Introduction

Cancer is generally characterized by uncontrolled physiologically-detrimental cell growth and has been documented in nearly every tissue. Advanced stages of cancer often lead to deadly metastasis that can spread and overwhelm other tissues. Since the discovery of cancer over 5,000 years ago in ancient Egypt, scientists have made impressive progress in treating patients who have this devastating disease [

1]. Despite these advances, cancers like pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remain a significant challenge for current treatments.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US. From 2013 to 2022, lung cancer has seen a 3.7-4.8% decline in death rate

per year. By comparison, the death rate for pancreatic cancer over the past several decades has

increased by around 0.2 to 0.3% per year. This indicates that pancreatic cancer clearly remains a challenge to combat even with current treatment options. It is estimated that 67,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer will be diagnosed in the US, and 52,000 will die from the disease in 2025 [

2]. For these patients, new therapies are clearly needed.

There are two main pancreatic cancers: endocrine cell tumors and exocrine cell tumors. Endocrine cells secrete substances like insulin and glucagon directly into the bloodstream. Exocrine cells release enzymes and other substances into the small intestine to aid with digestion. Adenocarcinomas most commonly form from duct-forming exocrine cells and have distinct morphology [

2]. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common type of pancreatic cancer and is associated with high mortality rates due to late detection, limited treatment options, and a dense tumor microenvironment [

3].

There are several risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Smoking can double the risk of pancreatic cancer compared to those who have never smoked, and the use of smokeless tobacco increases risk as well. Type 2 Diabetes and/or excess body weight can also increase the risk of developing the cancer. Genetically, a family history of pancreatic cancer can lead to a higher risk in subsequent generations, and those with genetic syndromes like Lynch syndrome and inherited mutations in genes such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 can increase risk. Heavy alcohol consumption, which can lead to chronic pancreatitis, may also increase the risk. While lifestyle changes have improved outcomes for other diseases, there are other key factors that impact PDAC survival.

One of the most challenging features of pancreatic cancer is that it is difficult to detect, especially at earlier stages. This means that most patients’ cancers are detected at advanced stages after the tumor has likely metastasized. At this point, treatment options are often limited and palliative. If detected early while the tumor is still small, patient survival is as high as 84%. Unfortunately, patients diagnosed when tumor size exceeds 2 cm or is metastatic see survival rates as low as 11% [

4]. At this stage, the tumor is often unresectable and resistant to radiation or chemotherapy [

3]. For this reason, improved diagnostic strategies and treatment options that overcome resistance are critical. This review serves as a contextual guide for aspiring scientists and physicians to discuss how far we have come in the medical treatment of pancreatic cancer and how much there is yet to be done.

The Discovery of Pancreatic Cancer

Early Medicine and Cancer in the Age of Enlightenment

Our understanding of pancreatic cancer has evolved significantly since its first identification. It all began when Italian anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni discovered several cases of pancreatic “scirrhus”, or hard tumor, which he recorded in his 1761 publication

The Seats and Causes of Disease [

5,

6]. Because Morgagni worked in an era where physicians believed that illnesses, including cancer, resided in the fluid “humors” of the body, he was only able to use the tools available to him to describe the hard mass of cells observed in the patient’s pancreas. It would not be until much later that physicians would gain a better understanding of the cellular origin of disease to develop more specific terminology for classifying these types of cancers.

The term “adenocarcinoma” was first used in 1872. In the 18th century, cancers were categorized by how they looked to the naked eye. It wasn’t until Johannes Müller (1801-1858) studied tumors under the microscope in Berlin that tumor classification became more systematic. Müller published a detailed analysis of the microscopic features of benign and malignant tumors and explained that cancer involves the rapid and uncontrolled formation of new cells inside a diseased organ. He classified multiple types of tumor growths through microscopic analysis and created the classification for

carcinoma alveolare, which we know today as a type of adenocarcinoma [

7].

By the 1970s, the term ductal adenocarcinoma was commonly used in medical journals, like

Mayo Clinic Proceedings and

Histopathology, to describe tumors originating from exocrine cells [

8,

9,

10]. Pathology textbooks and learning tools surrounding oncology also started to standardize the use of this terminology.

Early Surgical Interventions

In the 1800s, surgery and anesthesia underwent a revolution. In the 1840s, William T.G. Morton demonstrated the efficacy and usefulness of anesthesia because of its ability to remove patient discomfort during surgery [

6]. In the 1860s, Joseph Lister invented antisepsis techniques to prevent infection from surgery, ultimately leading to an incredible decline in postoperative mortality rates. With these advancements, surgical procedures in the abdominal area became more frequent. It was during this period that many of the building blocks for pancreatic resection were developed. For instance, palliative biliary bypass, a surgery-involving removal of different parts of the biliary system, was the first form of surgical treatment for PDAC [

6] because it had been used to remove local malignant obstructions.

The first anatomical resection for a solid tumor of the pancreas was a distal pancreatectomy performed by German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg in 1882 [

11]. During the 90-minute procedure, he resected a large spindle cell carcinoma along with the pancreas tail from which the tumor arose. Unfortunately, the impact of the surgery was unclear because an unrelated infection and worsening malnutrition caused the patient to die several weeks later. Despite this, Trendelenburg had successfully shown that it was technically possible to surgically remove a diseased pancreas, marking a milestone in pancreatic cancer treatment.

Early Therapeutics

Because surgery only provided small improvements in quality of life against PDAC, clinicians sought pharmaceutical alternatives. Since the 1950s, a variety of therapeutic tools, including anti-metabolites, nucleoside analogs, and DNA-intercalating compounds, have been used against pancreatic cancer, although with low patient response rates and meager improvements in survival [

12]. Two of the most common pancreatic cancer therapeutics are anti-metabolites 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and Gemcitabine.

5-FU was first discovered in 1957 and has continued to be used for almost 40 years as adjuvant therapy (additional treatment after initial treatment) [

13]. The earliest trial demonstrating the efficacy of 5-FU (done with radiation) was performed by the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group in 1985. They found that the median survival for the treatment group was significantly longer than the median survival for the control group (20 months vs.11 months) [

12]. While this trial demonstrated some improvement in survival, response rates to 5-FU monotherapy were highly variable, with subsequent studies suggesting high variation or patient heterogeneity.

