Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

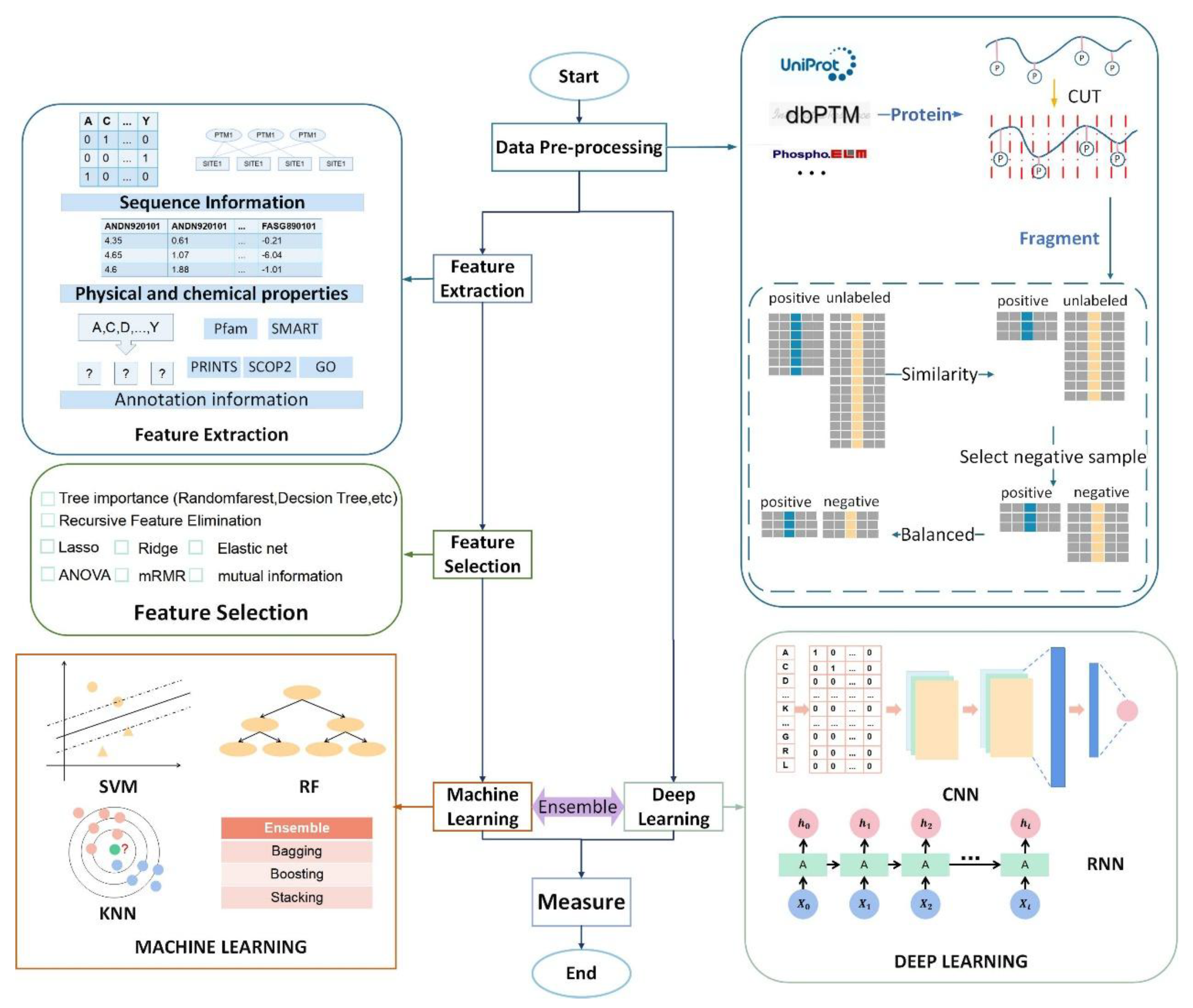

2. Datasets and Data Pre-Processing

2.1. Dataset

2.1.1. Uniport

2.1.2. dbPTM

2.1.3. CPLM 4.0

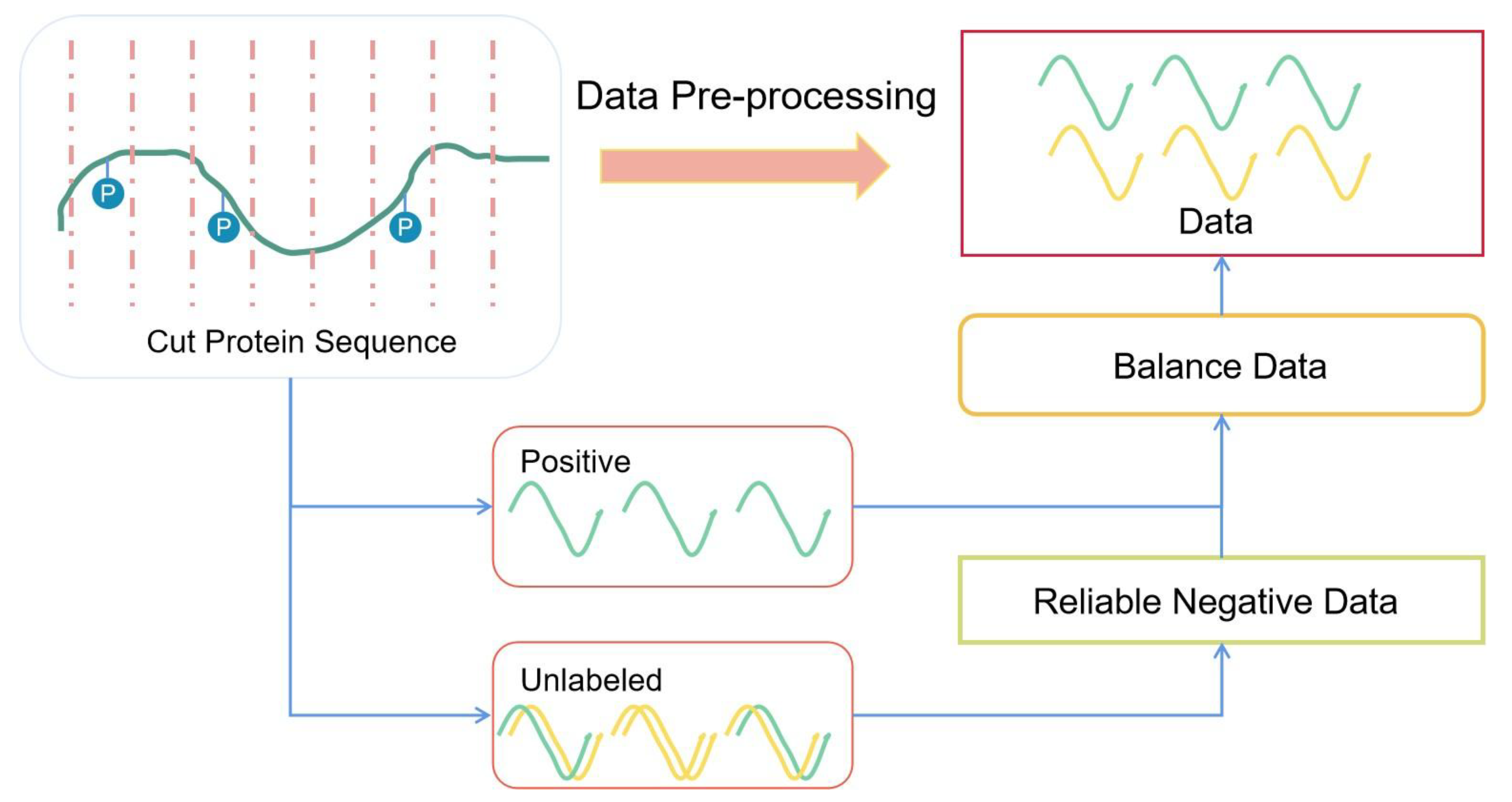

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

2.2.1. Sequence Slice

2.2.2. Sequence Redundancy

2.2.3. Selected Reliable Negative Sequences

2.2.4. Balanced Dataset

2.2.5. Data Splitting

3. Feature Engineering

3.1. Feature Extraction

3.1.1. Physicochemical Properties

3.1.2. Annotation Information

3.1.3. Network-Based Feature

3.2. Feature Reduction

4. Classifiers

4.1. Machine Learning Classifier

4.2. Based on Deep Learning

5. Measurement

6. Summary of Predictors

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Data Limitations

7.2. Interpretability

7.3. Interplay Between Modification Sites and Processes

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTM | Post-translational modifications |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine learning |

References

- Shrestha, P, Kandel, J, Tayara, H et al. DL-SPhos: Prediction of serine phosphorylation sites using transformer language model. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 169:107925.

- Liang, J-Z, Li, D-H, Xiao, Y-C et al. LAFEM: A Scoring Model to Evaluate Functional Landscape of Lysine Acetylome. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2024, 23(1):100700.

- Chang, KW, Gao, D, Yan, JD et al. Critical Roles of Protein Arginine Methylation in the Central Nervous System. Molecular Neurobiology 2023, 60(10):6060-6091.

- Dai, XF, Zhang, TX, Hua, D. Ubiquitination and SUMOylation: protein homeostasis control over cancer. Epigenomics 2022, 14(1):43-58.

- Masbuchin, AN, Rohman, MS, Liu, PY. Role of Glycosylation in Vascular Calcification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(18):9829.

- Wohlschlager, T, Scheffler, K, Forstenlehner, IC et al. Native mass spectrometry combined with enzymatic dissection unravels glycoform heterogeneity of biopharmaceuticals. Nature Communications 2018, 9:1713.

- Park, H, Song, WY, Cha, H et al. Development of an optimized sample preparation method for quantification of free fatty acids in food using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1):5947.

- Slade, DJ, Subramanian, V, Fuhrmann, J et al. Chemical and Biological Methods to Detect Post-Translational Modifications of Arginine. Biopolymers 2014, 101(2):133-143.

- Li, FY, Dong, SY, Leier, A et al. Positive-unlabeled learning in bioinformatics and computational biology: a brief review. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23(1):bbab461.

