1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have achieved significant advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. To better guide their reasoning process, researchers have introduced In-Context Learning (ICL) [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] prompting has demonstrated significant effectiveness in enhancing the performance of LLMs. Unlike traditional prompts that require the model to directly produce an answer, often resulting in abrupt reasoning and hallucinations [

14,

15,

16,

17], causing logical errors, CoT encourages the model to articulate intermediate reasoning steps. By decomposing complex problems into smaller subtasks, this approach facilitates error tracing and substantially improves output accuracy, particularly in domains such as mathematical and symbolic reasoning.

In traditional CoT, the reasoning process generated by LLMs is often difficult to effectively verify for authenticity [

18]. Moreover, CoT prompts typically require task-specific adjustments for different application scenarios, lacking generality and scalability [

13,

19,

20]. Existing approaches [

13,

21,

22,

23,

24] still rely heavily on costly downstream evaluations and lack a principled optimization framework for prompt design. These limitations motivate us to explore a more efficient and theoretically grounded approach.

Given the high cost of manual prompt verification and the inherent variability of prompts, leveraging LLMs for self-evaluation emerges as a more scalable and practical solution. Compared to fine-tuning LLMs for evaluation purposes, CoT-based prompting offers a parameter-efficient alternative, enabling prompt assessment without modifying the underlying model.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and adversarial learning [

25] have achieved remarkable success in various domains, including image generation [

25,

26] and model robustness enhancement [

27,

28]. At their core, GANs consist of a generator-discriminator framework where the generator aims to increase the likelihood of the discriminator making errors by producing data indistinguishable from real samples, while the discriminator seeks to correctly differentiate between generated and authentic data. Throughout training, both components evolve adversarially.

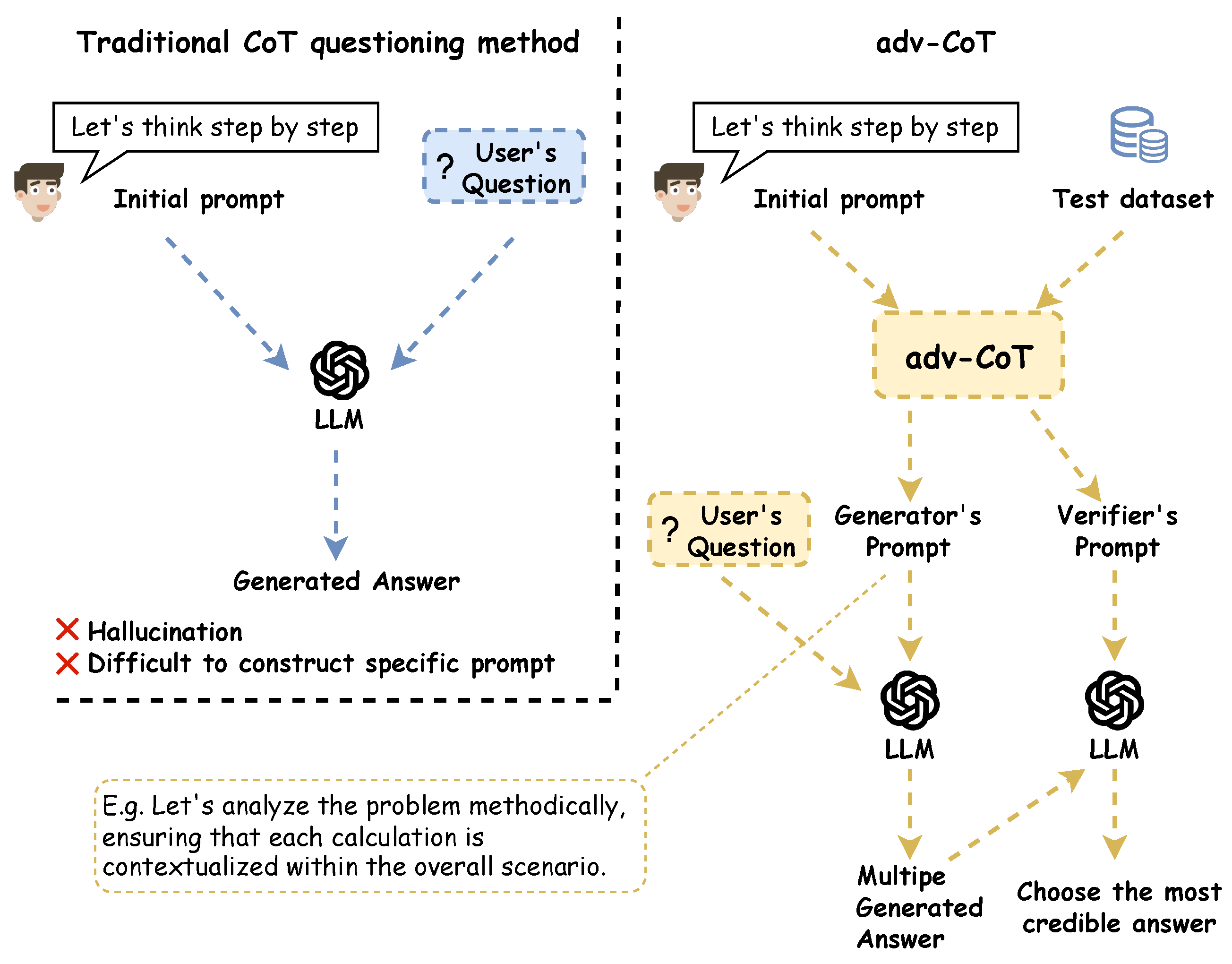

Inspired by GANs and Adversarial In-Context Learning (adv-ICL) [

29], we introduce adversarial learning into the evaluation and optimization of CoT prompts. We propose the Adversarial Chain-of-Thought (adv-CoT) framework, which takes an initial prompt as input and, through several rounds of iterative refinement, produces two fully developed sets of CoT-based instructions and demonstrations, with one serving as the generator and the other as the discriminator. Without modifying model parameters, adv-CoT enhances LLM performance by optimizing prompts adversarially. The comparison between the traditional CoT method and our adv-CoT is illustrated in

Figure 1.

