Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

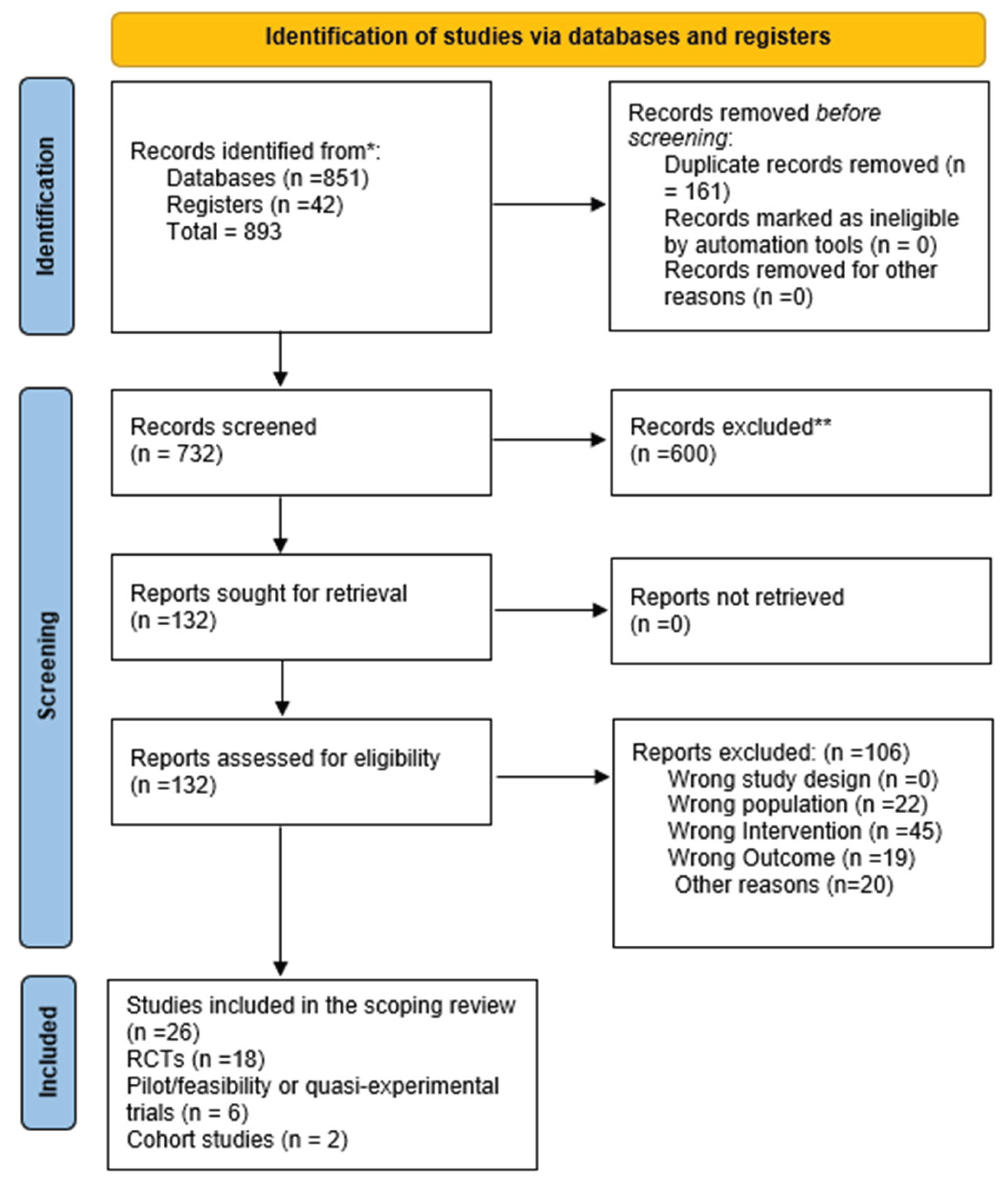

2. Materials and Methods

Study Selection Procedures

Literature Search: Administration and Update

| Criterion Type | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Human participants of any age (adults, older adults, clinical populations such as T2D, PCOS, obese). | Animal studies; pediatric-only studies (<18 y); studies in elite athletes only. |

