1. Introduction

The relationship of indigenous peoples with nature is a spatially and temporally heterogeneous phenomenon [1] that includes ontological and worldview dimensions [2]. Indigenous peoples’ contribution to the conservation of ecosystems [3], including marine-coastal environments [4], has been globally recognized, to the extent that the United Nations recommends safeguarding indigenous customs for the sustainability of the planet in its Aichi Target No. 18 [5]. However, indigenous populations continue to be left out of decisions affecting their own territories and waters [6] and impacted by socio-environmental conflicts arising from the industrial use and overexploitation of those spaces [7].

The central role that indigenous communities play in maintaining ecosystems is based on customs [2] (that promote practices of care and respect for spaces, species, and ecosystem functions [8,9]. Those customs developed from these communities’ prolonged interaction with nature, enabling them to accumulate knowledge and reinforce it over time through cultural practices [10], and they are underpinned by ontological (that is, what are the things that populate the world, [11] and—just as important—cosmogonic considerations (that is, what can and should be done with the things that populate the world, [2]. This relationship between ontology and cosmovision is crucial, as it highlights the tremendous ontological/cosmogonic gap that exists between indigenous peoples and other actors that impact the territories where indigenous communities live their lives [12]. This is evident in their different ways of looking at nature: for communities with indigenous ontologies and world visions, animals, plants, rocks, rivers, wetlands, and the sea (among many other elements of the natural world) are respected as part of a web of interdependent relations that are essential to one's own well-being, and some of them are perceived as entities that must be respected, including those that are seen as protectors [13]; for other actors, however, these elements are considered almost exclusively as resources intended for exploitation. The ontological/cosmogonic dimension provides a foundation for what can and should be done with and within the natural world (as a collective agreement regulated by custom), leading to concrete outcomes such as healthy or degraded territories [9]. It is important to note that simply being an indigenous community, or practicing indigenous customs, does not guarantee this relation of care [2], and thus it is also possible for non-indigenous communities to engage in customs of care with the natural world (Op cit.). This study therefore seeks to identify the customs that produce a healthy natural world, specifically in a coastal environment with the potential for such.

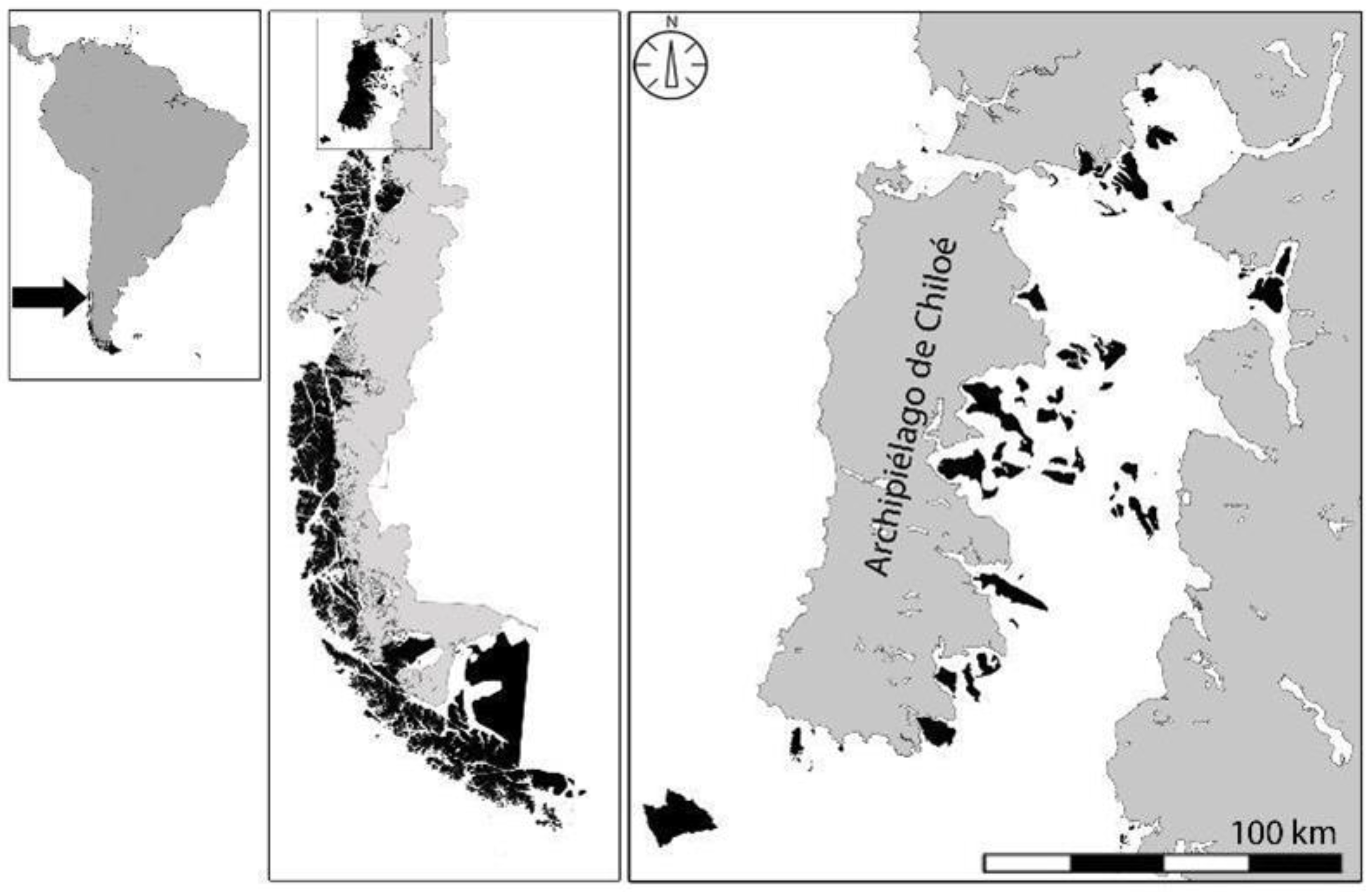

To this end, we focused on the waters of the Chiloé Archipelago (

Figure 1) in southern Chile (41°28'22.63 "S/ 73°26'23.15 "W), home to

Williche ('People of the South') indigenous communities, whose customs have been documented as having an ancestral relationship of care with the marine-coastal environment [14], under a framework of relational valuation with these coastal ecosystems [15]. These

Williche communities form part of an extensive cultural mosaic that also includes the Mapuche people ('People of the land'), and are considered "ecosystem people" due to their ongoing reliance on nature for subsistence (Guha and Gadgil, 1989, cited by [15]), in what has been called a traditional island-based way of life [16]. This way of life is enmeshed in a complex scenario involving multiple users and uses, some mutually incompatible, including many linked to the current model of overexploitation of nature, whether extractive (such as large fishing fleets and their ongoing episodes of extractive fever) or productive (such as salmon farms and their regular socio-environmental disasters) [17,18].

