1. Introduction

In recent decades, the inappropriate and excessive use of antibiotics has contributed to one of the greatest challenges in public health—antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [

1,

2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified AMR as one of the top ten global health threats, warning that uncontrolled antibiotic prescribing, particularly in pediatric populations, accelerates resistance and undermines the effectiveness of future treatments [

3].

Young children aged 1–7 years represent a particularly vulnerable group, as respiratory tract infections, otitis media, and urinary tract infections are among the most common causes of antibiotic prescriptions [

4,

5]. However, numerous studies have shown that a large proportion of prescriptions in this age group are unnecessary or inappropriate, frequently deviating from international clinical guidelines [

6,

7]. Early-life exposure to antibiotics has also been associated with disruption of the gut microbiota and potential long-term health effects, such as increased risk of allergies and obesity [

8,

9].

Across Europe, national monitoring systems and stewardship interventions have been established to optimize pediatric antibiotic use [

10,

11]. In contrast, in Kosovo, data remain scarce and fragmented. Existing studies have reported high antibiotic utilization in hospital settings, including pediatric wards, and frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics [

12,

13]. Yet, no comprehensive analysis has addressed prescribing practices in primary care, where most pediatric infections are treated. Furthermore, Kosovo currently lacks national pediatric prescribing guidelines, leaving physicians to rely on empirical practice or international references, which may contribute to variability and inappropriate prescribing.

Younger children (particularly those aged 1–3 years) are often more likely to receive antibiotics due to diagnostic uncertainty and parental expectations [

14,

15]. International research highlights that empirical antibiotic use in this age group is widespread, especially for respiratory tract infections, despite the fact that many of these infections are viral in origin [

16].

Against this background, it is crucial to examine the prescribing rate and patterns of antibiotic prescribing in Kosovo’s primary health care centers, which serve as the first point of contact for pediatric patients. By comparing two major municipalities, Prishtina and Ferizaj, this study aims to provide novel insights into local prescribing practices, identify gaps in adherence to international standards, and contribute evidence to support the development of national antibiotic stewardship initiatives.

