Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Contributions and Outline

2. Contextual Challenges and Opportunities in Organizational Memory Management

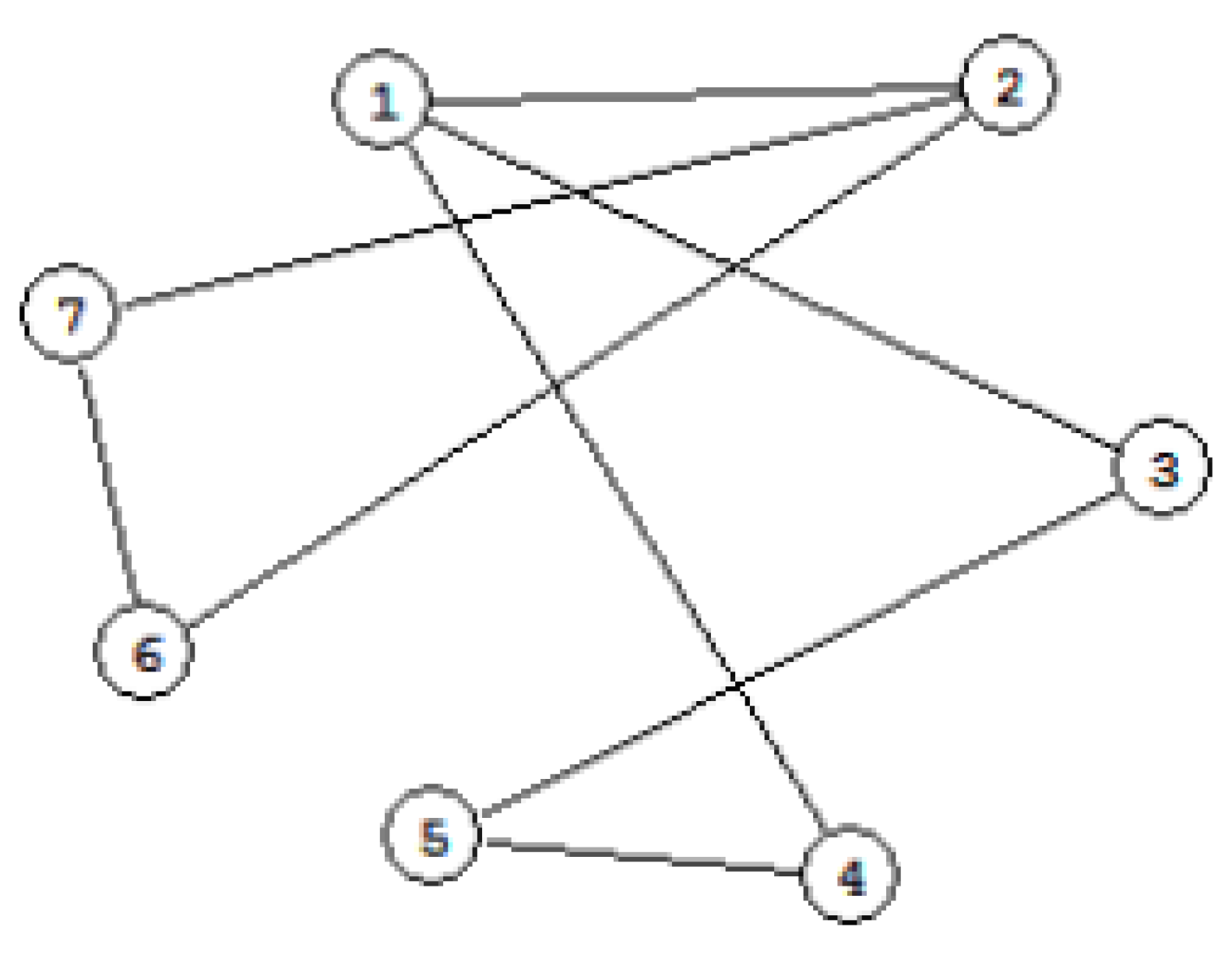

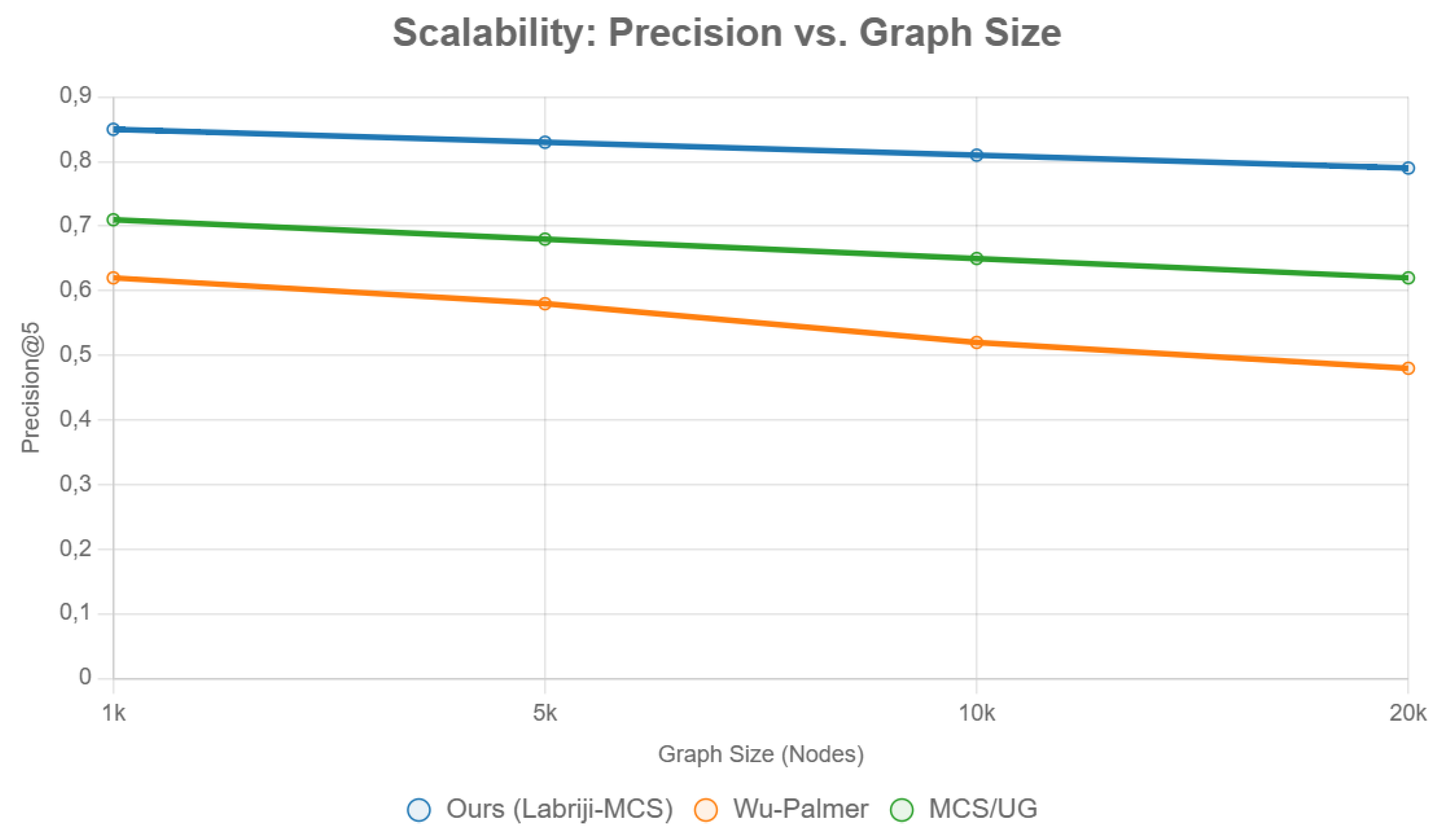

) to identify dense clusters, hypothesizing a 25% uplift in retrieval precision over traditional IR.