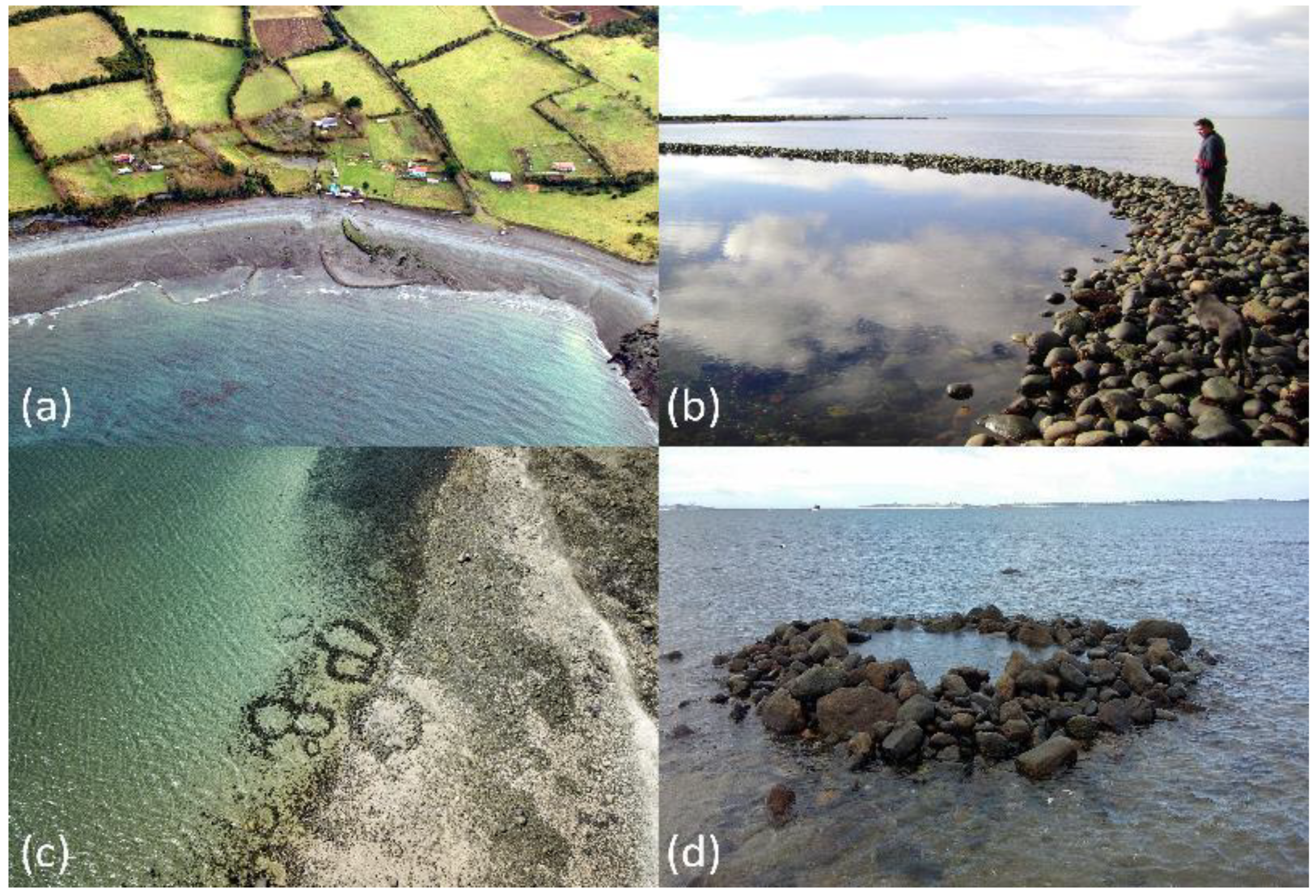

This study focuses on the insular context, as we consider islands to be socio-ecological systems [19] with limited ecosystem functions [15,20]. In this limited archipelagic context, the way people live has particular, and very evident, consequences on the environment, rapidly triggering socioecological changes; it is this quality that makes them highly sensitive territories [21]. These ways of life—which reflect particular, differentiated ontologies and cosmovisions—develop in intimate interrelationship with the island environment, with the resulting customs influencing local ecosystems [22,23]. In effect, different ways of life produce territories that are very different from one another [24]. Many traditional marine activities centre around the vast intertidal zone generated by the gently sloping seabed and the resulting huge intertidal range, in which the shoreline is not a sharp boundary that divides land and sea [25,26]. In our study, we place special emphasis on the intertidal and the beach because they present both terrestrial and underwater conditions in everyday life of these traditional communities, allowing us to observe how different ways of life produce different beaches and intertidal zones (

Figure 2).

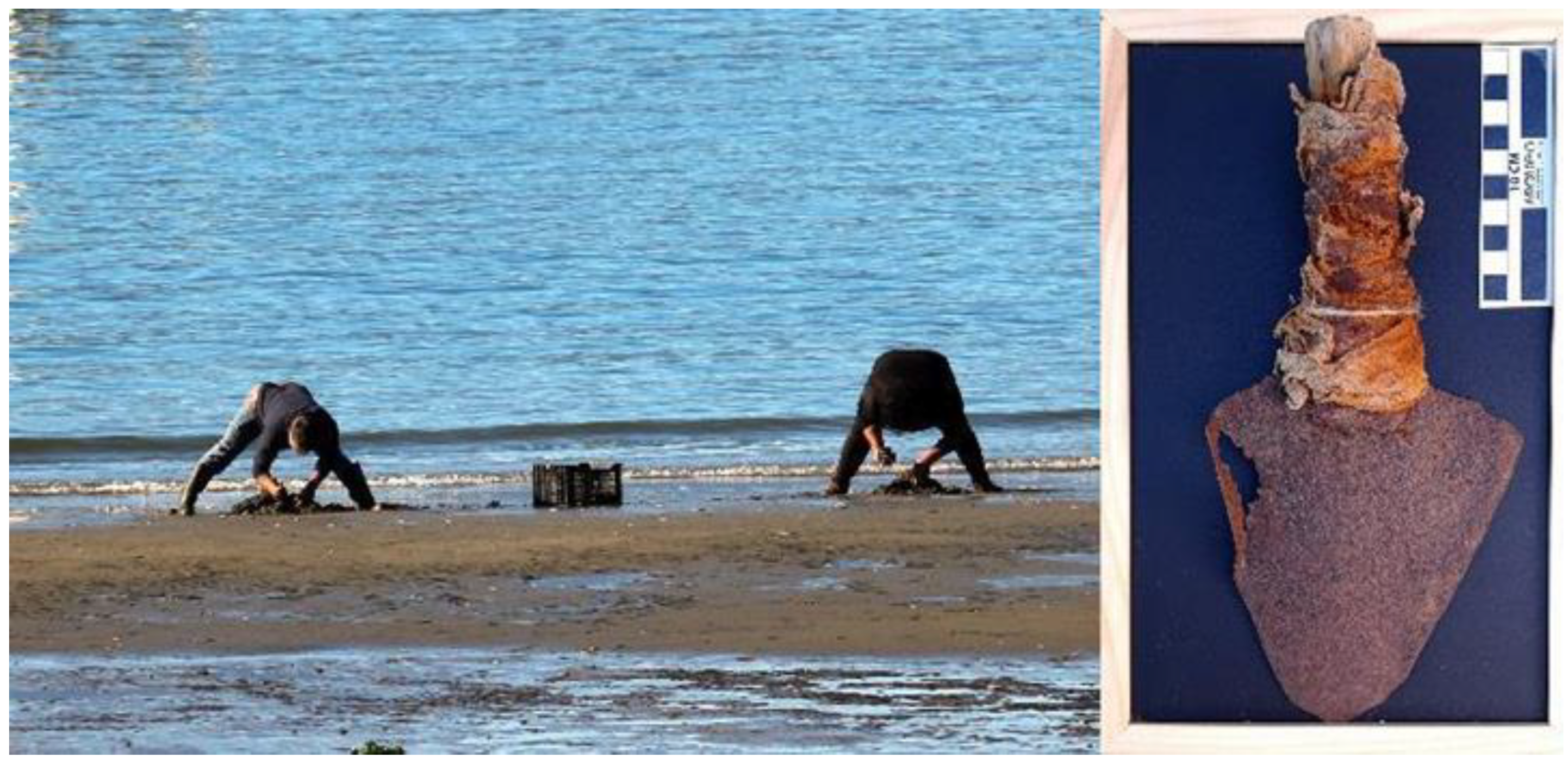

The beach is a very important social space, while the intertidal zone yields two unique times and spaces: at high tide, the people engage in shore fishing, and at low tide they practice shoreline harvesting of crustaceans, seaweed, and even small rockfish, making this space/time particularly relevant for the traditional coastal economies of the archipelago. Traditional medicines are also collected in this time/space. This transitional space/time has been marked by functional human-built structures (to support fishing and gathering, among other activities) that evidence the locals’ collective co-management of the beach. But this space/time is also occupied by indigenous regulatory entities that wield significant agency over the social life between humans and non-humans [27,28,29]. These regulatory entities are not part of the worlds of other territorial actors that also use these spaces and times (such as small-scale fishing fleets and the aquaculture industry). Rather, we consider these entities to be a major variable in identifying an ontology / cosmovision / practice that can protect the beach from those other ontologies / cosmovisions / practices occurring at the same time. Why? Because they demand that people respect certain taboos and other traditional ethical-normative restrictions (of ancient indigenous origin), encouraging them to collectively engage in such crucial practices as not extracting more than necessary, not competing with others, leaving small specimens (traditionally called 'seed') and breeding grounds (called 'seedbeds’ by locals) alone, and never fighting with their neighbours, among other relational principles. Obeying the wishes of these entities will stimulate the vitality of the shore (including the sea), while violating their restrictions will cause the opposite, leading to environmental deterioration, poverty, and scarcity [30].

In contrast, the actions of the other territorial actors that use the beach and the intertidal at the same times are based on principles such as mutual competition, the exploitation or altering of ˈseedsˈ and ˈseedbedsˈ (places where some species reproduce intensively), and the individual accumulation of species and spaces by excluding other harvesters. At the same time, their actions are transferred to their surroundings as spaces that show serious environmental damage, with biodiversity loss and the emergence of socio-environmental conflicts [9]. In this document, we investigate the ontological and cosmogonic substrate that supports collective decision-making on how people should relate to each other and with other species and natural spaces, with emphasis on the intertidal and the beach zones. We hope not only to shed light upon the importance of customs and their cosmogonic-ontological substrate, but also to raise awareness among State and industry actors, to encourage them to change the way our country’s current development model is being implemented on our coasts and, especially, the sensitive and vulnerable intertidal zone.

