Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

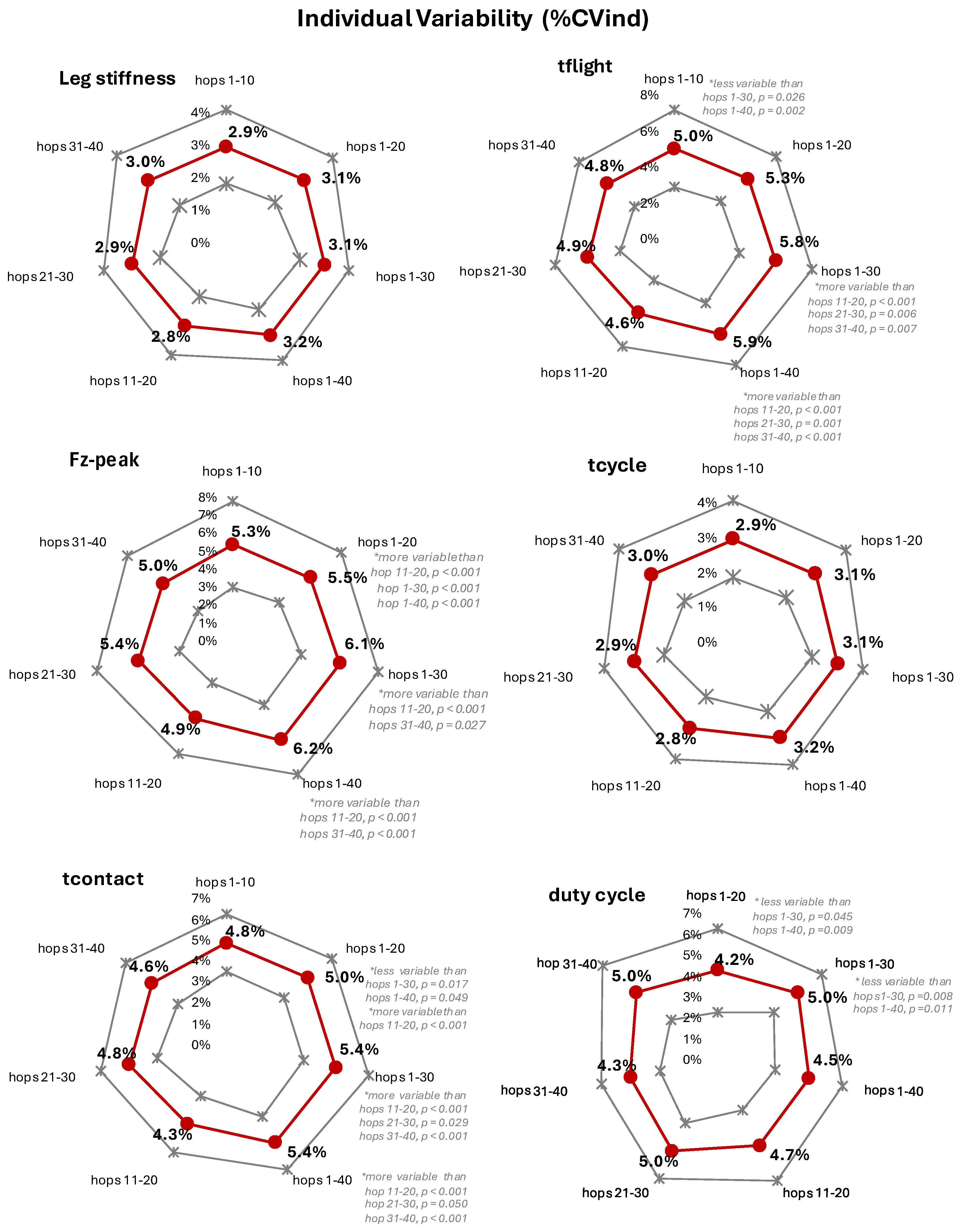

Two-legged hopping is a well-established model for assessing leg stiffness; however, in existing studies, it is unclear whether the trial segment selection affects the results. This study aimed to assess if the selected hopping segment alters the value and individual variability (%CVind) of leg stiffness and kinetic performance metrics. Elite women athletes (42, volleyball, basketball, handball) and 14 non-athletic women performed barefoot two-legged hopping (130 bpm) on a force-plate (Kistler, 9286AA, sampling at 1000Hz). Leg stiffness was estimated from the Fz registration (resonant frequency method). Four cumulative range segments (1–10, 1–20, 1–30, 1–40 hops) and three segments of 10-hop subranges (11–20, 21–30, 31–40) were analyzed (repeated measures one-way Anova, p ≤ 0.05, SPSS v30.0). The hopping segment did not significantly alter the leg stiffness value (segment average 30.6 to 31.2 kN/m) or its %CVind (segment average ≈3%). The kinetic performance metrics depicted a solid foundation for the extracted leg stiffness value, with %CVind not exceeding 6.2%. The results indicate a data collection of just 15 hops, in continuance reduced to a 10 hops segment (after excluding the first five ones to avoid neuromuscular adaptation) as a robust reference choice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Double-Legged Hopping Task

