Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

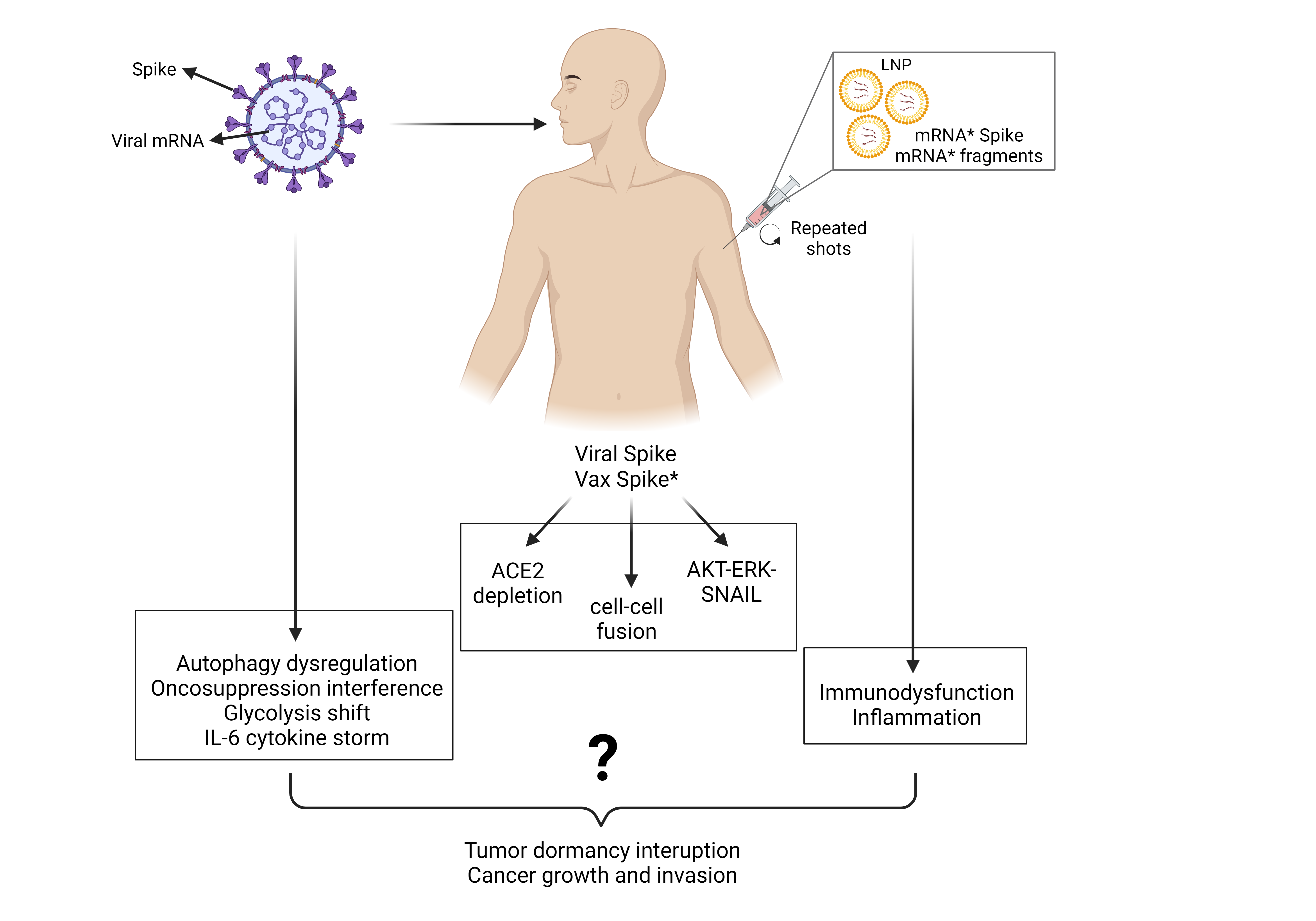

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Virus, the Cancer, and the mRNA Vaccine: the Ugly, the Bad, and the Good?

2.1. The Cancer

2.2. The Virus

2.3. The Vaccine

3. The Complex Interplay Between COVID-19, Anti-COVID-19 mRNA Pro-Vaccine and Cancer

4. Can SARS-CoV2 and/or Anti-COVID-19 mRNA Pro-Vaccine Cause Cancer? Putting the Puzzle Pieces Together

5. The SARS-CoV2 Virus and the Cancer

5.1. Oncogenic Potential of SARS-CoV2 Receptors ACE2 and AXL

5.2. SARS-CoV2 Spike Protein Can Trigger Oncogenic Signaling Pathways

5.3. SARS-CoV2 Spike Protein Can Inactivate Tumor Suppressor Signaling Pathways

5.4. Spike Protein Induces Cell-to-Cell Fusion: A Step Toward Cancer Transformation?

5.5. SARS-CoV2 Replication Dysregulates Autophagy: A Step Toward Carcinogenesis?

5.6. SARS-CoV2 Alters Mitochondrial Respiration and Induces Oxidative Stress

5.7. SARS-CoV2 Triggers the Inflammatory Cytokine Storm and Induces Immune Cell Depletion Leading to a Microenvironment Permissive for Relapses and Metastasis

6. The Anti-COVID-19 mRNA Pro-Vaccine and the Cancer

6.1. The Vaccinal Spike Displays Pro-Carcinogenic Properties Like Viral Spike

6.2. Molecular, Biochemical, Genetic and Epigenetic Effects of the mRNA Pro-Vaccine: Hypothesizing the Unpredictable

6.3. Disruption of the Immune Surveillance and Induction of Inflammation: Creating the Condition for Awakening the Dormant Tumor

7. Data from the Real World: Case Reports Linking Anti-COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination and Cancer

| DISEASE (onset) |

CLINICAL FEATURES | HYSTOLOGICAL-BIOLOGICAL FEATURES |

TYPE OF VACCINE | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angio-immunoblastic T-lymphoma (onset 6 months after 2nd dose) | 66-y, man; presented with lymphadenopathies; increased number, size, and metabolic activity (of lymph nodes 8 days after 3rd dose) | Gene mutations: RHO, TET2, DNMT3A, IDH2 | BNT162b2 (March, April, Sept 2021) |

[215] |

| Recurrence of axillary lymphoproliferative disorder (2 days after 1st dose) |

79-y, man; in remission from a primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma cured two years before; presented with ulcerated tumor with surrounding erythema | CD-30 positive lymphoproliferative disorder; TCR gene rearrangement matching the previous 2019 clone | BNT162b2 | [216] |

| Nodal Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (sudden appearance of temporal mass the day after 1st dose) | 80-y, woman; presented with multiple (n. 12) lymphadenopathies at week 6 from 1st dose (week 3 from 2nd dose); increased number (>22) and size (2.5x) in ten weeks | Lymphoid cells positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-2; negative for CD3, BCL6 | BNT162b2 (2 doses, 3 weeks apart) |

[217] |

| Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (cervical mass appearance one week after 2nd dose) | 58-y woman; presented with tumor mass at the angle of the left parotid gland progressively growing from June to September with multiple reactive lymph nodes, and finally operated in October 2021 | Confirmed DLBC NHL positive for CD20, PAX5 and negative for CD30, AE1/AE3; 85% Ki-67 positivity | BNT162b2 22 May; 12 June 2021 |

[218] |

| Extranodal malignant non-HodgkinT/NK-cell lymphoma (ulcerative lesions appeared 3 days after 1st dose) |

53-y man; presented (December 2021) with multiple ulcerative oral lesions appeared shortly after the 1st dose which worsened after the 2nd dose | Tumor proliferation with T cells positive for CD3 and CD7, granzyme B, CD30; negative for CD4, CD8, and CD20 | BNT162b2 6 November; 28 November 2021 |

[218] |

| A) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (two days after 1st dose of mRNA vaccine); B) Recurrence of B-Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (after 1st dose of mRNA vaccine); C) Recurrence of Acute myeloid leukemia (after the booster with BNT162b2) |

A) 49-y woman; presenting with petechiae and bicytopenia, diagnosed with B-ALL; B) 47-y woman; two years before diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma in remission in the last 14 months; C) 67-y woman; diagnosed with AML in 2007 and in remission in the last 14 years after bone marrow transplant. She had two doses of inactivated SARS-CoV2 vaccine in July 2021 and mRNA BNT162b2 in September 2021 |

A) B-ALL: bone marrow showed 20-30% stained with CD19 diffuse positive TdT in blastic cells; B) Bicytopenia and blasts; C) 90% blasts |

BNT162b2 | [219] |

| Four cases of acute myeloid leukemias, one of which extramedullary | A) 61-y man; 30 days after 3rd mRNA dose; B) 28-y woman; 2 weeks after 2nd dose; C) 72-y man; 5 weeks after the 5th dose; D) 60-y man; 1 month after the 4th dose |

A) 80% blastic infiltration; B) bicytopenia; blastic infiltration; C) pancytopenia; 70% blastic infiltration; D) occipital granulocytic sarcoma of CD34, CD123, and MPO positive immature cells; 30% myeloid blasts |

BNT162b2 | [220] |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (lymphadenopathy was observed one day after the 1st dose) | 67-y man; presented with 6 cm subcutaneous lymphadenopathies mass in the left axilla 2 weeks after the 2nd BNT162b2 vaccination | Large, atypical lymphocytes were positive for CD20, BCL2 and MUM-1/IRF4; negative for CD3; over 80% Ki-67 positivity | BNT162b2 (2 doses) |

[221] |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (lymphadenopathy was observed two days after the 1st dose) | 80-y woman; presented with enlarged 4.1 cm axillary nodule that developed 1 day after the 2nd dose; two months later the nodule increased to 6 cm and additional lesions appeared in the mesentery and the left cavernous sinus | Germinal center B-cell DLBC lymphoma positive for CD20, BCL6, BCL2; negative for CD3 and MUM-1/IRF4; over 90% Ki-67 positivity | BNT162b2 (2 doses) |

[221] |

| Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (10 days after the 3rd dose) | 76-y man; presented a fast-growing lesion at the site of the injection 10 days after the 3rd dose. A large erythematous tumor of 6 cm diameter was diagnosed 1 month later. Spontaneous regression after 6 weeks | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma T1bN0M0; positive for CD30, CD4, CD2, CD5, MUM1, and negative for CD20, CD8, TIA1, ALK, EMA, CD56, CD123 and CD68 | BNT162b2 (1st and 2nd dose) Moderna mRNA-1273 (3rd dose) |

[222] |

| High grade sarcoma | 73-y, woman; history of angiomyolipoma in 2019; presented with swelling 2-4 days after 2nd dose developed in 6 cm diameter soft mass in the right upper arm | Grade 3, stage IIIA undifferentiated, pleomorphic high-grade sarcoma | Moderna mRNA-1273 (2 doses) |

[223] |

| Primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders | Series of 14 cases, of which 6 classified as relapse and 8 as primary lesions; complete and partial remission within the 19 months follow-up | N.A. | BNT162b2 | [224] |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (few weeks after the 3rd dose) | 66-y, man; presented with right axillary lymphadenopathy developed 10 days after the 3rd dose, which grew up to 7 cm in the following 3 months | Stage-II anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK negative and CD30 positive, over 90% Ki-67 positivity | BNT162b2 (January, February, October 2021) |

