1. Introduction

Tempera paintings on ancient wooden icons suffer a series of evolutionary deteriorations and degradations over time, due to improper storage and use conditions. This can be physical state of the structural-functional elements, degradation of the chemical nature of the art components, and mold-induced biodegradation, causing aesthetic and structural [

1,

2,

3]. Wood and canvas as a base for easel painting are prepared by craftsmen according to traditional canons. This is a mixture of inorganic materials (pigments, gypsum, chalk) in organic binders (glues, oils, resins, etc.). Glues can be of animal (gelatin, albumin, casein and wax) and plant origin (starch, resins, gums and gluten) [

4,

5]. Such components are a rich source of nutrients for the development of harmful microorganisms and the destruction of the art object in case of violation of the temperature and humidity conditions. A separate material subject to biodegradation may be the base itself (wood, canvas, paper, parchment) as well as art materials (oil, tempera, gouache, watercolor, ink, pastel, charcoal, etc.) which serve as a source of nutrition for microorganisms [

6,

7].

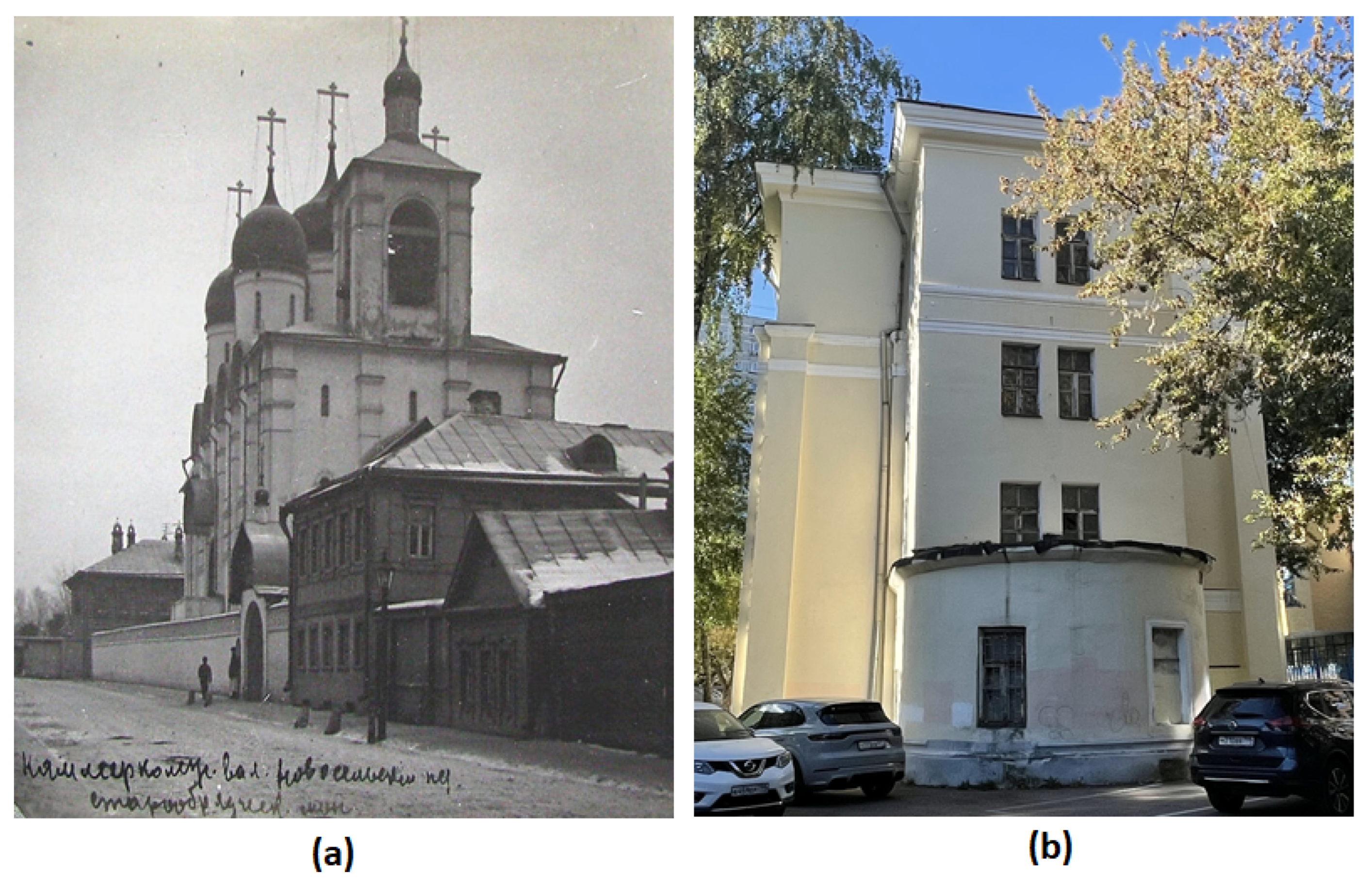

The object of the study is the 16

th century icon “Descent into Hell”. This icon was received by the State Tretyakov Gallery (STG) from the Cathedral Old Believer Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos in Moscow (

Figure 1) in 1935.

This cathedral was one of the first to be built in Moscow after Tsar Nicholas II issued a Decree strengthening the principles of religious tolerance in 1905, and it was intended to become a symbol of the revival of the Old Believers in Rus’. The five-domed cathedral was striking in the grandeur and monumentality of its architectural forms. The bell tower had twelve bells, the largest of which weighed approximately 6 tons. The building underwent several changes over the time: the First World War, the October Revolution in 1917, and the final closure and repressions of the church’s rectors during Stalin’s time in 1930.

The icon had a darkened top layer of drying oil, numerous crackles and chips on the paint layer. In the left part of the icon, there was a large area with graying of the pigment layer and the formation of whitish inclusions of unknown genesis. The STG Restoration Council decided to conduct a molecular diagnosis of the surface and wooden ends of the icon to confirm or refute the biological nature of the damaged areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Object of the Study

The 16

th century icon of vertical format—78×64×3 cm. The icon shield consists of two linden boards, fastened with transverse dowels. The technique is the egg tempera and gilding (

Figure 2).

