22]. Through investigating real code with earlier vulnerabilities, the authors find that a structured approach towards writing unit proofs are cost-effective. In their work, the authors uses CBMC as their model checking tool and follow the guidelines from CBMC to develop the unit proofs. In our work, we introduce a middle-layer to enable the use of different syntax and more importantly to introduce new capabilities, such as string handling and automatic stubbing. However, we see no reason to expect the usability of rich tests to diminish due to a change of syntax.

Gunter et. al. has presented an approach for using model checking to verify units of code [

20]. They allow the user to specify properties in Linear Temporal Logic (LTL). While

rUnit works at the C-code level using test cases which are syntactically very similar to traditional tests, Gunter et. al. provides a graphical tool that visualises execution paths in the program, where the user can specify LTL formulas or select nodes to indicate the target of the search. Similar to our work, they also consider how to handle missing code using specifications instead of the original code. In contrast to our solution, they do not consider how to derive these specifications automatically.

A report on a successful use of model checking is from Cook et. al. presenting the approach applied to boot code from data centres [

19]. The authors describe in detail the challenges on handling boot code and their specific issues. The work is not concerned with testing in general, but solving this problem in particular and thus only have one test harness (i.e., test case). Their work demonstrates that the approach is scalable and applicable to industrial cases, but is not concerned with how to make it more accessible to non-expert users.

The concept of a parameterized unit test (PUT) is closely related, allowing a test to contain abstract variables [

23]. Thus a test can specify a certain behvaiour independent of the exact initial state (e.g., the number of elements in a list). Tillmann et. al. also introduces the idea of using tests as specification to leverage the symbolic execution which is performed during the analysis of a PUT. However, the goal of this process is not to establish the correctness of the property, but to generate test cases which triggers all relevant behaviours, which can then be executed and checked. In

rUnit, we wish to leverage the specifications to help assist in the verification of the unit behaviour directly, where there is no execution of the target code at all.

8. Examples

In this section we present some examples to demonstrate the capabilities of the framework. All examples in this section executes in a few seconds on a regular laptop.

