Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

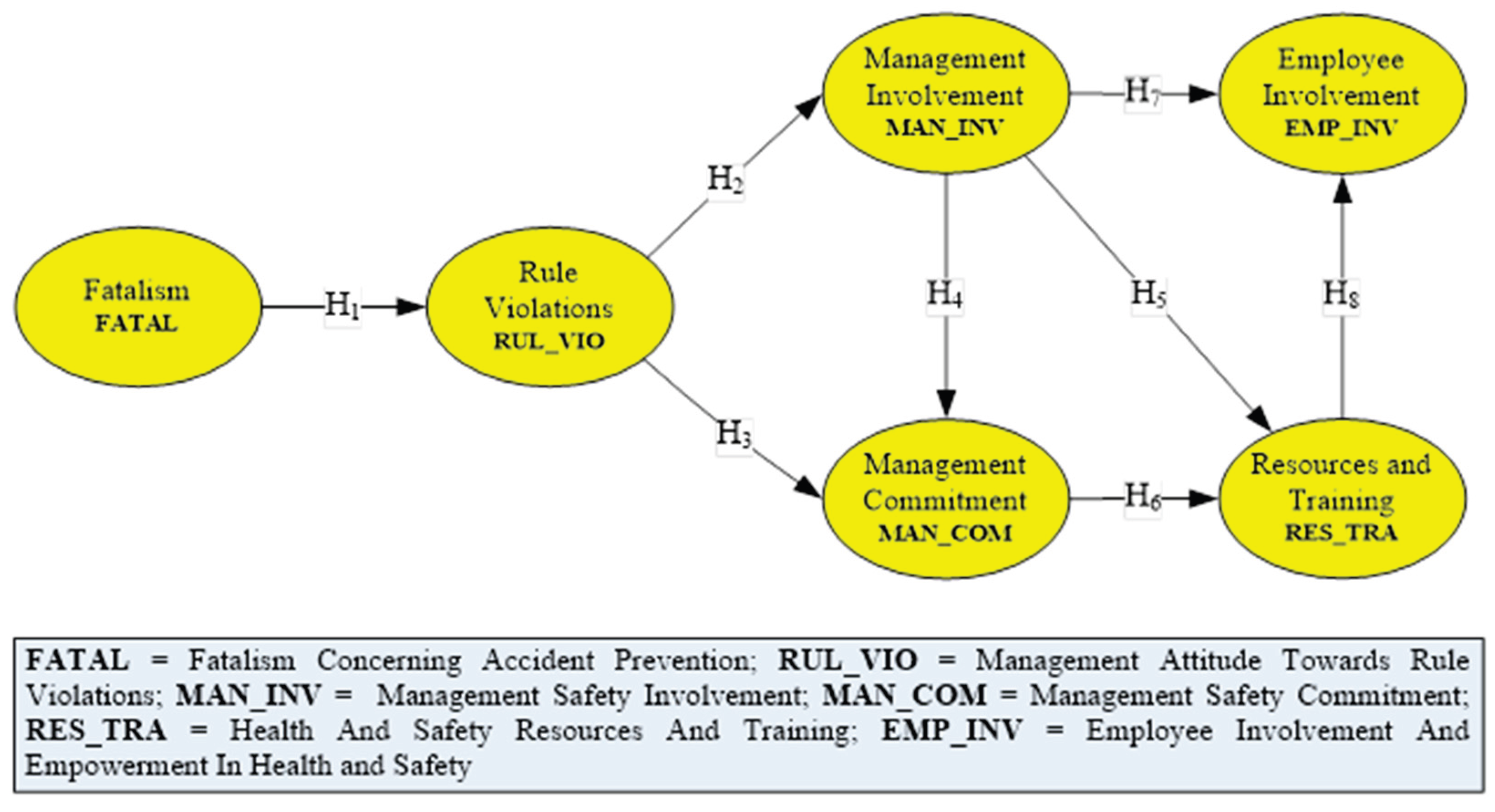

2. Hypothesis Development

Fatalism

Rule Violations

Management Safety Commitment and Safety Involvement

Resource Allocation and Employees' OHS Training

Employee Involvement and Empowerment

Theoretical Framework and Model Design

3. Methods

Sample and Data Collection

Scales

Data Analysis

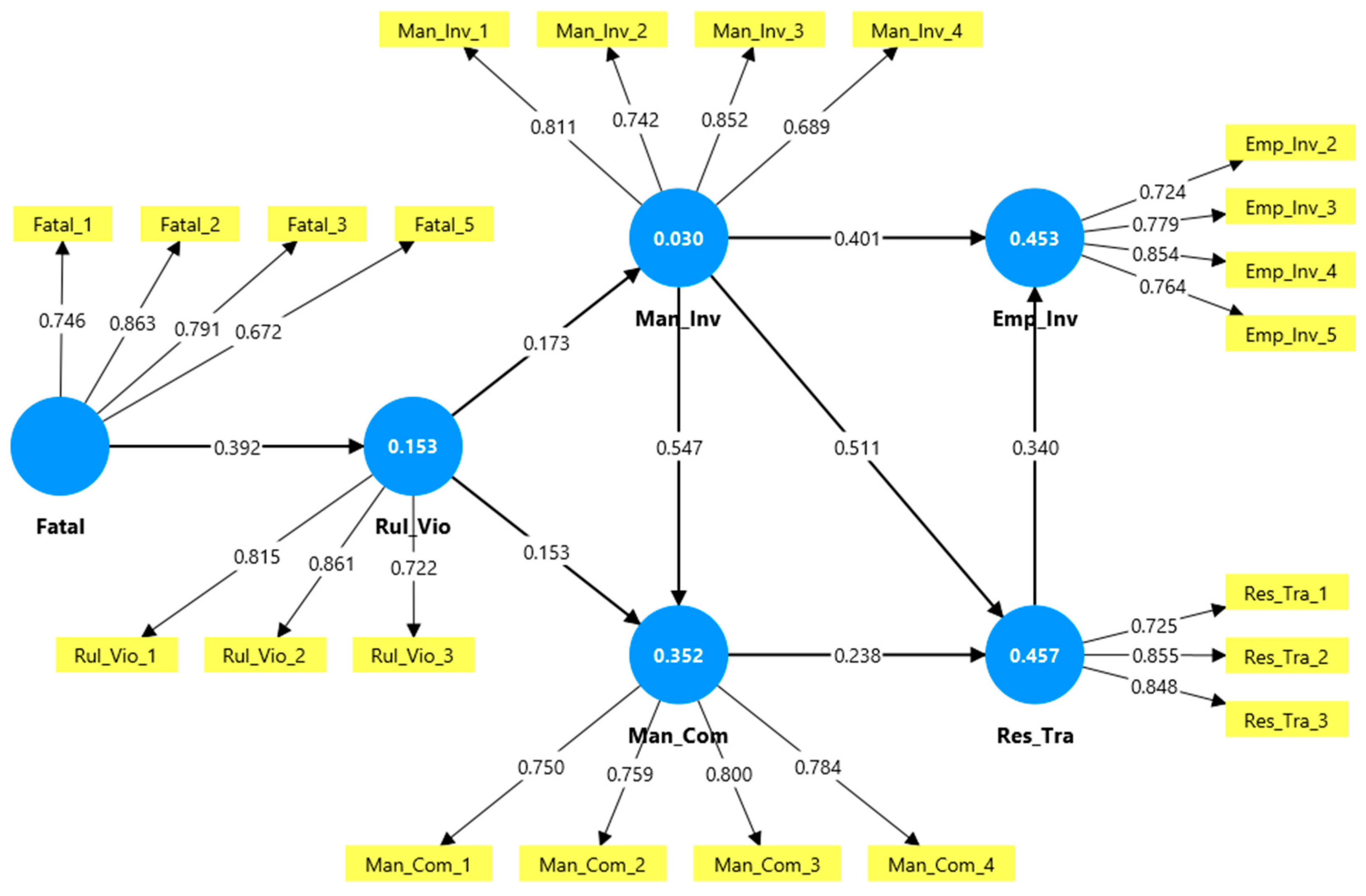

4. Result

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5. Discussion

Practical Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Appendix A

| Codes | Variables |

| FATAL | FATALISM CONCERNING ACCIDENT PREVENTION |

| Fatal_1 | Accidents just happen, there is little one can do to avoid them. |

| Fatal_2 | What happens at work is a matter of chance. |

| Fatal_3 | The use of machines and technical equipment make accidents unavoidable. |

