1. Introduction

Optic neuritis, the most common cause of acute optic neuropathy in the young, is defined as inflammatory disease of the optic nerve. It’s etiologies can be the typical demyelinating disorders like multiple sclerosis, but it can also occur as atypical presentation such as Neuromyelitis optica, Neuromyelitis optic spectrum disorder, Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-IgG associated disorder, Sarcoidosis, Sjogren’s disease, Systemic Lupus Erythematosis (SLE), bacterial and viral infectious processes[

1,

2,

3] The classical presentation includes acute, unilateral, painful, partial to complete vision loss, often accompanied by red color desaturation and a relative afferent pupillary defect.[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] Bilateral involvement, atypical age of onset, and associated systemic findings should prompt evaluation for alternative etiologies, including infectious and autoimmune processes.[

2,

3]

Optic neuritis occurring after infection has been linked to a diverse array of viruses including adenovirus; Coxsackie virus; herpesviruses such as varicella zoster, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus, and herpes simplex; as well as measles, mumps, rubella, influenza, West Nile, dengue, and even HIV—while post-vaccination or post-infection cases associated with hepatitis A or B are notably rare. [

4] Hepatitis C is well known to cause various neurological complications—most frequently a peripheral neuropathy associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia. However, central nervous system involvement, including optic neuropathy, has also been documented in rare cases, typically resulting from immune complex deposition, cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis, or direct viral-triggered immune dysregulation.[

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] Optic neuritis has been infrequently reported in patients with active or treated HCV infection, sometimes in association with interferon-alpha therapy, which is known to unmask or exacerbate autoimmune conditions.[

4,

7,

9] Our case report describes an atypical presentation of bilateral optic neuritis in a patient with active, untreated HCV infection. It is an unusual presentation, highlighting how infectious and demyelinating conditions can intersect—reminding clinicians to broaden their diagnostic possibilities.

Chronic HCV infection affects an estimated 71 million people globally, of which 74% patients reporting extrahepatic complications with neurological and ophthalmologic involvement being less common but clinically significant.[

10]. Both extrahepatic and hepatic complications causing significant contribution to mortality and morbidity in these patients. [

10,

11] Advanced age, Female sex, chronic infection, or development of cirrhosis, have been associated as risk factors for extrahepatic manifestations. [

7] Optic neuritis is a rare complication in the context of HCV, with only isolated case reports and small series describing its occurrence.[

4,

9] The majority of HCV-associated neurological complications report involvement of peripheral nervous system, most frequently as distal sensory or sensory-motor polyneuropathy, but central nervous system involvement has been rare, especially including optic neuritis, reported in severe or advanced cases.[

6,

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]

The pathogenesis of typical optic neuritis is characterized by an autoimmune-mediated demyelination of the optic nerve, associated with multiple sclerosis (MS). It starts with autoreactive T cells that cross the blood-brain barrier and target myelin antigens, causing inflammation, myelin loss, and axonal injury, resulting in clinical manifestation of acute vision loss, pain with eye movement, and often spontaneous recovery, as re-myelination and resolution of inflammation occur. The immunopathology involves a predominance of Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes, with a relative reduction in regulatory T cells, amplifying the inflammatory process.[

3,

17,

18,

19]

Atypical optic neuritis encompasses wide range of pathologies: NMOSD is driven by autoantibodies against aquaporin-4, leading to complement-mediated astrocyte injury and secondary demyelination; MOGAD involves antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, causing direct myelin damage. Atypical ON is often more severe, bilateral, and less responsive to steroids, with a greater imbalance of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells and reduced regulatory T cell activity compared to typical ON.[

1,

2,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]

Optic neuritis associated with HCV is rare and its pathogenesis is distinct. In mixed cryoglobulinemia, disease processes are typically driven by immune complexes depositing in and damaging small blood vessels, leading to vasculitis. Chronic HCV infection triggers B-cell activation, production of cryoglobulins, and formation of circulating immune complexes, which deposit in small vessels supplying the optic nerve, leading to ischemic and inflammatory injury. Other mechanisms include direct viral neuroinvasion. Seifert et al. reported HCV genome detection in brain tissue from an encephalitic patient; Vargas et al. found replicative HCV negative strands in white matter and cortex; and Wilkinson et al. demonstrated viral presence and replication in CNS microglia/macrophages [