We evaluate adv-CoT on 12 datasets spanning diverse reasoning types, including commonsense, factual, symbolic, and arithmetic tasks. Results demonstrate that adv-CoT effectively optimizes prompts and improves model output accuracy. Furthermore, combining Self-Consistency (SC) [

18] with adv-CoT yields strong performance across multiple datasets. The framework is also highly extensible and can integrate with other prompt-related methods for further improvement. adv-CoT requires only an initial prompt as input and can generate optimized prompts after a few training iterations. Its independence from model parameters and architectures enables practical deployment in real-world applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Prompt Optimization for Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

CoT prompting has been shown to significantly improve reasoning performance in LLMs [

9,

10]. However, whether prompts are manually created or automatically generated, their effectiveness is still mainly assessed through computationally intensive downstream tasks, with costs increasing as the number of candidate prompts, sampled reasoning paths, and task instances grows [

13,

30,

31]. Recent research has proposed more systematic optimization methods, including black box optimization [

32] and Bayesian optimization combined with Hyperband [

33]. These methods still provide limited theoretical guarantees for reasoning trajectories. Methods focusing on process-level evaluation, such as process supervision and PRM800K [

34], offer promising alternatives to evaluation based solely on final task outcomes, but they remain in early development. Meanwhile, studies on robust prompt optimization [

35] and uncertainty-aware evaluation [

36] highlight the need for a unified framework that can simultaneously improve efficiency, robustness, and reasoning quality in CoT prompting.

2.2. Adversarial Training

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were first introduced by Goodfellow et al. [

25], establishing a minimax game framework in which the generator is incentivized to produce high-fidelity outputs. This adversarial paradigm has achieved remarkable success in tasks such as image generation [

25,

26], super-resolution [

37], and domain adaptation [

38,

39]. While GANs have been widely adopted in the field of computer vision [

40], applying them to discrete domains like text generation remains challenging due to the non-differentiability of sampling operations [

41,

42]. To overcome these difficulties, various enhancements [

43,

44] have been developed to stabilize the training process and reduce exposure bias.

When applying GANs to LLMs, direct parameter updates are often infeasible due to the high computational cost. In this context, leveraging adversarial learning for prompt optimization presents a more practical and efficient alternative. adv-ICL [

29] is the first to leverage adversarial learning to optimize prompts for in-context learning. While motivated by similar principles, adv-ICL and our method differ in several key aspects. Specifically, compared to adv-ICL, adv-CoT not only considers the outputs of the generator during training but also incorporates the discriminator’s loss to filter and refine generated prompts. This joint optimization enables both the generator and the discriminator to improve simultaneously, thereby maximizing the effectiveness of the training framework. Moreover, adv-ICL suffers from training instability due to the inherent variability in prompt candidates generated by LLMs, resulting in fluctuating loss values and increased training iterations, which ultimately raise computational costs. Conversely, adv-CoT addresses this issue by introducing a feedback mechanism during the discriminator phase: it identifies errors and provides revision suggestions to guide the generation of more effective prompt variants. This targeted guidance substantially reduces the number of required training iterations, improving efficiency while preserving performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Adversarial Learning

Adversarial learning serves as the core component of the adv-CoT framework, which consists of two main modules: a generator and a discriminator. Both modules are powered by an LLM and utilize CoT prompting. The generator produces answers based on the given instruction and CoT demonstrations, while the discriminator evaluates whether the input answer is correct or generated by the generator, also using the instruction and CoT demonstrations for guidance.

In addition, a modifier module refines the prompts based on the discriminator’s judgments and revision suggestions. It generates new instruction-example pairs, and the system selects the optimal pair based on the computed loss value to update both the generator and the discriminator. The detailed training procedure is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Generator: The generator G is guided by a prompt , which consists of an instruction and a set of input-output demonstrations , where denotes an example input and is the corresponding output. The generator takes a user query as input and produces an answer as output.

Discriminator: The discriminator D is guided by a prompt , which consists of an instruction and a set of input-output demonstrations , where is an example input, is the corresponding output, and represents the discriminator’s decision and rationale for that example. D takes as input the user’s question along with the answer generated by the generator and outputs a binary decision indicating whether the answer is likely to be genuine or generated.

Modifier: The modifier M, driven by an LLM, is guided by a prompt that consists of a single instruction. This instruction includes two parts: , which specifies how to revise the generator’s and discriminator’s instructions ( and ), and , which guides the modification of the demonstrations ( and ). The modifier operates under a zero-shot prompting setting. Based on this instruction, the modifier generates multiple prompt variants and for the generator and discriminator, respectively. These variants are then used to recompute the loss function, enabling iterative updates to both the generator and discriminator.

3.2. Feedback

In adv-ICL, the discriminator merely identifies correctness, offering limited actionable feedback for subsequent optimization. This limitation becomes more significant in the context of LLMs, where the parameters updated by the modifier M are expressed as explicit textual prompts. Due to the inherent randomness in LLM outputs, the direction of modification becomes uncertain, leading to instability in the loss function and increased computational cost. To address this issue, adv-CoT records the discriminator’s decisions, collecting input-output pairs that the generator fails to handle, as well as those that the discriminator misclassifies or cannot confidently judge. These challenging cases are then passed to the Proposer, an LLM-driven module that generates targeted revision suggestions. This process offers explicit guidance for the modifier, effectively directing the prompt updates and improving training efficiency.

3.3. Adversarial Learning Algorithm

Algorithm 1 provides a detailed description of our adv-CoT. Inspired by GANs and adv-ICL, the training objective loss function of adv-CoT is defined as follows:

where

denote the real data distribution, and

represent the expectation with respect to the indicated distribution. The discriminator

D outputs one of two options: “(A) Correct ground truth” or “(B) Generated output.” The confidence scores associated with these discriminator outputs are treated as expectation values during iterative training. For the discriminator

D, the objective is to maximize the loss (considering that confidence scores are negative) to better distinguish generated answers from real ones. Conversely, the generator

G aims to minimize the loss to avoid being detected as incorrect by the discriminator. Thus, the entire training process can be formulated as a minimax optimization problem:

|

Algorithm 1:Adversarial Chain-of-Thought Optimization |

- 1:

Input: Generator G, Discriminator D, Proposer P, Modifier M

- 2:

Input: Prompts , , ,

- 3:

Input: Number of iterations , demonstrations , max candidates

- 4:

Input: Demonstration set S

- 5:

fortodo

- 6:

Sample examples from S and compute initial loss J

- 7:

for all target ∈ {instruction, demonstration} do

- 8:

P generates from and D’s outputs - 9:

for to do

- 10:

M generates new candidate using , , and J

- 11:

Compute loss for

- 12:

if then

- 13:

Update candidate and loss: ,

- 14:

break

- 15:

end if

- 16:

end for

- 17:

end for

- 18:

// Similarly optimize for G to minimize J

- 19:

… - 20:

end for - 21:

Output: Optimized prompts ,

|

The final outcome of the training yields a new set of prompts and , corresponding to an updated generator and discriminator .