2.2. Isolation and Growth of Fungi Strains

In March of 2024 ten microbiological samples in problem and control areas were collected from the front side and from the wooden ends of the icon (

Figure 2). Further manipulations with samples were carried out as described [

8]. Then aliquots were inoculated onto 3 types of slanted agar media: i) potato dextrose agar (PDA, g/l: potato extract (200 г) – 4, glucose – 20, agar – 20, pH 5.6); ii) lysogeny broth (LBA, g/l: bactotriptone – 10, bacterial yeast extract – 5, NaCl – 10, agar – 20) and iii) yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD, g/l: bacterial yeast extract – 10, peptone – 20, glucose – 20, agar – 20).

2.3. Phenotypic Characterization of Fungi Strains

2.3.1. Light and Fluorescence Microscopy

The morphology of conidiospores and hyphae in PDA medium was studied under native conditions using the Carl Zeiss Jena microscope (Germany) at magnification ×1000. The detection of the fluorescent signal of the stain Calcofluor White (CFW, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was achieved through Celena X microscope (Logos Biosystems, Korea), equipped with a specific filter set comprising an excitation filter 375/28, an emission filter 460/50, a lens plan apo fluor oil coverslip corrected 100×, with a numerical aperture of 1.25 and a working distance of 0.19.

2.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Microstructural characteristics of cultivated filamentous fungi and micro-scrapings from the icon’s surface paint layer in areas suspected to biodegradation and in conditionally clean control zones were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Tescan Amber FIB-SEM ion-beam scanning electron microscope (Tescan Group, Czech Republic). For this purpose, representative samples were choosen, which were further mounted on an aluminum objective table using conductive carbon tape. Then the samples were placed in the vacuum chamber of the microscope and air was evacuated from it until the working pressure reached about 1.0-1.5·10−5 mbar. An Everhart-Thornley secondary electron detector with a focal length of about 5 mm was used to examine materials surface. To minimize the impact of the electron beam on the samples structure, their surface was scanned at a sufficiently low accelerating voltage (1 kV). Due to the relatively low electrical conductivity of the samples under investigation, the magnification, as a rule, was limited to the range of 250-15000 times. To intensify charge flow, a carbon film was deposited on the analyzed material surface with a compact coat-ing Desk Carbon Coater system (NanoStructured Coatings Co., Iran).

2.4. Genomic DNA Extraction

The genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from lyophilized fungal pure cultures by phenol-chloroform method. Lyophilized samples were resuspended in 200 μL of TES buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.5) with glass beads (D = 500 μm) and incubated at 65 °C for 1 h. After cooling, 200 μL of phenol (saturated with 0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) was added. Afterwards the upper layer of the sample containing gDNA was washed with an equal volume of the chloroform/isoamyl alcohol mixture (24 : 1) and then precipitated by 96% chilled ethyl alcohol after 3M potassium acetate (pH 5.2) addition (1/10 of the total volume). All procedures were conducted on ice with periodic shaking (Vortex mixer, Glassco, India). The target gDNA precipitate was washed with chilled 70% ethyl alcohol and dried out.

2.5. PCR Amplification

PCR amplification was performed using primer pairs for fungi isolates STG-160 (PV645139.1) and STG-161 (PV636606.1) to hypervariable regions of rDNA i) Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) – ITS1 (5’-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3’) and ITS4 (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’) [

9]; ii) for locus Calmodulin – CMD5 (5’-CCGAGTACAAGGARGCCTTC-3’) and CMD6 (5’-CCGATRGAGGTCATRACGTGG-3’) [

10] and iii) for locus Actin – ACT-512 (5’-ATGTGCAAGGCCGGTTTCGC-3’) and ACT-783 (5’-TACGAGTCCTTCTGGCCCAT-3’) [

11].

2.6. Sequencing

The subsequent extraction of amplified fragments PCR was conducted utilizing the CleanupMini kit (Evrogen, Russia), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Subsequently, the PCR-fragments were subjected to sequencing using the Sanger method, employing the Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., USA) on ABI PRISM 3730 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary analysis of the obtained sequencing spectrograms was performed using Chromas software, version 2.6.6 (

https://technelysium.com.au/wp/chromas/). The nucleotide sequence was subjected to further analysis using Vector NTI v.6.0 [38,39]; the sequence fragment containing a representative reading zone was compared in BLAST (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/- Blast.cgi) against available sequences in databases. Following a thorough comparison of the results, it was determined that the sequence under investigation is likely to be part of the rDNA of a specific organism.

2.7. Mock Layers Design and Inoculation

Mock layers were developed with modern analogues of art materials used in tempera paintings in 16

th century, according to literature sources [

12]; The structure of art layers was the same as earlier described: linden board (support) was covered with canvas and glued with ground layer (water solution of chalk and sturgeon glue, 70 g/l; afterwards different art materials was covered above [

1]. Fungi isolates STG-160 and STG-161 were inoculated onto three paint layers – two of which were tempera pigments in egg yolk (ochre and cobalt green) and the last one – watercolor black (madder, burnt azure, soot) with gum arabic as plasticizer. Each mock layer was approximately of 2 × 2 cm. Inoculation of mock layers was conducted as previously described [

13]. Before inoculation fragmented pieces were placed into sterile Petri dishes and saturated with 0.3 ml H2O per 1 cm3 at 25 °C for 48 h, pieces with mock layers were placed on sterile hydrophobic spacers so that the lid of Petri dish did not touch the surface of the fragment. Then inoculated by fungi suspension (resuspended in 0.9% NaCl) to optic density OD

600 = 0.35.