- Qiao, YH, Zhu, XL, Gong, HP. BERT-Kcr: prediction of lysine crotonylation sites by a transfer learning method with pre-trained BERT models. Bioinformatics 2022, 38(3):648-654.

- Lussi, YC, Magrane, M, Martin, MJ et al. Searching and Navigating UniProt Databases. Current protocols 2023, 3(3):e700.

- Bairoch, A, Bougueleret, L, Altairac, S et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36:D190-D195.

- Li, ZY, Li, SF, Luo, MQ et al. dbPTM in 2022: an updated database for exploring regulatory networks and functional associations of protein post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50(D1):D471-D479.

- Lee, TY, Huang, HD, Hung, JH et al. dbPTM: an information repository of protein post-translational modification. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34:D622-D627.

- Zhang, WZ, Tan, XD, Lin, SF et al. CPLM 4.0: an updated database with rich annotations for protein lysine modifications. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50(D1):D451-D459.

- Liu, ZX, Cao, J, Gao, XJ et al. CPLA 1.0: an integrated database of protein lysine acetylation. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39:D1029-D1034.

- Liu, ZX, Wang, YB, Gao, TS et al. CPLM: a database of protein lysine modifications. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42(D1):D531-D536.

- Xu, HD, Zhou, JQ, Lin, SF et al. PLMD: An updated data resource of protein lysine modifications. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2017, 44(5):243-250.

- Hornbeck, PV, Kornhauser, JM, Tkachev, S et al. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40(D1):D261-D270.

- Yu, K, Wang, Y, Zheng, YQ et al. qPTM: an updated database for PTM dynamics in human, mouse, rat and yeast. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51(D1):D479-D487.

- Tung, CW. PupDB: a database of pupylated proteins. Bmc Bioinformatics 2012, 13:40.

- Duan, GY, Li, X, Köhn, M. The human DEPhOsphorylation database DEPOD: a 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43(D1):D531-D535.

- Ma, JF, Li, YX, Hou, CY et al. O-GlcNAcAtlas: A database of experimentally identified O-GlcNAc sites and proteins. Glycobiology 2021, 31(7):719-723.

- Dinkel, H, Chica, C, Via, A et al. Phospho.ELM: a database of phosphorylation sites-update 2011. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39:D261-D267.

- Rao, RSP, Zhang, N, Xu, D et al. CarbonylDB: a curated data-resource of protein carbonylation sites. Bioinformatics 2018, 34(14):2518-2520.

- Ramasamy, P, Turan, D, Tichshenko, N et al. Scop3P: A Comprehensive Resource of Human Phosphosites within Their Full Context. Journal of Proteome Research 2020, 19(8):3478-3486.