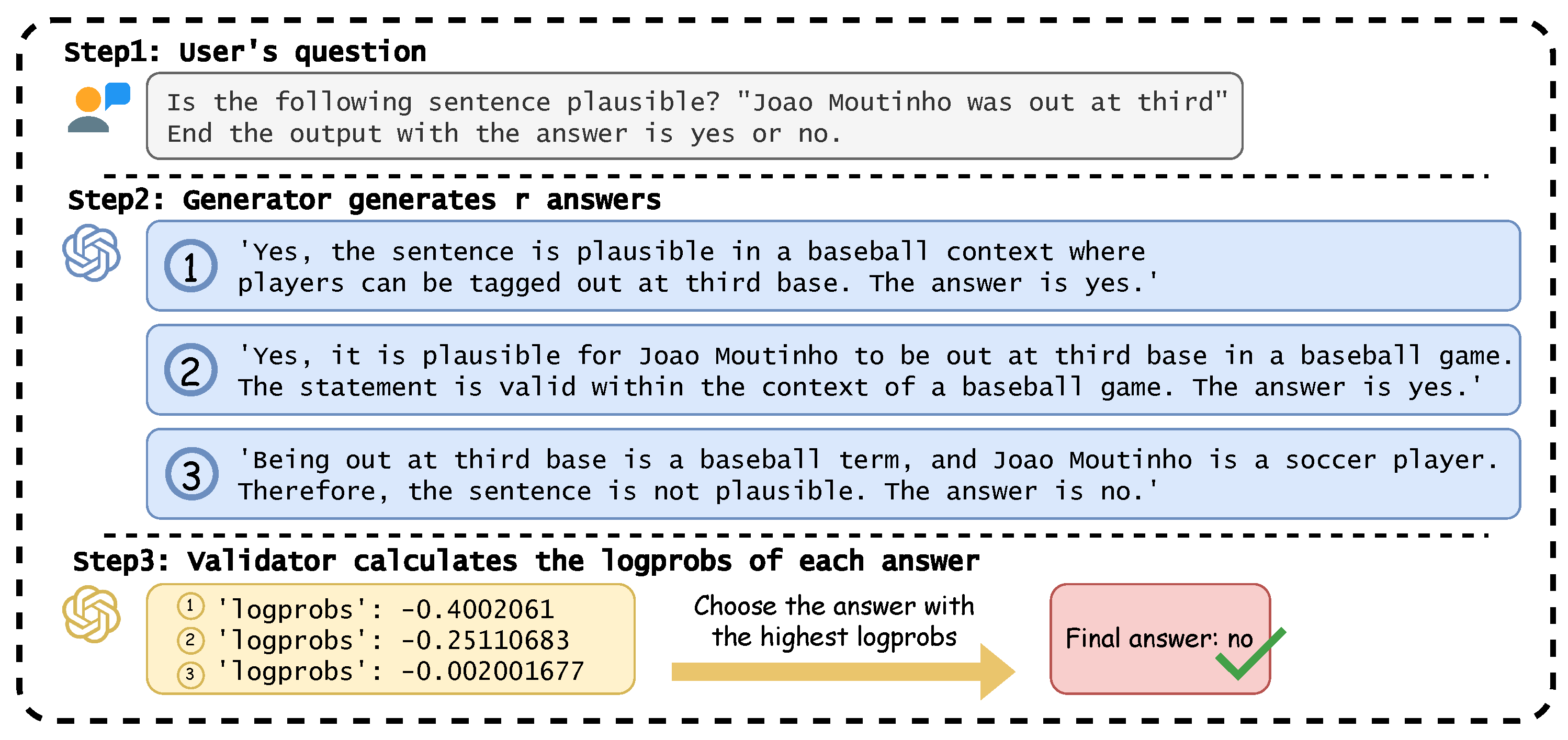

3.4. Verifier

The Verifier

V refers to the trained discriminator

. Given a user query, the updated generator

produces an answer, which is then evaluated by the verifier. The verifier performs

r rounds of evaluation, and the answer with the highest confidence score (i.e., the one associated with the greatest loss value) is selected as the final output. While prior prompting methods have explored ways to verify LLM-generated outputs, most rely on the LLMs to make simple judgments without a clear evaluation criterion or standard. In contrast, during adversarial training, both the generator and discriminator evolve together. This co-training allows the generator to produce more accurate outputs and the discriminator to serve as a reliable verifier. Traditional applications of GANs often focus solely on the generator after training, overlooking the discriminator. However, in the adv-CoT framework, the discriminator offers explicit verification signals, effectively enhancing the reliability and accuracy of the final answers. A more detailed illustration can be found in

Figure 3.

4. Experiment Setup

4.1. Datasets

Following previous work [

45], we selected three types of datasets in our experiments. The details are as follows: 1) Commonsense & factual reasoning. This category includes CommonsenseQA (CSQA) [

46], StrategyQA [

47], OpenBookQA [

48], the AI2 Reasoning Challenge (ARC-c) [

49], a sports understanding task from the BIG-Bench benchmark [

50], and BoolQ [

51]. These datasets are used to evaluate performance on commonsense and factual reasoning capabilities. 2) Symbolic reasoning. We evaluate two symbolic reasoning tasks: Last Letter Concatenation and Coin Flip [

9]. 3) Arithmetic reasoning. This category includes grade-school math problems from GSM8K [

52], the challenging math word problem dataset SVAMP [

53], as well as AQuA [

54] and MultiArith [

55], which are all used for assessing mathematical problem-solving abilities. The detailed descriptions of the datasets can be found in

Appendix A.

4.2. Implementation Details

We conducted experiments on both GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4o-mini. The applicability of the open-source model can be referred to

Appendix B.1. During the experiments, the generator, discriminator, proposer, and modifier were all powered by the same model. To encourage diverse outputs, we set the temperature to 0.6 for the generator, proposer, and modifier, while the discriminator operated with a temperature of 0 for deterministic judgment. Considering the training cost, we set the number of reasoning paths evaluated by the verifier to 3. All datasets are configured with 5 samples, except for Letter, which is set to 4. More details about the parameters can be found in

Appendix B.2. During the experiments, the log-probabilities of the output tokens are used as a reference signal for computing the loss. For each dataset, we initialized the generator prompt

and discriminator prompt

as follows. The instruction for the generator

was set to "Let’s think step by step" [

10]. We adopted initial demonstrations for the generator based on prior work [

45]. For the discriminator

, we extended the adv-ICL [

29] discriminator prompt by incorporating an explicit reasoning requirement: "Judge whether the answer is the correct ground truth or a generated fake answer, and provide the reasoning process. You should make a choice from the following two options: (A) correct ground truth, (B) generated fake answer." The initial demonstrations for the discriminator used input-output pairs from the generator as input, while the output was constructed by directly appending

to the input under a zero-shot prompting setting using GPT-4, to elicit the model’s reasoning process. The detailed prompts can be found in

Appendix C.

4.3. Baselines

We begin our experiments with CoT [

45] prompting and enhance it with Self-Consistency [

18], using 10 sampled reasoning paths per input. To highlight the effectiveness of our framework, adv-ICL [

29] is adopted as a baseline.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results

As shown in

Table 1, adv-CoT achieves highly competitive results across most tasks and settings.