2. Results

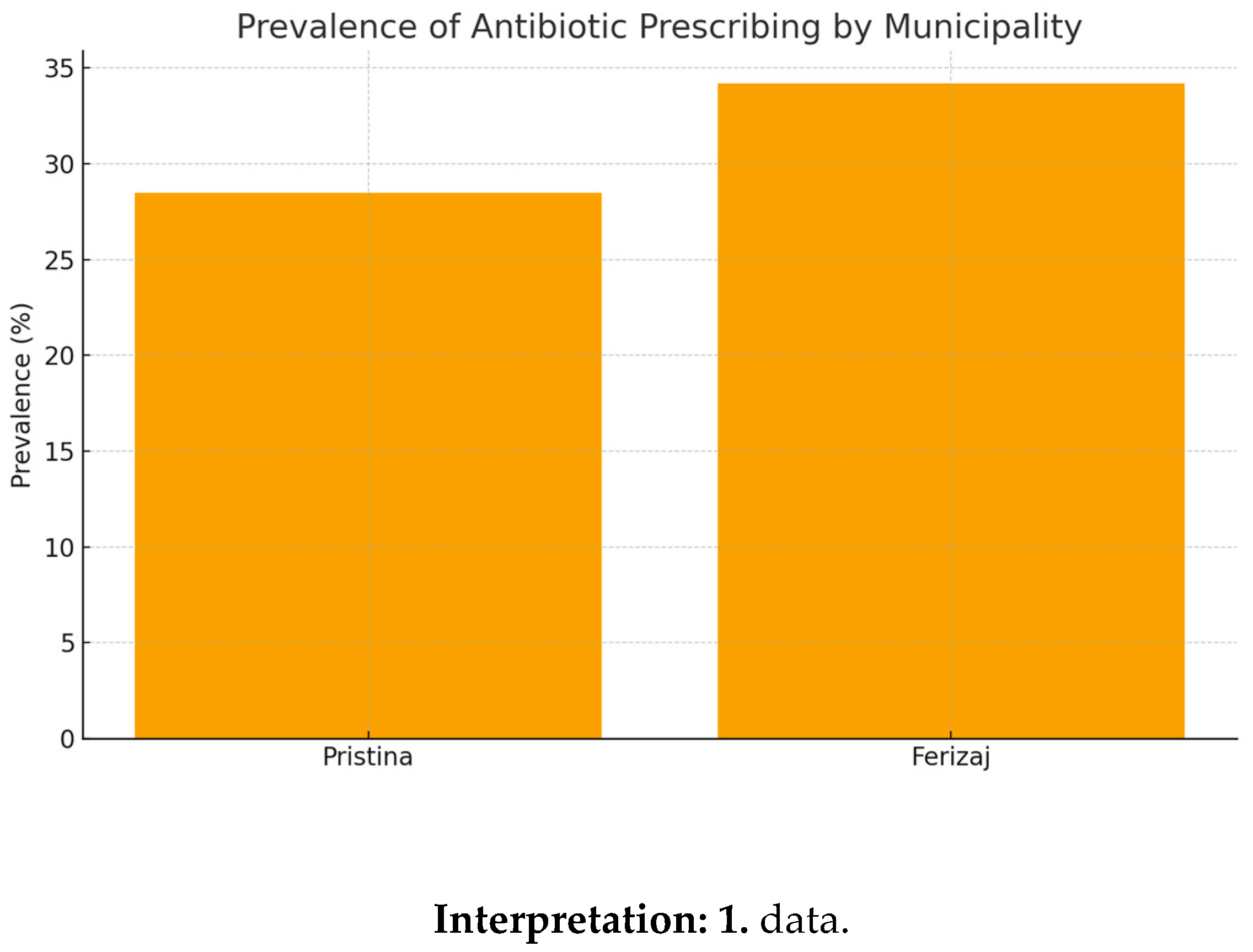

Explanation: This table demonstrates clear regional differences in prescribing practices. Children in Ferizaj were more likely to receive antibiotics than those in Pristina, suggesting potential influence of local clinical habits or parental demand. Prishtina vs Ferizaj prevalence: χ²= p<0.01, 95% CI difference