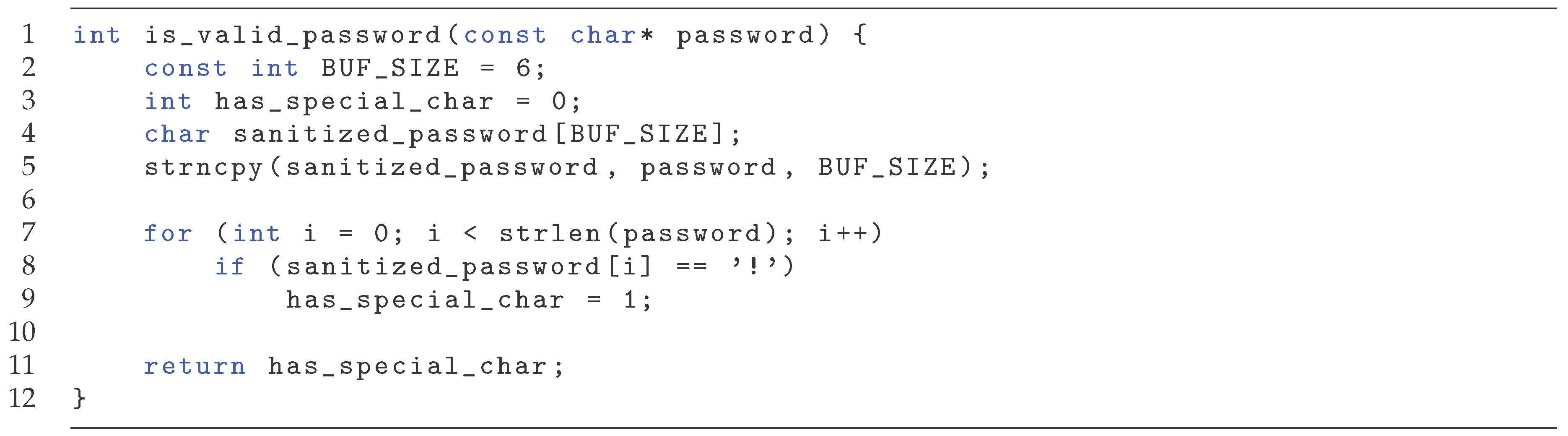

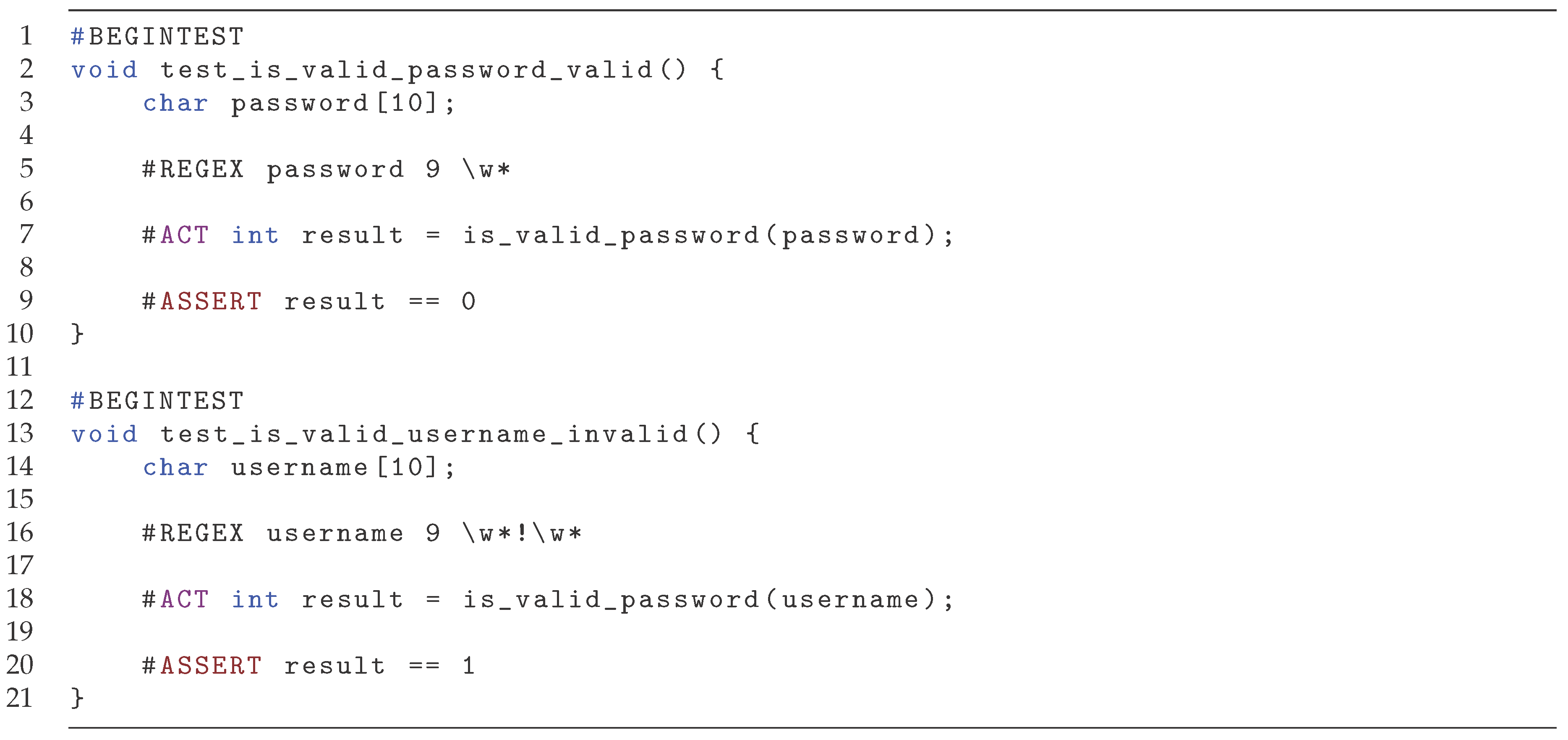

8.1. Valid Username

Consider the simple function isvalidusername in

Figure 16 which recognizes that a valid password must contain at least one special character, here simplified as in containing an exclamation mark (!). It uses a buffer where it copies the password before checking it. There is a software bug on line 1, where BUFSIZE is set to 6, instead of the length of password. To test such a function, we wish to check the two cases, a valid password, and an invalid. To check the invalid case, we provide a regex which contains only alphanumeric characters, shown in the top half of

Figure 17, and the valid case is checked by a password containing a single exclamation mark, shown in the bottom half of

Figure 17.

