1. Introduction

Breastfeeding offers numerous advantages for both mothers and their infants [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, this experience can sometimes be challenging, as many mothers report feelings of fatigue and inadequate rest. The Empowering Mothers Improving Breastfeeding (EMIB) project is a collaborative study between University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam (UMC) and Yonsei University, Korea. EMIB aims to evaluate how breastfeeding practices affect mothers' physical and mental health. One of the aims of this study is to determine how breastfeeding practices affect mothers' sleep. Although some studies have shown that breastfeeding practices in any form do not affect mothers' sleep duration or sleep quality [

4,

5], others have shown that breastfeeding increases the number of times mothers wake up during the night [

6,

7].

In Vietnam, polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for assessing sleep quality. However, it is expensive, difficult to implement in the community, and only applicable to small sample sizes in controlled environments [

8]. Therefore, the EMIB project used two sets of tools at the same time, the Fitbit Charge 6 wearable device and a structured questionnaire, to record sleep data under natural living conditions.

No specific studies have evaluated the Fitbit Charge 6 wearable device in specific populations, such as postpartum women. In other words, results from healthy subjects may not necessarily apply to other specific populations. Choosing the right data collection instrument is crucial in community health evaluation. This choice not only guarantees the accuracy of the research findings but also conserves resources, including time and finances.

This research is affiliated with the EMIB project. The goal of this study was to evaluate the degree of alignment between two assessment tools (Fitbit Charge 6 and a structured interview questionnaire) in measuring sleep quality. The findings will assist researchers in selecting the most suitable tool for evaluating sleep in particular demographics.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional study design was employed. The study utilized a convenient random sampling method. The inclusion criteria comprised mothers aged 18 and above who visited the University Medical Center's Healthy Child Clinic for a follow-up appointment, practiced breastfeeding within one month postpartum, and consented to participate in the research. The exclusion criteria consisted of mothers whose children had chronic illnesses, those using sleep aids, and mothers with breastfeeding contraindications, such as heart failure, severe pulmonary tuberculosis, advanced liver disease, treatment with antiepileptic or psychiatric medications, a breast cancer diagnosis, or drug addiction.

A pilot study was carried out involving the first four mothers to assess the correlation between sleep duration and nap length, as measured with the Fitbit device and through direct interviews. The determined correlation coefficient r ranged from 0.2 to 0.3. The data obtained from these initial four mothers were incorporated into the study.