| Intervention | Exercise snacks, activity breaks, interruptions of prolonged sitting, stair climbing snacks, home-based resistance or Tai Chi snacking. | Conventional structured exercise programs not classified as “exercise snacks”; pharmacological or dietary-only interventions. |

| Comparison | Control groups with uninterrupted sitting, usual care, or alternative exercise modes (e.g., MICT). | Studies without a comparator or lacking baseline/control conditions. |

| Outcomes | Metabolic (glucose, insulin, triglycerides), vascular (BP, FMD, CBF), fitness (VO₂ peak, CRF), cognition, fatigue, functional outcomes (SPPB, sit-to-stand). | Outcomes unrelated to exercise/health (e.g., biomechanical modelling, unrelated psychology outcomes). |

| Study Design | Randomised controlled trials, randomised crossover trials, pilot RCTs, feasibility/acceptability studies, and cohort studies with relevant sedentary/exercise snack exposure. | Narrative reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and non-peer-reviewed grey literature. |

| Publication Characteristics | Peer-reviewed articles published in English between 2012–2025. | Non-English language papers, theses, dissertations, and book chapters. |

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

2.4. Summary Measures

2.5. Synthesis of Results

2.6. Publication Bias

2.7. Additional Analyses

3. Results

| Study (Author, Year) | Country | Population Type | Sample Size (n) | Age (Mean ± SD / Range) | Sex (% Male/Female) | Health Status / Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Allison et al., 2017) [3] | Canada | Inactive young women | 31 | 18-30 y | 0 / 100 | Healthy, sedentary |

| (Bergouignan, Latouche, et al., 2016) [9] | Australia/France | Overweight/obese adults | 19 | 35-55 y | ~50/50 | Overweight/obese |

| (Bergouignan, Legget, et al., 2016) [20] | USA | Adults, sedentary workers | 22 | 30-55 y | 45 / 55 | Sedentary, healthy |

| (Carter et al., 2018) [17] | UK | Healthy young adults | 18 | 20-40 y | 50 / 50 | Healthy |

| (Zhou et al., 2025) [12] | China | Sedentary obese adults | 60 | 25-45 y | 40 / 60 | Obese, otherwise healthy |

| (Dempsey, Larsen, et al., 2016) [7] | Australia | Adults with type 2 diabetes | 24 | 45-70 y | 60 / 40 | T2D |

| (Dempsey, Sacre, et al., 2016) [8] | Australia | Adults with type 2 diabetes | 24 | 45-70 y | 60 / 40 | T2D |

| (Brakenridge et al., 2022) [36] | Australia | Adults with T2D | Protocol only | – | – | T2D |

| (Diaz et al., 2017) [1] | USA (NHANES) | Community-dwelling adults | 7985 | ≥45 y | ~50 / 50 | General population |

| (Dunstan et al., 2012) [2] | Australia | Overweight/obese adults | 19 | 45-65 y | 55 / 45 | Overweight/obese |

| (Francois & Little, 2015) [11] | Canada | Adults with T2D | Review (no n) | – | – | T2D |

| (Fyfe et al., 2022) [22] | Australia | Older adults | 40 | 65-80 y | 40 / 60 | Community-dwelling, inactive |

| (Jenkins et al., 2019) [26] | Canada | Young sedentary adults | 24 | 20-30 y | 50 / 50 | Healthy sedentary |

| (Larsen et al., 2014) [14] | Australia | Overweight/obese adults | 19 | 45-65 y | 60 / 40 | Overweight/obese |

| (Liang et al., 2022) [23] | UK/Taiwan | Older adults (COVID) | 52 | 65-85 y | 45 / 55 | Self-isolating older adults |

| (Liang et al., 2023) [24] | UK/Taiwan | Older adults (survey) | 200 | 65-85 y | 45 / 55 | Low/high-function older adults |

| (Logan et al., 2025) [27] | Australia | Adults with T2D | 25 | 50-70 y | 60 / 40 | T2D |

| (Mues et al., 2025) [21] | Germany | Middle-aged office workers | 48 | 40-55 y | 50 / 50 | Sedentary, cognitively healthy |

