1. Introduction

In the settings of the rapid expansion of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC), user-generated content (UGC) has shifted from a peripheral aid to a central driver of consumer–brand relationships[1-3]. Unlike offline settings, CBEC inherently lacks tangible product and service touchpoints. As a result, consumers’ brand cognition, emotion, and behavior increasingly hinge on continuously emerging multi-modal UGC—texts, images, videos, and audio[4-6]. Technological advances not only enhance the accessibility and timeliness of information but also, through immersive virtual interaction, strengthen consumers’ sense of presence and contextual imagination[

7,

8]. Even in “look-but-cannot-touch” environments, consumers can experience “as-if in-store” encounters[

9,

10]. This reality invites a fundamental question: how does high-quality UGC, in the absence of physical interaction, shape perception and participation and ultimately translate into differences in brand involvement (BI)?

Existing theories of experiential marketing and online consumer behavior illuminate the “experience–cognition–behavior” chain[

11], yet two gaps remain. First, traditional experiential frameworks prioritize offline multi-sensory cues and do not fully explain how, in digital media, consumers transform “imagination-simulation-empathy” into actionable brand judgments[12-14]. Second, although social presence is known to improve interaction quality and communication effectiveness, the mechanism through which “the quality of interaction itself” acts via presence to influence BI is still fragmented [

15]. In other words, a unified framework is needed to account simultaneously for “sensory-embodied phenomena” and “social-presence experiences,” reflecting UGC’s dual role in CBEC as both an information carrier and an interaction medium [16-18].

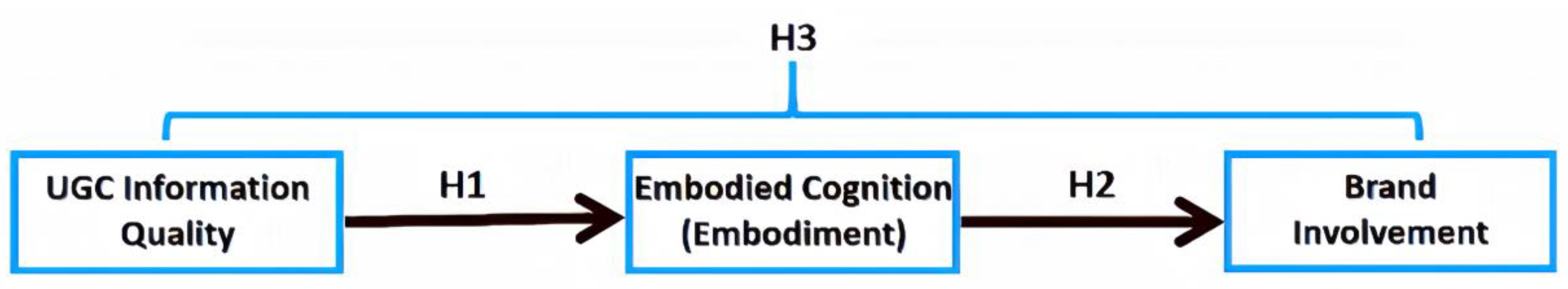

Drawing on embodied cognition and social presence, this study proposes and tests a dual-path, dual-mediator conceptual model. On one path, UGC information quality (credibility, timeliness, and content richness) evokes consumers’ sensory imagination and situational simulation, thereby elevating embodied cognition and strengthening cognitive-affective-behavioral bonds with the brand[

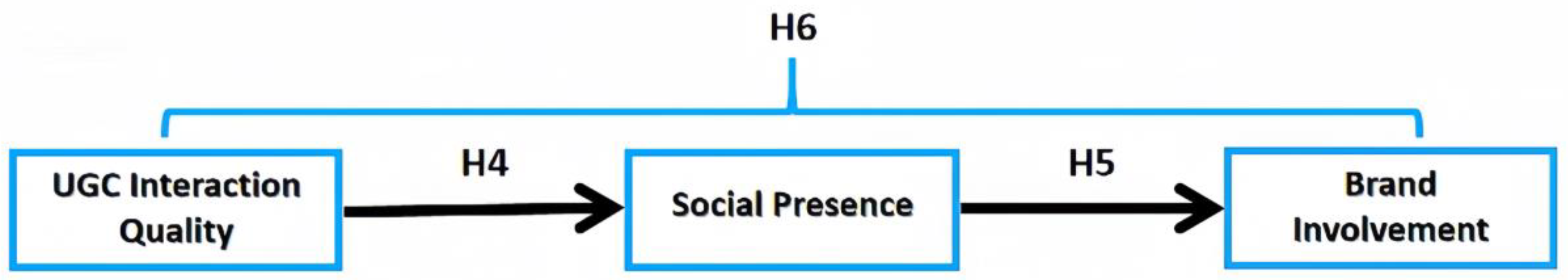

19]. On the other path, UGC interaction quality (responsiveness, feedback, and cue variety) enhances social presence, fostering social bonds among consumers, brands, and community members, which in turn intensifies BI [