2.2. Study Procedures

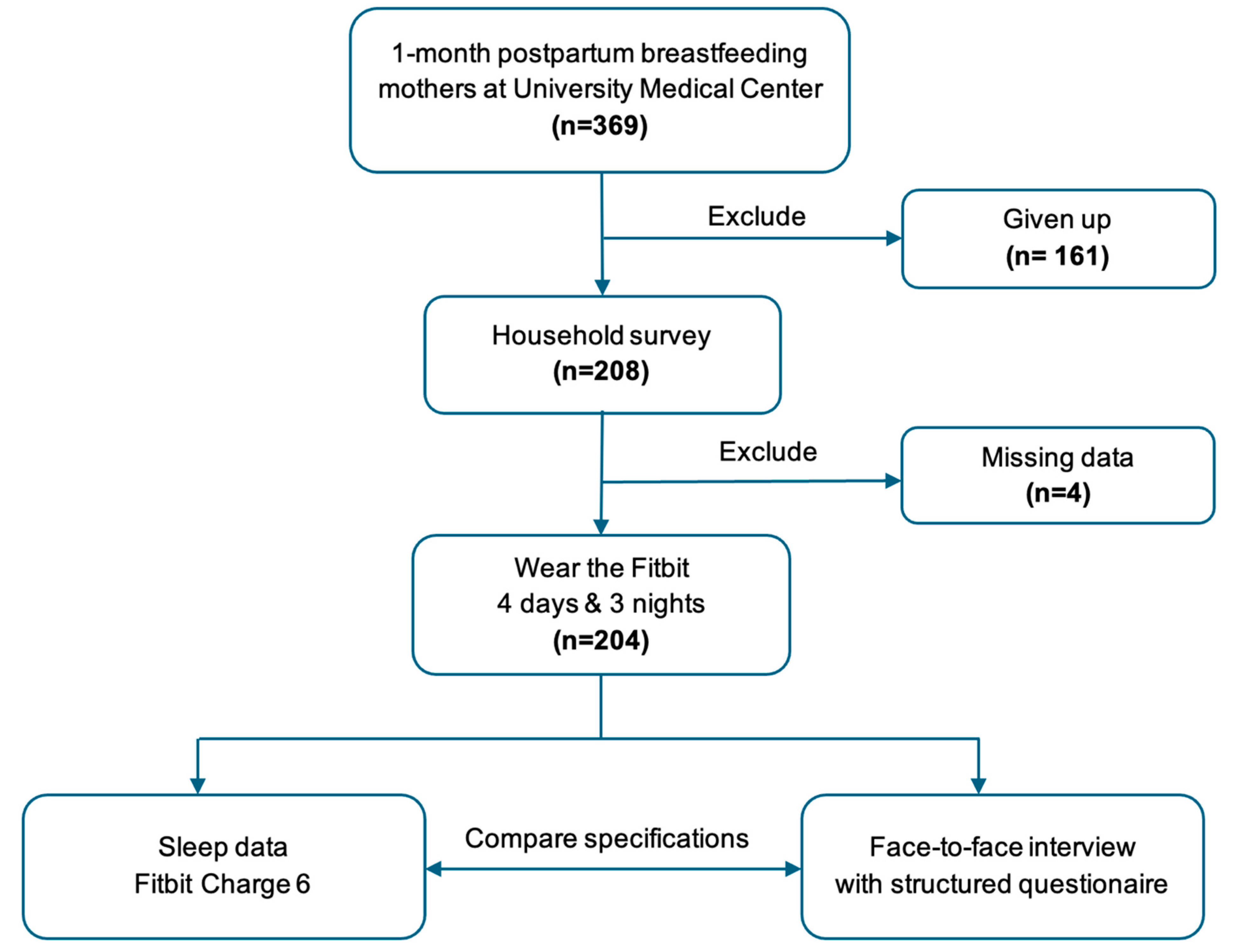

The study was described to all mothers who came for a 1-month postpartum check-up at UMC. If they agreed to participate, they would sign a consent form (n=369). A researcher would then schedule an appointment to visit the mothers' homes. At this appointment, a Fitbit device would be synchronized with a smartphone through a system-encrypted Google account. We also instructed the mothers on how to wear the device continuously for 4 days and 3 nights and advised them on how to ensure continuous data recording. However, during this period, 161 subjects refused to continue for various reasons: because they found it annoying, did not want to wear the device for fear of affecting the baby, or were allergic to the strap. On the 5th day, the researcher returned to the mothers' home to collect the device and interviewed them directly using a structured questionnaire integrated into the KoboToolbox software, including 136 questions, 10 questions of which were about sleep. The interview duration was 40 minutes. At this stage, only 208 cases remained for further study, 4 cases of which had incomplete data. Finally, 204 mothers had sufficient data for analysis, during the period from 07/2024 to 04/2025 (

Figure 3).

2.3. Sample Size

Sample size was estimated using the correlation coefficient estimation formula:

With σ = 0.05 and β = 0.2, the estimated correlation coefficient between Fitbit-recorded sleep time and direct survey questions across the pilot studies ranged from 0.2 to 0.3; we chose r = 0.2 to determine the largest minimum sample size. The minimum sample size was calculated to be 194 1-month postpartum breastfeeding mothers.

2.4. Variables and Measurements

Regarding the structured questionnaire, sleep quality is based on the Oxford Sleep Survey and CDC Sleep Quality Module (BRFSS) [

9]. It consists of 10 questions focusing on total sleep time (TST) including sleep latency, frequent nighttime awakenings, daytime short nap habits, sleep disorder symptoms, and body sensation after waking up.

The Fitbit Charge 6 tool, from Fitbit Inc., a technology company officially acquired by Google in 2021, helps expand the integration between health monitoring hardware and the Google Health data platform [