13], systemic inflammation, and cytokine-mediated neurotoxicity. [

4,

13,

14,

15] IFNα monotherapy, although active against virus, was associated with heightened autoimmunity. Thus, the IFNα itself is assumed to brew the pathogenic inflammatory environment for neuropathy

via immune mediated myelin degradation and vessel occlusion causing nerve ischemia, in the absence of cryoglobulinemia. IFNα forms the core of HCV therapy.[

12]

Diagnosing optic neuritis in HCV-infected patients is challenging due to rare association and the broad differential diagnosis. As clinical and radiological findings lack specificity to HCV-related disease, thorough laboratory evaluation for cryoglobulins, complement levels, rheumatoid factor and other markers of systemic vasculitis is indicated. [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8] Exclusion of alternative causes, such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica, other underlying infectious and neoplastic process is essential.[

1,

2,

3] Optical coherence tomography can demonstrate retinal axonal loss, and MRI may show optic nerve enhancement, but these findings are not pathognomonic for HCV-associated disease.[

3,

4] The presence of systemic features such as purpura, arthralgia, and renal involvement may support a diagnosis of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis.[

5]

Management of HCV-associated optic neuritis is not standardized. High-dose corticosteroids are commonly used as first-line therapy for acute optic neuritis, with reported improvement in visual outcomes in some cases.[

1,

2,

3,

6,

9] In the setting of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab may be considered for severe or refractory disease.[

6,

7,

8] The advent of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy has transformed HCV management, with high rates of sustained virological response and evidence supporting resolution or improvement of extrahepatic manifestations, including vasculitic neuropathies.[

6,

13] Studies have shown that DAA therapy is associated with complete or partial remission of mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis in more than 80% of patients, although persistent symptoms may occur due to irreversible damage.[

6] Long-term follow-up is recommended to monitor for recurrence or progression of neurological and systemic manifestations.[

6,

8,

10,

14,

15,

16] Treatment should be individualized according to the severity of the mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and the extent of organ involvement.[

6]

This case report describes an atypical presentation of bilateral optic neuritis in a patient with active, untreated HCV infection, raising important diagnostic considerations at the intersection of infectious and demyelinating pathology.

2. Case Report

A 50-year-old right-handed Caucasian male with PMH of hypertension, untreated Hepatitis C without systemic symptoms and polycythemia vera presented with a three-week history of progressive vision loss—worse in the right eye and involving the lower field of vision in the left eye. He also had intermittent right-sided retro-orbital pressure-like headaches, nausea, imbalance while walking, and two brief episodes of tinnitus. He also had unintentional 20-pound weight loss. He had 10–12 sexual partners over the last 10 years.

Neuro-ophthalmologic examination revealed bilateral grade 4 optic disc edema on the right and Grade 2 on the left—accompanied by macular edema and signs of intermedi-ate/posterior uveitis. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Visual acu-ity was 20/50 in the left eye and “counting fingers” in the right. Neurological exam was significant for brisk reflexes (3+), normal Achilles reflexes, and decreased light touch and pinprick sensation in a glove-and-stocking distribution. Vibration and proprioception were preserved, and the Romberg was negative.

Baseline labs like CBC, Magnesium and CMP were largely unremarkable, except for mildly elevated liver enzymes. Infectious panel done showed positive HCV antibody, with viral load of 9.3 million IU/mL and genotype 3A, EBV and CMV IgG positive, IgM negative (indicating past exposure, not active infection). HBsAg, HSV 1/2, Toxoplasma, Bartonella, RPR were all negative. TB workup, including Quantiferon, TB PCR, and chest X-ray, was negative. Other labs like cryoglobulins were negative. Autoimmune panel showed ANA (1:640, nucleolar pattern). ESR and CRP were normal. Other autoimmune labs, including anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, and rheumatoid factor, were negative. ACE was <10, and lysozyme level was normal.

