Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- i.

- It is among the first to empirically investigate the direct and dynamic impact of institutional quality on DFI at a global scale.

- ii.

- It conducts a systematic analysis across regions and income groups, unveiling context-specific institutional pathways.

- iii.

- It estimates long-run effects, highlighting the sustained influence of governance structures on digital financial development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Empirical Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sources

3.2. Econometric Model

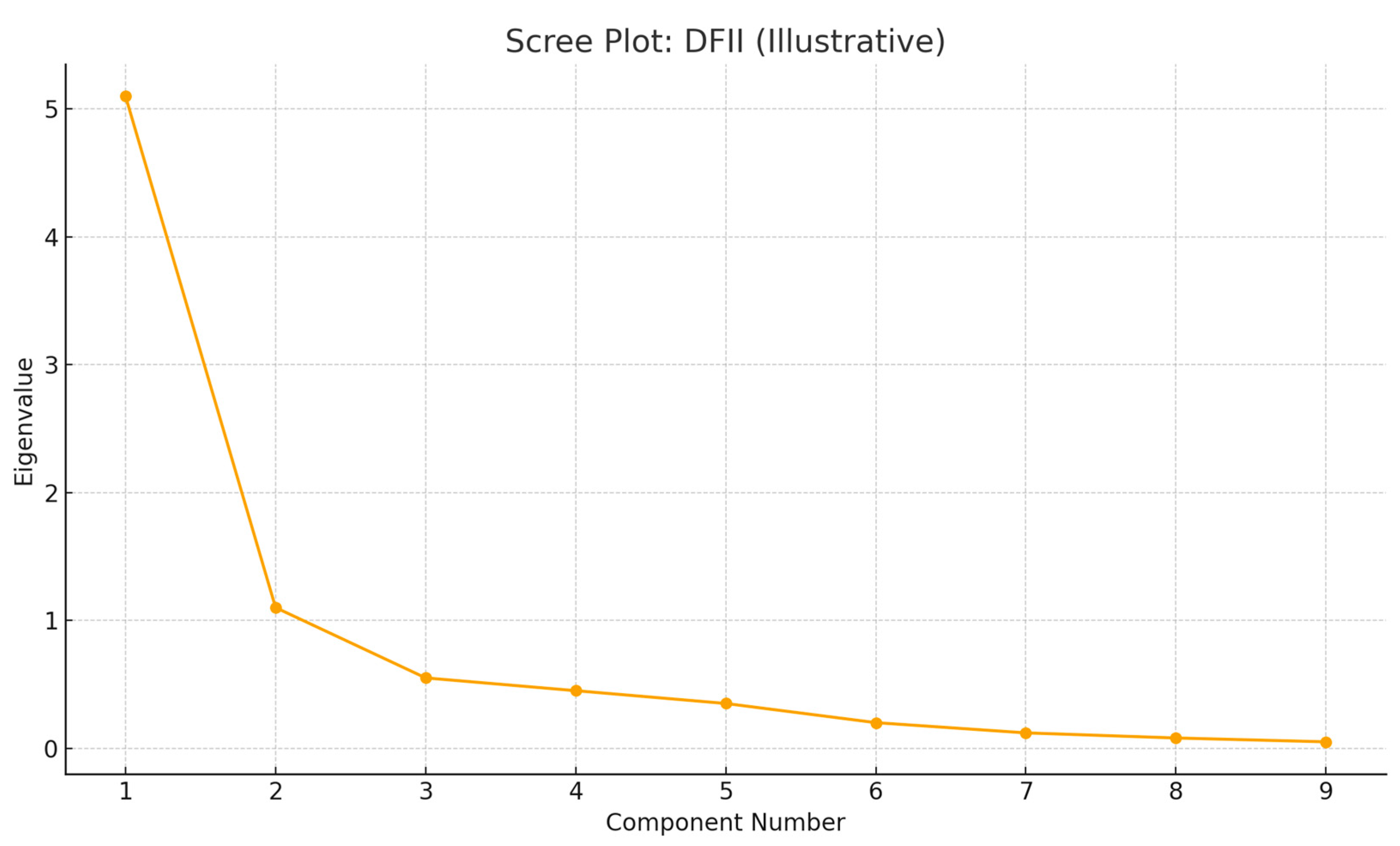

3.3. Principal Component Analysis and Variable Definitions

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Symbol | Definition and Measurement | Source |

