1. Introduction

Trisomy 21, or Down Syndrome (DS), is the most common genetic disorder among newborns. It is an autosomal aneuploidy, usually caused by a partial or complete duplication of chromosome 21 [

1,

2,

3]. Worldwide, it is estimated that one case in 1,000 births is a child with DS, and there were almost no changes in the prevalence of DS between 1990 and 2019 [

4]. The prevalence of DS per 10,000 live births in the early 2000 was 15.74 in the United States [

5] and 79 in Europe [

6].

There are considerable phenotypic differences between individual patients with DS. However, there are specific features common to all. Regarding craniofacial characteristics, it is frequent to observe brachycephaly, relative macroglossia, craniofacial dysmorphia, oblique palpebral fissures and epicanthus, ear pinna malformations, and flat nasal base [

1]. It is well known that the underdevelopment of the midface leads to palatal atresia and a narrowed, elevated, and V-shaped palatal vault [

1,

7,

8]. These, along with a protruding tongue, contribute to the establishment of malocclusions such as anterior open bite, posterior crossbite, and higher incidence of class III dental malocclusion [

1,

9].

The presence of hypotonic muscles in DS reveals an incomplete mouth closure, a protruding tongue, and increased oral breathing [

1]. This imbalance causes oral-motor problems, compromising the oral functions of sucking, chewing, and swallowing [

1,

9,

10,

11]. It also steers the orofacial growth to develop malocclusion and craniofacial malformations, like midface hypoplasia. These oral-motor features also compromise speech [

12,

13]. Indeed, young children with DS typically have a high and narrow arched palate, and a relatively small jaw and mouth when compared to their tongue, which together with hypotonic muscles impact sound articulation [

11,

14]. Moreover, recent research suggests that there is an auditory-motor link that influences speech perception, that emerges early in infancy [

15]. For example, experimentally induced oral-motor impairments have been found to disrupt infants’ ability to discriminate speech sound contrasts. It is thus possible that the oral-motor problems in DS not only affect speech production, but also speech perception.

To prevent the development of malocclusion in children with DS, Castillo-Morales [

16] developed a method of orofacial regulation therapy, which promotes muscle stimulation exercises combined with the use of an intraoral appliance named stimulating palatal plate (SPP). This method was used in several studies demonstrating improvement in tongue posture, lip closure and oral-facial function in children with DS after the use of SPP [

8,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The SPP designed by Castillo-Morales was a removable orthodontic device to be used, preferably, before the eruption of primary teeth. It should be placed against the upper arch. It had a stimulatory area — lingual stimulator, located on the lingual surface of the SPP. This lingual stimulator consisted of an acrylic button with a circular or oval form, approximately 8mm in diameter. The oval form is used in children with tongue diastasis, while the round-shaped button should be used in children without it. A second stimulation area can be added — a vestibular stimulator, to encourage movements, if needed. It is made of small spheres or extra stimulation zones and/or tiny grooves or elevations located in the anterior and sublabial edge of the plate [

17].

Building on Castillo-Morales work, Andrade [

21] proposed a modified SPP [

22]. The modification consisted of adding an extension of acrylic to the SPP and a “pacifier-like” mouth shield. This modification addressed several issues with the use of the SPP, namely the acceptance of the SPP by the child, and parents’ confidence in its use given the additional safety features. These allowed an extended use of the SPP, also during the night, without the risks of loss of the plate, swallowing or choking. A comparison between the effects of the traditional SPP and the modified SPP showed no significant differences in most parameters. However, two parameters displayed significantly better results with the modified SPP: mouth semi-open or open with the tongue on top of the lower lip or pressing it, and open mouth with tongue inside the mouth [

21]. In the present study, the modified SPP proposed by Andrade [

21] was used and will be referred to as pacifier SPP (PSPP).

To manufacture the SPP, it is necessary to take impressions of the upper arch. The method that is conventionally implemented is the use of a quick-setting material to obtain a plaster model. The SPP is then designed over this plaster model. Hence, the impression procedure is a crucial step. Nevertheless, it has possible associated complications. According to Chate [

23] and Behera et al. [

24], this type of procedure may cause aspiration of fragments of the impression material, airway obstruction that might be partial or complete, cyanosis, and development of erosion or infection. In order to reduce the overall risk for children, and infants in particular, the workflow must be adapted. The introduction of intraoral scanners as a feasible and safer procedure for neonates and infants with craniofacial malformations has been documented in the literature [

25,

26]. Given the benefits observed, in this study we explored using intraoral scanners for producing the SPP.

This study proposes a new digital workflow for the construction of a modified SPP, with the goals of facilitating the production and use of this therapeutic device, and thus improving oral morphology and functionality, and promoting auditory-motor language abilities in infants with oral-motor dysmorphologies.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was developed within the P2LINK project (Perception-Production Link in Early Infancy: A language acquisition oral-motor intervention study), at the Lisbon Baby Lab of the Centre of Linguistics of the University of Lisbon. The research was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon (19_CEI2021). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants’ legal guardians.