- Hansen, JE, Lund, O, Rapacki, K et al. O-GLYCBASE version 2.0: A revised database of O-glycosylated proteins. Nucleic Acids Research 1997, 25(1):278-282.

- Lee, TY, Chen, YJ, Lu, CT et al. dbSNO: a database of cysteine S-nitrosylation. Bioinformatics 2012, 28(17):2293-2295.

- Li, ZY, Chen, SY, Jhong, JH et al. UbiNet 2.0: a verified, classified, annotated and updated database of E3 ubiquitin ligase-substrate interactions. Database-the Journal of Biological Databases and Curation 2021:baab010.

- Wang, X, Li, Y, He, MQ et al. UbiBrowser 2.0: a comprehensive resource for proteome-wide known and predicted ubiquitin ligase/deubiquitinase-substrate interactions in eukaryotic species. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50(D1):D719-D728.

- Durek, P, Schmidt, R, Heazlewood, JL et al. PhosPhAt: the Arabidopsis thaliana phosphorylation site database. An update. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38:D828-D834.

- Lai, FL, Gao, F. Auto-Kla: a novel web server to discriminate lysine lactylation sites using automated machine learning. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24(2):bbad070.

- Wei, LY, Xing, PW, Shi, GT et al. Fast Prediction of Protein Methylation Sites Using a Sequence-Based Feature Selection Technique. Ieee-Acm Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2019, 16(4):1264-1273.

- Li, ZT, Fang, JY, Wang, SN et al. Adapt-Kcr: a novel deep learning framework for accurate prediction of lysine crotonylation sites based on learning embedding features and attention architecture. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23(2):bbac037.

- Sua, JN, Lim, SY, Yulius, MH et al. Incorporating convolutional neural networks and sequence graph transform for identifying multilabel protein Lysine PTM sites. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2020, 206:104171.

- Lyu, XR, Li, SH, Jiang, CY et al. DeepCSO: A Deep-Learning Network Approach to Predicting Cysteine S-Sulphenylation Sites. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8:594587.

- Auliah, FN, Nilamyani, AN, Shoombuatong, W et al. PUP-Fuse: Prediction of Protein Pupylation Sites by Integrating Multiple Sequence Representations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(4):2120.

- Bao, WZ, Yuan, CA, Zhang, YH et al. Mutli-Features Prediction of Protein Translational Modification Sites. Ieee-Acm Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2018, 15(5):1453-1460.

- Khalili, E, Ramazi, S, Ghanati, F et al. Predicting protein phosphorylation sites in soybean using interpretable deep tabular learning network. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23(2):bbac015.

- Li, WZ, Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2006, 22(13):1658-1659.

- Li, WZ, Jaroszewski, L, Godzik, A. Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 2001, 17(3):282-283.

- Li, WZ, Jaroszewski, L, Godzik, A. Tolerating some redundancy significantly speeds up clustering of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 2002, 18(1):77-82.

- Huang, Y, Niu, BF, Gao, Y et al. CD-HIT Suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 2010, 26(5):680-682.

- Yu, B, Yu, ZM, Chen, C et al. DNNAce: Prediction of prokaryote lysine acetylation sites through deep neural networks with multi-information fusion. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2020, 200:103999.

- Arafat, ME, Ahmad, MW, Shovan, SM et al. Accurately Predicting Glutarylation Sites Using Sequential Bi-Peptide-Based Evolutionary Features. Genes 2020, 11(9):1023.

- Jamal, S, Ali, W, Nagpal, P et al. Predicting phosphorylation sites using machine learning by integrating the sequence, structure, and functional information of proteins. Journal of Translational Medicine 2021, 19(1):218.

- Bekker, J, Davis, J. Learning from positive and unlabeled data: a survey. Machine Learning 2020, 109(4):719-760.

- Jiang, M, Cao, JZ. Positive-Unlabeled Learning for Pupylation Sites Prediction. Biomed Research International 2016, 2016:4525786.

- Gao, Y, Hao, WL, Gu, J et al. PredPhos: an ensemble framework for structure-based prediction of phosphorylation sites. Journal of Biological Research-Thessaloniki 2016, 23:S12.

- Chen, Z, Pang, M, Zhao, ZX et al. Feature selection may improve deep neural networks for the bioinformatics problems. Bioinformatics 2020, 36(5):1542-1552.

- Ning, Q, Ma, ZQ, Zhao, XW et al. SSKM_Succ: A Novel Succinylation Sites Prediction Method Incorporating K-Means Clustering With a New Semi-Supervised Learning Algorithm. Ieee-Acm Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2022, 19(1):643-652.

- Chawla, NV, Bowyer, KW, Hall, LO et al. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002, 16:321-357.

- He, HB, Bai, Y, Garcia, EA et al: ADASYN: Adaptive Synthetic Sampling Approach for Imbalanced Learning. In: International Joint Conference on Neural Networks: Jun 01-08 2008; Hong Kong, PEOPLES R CHINA. 2008: 1322-1328.

- Lu, Y, Cheung, YM, Tang, YY: Hybrid Sampling with Bagging for Class Imbalance Learning. In: 20th Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (PAKDD): Apr 19-22 2016; Univ Auckland, Auckland, NEW ZEALAND. 2016: 14-26.

- Seiffert, C, Khoshgoftaar, TM, Van Hulse, J. Hybrid sampling for imbalanced data. Integrated Computer-Aided Engineering 2009, 16(3):193-210.

- Dongdong, L, Ziqiu, C, Bolu, W et al. Entropy-based hybrid sampling ensemble learning for imbalanced data. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2021, 36(7):3039-3067.

- Wang, MH, Cui, XW, Yu, B et al. SulSite-GTB: identification of protein S-sulfenylation sites by fusing multiple feature information and gradient tree boosting. Neural Computing & Applications 2020, 32(17):13843-13862.

- Wang, MH, Song, LL, Zhang, YQ et al. Malsite-Deep: Prediction of protein malonylation sites through deep learning and multi-information fusion based on NearMiss-2 strategy. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 240:108191.

- Wilson, DL. Asymptotic Properties of Nearest Neighbor Rules Using Edited Data. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1972, SMC-2(3):408-421.

- Ijaz, MF, Attique, M, Son, Y. Data-Driven Cervical Cancer Prediction Model with Outlier Detection and Over-Sampling Methods. Sensors 2020, 20(10):2809.

- Mbunge, E, Millham, RC, Sibiya, MN et al: Implementation of ensemble machine learning classifiers to predict diarrhoea with SMOTEENN, SMOTE, and SMOTETomek class imbalance approaches. In: Conference on Information-Communications-Technology-and-Society (ICTAS): Mar 08-09 2023; Durban Univ Technol, Durban, SOUTH AFRICA. 2023: 90-95.