| (Peddie et al., 2013) [6] | New Zealand | Healthy normal-weight adults | 70 | 20-35 y | ~50 / 50 | Healthy |

| (Thosar et al., 2015) [15] | USA | Young men | 12 | 18-30 y | 100 / 0 | Healthy |

| (Taylor et al., 2021) [18] | Australia | Women with PCOS | 28 | 25-40 y | 0 / 100 | PCOS |

| (Restaino et al., 2015) [16] | USA | Healthy adults | 15 | 18-30 y | 55 / 45 | Healthy |

| (Western et al., 2023) [25] | UK | Pre-frail older adults | 34 | 70-85 y | 35 / 65 | Pre-frail, memory clinic |

| (Wennberg et al., 2016) [19] | Sweden | Overweight adults | 25 | 40-60 y | 50 / 50 | Overweight, sedentary |

| (Francois et al., 2014) [10] | New Zealand | Adults with insulin resistance | 12 | 40-65 y | 60 / 40 | Insulin resistant |

| (Yin et al., 2024) [13] | China | Inactive adults | 50 | 20-40 y | 50 / 50 | Healthy sedentary |

| Author & Year | Aim | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome | Study Design | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Allison et al., 2017) [3] | Examine whether brief, intense stair climbing improves cardiorespiratory fitness | Inactive young women | 3à 20-s stair climbing bouts/day for 6 weeks | Control (no training) | Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2peak) | Randomized trial | ↑VO2 peak vs control |

| (Bergouignan, Latouche, et al., 2016) [9] | Assess molecular pathways from frequent sedentary interruptions | Overweight/obese adults | Frequent walking breaks | Prolonged sitting | Glucose uptake pathways | Randomized crossover | Improved insulin-stimulated glucose uptake |

| (Bergouignan, Legget, et al., 2016) [20] | Evaluate psychological and behavioral responses to sitting interruptions | Adults | 5-minute walking every hour | Uninterrupted sitting | Energy, mood, cravings, cognition | Randomized crossover | ↑ energy, ↓ cravings, improved mood |

| (Carter et al., 2018) [17] | Investigate impact of walking breaks on cerebral blood flow | Healthy adults | 5-min light walking every 30 min | Prolonged sitting | Cerebral blood flow (CBF) | Randomized crossover | Walking breaks prevented decline in CBF |

| (Zhou et al., 2025) [12] | Effect of exercise snacks on body composition and metabolomics | Sedentary obese adults | Exercise snacks intervention | Uninterrupted sitting | Body composition, metabolomics | Randomized controlled trial | Improved composition and plasma metabolomics |

| (Dempsey, Larsen, et al., 2016) [7] | Interrupting sitting with walking/resistance in T2D | Adults with T2D | 3-min walking or resistance breaks every 30 min | Uninterrupted sitting | Glucose, insulin, triglycerides | Randomized crossover | ↓ postprandial glucose, insulin, TGs |

| (Dempsey, Sacre, et al., 2016) [8] | Impact of activity breaks on BP and noradrenaline | Adults with T2D | 3-min light walking or resistance every 30 min | Uninterrupted sitting | Blood pressure, noradrenaline | Randomized crossover | ↓ BP, ↓ noradrenaline |

| (Brakenridge et al., 2022) [36] | Protocol for OPTIMISE trial | Adults with T2D | Sitting less, moving more program | Usual care | Metabolic and brain health | RCT protocol | Planned outcomes, not reported |

| (Diaz et al., 2017) [1] | Association between sedentary patterns and mortality | US adults (NHANES) | Model replacing sedentary with activity | Prolonged sedentary | All-cause mortality | Cohort study | More breaks ↓ mortality risk |

| (Dunstan et al., 2012) [2] | Effect of breaking sitting on glucose/insulin | Overweight adults | 2-min light/mod walking every 20 min | Uninterrupted sitting | Postprandial glucose, insulin | Randomized crossover | ↠“glucose & insulin AUC |