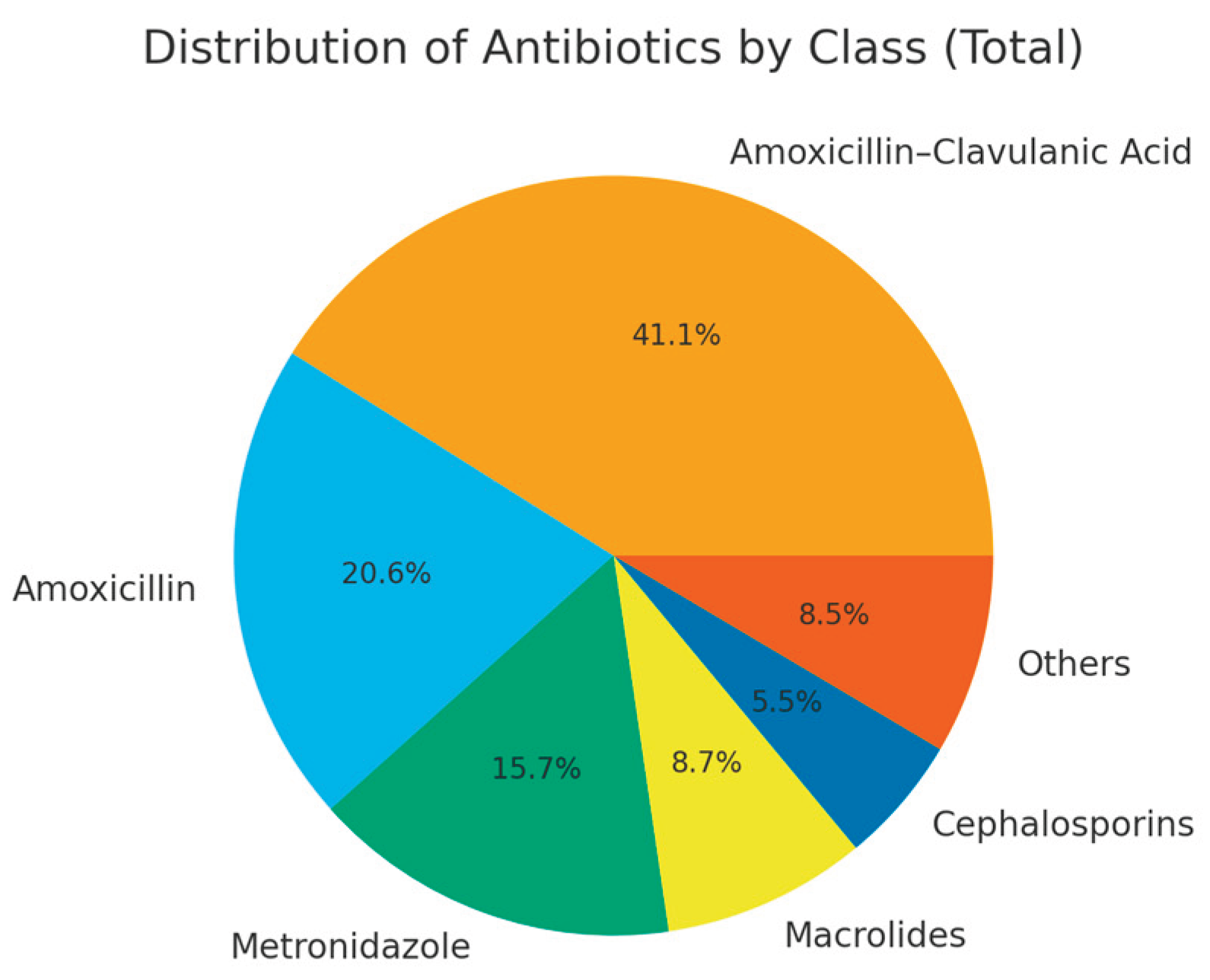

Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was the dominant prescription (>40%). Ferizaj prescribed more macrolides and cephalosporins. Explanation: The pattern indicates reliance on broad-spectrum agents, which raises concerns about antimicrobial resistance development.

Table 1.

Prevalence of antibiotic prescriptions by municipality.

Table 1.

Prevalence of antibiotic prescriptions by municipality.

| Municipality |

Total visits |

With antibiotic (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

| Pristina |

2210 |

630 |

28.5 |

| Ferizaj |

2110 |

698 |

34.2 |

| Total |

4320 |

1328 |

30.7 |

Ferizaj had significantly higher prevalence than Pristina (p < 0.01).

Interpretation: Penicillins account for majority of prescriptions, confirming data in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of antibiotics by class and municipality.

Table 2.

Distribution of antibiotics by class and municipality.

| Class |

Pristina n (%) |

Ferizaj n (%) |

Total n (%) |

| Amoxicillin–Clavulanic Acid |

270 (42.8) |

300 (43.0) |

570 (42.9) |

| Amoxicillin |

135 (21.5) |

150 (21.5) |

285 (21.5) |

| Metronidazole |

103 (16.3) |

115 (16.5) |

218 (16.4) |

| Macrolides |

39 (6.2) |

82 (11.7) |

121 (9.1) |

| Cephalosporins |

21 (3.4) |

55 (7.9) |

76 (5.7) |

| Others |

62 (9.8) |

56 (8.0) |

118 (8.9) |

Table 3.

Appropriateness of prescriptions.

Table 3.

Appropriateness of prescriptions.

| Category |

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Appropriate |

815 |

61.4 |

| Partially appropriate |

280 |

21.1 |

| Inappropriate |

233 |

17.5 |

| Total |

1328 |

100.0 |

Only 61.4% prescriptions were fully guideline-concordant.Explanation: This highlights a significant gap in adherence to international standards, supporting calls for stewardship interventions.

