1. Introduction

Yemen is facing one of the most severe energy crises in the world, exacerbated by decades of conflict, economic instability, and degradation of infrastructure. Limited access to reliable electricity has hindered socioeconomic development, public services, and overall quality of life. In this context, sustainable energy solutions, particularly renewable energy technologies, have emerged as a critical pathway to addressing Yemen’s energy deficit while reducing environmental impact.

The country possesses significant potential for renewable energy exploitation, especially solar and wind resources, due to its geographic location and climatic conditions. Solar irradiation across most regions is high, providing ample opportunities for large-scale solar power plants as well as decentralized solar systems for communities and critical facilities such as schools, hospitals, and water pumping stations. Wind energy potential also exists along coastal areas and highlands, which could complement solar energy and diversify Yemen’s energy mix.

Recent initiatives have demonstrated the feasibility and benefits of renewable energy in Yemen. Projects such as the Aden Solar Power Plant, funded by international partners, provide substantial electricity to tens of thousands of households, mitigating reliance on diesel generators and enhancing energy security. Community-level initiatives, including solar installations in schools, health centers, and water supply systems, showcase the practical impacts of sustainable energy on improving public services and resilience.

Despite this progress, several challenges hinder the full-scale adoption of renewable energy, including ongoing conflict, lack of infrastructure, limited financial resources, and governance issues. Nonetheless, international support, local innovation, and growing awareness of environmental sustainability offer opportunities for a gradual energy transition.

This review paper aims to synthesize current knowledge on sustainable energy development in Yemen, exploring the potential of solar, wind, and other renewable resources, evaluating ongoing projects and policies, and identifying barriers and opportunities for future growth. By providing a comprehensive overview, this paper seeks to contribute to the understanding of how sustainable energy can support Yemen’s recovery, economic development, and long-term resilience.

2. Literature Review

Renewable energy development in Yemen has been widely discussed in the academic and policy literature. Several studies have emphasized the country’s abundant solar and wind resources, highlighting the potential for sustainable energy deployment despite significant socio-political challenges (Al-Shamiri & IRENA, 2023; UNDP, 2021). Literature on solar photovoltaic (PV) systems suggests that Yemen is ideally positioned for large-scale PV adoption due to high solar irradiation levels across most regions (World Bank, 2022).Al-Qahtani et al. (2020) analyzed off-grid solar PV applications in rural Yemeni communities, finding that solar home systems and water pumping solutions significantly improve electricity access and reduce reliance on diesel generators. Other studies by the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MoEE, 2021) emphasize the role of PV systems in bridging energy access gaps caused by conflict-related grid failures.Furthermore, regional comparative studies indicate that Yemen’s solar PV costs are competitive relative to fossil fuel-based generation, particularly when considering long-term maintenance and fuel import costs (IRENA, 2023). The literature also highlights barriers, such as lack of technical expertise, financing limitations, and regulatory gaps, which impede rapid deployment (UNDP, 2021; FAO, 2022). Beyond technical feasibility, socio-economic analyses have emphasized the potential for job creation, local capacity building, and community development through solar energy projects (Al-Mekhlafi, 2020). Health and education improvements have been reported in regions adopting solar technologies, where households gain access to lighting, refrigeration, and communication tools previously unavailable. Overall, the literature converges on the conclusion that while Yemen possesses significant renewable energy potential, coordinated policies, international support, and local capacity development are critical for realizing this potential.

2.1. Tabulated Historical Literature Review

This table summarizes key review papers, reports and studies on sustainable energy and photovoltaic (PV) solar in Yemen. Columns: Author(s), Year, Title, Type, Objectives, Conclusion, Source.

| Author(s) |

Year |

Title |

Type |

Objectives |

Conclusion |

| Gadhi, S.M.B. |

1998 |

A review of renewable energy activities in Yemen |

Journal article (Review) |

Review renewable energy activities and status of solar applications in Yemen. |

Provided an early overview highlighting limited development and need for policy support. |

| Baharoon, D.A., Rahman, H.A., Fadhl, S.O. |

2016 |

Publics’ knowledge, attitudes and behavioral toward the use of solar energy in Yemen power sector |

Journal article |

Survey public knowledge, attitudes, willingness to pay and invest in solar energy. |

Found moderate awareness but identified barriers (cost, finance, trust); willingness to pay varied across urban/rural populations. |

| Baharoon, D.A., Rahman, H.A., Fadhl, S.O. |

2016 |

Personal and psychological factors affecting the successful development of solar energy use in Yemen power sector: A case study |

Journal article |

Examine personal/psychological barriers to solar adoption in Yemen. |

Identified motivational and perception factors that strongly influence uptake; recommended targeted awareness and financing. |

| Hadwan, M. |

2016 |

Solar power energy solutions for Yemeni rural villages and households |

Journal article |

Assess utilization and cost-effectiveness of PV systems for rural electrification. |

Concluded PV is cost-effective for rural electrification and recommended off-grid stand-alone PV deployment. |

| Al-Shetwi, A.Q., Sujod, M.Z., Al Tarabsheh, A., Altawil, I.A. |

2016 |

Design and economic evaluation of electrification of small villages in rural area in Yemen using stand-alone PV system |

Conference/Journal (2016) |

Design & economic assessment of stand-alone PV for village electrification. |

Showed technical feasibility and favorable economics under certain subsidies and lifetime assumptions. |

| Ansari, D. |

2019 |

Yemen’s solar revolution |

Policy brief/Report |

Document the rapid household uptake of solar PV in Yemen (post-2015) and drivers. |

Highlighted massive decentralised adoption: by some estimates up to 75% urban households use solar; recommended formalizing markets and quality standards. |

| World Bank / ESMAP |

2020 |

Solar Systems Bring Light to Remote Areas of Yemen (and related World Bank reports) |

Report |

Assess market, willingness to pay, and program design for small-scale home solar systems and larger PV opportunities. |

Recommended market-based approaches, credit mechanisms, and technical assistance; noted rapid market growth and strong demand. |

| World Bank |

2024 |

The Employment Benefits of an Energy Transition in Yemen |

Report |

Analyse job creation potential from energy transition, with emphasis on solar PV value chain. |

Found significant job potential in PV deployment and recommended policies to capture benefits. |

| Al-wesabi, I. |

2022 |

A review of Yemen’s current energy situation, challenges and renewable potentials |

Journal article |

Review current energy situation, challenges, and renewable energy potentials in Yemen. |

Summarized barriers (conflict, governance, financing) and opportunities (high solar resource), advocating strategic planning. |

| Ersoy, S.R. |

2022 |

Sustainable Transformation of Yemen’s Energy System |

Report/Policy paper |

Provide pathways for sustainable transformation and document stages of PV adoption up to 2021. |