| Dependent Variable | Digital Financial Inclusion Index | DFII | Composite index derived using PCA from nine components across three dimensions of digital financial inclusion: | Constructed using PCA |

| Access Dimension | ||||

| Internet Penetration | INTP | % of individuals using the internet. | WDI | |

| Mobile Phone for Transactions | MP | % of respondents using mobile phones to send money in the past year. | Findex | |

| Account Ownership | AO | % of individuals aged 15+ with an account at a formal financial institution or mobile money provider. | Findex | |

| Usage Dimension | ||||

| Debit Card Ownership | DC | % of adults (15+) holding a debit card. | Findex | |

| Mobile Money Transactions | MMT | Number of active mobile money accounts used for digital payments. | WDI | |

| Credit Card Ownership | CD | % of adults (15+) holding a credit card. | Findex | |

| Quality Dimension | ||||

| Secure Internet Servers | SIS | Number of secure internet servers per million people, proxy for cybersecurity. | WDI | |

| Automated Teller Machines | ATM | Number of ATMs per 100,000 adults, proxy for financial infrastructure. | WDI | |

| Borrowers from Commercial Banks | BCB | Number of borrowers from commercial banks per 1,000 adults, proxy for lending accessibility. | WDI | |

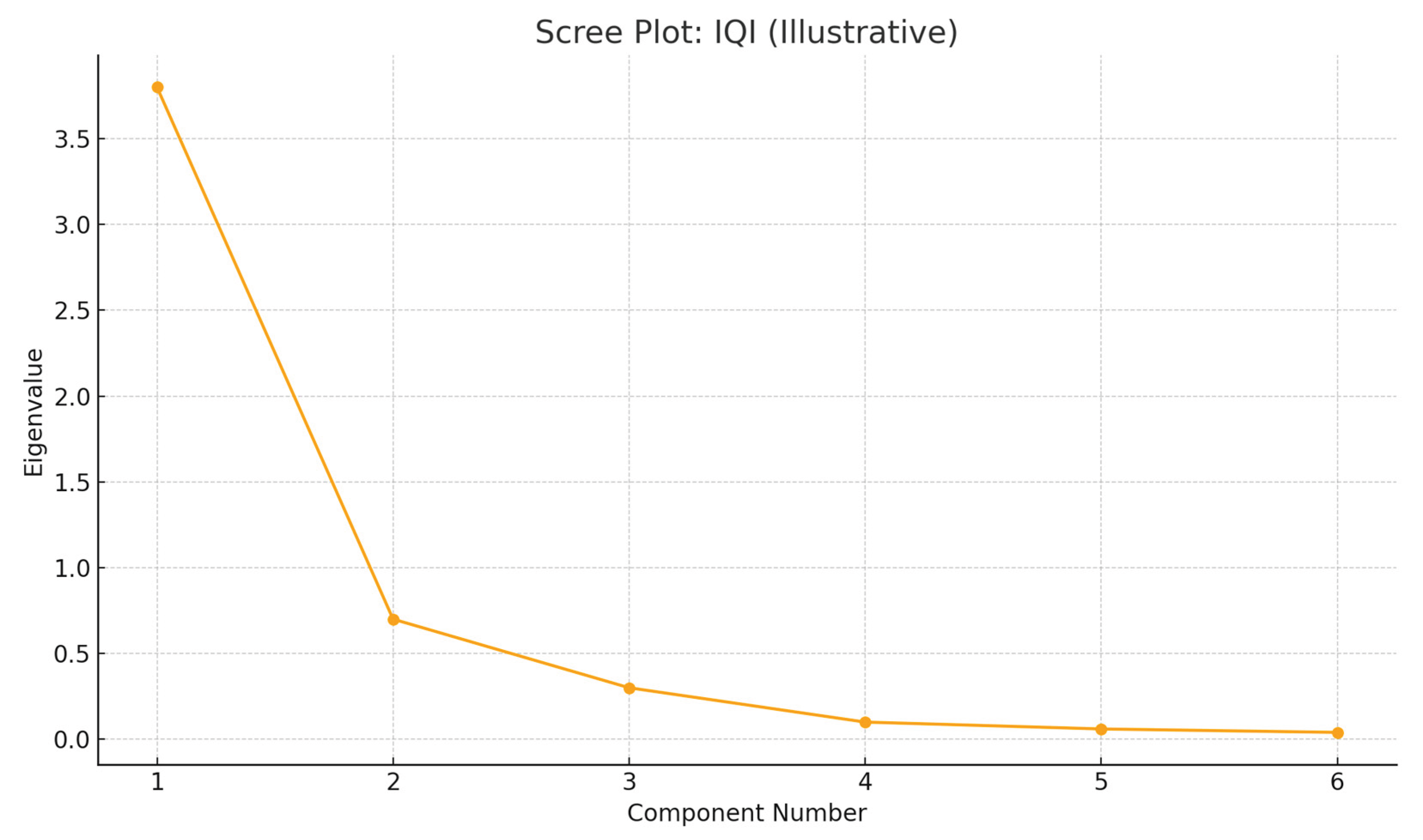

| Independent Variable | Institutional Quality Index | IQI | Composite index constructed via PCA from six governance indicators. | Authors' computation using PCA |

| Government Effectiveness | GE | Perceptions of quality of public services and civil service. | WGI | |

| Regulatory Quality | RQ | Perceptions of government’s ability to implement sound policies for private sector development. | WGI | |

| Rule of Law | RL | Perceptions of confidence in and compliance with societal rules. | WGI | |

| Control of Corruption | CC | Perceptions of extent to which public power is exercised for private gain. | WGI | |

| Voice and Accountability | VA | Perceptions of citizen participation, freedom of expression, and association. | WGI | |

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism | PSAVT | Perceptions of likelihood of political instability and politically-motivated violence. | WGI | |

| Control Variables | GDP per Capita | GDPPC | Economic development, measured in current US dollars. | WDI |

| Financial Literacy | FL | Adult literacy rate (% of population aged 15+), proxy for financial literacy. | WDI | |

| Urban Population | UP | % of total population living in urban areas. | WDI | |

| Trade Openness | TO | Sum of exports and imports as % of GDP, proxy for economic integration. | WDI |

3.4. Estimation Technique and Robustness Check

4. Empirical Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Matrix

4.3. Baseline Estimation Results

4.4. Heterogeneous Impact of Institutional Quality on Digital Financial Inclusion Across Continents