On GPT-3.5-turbo, adv-CoT achieves the best performance on OpenBookQA (86.8), ARC-c (89.5), Sports (91.8), BoolQ (91.8), Letter (76.0), AQuA (66.1), and MultiArith (99.1), demonstrating strong reasoning capabilities across factual, symbolic, and arithmetic domains. With the optimization introduced by adv-CoT, GPT-3.5-turbo achieves performance gains of 1.7%, 15.8%, and 2.4% over the initial prompts across the three dataset types. Compared to CoT and adv-ICL, our method exhibits greater stability and robustness in multi-step logical reasoning tasks.

With the more powerful GPT-4o-mini model, adv-CoT continues to lead, achieving top results on StrategyQA (79.3), ARC-c (95.3), Sports (93.1), BoolQ (77.5), Letter (91.0), Coin (100), and MultiArith (98.6). These results further confirm that our method is both scalable and robust as model capacity increases.

While CoT combined with SC yields moderate improvements on some tasks (e.g., GSM8K and SVAMP), SC can also be integrated with our method to further boost accuracy by increasing the number of reasoning paths. The relationship between the two approaches will be further explored in

Section 5.2.2. adv-ICL, although designed as an adversarial optimization method, underperforms on symbolic and arithmetic reasoning tasks. This suggests that adversarial learning alone is insufficient for stable multi-step inference without explicit structural verification.

In contrast, the strength of adv-CoT lies in combining adversarial prompt optimization with structured reasoning chains and explicit verification. Its strong performance on multiple datasets demonstrates that adversarially refined reasoning steps not only enhance factual consistency but also improve procedural accuracy, which is critical for complex reasoning tasks.

In summary, adv-CoT combines the interpretability of CoT prompting with adversarial training for prompt optimization, while retaining the discriminator as a verifier. Through well-structured and dynamically optimized prompts, it delivers stable and scalable improvements across a broad range of reasoning tasks.

5.2. Discussion

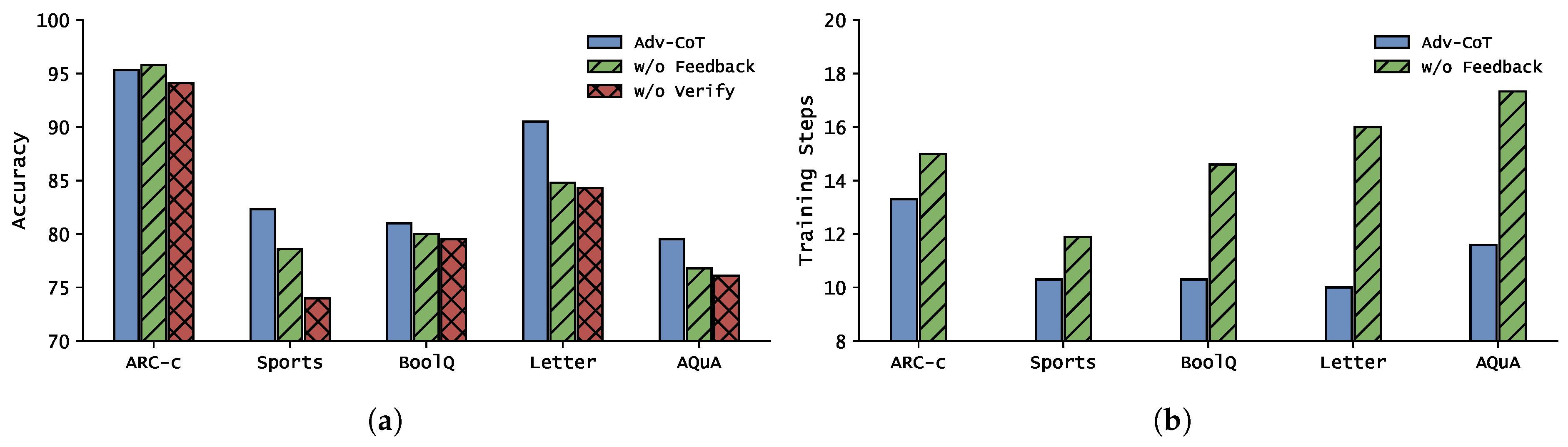

5.2.1. Ablation Study

To quantify the individual contributions of the feedback and verification components in our framework, we perform ablation experiments on five datasets (ARC-C, Sports, BoolQ, Letter, AQuA) using GPT-4o-mini. We compare three variants: the full adv-CoT framework, adv-CoT without feedback (w/o feedback), and adv-CoT without verification (w/o verification). The full and no-verification variants use the same optimized prompts so that any differences can be attributed to the presence or absence of the corresponding module. The results are shown in

Figure 4.

The full adv-CoT yields accuracies of 95.3%, 82.3%, 81.0%, 90.5%, and 79.5% on ARC-C, Sports, BoolQ, Letter, and AQuA, respectively. Removing the feedback component produces accuracies of 95.8%, 78.6%, 80.0%, 84.8%, and 76.8%, while removing verification produces 94.1%, 74.0%, 79.5%, 84.3%, and 76.1%. In other words, with the exception of ARC-C (where omitting feedback gives a marginal increase of 0.5 percentage points), removing either component degrades performance on the remaining four datasets. The accuracy drops are most pronounced when verification is removed on Sports (−8.3 percentage points) and Letter (−6.2 percentage points), and when feedback is removed on Letter (−5.7 percentage points) and Sports (−3.7 percentage points). These magnitudes indicate that verification contributes a particularly strong robustness benefit on high-variance tasks, while feedback is crucial for maintaining stable gains across multiple datasets.

We also observe consistent trends in the training process. The feedback mechanism not only improves the final accuracy but also accelerates convergence, leading to lower training loss and reduced training steps. Without feedback, the model exhibits higher final loss and slower optimization. This suggests that feedback provides more effective gradient guidance, while verification enhances the stability of the reasoning outputs. Overall, both mechanisms play complementary roles: feedback drives efficient learning, and verification ensures the robustness of the final reasoning results.

