1. Introduction

Analysis and sorting of pathogenic organisms by flow cytometry, particularly in cell sorters, is constrained by biosafety and waste-handling issues. For pathogen-related studies, flow cytometer analyzers are typically placed inside BSL-2 biosafety hoods, which complicates handling of both samples and the instrument [

1,

2]. Although many flow cytometer manufacturers offer instruments designed for use in a BSL-2 hood, very few provide a fully integrated BSL-2 safety enclosure built directly into the sorter. One notable example is Thermo Fisher’s Bigfoot Spectral Cell Sorter, which features its own Class II biosafety cabinet and aerosol management system [

3]. In our earlier work, we used this instrument to handle pathogenic bacteria, including antibiotic--resistant strains [

4]. While detailed protocols for flow cytometry instrument wash steps were provided in the paper to prevent contamination, safe disposal of liquid pathogenic waste remains a significant challenge.

After sample analysis, waste collected in the cytometer’s waste tanks is often treated with disinfectants such as 10% bleach to kill viable pathogens [

5]. However, once treated with these chemicals, the waste becomes non-autoclavable, making transport of large volumes of chemically treated waste to autoclave facilities risky and logistically challenging. Moreover, most waste tanks supplied with flow cytometers are not designed for direct autoclaving. This adds extra challenges to waste disposal and increases environmental risks, such as improper disposal of chemically contaminated fluid, potential pathogen release, or chemical pollution [

6,

7]. Therefore, developing alternative waste treatment methods is crucial to effectively inactivate pathogens, reduce environmental impact, and ensure safe, compliant disposal practices.

A recent study by Kirsch et al. presented a UV-C flow-through method for decontaminating sheath fluid in flow cytometric cell sorters, achieving a 5-log reduction in bacteria and enabling more reliable aseptic cell sorting [

