Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Classical Cytotoxicity Assays: Foundations of In Vitro Toxicology

- Box 1. Best practices for classical cytotoxicity assays

- Assay design and execution

- Verify signal linearity with cell density (5×10³–2×10⁴ cells/well in 96-well plates);

- Optimize dye incubation times (e.g., 2–4 h MTT; 3 h NRU) and report conditions;

- Control for LDH background in serum; use serum-free or heat-inactivated controls.

- Controls and interference checks

- Screen test compounds for intrinsic fluorescence or colour; include “no-cell” blanks;

- Assess dye adsorption by nanomaterials and confirm with independent endpoints;

- Use appropriate positive and negative controls (e.g., Triton X-100, staurosporine) to verify responsiveness.

- Data processing and normalization

- Subtract background from blank wells;

- Normalise viability to untreated controls (100 %) and maximal lysis (0 %);

- Report raw data, at least three biological replicates with technical triplicates, and variability metrics.

- Reporting transparency

- Specify seeding density, passage number, medium composition, incubation time, dye concentration, and detection settings;

- Describe curve fitting and statistical methods clearly;

- Note any deviations from OECD or ISO guidelines.

- Box 2. Common pitfalls in classical cytotoxicity assays

- MTT: non-specific reduction by compounds or medium; insoluble formazan crystals; metabolic stimulation mistaken for viability [37];

- NRU: dependence on pH or lysosomal health; false cytotoxicity when lysosomes are targeted [40];

- Resazurin: over-reduction in highly active cells; fluorescence quenching by test compounds [42];

- Protein/biomass assays: variability in fixation or staining; insensitivity to metabolic suppression without cell loss [44];

3. Transition from Viability Endpoints to Mechanistic Approaches

3.1. From Viabifitnesslity to High-Throughput Screening

3.2. Multiparametric and High-Content Imaging Approaches

3.3. Refining Genotoxicity Assays to Reduce False Outcomes

3.4. Bridging to Three-Dimensional Cultures and Organoids

- Box 3. Practical guidance for modern in vitro cytotoxicity studies.

4. Stem Cell-Based Models in Cytotoxicity Testing

4.1. Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs)

4.2. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs)

4.3. Applications in Developmental and Organ-Specific Toxicity

4.4. Ethical and Technical Considerations

- Box 4. Ethical frameworks for stem cell toxicity models

- Declaration of Helsinki (2013) – Universal ethical principles for research involving human-derived material; mandates informed consent and independent ethical review [123];

- EU Directive 2004/23/EC – Standards for donor consent, traceability, and supervision across EU member states [124];

- NIH Stem Cell Registry (United States) – Specifies approved hESC lines for federally funded research in the US [125];

- ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation (2021) – Global reference for hESC/hiPSC research; emphasises informed consent, data protection, and prohibition of reproductive cloning [126];

- National and Institutional Oversight Committees – Ensure compliance with local ethical regulations [126].

- Practical requirements:

- Documented donor consent (in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or somatic cell source);

- Registration of cell lines in recognised repositories;

- Institutional ethics board approval and adherence to ISSCR guidance.

4.5. Adult Stem Cell Models (HSCs and MSCs)

5. Nanotoxicology and Specialized In Vitro Models

5.1. Cytotoxicity of Nanomaterials: Mechanistic Basis of Oxidative Stress

5.2. Adaptation of Classical Cytotoxicity Assays to Nanomaterials

5.3. Specialized In Vitro Models and Specific Endpoints

- Box 5. Practical and mechanistic insights into nanotoxicology.

- Assay adaptation: Nanoparticles interfere with colourimetric and fluorometric assays by adsorbing dyes or catalysing redox reactions. Reliable assessment therefore requires nanoparticle-only controls and confirmation using orthogonal endpoints such as ATP quantification or impedance-based measurements [70,71,162,165].

6. Advanced 3D Models: Organoids, Organ-on-Chip, and Bioprinting

6.1. Organoids: Tissue-Specific and Immune-Competent Models

6.2. Microfluidics: Organ-on-Chip and Body-on-Chip Systems

6.3. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting: Standardisation and Reproducibility

6.4. Translational ADME–Tox Prediction and In Vivo Extrapolation

- Box 6. Practical Guidance for Model Design and Integration

- Combine static and dynamic systems: Use organoids as foundational tissue modules and integrate them into microfluidic circuits to capture physiological flow, nutrient gradients, and metabolite exchange.

- Standardise culture conditions: Define media composition, extracellular matrix parameters, and bioprinting settings to minimise batch variation and improve reproducibility across laboratories.

- Benchmark with reference compounds: Validate functional readouts (e.g., albumin, urea, γ-GT, transporter activity) using well-characterised hepatotoxins or nephrotoxins before introducing novel agents.

- Implement multi-organ connectivity: Couple intestinal, hepatic, and renal modules to assess systemic ADME and metabolite-driven toxicity, supporting quantitative IVIVE modelling.

- Integrate computational tools: Apply PBPK and QIVIVE frameworks to translate microphysiological outputs into clinically relevant exposure predictions.

- Ensure regulatory alignment: Follow OECD and FDA recommendations on Good Cell and Tissue Culture Practice and NAMs to support data acceptance and cross-sector harmonisation.

7. In Silico Approaches and Computational Toxicology

- Box 7. Practical workflow for computational toxicology (from data to decision).

- Define the question and endpoint. Select a suitable modelling family (QSAR or ML) and the kinetic coupling (PBPK or QIVIVE) appropriate to the context.

- FAIR data curation. Standardise identifiers, harmonise units, remove duplicates and outliers, and record provenance and data partitions [199].

7.1. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships (QSAR), Read-Across, and Cheminformatics

- careful descriptor selection and redundancy control,

- transparent separation of training and validation sets,

- Y-randomisation to exclude chance correlations, and

7.2. Machine Learning and AI for Cytotoxicity Prediction

7.3. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modelling

- Population relevance: evaluation of specific subgroups such as paediatrics, pregnancy, or hepatic/renal impairment.

- Uncertainty management: systematic sensitivity analysis of physiological and chemical parameters to assess influence on predictions.

- Model qualification: benchmarking against reliable clinical reference data [201].

7.4. Quantitative In Vitro–In Vivo Extrapolation (QIVIVE)

- (i)

- correction of in vitro concentrations for plastic and protein binding;

- (ii)

- determination of binding fractions in blood and tissues;

- (iii)

- measurement of metabolic and excretory clearance; and

- (iv)

- definition of the relevant exposure metric - Cmax, AUC, or steady state - with quantified uncertainty.

- Box 8. Key resources for QIVIVE and PBPK modeling

- Reviews and Methods

- Practical roadmaps for QIVIVE and integration into IATA [87]

- High-throughput PBTK for IVIVE at scale [88]

- PBPK for decision-making and uncertainty analysis [201]

- Model-informed development for special populations [89]

- Linking phenotypic profiling with QIVIVE (Cell Painting) [61]

- Case Studies

- PFAS: epigenetic key event integration within PBPK [215]

- AChE inhibition: kinetic cross-species concordance [214]

- How-To Sources

- Box 9. Practical workflow for QIVIVE and PBPK implementation.

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

8. Integrated Approaches and Regulatory Perspectives

8.1. From Concept to Practice: Building Confidence in NAMs

-

Box 10. Context-of-use validation: how NAMs gain regulatory credibilityRegulatory confidence in NAMs is achieved through context-of-use validation, which establishes a method’s reliability for a defined regulatory purpose rather than as a universal replacement for animal testing.

- Examples:

- Skin sensitization – The DA (OECD TG 497) is validated for identifying sensitising chemicals but not for potency ranking or quantitative risk assessment [220].

- Skin irritation – Reconstructed human epidermis models (OECD TG 439) are accepted for classification and labelling but not for chronic or systemic toxicity testing [221].

-

Key principle:Confidence in a NAM depends on demonstrated reliability within its regulatory context - each method is accepted only for what it has been proven to do.

8.2. Case Studies and Regulatory Uptake

- Box 11. Emerging Platforms for Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Testing

- ReproTracker – Tracks differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into germ layers to detect embryotoxic and teratogenic effects through gene-expression markers [231].

- PluriLum Test – Combines stem-cell differentiation with high-content imaging and transcriptomics, generating mechanistic fingerprints of disrupted morphogenesis [232].