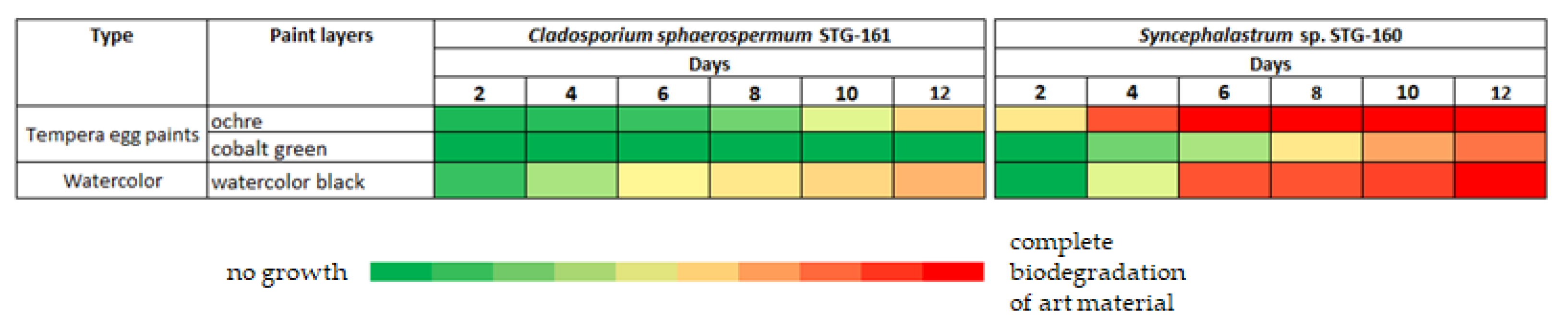

Fungal growth on mock layers was measured on 2

nd, 4

th, 6

th, 8

th, 10

th and 12

th day. Dynamics of biodegradation of mock layers was estimated as relative average growth area (AGA) that was determined by the formula:

Wherein, Stav indicates the average area of the colony STG-160 or STG-161 (mm2) ; Sc indicates the surface area of the whole mock layer (mm2). The data recorded were measured in triplicate and repeated at least twice. The results are presented in the form of thermogram.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Identification and Morphological Characterization of Fungi Strains STG-160 and STG-161

Samples cultivation of isolates nos. 1, 2, 7 and 10 did not yield any growth of microorganisms. Isolates nos. 3, 4, 8 and 9 have detected bacterial growth. Isolate no. 5 has detected bacterial growth and fungal growth of order

Capnodiales (class

Dotideomycetes) (

Figure 2). Isolate no. 6 has detected just fungal growth of order

Mucorales (class

Mucoromycetes) (

Figure 2). Phylogenetic analysis of ITS region and actin locus of fungal isolate no. 5 and no. 6 has shown 100% of identity with

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 (GenBank accession numbers PV636606.1 and PV645139.1, respectively).

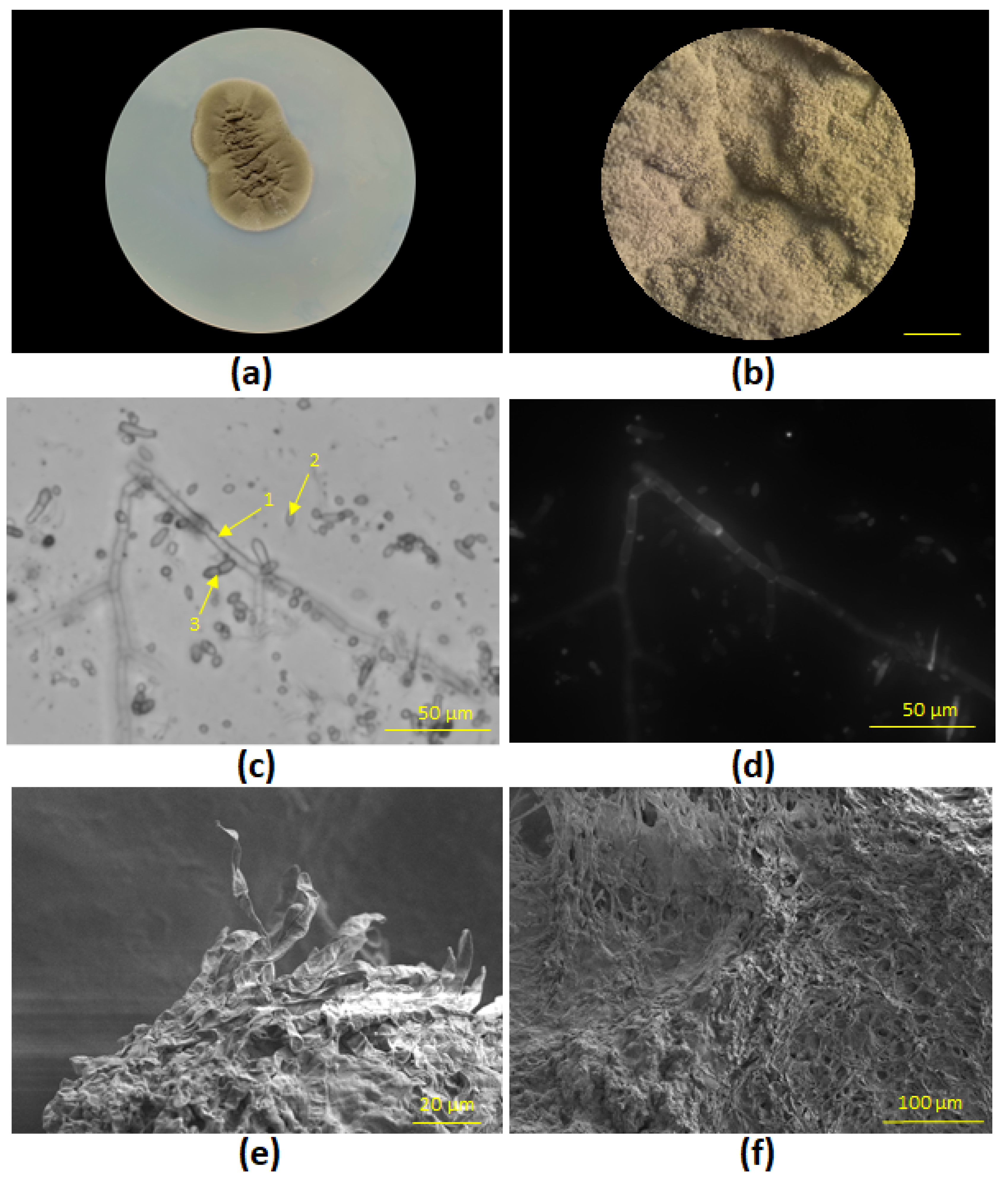

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 was found to be of a dark olive green color with dense consistency when cultivated on PDA medium (

Figure 3a,b) Also, light and fluorescence microscopy revealed classical morphological forms for

Cladosporium beside conidiophores, such as ovate conidia and ramo-conidia (

Figure 3c,d), as it was shown previously in [

14]. SEM shows a dense biofilm of

Cladosporium sphaerospermum mycelium (

Figure 3e,f).