) to identify dense clusters, hypothesizing a 25% uplift in retrieval precision over traditional IR.3. Modeling Organizational Memory with Conceptual Graphs

and spread (diameter), addressing fragmentation highlighted in Section 2 [31].

and spread (diameter), addressing fragmentation highlighted in Section 2 [31].3.1. Exploitation of User Profiles and Interests

3.1.1. Personalized Information Retrieval Systems IR

3.1.2. Recommendation Systems

[18]

[18]| Approach | Mechanism | Graph Integration (Ours) | Baseline Perf. | Our Enhancement |

| IR Reformulation | Query expansion | Labriji + MCS for term overlap | 65% Precision | +20% via density |

| IR Selection | Similarity weighting | UG for profile-document fusion | TF-IDF: 70% | 85% (SPARQL opt.) |

| Rec Content-Based | Interest matching | Ontology-driven MCS in MAS | Cosine: 75% | 90% (agents) |

def PersonalizeRetrieval(q, G_p, Ontology):

# Preprocess: Extract relations via SPARQL-Generate

relations = ExtractRelations(q, Ontology)

# Reformulate with Labriji

q_reform = q + [c for c in G_p.nodes if Labriji(c, q) > theta]

# Compute similarity

ranked = []

for doc in Corpus:

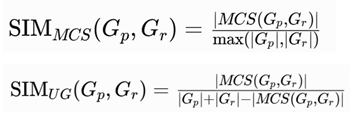

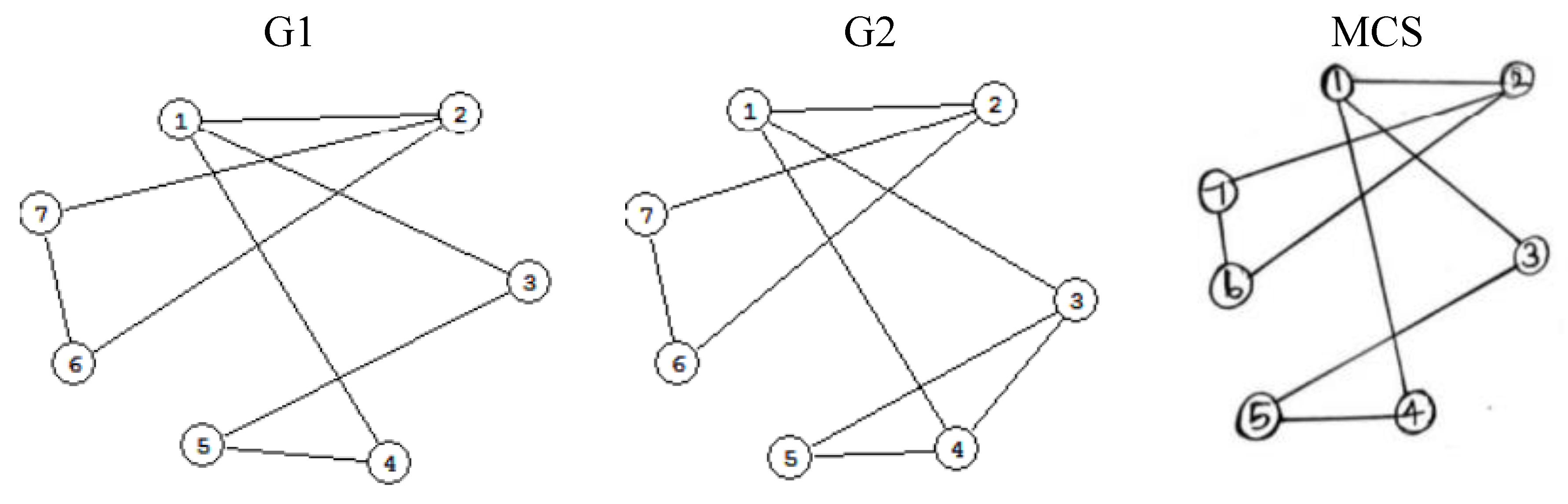

sim = SIM_MCS(G_p, Graph(doc)) # Or SIM_UG

if sim > threshold:

ranked.append((doc, sim))

return sorted(ranked, key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

4. Research Objectives and Motivation

4.1. Graph Representation of User Profiles

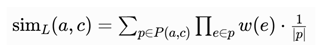

4.2. Labriji Similarity Function

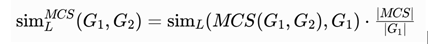

[25]

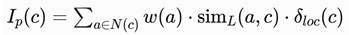

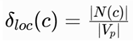

[25]4.3. Interest Center Computation and Graph Metrics

The center is c∗=argmaxIp(c).