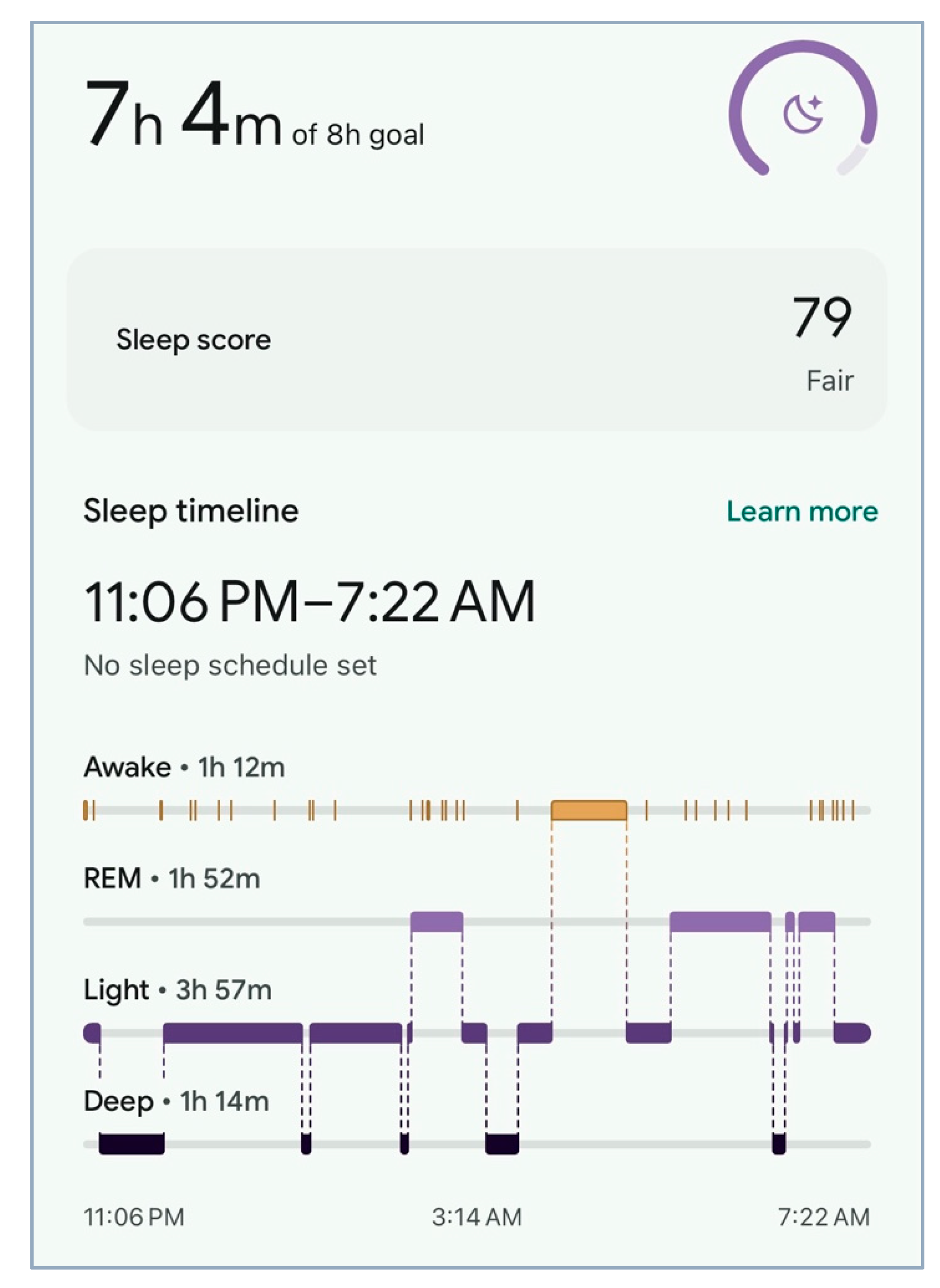

10]. Fitbit Charge 6 is the latest version of the Charge wristband device line, with advantages in sleep monitoring (

Figure 1). It operates on the principle of integrating physiological indicators such as heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), etc., and motion sensors to produce specific parameters in each sleep stage [

11,

12].

Parameters extracted from the device include the total sleep time, time awake during sleep cycle, light sleep time, deep sleep time, REM sleep time, time of short naps during the day, and sleep quality score (

Figure 2). Some studies show that Fitbit has reliable results and can replace polysomnography (PSG) when monitoring the health of subjects in the field [

13,

14,

15]. According to a comparative study with PSG, the Fitbit Charge 3 series on student subjects has high sensitivity in detecting sleep (0.95), superior specificity in detecting wakefulness (0.69 compared to 0.33 and 0.29 in actigraphy algorithms), and a very high positive predictive value (0.99) [

14].

We focused on analyzing 9 groups of variables related to sleep characteristics, including total sleep time (TST), short nap time, sleep latency, sleep satisfaction after waking up, sleep stages, sleep disorder symptoms, co-sleeping habits with infants, number of roommates, and causes of insomnia (

Table 1).

Of these, four variables (collected simultaneously via the Fitbit device and structured questionnaire) were selected for direct comparison: TST, short nap duration, sleep satisfaction, and Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO). In particular, the sleep satisfaction variable from the questionnaire reflecting the subjective perception of rest and recovery after sleep was compared with the Fitbit Sleep Score, a composite measure calculated by Fitbit's internal machine learning algorithm based on components such as sleep duration, deep/REM sleep ratio, and restoration index [

16]. For WASO, we compared objective data recorded with the wearable device with the mothers' subjective perception of how often they woke up during the night. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), healthy adults have a total wake time of only 20 - 40 minutes in the sleep cycle; exceeding this threshold is a warning sign of significant sleep fragmentation [

17].