8.3 Global Regulatory Perspectives

8.4. Outlook and Emerging Trends

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D / 3D | Two-/Three-Dimensional Cell Culture |

| 3Rs | Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| DA | Defined Approach |

| DDI | Drug–drug interaction |

| D(E)T | Developmental (Embryo) Toxicity |

| DILI | Drug-Induced Liver Injury |

| DNT | Developmental Neurotoxicity |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HCI | High-Content Imaging |

| HCS | High-Content Screening |

| hESC | Human Embryonic Stem Cell |

| hiPSC / iPSC | (Human) Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| hiPSC-CM | hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocyte |

| HSC | Hematopoietic Stem Cell |

| HTS / qHTS | (Quantitative) High-Throughput Screening |

| IATA | Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment |

| ISSCR | International Society for Stem Cell Research |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| MCS | Mesenchymal Stromal Cell |

| MEA | Microelectrode Array |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MPS | Microphysiological System |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NAMs | New Approach Methodologies |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NRU | Neutral Red Uptake |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PBPK | Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (Modeling) |

| PFAS | polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PI | Propidium Iodide |

| PSC | Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| QIVIVE | Quantitative In Vitro–In Vivo Extrapolation |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RTCA | Real-Time Cell Analysis |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TCPL | ToxCast Pipeline for Curve Fitting |

| Tox21 / ToxCast | U.S. Toxicology Data Programs for High-Throughput Screening |

| TT21C | Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century |

| WoE | Weight-of-Evidence |

References

- Taylor, K. Ten Years of REACH - An Animal Protection Perspective. Altern Lab Anim 2018, 46, 347–373. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. “The Future of in Vitro Toxicology.” Toxicology in Vitro 2015, 29, 1217–1221. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Zhang, Q.; Carmichael, P.L.; Boekelheide, K.; Andersen, M.E. Toxicity Testing in the 21 Century: Defining New Risk Assessment Approaches Based on Perturbation of Intracellular Toxicity Pathways. PLoS One 2011, 6. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J Immunol Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Gerlier, D.; Thomasset, N. Use of MTT Colorimetric Assay to Measure Cell Activation. J Immunol Methods 1986, 94, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Decker, T.; Lohmann-Matthes, M.L. A Quick and Simple Method for the Quantitation of Lactate Dehydrogenase Release in Measurements of Cellular Cytotoxicity and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Activity. J Immunol Methods 1988, 115, 61–69. [CrossRef]

- Borenfreund, E.; Puerner, J.A. Toxicity Determined in Vitro by Morphological Alterations and Neutral Red Absorption. Toxicol Lett 1985, 24, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, G.; Timbrell, J.A. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays: Comparison of LDH, Neutral Red, MTT and Protein Assay in Hepatoma Cell Lines Following Exposure to Cadmium Chloride. Toxicol Lett 2006, 160, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Eisenbrand, G.; Pool-Zobel, B.; Baker, V.; Balls, M.; Blaauboer, B.J.; Boobis, A.; Carere, A.; Kevekordes, S.; Lhuguenot, J.C.; Pieters, R.; et al. Methods of in Vitro Toxicology. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2002, 40, 193–236. [CrossRef]

- Sipes, N.S.; Padilla, S.; Knudsen, T.B. Zebrafish: As an Integrative Model for Twenty-First Century Toxicity Testing. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2011, 93, 256–267. [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T. Toxicology for the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2009, 460, 208–212. [CrossRef]

- Dearfield, K.L.; Thybaud, V.; Cimino, M.C.; Custer, L.; Czich, A.; Harvey, J.S.; Hester, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kirkland, D.; Levy, D.D.; et al. Follow-up Actions from Positive Results of in Vitro Genetic Toxicity Testing. Environ Mol Mutagen 2011, 52, 177–204. [CrossRef]

- Toxicology Testing in the 21st Century (Tox21) | US EPA Available online: https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/toxicology-testing-21st-century-tox21 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Toxicity Forecasting (ToxCast) | US EPA Available online: https://www.epa.gov/comptox-tools/toxicity-forecasting-toxcast (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Shukla, S.J.; Huang, R.; Austin, C.P.; Xia, M. The Future of Toxicity Testing: A Focus on in Vitro Methods Using a Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Platform. Drug Discov Today 2010, 15, 997–1007. [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.W.; Peters, M.F.; Dragan, Y.P. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Their Use in Drug Discovery for Toxicity Testing. Toxicol Lett 2013, 219, 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Sureshkumar, P.; Sotiriadou, I.; Hescheler, J.; Sachinidis, A. Human Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Based Toxicity Testing Models: Future Applications in New Drug Discovery. Curr Med Chem 2016, 23, 3495–3509. [CrossRef]

- Schrand, A.M.; Dai, L.; Schlager, J.J.; Hussain, S.M. Toxicity Testing of Nanomaterials. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012, 745, 58–75. [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Rajwade, J.M.; Paknikar, K.M. Nanotoxicology and in Vitro Studies: The Need of the Hour. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2012, 258, 151–165. [CrossRef]

- Hillegass, J.M.; Shukla, A.; Lathrop, S.A.; MacPherson, M.B.; Fukagawa, N.K.; Mossman, B.T. Assessing Nanotoxicity in Cells in Vitro. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2010, 2, 219–231. [CrossRef]

- Pampaloni, F.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Three-Dimensional Cell Cultures in Toxicology. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 2010, 26, 117–138. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zuo, X.; Yuan, J.; Xie, Z.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J. Research Progress in the Development of 3D Skin Models and Their Application to in Vitro Skin Irritation Testing. J Appl Toxicol 2024, 44, 1302–1316. [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, J.; Bertero, A.; Coccini, T.; Baderna, D.; Buzanska, L.; Caloni, F. Organoids Are Promising Tools for Species-Specific in Vitro Toxicological Studies. J Appl Toxicol 2019, 39, 1610–1622. [CrossRef]

- Fair, K.L.; Colquhoun, J.; Hannan, N.R.F. Intestinal Organoids for Modelling Intestinal Development and Disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2018, 373. [CrossRef]

- Van Midwoud, P.M.; Verpoorte, E.; Groothuis, G.M.M. Microfluidic Devices for in Vitro Studies on Liver Drug Metabolism and Toxicity. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011, 3, 509–521. [CrossRef]

- Mahler, G.J.; Esch, M.B.; Stokol, T.; Hickman, J.J.; Shuler, M.L. Body-on-a-Chip Systems for Animal-Free Toxicity Testing. Altern Lab Anim 2016, 44, 469–478. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, S. Organs-on-a-Chip: Current Applications and Consideration Points for in Vitro ADME-Tox Studies. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2018, 33, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Groothuis, F.A.; Heringa, M.B.; Nicol, B.; Hermens, J.L.M.; Blaauboer, B.J.; Kramer, N.I. Dose Metric Considerations in in Vitro Assays to Improve Quantitative in Vitro-in Vivo Dose Extrapolations. Toxicology 2015, 332, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Meek, M.E.B.; Lipscomb, J.C. Gaining Acceptance for the Use of in Vitro Toxicity Assays and QIVIVE in Regulatory Risk Assessment. Toxicology 2015, 332, 112–123. [CrossRef]

- Patlewicz, G.; Fitzpatrick, J.M. Current and Future Perspectives on the Development, Evaluation, and Application of in Silico Approaches for Predicting Toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol 2016, 29, 438–451. [CrossRef]

- Combes, R.D. In Silico Methods for Toxicity Prediction. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012, 745, 96–116. [CrossRef]

- Serafini, M.M.; Sepehri, S.; Midali, M.; Stinckens, M.; Biesiekierska, M.; Wolniakowska, A.; Gatzios, A.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Reszka, E.; Marinovich, M.; et al. Recent Advances and Current Challenges of New Approach Methodologies in Developmental and Adult Neurotoxicity Testing. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1271–1295. [CrossRef]

- Worth, A.P.; Patlewicz, G. Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 856, 317–342. [CrossRef]

- Creton, S.; Dewhurst, I.C.; Earl, L.K.; Gehen, S.C.; Guest, R.L.; Hotchkiss, J.A.; Indans, I.; Woolhiser, M.R.; Billington, R. Acute Toxicity Testing of Chemicals-Opportunities to Avoid Redundant Testing and Use Alternative Approaches. Crit Rev Toxicol 2010, 40, 50–83. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmus, K.R. The Draize Eye Test. Surv Ophthalmol 2001, 45, 493–515. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Ahearne, M.; Hopkinson, A. An Overview of Current Techniques for Ocular Toxicity Testing. Toxicology 2015, 327, 32–46. [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, A.; Joubert, A.M.; Cromarty, A.D. Limitations of the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-Diphenyl-2H-Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay When Compared to Three Commonly Used Cell Enumeration Assays. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 47. [CrossRef]

- Specian, A.F.L.; Serpeloni, J.M.; Tuttis, K.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Cilião, H.L.; Varanda, E.A.; Sannomiya, M.; Martinez-Lopez, W.; Vilegas, W.; Cólus, I.M.S. LDH, Proliferation Curves and Cell Cycle Analysis Are the Most Suitable Assays to Identify and Characterize New Phytotherapeutic Compounds. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 2729. [CrossRef]

- Niles, A.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Riss, T.L. In Vitro Viability and Cytotoxicity Testing and Same-Well Multi-Parametric Combinations for High Throughput Screening. Curr Chem Genomics 2009, 3, 33. [CrossRef]

- Bacanli, M.; Anlar, H.G.; Başaran, A.A.; Başaran, N. Assessment of Cytotoxicity Profiles of Different Phytochemicals: Comparison of Neutral Red and MTT Assays in Different Cells in Different Time Periods. Turk J Pharm Sci 2017, 14, 95. [CrossRef]

- Bopp, S.K.; Lettieri, T. Comparison of Four Different Colorimetric and Fluorometric Cytotoxicity Assays in a Zebrafish Liver Cell Line. BMC Pharmacol 2008, 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ji, J.; Fan, Y. A Resazurin-Based, Nondestructive Assay for Monitoring Cell Proliferation during a Scaffold-Based 3D Culture Process. Regen Biomater 2020, 7, 271. [CrossRef]

- Żyro, D.; Radko, L.; Śliwińska, A.; Chęcińska, L.; Kusz, J.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Przekora, A.; Wójcik, M.; Posyniak, A.; Ochocki, J. Multifunctional Silver(I) Complexes with Metronidazole Drug Reveal Antimicrobial Properties and Antitumor Activity against Human Hepatoma and Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 900. [CrossRef]

- Limame, R.; Wouters, A.; Pauwels, B.; Fransen, E.; Peeters, M.; Lardon, F.; de Wever, O.; Pauwels, P. Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Cell Viability, Migration and Invasion Assessments by Novel Real-Time Technology and Classic Endpoint Assays. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46536. [CrossRef]