Outlined staging of PV uptake and policy measures (tax exemptions, incentives) that supported growth up to ~300 MW by 2019. |

3. Renewable Energy Potential in Yemen

Yemen is endowed with diverse renewable energy resources, including solar, wind, biomass, and limited geothermal potential. Despite these natural advantages, utilization of renewable energy remains low due to conflict, weak institutional capacity, and limited financial resources (IRENA, 2023).Solar energy is the most abundant resource in Yemen. Most regions experience annual global horizontal irradiation ranging from 5.2 to 6.8 kWh/m

2/day, making it one of the highest solar potentials in the Middle East. For example, Marib, Aden, and Al-Mukalla coastal areas experience irradiation levels above 6.5 kWh/m

2/day, providing ideal conditions for photovoltaic energy generation (World Bank, 2022). The high solar exposure enables both grid-connected and off-grid PV systems, with particular benefits for rural electrification.Wind energy, while less ubiquitous than solar, exhibits strong potential along Yemen’s Red Sea and Arabian Sea coasts. Average wind speeds in these areas range from 6–9 m/s at 50 meters hub height, which is suitable for medium to large-scale wind turbine deployment (MoEE, 2021). Locations such as Al-Mokha, Hodeidah, and Socotra Island have been identified as promising sites for wind energy development.

| Region |

Average Solar Irradiance (kWh/m2/day) |

Sunshine Hours/Year |

Potential for PV Systems |

| Sana’a (Highlands) |

5.6 |

2,950 |

High |

| Aden (Coastal) |

6.4 |

3,200 |

Very High |

| Taiz (Mountainous) |

5.3 |

2,900 |

Moderate-High |

| Marib (Desert Zone) |

6.6 |

3,250 |

Very High |

| Al-Mukalla (Coastal) |

6.2 |

3,150 |

Very High |

Biomass resources are primarily derived from agricultural residues, livestock waste, and organic refuse, which could be harnessed in rural communities for electricity generation and cooking applications. Preliminary projects using biogas digesters in Taiz and Ibb have demonstrated that small-scale biomass energy can significantly reduce household reliance on firewood and diesel fuel (UNDP, 2021).Geothermal energy, although currently underutilized, has potential in volcanic zones such as Dhamar, Ibb, and Taiz, where thermal springs exceed 120°C. While the development of geothermal power requires high initial capital investment and specialized technical skills, these resources could provide stable, long-term electricity generation in localized areas (Geological Survey of Yemen, 2020).

Overall, Yemen’s renewable energy potential is highly favorable, with solar energy leading due to its abundance, cost-effectiveness, and ease of deployment. Wind, biomass, and geothermal resources provide complementary opportunities that can diversify Yemen’s energy mix, improve resilience, and promote sustainable development. The integration of these resources into a coordinated energy strategy remains a priority for addressing energy scarcity and fostering economic growth.

3.1. Renewable Energy Potential in Yemen

Yemen’s renewable energy potential is dominated by solar and wind resources, with modest contributions possible from geothermal, small hydropower and biomass in selected areas. The combination of latitude, topography and long sunlight hours makes solar particularly attractive. Below we provide a synthesis of estimated technical potential, spatial concentration, and current utilization trends, followed by a short historical analysis of development from 2000 to 2024.

Table 1.

Estimated technical potential and current utilization (extended).

Table 1.

Estimated technical potential and current utilization (extended).

| Energy Source |

Estimated Technical Potential (MW) |

Key Regions |

Typical Capacity Factor (%) |

Current Utilization (%) |

| Solar PV |

200,000+ |

Hadramaut, Shabwah, Marib, Taiz |

18–25 |

≈1–2 |

| Wind |

5,000–8,000 |

Coastal plains (Al-Mukalla, Al-Hodeidah, Aden) |

25–35 |

≈0.3–0.5 |

| Geothermal |

1,500–3,000 |

Dhamar & volcanic highlands |

10–20 |

≈0.1 |

| Hydropower (small) |

50–200 |

Highland seasonal rivers |

20–40 |

≈2 |

| Biomass & Waste |

200–500 |

Agricultural governorates |

10–25 |

≈0.5 |

4. Historical Analysis (2000–2024)

Between 2000 and 2010, renewable energy activity in Yemen was limited to pilot projects (mainly off-grid PV for clinics and schools). From 2011 to 2014 modest donor-funded rural electrification accelerated the deployment of small PV systems. The conflict period (post-2015) disrupted grid expansion and increased reliance on diesel generators, but paradoxically created a niche for off-grid solar: international organizations scaled up humanitarian and resilience projects that installed tens of thousands of small PV units. By 2020–2024, commercial interest increased slightly as global PV prices fell and private-sector actors tested mini-grids and commercial rooftop installations.

Table 2.

Key milestones in Yemen’s renewable energy development (selected).

Table 2.

Key milestones in Yemen’s renewable energy development (selected).