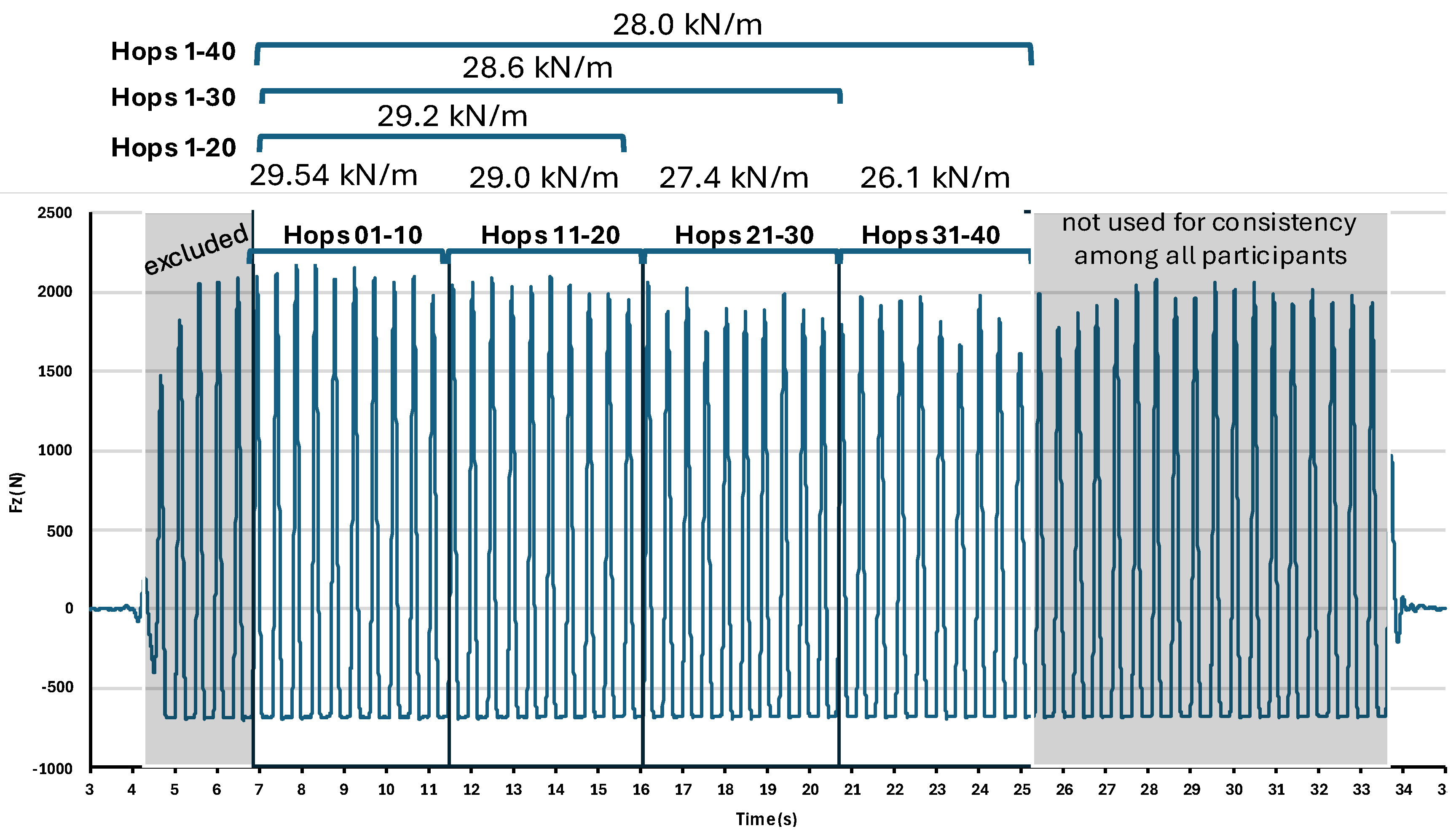

2.4. Hopping Segment Extraction

2.5. Performed Frequency Against the Set Frequency of 130 bpm

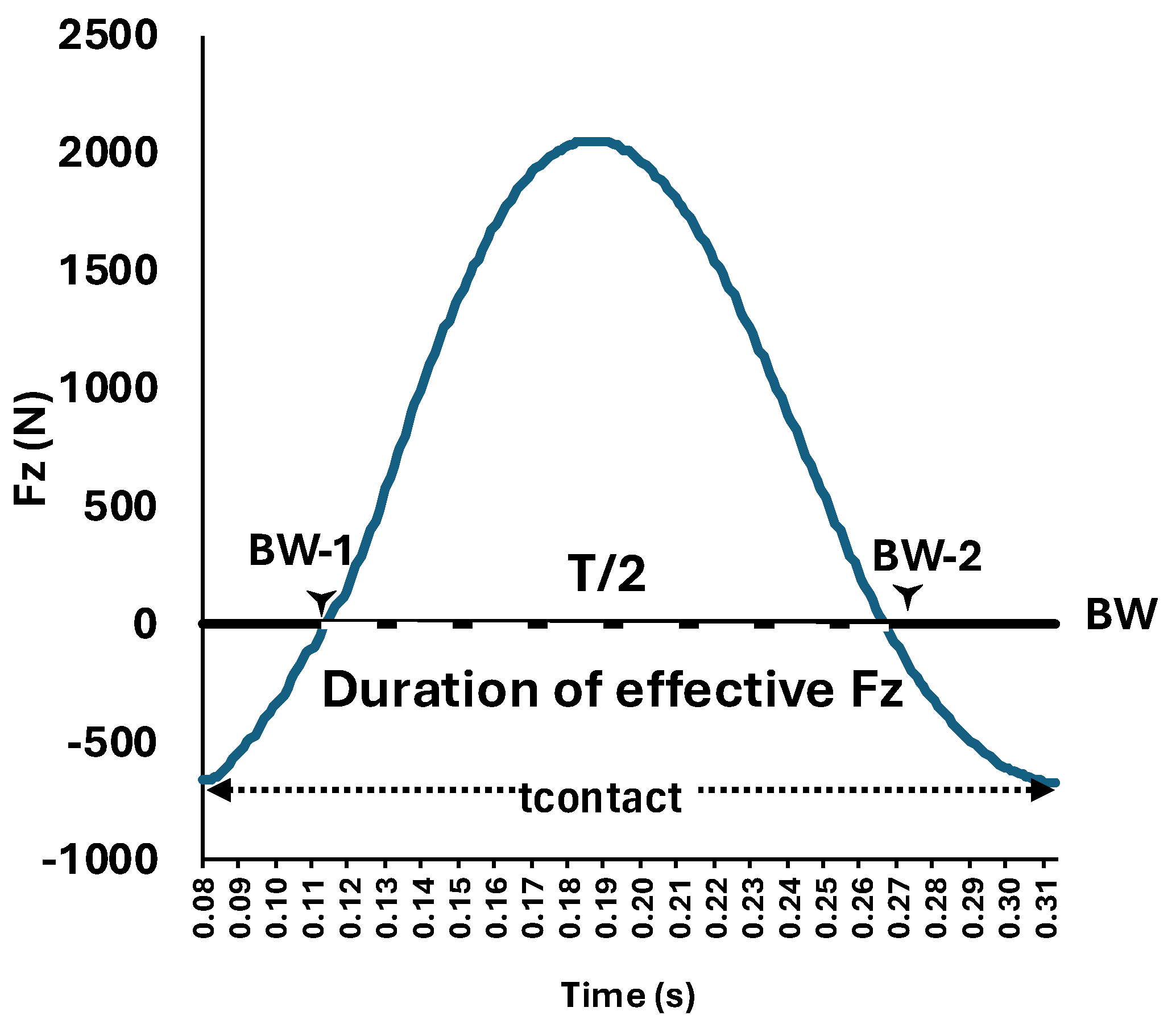

2.6. Variable Extraction