Gemcitabine was introduced in 1986 as a pyrimidine nucleoside antimetabolite that inhibits the synthesis of DNA. It was originally synthesized as a potential antiviral agent but was found to have even better anti-cancer properties. Gemcitabine has received approval for clinical treatment in a variety of solid-tumor cancers, including pancreatic and non-small cell lung cancer [

14]. In 1997, it was demonstrated that gemcitabine was more effective than 5-FU in the alleviation of some disease-related symptoms in patients with advanced PDAC and that it conferred a modest survival advantage over 5-FU [

15]. This study established gemcitabine monotherapy as the standard of care in pancreatic cancer from 1997 until new treatments were developed.

In the ensuing decades, advancements in medical research and technology have led to the development of more effective compounds and combination therapies. These therapeutics have been driven by a better understanding of PDAC’s physiology and molecular drivers.

Modern Definitions and Treatments of PDAC

PDAC in the Genomic Age

Histology and Physiology

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas are characterized by a variety of microscopic factors. Conventional PDACs have dense desmoplastic stroma, the connective tissue surrounding the tumor, that is intermixed with irregularly shaped glands instead of normal, rounded ducts. These can present as small nests of malignant epithelial cells [

16]. The appearance of PDAC under H&E stains is also highly heterogeneous. Within the same tumor, appearance can vary largely: some cancer cells may have healthy morphology, while others are irregular and mishappen. PDAC also presents with inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity, with a wide range of cell types and morphologies from tumor to tumor.

For example, a cancerous pancreas may display complex interconnecting tumoral glands in which glands branch out and twist and connect to form a tangled, maze-like pattern, in contrast to forming neat, separate tubes. Another example is the formation of large, abnormal ducts (large duct type). Other characteristics include but are not limited to poorly differentiated epithelial tumors with eosinophilic (pink-staining) or clear cells, the formation of finger-like projections (micropapillae) inside the lumen of ducts, cribriform histology (sieve/honeycomb-like structure with many small holes) with foamy cells (bubbly-looking interior), and the spreading of cancer cells along the inner lining of the ducts in a thin, creeping pattern (pagetoid) [

16].

PDAC also shows aggressive histological features that often manifest in resected PDAC specimens. These include lymph node metastasis, tumor invasion into tissues surrounding the pancreas (peripancreatic tissue), spread of cancer to nearby vessels and organs/structures, tumor spread along nerves (perineural invasion), as well as trace amounts of leftover cancer after resection.

The heterogeneity and the aggressive nature of PDAC cancerous cells once again explain the reason why this type of cancer is so difficult to treat and often reaches advanced stages and metastasis if not detected early. These histological features often arise from the common genetic mutations that ultimately lead to cancer.

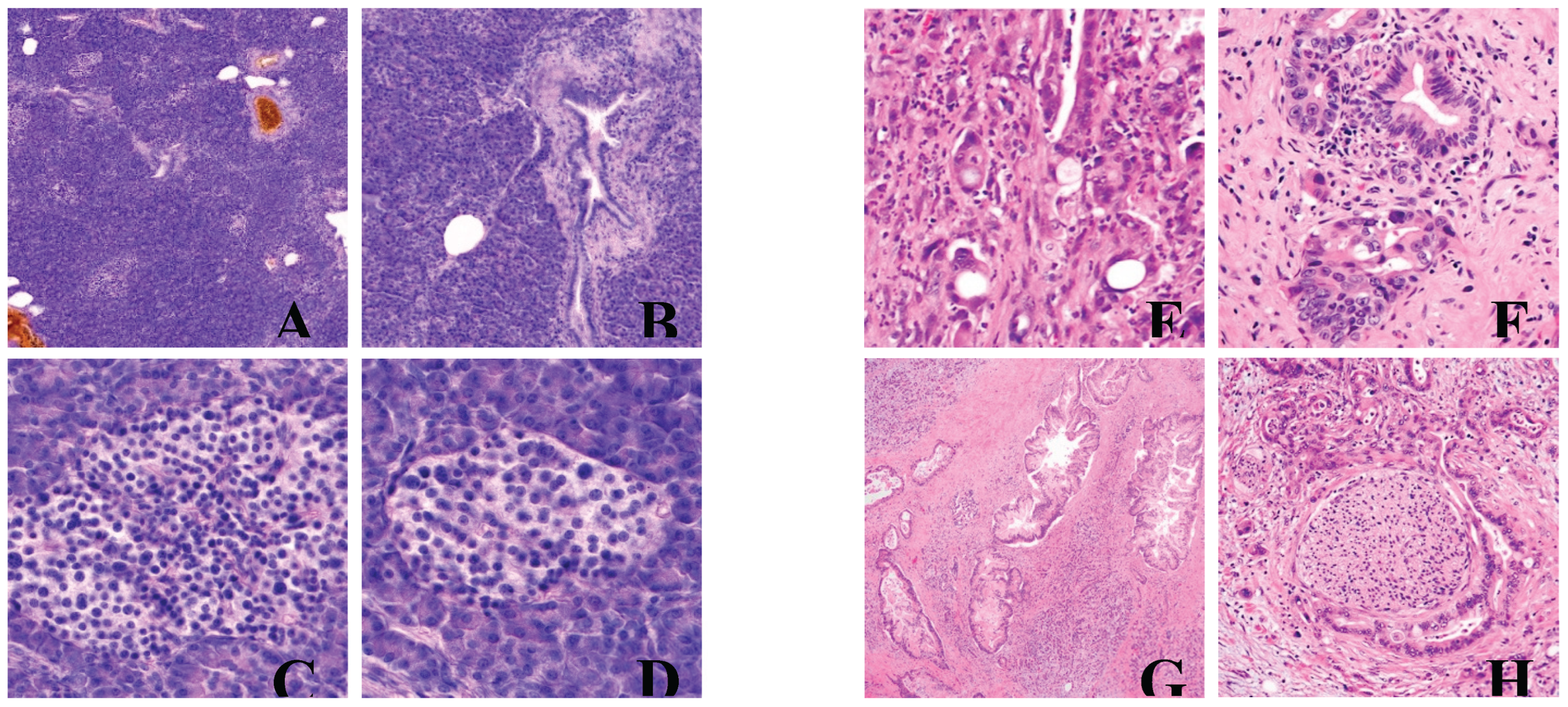

Here we present a handful of examples of healthy versus diseased pancreatic tissue sections and tumors compiled from PathologyOutlines.com.