2.1. The Clinical Cases

Five children with DS were included in the study. The five children were referred to the P2LINK project by the clinical staff of the Child Development Center – Diferenças, and constituted the first group of children that participated in the project, representing varied age and sex. Participants 1 and 2 were 5-month-old girls; Participant 3 was a 7-month-old boy; Participant 4 was a 11-month-old boy; and Participant 5 was a 6-month-old girl. They were all born full-term. Only participant 4 had other associated comorbidities (with deglutition problems and a collapsed lung after cardiac surgery, leading to the use of a nasogastric tube and oxygen tube until 10 months of age). On examination by a speech therapist and a pediatric dentist, all the five infants presented tongue protrusion, hypotonia of the upper lip, and open mouth with protruding low lips (

Figure 1 – Panels a-e). These oral characteristics are indicators for the use of SPP [

8,

16,

17,

18,

20,

27].

2.2. Materials

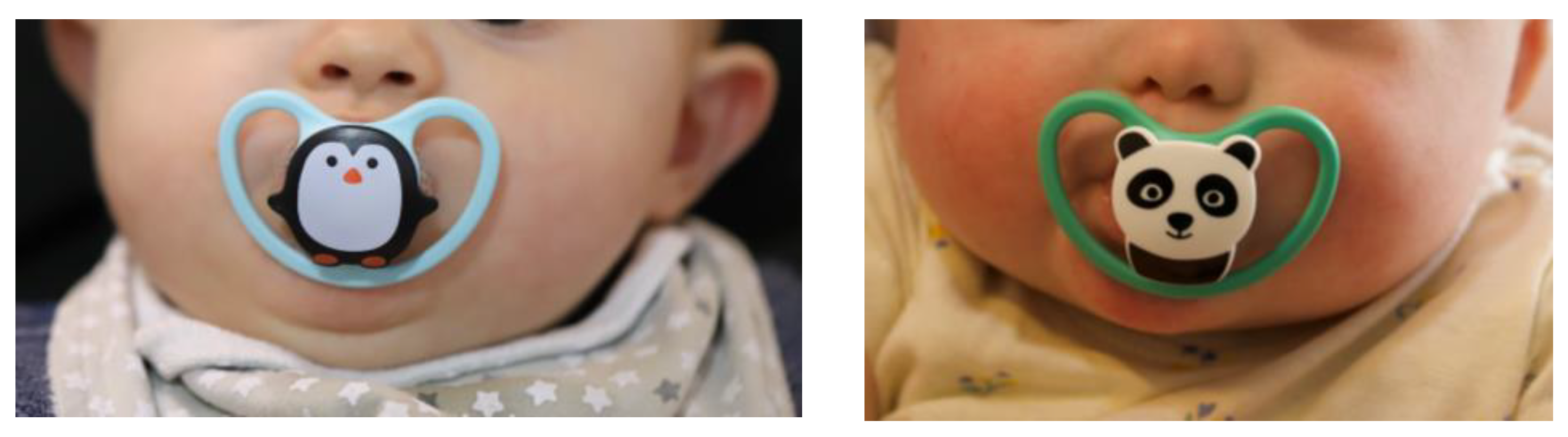

A modified SPP was used. This pacifier SPP (PSPP) exhibits a lingual stimulating button in the lingual surface of the plate, and includes an acrylic extension that terminates in a mouth shield with a handle (

Figure 2). The stimulating button is designed to regulate tongue position, by repositioning the tongue within the oral cavity, and to increase tongue activity. The extension with the mouth shield, besides preventing the infant from swallowing or choking on the plate, promotes the closing of the mouth behind the shield and facilitates nasal breathing. The angle and length of the extension are adjusted according to the lip and mouth occlusion features of each child. Overall, the PSPP is designed to improve oral-motor functions.

For the impressions of upper and lower arch, a digital intraoral Dexis™ IS 3800W scanner (Dental Imaging Technologies Corporation, Hatfield, PA, USA) was used. This is a small, light and wireless intraoral scanner (IOS) device.

The use of the PSPP was monitored through video registration sessions and language and communication assessments. Video registration sessions, a common procedure in interventions with a palatal plate, were made taking advantage of personal and home digital devices owned by the infant’s family, such as smart phones, iPad and computers, through a communications platform that allows audio-visual connection between users. The video recordings had two main goals: (i) to monitor the use of the PSPP, measure infant’s and parents’ acceptability of the plate, and identify the need for additional clarification or adjustments; and (ii) provide data for the assessment of oral-morphological variables. Two parental questionnaires were used for the language and communication assessments: The Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (CSBS-DPTM) Infant-Toddler Checklist, a screening tool that measures the communicative, social-affective, and symbolic development of infants between 6 and 24 months of age [

28]; The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) Short Forms, that assesses infants and toddlers’ early language abilities [

29]. Parents’ response to the questionnaires was obtained via online forms. The questionnaires had two goals: to evaluate infants’ developing language and communication abilities before, during, and after use of the PSPP; to measure parents’ acceptability of the overall workflow through their engagement in responding to the questionnaires.

2.3. Procedure

The step-by-step application of the workflow is described below, from the mouth scanning protocol and model printing, to PSPP manufacturing and delivery, and assessment of oral-morphological features, language abilities and acceptability of the PSPP.

2.3.1. Mouth Scanning and Model Printing

Mouth scanning of the infants was conducted using the digital IOS Dexis™ IS 3800W to register both jaws. Digital impressions were registered by the DEXIS™ IS ScanFlow. During scanning, the infants were comfortably lying down on a baby recliner chair, and a pediatric dentist positioned herself in front of them. A research assistant helped with the process.

