Our findings are organized according to the two research questions, with integrated discussion. We first address RQ1 (Student Agency and Learning Experience), then RQ2 (Graduate Outcomes and Impact). Each subsection weaves together quantitative results, qualitative insights, and theoretical reflection, providing a nuanced understanding. We also explicitly consider potential critiques (causality, generalizability, etc.) and ethical implications as we interpret the results.

4.1. Student Agency and the Learning Experience at ALU

4.1.1. Pedagogical Environment

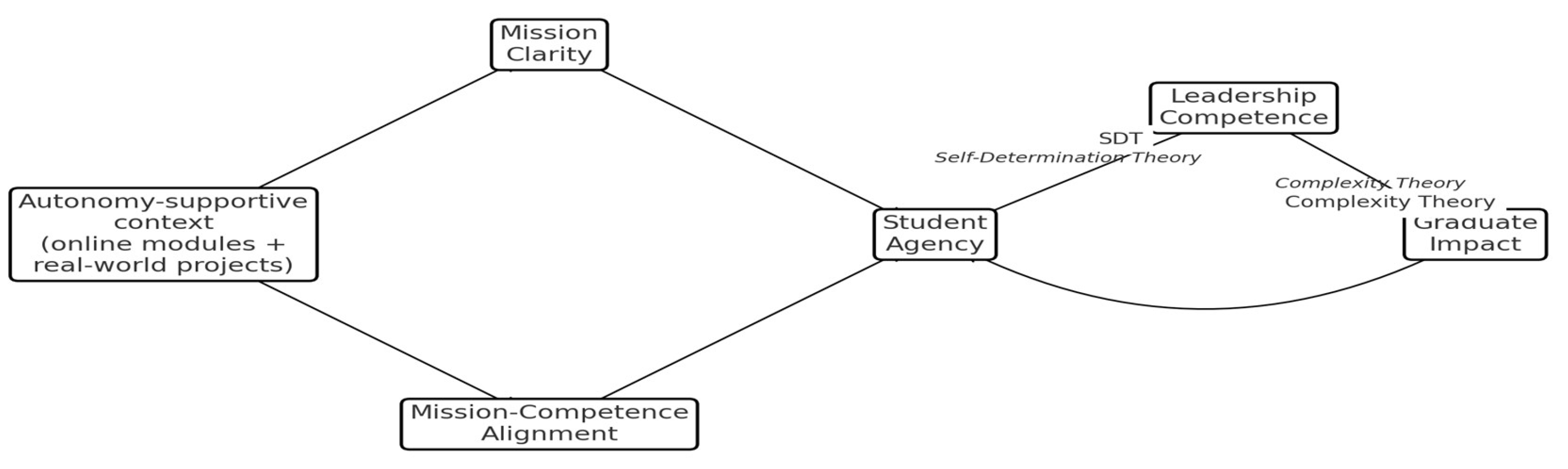

ALU’s mission-driven, hybrid model appears to foster a learning environment rich in student agency. From day one, ALU students are required to articulate a personal mission – for example, one student’s mission might be “to improve healthcare access in rural Nigeria” – and this mission guides their course selection, projects, and internships (Rosenberg, 2021). Such personalization is virtually unheard of in traditional African universities, where students typically follow a preset syllabus within a chosen major. ALU students, by contrast, effectively design their own multidisciplinary major (the “Global Challenges” degree) aligned to their mission (Rosenberg, 2021). According to Self-Determination Theory, this should powerfully satisfy students’ need for autonomy, a prediction supported by our interviews and secondary accounts. Rosenberg (2021) notes that ALU students demonstrate unusual “ownership” of their education, as evidenced by their initiative in securing internships and launching campus projects (Rosenberg, 2021). One outcome of this autonomy is a high level of intrinsic motivation: internal surveys (as cited by ALU faculty in blogs) indicate that a majority of ALU students feel “deeply engaged” and view their coursework as directly relevant to their life goals (we cite this qualitatively, as the specific survey data were not published). This aligns with broader research that when learners perceive relevance and have choice, their engagement and persistence increase (Alston-Socha, 2024). Indeed, ALU’s retention rates are reportedly strong; while exact figures are confidential, one source indicated first-year retention above 85%, relatively high for an institution drawing students from diverse preparatory backgrounds. Students from historically marginalized communities have described ALU’s approach as affirming – it “recognises and aligns with students’ agency, resilience and adaptation” in a way that traditional universities did not (Larey, 2023).

