Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Defining the Scopes

2.2. Retrieving and Cleaning Data

2.3. Selecting Background Points and Environmental Variables

2.4. Constructing Final Species Distribution Models

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

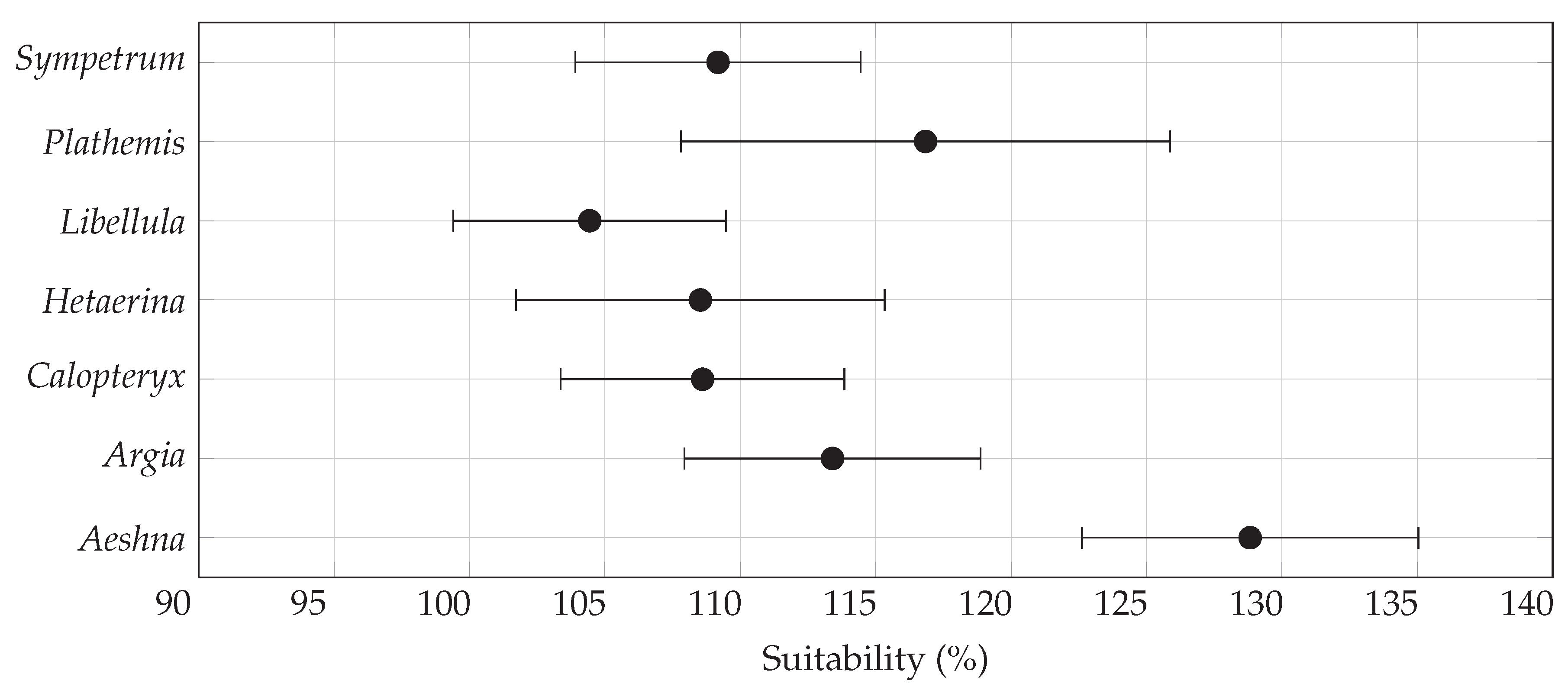