1.1. Archaeological and Historical Background: the Inhabitants of the Northern Channels

The northern Patagonian archipelago (~41°30' - 47° S) covers an extensive geographical area that includes more than 100,000 km of shoreline and 40,000 islands and islets [31], interrupting the lengthy Pacific Ocean coast with major biogeographic discontinuities such as channels and fjords, among others [32]. Human occupation of the coasts of these northern channels, including the Chiloé Archipelago, Reloncaví Sound, and the Chono-Guaitecas Archipelago, stretches back to ca. 6000 B.P., when marine hunter-gatherer groups called canoeros because of their canoe-faring way of life inhabited the zone [33,34,35]. The areas studied here offered optimal conditions for the early development of human groups adapted to a maritime environment, given that at the time of the last glaciation, the northwest coast of Chiloé was a relictual zone free from the ice of the previous glacial advance, making it available as a maritime habitat from that time forward. However, the extremely complex geomorphology and intense, unstable geodynamics after the ice retreated, among other factors, have made it difficult to model human occupations of that initial exploration and settlement period, given the challenge of identifying ancient coastlines and potential human occupations during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition [36].

More amenable climatic conditions and the attendant increase in available food resources in the area during the Late Holocene would have increased the human population, encouraged more intense mobility that allowed groups to become more familiar with the region, and led to the arrival of new groups from the northern part of the continent, among others [36].

The territory comprising mainland and archipelagic Chiloé was gradually occupied by societies of Williche origin that were semi-sedentary, cultivating crops and raising camelid livestock, yet also practicing maritime hunting and gathering. As these groups arrived, the early canoe-faring peoples continued their way of life in parallel, with some important modifications, such as the incorporation of horticultural practices [36]. This change coincided with the introduction of ceramics and the initial adoption of a mixed lifestyle balanced quite evenly between maritime and terrestrial activities; practices present since the Middle Holocene, such as the use of curantos and fish weirs continued, and over time have even become characteristic of the regional culture. The Williche presence prevailed on the big island of Chiloé and the northern channels, where those groups inherited and incorporated much of the knowledge and culture of the canoe-faring peoples [32,36].

The fish weirs consisted of stone walls and/or fences made of intertwined branches, nets, or other material to allow fish to enter during high tide and then trap them inside when the tide went out. They are especially abundant in this zone, with more than a thousand structures currently on record, scattered among the islands and the mainland coast [37]. In order to build and use these fish weirs effectively, the people would have required direct knowledge of the environment, its available resources, the ocean tides, and the behaviour of the ichthyological fauna. As a legacy of the past, they are an indicator that these peoples were culturally adapted to coastal environments and developed an efficient technique for extracting this type of food, that may have required a high initial investment of labour to build the structures but needed minimal day to day care thereafter. The use of these fish weirs was also regulated by ethical and normative restrictions on fishing intensity, as well as by procedures for distributing the catch [38]. Today, the

Williche communities living in Chiloé consider these fish weirs to be part of their identity, making the technique indigenous in origin, as recent archaeological studies have confirmed [39]; however, numerous historical records also point to their Hispanic-colonial origin, which would make them an example of historical mestizaje in the zone [38]. Today,

Williche communities consider these fish weirs and similar structures such as

cholchenes (

Figure 3) to be part of their culture, and accompany them with rituals and beliefs around their construction and maintenance, reinforcing the view that they have been used by this people since pre-Hispanic times.

Although many archaeological structures are currently located in the intertidal zone, not all of them are in use permanently or seasonally. Their use nowadays is influenced on the one hand by changes in ways of life and the abandonment of long-standing customs and their replacement with new techniques and technologies; and on the other by variations in the coastline since the weirs were constructed. The latter changes are due to marine transgressions and regressions, or to tectonic forces such as the subsidence that occurred at the centre of the northern archipelago during the 1960 earthquake, where the land in this island territory dropped by 1 to 2 meters, repositioning the archaeological stone fish weirs away from their original location. This has made it possible to distinguish pre-Colombian weirs, cholchenes and other intertidal structures from more recent ones, based on their position relative to the tides and access at low tide [40].

1.2. Area of Study

This study was conducted in the Chiloé Archipelago (41°28'22.63 "S/ 73°26'23.15 "W), located in southern Chile. This archipelago is composed of some fifty inhabited islands and is part of the northern archipelagos of the marine and coastal region of Chilean Patagonia. In this study, emphasis is placed on the smaller islands (i.e., less than 80 km2 in area; Map 1) in order to situate our reflections within a traditional island-based way of life that is especially evident there, and which is represented by Williche indigenous communities and local non-indigenous Chiloé communities [16]. Approximately 170,000 people live in the entire Chiloé Archipelago [41], only 12,000 of them on its smaller islands. This distinction is important because the latter practice a traditional campesino-gathering-fishing way of life with very low environmental impact [42] and continue to engage in longstanding customs of indigenous and mestizo origin [30]. Of particular interest among these customs are those of Williche origin that are practiced on beaches and in the intertidal (such as pedestrian shoreline shellfish and seaweed gathering), and the material culture associated with them, such as the thousand-plus stone fish weirs recorded to date in this archipelago [37] and the innumerable cholchenes used for raising shellfish near family dwellings that also lie in the intertidal.

Families on these smaller islands live dispersed from one another, in an archipelagic environment with limited ecosystem functions. For this reason, their social bonds and cultural practices tend to foster mutually supportive relationships, minimizing opportunities for competition and conflict over local resources [9]. Their social practices therefore often have more than one purpose: for example, the custom of shellfish (or seafood) gathering is not only aimed at obtaining food (and/or resources to sell), but also reinforces the local social structure [30,42,43]. The islands’ economy is based on three main activities: 40% of labour is focused on subsistence farming, 22% on shoreline seaweed harvesting (along the beach) for sale as raw material, and 15% on artisanal fishing (benthic- diving for shellfish, and demersal- taking advantage of bottom-feeding schools of fish) for sale as raw material [43]. A very small percentage of the population is engaged in off-island salaried work (in the salmon industry, for example) or weekly sales of marine and horticultural products at urban markets, and another small proportion of income is obtained from state pensions received mainly by elderly islanders (Op cit.).

A variety of collective activities take place on the beach and in the intertidal, such as the aforementioned collection of seaweed and shellfish, as well as shore fishing and seaweed drying. This is also where local families launch and beach their boats, store their work tools, and hold religious celebrations and rituals, among other family and community activities. These are not only shared spaces [44]; they are also the focal point for common social practices [45], such as collective decision making around their access and use, based on the local inhabitants’ ontology and cosmovision. At the same time, however, Chilean legislation operates here, in the form of regulations for private and public access and use that govern the actions of registered artisanal fishermen and productive industries. These other regimes of use differ markedly from the communal ones on the island, as they allow competition among peers and private accumulation, and are commonly linked to overextraction and/or coastal pollution [9,30].

The intertidal zone in these islands is very dynamic, with islands such as Llingua, in Quinchao Municipality, oscillating daily between 3.32 km2 and 4.76 Km2 in area and 9.27 km and 13.1 km in perimeter at high and low tides, respectively. This means that those who live there have an additional 1.44 km2 of area and 3.83 km of perimeter to carry out their various activities (

Figure 4(a)), the difference between the high and low tide lines is outlined in yellow), and adherence to the lunar cycle produces biocultural calendars in which the activities of humans and other species are interdependently organized [46]. Almost all of the smaller islands have sandy beaches and mudflats (

Figure 4(b)) as well as pebble beaches with rocky outcrops (

Figure 4(c)), providing access to different species of seaweed, fish, and shellfish. The former also allow the community to cultivate seaweed such as

pelillo (

Agarophyton chilense). Of particular relevance in this environment are

bajeríos (Sic.) (

Figure 4(c)), areas that outcrop only at exceptionally low tides that are traditionally recognized and valued for being highly productive. These are used collectively, with ethical and normative arrangements in place to discourage individual hoarding, competition, and over-extraction that could cause ecological damage. But that same abundance exposes these areas to overexploitation by artisanal fishing fleets that also use them as part of the State-regulated free access regime, and by intensely competitive divers who extract resources from these shallows when they are submerged.

Lastly, the beach, or the space above the high tide line, is also an area under collective use that is governed by ethical-normative arrangements that limit opportunities for exclusion and privative monopolization. Here there are multiple smaller structures called

rukos or

ranchas, (Sic.), family-owned structures that are respected by others, where they mainly store tools used primarily for harvesting and shore fishing, but sometimes also use them as seasonal lodging. Families even bring farm animals such as pigs and chickens and pets such as dogs and cats with them when they come to do seasonal work such as seaweed harvesting (especially the algae called

alga luga (

Sarcothalia crispata and

Gigartina skottsbergii) (

Figure 5(a)). Items such as sleds (

trineos or

virloches) (Sic.) pulled by animals, a medieval European invention, are used for their low impact on the intertidal substrate instead of motorized vehicles, which destroy shellfish beds (

Figure 5(b)). The beaches in question are often used during the summer months for seaweed drying (

Figure 5(c)).