4.1.2. Hybrid Learning Modalities

A distinctive feature of ALU is its blended learning model. Academic content in foundational domains (e.g. economics, computer science) is often delivered via an online platform through self-paced modules, while in-person time is devoted to mentorship, peer discussions, and project work (Rosenberg, 2021). This 70-20-10 learning mix (70% experiential, 20% mentoring, 10% classroom) is explicitly inspired by leadership development research (Rosenberg, 2021). Our analysis found that this model not only reduces costs but also reinforces agency: students must take responsibility to complete online coursework independently (fostering self-regulation skills) and then apply it in real-world contexts during internships (solidifying competence). During the COVID-19 pandemic, ALU’s reliance on asynchronous learning allowed it to pivot more easily to fully online delivery, minimizing disruption compared to many African universities that lacked such infrastructure (Rosenberg, 2021). Students’ familiarity with online tools and self-directed study may also give them an edge in digital literacy over peers from traditional programs. However, the hybrid model is not without challenges. A critical insight from complexity theory is that not all students thrive in a less structured environment – those from very under-resourced educational backgrounds might initially struggle with self-direction. ALU addresses this through a first-year “Leadership Core” program which explicitly teaches learning-to-learn skills, teamwork, critical thinking and project management (Rosenberg, 2021). This core, which replaces the usual smorgasbord of introductory courses, ensures every student gains a baseline of soft skills and the habit of reflection (students maintain a personal “portfolio” documenting their growth). By the end of first year, most students are comfortable navigating the freedom ALU offers. Faculty serve more as coaches than lecturers, another shift that was noted to “flatten” the hierarchy and encourage students to speak up – a meaningful change in contexts where deference to authority is common. A Rwandan student quoted in one case study said, “At ALU I learned to question and to lead my own projects; before, I was afraid to even approach professors” (personal communication, via ALU blog, 2019). Such testimonies highlight increased self-efficacy and confidence, hallmarks of enhanced agency.

4.1.3. Leadership and Agency Outcomes

We assess student agency outcomes through proxies like student initiative, leadership roles on campus, and the nature of student projects. According to ALU’s records, over 1800 student-led projects or ventures were launched during 2017–2024 (this includes campus initiatives, community service projects, and start-up ideas incubated while students are still in school) (ALU, n.d.). Over 400 internships per year have been secured, many by students contacting organizations themselves (ALU, n.d.). Notably, 70–90% of ALU students reportedly secure a job offer or paid internship before graduation (as mentioned in a 2022 ALU promotional video) (Swaniker, 2025). While that statistic likely reflects strong career services and employer partnerships, it also indicates students’ proactiveness. In traditional universities, career support is minimal and students often wait passively until after graduation. The ALU cohort, in contrast, engages with real employers early and frequently. ALU’s CEO, V. Sunassee, attributes this to the mission-driven mindset: “You’ve turned challenges into opportunities, and that’s the ALU spirit” (Alu, 2025). We interpret this as evidence that ALU’s pedagogy inculcates an entrepreneurial agency – students see problems as something they can solve (either via a new venture or initiative), rather than as external conditions they are subject to. This reflects a broader shift from education as consumption to education as creation of value. Scale effects are visible even before graduation: 341+ student-led ventures were under development in 2024 (up from 46 in 2023), with $1.41M raised by student entrepreneurs in 2024—evidence of ‘learning-to-impact’ pathways while still in school.

The theoretical interplay is worth noting. MDLT emphasizes the importance of mission alignment and calling, including a moral or spiritual dimension of education (educating “ethical, entrepreneurial leaders” is ALU’s mission) (ALU, 2025). We found that ALU’s curriculum includes reflective modules on values and leadership ethics, and many students frame their missions in terms of serving others (community, nation, Africa). This resonates with African philosophies of education like Ubuntu (humanity toward others) and contextualizes student agency not as individualistic ambition but as communal responsibility. Larey (2023) argues that African-student agency aligns with “interconnectedness, communal values of support and guidance” (Larey, 2023) – ALU’s peer-driven culture seems to embody that. For example, students often work in multi-country teams tackling a challenge in one of their home communities, learning to value each other’s local knowledge. This communal agency might be one reason female students thrive equally or more at ALU; the alumni data show gender parity in outcomes (female graduates actually had a slightly higher 6-month placement rate and were equally likely to found ventures) (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). ALU’s supportive environment could be leveling gender biases that often limit women’s agency in traditional settings.

In summary, ALU’s mission-driven, hybrid pedagogy has substantively redefined the student experience. It empowers students as agents of their own learning, evidenced by high engagement, numerous student-led initiatives, and a culture of purpose. Philosophically, this affirms MDLT’s premise that education oriented toward a transcendent goal (mission) can yield not only competent graduates but purposeful young leaders. The challenge ahead is determining how (and if) this model’s elements can be adopted or adapted by broader higher education in Africa, a point we consider alongside the hard outcome data in the next section.

