Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methodology

Study Design

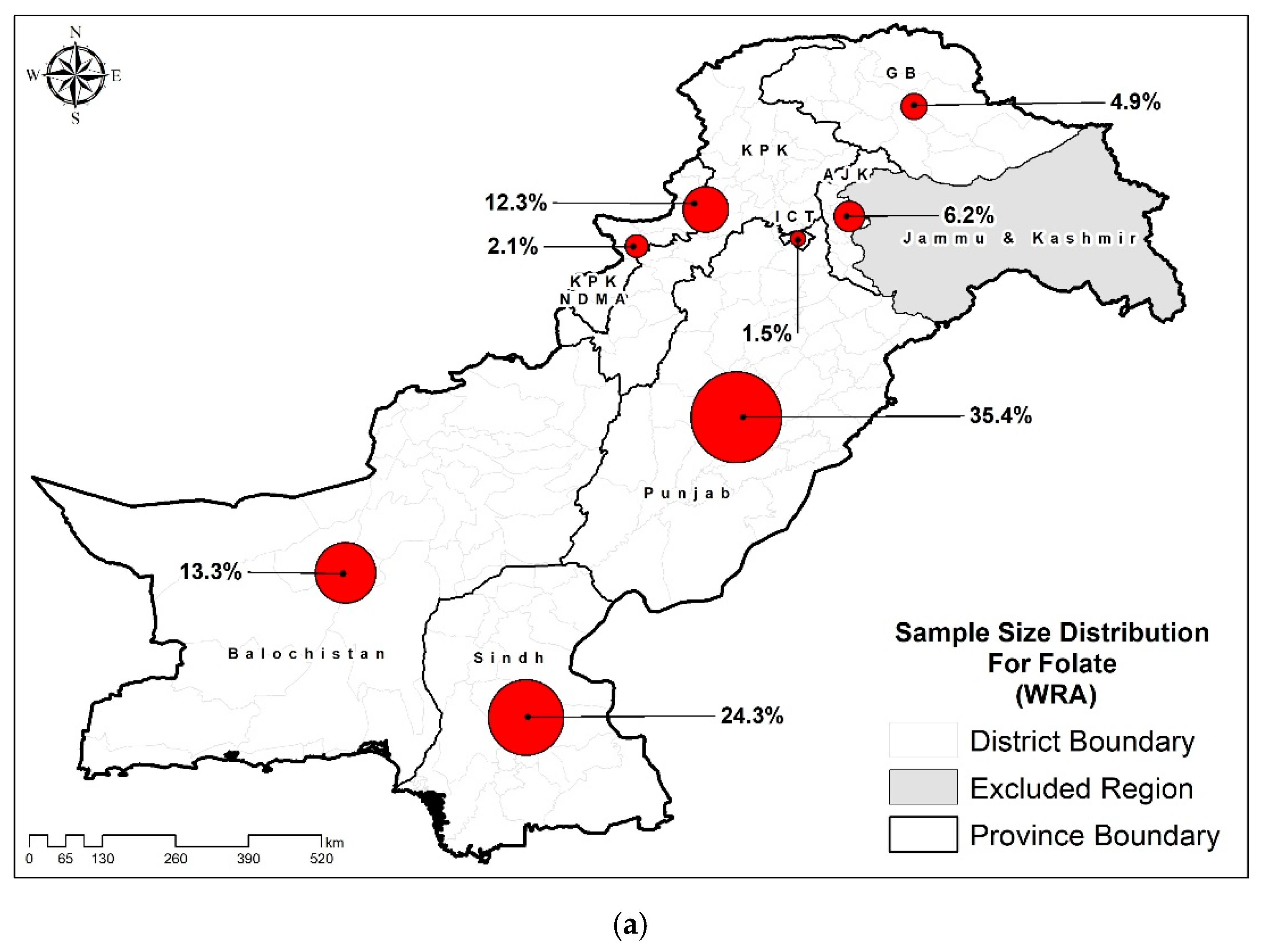

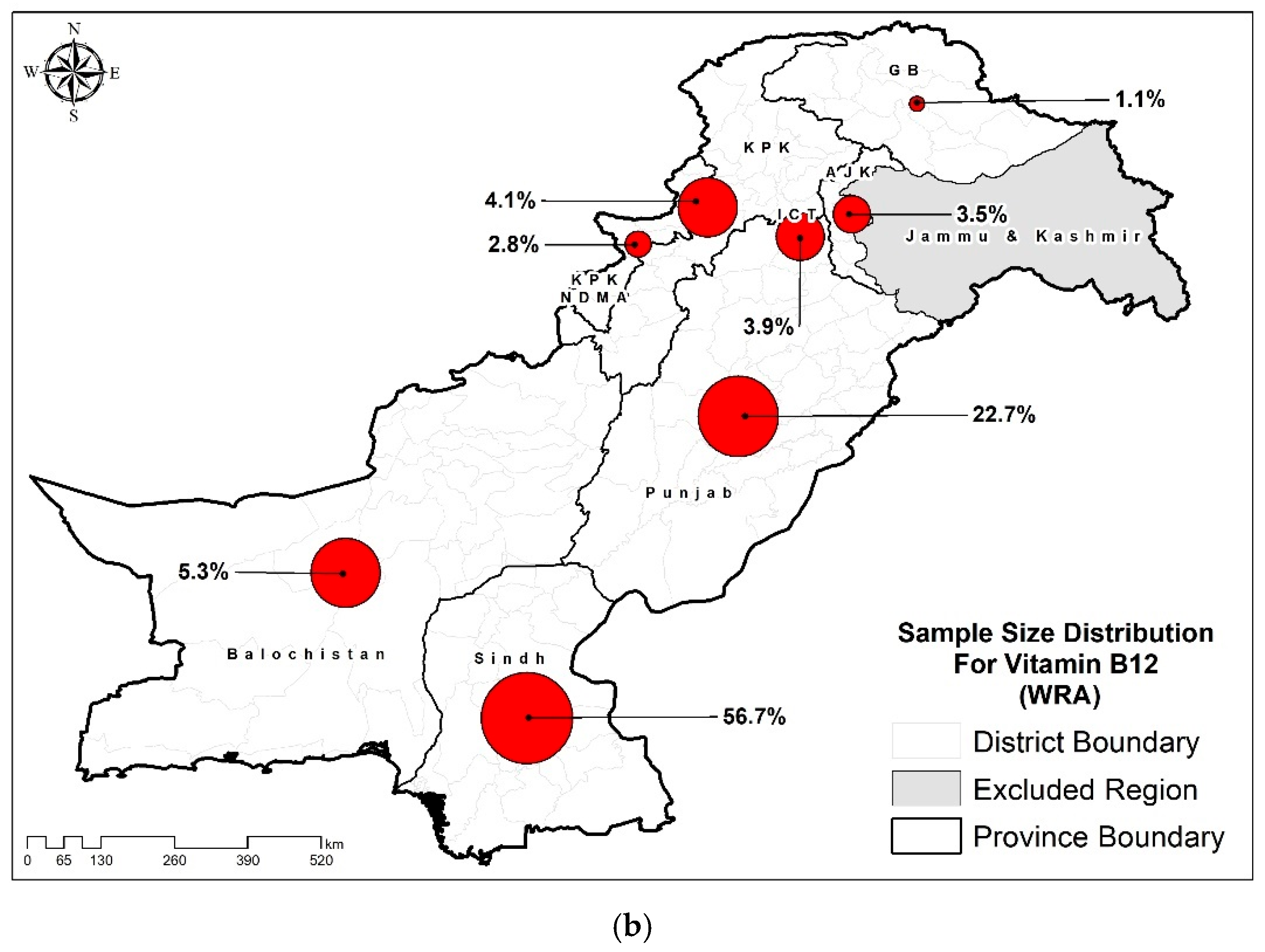

Sample Size Calculation

Sampling Technique

Blood Collection

Biochemical Assessment

Statistical Analysis

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Prevalence of B12 and Folate Deficiency Among Women of Reproductive Age

Key Determinants of Folate and B12 Deficiency in Women of Reproductive Age

| Folate deficiency | B12 deficiency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR (95% CIs) |