Table 4.

Prevalence by age group.

Table 4.

Prevalence by age group.

| Age group |

Total visits |

With antibiotic (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

| 1–3 years |

1900 |

667 |

35.1 |

| 4–7 years |

2420 |

661 |

27.3 |

| Total |

4320 |

1328 |

30.7 |

1–3 year olds had higher prescribing rate than 4–7 year olds (p < 0.01).Explanation: Younger children are more often prescribed antibiotics, possibly due to diagnostic uncertainty or parental pressure.

Table 5.

Prevalence by season.

Table 5.

Prevalence by season.

| Season |

Total visits |

With antibiotic (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

| Winter |

1200 |

467 |

38.9 |

| Spring |

1050 |

309 |

29.4 |

| Summer |

980 |

220 |

22.5 |

| Autumn |

1090 |

332 |

30.5 |

| Total |

4320 |

1328 |

30.7 |

Winter had peak prescribing; summer had lowest. Explanation: Seasonal spikes align with increased respiratory infections in colder months.

Table 6.

Logistic regression predictors.

Table 6.

Logistic regression predictors.

| Factor |

OR |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Age 1–3 (vs 4–7) |

1.42 |

1.21–1.66 |

<0.001 |

| Winter (vs Summer) |

1.85 |

1.55–2.20 |

<0.001 |

| Ferizaj (vs Pristina) |

1.34 |

1.12–1.59 |

0.001 |

| Male (vs Female) |

1.08 |

0.92–1.27 |

0.35 |

Age, season, and municipality were significant predictors. Explanation: Logistic regression confirms independent contribution of these factors to higher antibiotic prescribing.

Table 7.

Predictors of macrolide prescribing.

Table 7.

Predictors of macrolide prescribing.

| Factor |

OR |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Ferizaj vs Pristina |

1.55 |

1.22–1.97 |

<0.001 |

| Winter vs Summer |

1.6 |

1.25–2.05 |

<0.001 |

| Age 1–3 vs 4–7 |

1.1 |

0.89–1.35 |

0.40 |

Macrolides significantly more prescribed in Ferizaj and in winter. Explanation: Suggests local practice and seasonal infections influence choice of antibiotic class.

Table 8.

Prevalence by year.

Table 8.

Prevalence by year.

| Year |

Total visits |

With antibiotic (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

| 2022.0 |

1000.0 |

290.0 |

29.0 |

| 2023.0 |

1050.0 |

315.0 |

30.0 |

| 2024.0 |

1150.0 |

360.0 |

31.3 |

| 2025.0 |

1120.0 |

363.0 |

32.4 |

Yearly prevalence increased gradually.Explanation: Trend indicates progressive rise in prescribing, reflecting lack of intervention or stewardship.

Table 9.

Prevalence by municipality and year.

Table 9.

Prevalence by municipality and year.

| Year |

Pristina (%) |

Ferizaj (%) |

| 2022.0 |

27.0 |

31.2 |

| 2023.0 |

28.5 |

32.0 |

| 2024.0 |

29.0 |

34.0 |

| 2025.0 |

29.6 |

35.1 |

Ferizaj consistently had higher prevalence across all years.Explanation: Consistent inter-municipality differences suggest systemic prescribing behavior differences rather than random variation.

3. Discussion

The findings of this study provide one of the first comprehensive insights into pediatric antibiotic prescribing practices in primary health care settings in Kosovo. The overall prescribing rate of prescribing (30.7%) was comparable to rates reported in some Southeast European countries but remains higher than in many Western European settings where stewardship interventions have been implemented [

1,

2]. Importantly, 38.6% of prescriptions were either partially appropriate or inappropriate, underscoring substantial room for improvement.