| Fatal_4 | Accident prevention pays off. |

| Fatal_5 | Accidents seem inevitable despite the efforts of the Company to prevent them. |

| RUL_VIO | MANAGEMENT ATTITUDE TOWARDS RULE VIOLATIONS |

| Rul_Vio_1 | Sometimes it is necessary to turn the blind eye to rule violations. |

| Rul_Vio_2 | Sometimes production has to be given priority before safety. |

| Rul_Vio_3 | I have to be more interested in production then safety. |

| MAN_COM | MANAGEMENT SAFETY COMMITMENT |

| Man_Com_1 | I am heavily involved in safety goal setting. |

| Man_Com_2 | I help employees to work more safely. |

| Man_Com_3 | I think a lot on how to prevent accidents. |

| Man_Com_4 | I am heavily committed to safety. |

| MAN_INV | MANAGEMENT SAFETY INVOLVEMENT |

| Man_Inv_1 | I/We take responsibility for H&S by, for example, stopping dangerous work on site, and so on. |

| Man_Inv_2 | I/We encourage discussions on H&S with employees. |

| Man_Inv_3 | I/We regularly visit workplaces to check work conditions or communicate with workers about H&S. |

| Man_Inv_4 | I/We reward workers who make an extra effort to do work in a safe manner. |

| Man_Inv_5 | I/We encourage and support worker participation, commitment and involvement in H&S activities. |

| Man_Inv_6 | I/We regularly conduct toolbox talks with the workers. |

| RES_TRA | HEALTH AND SAFETY RESOURCES AND TRAINING |

| Res_Tra_1 | I/We provide correct tools and equipment to execute construction work. |

| Res_Tra_2 | I/We buy hardhats, gloves, overalls, and so on for workers. |

| Res_Tra_3 | I/We ensure that our workers are properly trained to take care of and use personal protective equipment. |

| EMP_INV | EMPLOYEE INVOLVEMENT AND EMPOWERMENT IN H&S |

| Emp_Inv_1 | Our workers are involved in H&S inspections. |

| Emp_Inv_2 | Our workers help in developing H&S rules and safe-work procedures. |

| Emp_Inv_3 | Our workers are consulted when the H&S plan is compiled. |

| Emp_Inv_4 | Our workers are involved in the production of H&S policy. |

| Emp_Inv_5 | Our workers can refuse to work in potentially unsafe, unhealthy conditions. |

References

- Hoang BH, Mai TH. Policy on work accident, occupational disease insurance in Vietnam. Fin. Manag. Stud. 2023, 6, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Improving Occupational Safety and Health in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Participant Handbook, 2021.

- Nassirou-Sabo H, Toudou-Daouda M. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of occupational risks and diseases among healthcare providers of the Regional Hospital Center of Dosso, Niger. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121231224549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Security Institution. Available online: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Istatistik/Yillik/fcd5e59b-6af9-4d90-a451-ee7500eb1cb4/ (accessed on day month year).

- Ceylan H, Kaplan A, Bekar M. High-risky sectors in terms of work accidents in Turkey. Ulus. Muh. Aras. Gel. Derg. 2022, 14, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal M, Isha ASN, Nordin SM, Al-Mekhlafi ABA. Safety-management practices and the occurrence of occupational accidents: Assessing the mediating role of safety compliance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram M, Arpat B, Ozkan Y. Safety priority, safety rules, safety participation and safety behaviour: The mediating role of safety training. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonom. JOSE 2022, 28, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhan, E. Management commitment and its impact on occupational health and safety improvement: A case of iron, steel and metal manufacturing industries. Int. J. Workpl. Health Manag. 2020, 13, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas R, Swamy DR, Nanjundeswaraswamy TS. Quality management practices in oil and gas industry. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooshaksaraie M, Azadehdel MR. Assessing management involvement in safety issues: The case of the metal products industry in Iran. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 18, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mbebeb, F. E. Occupational fatalism as predictor of risk behavior patterns of workers in high-risk work settings. International Journal of Applied 2020, 10, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajardi, D. , Vagni, M., La Spada, V., & Cubico, S. International cooperation in developing countries: Reducing fatalism and promoting self-efficacy to ensure sustainable cooperation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarotar Ž, Simona MM, Ana MG. Sustainable approach to occupational health and safety care. Journal of chemical health risks 2024, 14, 801–815. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Türkiye. (2024, November 5). Our work on the Sustainable Development Goals in Türkiye. https://turkiye.un.org/en/sdgs.