1.3. Legal Regulations and Indigenous Peoples

Since the early 1990s, Chile has enacted legislation on the protection of indigenous peoples, the first of which was Law 19,253 in 1993 on the Promotion, Protection and Development of Indigenous Peoples, commonly called the "Indigenous Law". In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly, including Chile, adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). This document directly recognizes that indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination and, on this basis, to establish their political status within the State and to freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development. In addition, it recognizes that indigenous peoples have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters related to their internal and local affairs, such as expressing their customs, ontologies, epistemologies, and cosmovisions.

In the broader context, International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169 of 1989 (hereinafter Convention 169) was ratified by Chile in 2008 and recognizes indigenous peoples’ rights over their lands and territories, establishes mechanisms for their political participation (indigenous consultation), and recognizes their right to define their development and to exercise progressive control over health and education programs intended for them, among other matters. One of Convention 169’s articles affirms that "Governments shall have the responsibility for developing, with the participation of the peoples concerned, co-ordinated and systematic action to protect the rights of these peoples and to guarantee respect for their integrity." In 2016, this declaration was joined by the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (ADRIP), which establishes, among other things, "the right to the recognition, observance, and enforcement of treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements concludes with States...” Of particular importance to our case study is the Lafkenche Law (No. 20249), enacted in Chile in 2008. This Law creates Indigenous Peoples' Marine Coastal Spaces (ECMPO in Spanish) to recognize and protect the customary uses of indigenous communities in the coastal zone. Customary use is understood as those practices or behaviours that communities engage in on a regular basis as part of their culture, including religious, economic, and recreational customs, among others. These spaces are managed by the communities and are crucial for the preservation of their traditions and ecosystems. They also allow greater regulatory control over other extractive and productive uses [47].

In relation to our study, it is important to note that in 1998, Chile explicitly defined and incorporated Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) into its legal heritage framework through MINEDUC Decree of Exemption 311, giving UCH the status of historic monument under Law No. 17,288 on National Monuments. Under this decree, all evidence of human existence submerged in the seabed in Chile’s territorial ocean and inland waters for more than 50 years is considered as such, including evidence that for various reasons is underwater or buried on beaches and shores, the protection of which is the responsibility of the Chilean State. This encompasses sites, structures, artifacts and human remains, along with their archaeological and natural environments, as well as the remains of ships, aircraft, other vehicles or parts thereof and their cargo and contents, along with their archaeological and natural environments. Lastly, in 2017, Chile’s National Monuments Council confirmed the fish weirs located in the national territory as a National Monument protected by Law 17,288, under the category of Archaeological Monument, and extended this status to all fish weirs that are at least 50 years old and/or have been in disuse for at least the same length of time.

Despite this series of regulations, today's global strategies to address the devastation of the oceans and coastal-marine environments are based almost exclusively on the implementation of scientific-technical-administrative policies, underpinned by a common, homogeneous ontology and cosmovision. These policies are reinforced through educational campaigns to generate a standard environmental awareness among civil society and, in parallel, by punitive sanctions for those who violate the norms that seek to protect these ecosystems and the heritage contained therein. But these measures do not manage to be effective [2]. Given that the maritime archaeological heritage is a finite and non-renewable resource, in terms of both its intrinsic (e.g. scientific, historical, spiritual, cultural) and extrinsic (e.g. economic) value (Claesson, 2011 in [25]), for the Chiloé Archipelago of Southern Chile, it is worth asking: What are the attributes of local customs that currently contribute to valuing and protecting the coastal ecosystems of this region? To answer this question, we review the ontological and cosmogonic dimensions of the Williche indigenous communities inhabiting the coasts of the Chiloé Archipelago, whose actions safeguard the coastal spaces that are vital for these populations—the beaches and intertidal zones. It is these dimensions that mediate the behaviour of the Williche inhabitants every time they engage in a practice (e.g. collecting, fishing), thereby limiting the possibility of negative effects on the environment. This approach differs substantially from the actions and impacts of other territorial actors, which are oriented to the exploitation of nature. It also is a way of determining how tangible and intangible heritage produces healthy ecosystems and territoriality.

2. Method

As our intention was to provide a dual perspective in this study, the methodology deployed was based on both classic ethnographic techniques and an autoethnography produced by one of the authors. The ethnographic methodology was based on participant observation implemented intermittently over more than 20 years, as well as ethnographic interviews [48] and reviews of secondary background material (such as theses, scientific publications, and technical reports, among many other references that provide explicit accounts of the islands studied). Ethnographic interviews were conducted with key local agents, residents of several islands of the inland sea, where different ethnopolitical processes are currently taking place. In some territories, for example, local organizations have emerged to defend and safeguard communal and ancestral ways of life, while in others there is a greater presence of industrial actors that are more in tune with the rhythms and requirements of global markets. In the face of this difference, our interviews sharpened the contrasts between territories, as local residents reflected on the role of ancestral knowledge, contemporary narratives, and industrial forms of extraction in the reorganization of local sensibilities about the marine-coastal environment.

The field of study corresponds to the Chiloé inland sea [49], which groups together islands with similar geographic attributes and a common cultural repertoire. As previously mentioned, however, these shared conditions do not necessarily guarantee the exercise of an ancestral cosmovision, and indeed our interest and methodology in this article are focused precisely on inquiring into areas of friction [50] and juxtaposition among these diverse interests. For the second methodological axis, the autoenthnography, we have adopted certain anthropological practices that have challenged the primacy of field ethnography, such as symmetrical anthropology, in which social interactions go beyond the merely human-to-human [51], and Jean Rouch's shared anthropology, in which classical research roles are blurred, facilitating the construction of knowledge from, about, and with local participants [52]. Using participant observation, the authors strove to unveil chains of dependencies among organisms, following Descola (2002:55) who, in reference to Humboldt, spoke of the "(...) intuition that the natural history of humanity was inextricably bound up with the human history of nature” [53]. This work requires the scholar to establish a gaze that transcends the purely human dimension in order to encompass all beings relegated and linked to it; in other words, to explore the relationships among organisms, their role in the world, and the mechanisms through which they weave together both their compatibilities and incompatibilities for their mutual coexistence [53]. Thus, we approached this part of our methodology in dialogue with the multispecies ethnography exercise [54], investigating how ecological niches are co-constituted among organisms that cohabit these islands and exploring the forces of attraction and repulsion that arise among them, primarily through local inhabitants’ interpretations and traditional knowledge. Engaging in this kind of ethnographic work requires sharp observation and the integration of the rational with the sensory, to embody forms of knowledge in concert with nature. This approach sought to understand the relations of familiarity that sustain social collectives [55], practiced primarily in intimate settings, through relationships of care and in the kinships that emerge in everyday life.

In the case of the autoethnography conducted here, it is understood as both a process and a research product [56] that arises from the immersion into and reconnection with the memory of the community itself, positioning the researcher as a relative native [57], navigating the spaces between distance and involvement with the field of study. In this sense, the researcher oscillated between her role as a compiler of memories and her Wapiche zomo (Sic.) (woman of the island) identity, one who experiences her relationship with the sea as one who relates to a neighbour. This meant that, in the same research process she collected information about the beach, the intertidal, and related customs following traditional ethnographic procedures, while also exploring her own kinship relations, affections, and the shared cultural continuity of her island community, adhering to and revitalizing local conversational codes for the transmission of memory. The dialogue with her community and family took place within the framework of trawünes (Sic.), meetings that are conducted as conversations following traditional protocols of respectful speaking and listening and deploy oral arts traditionally called nütram (Sic.), which are relational practices typical of the Mapuche and Williche people. These dialogues involving one of the authors of this article occurred on Caguach Island (42°29'13 "S/73°15'57º) and are highlighted in the text as 'Situated Reflection', meaning that they are contextualized in a community space and in a specific time (in this case the summer of 2024-2025), during collective activities such as shoreline shellfish gathering, potato planting, and in the home. The switch from one speaker to another has a special cosmogonic connotation because it includes a spiritual dimension. On this topic, recalling methodological perspectives from Latin American feminist political ecology [58] and southern ecofeminisms, this autoethnography constitutes a political act and a kind of vindication, insofar as it gives rise to an assemblage that can potentially reconstruct relationships and pluralize the worlds as they are currently experienced. Similarly, the autoethnographic experience encourages walking in step with the community [59] (Sundberg, 2017), reducing the replication of extractivist logic within the research process itself by enhancing dialogical relationships within a dispersed social fabric.