Other clinical data collected included the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants: age, religion, education level, pre-pregnancy BMI, exclusive breastfeeding, and number of roommates. These variables were used to help interpret the results and further discuss factors affecting sleep in postpartum women with breastfeeding practices.

2.5. Data Analysis

The Fitbit device would be synchronized with a smartphone through a system-encrypted Google account. The structured questionnaire integrated into the KoboToolbox software. All data from the two sources above will be entered, cleaned, and analyzed using Stata 17.0 software (Stata Corp LLC, Lakeway Drive, College Station, April 2021-TX, USA).

We used frequencies and percentages to describe qualitative variables and means and standard deviations to describe quantitative variables. The correlation between sleep duration and nap duration recorded with the Fitbit and direct survey questionnaire was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, classified as strong (> 0.5), moderate (0.50 - 0.30), and correlation (< 0.30) [

18]. Agreement between the Fitbit Sleep Score and sleep satisfaction from the direct interview was assessed with the Kappa index, classified as very good (1.00 - 0.81), good (0.80 - 0.61), fair (0.60 - 0.41), poor (0.40 - 0.20), and very poor (< 0.20) [

19].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the HCMC University of Medicine and Pharmacy Ethics Council on Bio-Medical Research via Decision No. 619/UMP-BOARD, issued on May 2, 2024. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Data was kept anonymous and confidential during all stages of the study. Mothers with a sleep disorder that seriously affected quality of life were referred to a specialist for appropriate management.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Research Subjects

The subjects of our study were all mothers who breastfed their babies about 1 month after giving birth. The average age of the mothers in the study was 30.3 ± 3.9 years, with the majority being between 25 and 35 years old (83.3%). Most of the mothers did not follow any religion (92.7%), had a college or university degree or higher (90.7%), and had a maternal BMI at the time of the survey according to Asian standards from 18.5 to 22.9 (49.5%) with a high rate of overweight (45.6%) (

Table 2).

3.2. Assessment Using Fitbit Device

Table 3 shows the assessment results of sleep characteristics using Fitbit watches. The average sleep time of the study subjects was 5.5 ± 1.4 (hours), of which the majority had a sleep time of less than 6 hours (60.3%). The majority awoke during the sleep cycle (99.0%), with 54.0% of total awakenings lasting more than 40 minutes and took naps during the day (71.6%). Sleep Score was classified according to the device manufacturer's instructions (good: ≥ 80 points; poor: < 80 points), and the majority of study subjects had poor Sleep Scores (95.6%).

3.3. Assessment Using Direct Interview

Table 4 shows the assessment results obtained via direct interview with the study participants. The average sleep time of the study participants was 4.6 ± 1.0 (hours), and some participants slept less than 6 hours (83.8%). Most of them woke up during the sleep cycle (90.7%), took short naps during the day (92.2%), and were not satisfied with their sleep (82.4%).