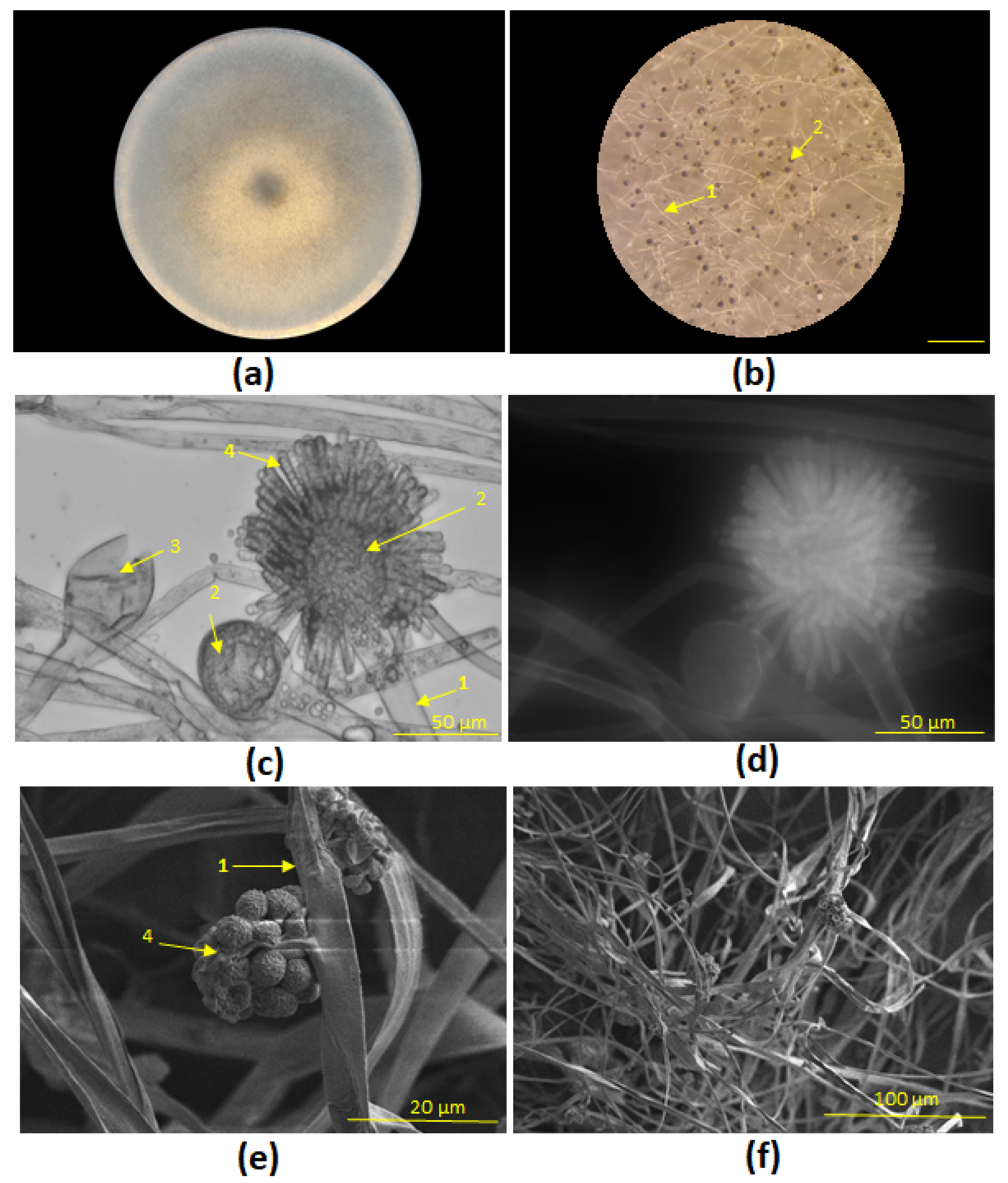

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160

incubated for seven days at 26 °C on PDA medium has shown the circular colony (

Figure 4a) with grey and at the same time transparent filamentous with distinct spherical heads (sporangia) (

Figure 4b). The dark grey area results with increasing age of the colony and the associated production of spore carriers, the same was noticed in [

15,

16]. Transmitted-light and fluorescent microscopy clearly show different morphological forms

—sporangia carriers, vesicles that are covered by merosporangium

with spherical mero-spores (

Figure 4c,d). SEM shows

Syncephalastrum sp. mycelium with conidiophores and conidia head with young merosporangia (

Figure 4e,f).