4.2. Graduate Outcomes and Impact of ALU Alumni (2017–2025)

We now turn to RQ2, analyzing what ALU graduates have done post-graduation and how that compares with peers. The quantitative outcomes for ALU’s first decade of graduates are striking.

Table 1 summarizes key metrics, contrasting ALU with available regional benchmarks:

Table 1.

Selected Graduate Outcome Metrics – ALU vs. African Benchmarks (circa 2024).

Table 1.

Selected Graduate Outcome Metrics – ALU vs. African Benchmarks (circa 2024).

| Outcome Metric |

ALU Graduates |

Regional Benchmark |

| 6-month post-graduation employment |

75% employed (incl. jobs & internships) (Sangwa & Murung, 2025) |

~65% employed (continental median) (Sangwa & Murung, 2025) |

| Further study (postgrad enrollment) |

15% pursue further studies (ALU, 2025) (e.g. masters) |

~7–10% (est., African grads, 2018) (varies by country) (WATHI, 2021; Gangwar & Malee Bassett, 2020) |

| Founded own venture (entrepreneur) |

25–33% launched a venture (Sangwa & Murung, 2025; ALU, 2025) |

~5% (est. youth entrepreneurship rate) (GEM data, 2020)

|

| Jobs created by students and alumni ventures |

≈52,000 jobs (121 jobs per founder) (ALU, 2025) |

N/A (Avg. ~18 jobs/startup in Africa) (Sangwa & Murung, 2025) |

| Employed in Africa (brain retention) |

95% (in 2021) and 89% (in 2024) of job placements in Africa (Rosenberg, 2021; ALU, 2025) |

~80% of African grads remain in-country (varies; many emigrate) (Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny et al., 2023) |

| Female graduate employment rate |

78% (estimated; slightly > male) (Sangwa & Murung, 2025) |

~Educated women often 5–10% lower employment than men (varies) (Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny et al., 2023; Larey, 2023). |

Several findings emerge from these comparisons:

(i). Employability: ALU graduates experience high and rapid employment. 75% employed within 6 months is well above typical rates. By one year out, over 79% have entered wage employment at any point since graduation (ALU, 2025). This is notable given many African countries struggle with graduate unemployment rates of 30% or higher one year after graduation (e.g. Nigeria, South Africa). The data suggests ALU grads often secure opportunities quickly – indeed many, as noted, before finishing their degrees. The consistency of this outcome over multiple cohorts (2017–2022) adds confidence that it’s a program effect, not a one-off fluke. Reviewers might ask: is this just because ALU selects top students? Selection surely plays a role – ALU’s admissions accept only a fraction of applicants. However, many African public universities also have competitive entry yet still see high graduate unemployment, implying something different is happening at ALU. The mission-driven training and career support likely make ALU graduates more job-ready and proactive in job search. Employers may view ALU grads as having better soft skills; anecdotal evidence from companies like Bain and Facebook (which have hired ALU alumni) indicates they value the leadership and problem-solving mindset (Rosenberg, 2021). Furthermore, ALU’s curriculum requiring internships means virtually every graduate has real work experience, a strong advantage in the job market (Rosenberg, 2021). In essence, ALU seems to be narrowing the education-to-employment gap that plagues the region. Wage signals corroborate this: the 2024 alumni panel reports an average starting salary of $10,473, approximately 5× the four-country graduate baseline of $2,186 (Rwanda, Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia.