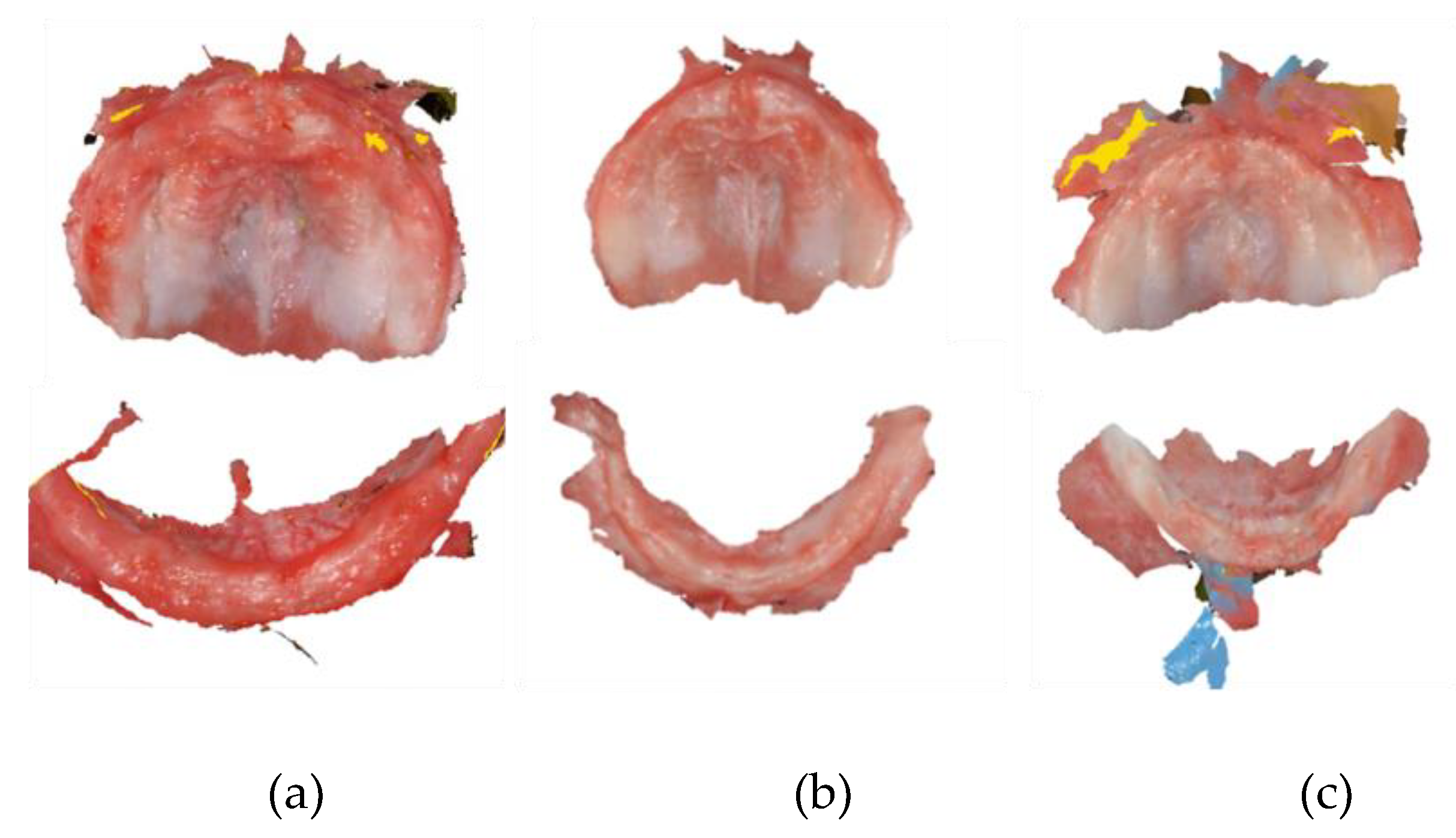

A standard scanning protocol was used, in order to maximize scan efficiency. Scanning started at the upper jaw, in the left maxillary tuberosity, and the head of the scanner was moved along the alveolar arch, passing the incisive papilla up to the contralateral maxillary tuberosity. From here, the palate was scanned, and finally, the vestibule area of the maxilla, including the labial and buccal frenula. In this area, the scan was tilted in its vertical axis. After that, the lower jaw was scanned, starting at the left retromolar area. The head of the scanner was placed in the lingual side and ran along the mandibular alveolar arch until the right retromolar area was reached. Then, the scanner was rotated and the buccal side was scanned, doing the opposite path. If the scanner lost its scanning position, the incisive papilla or the last successfully scanned areas were retaken as a starting point. Digital impressions for three of the infants are shown in

Figure 3.

The removable head of the intraoral scanner was changed between patients and cleaned using a thermal disinfector (Autoclave class B). After that, it was packaged in a sterilization sleeve.