[225] |

| Conjunctival classic Kaposi sarcoma (few weeks after vaccine booster) | 75-y, woman; with complex ophthalmologic history that includes, among others, uveitic glaucoma OU, epiretinal membrane OU, and cystoid macular degeneration OS, presented with irritated conjunctival area |

Conjunctival epithelium shows early squamous metaplasia and positive immunostaining with HHV8 within the CD34 positive vascular proliferation | BNT162b2 (three doses) |

[226] |

| Basaloid carcinoma, wrongly cured as Bell’s palsy for almost 8 months (symptoms appeared 4 days after 1st dose) | 56-y man; no previous health problems; presented with a massive and aggressively infiltrating basaloid-featured cancer in the right side of his face that rapidly progressed and led the patient to death. CT scan (11 months after vaccination) revealed the presence of infiltrating tumor masses in the parotid gland, likely of cutaneous origin | D-dimer value was 1523 ng/ml (normal range is < 500 ng/ml). Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma |

BNT162b2 (one dose) |

[227] |

| Philadelphia-positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (five days after the booster vaccination with bi-valent mRNA vaccine) | 43-y woman; insignificant previous medical history; presented with splenomegaly, severe anemia and thrombocytopenia along with leukocytosis (1.0% neutrophil, 9.0% lymphocyte, 0% monocyte, eosinophil and basophil, and 90.0% blast) | Bone marrow shows 68% blastic infiltration; cells were positive for CD34 and TdT, negative for CD117 and MPO. The p190 BCR-ABL1 gene rearrangement was identified by RT-PCR | Five vaccinations as follow: two doses of Oxford/AstraZeneca (4 June and 31 August 2021); half-dose of Moderna mRNA-1273 (15 January 2022), NovaVax (15 July 2022), and booster dose of the bivalent (Omicron BA.4/BA.5–containing) mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine (January 2023) plus SARS-CoV-2 infection on 19 August 2021. | [228] |

| Epstein–Barr virus-positive marginal zone lymphoma (EBV + MZL) at autopsy (17 days after 1st vaccination) | 71-y woman; with history of methotrexate-treated rheumatoid arthritis; died due thrombosis and multi-organ failure 17 days after vaccination. The autopsy revealed systemic lymphadenopathy comprising atypical lymphocytes and scattered Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg (H/RS)-like cells | Atypical lymphocytes were positive for CD79a, CD19, EBV-encoded small RNA and MUM-1 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, BCL6. H/RS-like cells were positive for CD3 | Unspecified the type of anti-COVID-19 vaccine | [229] |

| Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma at autopsy (105 days after the second dose) | 61-y woman affected by systemic lupus erythematosus recovered 1 month after vaccination for joint pain, clonic spasms, left-sided paralysis, and fever | Diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with intra- and perivascular infiltration of CD20-positive atypical B lymphocytes in spleen, liver, and lungs | Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (2 doses one month apart) | [230] |

| Longitudinal melanonychia that progressed into subungual melanoma | 53-y woman affected by longitudinal melanonychia with no known risk factors for melanoma development | Malignant transformation into acral lentiginous melanoma within 2 years from vaccination | Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (3 doses) | [231] |

| Breast cancer skin metastasis that manifested 1 month after the 6th dose of mRNA vaccination | 85-y woman affected by breast cancer that was successfully removed by partial mastectomy with clear margins 2 years before | Metastatic cancer cells in the dermis and epidermis showed pagetoid atypical cells with ample cytoplasm features and were positive for spike protein, but not for nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNtech BNT162b2 (six doses in 2 years) | [232] |

| DISEASE | CLINICAL FEATURES | TYPE OF VACCINE | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pheochromocytoma | 63-y man; pheochromocytoma (very rare benign tumor) of 7 cm developed few days after the vaccination | Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine | [233] |

| Recurrence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | T-cell lymphoma has been reported in two patients, who were in remission since many years, after the 2nd | Vaxzevria (Oxford/AstraZeneca) | [234] |

| EBV–positive, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 51-y man; rapidly growing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was reported in a heart post-transplanted (under immunosuppressant therapy since many years) 7 days after receiving the 1st dose | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine | [235] |

| Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | 28-y woman; primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CD31, CD71, CD81 positive) mimicking a panniculites has been reported in a few days after 1st vaccination | COVID-19 Janssen vaccine | [236] |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | 74-y woman; chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and scleroderma were diagnosed, with first signs manifesting two days after receiving the 1st dose, which then progressed to acute myeloid leukemia, severe anemia, and thrombocytopenia, and eventually died due to COVID-19-associated respiratory failure | Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine | [237] |

| Classic Kaposi sarcoma manifested 7 days after the 3rd dose of ChAdOx1 vaccine |

73-y man with a skin nodule of 2×3x1 cm HIV negative, positive for CD34 and HHV-8 | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine | [238] |

8. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gremke N, Griewing S, Bausch E, Alymova S, Wagner U, Kostev K, Kalder M. Therapy delay due to COVID-19 pandemic among European women with breast cancer: prevalence and associated factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Jul 5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37405476. [CrossRef]

- Roderburg C, Loosen SH, Leyh C, Joerdens MS, Mohr R, Luedde T, Alymova S, Klein I, Kostev K. Prevalence of and factors associated with a treatment delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with gastrointestinal cancer in Europe. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Jul 6. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37414990. [CrossRef]

- Burus T, Lei F, Huang B, Christian WJ, Hull PC, Ellis AR, Slavova S, Tucker TC, Lang Kuhs KA. Undiagnosed Cancer Cases in the US During the First 10 Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2024 Apr 1;10(4):500-507. PMID: 38386344; PMCID: PMC10884945. [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco L, Lee R, Brandão M, Cortellini A, Freitas A, Garassino M, Geukens T, Grivas P, Halabi S, Oliveira J, Pinato DJ, Ribeiro J, Peters S, Pentheroudakis G, Warner JL, Romano E. Learning lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for real-world evidence research in oncology-shared perspectives from international consortia. ESMO Open. 2023 Jun 19;8(4):101596. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37418836; PMCID: PMC10277850 . [CrossRef]

- Pinato DJ, Scotti L, Gennari A, Colomba-Blameble E, Dolly S, Loizidou A, Chester J, Mukherjee U, Zambelli A, Aguilar-Company J, Bower M, Galazi M, Salazar R, Bertuzzi A, Brunet J, Mesia R, Sita-Lumsden A, Colomba J, Pommeret F, Seguí E, Biello F, Generali D, Grisanti S, Rizzo G, Libertini M, Moss C, Evans JS, Russell B, Wuerstlein R, Vincenzi B, Bertulli R, Ottaviani D, Liñan R, Marrari A, Carmona-García MC, Sng CCT, Tondini C, Mirallas O, Tovazzi V, Fotia V, Cruz CA, Saoudi-Gonzalez N, Felip E, R Lloveras A, Lee AJX, Newsom-Davis T, Sharkey R, Chung C, García-Illescas D, Reyes R, Sophia Wong YN, Ferrante D, Marco-Hernández J, Ruiz-Camps I, Gaidano G, Patriarca A, Sureda A, Martinez-Vila C, Sanchez de Torre A, Rimassa L, Chiudinelli L, Franchi M, Krengli M, Santoro A, Prat A, Tabernero J, V Hemelrijck M, Diamantis N, Cortellini A; OnCovid study group. Determinants of enhanced vulnerability to coronavirus disease 2019 in UK patients with cancer: a European study. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Jun;150:190-202. Epub 2021 Apr 6. PMID: 33932726; PMCID: PMC8023206. [CrossRef]

- Meslé MMI, Brown J, Mook P, Katz MA, Hagan J, Pastore R, Benka B, Redlberger-Fritz M, Bossuyt N, Stouten V, Vernemmen C, Constantinou E, Maly M, Kynčl J, Sanca O, Krause TG, Vestergaard LS, Leino T, Poukka E, Gkolfinopoulou K, Mellou K, Tsintziloni M, Molnár Z, Aspelund G, Thordardottir M, Domegan L, Kelly E, O'Donell J, Urdiales AM, Riccardo F, Sacco C, Bumšteinas V, Liausediene R, Mossong J, Vergison A, Borg ML, Melillo T, Kocinski D, Pollozhani E, Meijerink H, Costa D, Gomes JP, Leite PP, Druc A, Gutu V, Mita V, Lazar M, Popescu R, Popovici O, Musilová M, Mrzel M, Socan M, Učakar V, Limia A, Mazagatos C, Olmedo C, Dabrera G, Kall M, Sinnathamby M, McGowan G, McMenamin J, Morrison K, Nitzan D, Widdowson MA, Smallwood C, Pebody R; WHO European Respiratory Surveillance Network. Estimated number of lives directly saved by COVID-19 vaccination programmes in the WHO European Region from December, 2020, to March, 2023: a retrospective surveillance study. Lancet Respir Med. 2024 Sep;12(9):714-727. Epub 2024 Aug 7. PMID: 39127051. [CrossRef]

- Sarker R, Roknuzzaman ASM, Nazmunnahar, Shahriar M, Hossain MJ, Islam MR. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: Way to come back in the normal life. Health Sci Rep. 2023 Sep 5;6(9):e1544. PMID: 37674622; PMCID: PMC10478644. [CrossRef]

- Ugai T, Sasamoto N, Lee HY, Ando M, Song M, Tamimi RM, Kawachi I, Campbell PT, Giovannucci EL, Weiderpass E, Rebbeck TR, Ogino S. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022 Oct;19(10):656-673. Epub 2022 Sep 6. PMID: 36068272; PMCID: PMC9509459. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49. Epub 2024 Jan 17. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Mar-Apr;74(2):203. PMID: 38230766. doi: 10.3322/caac.21830. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg PS, Miranda-Filho A. Cancer Incidence Trends in Successive Social Generations in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jun 3;7(6):e2415731. PMID: 38857048; PMCID: PMC11165384. [CrossRef]

- Seegers V, Rousseau G, Zhou K, Blanc-Lapierre A, Bigot F, Mahammedi H, Lambert A, Moreau-Bachelard C, Campone M, Conroy T, Penault-Llorca F, Bellanger MM, Raoul JL. COVID-19 Infection despite Previous Vaccination in Cancer Patients and Healthcare Workers: Results from a French Prospective Multicenter Cohort (PAPESCO-19). Cancers (Basel). 2023 Sep 28;15(19):4777. PMID: 37835471; PMCID: PMC10571737. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt AL, Labaki C, Hsu CY, Bakouny Z, Balanchivadze N, Berg SA, Blau S, Daher A, El Zarif T, Friese CR, Griffiths EA, Hawley JE, Hayes-Lattin B, Karivedu V, Latif T, Mavromatis BH, McKay RR, Nagaraj G, Nguyen RH, Panagiotou OA, Portuguese AJ, Puc M, Santos Dutra M, Schroeder BA, Thakkar A, Wulff-Burchfield EM, Mishra S, Farmakiotis D, Shyr Y, Warner JL, Choueiri TK; COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. COVID-19 vaccination and breakthrough infections in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022 Mar;33(3):340-346. Epub 2021 Dec 24. PMID: 34958894; PMCID: PMC8704021. [CrossRef]

- Anand ST, Vo AD, La J, Do NV, Fillmore NR, Brophy M, Branch-Elliman W, Monach PA. Severe COVID-19 in Vaccinated Adults with Hematologic Cancers in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Feb 5;7(2):e240288. PMID: 38393725; PMCID: PMC10891464. [CrossRef]