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group X Segment Interaction

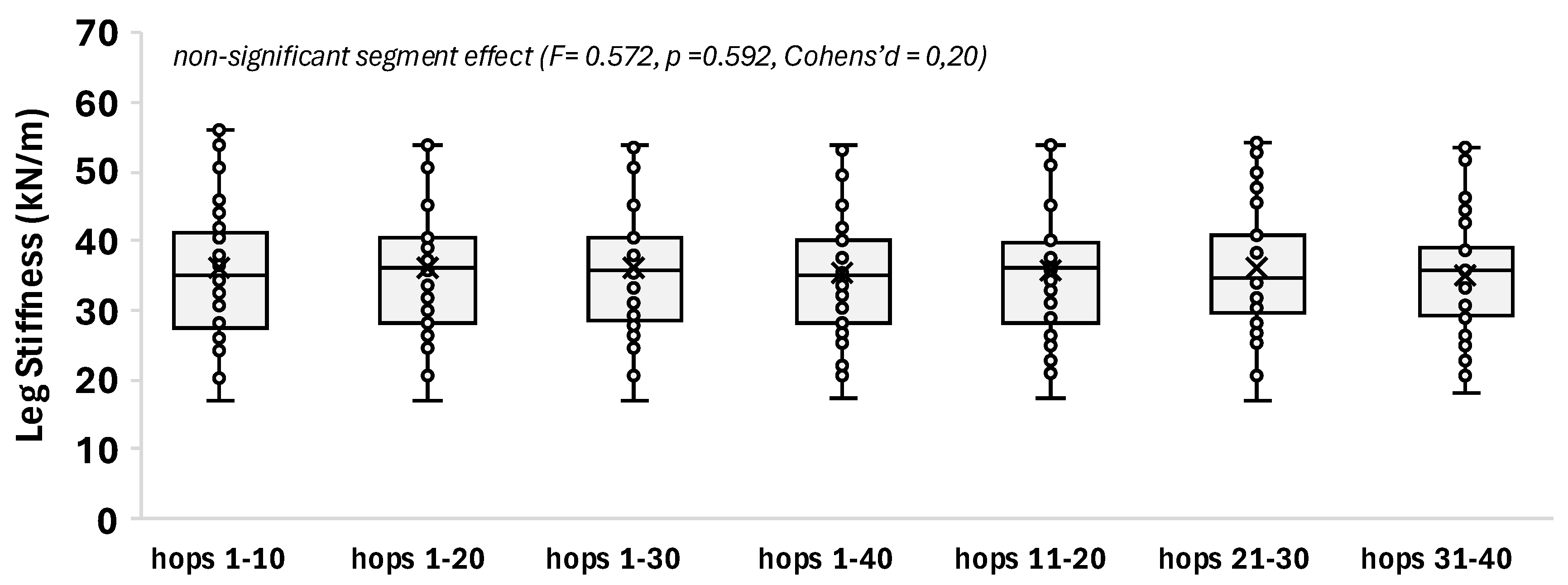

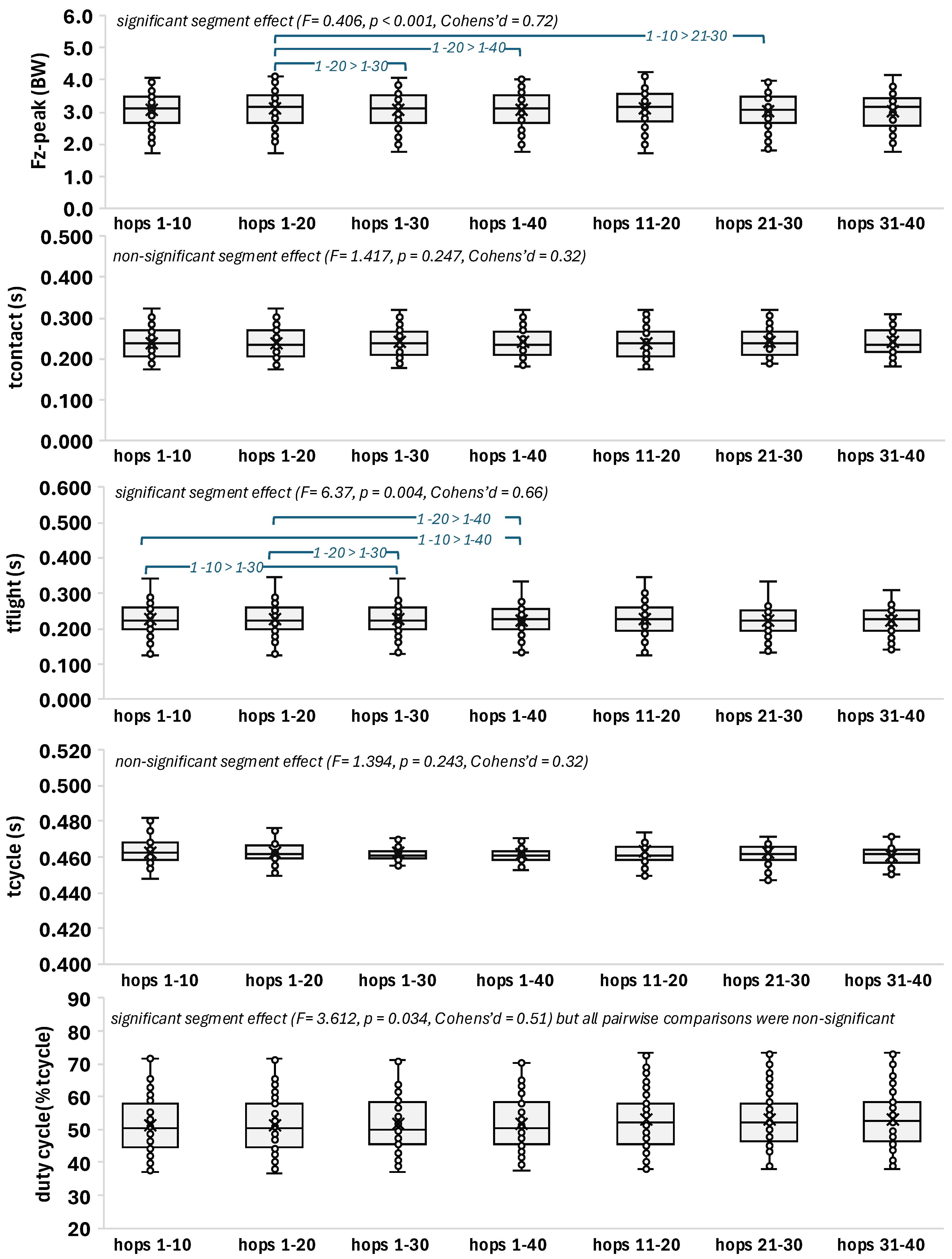

3.2. Segment Effect

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GRF | Ground Reaction Force |

| bmp | beats per minute |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

Appendix A

|

Stiffness KN/m |

Fz-Peak (BW) |

tcontact (s) |

tflight (s) |

tcycle (s) |

duty cycle (%tcycle) | |

| hops 1-10 | 31.08 ± 8.87 | 3.09 ± 0.57 | 0.240 ± 0.037 | 0.228 ± 0.043 | 0.470 ± 0.026 | 51.4 ± 8.2 |