It is therefore not merely a collection of stories and experiences, but the opening up of a field of ‘affectations’ [60], in which knowledge is constructed and linked to a sensitivity, an intimacy, and a type of communication that transcends the oral, premeditated categories. It is a sort of reverse anthropology [61], in which creative acts linked to an integrating morality between communities of humans and non-human entities present in the territory are reconstituted from local perspectives. And this reconstitution does not conclude with the visibilization of concrete practices or activities, but with relationships that are reshaped by resituating them (Tullis, 2019), both at the interpersonal level for the researcher, and at the collective and community level for the subject that emerges [62], that is embodied and performs within this situation.

In this sense, this methodology’s mestizo character shapes an ethical discussion that transcends the purely technical application of ethnographic strategies. The methodology, then, reveals a mutual epistemology [61] among researchers, i.e. a principle of collaboration that is based on redefining the ways that knowledge is produced. This, in effect, incorporates a form of ethnographic writing that does not organize events into a series of causalities. Instead, events are reviewed from the logic of coincidence, in which the co-occurrence of acts allows the emerging relationships to be distinguished.

In terms of product, the writing of results rehearsed a narrative way of thinking through the medium [63], connecting descriptions by an observer from outside the field with those that emerged through autoethnography, whose strength lies in its situated reflexiveness:

"What is the purpose of an autoethnography if not to approach the knowledge that begins in the body to become a description? (...) In Caguach the fire is lit and on it sits an old teapot from grandmother's time. Great-grandmother actually. Silence stimulates contemplation, and through it, images of the past are composed, and, in the absence of precise words, actions appear in the mind, projected from her eyes to be described. It is worth remembering that, as a strategy of adaptation and resistance, acts were transmitted through observation and the names were omitted, as it is the memories that pull the words after them, words that have not been used in the last 50 years" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

This work seeks to update what in the 1980's was called blurred genres [64], in which ethnography relied on narrative resources to overcome the dividing lines between the micro and the macro, the outside and the inside, individuality and collectively, or the local and the global [65]. In the section below, the results of this work are presented with a combined voice, in which the authors are not immersed in a single description, but reinforce the dialogue of contrasts, positioned on parallel planes before a common context.

3. Results

This section addresses aspects that shed light upon the relationship between indigenous cosmovision and ontology and the effects that their manifestations have on the beaches and intertidal, in the form of customs mediated by taboos and other traditional ethical-normative restrictions. The cosmogonic substratum of the Williche people is especially relevant, grouping together creation stories, entities that regulate spaces and non-human entities strongly associated with values and norms. We also wonder: what is the beach, what is the intertidal? For those who inhabit coastal environments, the ontological qualities of these environments are unique to each cultural group and are passed down from generation to generation within their intimate communication networks:

"The bottom of the sea is like a town with streets, each place has a name: where the stones are, is called bajería, where the beach is, is called fango. We know whether we are on the rocks or not, where the sand is and how far the mud extends. When the fisherman asks, “Where did you catch those conger eels?” One says: in the mud of such and such, so many hours from the cove such and such', because all the coves have names, just like the streets of a town. So, the fisherman who knows, goes there. Going to sea in the dark of night, he does whatever he needs to, to get to the place they told him of, that's what you call an artisanal fisherman. We learned it with our fathers, with our uncles and grandparents" (Fuenzalida, 2016: 76).

Here, we are interested in addressing these unique understandings as they are expressed in the indigenous island communities of Chiloé, because the ontological dimension of both beach and intertidal spaces (and what they contain) articulates the indigenous cosmovision with the practical expression of customs. In other words, people interact with each other and with nature according to the elements of their reality, and how these can and should be used. In this case, many elements of the everyday environment have properties that are particular to their world: a rock lying on the beach is not only a stone; it can also be the place where a regulating entity resides, or may even be the entity itself, in the guise of a rock [66,67]. So, the people will behave carefully around it and with it, which is very different from those who only consider it a large pebble on the shore. With this in mind, we reflected on how things that exist in the intertidal and in the sea should be treated, if we are seeking their sustainable future. The tremendous heterogeneity of cultural practices—underpinned by different cosmovisions and the ontological dimensions of the things that make up the world—produces multiple archipelagos with contradictions that jeopardize their ability to continue to support all the territorial actors that inhabit them.

3.1. What Is the Beach, What Is the Intertidal, What Are the Things That Exist There?

The intertidal is situated between the high and low tide marks and is covered and uncovered by the sea on a daily basis, while the beach is the space that extends from the high tide mark upward, and borders other areas of customary use such as forests and fields used for livestock and/or growing, and residential areas. These are the key places where the daily lives and customs of these island peoples unfold. Officially, these spaces are regulated by the National Policy on the Use of the Coastal Zone. This public policy seeks to organize uses and users on a preferential basis, extraction or production being two of the most favoured, allowing certain territorial actors such as maritime concession holders to use restricted areas, and ensuring regulated public access to all of the country's inhabitants. This norm operates under a naturalist cosmovision that separates the terrestrial and the marine in a dichotomy, rendering invisible the continuously interdependent dynamics between the two spaces [68]. In the everyday life of local communities, however, usage regimes are supported by their own normative arrangements that see no firm separation between land and sea, but understand the two places as interdependent. For this reason, Williche communities use the traditional term Lafkenmapu (Lafken: sea, Mapu: land). Whereas the dominant non-indigenous worldview describes the land and sea transition as a 'boundary', the Williche instead understand it as a space in constant transition (made explicit by the tides) that supports uses based on mutual collaboration and equitable access to spaces and species. With this understanding, the sea, as a container of everything, becomes a person:

"The sea is a neighbour, a member of the family. We are neighbours who greet each other every day (...) I have one foot in the water and the other on land. Because we sail the sea, we harvest it, we sow it" (Reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

As previously mentioned, people can understand things that exist in the world very differently [2], and what some may consider simply a thing, others may consider a person [22,69,70,71]. The Williche cosmovision encompasses such ontological possibilities [9,27,28,30], and that affects relationships among people, and between people and nature [9,67,72]. This is especially important with entities that regulate the use of marine-coastal species and spaces: they can produce abundant food if the people comply with the guiding principles of conduct (e.g. taboos), or cause poverty and scarcity if they violate them [27,30]. These entities with this great capacity for agency are called ngenes (Sic.) in the Williche world, and they demarcate the marine-coastal territoriality of these communities:

"My territory (...) is composed mainly of different beings that make up marine life: algae, fish, shellfish, molluscs (...) But it is also composed of the ngen (owners or protective forces) that inhabit these territories" [73] (Arce et al. 2023: 16).

"In the territory we inhabit there is a ngen (protective force) that is very strong (...) one can say that where this ngen is on the coast and in the sea, when the tides are good, there is an abundance of seaweed, it is very abundant, so much so that we cannot manage to take it all" [73](Arce et al. 2023: 18).

But there are also evil entities that are activated and act when taboos are violated, causing the place to degrade through rotting [27]. And these polar opposites are necessary to maintain balance:

"Speaking of the childhoods of my mother and father (...) that was when they learned about the premise of duality as a requirement of balance, where the fertility of the Pincoya (a woman of the sea, half human and half fish) and the overwhelming power of the Cuchivilu (half pig and half fish) are a manifestation of that: abundant food and the contamination of the beach coexist as possibilities, and it is respect, offerings, and keeping alive the rituals that make these energies of the Mapu (land) and the Lafkenmapu (sea) compatible. A symbiosis of energies that exist together between the flooded territory and the dry land. And the same balance enables the existence of many other beings (ngüenes), who have always been invisible but are present in every organism and element, inhabiting boulders, underwater caverns, and fishing weirs" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

These entities have an important capacity for agency in daily life, and in the cosmovision of these communities they are real, expressing themselves in concrete, daily experience as warning or advising people how to act. We define cosmovision as the view or conception of the world that allows us to make sense of reality [2,74], and accounts for the relationships that human beings establish with other things in the world, such as animals, plants, hills, lakes, and spirits, among others [75]. And we understand ontology as "(...) the constitutive units of reality" [76]. Blaser (2009) addresses "(...) those assumptions that various social groups hold about the entities that "really" exist in the world" [11,77], creating "real worlds"; and also, "(...) the presuppositions from which any human group operates in its relationship with the real" [78]. Importantly, these are not mere cultural differences (that we could categorize as folklore, for example), but are actual lived worlds that influence people's decisions and practice [79,80,81,82], including political agency [83] in situations of conflict [11,12]. This is important, because it raises the possibility that there are things with a capacity for agency, entities that influence people’s behaviour and their relationship with nature [29,84]. The sea, for example, becomes a great entity: the sea "(...) is a spirit (...) it has protective beings (...), people, we as people, are part of it (...) and for one to finally achieve a good life, certain conditions must also be met" (Indigenous leader of Llanchid Island, 2nd self-convened meeting. Puerto Aysén, Aysén Region, 2022).