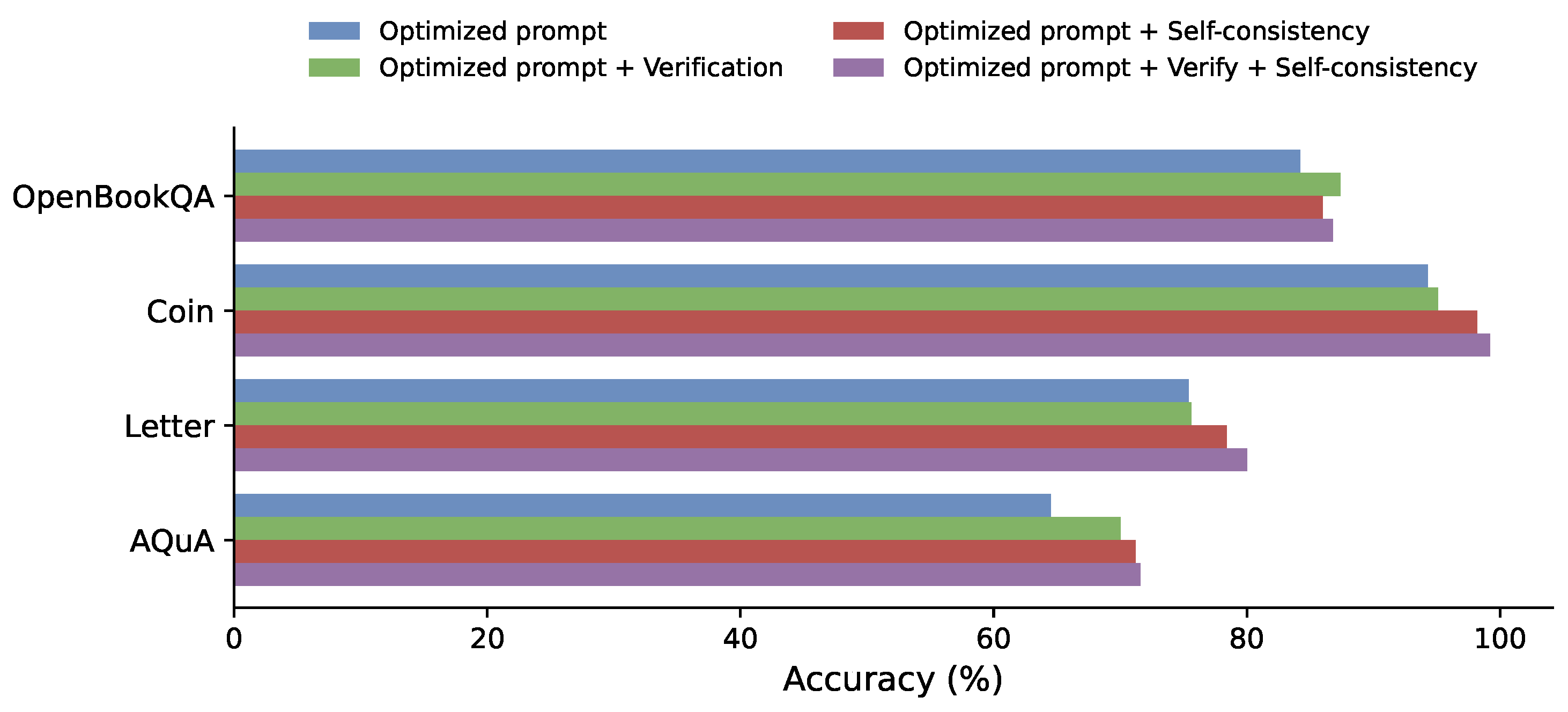

5.2.2. Difference between verification and self-consistency

Although both the verifier mechanism and Self-Consistency (SC) involve generating multiple reasoning paths, their underlying selection strategies differ substantially. The verifier aims to identify the answer with the highest confidence based on a learned evaluation criterion, whereas SC adopts a majority-vote approach, selecting the most frequently occurring answer among the generated reasoning paths. To empirically examine this distinction, we compare four model variants on four datasets (OpenBookQA, Coin, Letter, and AQuA): (1) optimized prompts only, (2) optimized prompts with verifier, (3) optimized prompts with SC, and (4) optimized prompts with both verifier and SC.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, introducing either verification or SC leads to consistent performance improvements over the optimized-prompt baseline.

Specifically, the baseline achieves accuracies of 84.2%, 94.3%, 75.4%, and 64.5% on the four datasets, respectively. When incorporating the verifier, accuracy improves to 87.4%, 95.1%, 75.6%, and 70.0%. In contrast, SC yields stronger gains, reaching 86.0%, 98.2%, 78.4%, and 71.2%. This indicates that SC’s majority-voting mechanism better mitigates stochastic reasoning errors compared to confidence-based verification. Moreover, when combining both strategies, performance further improves to 86.8%, 99.2%, 80.0%, and 71.6%, achieving the highest accuracy across all datasets. These results suggest that the two mechanisms are complementary: the verifier enhances answer reliability, while SC improves overall reasoning robustness through diversity aggregation.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we propose adv-CoT, a novel framework designed for prompt evaluation and optimization. By leveraging LLMs to refine prompts without parameter updates, our method achieves significant accuracy improvements. Built upon adv-ICL, adv-CoT introduces a feedback mechanism that enables controllable and guided refinement of prompt variants. Additionally, the incorporation of a verification mechanism allows the framework to better utilize the discriminator for validating generator outputs, further enhancing prediction accuracy. By integrating verification with Self-Consistency, our approach takes advantage of multiple reasoning paths and achieves state-of-the-art performance on several benchmark datasets. In future work, we aim to further optimize the training pipeline, reducing time and computational costs. We also plan to enhance the controllability of the modifier’s outputs and mitigate overfitting during training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang, Juhua Liu; methodology, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang, Juhua Liu; software, Guang Yang; validation, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang; formal analysis, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai; investigation, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai; resources, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang, Juhua Liu; data curation, Guang Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Guang Yang; writing—review and editing, Guang Yang, Xiantao Cai, Shaohe Wang, Juhua Liu; visualization, Guang Yang; supervision, Xiantao Cai, Juhua Liu; project administration, Juhua Liu; funding acquisition, Shaohe Wang, Juhua Liu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the State Grid Corporation Headquarters Science and Technology Project: Research on equipment operation and inspection disposal reasoning technology based on knowledge-enhanced generative model and intelligent agent and demonstration application (5700-202458333A-2-1-ZX).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4o, OpenAI) for the purposes of polishing parts of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The numerical calculations in this paper have been done on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CoT |

Chain-of-Thought |

| adv-CoT |

Adversarial Chain-of-Thought |

| LLMs |

Large Language Models |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| GANs |

Generative Adversarial Networks |

| adv-ICL |

Adversarial In-Context Learning |

| SC |

Self-Consistency |

Appendix A. Statistics of Datasets

Following prior work, we conduct evaluations on twelve datasets covering arithmetic reasoning, commonsense reasoning, symbolic reasoning, and natural language understanding. The statistics of these datasets are presented in

Table A1, and detailed information for each dataset is provided below.

Table A1.

Dataset Descriptions.

Table A1.