Figure 1.

Normal versus abnormal histology of pancreatic tissue. A) Normal acinar parenchyma of pancreas, with sparse ducts and islets of Langerhans. B) Detail of a duct lined with columnar ductal epithelium and 2 islets of Langerhans on the right. C) Islet of Langerhans, detail. D) Islet of Langerhans, detail. E) Poorly differentiated with incompletely formed abortive glands. F) Marked nuclear pleomorphism with 4x anisonucleosis within one tumor gland. G) Large infiltrating tumor glands with intraluminal neutrophils and granular debris. H) Perineural invasion. A), B), C), and D) contributed by Jan Hrudka, M.D., Ph.D. E), F), G), and H) contributed by Wei Chen, M.D., Ph.D.

Figure 1.

Normal versus abnormal histology of pancreatic tissue. A) Normal acinar parenchyma of pancreas, with sparse ducts and islets of Langerhans. B) Detail of a duct lined with columnar ductal epithelium and 2 islets of Langerhans on the right. C) Islet of Langerhans, detail. D) Islet of Langerhans, detail. E) Poorly differentiated with incompletely formed abortive glands. F) Marked nuclear pleomorphism with 4x anisonucleosis within one tumor gland. G) Large infiltrating tumor glands with intraluminal neutrophils and granular debris. H) Perineural invasion. A), B), C), and D) contributed by Jan Hrudka, M.D., Ph.D. E), F), G), and H) contributed by Wei Chen, M.D., Ph.D.

Molecular Characterization of PDAC

The wide array of studies performed on pancreatic cancer determined four genes of interest that are usually mutated:

KRAS,

TP53,

CDKN2A, and

SMAD4 [

17,

18,

19].

KRAS gene mutations are usually found in 85% of all pancreatic cancers, while the three other genes are mutated in over 50% of cases. Mutant

KRAS causes the progression of tumors by activating downstream cell signaling pathways involved with proliferation, immunosuppression, and cell metabolism reprogramming. This mutated gene, in combination with mutated tumor suppressor genes like

TP53,

CDKN2A, and

SMAD4, promotes pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis.

Current Diagnostic Paradigm

One of the largest remaining challenges in PDAC treatment is its late detection. Patients often show no apparent symptoms until they reach a more advanced stage of pancreatic cancer. Because surgery is often impossible and ineffective at advanced stages, and because surgery is the only potentially curable treatment for PDAC, most patients are unable to receive surgical resection and must rely on less potent methods of treatment down the line. As explained by the National Cancer Institute, the chances of living for 5 years after diagnosis are much higher for early-stage PDAC (44%) compared to the meager survival rate for late-stage disease (3%) [

20]. Detection remains a significant challenge for physicians, so it’s imperative to develop more powerful diagnostic tools to improve patient survival.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, pancreas imaging involves the use of pancreatic protocol computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. If the spread of cancer is suspected, further imaging such as CT of the chest and pelvis, MRI of the liver, or positron emission tomography/CT/MRI may be done. Pancreatic cancer progression may be described with numerical stages (Stage 0, I, II, III, and IV), with each consecutive stage indicating a more advanced and often more deadly phase of disease [

21]. To stage the cancer, physicians often use endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or a laparoscopy.

Blood diagnostic tests are limited, with two main methods being liver function tests and CA 19-9 biomarker testing. Even though CA 19-9 is the best validated biomarker for PDAC, it often shows insufficient sensitivity and specificity for early screening. Because of this, microRNAs (miRNAs) like miR-7, miR-21, and miR-155 have been researched for their potential usefulness due to their links to major cancer hallmarks in most solid tumors, including pancreatic cancer.

To confirm cancer presence, a needle biopsy is often performed with EUS or an image-guided biopsy through the skin. For personalized treatment, genetic tests can be done to detect the presence of inherited mutations that may increase the chance of pancreatic cancer. Other biomarker tests of cancer cells are also performed to obtain a molecular profile that can be useful for personalized treatments [

22].

Current Standard of Care

Surgery

As the only potential curative treatment for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, surgical resection has been widely used as a treatment for earlier-stage pancreatic cancers. In a study done by Zheng Li et al. (2023), researchers found that surgical resection significantly prolonged the long-term prognosis of PDAC patients who had an intermediate stage of cancer between localized disease and aggressive metastasis (oligometastatic) [

23]. Researchers found that patients who had undergone surgery had better overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) than those without; overall survival improved by about three months (9.49 vs. 6.45 months with a

p < 0.01), and cancer-specific survival improved by about three months as well (9.76 vs. 6.54 months,

p < 0.01). Patients who receive surgery often undergo adjuvant therapy downstream, like chemotherapy. Patients who might have an advanced stage of PDAC and cannot undergo the benefits of surgical resection often receive adjuvant therapy as well, usually in the form of palliative care.

Chemotherapy

As discussed before, Gemcitabine emerged as the leading chemotherapeutic agent in treating PDAC in the early 21st century. Gemcitabine remained the first-line treatment for locally advanced (non-resectable stage II or III) or metastatic (stage IV) PDAC through the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In 2010, FOLFIRINOX was introduced to clinical practice. FOLFIRINOX is a combination therapy that includes the chemical compounds 5-Fluorouracil/leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin. The PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 study compared FOLFIRINOX to Gemcitabine and determined that FOLFIRINOX showed superior median overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective responses. As of 2025, it remains a first-line option for otherwise healthy metastatic patients.

Paclitaxel (Abraxane) was another valuable chemotherapeutic that had been tested in PDAC, but its original formulation was found to be highly toxic with poor efficacy. In 2013, the MPACT Phase III clinical trial tested a novel albumin-conjugated paclitaxel formulation to reduce systemic toxicity. This landmark study showed that, in combination with Gemcitabine, albumin-bound paclitaxel produced a longer median overall survival (8.5 vs. 6.7 months,

p < 0.01) and median progression-free survival (5.5 vs. 3.7 months,

p < 0.01) compared to Gemcitabine alone. It was approved by the FDA in late 2013 for first-line treatment of metastatic PDAC, showing the importance of exploring novel formulations even for established molecules [

24].