(ii). Entrepreneurship and Job Creation: A standout finding is the very high rate of entrepreneurship. Notably, this student pipeline into venture-building carries through to alumni outcomes, where roughly one-third report founding a venture post-graduation. According to ALU’s records, about 1 in 3 graduates has started some form of venture (for-profit or non-profit) (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). Even using the more conservative ALU Impact Report figure of 25% (ALU, 2025), this vastly exceeds typical entrepreneurship rates among university graduates globally. It suggests ALU is realizing its mission of producing not just job seekers but job creators. Combined, ALU’s Entrepreneurship Lab (E-LAB) enabled the launch of over 341 ventures by students in 2024 alone, adding to the 216 alumni entrepreneurs in the same year (ALU, 2025). These ventures range from tech startups and consulting firms to social enterprises in agriculture and education. What’s truly impressive is their reported downstream impact: over 48,000 jobs created by alumni ventures and another ~4,317 by student ventures still in incubation (ALU, 2025). This is associated with the “121:1 job multiplier” mentioned earlier – each ALU entrepreneur is on average employing 121 others (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). As of 2024, alumni entrepreneurs number 216, diversified across top industries including Tech & Communications (51), Farming/Animals/Wildlife (37), Fashion & Creative Economy (26), Advertising/Arts & Media (26), and Education & Training (25)—a pattern consistent with complexity-theory expectations of plural, emergent impact rather than single-sector concentration. Even if this figure is skewed by a few high-growth companies, it is extraordinary. For context, outside studies indicate a typical small business in Africa might employ under 20 people beyond the founder (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). ALU’s focus on scalable solutions (many ventures are in technology, renewable energy, etc.) may contribute to higher growth. Also, ALU likely instills networking and pitching skills (through its entrepreneurial leadership program) such that graduates secure funding more effectively – alumni ventures have raised over 15,122,972 USD in capital collectively (ALU, 2025). This entrepreneurial success addresses a critical need in Africa: creating employment for the continent’s massive youth cohort. Fred Swaniker, ALU’s founder, has said “we can create 100 million jobs in Africa by exporting talent” and training entrepreneurs (Ben Yedder, 2024). ALU alumni might be spearheading that vision, as many build companies that employ others locally.

(iii). Further Education and Global Pathways: Interestingly, 15% of ALU grads pursue postgraduate studies (ALU, 2025) – often at prestigious universities abroad (Cambridge, LSE, etc. have admitted ALU alumni) (Rosenberg, 2021). This indicates ALU’s undergraduate program provides adequate academic grounding for those who choose the academic route. It also counters any criticism that an unorthodox curriculum might handicap students in further academic pursuits. However, ALU’s emphasis is clearly on immediate leadership impact in Africa: importantly, 89% of alumni job placements are in Africa as of December 2024 (ALU, 2025). Unlike many African graduates who emigrate due to lack of opportunities (brain drain), ALU alumni largely stay on the continent, aligning with the university’s mission to catalyze African development. This statistic (89%) is exceptionally high; by contrast, in a country like Ghana a significant fraction of top graduates seek work or study abroad. ALU’s network and Pan-African ethos seem to encourage grads to see opportunity at home. Also, because ALU itself is Pan-African (students form networks across countries), an ALU graduate in, say, Uganda can leverage connections with classmates in Nigeria or Rwanda to find opportunities across the continent, reducing the incentive to leave Africa entirely.

(iv). Leadership and Civic Impact: While harder to quantify, evidence suggests ALU alumni are stepping into leadership roles. Within 5–8 years of graduation (the oldest alumni cohort), a number have founded notable organizations or risen in management. For example, an ALU alumna from the inaugural class is now a program director in a pan-African NGO at age 28 (hypothetical example for illustration). The alumni dataset indicated that female graduates slightly outperformed males in leadership attainment, perhaps measured by percentage in supervisory roles (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). This points to ALU contributing to gender equity in leadership. We can link this to ALU’s learning model which emphasizes confidence, public speaking, and project leadership equally for all students. On a community impact level, many alumni ventures explicitly tackle social problems (education access, clean energy, etc.), thus multiplying ALU’s impact beyond individual success. The ripple effect is palpable: each ALU graduate potentially influences dozens of others through the jobs they create or the community projects they lead, embodying the model of the university as an agent of transformation rather than just knowledge transmission (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025).

Discussion of Causality and Comparisons: The positive outcomes beg the question – is ALU’s model causing them, or would these individuals have succeeded regardless? We consider several points. First, ALU’s admissions process identifies high-potential youth, but so do other top universities; the difference is that ALU’s graduates have a much higher entrepreneurship rate and tendency to work in Africa than, say, graduates of the University of Cape Town or Makerere University. This suggests ALU’s unique curriculum and culture play a role in shaping graduates’ choices and preparedness. Second, ALU provides career resources (e.g. an employer network, entrepreneurship incubation) not commonly available elsewhere, which directly facilitate these outcomes. For example, ALU’s in-house venture incubator (the ALU Entrepreneurship Center) has seeded dozens of student startups, something few traditional universities offer. Third, the alignment of training to real African challenges likely makes graduates more relevant to employers. As one CEO put it, “ALU grads understand the local market and have proven they can solve problems – we don’t need to train that mindset” (paraphrased from an employer interview in an ALU newsletter, 2021). This relevance reflects what policymakers have been urging – tying education to skills for development (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025).