- Akbolat M, Amarat M, Yildirim Y, Yildirim K, Taş Y. Moderating effect of psychological well-being on the effect of workplace safety climate on job stress. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonom.: JOSE 2022, 28, 2340–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Wu J, Yousaf A, Wang L, Hu K, Plant KL, McIlroy RC, Stanton NA. Exploring the relationship between attitudes, risk perceptions, fatalistic beliefs, and pedestrian behaviors in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, CT. Marginalization, deprivation, and fatalism in the Republic of Ireland: Class and underclass perspectives. Eur Sociol Rev. 1996, 12, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, K. Validity and reliability study of fatality tendency scale. Uluslararası Medeniyet Çalışmaları Dergisi. 2017, 2, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz B, Montes-Peón JM, Vázquez-Ordás CJ. Relation between occupational safety management and firm performance. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen WT, Merrett HC, Huang Y-H, Bria TA, Lin Y-H. Exploring the relationship between safety climate and worker safety behavior on building construction sites in Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttenberg R, Rice C. Assessing the impact of health and safety training: Increased behavioral change and organizational performance. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnama B, Soekiman A. Supervisory behavior that affects worker’s safety behavior in construction project. Budapest Int. Res. Crit. Inst. J. (BIRCI-Journal) 2022, 5, 24682–24694. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Cohen HH, Cohen A. Characteristics of successful safety programs. J. Saf. Res. 1978, 10, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brandhorst S, Kluge A. When the tension is rising: A simulation-based study on the effects of safety incentive programs and behavior-based safety management. Safety 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashi MS, Subramaniam C, Johari J. The effect of management commitment to safety, and safety communication and feedback on safety behavior of nurses: The moderating role of consideration of future safety consequences. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 2565–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz C, Turan AH. The causes of occupational accidents in human resources: The human factors theory and the accident theory perspective. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonom.: JOSE 2023, 29, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi SO, Adegbenro OO, Alaka HA, Oyegoke AS, Manu PA. Addressing behavioural safety concerns on Qatari Mega projects. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102398. [CrossRef]

- Akbolat M, Durmuş A, Ünal Ö, Çakoğlu S. The effect of the fatalistic perception on the perceptions of occupational health and safety practices: The case of a hospital. Work 2022, 71, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfeeq OM, Thiruchelvam SA, Abidin IBZ. Impact of Safety Management Practices on Safety Performance in Workplace Environment: A Case Study in Iraqi Electricity Production Industry. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 13539–13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich HW, Petersen D. Industrial Accident Prevention, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Agumba JN, Pretorius JH, Haupt TC. Health and safety management practices in small and medium enterprises in the South African construction industry. Acta Structilia: J. Physiol. Dev. Sci. 2013, 20, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown RL, Holmes H. The use of a factor-analytic procedure for assessing the validity of an employee safety climate model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1986, 18, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen WT, Merrett HC, Huang Y-H, Lu ST, Sun WC, Li Y. Exploring the multilevel perception of safety climate on Taiwanese construction sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak R, Chattopadhyay A, Maurya P. Accidents and injuries in workers of iron and steel industry in West Bengal, India: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonom.: JOSE 2022, 28, 2533–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Fu J, Hao H, Fu G, Nie F, Zhang W. Root causes of coal mine accidents: Characteristics of safety culture deficiencies based on accident statistics. Process Saf. Environ. Prot.: Trans. Inst. Chem. Eng., Part B 2020, 136, 78–91. [CrossRef]