| hops 1-20 | 31.11 ± 8.59 | 3.10 ± 0.57 | 0.239 ± 0.037 | 0.227 ± 0.043 | 0.470 ± 0.024 | 51.4 ± 8.3 |

| hops 1-30 | 31.07 ± 8.60 | 3.08 ± 0.56 | 0.240 ± 0.037 | 0.226 ± 0.042 | 0.468 ± 0.023 | 51.6 ± 8.2 |

| hops 1-40 | 30.64 ± 7.92 | 3.07 ± 0.55 | 0.240 ± 0.036 | 0.225 ± 0.041 | 0.467 ± 0.022 | 51.7 ± 8.0 |

| hops 11-20 | 31.13 ± 8.40 | 3.11 ± 0.58 | 0.239 ± 0.037 | 0.227 ± 0.043 | 0.467 ± 0.022 | 51.4 ± 8.3 |

| hops 21-30 | 31.00 ± 8.72 | 3.03 ± 0.55 | 0.241 ± 0.037 | 0.222 ± 0.040 | 0.465 ± 0.020 | 52.0 ± 7.9 |

| hops 31-40 | 30.65 ± 7.69 | 3.03 ± 0.55 | 0.241 ± 0.035 | 0.222 ± 0.038 | 0.437 ± 0.192 | 52.1 ± 7.7 |

|

Group X Segment Interaction |

F = 0.795 p = 0.592 |

F = 1.177 p = 0.326 |

F = 1.656 p = 0.142 |

F = 0.844 p = 0.489 |

F = 0.940 p = 0.429 |

F = 1.553 p= 0.177 |

| Segment Effect across the total of participants (N=56) | ||||||

| F | 0.572 | 8.406 | 1.417 | 6.037 | 1.394 | 3.612 |

|

Sig. (Greenhouse correction for all) |

0.592 | < 0.001* | 0.247 | 0.004* | 0.243 | 0.034* non-significant pairwise comparisons |

|

Cohen’s d effect size 0.20 = small 0.50 = medium 0.80 = large [Cohen, 1988]** |

0.20 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

| small |

medium to large |

small to medium |

medium |

small to medium |

medium | |

| Partial Eta Squared | 0.010 | 0.133 | 0.025 | 0.099 | 0.025 | 0.062 |

| Noncent. Parameter | 1.340 | 16.230 | 2.841 | 11.110 | 1.415 | 6.666 |

| Observed Powera | 0.151 | 0.956 | 0.299 | 0.855 | 0.214 | 0.632 |

| Pairwise Segment Comparisons |

ns for all | 1-20 > 1-30 > 1-40 > 21-30 |

ns for all | 1-10 > 1-30 > 1-40 1-20 >1-30 > 1.40 |

ns for all | ns for all |

Appendix B

|

KN/m (%) |

Fz -Peak (%) |

tcontact (%) |

tflight (%) |

tcycle (%) |

duty cycle (%) |

|

| hops 1-10 | 8.2 ± 2.0 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.5 |

| hops 1-20 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.3 |

| hops 1-30 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 1.5 |

| hops 1-40 | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.9 ± 2.0 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| hops 11-20 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

| hops 21-30 | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.4 |

| hops 31-40 | 7.4 ± 2.2 | 5.0 ± 2.6 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 1.3 |

|

Group X Segment Interaction |

F = 8.928 p < 0.001 |

F = 2.673 p = 0.035 |

F = 1.492 p = 0.131 |

F = 0.639 p = 0.801 |

F = 1.177 p = 0.279 |

F = 0.975 p = 0.471 |

| Segment Effect across the total of participants (N=56) | ||||||

| F | 0.784 | 6.648 | 8.182 | 7.955 | 1.222 | 12.803 |

|

Sig. (Greenhouse correction for all) |

0.382 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.303 | <0.001* |

|

Cohen’s d effect size 0.20 = small 0.50 = medium 0.80 = large [Cohen, 1988]** |

0.20 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.97 |

| small | large | large | large | mediumto small | large | |

| Partial Eta Squared | 0.014 | 0.110 | 0.129 | 0.126 | 0.022 | 0.189 |

| Noncent. Parameter | 0.796 | 19.718 | 32.413 | 30.820 | 3.851 | 47.485 |

| Observed Powera | 0.141 | 0.970 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.332 | 1.000 |

| ns for all | ns for all | 1-20 > 11-20 > 21-30 > 31-40 1-30 > 11-20 > 21-30 > 31-40 1-40 > 11-20 > 21-30 > 31-40 |