| (Francois & Little, 2015) [11] | Evaluate HIIT safety and effectiveness in T2D | Adults with T2D | High-intensity interval training (exercise snacks) | Usual activity | Glycemic control, safety | Review/clinical evidence | HIIT safe and effective |

| (Fyfe et al., 2022) [22] | Feasibility of resistance exercise snacking in older adults | Community-dwelling older adults | Home-based resistance snacks (pragmatic RCT) | Control | Physical function, feasibility | Pilot RCT | Feasible and acceptable |

| (Jenkins et al., 2019) [26] | Stair climbing exercise snacks and fitness | Young adults | 3à /day vigorous stair climbing for 6 weeks | Control | Cardiorespiratory fitness | Randomized trial | ↠‘VO2 peak |

| (Larsen et al., 2014) [14] | Breaking up sitting and blood pressure | Overweight/obese adults | Walking breaks | Uninterrupted sitting | Resting blood pressure | Randomized crossover | ↓ resting BP |

| (Liang et al., 2022) [23] | Feasibility of home-based exercise/Tai Chi snacks | Older adults (COVID isolation) | Remotely delivered exercise & Tai Chi snacks | None | Feasibility, acceptability | Pilot trial | Well accepted |

| (Liang et al., 2023) [24] | Acceptability of exercise/Tai Chi snacks | UK & Taiwanese older adults | Home-based exercise and Tai Chi snacks | None | Acceptability | Cross-cultural survey | High acceptability in both groups |

| (Logan et al., 2025) [27] | Interrupting sitting effects on incretin hormones | Adults with T2D | Light walking breaks | Prolonged sitting | GIP, GLP-1 responses | Randomized crossover | ↓ GIP, GLP-1 unchanged |

| (Mues et al., 2025) [21] | Workplace exercise snacks and cognition | Sedentary middle-aged adults | Short exercise snacks during workday | Usual work routine | Cognitive performance | Randomized pilot trial | ↑ acute cognition, feasible |

| (Peddie et al., 2013) [6] | Compare sitting breaks vs single exercise bout | Healthy adults | 1-2 min walking every 30 min | Single 30-min bout; uninterrupted sitting | Postprandial glucose, insulin | Randomized crossover | Breaks better at ↓ glucose, insulin |

| (Thosar et al., 2015) [15] | Effect of sitting and breaks on endothelial function | Young adults | Light walking breaks during sitting | Prolonged sitting | Endothelial function (FMD) | Randomized crossover | Breaks prevented decline in FMD |

| (Taylor et al., 2021) [18] | Effect of sitting breaks in PCOS women | Women with PCOS | Interrupting sitting with activity | Prolonged sitting | Endothelial function | Randomized crossover | Improved endothelial function |

| (Restaino et al., 2015) [16] | Vascular effects of prolonged sitting | Healthy adults | Leg movement vs no movement | Prolonged sitting | Micro/macrovascular dilator function | Experimental crossover | ↓ vascular function with sitting |

| (Western et al., 2023) [25] | 28-day exercise snacking in pre-frail older adults | Pre-frail memory clinic patients | Daily home-based resistance snacks | Usual routine | Physical function (SPPB, sit-to-stand) | Pilot pre-post | Improved lower-limb function |

| (Wennberg et al., 2016) [19] | Breaking sitting and fatigue/cognition | Overweight adults | Light walking breaks | Prolonged sitting | Fatigue, cognition | Pilot crossover | ↓ fatigue, mixed cognition effects |

| (Francois et al., 2014) [10] | Pre-meal exercise snacks and glycemic control | Adults with insulin resistance | Short HIIT snacks before meals | Continuous exercise; sitting | Postprandial glucose, insulin | Randomized crossover | Snacks more effective than continuous exercise |

| (Yin et al., 2024) [13] | Compare exercise snacks vs MICT on CRF/fat oxidation | Inactive adults | Exercise snacks for 6 weeks | MICT training | CRF, fat oxidation | Randomized controlled trial | Snacks improved CRF, not maximal fat oxidation |

| Study | Randomization | Deviations | Missing Data |

Measurement | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Allison et al., 2017) [3] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Bergouignan, Latouche, et al., 2016) [9] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| (Bergouignan, Legget, et al., 2016) [20] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Carter et al., 2018) [17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Zhou et al., 2025) [12] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low |