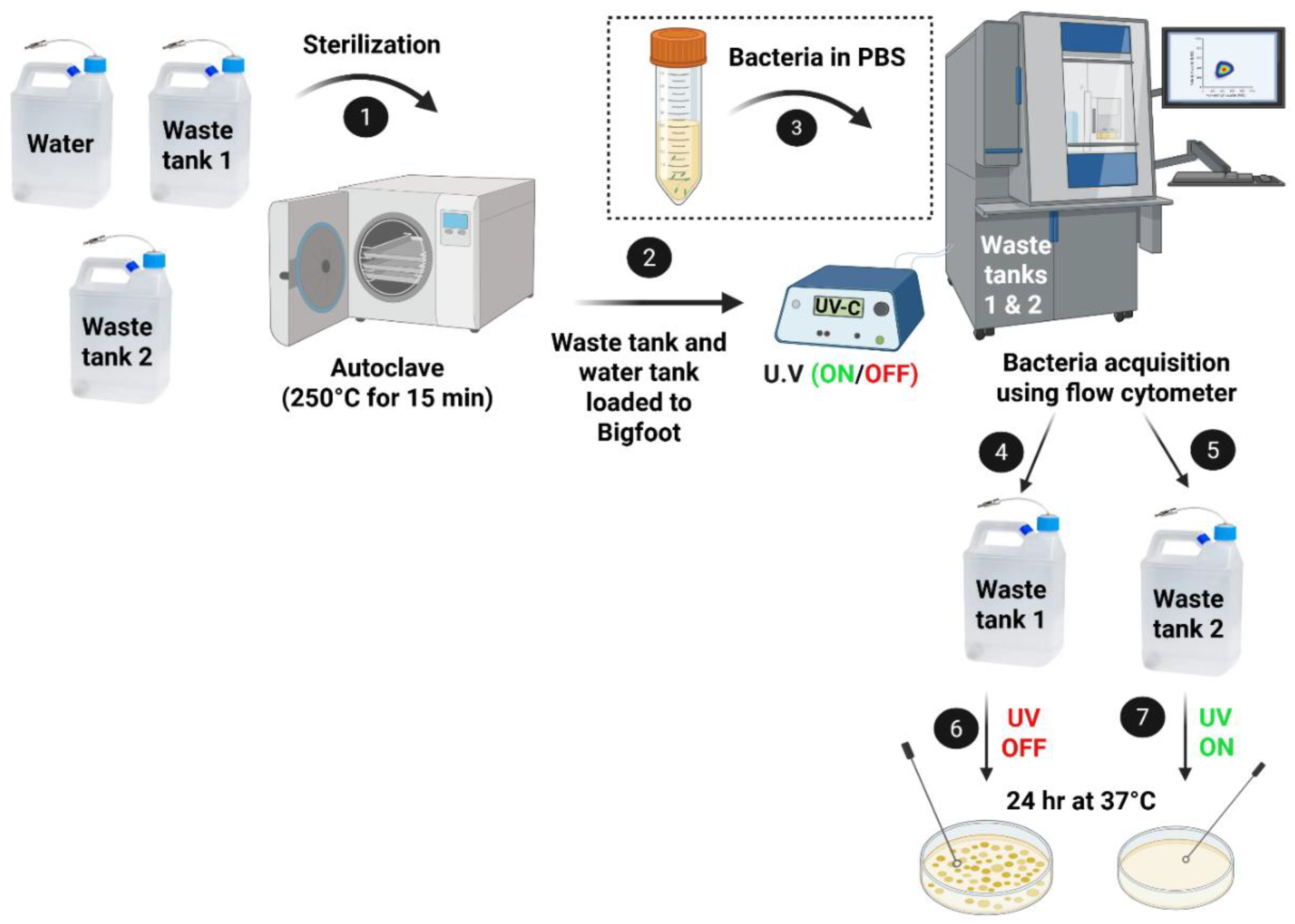

8]. While our approach is similar and uses the same device, their work primarily emphasized disinfecting sheath fluid before conducting flow cytometry experiments. In contrast, the disinfection efficiency of the device has not yet been evaluated after the sorter has processed samples containing pathogenic organisms, where potential carryover poses an additional biosafety concern. Furthermore, the safe handling and disposal of waste samples containing viable pathogenic organisms pose a significant challenge that requires attention beyond sheath-fluid decontamination alone. The integration of the flow cytometers with a built-in Class II biosafety cabinet, an autoclavable waste tank, and a UV disinfection device in the waste stream provides continuous, layered protection. These features greatly enhance operator safety by inactivating pathogens before waste is handled, ensuring infectious material is neutralized both during sorting and after disposal. In addition, this system reduces chemical usage, minimizes the need for frequent decontamination, and supports high-throughput workflows in BSL-2 environments while maintaining strict biosafety compliance. A representative image illustrating the connection between the flow cytometer and the UV device connected before the waste tank collection is presented in

Figure 1. In this work, we evaluate the efficacy of the UV device for effective decontamination of pathogenic organisms prior to their release into the flow cytometer’s waste stream.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Sample Preparation

Three bacterial species: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 were obtained from ATCC and cultured separately on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates for 24 hours at 37 °C in a Fisher Scientific Isotemp incubator. To prepare TSA agar, 40 g of agar was dissolved in 1 L of sterile water. Agar suspensions were autoclaved and cooled before pouring onto an empty agar plate. From each overnight culture, colonies were inoculated into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and bacterial concentrations were adjusted based on the initial optical density (OD) measured with a WPA Biowave CO8000 cell density meter. The final working concentrations for E. coli, S. typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae used in flow cytometry experiments were 7 × 10⁷, 6 × 10⁶, and 5 × 10⁶ CFU/mL, respectively. High inoculum levels (≥10⁶ CFU/mL) were chosen, as this is the recommended cell concentration for flow cytometry applications. Concentrations were determined by performing serial dilutions of the OD-adjusted suspensions, plating on TSA agar, and back-calculating from colony counts. Colonies were counted using ImageJ 2 software.

2.2. UV-C Device

The UV-C

flowShield unit (APE Berlin) was installed immediately upstream of the tubing leading to the flow cytometer’s waste streams. The UV light operates at full power (delivering a dose of 40 J/cm²) in a reactor maintained at 17 °C, with an emission wavelength range of 200–280 nm. A complete user manual for the UV-C flow shield, including the specifications and working principle, can be accessed from A.P.E.

flowShield Berlin [

9].