Capecitabine (Xeloda) is another general cancer therapy that was appropriated for PDAC. This nucleoside metabolic inhibitor was first approved in 1998 as an adjuvant treatment for cancers like colorectal and breast cancer, and had its labeling updated in 2022 to include it as adjuvant therapy for resected PDAC as part of combination regimens [

25]. This change came from the ESPAC-4 phase 3 trial conducted in 2017, which discovered that the median overall survival for patients in the gemcitabine plus capecitabine group was longer compared to the median overall survival in the gemcitabine group (28.0 vs. 25.5 months) [

26].

One more recent first-line treatment option is the NALIRIFOX regimen. It is composed of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan, a liposomal topoisomerase 1 inhibitor known as Onivyde. NALIRIFOX was approved in February of 2024 for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma [

27]. Efficacy was evaluated with the NAPOLI3 trial, which found that there was a significant improvement in overall survival and progression-free survival for the NALIRIFOX regimen over gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel combination treatment (median overall survival: 11.1 months vs. 9.2 months; median progression-free survival: 7.4 months versus 5.6 months) [

28]. This combination treatment, and others, give physicians additional options when treating patients with poor response to other therapeutic options.

Targeted Therapy

In addition to chemotherapeutic agents that primarily act by preferentially poisoning highly proliferative cells, targeted therapies often target a specific protein in the diseased cells.

In 2018, larotrectinib was granted accelerated approval by the FDA for adult and pediatric patients with solid tumors that have a neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene fusion. In 2019, the FDA approved entrecitinib for NTRK solid tumors for adults and pediatric patients 12 years and older with solid tumors that have NTRK fusions. Though NTRK fusions are rare in PDAC for adenocarcinomas that harbor NTRK fusions, these treatments are vital [

29].

In 2019, the FDA approved the PARP inhibitor olaparib for the maintenance treatment of adult patients with damaging germline BRCA-mutated metastatic PDAC, for patients whose disease has not progressed for at least 16 weeks after a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen [

30].

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight diseases like cancer. Although immunotherapies are not as widespread as chemotherapies in the realm of cancer treatment, it has great potential to be used against common gene/protein changes found in cancers. For example, current immunotherapies often target proteins such as PD-1 (programmed cell death-1) protein, PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) protein, and CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) [

31]. Two common cancers where immunotherapies have been effective against include advanced melanoma [

32] and non-small-cell lung cancer [

33].

For PDAC, there are currently only two FDA-approved immunotherapeutic treatments: Dostarlimab (Jemperli) and Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Both immunomodulators are meant for subsets of patients with pancreatic cancer. Dostarlimab is approved for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer that has DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). Pembrolizumab is approved for patients with pancreatic cancer that has high microsatellite instability, dMMR, or high tumor mutational burden. Both are checkpoint inhibitors that target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway [

34].

Radiation

Radiation therapy involves using high-energy photons, electrons, protons, or another source to cause DNA damage in tumor cells to induce cell death. Ionizing radiation is used especially in cancer cases to cause base damage, single-strand, or double-strand breaks in proximity to DNA. Radiotherapy has a variety of uses: primary treatment for cancer, adjuvant therapy, before surgery to shrink tumors, and during palliative care. Having been applied as a form of cancer treatment for 120+ years, radiotherapy is a standard treatment option for a wide range of tumors, including lung, breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers [

35]. However, radiation therapy is controversial in the treatment of pancreatic cancer and has produced mixed results in different studies [

36].

Lines of Therapy

Based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for PDAC treatment, these are the professional guidelines for lines of therapy [

37].

First Line: Surgery (resection), chemotherapy/radiation therapy if unresectable (Gemcitabine, FOLIFIRINOX)

Second Line: Chemotherapy (combination of nanoliposomal irinotecan with 5-FU-Leucovorin, paclitaxel-gemcitabine), radiotherapy

Third Line: Most patients are not suited for third-line treatment due to poor nutritional status and/or poor performance status. In cases like this, best supportive care is the best treatment choice. Patients with better performance status may be included in clinical trials.

Ongoing R&D and Future Perspectives

While significant challenges remain in the detection and treatment of PDAC, clear improvements are being made with life-saving technologies in development. The major challenges still to overcome include detection speed, tumor physiology, and tumor biology, with many research groups actively working to tackle these challenges.

Biomarkers for Earlier Detection

As discussed, early detection of PDAC drastically improves patient survival. This illustrates the importance of continuing to develop better diagnostic tools and biomarkers. To detect PDAC earlier, researchers are developing improved diagnostic methods and discovering biomarkers like microRNAs (miRNAs) that are detectable earlier during disease progression. In addition to miR-7, miR-21, and miR-155, recent notable miRNA markers like miR-370-3p, miR-31-5p, and miR-205-5p have been identified for pancreatic cancer. Because the best-validated pancreatic cancer biomarker (CA19-9) often shows insufficient sensitivity and specificity for early screening, these biomarkers provide the potential for earlier detection [

38]. Other diagnosis methods are also being developed, including a cell-free DNA (cfDNA)-based liquid biopsy and multimodal early detection biomarker panels that include, for example, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), exosomes, proteomics, and methylation with imaging-based tools like radiomics and machine learning-assisted interpretation [

39]. These tools combined have the potential to improve patient survival by detecting pancreatic cancer earlier.

Developing Novel Therapies

In addition to detection, two unique biological challenges for PDAC are its genetic makeup, particularly KRAS mutations, and the physiology of the tumor microenvironment (TME). While early-stage PDAC can be treated by surgical resection, more advanced stages of PDAC are being treated insufficiently with chemotherapies. To improve the therapeutic window of PDAC treatments and address KRAS mutations and the dense TME, new drug delivery platforms and therapeutic modalities are being developed.