- Khan, SH, Hayat, M, Bennamoun, M et al. Cost-Sensitive Learning of Deep Feature Representations From Imbalanced Data. Ieee Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2018, 29(8):3573-3587.

- Yuan, ZW, Zhao, P: An Improved Ensemble Learning for Imbalanced Data Classification. In: IEEE 8th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC): May 24-26 2019; Chongqing, PEOPLES R CHINA. 2019: 408-411.

- Hu, XS, Zhang, RJ, Ieee: Clustering-based Subset Ensemble Learning Method for Imbalanced Data. In: International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC): Jul 14-17 2013; Tianjin, PEOPLES R CHINA. 2013: 35-39.

- Hayashi, T, Fujita, H. One-class ensemble classifier for data imbalance problems. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52(15):17073-17089.

- Dou, LJ, Yang, FL, Xu, L et al. A comprehensive review of the imbalance classification of protein post-translational modifications. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22(5):bbab089.

- Branco, P, Torgo, L, Ribeiro, RP. A Survey of Predictive Modeling on Im balanced Domains. Acm Computing Surveys 2016, 49(2):31.

- Kaur, H, Pannu, HS, Malhi, AK. A Systematic Review on Imbalanced Data Challenges in Machine Learning: Applications and Solutions. Acm Computing Surveys 2019, 52(4):79.

- Wang, M, Yang, J, Liu, GP et al. Weighted-support vector machines for predicting membrane protein types based on pseudo-amino acid composition. Protein Engineering Design & Selection 2004, 17(6):509-516.

- Lin, C-F, Wang, S-D. Fuzzy support vector machines. IEEE transactions on neural networks 2002, 13(2):464-471.

- Ju, Z, Wang, SY. Prediction of lysine formylation sites using the composition of k-spaced amino acid pairs via Chou’s 5-steps rule and general pseudo components. Genomics 2020, 112(1):859-866.

- Zhou, ZH, Liu, XY. Training cost-sensitive neural networks with methods addressing the class imbalance problem. Ieee Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2006, 18(1):63-77.

- Seiffert, C, Khoshgoftaar, TM, Van Hulse, J et al. RUSBoost: A Hybrid Approach to Alleviating Class Imbalance. Ieee Transactions on Systems Man and Cybernetics Part a-Systems and Humans 2010, 40(1):185-197.

- Jia, CZ, Zuo, Y, Zou, Q. O-GlcNAcPRED-II: an integrated classification algorithm for identifying O-GlcNAcylation sites based on fuzzy undersampling and a K-means PCA oversampling technique. Bioinformatics 2018, 34(12):2029-2036.

- Wu, XY, Srihari, R, Zheng, ZH: Document representation for one-class SVM. In: Machine Learning: Ecml 2004, Proceedings. Edited by Boulicaut JF, Esposito F, Giannoti F, Pedreschi D, vol. 3201; 2004: 489-500.

- Islam, S, Mugdha, SB, Dipta, SR et al. MethEvo: an accurate evolutionary information-based methylation site predictor. Neural Computing & Applications 2022, 36(1):201-212.

- Huang, KY, Hung, FY, Kao, HJ et al. iDPGK: characterization and identification of lysine phosphoglycerylation sites based on sequence-based features. Bmc Bioinformatics 2020, 21(1):568.

- Sahu, SS, Panda, G. A novel feature representation method based on Chou’s pseudo amino acid composition for protein structural class prediction. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2010, 34(5-6):320-327.

- Huang, KY, Hsu, JBK, Lee, TY. Characterization and Identification of Lysine Succinylation Sites based on Deep Learning Method. Scientific Reports 2019, 9:16175.

- Jiang, PR, Ning, WS, Shi, YS et al. FSL-Kla: A few-shot learning-based multi-feature hybrid system for lactylation site prediction. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19:4497-4509.

- Suo, SB, Qiu, JD, Shi, SP et al. Position-Specific Analysis and Prediction for Protein Lysine Acetylation Based on Multiple Features. Plos One 2012, 7(11):e49108.

- Shen, HB, Yang, J, Chou, KC. Fuzzy KNN for predicting membrane protein types from pseudo-amino acid composition. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2006, 240(1):9-13.

- Gao, JJ, Thelen, JJ, Dunker, AK et al. Musite, a Tool for Global Prediction of General and Kinase-specific Phosphorylation Sites. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2010, 9(12):2586-2600.

- Shen, JW, Zhang, J, Luo, XM et al. Predicting protein-protein interactions based only on sequences information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007, 104(11):4337-4341.

- Saravanan, V, Gautham, N. Harnessing Computational Biology for Exact Linear B-Cell Epitope Prediction: A Novel Amino Acid Composition-Based Feature Descriptor. Omics-a Journal of Integrative Biology 2015, 19(10):648-658.

- Park, KJ, Kanehisa, M. Prediction of protein subcellular locations by support vector machines using compositions of amino acids and amino acid pairs. Bioinformatics 2003, 19(13):1656-1663.

- Keskin, O, Bahar, I, Badretdinov, AY et al. Empirical solvent-mediated potentials hold for both intra-molecular and inter-molecular inter-residue interactions. Protein Science 1998, 7(12):2578-2586.

- Liang, SD, Grishin, NV. Effective scoring function for protein sequence design. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics 2004, 54(2):271-281.

- Chan, CH, Liang, HK, Hsiao, NW et al. Relationship between local structural entropy and protein thermostability. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics 2004, 57(4):684-691.

- Tang, YR, Chen, YZ, Canchaya, CA et al. GANNPhos: a new phosphorylation site predictor based on a genetic algorithm integrated neural network. Protein Engineering Design & Selection 2007, 20(8):405-412.

- Xu, Y, Wang, XB, Wang, YC et al. Prediction of posttranslational modification sites from amino acid sequences with kernel methods. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2014, 344:78-87.

- Lee, TY, Lin, ZQ, Hsieh, SJ et al. Exploiting maximal dependence decomposition to identify conserved motifs from a group of aligned signal sequences. Bioinformatics 2011, 27(13):1780-1787.

- Kawashima, S, Kanehisa, M. AAindex: Amino acid index database. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28(1):374-374.

- Li, FY, Li, C, Wang, MJ et al. GlycoMine: a machine learning-based approach for predicting N-, C- and O-linked glycosylation in the human proteome. Bioinformatics 2015, 31(9):1411-1419.