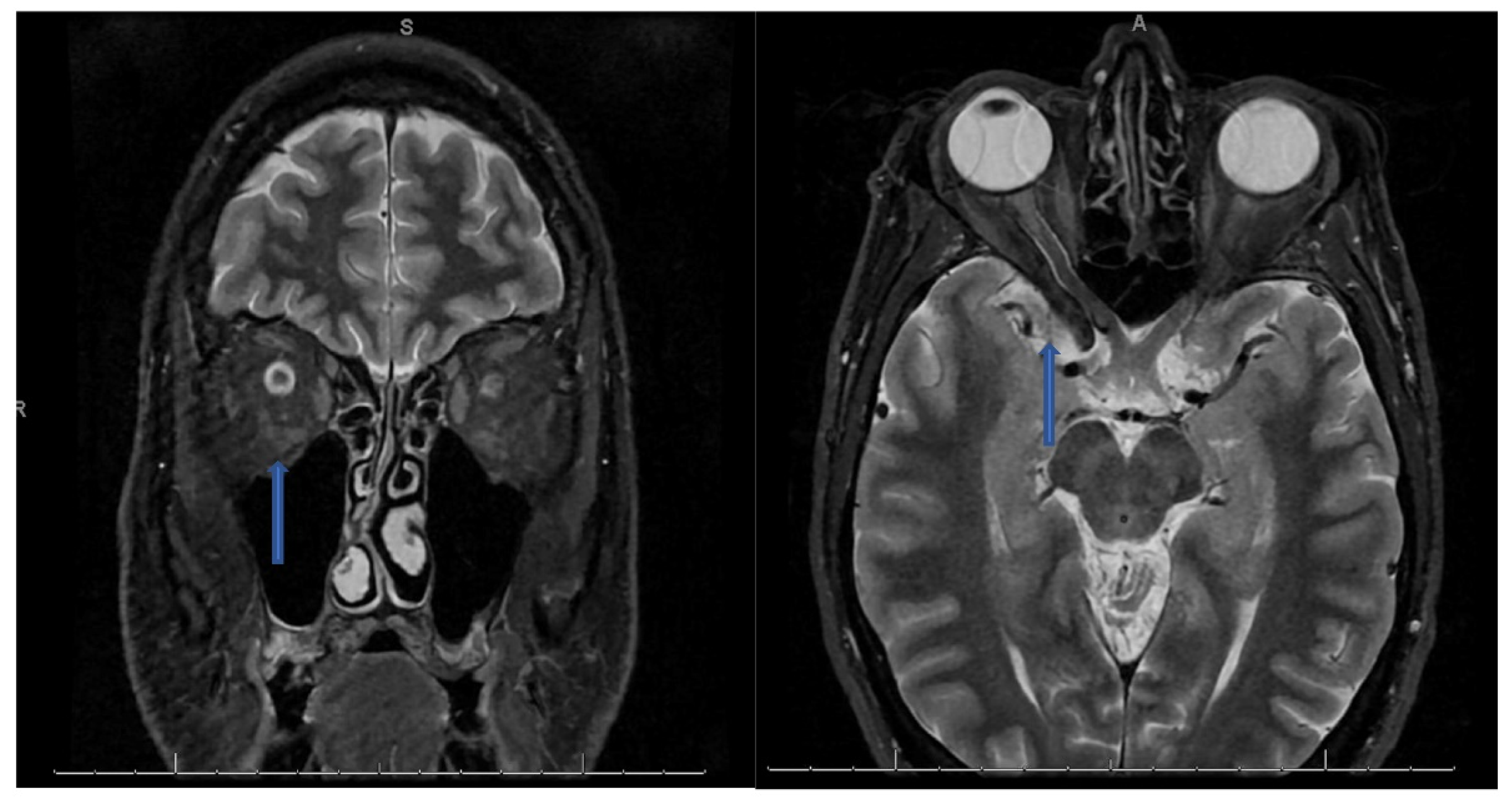

CSF analysis showed lymphocytic pleocytosis with hypo-glycorrhachia and elevated protein suggesting an inflammatory or infectious process (see table below). CSF cultures and meningitis/encephalitis panel were also negative. NMO/MOG/AQP4 antibodies negative. Myelin Basic Protein was found to be elevated at 24.5 ng/ml (Ref interval 0.00–5.50 ng/mL). Oligoclonal bands were also found to be positive with 9 bands detected and IgG Index elevated at 1.81 (Ref Interval: 0.28-0.66). MRI of the orbits with contrast revealed bilateral optic neuritis/perineuritis, with features suggestive of an inflammatory and/or infectious process (

Figure 1). MRI brain with contrast was unremarkable for intracranial lesions.

Once IgA levels were confirmed to be normal, the patient was started on a 5-day course of IVIG for presumed immune-mediated optic neuritis. After consulting with infectious diseases and ophthalmology, corticosteroids were held due to the risk of a catastrophic event that might result due to an active infection. Unfortunately, there was minimal improvement in vision, and his headache persisted. He was discharged with a diagnosis of bilateral optic neuritis, likely due to either a clinically isolated syndrome or possibly Hepatitis C-associated neuroinflammation. HCV treatment could not be started because his incarceration date preceded approval timelines. He was discharged with close follow-up arranged with infectious disease (for HCV treatment), neurology, and ophthalmology.

Figure 1.

Coronal T2 STIR sequence (left) showing hyperintense signal prominently within the right optic nerve than the left with an axial T2 sequence (right) showing hyperintense signal along a segment of the right optic nerve.

Figure 1.

Coronal T2 STIR sequence (left) showing hyperintense signal prominently within the right optic nerve than the left with an axial T2 sequence (right) showing hyperintense signal along a segment of the right optic nerve.

3. Discussion