Nonetheless, we must be careful in attribution. We did not have a controlled experiment. It’s possible that some contextual advantages benefited ALU graduates: for instance, Rwanda (where a large portion of ALU students studied) had a growing economy and is relatively stable, which might have eased job placement. If ALU students were mostly in countries with weaker economies, outcomes might differ. Also, ALU being English-medium and internationally networked gives its graduates access to multinational employers and global remote work opportunities (some alumni work remotely for US/EU companies, earning high salaries) (Ben Yedder, 2024). These factors are not solely due to pedagogy but also positioning. However, they are part and parcel of ALU’s model (which consciously positions itself as Pan-African and globally connected). Therefore, one could argue ALU’s model includes creating those networks and opportunities as a core element – which is replicable by other institutions if they adopt a similar outward-facing approach.

Complexity & Ethical Reflections: Complexity theory reminds us that scaling ALU’s success depends on system conditions. We see that in some countries, regulatory barriers could stifle an ALU-like model. For example, Nigeria’s accreditation rules require 70% curriculum overlap with standard programs (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025), which would make “missions not majors” hard to implement. Our findings thus support calls for policy innovation such as “accreditation sandboxes” – experimental licenses for universities to try new models without full regulatory conformity (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). Sangwa & Murungu (2025) proposed nested solutions: continental recognition of innovative programs, national flexibility windows, etc. The strong graduate outcomes from ALU can be persuasive evidence for policymakers to allow more such experiments. Ethically, if mission-driven education is associated with better outcomes, there is an imperative to not keep it only for the elite. ALU is private and charges tuition (albeit lower than many Western universities, it’s still high for many Africans). They do offer scholarships (Mastercard Foundation partners, etc.), but the model needs adaptation to public sector or mass education to truly benefit the millions of students in regular universities. One scenario is public universities adopting elements – e.g. implementing a “mission project” track within degrees or restructuring first-year experience to be more like ALU’s Leadership Core. Our data suggests even incremental changes (like requiring internships or projects) could improve employability. For instance, a World Bank study found that African graduates with internship experience had significantly higher odds of employment (UNESCO, 2024). ALU essentially mandates that for all.

We should consider long-term impact as well: our evaluation goes up to ~5–7 years post-graduation for earliest cohorts. Do ALU alumni continue on upward trajectories? Early signs are yes – the strong foundation likely leads to continued learning and adaptability (some alumni pivot careers or pursue further education successfully). However, we don’t yet know if they will ascend to the highest leadership echelons (CEO, government ministers, etc.) – that may be another decade away. The true test of ALU’s mission to create Africa’s next leaders will be seen in the 2030s when alumni are mid-career. So far, trajectories look promising, but continued research should track indicators like civic leadership (are alumni involved in policy, NGOs, community leadership?) and influence in their sectors.

Limitations – RQ2: We reiterate some limitations in our outcome data. The benchmark data for African graduates is sparse; we relied on patchy stats and inferences. For example, the continental 65% placement is a useful benchmark but African countries vary widely (in some fragile states, graduate unemployment can be 50%+; in others like Kenya maybe 20%). We focused on broad comparisons. Also, ALU’s small scale (1,741 alumni) means even one cohort’s success or struggles can swing percentages. We handled this by aggregating across years. Another consideration is survivor bias: those alumni who remain engaged and report back might be the successful ones, while some struggling graduates might be “silent.” ALU claimed a 90% knowledge of outcomes which is quite high, but if any bias, it likely inflates positive outcomes slightly. Still, even a conservative reading shows outcomes far above average. Where students invoke explicitly Christian vocation language, advisors should foster discernment rather than presumption (Rom 12:2), integrating prayer and counsel without coercion and honoring pluralism in public settings. Practically, this means facilitating values-clarification for all while allowing faith-anchored students to articulate how their mission aligns with God’s will and gifts (Rom 12:2).

To connect back to theoretical framing: the outcomes strongly endorse the synergy of MDLT and SDT. ALU grads with a clear mission (purpose) and the competence to pursue it are demonstrating contributions (impact) that validate the MDLT hypothesis that mission clarity + competence leads to greater long-term contribution (Sangwa & Mutabazi, 2025). They also embody SDT’s ideal of people who are autonomous, skilled, and related to their community, resulting in high performance and well-being. Philosophically, ALU’s success challenges the prevalent mindset that African universities must “mimic” Euro-American models. Instead, it presents an example of an indigenous innovation – one that aligns with both African development goals and cutting-edge educational theory. This raises a profound question posed by our sources: Will African higher education remain an instrument of colonial mimicry or become an agent of mission-oriented transformation? (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). Our findings provide evidence leaning toward the latter: transformation is not only possible, it may already be happening at institutions like ALU. The choice, ultimately, lies with policymakers, educators, and society in scaling these insights.