2.3. Flow Cytometry Experiments

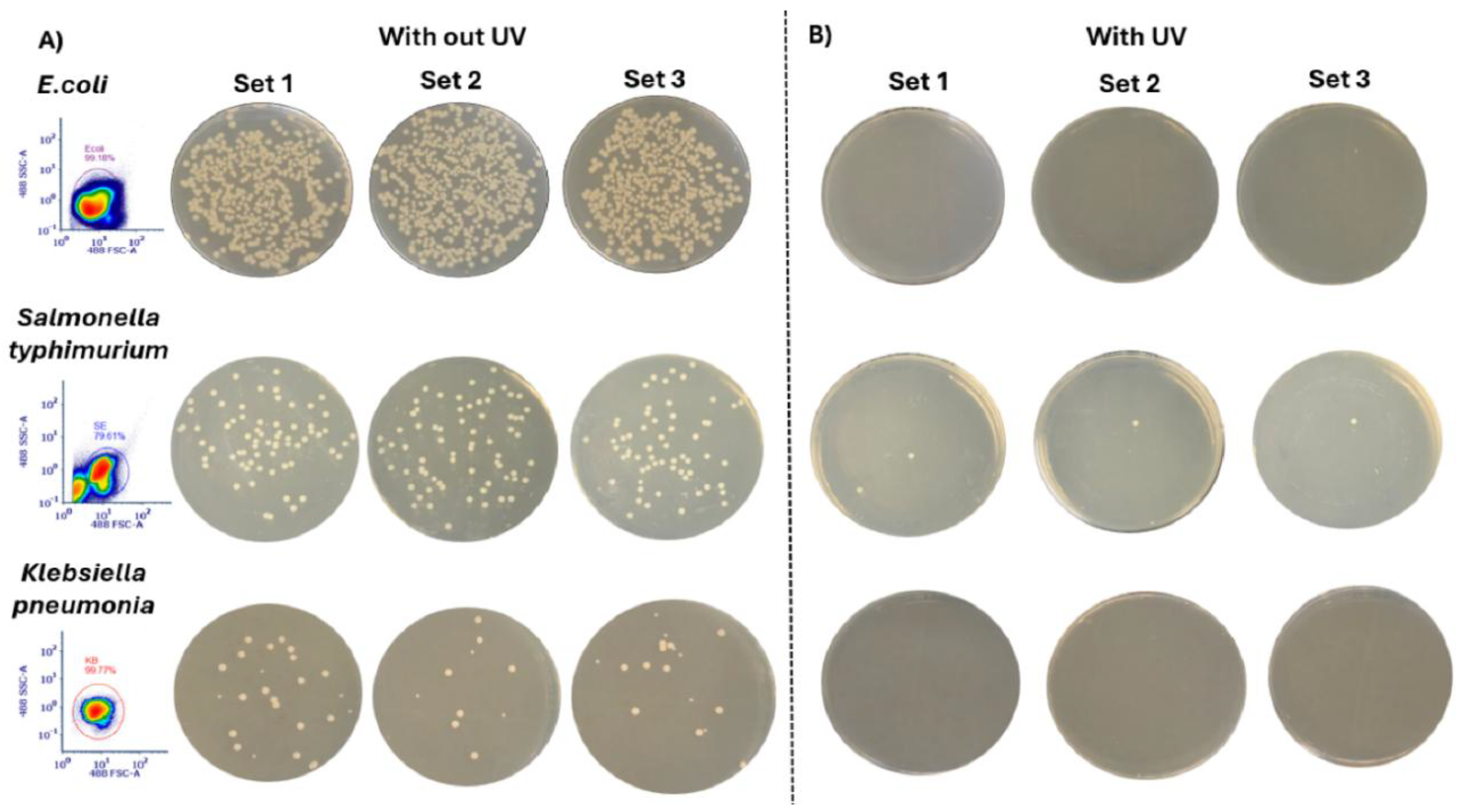

The water and the empty waste tanks for the Bigfoot Spectral Flow Sorter (Thermo Fisher) were sterilized by autoclaving at 250 °C for 15 minutes. After sterilization, the waste tanks were allowed to cool to room temperature for about 4 hours (per the manufacturer’s recommendation) before being installed in the cytometer. Following routine QC, bacterial samples in PBS were run with 600,000 events/sec per species at 50% flow rate. Using an FSC-A vs SSC-A scatter plot, bacterial clusters were identified. The scatter plots shown in