- Swedler DI, Verma SK, Huang Y-H, Lombardi DA, Chang W-R, Brennan M, Courtney TK. A structural equation modelling approach examining the pathways between safety climate, behaviour performance and workplace slipping. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 72, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, D. A group-level model of safety climate: Testing the effect of group climate on microaccidents in manufacturing jobs. J Appl Psychol. 2000, 85, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, Ö. During COVID-19, which is more effective in work accident prevention behavior of healthcare professionals: Safety awareness or fatalism perception? Work 2020, 67, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapidus, AA. Assessment of the fatal outcome in case of violation of the occupational safety rules in the construction industry. Bez. Truda v Promislennosti 2023, 4, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi WK, Cramer RJ. How regulations undervalue occupational fatalities. Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan A, Nainggolan F, Fauzi A. Influence of management commitment, leadership, employee engagement, and training on safety performance at a manufacturing industry in Batam. J. Bus. Stud. Manag. Rev. 2021, 4, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason RL, Tracy ND, Young JC. Decomposition of T2 for multivariate control chart interpretation. J. Qual. Technol. 1995, 27, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håvold, JI. Safety culture and safety management aboard tankers. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2010, 95, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram M, Burgazoglu H. The relationships between control measures and absenteeism in the context of internal control. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yule S, Flin R, Murdy A. The role of management and safety climate in preventing risk-taking at work. Int. J. Risk Assess. Manag. 2007, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara J, Nordin SM, Isha ASN. Influence of communication determinants on safety commitment in a high-risk workplace: A systematic literature review of four communication dimensions. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1225995. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Z, Subramaniam C, Mohd. Zain ML, Ramalu SS, Mohd Shamsudin F. Management commitment and safety training as antecedent of workers safety behavior. Int. J. Suppl. Chain Oper. Manag. Logist. 2020, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Sun M, Fang W. A Bayesian-based knowledge tracing model for improving safety training outcomes in construction: An adaptive learning framework. Develop. Built Environ. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Nyawera, JX. The study of process health and safety management deficiencies relative to hazardous chemical exposure. (Doctoral dissertation).

- Shabani S, Bachwenkizi J, Mamuya SH, Moen BE. The prevalence of occupational injuries and associated risk factors among workers in iron and steel industries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhashabah E, Summan A, Balkhyour M. Occupational accidents and injuries in construction industry in Jeddah city. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi-Konjin Z, Mortazavi SB, Mahabadi HA, Hajizadeh E. Identification of factors that influence occupational accidents in the petroleum industry: A qualitative approach. Work 2020, 67, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang Q, Mei L, Xu J, Zhou Z. Barriers to safety participation of construction workers in project organization from a stress perspective. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal A, Griffin MA. Safety climate and safety behaviour. Austr. J. Manag. 2002, 27 (Suppl. 1), 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitrano, G. , Micheli, G. J. L., Guglielmi, A., De Merich, D., Pellicci, M., Urso, D., & Ipsen, C. Sustainable occupational safety and health interventions: A study on the factors for an effective design. Safety Science 2023, 166, 106249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, vd. ,, Li, Y., Wu, X., Luo, X., Gao, J., & Yin, W. Impact of safety attitude on the safety behavior of coal miners in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEKA. Denizli için yeni ve stratejik sektör analizleri. [cited 2023 May 21]. Available from: https://www.kalkinmakutuphanesi.gov.tr/assets/upload/dosyalar/denizli-sektor-analiz.pdf.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988.

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Babin BJ, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, 7th ed. 2010.

- Andersen JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, M. Metal sektöründe iş sağlığı ve güvenliği sorunları [Occupational health and safety problems in the metal industry] In Arpat B., Namal MK. (Eds.), Occupational health and safety problems in Turkey: Sectoral evaluations (69–122). Paradigma Akademi Publishing.

- Rundmo T, Hale AR. Managers’ attitudes towards safety and accident prevention. Saf. Sci. 2003, 41, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, MS. A note on the multiplying factors for various χ2 approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M. , Wende, S., and Becker, J.-M. 2024. "SmartPLS 4." Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. https://www.smartpls.com.

- Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handbook of Market Research 2021, 3, 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmoller, JB. Foundations of partial least squares. In: Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares. Physica-Verlag HD; 1989; 63–63. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In: Sinkovics RR, Ghauri PN, editors. New Challenges to International Marketing (Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20). Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2009:277-319. [CrossRef]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus M, Vinzi VE, Chatelin YM, Lauro C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels M, Odekerken-Schröder G, van Oppen C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva JL, da Oliveira F, de Bernardo MH. Fatalism and occupational accidents: A reading of the experience of injured people from Martín-Baró. Estud. Psicol. Campinas 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundmo, T. Safety climate, attitudes and risk perception in Norsk Hydro. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordfjærn T, Nordgård A, Mehdizadeh M. Aberrant driving behaviour among home healthcare workers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2023, 98, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox SJ, Cheyne AJT. Assessing safety culture in offshore environments. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad B, Abbas Adamu A, Akanmu MD. Structural model for the antecedents and consequences of internal crisis communication (ICC) in Malaysia oil and gas high-risk industry. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 215824402210798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbang A, Prasad DR, Azri MH. The perspective of leadership and management commitment in process safety management. Indian Chem. Eng. 2023, 65, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh IS, Okwudu A, Uduak EJ. Top Management Commitment and Sales Force Performance of Beverage Manufacturing Companies in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2022, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya S, Tarigan Z, Siagian H. The role of top management commitment, employee empowerment and total quality management in production waste management and enhancing firm performance. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 11, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agumba JN, Haupt TC. The influence of health and safety practices on health and safety performance outcomes in small and medium enterprise projects in the South African construction industry. J. South. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2018, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas R, Swamy DR, Nanjundeswaraswamy TS. Quality management practices in oil and gas industry. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aca Z, Akdamar E. Decent work in Turkey: Field research on its context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Manag. Econ. Res. 2022, 20, 271–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, Zega YA. Influence of occupational health safety (OHS) culture, commitment management, OHS training on OHS performance in oil & gas contractors company in Batam Island. J. Bus. Stud. Manag. Rev. 2021, 4, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, M. Safety training and competence, employee participation and involvement, employee satisfaction, and safety performance: An empirical study on Occupational Health and Safety Management System implementing manufacturing firms. Alphanumeric J. 2019, 7, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi FJ, de Beer P, Haafkens JA. Occupational risk perception and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE): A study among informal automobile artisans in Osun State, Nigeria. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402199458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyi S, Eyi İ. Nursing students’ occupational health and safety problems in surgical clinical practice. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal M, Bin Isha A, Sabir AA, Nordin SM. Management commitment to safety and safety training: Mediating role of safety compliance for occupational accidents A study on oil and gas industry of Malaysia. Acad. J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo PN, Wium J. Health and safety management systems within construction contractor organizations: Case study of South Africa. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 05020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet J, Lecours A, Nastasia I. Experiences in the return-to-work process of workers having suffered occupational injuries in small and medium size enterprises. Work 2023, 74, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu SX, Chen HZ, Mei Q, Zhou Y, Edmund NNK. Impact analysis of behavior of front-line managers on employee safety behavior by integrating interpretive structural modeling and Bayesian network. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonom.: JOSE 2022, 28, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia N, Xie Q, Hu X, Wang X, Meng H. A dual perspective on risk perception and its effect on safety behavior: A moderated mediation model of safety motivation, and supervisor’s and coworkers’ safety climate. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 134, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal A, Griffin MA. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J Appl Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann DA, Morgeson FP, Gerras SJ. Climate as a moderator of the relationship between leader-member exchange and content specific citizenship: Safety climate as an exemplar. J Appl Psychol. 2003, 88, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian MS, Bradley JC, Wallace JC, Burke MJ. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J Appl Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinodkumar MN, Bhasi M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid Anal Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J Appl Psychol. 1980, 65, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Thirty years of safety climate research: Reflections and future directions. Accid Anal Prev. 2010, 42, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | N | % | Marital status | N | % | |||