This case presents an unusual constellation of findings that challenge conventional diagnostic pathways for optic neuritis and demyelinating disease. The patient’s bilateral optic neuritis, uveitis, and inflammatory CSF profile with elevated myelin basic protein and oligoclonal bands suggest a central nervous system demyelinating process, raising concern for the diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). However, the presentation deviates from the classic monophasic optic neuritis seen in CIS or early multiple sclerosis (MS), which typically involves unilateral vision loss, a positive relative afferent pupillary defect, and is more common in younger adults [

23]. The absence of MRI lesions fulfilling the McDonald criteria for MS and the presence of bilateral macular edema and posterior uveitis further complicate this picture. While optic neuritis and uveitis are both known features of MS, their simultaneous bilateral occurrence is rare and typically raises suspicion for infectious or systemic inflammatory etiologies [

24] as in this patient.

One of the unique aspects of this case is the coexistence of untreated chronic Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, with a high viral load and genotype 3A, in the absence of cryoglobulinemia or interferon therapy. While ocular manifestations of HCV have been re- ported, optic neuritis remains a rare and poorly characterized phenomenon in this population [

25,

26]. Moreover, most HCV-associated demyelination reported in the literature has occurred secondary to interferon-alpha therapy, which was not the case in this patient [

27]. There is limited but emerging evidence that HCV may induce im-mune-mediated neuroinflammatory changes through molecular mimicry or by directly triggering autoimmune responses within the central nervous system, supported by rare reports of HCV RNA detected in demyelinated lesions [

28]. Our patient’s positive ANA with a nucleolar pattern, lymphocytic pleocytosis with hypoglycorrhachia, and elevated IgG index may further point to an HCV-associated neuroinflammatory process rather than classic MS.

This case contributes to the expanding spectrum of MS mimics and highlights the diagnostic challenges in atypical optic neuritis presentations, especially in the setting of systemic viral infections. The absence of brain MRI lesions, the presence of multiple CSF markers of CNS inflammation, and the deliberate avoidance of corticosteroids in favor of IVIG due to infection risk underscore the importance of careful diagnostic stewardship.