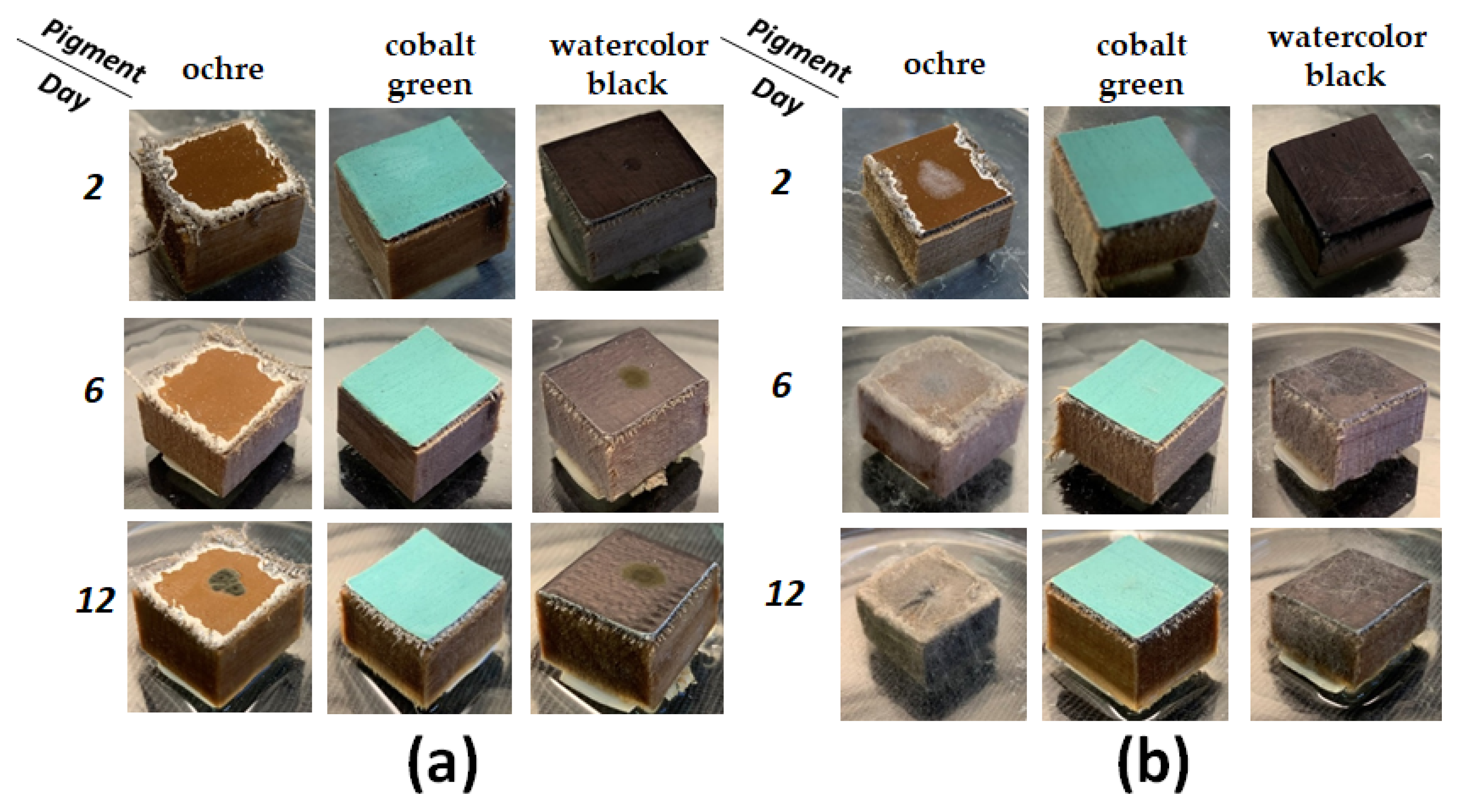

3.2. Mock Layers Biodegradation

To determine the biodegradability of the identified fungus isolated in points nos. 5 and 6 it was suggested to inoculate

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 onto paint materials of mock layers. Tempera pigments in egg yolk (ochre and cobalt green) and the watercolor black (madder, burnt azure, soot) with gum arabic as plasticizer were selected as the most frequently used materials in restoration practice (

Figure 5).

The ochre pigment in egg yolk emulsion is maximum bioavailable for

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 since it shows 30% of biodegradation of the layer on 2

nd day, 75% on 4

th day and on 6

th day the layer was completely covered in mold (

Figure 5b and

Figure 6).

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 is not as active, but nevertheless confidently digests ochre pigment and if extrapolated to a longer period, in 20 days such mock layer of a 2 × 2 cm size will be absorbed almost completely. Watercolor black pigment is digested at a slightly slower rate than ochre. Cobalt green pigment significantly delays development of

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 and there is no growth on it at all of

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161.