| (Dempsey, Larsen, et al., 2016) [7] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Dempsey, Sacre, et al., 2016) [8] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Diaz et al., 2017) [1] | N/A (Cohort) | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Dunstan et al., 2012) [2] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Fyfe et al., 2022) [22] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| (Jenkins et al., 2019) [26] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Larsen et al., 2014) [14] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Liang et al., 2022) [23] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low |

| (Liang et al., 2023) [24] | N/A (Survey) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low |

| (Logan et al., 2025) [27] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Mues et al., 2025) [21] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| (Peddie et al., 2013) [6] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Thosar et al., 2015) [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Taylor et al., 2021) [18] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Restaino et al., 2015) [16] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Western et al., 2023) [25] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| (Wennberg et al., 2016) [19] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| (Francois et al., 2014) [10] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| (Yin et al., 2024) [13] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Outcome | No. of Studies | Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic control (glucose/insulin) | 12 | RCTs & crossovers | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | 5 | RCTs | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Vascular health (BP, FMD, CBF) | 7 | RCTs | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Cognitive outcomes | 4 | Pilot RCTs | Some concerns | High | Moderate | High | Some concerns | Low |

| Older adult functional outcomes | 5 | RCTs & pilots | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Study (Author, Year) | Outcome(s) Measured | Measurement Protocol / Instrument Used |

|---|---|---|

| (Allison et al., 2017) [3] | Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO₂peak) | Graded treadmill exercise test with indirect calorimetry |

| (Bergouignan, Latouche, et al., 2016) [9] | Glucose uptake pathways | Muscle biopsies; insulin- and contraction-stimulated glucose uptake assays; molecular pathway analysis |

| (Bergouignan, Legget, et al., 2016) [20] | Energy, mood, cravings, cognition | Self-reported visual analogue scales; validated questionnaires |

| (Carter et al., 2018) [17] | Cerebral blood flow (CBF) | Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (middle cerebral artery velocity) |

| (Zhou et al., 2025) [12] | Body composition, metabolomics | DXA for composition; plasma metabolomic profiling via LC-MS |

| (Dempsey, Larsen, et al., 2016) [7] | Postprandial glucose, insulin, TGs | Capillary/venous blood sampling every 30–60 min for 7 h; enzymatic assays |

| (Dempsey, Sacre, et al., 2016) [8] | Blood pressure, noradrenaline | Automated oscillometric BP; plasma noradrenaline via HPLC |

| (Brakenridge et al., 2022) [36] | Planned metabolic & brain outcomes | Protocol – planned HbA1c, fasting glucose, MRI brain scans, cognitive battery |

| (Diaz et al., 2017) [1] | Mortality, sedentary patterns | Accelerometer-based sedentary assessment; mortality from NHANES linkage |

| (Dunstan et al., 2012) [2] | Postprandial glucose, insulin | Venous blood samples during 5-h meal test; AUC calculations |

| (Francois & Little, 2015) [11] | Glycemic control, safety | Narrative/clinical evidence (varied methods across HIIT trials) |

| (Fyfe et al., 2022) [22] | Physical function, feasibility | 30-s chair stand, timed up-and-go, 6-min walk test; feasibility via adherence logs & surveys |

| (Jenkins et al., 2019) [26] | Cardiorespiratory fitness | VO₂peak test via incremental cycle ergometer |

| (Larsen et al., 2014) [14] | Resting blood pressure | Automated BP monitor (average of repeated seated measures) |

| (Liang et al., 2022) [23] | Physical function, acceptability | 30-s sit-to-stand, balance tests; surveys on feasibility/acceptability |

| (Liang et al., 2023) [24] | Acceptability | Semi-structured surveys/interviews |

| (Logan et al., 2025) [27] | Incretin hormones (GIP, GLP-1) | Venous blood sampling post-meal with ELISA-based assays |

| (Mues et al., 2025) [21] | Cognitive performance | Computerised cognitive tests (working memory, reaction time, Stroop task) |