- Gong, WM, Zhou, DH, Ren, YL et al. PepCyber:PPEP:: a database of human protein-protein interactions mediated by phosphoprotein-binding domains. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36:D679-D683.

- Wagner, M, Adamczak, R, Porollo, A et al. Linear regression models for solvent accessibility prediction in proteins. Journal of Computational Biology 2005, 12(3):355-369.

- Tomii, K, Kanehisa, M. Analysis of amino acid indices and mutation matrices for sequence comparison and structure prediction of proteins. Protein Engineering 1996, 9(1):27-36.

- Dubchak, I, Muchnik, I, Holbrook, SR et al. PREDICTION OF PROTEIN-FOLDING CLASS USING GLOBAL DESCRIPTION OF AMINO-ACID-SEQUENCE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1995, 92(19):8700-8704.

- Faraggi, E, Xue, B, Zhou, YQ. Improving the prediction accuracy of residue solvent accessibility and real-value backbone torsion angles of proteins by guided-learning through a two-layer neural network. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics 2009, 74(4):847-856.

- Kabsch, W, Sander, C. DICTIONARY OF PROTEIN SECONDARY STRUCTURE - PATTERN-RECOGNITION OF HYDROGEN-BONDED AND GEOMETRICAL FEATURES. Biopolymers 1983, 22(12):2577-2637.

- López, Y, Dehzangi, A, Lal, SP et al. SucStruct: Prediction of succinylated lysine residues by using structural properties of amino acids. Analytical Biochemistry 2017, 527:24-32.

- López, Y, Sharma, A, Dehzangi, A et al. Success: evolutionary and structural properties of amino acids prove effective for succinylation site prediction. Bmc Genomics 2018, 19:923.

- Ward, JJ, McGuffin, LJ, Bryson, K et al. The DISOPRED server for the prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics 2004, 20(13):2138-2139.

- Holland, RCG, Down, TA, Pocock, M et al. BioJava:: an open-source framework for bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2008, 24(18):2096-2097.

- Obradovic, Z, Peng, K, Vucetic, S et al. Exploiting heterogeneous sequence properties improves prediction of protein disorder. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics 2005, 61:176-182.

- Heffernan, R, Paliwal, K, Lyons, J et al. Improving prediction of secondary structure, local backbone angles, and solvent accessible surface area of proteins by iterative deep learning. Scientific Reports 2015, 5:11476.

- Islam, MM, Saha, S, Rahman, MM et al. iProtGly-SS: Identifying protein glycation sites using sequence and structure based features. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics 2018, 86(7):777-789.

- Sharma, A, Lyons, J, Dehzangi, A et al. A feature extraction technique using bi-gram probabilities of position specific scoring matrix for protein fold recognition. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2013, 320:41-46.

- Ashburner, M, Ball, CA, Blake, JA et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics 2000, 25(1):25-29.

- Hunter, S, Jones, P, Mitchell, A et al. InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40(D1):D306-D312.

- Kanehisa, M, Goto, S, Sato, Y et al. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40(D1):D109-D114.

- Finn, RD, Tate, J, Mistry, J et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36:D281-D288.

- Franceschini, A, Szklarczyk, D, Frankild, S et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41(D1):D808-D815.

- Weng, SL, Huang, KY, Kaunang, FJ et al. Investigation and identification of protein carbonylation sites based on positionspecific amino acid composition and physicochemical features. Bmc Bioinformatics 2017, 18:66.

- Celniker, G, Nimrod, G, Ashkenazy, H et al. ConSurf: Using Evolutionary Data to Raise Testable Hypotheses about Protein Function. Israel Journal of Chemistry 2013, 53(3-4):199-206.

- Armon, A, Graur, D, Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf: An algorithmic tool for the identification of functional regions in proteins by surface mapping of phylogenetic information. Journal of Molecular Biology 2001, 307(1):447-463.

- Shen, HB, Chou, KC. Nuc-PLoc: a new web-server for predicting protein subnuclear localization by fusing PseAA composition and PsePSSM. Protein Engineering Design & Selection 2007, 20(11):561-567.

- Alkuhlani, A, Gad, W, Roushdy, M et al. PTG-PLM: Predicting Post-Translational Glycosylation and Glycation Sites Using Protein Language Models and Deep Learning. Axioms 2022, 11(9):469.

- Ahmed, E, Michael, H, Christian, D et al. ProtTrans: Towards Cracking the Language of Life’s Code Through Self-Supervised Deep Learning and High Performance Computing. 2021; arXiv:2007.06225.

- Rives, A, Meier, J, Sercu, T et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118(15):e2016239118.

- Rao, R, Bhattacharya, N, Thomas, N et al. Evaluating Protein Transfer Learning with TAPE. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32:9689-9701.

- Jacob, D, Ming-Wei, C, Kenton, L et al. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv:1810.04805.

- Lan, ZC, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv:1909.11942.

- Yang, Z, Dai, Z, Yang, Y et al. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. Arxiv 2020.

- Wang, HF, Wang, Z, Li, ZY et al. Incorporating Deep Learning With Word Embedding to Identify Plant Ubiquitylation Sites. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8:572195.

- Yu, K, Zhang, QF, Liu, ZK et al. Deep learning based prediction of reversible HAT/HDAC-specific lysine acetylation. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2020, 21(5):1798-1805.

- Li, SH, Zhang, J, Zhao, YW et al. iPhoPred: A Predictor for Identifying Phosphorylation Sites in Human Protein. Ieee Access 2019, 7:177517-177528.

- Xu, Y, Ding, YX, Ding, J et al. Mal-Lys: prediction of lysine malonylation sites in proteins integrated sequence-based features with mRMR feature selection. Scientific Reports 2016, 6:38318.

- Zhang, N, Zhou, Y, Huang, T et al. Discriminating between Lysine Sumoylation and Lysine Acetylation Using mRMR Feature Selection and Analysis. Plos One 2014, 9(9):e107464.

- Ma, X, Guo, J, Sun, X. Sequence-Based Prediction of RNA-Binding Proteins Using Random Forest with Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance Feature Selection. Biomed Research International 2015, 2015:425810.

- Peker, M, Sen, B, Delen, D. Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease Using Complex-Valued Neural Networks and mRMR Feature Selection Algorithm. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2015, 6(3):281-302.