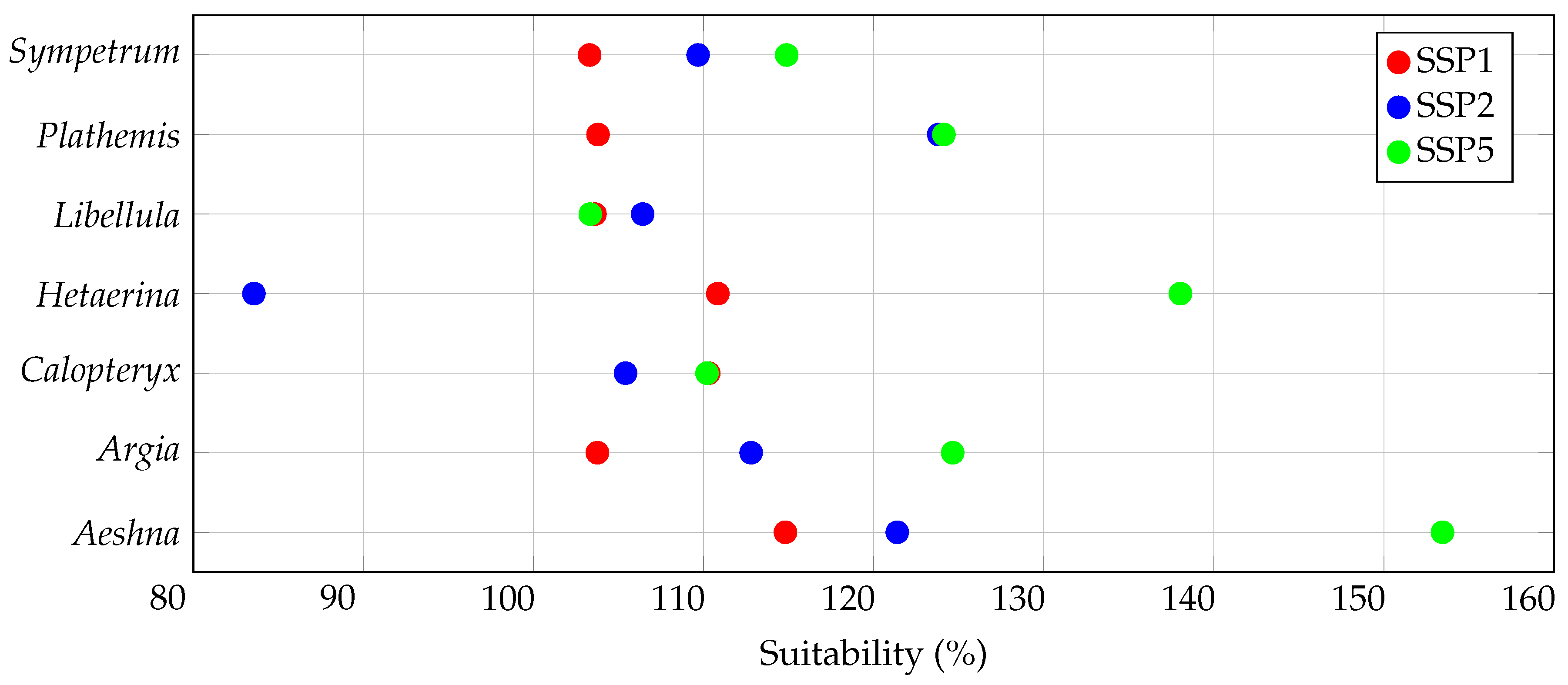

3.1. Overall Habitat Suitability Changes

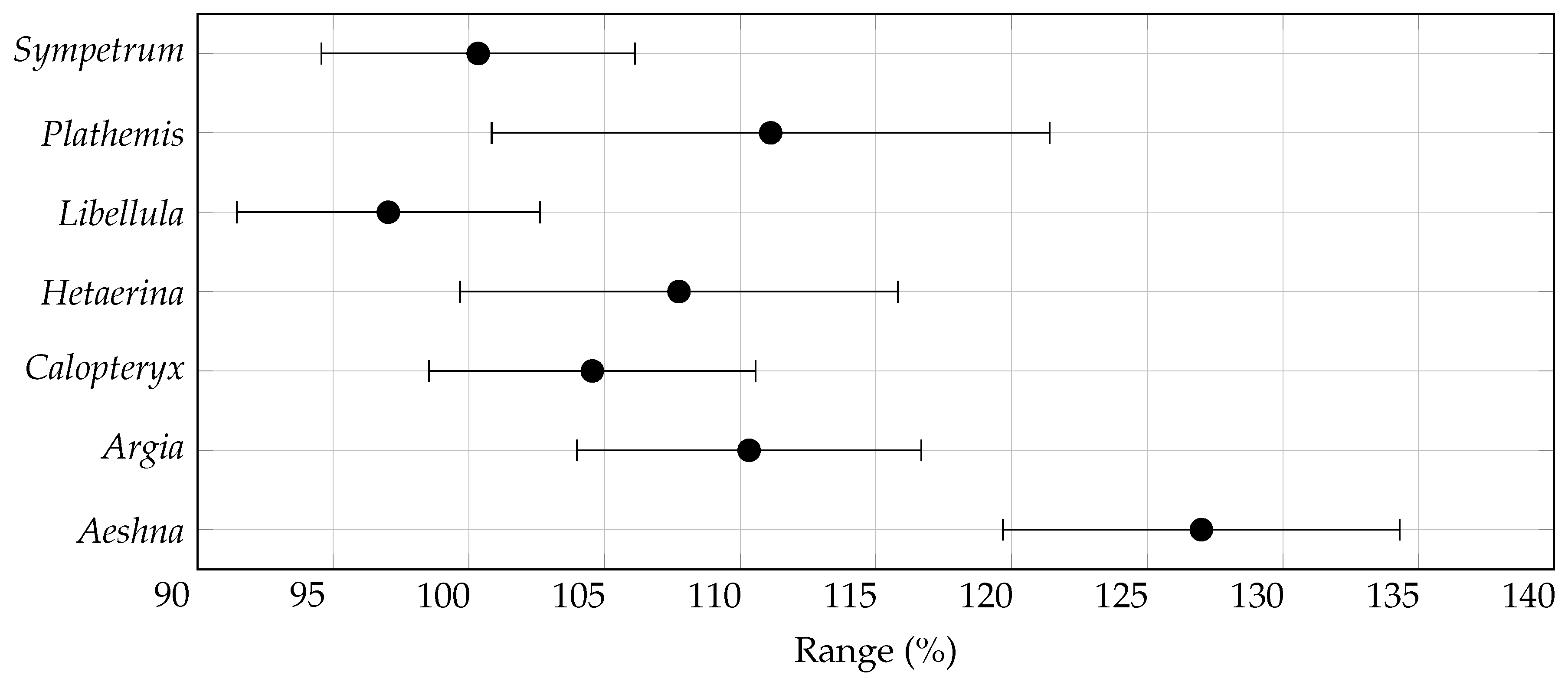

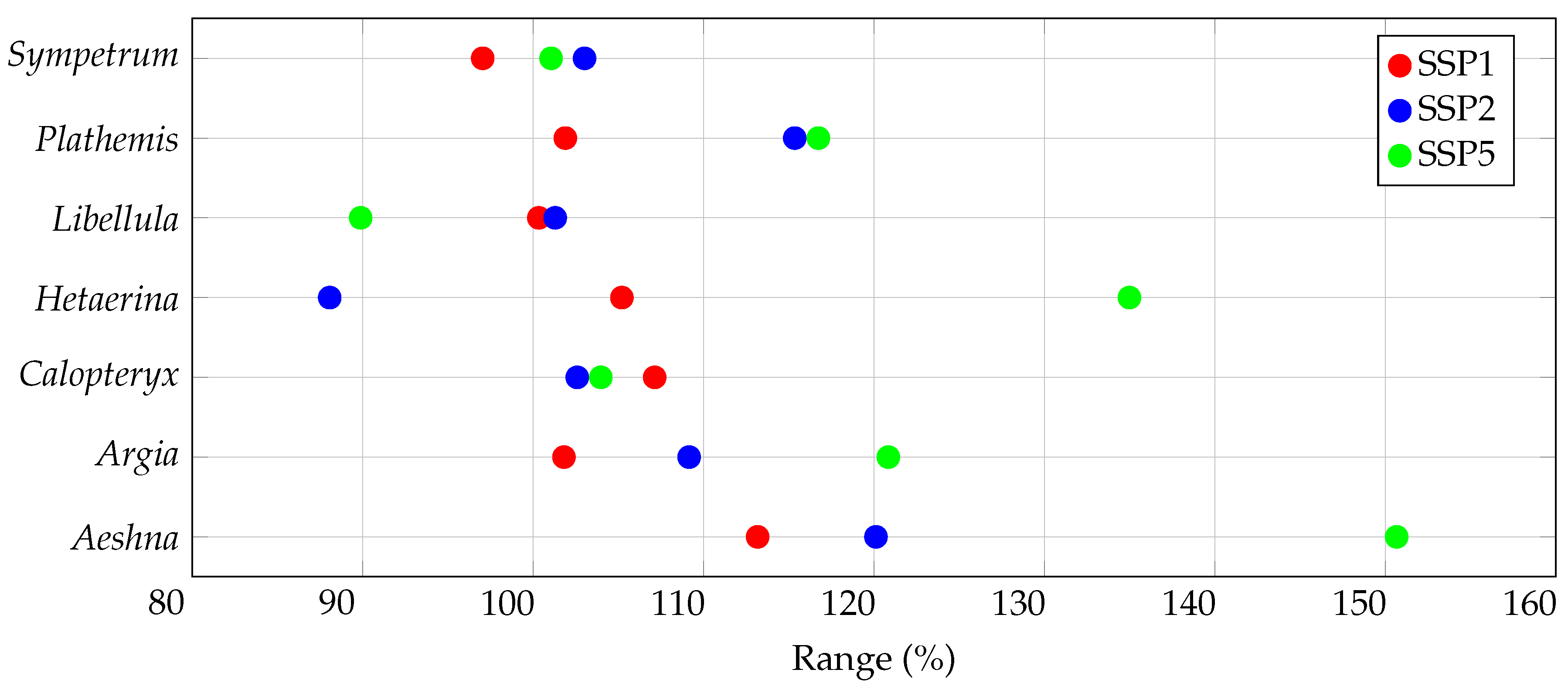

3.2. Range Size Changes