For instance, Revolution Medicine is developing a small-molecule drug that more specifically inhibits the

RAS gene family, including

KRAS. Their recent drug called RMC-6236 is currently in Phase 1/1b trials to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity of this drug with dose escalation in adult patients [

40]. A common family of

KRAS mutations involved in PDAC is

KRAS G12X mutations. To combat these mutations, companies are developing therapies that specifically target these mutations. For example, siG2D-LODER, a novel bio-degradable polymeric matrix that encompasses a small interfering RNA, is being developed to fight broadly against

KRAS G12X mutations [

41]. Combined with chemotherapy, siG2D-LODER is undergoing a phase 2 study for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer [

42]. Targeted drugs are also being developed for other rarer gene fusions. For instance, the FDA granted accelerated approval to zenocutuzumab in late 2024 for patients who have advanced, unresectable, or metastatic PDAC that includes an

NRG1 gene fusion. Though this type of fusion is rare, the drug offers potential life-saving treatment for this subset of pancreatic cancer patients [

43].

The PDAC tumor creates a dense wall of stromal cells that makes it tough for current treatments to reach the intended target. Tumors also express drug efflux transporter proteins that actively expel drug compounds. These features increase the concentration of the drug required for effective dosage, leading to increased toxicity for the patient. As a result, stromal-modulating treatments are being developed as well, with a focus on combination therapies to tackle the dense TME around tumors. VCN-01, for example, disrupts the pancreatic cancer stroma and exerts antitumor effects with other therapies [

44].

Additional novel therapeutics include viral therapies, cell therapies, and multi-specific biologics. Currently, two viral therapies are being researched. First, Theriva Biologics is developing the previously mentioned VCN-01, a systemically administered, tumor-selective, and stroma-degrading oncolytic adenovirus. Recently finishing its Phase 2b clinical trial with chemotherapy as a first-line therapy, the results showed positive outcomes [

45]. Second is Pelareorep, an intravenously delivered unmodified reovirus that contains a double-stranded RNA genome that has been previously studied in multiple cancers, such as colorectal and breast cancer. A phase 1/2 trial found that the virus, in conjunction with chemotherapy and atezolizumab, not only induces anti-reovirus T cells but also activates innate and adaptive anti-tumor immunity in pancreatic cancer patients [

46]. Cellular therapies like mesothelin-directed CAR T cell therapy and CAR-NK immunotherapy, as well as antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) like DS-3939a (tumor-associated mucin-1 directed ADC in phase 1/2 trial) and IBI343 (an anti-claudin 18.2 ADC undergoing phase 1a/b trial) [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. These advanced biologic therapies promise to improve targeted efficacy in this challenging tumor type. Finally, mRNA-based cancer vaccines are also showing promising results in phase 1 trials, showing prolonged recurrence-free survival after surgery, atezolizumab (monoclonal antibody treatment), autogene cevumeran, and chemotherapy [

52]. These advanced biologic therapies promise to improve targeted efficacy in this challenging tumor type.

Conclusion

In this paper, we outlined the discovery and early therapeutics of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, characterized the cancer via its physiology and molecular attributes, described the current diagnostic and treatment plans for this deadly cancer—including treatments like surgery, chemo, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and radiation—and ended on a brief discussion of current R&D to combat this disease with tools like improved biomarkers, therapies targeting KRAS mutations or the tumor micro-environment, targeted therapies, viral treatments, and cancer vaccines.

Treating PDAC remains a global challenge. This aggressive cancer still poses a significant threat to patients, but new and ongoing improved scientific and medical research promises to improve diagnostic and treatment tools that are urgently needed to aid patients and save lives.

Though more novel therapies are being developed to treat this disease, the most important area of research to focus on right now is improving its diagnostics. As mentioned before, resectable pancreatic tumors yield a much higher patient survival rate compared to PDAC that has reached an advanced and/or metastatic stage [

4]. By discovering and cutting the root of the cancer before it spreads, patient suffering can be relieved greatly, and much of the costs associated with late-stage therapy can be saved. Thus, it’s of utmost importance to dedicate time and resources to discovering newer and better ways of diagnosing PDAC earlier to improve patient survival rate at the lowest cost and highest efficacy. With that in mind, research devoted to discovering new therapies must continue. Only with the development of improved diagnostic tools and effective therapies can we stop PDAC and improve patients’ quality of life.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Understanding What Cancer Is: Ancient Times to Present. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/understanding-cancer/history-of-cancer/what-is-cancer.html (accessed 2025-09-18).

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2025. 1930.

- Rasheed, Z. A.; Matsui, W.; Maitra, A. Pathology of Pancreatic Stroma in PDAC. In Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment; Grippo, P. J., Munshi, H. G., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum (India), 2012.

- Hur, C.; Tramontano, A. C.; Dowling, E. C.; Brooks, G. A.; Jeon, A.; Brugge, W. R.; Gazelle, G. S.; Kong, C. Y.; Pandharipande, P. V. Early Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Survival Is Dependent on Size: Positive Implications for Future Targeted Screening. Pancreas 2016, 45 (7), 1062–1066. [CrossRef]

- Morgagni, G.; Millar, A. The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy: In Five Books, Containing a Great Variety of Dissections, with Remarks : To Which Are Added Very Accurate and Copious Indexes of the Principal Things and Names Therein Contained; Alexander, B., Translator; Printed for A. Millar and T. Cadell, his successor, in the Strand, and Johnson and Payne, in Pater-noster Row: London, 1769.

- Griffin, J. F.; Poruk, K. E.; Wolfgang, C. L. Pancreatic Cancer Surgery: Past, Present, and Future. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 27 (4), 332–348. [CrossRef]

-

Müller, J.: Ueber den feinern Bau und die Formen der krankhaften Geschwülste. Abt. 1, Lfg. 1-2. Berlin: Reimer 1838 (Fortsetzung von Nr. 178) - JPortal. https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jparticle_00237422 (accessed 2025-08-13).

- van Heerden, J. A.; Heath, P. M.; Alden, C. R. Biliary Bypass for Ductal Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas: Mayo Clinic Experience, 1970-1975. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1980, 55 (9), 537–540.