- He, SD, Ye, XC, Sakurai, T et al. MRMD3.0: A Python Tool and Webserver for Dimensionality Reduction and Data Visualization via an Ensemble Strategy. Journal of Molecular Biology 2023, 435(14):168116.

- Yu, JL, Shi, SP, Zhang, F et al. PredGly: predicting lysine glycation sites for Homo sapiens based on XGboost feature optimization. Bioinformatics 2019, 35(16):2749-2756.

- Chen, TQ, Guestrin, C, Assoc Comp, M: XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In: 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD): Aug 13-17 2016; San Francisco, CA. 2016: 785-794.

- Xu, Y, Li, L, Ding, J et al. Gly-PseAAC: Identifying protein lysine glycation through sequences. Gene 2017, 602:1-7.

- Ning, Q, Ma, ZQ, Zhao, XW. dForml(KNN)-PseAAC: Detecting formylation sites from protein sequences using K-nearest neighbor algorithm via Chou’s 5-step rule and pseudo components. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2019, 470:43-49.

- Dosset, P, Rassam, P, Fernandez, L et al. Automatic detection of diffusion modes within biological membranes using back-propagation neural network. Bmc Bioinformatics 2016, 17:197.

- Butt, AH, Khan, YD. Prediction of S-Sulfenylation Sites Using Statistical Moments Based Features via CHOU’S 5-Step Rule. International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics 2020, 26(3):1291-1301.

- Malebary, SJ, Rehman, MSU, Khan, YD. iCrotoK-PseAAC: Identify lysine crotonylation sites by blending position relative statistical features according to the Chou’s 5-step rule. Plos One 2019, 14(11):e0223993.

- Opitz, D, Maclin, R. Popular ensemble methods: An empirical study. Journal of artificial intelligence research 1999, 11:169-198.

- Rokach, L. Ensemble-based classifiers. Artificial intelligence review 2010, 33:1-39.

- Hasan, MM, Guo, DJ, Kurata, H. Computational identification of protein S-sulfenylation sites by incorporating the multiple sequence features information. Molecular Biosystems 2017, 13(12):2545-2550.

- Shi, MH, Lin, FX, Qian, Y et al: Research of Imbalanced Classification Based on Cascade Forest. In: IEEE International Conference on Progress in Informatics and Computing (IEEE PIC): Dec 17-19 2021; Electr Network. 2021: 29-33.

- Chu, YY, Kaushik, AC, Wang, XG et al. DTI-CDF: a cascade deep forest model towards the prediction of drug-target interactions based on hybrid features. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22(1):451-462.

- Qian, Y, Ye, SS, Zhang, Y et al. SUMO-Forest: A Cascade Forest based method for the prediction of SUMOylation sites on imbalanced data. Gene 2020, 741:144536.

- Rao, H, Shi, XZ, Rodrigue, AK et al. Feature selection based on artificial bee colony and gradient boosting decision tree. Applied Soft Computing 2019, 74:634-642.

- Friedman, JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals of statistics 2001:1189-1232.

- He, F, Wang, R, Gao, YX et al: Protein Ubiquitylation and Sumoylation Site Prediction Based on Ensemble and Transfer Learning. In: IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM): Nov 18-21 2019; San Diego, CA. 2019: 117-123.

- Zhang, YJ, Xie, RP, Wang, JW et al. Computational analysis and prediction of lysine malonylation sites by exploiting informative features in an integrative machine-learning framework. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2019, 20(6):2185-2199.

- Wang, DL, Liu, DP, Yuchi, JK et al. MusiteDeep: a deep-learning based webserver for protein post-translational modification site prediction and visualization. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48(W1):W140-W146.

- Zhao, YM, He, NN, Chen, Z et al. Identification of Protein Lysine Crotonylation Sites by a Deep Learning Framework With Convolutional Neural Networks. Ieee Access 2020, 8:14244-14252.

- Wei, XL, Sha, YT, Zhao, YM et al. DeepKcrot: A Deep-Learning Architecture for General and Species-Specific Lysine Crotonylation Site Prediction. Ieee Access 2021, 9:49504-49513.

- Xiu, QX, Li, DC, Li, HL et al: Prediction Method for Lysine Acetylation Sites Based on LSTM Network. In: 7th IEEE International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT): Oct 19-20 2019; Dalian, PEOPLES R CHINA. 2019: 179-182.

- Li, A, Deng, YW, Tan, Y et al. A Transfer Learning-Based Approach for Lysine Propionylation Prediction. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12:658633.

- Zhao, Q, Ma, JQ, Wang, Y et al. Mul-SNO: A Novel Prediction Tool for S-Nitrosylation Sites Based on Deep Learning Methods. Ieee Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2022, 26(5):2379-2387.

- Liu, Y, Ye, CF, Lin, C et al. Semi-ssPTM: A Web Server for Species-Specific Lysine Post-Translational Modification Site Prediction by Semi-Supervised Domain Adaptation. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73:2523410.

- Ning, WS, Xu, HD, Jiang, PR et al. HybridSucc: A Hybrid-learning Architecture for General and Species-specific Succinylation Site Prediction. Genomics Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2020, 18(2):194-207.

- Chen, Z, Zhao, P, Li, FY et al. PROSPECT: A web server for predicting protein histidine phosphorylation sites. Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 2020, 18(4):2050018.

- Vaswani, A, Shazeer, N, Parmar, N et al: Attention Is All You Need. In: 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS): Dec 04-09 2017 2017; Long Beach, CA. 2017.

- Meng, LK, Chen, XJ, Cheng, K et al. TransPTM: a transformer-based model for non-histone acetylation site prediction. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 25(3):bbae219.

- Liang, YY, Li, MW. A deep learning model for prediction of lysine crotonylation sites by fusing multi-features based on multi-head self-attention mechanism. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1):18940.

- Xu, DL, Zhu, YF, Xu, Q et al. DTL-NeddSite: A Deep-Transfer Learning Architecture for Prediction of Lysine Neddylation Sites. Ieee Access 2023, 11:51798-51809.

- Soylu, NN, Sefer, E. DeepPTM: Protein Post-translational Modification Prediction from Protein Sequences by Combining Deep Protein Language Model with Vision Transformers. Current Bioinformatics 2024, 19(9):810-824.

- Lv, H, Dao, FY, Guan, ZX et al. Deep-Kcr: accurate detection of lysine crotonylation sites using deep learning method. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22(4):bbaa255.

- Xu, Y, Ding, J, Wu, LY. iSulf-Cys: Prediction of S-sulfenylation Sites in Proteins with Physicochemical Properties of Amino Acids. Plos One 2016, 11(4):e0154237.