Antibiotic resistance implications: The frequent use of broad-spectrum agents such as amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, macrolides, and cephalosporins is concerning. Surveillance data from neighboring Balkan countries indicate resistance rates exceeding 30% for

Streptococcus pneumoniae against macrolides and increasing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins among

Enterobacteriaceae [

3,

4,

5]. Discussion — Regional AMR context (quantitative) and selective-pressure metrics

Regional AMR context and selective-pressure metrics. Our findings of frequent broad-spectrum use (amoxicillin–clavulanate, macrolides, cephalosporins) must be interpreted within the quantitative AMR landscape of the region. Neighboring surveillance reports consistently show macrolide non-susceptibility in Streptococcus pneumoniae exceeding 20% in parts of the European region, and third-generation cephalosporin resistance in Enterobacterales surpassing 15% in several settings. While Kosovo currently lacks pediatric-specific national AMR surveillance, these proxy estimates underscore the urgency of pediatric stewardship and integration with European surveillance frameworks. To monitor ecological selection pressure over time in primary care, we propose routine tracking of: (i) broad-to-narrow spectrum ratio (primary care antibiotic consumption), (ii) DDD per 1000 inhabitants per day, and (iii) AWaRe ‘Access’ proportion. Embedding these indicators in quarterly audits would allow benchmarking between municipalities and evaluation of stewardship impact (e.g., reduction in broad:narrow ratio and increase in ‘Access’ share).

Discussion — Pediatric antibiotic stewardship algorithm for PHC (practical box)

Practical pediatric stewardship algorithm for primary care (outpatient).

- 1.

First-line for common URTI/otitis media (non-severe, no risk factors): amoxicillin per guideline dose and duration.

- 2.

Macrolide use: only for documented/suspected atypical pathogens or confirmed penicillin allergy; avoid for routine viral URTI.

- 3.

Cephalosporins: reserve for justified spectrum expansion (e.g., treatment failure with first-line, specific clinical risk), with clear stop-review at 48–72 h.

- 4.

Metronidazole: restrict to GI/anaerobic indications; not for routine respiratory infections.

- 5.

UTI pathway: urinalysis ± urine culture prior to broadening; tailor therapy to results where available.

- 6.

Delayed prescription + parental counseling: use when bacterial infection is uncertain; provide safety-net advice and review triggers.

- 7.

Dose/duration standardization: follow WHO EMLc/ESPID/NICE tables; avoid dual coverage without indication.

- 8.

Review & de-escalate at 48–72 h; stop if bacterial infection becomes unlikely.

- 9.

Record key indicators in EHR (indication, agent, dose, duration, review date) to enable audit & feedback.

(This algorithm operationalizes the study’s findings for everyday PHC decision-making and aligns with the need to improve appropriateness.

Discussion — Kosovo context: AMS capacity & OTC pressures

Kosovo context: AMS capacity and OTC pressures. At present, Kosovo lacks national pediatric primary-care prescribing guidelines, and structured AMS activities in PHC are limited. In this context, municipal-level differences may reflect variability in diagnostic practices, clinician experience, and parental expectations. In parallel, over-the-counter access and self-medication pressures—despite prescription-only regulation—likely contribute to demand for antibiotics in viral illnesses. We therefore propose: (i) adapting WHO/ESPID/NICE guidance into national pediatric PHC protocols; (ii) establishing quarterly audit-and-feedback cycles using broad:narrow ratio, DDD/1000, and AWaRe ‘Access’ proportion; (iii) integrating clinical pharmacists into PHC teams for dose/duration review; (iv) expanding POC testing and selective culture use (e.g., UTI) to reduce empirical broad-spectrum starts; and (v) public winter campaigns for parental counseling on appropriate antibiotic use.

Although systematic pediatric resistance data are lacking in Kosovo, our findings of frequent broad-spectrum use strongly suggest that local resistance patterns may be driven by these prescribing habits.