20]. Accordingly, we advance two clusters of hypotheses: H1–H3 address a partial-mediation pathway from information quality to BI via embodied cognition; H4–H6 address a full-mediation pathway from interaction quality to BI via social presence. We control for individual and contextual factors (e.g., gender, age, education, and brand country of origin) to ensure robust estimates.

This study’s contributions are threefold. First, at the mechanism level, rather than treating UGC as a monolithic input, we decompose it into “information quality” and “interaction quality,” pairing them with an “embodied-experience path” and a “social-presence path,” respectively. This explains how UGC, as both “static readable content” and “dynamic interactive process,” jointly shapes BI[

21]. Second, at the theory-integration level, we synthesize two streams—embodied cognition (sensory experience) and social presence (social interaction)—within the CBEC context, addressing how “missing physical cues” online are compensated by psychological and social mechanisms[

22]. Third, at the methodological level, using a two-phase survey and multiple statistical tests (reliability/validity, correlations and regressions, hierarchical mediation, and robustness checks), we corroborate the coexistence of partial and full mediation, reinforcing UGC’s indirect effects on BI along both paths [

23].

We focus on three research questions: (1) Can high-quality informational attributes of UGC increase BI via embodied cognition? (2) Can high-quality interactive attributes of UGC increase BI via social presence? (3) Do these two paths differ systematically as partial versus full mediation? In addressing these questions, we delineate the “UGC-experience/presence-involvement” chain and offer actionable guidance for brand management in CBEC: optimize “credible–timely–rich” informational supply on the content side, and design “multi-cue–high-responsiveness–strong-feedback” social mechanisms on the interaction side to activate both “embodied sensation” and “social presence.”

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 presents the hypotheses and conceptual model.

Section 3 details the sample and data.

Section 4 introduces the measures and empirical procedures.

Section 5 reports the results and robustness analyses.

Section 6 discusses the two mediation paths and their implications.

Section 7 concludes with theoretical and managerial implications and outlines directions for future research.

7. Summary and Implications

7.1. Conclusion

This study investigated how intelligent digitalization and immersive experience in CBEC settings translate UGC into CBI through two theoretically grounded pathways. Anchored in embodied cognition and social presence, we specified and tested a dual-path, dual-mediator model in which UGC information quality enhances BI via embodied cognition (partial mediation), while UGC interaction quality enhances BI via social presence (full mediation). Across reliability/validity assessments, hierarchical regressions, mediation tests, and robustness analyses, all six hypotheses (H1–H6) received consistent empirical support. Together, the results depict UGC not as a monolithic input but as a two-faceted mechanism, “static readable content” and “dynamic interactive process”, that constructs BI through complementary experiential and social routes, thereby laying a psychological foundation for downstream brand attachment formation in CBEC environments.