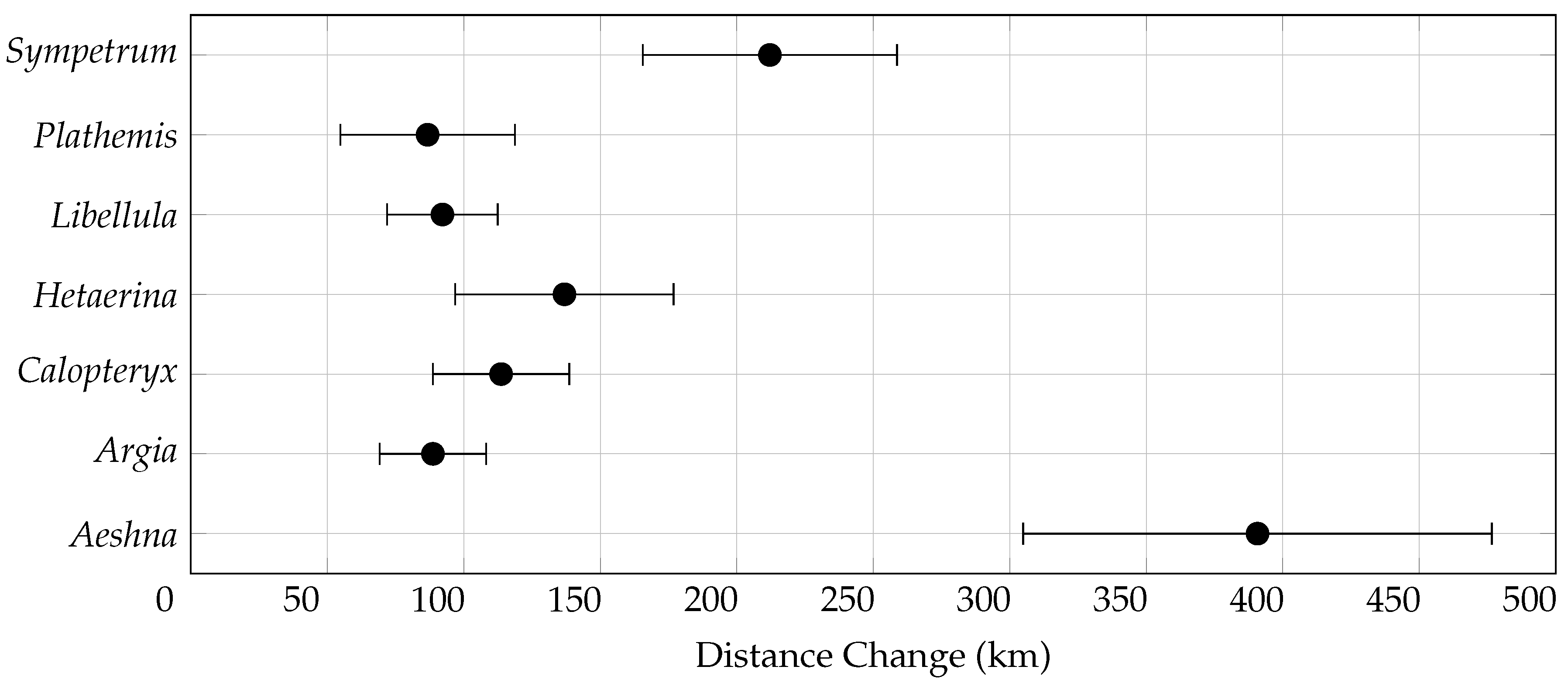

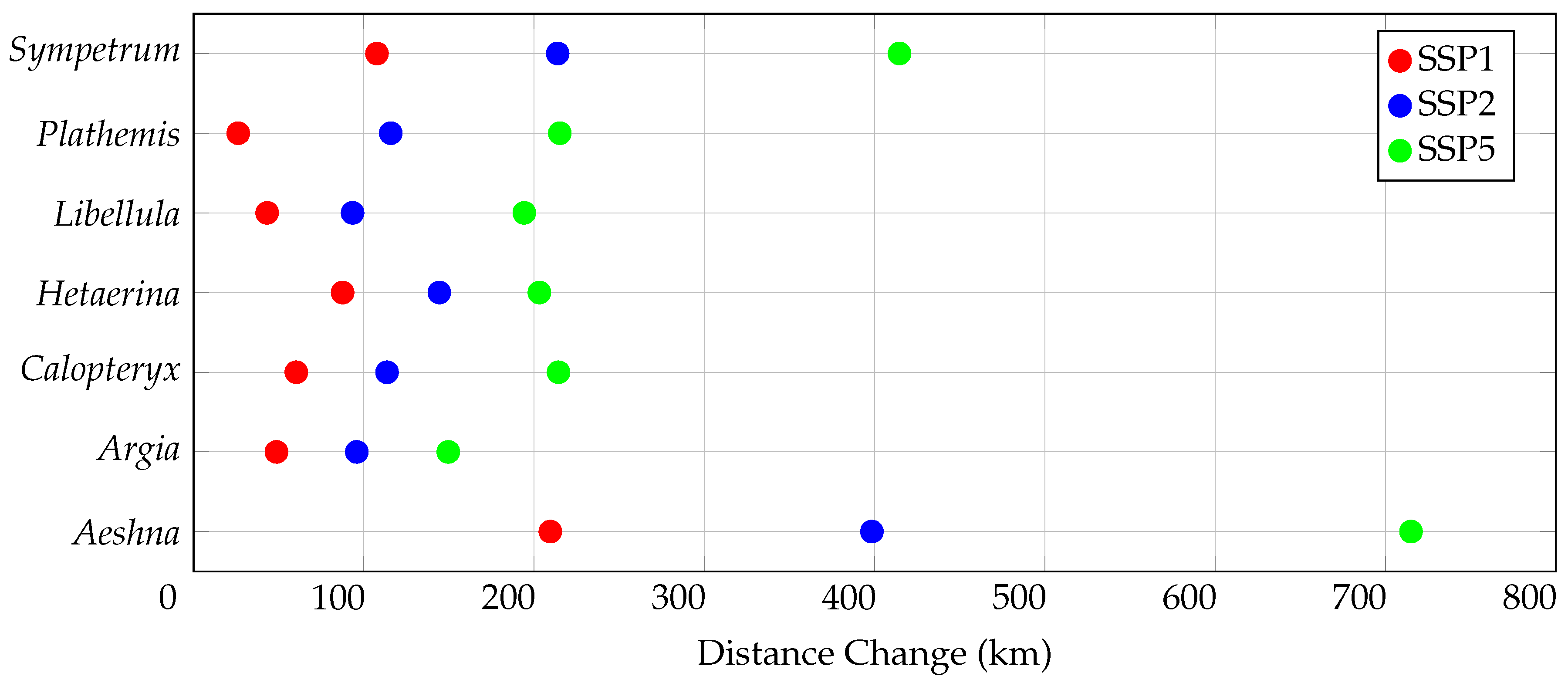

3.3. Centroid Change

| Genus | General Suitability (%) | Range Size (%) | Centroid Distance () | |||

| Aeshna | ||||||

| Argia | ||||||

| Calopteryx | ||||||

| Hetaerina | ||||||

| Libellula | ||||||

| Plathemis | ||||||

| Sympetrum | ||||||

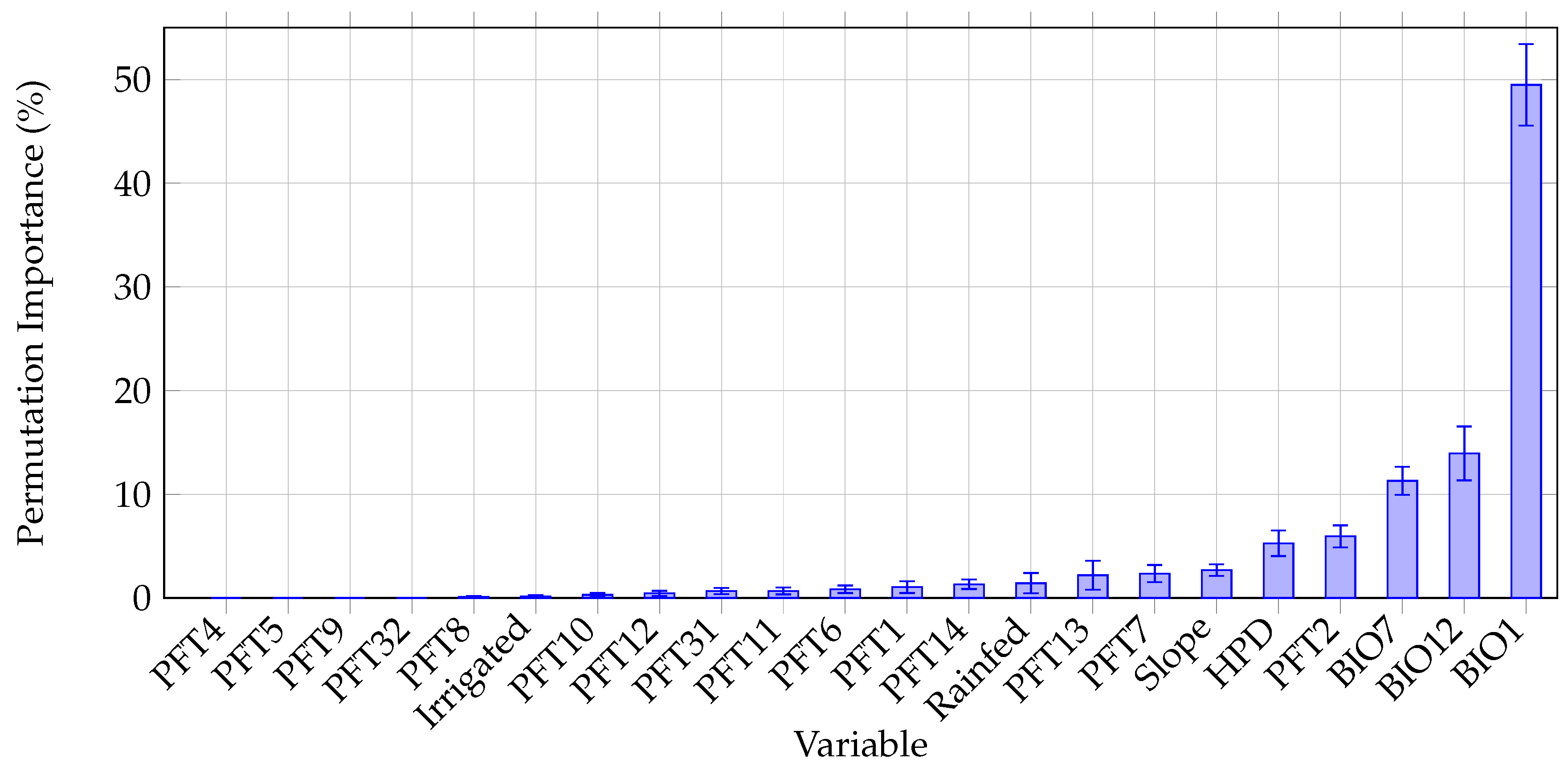

3.4. Environmental Variable Permutation Importance

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis; 2001.