Dataset Descriptions.

| Dataset |

Number of samples |

Average words |

Answer Format |

Licence |

| CSQA |

1,221 |

27.8 |

Multi-choice |

Unspecified |

| StrategyQA |

2,290 |

9.6 |

Yes or No |

Apache-2.0 |

| OpenBookQA |

500 |

27.6 |

Multi-choice |

Unspecified |

| ARC-c |

1,172 |

47.5 |

Multi-choice |

CC BY SA-4.0 |

| Sports |

1,000 |

7.0 |

Yes or No |

Apache-2.0 |

| BoolQ |

3,270 |

8.7 |

Yes or No |

CC BY SA-3.0 |

| Last Letters |

500 |

15.0 |

String |

Unspecified |

| Coin Flip |

500 |

37.0 |

Yes or No |

Unspecified |

| GSM8K |

1,319 |

46.9 |

Number |

MIT License |

| SVAMP |

1,000 |

31.8 |

Number |

MIT License |

| AQuA |

254 |

51.9 |

Multi-choice |

Apache-2.0 |

| MultiArith |

600 |

31.8 |

Number |

CC BY SA-4.0 |

CSQA [

46]: it is a multiple-choice question answering dataset that evaluates models’ ability to apply commonsense knowledge in reasoning tasks. It contains diverse questions that require understanding everyday situations beyond factual recall. The homepage is

https://github.com/jonathanherzig/commonsenseqa.

Appendix B. Extended Experiments

Appendix B.1. Applicability on Open-Source Models

To further examine the adaptability of the proposed framework to open-source language models, we conducted supplementary experiments on Llama-3-8B-Instruct [

56] across twelve representative benchmarks. As shown in

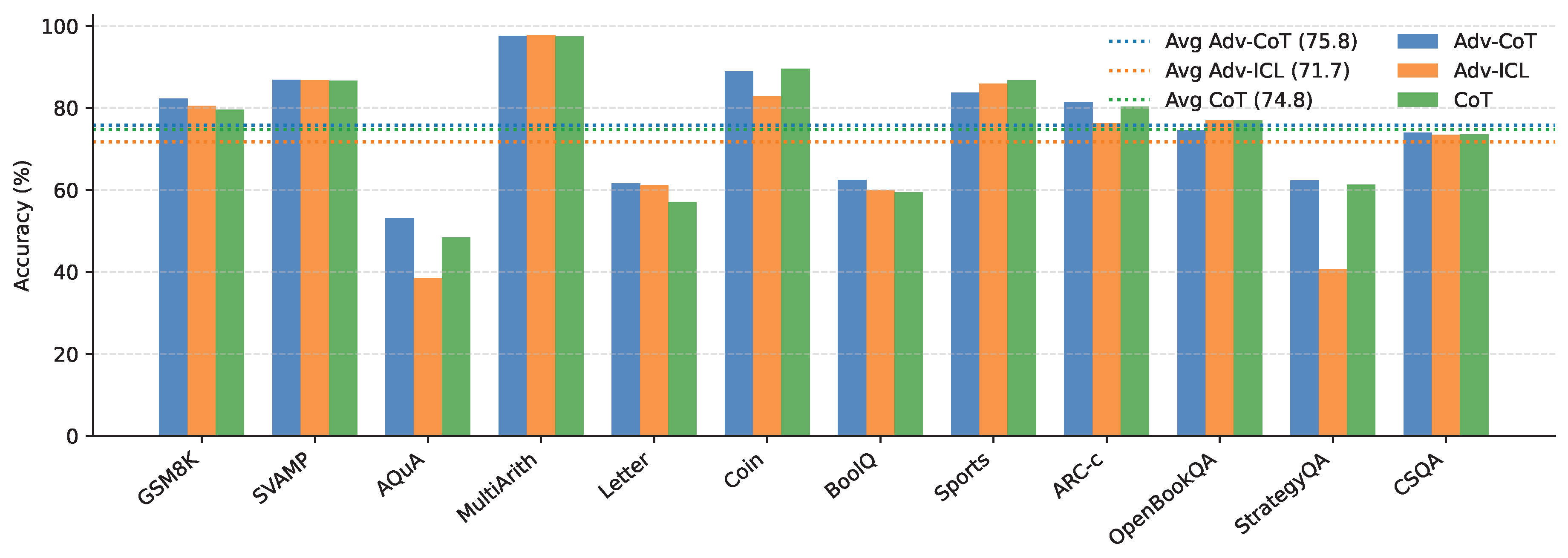

Figure A1, adv-CoT achieves the highest or comparable accuracy on most datasets, outperforming both CoT and adv-ICL in terms of average performance. Specifically, adv-CoT attains a mean accuracy of 75.8%, which is slightly higher than CoT (74.8%) and adv-ICL (71.7%). It achieves notable gains on several datasets, such as AQuA (+4.7), BoolQ (+3.1), and ARC-c (+1.1), indicating its robustness and consistency across both arithmetic and commonsense reasoning tasks.

Figure A1.

Performance Comparison of Different Methods on Llama-3-8B-Instruct.

Figure A1.

Performance Comparison of Different Methods on Llama-3-8B-Instruct.

However, the overall improvement on Llama-3-8B-Instruct remains marginal compared to results obtained on larger or closed-source models. This phenomenon may be attributed to the relatively limited reasoning capacity of smaller open-source models, which makes the feedback generated by adversarial optimization less reliable and occasionally misleading for prompt refinement. In other words, when the base model’s internal reasoning ability is insufficient, the self-generated adversarial feedback may not always guide the optimization process in a constructive direction. Nevertheless, the consistent performance of adv-CoT across different datasets demonstrates its potential as a general reasoning enhancement framework even under constrained model capacity, suggesting promising scalability for future integration with stronger open-source LLMs.

Appendix B.2. Ablation Studies on Number of Iterations and Data Samples

To further validate the robustness of adv-CoT and investigate the impact of its key hyperparameters, we conducted additional ablation experiments with different combinations of the number of iterations (

) and the number of prompt samples (

). The evaluation was carried out on three benchmark datasets: MultiArith, ARC-C, and Sports. For each

, the iteration number

was varied from 1 to 5, and the results are reported in

Table A2. All scores are presented in percentages with one decimal place for clarity and consistency.

Table A2.

Ablation results of adv-CoT with different and values.

Table A2.