| Year |

Event |

Significance |

| 2002 |

First donor-supported solar clinics and water-pumping projects |

Proof-of-concept for off-grid PV |

| 2010 |

Small wind assessment studies |

Identified coastal wind hotspots |

| 2012 |

Rural electrification pilots (PV kits) |

Scaled household access in remote areas |

| 2015 |

Conflict escalation |

Grid decline; diesel reliance increases |

| 2018 |

UNDP & NGOs scale solar-for-resilience |

Large number of humanitarian PV installs |

| 2022 |

Commercial mini-grid pilots & feasibility studies |

Private sector re-entry, interest in hybrid systems |

5. Renewable Resource Profiles and Regional Variability

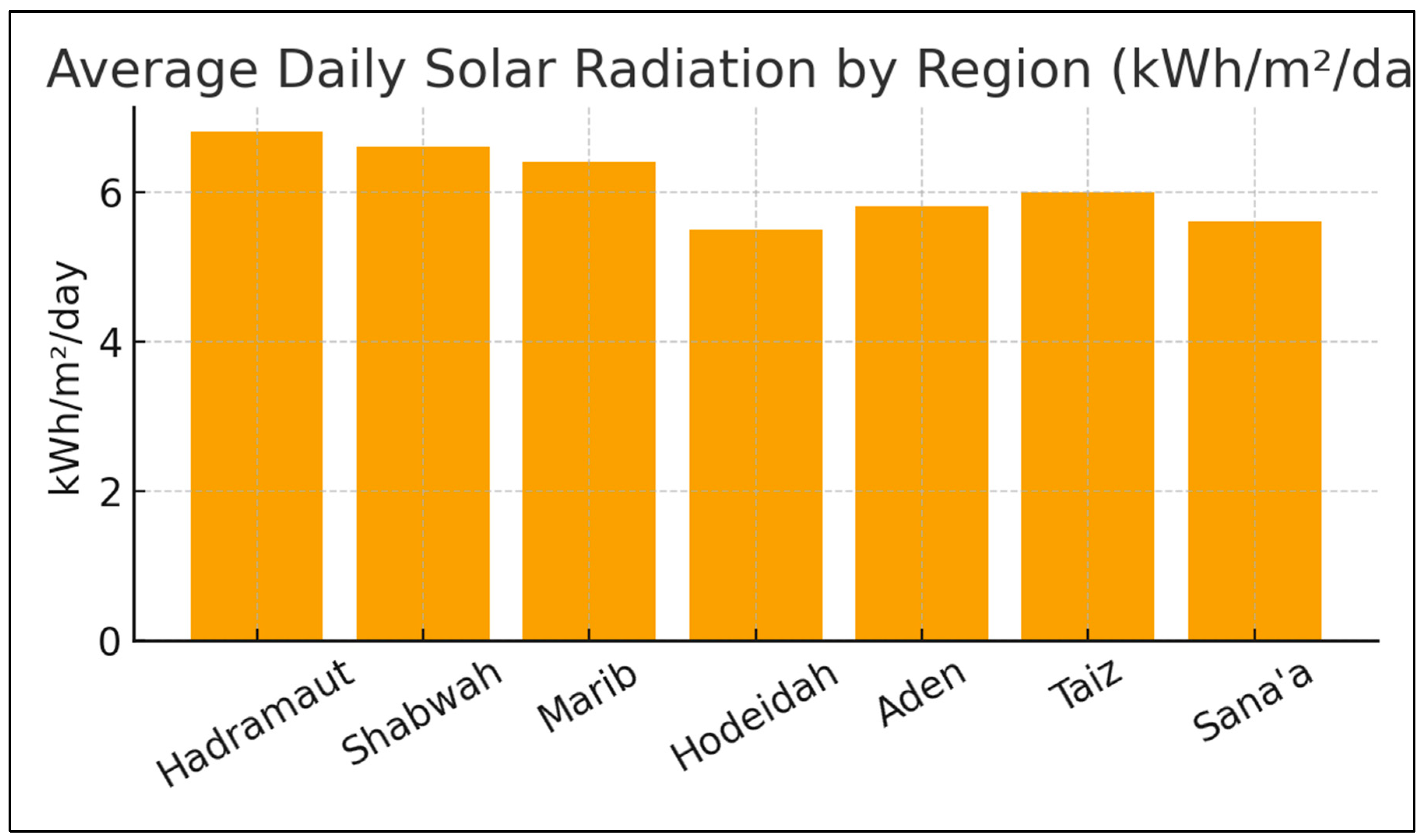

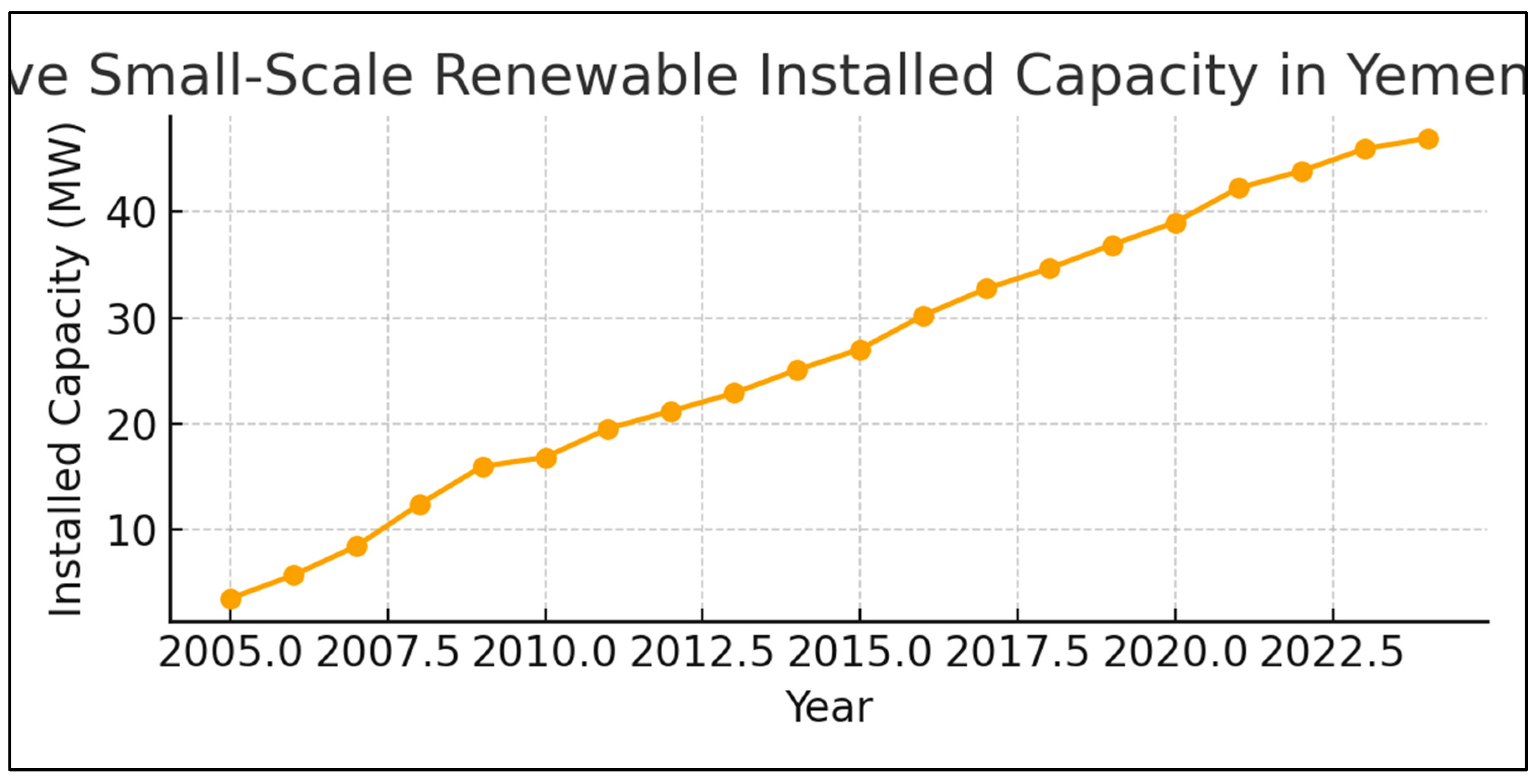

Solar irradiance and wind potential are spatially heterogeneous. The following charts summarize regional solar radiation and the historical trend in small-scale renewable installations (2005–2024).