Age and diagnostic uncertainty: Children aged 1–3 years were significantly more likely to receive antibiotics compared to those aged 4–7 years (35.1% vs. 27.3%). This is consistent with international evidence showing that diagnostic uncertainty, parental pressure, and higher incidence of respiratory tract infections in toddlers contribute to more frequent empirical prescribing [

6,

7]. However, no robust scientific evidence supports a direct association between age alone and bacterial infection rates, which highlights the need for more precise diagnostic approaches in younger children.

Seasonal and regional variations: Antibiotic prescribing peaked during winter (38.9%), corresponding with seasonal epidemics of respiratory tract infections. Ferizaj showed consistently higher prescribing prevalence compared to Pristina across all years (34.2% vs. 28.5%). These differences may reflect variations in diagnostic practices, local physician experience, socioeconomic differences, or parental expectations. Further qualitative research is needed to understand physician decision-making in these contexts.

Rise of macrolides and cephalosporins: A gradual increase in the prescribing of macrolides and cephalosporins from 2022 to 2025 was observed. This may be related to the perceived broad-spectrum efficacy of these classes, availability in the local pharmaceutical market, or substitution when resistance to penicillins is suspected. However, the shift toward broader-spectrum antibiotics without microbiological confirmation accelerates the risk of resistance development.

Role of health system actors: The absence of national pediatric antibiotic guidelines in Kosovo leaves clinicians without standardized protocols. In contrast, many European countries implement national guidance and monitoring systems that improve appropriateness of prescribing [

8,

9]. Clinical pharmacists and infectious disease specialists can play a key role in supporting pediatricians with case-based consultations, particularly in ambiguous cases. Moreover, strengthening the role of microbiology laboratories for culture and sensitivity testing would allow more evidence-based decision-making rather than empirical prescribing.

Limitations — Microbiology/CDI and future molecular work

Limitations and future work (microbiology and CDI). Our PHC EHR dataset did not include linked microbiology or Clostridioides difficile outcomes, precluding resistance-specific analyses (e.g., amoxicillin vs amoxicillin–clavulanate resistance differentials) and CDI estimation. Future prospective work should incorporate isolate-level testing (culture ± molecular), targeting common pediatric respiratory and urinary pathogens, and explore resistance determinants (e.g., erm(B)/mef(A) for macrolides, ESBL genes in Enterobacterales, pbp variants for penicillin nonsusceptibility). Embedding microbiology feedback loops into PHC would enable targeted therapy and timely de-escalation, strengthening the link between prescribing quality and resistance outcomes at municipal level.

Implications for practice and policy: Our results highlight an urgent need for implementing antibiotic stewardship interventions in primary care in Kosovo. This includes the development of national pediatric prescribing guidelines, routine training of primary care physicians, and integration of pharmacists into the prescribing process. Furthermore, public health campaigns should address parental expectations for antibiotics, particularly during winter months. Specifically, we recommend: (1) development of national pediatric prescribing guidelines, (2) integration of clinical pharmacists into PHC teams, (3) strengthening microbiology laboratories for diagnostic support, and (4) targeted public health campaigns to reduce parental demand for antibiotics during winter.