- Figueiró, L.R.; Comerlato, L.C.; Da Silva, M.V.; Zuanazzi, J.Â.S.; Von Poser, G.L.; Ziulkoski, A.L. Toxicity of Glandularia Selloi (Spreng.) Tronc. Leave Extract by MTT and Neutral Red Assays: Influence of the Test Medium Procedure. Interdiscip Toxicol 2017, 9, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kourkopoulos, A.; Sijm, D.T.H.M.; Geerken, J.; Vrolijk, M.F. Compatibility and Interference of Food Simulants and Organic Solvents with the in Vitro Toxicological Assessment of Food Contact Materials. J Food Sci 2025, 90, e17659. [CrossRef]

- Oostingh, G.J.; Casals, E.; Italiani, P.; Colognato, R.; Stritzinger, R.; Ponti, J.; Pfaller, T.; Kohl, Y.; Ooms, D.; Favilli, F.; et al. Problems and Challenges in the Development and Validation of Human Cell-Based Assays to Determine Nanoparticle-Induced Immunomodulatory Effects. Part Fibre Toxicol 2011, 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.C.B.; Nunes, H.L.; Ribeiro, D.L.; do Nascimento, J.R.; da Rocha, C.Q.; de Syllos Cólus, I.M.; Serpeloni, J.M. Aglycone Flavonoid Brachydin A Shows Selective Cytotoxicity and Antitumoral Activity in Human Metastatic Prostate (DU145) Cancer Cells. Cytotechnology 2021, 73, 761. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Patil, K.; Ettayebi, K.; Estes, M.K.; Atmar, R.L.; Ramani, S. Divergent Responses of Human Intestinal Organoid Monolayers Using Commercial in Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0304526. [CrossRef]

- Tabernilla, A.; Rodrigues, B.D.S.; Pieters, A.; Caufriez, A.; Leroy, K.; Campenhout, R. Van; Cooreman, A.; Gomes, A.R.; Arnesdotter, E.; Gijbels, E.; et al. In Vitro Liver Toxicity Testing of Chemicals: A Pragmatic Approach. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5038. [CrossRef]

- Filer, D.L.; Kothiya, P.; Woodrow Setzer, R.; Judson, R.S.; Martin, M.T. Tcpl: The ToxCast Pipeline for High-Throughput Screening Data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 618–620. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hallinger, D.R.; Murr, A.S.; Buckalew, A.R.; Lougee, R.R.; Richard, A.M.; Laws, S.C.; Stoker, T.E. High-Throughput Screening and Chemotype-Enrichment Analysis of ToxCast Phase II Chemicals Evaluated for Human Sodium-Iodide Symporter (NIS) Inhibition. Environ Int 2019, 126, 377–386. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hsieh, J.H.; Huang, R.; Sakamuru, S.; Hsin, L.Y.; Xia, M.; Shockley, K.R.; Auerbach, S.; Kanaya, N.; Lu, H.; et al. Cell-Based High-Throughput Screening for Aromatase Inhibitors in the Tox21 10K Library. Toxicol Sci 2015, 147, 446–457. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xia, M.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Q. Identification of Nonmonotonic Concentration-Responses in Tox21 High-Throughput Screening Estrogen Receptor Assays. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2022, 452. [CrossRef]

- Stoker, T.E.; Wang, J.; Murr, A.S.; Bailey, J.R.; Buckalew, A.R. High-Throughput Screening of ToxCast PFAS Chemical Library for Potential Inhibitors of the Human Sodium Iodide Symporter. Chem Res Toxicol 2023, 36, 380–389. [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ostrowska, K.; Maciejewski, H.; Appelhans, D.; Misiewicz, M.; Ziemba, B.; Bednarek, M.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. PPI-G4 Glycodendrimers Upregulate TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. Macromol Biosci 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. A Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Data Analysis Pipeline for Activity Profiling. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2474, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.J. High-Content Analysis in Toxicology: Screening Substances for Human Toxicity Potential, Elucidating Subcellular Mechanisms and in Vivo Use as Translational Safety Biomarkers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2014, 115, 4–17. [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.L.; Adams, M.; Higgins, J.; Bond, J.; Morrison, E.E.; Bell, S.M.; Warriner, S.; Nelson, A.; Tomlinson, D.C. High-Content, High-Throughput Screening for the Identification of Cytotoxic Compounds Based on Cell Morphology and Cell Proliferation Markers. PLoS One 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.A.; Singh, S.; Han, H.; Davis, C.T.; Borgeson, B.; Hartland, C.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Gustafsdottir, S.M.; Gibson, C.C.; Carpenter, A.E. Cell Painting, a High-Content Image-Based Assay for Morphological Profiling Using Multiplexed Fluorescent Dyes. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1757. [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, J.; Willis, C.; Harris, F.R.; Foster, M.J.; Chambers, B.; Culbreth, M.; Brockway, R.E.; Davidson-Fritz, S.; Dawson, D.; Shah, I.; et al. Application of Cell Painting for Chemical Hazard Evaluation in Support of Screening-Level Chemical Assessments. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2023, 468. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, Y.; Joshi, K.; Hickey, C.; Wahler, J.; Wall, B.; Etter, S.; Smith, B.; Griem, P.; Tate, M.; Jones, F.; et al. The BlueScreen HC Assay to Predict the Genotoxic Potential of Fragrance Materials. Mutagenesis 2022, 37, 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Moffat, J.G.; Rudolph, J.; Bailey, D. Phenotypic Screening in Cancer Drug Discovery - Past, Present and Future. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 588–602. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, L.; Corallo, L.; Caterini, J.; Su, J.; Gisonni-Lex, L.; Gajewska, B. Application of XCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis to the Microplate Assay for Pertussis Toxin Induced Clustering in CHO Cells. PLoS One 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Serra, J.; Ggutierrez, A.; Muñoz-Ccapó, S.; Nnavarro-Palou, M.; Rros, T.; Aamat, J.C.; Lopez, B.; Marcus, T.F.; Fueyo, L.; Suquia, A.G.; et al. XCELLigence System for Real-Time Label-Free Monitoring of Growth and Viability of Cell Lines from Hematological Malignancies. Onco Targets Ther 2014, 7, 985–994. [CrossRef]

- Ramis, G.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Quereda, J.J.; Mendonça, L.; Majado, M.J.; Gomez-Coelho, K.; Mrowiec, A.; Herrero-Medrano, J.M.; Abellaneda, J.M.; Pallares, F.J.; et al. Optimization of Cytotoxicity Assay by Real-Time, Impedance-Based Cell Analysis. Biomed Microdevices 2013, 15, 985–995. [CrossRef]

- Bonnevier, J.; Hammerbeck, C.; Goetz, C. Flow Cytometry: Definition, History, and Uses in Biological Research. 2018, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.B.; Khare, P.; Pandey, A.K. Flow Cytometry: Applications in Cellular and Molecular Toxicology. Flow Cytometry: Applications in Cellular and Molecular Toxicology 2025, 1–304. [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ziółkowska, E.; Ziemba, B.; Appelhans, D.; Maciejewski, H.; Voit, B.; Kaczmarek, A.; Robak, T.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Cebula-Obrzut, B.; et al. Glycodendrimer PPI as a Potential Drug in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia. The Influence of Glycodendrimer on Apoptosis in In Vitro B-CLL Cells Defined by Microarrays. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2022, 17, 102–114. [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L.; Goth-Goldstein, R.; Lucas, D.; Koshland, C.P. Particle-Induced Artifacts in the MTT and LDH Viability Assays. Chem Res Toxicol 2012, 25, 1885–1892. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Jiménez, J.L.; Rodríguez-Rivas, C.I.; Mitre-Aguilar, I.B.; Torres-Copado, A.; García-López, E.A.; Herrera-Celis, J.; Arvizu-Espinosa, M.G.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; Arriaga, L.G.; García, J.L.; et al. A Comparative and Critical Analysis for In Vitro Cytotoxic Evaluation of Magneto-Crystalline Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles Using MTT, Crystal Violet, LDH, and Apoptosis Assay. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12860. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S.; Carmichael, P. Reduction of Misleading (“ False”) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. I. Choice of Cell Type. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2012, 742, 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, R.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S.; Carmichael, P. Reduction of Misleading (“ False” ) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. II. Importance of Accurate Toxicity Measurement. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2012, 747, 104–117. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, R.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Carmichael, P.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S. Reduction of Misleading (“false”) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. III: Sensitivity of Human Cell Types to Known Genotoxic Agents. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2014, 767, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Ge, J.; Cohen, J.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Engelward, B.P.; Demokritou, P. High-Throughput Screening Platform for Engineered Nanoparticle-Mediated Genotoxicity Using CometChip Technology. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2118–2133. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yanamandra, A.K.; Qu, B. A High-Throughput 3D Kinetic Killing Assay. Eur J Immunol 2023, 53. [CrossRef]