After acquiring the raw scan, the DEXIS™ IS ScanFlow post-processing tool calculated the surface of the scan. The scan file was saved in the Polygon File Format (.PLY) and Standard Tessellation Language (.STL), and sent to the laboratory. Then, the files were exported to the EXOCAD/Model Creator design program, removing and smoothing out possible gaps in information created by the intraoral scanner, thus obtaining a new STL file. This new STL file was printed with the Microlay Microform software (Microlay Dental 3D Printers, Madrid, Spain), which allowed us to define the best strategy for printing each model individually. The printer used was Microlay Versus 385 (Microlay Dental 3D Printers, Madrid, Spain), and the acrylic used to print the model was Microlay’s Printfit Dental Model (Microlay Dental 3D Printers, Madrid, Spain), with a thickness of 385 - 405 nm. The digital models of maxilla and mandibula for participant 1 are shown in

Figure 4.

2.3.2. Manufacturing and Delivery of the PSPP

After printing the models, the cleaning and polymerization process continued. Cleaning was performed by placing the models inside an ultrasound device for 5 minutes, with 99% isopropyl alcohol. Once the cleaning procedure was complete, polymerization followed in the Otoflash G-171 n2 Photopolymerizer (Microlay Dental 3D Printers, Madrid, Spain), with nitrogen on the upper face of the model, and then repeating the process for the lower face of the model. The function of nitrogen is to prevent the printed model from coming into contact with oxygen during photopolymerization, thus eliminating the dispersion layer from the model’s surface.

The PSPP is formed of a body and a handle. For the body’s manufacturing, its base was created from the physical model using Dental Flux 060 Clear 1.5mm (Dentaflux, Madrid, Spain), with the help of a thermo-vacuum machine. The created base was then cut and smoothed manually. For the construction of the stimulating button, a self-polymerizing acrylic Weropress® (Merz Dental GmbH, Ladenburg, Germany) was applied to the PSPP’s base, with mechanical retention, and polymerized at 45 degrees Celsius, 25 minutes, and 2.35 bars of pressure (according to the manufacturer’s instructions). This procedure allows us to obtain the union between the self-polymerizing acrylic and the thermo-vacuum base plate. Both parts were then smoothed and shaped (

Figure 5). For the handle, the teat and rim of a conventional pacifier were cut, leaving the ring. A 1,75mm x 0.90mm orthodontic wire (Remanium®, Dentaurum GmbH Co., Ispringen, Germany) was bent, and mechanically inserted in the ring and onto the body. The wire was then coated with a self-polymerizing polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). For the final finishing of the PSPP, polishing with pumice stone and high-gloss paste specifically for acrylic was used.

The PSPP was delivered to each patient, with the recommendation to be used, at first, for short periods (i.e., five to ten minutes, twice to four times a day). As the child adapted to the device, we proposed to increase the time of use, to 15 to 60 minutes, four times a day. To get the most benefit from the PSPP, the suggestion was to use it as long as possible, including when the child sleeps, not exceeding the 15 hours of use per day.

Figure 6 illustrates the use of the PSPP.

2.3.3. Assessment of Oral-Morphological Features, Language Abilities, and Acceptability of the PSPP

During the time of infant use of the PSPP, video recordings were made of all the clinical cases in separate sessions, following accepted procedures in palatal plate interventions [

18,

20,

21,

30]. After an initial baseline session before use of the PSPP, the infant and parents were engaged in participating in monthly recording sessions that included 5-minute video samples of the infant without and with the PSPP, facing the camera, and in profile position, with the mouth area clearly visible. The recordings can be evaluated for the assessment of oral-morphological features, such as tongue position variables (intraoral, intermediate, extraoral) and mouth posture variables (closed, semi-open, open). Importantly, the recordings provided information on the time and frequency of use of the PSPP, and on infants’ and parents’ overall acceptability of the plate. When it was not possible to conduct a video recording, a contact was made by phone to collect the information.

After an initial baseline assessment before use of the PSPP, the developing language and communication abilities were assessed individually every three months, through the CSBS-DP Infant-Toddler Checklist and the CDI Short forms. The regular assessment of language abilities is an innovative feature of the present workflow, related to the potential impact of oral-motor problems in DS in the auditory-motor link behind speech perception and production. Parents were contacted to fill in electronic forms of the CDI and CSBS-DP, using secure web-based tools. Parents’ responsiveness to the language questionnaires was also taken as an indicator of the overall acceptability of the PSPP workflow.

Data analysis. Given that the aim of present report is to put forward a new digital workflow for the use of a modified SPP, we focused on those data variables that provided information on how safe, easy to implement and feasible the new workflow is, as well as on infants’ and parents’ acceptability of the PSPP workflow. Specifically, on the basis of data from the five clinical cases, we conducted a descriptive analysis of (i) the viability and acceptability of the mouth scanning, (ii) the speed of manufacturing the PSPP, and (iii) the acceptability of the PSPP by infants and parents. For (iii), we considered frequency and overall time of use of the PSPP, comments from parents, and their response rate to the follow up assessment sessions and questionnaires.

3. Results

The data for the relevant variables under analysis is given in

Table 1. Additional (raw) data is provided in the Appendix (

Table A1).