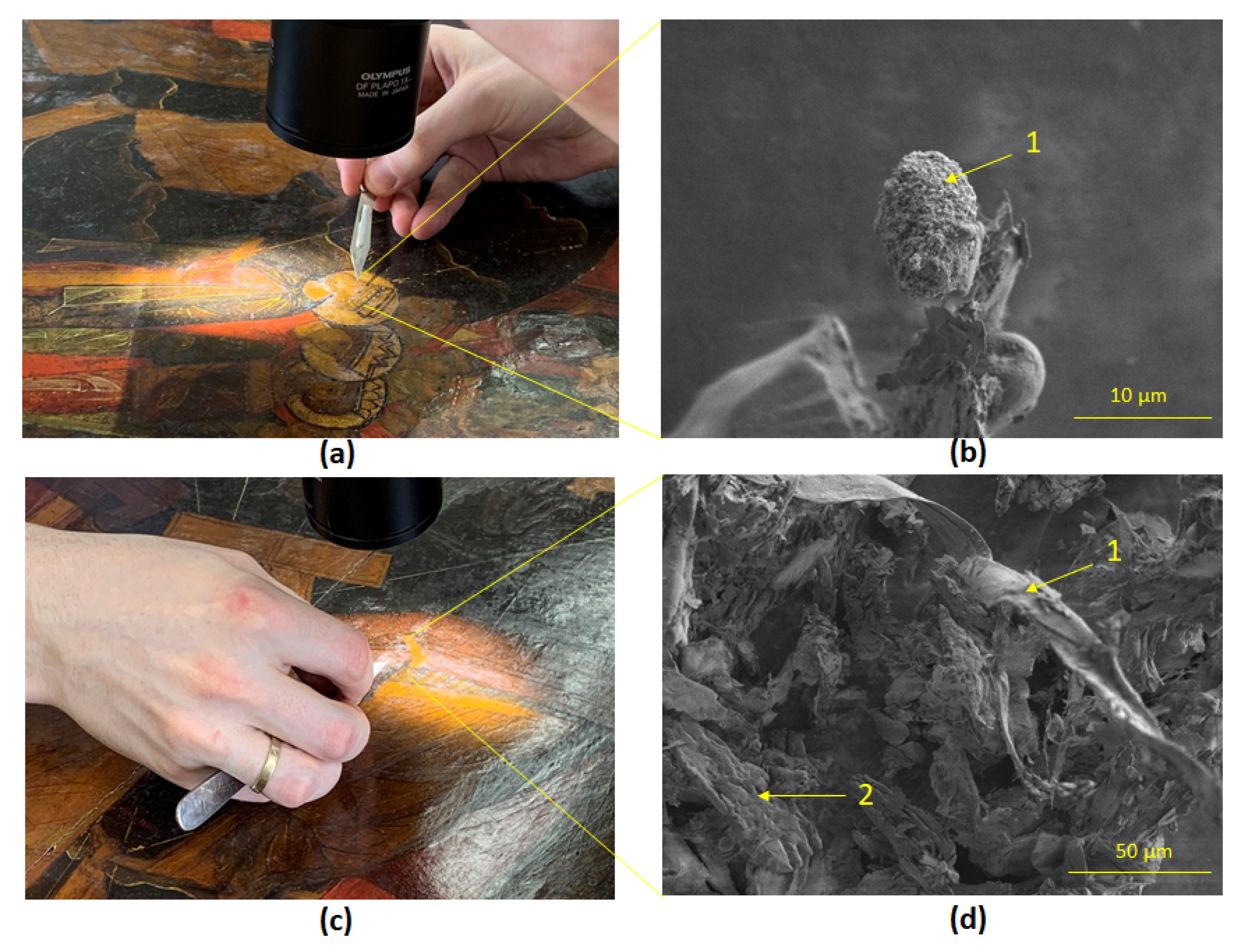

SEM of micro-scrapings of the area of the Holy Fathers faces and their chitons images has shown a single cone-shaped spore of the mold fungus

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 (

Figure 7b) and rare mycelial hyphae of

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 (

Figure 7d). Micro-scrapings in other areas of pigment layer of the icon did not reveal any traces of biological presence of mycelial mold fungi, just crystal structures of fatty acids and possibly drops of linseed oil remaining after restoration (

Figure S1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Detection of Fungi-Destructors of Tempera Painting

Detection of the microbiological component in the area of graying of the paint materials in the lower left corner of the icon determined only a small number of bacteria. Spectral diagnostics of micro-scrapings from the icon’s paint layer in these same zones showed microstructures of the paint itself, possibly inclusions of fat droplets related to restoration materials (

Figure S1). It can be assumed that the whitish coating corresponds to the aging of linseed oil on the surface, which is used for the protective coating of the icon to isolate the paint layer from the effects of air [

17]. On the one hand, the increased ability of linseed oil to oxidize and polymerize is important for the varnish coating, but this can lead to the appearance of such unaesthetic visual processes as graying of the material, which is caused by the oxidation of the high content of unsaturated fatty acids. [

18].

The morphology of the single rare filamentous mycelium (

Figure 7d) and cone-shaped spore (

Figure 7b) on the micro-scrapings in potentially clean zones correlates with the images of the cultivated cultures

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 (

Figure 3e) and

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 (

Figure 4e), respectively, which allows to identify these fungi as potentially dangerous. In case of violation of the temperature and humidity conditions, either at the exhibition halls or in the restoration workshop, it is possible that these mold fungi will spread over a large area of the icon, which will entail, as it is known, cracking and crumbling of the paint layer, perforation of the primer, as mold usually behaves [

19,

20].

Common representatives of fungi-destructors of tempera painting are those of the genera

Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, and

Penicillium [

16,

17,

18]. Therefore, the presence of

Cladosporium did not surprise us. But usually soil-born filamentous fungus

Syncephalastrum sp. [

21] attracts the most attention. Usually

Syncephalastrum species, belonging to the class

Zygomycetes, present as colonizers and rarely cause human infection [

21,

22]. When clinically significant, they are usually implicated in cutaneous infections and onychomycosis [

23]. However, these fungus genera may cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients [

24], which could prove potentially dangerous for restoration art workers if the fungi multiply rapidly.

4.2. Dynamics of Paint Layer Biodegradation

Cobalt green showed the lowest degree of biodegradation compared to ochre and watercolor black (

Figure 4, 5).

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 was not able to utilize it at all.

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 appeared foci of mycelial germination only on 6

th day, but mycelium morphologically was lifeless, as if dried out, its color was light yellow, in contrast to the intensively branched gray mycelium cultivated on the PDA medium. The low growth rate of these fungi is explained by the chemical composition of the pigment. Cobalt green is said to be similar to cobalt blue (CoO

·Al

2O

3 ) except that ZnO partially or wholly replaces the aluminium hydroxide [

25]. Moreover, it is noticed that the composition of cobalt green varied considerably with 71.5–88% zinc oxide and 11.5–19% cobalt oxide with fluctuating amounts of phosphoric acid, soda, iron oxide, etc., depending on the manufacturing process followed [

25]. In this regard, we attribute the lack of growth or slow growth of mycelium to the general toxicity of heavy metal ions in the paint [

26,

27].

Mock layer with the watercolour black, which is a mix of water-soluble colored pigments—madder, burnt azure, and soot in gum arabic as plasticizer—showed not too intensive for

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 utilization (

Figure 5a,

Figure 6), but quite preferable for

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 (

Figure 5b,

Figure 6). The gum arabic is added to watercolour for better capacity to stick to the surface [

17]. It is possible that identified fungi contains the appropriate enzymes that hydrolyze the polysaccharides that make up gum arabic.

The ochre pigment is the leader of degradation among tested pigments for

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160, but

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 dispose this pigment a bit slower. Ochres are variably coloured rocks and soils primarily composed of ferric oxides and hydroxides [

25], which are a rather stable and poorly soluble compound. But fungi have adapted to utilize vital iron. A well-known strategy for effective iron uptake is production and subsequent uptake of siderophores, which are small molecules that act as high-affinity Fe chelators [

28]. Another important Fe uptake mechanism involves a group of specialized membrane proteins. In this high affinity system, the metal is reduced from Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ (in order to increase Fe solubility) by membrane-bound ferrireductases, and then it is rapidly internalized by the concerted action of a ferroxidase and a permease that form a plasma membrane protein complex [

29].