- Morohoshi, T.; Held, G.; Klöppel, G. Exocrine Pancreatic Tumours and Their Histological Classification. A Study Based on 167 Autopsy and 97 Surgical Cases. Histopathology 1983, 7 (5), 645–661. [CrossRef]

- Tannapfel, A.; Wittekind, C.; Hünefeld, G. Ductal Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas. Histopathological Features and Prognosis. Int. J. Pancreatol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Pancreatol. 1992, 12 (2), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Witzel, D. O. Beitriige zur Chirurgie der Bauchorgane.

- Saluja, A.; Dudeja, V.; Banerjee, S. Evolution of Novel Therapeutic Options for Pancreatic Cancer. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 32 (5), 401–407. [CrossRef]

- Shirasaka, T. Development History and Concept of an Oral Anticancer Agent S-1 (TS-1®): Its Clinical Usefulness and Future Vistas. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 39 (1), 2–15. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, H. L.; Alice Miller, M. The Evolution of Cancer Research and Drug Discovery at Lilly Research Laboratories. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2005, 45 (1), 229–255. [CrossRef]

- Burris, H. A.; Moore, M. J.; Andersen, J.; Green, M. R.; Rothenberg, M. L.; Modiano, M. R.; Cripps, M. C.; Portenoy, R. K.; Storniolo, A. M.; Tarassoff, P.; Nelson, R.; Dorr, F. A.; Stephens, C. D.; Von Hoff, D. D. Improvements in Survival and Clinical Benefit with Gemcitabine as First-Line Therapy for Patients with Advanced Pancreas Cancer: A Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15 (6), 2403–2413. [CrossRef]

- Taherian, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Molecular Pathology and Predictive Biomarkers. Cells 2022, 11 (19), 3068. [CrossRef]

- Raphael, B. J.; Hruban, R. H.; Aguirre, A. J.; Moffitt, R. A.; Yeh, J. J.; Stewart, C.; Robertson, A. G.; Cherniack, A. D.; Gupta, M.; Getz, G.; Gabriel, S. B.; Meyerson, M.; Cibulskis, C.; Fei, S. S.; Hinoue, T.; Shen, H.; Laird, P. W.; Ling, S.; Lu, Y.; Mills, G. B.; Akbani, R.; Loher, P.; Londin, E. R.; Rigoutsos, I.; Telonis, A. G.; Gibb, E. A.; Goldenberg, A.; Mezlini, A. M.; Hoadley, K. A.; Collisson, E.; Lander, E.; Murray, B. A.; Hess, J.; Rosenberg, M.; Bergelson, L.; Zhang, H.; Cho, J.; Tiao, G.; Kim, J.; Livitz, D.; Leshchiner, I.; Reardon, B.; Allen, E. V.; Kamburov, A.; Beroukhim, R.; Saksena, G.; Schumacher, S. E.; Noble, M. S.; Heiman, D. I.; Gehlenborg, N.; Kim, J.; Lawrence, M. S.; Adsay, V.; Petersen, G.; Klimstra, D.; Bardeesy, N.; Leiserson, M. D. M.; Bowlby, R.; Kasaian, K.; Birol, I.; Mungall, K. L.; Sadeghi, S.; Weinstein, J. N.; Spellman, P. T.; Liu, Y.; Amundadottir, L. T.; Tepper, J.; Singhi, A. D.; Dhir, R.; Paul, D.; Smyrk, T.; Zhang, L.; Kim, P.; Bowen, J.; Frick, J.; Gastier-Foster, J. M.; Gerken, M.; Lau, K.; Leraas, K. M.; Lichtenberg, T. M.; Ramirez, N. C.; Renkel, J.; Sherman, M.; Wise, L.; Yena, P.; Zmuda, E.; Shih, J.; Ally, A.; Balasundaram, M.; Carlsen, R.; Chu, A.; Chuah, E.; Clarke, A.; Dhalla, N.; Holt, R. A.; Jones, S. J. M.; Lee, D.; Ma, Y.; Marra, M. A.; Mayo, M.; Moore, R. A.; Mungall, A. J.; Schein, J. E.; Sipahimalani, P.; Tam, A.; Thiessen, N.; Tse, K.; Wong, T.; Brooks, D.; Auman, J. T.; Balu, S.; Bodenheimer, T.; Hayes, D. N.; Hoyle, A. P.; Jefferys, S. R.; Jones, C. D.; Meng, S.; Mieczkowski, P. A.; Mose, L. E.; Perou, C. M.; Perou, A. H.; Roach, J.; Shi, Y.; Simons, J. V.; Skelly, T.; Soloway, M. G.; Tan, D.; Veluvolu, U.; Parker, J. S.; Wilkerson, M. D.; Korkut, A.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Burch, P.; McWilliams, R.; Chaffee, K.; Oberg, A.; Zhang, W.; Gingras, M.-C.; Wheeler, D. A.; Xi, L.; Albert, M.; Bartlett, J.; Sekhon, H.; Stephen, Y.; Howard, Z.; Judy, M.; Breggia, A.; Shroff, R. T.; Chudamani, S.; Liu, J.; Lolla, L.; Naresh, R.; Pihl, T.; Sun, Q.; Wan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jennifer, S.; Roggin, K.; Becker, K.-F.; Behera, M.; Bennett, J.; Boice, L.; Burks, E.; Junior, C. G. C.; Chabot, J.; Tirapelli, D. P. da C.; Santos, J. S. dos; Dubina, M.; Eschbacher, J.; Huang, M.; Huelsenbeck-Dill, L.; Jenkins, R.; Karpov, A.; Kemp, R.; Lyadov, V.; Maithel, S.; Manikhas, G.; Montgomery, E.; Noushmehr, H.; Osunkoya, A.; Owonikoko, T.; Paklina, O.; Potapova, O.; Ramalingam, S.; Rathmell, W. K.; Rieger-Christ, K.; Saller, C.; Setdikova, G.; Shabunin, A.; Sica, G.; Su, T.; Sullivan, T.; Swanson, P.; Tarvin, K.; Tavobilov, M.; Thorne, L. B.; Urbanski, S.; Voronina, O.; Wang, T.; Crain, D.; Curley, E.; Gardner, J.; Mallery, D.; Morris, S.; Paulauskis, J.; Penny, R.; Shelton, C.; Shelton, T.; Janssen, K.-P.; Bathe, O.; Bahary, N.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Johns, A.; Hibshoosh, H.; Hwang, R. F.; Sepulveda, A.; Radenbaugh, A.; Baylin, S. B.; Berrios, M.; Bootwalla, M. S.; Holbrook, A.; Lai, P. H.; Maglinte, D. T.; Mahurkar, S.; Triche, T. J.; Berg, D. J. V. D.; Weisenberger, D. J.; Chin, L.; Kucherlapati, R.; Kucherlapati, M.; Pantazi, A.; Park, P.; Saksena, G.; Voet, D.; Lin, P.; Frazer, S.; Defreitas, T.; Meier, S.; Chin, L.; Kwon, S. Y.; Kim, Y. H.; Park, S.-J.; Han, S.-S.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, H.; Furth, E.; Tempero, M.; Sander, C.; Biankin, A.; Chang, D.; Bailey, P.; Gill, A.; Kench, J.; Grimmond, S.; Johns, A.; Initiative (APGI, A. P. C. G.; Postier, R.; Zuna, R.; Sicotte, H.; Demchok, J. A.; Ferguson, M. L.; Hutter, C. M.; Shaw, K. R. M.; Sheth, M.; Sofia, H. J.; Tarnuzzer, R.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J. (Julia); Felau, I.; Zenklusen, J. C. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2017, 32 (2), 185-203.e13. [CrossRef]