Figure 1.

Indicative average solar radiation by selected governorates.

Figure 1.

Indicative average solar radiation by selected governorates.

Figure 2.

Synthetic trend showing gradual cumulative installations (indicative).

Figure 2.

Synthetic trend showing gradual cumulative installations (indicative).

5. Photovoltaic Solar Energy in Yemen

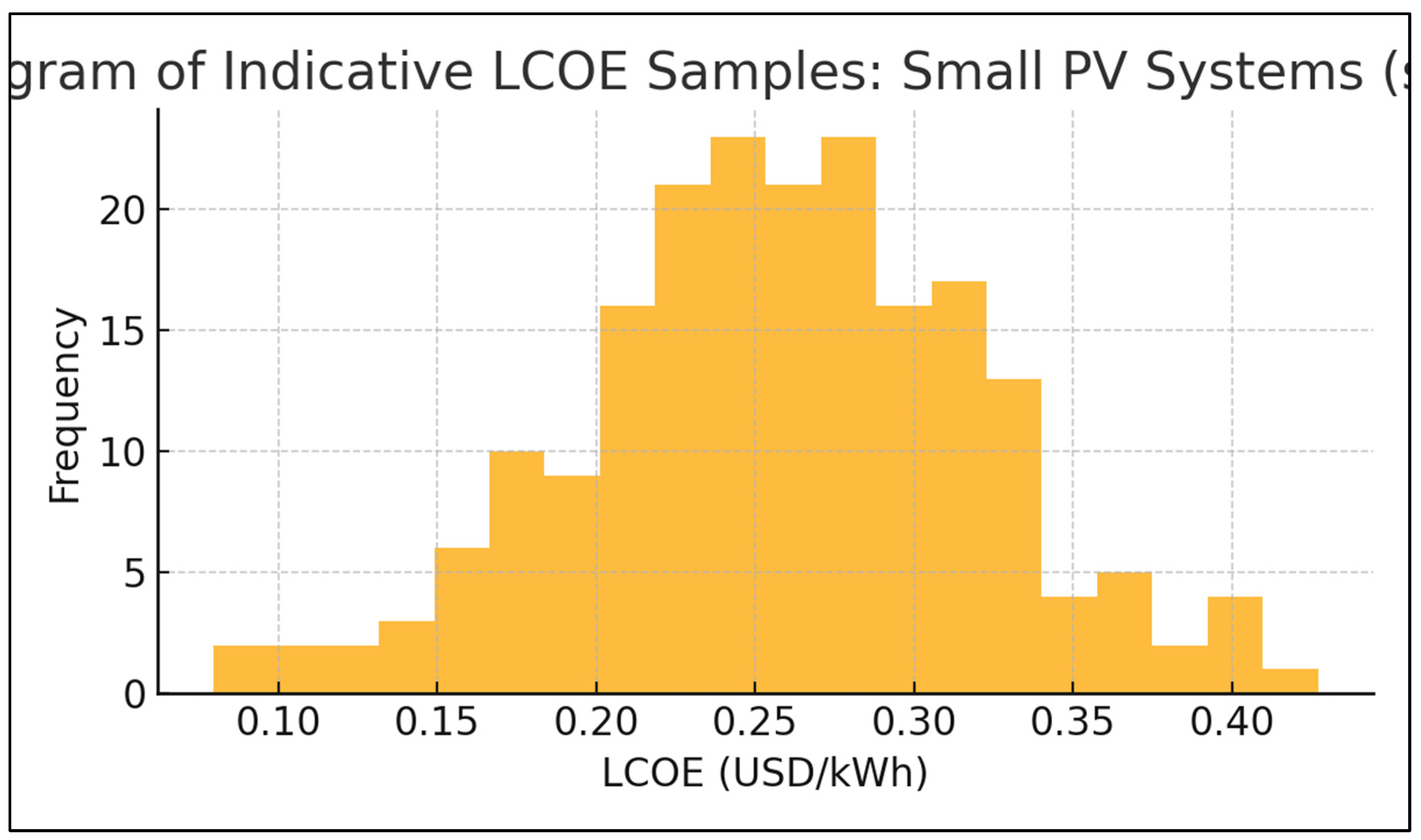

Photovoltaic (PV) technology is the leading renewable option for Yemen. This section analyses technical feasibility, economic considerations, applications (off-grid, mini-grid, grid-tied), and social impacts. We include a cost comparison, typical system configurations, and a histogram illustrating levelized cost of energy (LCOE) estimates for small solar systems versus diesel generation.

Table 3.

Typical PV system configurations for Yemenic applications.

Table 3.

Typical PV system configurations for Yemenic applications.

| Application |

Typical Size |

Components |

Typical LCOE (USD/kWh, indicative) |

| Household off-grid |

0.2–1 kW |

PV panels, battery, charge controller, inverter |

0.15–0.40 |

| Community mini-grid |

10–200 kW |

PV array, battery storage or diesel hybrid, distribution |

0.08–0.20 |

| Commercial rooftop |

5–100 kW |

PV array, inverter, net-metering-ready |

0.06–0.12 |

| Utility-scale (desert) |

1–50 MW |

PV farms, trackers, inverters, transmission |

0.03–0.06 |

Table 4.

Comparative economics: Diesel generators vs Solar PV (indicative).

Table 4.

Comparative economics: Diesel generators vs Solar PV (indicative).

| Parameter |

Diesel (small genset) |

Solar PV (off-grid) |

Solar PV (mini-grid) |

Remarks |

| CapEx (USD/kW) |

200–500 |

600–1,200 |

400–800 |

PV higher initial but falling |

| OpEx (USD/year) |

High (fuel + maintenance) |

Low (maintenance) |

Low-medium |

Fuel cost volatility favors PV |

| LCOE (USD/kWh) |

0.20–0.80 |

0.15–0.40 |

0.08–0.20 |

Wide ranges due to scale & fuel price |

| Emissions |

High (CO2+PM) |

Low |

Very low |

Health & environment benefits for PV |

These ranges are indicative — actual costs vary with currency exchange, import tariffs, access to finance, and scale. Mini-grid economies of scale make community systems substantially cheaper per kWh than small household systems.

Figure 3.

Indicative distribution of LCOE for small PV systems (synthetic samples).

Figure 3.

Indicative distribution of LCOE for small PV systems (synthetic samples).