4.5. Heterogeneous Impact of Institutional Quality on Digital Financial Inclusion Across Income Groups

8. Robustness Test

5. Conclusion, Policy Implications, and Recommendations for Future Research

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Recommendations for Future Research

- Explore the mediating role of fintech development in the IQI and DFI relationship

- Investigate micro-level behavioural barriers to DFI in weak institutional settings

- Incorporate machine learning techniques to model non-linear interactions between institutions, innovation, and inclusion. By addressing these policy implications and pursuing these avenues for future research, the global community can collectively promote the agenda of digital financial inclusion, ensuring that the benefits of DFI are equitably distributed through strong institutional quality and contribute to sustainable development worldwide.

Appendix A

| Component | Eigenvalue | % Variance Explained | Cumulative % |

| PC1 | 5.1 | 63.75 | 63.75 |

| PC2 | 1.1 | 13.75 | 77.5 |

| PC3 | 0.55 | 6.88 | 84.38 |

| PC4 | 0.45 | 5.63 | 90.0 |

| PC5 | 0.35 | 4.38 | 94.38 |

| PC6 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 96.88 |

| PC7 | 0.12 | 1.5 | 98.38 |

| PC8 | 0.08 | 1.0 | 99.38 |

| PC9 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 100.0 |

| Component | Eigenvalue | % Variance Explained | Cumulative % |

| PC1 | 3.8 | 76.0 | 76.0 |

| PC2 | 0.7 | 14.0 | 90.0 |

| PC3 | 0.3 | 6.0 | 96.0 |

| PC4 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 98.0 |

| PC5 | 0.06 | 1.2 | 99.2 |

| PC6 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 100.0 |

References

- Abaidoo, R.; Agyapong, E.K. Financial development and institutional quality among emerging economies; Journal of Economics and Development, 2022; Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Adel, N. The impact of digital literacy and technology adoption on financial inclusion in Africa, Asia, and Latin America; Heliyon, 2024; Vol. 10, No. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Majeed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sohaib, M.; Shehzad, K. Digital financial inclusion and economic growth: Provincial data analysis of China; China Economic Journal, 2021; Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Amnas, M.B.; Selvam, M.; Parayitam, S. FinTech and financial inclusion: Exploring the mediating role of digital financial literacy and the moderating influence of perceived regulatory support; Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 2024; Vol. 17, No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M.A.A.; Sajid, M.; Khan, S.N.; Antohi, V.M.; Fortea, C.; Zlati, M.L. Unveiling the effect of renewable energy and financial inclusion towards sustainable environment: Does interaction of digital finance and institutional quality matter? Sustainable Futures, 2024; Vol. 7, p. 100196. [Google Scholar]