- STICKLER, S.; RATH, B.; HAMILTON, G. Targeting KRAS in Pancreatic Cancer. Oncol. Res. 32 (5), 799–805. [CrossRef]

- Topham, J. T.; Tsang, E. S.; Karasinska, J. M.; Metcalfe, A.; Ali, H.; Kalloger, S. E.; Csizmok, V.; Williamson, L. M.; Titmuss, E.; Nielsen, K.; Negri, G. L.; Spencer Miko, S. E.; Jang, G. H.; Denroche, R. E.; Wong, H.; O’Kane, G. M.; Moore, R. A.; Mungall, A. J.; Loree, J. M.; Notta, F.; Wilson, J. M.; Bathe, O. F.; Tang, P. A.; Goodwin, R.; Morin, G. B.; Knox, J. J.; Gallinger, S.; Laskin, J.; Marra, M. A.; Jones, S. J. M.; Schaeffer, D. F.; Renouf, D. J. Integrative Analysis of KRAS Wildtype Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Mutation and Expression-Based Similarities to Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 5941. [CrossRef]

-

microRNA-Based Liquid Biopsy Detects Early Pancreatic Cancer - NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2024/liquid-biopsy-detects-pancreatic-cancer (accessed 2025-09-18).

-

Pancreatic Cancer Stages. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/pancreatic-cancer/pancreatic-cancer-stages (accessed 2025-09-18).

- NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreat. Cancer 2025.

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Fei, H.; Zhao, D. Does Surgical Resection Significantly Prolong the Long-Term Survival of Patients with Oligometastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma? A Cross-Sectional Study Based on 18 Registries. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12 (2), 513. [CrossRef]

- Inman, S. FDA Approves Nab-Paclitaxel for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer | OncLive. https://www.onclive.com/view/fda-approves-nab-paclitaxel-for-advanced-pancreatic-cancer (accessed 2025-09-18).

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Approves Updated Drug Labeling Including New Indications and Dosing Regimens for Capecitabine Tablets under Project Renewal. FDA 2022.

- Neoptolemos, J. P.; Palmer, D. H.; Ghaneh, P.; Psarelli, E. E.; Valle, J. W.; Halloran, C. M.; Faluyi, O.; O’Reilly, D. A.; Cunningham, D.; Wadsley, J.; Darby, S.; Meyer, T.; Gillmore, R.; Anthoney, A.; Lind, P.; Glimelius, B.; Falk, S.; Izbicki, J. R.; Middleton, G. W.; Cummins, S.; Ross, P. J.; Wasan, H.; McDonald, A.; Crosby, T.; Ma, Y. T.; Patel, K.; Sherriff, D.; Soomal, R.; Borg, D.; Sothi, S.; Hammel, P.; Hackert, T.; Jackson, R.; Büchler, M. W. Comparison of Adjuvant Gemcitabine and Capecitabine with Gemcitabine Monotherapy in Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC-4): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet 2017, 389 (10073), 1011–1024. [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Approves Irinotecan Liposome for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. FDA 2024.

-

FDA Approves ONIVYDE. https://accp1.org/Members/ACCP1/5Publications_and_News/FDA_Approves_ONIVYDE.aspx (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Allen, M. J.; Zhang, A.; Bavi, P.; Kim, J. C.; Jang, G. H.; Kelly, D.; Perera, S.; Denroche, R. E.; Notta, F.; Wilson, J. M.; Dodd, A.; Ramotar, S.; Hutchinson, S.; Fischer, S. E.; Grant, R. C.; Gallinger, S.; Knox, J. J.; O’Kane, G. M. Molecular Characterisation of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma with NTRK Fusions and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 76 (3), 158–165. [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Approves Olaparib for gBRCAm Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. FDA 2019.

-

What Is Immunotherapy? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/treatment-types/immunotherapy.html (accessed 2025-10-18).

- Wolchok, J. D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.-J.; Cowey, C. L.; Lao, C. D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P. F.; Smylie, M.; Dummer, R.; Hill, A.; Hogg, D.; Haanen, J.; Carlino, M. S.; Bechter, O.; Maio, M.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Guidoboni, M.; McArthur, G.; Lebbé, C.; Ascierto, P. A.; Long, G. V.; Cebon, J.; Sosman, J.; Postow, M. A.; Callahan, M. K.; Walker, D.; Rollin, L.; Bhore, R.; Hodi, F. S.; Larkin, J. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377 (14), 1345–1356. [CrossRef]

- Garon, E. B.; Hellmann, M. D.; Rizvi, N. A.; Carcereny, E.; Leighl, N. B.; Ahn, M.-J.; Eder, J. P.; Balmanoukian, A. S.; Aggarwal, C.; Horn, L.; Patnaik, A.; Gubens, M.; Ramalingam, S. S.; Felip, E.; Goldman, J. W.; Scalzo, C.; Jensen, E.; Kush, D. A.; Hui, R. Five-Year Overall Survival for Patients With Advanced Non‒Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Pembrolizumab: Results From the Phase I KEYNOTE-001 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37 (28), 2518–2527. [CrossRef]