- Olivo Pimentel, V.; Yaromina, A.; Marcus, D.; Dubois, L.J.; Lambin, P. A Novel Co-Culture Assay to Assess Anti-Tumor CD8+ T Cell Cytotoxicity via Luminescence and Multicolor Flow Cytometry. J Immunol Methods 2020, 487. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Sanny, A.; Chan, D.L.K.; van Noort, D.; Lim, W.; Tan, A.H.M.; Park, S. 3D Hanging Spheroid Plate for High-Throughput CAR T Cell Cytotoxicity Assay. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Son, K.; Hwang, Y.; Ko, J.; Lee, Y.; Doh, J.; Jeon, N.L. High-Throughput Microfluidic 3D Cytotoxicity Assay for Cancer Immunotherapy (CACI-IMPACT Platform). Front Immunol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z. Bin; Huang, R.; Braisted, J.; Chu, P.H.; Simeonov, A.; Gerhold, D.L. 3D-Suspension Culture Platform for High Throughput Screening of Neurotoxic Chemicals Using LUHMES Dopaminergic Neurons. SLAS Discovery 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Meyer, S.R.; O’Meara, M.J.; Huang, S.; Capeling, M.M.; Ferrer-Torres, D.; Childs, C.J.; Spence, J.R.; Fontana, R.J.; Sexton, J.Z. A Human Liver Organoid Screening Platform for DILI Risk Prediction. J Hepatol 2023, 78, 998–1006. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Geng, X.; Li, B. A 3D Spheroid Model of Quadruple Cell Co-Culture with Improved Liver Functions for Hepatotoxicity Prediction. Toxicology 2024, 505. [CrossRef]

- Karassina, N.; Hofsteen, P.; Cali, J.J.; Vidugiriene, J. Time- and Dose-Dependent Toxicity Studies in 3D Cultures Using a Luminescent Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay. Methods Mol Biol 2021, 2255, 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Dominijanni, A.J.; Devarasetty, M.; Forsythe, S.D.; Votanopoulos, K.I.; Soker, S. Cell Viability Assays in Three-Dimensional Hydrogels: A Comparative Study of Accuracy. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2021, 27, 401–410. [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, T.; Lilley, K.S.; Cromarty, A.D. Proteomic Responses of HepG2 Cell Monolayers and 3D Spheroids to Selected Hepatotoxins. Toxicol Lett 2019, 300, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Schmeisser, S.; Miccoli, A.; von Bergen, M.; Berggren, E.; Braeuning, A.; Busch, W.; Desaintes, C.; Gourmelon, A.; Grafström, R.; Harrill, J.; et al. New Approach Methodologies in Human Regulatory Toxicology – Not If, but How and When! Environ Int 2023, 178. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Tan, Y.M.; Allen, D.G.; Bell, S.; Brown, P.C.; Browning, L.; Ceger, P.; Gearhart, J.; Hakkinen, P.J.; Kabadi, S. V.; et al. IVIVE: Facilitating the Use of In Vitro Toxicity Data in Risk Assessment and Decision Making. Toxics 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.; Ring, C.L.; Kreutz, A.; Goldsmith, M.R.; Wambaugh, J.F. High-Throughput PBTK Models for in Vitro to in Vivo Extrapolation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2021, 17, 903–921. [CrossRef]

- Arya, V.; Venkatakrishnan, K. Role of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulation in Enabling Model-Informed Development of Drugs and Biotherapeutics. J Clin Pharmacol 2020, 60 Suppl 1, S7–S11. [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.W.; Austin, S.; Gamma, M.; Cheff, D.M.; Lee, T.D.; Wilson, K.M.; Johnson, J.; Travers, J.; Braisted, J.C.; Guha, R.; et al. Cytotoxic Profiling of Annotated and Diverse Chemical Libraries Using Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. SLAS Discovery 2020, 25, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Sambale, F.; Lavrentieva, A.; Stahl, F.; Blume, C.; Stiesch, M.; Kasper, C.; Bahnemann, D.; Scheper, T. Three Dimensional Spheroid Cell Culture for Nanoparticle Safety Testing. J Biotechnol 2015, 205, 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Krug, A.K.; Kolde, R.; Gaspar, J.A.; Rempel, E.; Balmer, N. V.; Meganathan, K.; Vojnits, K.; Baquié, M.; Waldmann, T.; Ensenat-Waser, R.; et al. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Test Systems for Developmental Neurotoxicity: A Transcriptomics Approach. Arch Toxicol 2013, 87, 123–143. [CrossRef]

- Gunaseeli, I.; Doss, M.; Antzelevitch, C.; Hescheler, J.; Sachinidis, A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Model for Accelerated Patient- and Disease-Specific Drug Discovery. Curr Med Chem 2010, 17, 759–766. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Klima, S.; Sureshkumar, P.S.; Meganathan, K.; Jagtap, S.; Rempel, E.; Rahnenführer, J.; Hengstler, J.G.; Waldmann, T.; Hescheler, J.; et al. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Based Developmental Toxicity Assays for Chemical Safety Screening and Systems Biology Data Generation. J Vis Exp 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Shapiro, S.S.; Waknitz, M.A.; Swiergiel, J.J.; Marshall, V.S.; Jones, J.M. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science (1979) 1998, 282, 1145–1147. [CrossRef]

- Magdy, T.; Schuldt, A.J.T.; Wu, J.C.; Bernstein, D.; Burridge, P.W. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (HiPSC)-Derived Cells to Assess Drug Cardiotoxicity: Opportunities and Problems. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 58, 83–103. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, D.S.; Alawathugoda, T.T.; Ansari, S.A. Fine Tuning of Hepatocyte Differentiation from Human Embryonic Stem Cells: Growth Factor vs. Small Molecule-Based Approaches. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Withey, S.; Harrison, S.; Segeritz, C.P.; Zhang, F.; Atkinson-Dell, R.; Rowe, C.; Gerrard, D.T.; Sison-Young, R.; Jenkins, R.; et al. Phenotypic and Functional Analyses Show Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocyte-like Cells Better Mimic Fetal Rather than Adult Hepatocytes. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 581–589. [CrossRef]

- Hoelting, L.; Scheinhardt, B.; Bondarenko, O.; Schildknecht, S.; Kapitza, M.; Tanavde, V.; Tan, B.; Lee, Q.Y.; Mecking, S.; Leist, M.; et al. A 3-Dimensional Human Embryonic Stem Cell (HESC)-Derived Model to Detect Developmental Neurotoxicity of Nanoparticles. Arch Toxicol 2013, 87, 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.; Tan, J.B.L.; Lim, L.W.; Tan, K.O.; Heng, B.C.; Lim, W.L. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Neural Lineages as In Vitro Models for Screening the Neuroprotective Properties of Lignosus Rhinocerus (Cooke) Ryvarden. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kotasová, H.; Capandová, M.; Pelková, V.; Dumková, J.; Koledová, Z.; Remšík, J.; Souček, K.; Garlíková, Z.; Sedláková, V.; Rabata, A.; et al. Expandable Lung Epithelium Differentiated from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2022, 19, 1033–1050. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, B.; Son, M.Y.; Jung, K.B.; Kim, U.; Kim, J.; Kwon, O.; Son, Y.S.; Jung, C.R.; Park, J.H.; Kim, C.Y. Next-Generation Intestinal Toxicity Model of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Enterocyte-Like Cells. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- van der Torren, C.R.; Zaldumbide, A.; Duinkerken, G.; Brand-Schaaf, S.H.; Peakman, M.; Stangé, G.; Martinson, L.; Kroon, E.; Brandon, E.P.; Pipeleers, D.; et al. Immunogenicity of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.L.; Tan, B.Z.; Goh, W.X.T.; Cua, S.; Choo, A. In Vivo Surveillance and Elimination of Teratoma-Forming Human Embryonic Stem Cells with Monoclonal Antibody 2448 Targeting Annexin A2. Biotechnol Bioeng 2019, 116, 2996–3005. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Wang, C.K.; Yang, S.C.; Hsu, S.C.; Lin, H.; Chang, F.P.; Kuo, T.C.; Shen, C.N.; Chiang, P.M.; Hsiao, M.; et al. Elimination of Undifferentiated Human Embryonic Stem Cells by Cardiac Glycosides. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Xiong, Y.; Siddiq, M.M.; Dhanan, P.; Hu, B.; Shewale, B.; Yadaw, A.S.; Jayaraman, G.; Tolentino, R.E.; Chen, Y.; et al. Multiscale Mapping of Transcriptomic Signatures for Cardiotoxic Drugs. Nat Commun 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.M.; Sparks, N.R.L.; Puig-Sanvicens, V.; Rodrigues, B.; Zur Nieden, N.I. An Evaluation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Test for Cardiac Developmental Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Shinozawa, T.; Kimura, M.; Cai, Y.; Saiki, N.; Yoneyama, Y.; Ouchi, R.; Koike, H.; Maezawa, M.; Zhang, R.R.; Dunn, A.; et al. High-Fidelity Drug-Induced Liver Injury Screen Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Organoids. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 831-846.e10. [CrossRef]

- Carberry, C.K.; Ferguson, S.S.; Beltran, A.S.; Fry, R.C.; Rager, J.E. Using Liver Models Generated from Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (IPSCs) for Evaluating Chemical-Induced Modifications and Disease across Liver Developmental Stages. Toxicol In Vitro 2022, 83. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Inaba, T.; Shinke, K.; Hiramatsu, N.; Horie, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Hata, Y.; Sugihara, E.; Takimoto, T.; Nagai, N.; et al. Comprehensive Search for Genes Involved in Thalidomide Teratogenicity Using Early Differentiation Models of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Potential Applications in Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity Testing. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xie, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Sánchez, O.F.; Rochet, J.C.; Freeman, J.L.; Yuan, C. Developmental Neurotoxicity of PFOA Exposure on HiPSC-Derived Cortical Neurons. Environ Int 2024, 190. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, K.; Chuah, J.K.C.; Su, R.; Huang, P.; Eng, K.G.; Xiong, S.; Li, Y.; Chia, C.S.; Loo, L.H.; Zink, D. Prediction of Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity and Injury Mechanisms with Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cells and Machine Learning Methods. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Achberger, K.; Probst, C.; Haderspeck, J.C.; Bolz, S.; Rogal, J.; Chuchuy, J.; Nikolova, M.; Cora, V.; Antkowiak, L.; Haq, W.; et al. Merging Organoid and Organ-on-a-Chip Technology to Generate Complex Multi-Layer Tissue Models in a Human Retina-on-a-Chip Platform. Elife 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.C.; Kurokawa, Y.K.; Hajek, B.S.; Paladin, J.A.; Shirure, V.S.; George, S.C. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem-Cardiac-Endothelial-Tumor-on-a-Chip to Assess Anticancer Efficacy and Cardiotoxicity. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2020, 26, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Lauschke, K.; Rosenmai, A.K.; Meiser, I.; Neubauer, J.C.; Schmidt, K.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Holst, B.; Taxvig, C.; Emnéus, J.K.; Vinggaard, A.M. A Novel Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Assay to Predict Developmental Toxicity. Arch Toxicol 2020, 94, 3831–3846. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.; Antonijevic, T.; Hall, J.C.; Fisher, J. In Vitro and Computational Approaches to Predict Developmental Toxicity: Integrating PBPK Models with Cell-Based Assays. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2025, 502. [CrossRef]