3.4. Conformity Between the Two Recording Toolkits: Fitbit vs. Face-to-Face Interview Panel

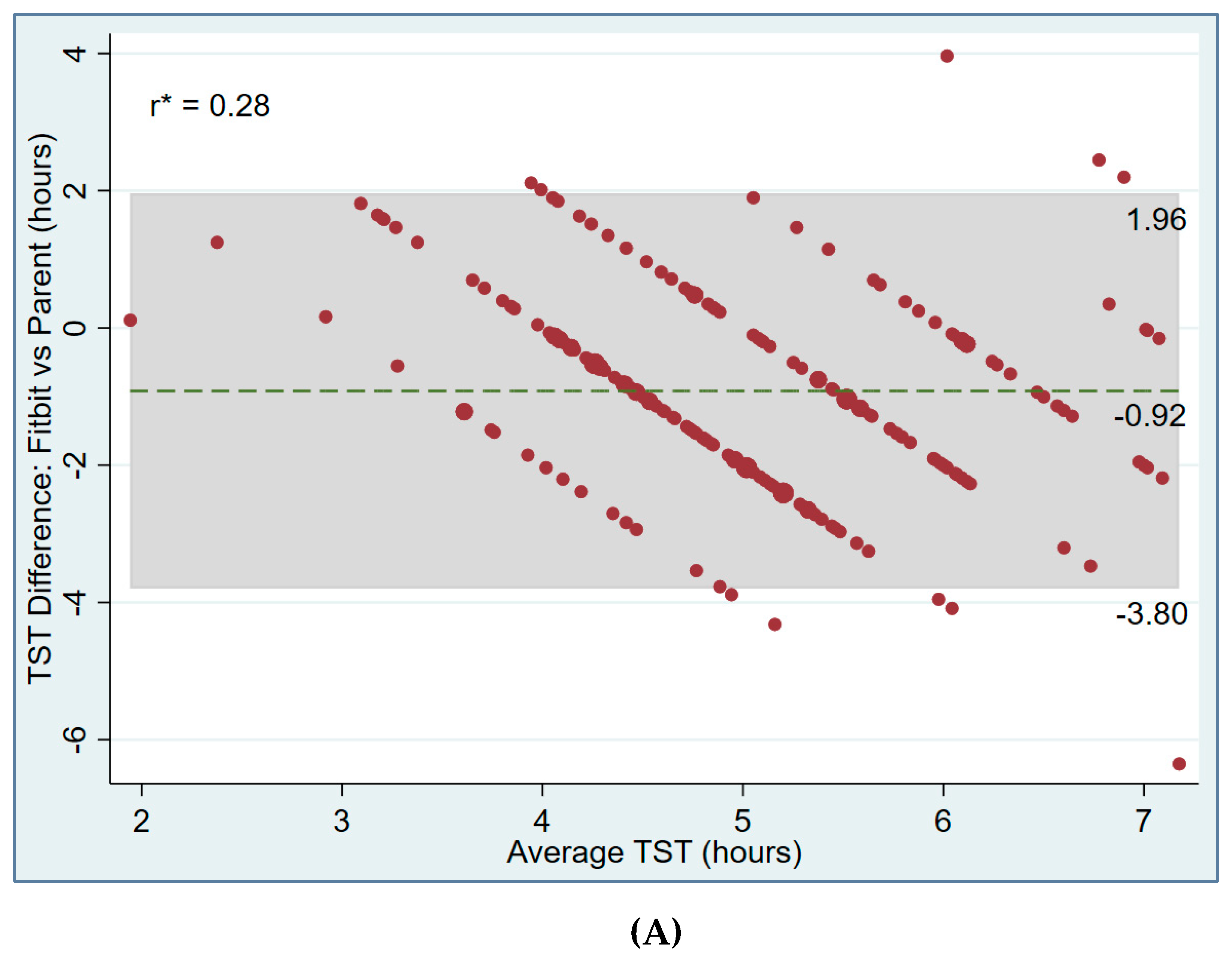

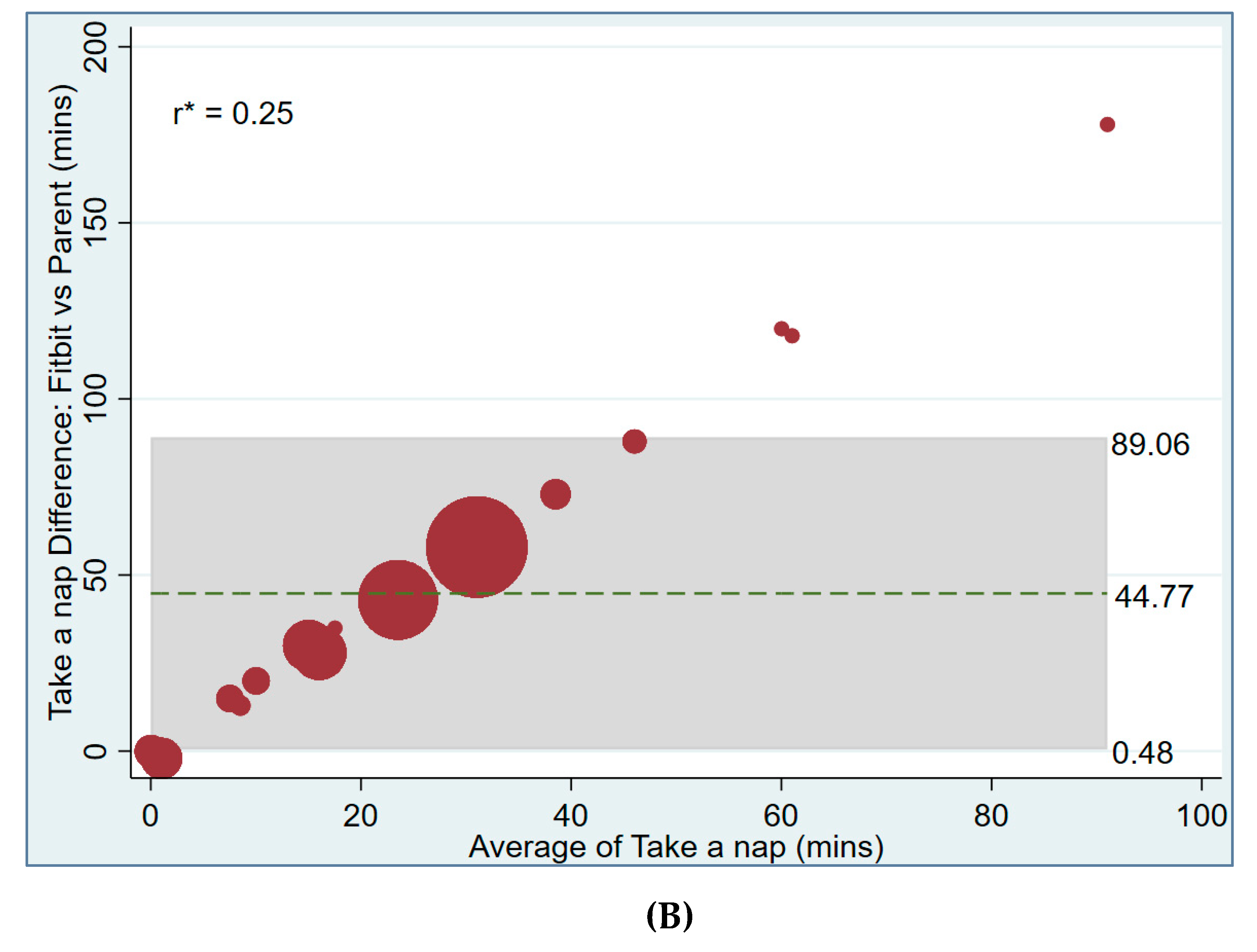

Table 5 shows a statistically significant and weak correlation (r = 0.28) between total sleep time (TST) recorded via Fitbit and face-to-face interview, as well as for nap time (r = 0.25).

A Bland–Altman plot shows the level of agreement between total sleep time (TST) recorded via Fitbit and face-to-face interview [mean difference (hours): - 0.92; range of agreement (hours): - 3.8 to 1.96] (

Figure 4A), and another shows the same for nap time [mean difference (minutes): 44.77; range of agreement (minutes): 0.48 to 89.06] (

Figure 4B).

The comparison between the two groups of Sleep Score (good and bad) and sleep satisfaction (satisfied and dissatisfied) was 79.9%, and the assessed Kappa index was 0.02 (weak). The WASO index shows that the level of agreement between Fitbit and the questionnaire was very low (50.98%), with Kappa = - 0.04, which is not statistically significant (p = 0.856). The results show that the two methods were almost in disagreement in assessing the time of wakefulness in the sleep cycle (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

The EMIB study employed two assessment tools to evaluate sleep quality in breastfeeding mothers one month postpartum. This allowed for comparison of the tools in community research. The study serves as a significant pilot for exploring the link between breastfeeding practices and maternal health, which will be discussed in a separate paper.

The correlation between sleep duration measured by Fitbit and self-reported sleep in our study was weak (r = 0.28; p < 0.001). This correlation is substantially lower than that observed in populations with stable sleep patterns, such as young adults in Lee’s study [