The sea as an entity can unleash its unrest on humans and the environment: "The sea got angry, we say. It got angry because it bloomed, and that is the anger the sea feels (...) when they threw that waste into the sea, the sea got angry" (Longko, a traditional Williche representative of Chiloé, in [22]). This traditional authority was referring to a devastating red tide event (HAB) that occurred after millions of rotting salmon were dumped into the sea off the coast of Chiloé. The consequences of the harmful practices of productive industries and extractive actors have led to ongoing social and environmental conflicts over the past five decades and more [22], degrading the ages-old diversity of the sea:

"People talk about the great scarcity of fish and shellfish. And if the sea is alive... why does it have so few living beings today? Why is an entire coast, so long, not enough to feed its children?" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

The imposition of a dominant ontology and cosmovision that reinforces the current development model has excluded, devalued, and invalidated the entities that are part of the indigenous cosmogonic relational web (which is ecosystemic in these archipelagos, as it forms bonds among multiple species, spaces, and elements of nature) [9]. This problem is not included in the debates and controversies involving other territorial actors, who rely solely to arguments based on techno-scientific variables that ultimately maintain the current model of exploitation they depend on, and which they deem to be the only reality. The difference in understandings of the phenomena experienced by this multiplicity of actors often triggers misunderstandings [80] about the causes of the crisis, and how it can and should be resolved. The problem with misunderstandings is that the parties end up arguing about things that they each view and experience differently without realizing it, whereas in a disagreement [85], the different sides agree on what the thing being argued about is, but not how it can and should be resolved.

We consider that the misunderstandings that occur in relation to the beach and intertidal of these islands are evidence of significant ontological and cosmogonic differences, where each disputing actor is experiencing a different reality that is not visible to the others. This often occurs when multiple users overlap in the same place and time—for example, when each summer the islanders meet each other to collect seaweed in accordance with their customs and cosmovision (including regulatory entities), and at the same time fishermen organized into fishing fleets engage in intense commercial fishing. The ensuing conflict emerges because each party does not comprehend the others’ arguments, which increases tension and may even escalate to physical violence and threats. Each considers their own arguments to be fair and sensible, since they are based on true facts: For the former, over extracting seaweed is not only unfair (since fishermen have better equipment and their actions threaten local inhabitants’ livelihoods), but will lead to devastating consequences by violating the taboos that regulate the use of the beach and intertidal. Meanwhile, the latter consider the beaches and intertidal to be freely accessible (endorsed by State regulations), with no local community entitled to limit their extractive activities, especially when there are natural resources available. This brings us to the next question, which deals with how these spaces -and what they contain- can and should be treated in a scenario where more than one reality is operating simultaneously.

3.2. How Can and Should These Spaces Be Used?

The normative ethical substratum that underlies the customary way of life in this island territory is embedded with reminiscences of the Williche island communities’ traumatic encounters with European settlers when they first arrived and began to settle in the area, and the accommodations the former were forced to make:

"The second pot began to boil. The steam, with its humidity, dissolved temporal distances and brought to the present the persecution, forced displacements, abandonment, and confusion when the first missionaries arrived. Are these ontological differences the result of the denial of ancestral knowledge, which told us that everything is tied to our knowledge about our surroundings? Knowledge of clouds and wind was punished as witchcraft. Knowing the tides, knowing the many things related to that spirituality began to be frowned upon (...) Then, those who came from far away, when trying to change the belief in many spirits, many ngnes... into belief in a single higher being, that was the change, that was the loss. And we began to get sick and, spiritually, to forget ourselves. A silence entered, where is the knowledge to enter into communication with them?" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

On the island of Nayahué (42°43'52 "S/73°03'48 "W), in Chaitén Municipality, an elderly couple warned that róbalo (rock cod, Eleginops maclovinus) cannot be fished during mating season because it infringes upon their intimacy as a couple, and that belief is shared by local families, who change their fishing habits and productive activities during that time [9]. This approach is radically opposed to the perception and relationships that operate among artisanal fishermen organized into large fishing fleets, who catch fish as resources to be exploited, without disregard biocultural calendars in favour of State-imposed closed seasons, and even work against each other: "(...) when two or three chalupas (fishermen) fish together, sometimes they catch almost nothing because they start chasing each other and running each other off, as they say, so the other boat is never left in peace to fish" [86]. The effects of this practice are devastating to the coastal ecosystems on which traditional communities depend: "There is nowhere to draw resources from anymore. There are none left near the island or far from the island. There are no minimum-sized fish left" (islander from Chaullín Island, Quellón Municipality. Semi-structured interview, 2023). In this way, everyday coastal spaces become not only unsustainable for practicing a customary way of life but also activate conflicts among neighbours that are based on competitiveness—a dynamic that the local island model avoids through locally regulated relational procedures. This social problem, which manifests itself on the beach, the intertidal, and even in subtidal and open waters, has prompted these island communities to search deep within the memories of still-living elders for mechanisms that would allow them to avoid these frictions, especially because if they do not prevent them, the result will be a future of uninhabitable islands:

"During a minga [work party] to dig potatoes, we neighbours talked about the experiences that the old ones had left us. Although the stories differed, they all pointed to the same goal of preserving life and vitality in the intertidal. To ensure this, the journey to the beach or out to sea also involved upholding certain spiritual safeguards. Some neighbours used to say that to go down to the shellfish bed, you should go on an empty stomach so that the Pincoya would be kind enough to give you food. Others said that problems and grudges should be left on dry land, so you visited the intertidal in the best pañihue (spiritual state) possible: you have to go down there serenely and without quarrelling, or else the sea will withhold her gifts from you. Similarly, for some it was important to make an offering to the ngen that inhabits the shallows, since when looking for food, they had to give thanks for catching the Pincoyita's children. They recalled that these offerings always had to take duality into account, which meant that all offerings had to be double: if murke (toasted flour) (Sic.) was brought, so should chicha or muday (beverages made from fermented grains and/or fruit)" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

The most common taboos in

Williche culture are not to compete for shared resources (such as beaches, seaweed, fish, and shellfish), not to fight with your neighbours on the beach, not to hoard, and especially, not to be selfish. Also, you must not extract 'seeds' (young and juvenile molluscs), extract from 'seed beds' (breeding grounds), or take more than you need. Another objectionable conduct is to use artifacts that destroy the substrate and shellfish beds (for this reason, for example, the people prefer to use

paldes, small hand shovels that allow them to gather shellfish more gently,

Figure 6).

"Taboos, or rather, our ethics on the beach, are the result of a long process of observation (...) that gives us certainty. We know that some birds or animals are omens that foretell good works or misfortunes to come. That when the tiuques (Milvago chimango) gather and call outside the house—quiiiiiiiiiiu, quiu, quiu, quiu—it means that the catch will pile up. We also see that in people, whose good or bad spirits, or pañihue (Sic.), play a role in accomplishing day to day work. We recognize a very low tide, or pilkán (Sic.), by the seagulls’ cries, or a rise in the high tide mark, which is also closely related to the full moon and new moon lunar phases" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

Transgressing these guiding principles leads to direct or indirect sanction by the regulatory entities. Punishment is meted out indirectly when regulating entities such as the Pincoya move fish, algae and shellfish away from the beach where a taboo was violated; other entities of a more destructive nature, such as the cuchivilu, cause the place to deteriorate, destroying everything [28,38], with the environment only restored once the relationships among the people have become right again, following the principles of good conduct [9,30]. A more direct form of punishment is when the entities present themselves to the offender: "(...) the mermaid came up into the boat because it had collected large quantities of shellfish and pelillo fish on each tide" [87]. In this case, the traumatic experience changes the offenders’ behaviour after the fact and serves to collectively reinforce their cosmovision. But these precautions do not completely cleanse the place or the people:

“The ancients remember holding a series of rogativa ceremonies next to the fish weirs to scare away evil spirits that could be locked inside. With branches of chaumán (Sic.) (Raukaua laetevirens), the weir owner would recite the incantation, Pininarro, pancacarro, ah Fiura! repeatedly to scare the evil being away. One neighbour recalled a ceremony to attract fish, where a man of good pañihue (Sic.) had to enter the territory of the Trauko (the guardian ngen of the forests) to look for branches of chaumán to pass through the nets and canvas. Once the man returned, he was enchaucao (sic.) (that is, contaminated by the essence of the Trauko), so he had to purify his spirit by jumping over a bonfire of marros (Sic.) (small pieces of driftwood). Nets and canvases were also hung over the fire so that the chaumán smoke would purify them and bring abundance. The enchaucao was whipped with chaumán branches while jumping over the fire, while those present recited, “Pininarro, pancacarro, ah Fiura!” (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

The people of these islands conduct numerous coastal rituals, including the

nguillatunes and marine

rogativas (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) such as

treputos [38], which shed light on the ethical-normative principles that govern the lives of

Williche community members.