1-10 < 1-30 < 1-40 1-30 > 11-20 >21-30 > 31-40 1-40 > 11-20 >21-30 > 31-40 |

ns for all | 1-10 < 1-30 < 1-40 1-20 < 1-30 < 1-40 1-30 > 11-20 > 21-30 > 31-40 1-40 > 11-20 > 21-30 > 31-40 |

|

References

- Blickhan, R. The spring-mass model for running and hopping. J. Biomech. 1989, 22, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.A.; Cheng, G.C. The mechanics of running: How does stiffness couple with speed? J. Biomech. 1990, 23, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalleau, G.; Belli, A.; Viale, F.; Lacour, J.-R.; Bourdin, M. A Simple Method for Field Measurements of Leg Stiffness in Hopping. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirbüken, I.; Yurdalan, S.U.; Savelberg, H.; Meijer, K. Gender specific strategies in demanding hopping conditions. . 2009, 8, 265–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farley, C.T.; Houdijk, H.H.P.; Van Strien, C.; Louie, M. Mechanism of leg stiffness adjustment for hopping on surfaces of different stiffnesses. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, A.; Hollywood, J.; Lamping, D.L.; Pease, C.T.; Chakravarty, K.; Silverman, B.; Choy, E.H.S.; Scott, D.G.; Hazleman, B.L.; Bourke, B.; et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and diagnostic uncertainty in the first year of polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobara, H.; Inoue, K.; Kanosue, K. Effect of Hopping Frequency on Bilateral Differences in Leg Stiffness. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J., Kim, J.Y., Lee, H.Y., Kim, Y.H. (2010). Leg Stiffness from Landing Methods of Hopping. In: Lim, C.T., Goh, J.C.H. (eds) 6th World Congress of Biomechanics (WCB 2010). August 1-6, 2010 Singapore. IFMBE Proceedings, vol 31. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Padua, D.A.; Carcia, C.R.; Arnold, B.L.; Granata, K.P. Gender Differences in Leg Stiffness and Stiffness Recruitment Strategy During Two-Legged Hopping. J. Mot. Behav. 2005, 37, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; Morgenroth, D.C. Leg stiffness primarily depends on ankle stiffness during human hopping. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, K.; Padua, D.; Wilson, S. Gender differences in active musculoskeletal stiffness. Part II. Quantification of leg stiffness during functional hopping tasks. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2002, 12, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, S.J.; Fletcher, I.M.; Richards, J. A comparison of methods to determine bilateral asymmetries in vertical leg stiffness. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 34, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C.T.; Farley, C.T. Human hopping on damped surfaces: strategies for adjusting leg mechanics. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, K.; Takeshita, D. Leg stiffness adjustment during hopping by dynamic interaction between the muscle and tendon of the medial gastrocnemius. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Kurihara, T.; Isaka, T. Bilateral deficit of spring-like behaviour during hopping in sprinters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 118, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobara, H.; Inoue, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ogata, T. A Comparison of Computation Methods for Leg Stiffness During Hopping. J. Appl. Biomech. 2014, 30, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, M.P.; Bradshaw, E.J.; Greene, D.A.; Naughton, G.A. The impact of data reduction on the intra-trial reliability of a typical measure of lower limb musculoskeletal stiffness. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 33, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B.H.; Su, Y.-H. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2013, 20, 403–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlet, M.; Williams, R.; Keller, P.E. Effects of pitch and tempo of auditory rhythms on spontaneous movement entrainment and stabilisation. Psychol. Res. 2018, 84, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobara, H.; Kanosue, K.; Suzuki, S. Changes in muscle activity with increase in leg stiffness during hopping. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 418, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, J.-B.; Dalleau, G.; Kyröläinen, H.; Jeannin, T.; Belli, A. A Simple Method for Measuring Stiffness during Running. J. Appl. Biomech. 2005, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, C.T.; Blickhan, R.; Saito, J.; Taylor, C.R. Hopping frequency in humans: a test of how springs set stride frequency in bouncing gaits. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991, 71, 2127–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.W.; Bradshaw, E.J.; Kemp, J.; Clark, R.A. The Interday Reliability of Ankle, Knee, Leg, and Vertical Musculoskeletal Stiffness During Hopping and Overground Running. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavagna, G.A. Force platforms as ergometers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1975, 39, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousanoglou, E.N.; Boudolos, K.D. Rhythmic performance during a whole body movement: Dynamic analysis of force–time curves. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2006, 25, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvitella, A.M.; Foster, K.L. On the variability and dependence of human leg stiffness across strides during running and some consequences for the analysis of locomotion data. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, N.; Decker, L.M. Human movement variability, nonlinear dynamics, and pathology: Is there a connection? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2011, 30, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.D.; Collins, D.R.; Bingham, G.P. Perceptual coupling in rhythmic movement coordination: stable perception leads to stable action. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 164, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komi, P.V. Stretch-shortening cycle: a powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábrica, G.; López, F.; Souto, A. Effects of power training in mechanical stiffness of the lower limbs in soccer players. Rev. Andal. de Med. del Deport. 2015, 8, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.J.; Crowell, H.P., III; Davis, I.M. Lower extremity stiffness: implications for performance and injury. Clin. Biomech. 2003, 18, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, E.L.; Moresi, M.P.; Watsford, M.L.; Taylor, P.G.; A Greene, D. Variations in lower body stiffness during sports-specific tasks in well-trained female athletes. Sports Biomech. 2018, 20, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Trial Segments |