- Bellavite P, Donzelli A, Isidoro C. The WHO Algorithm for Causality Assessment of Adverse Effects Following Immunization with Genetic-Based Anti-COVID-19 Vaccines: Pitfalls and Suggestions for Improvement. J Clin Med. 2024 Nov 30;13(23):7291. PMID: 39685749; PMCID: PMC11642405. [CrossRef]

- Ayuso JM, Ochoa Garrido I. The Importance of the Tumor Microenvironment to Understand Tumor Origin, Evolution, and Treatment Response. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Apr 14;14(8):1983. PMID: 35454888; PMCID: PMC9030088. [CrossRef]

- Beatrice Garavaglia, Letizia Vallino, Alessandra Ferraresi, Danny N. Dhanasekaran, Ciro Isidoro, Chapter 12 - Tumor evolution during chemotherapy (pages 285-305) in Peritoneal Tumor Microenvironment of Cancers on Cancer Hallmarks (Academic Press, 2024; ISBN 9780128240403), Yong Sang Song, Danny N. Dhanasekaran, Benjamin K. Tsang, Johji Inazawa, Massoud Mirshahi, Marc Pocard, Ciro Isidoro Editors. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128240403000121). [CrossRef]

- Hanahan D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022 Jan;12(1):31-46. PMID: 35022204. [CrossRef]

- Sinkala M. Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 7;13(1):12742. PMID: 37550388; PMCID: PMC10406856. [CrossRef]

- Recillas-Targa F. Cancer Epigenetics: An Overview. Arch Med Res. 2022 Dec;53(8):732-740. Epub 2022 Nov 18. PMID: 36411173. [CrossRef]

- Nohmi T. Thresholds of Genotoxic and Non-Genotoxic Carcinogens. Toxicol Res. 2018 Oct;34(4):281-290. Epub 2018 Oct 15. PMID: 30370002; PMCID: PMC6195886. [CrossRef]

- Imyanitov EN, Kuligina ES, Sokolenko AP, Suspitsin EN, Yanus GA, Iyevleva AG, Ivantsov AO, Aleksakhina SN. Hereditary cancer syndromes. World J Clin Oncol. 2023 Feb 24;14(2):40-68. PMID: 36908677; PMCID: PMC9993141. [CrossRef]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, McLaren S, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Quail MA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, Carter NP, Morsberger LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Follows GA, Green AR, Flanagan AM, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Campbell PJ. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011 Jan 7;144(1):27-40. PMID: 21215367; PMCID: PMC3065307. [CrossRef]

- Adashek JJ, Kato S, Lippman SM, Kurzrock R. The paradox of cancer genes in non-malignant conditions: implications for precision medicine. Genome Med. 2020 Feb 17;12(1):16. PMID: 32066498; PMCID: PMC7027240. [CrossRef]

- Fiala, C., Diamandis, E.P. Mutations in normal tissues—some diagnostic and clinical implications. BMC Med 18, 283 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Baker SG. A cancer theory kerfuffle can lead to new lines of research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Dec 20;107(2):dju405. PMID: 25528755; PMCID: PMC4326310. [CrossRef]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020 Apr;5(4):536-544. Epub 2020 Mar 2. PMID: 32123347; PMCID: PMC7095448. [CrossRef]

- Nazerian Y, Ghasemi M, Yassaghi Y, Nazerian A, Hashemi SM. Role of SARS-CoV-2-induced cytokine storm in multi-organ failure: Molecular pathways and potential therapeutic options. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022 Dec;113(Pt B):109428. Epub 2022 Nov 7. PMID: 36379152; PMCID: PMC9637536. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., Pushpakumar, S., Zheng, Y. et al. Novel mechanism of the COVID-19 associated coagulopathy (CAC) and vascular thromboembolism. npj Viruses 1, 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Brant AC, Tian W, Majerciak V, Yang W, Zheng ZM. SARS-CoV-2: from its discovery to genome structure, transcription, and replication. Cell Biosci. 2021 Jul 19;11(1):136. PMID: 34281608; PMCID: PMC8287290. [CrossRef]

- V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021 Mar;19(3):155-170. Epub 2020 Oct 28. PMID: 33116300; PMCID: PMC7592455. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh S, Dellibovi-Ragheb TA, Kerviel A, et al. b-Coronaviruses use lysosomes for egress instead of the biosynthetic secretory pathway. Cell. 2020;183(6):1520e1535. e14 . [CrossRef]

- Vidoni C, Fuzimoto A, Ferraresi A, Isidoro C. Targeting autophagy with natural products to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Tradit Complement Med. 2022 Jan;12(1):55-68. Epub 2021 Oct 14. PMID: 34664025; PMCID: PMC8516241. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., Bowman, J.W. & Jung, J.U. Autophagy during viral infection — a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 341–354 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Sun H, Pei R, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF3a inhibits fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Cell Discov. 2021;7(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Tao S, Drexler I. Targeting Autophagy in Innate Immune Cells: Angel or Demon During Infection and Vaccination? Front Immunol. 2020 Mar 19;11:460. PMID: 32265919; PMCID: PMC7096474. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Yu J, Wong SH, Chan MTV, Zhang L, Wu WKK. SARS-CoV-2 targets the lysosome to mediate airway inflammatory cell death. Autophagy. 2022 Sep;18(9):2246-2248. Epub 2022 Jan 22. PMID: 35067165; PMCID: PMC9397439. [CrossRef]

- Yong YY, Zhang L, Hu YJ, Wu JM, Yan L, Pan YR, Tang Y, Yu L, Law BY, Yu CL, Zhou J, Li M, Qin DL, Zhou XG, Wu AG. Targeting autophagy regulation in NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated lung inflammation in COVID-19. Clin Immunol. 2022 Nov;244:109093. Epub 2022 Aug 6. PMID: 35944881; PMCID: PMC9356669. [CrossRef]

- Resnik R, Lopez Mingorance F, Rivera F, Mitchell F, Gonzalez CD, Vaccaro MI. Autophagy in Inflammatory Response against SARS-CoV-2. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 3;24(5):4928. PMID: 36902354; PMCID: PMC10002778. [CrossRef]

- Afshar ZM, Dayani M, Naderi M, Ghanbarveisi F, Shiri S, Rajati F. Fatality rate of COVID-19 in patients with malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020 Aug;81(2):e114-e116. Epub 2020 May 28. PMID: 32474042; PMCID: PMC7255731. [CrossRef]

- Gallo O, Locatello LG, Orlando P, Martelli F, Piccica M, Lagi F, Trotta M. Cancer population may be paradoxically protected from severe manifestations of COVID-19. J Infect. 2020 Aug;81(2):e156-e158. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32534002; PMCID: PMC7286269. [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli S, Tebaldi M, Fonzi E, Angeli D, Mazza M, Nicolini F, Lucchesi A, Fanini F, Pirini F, Tumedei MM, Cerchione C, Viale P, Sambri V, Martinelli G, Bravaccini S. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 Potential Involvement in Genetic Susceptibility to SARS-COV-2 in Cancer Patients. Cell Transplant. 2020 Jan-Dec;29:963689720968749. PMID: 33108902; PMCID: PMC7593730. [CrossRef]

- Montopoli M, Zumerle S, Vettor R, Rugge M, Zorzi M, Catapano CV, Carbone GM, Cavalli A, Pagano F, Ragazzi E, Prayer-Galetti T, Alimonti A. Androgen-deprivation therapies for prostate cancer and risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2: a population-based study (N = 4532). Ann Oncol. 2020 Aug;31(8):1040-1045. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32387456; PMCID: PMC7202813. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Qiu Z, Hou Y, Deng X, Xu W, Zheng T, Wu P, Xie S, Bian W, Zhang C, Sun Z, Liu K, Shan C, Lin A, Jiang S, Xie Y, Zhou Q, Lu L, Huang J, Li X. AXL is a candidate receptor for SARS-CoV-2 that promotes infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Res. 2021 Feb;31(2):126-140. [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Ojha R, Pedro LD, Djannatian M, Franz J, Kuivanen S, van der Meer F, Kallio K, Kaya T, Anastasina M, Smura T, Levanov L, Szirovicza L, Tobi A, Kallio-Kokko H, Österlund P, Joensuu M, Meunier FA, Butcher SJ, Winkler MS, Mollenhauer B, Helenius A, Gokce O, Teesalu T, Hepojoki J, Vapalahti O, Stadelmann C, Balistreri G, Simons M. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science. 2020 Nov 13;370(6518):856-860. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Chen, W., Zhang, Z. et al. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Sig Transduct Target Ther 5, 283 (2020). [CrossRef]

- You J, Huang R, Zhong R, Shen J, Huang S, Chen J, Chen F, Kang Y, Chen L. Serum AXL is a potential molecular marker for predicting COVID-19 progression. Front Immunol. 2024 May 10;15:1394429. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Wang Y, Xu D, Xiao L, Qin W, Liu B, Yuan X. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 co-receptor NRP1 expression profiles in healthy people and cancer patients: Implication for susceptibility to COVID-19 disease and potential therapeutic strategy. Front Genet. 2022 Oct 19;13:995736. [CrossRef]