Ability to absorb heavy metal ions depends on the set of genes of each individual organism. It was previously shown that the fungus

Rhizophagus irregularis, used as a soil inoculant in agriculture, has 30 open reading frames in its genome, which potentially encode heavy metal (Cu, Fe and Zn) transporters [

30]. Current experiment showed that in terms of adaptability to survival, the fungus

Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 has more advantages compared to

Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161, in particular in terms of ochre and even cobalt green utilization (

Figure 6). This illustrates the danger of the spread of even single spores of identified fungi if the temperature and humidity conditions change.

5. Conclusions

Timely molecular diagnostics of the microbiological state of the art object—detection of mold spores or mycelial threads on seemingly clean surfaces, as well as understanding which types of pigments are most susceptible to biodegradation—allows the effective antimicrobial treatment and hereby preservation of cultural heritage. Therefore, the next stage of the work requires targeted selection of antiseptics against the fungi found on the icon for subsequent effective treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

The work presented here was carried out in collaboration between all authors. D.A., A.Z. planned and designed the research. D.A., A.E. performed experiments and analyzed data. N.S. provided SEM. E.T. provided cultural and historical materials. M.S., A.Z. provided critical infrastructure and technical support. D.A. wrote the manuscript. Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 25-28-00231” and “The APC was funded by 25-28-00231”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In this study we used GenBank accession numbers Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 (PV636606.1) and Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 (PV645139.1).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the artist-restorer of the 1st category of the scientific restoration department of ancient Russian painting of the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Olga Vorobyova for design and manufacturing mock layers. The authors also thank Mr. Evgeny Avdanin for his assistance in design of the Graphical Abstract. The authors have no competing interests to declare. Sequencing was performed by Core Facility “Bioengineering” (Research Center of Biotechnology, RAS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhgun, A.; Avdanina, D.; Shumikhin, K.; Simonenko, N.; Lyubavskaya, E.; Volkov, I.; Ivanov, V. Detection of Potential Biodeterioration Risks for Tempera Painting in 16th Century Exhibits from State Tretyakov Gallery. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0230591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdanina, D.A.; Zhgun, A.A. Rainbow code of biodeterioration to cultural heritage objects. Herit. Sci. 2024 121 2024, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, C.; Bordalo, R.; Silva, M.; Rosado, T.; Candeias, A.; Caldeira, A.T. On the Conservation of Easel Paintings: Evaluation of Microbial Contamination and Artists Materials. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2017, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M.G. , Mazzoli, R., Pessione, E. Back to the Past: Deciphering Cultural Heritage Secrets by Protein Identification. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 5445–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillón Rivera, L.E.; Palma Ramos, A.; Castañeda Sánchez, J.I.; Drago Serrano, M.E. Origin and Control Strategies of Biofilms in the Cultural Heritage. In Antimicrobials, Antibiotic Resistance, Antibiofilm Strategies and Activity Methods; IntechOpen, 2019; pp. 1–24.

- Paiva de Carvalho, H.; Mesquita, N.; Trovão, J.; Fernández Rodríguez, S.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Gomes, V.; Alcoforado, A.; Gil, F.; Portugal, A. Fungal contamination of paintings and wooden sculptures inside the storage room of a museum: Are current norms and reference values adequate? J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 34, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalar, P.; Graf Hriberšek, D.; Gostinčar, C.; Breskvar, M.; Džeroski, S.; Matul, M.; Novak Babič, M.; Čremožnik Zupančič, J.; Kujović, A.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; et al. Xerophilic fungi contaminating historically valuable easel paintings from Slovenia. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1258670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdanina, D.A.; Ermolyuk, A.A.; Bashkirova, K.Y.; Vorobyova, O.B.; Simonenko, N.P.; Shitov, M. V.; Zhgun, A.A. Determining the Source of Biodeterioration of the 16th Century Icon Deesis Tier of 13 Figures from the State Tretyakov Gallery. Microbiol. (Russian Fed. 2024, 93, S87–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. 1990, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.B.; Go, S.J.; Shin, H.D.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Mycologia 2005, 97, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous

ascomycetes. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051 2019, 91, 553–556. [CrossRef]

- Kosolapov A., I. Natural Scientific Methods in the Examination of Art Works; State Herm.; S.-Petersburg, 2015; ISBN 978-5-93572-636-2.

- Zhgun, A.; Avdanina, D.; Shumikhin, K.; Simonenko, N.; Lyubavskaya, E.; Volkov, I.; Ivanov, V. Detection of potential biodeterioration risks for tempera painting in 16th century exhibits from State Tretyakov Gallery. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0230591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.B.M.; Mahmoud, G.A.E.; Cordes, D.B.; Slawin, A.M.Z. Pb (II) and Hg (II) thiosemicarbazones for inhibiting the broad-spectrum pathogen Cladosporium sphaerospermum ASU18 (MK387875) and altering its antioxidant system. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Prakash, O. Biodegradation of mango kernel by Syncephalastrum racemosum and its biological control. BioControl 2006, 51, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati; Eltivitasari, A. ; Romadhonsyah, F.; Gemantari, B.M.; Nurrochmad, A.; Wahyuono, S.; Astuti, P. Effect of light exposure on secondary metabolite production and bioactivities of syncephalastrum racemosum endophyte. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 5, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treu, A. , Jeroen, Lückers, J. , Militz, H. Screening of modified linseed oils on their applicability in wood protection. In Proceedings of the The International Research Group on Wood Protection; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sytnik, N.; Korchak, M.; Nekrasov, S.; Herasymenko, V.; Mylostyvyi, R.; Ovsiannikova, T.; Shamota, T.; Mohutova, V.; Ofilenko, N.; Choni, I. Increasing the oxidative stability of linseed oil. Eastern-European J. Enterp. Technol. 2023, 4, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Cervantes, R.; Dias, M.; Gomes, B.; Pena, P.; Carolino, E.; Twarużek, M.; Kosicki, R.; Soszczyńska, E.; Viegas, S.; et al. Unveiling the Occupational Exposure to Microbial Contamination in Conservation–Restoration Settings. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepanowska, H.M. , Cavaliere, A.R. Artworks, Drawings, Prints, and Documents - Fungi Eat Them All! In Art, Biology, and Conservation; Koestler, R.J., Koestler, V.H., Charola, A.E., Nieto-Fernandez, F.E., Eds.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, 2003; pp. 128–151. [Google Scholar]