- Aracil, E.; Gómez-Bengoechea, G.; Moreno-de-Tejada, O. Institutional quality and the financial inclusion-poverty alleviation link: Empirical evidence across countries; Borsa Istanbul Review, 2022; Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models; Journal of Econometrics, 1995; Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, H.M.; Ayinde, L.A. Uneven progress: Analysing the factors behind digital technology adoption rates in Sub-Saharan Africa; Data & Policy, 2025; Vol. 7, p. Article e23. [Google Scholar]

- Baafi, J.A.; Asiedu, M.K. The synergistic effects of remittances, savings, education and digital financial technology on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics, 2025.

- Ben Abdallah, A.; Becha, H.; Kalai, M.; Helali, K. Does digital financial inclusion affect economic growth? New insights from MENA region. International Conference on Digital Economy; Springer; Cham, 2023; pp. 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, S.; Teevan, C.; Tilmes, K. Financing inclusive digital transformation under the EU Global Gateway. In ECDPM Discussion Paper 370; Maastricht; ECDPM, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models; Journal of Econometrics, 1998; Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chinoda, T.; Kapingura, F.M. Digital financial inclusion and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: The role of institutions and governance; African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 2024; Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Doku, J.N.; Iddrisu, K.; Bortey, D.N.; Ladime, J. Impact of digital financial technology on financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa: The moderating role of institutional quality; African Finance Journal, 2023; Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, S.; Ríos Camacho, E.; Heidebrecht, S. Digital sovereignty as control: The regulation of digital finance in the European Union; Journal of European Public Policy, 2024; Vol. 31, No. 8, pp. 2226–2249. [Google Scholar]

- Garz, S.; Giné, X.; Karlan, D.; Mazer, R.; Sanford, C.; Zinman, J. Consumer protection for financial inclusion in low- and middle-income countries: Bridging regulator and academic perspectives; Annual Review of Financial Economics, 2021; Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 219–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr.; Anderson, R. E.; Tatham, R. L.; Black, W. C. Multivariate Data Analysis. In New York. NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 3rd Edn. ed; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, R.; Ashfaq, M.; Parveen, T.; Gunardi, A. Financial inclusion – Does digital financial literacy matter for women entrepreneurs? International Journal of Social Economics, 2023; Vol. 50, No. 8, pp. 1085–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H. F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and psychological measurement 1960, 20(1), 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, E.J. Interaction of financial and regulatory innovation; The American Economic Review, 1988; Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Konadu-Yiadom, E.; Domeher, D.; Appiah, K.O.; Frimpong, J.M. Digital finance, institutional quality, and carbon dioxide emissions in Africa. Climate and Development 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Quoc, D. The relationship between digital financial inclusion, gender-inequality, and economic growth: Dynamics from financial development; Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 2024; Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 370–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. How does financial development environment affect regional innovation capabilities? New perspectives from digital finance and institutional quality; Journal of Information Economics, 2023; Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Meniago, C. Digital financial inclusion and economic growth: The moderating role of institutions in SADC countries; International Journal of Financial Studies, 2025; Vol. 13, No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, T.P.; White, I.R.; Royston, P. Tuning multiple imputation by predictive mean matching and local residual draws; BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2014; Vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Muriu, P.W. Role of institutional quality in promoting financial inclusion, 2020; unpublished.