- Xia P, Dubrovska A. Tumor markers as an entry for SARS-CoV-2 infection? FEBS J. 2020 Sep;287(17):3677-3680. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt F, Ellinghaus D, Juzenas S, Lerga-Jaso J, Wendorff M, Maya-Miles D, Uellendahl-Werth F, ElAbd H, Rühlemann MC, Arora J, Özer O, Lenning OB, Myhre R, Vadla MS, Wacker EM, Wienbrandt L, Blandino Ortiz A, de Salazar A, Garrido Chercoles A, Palom A, Ruiz A, Garcia-Fernandez AE, Blanco-Grau A, Mantovani A, Zanella A, Holten AR, Mayer A, Bandera A, Cherubini A, Protti A, Aghemo A, Gerussi A, Ramirez A, Braun A, Nebel A, Barreira A, Lleo A, Teles A, Kildal AB, Biondi A, Caballero-Garralda A, Ganna A, Gori A, Glück A, Lind A, Tanck A, Hinney A, Carreras Nolla A, Fracanzani AL, Peschuck A, Cavallero A, Dyrhol-Riise AM, Ruello A, Julià A, Muscatello A, Pesenti A, Voza A, Rando-Segura A, Solier A, Schmidt A, Cortes B, Mateos B, Nafria-Jimenez B, Schaefer B, Jensen B, Bellinghausen C, Maj C, Ferrando C, de la Horra C, Quereda C, Skurk C, Thibeault C, Scollo C, Herr C, Spinner CD, Gassner C, Lange C, Hu C, Paccapelo C, Lehmann C, Angelini C, Cappadona C, Azuure C; COVICAT study group, Aachen Study (COVAS); Bianco C, Cea C, Sancho C, Hoff DAL, Galimberti D, Prati D, Haschka D, Jiménez D, Pestaña D, Toapanta D, Muñiz-Diaz E, Azzolini E, Sandoval E, Binatti E, Scarpini E, Helbig ET, Casalone E, Urrechaga E, Paraboschi EM, Pontali E, Reverter E, Calderón EJ, Navas E, Solligård E, Contro E, Arana-Arri E, Aziz F, Garcia F, García Sánchez F, Ceriotti F, Martinelli-Boneschi F, Peyvandi F, Kurth F, Blasi F, Malvestiti F, Medrano FJ, Mesonero F, Rodriguez-Frias F, Hanses F, Müller F, Hemmrich-Stanisak G, Bellani G, Grasselli G, Pezzoli G, Costantino G, Albano G, Cardamone G, Bellelli G, Citerio G, Foti G, Lamorte G, Matullo G, Baselli G, Kurihara H, Neb H, My I, Kurth I, Hernández I, Pink I, de Rojas I, Galván-Femenia I, Holter JC, Afset JE, Heyckendorf J, Kässens J, Damås JK, Rybniker J, Altmüller J, Ampuero J, Martín J, Erdmann J, Banales JM, Badia JR, Dopazo J, Schneider J, Bergan J, Barretina J, Walter J, Hernández Quero J, Goikoetxea J, Delgado J, Guerrero JM, Fazaal J, Kraft J, Schröder J, Risnes K, Banasik K, Müller KE, Gaede KI, Garcia-Etxebarria K, Tonby K, Heggelund L, Izquierdo-Sanchez L, Bettini LR, Sumoy L, Sander LE, Lippert LJ, Terranova L, Nkambule L, Knopp L, Gustad LT, Garbarino L, Santoro L, Téllez L, Roade L, Ostadreza M, Intxausti M, Kogevinas M, Riveiro-Barciela M, Berger MM, Schaefer M, Niemi MEK, Gutiérrez-Stampa MA, Carrabba M, Figuera Basso ME, Valsecchi MG, Hernandez-Tejero M, Vehreschild MJGT, Manunta M, Acosta-Herrera M, D'Angiò M, Baldini M, Cazzaniga M, Grimsrud MM, Cornberg M, Nöthen MM, Marquié M, Castoldi M, Cordioli M, Cecconi M, D'Amato M, Augustin M, Tomasi M, Boada M, Dreher M, Seilmaier MJ, Joannidis M, Wittig M, Mazzocco M, Ciccarelli M, Rodríguez-Gandía M, Bocciolone M, Miozzo M, Imaz Ayo N, Blay N, Chueca N, Montano N, Braun N, Ludwig N, Marx N, Martínez N; Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 Study group; Cornely OA, Witzke O, Palmieri O; Pa Study Group; Faverio P, Preatoni P, Bonfanti P, Omodei P, Tentorio P, Castro P, Rodrigues PM, España PP, Hoffmann P, Rosenstiel P, Schommers P, Suwalski P, de Pablo R, Ferrer R, Bals R, Gualtierotti R, Gallego-Durán R, Nieto R, Carpani R, Morilla R, Badalamenti S, Haider S, Ciesek S, May S, Bombace S, Marsal S, Pigazzini S, Klein S, Pelusi S, Wilfling S, Bosari S, Volland S, Brunak S, Raychaudhuri S, Schreiber S, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Aliberti S, Ripke S, Dudman S, Wesse T, Zheng T; STORM Study group, The Humanitas Task Force, The Humanitas Gavazzeni Task Force; Bahmer T, Eggermann T, Illig T, Brenner T, Pumarola T, Feldt T, Folseraas T, Gonzalez Cejudo T, Landmesser U, Protzer U, Hehr U, Rimoldi V, Monzani V, Skogen V, Keitel V, Kopfnagel V, Friaza V, Andrade V, Moreno V, Albrecht W, Peter W, Poller W, Farre X, Yi X, Wang X, Khodamoradi Y, Karadeniz Z, Latiano A, Goerg S, Bacher P, Koehler P, Tran F, Zoller H, Schulte EC, Heidecker B, Ludwig KU, Fernández J, Romero-Gómez M, Albillos A, Invernizzi P, Buti M, Duga S, Bujanda L, Hov JR, Lenz TL, Asselta R, de Cid R, Valenti L, Karlsen TH, Cáceres M, Franke A. Detailed stratified GWAS analysis for severe COVID-19 in four European populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2022 Nov 28;31(23):3945-3966. PMID: 35848942; PMCID: PMC9703941. [CrossRef]

- Corley MJ, Pang APS, Dody K, Mudd PA, Patterson BK, Seethamraju H, Bram Y, Peluso MJ, Torres L, Iyer NS, Premeaux TA, Yeung ST, Chandar V, Borczuk A, Schwartz RE, Henrich TJ, Deeks SG, Sacha JB, Ndhlovu LC. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of peripheral blood reveals an epigenetic signature associated with severe COVID-19. J Leukoc Biol. 2021 Jul;110(1):21-26. Epub 2021 Jan 19. PMID: 33464637; PMCID: PMC8013321. [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi A, Isidoro C. Will Omics Biotechnologies Save Us from Future Pandemics? Lessons from COVID-19 for Vaccinomics and Adversomics. Biomedicines. 2022 Dec 26;11(1):52. PMID: 36672560; PMCID: PMC9855897. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh M, Kumar S, Ganguly K, Ghosh P, Tabassum S, Basu B, Basu M. COVID-19 and cancer: insights into their association and influence on genetic and epigenetic landscape. Epigenomics. 2023 Feb;15(4):227–48. Epub 2023 May 2. PMCID: PMC10155782.

- Qiu S, Hu Y. Are COVID-19 susceptibility genes related to lung cancer? J Infect. 2021 Nov;83(5):607-635. Epub 2021 Aug 23. PMID: 34437926; PMCID: PMC8381633. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2023-0052. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Mao Q, Li Y, Cheng J, Xia Q, Chen G, Chen P, Jin S, Li D, Zhong C, Yang J, Fan X, Liang Y, Lin H. Cancer and COVID-19 Susceptibility and Severity: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization and Bioinformatic Analysis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Jan 24;9:759257. PMID: 35141230; PMCID: PMC8818950. [CrossRef]

- Gusakova MS, Ivanov MV, Kashtanova DA, Taraskina AN, Erema VV, Mikova VM, Loshkarev RI, Ignatyeva OA, Akinshina AI, Mitrofanov SI, Snigir EA, Yudin VS, Makarov VV, Keskinov AA, Yudin SM. GWAS reveals genetic basis of a predisposition to severe COVID-19 through in silico modeling of the FYCO1 protein. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Jul 20;10:1178939. PMID: 37547597; PMCID: PMC10399629. [CrossRef]

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Pérez Marc G, Moreira ED, Zerbini C, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Roychoudhury S, Koury K, Li P, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Frenck RW Jr, Hammitt LL, Türeci Ö, Nell H, Schaefer A, Ünal S, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603-2615. [CrossRef]

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Khetan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5):403-416. [CrossRef]

- Beukenhorst AL, Koch CM, Hadjichrysanthou C, Alter G, de Wolf F, Anderson RM, Goudsmit J. SARS-CoV-2 elicits non-sterilizing immunity and evades vaccine-induced immunity: implications for future vaccination strategies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2023 Mar;38(3):237-242. Epub 2023 Feb 4. PMID: 36738380; PMCID: PMC9898703. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura M, Sakamoto A, Ozuru R, Kurihara Y, Itoh R, Ishii K, Shimizu A, Chou B, Sechi Y, Fujikane A, Nabeshima S, Hiromatsu K. Insufficient anti-spike RBD IgA responses after triple vaccination with intramuscular mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Heliyon. 2023 Dec 13;10(1):e23595. PMID: 38187240; PMCID: PMC10770545. [CrossRef]

- Irrgang P, Gerling J, Kocher K, Lapuente D, Steininger P, Habenicht K, Wytopil M, Beileke S, Schäfer S, Zhong J, Ssebyatika G, Krey T, Falcone V, Schülein C, Peter AS, Nganou-Makamdop K, Hengel H, Held J, Bogdan C, Überla K, Schober K, Winkler TH, Tenbusch M. Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol. 2023 Jan 27;8(79):eade2798. Epub 2023 Jan 27. PMID: 36548397; PMCID: PMC9847566. [CrossRef]

- Kiszel P, Sík P, Miklós J, Kajdácsi E, Sinkovits G, Cervenak L, Prohászka Z. Class switch towards spike protein-specific IgG4 antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination depends on prior infection history. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 13;13(1):13166. PMID: 37574522; PMCID: PMC10423719. [CrossRef]

- Hwang JK, Zhang T, Wang AZ, et al: COVID-19 vaccines for patients with cancer: Benefits likely outweigh risks. J Hematol Oncol 14:38, 2021.

- Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-COV-2: a multi-center study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov 2020:CD-20-0422.

- Corti C, Crimini E, Tarantino P, Pravettoni G, Eggermont AMM, Delaloge S, Curigliano G. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for cancer patients: a call to action. Eur J Cancer. 2021 May;148:316-327. [CrossRef]

- Ljungman P, Nahi H, Linde A. Vaccination of patients with haematological malignancies with one or two doses of influenza vaccine: a randomised study. Br J Haematol 2005;130:96–8.

- Mackay HJ, McGee J, Villa D, et al. Evaluation of pandemic H1N1 (2009) influenza vaccine in adults with solid tumor and hematological malignancies on active systemic treatment. Journal of Clinical Virology 2011;50:212–6.

- Sommer AL, Wachel BK, Smith JA. Evaluation of vaccine dosing in patients with solid tumors receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2006;12:143–54.

- Shumilov E, Aperdannier L, Schmidt N, Szuszies C, Neesse A, Hoffknecht P, Khandanpour C, Mikesch JH, Stelljes M, Boeckel GR, Tepasse PR, Reitnauer L, Koch R, Hasenkamp J, Bacher U, Scheithauer S, Trümper L, Schmitz N, Wulf G, Kerkhoff A, Lenz G, Krekeler C, Bleckmann A. Clinical Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection Scenarios in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Cancer Patients in Three German Cancer Centers: A Retrospective Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jul 31;14(15):3746. [CrossRef]

- Song Q, Bates B, Shao YR, Hsu FC, Liu F, Madhira V, Mitra AK, Bergquist T, Kavuluru R, Li X, Sharafeldin N, Su J, Topaloglu U. Risk and Outcome of Breakthrough COVID-19 Infections in Vaccinated Patients With Cancer: Real-World Evidence From the National COVID Cohort Collaborative. J Clin Oncol. 2022 May 1;40(13):1414-1427. Epub 2022 Mar 14. PMID: 35286152; PMCID: PMC9061155. [CrossRef]

- Campagna R, Dominelli F, Zingaropoli MA, Ciurluini F, Grilli G, Amoroso A, De Domenico A, Amatore D, Lia MS, Cortesi E, Picone V, Mastroianni CM, Ciardi MR, De Santis R, Lista F, Antonelli G, Turriziani O. COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients: Immune responses one year after the third dose. Vaccine. 2024 Apr 11;42(10):2687-2694. Epub 2024 Mar 17. PMID: 38499458. [CrossRef]

- Hua T, Fan R, Fan Y, Chen F. Immune response of COVID-19 vaccines in solid cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024 Dec 31;20(1):2357424. Epub 2024 May 24. PMID: 38785118; PMCID: PMC11135846. [CrossRef]

- Gong IY, Vijenthira A, Powis M, Calzavara A, Patrikar A, Sutradhar R, Hicks LK, Wilton D, Singh S, Krzyzanowska MK, Cheung MC. Association of COVID-19 Vaccination With Breakthrough Infections and Complications in Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023 Mar 1;9(3):386-394. PMID: 36580318; PMCID: PMC10020872. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Berger NA. COVID-19 breakthrough infections, hospitalizations and mortality in fully vaccinated patients with hematologic malignancies: A clarion call for maintaining mitigation and ramping-up research. Blood Rev. 2022 Jul;54:100931. Epub 2022 Jan 31. PMID: 35120771; PMCID: PMC8802493. [CrossRef]

