Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuesta Santos, A.; Valencia Rodríguez, M. Capital humano: Contexto de su gestión. Desafíos para Cuba. Revista Cubana de Ingeniería 2018, 34, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Magallanes, M.A. The impact of business sustainability over organizational culture. NovaRua 2020, 12, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñonez, C.; Laverde, L. Construcción participativa de modelos de negocios en organizaciones rurales. Telos 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasencia Soler, J.A.; Marrero Delgado, F.; Bajo Sanjuán, A.M.; Nicado García, M. Modelos para evaluar la sostenibilidad de las organizaciones. Estudios Gerenciales 2018, 34, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, F.; Chávez, G.; Puyana, J.; Mitrovic, K.; Zuleta, M. (2022). Sustentabilidad en las empresas como oportunidad de negocio: Valor según los ejecutivos. Boston Consulting Group. https://web-assets.bcg.com/55/1f/1c7b5bb9437f9c75765fa25eabc7/esg-ssa-sustentabilidad-como-oportunidad.pdf.

- Ortega, A.; Marín, K. (2019). La innovación social como herramienta para la transformación social de comunidades rurales. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, (57), 87–99. [CrossRef]

- La, P.B.; Le, H.N.T.; Hazenberg, R. (2025). The growth of social innovation research in higher education institutions (HEIs). International Journal Of Sustainability In Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Planells-Aleixandre, E.; García-Aracil, A.; Isusi-Fagoaga, R. University’s Contribution to Society: Benchmarking of Social Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra, M.Á. C.; Céspedes Gallegos, S.; Sánchez Leyva, J.L. Reflexión sobre innovación social responsable desde la óptica de la educación superior. Tendencias 2025, 26, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Paredes, G.X.; Juarez-Alvarez, C.R.; Cuya-Zevallos, C.; Mamani-Machaca, E.S.; Esquicha-Tejada, J.D. Enhancing social innovation through design thinking, challenge-based learning, and collaboration in university students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, J.; Ganga, F.; Rivera, Y. Estado del arte de la innovación social: Una mirada a la perspectiva de Europa y Latinoamérica. Opción 2017, 33, 563–587. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda Celaya, L.C. (2022). Cultura organizacional de innovación: Análisis de las empresas proveedoras de servicios de la paraestatal PEMEX del sureste de la república mexicana [Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Málaga, España]. UMA Editorial. https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10630/26239/TD_PINEDA_CELAYA_Lourdes_del_Carmen.pdf?sequence=1.

- Briñeza, M.; Penagos, M. La sostenibilidad como estrategia competitiva en empresas del sector construcción del departamento de Antioquía, Colombia. Dimensión Empresarial 2021, 19, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés Medina, C.M. (2022). El impacto de la innovación en la sostenibilidad o continuidad de las empresas. Revista Reflexiones y Saberes, (16), 46–55. https://revistavirtual.ucn.edu.co/index.php/RevistaRyS/article/view/1447.

- Montoya, C.; Jesús, N.; Zazueta, U.; Luisa, M.; Ramírez, T.; Mercedes, L.; Araujo, V. (2022). Áreas de responsabilidad social empresarial en empresas sinaloenses: Un análisis desde la innovación social. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 28, 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Sanchís Palacio, J.R.; Campos Climent, V. (2008). La innovación social en la empresa: El caso de las cooperativas y de las empresas de economía social en España. Economía Industrial, 187–196. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2672088.

- Alberto, J. Innovación social: ¿Nueva cara de la responsabilidad social? Revista de Ciencias Sociales 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana Daube, D. Bases de la gestión de la innovación en las organizaciones. Gestión de las Personas y Tecnología 2011, 3, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, R.; Iruarrizaga, H.; Olaizola, I.; Molina, V.; Azucena, M. (2011). Innovadora: Propuesta de factores explicativos. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1), 107–117. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2741/274119499007.pdf.

- Rodríguez, A.; García, C.; Salmerón, R.; García, C. (2018). El coeficiente de determinación en la regresión de cresta. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6641075.pdf.

- Pérez, M.B. (2019). Paradigmas de investigación. En El proceso de investigación (pp. 32–57). Ediciones Universidad de Guadalajara. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, I. Emprendimiento e innovación social en México. Projectics / Proyéctica / Projectique 2019, 23, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrouyet, M.C. (2015). Desarrollo sustentable: Origen, evolución y su implementación para el cuidado del planeta (Trabajo de grado, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes). Repositorio Institucional Digital de Acceso Abierto. https://ridaa.unq.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/20.500.11807/154/TFI_2015_larrouyet_003.pdf?sequence=1.