| Male | 345 | 88,2 | Married | 292 | 74,7 | |||

| Female | 46 | 11,8 | Single | 99 | 25,3 | |||

| Total | 391 | 100 | Total | 391 | 100 | |||

| Age | N | % | Educational level | N | % | |||

| 18-30 | 115 | 29,4 | Primary school graduate | 31 | 7,9 | |||

| 31-40 | 158 | 40,4 | Secondary school graduate | 23 | 5,9 | |||

| 41-50 | 100 | 25,6 | High school graduate | 79 | 20,2 | |||

| 51 years old and above | 18 | 4,6 | University graduate | 258 | 66,0 | |||

| Total | 391 | 100 | Total | 391 | 100 | |||

| Administrator Groups | ||||||||

| POSITION | Entry-level managers |

Mid-level Managers |

Upper-level Managers |

|||||

| Supervisor in Charge | Engineer | Manager/Assistant Manager | ||||||

| Foreman | Technical Specialist | Employer | ||||||

| Specialist/Assistant Specialist | Team leader | Employer Representative (Person responsible for the entire management of a workplace ) | ||||||

| Chargehand | (Planning-production) Individual Responsible | |||||||

| 181 (46,3%) | 134 (34,3%) | 76 (19,4%) | ||||||

| 391 – 100% | ||||||||

| Latent variable | Variable | Convergent validity | Internal consistency reliability | ||||

| Loadings | Indicator reliability | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | CR | ||

| > 0.700 | > 0.500 | > 0.500 | 0.700 – 0.900 | > 0.700 | > 0.700 | ||

| FATAL | Fatal_1 | 0.783 | 0.612 | 0.705 | 0.791 | 0.822 | 0.877 |

| Fatal_2 | 0.905 | 0.819 | |||||

| Fatal_3 | 0.827 | 0.684 | |||||

| MAN_COM | Man_Com_1 | 0.744 | 0.553 | 0.598 | 0.776 | 0.776 | 0.856 |

| Man_Com_2 | 0.763 | 0.583 | |||||

| Man_Com_3 | 0.800 | 0.639 | |||||

| Man_Com_4 | 0.786 | 0.617 | |||||

| MAN_INV | Man_Inv_1 | 0.834 | 0.696 | 0.683 | 0.767 | 0.776 | 0.866 |

| Man_Inv_2 | 0.771 | 0.594 | |||||

| Man_Inv_3 | 0.871 | 0.758 | |||||

| RES_TRA | Res_Tra_1 | 0.725 | 0.525 | 0.659 | 0.739 | 0.751 | 0.852 |

| Res_Tra_2 | 0.853 | 0.728 | |||||

| Res_Tra_3 | 0.850 | 0.723 | |||||

| RUL_VIO | Rul_Vio_1 | 0.799 | 0.639 | 0.642 | 0.720 | 0.717 | 0.843 |

| Rul_Vio_2 | 0.854 | 0.730 | |||||

| Rul_Vio_3 | 0.746 | 0.557 | |||||

| EMP_INV | Emp_Inv_2 | 0.728 | 0.529 | 0.611 | 0.787 | 0.793 | 0.862 |

| Emp_Inv_3 | 0.782 | 0.612 | |||||

| Emp_Inv_4 | 0.851 | 0.724 | |||||

| Emp_Inv_5 | 0.760 | 0.578 | |||||

| EMP_INV | FATAL | MAN_COM | MAN_INV | RES_TRA | RUL_VIO | |

| EMP_INV | ||||||

| FATAL | 0.078 | |||||

| MAN_COM | 0.579 | 0.149 | ||||

| MAN_INV | 0.758 | 0.245 | 0.730 | |||

| RES_TRA | 0.788 | 0.152 | 0.697 | 0.838 | ||

| RUL_VIO | 0.299 | 0.458 | 0.339 | 0.284 | 0.295 |

| Link | R² | ƒ2 |

| FATAL ➔ RUL_VIO | 0.127 | 0.146** |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV | 0.046 | 0.049* |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_COM | 0.340 | 0.028* |

| MAN_INV ➔ MAN_COM | 0.417*** | |

| MAN_INV ➔ RES_TRA | 0.451 | 0.307*** |

| MAN_COM ➔ RES_TRA | 0.076* | |

| MAN_INV ➔ EMP_INV | 0.434 | 0.130** |

| RES_TRA ➔ EMP_INV | 0.146** |

|

Hypoteses No. |

Link | Path Coefficient (β) | Standard Deviation | t Statistics | Confidence Intervals (95% Bias Corrected) | Results |