- Seegers V, Rousseau G, Zhou K, Blanc-Lapierre A, Bigot F, Mahammedi H, Lambert A, Moreau-Bachelard C, Campone M, Conroy T, Penault-Llorca F, Bellanger MM, Raoul JL. COVID-19 Infection despite Previous Vaccination in Cancer Patients and Healthcare Workers: Results from a French Prospective Multicenter Cohort (PAPESCO-19). Cancers (Basel). 2023 Sep 28;15(19):4777. PMID: 37835471; PMCID: PMC10571737. [CrossRef]

- Anand ST, Vo AD, La J, Do NV, Fillmore NR, Brophy M, Branch-Elliman W, Monach PA. Severe COVID-19 in Vaccinated Adults with Hematologic Cancers in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Feb 5;7(2):e240288. PMID: 38393725; PMCID: PMC10891464. [CrossRef]

- Amatu A, Pani A, Patelli G, Gagliardi OM, Loparco M, Piscazzi D, Cassingena A, Tosi F, Ghezzi S, Campisi D, Grifantini R, Abrignani S, Siena S, Scaglione F, Sartore-Bianchi A. Impaired seroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with solid tumours receiving anticancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Mar;163:16-25. Epub 2021 Dec 22. PMID: 35032813; PMCID: PMC8692068. [CrossRef]

- Buttiron Webber T, Provinciali N, Musso M, Ugolini M, Boitano M, Clavarezza M, D'Amico M, Defferrari C, Gozza A, Briata IM, Magnani M, Paciolla F, Menghini N, Marcenaro E, De Palma R, Sacchi N, Innocenti L, Siri G, D'Ecclesiis O, Cevasco I, Gandini S, DeCensi A. Predictors of poor seroconversion and adverse events to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in cancer patients on active treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Dec;159:105-112. Epub 2021 Oct 11. PMID: 34742157; PMCID: PMC8502731. [CrossRef]

- Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood (2021) 137 (23): 3165–3173. [CrossRef]

- Vormehr M, Lehar S, Kranz LM, et al. Dexamethasone premedication suppresses vaccine-induced immune responses against cancer. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1758004.

- Verma V, Shrimali RK, Ahmad S, et al. Pd-1 blockade in subprimed CD8 cells induces dysfunctional PD-1+CD38hi cells and anti-PD-1 resistance. Nat Immunol 2019;20:1231–43.

- Spiliopoulou P, Janse van Rensburg HJ, Avery L, Kulasingam V, Razak A, Bedard P, Hansen A, Chruscinski A, Wang B, Kulikova M, Chen R, Speers V, Nguyen A, Lee J, Coburn B, Spreafico A, Siu LL. Longitudinal efficacy and toxicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2023 Jan 20;14(1):49. PMID: 36670100; PMCID: PMC9853486. [CrossRef]

- Nelli, F., Giannarelli, D., Fabbri, A. et al. Immune-related adverse events and disease outcomes after the third dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-BNT162b2 vaccine in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2023). [CrossRef]

- Echaide M, Labiano I, Delgado M, Fernández de Lascoiti A, Ochoa P, Garnica M, Ramos P, Chocarro L, Fernández L, Arasanz H, Bocanegra A, Blanco E, Piñeiro-Hermida S, Morente P, Vera R, Alsina M, Escors D, Kochan G. Immune Profiling Uncovers Memory T-Cell Responses with a Th17 Signature in Cancer Patients with Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection Followed by mRNA Vaccination. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Sep 14;14(18):4464. PMID: 36139625; PMCID: PMC9496802. [CrossRef]

- Alshehri S, Almutawif YA, Khan NU. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on cancer patients: safety, efficacy, and long-term effects. Support Care Cancer. 2025 Aug 4;33(8):753. PMID: 40760361. [CrossRef]

- Benitez Fuentes JD, Mohamed Mohamed K, de Luna Aguilar A, Jiménez García C, Guevara-Hoyer K, Fernandez-Arquero M, Rodríguez de la Peña MA, Garciía Bravo L, Jiménez Ortega AF, Flores Navarro P, Bartolome Arcilla J, Alonso Arenilla B, Baos Muñoz E, Delgado-Iribarren García-Campero A, Montealegre Sanz M, Sanchez-Ramon S, Perez Segura P. Evidence of exhausted lymphocytes after the third anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose in cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2022 Dec 20;12:975980. PMID: 36605446; PMCID: PMC9808030. [CrossRef]

- Raineri D, Mazzucca CB, Moia R, Bruna R, Kustrimovic N, Cappellano G, Bellan M, Perazzi M, Gaidano G, Chiocchetti A. Impairment of the T cell memory response in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Vaccine. 2025 Feb 27;48:126723. Epub 2025 Jan 18. PMID: 39827600. [CrossRef]

- Nelli F, Signorelli C, Fabbri A, Giannarelli D, Virtuoso A, Giron Berrios JR, Marrucci E, Fiore C, Schirripa M, Chilelli MG, Primi F, Panichi V, Topini G, Silvestri MA, Ruggeri EM. Changes in Peripheral Immune Cells after the Third Dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-BNT162b2 Vaccine and Disease Outcomes in Cancer Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Prospective Analysis of the Vax-on-Third-Profile Study. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jul 14;15(14):3625. PMID: 37509286; PMCID: PMC10377319. [CrossRef]

- Grippin AJ, Marconi C, Copling S, Li N, Braun C, Woody C, Young E, Gupta P, Wang M, Wu A, Jeong SD, Soni D, Weidert F, Xie C, Goldenberg E, Kim A, Zhao C, DeVries A, Castillo P, Lohray R, Rooney MK, Schrank BR, Wang Y, Ma Y, Chang E, Kouzy R, Dyson K, Jafarnia J, Nariman N, Gladish G, New J, Argueta A, Amaya D, Thomas N, Doty A, Chen J, Copling N, Alatrash G, Simon J, Davies AB, Dennis W, Liang R, Lewis J, Wei X, Rinsurongkawong W, Vaporciyan AA, Johns A; D3CODE Team; Lee J, Lee JH, Sun R, Sharma P, Tran H, Zhang J, Gibbons DL, Wargo J, Kim BYS, Heymach JV, Mendez-Gomez HR, Jiang W, Sayour EJ, Lin SH. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines sensitize tumours to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature. 2025 Oct 22. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41125896. [CrossRef]

- Meo C, Palma G, Bruzzese F, Budillon A, Napoli C, de Nigris F. Spontaneous cancer remission after COVID-19: insights from the pandemic and their relevance for cancer treatment. J Transl Med. 2023 Apr 21;21(1):273. PMID: 37085802; PMCID: PMC10119533. [CrossRef]

- Sousa LG, McGrail DJ, Li K, Marques-Piubelli ML, Gonzalez C, Dai H, Ferri-Borgogno S, Godoy M, Burks J, Lin SY, Bell D, Ferrarotto R. Spontaneous tumor regression following COVID-19 vaccination. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Mar;10(3):e004371. PMID: 35241495; PMCID: PMC8896046. [CrossRef]

- Gambichler T, Boms S, Hessam S, Tischoff I, Tannapfel A, Lüttringhaus T, Beckman J, Stranzenbach R. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with marked spontaneous regression of organ manifestation after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Dec;185(6):1259-1262. Epub 2021 Oct 3. PMID: 34228815; PMCID: PMC8444914. [CrossRef]

- Wesselmann, UlrichKvasnicka, Hans M.Bozkurt, AhmetWieland, UlrikeHofmann, Silke C. et al. Long lasting complete regression of a metastatic polyomavirus-positive Merkel cell carcinoma after COVID-19 booster vaccination. EJC Skin Cancer, Volume 2, 100275.

- Eslinger C, Uson PLS Jr, Nagalo BM, Borad MJ. Spontaneous regression of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following COVID-19 infection and vaccination: a case report and review of literature. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024 Aug 31;15(4):1933-1938. Epub 2024 Jul 22. PMID: 39279952; PMCID: PMC11399873. [CrossRef]

- Neophytou CM, Kyriakou TC, Papageorgis P. Mechanisms of Metastatic Tumor Dormancy and Implications for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Dec 6;20(24):6158. PMID: 31817646; PMCID: PMC6940943. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang L, Wei Y, Wei C, Yang H, Chen Q, Zhang R, Shen H. Advances in the molecular regulation mechanism of tumor dormancy and its therapeutic strategy. Discov Oncol. 2024 May 25;15(1):184. [CrossRef]

- Gunes D, Ustal A, Ertem YE, Akkoc Y, Gozuacik D. Autophagy in the regulation of cancer dormancy. FEBS Lett. 2025 Aug;599(16):2272-2300. Epub 2025 Aug 13. PMID: 40804788. [CrossRef]

- Esposito A, Ferraresi A, Salwa A, Vidoni C, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. Resveratrol Contrasts IL-6 Pro-Growth Effects and Promotes Autophagy-Mediated Cancer Cell Dormancy in 3D Ovarian Cancer: Role of miR-1305 and of Its Target ARH-I. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Apr 25;14(9):2142. PMID: 35565270; PMCID: PMC9101105. [CrossRef]

- Manjili SH, Isbell M, Ghochaghi N, Perkinson T, Manjili MH. Multifaceted functions of chronic inflammation in regulating tumor dormancy and relapse. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022 Jan;78:17-22. Epub 2021 Mar 27. PMID: 33785450; PMCID: PMC8473586. [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi A, Girone C, Esposito A, Vidoni C, Vallino L, Secomandi E, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. How Autophagy Shapes the Tumor Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020 Dec 7;10:599915. PMID: 33364196; PMCID: PMC7753622. [CrossRef]

- Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited--the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer. 2011 Jun 1;128(11):2527-35. [CrossRef]

- Unterlass JE, Curtin NJ. Warburg and Krebs and related effects in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2019 Sep 27;21:e4. PMID: 31558177. [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; De Giglio, M.A.R.; Roviello, G.N. Deciphering the Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7803.

- Rapti, V.; Tsaganos, T.; Vathiotis, I.A.; Syrigos, N.K.; Li, P.; Poulakou, G. New Insights into SARS-CoV-2 and Cancer Cross-Talk:Does a Novel Oncogenesis Driver Emerge? Vaccines 2022, 10, 1607..