- Prieto Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. (2017). Economía circular: Relación con la evolución del concepto de sostenibilidad y estrategias para su implementación. Memoria Investigaciones en Ingeniería, 15, 85–95. https://revistas.um.edu.uy/index.php/ingenieria/article/view/308.

- Cantú Mata, J.L. Desempeño de innovación sustentable y ventaja competitiva sustentable en organizaciones manufactureras. Interciencia 2022, 47, 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Palafox, K. Sustentabilidad como estrategia competitiva en la gerencia de pequeñas y medianas empresas en México. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia 2019, 24, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maycotte de la Peña, M.L.; Robles Parra, J.M.; Paz Luna, J.L. Sustentabilidad corporativa en las organizaciones productoras de uva de mesa sonorense. Epistemus 2023, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Gracia, J.F.; Avendaño Hernández, V.; Buitrón Ramírez, H.A. La innovación social en las PYMES como estrategia para generar una ventaja competitiva en el mercado empresarial. Boletín Científico de la Escuela Superior Atotonilco de Tula 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Jiménez, J. (2018). La percepción ciudadana sobre la innovación social en México: Retos y áreas de oportunidad. Foro Consultivo Científico y Tecnológico. https://www.foroconsultivo.org.mx/FCCyT/documentos/Innovacion_social_Tomo_2_2018.pdf.

- Carrillo-Punina, A.P.; Galarza Torres, S.P. Reportes de sostenibilidad de organizaciones sudamericanas. Ciencias Administrativas 2022, 18, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado Villalpando, E.; Rodríguez Velázquez, J.R. (2017). Innovación social para la gestión de la sustentabilidad. Ciencia Nicolaita, (69), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Colpas, F.; Taron, A.; y Fuentes, L. Innovación social y sostenibilidad en América Latina: Panorama actual Social. Revista Espacios 2019, 40, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Pablo, J. D.; Jiménez Estévez, P. Evaluación de la cooperación empresarial como estrategia competitiva en el sector agroalimentario: El caso español. Ecos De Economía 2008, 12, 101–144. [Google Scholar]

- Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económicos. (2009). Innovación en las empresas. Una perspectiva microeconómica. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/es/publications/reports/2009/11/innovation-in-firms_g1g191df/9789264208322-es.pdf.

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C. (2018). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta (6.ª ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Hernández González, O. Aproximación a los distintos tipos de muestreo no probabilístico que existen. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral 2021, 37. https://revmgi.sld.cu/index.php/mgi/article/view/1442.

- Salguero, Y. ; Flores, [Inicial]. (2023). [Falta información para completar referencia].

- Soler, S.; Soler, L. The usage of the Cronbach Coefficient alpha in the analysis of the written instruments. Revista Médica Electrónica 2012, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chiner, E. (2011). La validez. Universidad de Alicante. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/19380/25/Tema%206-Validez.pdf.

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- Moral de la Rubia, J. Revisión de los criterios para validez convergente estimada a través de la varianza media extraída. Psychologia: Avances de la Disciplina 2019, 13, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, J.; Martínez-Caro, L. La validez discriminante como criterio de evaluación de escalas: ¿Teoría o estadística? Universitas Psychologica 2009, 8, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.; Fierro, E. Aplicación de la técnica PLS-SEM en la gestión del conocimiento: Un enfoque técnico práctico. Revista Conocimiento Global 2018, 3, 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2014, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, M.; Arancibia, H. Potencia estadística y cálculo del tamaño del efecto en G*Power. Revista de Psicología (Universidad de Antofagasta) 2014, 23, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rositas-Martínez, J. (2005). Factores críticos de éxito en la gestión de calidad y su grado de presencia e impacto en la industria manufacturera mexicana. http://eprints.uanl.mx/1675/1/1080127411.

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. (2017). Introducción al modelado de ecuaciones estructurales por mínimos cuadrados parciales (PLS-SEM) (3.ª ed., trad. al español). Sage Publishing.

- Martínez-Celorrio, X. (2017). La innovación social: Orígenes, tendencias y ambivalencias. En J. Subirats, M. Gómez, & M. González (Eds.), Innovación social y políticas urbanas en España (pp. 33–45). Icaria Editorial. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6062961.