Comparison of our findings with international literature

| Key finding from our study |

Similar findings reported in |

Differences noted in |

Reference(s) |

| Higher prevalence in Ferizaj (34.2%) |

Regional variation in Italy, Spain |

– |

[10,19] |

| Dominance of penicillins (>40% prescriptions) |

Slovenia, Croatia |

– |

[12,13] |

| Higher macrolide/cephalosporin use in Ferizaj |

Poland, Hungary |

– |

[14,22] |

| Greater antibiotic use in children 1–3 years |

USA, Finland |

– |

[15,16,18] |

| Seasonal peak in winter (38.9%) |

Sweden, USA |

– |

[17,18] |

| Low guideline adherence (61.4%) |

Lower than EU average (>75%) |

– |

[20] |

This comparative table summarizes how our findings align with or diverge from international studies. The higher prescribing rate in Ferizaj, the dominance of penicillins, and the seasonal peak in winter mirror trends observed across Europe and the United States. However, the relatively high use of macrolides and cephalosporins in Ferizaj, as well as the low adherence to guidelines (61.4%), highlight specific challenges in Kosovo. These findings underline the urgent need for targeted antibiotic stewardship interventions to reduce inappropriate prescribing and mitigate the risk of antimicrobial resistance.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a high prescribing rate of pediatric antibiotic prescribing in primary care settings in Kosovo, with substantial rates of inappropriate or partially appropriate use. Significant variations were observed by age, season, and municipality, with a concerning increase in the use of broad-spectrum agents such as macrolides and cephalosporins. These findings emphasize the urgent need for national antibiotic stewardship programs, pediatric prescribing guidelines, and enhanced diagnostic support to promote rational antibiotic use. Addressing these gaps will help reduce unnecessary exposure in children, mitigate the risk of antimicrobial resistance, and improve quality of pediatric care in Kosovo.

4. Methodology

This Study design and setting:This was a retrospective, observational, and quantitative study conducted in the Primary Health Care Centers of Prishtina and Ferizaj, Kosovo. The study covered the period from January 2022 to January 2025 and focused on antibiotic prescribing among pediatric patients aged 1–7 years.

Appropriateness was judged against WHO EMLc, ESPID and NICE pediatric guidance (indication, choice, dose, duration). Partially appropriate = correct indication but suboptimal choice/dose/duration; inappropriate = no guideline-concordant indication.

Study population and inclusion criteria:All medical records of children aged 1–7 years who visited the selected primary care centers during the study period were screened. Records were included if they contained complete diagnostic and prescription information. Records with missing data or patients outside the 1–7 age range were excluded.

Data collection:Data were extracted from the official national electronic health record system. The variables collected included: age, gender, municipality, season of visit, diagnosis, prescribed antibiotic class and agent, and whether the prescription adhered to international guidelines. A standardized data extraction form was adapted from the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) and the WHO Point Prevalence Survey framework to ensure consistency and accuracy.

Assessment of prescription appropriateness:The appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions was assessed independently by two senior physicians (pediatrician and infectious disease specialist) and a clinical pharmacist, using internationally recognized guidelines. Specifically, the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children (2021), the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID) guidelines, and the NICE guidelines for pediatric infections were used as references [

1,

2,

3]. Prescriptions were classified as:Additional details: Appropriateness was evaluated according to WHO (2021), ESPID, and NICE guidelines. Criteria included indication, drug choice, dose, and duration. Two physicians and one clinical pharmacist independently reviewed prescriptions with strong agreement (κ = 0.82). Bias was minimized using standardized EHR data extraction and blinded assessment.

Appropriate: fully consistent with recommended indications, choice of drug, dose, and duration.

Partially appropriate: consistent with indication but suboptimal in choice of drug, dose, or duration.

Inappropriate: not consistent with any guideline recommendations.

Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. Inter-rater reliability was assessed and showed strong agreement (κ = 0.82).

Statistical analysis:Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means ± SD) were used to summarize data. Differences between municipalities were evaluated using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Seasonal and yearly variations were analyzed using the Cochran–Armitage trend test. Independent predictors of antibiotic prescribing were identified using multivariable logistic regression, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations:The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of UBT College and by the respective local health authorities of Prishtina and Ferizaj. Patient data were fully anonymized prior to analysis. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).Clarification: Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at UBT College. The committee meeting was held during the COVID-19 pandemic period via the Google Meet platform, in accordance with the public health measures in place at that time. Due to the pandemic circumstances, no physical written document was issued; however, the approval was granted during the online meeting and constituted part of the committee’s collective decision.In addition, authorization from the municipal health authorities of Prishtina and Ferizaj was obtained on January 10, 2022.Informed consent was waived, as the data used were fully anonymized and retrospectively extracted from electronic health records (EHRs).

5. Conclusion

This study, conducted in two major municipalities of Kosovo between January 2022 and January 2025, revealed that the prescribing rate of antibiotic prescribing among children aged 1–7 years remains high (30.7%), with significant differences between Pristina and Ferizaj. Ferizaj showed higher rates and a more frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, while penicillins predominated in Pristina. The main factors associated with prescribing were younger age (1–3 years), winter season, and local prescribing practices.