- Venuti A, Donzelli S, Nisticò P, Blandino G, Ciliberto G. Does Interleukin-6 Bridge SARS-CoV-2 With Virus-Associated Cancers? J Immunother Precis Oncol. 2021 Jan 29;4(2):79-85. PMID: 35663529; PMCID: PMC9153257. [CrossRef]

- Vieira C, Nery L, Martins L, Jabour L, Dias R, Simões E Silva AC. Downregulation of Membrane-bound Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Receptor has a Pivotal Role in COVID-19 Immunopathology. Curr Drug Targets. 2021;22(3):254-281. PMID: 33081670. [CrossRef]

- Lei Y, Zhang J, Schiavon CR, He M, Chen L, Shen H, Zhang Y, Yin Q, Cho Y, Andrade L, Shadel GS, Hepokoski M, Lei T, Wang H, Zhang J, Yuan JX, Malhotra A, Manor U, Wang S, Yuan ZY, Shyy JY. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Impairs Endothelial Function via Downregulation of ACE 2. Circ Res. 2021 Apr 30;128(9):1323-1326. Epub 2021 Mar 31. PMID: 33784827; PMCID: PMC8091897. [CrossRef]

- Bellavite P, Ferraresi A, Isidoro C. Immune Response and Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Adverse Effects of Spike Proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and mRNA Vaccines. Biomedicines. 2023 Feb 3;11(2):451. PMID: 36830987; PMCID: PMC9953067. [CrossRef]

- Hassani B, Attar Z, Firouzabadi N. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) signaling pathways and cancer: foes versus allies. Cancer Cell Int. 2023 Oct 27;23(1):254. PMID: 37891636; PMCID: PMC10604988. [CrossRef]

- Menon J, Soto-Pantoja DR, Callahan MF, Cline JM, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits growth of human lung adenocarcinoma xenografts in nude mice through a reduction in cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2007 Mar 15;67(6):2809-15. PMID: 17363603. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Pantoja DR, Menon J, Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits tumor angiogenesis in human lung cancer xenografts with a reduction in vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009 Jun;8(6):1676-83. Epub 2009 Jun 9. PMID: 19509262; PMCID: PMC3314264. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Lu S, Li T, Yu L, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Qian X, Bi J, Lin Y. ACE2 inhibits breast cancer angiogenesis via suppressing the VEGFa/VEGFR2/ERK pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019 Apr 25;38(1):173. PMID: 31023337; PMCID: PMC6482513. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Wan H, Liu J, Zhang R, Ma Q, Han B, Xiang Y, Che J, Cao H, Fei X, Qiu W. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in tumor growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010 Apr;23(4):941-8. PMID: 20204277. [CrossRef]

- Xie P, Guo L, Yu Q, Zhao Y, Yu M, Wang H, Wu M, Xu W, Xu M, Zhu XD, Xu Y, Xiao YS, Huang C, Zhou J, Fan J, Hung MC, Sun H, Ye QH, Zhang B, Li H. ACE2 Enhances Sensitivity to PD-L1 Blockade by Inhibiting Macrophage-Induced Immunosuppression and Angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2025 Jan 15;85(2):299-313. PMID: 39495239. [CrossRef]

- Stewart CA, Gay CM, Ramkumar K, Cargill KR, Cardnell RJ, Nilsson MB, Heeke S, Park EM, Kundu ST, Diao L, Wang Q, Shen L, Xi Y, Zhang B, Della Corte CM, Fan Y, Kundu K, Gao B, Avila K, Pickering CR, Johnson FM, Zhang J, Kadara H, Minna JD, Gibbons DL, Wang J, Heymach JV, Byers LA. Lung Cancer Models Reveal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Contributes to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pathophysiology. J Thorac Oncol. 2021 Nov;16(11):1821-1839. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34274504; PMCID: PMC8282443. [CrossRef]

- Lai YJ, Chao CH, Liao CC, Lee TA, Hsu JM, Chou WC, Wang J, Huang HC, Chang SJ, Lin YL, Li CW. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by SARS-CoV-2 required transcriptional upregulation of Snail. Am J Cancer Res. 2021 May 15;11(5):2278-2290. PMID: 34094684; PMCID: PMC8167694.

- Huang HC, Liao CC, Wang SH, Lee IJ, Lee TA, Hsu JM, Kuo CT, Wang J, Hsieh WC, Chang SJ, Chen SY, Tao MH, Lin YL, Lai YJ, Li CW. Hyperglycosylated spike of SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant induces breast cancer metastasis. Am J Cancer Res. 2021 Oct 15;11(10):4994-5005.

- Yu C, Tang W, Wang Y, Shen Q, Wang B, Cai C, Meng X, Zou F. Downregulation of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing store-operated calcium entry. Cancer Lett. 2016 Jul 1;376(2):268-77. Epub 2016 Apr 7. PMID: 27063099. [CrossRef]

- Catarata MJ, Ribeiro R, Oliveira MJ, Robalo Cordeiro C, Medeiros R. Renin-Angiotensin System in Lung Tumor and Microenvironment Interactions. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Jun 3;12(6):1457. PMID: 32503281; PMCID: PMC7352181. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Yao T, Wang Z, Liu B, Wu N, Lu M, Shen N. Association between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2023 Jan;128(2):168-176. Epub 2022 Nov 17. PMID: 36396817; PMCID: PMC9670057. [CrossRef]

- Emslander Q, Krey K, Hamad S, Maidl S, Oubraham L, Hesse J, Henrici A, Austen K, Mergner J, Grass V, Pichlmair A. MDM2 Influences ACE2 Stability and SARS-CoV-2 Uptake. Viruses. 2023 Aug 18;15(8):1763. PMID: 37632105; PMCID: PMC10459000. [CrossRef]

- Goyette MA, Duhamel S, Aubert L, Pelletier A, Savage P, Thibault MP, Johnson RM, Carmeliet P, Basik M, Gaboury L, Muller WJ, Park M, Roux PP, Gratton JP, Côté JF. The Receptor Tyrosine Kinase AXL Is Required at Multiple Steps of the Metastatic Cascade during HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Progression. Cell Rep. 2018 May 1;23(5):1476-1490. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.019. Erratum in: Cell Rep. 2023 Dec 26;42(12):113604. [CrossRef]

- Chen IY, Chang SC, Wu HY, Yu TC, Wei WC, Lin S, Chien CL, Chang MF. Upregulation of the chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 via a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike-ACE2 signaling pathway. J Virol. 2010 Aug;84(15):7703-12. Epub 2010 May 19. PMID: 20484496; PMCID: PMC2897593. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki YJ, Nikolaienko SI, Dibrova VA, Dibrova YV, Vasylyk VM, Novikov MY, Shults NV, Gychka SG. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated cell signaling in lung vascular cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2021 Apr;137:106823. Epub 2020 Nov 21. PMID: 33232769; PMCID: PMC7680014. [CrossRef]

- Patra T, Meyer K, Geerling L, Isbell TS, Hoft DF, Brien J, Pinto AK, Ray RB, Ray R. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein promotes IL-6 trans-signaling by activation of angiotensin II receptor signaling in epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2020 Dec 7;16(12):e1009128. PMID: 33284859; PMCID: PMC7746263. [CrossRef]

- Shin HJ, Lee W, Ku KB, Yoon GY, Moon HW, Kim C, Kim MH, Yi YS, Jun S, Kim BT, Oh JW, Siddiqui A, Kim SJ. SARS-CoV-2 aberrantly elevates mitochondrial bioenergetics to induce robust virus propagation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 May 11;9(1):125. PMID: 38734691; PMCID: PMC11088672. [CrossRef]

- McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Lee JT, Chang F, Bertrand FE, Navolanic PM, Terrian DM, Franklin RA, D'Assoro AB, Salisbury JL, Mazzarino MC, Stivala F, Libra M. Roles of the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathways in malignant transformation and drug resistance. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2006;46:249-79. Epub 2006 Jul 18. PMID: 16854453. [CrossRef]

- Guo YJ, Pan WW, Liu SB, Shen ZF, Xu Y, Hu LL. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med. 2020 Mar;19(3):1997-2007. Epub 2020 Jan 15. PMID: 32104259; PMCID: PMC7027163. [CrossRef]

- Solis O, Beccari AR, Iaconis D, Talarico C, Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Nwachukwu JC, Cimini A, Castelli V, Bertini R, Montopoli M, Cocetta V, Borocci S, Prandi IG, Flavahan K, Bahr M, Napiorkowski A, Chillemi G, Ooka M, Yang X, Zhang S, Xia M, Zheng W, Bonaventura J, Pomper MG, Hooper JE, Morales M, Rosenberg AZ, Nettles KW, Jain SK, Allegretti M, Michaelides M. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds and modulates estrogen receptors. Sci Adv. 2022 Dec 2;8(48):eadd4150. [CrossRef]

- Khan I, Hatiboglu MA. Can COVID-19 induce glioma tumorogenesis through binding cell receptors? Med Hypotheses. 2020 Nov;144:110009. Epub 2020 Jun 19. PMID: 32758869; PMCID: PMC7303027. [CrossRef]

- Raimundo L, Ramos H, Loureiro JB, Calheiros J, Saraiva L. BRCA1/P53: Two strengths in cancer chemoprevention. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020 Jan;1873(1):188339. Epub 2020 Jan 7. PMID: 31917206. [CrossRef]

- Salwa A, Ferraresi A, Chinthakindi M, Vallino L, Vidoni C, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. BECN1 and BRCA1 Deficiency Sensitizes Ovarian Cancer to Platinum Therapy and Confers Better Prognosis. Biomedicines. 2021 Feb 18;9(2):207. PMID: 33670664; PMCID: PMC7922320. [CrossRef]

- Kastenhuber ER, Lowe SW. Putting p53 in Context. Cell. 2017; 170:1062–78.

- Shim D, Duan L, Maki CG. P53-regulated autophagy and its impact on drug resistance and cell fate. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021;4(1):85-95. Epub 2021 Mar 19. PMID: 34532654; PMCID: PMC8443158. [CrossRef]

- Ma-Lauer Y, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Hein MY, Müller MA, Deng W, Lei J, Meyer B, Kusov Y, von Brunn B, Bairad DR, Hünten S, Drosten C, Hermeking H, Leonhardt H, Mann M, Hilgenfeld R, von Brunn A. p53 down-regulates SARS coronavirus replication and is targeted by the SARS-unique domain and PLpro via E3 ubiquitin ligase RCHY1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Aug 30;113(35):E5192-201. Epub 2016 Aug 12. PMID: 27519799; PMCID: PMC5024628. [CrossRef]

- Singh N, Bharara Singh A. S2 subunit of SARS-nCoV-2 interacts with tumor suppressor protein p53 and BRCA: an in silico study. Transl Oncol. 2020 Oct;13(10):100814. Epub 2020 Jun 30. PMID: 32619819; PMCID: PMC7324311. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, El-Deiry WS. Transfected SARS-CoV-2 spike DNA for mammalian cell expression inhibits p53 activation of p21(WAF1), TRAIL Death Receptor DR5 and MDM2 proteins in cancer cells and increases cancer cell viability after chemotherapy exposure. Oncotarget. 2024 May 3;15:275-284. PMID: 38709242; PMCID: PMC11073320. [CrossRef]

- Wang HF, Xiang W, Xue BZ, Wang YH, Yi DY, Jiang XB, Zhao HY, Fu P. Cell fusion in cancer hallmarks: Current research status and future indications. Oncol Lett. 2021 Jul;22(1):530. Epub 2021 May 16. PMID: 34055095; PMCID: PMC8138896. [CrossRef]

- Shultes PV, Weaver DT, Tadele DS, Barker-Clarke RJ, Scott JG. Cell-cell fusion in cancer: The next cancer hallmark? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2024 Oct;175:106649. Epub 2024 Aug 24. PMID: 39186970; PMCID: PMC11752790. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Niu Z, Zhang B, Wang C, Yao X, Peng H, Franca DN, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Su Y, Tang M, Jiang X, Ren H, He M, Wang Y, Gao L, Zhao P, Shi H, Chen Z, Wang X, Piacentini M, Bian X, Melino G, Liu L, Huang H, Sun Q. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein dictates syncytium-mediated lymphocyte elimination. Cell Death Differ. 2021 Sep;28(9):2765-2777. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33879858; PMCID: PMC8056997. [CrossRef]