- Nasreen, S.; Ishtiaq, F.; Tiwari, A.K. The role of ICT diffusion and institutional quality on financial inclusion in Asian region: Empirical analysis using panel quantile regression. Electronic Commerce Research 2023, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.H.D.; Ha, D.T.T. The effect of institutional quality on financial inclusion in ASEAN countries; The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 2021; Vol. 8, No. 8, pp. 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Nsiah, A.Y.; Tweneboah, G. Determinants of financial inclusion in Africa: Is institutional quality relevant? Cogent Social Sciences, 2023; Vol. 9, No. 1, p. 2184305. [Google Scholar]

- Ofosu-Mensah Ababio, J.; Boachie Yiadom, E.; Ofori-Sasu, D.; Sarpong–Kumankoma, E. Digital financial inclusion and inclusive development in lower-middle-income countries: The enabling role of institutional quality; Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 2024; Vol. 17 Nos. 2/3, pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ozili, P.K. Digital financial inclusion, in Big Data: A Game Changer for Insurance Industry; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2022; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, L.Y.; Tai, H.T.; Tan, G.S. Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development; Heliyon, 2022; Vol. 8, No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Van, L.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, H.L.P.; Vo, D.H. The asymmetric effects of institutional quality on financial inclusion in the Asia-Pacific region; Heliyon, 2022; Vol. 8, No. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, D.H. Does institutional quality matter for financial inclusion? International evidence; PLOS ONE, 2024; Vol. 19, No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, D.H. Long-term effects of institutional quality on financial inclusion in Asia–Pacific countries; Financial Innovation, 2025; Vol. 11, No. 1, p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, V.; Jain, P. Role of digital economy and technology adoption for financial inclusion in India; Indian Growth and Development Review, 2021; Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 302–324. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; He, T.; Li, Z. Digital inclusive finance, economic growth and innovative development; Kybernetes, 2023; Vol. 52, No. 9, pp. 3064–3084. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank country classifications by income level for 2024–2025, World Bank Blogs. 2024. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025</u> (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators, Washington, DC. 2024. Available online: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- World Bank. Digital financial inclusion, Washington, DC. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/publication/digital-financial-inclusion (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Zeqiraj, V.; Sohag, K.; Hammoudeh, S. Financial inclusion in developing countries: Do quality institutions matter? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 2022; Vol. 81, p. Article 101677. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| DFII | 3,819 | -0.017 | 1.211 | -2.455 | 3.170 | 0.310 | 2.852 |

| L.DFII | 3,628 | -0.019 | 1.211 | -2.455 | 3.170 | 0.312 | 2.834 |

| IQI | 3,819 | -0.008 | 0.977 | -1.547 | 2.621 | 0.342 | 2.514 |

| CC | 3,819 | 43.866 | 31.358 | 0.296 | 98.572 | 0.135 | 1.624 |

| PSAVT | 3,819 | 16.499 | 16.846 | 0.000 | 60.745 | 0.985 | 2.931 |

| VA | 3,819 | 4.489 | 6.328 | -9.985 | 18.706 | 0.138 | 3.147 |

| L.RQ | 3,628 | 13.091 | 21.034 | -2.098 | 67.067 | 1.253 | 2.967 |

| RL | 3,819 | 1.808 | 3.001 | -1.717 | 7.289 | 0.974 | 2.469 |

| GE | 3,819 | -0.012 | 0.998 | -2.402 | 1.945 | -0.515 | 2.697 |

| L.GDPPC | 3,628 | -0.019 | 0.937 | -1.259 | 2.652 | 0.777 | 3.198 |

| FL | 3,819 | -0.225 | 0.281 | -0.411 | 0.309 | 1.186 | 2.62 |

| UP | 3,819 | -0.031 | 1.292 | -2.230 | 3.553 | 0.715 | 2.915 |

| TO | 3,819 | 25.737 | 19.604 | 0.000 | 65.125 | 0.125 | 1.817 |

| Variables | VIF | DFII | IQI | CC | PSAVT | VA | L.RQ | RL | GE | L.GDPPC | FLI | UP | TO | ||

| DFII | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| IQI | 1.35 | 0.680 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| CC | 1.71 | 0.277 | 0.261 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| PSAVT | 1.88 | 0.296 | 0.223 | 0.551 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| VA | 1.03 | -0.024 | -0.021 | -0.075 | -0.073 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| L.RQ | 2.16 | 0.018 | -0.003 | 0.038 | -0.031 | -0.015 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| RL | 2.50 | 0.136 | 0.051 | 0.159 | 0.153 | -0.045 | 0.676 | 1.000 | |||||||