P-values | aOR* (95% CIs) |

P-values | OR (95% CIs) |

P-values | aOR* (95% CIs) |

P-values |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Urban | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Rural | 0.967 (0.881,1.062) | 0.485 | 0.967 (0.862,1.085) | 0.569 | 1.293 (1.083,1.544) | 0.005 | 1.407 (1.125,1.760) | 0.003 |

| Province | ||||||||

| Punjab | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Sindh | 1.152 (1.037,1.280) | 0.009 | 1.144 (1.018,1.285) | 0.024 | 0.717 (0.590,0.872) | 0.001 | 0.814 (0.654,1.013) | 0.065 |

| KP | 1.007 (0.881,1.150) | 0.921 | 1.003 (0.875,1.149) | 0.970 | 0.971 (0.651,1.449) | 0.887 | 0.953 (0.632,1.437) | 0.818 |

| Baluchistan | 1.241 (1.069,1.440) | 0.005 | 1.237 (1.052,1.453) | 0.010 | 1.575 (0.988,2.510) | 0.056 | 1.380 (0.857,2.222) | 0.184 |

| ICT | 1.505 (1.099,2.062) | 0.011 | 1.524 (1.109,2.092) | 0.009 | 1.643 (1.130,2.389) | 0.009 | 1.673 (1.122,2.497) | 0.012 |

| KP-NMD | 1.009 (0.738,1.378) | 0.957 | 1.005 (0.732,1.379) | 0.975 | 1.849 (1.176,2.907) | 0.008 | 1.584 (0.977,2.570) | 0.062 |

| AJK | 0.837 (0.686,1.022) | 0.081 | 0.834 (0.682,1.021) | 0.079 | 1.216 (0.743,1.989) | 0.436 | 1.296 (0.770,2.182) | 0.329 |

| GB | 0.897 (0.730,1.103) | 0.304 | 0.885 (0.715,1.095) | 0.261 | 1.990 (0.998,3.966) | 0.051 | 2.472 (1.197,5.106) | 0.015 |

| HH size | ||||||||

| <7 | 0.972 (0.889,1.064) | 0.540 | 1.399 (1.175,1.665) | <0.001 | 1.385 (1.152,1.664) | 0.001 | ||

| 7 or more members | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Wealth Index | ||||||||

| Poorest | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Second | 0.984 (0.861,1.125) | 0.813 | 1.027 (0.892,1.183) | 0.708 | 1.200 (0.935,1.539) | 0.152 | 1.064 (0.817,1.386) | 0.646 |

| Middle | 0.977 (0.852,1.120) | 0.739 | 1.022 (0.875,1.195) | 0.781 | 1.317 (1.023,1.695) | 0.032 | 1.189 (0.894,1.580) | 0.234 |

| Fourth | 0.994 (0.866,1.141) | 0.929 | 1.031 (0.871,1.221) | 0.719 | 0.978 (0.754,1.270) | 0.870 | 0.901 (0.650,1.248) | 0.530 |

| Richest | 0.902 (0.782,1.040) | 0.156 | 0.924 (0.770,1.110) | 0.399 | 1.266 (0.976,1.641) | 0.075 | 1.155 (0.794,1.680) | 0.451 |

| Drinking water source | ||||||||

| Improved sources | 0.879 (0.726,1.065) | 0.189 | 1.107 (0.792,1.546) | 0.553 | ||||

| Unimproved sources | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Sanitation | ||||||||

| Improved sanitation facility | 0.916 (0.816,1.027) | 0.132 | 1.065 (0.874,1.298) | 0.534 | ||||

| Unimproved sanitation facility | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Food Insecurity Status | ||||||||

| Food Secure | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Mild food insecure | 1.091 (0.949,1.254) | 0.223 | 1.072 (0.931,1.234) | 0.333 | 0.809 (0.630,1.040) | 0.098 | 0.760 (0.584,0.991) | 0.043 |

| Moderate food insecure | 1.128 (0.949,1.342) | 0.172 | 1.104 (0.924,1.318) | 0.276 | 0.667 (0.489,0.909) | 0.010 | 0.676 (0.492,0.930) | 0.016 |