Ablation results of adv-CoT with different and values.

|

|

MultiArith (%) |

ARC-C (%) |

Sports (%) |

| 1 |

1 |

97.6 |

72.7 |

60.1 |

| |

2 |

95.0 |

76.6 |

51.1 |

| |

3 |

98.1 |

80.8 |

50.8 |

| |

4 |

97.8 |

81.9 |

65.6 |

| |

5 |

96.6 |

78.4 |

64.1 |

| 3 |

1 |

98.3 |

78.7 |

61.9 |

| |

2 |

98.3 |

80.5 |

66.1 |

| |

3 |

98.8 |

80.7 |

78.9 |

| |

4 |

98.6 |

79.9 |

71.3 |

| |

5 |

98.0 |

79.7 |

58.0 |

| 5 |

1 |

98.1 |

71.9 |

82.1 |

| |

2 |

97.6 |

75.1 |

76.9 |

| |

3 |

98.3 |

79.9 |

88.7 |

| |

4 |

97.6 |

78.8 |

57.5 |

| |

5 |

97.8 |

77.8 |

76.4 |

| 7 |

1 |

97.6 |

73.8 |

85.6 |

| |

2 |

98.0 |

75.4 |

89.5 |

| |

3 |

98.0 |

82.4 |

80.7 |

| |

4 |

97.5 |

79.9 |

77.8 |

| |

5 |

97.5 |

80.7 |

84.8 |

Overall, the results demonstrate that both hyperparameters exert significant influence on model performance across datasets. For MultiArith, which primarily measures numerical reasoning ability, accuracy remains consistently high under most configurations, ranging from 95.0% to 98.8%. The best performance is obtained when and , indicating that moderate iteration depth and an appropriate number of prompt samples are beneficial for stable arithmetic reasoning. However, excessive iteration () or too few prompts tends to cause slight performance drops, possibly due to optimization saturation or insufficient contextual guidance.

In the ARC-C dataset, which emphasizes commonsense reasoning, the results show greater variation. When , performance peaks at 81.9% with , while most other settings remain below 80%. As the prompt number increases to and , performance becomes more stable, reaching best scores of 80.7% and 79.9%, respectively. When , the model achieves its overall best performance of 82.4% at , suggesting that moderate prompt diversity and iteration balance enhance generalization in abstract reasoning tasks.

For the Sports dataset, which relies more on factual and contextual reasoning, the model exhibits strong sensitivity to prompt diversity. With , accuracy increases gradually from 50.8% to 65.6% as the iteration deepens. When more prompts are introduced, performance improves substantially—reaching 78.9% at , 88.7% at , and peaking at 89.5% when and . This indicates that rich prompt contexts significantly benefit knowledge-intensive reasoning.

In summary, these supplementary results confirm that adv-CoT performs best when both the iteration number and prompt diversity are moderately balanced. Extremely small or large hyperparameter values tend to underfit or overfit the reasoning process. The optimal configuration, typically around and , provides a consistent trade-off between stability and adaptability, reinforcing the parameter choices used in the main experiments.

Appendix C. Prompt

We provide the prompt used in the experiment. The prompts for both the Generator and the Discriminator consist of an instruction and demonstrations. The demonstrations for the Generator are adapted from prior work, while those for the Discriminator are constructed by concatenating the Discriminator’s instruction with the input–output pairs of the Generator’s demonstrations, and then providing them as zero-shot prompts to GPT-4o-mini to obtain the corresponding outputs. Furthermore, the Proposer and Modifier offer revision suggestions and concrete modifications to the instructions and demonstrations of the Generator and the Discriminator, respectively. The detailed prompts are as follows:

Appendix C.1. Generator Initial Prompt

Let’s think step by step [

10].

Appendix C.2. Discriminator Initial Prompt

Judge the answer is correct ground truth or generated fake answer and give the reasoning process. You should make a choice from the following two answers. (A) correct ground truth (B)generated fake answer [

29].

Appendix C.3. Proposer Prompt for Generator’s Instruction

Below are examples in this format: <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> <answer> [Discriminator_Output] </answer>. In each case the discriminator marked the generator’s output as incorrect. In one sentence, give a precise, actionable modification to the generator’s instruction that targets common failure patterns to prevent similar mistakes. Do not mention the specific details of the errors, names, items or data in the examples. In conclusion, the words that appear in the examples must not be included in the suggestions. Old generator’s instruction: {instruction_generator}. Start the output with ’New generator’s instruction should ...’.

Appendix C.4. Proposer Prompt for Generator’s Demonstrations

Below are examples in this format: <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> <answer> [Discriminator_Output] </answer>. In each case the discriminator marked the generator’s output as incorrect. In up to one sentence, provide precise, actionable modifications to the generator’s examples that address these common failure patterns and steer its outputs away from similar errors. Do not mention the specific details of the errors, names, items or data in the examples. In conclusion, the words that appear in the examples must not be included in the suggestions. Old generator’s instruction : {instruction_generator}. Start the output with ’New generator’s examples should ...’.

Appendix C.5. Proposer Prompt for Discriminator’s Instruction

Below are examples in this format: <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> <answer> [Discriminator_Output] </answer>. In each case, the discriminator failed to detect errors in the generator’s output or identified the correct answer as incorrect. Please suggest concise, one-sentence edits to the discriminator’s instruction prompt so it more effectively detects generator output errors, focusing on common mistake patterns and how to reword the prompt to avoid them. Do not mention the specific details of the errors, names, items or data in the examples. In conclusion, the words that appear in the examples must not be included in the suggestions. Old discriminator instruction: {instruction_discriminator}. Start the output with ’New discriminator’s instruction should ...’.

Appendix C.6. Proposer Prompt for Discriminator’s Demonstrations

Below are examples in this format: <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> <answer> [Discriminator_Output] </answer>. In each case, the discriminator failed to detect errors in the generator’s output or identified the correct answer as incorrect. In up to one sentence, provide concise, actionable suggestions for designing new discriminator examples that more effectively expose common generator mistakes. Do not mention the specific details of the errors, names, items or data in the examples. In conclusion, the words that appear in the examples must not be included in the suggestions. Discriminator instruction: {instruction_discriminator}. Start the output with ’New discriminator’s examples should ...’.

Appendix C.7. Modifier Prompt for Generator’s Instruction

Try to generate a new generator instruction to improve the correctness of the generator’s output. Keep the task instruction as declarative. The instruction should be precise and representative to inspire the generator to think. Extra suggestions are only for reference and can be ignored when they conflict with the overall situation.

Appendix C.8. Modifier Prompt for Generator’s Demonstrations

Please generate a new example that polish the following example to improve the correctness of the generator’s output. The example should be challenging, precise and representative to inspire the generator to think. The format of the examples should not be changed. Generator’s instruction is {instruction_generator_old}. Example must follow this XML format: <example> <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> </example>. Replace the content in [] with your output. Provide only the revised `<example>…</example>` blocks.

Appendix C.9. Modifier Prompt for Discriminator’s Instruction

Try to generate a new instruction to make LLM discriminator more precise to find LLM generator’s errors. Keep the task instruction as declarative. The instruction should be precise and representative to inspire the discriminator to think. Extra suggestions are only for reference and can be ignored when they conflict with the overall situation.

Appendix C.10. Modifier Prompt for Discriminator’s Demonstrations

Please generate a new example to make LLM discriminator more precise to find LLM generator’s errors. The example should be challenging, precise and representative to inspire the discriminator to think. The format of the examples should not be changed. Discriminator’s instruction is {instruction_discriminator_old}. Example must follow this XML format: <example> <input> [Question] </input> <output> [Answer] </output> <answer> [Discriminator_Output] </answer> </example>. Replace the content in [] with your output. Provide only the revised `<example>…</example>` blocks.