- Galanjuk, S.; Zühr, E.; Dönmez, A.; Bartsch, D.; Kurian, L.; Tigges, J.; Fritsche, E. The Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Test as an Alternative Method for Embryotoxicity Testing. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lei, W.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Shen, Z.; et al. Generation of Human Vascularized and Chambered Cardiac Organoids for Cardiac Disease Modelling and Drug Evaluation. Cell Prolif 2024, 57. [CrossRef]

- Tidball, A.M.; Niu, W.; Ma, Q.; Takla, T.N.; Walker, J.C.; Margolis, J.L.; Mojica-Perez, S.P.; Sudyk, R.; Deng, L.; Moore, S.J.; et al. Deriving Early Single-Rosette Brain Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2023, 18, 2498–2514. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Comolli, D.; Fanelli, R.; Forloni, G.; De Paola, M. Neonicotinoid Pesticides Affect Developing Neurons in Experimental Mouse Models and in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC)-Derived Neural Cultures and Organoids. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Directive - 2004/23 - EN - EU Tissue Directive - EUR-Lex Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32004L0023 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- HESCRegistry - Public Lines | STEM Cell Information Available online: https://stemcells.nih.gov/registry/eligible-to-use-lines (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Lovell-Badge, R.; Anthony, E.; Barker, R.A.; Bubela, T.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Carpenter, M.; Charo, R.A.; Clark, A.; Clayton, E.; Cong, Y.; et al. ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation: The 2021 Update. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 1398–1408. [CrossRef]

- Weltner, J.; Lanner, F. Refined Transcriptional Blueprint of Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1503–1504. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, P. Some Mechanistic Requirements for Major Transitions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 371. [CrossRef]

- Aalto-Setälä, K.; Conklin, B.R.; Lo, B. Obtaining Consent for Future Research with Induced Pluripotent Cells: Opportunities and Challenges. PLoS Biol 2009, 7, e1000042. [CrossRef]

- Lo, B.; Parham, L. Ethical Issues in Stem Cell Research. Endocr Rev 2009, 30, 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Orzechowski, M.; Schochow, M.; Kühl, M.; Steger, F. Content and Method of Information for Participants in Clinical Studies With Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (IPSCs). Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 627816. [CrossRef]

- Kropf, M. Ethical Aspects of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Alzheimer’s Disease: Potentials and Challenges of a Seemingly Harmless Method. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2023, 7, 993–1006. [CrossRef]

- Witt, G.; Keminer, O.; Leu, J.; Tandon, R.; Meiser, I.; Willing, A.; Winschel, I.; Abt, J.C.; Brändl, B.; Sébastien, I.; et al. An Automated and High-Throughput-Screening Compatible Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Test Platform for Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Assessment of Small Molecule Compounds. Cell Biol Toxicol 2021, 37, 229–243. [CrossRef]

- Lauschke, K.; Treschow, A.F.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Davidsen, N.; Holst, B.; Emnéus, J.; Taxvig, C.; Vinggaard, A.M. Creating a Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based NKX2.5 Reporter Gene Assay for Developmental Toxicity Testing. Arch Toxicol 2021, 95, 1659–1670. [CrossRef]

- Han, I.C.; Bohrer, L.R.; Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Wiley, L.A.; Shrestha, A.; Harman, B.E.; Jiao, C.; Sohn, E.H.; Wendland, R.; Allen, B.N.; et al. Biocompatibility of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Progenitor Cell Grafts in Immunocompromised Rats. Cell Transplant 2022, 31. [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Perspective: Cell Biology to Clinical Progress. NPJ Regen Med 2019, 4, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pasternak-Mnich, K.; Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Ziemba, B.; Pieszyński, I.; Bryszewska, M.; Kujawa, J. Effect of Photobiomodulation Therapy on the Morphology, Intracellular Calcium Concentration, Free Radical Generation, Apoptosis and Necrosis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells-an in Vitro Study. Lasers Med Sci 2024, 39. [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.C.; Medina, S.; Burchiel, S.W. CURRENT PROTOCOLS IN TOXICOLOGY: Evaluation of Toxicity in Mouse Bone Marrow Progenitor Cells. Current protocols in toxicology / editorial board, Mahin D. Maines (editor-in-chief) ... [et al.] 2016, 67, 18.9.1. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.K.; Shukla, P.; Omer, A.; Singh, R.K. In-Vitro Hematological Toxicity Prediction by Colony-Forming Cell Assays. Toxicol Environ Health Sci 2013, 5, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Parent-Massin, D.; Hymery, N.; Sibiril, Y. Stem Cells in Myelotoxicity. Toxicology 2010, 267, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Sun, J.; Ma, T.; Hua, F.; Shen, Z. A Brief Review of Cytotoxicity of Nanoparticles on Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 3875. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, I.; Goulielmaki, M.; Kritikos, A.; Zoumpourlis, P.; Koliakos, G.; Zoumpourlis, V. Suitability of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Fetal Umbilical Cord (Wharton’s Jelly) as an Alternative In Vitro Model for Acute Drug Toxicity Screening. Cells 2022, 11, 1102. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Venkatesan, V.; Prakhya, B.M.; Bhonde, R. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Novel Platform for Simultaneous Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Pharmaceuticals. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 391–399. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Cheng, Z.; Liang, S. Advantages and Prospects of Stem Cells in Nanotoxicology. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132861. [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, B.; Babaahmadi, M.; Pakzad, M.; Hajinasrollah, M.; Mostafaei, F.; Jahangiri, S.; Kamali, A.; Baharvand, H.; Baghaban Eslaminejad, M.; Hassani, S.N.; et al. Standard Toxicity Study of Clinical-Grade Allogeneic Human Bone Marrow-Derived Clonal Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Cao, Y. Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Induced by ZnO Nanoparticles in Endothelial Cells: Interaction with Palmitate or Lipopolysaccharide. J Appl Toxicol 2017, 37, 895–901. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Sinha, S.; Jothiramajayam, M.; Jana, A.; Nag, A.; Mukherjee, A. Cyto-Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress Induced by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle in Human Lymphocyte Cells in Vitro and Swiss Albino Male Mice in Vivo. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2016, 97, 286–296. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Haddouti, E.M.; Beckert, H.; Biehl, R.; Pariyar, S.; Rüwald, J.M.; Li, X.; Jaenisch, M.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; et al. Investigation of Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammatory Responses of Tantalum Nanoparticles in THP-1-Derived Macrophages. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, B.; Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Pion, M.; Appelhans, D.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á.; Voit, B.; Bryszewska, M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Toxicity and Proapoptotic Activity of Poly(Propylene Imine) Glycodendrimers in Vitro: Considering Their Contrary Potential as Biocompatible Entity and Drug Molecule in Cancer. Int J Pharm 2014, 461, 391–402. [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.; Brouwer, H.; Aalderink, G.; Bredeck, G.; Kämpfer, A.A.M.; Schins, R.P.F.; Bouwmeester, H. Investigating Nanoplastics Toxicity Using Advanced Stem Cell-Based Intestinal and Lung in Vitro Models. Frontiers in toxicology 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Vilas-Boas, V.; Lebre, F.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Catarino, C.M.; Moreira Teixeira, L.; Loskill, P.; Alfaro-Moreno, E.; Ribeiro, A.R. Microfluidic-Based Skin-on-Chip Systems for Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Trends Biotechnol 2023, 41, 1282–1298. [CrossRef]

- Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; Karczmarczyk, A.; Jönsson-Niedziółka, M.; Winckler, T.; Feller, K.H. Development of Complex-Shaped Liver Multicellular Spheroids as a Human-Based Model for Nanoparticle Toxicity Assessment in Vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2016, 294, 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Matthews, B.D.; Mammoto, A.; Montoya-Zavala, M.; Yuan Hsin, H.; Ingber, D.E. Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip. Science 2010, 328, 1662–1668. [CrossRef]

- Benameur, L.; Auffan, M.; Cassien, M.; Liu, W.; Culcasi, M.; Rahmouni, H.; Stocker, P.; Tassistro, V.; Bottero, J.Y.; Rose, J.; et al. DNA Damage and Oxidative Stress Induced by CeO2 Nanoparticles in Human Dermal Fibroblasts: Evidence of a Clastogenic Effect as a Mechanism of Genotoxicity. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 696–705. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Mukherjee, S.P.; O’Neill, L.; Byrne, H.J. Structural Dependence of in Vitro Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Uptake Mechanisms of Poly(Propylene Imine) Dendritic Nanoparticles. J Appl Toxicol 2016, 36, 464–473. [CrossRef]