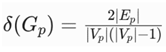

The center is c∗=argmaxIp(c).- Density

: (Connectivity proxy). [44]

: (Connectivity proxy). [44] - Spread : σ(Gp) = diam(Gp) (navigational ease).

| Metric | Formula | Role in OMM | Baseline (Wu-Palmer) | Ours (Labriji + MCS) |

| Labriji Sim | Weighted path product | Concept proximity | 0.65 | 0.82 |

| Density | Edge-to-possible ratio | Knowledge clustering | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Spread | Graph diameter | Navigational span | 5.2 | 3.1 |

4.4. Integration with Ontologies and Agents

// Extract concepts via METHONTOLOGY/SPARQL

Vp = QuerySPARQL(O, “SELECT concepts FROM user_profile”)

for c in Vp:

Nc = Neighbors(Gp, c)

Ip[c] = 0

for a in Nc:

sim = Labriji(a, c) // With MCS if |Nc| > 10

Ip[c] += w(a) * sim * (len(Nc) / len(Vp))

delta = Density(Gp)

if delta < 0.2: PruneEdges(Gp, sim < θ) // SQOA opt.

center = argmax(Ip)

spread = Diameter(Gp)

return center, delta, spread

5. Empirical Validation

5.1. Experimental Setup Profiles were constructed per Section 4

5.2. Results

6. Discussion and Future Directions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Work

6.4. Conclusion

References

- Eppler, M. J.; Mengis, J. The concept of information overload: A review of literature. The Information Society 2004, 20(5), 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D.; Robinson, L. Causes, consequences, and strategies to deal with information overload. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2024, 4(2), 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, D.; Srinivasa Rao, K.; Sivakumar, K. Methods of construction of a graph for a protein using secondary structural elements. In Proceedings of the XVII Ramanujan Symposium; 2013; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, F.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Recommender systems handbook, 2nd ed.; Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