It is on the beaches and in the intertidal where these traditions still influence people's behaviour, especially during conflicts that occur around seaweed extraction among islanders adhering to customary law. But something very different happens when there is conflict between traditional families and members of artisanal fishing fleets sailing from urban ports. These fleets exploit the beach and the intertidal under the logic of free access, transforming both spaces into a scene of friction and misunderstanding viz a viz local inhabitant. They do not even reach disagreement (as a stage prior to agreement), because for that to happen they would have to at least agree on what things are being disputed, and how they could and should be used. This type of socio-environmental conflict, with its attendant ontological entailments [29], has become increasingly common due to the international demand for marine resources such as seaweed and shellfish, triggering continuous extractive frenzies (called 'fevers’ locally) with high socio-environmental costs.

In the latter case, it is important to distinguish socio-environmental conflicts from ontological socio-environmental conflicts: the former should be understood as disputes over the unequal distribution of natural resources [44], including their alteration, in a geometry of unequal power (Massey, 2005) that may threaten human rights. But a different thing occurs when the parties have different ontological understandings of the cause of the conflict, without being aware of it [12,90]. Unfortunately, these types of conflict have become chronic, and neither the State nor the conflicting parties themselves have been able to resolve them, because for this to happen each actor would have to be able to perceive the ontological and cosmogonic differences that drive their opponent’s position. There also must be an openness to different ontological and cosmogonic norms [9]. In our view, the mediating role of the State is essential in this case, but its ontological/cosmogonic underpinnings are the same as those driving the artisanal fishing fleets, and so it remains incapable of perceiving the local communities’ view of their world and the elements that inhabit it. This potential mediator therefore usually lands on the side of the artisanal fishing fleets, perpetuating the conflicts between the parties and the overexploitation of nature (including the beaches and the intertidal) [9].

3.3. How Ontological and Cosmogonic Differences with Other Territorial Actors Demarcate Distinct Beaches and Intertidal Areas?

i) Why have we been run off, pushed out of the sea, out of our waters, our islands? Will the ngen remain on the islands that are becoming depopulated today, will there be more room for them? (…)” (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025). These questions, raised in Caguach Island, define issues that prevail across the archipelago: (i) National public policies have granted privileges to uses and users oriented to marine extraction, which has sidelined traditional actors engaging in customary uses (the communities that rely upon the islands’ customary way of life); (ii) This has fostered the depopulation of the islands, with residents migrating steadily to cities on the mainland or to larger islands that are more connected to the rest of the region, both for salaried work and for better access to basic services such as health and education, among many other reasons. It is mostly elderly inhabitants who remain on the islands to maintain traditional relations with their environment, including involving regulatory entities in their decision making and in practical expressions of their customs. When these generations finally pass on, the islands’ ontological and cosmogonic substratum will probably also pass away, since those who migrate and are educated away are subject to the intense forces of global homogenization, with its attendant appropriation of the dominant cosmovision and ontology, and the forgetting and/or reinterpretation and/or discrediting of those of the past; iii) This means that the beaches, intertidal, and waters (as well as the forests, grasslands, and wetlands) will also be depopulated of their regulating entities. This will necessarily change the coastal landscapes, as the absence of these entities will have major impacts on marine-coastal ecosystem relations.

The current socioecological scenario in the Chiloé Archipelago is very concerning [91,92], suffering from the imposition of a development model based exclusively on the extraction of marine-coastal natural resources well beyond the capacity of those ecosystems, which will not be able to continue supplying the markets and territorial actors that are driving this ‘perfect storm’ [17]. In response, local Williche indigenous communities have implemented a political-territorial strategy that seeks to protect marine-coastal spaces from this extractive frenzy through ECMPO requests, but they have been severely challenged not only by extractive industries and actors, but also by the Chilean State itself [93]. In this scenario, the indigenous cosmogonic and ontological substratum becomes subordinated to the dominant cosmovision and ontology [9,30]. A variety of alternatives are being proposed to overcome this impasse, from readjustments of public policy to proposals for new forms of governance that recognize local cultural traditions [94,95]. In general, however, spiritual considerations have been relegated to the background, or even ignored entirely. Many communities themselves recur to the former to avoid exposing their entities to a society that has little or no tolerance of them, or that will a turn them into folklore and distort their meaning. As such, their ethno-political proposals generally emphasize productive aspects, as this is a consideration more comprehensible to non-indigenous society:

"(...) what will happen to our spirituality if those who know it are already leaving. Their souls are moving with the tide, and perhaps the knowledge has not been conveyed sufficiently for them to understand why our sea must be defended. Everything is related, because you cannot take care of or protect what you do not know. Those fishermen who compete today and who forgot their roots... who failed to give them the knowledge? Isn't there a voice inside them telling them to get it right? Today, what will it take to activate a spirituality that is perhaps hidden within them? What would be our role in this, what would be the role of the State in this?" (Situated reflection, Daniela Leviñanco, pers. comm. Summer 2024-2025).

4. Discussion

The relationship between ontology, cosmovision, and practice (or doing) proves that there is a substantial link that is territorially expressed in healthy coasts or unhealthy ones. In other words, the inhabited environment is the result of 'what things are' for its inhabitants, and what 'can and should be done with them'. In preparing this manuscript, we noted that a rock in the intertidal can be just that—a rock...but it can also be the spatial landmark where a regulating entity rests and watches over, or may even be the regulating entity itself, even if does have the appearance of stone. It can also be that the rock has no explicit presence, even within the web of local relations, and yet it maintains its presence through collective behaviours that are governed by coastal taboos. If these taboos are upheld, the people expect that the beach, the intertidal, and the sea (whether its waters or its bed) will provide abundant food, and that the species that live there will share in the well-being experienced by local families. But if they are violated, the opposite will occur. Even if the entities are not called by name, they are the ones that produce this concrete effect on the environment, concrete because everyone—human and non-human—will experience it.

For these families, the increasingly common degraded coastal landscapes are the result of the abandonment of this way of conceiving the world and acting in it: they reveal the absence of regulating entities. In our view, it is important to take this reflection seriously in order to understand the devastating effects of the detachment and lack of empathy shown by the actions of urban fishing fleets, aquaculture industries, and many other individuals who live in and/or use this archipelago, from which they seem to have disconnected. They are here, but they are no longer aware that they are part of a web of vital interdependent relationships; they do not perceive that their actions cause damage to the hundreds of species and people that disappear from here, and when they finally learn about it, they find reasons to place the blame on everyone but themselves. This problem of ontological and cosmogonic relational detachment cannot be solved solely with educational content in national training programs, because these tend to impose the same view of nature that drives the current model, one based on the exploitation of nature (naturalistic ontology). Nor is the solution simply to bring sanctions against those who cause environmental damage, because on balance, considering how weak environmental legislation and enforcement are, it is more profitable to keep violating them. It is our position that this precarious situation can only be rectified by returning those who use and inhabit these coasts to a shared understanding of what the things that exist there are, and what can and should be done with them.

If clam beds are merely exploitable clam beds, people will not feel uncomfortable extracting everything they can to sell. For those who think of the world this way, they feel compelled to act this way despite the possible penalties, as there will always be another vessel in line willing to do so. Nor will they be concerned about what will happen to the seabed when all the clams have disappeared, because for those who act this way, their vision of nature is one of inexhaustible supply: there will always be clams, even if the number of commercial vessels increases exponentially. When the overexploited environment shows them that this belief cannot be true, instead of questioning their worldview, they usually demand that the State provide more shellfish by increasing quotas and opening new zones and territories for extraction. This problem, which is absurd to begin with, has become chronic, thanks to the way we humans who inhabit these islands treat nature. Only an abstract, externalized form of nature can possess the inexhaustible capacity to produce and to recover from the harmful effects of our harmful way of life.

Indeed, many conservation and regulatory initiatives implemented by the State, non-governmental organizations, and civil society, resort to the same ontological and cosmogonic rationales that, paradoxically, destroy the very marine-coastal environments they purport to protect. Clams on a sandbar are just that, clams, and instead of being extracted uncontrollably they should be used only under coherent management plans...or removed beyond the reach of human action within protection and/or control areas. But they will hardly be conceived of as part of a web of broader ecosystemic relationships, in which their presence in a place is the result of other lives that may be near or far away, and in which their presence is vital to enabling other lives, near and far, to exist. Neither will they be seen as the internally heterogeneous populations they are, with infants, youth, and adults; nor that their well-being can be maintained without preventing their customary use, which includes care regulated and/or mediated by taboos and ethical-normative considerations. These clams, ultimately, are part of worlds inhabited by entities that seek to ensure the well-being of all, far beyond the mere satisfaction of human needs.

5. Conclusions

Evidence shows that indigenous peoples can strengthen marine-coastal ecosystem functions by actively practicing their customs, yet this notion has not been widely embraced by nations. As a result, these peoples continue to be pushed aside physically (separated from the natural spaces they live in, and/or prevented from practicing their customs, including those involving the use of natural resources) and symbolically (as their ontologies and cosmovisions are devalued as folklore, among many other problems).