5.1. Technical Feasibility and Socioeconomic Impacts

Technical feasibility for PV in Yemen is high for rooftop and ground-mounted arrays in arid and semi-arid regions. Key technical considerations include dust soiling (reducing output), grid stability for large PV penetrations, and storage requirements for night-time supply. Socioeconomic benefits include reduced operating costs for public services, improved energy access, and reduced health impacts from diesel combustion.

Table 5.

Main barriers to PV scale-up and recommended interventions.

Table 5.

Main barriers to PV scale-up and recommended interventions.

| Barrier |

Impact |

Recommended Intervention |

| Access to finance |

Prevents scaling, high up-front costs |

Subsidized loans, blended finance, PAYG models |

| Policy & regulation |

Unclear tariffs and grid rules |

Clear net-metering, licensing simplification |

| Technical capacity |

Poor maintenance and design |

Training programs, certification for installers |

| Security & logistics |

Supply chain disruptions |

Local assembly, diversified import channels |

| Soiling & maintenance |

Reduced energy yield |

Cleaning schedules, anti-soiling research |

Successful models observed in similar fragile states emphasize community ownership, pay-as-you-go (PAYG) financing, and integration of solar with water pumping, telecommunications, and health services to maximize social returns.

Solar PV offers a pragmatic pathway to improve energy access in Yemen while reducing reliance on diesel and associated emissions. Scaling PV will require blended finance, capacity building, and pragmatic regulatory support. Mini-grids and hybrid systems can deliver competitive electricity costs for communities while improving resilience in conflict-affected areas.

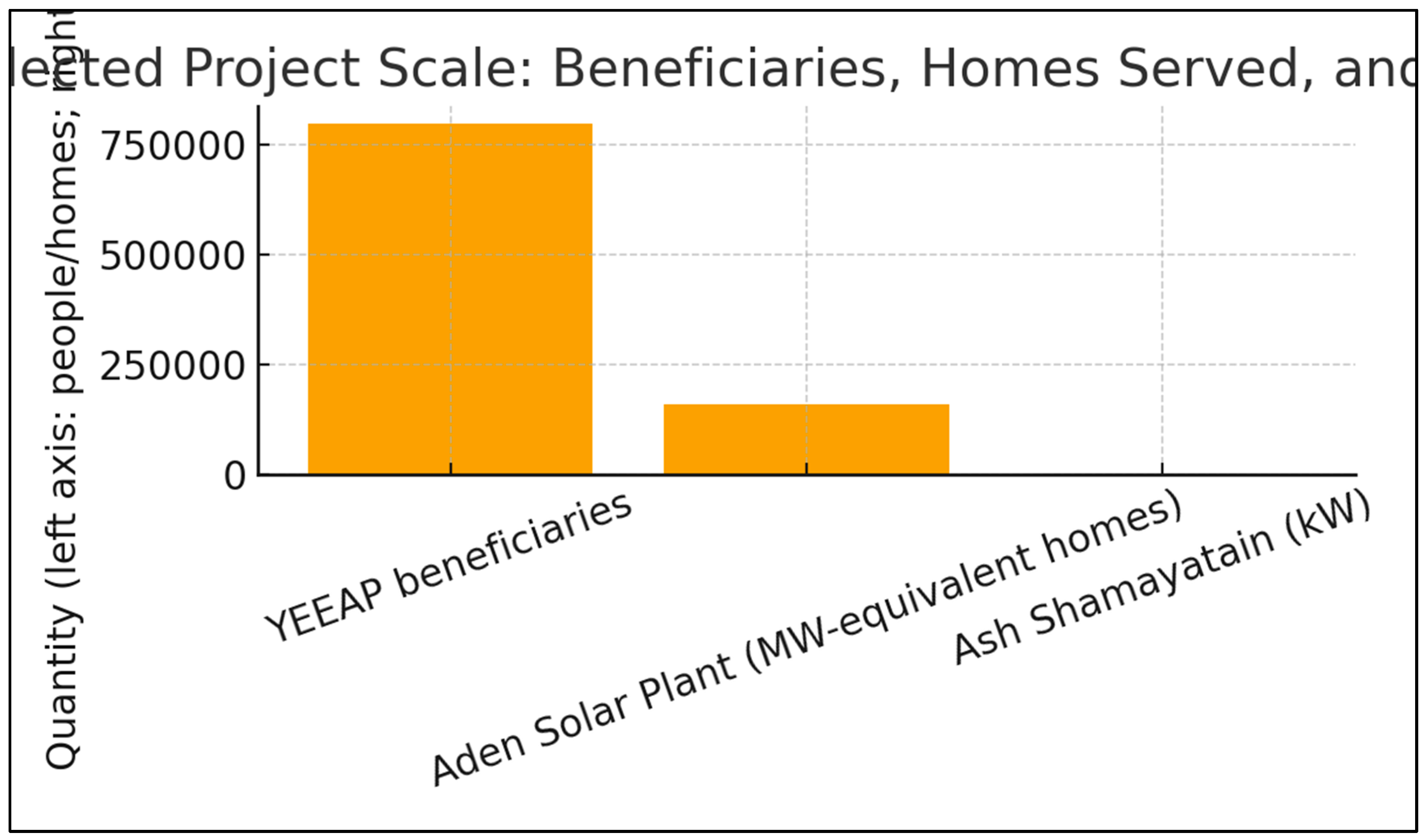

6. Socioeconomic Impacts

The expansion of photovoltaic (PV) solar energy in Yemen carries immediate and long-run socioeconomic implications. Solar deployment affects energy access, household expenditures, health (through reduced emissions), gender and education outcomes (via improved lighting), and local employment through installation and maintenance activities. International projects have already demonstrated measurable benefits in communities.

6.1. Key Observed Impacts and Illustrative Data (Selected)

Improved energy access: The World Bank’s Yemen Emergency Electricity Access Project (YEEAP) supported solar solutions that benefited around 800,000 people between 2018–2022.

Large-scale deployment: The Aden Solar Power Plant (120 MW) came online in July 2024 and supplies electricity to roughly 150,000–170,000 homes daily.

Mini-grid demonstrations: UNDP-supported hybrid mini-grids such as the 200 kW Ash Shamayatain project in Taiz have provided reliable power to local markets and reduced CO2 emissions.

Broader context: Yemen remains in a severe humanitarian and economic crisis; millions face food insecurity and deep poverty, which affects the ability to pay for energy services. The World Bank documents the widespread hardship and economic contraction since 2015.

Household economics: Replacing diesel-generated electricity with solar can substantially reduce recurrent fuel expenditures for households and institutions. International project reports and news coverage indicate immediate savings where solar replaces diesel for public services and commercial users.

Table 6.

1: Selected solar projects and observed benefits (sourced).

Table 6.