- Cortés Mura, H.G.; Peña Reyes, J.L. (2015). De la sostenibilidad a la sustentabilidad: Modelo de desarrollo sustentable para su implementación en políticas y proyectos. Revista EAN, (78), 40–55. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/206/20640430004.pdf.

- García Flores, V. (2021). Innovación social: Factores, características y áreas de impacto [Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Sevilla]. Repositorio de la Universidad de Sevilla. https://portalinvestigacion.um.es/documentos/647b7ba188c57a26460448f3.

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | Number of Items | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Innovation | .945 | .947 | 20 | |

| Sustainability | .928 | .929 | 14 |

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Genre | ||

| Female | 93 | 46.5 |

| Male | 107 | 53.5 |

| Age | ||

| 20 - 25 | 23 | 11.5% |

| 26 - 30 | 34 | 17% |

| 31 - 35 | 18 | 9% |

| 36 - 40 | 23 | 11.5% |

| 41 - 45 | 19 | 9.5% |

| 45 - 50 | 28 | 14% |

| 51 - 55 | 22 | 11% |

| 56 - 60 | 16 | 8% |

| 61 - 85 | 17 | 8.5% |

| Length | ||

| 1 month - 5 years | 101 | 50.5% |

| 6 - 10 years | 38 | 19.5% |

| 11 - 19 years | 20 | 10% |

| 20 - 25 years | 20 | 10% |

| 26 - 30 years | 6 | 3% |

| 31 - 35 years | 6 | 3% |

| Number of employees | 200 | 100% |

| Variable | Dimension | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|

Social Innovation |

Social Impact | 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.0388 | 1.02301 |

| Type of Innovation | 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.7525 | .96157 | |

| Economic viability | 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.0800 | 1.03784 | |

| Intersectoral collaboration | 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.8263 | 1.03403 | |

| Replicability | 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.5425 | 1.00160 | |

|

Sustainability |

||||||

| 200 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.1722 | .71680 | ||

| Dimensions | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) |

| Intersectoral Collaboration | 0.849 | 0.879 |

| Social Impact | 0.833 | 0.851 |

| Replicability | 0.888 | 0.893 |

| Innovation Type | 0.817 | 0.823 |

| Economic Viability | 0.837 | 0.864 |

| Sustainability | 0.855 | 0.884 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha based on standardized elements | Number of elements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Innovation | .949 | .949 | 20 |

| Social impact | .833 | 4 | |

| Economic viability | .836 | 4 | |

| Innovation type | .817 | 4 | |

| Intersectoral collaboration | .849 | 4 | |

| Replicability | .887 | 4 |

|

| Sustainability |

.860 | .861 | 14 |

| Complete Instrument | .951 | .950 | 34 |

| Collaboration | Social impact | Replicability | Innovation type | Economic Viability | Sustainability | |

| Collaboration | 0.827 | |||||

| Social impact | 0.734 | 0.816 | ||||

| Replicability | 0.790 | 0.630 | 0.865 | |||

| Innovation type | 0.723 | 0.693 | 0.683 | 0.804 | ||

| Economic viability | 0.648 | 0.735 | 0.614 | 0.719 | 0.820 | |

| Sustainability | 0.644 | 0.686 | 0.647 | 0.676 | 0.675 | 0.648 |

| Item | Collaboration | Social impact | Replicability | Innovation type | Economic viability | Sustainability |