- Amatya, R.; Khanal, B.; Rijal, A. Syncephalastrum species producing mycetoma-like lesions. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2010, 76, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.; Prakash, O.; Pandey, B.K.; Singh, B.P.; Pandey, G. First Report of Black Soft Rot of Indian Gooseberry Caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 575–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, S.; Ramya, T.G.; Geetha, R.K. Onychomycosis by syncephalastrum racemosum: case report from kerala, India. Dermatology reports 2015, 7, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.; Nasir, N.; Hashmi, U.H.; Farooqi, J.; Mahmood, S.F. Invasive pulmonary infection by Syncephalastrum species: Two case reports and review of literature. IDCases 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastaugh, N.; Walsh, V.; T., C.; R., S. Pigment compendium—A dictionary of historical pigments; Elsevier.;

Oxford, 2004; ISBN 0 7506 57499.

- Babich, H.; Stotzky, G. Toxicity of zinc to fungi, bacteria, and coliphages: influence of chloride ions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978, 36, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, B.; Niklińska, M. Zinc and copper toxicity to soil bacteria and fungi from zinc polluted and unpolluted soils: A comparative study with different types of biolog plates. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 78, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, H.; Eisendle, M.; Turgeon, B.G. Siderophores in fungal physiology and virulence. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2008, 46, 149–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosman, D.J. Redox cycling in iron uptake, efflux, and trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 26729–26735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, E.; Gómez-Gallego, T.; Azcón-Aguilar, C.; Ferrol, N. Genome-wide analysis of copper, iron and zinc transporters in the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Exterior facade of the Cathedral Old Believer Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos, Moscow:

(a) 1910-1917,

https://pastvu.com/p/2192143;

(b) Present time—the church has been converted into residential premises in 1950s, only the former altar of the church and the corner columns remain.

Figure 1.

Exterior facade of the Cathedral Old Believer Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos, Moscow:

(a) 1910-1917,

https://pastvu.com/p/2192143;

(b) Present time—the church has been converted into residential premises in 1950s, only the former altar of the church and the corner columns remain.

Figure 2.

Sampling map of the icon “Descent into Hell”: (a) Front side; (b) Back side. Sample numbers (1–10) are given in circles. Colors indicate: yellow–bacterial growth; red–bacterial and fungal growth; green–only fungal growth, and white–no growth.

Figure 2.

Sampling map of the icon “Descent into Hell”: (a) Front side; (b) Back side. Sample numbers (1–10) are given in circles. Colors indicate: yellow–bacterial growth; red–bacterial and fungal growth; green–only fungal growth, and white–no growth.

Figure 3.

Morphological forms of Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 on PDA medium, 26 °C: (a) 6 days culture; (b) Lateral view via light microscopy, 500 µm; (c) Transmission light microscopy of conidiophore (1), ovate conidia (2); and ramo-conidia (3), 50 µm; (d) Fluorescent microscopy, 50 µm; (e, f) SEM of fungi biofilm, 20 µm, 100 µm.

Figure 3.

Morphological forms of Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 on PDA medium, 26 °C: (a) 6 days culture; (b) Lateral view via light microscopy, 500 µm; (c) Transmission light microscopy of conidiophore (1), ovate conidia (2); and ramo-conidia (3), 50 µm; (d) Fluorescent microscopy, 50 µm; (e, f) SEM of fungi biofilm, 20 µm, 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Morphological forms of Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 on PDA medium, 26 °C: (a) 6 days culture; (b) Lateral view via light microscopy with sporangia carriers (1), and sporangia heads (2), 500 µm; (c) Transmission light microscopy of sporangia carriers (1), vesicles (2) and ruptured vesicle (3), merosporangia filled with spherical merospores (4), 50 µm; (d) Fluorescent microscopy, 50 µm; (e, f) SEM of conidiophores (1) with young merosporangia (4) , 20 µm, 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Morphological forms of Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 on PDA medium, 26 °C: (a) 6 days culture; (b) Lateral view via light microscopy with sporangia carriers (1), and sporangia heads (2), 500 µm; (c) Transmission light microscopy of sporangia carriers (1), vesicles (2) and ruptured vesicle (3), merosporangia filled with spherical merospores (4), 50 µm; (d) Fluorescent microscopy, 50 µm; (e, f) SEM of conidiophores (1) with young merosporangia (4) , 20 µm, 100 µm.

Figure 5.

Paint layers biodegraded by fungi: (a) Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and (b) Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 after inoculation, photos on 2nd, 6th and 12th days.

Figure 5.

Paint layers biodegraded by fungi: (a) Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and (b) Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 after inoculation, photos on 2nd, 6th and 12th days.

Figure 6.

Dynamics of biodegradation of mock layers by Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 after 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 12th days after inoculation. Green zones correspond to growth absence, and dark blue zones—complete biodegradation of art material.

Figure 6.

Dynamics of biodegradation of mock layers by Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 and Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160 after 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 12th days after inoculation. Green zones correspond to growth absence, and dark blue zones—complete biodegradation of art material.

Figure 7.

SEM of micro-scrapings from the icon’s surface: (a) Area of the Holy Fathers faces image; (b) A single spore (1) of the mold fungus Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160, 10 µm; (c) Area of the Holy Fathers chitons image; (d) Mycelial hypha of Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 (1) and crystalline structures of fatty acids (2), 50 µm.

Figure 7.

SEM of micro-scrapings from the icon’s surface: (a) Area of the Holy Fathers faces image; (b) A single spore (1) of the mold fungus Syncephalastrum sp. STG-160, 10 µm; (c) Area of the Holy Fathers chitons image; (d) Mycelial hypha of Cladosporium sphaerospermum STG-161 (1) and crystalline structures of fatty acids (2), 50 µm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).