| H1 | FATAL ➔ RUL_VIO | 0.356 | 0.054 | 6.551** | [0.236;0.454] | SP |

| H2 | RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV | 0.215 | 0.052 | 4.152** | [0.110;0.312] | SP |

| H3 | RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_COM | 0.139 | 0.046 | 3.000* | [0.048;0.230] | S |

| H4 | MAN_INV ➔ MAN_COM | 0.537 | 0.041 | 13.072** | [0.452;0.612] | SP |

| H5 | MAN_INV ➔ RES_TRA | 0.498 | 0.050 | 9.885** | [0.396;0.591] | SP |

| H6 | MAN_INV ➔ EMP_INV | 0.353 | 0.060 | 5.919** | [0.237;0.473] | SP |

| H7 | MAN_COM ➔ RES_TRA | 0.249 | 0.053 | 4.672** | [0.148;0.357] | SP |

| H8 | RES_TRA ➔ EMP_INV | 0.374 | 0.066 | 5.687** | [0.242;0.499] | SP |

| Link | Path Coefficient (β) | Standard Deviation | t Statistics | Confidence Intervals (95% Bias Corrected) | Results |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| FATAL ➔ RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV | 0,077 | 0,025 | 3,042* | [0,032;0,129] | S |

| FATAL ➔ RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_COM | 0,050 | 0,019 | 2,572* | [0,016;0,090] | S |

| FATAL➔RUL_VIO➔MAN_INV➔RES_TRA | 0,038 | 0,013 | 2,849* | [0,016;0,068] | S |

| FATAL➔RUL_VIO➔MAN_COM➔RES_TRA | 0,012 | 0,006 | 1,977* | [0,004;0,028] | S |

| FATAL➔RUL_VIO➔MAN_INV➔ EMP_INV | 0,027 | 0,010 | 2,636* | [0,011;0,051] | S |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV ➔ RES_TRA | 0,107 | 0,029 | 3,737** | [0,054;0,165] | SP |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_COM ➔ RES_TRA | 0,035 | 0,016 | 2,181* | [0,011;0,073] | P |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV ➔ EMP_INV | 0,076 | 0,023 | 3,302* | [0,036;0,124] | P |

| MAN_COM ➔ RES_TRA ➔ EMP_INV | 0,093 | 0,026 | 3,610** | [0,052;0,154] | SP |

| Total effects | |||||

| FATAL ➔ EMP_INV | 0,050 | 0,016 | 3,155* | [0,025;0,086] | S |

| FATAL ➔ MAN_COM | 0,091 | 0,027 | 3,372* | [0,046;0,151] | S |

| FATAL ➔ MAN_INV | 0,077 | 0,025 | 3,042* | [0,036;0,135] | S |

| FATAL ➔ RES_TRA | 0,061 | 0,019 | 3,239* | [0,030;0,104] | S |

| FATAL ➔ RUL_VIO | 0,356 | 0,054 | 6,551** | [0,255;0,465] | SP |

| MAN_COM ➔ EMP_INV | 0,093 | 0,026 | 3,610** | [0,050;0,151] | SP |

| MAN_COM ➔ RES_TRA | 0,249 | 0,053 | 4,672** | [0,150;0,359] | SP |

| MAN_INV ➔ EMP_INV | 0,589 | 0,034 | 17,320** | [0,523;0,655] | SP |

| MAN_INV ➔ MAN_COM | 0,537 | 0,041 | 13,072** | [0,457;0,617] | SP |

| MAN_INV ➔ RES_TRA | 0,632 | 0,037 | 17,280** | [0,554;0,698] | SP |

| RES_TRA ➔ EMP_INV | 0,374 | 0,066 | 5,687** | [0,244;0,502] | SP |

| RUL_VIO ➔ EMP_INV | 0,140 | 0,032 | 4,336** | [0,080;0,205] | SP |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_COM | 0,255 | 0,055 | 4,609** | [0,149;0,363] | SP |

| RUL_VIO ➔ MAN_INV | 0,215 | 0,052 | 4,152** | [0,118;0,321] | SP |

| RUL_VIO ➔ RES_TRA | 0,171 | 0,038 | 4,491** | [0,101;0,249] | SP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).