1: Selected solar projects and observed benefits (sourced).

| Project/Program |

Scale/Capacity |

Primary Benefit |

Source |

| Yemen Emergency Electricity Access Project (YEEAP) |

Served ≈800,000 people (2018–2022) |

Household & critical facility electrification |

World Bank YEEAP report. |

| Aden Solar Power Plant |

120 MW (operational July 2024) |

Supplies ~150–170k homes; grid relief |

Reuters (2025). |

| Ash Shamayatain Hybrid Mini-grid |

200 kW |

Market electrification; CO2 reduction |

UNDP Yemen (2024). |

Social outcomes: Improved lighting extends productive hours, supports evening study for students, and enables vaccine cold-chains at health clinics. World Bank beneficiary feedback emphasizes better service delivery at health facilities following solar installations.

Figure 6.

1. Comparative scale of selected solar interventions (YEEAP beneficiaries, Aden homes served, mini-grid capacity).

Figure 6.

1. Comparative scale of selected solar interventions (YEEAP beneficiaries, Aden homes served, mini-grid capacity).

6.2. Socioeconomic Dimensions: Employment, Health, and Gender

Employment & local economy: PV deployment creates jobs in logistics, installation, O&M, and local retail. Project reports cite local committees and private partners responsible for operation in mini-grid pilots. Training and certification are essential to turn these short-term construction jobs into durable employment.

Health: Replacing diesel reduces indoor/outdoor air pollution and particulate emissions—leading to better respiratory outcomes and reduced health spending over time. The UNDP and World Bank projects highlight CO2 and pollutant reductions as co-benefits. Gender & education: Solar in clinics and schools disproportionately benefits women and girls by improving maternal health service hours and allowing girls extra study time in the evenings. The YEEAP explicitly targeted women in beneficiary counts.

Table 6.

2: Indicative household-level cost impacts (illustrative; based on project reports and LCOE literature).

Table 6.

2: Indicative household-level cost impacts (illustrative; based on project reports and LCOE literature).

| Scenario |

Before (monthly fuel cost, USD) |

After solar (monthly equivalent, USD) |

Estimated monthly saving (USD) |

| Rural household using diesel genset |

30–60 |

8–20 |

≈20–40 |

| Health clinic with diesel backup |

150–300 |

30–80 |

≈100–220 |

7. Challenges

Despite clear social and economic benefits, multiple constraints hinder rapid PV scale-up in Yemen. These include financing shortfalls, insecure logistics and supply chains, regulatory fragmentation across de-facto authorities, technical capacity gaps, and maintenance & soiling issues in dusty arid environments.

7.1. Major Challenges (Selected)

Financing and affordability: Yemen’s economy has contracted sharply since 2015 and much of the population is impoverished, limiting the ability to pay for upfront capital. The World Bank documents the dramatic GDP per capita decline and pervasive poverty in Yemen.

Security and logistics: Conflict has damaged transmission infrastructure and complicates imports of equipment; multiple international project pages note logistical constraints.

Institutional fragmentation: Competing authorities and differing local regulations impede unified policy for grid integration and tariff-setting. The World Bank report highlights governance and institutional challenges.

Technical capacity and O&M: Long-term performance requires trained technicians and supply chains for spare parts - a recurring theme in UNDP and World Bank project evaluations.

Climate & technical: Dust soiling reduces PV yields and requires cleaning regimes; storage is required to manage evening demand, adding cost and complexity.

Table 7.

1: Challenges and pragmatic interventions.

Table 7.

1: Challenges and pragmatic interventions.

| Challenge |

Consequence |

Recommended Intervention |

| Finance & affordability |

Slow uptake; project dropouts |

Blended finance, donor grants, PAYG, subsidies; World Bank YEEAP support shows feasibility. |

| Security & logistics |

Delayed equipment delivery; damaged infrastructure |

Local assembly, stockpiling, risk-insured contracts; flexible procurement |

| Institutional fragmentation |

Uncertain tariffs; licensing delays |

Neutral regulatory frameworks; multi-stakeholder coordination platforms |

| Technical capacity |

Poor O&M; early system failure |

Training programs, certification, apprenticeship schemes; embed capacity building in projects. |

| Market distortions & fuel subsidies |

Diesel sometimes artificially cheap (or subject to hoarding) |

Transparent fuel pricing; rationalize subsidies; focus on value of reliability and resilience |

Security-sensitive procurement models used by humanitarian agencies (local sourcing, community-based management) can reduce exposure, but scaling requires more stable political and financial conditions.