| GE | 2.05 | 0.334 | 0.140 | 0.438 | 0.527 | 0.001 | 0.313 | 0.517 | 1.000 | ||||||

| L.GDPPC | 1.20 | 0.773 | 0.387 | 0.166 | 0.168 | -0.017 | 0.031 | 0.061 | 0.157 | 1.000 | |||||

| FL | 1.11 | 0.201 | 0.072 | 0.007 | 0.140 | -0.048 | -0.156 | -0.061 | 0.086 | 0.051 | 1.000 | ||||

| UP | 1.51 | -0.401 | -0.256 | 0.047 | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.434 | 0.320 | 0.199 | -0.148 | -0.229 | 1.000 | |||

| TO | 1.53 | 0.010 | 0.029 | 0.096 | 0.024 | -0.093 | -0.430 | -0.494 | -0.252 | 0.009 | 0.119 | -0.366 | 1.000 | ||

| VARIABLES | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| L.DFII | 0.375*** | 0.375*** | 0.385*** | 0.384*** |

| (0.0571) | (0.0568) | (0.0584) | (0.0581) | |

| IQI | 0.239*** | 0.237*** | 0.232*** | 0.229*** |

| (0.0268) | (0.0267) | (0.0273) | (0.0271) | |

| CC | 0.00373*** | 0.00380*** | 0.00751*** | 0.00762*** |

| (0.00107) | (0.00108) | (0.00194) | (0.00195) | |

| PSAVT | -0.00269* | -0.00246 | -0.00702*** | -0.00676*** |

| (0.00150) | (0.00150) | (0.00243) | (0.00241) | |

| VA | 0.00249* | 0.00246 | 0.00280* | 0.00277* |

| (0.00151) | (0.00151) | (0.00152) | (0.00152) | |

| L.RQ | 0.00401*** | 0.00376*** | 0.00460*** | 0.00428*** |

| (0.000739) | (0.000766) | (0.000779) | (0.000801) | |

| RL | -0.0109** | -0.0131*** | -0.0114** | -0.0144*** |

| (0.00471) | (0.00473) | (0.00479) | (0.00500) | |

| GE | 0.225*** | 0.220*** | 0.203*** | 0.197*** |

| (0.0290) | (0.0292) | (0.0306) | (0.0308) | |

| L.GDPPC | 0.429*** | 0.430*** | 0.424*** | 0.425*** |

| (0.0398) | (0.0397) | (0.0409) | (0.0408) | |

| FL | 0.149*** | 0.150*** | 0.0951** | 0.0953** |

| (0.0393) | (0.0391) | (0.0379) | (0.0378) | |

| UP | -0.257*** | -0.258*** | -0.258*** | -0.259*** |

| (0.00963) | (0.00954) | (0.00958) | (0.00947) | |

| TO | -0.00260*** | -0.00204*** | -0.00269*** | -0.00196*** |

| (0.000653) | (0.000731) | (0.000646) | (0.000721) | |

| Country FE | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | -0.0688* | -0.133** | 48.22*** | 48.47*** |

| (0.0363) | (0.0546) | (13.09) | (13.14) | |

| Observations | 3,628 | 3,628 | 3,628 | 3,628 |

| Number of Countries | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 |

| No. of Instruments | 19 | 20 | 20 | 21 |

| AR(2) p-value | 0.079 | 0.082 | 0.098 | 0.107 |

| Sargan p-value | 0.397 | 0.414 | 0.524 | 0.544 |

| Hansen p-value | 0.161 | 0.174 | 0.272 | 0.295 |

| Wald Chi2 (12) | 8179.82 | 8497.99 | 7341.05 | 7520.98 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (GMM) p | 0.110 | 0.121 | 0.198 | 0.219 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (IV) p | 0.617 | 0.601 | 0.622 | 0.609 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| VARIABLES | Africa | Asia | Europe | North America |