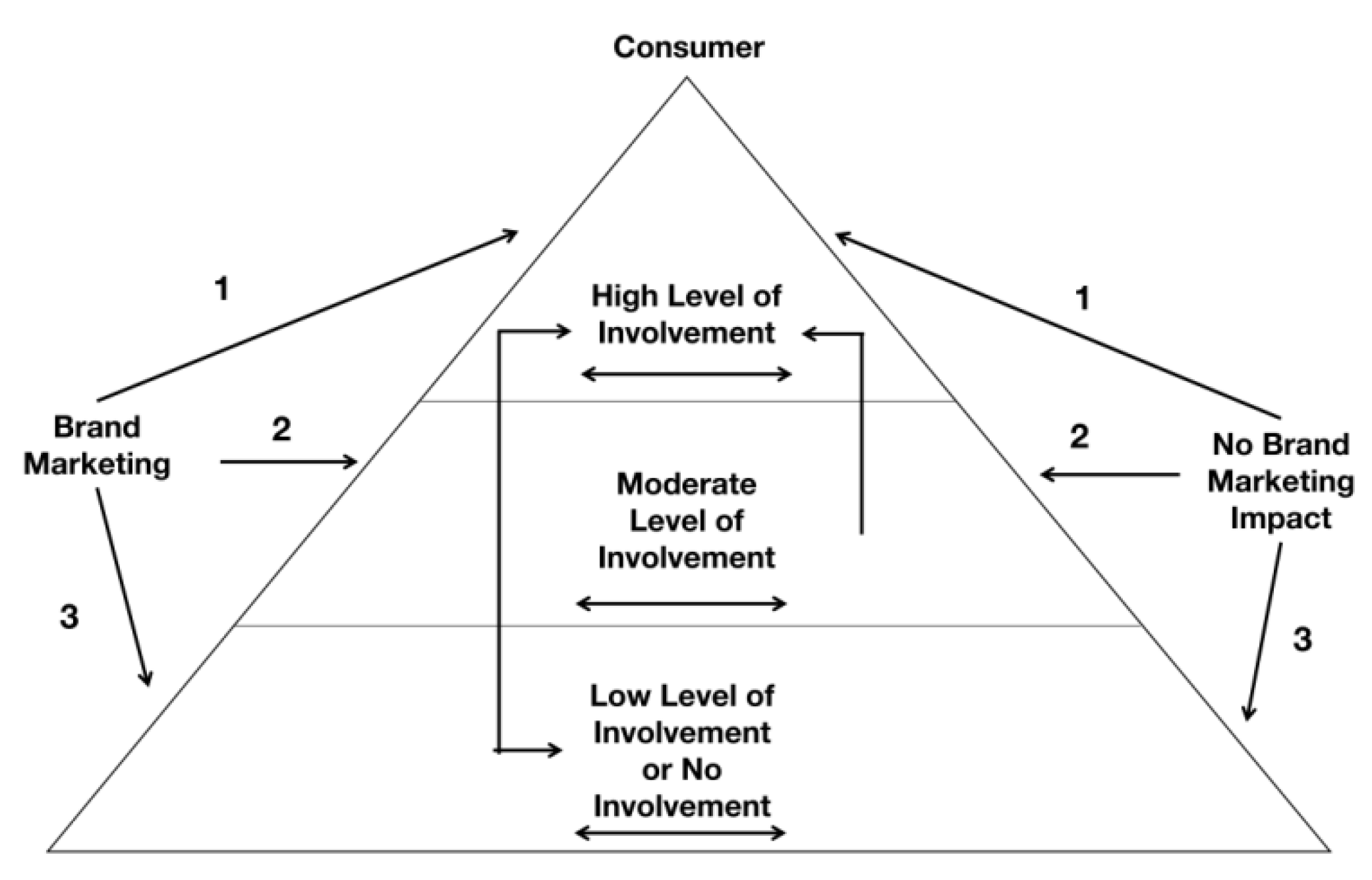

In sum, the study advances a coherent account of how UGC orchestrates immersive experience and social connectedness to construct brand involvement in CBEC. By demonstrating a partial mediation via embodied cognition and a full mediation via social presence, it clarifies when and how “information” and “interaction” work, jointly and differentially, to propel consumers up the involvement ladder, offering a scalable blueprint for designing digital ecosystems that transform attention into attachment.

7.2. Implications

7.2.1. Theoretical Implications

Following our first work[

3], this study advances theory on consumer-brand relationships in CBEC by positioning UGC as a dual-faceted driver of brand involvement that operates through embodied cognition and social presence[

52].

First, by analytically decomposing UGC into information quality (credible–timely–rich) and interaction quality (responsive–feedback-rich–multi-cue), we move beyond monolithic treatments of UGC and clarify how its static and interactive properties map onto distinct psychological mechanisms. The demonstrated partial mediation from information quality to BI via embodied cognition, and the full mediation from interaction quality to BI via social presence, jointly specify a two-path process architecture that prior experiential accounts in digital settings left underspecified. In doing so, the model re-theorizes UGC not merely as persuasive input, but as a situated stimulus capable of triggering sensorimotor simulation and socio-relational immersion that together scaffold brand-related action tendencies.

Second, integrating embodied cognition into the CBEC literature refines the experience-cognition-behavior chain by showing that, even without physical contact, multimodal cues in high-quality UGC can elicit sensorimotor imagery and contextual simulation, which in turn heighten BI. This extends experiential marketing beyond its offline, multisensory premises to a virtual experiential account in which imagination, perception, and action tendencies are co-produced by the human-media system rather than anchored in material touchpoints. Theoretically, this reframes “presence” in digital commerce as not only a social construct but also an embodied construct, thereby connecting streams of research that have largely progressed in parallel.