-

Immunotherapy: For Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Research Institute. https://www.cancerresearch.org/immunotherapy-by-cancer-type/pancreatic-cancer (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Akhunzianov, A. A.; Rozhina, E. V.; Filina, Y. V.; Rizvanov, A. A.; Miftakhova, R. R. Resistance to Radiotherapy in Cancer. Diseases 2025, 13 (1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.; Fekrmandi, F.; Malik, N.; Hatoum, H.; George, S.; Goldberg, R. M.; Mukherjee, S. The Evolving Role of Radiation in Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1060885. [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Pfeiffer, P.; Vilgrain, V.; Lamarca, A.; Seufferlein, T.; O’Reilly, E. M.; Hackert, T.; Golan, T.; Prager, G.; Haustermans, K.; Vogel, A.; Ducreux, M. Pancreatic Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up☆. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34 (11), 987–1002. [CrossRef]

- Madadjim, R.; An, T.; Cui, J. MicroRNAs in Pancreatic Cancer: Advances in Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25 (7), 3914. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P.; Wu, T.; Guo, S.; Du, L.; Xue, D.; Shen, S.; Sun, F.; Hu, J.; Zheng, L.; Wu, X.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Jin, G.; Chen, L. Cell-Free DNA Testing for the Detection and Prognosis Prediction of Pancreatic Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16 (1), 6645. [CrossRef]

- Revolution Medicines, Inc. A Multicenter Open-Label Study of RMC-6236 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors Harboring Specific Mutations in RAS; Clinical trial registration NCT05379985; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05379985 (accessed 2025-09-28).

-

A phase II study of siG12D-LODER in combination with chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (PROTACT). - ASCO. https://www.asco.org/abstracts-presentations/ABSTRACT306267 (accessed 2025-09-28).

-

A Phase 2 Study of siG12D LODER in Combination With Chemotherapy in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer - NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/research/participate/clinical-trials-search/v?id=NCI-2018-00398 (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Grants Accelerated Approval to Zenocutuzumab-Zbco for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. FDA 2024.

- Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Laquente, B.; Álvarez, R.; Mato-Berciano, A.; Gimenez-Alejandre, M.; Morgado, S.; Rodríguez-García, A.; Maliandi, M. V.; Riesco, M. C.; Moreno, R.; Ginestà, M. M.; Perez-Carreras, M.; Gornals, J. B.; Prados, S.; Perea, S.; Capella, G.; Alemany, R.; Salazar, R.; Blasi, E.; Blasco, C.; Cascallo, M.; Hidalgo, M. VCN-01 Disrupts Pancreatic Cancer Stroma and Exerts Antitumor Effects. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9 (11), e003254. [CrossRef]

-

TherivaTM Biologics Announces Primary Endpoints for Efficacy and Safety Achieved in VIRAGE Phase 2b Clinical Trial of VCN-01 with Gemcitabine/nab-Paclitaxel in Newly-Diagnosed Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Patients | TherivaTM Biologics. https://therivabio.com/press_releases/theriva-biologics-announces-primary-endpoints-for-efficacy-and-safety-achieved-in-virage-phase-2b-clinical-trial-of-vcn-01-with-gemcitabine-nab-paclitaxel-in-newly-diagnosed-metastatic-pancre/ (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Trauger, R.; Vile, R.; Siveke, J. T.; Liffers, S.-T.; Heineman, T. C.; Coffey, M. Role of Pelareorep in Activating Anti-Tumor Immunity in PDAC. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (16_suppl), 2562–2562. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M. A. A.; Good, C. R.; Barber-Rotenberg, J. S.; Agarwal, S.; Wilson, W.; Gonzales, D.; Watts, A. C.; Hwang, W.-T.; Jadlowsky, J. K.; Young, R. M.; Berger, S. L.; June, C. H.; O’Hara, M. H. 237 Enhancing Mesothelin-Directed CAR T Cell Therapy for Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12 (Suppl 2). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, B.; Deng, M.; Wang, W.; Mi, X.; Sun, Z.; Ge, X. Breakthrough of Solid Tumor Treatment: CAR-NK Immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10 (1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Daiichi Sankyo. Phase 1/2, Open-Label, Multicenter, First-in-Human Study of DS-3939a in Subjects With Advanced Solid Tumors; Clinical trial registration NCT05875168; clinicaltrials.gov, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05875168 (accessed 2025-09-28).

-

Safety and efficacy of IBI343 (anti-claudin18.2 antibody-drug conjugate) in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or biliary tract cancer: Preliminary results from a phase 1 study. | Journal of Clinical Oncology. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.3037 (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Innovent Biologics (Suzhou) Co. Ltd. A Phase 1a/b, Multicenter, Open-Label, First-in-Human Study of IBI343 in Subjects With Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Solid Tumors; Clinical trial registration NCT05458219; clinicaltrials.gov, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05458219 (accessed 2025-09-28).

- Sethna, Z.; Guasp, P.; Reiche, C.; Milighetti, M.; Ceglia, N.; Patterson, E.; Lihm, J.; Payne, G.; Lyudovyk, O.; Rojas, L. A.; Pang, N.; Ohmoto, A.; Amisaki, M.; Zebboudj, A.; Odgerel, Z.; Bruno, E. M.; Zhang, S. L.; Cheng, C.; Elhanati, Y.; Derhovanessian, E.; Manning, L.; Müller, F.; Rhee, I.; Yadav, M.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J. D.; Basturk, O.; Gönen, M.; Epstein, A. S.; Momtaz, P.; Park, W.; Sugarman, R.; Varghese, A. M.; Won, E.; Desai, A.; Wei, A. C.; D’Angelica, M. I.; Kingham, T. P.; Soares, K. C.; Jarnagin, W. R.; Drebin, J.; O’Reilly, E. M.; Mellman, I.; Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö.; Greenbaum, B. D.; Balachandran, V. P. RNA Neoantigen Vaccines Prime Long-Lived CD8+ T Cells in Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2025, 639 (8056), 1042–1051. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).