3.1. Mouth Scanning: Viability and Acceptability

All scans were performed in a single session and took, on average, 13.4 minutes to complete (

Table 1). The median scanning duration of the upper jaw was of 8.2 minutes and 5.2 minutes for the lower jaw. A major advantage of using intra-oral scanner technology was the receptivity of parents, given the low risks and infant-friendliness of the small IOS device. Nevertheless, the operator noted the following challenges: (i)The dimensions of the head of the scanner, although small, sometimes made it difficult to move on the small oral cavities of the infants under study; (ii) Children with DS present muscular hypotonia and a protruded tongue, which may add to the difficulty of maneuvering the head of the scanner; (iii) The increased salivary production characteristic of children with DS caused some interruptions in the scanning process, due to lack of reading by the scanner; (iv) The sucking or biting reflex combined with the rigidity of the scanner’s head occasionally led to minor and superficial injuries to the gingiva and pauses in the scanner’s reading.

The relatively short duration of the scanning facilitated both infant’s and parents’ collaboration. However, in the case of participant 2, due to a longer scanning time, the infant became irritable and cried, forcing the procedure to be interrupted so that the infant could be calmed down.

Despite the very young age of infants, the specific traits of this clinical population, and across participant variability, the use of the digital IOS device for mouth scanning was viable in all cases and reached good acceptability from infants and parents.

3.2. From Mouth Scanning to Delivery of the PSPP

The time between the scanning and the delivery of the PSPP was 19 days on average (

Table 1). This interval included all the exchanges between the Lisbon Baby Lab and the manufacturing lab, as well as the scheduling of the delivery according to parents’ and the pediatric dentist’s availability. The PSPP was well-adapted to the infant’s mouth in all cases. When placing the PSPP, at first, there was an automatic closure of the mouth and placement of the tongue inside the oral cavity in all children (

Table A1). Then, there was an increase in saliva production and consequent drooling. In the case of participant 5, this increase in salivation caused some gagging. After a few minutes of using the PSPP, participant 1 and participant 2 began to induce vomiting, in an attempt to remove the PSPP. This reaction was later stopped after calling the child’s attention not to do so. Importantly, after 5 minutes of use, all infants showed good adaptation and acceptance of the PSPP. The same reaction was observed from the parents.

3.3. Acceptability of the PSPP by Infants and Parents

Frequency and overall time of use of the PSPP are reported in

Table 1, by participant. The overall time of use varied between 6 and 11 months, and the frequency of use per day from 5 to 15 minutes to 1 to 6 hours.

Participants 2, 3 and 5 discontinued PSPP use due to eruption of primary teeth and consequent misfit of PSPP, allowing the infant to remove it. For Participants 1 and 4, the first PSPP became unfitted due to the transverse growth of the upper jaw and consequent easiness to remove the “pacifier”, as well as primary teeth eruption. A second dental scanning was conducted and a second PSPP manufactured, as both the child and the parents were willing to continue PSPP use. Additionally, for Participant 4, in a subsequent appointment it was necessary to wear the acrylic, with a drill, in the eruption area of the first upper molars. This allowed for a complementary use for two more months.

The workflow of PSPP use included periodic contacts and response to questionnaires. Parents were very responsive to the monthly contacts, and the request to fill in the language questionnaires every 3 months, as shown in

Table 1. The rate of parents’ response to follow up contacts was calculated considering the number of contacts divided by the total duration of PSPP use in months. The mean response rate to all contacts (by phone and video) was 94%, with all participants above 75% and four above 90%. However, it was not always possible to carry out video sessions, and the mean response rate to the video contacts was lower (67%), with large variation across participants. Participant 3 only completed half of the video sessions, whereas participant 1 completed more than 4/5 of the sessions.

To compute the response rate to questionnaires, a denominator was obtained by the division of the total duration of PSPP use in months by three, given that responses were requested every 3 months. The rate of parents’ response to the language questionnaires was then calculated considering the number of questionnaires completed divided by this denominator. Both the CSBS-DP and the CDI had a 100% response rate (

Table 1). For participants 2, 3 and 4, parents provided more responses than those strictly required (

Table A1), as they sometimes showed willingness to respond to the questionnaires next to a phone or video call.

4. Discussion

Overall, the mouth scanning procedures, delivery and use of the PSPP were well accepted by both infants and parents. The feasibility of the workflow allowed plate adjustments and additional scans to produce newly adjusted PSPPs, thus extending the total duration time of their use. Parents’ response to the follow up assessments was generally high, also indicating that the proposed workflow was viable for very young infants with DS.

The use of SPP to improve mouth closure and tongue protrusion in children with DS, aiming to prevent secondary orofacial pathology associated with chronic tongue protrusion, is well documented in the literature [

8,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

27]. The high acceptability of the workflow proposed in this study is thus a welcome contribution to support the use of SPP, especially in infants with DS.

The introduction of the PSPP, used in the current study, provided a sense of security for parents/guardians, which allowed for an increased usage time, including during sleeping time. Additionally, the pacifier terminal favored lip sealing. Thus, the previously reported distinctive features of the PSPP [

21,

22] were confirmed in our study. Notably, after the PSPP delivery session, parents/guardians showed no concerns during the use of the plate.