20] (r = 0.55) and children in Brazendale [

21] (r = 0.71), as well as lower than the correlation between Fitbit and EEG reported by Kawasaki [

13] (r = 0.83). Fitbit measures total sleep time through constant monitoring of sleep stages, while self-reports rely on personal perception, which can misrepresent sleep duration for mothers with disrupted sleep after childbirth.

The study found a low agreement (50.98%) between Fitbit data and subjective questionnaires regarding wake time during sleep (WASO), with a κ coefficient of -0.04 and no statistical significance (p = 0.856). These results are like those of Dong X [

22] on subjects with characteristics of chronic sleep disorders, comparing the Fitbit Charge 4 device with the gold standard PSG. The authors found that the Fitbit device's WASO measurements were not significantly different from PSG but had low specificity (62.2%) in identifying wakefulness. This indicates that it often overlooks brief wakeful moments. While it can accurately track total sleep time, its ability to assess sleep quality and disturbances is limited when only using the device. Thus, caution is advised for interpreting results, particularly in individuals with disrupted sleep, like postpartum mothers who experience frequent awakenings.

The study found a weak correlation (r = 0.25; p < 0.001) between nap durations tracked by Fitbit and those reported by users, making data analysis more difficult. Fitbits record sleep stages only after a certain duration is met for heart rate to stabilize. In our sample, it failed to capture naps shorter than 54 minutes, suggesting that many short naps commonly reported by participants may have been overlooked. This limitation aligns with previous findings showing that wearable devices often fail to detect naps under 1 hour [

23], which likely contributes to the weak agreement between objective and self-reported measures.