Third, articulating social presence as the exclusive mediator between interaction quality and BI sharpens the social-cognitive logic of online engagement. While prior work links richer media and interpersonal cues to improved communication, the present findings specify how interactional affordances (responsiveness, bidirectional feedback, and cue multiplicity) consolidate perceptions of copresence and relational warmth, which then translate into brand-focused cognitive, affective, and behavioral involvement [15,20,33-39]. This mechanism-level clarification elevates social presence from a contextual enhancer to a causal conduit in the UGC→BI pipeline.

Fourth, the model situates BI as a processual bridge between upstream UGC quality and downstream BA, complementing prior frameworks that emphasize direct attitudinal transfer. By demonstrating differentiated mediation structures across the static and interactive pathways, the study explains why content strategies that excel at information delivery may activate involvement through embodied routes yet still benefit from interactional designs that cultivate presence—thereby offering a theoretically cohesive rationale for the joint optimization of content and community in CBEC ecosystems. This layered view aligns BI with its rightful position as a gateway state that channels UGC-derived experiences into durable attachments.

Fifth, the study refines construct boundaries and measurement validity in digital contexts. The high reliability and convergent/discriminant validity of the adapted scales indicate that embodied cognition and social presence can be operationalized with psychometric rigor in CBEC settings while remaining conceptually distinct from BI. This supports their treatment as mediating mechanisms rather than reflective components of involvement, and it encourages future operationalizations that preserve this separation when modeling higher-order brand relationship outcomes.

7.2.2. Practical Implications

This investigation also has practical implications in the era of digitalization. Grounded in the dual-path mediation model, the findings of this study offer actionable insights for CBEC enterprises, policymakers, and CBEC website operators. Each stakeholder occupies a unique position in shaping the informational, technological, and regulatory ecosystems that jointly determine how UGC transforms into embodied and social experiences for consumers.

For CBEC enterprises, the results underscore that UGC is not merely an after-sales byproduct but a strategic resource for brand experience construction. irms can enhance embodied cognition by promoting credible, rich, and sensory UGC, such as unboxing videos, texture displays, and detailed reviews, that help consumers simulate real product use despite spatial distance. Simultaneously, brands should strengthen social presence through interactive spaces like online communities, co-creation campaigns, and live Q&A sessions, which build trust, belonging, and emotional resonance. Integrating both informational and interactive pathways into digital marketing enables firms to transform consumer perception into sustained brand involvement and attachment.

For CBSC website operators, the results highlight their pivotal role as experiential mediators. Platforms should adopt UGC quality governance systems that reward informative, verified, and responsive contributions while curbing misinformation. Interface design should stimulate both sensorimotor immersion (e.g., 3D displays, AR try-ons) and social warmth (e.g., real-time comments, avatars, feedback cues). Algorithmic recommendation should balance informational accuracy and interaction vitality to sustain both embodied and social pathways. By fostering credible information flows and authentic social exchanges, website operators can create immersive, trustworthy digital ecosystems that strengthen consumers’ brand involvement and long-term attachment.

For policymakers, this study underscores the need to build trustworthy and equitable digital environments that support immersive consumer engagement. Governments can introduce authenticity and transparency standards for UGC, such as labeling AI-generated or incentivized content, and establish cross-border data governance frameworks to ensure content traceability and privacy protection. Policies promoting digital literacy help consumers evaluate online information critically and participate responsibly in interactive UGC environments. Moreover, supporting innovation in AR, AI, and virtual experience technologies can help domestic enterprises align with the embodied cognition mechanism that drives consumer trust in global markets.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides a comprehensive exploration of UGC’s dual mediating mechanisms in the CBEC environment, several forward-looking directions emerge for future research:

First, the current model can be extended across industries and cultures to verify its universality and adaptability. Comparative studies involving different product types or international markets could reveal how cultural cognition, product tangibility, or regulatory environments influence the embodied and social presence pathways.

Second, future work could incorporate multimodal and behavioral analytics to enrich theoretical insight. Integrating physiological data (e.g., gaze tracking, emotion recognition) or platform-based behavioral traces would allow scholars to capture embodied and social engagement processes more dynamically and accurately, complementing perception-based findings.

Third, expanding to longitudinal and experimental designs can clarify the causal progression from UGC exposure to brand attachment formation. Future studies may also examine boundary and moderating factors, such as algorithmic personalization, consumer motivation, or technological immersion level, to explore how intelligent digitalization reshapes the interactive experience. Collectively, these research extensions would advance a more predictive and context-sensitive theory of digital embodiment and social presence in CBEC.