In our study, there were some interruptions in the use of the PSPP related to factors such as periods of illness of the infant, the eruption of primary teeth and temporary rejection of the PSPP by the child. It is known that children with DS are predisposed to a number of medical conditions that may manifest as frequent health problems and/or increased risk of recurrent episodes of illness and infections [

31], and this was also observed in our study leading to occasional discontinuation of PSPP use. Dental eruption has been reported to cause difficulties in SPP retention [

18]. Eruption of the primary teeth in individuals with DS is usually delayed with the first tooth often appearing between the ages of 12 and 14 months [

1]. With the infants with extended use of the PSPP in our study, parents reported difficulties with the PSPP when teeth started to erupted. Moreover, as the nervous system matures and the child gets older, the tongue gains the ability to move more [

32]. This improves the child’s capability to expel the SPP, making its use more difficult and reducing the time of use, as also observed in our study.

For the construction of the palatal plate, it is necessary to make impressions of the edentulous dental arches, which are conventionally done using impression materials like alginate or elastomers, often associated with complications such as increased risk of accidental ingestion, aspiration, and suffocation. Introducing the intraoral scanner to acquire models of dental arches, as it was done in the present study, eliminates these risks, offering a more suitable alternative. We only registered a small superficial lesion to the gingiva during mouth scanning in one of the participants. This is in line with results from studies using intraoral scanners in neonates and infants with craniofacial disorders [

26]. However, it is recommended to use a scanner design that is well adjusted to the characteristics of the participants, to further improve their safety.

The use of intraoral scanners for constructing the SPP, as proposed in the current workflow, is also supported by studies showing that intraoral digital impressions are sufficiently accurate for fabricating scaffolds, retainers, and miniature connectors, and that they provide accurate width’s measurement of alveolar arch and cleft defects [

25,

33,

34]. Nevertheless, compression differences between digital and plaster models in the soft palate and buccal vestibule areas were found in these studies, suggesting the need to further improve the accuracy of intraoral scanners.

The duration of the scanning procedure is a further sensitive feature. In our study, the scanning duration of the maxilla was on average 482 seconds (8.2 minutes). In previous studies, different findings have been reported, with a median scanning duration of the upper jaw, for children with DS, of 129.5 seconds, or a mean scanning time of 10.74 to 17.83 minutes in typically developing children, depending on the intraoral scanning procedure implemented [

26,

34]. Although differences in the scanners used and methodological procedures across studies might play a role, it is generally recognized that intraoral scanning of younger patients is a complex procedure, because of difficulties in manoeuvre of the scanner head, leading to longer scan duration. Moreover, oral scanning in children with DS presents additional difficulties because of the hypotonic muscles, protruded tongue, and hypersalivation [

35,

36]. Considering all these factors, the scanning duration results obtained in our study are suggested to reflect a further strength of the proposed workflow. Still, further improvements in intraoral scanning technology could be directed to provide a better response to these obstacles.

In addition to the results from the scanning and PSPP use, the viability and acceptability of the proposed workflow was also reflected by the response to the follow up sessions and language assessment questionnaires. Periodic video recordings of the clinical cases are a common procedure in palatal plate interventions [

18,

20,

21]. We aimed at monthly video recordings, and the lowest response obtained was from one participant that completed half of the video sessions. Given that many studies have used less stringent criteria, with recordings in intervals of 3 months (e.g., [

20]), the rate of response obtained aligns with acceptable practices allowing the assessment of oral-morphological variables through video registration. Unlike the evaluation of oral-morphological variables, which is standard practice in SPP interventions, the implementation of a procedure that allows the assessment of language and communication abilities is a novel feature of the proposed workflow. Parental response rate to the language questionnaires was 100%. This highly successful procedure will allow the evaluation of the impact of the PSPP on infants’ developing speech perception and speech production abilities. This is an important outcome, which goes along the lines of recent research on the auditory-motor link in infancy that suggests that oral-motor impairments constrain both the perception and production of speech [

15,

37].

Despite the promising viability and acceptability of the proposed workflow, the current study has limitations that call for further investigation. Future research should apply the workflow to larger samples, and compare the results across different intraoral scanner operators. Ways to improve intraoral scanner technology for younger patients and challenging clinical populations should also be explored. Importantly, as the new workflow is applied in interventions with more children, future research needs to determine its effects on oral morphology and auditory-motor language abilities in infants with DS, and progressively adjust the workflow to improve the effects obtained.

5. Conclusions

The current study underscores that the proposed digital workflow constitutes a viable and infant-friendly approach to the production and use of the PSPP device. The low risks and ease of implementation of the proposed workflow are suggested to promote the generalized use of therapeutic interventions with a modified SPP, a step forward in the treatment and prevention of oral-motor dysmorphologies in infants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.V., D.C.A & S.F.; Methodology: M.J.C., D.C.A & S.F.; Validation: D.C.A & S.F.; Formal analysis: M.J.C. & S.F.; Investigation: M.J.C., C.S. & J.P.; Resources: M.P. & S.F. ; Data Curation: M.J.C., C.S.; Writing—original draft preparation: M.J.C. & S.F. ; Writing—review and editing; M.J.C., D.C.A & S.F.; Supervision: D.C.A & S.F.; Project administration: M.V. & S.F.; Funding acquisition: S.F.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (P2LINK Project, PTDC/LLT-LIN/1115/2021,

https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/LLT-LIN/1115/2021 (PI, S.F.); UID/00214/2025: Centro de Linguística da Universidade de Lisboa).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon (protocol code 19_CEI2021, date of approval 16 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents or legal guardians before the study.