- Magdolenova, Z.; Drlickova, M.; Henjum, K.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Tulinska, J.; Bilanicova, D.; Pojana, G.; Kazimirova, A.; Barancokova, M.; Kuricova, M.; et al. Coating-Dependent Induction of Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9 Suppl 1, 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Xiao, L.; Diener, L.; Arslan, O.; Hirsch, C.; Maeder-Althaus, X.; Grieder, K.; Wampfler, B.; Mathur, S.; Wick, P.; et al. In Vitro Mechanistic Study towards a Better Understanding of ZnO Nanoparticle Toxicity. Nanotoxicology 2013, 7, 402–416. [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ziemba, B.; Sikorska, H.; Jander, M.; Appelhans, D.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. Neurotoxicity of Poly(Propylene Imine) Glycodendrimers. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45, 1484–1492. [CrossRef]

- Gorzkiewicz, M.; Sztandera, K.; Jatczak-Pawlik, I.; Zinke, R.; Appelhans, D.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Pulaski, Ł. Terminal Sugar Moiety Determines Immunomodulatory Properties of Poly(Propyleneimine) Glycodendrimers. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1562–1572. [CrossRef]

- Illarionova, N.B.; Morozova, K.N.; Petrovskii, D. V.; Sharapova, M.B.; Romashchenko, A. V.; Troitskii, S.Y.; Kiseleva, E.; Moshkin, Y.M.; Moshkin, M.P. “Trojan-Horse” Stress-Granule Formation Mediated by Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 1432–1444. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liang, Y.; Wei, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. ROS-Mediated NRF2/p-ERK1/2 Signaling-Involved Mitophagy Contributes to Macrophages Activation Induced by CdTe Quantum Dots. Toxicology 2024, 505. [CrossRef]

- Almutary, A.; Sanderson, B.J.S. The MTT and Crystal Violet Assays: Potential Confounders in Nanoparticle Toxicity Testing. Int J Toxicol 2016, 35, 454–462. [CrossRef]

- Eder, K.M.; Marzi, A.; Wågbø, A.M.; Vermeulen, J.P.; de la Fonteyne-Blankestijn, L.J.J.; Rösslein, M.; Ossig, R.; Klinkenberg, G.; Vandebriel, R.J.; Schnekenburger, J. Standardization of an in Vitro Assay Matrix to Assess Cytotoxicity of Organic Nanocarriers: A Pilot Interlaboratory Comparison. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022, 12, 2187–2206. [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, B.; Matuszko, G.; Bryszewska, M.; Klajnert, B. Influence of Dendrimers on Red Blood Cells. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2012, 17, 21–35. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, D.; Marcinkowska, M.; Janaszewska, A.; Appelhans, D.; Voit, B.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Bryszewska, M.; Štofik, M.; Herma, R.; Duchnowicz, P.; et al. Influence of Core and Maltose Surface Modification of PEIs on Their Interaction with Plasma Proteins—Human Serum Albumin and Lysozyme. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, A.A.M.; Busch, M.; Schins, R.P.F. Advanced In Vitro Testing Strategies and Models of the Intestine for Nanosafety Research. Chem Res Toxicol 2020, 33, 1163–1178. [CrossRef]

- Baek, A.; Kwon, I.H.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, W.H.; Lee, S.W.; Yoo, J.; Heo, M.B.; Lee, T.G. Novel Organoid Culture System for Improved Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Nano Lett 2024, 24, 805–813. [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ostrowska, K.; Maciejewski, H.; Ziemba, B.; Appelhans, D.; Voit, B.; Jander, M.; Treliński, J.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. Affecting NF-ΚB Cell Signaling Pathway in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia by Dendrimers-Based Nanoparticles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018, 357, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Nikonorova, V.G.; Chrishtop, V. V.; Mironov, V.A.; Prilepskii, A.Y. Advantages and Potential Benefits of Using Organoids in Nanotoxicology. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, M.; Aina, K.O.; Grandmougin, L.; Jäger, C.; Pérez Escriva, P.; Letellier, E.; Mosig, A.S.; Wilmes, P. An Organ-on-Chip Platform for Simulating Drug Metabolism Along the Gut-Liver Axis. Adv Healthc Mater 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, K.T.; Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Higgins, J.W.; Chambon, A.; Bishard, K.; Arndt, D.; Er, P.X.; Wilson, S.B.; Howden, S.E.; Tan, K.S.; et al. Cellular Extrusion Bioprinting Improves Kidney Organoid Reproducibility and Conformation. Nat Mater 2021, 20, 260–271. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.R.; Zhang, C.J.; Garcia, M.A.; Procario, M.C.; Yoo, S.; Jolly, A.L.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, K.; Kersten, R.D.; et al. A High-Throughput Microphysiological Liver Chip System to Model Drug-Induced Liver Injury Using Human Liver Organoids. Gastro Hep Advances 2024, 3, 1045–1053. [CrossRef]

- Bronsard, J.; Savary, C.; Massart, J.; Viel, R.; Moutaux, L.; Catheline, D.; Rioux, V.; Clement, B.; Corlu, A.; Fromenty, B.; et al. 3D Multi-Cell-Type Liver Organoids: A New Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease for Drug Safety Assessments. Toxicology in Vitro 2024, 94. [CrossRef]

- Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Wilson, S.B.; Tan, K.S.; Groenewegen, E.; Rudraraju, R.; Neil, J.; Lawlor, K.T.; Mah, S.; Scurr, M.; Howden, S.E.; et al. Enhanced Metanephric Specification to Functional Proximal Tubule Enables Toxicity Screening and Infectious Disease Modelling in Kidney Organoids. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dilz, J.; Auge, I.; Groeneveld, K.; Reuter, S.; Mrowka, R. A Proof-of-Concept Assay for Quantitative and Optical Assessment of Drug-Induced Toxicity in Renal Organoids. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yousef Yengej, F.A.; Jansen, J.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C.; Clevers, H. Kidney Organoids and Tubuloids. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, O.; Nikolaev, M.; Xu, Q.; Broguiere, N.; Cubela, I.; Camp, J.G.; Bscheider, M.; Lutolf, M.P. Bioengineered Human Colon Organoids with in Vivo-like Cellular Complexity and Function. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1175-1186.e7. [CrossRef]

- Jelinsky, S.A.; Derksen, M.; Bauman, E.; Verissimo, C.S.; van Dooremalen, W.T.M.; Roos, J.L.; Barón, C.H.; Caballero-Franco, C.; Johnson, B.G.; Rooks, M.G.; et al. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Human Intestinal Organoids and Monolayers for Modeling Epithelial Barrier. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2023, 29, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, E.T.; Arian, C.M.; Aryeh, K.S.; Wang, K.; Thummel, K.E.; Kelly, E.J. Human Intestinal Enteroids: Nonclinical Applications for Predicting Oral Drug Disposition, Toxicity, and Efficacy. Pharmacol Ther 2025, 273. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, J.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Leng, L. A Skin Organoid-Based Infection Platform Identifies an Inhibitor Specific for HFMD. Nat Commun 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rim, Y.A.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.J.; Kim, H.; Ahn, S.J.; Ju, J.H. Guidelines for Manufacturing and Application of Organoids: Skin. Int J Stem Cells 2024, 17, 182–193. [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.T.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Giangarra, V.; Grzeskowiak, C.L.; Ju, J.; Liu, I.H.; Chiou, S.H.; Salahudeen, A.A.; Smith, A.R.; et al. Organoid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 175, 1972-1988.e16. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Lieshout, R.; van Tienderen, G.S.; de Ruiter, V.; van Royen, M.E.; Boor, P.P.C.; Magré, L.; Desai, J.; Köten, K.; Kan, Y.Y.; et al. Modelling Immune Cytotoxicity for Cholangiocarcinoma with Tumour-Derived Organoids and Effector T Cells. Br J Cancer 2022, 127, 649–660. [CrossRef]

- Avnet, S.; Pompo, G. Di; Borciani, G.; Fischetti, T.; Graziani, G.; Baldini, N. Advantages and Limitations of Using Cell Viability Assays for 3D Bioprinted Constructs. Biomed Mater 2024, 19. [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, M.; Giordano, E. Non-Destructive Monitoring of 3D Cell Cultures: New Technologies and Applications. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13338. [CrossRef]

- Sakolish, C.; Moyer, H.L.; Tsai, H.H.D.; Ford, L.C.; Dickey, A.N.; Wright, F.A.; Han, G.; Bajaj, P.; Baltazar, M.T.; Carmichael, P.L.; et al. Analysis of Reproducibility and Robustness of a Renal Proximal Tubule Microphysiological System OrganoPlate 3-Lane 40 for in Vitro Studies of Drug Transport and Toxicity. Toxicol Sci 2023, 196, 52–70. [CrossRef]

- Theobald, J.; Ghanem, A.; Wallisch, P.; Banaeiyan, A.A.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Taškova, K.; Haltmeier, M.; Kurtz, A.; Becker, H.; Reuter, S.; et al. Liver-Kidney-on-Chip To Study Toxicity of Drug Metabolites. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2018, 4, 78–89. [CrossRef]

- Moerkens, R.; Mooiweer, J.; Ramírez-Sánchez, A.D.; Oelen, R.; Franke, L.; Wijmenga, C.; Barrett, R.J.; Jonkers, I.H.; Withoff, S. An IPSC-Derived Small Intestine-on-Chip with Self-Organizing Epithelial, Mesenchymal, and Neural Cells. Cell Rep 2024, 43. [CrossRef]