Figure 2 were plotted using FCS Express 7.0 software. The cytometer performs a double nozzle wash after each sample. Samples collected from the waste chamber were autoclaved again before starting experiments with the next bacterial species. The manufacturer advises against autoclaving the sheath fluid, so the sheath fluid was instead sterile filtered (0.2 µm pore size) and plated on TSA agar to verify sterility.

3. Results and Discussion

The schematic in

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow for evaluating the efficacy of a UV-C device for bacterial disinfection in the flow cytometer’s waste stream. After sterilization, both the waste and water tanks were installed in the flow cytometer instrument. A known bacterial concentration was inoculated into sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). As the cytometer analyzed the bacterial suspension, waste fluids were collected into two separate tanks: one tank received waste without UV exposure (control), while the other tank received waste continuously exposed to UV-C light just before entering the tank. These waste samples, both UV-exposed and non-exposed, were then plated on TSA agar to assess bacterial viability.

Three bacterial species,

Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, were selected for analysis. The volumes of waste collected from the tanks ranged from 17 to 50 mL. Despite using the same initial sample volume and analyzing the same number of events, collected waste volume varied due to sheath flow dynamics, aborted or deflected drops, automatic flushes, and the aerosol management system, which is typical in flow cytometry [

7].

Figure 3 illustrates the resulting colony growth for each species under the two conditions (with and without UV exposure). For each species, waste samples were collected from both tanks, plated onto three sets of TSA agar (n = 3 per species), and incubated for 24 hours. The SSC-A vs FSC-A (488 nm laser) scatter plots are shown for each species to visualize and verify the cell populations analyzed in the flow cytometer. In the absence of UV exposure, all three species formed colonies on TSA agar plates (

Figure 3A). Both

E. coli and

K. pneumoniae showed no detectable colony growth after UV-C exposure, confirming complete (100%) inactivation under the experimental conditions (

Figure 3B). In contrast,

S. typhimurium exhibited one or two surviving colonies.

4. Discussion

The UV device disinfection approach demonstrated high efficacy for

E. coli and K. pneumoniae, achieving complete inactivation under the tested conditions. The partial survival of

S. typhimurium is likely attributable to the inherent tendency of

Salmonella sp. to form small aggregates or clumps, which can shield some cells from UV light. Such species-specific variations in UV susceptibility have been widely reported in the literature [

10,

11,

12] and highlight the importance of considering microbial aggregation and flow conditions when implementing UV-based disinfection strategies.

It is important to note that while the volumes of waste collected varied between 17–50 mL due to due to routine operational variations and fluidic dynamics inherent to flow cytometry, this did not affect the interpretation of results. The high initial bacterial concentrations ensured that any viable cells remaining after UV-C exposure would have been detected on TSA plates, confirming the robustness of the disinfection.

This approach demonstrates that integrating UV-C disinfection into the flow cytometer waste stream is a chemical-free, effective method to inactivate pathogenic bacteria. It has applications in high-throughput laboratories, core flow cytometry facilities, clinical diagnostics, and research settings handling antibiotic-resistant or high-risk pathogens. The system also reduces chemical use, minimizes operator exposure, and simplifies waste management in BSL-2 and BSL-3 environments.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating a UV-C disinfection unit into the flow cytometer waste stream provides a simple, chemical-free approach to enhance biosafety during pathogen analysis. The system achieved complete inactivation of E. coli and K. pneumoniae and partial inactivation of S. typhimurium, highlighting strong yet species-dependent efficacy. It should be noted that the fluid line transporting waste from the cytometer to the waste collection unit is not typically exposed to any decontamination process, which can allow viable microorganisms to persist within the tubing and downstream waste. When combined with the Bigfoot Spectral Cell Sorter’s built-in Class II biosafety cabinet, UV-C disinfection unit and autoclavable waste tanks, the setup provides continuous, layered protection, reduces chemical usage, and supports high-throughput workflows. Limitations such as bacterial aggregation, fluid opacity, and uneven UV exposure may prevent complete inactivation for some species, indicating that further optimization and validation under varied experimental conditions are needed, which will be addressed in future studies.