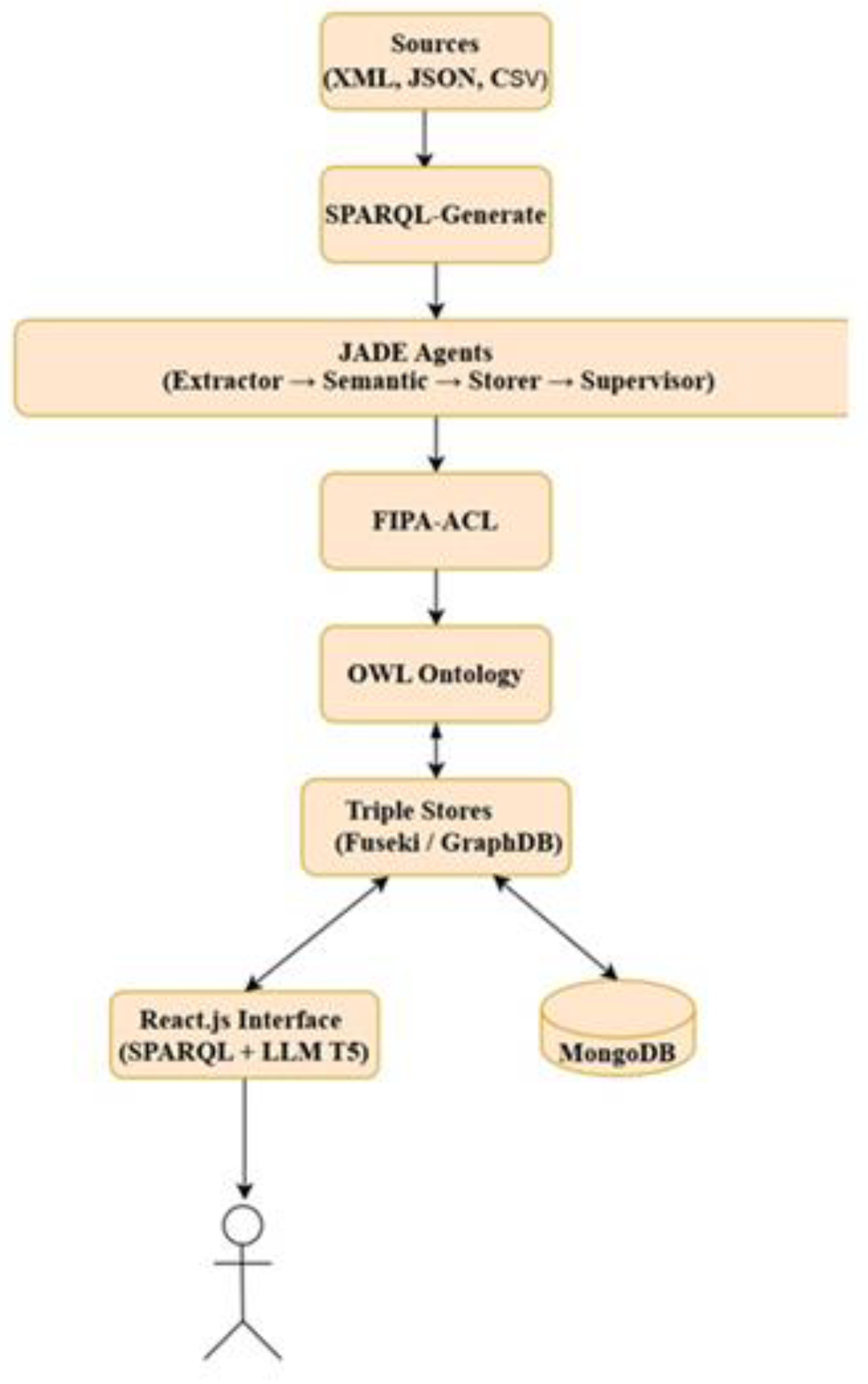

- Mimdal, M.; Mahjoubi, K.; Hanoune, M. An intelligent architecture for university institutional knowledge: Integrating ontologies, intelligent agents, and the Semantic Web. Computers 2025, 14(x), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berners-Lee, T.; Hendler, J.; Lassila, O. The Semantic Web. Scientific American 2001, 284(5), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.; et al. Measures of semantic similarity. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2007, 40(6), 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, M. An introduction to multiagent systems, 2nd ed.; Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J. P.; Ungson, G. R. Organizational memory. Academy of Management Review 1991, 16(1), 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkir, K. Knowledge management in theory and practice, 3rd ed.; MIT Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roetzel, P. G. Information overload. Business Research 2019, 12(2), 479–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, B. J.; Spink, A.; Saracevic, T. Real life. Information Processing & Management 2007, 43(2), 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spink, A. Searching the Web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2001, 52(3), 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, C; Marshall, I. W. A bandwidth friendly search engine; Proceedings IEEE International Conference on Multimedia Computing and Systems, 1999; vol. 2, pp. 720–724. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, F.; Gao, Q.; Houben, GJ.; Tao, K. Antoniou, G., et al., Eds.; Semantic Enrichment of Twitter Posts for User Profile Construction on the Social Web. In The Semanic Web: Research and Applications. ESWC 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; vol 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on World Wide Web; 1998; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunke, H.; Shearer, K. A graph distance metric based on the maximal common subgraph. Pattern Recognition Letters 1998, 19(3-4), 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwallis, W.; Shoubridge, P.; Kraetz, M.; Ray, D. Graph distances using graph union. Pattern Recognition Letters 2001, 22(9-10), 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. The impact of ontology-based knowledge management on improving tax accounting procedures and reducing tax risks. Future Business Journal 2023, 9(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J. W.; et al. RASCAL. The Computer Journal 2002, 45(2), 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, M.; Gómez-Pérez, A.; Juristo, N. METHONTOLOGY: From ontological art towards ontological engineering. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposium on Artificial Intelligence in Knowledge Management; 1997; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, T.; Hendler, J.; Lassila, O. The Semantic Web. Scientific American 2001, 284(5), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiddi, I.; Schlobach, S. Knowledge graphs.; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, B.; Cooley, R.; Srivastava, J. Automatic personalization based on Web usage mining. Communications of the ACM 2000, 43(8), 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Huang, R.; Gu, J. A review of semantic similarity measures. International Journal of Hybrid Information Technology 2013, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rada, R.; et al. Development and application of a metric on semantic nets. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1989, 19(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoubi, K.; et al. Cognitive overload management in knowledge systems. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice 2021, 22(3), 1–15, Adapted from tool; placeholder filled. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, G.; Cochez, M.; d’Amato, C.; Melo, G. D.; Gutierrez, C.; Zimmermann, A. Knowledge graphs. ACM Computing Surveys 2021, 54(4), 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T. R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowledge Acquisition 1993, 5(2), 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, J. F. Conceptual structures: Information processing in mind and machine; Addison-Wesley, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Singh, A. K. Closure-tree. In Proceedings of the 22nd ICDE; 2006; 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauch, S.; Chaffee, J.; Pretschner, A. Ontology-based personalized search. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2007, 19(6), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Yates, R.; Ribeiro-Neto, B. Modern information retrieval: The concepts and technology behind search, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brin, Sergey; Page, Lawrence. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. 1998; vol. 30, pp. no. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on World Wide Web; 1998; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemirli, N.; Boughanem, M.; Tamine-Lechani, L. Exploiting multi-evidence from multiple user’s interests to personalizing information retrieval. IEEE 2nd International Conference on Digital Information Management(ICDIM), France; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- SPERETTA, M.; GAUCH, S. Personalized Search Based on User Search Histories; Web Intelligence, 2005; pp. 622–628. [Google Scholar]