- Graf, K.; Murrieta-Coxca, J.M.; Vogt, T.; Besser, S.; Geilen, D.; Kaden, T.; Bothe, A.K.; Morales-Prieto, D.M.; Amiri, B.; Schaller, S.; et al. Digital Twin-Enhanced Three-Organ Microphysiological System for Studying Drug Pharmacokinetics in Pregnant Women. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, M.C.; Bernal, P.N.; Oosterhoff, L.A.; van Wolferen, M.E.; Lehmann, V.; Vermaas, M.; Buchholz, M.B.; Peiffer, Q.C.; Malda, J.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; et al. Bioprinting of Human Liver-Derived Epithelial Organoids for Toxicity Studies. Macromol Biosci 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Marsee, A.; van Tienderen, G.S.; Rezaeimoghaddam, M.; Sheikh, H.; Samsom, R.A.; de Koning, E.J.P.; Fuchs, S.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; et al. Accelerated Production of Human Epithelial Organoids in a Miniaturized Spinning Bioreactor. Cell Reports Methods 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Addario, G.; Moroni, L.; Mota, C. Kidney Fibrosis In Vitro and In Vivo Models: Path Toward Physiologically Relevant Humanized Models. Adv Healthc Mater 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Koido, M.; Kawakami, E.; Fukumura, J.; Noguchi, Y.; Ohori, M.; Nio, Y.; Nicoletti, P.; Aithal, G.P.; Daly, A.K.; Watkins, P.B.; et al. Polygenic Architecture Informs Potential Vulnerability to Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1541–1548. [CrossRef]

- Lauschke, V.M. Toxicogenomics of Drug Induced Liver Injury - from Mechanistic Understanding to Early Prediction. Drug Metab Rev 2021, 53, 245–252. [CrossRef]

- Hermann, N.G.; Ficek, R.A.; Markov, D.A.; McCawley, L.J.; Hutson, M.S. Toxicokinetics for Organ-on-Chip Devices. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 2017–2029. [CrossRef]

- Novak, R.; Ingram, M.; Marquez, S.; Das, D.; Delahanty, A.; Herland, A.; Maoz, B.M.; Jeanty, S.S.F.; Somayaji, M.R.; Burt, M.; et al. Robotic Fluidic Coupling and Interrogation of Multiple Vascularized Organ Chips. Nat Biomed Eng 2020, 4, 407–420. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chou, W.C. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Toxicological Sciences. Toxicol Sci 2022, 189, 7–19. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, T.; Zhu, H. Advancing Computational Toxicology by Interpretable Machine Learning. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 17690–17706. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.T.D.; Belfield, S.J.; Briggs, K.A.; Enoch, S.J.; Firman, J.W.; Frericks, M.; Garrard, C.; Maccallum, P.H.; Madden, J.C.; Pastor, M.; et al. Making in Silico Predictive Models for Toxicology FAIR. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2023, 140. [CrossRef]

- Gini, G. QSAR Methods. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2425, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Heimbach, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Dixit, V.; Parrott, N.; Peters, S.A.; Poggesi, I.; Sharma, P.; Snoeys, J.; Shebley, M.; et al. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Renal and Hepatic Impairment Populations: A Pharmaceutical Industry Perspective. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021, 110, 297–310. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.L.; Silvola, R.M.; Haas, D.M.; Quinney, S.K. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling in Pregnancy: Model Reproducibility and External Validation. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022, 88, 1441–1451. [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Russo, D.P.; Ciallella, H.L.; Wang, Y.T.; Wu, M.; Aleksunes, L.M.; Zhu, H. Data-Driven Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Modeling for Human Carcinogenicity by Chronic Oral Exposure. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 6573–6588. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Kemmler, E.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: A Webserver for the Prediction of Toxicity of Chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W513–W520. [CrossRef]

- Sedykh, A.Y.; Shah, R.R.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Auerbach, S.S.; Gombar, V.K. Saagar-A New, Extensible Set of Molecular Substructures for QSAR/QSPR and Read-Across Predictions. Chem Res Toxicol 2021, 34, 634–640. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; Volarath, P.; Racz, R.; Cross, K.P.; Girireddy, M.; Chakravarti, S.; Stavitskaya, L. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Models to Predict Cardiac Adverse Effects. Chem Res Toxicol 2024, 37, 1924–1933. [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Kalvass, J.C.; Degoey, D.; Hosmane, B.; Doktor, S.; Desino, K. Global Analysis of Models for Predicting Human Absorption: QSAR, In Vitro, and Preclinical Models. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 9389–9403. [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.D.; Hao, Y.; Moore, J.H.; Penning, T.M. Automating Predictive Toxicology Using ComptoxAI. Chem Res Toxicol 2022, 35, 1370–1382. [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pan, F.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. In Silico Prediction of Chemical Acute Dermal Toxicity Using Explainable Machine Learning Methods. Chem Res Toxicol 2024, 37, 513–524. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Liu, G. In Silico Prediction of HERG Blockers Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches. J Appl Toxicol 2023, 43, 1462–1475. [CrossRef]

- Berton, M.; Bettonte, S.; Stader, F.; Battegay, M.; Marzolini, C. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling to Identify Physiological and Drug Parameters Driving Pharmacokinetics in Obese Individuals. Clin Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 277–295. [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.C.; Chen, Q.; Yuan, L.; Cheng, Y.H.; He, C.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E.; Lin, Z. An Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Predict Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumors in Mice. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 361, 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, O.; Genc, D.E.; O. Ulgen, K. Advances in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Nanomaterials. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2024, 7, 2251–2279. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, S.; Wesseling, S.; Kramer, N.I.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Bouwmeester, H. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition in Rats and Humans Following Acute Fenitrothion Exposure Predicted by Physiologically Based Kinetic Modeling-Facilitated Quantitative In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 20521–20531. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Human Health Risk Assessment of 6:2 Cl-PFESA through Quantitative in Vitro to in Vivo Extrapolation by Integrating Cell-Based Assays, an Epigenetic Key Event, and Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Environ Int 2023, 173. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.C.; Thompson, C. V. Pharmacokinetic Tools and Applications. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2425, 57–83. [CrossRef]

- Tess, D.; Chang, G.C.; Keefer, C.; Carlo, A.; Jones, R.; Di, L. In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation and Scaling Factors for Clearance of Human and Preclinical Species with Liver Microsomes and Hepatocytes. AAPS J 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Casati, S. Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 123 Suppl 5, 51–55. [CrossRef]

- Sewell, F.; Alexander-White, C.; Brescia, S.; Currie, R.A.; Roberts, R.; Roper, C.; Vickers, C.; Westmoreland, C.; Kimber, I. New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Identifying and Overcoming Hurdles to Accelerated Adoption. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- OECD Guideline No. 497: Defined Approaches on Skin Sensitisation; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing, 2025;

- OECD Test No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2025;

- van der Zalm, A.J.; Barroso, J.; Browne, P.; Casey, W.; Gordon, J.; Henry, T.R.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Lowit, A.B.; Perron, M.; Clippinger, A.J. A Framework for Establishing Scientific Confidence in New Approach Methodologies. Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 2865–2879. [CrossRef]

- Stucki, A.O.; Barton-Maclaren, T.S.; Bhuller, Y.; Henriquez, J.E.; Henry, T.R.; Hirn, C.; Miller-Holt, J.; Nagy, E.G.; Perron, M.M.; Ratzlaff, D.E.; et al. Use of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to Meet Regulatory Requirements for the Assessment of Industrial Chemicals and Pesticides for Effects on Human Health. Frontiers in toxicology 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, G.; Alépée, N.; Tan, B.; Roper, C.S. A Call to Action: Advancing New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in Regulatory Toxicology through a Unified Framework for Validation and Acceptance. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2025, 162. [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G.H.; Bearth, A.; Jones, L.B.; Hoffmann, S.; Vist, G.E.; Ames, H.M.; Husøy, T.; Svendsen, C.; Tsaioun, K.; Ashikaga, T.; et al. Time for CHANGE: System-Level Interventions for Bringing Forward the Date of Effective Use of NAMs in Regulatory Toxicology. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 2299–2308. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test No. 431: In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing, 2025;

- Braakhuis, H.M.; Murphy, F.; Ma-Hock, L.; Dekkers, S.; Keller, J.; Oomen, A.G.; Stone, V. An Integrated Approach to Testing and Assessment to Support Grouping and Read-Across of Nanomaterials After Inhalation Exposure. Appl In Vitro Toxicol 2021, 7, 112–128. [CrossRef]

- OECD Test No. 492: Reconstructed Human Cornea-like Epithelium (RhCE) Test Method for Identifying Chemicals Not Requiring Classification and Labelling for Eye Irritation or Serious Eye Damage; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing, 2025;

- Knetzger, N.; Ertych, N.; Burgdorf, T.; Beranek, J.; Oelgeschläger, M.; Wächter, J.; Horchler, A.; Gier, S.; Windbergs, M.; Fayyaz, S.; et al. Non-Invasive in Vitro NAM for the Detection of Reversible and Irreversible Eye Damage after Chemical Exposure for GHS Classification Purposes (ImAi). Arch Toxicol 2025, 99, 1011–1028. [CrossRef]

- Weissinger, H.; Knetzger, N.; Cleve, C.; Lotz, C. Impedance-Based in Vitro Eye Irritation Testing Enables the Categorization of Diluted Chemicals. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tal, T.; Myhre, O.; Fritsche, E.; Rüegg, J.; Craenen, K.; Aiello-Holden, K.; Agrillo, C.; Babin, P.J.; Escher, B.I.; Dirven, H.; et al. New Approach Methods to Assess Developmental and Adult Neurotoxicity for Regulatory Use: A PARC Work Package 5 Project. Frontiers in toxicology 2024, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, A.; Oyetade, O.B.; Chang, X.; Hsieh, J.H.; Behl, M.; Allen, D.G.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Hogberg, H.T. Integrated Approach for Testing and Assessment for Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) to Prioritize Aromatic Organophosphorus Flame Retardants. Toxics 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- FDA Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies [PDF]; https://www.fda.gov/files/newsroom/published/roadmap_to_reducing_animal_testing_in_preclinical_safety_studies.pdf, 2025;

- European Medicines Agency New Approach Methodologies – EU Horizon Scanning Report.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025;

- Najjar, A.; Kühnl, J.; Lange, D.; Géniès, C.; Jacques, C.; Fabian, E.; Zifle, A.; Hewitt, N.J.; Schepky, A. Next-Generation Risk Assessment Read-across Case Study: Application of a 10-Step Framework to Derive a Safe Concentration of Daidzein in a Body Lotion. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- OECD Guidance Document on the Reporting of Defined Approaches to Be Used Within Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 255; OECD, 2017;

- OECD Guiding Principles and Key Elements for Establishing a Weight of Evidence for Chemical Assessment; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 311; OECD: Paris, 2019;

- Zuang, V.; Baccaro, M.; Barroso, J.; Berggren, E.; Bopp, S.; Bridio, S.; Capeloa, T.; Carpi, D.; Casati, S.; Chinchio, E.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation. In Proceedings of the Publications Office of the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025.