| COL1 | 0.770 | 0.489 | 0.426 | 0.428 | 0.398 | 0.411 |

| COL2 | 0.868 | 0.653 | 0.758 | 0.732 | 0.599 | 0.593 |

| COL3 | 0.875 | 0.676 | 0.733 | 0.664 | 0.618 | 0.641 |

| COL4 | 0.792 | 0.581 | 0.636 | 0.502 | 0.482 | 0.428 |

| IMP1 | 0.617 | 0.880 | 0.607 | 0.621 | 0.620 | 0.640 |

| IMP2 | 0.662 | 0.867 | 0.559 | 0.669 | 0.685 | 0.609 |

| IMP3 | 0.562 | 0.743 | 0.412 | 0.469 | 0.504 | 0.450 |

| IMP4 | 0.553 | 0.766 | 0.451 | 0.476 | 0.577 | 0.516 |

| REP1 | 0.773 | 0.641 | 0.887 | 0.655 | 0.598 | 0.617 |

| REP2 | 0.617 | 0.464 | 0.855 | 0.577 | 0.454 | 0.527 |

| REP3 | 0.677 | 0.541 | 0.879 | 0.538 | 0.537 | 0.570 |

| REP4 | 0.653 | 0.519 | 0.837 | 0.590 | 0.526 | 0.516 |

| TIP1 | 0.525 | 0.561 | 0.478 | 0.814 | 0.659 | 0.542 |

| TIP2 | 0.629 | 0.587 | 0.617 | 0.864 | 0.590 | 0.601 |

| TIP3 | 0.594 | 0.589 | 0.602 | 0.793 | 0.543 | 0.535 |

| TIP4 | 0.577 | 0.487 | 0.493 | 0.741 | 0.487 | 0.490 |

| VIA1 | 0.610 | 0.673 | 0.579 | 0.716 | 0.878 | 0.674 |

| VIA2 | 0.541 | 0.626 | 0.556 | 0.550 | 0.825 | 0.553 |

| VIA3 | 0.550 | 0.609 | 0.523 | 0.546 | 0.851 | 0.540 |

| VIA4 | 0.388 | 0.476 | 0.304 | 0.478 | 0.715 | 0.405 |

| SAMB1 | 0.513 | 0.554 | 0.582 | 0.604 | 0.502 | 0.801 |

| SAMB2 | 0.501 | 0.528 | 0.521 | 0.579 | 0.556 | 0.832 |

| SAMB3 | 0.514 | 0.529 | 0.558 | 0.609 | 0.559 | 0.833 |

| SAMB4 | 0.376 | 0.457 | 0.463 | 0.476 | 0.500 | 0.743 |

| SAMB5 | 0.338 | 0.355 | 0.250 | 0.252 | 0.278 | 0.543 |

| SAMB6 | 0.309 | 0.360 | 0.270 | 0.251 | 0.303 | 0.551 |

| SECO1 | 0.465 | 0.485 | 0.524 | 0.517 | 0.566 | 0.673 |

| SECO2 | 0.398 | 0.443 | 0.266 | 0.302 | 0.453 | 0.525 |

| SECO3 | 0.219 | 0.278 | 0.151 | 0.298 | 0.273 | 0.465 |

| SSOC2 | 0.287 | 0.307 | 0.156 | 0.184 | 0.240 | 0.375 |

| SSOC4 | 0.534 | 0.488 | 0.524 | 0.443 | 0.392 | 0.595 |

| Collaboration | Social impact | Replicability | Innovation type | Viability | Sustainability | |