| L.DFII | 0.217*** | 0.195*** | 0.318*** | 0.160*** |

| (0.0442) | (0.0480) | (0.0766) | (0.0458) | |

| IQI | 0.239*** | 0.185*** | 0.268*** | 0.386*** |

| (0.0348) | (0.0424) | (0.0398) | (0.0421) | |

| CC | 0.00590*** | -0.000193 | 0.00169 | 0.00320** |

| (0.00180) | (0.00206) | (0.00198) | (0.00161) | |

| PSAVT | -0.00162 | -0.00220 | -0.000722 | -0.0154*** |

| (0.00315) | (0.00413) | (0.00281) | (0.00495) | |

| VA | 0.000972 | 0.00331 | 0.00369* | -0.00177 |

| (0.00339) | (0.00329) | (0.00208) | (0.00282) | |

| L.RQ | 0.00702*** | 0.00489*** | 0.00275** | 0.00927 |

| (0.00138) | (0.00183) | (0.00129) | (0.00722) | |

| RL | -0.0205* | -0.0219* | -0.0147 | -0.0510 |

| (0.0107) | (0.0133) | (0.00929) | (0.0354) | |

| GE | 0.244*** | 0.358*** | 0.234*** | 0.588*** |

| (0.0475) | (0.0631) | (0.0522) | (0.0883) | |

| L.GDPPC | 0.581*** | 0.721*** | 0.444*** | 0.399*** |

| (0.0639) | (0.0606) | (0.0478) | (0.102) | |

| FL | 0.214*** | 0.576** | 0.0383 | 0.525*** |

| (0.0665) | (0.243) | (0.0557) | (0.119) | |

| UP | -0.370*** | -0.374*** | -0.279*** | -0.240*** |

| (0.0462) | (0.0701) | (0.0174) | (0.0207) | |

| TO | -0.00354* | -0.00400 | -0.00258* | -0.00129 |

| (0.00185) | (0.00286) | (0.00147) | (0.00208) | |

| Constant | -0.190*** | 0.306*** | -0.310*** | 0.432*** |

| (0.0560) | (0.0850) | (0.0641) | (0.103) | |

| Observations | 1,026 | 798 | 817 | 380 |

| Number of Countries | 54 | 42 | 43 | 20 |

| No. of Instruments | 16 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| AR(2) p-value | 0.321 | 0.766 | 0.599 | 0.350 |

| Sargan p-value | 0.488 | 0.556 | 0.164 | 0.083 |

| Hansen p-value | 0.192 | 0.768 | 0.177 | 0.122 |

| Wald Chi2 (12) | 2861.28 | 2530.00 | 2655.47 | 2354.61 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (GMM) p | 0.336 | 0.869 | 0.196 | 0.086 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (IV) p | 0.110 | 0.253 | 0.204 | 0.464 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| VARIABLES |