| (Peddie et al., 2013) [6] | Postprandial glucose, insulin | Capillary blood glucose; insulin ELISA during standardised meal test |

| (Thosar et al., 2015) [15] | Endothelial function (FMD) | Brachial artery FMD by high-resolution ultrasound |

| (Taylor et al., 2021) [18] | Endothelial function in PCOS | FMD of brachial artery; reproductive hormone profiling |

| (Restaino et al., 2015) [16] | Micro/macrovascular dilation | Ultrasound-based FMD; microvascular function via local heating/shear stimulus |

| (Western et al., 2023) [25] | Physical function | Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB); 5-times sit-to-stand |

| (Wennberg et al., 2016) [19] | Fatigue, cognition | Self-reported fatigue scales; computerized attention/working memory tests |

| (Francois et al., 2014) [10] | Glycemic control (pre-meal snacks) | OGTT-like protocol; repeated postprandial blood draws (glucose, insulin) |

| (Yin et al., 2024) [13] | CRF, fat oxidation | Incremental treadmill VO₂peak test; indirect calorimetry for fat oxidation rates |

4. Discussion

Exercise Snacks and Metabolic Health

Vascular and Cardiovascular Outcomes

Cognitive and Psychological Outcomes

Functional Outcomes in Older Adults

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Cohort Evidence and Mortality Associations

Mechanistic Insights

Feasibility and Acceptability

Synthesis Across Domains

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz KM, Howard VJ, Hutto B, Colabianchi N, Vena JE, Safford, M.M.; et al. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in U.S. Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A National Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017, 167, 465–475. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, Healy GN, Cerin E, Hamilton, M.T.; et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35, 976–983. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, M.K.; Baglole, J.H.; Martin, B.J.; Macinnis, M.J.; Gurd, B.J.; Gibala, M.J. Brief Intense Stair Climbing Improves Cardiorespiratory Fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, E.M.; Nairn, L.N.; Skelly, L.E.; Little, J.P.; Gibala, M.J. Do stair climbing exercise “snacks” improve cardiorespiratory fitness? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019, 44, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, I.J.; Perkin, O.J.; McGuigan, P.M.; Thompson, D.; Western, M.J. Feasibility and Acceptability of Home-Based Exercise Snacking and Tai Chi Snacking Delivered Remotely to Self-Isolating Older Adults During COVID-19. J Aging Phys Act. 2022, 30, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, M.C.; Bone, J.L.; Rehrer, N.J.; Skeaff, C.M.; Gray, A.R.; Perry, T.L. Breaking prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glycemia in healthy, normal-weight adults: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013, 98, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey PC, Larsen RN, Sethi P, Sacre JW, Straznicky NE, Cohen, N.D.; et al. Benefits for Type 2 Diabetes of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting With Brief Bouts of Light Walking or Simple Resistance Activities. Diabetes Care. 2016, 39, 964–972. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey PC, Sacre JW, Larsen RN, Straznicky NE, Sethi P, Cohen, N.D.; et al. Interrupting prolonged sitting with brief bouts of light walking or simple resistance activities reduces resting blood pressure and plasma noradrenaline in type 2 diabetes. J Hypertens. 2016, 34, 2376–2382. [CrossRef]

- Bergouignan A, Latouche C, Heywood S, Grace MS, Reddy-Luthmoodoo M, Natoli, A.K.; et al. Frequent interruptions of sedentary time modulates contraction- and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake pathways in muscle: Ancillary analysis from randomized clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 32044.

- Francois ME, Baldi JC, Manning PJ, Lucas SJE, Hawley JA, Williams, M.J.A.; et al. “Exercise snacks” before meals: a novel strategy to improve glycaemic control in individuals with insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2014, 57, 1437–1445. [CrossRef]

- Francois, M.E.; Little, J.P. Effectiveness and safety of high-intensity interval training in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2015, 28, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Yu, W. Effects of breaking up prolonged sitting via exercise snacks intervention on the body composition and plasma metabolomics of sedentary obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Endocr J. 2025, 72, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin M, Deng S, Chen Z, Zhang B, Zheng H, Bai, M.; et al. Exercise snacks are a time-efficient alternative to moderate-intensity continuous training for improving cardiorespiratory fitness but not maximal fat oxidation in inactive adults: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2024, 49, 920–932.