Both error fails, and inspection on the result shows that in the former case, if the provded password is longer than six characters, there might be an exclamation mark after sanitizedpassword erroneously making the password valid. The second case fails if the exclamation mark is placed after the first six characters, and the memory after sanitizedpassword does not contain one, then the password is incorrectly marked as invalid. The bug in the first case would have been identified by any invalid string longer than six characters, while in the second case it requires a string where the exclamation mark is placed after the sixth position. With the use of regular expressions, the user does not need to specify specific strings but a general format, increasing the odds that these conditions are fulfilled. For example, if inputs has been chosen as "abcdef" and "!!!password" for the invalid and valid case respectively, the tests would have not found the bug.

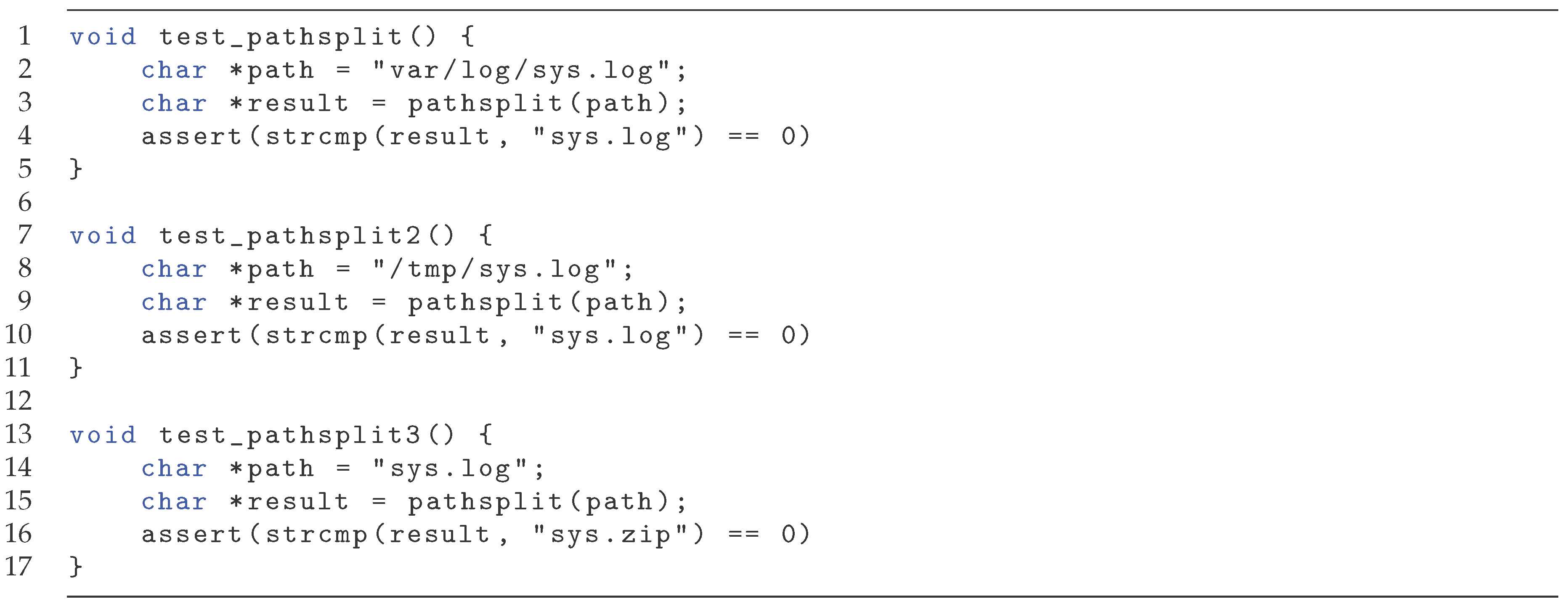

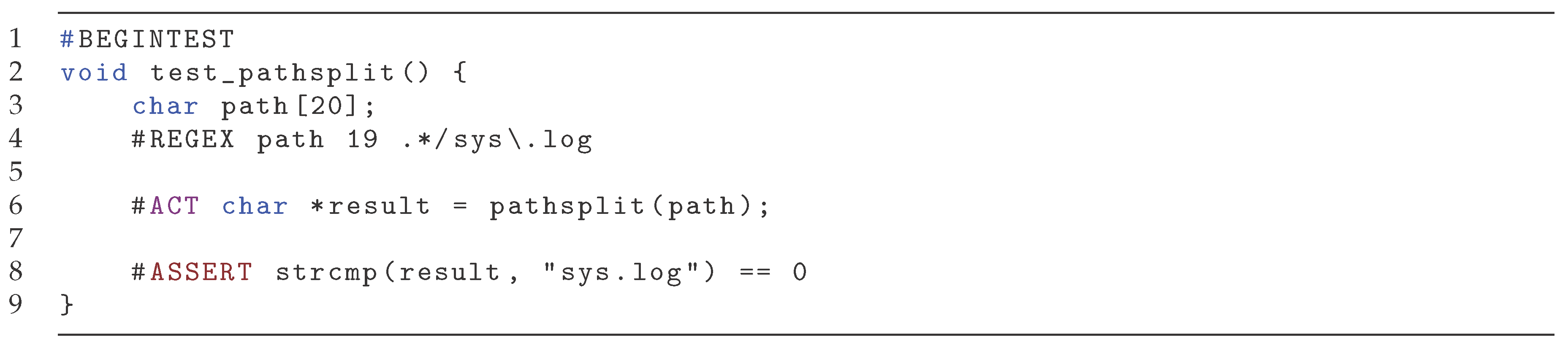

8.2. Identifying Filename

The next example concerns extracting the filename from a path. The function under test is pathsplit, accepting a file path and returns the name of the file referenced. We do not show the function but in

Figure 18, we show what three ordinary test cases might look like to unit test pathsplit. Note that the three cases corresponds to the file being located in a absolute file path, relative file path and directly referenced. If we instead apply a rich test, we can formulate a single test which can cover all these three cases (and more) in a single test, shown in

Figure 19. This demonstrates how a rich test can succinctly represent many ordinary test cases with the use of regular expressions.