Data Availability Statement

Given the restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee, the detailed data from this study are available from the corresponding author, S.F., upon request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of the Center for Child Development Diferenças in the recruitment of participants, and the help of the research assistant Nuno Paulino with data collection. We thank the infants and their parents who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DS |

Down Syndrome |

| SPP |

Stimulating palatal plate |

| PSPP |

Pacifier stimulating palatal plate |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Additional variables for evaluating the viability and acceptability of the PSPP workflow: raw data.

Table A1.

Additional variables for evaluating the viability and acceptability of the PSPP workflow: raw data.

| Participants |

Delivery session |

Successful follow up contacts |

Successful video sessions |

Parents reaction / feedback to PSPP use |

Parents response to CSBS |

Parents response to CDI |

| Participant 1 |

Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. Initially tried to remove the PSPP, inducing vomiting. |

10 |

9 |

Very positive. Parents requested a second PSPP. |

4 |

4 |

| Participant 2 |

Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. Initial adaptation difficult. Induced vomiting. Parents aprehensive. |

8 |

4 |

Parents wanted to stop PSPP use after 6 months. |

5 |

5 |

| Participant 3 |

Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted |

10 |

5 |

Very positive. |

3 |

7 |

| Participant 4 |

Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted. An adhesive was used for fixation. |

12 |

7 |

Very positive. Parents requested a second PSPP. |

4 |

8 |

| Participant 5 |

Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted. Initially, increased saliva and gagging. |

7 |

6 |

Very positive. |

3 |

3 |

References

- Macho, V.; Coelho, A.; Areias, C.; Macedo, P.; Andrade, D. Craniofacial Features and Specific Oral Characteristics of Down Syndrome Children. Oral health and dental management 2014, 13, 408–411.

- Sperling, K.; Scherb, H.; Neitzel, H. Population Monitoring of Trisomy 21: Problems and Approaches. Molecular Cytogenetics 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, C.J. The Consequences of Chromosome Imbalance. American journal of medical genetics. Supplement 1990, 7, 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, L. Global, Regional, and National Burden and Trends of Down Syndrome From 1990 to 2019. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mai, C.T.; Isenburg, J.L.; Canfield, M.A.; Meyer, R.E.; Correa, A.; Alverson, C.J.; Lupo, P.J.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Cho, S.J.; Aggarwal, D.; et al. National Population-Based Estimates for Major Birth Defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Research 2019, 111, 1420–1435. Epub 2019 Oct 3. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Births with Down’s Syndrome per 100 000 Live Births Available online: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_603-7120-births-with-downs-syndrome-per-100-000-live-births/#id=21649 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Díaz-Quevedo, A.A.; Castillo-Quispe, H.M.L.; Atoche-Socola, K.J.; Arriola-Guillén, L.E. Evaluation of the Craniofacial and Oral Characteristics of Individuals with Down Syndrome: A Review of the Literature. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021, 122, 583–587. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.M.M.M.; Almeida, T.D.D.; Pretti, H. Effects of Using the Stimulating Palatal Plate in Combination with Orofacial Stimulation on the Habitual Tongue and Lip Posture in Children with Trisomy 21: An Integrative Literature Review. Revista CEFAC 2022, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, N.; Kaczorowski, K.; Laskowska, J.; Mikulewicz, M. Down Syndrome as a Cause of Abnormalities in the Craniofacial Region: A Systematic Literature Review. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2019, 28, 1587–1592. [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Hedge, S.; Naik, S.; Shetty, P. Malocclusion in Down Syndrome - a Review. The South Africa Dental Journal 2015, 70, 12–17.

- Barnes, E.F.; Roberts, J.; Mirrett, P.; Sideris, J.; Misenheimer, J. A Comparison of Oral Structure and Oral-Motor Function in Young Males with Fragile X Syndrome and Down Syndrome. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR 2006, 49, 903–917. [CrossRef]

- Abbeduto, L.; Warren, S.F.; Conners, F.A. Language Development in Down Syndrome: From the Prelinguistic Period to the Acquisition of Literacy. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews 2007, 13, 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.D.; Eichhorn, J.; Wilson, E.M.; Suk, Y.; Bolt, D.M.; Vorperian, H.K. Auditory-Perceptual Features of Speech in Children and Adults With Down Syndrome: A Speech Profile Analysis. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR 2021, 64, 1157–1175. [CrossRef]

- Strome, S.E.; Strome, M. Down Syndrome: An Otolaryngologic Perspective. The Journal of Otolaryngology 1992, 21, 394–397.

- Choi, D.; Yeung, H.H.; Werker, J.F. Sensorimotor Foundations of Speech Perception in Infancy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2023, 27, 773–784. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Morales, R.; Brondo, J.; Høyer, H.; Gj, L. [Treatment of Chewing, Swallowing and Speech Defects in Handicapped Children with Castillo-Morales Orofacial Regulator Therapy: Advice for Pediatricians and Dentists]. Zahnarztliche Mitteilungen 1985.

- Limbrock, G.J.; Castillo-Morales, R.; Hoyer, H.; Stöver, B.; Onufer, C.N. The Castillo-Morales Approach to Orofacial Pathology in Down Syndrome. The International journal of orofacial myology : official publication of the International Association of Orofacial Myology 1993, 19, 30–37.