Mean ± SD (p value for one sample t-test with 130 bpm as test value) |

One Way Anova for Group Effect |

|||||

| Volley (N=14) | Basket (N=14) | Handball (N=14) | Control (N=14) | TOTAL (N=56) | F | Sig. | |

| hops 1-10 | 126.6 ± 8.6 (0.161) |

130.6 ± 3.0 (0.430) |

129.2 ± 2.3 (0.216) |

129.9 ± 3 (0.863) |

129.1 ± 5.0 (0.174) |

1.793 | 0.160 |

| hops 1-20 | 126.9 ± 8.1 (0.182) |

130.9 ± 3.0 (0.275) |

129.0 ± 2.9 (0.221) |

130 ± 2.5 (1.000) |

129.2 ± 4.9 (0.232) |

1.822 | 0.155 |

| hops 1-30 | 127.2 ± 7.9 (0.211) |

131.3 ± 2.7 (0.101) |

129.5 ± 1.9 (0.346) |

129.9 ± 2.2 (0.907) |

129.5 ± 4.6 (0.400) |

2.034 | 0.121 |

| Hops 1-40 | 127.8 ± 7.6 (0.293) |

131.4 ± 2.8 (0.098) |

129.4 ± 1.6 (0.205) |

130.0 ± 2.4 (1.000) |

129.6 ± 4.4 (0.544) |

1.657 | 0.188 |

| hops 11-20 | 127.2 ± 7.8 (0.199) |

131.2 ± 3.4 (0.189) |

128.8 ± 2.9 (0.138) |

129.9 ± 2.7 (0.848) |

129.3 ± 4.8 (0.259) |

1.880 | 0.144 |

| hops 21-30 | 127.9 ± 7.2 (0.287) |

132.0 ± 2.8 (0.061) |

130.2 ± 1.7 (0.748) |

129.1 ± 3.1 (0.314) |

129.8 ± 4.4 (0.711) |

2.335 | 0.085 |

| hops 31-40 | 129.1 ± 7.9 (0.681) |

131.6 ± 3.0 (0.071) |

130.1 ± 2.8 (0.907) |

128.9 ± 6.1 (0.502) |

129.9 ± 5.3 (0.915) |

0.704 | 0.554 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).