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc. Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; 2020; 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, J.W.; Borgeaud, S.; Cai, T.; Millican, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Song, F.; Aslanides, J.; Henderson, S.; Ring, R.; Young, S.; et al. Scaling Language Models: Methods, Analysis & Insights from Training Gopher. ArXiv 2021, arXiv:abs/2112.11446. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI.; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. 2024, arXiv:cs.CL/2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T.; Zhu, J. Foundations of Large Language Models. 2025, arXiv:cs.CL/2501.09223. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hajishirzi, H. MetaICL: Learning to Learn In Context. 2022, arXiv:cs.CL/2110.15943. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Dai, D.; Zheng, C.; Ma, J.; Li, R.; Xia, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, T.; et al. A Survey on In-context Learning. 2024, arXiv:cs.CL/2507.16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dherin, B.; Munn, M.; Mazzawi, H.; Wunder, M.; Gonzalvo, J. Learning without training: The implicit dynamics of in-context learning. 2025, arXiv:2507.16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 22199–22213. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xia, F.; Li, B.; He, S.; Liu, S.; Sun, B.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Large Language Models are Better Reasoners with Self-Verification. 2023, arXiv:cs.AI/2212.09561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Smola, A. Automatic Chain of Thought Prompting in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM computing surveys 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Ren, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, W.X.; Nie, J.Y.; Wen, J.R. The Dawn After the Dark: An Empirical Study on Factuality Hallucination in Large Language Models. 2024, arXiv:cs.CL/2401.03205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Jain, S.; Kankanhalli, M. Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models. 2025, arXiv:cs.CL/2401.11817. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yin, Z.; Guo, Q.; Wu, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, H. Benchmarking Hallucination in Large Language Models based on Unanswerable Math Word Problem. 2024, arXiv:2403.03558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Du, C.; Pang, T.; Liu, Q.; Gao, W.; Lin, M. Chain of Preference Optimization: Improving Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in LLMs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc. Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; 2024; 37, pp. 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Pan, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Active Prompting with Chain-of-Thought for Large Language Models. 2024, arXiv:cs.CL/2302.12246. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Gong, S.; Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Gao, J.; Shi, H.; Wu, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Bi, W.; et al. Diffusion of Thought: Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in Diffusion Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Curran Associates, Inc. Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; 2024; 37, pp. 105345–105374. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Jia, P.; Zhao, X. TAPO: Task-Referenced Adaptation for Prompt Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Larionov, D.; Eger, S. Promptoptme: Error-aware prompt compression for llm-based mt evaluation metrics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.16120. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.F.; Tsai, Y.D.; Lin, S.D. Benchmarking large language model uncertainty for prompt optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06434. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar]

- Biggio, B.; Corona, I.; Maiorca, D.; Nelson, B.; Šrndić, N.; Laskov, P.; Giacinto, G.; Roli, F. Evasion attacks against machine learning at test time. In Proceedings of the Joint European conference on machine learning and knowledge discovery in databases. Springer; 2013; pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.; Zhao, Y.; Brown, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, N.; Kawaguchi, K.; Shieh, M.; He, J. Prompt optimization via adversarial in-context learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024; pp. 7308–7327.

- Zhou, Y.; Muresanu, A.I.; Han, Z.; Paster, K.; Pitis, S.; Chan, H.; Ba, J. Large language models are human-level prompt engineers. In Proceedings of the The eleventh international conference on learning representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.T.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic prompt optimization with" gradient descent" and beam search. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03495. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, K.; Ke, P.; Wang, H.; Dong, Y.; Tang, J.; Huang, M. Black-box prompt optimization: Aligning large language models without model training. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.04155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Wistuba, M.; Klein, A.; Golebiowski, J.; Zappella, G.; Merra, F.A. Hyperband-based Bayesian optimization for black-box prompt selection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.07820. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, H.; Kosaraju, V.; Burda, Y.; Edwards, H.; Baker, B.; Lee, T.; Leike, J.; Schulman, J.; Sutskever, I.; Cobbe, K. Let’s verify step by step. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chua, T.S. Robust prompt optimization for large language models against distribution shifts. arXiv arXiv:2305.13954. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, D.; May, J. Language models can predict their own behavior. arXiv arXiv:2502.13329. [CrossRef]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 4681–4690.

- Ganin, Y.; Ustinova, E.; Ajakan, H.; Germain, P.; Larochelle, H.; Laviolette, F.; March, M.; Lempitsky, V. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. Journal of machine learning research 2016, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 7167–7176.

- Iglesias, G.; Talavera, E.; Díaz-Álvarez, A. A survey on GANs for computer vision: Recent research, analysis and taxonomy. Computer Science Review 2023, 48, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Cai, Y.; Li, Q. Unlocking the Power of GANs in Non-Autoregressive Text Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03977. [Google Scholar]

- Maus, N.; Chao, P.; Wong, E.; Gardner, J. Black box adversarial prompting for foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Seqgan: Sequence generative adversarial nets with policy gradient. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence; 2017; 31. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; Narodytska, N.; Patel, A. Relgan: Relational generative adversarial networks for text generation. In Proceedings of the International conference on learning representations; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Li, X.; Gao, M. Boosting language models reasoning with chain-of-knowledge prompting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.06427. [Google Scholar]

- Talmor, A.; Herzig, J.; Lourie, N.; Berant, J. COMMONSENSEQA: A Question Answering Challenge Targeting Commonsense Knowledge. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT; 2019; pp. 4149–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Geva, M.; Khashabi, D.; Segal, E.; Khot, T.; Roth, D.; Berant, J. Did aristotle use a laptop? a question answering benchmark with implicit reasoning strategies. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2021, 9, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, T.; Clark, P.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.02789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.; Cowhey, I.; Etzioni, O.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A.; Schoenick, C.; Tafjord, O. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; et al. Beyond the imitation game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Transactions on machine learning research 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Chang, M.W.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Collins, M.; Toutanova, K. Boolq: Exploring the surprising difficulty of natural yes/no questions. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.10044. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbe, K.; Kosaraju, V.; Bavarian, M.; Chen, M.; Jun, H.; Kaiser, L.; Plappert, M.; Tworek, J.; Hilton, J.; Nakano, R.; et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Bhattamishra, S.; Goyal, N. Are NLP models really able to solve simple math word problems? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.07191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Yogatama, D.; Dyer, C.; Blunsom, P. Program induction by rationale generation: Learning to solve and explain algebraic word problems. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.04146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Roth, D. Solving general arithmetic word problems. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.01413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI@Meta. Llama 3 Model Card, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).