- Zuang, V.; Barroso, J.; Berggren, E.; Bopp, S.; Bridio, S.; Casati, S.; Corvi, R.; Deceuninck, P.; Franco, A.; Gastaldello, A.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation – EURL ECVAM Status Report 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024;

- Zuang, V..; Daskalopoulos, E.P..; Worth, A..; Corvi, R..; Munn, S..; Deceuninck, P..; Barroso, J..; Batista Leite, Sofia.; Berggren, Elisabeth.; Bopp, Stephanie.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation – EURL ECVAM Report 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023;

- OECD Guidance Document on Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) for Phototoxicity Testing; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 397; OECD: Paris, 2024;

- OECD Performance Standards for the Assessment of Proposed Similar or Modified In Vitro Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA) Test Methods; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 396; OECD: Paris, 2024;

- Tsiros, P.; Minadakis, V.; Li, D.; Sarimveis, H. Parameter Grouping and Co-Estimation in Physiologically Based Kinetic Models Using Genetic Algorithms. Toxicol Sci 2024, 200, 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Langan, L.M.; Paparella, M.; Burden, N.; Constantine, L.; Margiotta-Casaluci, L.; Miller, T.H.; Moe, S.J.; Owen, S.F.; Schaffert, A.; Sikanen, T. Big Question to Developing Solutions: A Decade of Progress in the Development of Aquatic New Approach Methodologies from 2012 to 2022. Environ Toxicol Chem 2024, 43, 559–574. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Krause, S.; Brinkmann, M. Validation of Methods for in Vitro- in Vivo Extrapolation Using Hepatic Clearance Measurements in Isolated Perfused Fish Livers. Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 12416–12423. [CrossRef]

| Feature | hESCs | hiPSCs | Adult stem cells (HSCs, MSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Inner cell mass of human blastocysts (IVF surplus embryos) | Reprogrammed adult somatic cells (fibroblasts, blood, urine) using Yamanaka factors | Bone marrow, peripheral blood (HSCs), adipose or umbilical cord tissue (MSCs) |

| Potency | Pluripotent (all germ layers) | Pluripotent (patient-specific, variable) | Multipotent (restricted to specific tissue lineages) |

| Applications | Developmental toxicity; cardiac, hepatic, neuronal, epithelial, ocular models [96,102] | Cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, developmental neurotoxicity, renal and ocular assays, precision toxicology [108,111,113] |

Immunotoxicity, myelotoxicity, biomaterial and nanomaterial cytotoxicity [139,140,142,144] |

| Advantages | Natural pluripotency; reproducible protocols; validated differentiation | Ethically acceptable; scalable; patient-specific |

Easy access; ethically uncontroversial; tissue-relevant |

| Limitations | Ethical controversy; limited access; teratoma risk | Variability; incomplete maturation; donor heterogeneity | Limited potency; donor variability; senescence |

| Ethical/Legal | Strict oversight (NIH Registry, EU Directive 2004/23/EC, ISSCR) | Informed consent; data protection (ISSCR 2021) | Standard medical consent; minimal restrictions |

| Method | Primary Inputs | Typical Outputs | Strengths | Common Pitfalls | Use Cases | Key Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR/ read-across |

Molecular structu-res, curated labels | Class or continuous risk | Fast, interpretable | Limited do-main, data leakage | Early hazard identification | [199,200,203] |

| ML/AI | Structures + omics/phenotypes | Multi-endpoint predictions | Handles non-linear, multi-task data | Interpretability drift | Portfolio triage, prioritisation | [197,198,204] |

| PBPK | Physiology, ADME parametres | Tissue concentra-tion–time (C(t)) | Human- relevance |

Parameter uncertainty | Populations, DDI, exposure assess-ment | [89,201,202] |

| QIVIVE | In vitro ECx + PBPK | Human- equivalent dose | Translational, mechanistic | Mis-specified clearance | Screening-level risk, potency estimation | [87,88] |

| Endpoint | Primary NAM(s)/DA | OECD TG/ Guidance | Regulatory Scope | Status / Notes |

Key Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin sensitisation |

DPRA + KeratinoSens™ + h-CLAT (DA) |

OECD TG 497 (2025) | Classification & labeling | Fully accepted | [220,222] |

| Skin irritation |

Reconstructed epidermis (EpiDerm™, SkinEthic™, epiCS) |

OECD TG 439 (2025) | Classification & labeling | Fully accepted | [218,221] |

| Eye irritation |

Reconstructed corneal epithelium (EpiOcular™, SkinEthic™ HCE) |

OECD TG 492 (2025) | Classification & labeling | Accepted; replaces Draize test | [228,229,230] |

| Phototoxicity | IATA for Phototoxicity | OECD Guidance No. 397 (2024) | Screening / Hazard ID |

Recently introduced | [241] |

| Nanomaterial inhalation |

Grouping / Read-Across Approach |

– | Occupational risk assessment | Emerging application | [227] |

| Developmental toxicity | PluriLum / ReproTracker + PBPK/QIVIVE | – | Developmental & Reproductive | Under validation | [231,232] |

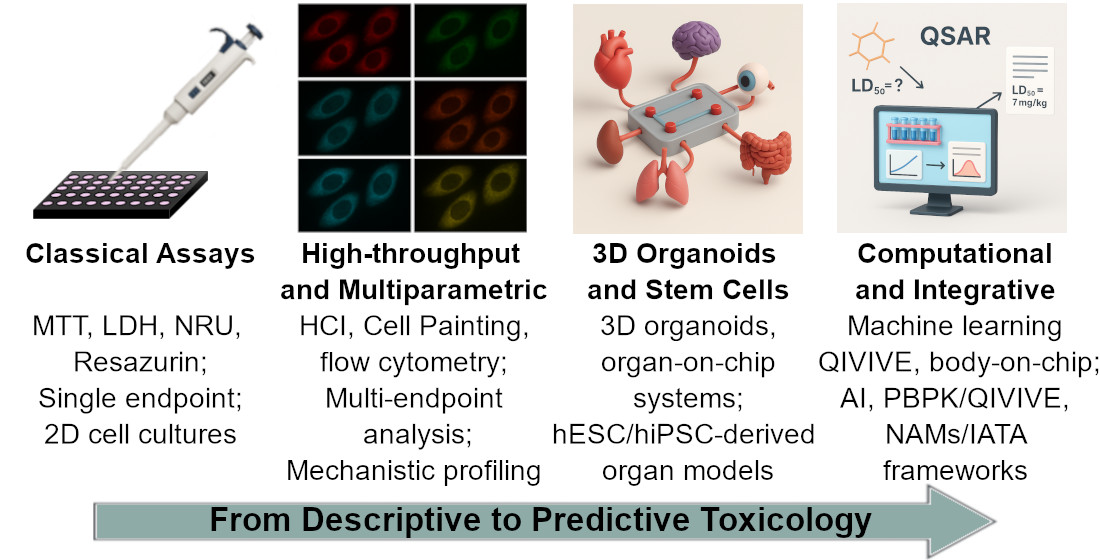

| Stage / Era | Key Advances | Representative Methods / Systems | Main Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (1980s–2000s) |

Colorimetric and metabolic viability assays | MTT, LDH, Neutral Red, Resazurin | Foundation of in vitro toxicology; standardized endpoints; regulatory benchmarks |

| Mechanistic (2000s–2010s) | High-throughput and high-content screening; mechanistic readouts | HCI, Cell Painting, flow cytometry, xCELLigence | Multiparametric mechanistic insight; reduction of false positives/negatives |

| Human-relevant (2010s–2020s) | Stem-cell–based and 3D models | hPSC/hiPSC assays, organoids, organ-on-chip | Human-specific predictive systems; translation to tissue- and organ-level toxicity |

| Computational and Integrative (2020s–present) | AI, PBPK/QIVIVE, NAMs/IATA frameworks | Machine learning, IVIVE, body-on-chip | Mechanistic–quantitative risk assessment; regulatory adoption of non-animal evidence |

| Emerging (Future) |

Personalized, multi-organ, and AI-driven toxicology | Patient-derived hiPSC models, multi-MPS networks, digital twins | Predictive, individualized safety assessment; convergence of toxicology and precision medicine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).