| Severe food insecure | 1.040 (0.924,1.171) | 0.512 | 1.007 (0.885,1.146) | 0.913 | 0.758 (0.608,0.943) | 0.013 | 0.795 (0.627,1.007) | 0.057 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 15-19 years | 1.267 (0.984,1.632) | 0.066 | 0.818 (0.473,1.414) | 0.471 | ||||

| 20-34 years | 0.951 (0.865,1.046) | 0.300 | 1.142 (0.951,1.372) | 0.156 | ||||

| 35-49 years | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||

| None | 1.123 (0.967,1.304) | 0.129 | 0.757 (0.576,0.995) |

0.046 | 0.919 (0.662,1.275) | 0.613 | ||

| Primary | 0.998 (0.822,1.212) | 0.983 | 0.645 (0.449,0.925) | 0.017 | 0.684 (0.461,1.014) | 0.058 | ||

| Middle | 1.086 (0.888,1.330) | 0.421 | 0.664 (0.444,0.994) | 0.047 | 0.677 (0.444,1.031) | 0.069 | ||

| Secondary | 1.062 (0.876,1.287) | 0.541 | 0.616 (0.424,0.895) | 0.011 | 0.613 (0.421,0.892) | 0.011 | ||

| Higher | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Employed | 0.966 (0.779,1.199) | 0.757 | 0.985 (0.678,1.430) | 0.936 | ||||

| Unemployed | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Currently Married | 1.021 (0.835,1.250) | 0.836 | 0.956 (0.642,1.425) | 0.826 | ||||

| Ever Married | 1.019 (0.681,1.527) | 0.926 | 0.712 (0.307,1.652) | 0.429 | ||||

| Un-Married | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| BMI of women | ||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.988 (0.854,1.142) | 0.868 | 0.688 (0.521,0.909) | 0.008 | 0.711 (0.534,0.946) | 0.019 | ||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 1.001 (0.897,1.117) | 0.986 | 1.456 (1.184,1.790) | <0.001 | 1.560 (1.262,1.928) | <0.001 | ||

| Obese (>=30) | 0.986 (0.866,1.124) | 0.837 | 1.530 (1.207,1.940) | <0.001 | 1.649 (1.282,2.122) | <0.001 | ||

| Parity | ||||||||

| <3 | 0.997 (0.911,1.091) | 0.946 | 1.263 (1.067,1.496) | 0.007 | 1.247 (1.042,1.492) | 0.016 | ||

| >=3 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Pregnancy status | ||||||||

| Pregnant | 0.967 (0.799,1.171) | 0.732 | 1.976 (1.436,2.720) | <0.001 | 1.903 (1.374,2.635) | <0.001 | ||

| Non-Pregnant | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Minimum dietary diversity | ||||||||

| <5 food groups | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| >=5 food groups | 0.944 (0.844,1.057) | 0.320 | 1.027 (0.823,1.283) | 0.811 | ||||

Discussion

Conclusions

Authors’ Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Review Committee

Ethical Integrity

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habib, M.A.; et al. Factors associated with low birthweight in term pregnancies: a matched case-control study from rural Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J, 2018. 23(11): p. 754-763.

- Prochaska, M.T.; et al. Association Between Anemia and Fatigue in Hospitalized Patients: Does the Measure of Anemia Matter? Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2017. 12(11): p. 898-904.

- Sawant Dessai, A., J. Chakrabarty, and B. Sulochana, The relationship between fatigue, quality of life, and performance status among cancer patients with anemia. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 2025. 31: p. 101899.

- Gan, T.; et al. Causal Association Between Anemia and Cardiovascular Disease: A 2‐Sample Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2023. 12(12): p. e029689.

- Shi, H.; et al. Severity of Anemia During Pregnancy and Adverse Maternal and Fetal Outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 2022. 5(2): p. e2147046-e2147046.

- Defrère, S.; et al. Potential involvement of iron in the pathogenesis of peritoneal endometriosis. Molecular human reproduction, 2008. 14(7): p. 377-385.