- Rajah MM, Hubert M, Bishop E, Saunders N, Robinot R, Grzelak L, Planas D, Dufloo J, Gellenoncourt S, Bongers A, Zivaljic M, Planchais C, Guivel-Benhassine F, Porrot F, Mouquet H, Chakrabarti LA, Buchrieser J, Schwartz O. SARS-CoV-2 Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants display enhanced Spike-mediated syncytia formation. EMBO J. 2021 Dec 15;40(24):e108944. Epub 2021 Oct 25. PMID: 34601723; PMCID: PMC8646911. [CrossRef]

- Fang Q, He X, Zheng X, Fu Y, Fu T, Luo J, Du Y, Lan J, Yang J, Luo Y, Chen X, Zhou N, Wang Z, Lyu J, Chen L. Verifying AXL and putative proteins as SARS-CoV-2 receptors by DnaE intein-based rapid cell-cell fusion assay. J Med Virol. 2023 Jul;95(7):e28953. PMID: 37461287. [CrossRef]

- Schilling WHK, Mukaka M, Callery JJ, Llewelyn MJ, Cruz CV, Dhorda M, Ngernseng T, Waithira N, Ekkapongpisit M, Watson JA, Chandna A, Nelwan EJ, Hamers RL, Etyang A, Beg MA, Sow S, Yavo W, Allabi AC, Basnyat B, Sharma SK, Amofa-Sekyi M, Yonga P, Adler A, Yuentrakul P, Cope T, Thaipadungpanit J, Rienpradub P, Imwong M, Abdad MY, Blacksell SD, Tarning J, Goudjo FF, Dossou AD, Konaté-Touré A, Assi SB, Ouffoué K, Nasronudin N, Rachman BE, Romadhon PZ, Dewanto DD, Heryana MO, Novi T, Pasaribu AP, Mutiara M, Nasution MPR, Khairunnisa K, Dalimunthe FA, Airlangga E, Fahrezzy A, Subronto Y, Ananda NR, Rahardjani M, Rimainar A, Lucinde RK, Timbwa M, Onyango OE, Agutu C, Akech S, Hamaluba M, Kipyego J, Ngachi O, Haidara FC, Traoré OY, Diarra F, Khanal B, Dahal P, Shrestha S, Rijal S, Kabore Y, Adehossi E, Guindo O, Qamar FN, Kazi AM, Woodrow CJ, Laird S, Cheeba M, Ayles H, Cheah PY, Taylor WRJ, Batty EM, Chotivanich K, Pukrittayakamee S, Phumratanaprapin W, von Seidlein L, Dondorp A, Day NPJ, White NJ; COPCOV Collaborative Group. Evaluation of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for the prevention of COVID-19 (COPCOV): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2024 Sep 12;21(9):e1004428. [CrossRef]

- Tretyakova MS, Subbalakshmi AR, Menyailo ME, Jolly MK, Denisov EV. Tumor Hybrid Cells: Nature and Biological Significance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Feb 15;10:814714. PMID: 35242760; PMCID: PMC8886020. [CrossRef]

- Melzer C, Ohe JV, Hass R. Altered Tumor Plasticity after Different Cancer Cell Fusions with MSC. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Nov 6;21(21):8347. PMID: 33172211; PMCID: PMC7664391. [CrossRef]

- Dikic I, Elazar Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:349–364. [CrossRef]

- Debnath J, Gammoh N, Ryan KM. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023 Aug;24(8):560-575. Epub 2023 Mar 2. PMID: 36864290; PMCID: PMC9980873. [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi A, Esposito A, Girone C, Vallino L, Salwa A, Ghezzi I, Thongchot S, Vidoni C, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. Resveratrol Contrasts LPA-Induced Ovarian Cancer Cell Migration and Platinum Resistance by Rescuing Hedgehog-Mediated Autophagy. Cells. 2021 Nov 17;10(11):3213. PMID: 34831435; PMCID: PMC8625920. [CrossRef]

- Koepke L, et al. Manipulation of autophagy by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Autophagy. 2021;17:2659–2661. [CrossRef]

- Chen D, et al. ORF3a of SARS-CoV-2 promotes lysosomal exocytosis-mediated viral egress. Dev. Cell. 2021;56:3250–3263 e3255. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Hou, P., Ma, W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 suppresses the antiviral innate immune response by degrading MAVS through mitophagy. Cell Mol Immunol 19, 67–78 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Li X, Zhang Z, Wang Z, Gutiérrez-Castrellón P, Shi H. Cell deaths: Involvement in the pathogenesis and intervention therapy of COVID-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Jun 13;7(1):186. PMID: 35697684; PMCID: PMC9189267. [CrossRef]

- Eissa S, Matboli M, Awad N, Kotb Y. Identification and validation of a novel autophagy gene expression signature for human bladder cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2017 Apr;39(4):1010428317698360. PMID: 28381171. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Zhou L, Wang X, Li Y, Liu X, Chen Y, Zhong Z, Chen J. FYCO1 regulates migration, invasion, and invadopodia formation in HeLa cells through CDC42/N-WASP/Arp2/3 signaling pathway. Biochem Cell Biol. 2022 Dec 1;100(6):458-472. Epub 2022 Nov 7. PMID: 36342046. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L., She Z.G., Cheng X., Qin J.J., Zhang X.J., Cai J., Lei F., Wang H., Xie J., Wang W. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31:1068–1077.e3.

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):211-218. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. Epub 2016 Jan 5. Erratum in: Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):287. Erratum in: Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):287. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.004. PMID: 26778478; PMCID: PMC4783224.

- Balamurugan K. HIF-1 at the crossroads of hypoxia, inflammation, and cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016 Mar 1;138(5):1058-66. Epub 2015 Apr 7. PMID: 25784597; PMCID: PMC4573780. [CrossRef]

- Codo AC, Davanzo GG, Monteiro LB, de Souza GF, Muraro SP, Virgilio-da-Silva JV, Prodonoff JS, Carregari VC, de Biagi Junior CAO, Crunfli F, Jimenez Restrepo JL, Vendramini PH, Reis-de-Oliveira G, Bispo Dos Santos K, Toledo-Teixeira DA, Parise PL, Martini MC, Marques RE, Carmo HR, Borin A, Coimbra LD, Boldrini VO, Brunetti NS, Vieira AS, Mansour E, Ulaf RG, Bernardes AF, Nunes TA, Ribeiro LC, Palma AC, Agrela MV, Moretti ML, Sposito AC, Pereira FB, Velloso LA, Vinolo MAR, Damasio A, Proença-Módena JL, Carvalho RF, Mori MA, Martins-de-Souza D, Nakaya HI, Farias AS, Moraes-Vieira PM. Elevated Glucose Levels Favor SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Monocyte Response through a HIF-1α/Glycolysis-Dependent Axis. Cell Metab. 2020 Sep 1;32(3):437-446.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.007. Epub 2020 Jul 17. Erratum in: Cell Metab. 2020 Sep 1;32(3):498-499. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.015. PMID: 32697943; PMCID: PMC7367032.

- Tian M, Liu W, Li X, Zhao P, Shereen MA, Zhu C, Huang S, Liu S, Yu X, Yue M, Pan P, Wang W, Li Y, Chen X, Wu K, Luo Z, Zhang Q, Wu J. HIF-1α promotes SARS-CoV-2 infection and aggravates inflammatory responses to COVID-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Aug 18;6(1):308. PMID: 34408131; PMCID: PMC8371950. [CrossRef]

- Vidoni C, Ferraresi A, Vallino L, Salwa A, Ha JH, Seca C, Garavaglia B, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. Glycolysis Inhibition of Autophagy Drives Malignancy in Ovarian Cancer: Exacerbation by IL-6 and Attenuation by Resveratrol. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 15;24(2):1723. PMID: 36675246; PMCID: PMC9866176. [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi A, Girone C, Maheshwari C, Vallino L, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. Ovarian Cancer Cell-Conditioning Medium Induces Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Phenoconversion through Glucose-Dependent Inhibition of Autophagy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 May 23;25(11):5691. PMID: 38891879; PMCID: PMC11171902. [CrossRef]

- Unterlass JE, Curtin NJ. Warburg and Krebs and related effects in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2019 Sep 27;21:e4. PMID: 31558177. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura H, Takada K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021 Oct;112(10):3945-3952. Epub 2021 Aug 2. PMID: 34286881; PMCID: PMC8486193. [CrossRef]

- Hasan A, Rizvi SF, Parveen S, Pathak N, Nazir A, Mir SS. Crosstalk Between ROS and Autophagy in Tumorigenesis: Understanding the Multifaceted Paradox. Front Oncol. 2022 Mar 10;12:852424. PMID: 35359388; PMCID: PMC8960719. [CrossRef]

- Molnar T, Lehoczki A, Fekete M, Varnai R, Zavori L, Erdo-Bonyar S, Simon D, Berki T, Csecsei P, Ezer E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches. Geroscience. 2024 Apr 26. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38668888. [CrossRef]

- Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. Cell. 2021;184:149–168.

- Zheng M., Gao Y., Wang G., Song G., Liu S., Sun D., Xu Y., Tian Z. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:533–535.

- Iwasaki M, Saito J, Zhao H, Sakamoto A, Hirota K, Ma D. Inflammation triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 augment drives multiple organ failure of severe COVID-19: molecular mechanisms and implications. Inflammation. 2021;44:13–34.

- Li, K., Shi, H., Zhang, B. et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther 6, 362 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Francescangeli F, De Angelis ML, Baiocchi M, Rossi R, Biffoni M, Zeuner A. COVID-19-Induced Modifications in the Tumor Microenvironment: Do They Affect Cancer Reawakening and Metastatic Relapse? Front Oncol. 2020 Oct 26;10:592891. PMID: 33194755; PMCID: PMC7649335. [CrossRef]

- Francescangeli F, De Angelis ML, Zeuner A. COVID-19: a potential driver of immune-mediated breast cancer recurrence? Breast Cancer Res. 2020 Oct 30;22(1):117. PMID: 33126915; PMCID: PMC7598231. [CrossRef]

- Yumoto K, Eber MR, Wang J, Cackowski FC, Decker AM, Lee E, Nobre AR, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Jung Y, Taichman RS. Axl is required for TGF-β2-induced dormancy of prostate cancer cells in the bone marrow. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 7;6:36520. [CrossRef]

- Han J, Bae J, Choi CY, Choi SP, Kang HS, Jo EK, Park J, Lee YS, Moon HS, Park CG, Lee MS, Chun T. Autophagy induced by AXL receptor tyrosine kinase alleviates acute liver injury via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in mice. Autophagy. 2016 Dec;12(12):2326-2343. [CrossRef]

- Copaescu A, et al. The role of IL-6 and other mediators in the cytokine storm associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146:518–534 e511. [CrossRef]

- Thongchot S, Vidoni C, Ferraresi A, Loilome W, Khuntikeo N, Sangkhamanon S, Titapun A, Isidoro C, Namwat N. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Derived IL-6 Determines Unfavorable Prognosis in Cholangiocarcinoma by Affecting Autophagy-Associated Chemoresponse. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr 28;13(9):2134. PMID: 33925189; PMCID: PMC8124468. [CrossRef]

- Chia SB, Johnson BJ, Hu J, Valença-Pereira F, Chadeau-Hyam M, Guntoro F, Montgomery H, Boorgula MP, Sreekanth V, Goodspeed A, Davenport B, De Dominici M, Zaberezhnyy V, Schleicher WE, Gao D, Cadar AN, Petriz-Otaño L, Papanicolaou M, Beheshti A, Baylin SB, Guarnieri JW, Wallace DC, Costello JC, Bartley JM, Morrison TE, Vermeulen R, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Rincon M, DeGregori J. Respiratory viral infections awaken metastatic breast cancer cells in lungs. Nature. 2025 Sep;645(8080):496-506. Epub 2025 Jul 30. PMID: 40739350; PMCID: PMC12422975. [CrossRef]

- Xia X. Detailed Dissection and Critical Evaluation of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jul 3;9(7):734. PMID: 34358150; PMCID: PMC8310186. [CrossRef]

- Riley TP, Chou HT, Hu R, et al. Enhancing the prefusion conformational stability of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein through structure-guided design. Front Immunol. 2021;12:660198.