A critical finding was that only 61.4% of prescriptions adhered to clinical guidelines, indicating a considerable level of overuse and inappropriate prescribing. These results emphasize the urgent need for structured antibiotic stewardship interventions in primary care in Kosovo, including:

- -

standardization of prescribing protocols,

- -

continuous medical education for physicians,

- -

parental awareness campaigns, and

- -

systematic monitoring of pediatric prescriptions.

In line with international literature, our results mirror trends reported across Europe and the United States, while also highlighting specific challenges for Kosovo, particularly in the use of macrolides and cephalosporins. The implementation of evidence-based health policies and the strengthening of control programs are essential steps to prevent the escalation of antimicrobial resistance and to ensure safe and effective treatment for children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Writing—Review and Editing: F.A., A.H.A., L.M., M.H., and F.AB. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and approved by the Ethics Committee of UBT College as well as local health authorities in Prishtina and Ferizaj.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Primary Health Care Centers in Prishtina and Ferizaj for providing access to the data, as well as colleagues who contributed to data collection and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. (2020). Antimicrobial resistance. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Ten threats to global health in 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Venekamp, R.P.; Sanders, S.L.; Glasziou, P.P.; Del Mar, C.B.; Rovers, M.M. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, 2015, CD000219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, N.; Morone, N.E.; Bost, J.E.; Farrell, M.H. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: A meta-analysis. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2008, 27, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, A.L.; Jackson, M.A.; Hicks, L.A. Principles of judicious antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havers, F.P.; Hicks, L.A.; Chung, J.R.; et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections during influenza seasons. JAMA Network Open 2018, 1, e180243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasniqi, S.; Versporten, A.; Jakupi, A.; et al. Antibiotic utilization in adult and children’s patients in Kosovo hospitals. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2019, 26, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, L.; Islami, H.; Šutej, I. The pattern in the utilization of the first-choice antibiotic among dentists in the Republic of Kosovo: A prospective study. European Journal of General Dentistry 2023, 12, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaj, I.; Fejza, H.; Alidema, F.; Mustafa, L. Prevalence of antibiotic use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: An observational study in secondary healthcare hospitals in Kosovo. IIUM Medical Journal of Malaysia 2024, 23, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). (2022). Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA: Annual epidemiological report for 2021. Stockholm: ECDC.

- O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. London: HM Government & Wellcome Trust 2016.

- Vlahović-Palčevski, V.; Palčevski, G.; Bergman, U. Antibiotic utilization at the university hospital in Croatia. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2000, 9, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizman, M. The use and resistance to antibiotics in the community. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2001, 18, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, H.; Ferech, M.; Vander Stichele, R.; Elseviers, M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: A cross-national database study. The Lancet 2005, 365, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione-Smith, R.; McGlynn, E.A.; Elliott, M.N.; et al. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1999, 153, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Virta, L.J.; et al. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundvall, P.D.; Stuart, B.; Davis, M.; et al. Antibiotic use in primary care and associations with sore throat consultations: A time-series analysis of electronic records in Sweden. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A.L.; Shapiro, D.J.; Pavia, A.T.; Shah, S.S. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchini, S.; Argentiero, A.; Camilloni, B.; Silvestri, E.; Esposito, S. Antibiotic resistance in pediatric infections: Global emerging threats, predicting the near future. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2020, 46, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, N.; Coenen, S.; Versporten, A.; et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2011, 66 (Suppl. S6), vi3–vi12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palčevski, V.V.; Gantumur, M.; Dudas, A.; et al. Attitudes to antibiotic prescribing and resistance among physicians in Croatia. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2007, 60, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kósa, E.; Nagy, T.; Farkas, Á.; Kocsis, B.; Szabó, A. Antibiotic consumption in Hungarian children. European Journal of Pediatrics 2019, 178, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).