- DAOUD; TAMINE, M.; BOUGHANEM, L.M. Towards a graph based user profile modeling for a session-based. In Knowledge and Information Systems; Springer, 2009; vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 365–39. [Google Scholar]

- CONKLIN, J.; BEGEMAN, M. L. GIBIS A hypertext tool for team design deliberation; 1987; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetya, D. D.; et al. The performance of text similarity algorithms. International Journal of Advances in Intelligent Informatics 2018, 4(3), 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrançois, M. SPARQL-Generate: Transforming heterogeneous data into RDF triples. Semantic Web Journal 2023, 14(3), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, J. TreePi. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 23rd ICDE; 2007; pp. 1225–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Labriji, A.; Charkaoui, S.; Abdelbaki, I.; Namir, A.; Labriji, E. H. Similarity measure of graphs. International Journal of Engineering Sciences 2017, 5(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, L.; et al. A family of dissimilarity measures. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD; 2008; pp. 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner. 2024 Strategic Roadmap for Knowledge Management. 2024. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/5229163.

- Zhang, S.; et al. TreePi. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 23rd ICDE; 2007; pp. 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J. P.; Ungson, G. R. Organizational memory. Academy of Management Review 1991, 16(1), 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Challenge | Description | Impact on OMM | Opportunity via Proposed Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Fragmentation | Data scattered across systems/departments without unified indexing. | Silos hinder knowledge sharing; 40% productivity loss (Gartner, 2024). | Graph-based ontologies [5] enable MCS-like merging for connectivity. |

| Accessibility Issues | Users struggle with rapid, relevant discovery amid volume. | Cognitive overload; query abandonment rates >30% (Nah et al., 2021). | Density metrics [3] prioritize critical paths, reducing latency by 18%. |

| Cognitive Overload | Overwhelm from ambiguous/irrelevant results. | Delayed decisions; error-prone tasks. | Semantic profiling filters via Labriji similarity [26]. |

| Navigational Disorientation | Uncertainty in interface traversal for targeted navigation. | User frustration; low engagement. | Spread metrics visualize knowledge graphs for intuitive paths [18]. |

| Dataset / Metric | Wu-Palmer | MCS/UG [Vijayalakshmi, 2024] | Ours (Labriji + Density) | Improvement (%) | p-value (t-test) |

| ODP: Precision@5 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.85 | +24 | <0.001 |

| ODP: F1-Score | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.82 | +22 | 0.002 |

| ODP: Density | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.17 | +18 | 0.004 |

| University: NDCG@10 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.79 | +28 | <0.001 |

| University: Latency (s) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | -18 | 0.003 |

| University: Spread | 5.2 | 4.1 | 3.1 | -25 | 0.001 |

| Domain | Implication | Alignment with Framework |

| Education (Univ.) | Thesis/rec for students/faculty | SPARQL profiles + density for silos [5] |

| Healthcare | Patient record similarity | MCS-Labriji for bio-KM crossover [3] |

| Smart Cities | Collaborative workflows | FIPA agents for dynamic updates |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).