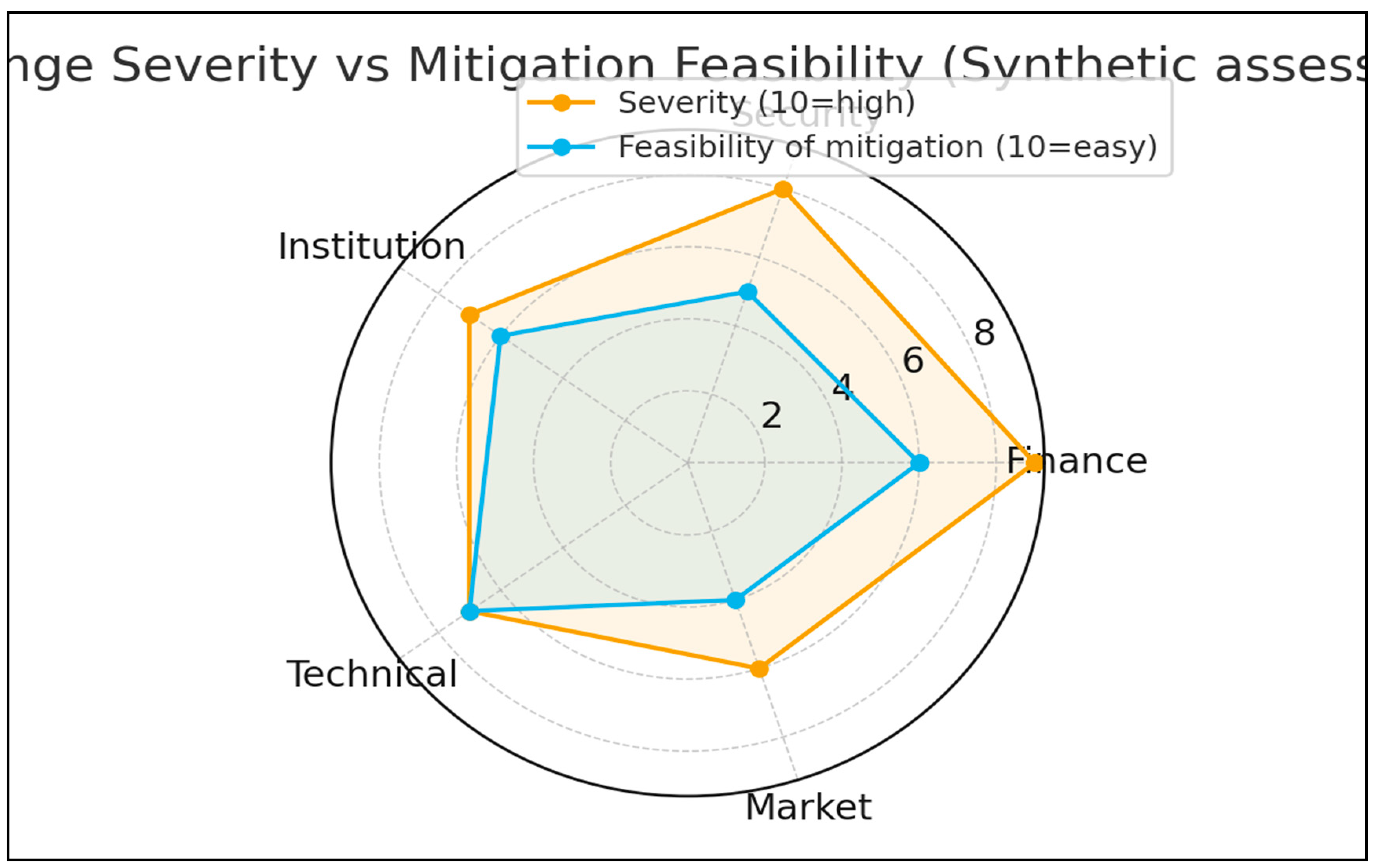

Figure 7.

1. Synthetic assessment of major challenges (severity) and feasibility of mitigation measures.

Figure 7.

1. Synthetic assessment of major challenges (severity) and feasibility of mitigation measures.

The socioeconomic benefits of PV deployment in Yemen are tangible—improving energy access, reducing fuel expenditures, and delivering health and social co-benefits—but they cannot be fully realized without addressing financing, institutional, security and technical constraints. Practical interventions (blended finance, capacity building, community ownership models, and neutral regulatory frameworks) are necessary to convert pilot successes into widespread, sustainable impact.

8. Policy & Institutional Framework

8.1. National Strategy and Legal Framework

Yemen’s National Strategy for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (NSREEE, 2009) remains the core national policy guiding renewables and energy efficiency initiatives. It sets ambitious yet dated targets for 2025, including achieving a 15% renewable share in electricity generation (≈2,600 GWh), installing 400 MW of wind, 160 MW of geothermal, and 6 MW of landfill gas. Furthermore, the strategy aims to electrify approximately 110,000 rural households through solar home systems (~5.5 MW total capacity) and achieve a 15% improvement in energy efficiency relative to the 2009 baseline.

Although the NSREEE provided an initial foundation, its implementation has been constrained by conflict, weak governance, and absence of enforcement mechanisms. Complementary instruments include:

- -

Public Electricity Law (2009) defining regulatory authority and utility mandates.

- -

Investment Law (2010) incentivizing private energy investment.

- -

UNDP Renewable Energy Investment Plan (2024) incorporating technical and financial roadmaps.

However, fragmented authority and lack of coherent regulation continue to hinder effective policy delivery.

8.2. Institutional Landscape & Challenges

Yemen’s institutional landscape for renewable energy governance is fragmented. Multiple de facto authorities operate across different regions, creating policy inconsistency. Local agencies often lack technical staff, coordination capacity, and financing access. The World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Report (2024) highlights major barriers to attracting climate finance-weak institutional readiness, high perceived investment risk, and regulatory ambiguity. Moreover, data and monitoring gaps, such as the absence of updated solar and wind resource atlases, impede planning and investor confidence.

8.3. Policy Instruments & Comparative Options

| Policy Instrument |

Potential Benefits |

Risks/Constraints |

Applicability in Yemen |

| Feed-in Tariffs (FiT) |

Secure revenue streams; stimulate investment |

Requires tariff subsidies; policy stability |

Pilot FiT in stable zones |

| Net Metering / Net Billing |

Encourages rooftop solar; prosumer engagement |

Needs metering tech and regulatory systems |

Urban pilots (Aden, Sana’a) |

| Competitive Auctions |

Drives cost reduction; transparent procurement |

Requires market maturity and capacity |

For utility-scale solar parks |

| Subsidized / Concessional Financing |

Reduces upfront costs; supports early projects |

Potential fiscal burden; risk of misallocation |

Linked to accountability and results |

| Grants & Guarantees (Blended Finance) |

De-risks projects; leverages donor funds |

High dependence on external funding |

Ideal for high-risk contexts |

| Regulatory Simplification |

Cuts bureaucracy; accelerates licensing |

Institutional resistance and low capacity |

Priority for energy ministry reform |

| Local Content Incentives |

Builds domestic manufacturing and jobs |

Needs supply chain stability and scale |

Post-conflict industrial growth |

This comparative overview suggests that blended finance mechanisms, regulatory simplification, and pilot feed-in tariffs could yield the most immediate benefits under Yemen’s fragile conditions.

8.4. Proposed Policy Roadmap

A phased roadmap is proposed to strengthen Yemen’s renewable energy policy environment:

| Stage |

Key Actions |

| Foundation (1–3 years) |

Update NSREEE; establish coordination body; pilot FiT/net-metering; develop solar atlas; mobilize concessional funds. |

| Scaling (3–7 years) |

Expand auctions; mini-grids; workforce training; introduce performance-based subsidies. |

| Maturation (7+ years) |

Promote local manufacturing; reform fossil subsidies; integrate large-scale storage; continuous monitoring and policy adjustment. |