This article examines the ontology and cosmovision of the Chiloé Archipelago’s Williche people, whose customs provide safeguards and ecosystemic care through the existence of entities that regulate the relationships among humans, the environment, and other species. It was developed through the interplay of a traditional ethnography based on primary and secondary data collection and analysis, and the situated reflections of one of the authors, a Williche community member, who organized traditional conversations (called trawün) on her home island of Caguach.

The problems identified in the standard surveys and systematized background information were in fact confirmed by the first-hand observations from the heart of the archipelago and are as follows: (i) the spaces where these communities live their lives, such as the beach and the intertidal, are affected by overfishing and pollution caused by territorial actors (especially artisanal fishing fleets and the aquaculture industry) whose ontologies and cosmovisions differ profoundly from their own; (ii) these communities continue to practice a customary way of life that manages to slow the pace of degradation of their living environments; iii) the customs that allow this positive effect on the environment have practical and visible expressions (i.e. shellfish and seaweed gathering, fishing, and celebrating in traditional ways), but their most important aspect is invisible, rooted in collective ethical-normative considerations that are based on ontological (what are the things that exist in the world) and cosmogonic (how can and should they be used) dimensions mobilized through regulatory entities.

Based on this understanding, the authors recommend taking these customs and their underlying ontological-cosmogonic belief systems into account as legitimate ways of inhabiting these archipelagos, allowing them to be practiced as one of the legal uses established under national legislation. Failing to do so, and instead keeping them constrained, and preventing their expression in favour of other uses and users that are focused exclusively on the exploitation of nature, will lead to increasing levels of environmental degradation and social precariousness in the zone. We believe that in the former scenario, the manifestation of this indigenous cosmovision has produced and will produce life-giving islands with ecologically healthy intertidal and subaquatic environments and healthy social relations, and where there is the possibility of restoring areas previously damaged. If, however, this island-based culture is further prevented from manifesting itself freely or disappears entirely, this will intensify the emergence of an archipelago of degraded islands with pillaged and polluted intertidal and underwater environments, and social relations characterized by chronic socio-environmental conflicts. It is on this basis that we insist on the need to move away from the mere ethnological description of customs, whether indigenous or traditional, and move towards valuing the weight these customs have in sustaining the natural world we all inhabit.

Author Contributions

Ricardo Álvarez and Isabel Yáñez: conceptualisation, bibliography survey, investigation, methodology, interpretation of qualitative data, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Daniela Leviñaco: methodology, key informant, data gathering, conceptualisation and interpretation. Isabel Cartajena: project leader, funding acquisition, investigation, interpretation of archaeological data and underwater cultural heritage. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Agency of Research and Development (ANID)—Millennium Science Initiative Program (NCS2021_040).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the families of Caguach Island for their willingness to participate in conversations initiated by one of the authors, who is a member of the island community. These conversations helped establish parallels with the standard survey and analysis developed by the other authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

Indigenous Law (1993):

LEY INDÍGENA Nº 19.253

ECMPO: Espacios Costeros Marinos Pueblos Originarios (Indigenous Peoples' Marine Coastal Spaces)

MINEDUC: Ministerio de Educación (Ministry of Education)

References

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Dessane, E.B.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicot, B. Cosmovisiones de la tierra. 2017, Ed. Universidad de Magallanes, Chile.

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; D, G.-C.N.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Cuerrier, A.; Joseph, L. Well grounded: Indigenous Peoples' knowledge, ethnobiology and sustainability. People Nat. 2022, 4, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi Targets. 2011, Canadá.

- IUCN. The state of indigenous Peoples' and local Communities' lands and territories: A technical review of the state of indigenous Peoples' and local Communities' lands, their contributions to global biodiversity Conservation and ecosystem services, the pressures they face, and recommendations for actions. World Conservation Congress 2021.

- Scheidel, A.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Bara, A.H.; Del Bene, D.; David-Chavez, D.M.; Fanari, E.; Garba, I.; Hanaček, K.; Liu, J.; Martínez-Alier, J.; et al. Global impacts of extractive and industrial development projects on Indigenous Peoples’ lifeways, lands, and rights. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, R.; Caniullán, D.; Catín, J.; Cheuquenao, P.; Coñuecar, Y.; Diestre, F.; Jara, P.; Millatureo, N.; Vargas, D.; Ojeda, J. Reciprocal contributions: Indigenous perspectives and voices on marine-coastal experiences in the channels of northern Patagonia, Chile. People Nat. 2025, 7, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lvarez, R. Conflictos ontológicos en los archipiélagos septentrionales de la Patagonia insular, Chile. Manuscrito de Tesis de Doctorado de Ciencias Sociales en Estudios Territoriales. 2025, Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, J.; Salomon, A.K.; Rowe, J.K.; Ban, N.C. Reciprocal Contributions between People and Nature: A Conceptual Intervention. BioScience 2022, 72, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Sentipensar con la tierra. Nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia. 2014, Ed. Unaula, Colombia.

- Blaser, M. Notes towards a Political Ontology of ‘Environmental’ Conflicts. In: Green, L. (Ed.) Contested Ecologies: Dialogues in the South on Nature and Knowledge. 2013, HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Lien, M. & Pálsson, G. Ethnography beyond the human: the ‘other-than-human’in ethnographic work. Ethnos, 2021, 86(1), 1-20.

- Diestre, F. , Araos, F. La recuperación de los comunes en el sur-austral: construcción institucional de Espacios Costeros Marinos de Pueblos Originarios. Polis, 2020, 19(57), 19-50.

- Delgado, L.E.; Sandoval, C.; Quintanilla, P.; Quiñones-Guerrero, D.; Marín, I.A.; Marín, V.H. Including traditional knowledge in coastal policymaking: Yaldad bay (Chiloé, southern Chile) as a case study. Mar. Policy 2022, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skewes, J.C. , Alvarez, R. y Navarro, M. Usos consuetudinarios, conflictos actuales y posibilidades de conservación en el borde costero de Chiloé insular. Revista Magallania, 2012, 40(1):107-123.

- Castilla, J. C. , Armesto, J. J., y Martínez-Harms, M. J. (Eds.). Conservación en la Patagonia chilena: evaluación del conocimiento, oportunidades y desafíos. 2021, Ediciones Universidad Católica, 600 pp.

- Carrasco-Bahamonde, D. Desarrollo acuícola y territorialidades en disputa en el Archipiélago de Chiloé (Chile). En Territórios, re-existências e afetos, NUREG-Núcleo de Estudos Território e Resistência na Globalização-30 anos, 2024, 121-146.

- Berkes, F. Sacred ecology, 2008. New York: Routledge.

- Poh Poh, W. , Marone, E., Lana, P. y Fortes, M. Island Systems. In: Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends, Hassan, R., Scholes, R., Ash, N. Eds., 2005. Island Press.

- Baldacchino, G. Studying islands: on whose terms?: Some epistemological and methodological challenges to the pursuit of island studies. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, B. Development betrayed: The end of progress and a co-evolutionary revisioning of the future, 2006.

- Coq-Huelva, D.; Ther-Rios, F.; Bugueño, Z. Scalar Politics and the Co-Evolution of Social and Ecological Systems in Coastal Southern Chile. Tijdschr. voor Econ. en Soc. Geogr. 2017, 109, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mançano, B. Sobre la tipología de los territorios. Acción Tierra, 2008, 1-20.

- Ward, I.; Smyth, D.; Veth, P.; McDonald, J.; McNeair, S. Recognition and value of submerged prehistoric landscape resources in Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 160, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, I.; Elliott, M.; Guilfoyle, D. ‘Out of sight, out of mind’ - towards a greater acknowledgment of submerged prehistoric resources in Australian science-policy as part of a common heritage. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, D. El sustrato indígena de los seres mitológicos de Chiloé. Proyecto Bajo la Lupa, 2022. Subdirección de Investigación, Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, Chile.

- lvarez, R. El alma de los Peces. In: La pesca en Chile. Miradas entrecruzadas, Álvarez, R., S. Rebolledo, D. Quiroz y J. Torres Eds. 2022, Santiago: Ediciones de la Subdirección de Investigación del Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, 77-102.

- lvarez, R. , Araos, F., Núñez, D., Skewes, J., Rozzi, R., Riquelme, W. Otros-que-humanos tensiones ontológicas en la implementación de la ley Lafkenche. CUHSO, 2023, 33(1), 160-184.

- Fundación Superación Pobreza (FSP). Usos consuetudinarios reflexiones desde el mar interior de la región de Los Lagos. 2024, Estudio regional.

- Farías, A. , Gelvez, X., Tecklin, D. Análisis de la Cobertura Marina de las Áreas Silvestres Protegidas en Patagonia Chilena. 2020, Documento Técnico, Programa Austral Patagonia, Universidad Austral de Chile, 26 pp.