The agreement between the Fitbit Sleep Score and the participants' self-reported sleep satisfaction was low (concordance % = 79.9; Kappa = 0.02). In adults, Schyvens [

8] reported a moderate agreement between Fitbit Charge 5 and PSG, with a Kappa of 0.41. While Haghayegh [

24] found a Kappa of 0.54 comparing Fitbit with EEG, noting high sensitivity (95%) but only moderate specificity (57%). These results reveal that wearable devices have limitations in accurately measuring sleep. Differences between device readings and personal experiences can occur because the Sleep Score is derived from an internal algorithm that doesn't always match how someone feels about their sleep. In postpartum women, disrupted sleep from frequent waking at night makes self-reported total sleep and perceived sleep quality even less accurate. Supporting this, Young Lin (2025) [

23] using the Fitbit device, which demonstrated a significant and prolonged reduction total sleep time, including deep and REM sleep postpartum, reflecting a pattern of fragmented and less restorative sleep. Postpartum women often experience disrupted sleep due to nighttime childcare, leading them to feel they are not getting enough quality sleep, even if their total sleep duration isn't significantly lower. A meta-analysis showed that total sleep time and sleep efficiency decreased after childbirth for both fathers and mothers, with increased wake-up time after sleep onset [

25]. The majority of causes of decreased sleep time are due to natural physiological changes as well as anatomical changes that return mothers' bodies to a non-pregnant state [

26]. In addition, breastfeeding practices as nighttime feeding may also be associated with shortened nighttime sleep duration [

27], and the need to breastfeed after sleep onset negatively affects sleep duration in the first months of life [

28].

In summary, Fitbit measures sleep quality using factors like sleep duration, interruptions, and stages, which suit the general population. However, for postpartum individuals, sleep is often disrupted by the baby's needs and breastfeeding schedules. Both Fitbit and surveys may miss or misjudge personal sleep details. For instance, short naps might go undetected by the device, and the survey's results depend on personal memory. Thus, any tool used should be thoughtfully applied, and findings should be understood within the postpartum context instead of normal adult sleep standards.

New point in applicability: This research involves a large community sample and gathers data over four days and three nights during everyday activities, improving its representativeness. The results show that each assessment method has distinct advantages and disadvantages for certain metrics. Furthermore, the study suggests improving sleep algorithms in wearable devices to better fit the physiological and behavioral characteristics of breastfeeding mothers. These findings can help researchers choose more appropriate tools and guide sleep and mental health policies for postpartum mothers.

Limitation of study: Information bias may be inherent due to the structured nature of the interview, which necessitates recall from participants. We have analyzed awakenings during sleep in general, assuming that they have the same effect on the mother. This may be a potential bias from a scientific perspective, as natural awakenings are different from active awakenings for breastfeeding. This research shows that the two methods for assessing sleep quality differ, but it doesn't prove which one is better.

5. Conclusion

The study findings indicate that, despite a statistically significant relationship between the two methods for measuring sleep duration and napping, their association is weak. Specifically, concordance is minimal between the Fitbit Sleep Score and the sleep satisfaction levels obtained from direct interviews, as evidenced by a Kappa index that suggests nearly no agreement. It is necessary to perform additional studies utilizing a "diagnostic test study" framework with a gold standard for evaluating sleep quality, such as polysomnography, to reassess the efficacy of both research instruments among mothers engaged in breastfeeding.

Author contributions

All authors have remarkably contributed to the formation of study concepts, the study design, data collection, and data analysis and interpretation; participated in writing or editing important contents; approved the final report for publication; and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the research work.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work received support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) under the project titled "Education and Research Capacity Building Project at University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City", conducted from 2023 to 2025 (Project No. 2021-00020-3). The authors thank all members for their participation in this study implementation, as well as all the doctors and staff of University Medical Center's Healthy Child Clinic at Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam, for their support.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm there is no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Purkiewicz A, Regin KJ, Mumtaz W, Pietrzak-Fiećko R. Breastfeeding: The Multifaceted Impact on Child Development and Maternal Well-Being. Nutrients. 2025;17(8):1326. [CrossRef]

- Geddes DT, Gridneva Z, Perrella SL, Mitoulas LR, Kent JC, Stinson LF, et al. 25 Years of Research in Human Lactation: From Discovery to Translation. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3071. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, Taneja S, Bhandari N, Rollins N, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(467):96-113. [CrossRef]

- Ruan H, Zhang Y, Tang Q, Zhao X, Zhao X, Xiang Y, et al. Sleep duration of lactating mothers and its relationship with feeding pattern, milk macronutrients and related serum factors: A combined longitudinal cohort and cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:973291. [CrossRef]

- Smith JP, Forrester RI. Association between breastfeeding and new mothers' sleep: a unique Australian time use study. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Astbury L, Bennett C, Pinnington DM, Bei B. Does breastfeeding influence sleep? A longitudinal study across the first two postpartum years. Birth. 2022;49(3):540-8. [CrossRef]