- Ogata AF, Cheng CA, Desjardins M, Senussi Y, Sherman AC, Powell M, Novack L, Von S, Li X, Baden LR, Walt DR. Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of mRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Mar 1;74(4):715-718. PMID: 34015087; PMCID: PMC8241425. [CrossRef]

- Brogna C, Cristoni S, Marino G, Montano L, Viduto V, Fabrowski M, Lettieri G, Piscopo M. Detection of recombinant Spike protein in the blood of individuals vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2: Possible molecular mechanisms. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2023 Nov;17(6):e2300048. Epub 2023 Aug 31. PMID: 37650258. [CrossRef]

- Castruita JAS, Schneider UV, Mollerup S, Leineweber TD, Weis N, Bukh J, Pedersen MS, Westh H. SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA vaccine sequences circulate in blood up to 28 days after COVID-19 vaccination. APMIS. 2023 Mar;131(3):128-132. Epub 2023 Jan 29. PMID: 36647776; PMCID: PMC10107710. [CrossRef]

- Boros LG, Kyriakopoulos AM, Brogna C, Piscopo M, McCullough PA, Seneff S. Long-lasting, biochemically modified mRNA, and its frameshifted recombinant spike proteins in human tissues and circulation after COVID-19 vaccination. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024 Jun;12(3):e1218. PMID: 38867495; PMCID: PMC11169277. [CrossRef]

- Bansal S, Perincheri S, Fleming T, Poulson C, Tiffany B, Bremner RM, Mohanakumar T. Cutting Edge: Circulating Exosomes with COVID Spike Protein Are Induced by BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) Vaccination prior to Development of Antibodies: A Novel Mechanism for Immune Activation by mRNA Vaccines. J Immunol. 2021 Nov 15;207(10):2405-2410. Epub 2021 Oct 15. PMID: 34654691; PMCID: PMC11073804. [CrossRef]

- Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Naeem U, Moeed A, Atif AR, Asghar MS, Nimri N, Saleem M, Bandyopadhyay D, Krittanawong C, Fadelallah Eljack MM, Tahir MJ, Waqar F. Adverse events following COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: A systematic review of cardiovascular complication, thrombosis, and thrombocytopenia. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023 Mar;11(3):e807. PMID: 36988252; PMCID: PMC10022421. [CrossRef]

- Choi JY, Lee Y, Park NG, Kim MS, Rhie SJ. Serious Safety Signals and Prediction Features Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Using the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Mar 10;17(3):356. PMID: 38543142; PMCID: PMC10974993. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Shen Q, Chang H. Vaccines for COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Immunogenicity, Current Development, and Future Prospects. Front Immunol. 2022 Apr 27;13:843928. PMID: 35572592; PMCID: PMC9092649. [CrossRef]

- Hajjo R, Sabbah DA, Tropsha A. Analyzing the Systems Biology Effects of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines to Assess Their Safety and Putative Side Effects. Pathogens. 2022 Jun 29;11(7):743. PMID: 35889989; PMCID: PMC9320269. [CrossRef]

- Faksova K, Walsh D, Jiang Y, Griffin J, Phillips A, Gentile A, Kwong JC, Macartney K, Naus M, Grange Z, Escolano S, Sepulveda G, Shetty A, Pillsbury A, Sullivan C, Naveed Z, Janjua NZ, Giglio N, Perälä J, Nasreen S, Gidding H, Hovi P, Vo T, Cui F, Deng L, Cullen L, Artama M, Lu H, Clothier HJ, Batty K, Paynter J, Petousis-Harris H, Buttery J, Black S, Hviid A. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. 2024 Apr 2;42(9):2200-2211. Epub 2024 Feb 12. PMID: 38350768. [CrossRef]

- Bruce Yu Y, Taraban MB, Briggs KT. All vials are not the same: Potential role of vaccine quality in vaccine adverse reactions. Vaccine. 2021 Oct 29;39(45):6565-6569. Epub 2021 Oct 6. PMID: 34625289; PMCID: PMC8492451. [CrossRef]

- Tinari S, The EMA covid-19 data leak, and what it tells us about mRNA instability BMJ 2021; 372:n627. (Published 10 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mulroney TE, Pöyry T, Yam-Puc JC, Rust M, Harvey RF, Kalmar L, Horner E, Booth L, Ferreira AP, Stoneley M, Sawarkar R, Mentzer AJ, Lilley KS, Smales CM, von der Haar T, Turtle L, Dunachie S, Klenerman P, Thaventhiran JED, Willis AE. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2024 Jan;625(7993):189-194. Epub 2023 Dec 6. PMID: 38057663; PMCID: PMC10764286. [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Angel M, Roignant JY. Exploring pseudouridylation: dysregulation in disease and therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2024 Jun 3;87:102210. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38833893. [CrossRef]

- Kim KQ, Burgute BD, Tzeng SC, Jing C, Jungers C, Zhang J, Yan LL, Vierstra RD, Djuranovic S, Evans BS, Zaher HS. N1-methylpseudouridine found within COVID-19 mRNA vaccines produces faithful protein products. Cell Rep. 2022 Aug 30;40(9):111300. Epub 2022 Aug 15. PMID: 35988540; PMCID: PMC9376333. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas A, Cowley D, Raszek M, Uversky VN, Redwan EM. Review: N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1Ψ): Friend or foe of cancer? Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 May;267(Pt 1):131427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131427. Epub 2024 Apr 5. Erratum in: Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Jun;270(Pt 2):132447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132447. PMID: 38583833.

- Föhse K, Geckin B, Zoodsma M, Kilic G, Liu Z, Röring RJ, Overheul GJ, van de Maat J, Bulut O, Hoogerwerf JJ, Ten Oever J, Simonetti E, Schaal H, Adams O, Müller L, Ostermann PN, van de Veerdonk FL, Joosten LAB, Haagmans BL, van Crevel R, van Rij RP, GeurtsvanKessel C, de Jonge MI, Li Y, Domínguez-Andrés J, Netea MG. The impact of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine on adaptive and innate immune responses. Clin Immunol. 2023 Oct;255:109762. Epub 2023 Sep 6. PMID: 37673225. [CrossRef]

- Sittplangkoon C, Alameh MG, Weissman D, Lin PJC, Tam YK, Prompetchara E, Palaga T. mRNA vaccine with unmodified uridine induces robust type I interferon-dependent anti-tumor immunity in a melanoma model. Front Immunol. 2022 Oct 14;13:983000. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H, Yu J, Wong CC. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in cancer: molecular mechanisms and downstream targets. Protein Cell. 2025 Jun 20;16(6):391-417. doi: 10.1093/procel/pwae039. Erratum in: Protein Cell. 2024 Nov 08:pwae062. doi: 10.1093/procel/pwae062. PMID: 39126156; PMCID: PMC12187073.

- Jin YY, Liang YP, Pan JQ, Huang WH, Feng YM, Sui WJ, Yu H, Tang XD, Zhu L, Chen JH. RNA editing in response to COVID-19 vaccines: unveiling dynamic epigenetic regulation of host immunity. Front Immunol. 2024 Sep 6;15:1413704. PMID: 39308856; PMCID: PMC11413487. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Kuramitsu Y, Kitagawa T, Baron B, Yoshino S, Maehara S, Maehara Y, Oka M, Nakamura K. Cofilin-phosphatase slingshot-1L (SSH1L) is over-expressed in pancreatic cancer (PC) and contributes to tumor cell migration. Cancer Lett. 2015 May 1;360(2):171-6. Epub 2015 Feb 12. PMID: 25684665. [CrossRef]

- Seneff S, Nigh G, Kyriakopoulos AM, McCullough PA. Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: The role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and MicroRNAs. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022 Jun;164:113008. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436552; PMCID: PMC9012513. [CrossRef]

- Miglietta G, Russo M, Capranico G. G-quadruplex-R-loop interactions and the mechanism of anticancer G-quadruplex binders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Dec 2;48(21):11942-11957. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa944. Erratum in: Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Jan 11;49(1):595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1206. Erratum in: Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Jun 4;49(10):6000-6001. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab483. PMID: 33137181; PMCID: PMC7708042.

- König B, Kirchner JO. Methodological Considerations Regarding the Quantification of DNA Impurities in the COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Comirnaty®. Methods Protoc. 2024 May 8;7(3):41. PMID: 38804335; PMCID: PMC11130870. [CrossRef]

- Kobbe R, Rau C, Schulze-Sturm U, Stahl F, Fonseca-Brito L, Diemert A, Lütgehetmann M, Addo MM, Arck P, Weskamm LM. Delayed Induction of Noninflammatory SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Specific IgG4 Antibodies Detected 1 Year After BNT162b2 Vaccination in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2024 Jul 30;43(12):1200–3. [CrossRef]

- Gao FX, Wu RX, Shen MY, Huang JJ, Li TT, Hu C, Luo FY, Song SY, Mu S, Hao YN, Han XJ, Wang YM, Li L, Li SL, Chen Q, Wang W, Jin AS. Extended SARS-CoV-2 RBD booster vaccination induces humoral and cellular immune tolerance in mice. iScience. 2022 Dec 22;25(12):105479. Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 36338436; PMCID: PMC9625849. [CrossRef]

- Yu T, Wu Y, Liu J, Zhuang Y, Jin X, Wang L. The risk of malignancy in patients with IgG4-related disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022 Jan 5;24(1):14. PMID: 34986892; PMCID: PMC8728936. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Xu Q, Zhao C, Zhu Z, Zhu X, Zhou J, Zhang S, Yang T, Zhang B, Li J, Yan M, Liu R, Ma C, Quan Y, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Geng Y, Chen C, Chen S, Liu D, Chen Y, Tian D, Su M, Chen X, Gu J. An immune evasion mechanism with IgG4 playing an essential role in cancer and implication for immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 Aug;8(2):e000661. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha P, Ghoreyshi ZS, George JT. How modulation of the tumor microenvironment drives cancer immune escape dynamics. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 1;15(1):7308. PMID: 40025156; PMCID: PMC11873109. [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M.J., Lyke, K.E., Kitchin, N. et al. Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586, 589–593 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gandolfo, C.; Anichini, G.; Mugnaini, M.; Bocchia, M.; Terrosi, C.; Sicuranza, A.; Gori Savellini, G.; Gozzetti, A.; Franchi, F.; Cusi, M.G. Overview of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Immune Response Six Months after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, 10, 171.

- Zhang X, Li B, Lan T, Chiari C, Ye X, Wang K, Chen J. The role of interleukin-17 in inflammation-related cancers. Front Immunol. 2025 Jan 21;15:1479505. PMID: 39906741; PMCID: PMC11790576. [CrossRef]