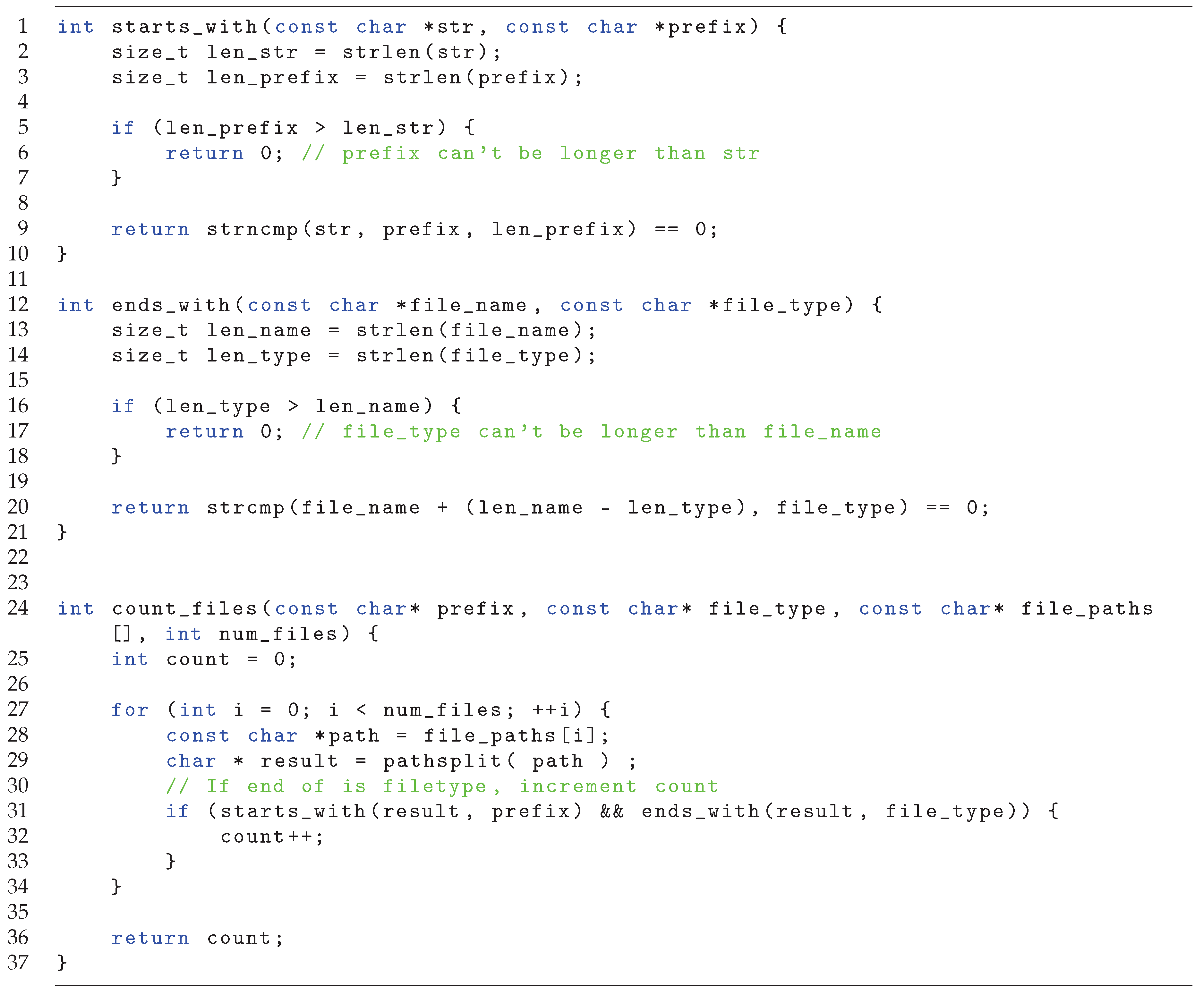

8.3. Count Files

Our final example demonstrates how property-based stubs can be used in conjuncation with regular expressions. Consider the source code in

Figure 20. It contains a function countfiles, which accepts a list of paths and counts the number of files which starts with the given prefix and ends with the given suffix. To extract the file name it calls the function from the previous example pathsplit. To test the function we use the rich test shown in

Figure 21. Note, that since all file paths in the test refers to a file sys.log, the call to the function pathsplit will be covered by the rich test case in

Figure 19. Thus we can enable automatic property-based stubbing, and achieve isolated testing of the countfiles function without having to construct a stub manually. To allow for a greater variety in the file paths one would need to create more test cases for the pathsplit function. This example demonstrates how the property-based stubbing can be enabled by existing rich test cases.

9. Conclusions

In this paper we have formalized the concept of traditional testing and, our proposed approach, test analysis to compare the two. We introduce the concept of rich tests and provide both a semantic and syntactic interpretation. Furthermore, we present our simple prototype rUnit which can perform test analysis on C code. We present two enrichments. First, we introduce property-based stubbing and show how it can be (partially) automated within rUnit and rich tests. Secondly, we extend rUnit with support for simple regular expression assignment to C string variables. Finally we demonstrate with a few examples how the prorotype works in practice. The research question posed in the beginning of this paper was:

How can formal methods be leveraged for unit testing in a manner which is clearly defined and more accessible to non-experts?

In this paper we have shown how (bounded) model checking can be applied for test analysis, clearly relating it to ordinary testing, with an added middle layer to allow for simpler syntax through enrichments. Property-based stubbing can assist in automatically generating stubs based on tests to achieve isolation of units without excessive manual work. The plan is to extend the framework in various directions and investigate how it can be designed to achieve more accessibility.