- Manconi M, van der Gaag LC, Mangili F, Garbazza C, Riccardi S, Cajochen C, et al. Sleep and sleep disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: The Life-ON study. Sleep Med. 2024;113:41-8. [CrossRef]

- Schyvens AM, Peters B, Van Oost NC, Aerts JM, Masci F, Neven A, et al. A performance validation of six commercial wrist-worn wearable sleep-tracking devices for sleep stage scoring compared to polysomnography. Sleep Adv. 2025;6(2):zpaf021. [CrossRef]

- Jungquist CR, Mund J, Aquilina AT, Klingman K, Pender J, Ochs-Balcom H, et al. Validation of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Sleep Questions. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(3):301-10. [CrossRef]

- FititInc. Fitbit Charge 6; activity tracker 2025 [11/06/2025]. Available from: https://store.google.com/us/product/fitbit_charge_6?hl=en-US.

- Biczuk B, Żurek S, Jurga S, Turska E, Guzik P, Piskorski J. Sleep Stage Classification Through HRV, Complexity Measures, and Heart Rate Asymmetry Using Generalized Estimating Equations Models. Entropy. 2024;26(12):1100.

- Liang Z, Chapa Martell MA. Validity of Consumer Activity Wristbands and Wearable EEG for Measuring Overall Sleep Parameters and Sleep Structure in Free-Living Conditions. J Healthc Inform Res. 2018;2(1-2):152-78. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki Y, Kasai T, Sakurama Y, Sekiguchi A, Kitamura E, Midorikawa I, et al. Evaluation of Sleep Parameters and Sleep Staging (Slow Wave Sleep) in Athletes by Fitbit Alta HR, a Consumer Sleep Tracking Device. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:819-27. [CrossRef]

- Eylon G, Tikotzky L, Dinstein I. Performance evaluation of Fitbit Charge 3 and actigraphy vs. polysomnography: Sensitivity, specificity, and reliability across participants and nights. Sleep Health. 2023;9(4):407-16. [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Wu X, Jiang H, Zhang X. Validation of the relationship between rapid eye movement sleep and sleep-related erections in healthy adults by a feasible instrument Fitbit Charge2. Andrology. 2024;12(2):365-73. [CrossRef]

- What's sleep score in the Fitbit app. Available online: https://support.google.com/fitbit/answer/14236513?hl=en&ref_topic=14236503&sjid=7732201167484965670-NC2025 (accessed on day month year).

- Krahn LE, Arand DL, Avidan AY, Davila DG, DeBassio WA, Ruoff CM, et al. Recommended protocols for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test in adults: guidance from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(12):2489-98. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychologial Bulletin, 112 (1), 155-159. 1992.

- Altman, DG. Some common problems in medical research. Practical statistics for medical research: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1990. p. 396 - 435.

- Lee JM, Byun W, Keill A, Dinkel D, Seo Y. Comparison of Wearable Trackers' Ability to Estimate Sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6). [CrossRef]

- Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Perry MW, Tyler EB, Hunt ET, et al. Comparing measures of free-living sleep in school-aged children. Sleep Med. 2019;60:197-201. [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Yang S, Guo Y, Lv P, Wang M, Li Y. Validation of Fitbit Charge 4 for assessing sleep in Chinese patients with chronic insomnia: A comparison against polysomnography and actigraphy. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0275287. [CrossRef]

- Young-Lin N, Heneghan C, Liu Y, Schneider L, Niehaus L, Haney A, et al. Insights into maternal sleep: a large-scale longitudinal analysis of real-world wearable device data before, during, and after pregnancy. EBioMedicine. 2025;114:105640. [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh S, Khoshnevis S, Smolensky MH, Diller KR, Castriotta RJ. Performance assessment of new-generation Fitbit technology in deriving sleep parameters and stages. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37(1):47-59. [CrossRef]

- Parsons L, Howes A, Jones CA, Surtees ADR. Changes in parental sleep from pregnancy to postpartum: A meta-analytic review of actigraphy studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2023;68:101719. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan G, Tadi P. Physiology, Postpartum Changes. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Prasanna Tadi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls PublishingCopyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Kendall-Tackett K, Cong Z, Hale T. The Effect of Feeding Method on Sleep Duration, Maternal Well-being, and Postpartum Depression. Clinical Lactation. 2011;2:22-6. [CrossRef]

- Touchette E, Petit D, Paquet J, Boivin M, Japel C, Tremblay RE, et al. Factors associated with fragmented sleep at night across early childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):242-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).