- Liu, S, Xue, C, Fang, Y et al. Global Involvement of Lysine Crotonylation in Protein Modification and Transcription Regulation in Rice. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2018, 17(10):1922-1936.

- Sun, HJ, Liu, XW, Li, FF et al. First comprehensive proteome analysis of lysine crotonylation in seedling leaves of Nicotiana tabacum. Scientific Reports 2017, 7:3013.

- Liu, KD, Yuan, CC, Li, HL et al. A qualitative proteome-wide lysine crotonylation profiling of papaya (Carica papaya L.). Scientific Reports 2018, 8:8230.

- Li, SH, Yu, K, Wu, GD et al. pCysMod: Prediction of Multiple Cysteine Modifications Based on Deep Learning Framework. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9:617366.

- Al-barakati, HJ, Saigo, H, Newman, RH et al. RF-GlutarySite: a random forest based predictor for glutarylation sites. Molecular Omics 2019, 15(3):189-204.

- Dou, LJ, Li, XL, Zhang, LC et al. iGlu_AdaBoost: Identification of Lysine Glutarylation Using the AdaBoost Classifier. Journal of Proteome Research 2021, 20(1):191-201.

- Chung, CR, Chang, YP, Hsu, YL et al. Incorporating hybrid models into lysine malonylation sites prediction on mammalian and plant proteins. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1):10541.

- Liu, Y, Li, A, Zhao, XM et al. DeepTL-Ubi: A novel deep transfer learning method for effectively predicting ubiquitination sites of multiple species. Methods 2021, 192:103-111.

- Long, HX, Sun, Z, Li, MZ et al. Predicting Protein Phosphorylation Sites Based on Deep Learning. Current Bioinformatics 2020, 15(4):300-308.

- Zahiri, Z, Mehrshad, N, Mehrshad, M. DF-Phos: Prediction of Protein Phosphorylation Sites by Deep Forest. Journal of Biochemistry 2023, 175(4):447-456.

- Wang, RL, Wang, Z, Wang, HF et al. Characterization and identification of lysine crotonylation sites based on machine learning method on both plant and mammalian. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1):20447.

- Li, FY, Zhang, Y, Purcell, AW et al. Positive-unlabelled learning of glycosylation sites in the human proteome. Bmc Bioinformatics 2019, 20:112.

- Dai, YH, Deng, L, Zhu, F. A model for predicting post-translational modification cross-talk based on the Multilayer Network. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 255:124770.

- Zhu, F, Deng, L, Dai, YH et al. PPICT: an integrated deep neural network for predicting inter-protein PTM cross-talk. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24(2).

- Deng, L, Zhu, F, He, Y et al. Prediction of post-translational modification cross-talk and mutation within proteins via imbalanced learning. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 211:118593.

- Simpson, CM, Zhang, B, Hornbeck, P et al. Systematic analysis of the intersection of disease mutations with protein modifications. Bmc Medical Genomics 2019, 12:109.

| Name | Website | PTM Type | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniport[11,12] | https://www.uniprot.org/ | Multiple | 570,420 reviewed proteins, 251,131,639 unreviewed proteins |

| dbPTM[13,14] | https://awi.cuhk.edu.cn/dbPTM/ | Multiple | 2235664 sites, 70+PTM types, 40+ integrated databases, 30+ benchmark datasets |

| PhosphoSitePlus[19] | https://www.phosphosite.org/homeAction | Multiple | 59469 PTM sites, 13 PTM types |

| CPLM 4.0[15] | http://cplm.biocuckoo.cn/ | Multiple | 463,156 unique sites of 105,673 proteins for up to 29 PLM types across 219 species |

| qPTM[20] | http://qptm.omicsbio.info/ | Multiple | 11,482,553 quantification events for 660,030 sites on 40,728 proteins under 2,596 conditions |

| PupDB[21] | https://cwtung.kmu.edu.tw/pupdb/ | Pupylation | 268 pupylation proteins with 311 known pupylation sites and 1123 candidate pupylation proteins |

| DEPOD[22] | https://depod.bioss.uni-freiburg.de/ | Phosphorylation | 194 phosphatases have substrate data |

| O-GlcNAcAtlas[23] | https://oglcnac.org/atlas/ | O-GlcNAcylation | 16877 Unambiguous sites, 10058 ambiguous sites |

| Phospho.elm[24] | http://phospho.elm.eu.org/ | Phosphorylation | 42914 instances, 11224 sequences |

| CarbonylDB[25] | https://carbonyldb.missouri.edu/CarbonylDB/index.php/ | Carbonylation | 1495 proteins, 3781 PTM sites, 21 species |

| Scop3P[26] | https://iomics.ugent.be/scop3p/index | Phosphorylation | 108130 modifications, 20394 proteins |

| O-GlycBase[27] | https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/datasets/OglycBase/ | O-Glycosylation | 242 proteins |

| dbSNO[28] | http://140.138.144.145/~dbSNO/index.php | S-nitrosylation | 174 experimentally verified S-nitrosylation sites on 94 S-nitrosylated proteins |

| UbiNet 2.0[29] | https://awi.cuhk.edu.cn/~ubinet/index.php | Ubiquitination | 3332 experimentally verified ESIs |

| UbiBrowser 2.0[30] | http://ubibrowser.bio-it.cn/ubibrowser_v3/ | ubiquitination | 1,884,676 predicted high confidence ESIs, 8,341,262 potential E3 recognizing motifs, 4,068 known ESIs from literature |

| PhosPhAt[31] | https://phosphat.uni-hohenheim.de/ | Phosphorylation | 10898 phosphoproteins,64128 serine sites, 13102 threonine sites, 2672 tyrosine sites |

| PTM | Tools | Dataset | Window Size | Feature Extraction Method | Classifier | Website | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lysine crotonylation | BERT-Kcr | used by Lv et al [164] | 31 | BERT | BiLSTM | http://zhulab.org.cn/BERT-Kcr_models/data | [10] |

| Lysine lactylation | Auto-Kla | UniProt | 51 | Token embedding, position embedding, transformer encoder | AutoML, MLP | https://github.com/tubic/Auto-Kla | [32] |

| Cysteine S-sulphenylation | DeepCSO | UniprotKB | 35 | NUM, EAAC, BE, AAindex, CKSAAP, PSSM | LSTM, CNN, RF, SVM | http://www.bioinfogo.org/DeepCSO | [36] |

| phosphorylation | -- | dbPTM | 21 | AAindex, Binary-encoding, ASA, secondary structure (coil, helix and strand), disordered regions, BP, MF, CC, protein functional, domain data from InterPro, KEGG pathway and functional annotation |