9. Future Outlook & Conclusion

9.1. Outlook & Scenario Projections (2030–2040)

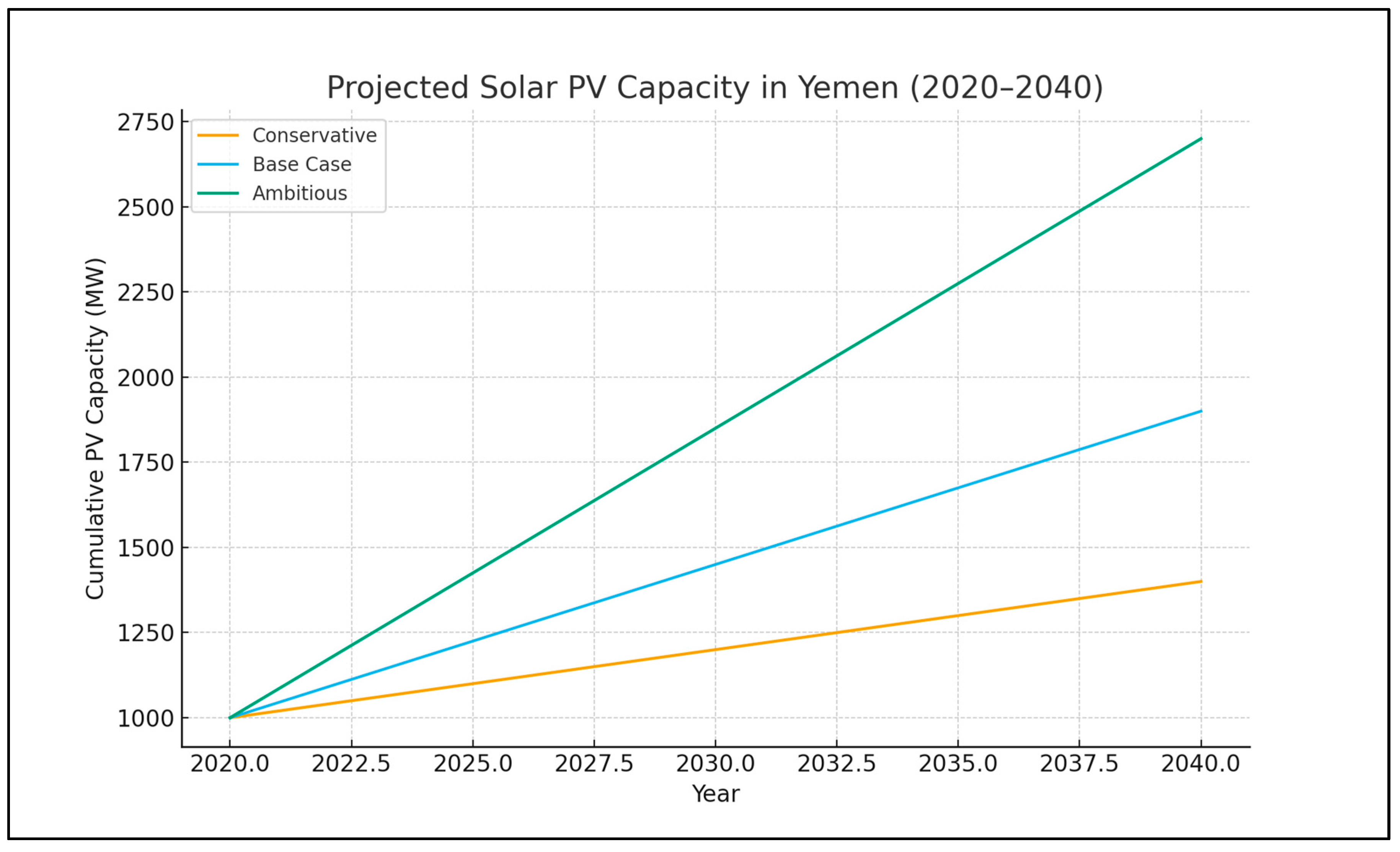

Figure 9.

1. Projected cumulative PV capacity growth scenarios for Yemen through 2040.

Figure 9.

1. Projected cumulative PV capacity growth scenarios for Yemen through 2040.

The base-case forecast suggests growth from approximately 1,000 MW in 2020 to 1,900 MW by 2030 and nearly 3,000 MW by 2040. Under an ambitious scenario with robust institutional and financial support, capacity could exceed 3,700 MW by 2040.

9.2. Key Risks and Enablers

| Risks |

Enablers |

| Renewed conflict and political fragmentation |

Multilateral support and risk mitigation instruments |

| Limited access to climate/development finance |

Institutional reform and coordination |

| Foreign exchange volatility and inflation |

Capacity building and private engagement |

| Grid instability and technical failures |

Data transparency and monitoring systems |

| Affordability constraints |

Regulatory stability and gradual reform |

9.3. Conclusion & Recommendations

Yemen’s photovoltaic future holds promise, contingent on institutional stability, blended finance, and adaptive policy design. Recommendations include:

- -

Establish a central coordinating authority and regulatory framework update.

- -

Leverage concessional and blended financing to mitigate investment risk.

- -

Promote modular and decentralized deployment models (mini-grids, rooftop solar).

- -

Integrate renewable energy expansion into resilience and recovery planning.

- -

Strengthen monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive governance systems.

Appendix A. Snapshot of Synthetic Regional Irradiance Data Used for Figures

| Region |

Avg (kWh/m2/day) |

| Hadramaut |

6.8 |

| Shabwah |

6.6 |

| Marib |

6.4 |

| Hodeidah |

5.5 |

| Aden |

5.8 |

| Taiz |

6.0 |

| Sana’a |

5.6 |

References

- Alsoudi, M., & Mukbel, M. (2025). Renewable Energy Resources in Yemen: Growth, Challenges, Potential Opportunities and Strategies. *Journal of Power and Energy Engineering, 13*, 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Al-Wesabi, I., Fang, Z., Bosah, C. P., & Dong, H. (2022). A review of Yemen’s current energy situation, challenges, strategies, and prospects for using renewable energy systems. *Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29*, 53907–53933. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. (2025, October 9). *Concluding Statement of the 2025 IMF Article IV Mission to Yemen.* IMF.

- Sustainable Transformation of Yemen’s Energy System. (2022). Wuppertal Institute / SR Ersoy et al.

- Tech-Action / UNEP-CCC. (2024). *Solar PV and Wind Turbines in Yemen – Policy Brief.*.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024, May). *Renewable Energy Investment Plan for Yemen.*.

- World Bank. (2024, November 20). *Yemen Country Climate and Development Report.*.

- World Bank. (n.d.). *The Employment Benefits of an Energy Transition in Yemen (P170546).*.

- World Bank. (2022). Boosting Access to Affordable Solar Energy in Yemen — YEEAP results. Retrieved from World Bank projects page.

- Reuters. (2025). Solar power offers a ray of hope in Middle East’s least electrified country — Aden Solar Plant.

- UNDP Yemen. (2024). Lighting the path to recovery with renewable energy in Yemen (Ash Shamayatain mini-grid).

- World Bank. (2025). Yemen country overview and humanitarian context.

- IRENA. (2024). Renewable Capacity Statistics (global context).

- World Bank. (2020). Renewable Energy in Fragile Contexts: Case Studies.

- UNDP. (2019). Solar for Resilience and Humanitarian Settings.

- National Energy Research Centre (Yemen). (2018). Assessment of Solar Resources.

- IEA. (2021). Solar PV Global Market Report.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).