Author Contributions

SNI, JPR, BR, and EB were responsible for conceptualizing and designing the research. SNI performed all the experiments. All members contributed to the manuscript draft. BD assisted with the usage and maintenance of the cell sorter. SNI and BD developed the working protocols for safely growing and maintaining the pathogenic organisms. SNI, JPR, BR, and EB were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. JPR, EB, and BR are responsible for funding and resource acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Center for Food Safety Engineering at Purdue University, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, under Agreement No. 59-8072-1-002 and Agreement No. 58-8042-0-061. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not include any studies that involved human participants or animals.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are presented within the paper and the supplementary documents.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors hereby declare that they have no competing interests. We attest that we have no relationships or connections with any organization or entity that may have a financial or personal interest in the presented work.

References

- Robinson, J.P., et al., Flow cytometry: The next revolution. Cells, 2023. 12(14): p. 1875.

- Schmid, I., et al., Standard safety practices for sorting of unfixed cells. Curr Protoc Cytom, 2007. Chapter 3: p. Unit3 6.

- ThermoFisher. Bigfoot spectral cell sorter features. 2020. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/life-science/cell-analysis/flow-cytometry/flow-cytometers/bigfoot-spectral-cell-sorter/features.html?gclid=CjwKCAjwrdmhBhBBEiwA4Hx5g49IaWVVv0liQQ49wa1iTpQSQ_omgjWlw4NjDh9F95_iCUbL_JaHsBoCyD4QAvD_BwE&ef_id=CjwKCAjwrdmhBhBBEiwA4Hx5g49IaWVVv0liQQ49wa1iTpQSQ_omgjWlw4NjDh9F95_iCUbL_JaHsBoCyD4QAvD_BwE:G:s&s_kwcid=AL!3652!3!610458580017!!!g!!!12667906722!123084934209&cid=bid_pca_fsi_r01_co_cp1359_pjt0000_bid00000_0se_gaw_dy_lgn_ins.

- Narayana Iyengar, S., et al., Identifying antibiotic-resistant strains via cell sorting and elastic-light-scatter phenotyping. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2024. 108(1): p. 406. [CrossRef]

- Belkina, A.C., et al., Guidelines for establishing a cytometry laboratory. Cytometry A, 2024. 105(2): p. 88–111. [CrossRef]

- Nwobi, N.L., et al., Waste management and environmental health impact: sustainable laboratory medicine as mitigating response. Clin Biochem, 2025. 139: p. 110985. [CrossRef]

- Aspland, A., et al., Risk awareness during operation of analytical flow cytometers and implications throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Cytometry A, 2021. 99(1): p. 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, J., et al., A UV-C LED-based unit for continuous decontamination of the sheath fluid in a flow-cytometric cell sorter. Eng Life Sci, 2022. 22(8): p. 550–553. [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, K.v. APE flowShield User manual. 2018/2019. Available online: https://www.ape-berlin.de/en/.

- Coohill, T.P. and J.L. Sagripanti, Overview of the inactivation by 254 nm ultraviolet radiation of bacteria with particular relevance to biodefense. Photochem Photobiol, 2008. 84(5): p. 1084–90. [CrossRef]

- Yaun, B.R., et al., Response of Salmonella and Escherichia coli O157:H7 to UV energy. J Food Prot, 2003. 66(6): p. 1071–3. [CrossRef]

- Masjoudi, M., M. Mohseni, and J.R. Bolton, Sensitivity of Bacteria, Protozoa, Viruses, and Other Microorganisms to Ultraviolet Radiation. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol, 2021. 126: p. 126021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).