RF, SVM | -- | [46] |

| phosphorylation | PredPhos | Phospho.ELM version 9.0, Phospho-POINT and PhosphoSitePlus | -- | PSSM, evolutionary conservation score, disorder, ASA, pair potential, atom and residue contacts, Topographical index, physicochemical features, four-body statistical pseudo-potential, local structural entropy, side-chain energy, Voronoi Contacts, structural conservation score, Two-step feature selectio | Ensemble method, SVM | -- | [49] |

| Succinylation | SSKM_Succ | Training data: PLMD and Uniprot Test data: dbPTM |

21 | Information of Proximal PTMs, Grey Pseudo Amino Acid Composition, K-Space, PSAAP | SVM, RF, NB | https://github.com/yangyq505/SSKM_Succ.git | [51] |

| S-sulfenylation | SulSite-GTB | Carroll Lab, RedoxDB and UniProtKB |

21 | AAC, DPC, EBGW, KNN, PSAAP, PsePSSM, PWAAC | GTB | https://github.com/QUST-AIBBDRC/SulSite-GTB/ | [57] |

| lysine phosphoglycerylation | iDPGK | PLMD | 15 | AAC, PCAAC, AAPC, BLOSUM62, PSSM | DT, RF, SVM | http://mer.hc.mmh.org.tw/iDPGK/. | [77] |

| Succinylation | CNN-SuccSite | PLMD 3.0 | 31 | PspAAC, CKSAAP, PSSM | CNN |

http://csb.cse.yzu.edu.tw/ CNN-SuccSite/ |

[79] |

| Glycosylation and Glycation |

PTG-PLM | UniProt | 31 | ProtBERT-BFD, ProtBERT, ProtALBERT, ProtXLNet, ESM-1b and TAPE | CNN, SVM, LR, RF, and XGBoost | https://github.com/Alhasanalkuhlani/PTG-PLM | [118] |

| Formylation | LFPred | Uniport, PLMD and dbPTM | 41, information entropy | AAC, BPF, AAI | KNN | -- | [136] |

| S-Sulfenylation | S-Sulfenylation | Conducted by Xu et al. [165] and Hasan et al. [142] |

21 | PseAAC, SVV, SM, PRIM, R-PRIM, FV, AAPIV, RAAPIV | BP-NN | https://www.github.com/ahmad-umt/S-Sulfenylation | [138] |

| Sumoylation | SUMO-Forest | UniProt | 21 | PSAAP, PseAAC, SP, BK | Cascade Forest | https://github.com/sandyye666/SUMOForest | [145] |

| Ubiquitylation and sumoylation | DeepUbiSumoPre | Uniprot/Swiss-Prot | 49 | one-hot, PCPs | CNN, DNN, stacking method, transfer learning | https://github.com/ruiwcoding/DeepUbiSumoPre | [148] |

| lysine crotonylation | -- | collected verified Kcr sites on non-histone proteins from papaya |

From 2 to 37 | BE, CKSAAP, AAC, EAAC, EGAAC | CNN | http://www.bioinfogo.org/pkcr | [151] |

| Lysine Crotonylation |

DeepKcrot | Collected from [166,167,168] | 29 | EGAAC, WE | LSTM, CNN, RF | http://www.bioinfogo.org/deepkcrot | [152] |

| Lysine Acetylation Sites | -- | DeepAcet and UniProt | 21 | one-hot encoding, physical and chemical properties including molecular weight, isoelectric point, carboxylic acid dissociation constant and amino acid dissociation constant | LSTM | -- | [153] |

| Lysine propionylation | -- | PLMD and Uniport | 17 | RNN, LSTM | Transfer learning, SVM | http://47.113.117.61/. | [154] |

| Succinylation | HybridSucc | PLMD 3.0, PhosphoSitePlus and dbPTM | -- | PseAAC, CKSAAP, OBC, AAindex, ACF, GPS, PSSM, ASA, SS, and BTA | DNN, PLR | http://hybridsucc.biocuckoo.org/ | [157] |

| -Nitrosylation | Mul-SNO | training set: Li et al. [169], independent test set: DeepNitro | 31 | BiLSTM, BERT | RF, lightgbm, xgboost | http://lab.malab.cn/∼mjq/Mul-SNO/ | [155] |

| phosphorylation | PROSPECT | UniProt | 27 | one-of-K, EGAAC and CKSAAGP | CNNone-of-K, CNNEGAAC and RFCKSAAGP | http://PROSPECT.erc.monash.edu/ | [158] |

| Lysine Glutarylation | iGlu_AdaBoost | Conducted by Al-barakati et al. [170] from PLMD, NCBI, and SWISS-PROT | 23 | 188D, CKSAAP, and EAAC | AdaBoost | -- | [171] |

| Lysine malonylation | Kmalo | PLMD and LEMP | 11~39 | AAC, one hot encoding, Pse-AAC, AAindex, PSSM | hybrid models contain multiple CNNs, random forests and SVM | https://fdblab.csie.ncu.edu.tw/kmalo/home.html | [172] |

| ubiquitination | DeepTL-Ubi | PhosphoSitePlus, mUbiSida and PLMD | 31 | one-hot | transfer deep learning method | https://github.com/USTC-HIlab/DeepTL-Ubi | [173] |

| Phosphorylation | -- | iPhos-PseEn | 13 | BE | CNN, BLSTM | -- | [174] |

| phosphorylation | DF-Phos | dbPAF and Phospho.ELM | 33 | CTD, DDE, EAAC, EGAAC, a series of PseKRAAC, GrpDDE, kGAAC, LocalPoSpKaaF, QSOrder, SAAC, SOCNumber, ExpectedValueGKmerAA, ExpectedValueKmerAA, ExpectedValueGAA, ExpectedValueAA | Deep Forest | https://github.com/zahiriz/DF-Phos | [175] |

| lysine crotonylation | -- | UniProt and pkcr | 31 | AAC, AAPC, BE, CKSAAP, EAAC, EGAAC and PSSM | SVM, RF | -- | [176] |

| glycosylation | GlycoMine_PU | UniProt | 15 | AAC, CTD, AAindex, Pseudo-AAC, Sequence-order, Auto-correlation | RF, SVM, One-SVM | http://glycomine.erc.monash.edu/Lab/GlycoMine_PU/ | [177] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).