- Carlstedt, K.; Henningsson, G.; McAllister, A.; Dahllöf, G. Long-Term Effects of Palatal Plate Therapy on Oral Motor Function in Children with Down Syndrome Evaluated by Video Registration. Acta Odontol Scand 2001, 59, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Ferreira, J.E.; de Almeida, B.R.S.; Deps, T.D.; Pretti, H.; Furlan, R.M.M.M. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy Associated with the Use of the Stimulating Palatal Plate in Children with Trisomy 21: Case Studies. CODAS 2023, 35, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Carlstedt, K.; Henningsson, G.; Dahllöf, G. A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of Palatal Plate Therapy in Children with Down Syndrome: Effects on Oral Motor Function, Articulation and Communication Preferences. Acta Odontol Scand 2003, 61, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.J.C. de A. Trissomia 21–Estudo Dento-Maxilo-Facial, School of Dentistry - University of Oporto: Porto, 2000.

- Andrade, David Casimiro Placa Palatina Modificada Sob a Forma de Chupeta 2004.

- Chate, R.A.C. A Report on the Hazards Encountered When Taking Neonatal Cleft Palatal Impressions (1983-1992). British Journal of Orthodontics 1995, 22, 299–307.

- Behera, S.; Prakash, N.; Galagali, G.; Reddy, E.S.; Devasya, A.; Nidawani, M. Oral Molding Plates a Boon to Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Patients: A Series of Case Reports and Review. International Journal of Preventive & Clinical Dental Research 2014, 1, 31–35.

- Okazaki, T.; Kawanabe, H.; Fukui, K. Comparison of Conventional Impression Making and Intraoral Scanning for the Study of Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate. Congenital Anomalies 2023, 63, 16–22. Epub 2022 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Weise, C.; Frank, K.; Wiechers, C.; Weise, H.; Reinert, S.; Koos, B.; Xepapadeas, A.B. Intraoral Scanning of Neonates and Infants with Craniofacial Disorders: Feasibility, Scanning Duration, and Clinical Experience. European Journal of Orthodontics 2022, 44, 279–286. [CrossRef]

- Limbrock, G.J.; Fischer-Brandies, H.; Avalle, C. Castillo-Morales’ Orofacial Therapy: Treatment of 67 Children with Down Syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1991, 33, 296–303. [CrossRef]

- Filipe, M.G.; Severino, C.; Vigário, M.; Frota, S. Adaptation and Validation of the European Portuguese Communication and Symbolic Behaviour Scales Developmental ProfileTM (CSBS DPTM) Infant-Toddler Checklist. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2024, 59, 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Frota, S.; Butler, J.; Correia, S.; Severino, C.; Vicente, S.; Vigário, M. Infant Communicative Development Assessed with the European Portuguese MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventories Short Forms. First Language 2016, 36, 525–545. 10.1177/0142723716648867.

- Javed, F.; Akram, Z.; Barillas, A.P.; Kellesarian, S.V.; Ahmed, H.B.; Khan, J.; Almas, K. Outcome of Orthodontic Palatal Plate Therapy for Orofacial Dysfunction in Children with Down Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Orthod Craniofac Res 2018, 21, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Sheets, K.B.; Best, R.G.; Brasington, C.K.; Will, M.C. Balanced Information about Down Syndrome: What Is Essential? Am J Med Genet A 2011, 155A, 1246–1257. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B.R.S. de; Ferreira, J.E. de A.; Almeida, T.D.D.; Pretti, H.; Furlan, R.M.M.M. Influência da idade e do tempo de uso da Placa Palatina de Memória por crianças com Trissomia do 21 nas mudanças miofuncionais orofaciais percebidas pelos pais, na adaptação e satisfação da família após quatro meses de tratamento. Distúrbios da Comunicação 2023, 35, e55472–e55472. [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Qiu, P.; Xu, H.; Cao, Y. Accuracy of Intraoral Scanning versus Conventional Impressions for Partial Edentulous Patients with Maxillary Defects. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Burhardt, L.; Livas, C.; Kerdijk, W.; van der Meer, W.J.; Ren, Y. Treatment Comfort, Time Perception, and Preference for Conventional and Digital Impression Techniques: A Comparative Study in Young Patients. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2016, 150, 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Benitez, B.K.; Brudnicki, A.; Surowiec, Z.; Wieprzowski, Ł.; Rasadurai, A.; Nalabothu, P.; Lill, Y.; Mueller, A.A. Digital Impressions from Newborns to Preschoolers with Cleft Lip and Palate: A Two-Centers Experience. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 2022, 75, 4233–4242. [CrossRef]

- Xepapadeas, A.B.; Weise, C.; Frank, K.; Spintzyk, S.; Poets, C.F.; Wiechers, C.; Arand, J.; Koos, B. Technical Note on Introducing a Digital Workflow for Newborns with Craniofacial Anomalies Based on Intraoral Scans - Part I: 3D Printed and Milled Palatal Stimulation Plate for Trisomy 21. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, P.K. Infant Speech Perception. In Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2021; pp. 113–158 ISBN 978-1-119-68452-7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).