| Collaboration | ||||||

| Social impact | 0.862 | |||||

| Replicability | 0.882 | 0.718 | ||||

| Innovation type | 0.843 | 0.830 | 0.799 | |||

| Viability | 0.737 | 0.866 | 0.692 | 0.844 | ||

| Sustainability | 0.727 | 0.802 | 0.692 | 0.767 | 0.762 |

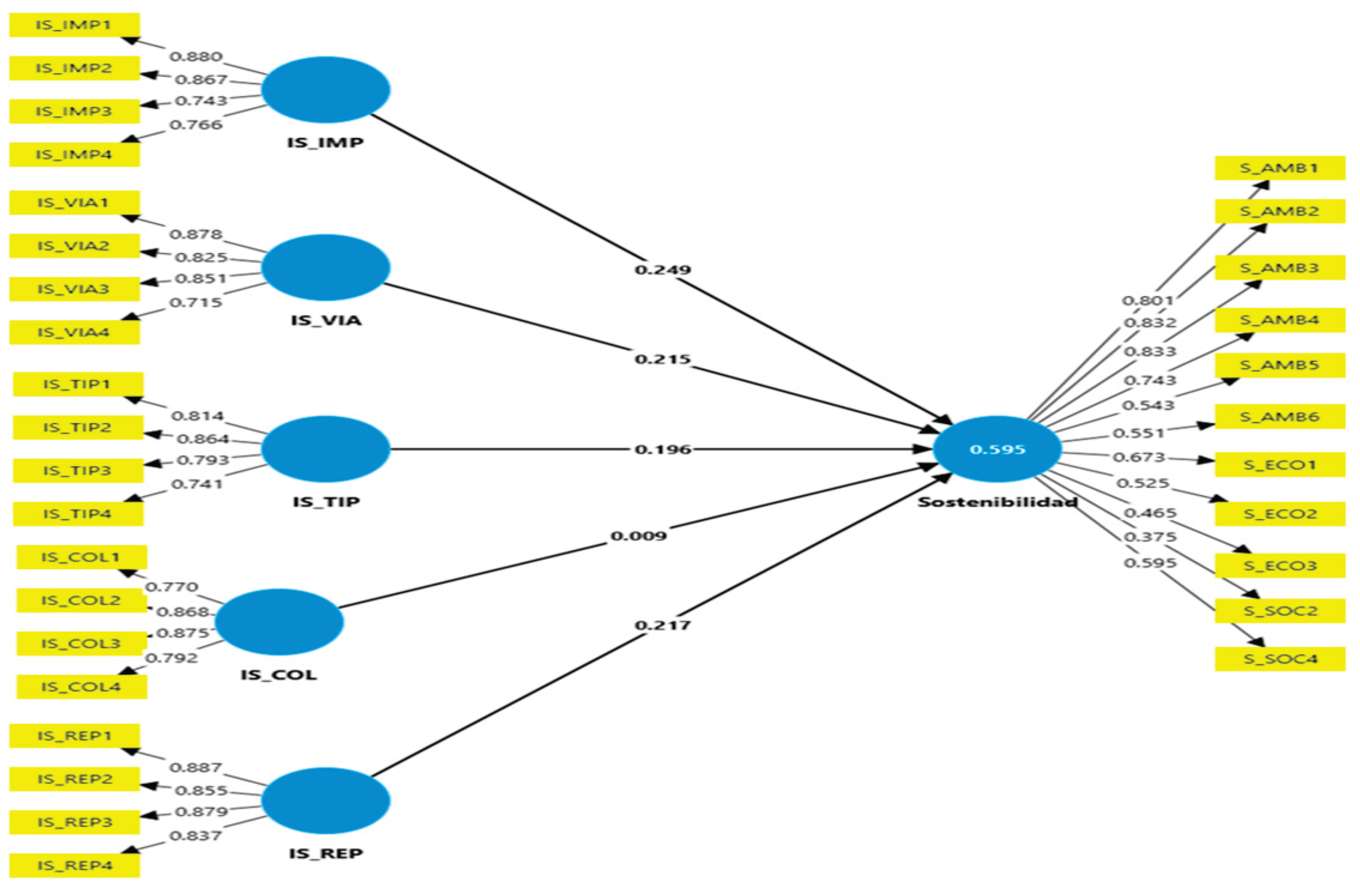

| VIF | |

| Collaboration -> Sustainability | 3.726 |

| Social impact -> Sustainability | 2.965 |

| Replicability -> Sustainability | 2.895 |

| Innovation type -> Sustainability | 2.815 |

| Economic viability -> Sustainability | 2.663 |

| R² | Adjusted R² | |

| Sustainability | .595 | .585 |

| F² | |

| Collaboration-> Sustainability | 0.000 |

| Social impact -> Sustainability | 0.052 |

| Replicability -> Sustainability | 0.040 |

| Innovation type-> Sustainability | 0.034 |

| Economic viability-> Sustainability | 0.043 |

| Path Coefficient | |

| Collaboration-> Sustainability | 0.009 |

| Social impact -> Sustainability | 0.249 |

| Replicability -> Sustainability | 0.217 |

| Innovation type-> Sustainability | 0.196 |

| Economic viability-> Sustainability | 0.215 |

| Hypothesis | T Student | P Value | Path Coefficient | Result |

| Hi. The variable social innovation has a positive and significant effect on the variable sustainability. |

14.086 | .000 | Accepted | |

| H1. Social impact has a positive and significant effect on sustainability. | 3.260 | 0.001 |

.249 Important |

Accepted |

| H2. Economic viability has a positive and significant effect on sustainability. |

2.752 |

0.006 |

.215 Important |

Accepted |

| H3. Type of innovation has a positive and significant effect on sustainability. | 2.139 | 0.032 | .196 Considerable |

Accepted |

| H4. Intersectoral collaboration has a positive and significant effect on sustainability. |

.093 |

0.926 |

. 009 Imperceptible |

Rejected |

| H5. Replicability has a positive and significant effect on sustainability. | 2.00 |

0.048 | .217 Important |

Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).