9.1. Future Work

The next step in this work is to apply the framework to larger code bases and to develop the framework to become even more user friendly. For example, the amount on unwindings is currently set test-wise, while it could be useful to unwind specific loops further. However, how this can be achieved in a simple manner has not been looked into. It is also interesting to perform a qualitative evaluation of the usability of the framework.

Furthermore, it is interesting to consider more possible enrichments enabled by the rich tests. Two directions which we are investigating are the testing of non-functional constraints and proof-based coverage. The first direction is verification of non-functional constraints (e.g., memory consumption) of a rich test. One direction is to use an approach such as COSTA [

24] where resource usage is pessimistically calculated and provided to the user. The challenge lies in finding a good and general method, as well as integrating it into the rich testing syntax and test analysis framework to ensure it is intuitive and easy to use. The second direction is proof based coverage, a method of measuring how coverage between a rich test and a ordinary test relates to each other. With the presence of non-deterministic values, one analysis of a rich test can correspond to multiple paths in the tested code. Since an ordinary test can only cover one path, it is interesting to investigate how these notions relate to each other and if there is a meaningful comparison in coverage (e.g., line coverage) and what software faults they can identify.

References

- Kassab, M.; DeFranco, J.F.; Laplante, P.A. Software testing: The state of the practice. IEEE Software 2017, 34, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasurinen, J.; Taipale, O.; Smolander, K. Software test automation in practice: empirical observations. Advances in Software Engineering 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorikov, V. Unit testing : principles, practices, and patterns, 1st edition ed.; Manning: Shelter Island, New York, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, E.W. The Humble Programmer. In Proceedings of the Communications of the ACM. ACM, Vol. 15; 1972; pp. 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of the Art in Software Verification and Witness Validation: SV-COMP 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 299–329. ISSN 0302-9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Clark, M.; Cofer, D.; Fifarek, A.; Hinchman, J.; Hoffman, J.; Hulbert, B.; Miller, S.P.; Wagner, L. Study on the Barriers to the Industrial Adoption of Formal Methods. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods for Industrial Critical Systems; Pecheur, C.; Dierkes, M., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg; 2013; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, N.; Cook, B.; Kallas, K.; Khazem, K.; Monteiro, F.R.; Schwartz-Narbonne, D.; Tasiran, S.; Tautschnig, M.; Tuttle, M.R. Code-Level Model Checking in the Software Development Workflow. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, New York, NY, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, I.S.; Mandrykin, M.U.; Mutilin, V.S.; Novikov, E.M.; Petrenko, A.K.; Khoroshilov, A.V. Configurable toolset for static verification of operating systems kernel modules. Programming and Computer Software 2015, 41, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, P.; Offutt, J. Introduction to Software Testing.; Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Appel, F. Testing with JUnit : master high-quality software development driven by unit tests; Packt Publishing, 2015.

- Salunke, S. Junit with examples, 1st ed.; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Google Test. https://github.com/google/googletest, 2025. Version 1.17.0, Accessed on 2025-04-30.

- Clarke, E.; Kroening, D.; Lerda, F. A Tool for Checking ANSI-C Programs. In Proceedings of the Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems (TACAS 2004); Jensen, K.; Podelski, A., Eds. Springer, Vol. 2988, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; 2004; pp. 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Xiao, L.; Yu, T.; Wong, S.; Clune, A. How Do Developers Structure Unit Test Cases? An Empirical Analysis of the AAA Pattern in Open Source Projects. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2025, 51, 1007–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the {E}ntscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1936, 2, 230–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hopcroft, J.E.; Motwani, R.; Ullman, J.D. Introduction to automata theory, languages, and computation. Acm Sigact News 2001, 32, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, Y.; Ledinot, E.; Delseny, H.; Wiels, V.; Monate, B. Testing or Formal Verification: DO-178C Alternatives and Industrial Experience. IEEE Software 2013, 30, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souyris, J.; Wiels, V.; Delmas, D.; Delseny, H. Formal Verification of Avionics Software Products. In Proceedings of the FM 2009: Formal Methods. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2009; pp. 532–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Khazem, K.; Kroening, D.; Tasiran, S.; Tautschnig, M.; Tuttle, M.R. Model checking boot code from AWS data centers. In Proceedings of the CAV 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, E.; Peled, D. , Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 548–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-39910-0-24.Code. In Verification: Theory and Practice: Essays Dedicated to Zohar Manna on the Occasion of His 64th Birthday; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 548–567. [Google Scholar]