- Pereira, H.M.; Leadley, P.W.; Proença, V.; Alkemade, R.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Fernandez-Manjarrés, J.F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. Scenarios for Global Biodiversity in the 21st Century. Science 2010, 330, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin III, F.S.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; Sala, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.D.; McIntyre, N.E. Modeling the distribution of odonates: a review. Freshwater Science 2015, 34, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Ebi, K.L.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Riahi, K.; Rothman, D.S.; Van Ruijven, B.J.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Birkmann, J.; Kok, K.; et al. The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Riahi, K.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Emmerling, J.; Fujimori, S.; Kc, S.; Kriegler, E.; O’Neill, B. The Shared Socio-economic Pathways: Trajectories for human development and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.T.J.; Kok, K.; Peterson, G.D.; Hill, R.; Agard, J.; Carpenter, S.R. Biodiversity and ecosystem services require IPBES to take novel approach to scenarios. Sustainability Science 2017, 12, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.W.; Denno, R.F.; Eubanks, M.D.; Finke, D.L.; Kaplan, I. Insect Ecology: Behavior, Populations and Communities, 1 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Rose, R.J.; Clarke, R.T.; Thomas, C.D.; Webb, N.R. Intraspecific variation in habitat availability among ectothermic animals near their climatic limits and their centres of range. Functional Ecology 1999, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, C.; Thompson, D.J. The effects of environmental warming on Odonata: a review. International Journal of Odonatology 2008, 11, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caissie, D. The thermal regime of rivers: a review. Freshwater Biology 2006, 51, 1389–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, L.; Thuiller, W.; Lek, S.; Lim, P.; Grenouillet, G. Climate change hastens the turnover of stream fish assemblages. Global Change Biology 2008, 14, 2232–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertli, B.; Joye, D.A.; Castella, E.; Juge, R.; Cambin, D.; Lachavanne, J.B. Does size matter? The relationship between pond area and biodiversity. Biological Conservation 2002, 104, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.L. Odonata: Who They Are and What They Have Done for Us Lately: Classification and Ecosystem Services of Dragonflies. Insects 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, C.A.; Vogt, R.J.; Beisner, B.E. Functional Traits. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, 1 ed.; Wiley, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, M.W.; Carscadden, K.; Mirotchnick, N. Beyond species: functional diversity and the maintenance of ecological processes and services. Journal of Applied Ecology 2011, 48, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, D.; Leclerc, C.; Colleu, M.; Boutet, A.; Hotte, H.; Colinet, H.; Chown, S.L.; Convey, P. The rising threat of climate change for arthropods from Earth’s cold regions: Taxonomic rather than native status drives species sensitivity. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 5914–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.K.; Sharma, L.K. Efficacy of species distribution models (SDMs) for ecological realms to ascertain biological conservation and practices. Biodiversity and Conservation 2023, 32, 3053–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavi, R.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Elith, J. Predictive performance of presence-only species distribution models: a benchmark study with reproducible code. Ecological Monographs 2022, 92, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høye, T.T.; Loboda, S.; Koltz, A.M.; Gillespie, M.A.K.; Bowden, J.J.; Schmidt, N.M. Nonlinear trends in abundance and diversity and complex responses to climate change in Arctic arthropods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2002557117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, T.; McGarvey, D.J. Drivers of Odonata flight timing revealed by natural history collection data. Journal of Animal Ecology 2023, 92, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, J.C. Odonata Central, 2025. [CrossRef]

- GBIF.org. Occurrence Download, 2025. [CrossRef]

- The Pandas Development Team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Global Ecology and Biogeography 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. terra: Spatial Data Analysis; 2024.

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Long, Y. Projecting 1 km-grid population distributions from 2020 to 2100 globally under shared socioeconomic pathways. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Vernon, C.R.; Graham, N.T.; Hejazi, M.; Huang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Calvin, K. Global land use for 2015–2100 at 0.05° resolution under diverse socioeconomic and climate scenarios. Scientific Data 2020, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, S.; Joseph, H. xarray: N-D labeled Arrays and Datasets in Python. Journal of Open Research Software 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatulli, G.; Domisch, S.; Tuanmu, M.N.; Parmentier, B.; Ranipeta, A.; Malczyk, J.; Jetz, W. A suite of global, cross-scale topographic variables for environmental and biodiversity modeling. Scientific Data 2018, 5. Publisher: Springer Science and Business Media LLC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.L.; Boyce, M.S. Modelling distribution and abundance with presence-only data. Journal of Applied Ecology 2006, 43, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, B.; Hamm, N.a.s.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Toxopeus, A.G. Where is positional uncertainty a problem for species distribution modelling. Ecography 2014, 37, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Quality & Quantity 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnase, J.L.; Carroll, M.L. Automatic variable selection in ecological niche modeling: A case study using Cassin’s Sparrow (Peucaea cassinii). PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0257502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ab Lah, N.Z.; Yusop, Z.; Hashim, M.; Mohd Salim, J.; Numata, S. Predicting the Habitat Suitability of Melaleuca cajuputi Based on the MaxEnt Species Distribution Model. Forests 2021, 12, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Phillips, S.; Leathwick, J.; Elith, J. dismo: Species Distribution Modeling; 2024.

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modelling 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. predicts: Spatial Prediction Tools; 2024.

- Elith, J.; H. Graham, C.; P. Anderson, R.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; J. Hijmans, R.; Huettmann, F.; R. Leathwick, J.; Lehmann, A.; et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Newell, G.; White, M. On the selection of thresholds for predicting species occurrence with presence-only data. Ecology and Evolution 2016, 6, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Berry, P.M.; Dawson, T.P.; Pearson, R.G. Selecting thresholds of occurrence in the prediction of species distributions. Ecography 2005, 28, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, A.; Lobo, J.M. Threshold criteria for conversion of probability of species presence to either–or presence–absence. Acta Oecologica 2007, 31, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means; 2025.