Low-Income Group |

Lower-Middle Income Group |

Upper-Income Group |

High-Income Group |

| L.DFII | 0.400*** | 0.305*** | 0.353*** | 0.398*** |

| (0.0874) | (0.0760) | (0.0697) | (0.0680) | |

| IQI | 0.154*** | 0.286*** | 0.282*** | 0.233*** |

| (0.0314) | (0.0355) | (0.0449) | (0.0317) | |

| CC | 0.00740*** | 0.00212* | 0.00187 | 0.00158 |

| (0.00262) | (0.00119) | (0.00156) | (0.00202) | |

| PSAVT | -0.00293 | -0.00390* | 3.38e-05 | -0.00196 |

| (0.00440) | (0.00214) | (0.00217) | (0.00285) | |

| VA | -0.00622 | -1.53e-06 | 0.00512*** | 0.00453** |

| (0.00426) | (0.00290) | (0.00187) | (0.00222) | |

| L.RQ | 0.00705*** | 0.00454*** | 0.00303*** | 0.00580*** |

| (0.00240) | (0.00106) | (0.000897) | (0.00184) | |

| RL | -0.0209 | -0.00855 | -0.00623 | -0.0218* |

| (0.0186) | (0.00836) | (0.00552) | (0.0114) | |

| GE | 0.164** | 0.259*** | 0.196*** | 0.244*** |

| (0.0646) | (0.0346) | (0.0363) | (0.0438) | |

| L.GNIPC | 0.445*** | 0.524*** | 0.426*** | 0.379*** |

| (0.0632) | (0.0578) | (0.0535) | (0.0506) | |

| FL | 0.118 | 0.202*** | 0.183** | 0.0552 |

| (0.102) | (0.0569) | (0.0716) | (0.0549) | |

| UP | -0.267*** | -0.260*** | -0.265*** | -0.271*** |

| (0.0226) | (0.0162) | (0.0127) | (0.0180) | |

| TO | -0.00381** | -0.000132 | -0.00269*** | -0.00221** |

| (0.00153) | (0.00108) | (0.00992) | (0.00101) | |

| Constant | -0.251*** | -0.0325* | -0.0495* | 0.0388* |

| (0.0811) | (0.0519) | (0.0540) | (0.0730) | |

| Observations | 589 | 817 | 1,006 | 1,083 |

| Number of Countries | 31 | 43 | 53 | 57 |

| No. of Instruments | 16 | 19 | 16 | 18 |

| AR (2) p-value | 0.629 | 0.824 | 0.391 | 0.157 |

| Sargan p-value | 0.579 | 0.791 | 0.097 | 0.441 |

| Hansen p-value | 0.381 | 0.268 | 0.065 | 0.209 |

| Wald Chi2 (12) | 2896.44 | 8030.77 | 6885.79 | 2696.25 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (GMM) p | 0.937 | 0.918 | 0.063 | 0.130 |

| Diff-in-Hansen (IV) p | 0.087 | 0.093 | 0.334 | 0.804 |

| (1) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| VARIABLES | OLS | FGLS | FE | RE | One-step Sys. GMM |

| L.DFII | 0.251*** | 0.251*** | 0.183*** | 0.251*** | 0.387*** |

| (0.00811) | (0.00809) | (0.00784) | (0.00811) | (0.0602) | |

| IQI | 0.352*** | 0.352*** | 0.281*** | 0.352*** | 0.224*** |

| (0.00781) | (0.00780) | (0.0105) | (0.00781) | (0.0272) | |

| CC | 0.00106*** | 0.00106*** | 0.000747* | 0.00106*** | 0.00541*** |

| (0.000341) | (0.000340) | (0.000446) | (0.000341) | (0.00207) | |

| PSAVT | -0.000764 | -0.000764 | -0.000712 | -0.000764 | -0.00506** |

| (0.000544) | (0.000543) | (0.00108) | (0.000544) | (0.00252) | |

| VA | 0.00229** | 0.00229** | 0.00167 | 0.00229** | 0.00275* |

| (0.000930) | (0.000928) | (0.00112) | (0.000930) | (0.00152) | |

| L.RQ | 0.00248*** | 0.00248*** | 0.00222*** | 0.00248*** | 0.00503*** |

| (0.000430) | (0.000430) | (0.000554) | (0.000430) | (0.000855) | |

| RL | 0.0138*** | 0.0138*** | 0.0182*** | 0.0138*** | -0.0113** |

| (0.00322) | (0.00322) | (0.00420) | (0.00322) | (0.00517) | |

| GE | 0.184*** | 0.184*** | 0.123*** | 0.184*** | 0.196*** |

| (0.00859) | (0.00857) | (0.0222) | (0.00859) | (0.0291) | |

| L.GDPPC | 0.557*** | 0.557*** | 0.695*** | 0.557*** | 0.424*** |

| (0.00829) | (0.00828) | (0.0105) | (0.00829) | (0.0409) | |

| FL | 0.245*** | 0.245*** | 0.244*** | 0.245*** | 0.500*** |

| (0.0227) | (0.0227) | (0.0232) | (0.0227) | (0.0807) | |

| UP | -0.234*** | -0.234*** | -0.241*** | -0.234*** | -0.252*** |

| (0.00564) | (0.00563) | (0.00602) | (0.00564) | (0.00965) | |

| TO | -0.00143*** | -0.00143*** | -0.00166** | -0.00143*** | -0.00303*** |

| (0.000364) | (0.000364) | (0.000649) | (0.000364) | (0.000657) | |

| Year Dummies | -0.00395** | -0.00395** | -0.00290* | -0.00395** | -0.0128* |

| (0.00157) | (0.00157) | (0.00173) | (0.00157) | (0.00708) | |

| Constant | 7.934** | 7.934** | 5.849* | 7.934** | 25.75* |

| (3.153) | (3.147) | (3.480) | (3.153) | (14.19) | |

| Observations | 3,628 | 3,628 | 3,628 | 3,628 | 3,628 |

| Number of Countries | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 |

| R-squared | 0.917 | 0.838 | 0.831 | ||

| Adj. R-squared | 0.916 | ||||

| No. of Instruments | 20 | ||||

| AR(2) p-value | 0.071 | ||||

| Sargan p-value | 0.270 | ||||

| Hansen p-value | 0.134 | ||||

| Wald Chi2 (13) | 7026.25 | ||||

| Diff-in-Hansen (GMM) p | 0.183 | ||||

| Diff-in-Hansen (IV) p | 0.835 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).