- Amusuo, P.C.; Patil, P.V.; Cochell, O.; Lievre, T.L.; Davis, J.C. Enabling Unit Proofing for Software Implementation Verification, 2024. arXiv:2410. 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusuo, P.C.; Cochell, O.; Lievre, T.L.; Patil, P.V.; Machiry, A.; Davis, J.C. Do Unit Proofs Work? An Empirical Study of Compositional Bounded Model Checking for Memory Safety Verification, 2025. arXiv:2503. 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, N.; Schulte, W. Parameterized unit tests. ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes 2005, 30, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, E.; Genaim, S.; Masud, A.N. On the Inference of Resource Usage Upper and Lower Bounds. ACM Transactions on Computational Logic 2013, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

We wish to emphasize that this is not test analysis in the sense that tests are analysed to asses quality, e.g., coverage. |

| 2 |

representing true and false, respectively. |

Figure 1 .

Unit test for max.

Figure 1 .

Unit test for max.

Figure 2 .

CBMC harness for testing max.

Figure 2 .

CBMC harness for testing max.

Figure 3 .

Original loop structure.

Figure 3 .

Original loop structure.

Figure 4 .

Loop unrolled three times with unwinding assertion.

Figure 4 .

Loop unrolled three times with unwinding assertion.

Figure 5 .

Test Execution and Test Analysis frameworks are very similar.

Figure 5 .

Test Execution and Test Analysis frameworks are very similar.

Figure 6 .

C code to bounded model checking formula.

Figure 6 .

C code to bounded model checking formula.

Figure 7 .

A rich test of the max function.

Figure 7 .

A rich test of the max function.

Figure 8 .

Workflow of the testing framework: sources & tests →runit→test.c→CBMC→ runit, with runit also producing an output.

Figure 8 .

Workflow of the testing framework: sources & tests →runit→test.c→CBMC→ runit, with runit also producing an output.

Figure 9 .

Rich tests of a faulty gcd function.

Figure 9 .

Rich tests of a faulty gcd function.

Figure 10 .

Output when executing rUnit on the GCD test cases.

Figure 10 .

Output when executing rUnit on the GCD test cases.

Figure 11 .

Property-based stub of max.

Figure 11 .

Property-based stub of max.

Figure 12 .

maxinlist function using the max function.

Figure 12 .

maxinlist function using the max function.

Figure 13 .

Property-based stub of max.

Figure 13 .

Property-based stub of max.

Figure 14 .

NFA for recognizing .*/sys.log. In the NFA, * means any character.

Figure 14 .

NFA for recognizing .*/sys.log. In the NFA, * means any character.

Figure 15 .

C matching function to ensure path is matched by regular expression ".*sysŀog".

Figure 15 .

C matching function to ensure path is matched by regular expression ".*sysŀog".

Figure 16 .

C function to ensure a URL is of type https.

Figure 16 .

C function to ensure a URL is of type https.

Figure 17 .

Rich tests of isvalidpassword.

Figure 17 .

Rich tests of isvalidpassword.

Figure 18 .

Ordinary unit tests for pathsplit.

Figure 18 .

Ordinary unit tests for pathsplit.

Figure 19 .

Rich test of pathsplit.

Figure 19 .

Rich test of pathsplit.

Figure 20 .

Function countfiles.

Figure 20 .

Function countfiles.

Figure 21 .

Rich test of countfiles.

Figure 21 .

Rich test of countfiles.

Table 1 .

Example regular expressions

Table 1 .

Example regular expressions

| Regular Expression |

Description |

Examples |

| constant |

The exact string "constant" |

"constant" |

| a* |

One or more a |

"", "a", "aaa", ... |

| .* |

All strings |

"", "a", "abcdef", ... |

| .*/sys.log |

All paths for a file sys.log |

"/sys.log", "/var/log/sys.log", ... |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).