- O’Brien, S.F.; Yi, Q.L. How do I interpret a confidence interval? Transfusion 2016, 56, 1680–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J. A brief tutorial on Maxent. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20060504165624/https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~schapire/maxent/tutorial/tutorial.doc (accessed on 4 May 2006).

- Wallingford, P.D.; Morelli, T.L.; Allen, J.M.; Beaury, E.M.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Bradley, B.A.; Dukes, J.S.; Early, R.; Fusco, E.J.; Goldberg, D.E.; et al. Adjusting the lens of invasion biology to focus on the impacts of climate-driven range shifts. Nature Climate Change 2020, 10, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randalls, S. History of the 2° C climate target. WIREs Climate Change 2010, 1, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. Topographic. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=67372ff42cd145319639a99152b15bc3 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M.; Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Lehmann, A.; Leathwick, J.; Ferrier, S. Sample selection bias and presence-only distribution models: implications for background and pseudo-absence data. Ecological Applications 2009, 19, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead-Thompson, R.C. Laboratory evaluation of pesticide impact on stream invertebrates. Freshwater Biology 1973, 3, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabry, C.; Dettman, C. Odonata Richness and Abundance in Relation to Vegetation Structure in Restored and Native Wetlands of the Prairie Pothole Region, USA. Ecological Restoration 2010, 28, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schalkwyk, J.; Pryke, J.S.; Samways, M.J.; Gaigher, R. Congruence between arthropod and plant diversity in a biodiversity hotspot largely driven by underlying abiotic factors. Ecological Applications 2019, 29, e01883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, P.; Noss, R.F. Do Habitat Corridors Provide Connectivity? Conservation Biology 1998, 12, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Records | Species | Records |

| Aeshna umbrosa | 1,010 | Hetaerina americana | 2,509 |

| Aeshna palmata | 578 | Hetaerina titia | 540 |

| Aeshna canadensis | 496 | Hetaerina vulnerata | 179 |

| Aeshna interrupta | 428 | Libellula luctuosa | 6,393 |

| Aeshna constricta | 291 | Libellula incesta | 5,135 |

| Argia fumipennis | 2,922 | Libellula pulchella | 3,959 |

| Argia apicalis | 2,858 | Libellula vibrans | 2,656 |

| Argia moesta | 2,678 | Libellula cyanea | 1,691 |

| Argia sedula | 1,866 | Plathemis lydia | 8,991 |

| Argia tibialis | 1,614 | Plathemis subornata | 127 |

| Calopteryx maculata | 3,669 | Sympetrum vicinum | 2,880 |

| Calopteryx aequabilis | 514 | Sympetrum corruptum | 2,157 |

| Calopteryx dimidiata | 307 | Sympetrum semicinctum | 1,073 |

| Calopteryx angustipennis | 89 | Sympetrum obtrusum | 876 |

| Calopteryx amata | 72 | Sympetrum ambiguum | 749 |

| Variables | VIF | Variables | VIF |

| BIO1 (Annual Mean Temperature) | 11.350 | PFT10 (Bdlf Dcds Shrub Temperate) | 4.303 |

| BIO7 (Temperature Annual Range) | 5.164 | PFT11 (Bdlf Dcds Shrub Boreal) | 7.013 |

| BIO12 (Annual Precipitation) | 3.031 | PFT12 (C3 Arctic) | 3.776 |

| PFT1 (Ndlf Evgr Tree Temperate) | 5.136 | PFT13 (C3 Grass) | 11.423 |

| PFT2 (Ndlf Evgr Tree Boreal) | 20.126 | PFT14 (C4 Grass) | 6.675 |

| PFT4 (Bdlf Evgr Tree Tropical) | 3.705 | PFT31 (Urban) | 1.352 |

| PFT5 (Bdlf Evgr Tree Temperate) | 1.389 | PFT32 (Barren) | 5.640 |

| PFT6 (Bdlf Dcds Tree Tropical) | 2.528 | PFT Rainfed Crops Cumulative | 5.035 |

| PFT7 (Bdlf Dcds Tree Temperate) | 3.566 | PFT Irrigated Crops Cumulative | 1.497 |

| PFT8 (Bdlf Dcds Tree Boreal) | 1.798 | HPD (Human Population Density) | 1.028 |

| PFT9 (Bdlf Evgr Shrub Temperate) | 1.011 | Slope | 1.377 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).