- Larsen, R.N.; Kingwell, B.A.; Sethi, P.; Cerin, E.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D.W. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces resting blood pressure in overweight/obese adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014, 24, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thosar, S.S.; Bielko, S.L.; Mather, K.J.; Johnston, J.D.; Wallace, J.P. Effect of prolonged sitting and breaks in sitting time on endothelial function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restaino, R.M.; Holwerda, S.W.; Credeur, D.P.; Fadel, P.J.; Padilla, J. Impact of prolonged sitting on lower and upper limb micro- and macrovascular dilator function. Exp Physiol. 2015, 100, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.E.; Draijer, R.; Holder, S.M.; Brown, L.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Hopkins, N.D. Regular walking breaks prevent the decline in cerebral blood flow associated with prolonged sitting. J Appl Physiol 2018, 125, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor FC, Dunstan DW, Fletcher E, Townsend MK, Larsen RN, Rickards, K.; et al. Interrupting Prolonged Sitting and Endothelial Function in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 479–486. [CrossRef]

- Wennberg P, Boraxbekk CJ, Wheeler M, Howard B, Dempsey PC, Lambert, G.; et al. Acute effects of breaking up prolonged sitting on fatigue and cognition: a pilot study. BMJ Open. 2016, 6, e009630. [CrossRef]

- Bergouignan A, Legget KT, De Jong N, Kealey E, Nikolovski J, Groppel, J.L.; et al. Effect of frequent interruptions of prolonged sitting on self-perceived levels of energy, mood, food cravings and cognitive function. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016, 13, 113. [CrossRef]

- Mues, J.P.; Flohr, S.; Kurpiers, N. The Influence of Workplace-Integrated Exercise Snacks on Cognitive Performance in Sedentary Middle-Aged Adults-A Randomized Pilot Study. Sports 2025, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, J.J.; Dalla Via, J.; Jansons, P.; Scott, D.; Daly, R.M. Feasibility and acceptability of a remotely delivered, home-based, pragmatic resistance “exercise snacking” intervention in community-dwelling older adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, I.J.; Perkin, O.J.; McGuigan, P.M.; Thompson, D.; Western, M.J. Feasibility and Acceptability of Home-Based Exercise Snacking and Tai Chi Snacking Delivered Remotely to Self-Isolating Older Adults During COVID-19. J Aging Phys Act. 2022, 30, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, I.J.; Francombe-Webb, J.; McGuigan, P.M.; Perkin, O.J.; Thompson, D.; Western, M.J. The acceptability of homebased exercise snacking and Tai-chi snacking amongst high and low function UK and Taiwanese older adults. Front Aging. 2023, 4, 1180939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Western, M.J.; Welsh, T.; Keen, K.; Bishop, V.; Perkin, O.J. Exercise snacking to improve physical function in pre-frail older adult memory clinic patients: a 28-day pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.M.; Nairn, L.N.; Skelly, L.E.; Little, J.P.; Gibala, M.J. Do stair climbing exercise “snacks” improve cardiorespiratory fitness? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019, 44, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan BK, Larsen R, Sacre JW, Cohen ND, Lambert GW, Wheeler, M.J.; et al. Interrupting prolonged sitting reduces postprandial GIP but not GLP-1 responses in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ.; et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119536604.

- Brunton, G.; Stansfield, C.; Thomas, J. Finding relevant studies. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. 2012, 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron, I.; et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019, 366, l4898.

- Wells G, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson, J.; et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. In 2014 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale-(NOS)-for-Assessing-the-Wells-Wells/c293fb316b6176154c3fdbb8340a107d9c8c82bf.

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2009 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470743386.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ.; et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. p. 241–84. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119536604.ch10.

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakenridge CJ, Gardiner PA, Grigg RV, Winkler EAH, Fjeldsoe BS, Schaumberg, M.A.; et al. Sitting less and moving more for improved metabolic and brain health in type 2 diabetes: ‘OPTIMISE your health’ trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22, 929.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).