- Kapper, C.; et al. Minerals and the Menstrual Cycle: Impacts on Ovulation and Endometrial Health. Nutrients, 2024. 16(7): p. 1008.

- Tonai, S.; et al. Iron deficiency induces female infertile in order to failure of follicular development in mice. Journal of Reproduction and Development, 2020. 66(5): p. 475-483.

- Whitaker, M. Calcium at fertilization and in early development. Physiological reviews, 2006. 86(1): p. 25-88.

- Yılmaz, B.K.; et al. Serum concentrations of heavy metals in women with endometrial polyps. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2020. 40(4): p. 541-545.

- Stevens, G.A.; et al. National, regional, and global estimates of anaemia by severity in women and children for 2000-19: a pooled analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health, 2022. 10(5): p. e627-e639.

- Işık Balcı, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Anemia among Adolescents in Denizli, Turkey. Iran J Pediatr, 2012. 22(1): p. 77-81.

- WHO, The Global Health Observatory. 2019.

- Black, R.E.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet, 2013. 382(9890): p. 427-451.

- Brittenham, G.M.; et al. Biology of Anemia: A Public Health Perspective. The Journal of Nutrition, 2023. 153: p. S7-S28.

- de Benoist, B. Conclusions of a WHO Technical Consultation on Folate and Vitamin B12 Deficiencies. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 2008. 29(2_suppl1): p. S238-S244.

- Finkelstein, J.L. A.J. Layden, and P.J. Stover, Vitamin B-12 and Perinatal Health. Adv Nutr, 2015. 6(5): p. 552-63.

- Abdollahi, Z.; et al. Folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine status in women of childbearing age: baseline data of folic acid wheat flour fortification in Iran. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2008. 53(2): p. 143-150.

- Haidar, J. Prevalence of anaemia, deficiencies of iron and folic acid and their determinants in Ethiopian women. J Health Popul Nutr, 2010. 28(4): p. 359-68.

- Viteri, F.E. and H. Gonzalez, Adverse outcomes of poor micronutrient status in childhood and adolescence. Nutr Rev, 2002. 60(5 Pt 2): p. S77-83.

- Bhattacharya., A.H.P.T. Megaloblastic Anemia. NIH, 2023.

- WHO, Evaluating the public health significance of micronutrient malnutrition.

- Soofi, S.; et al. Prevalence and possible factors associated with anaemia, and vitamin B ((12)) and folate deficiencies in women of reproductive age in Pakistan: analysis of national-level secondary survey data. BMJ Open, 2017. 7(12): p. e018007.

- Mazhar Alam, J.D. Hira Hur, Meg Walker, Albertha Nyaku, Allison Gottwalt, A Qualitative Assessment of Supply and Demand of Maternal Iron-Folic Acid Supplementation and Infant and Young Child Feeding Counseling in Jamshoro and Thatta Districts, Pakistan. USAID, 2018.

- WHO, WHO guidelines on drawing blood: best practices in phlebotomy. 2010.

- CDC, U. Laboratory Quality Assurance Programs. 2024.

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; et al. Estimation of trends in serum and RBC folate in the U.S. population from pre- to postfortification using assay-adjusted data from the NHANES 1988-2010. J Nutr, 2012. 142(5): p. 886-93.

- CDC, C.f.D.C.a.P. FOLATE MICROBIOLOGIC ASSAY. 2018.

- Sanjay, R.; et al. Household Food Insecurity Is Associated with RBC Folate Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anaemia Among Non-Pregnant Nepalese Women Aged 15-49 Years. Journal of Health and Environmental Research, 2023. 9(2): p. 59-66.

- Ndiaye, N.F.; et al. Folate Deficiency and Anemia Among Women of Reproductive Age (15-49 Years) in Senegal: Results of a National Cross-Sectional Survey. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 2018. 39(1): p. 65-74.

- Saxena, V., M. Naithani, and R. Singh, Epidemiological determinants of Folate deficiency among pregnant women of district Dehradun. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 2017. 5(1): p. 21-27.

- DHSPROGRAM, WEALTH INDEX. 2016.

- story, W.n. New Food Fortification Programme to help tackle malnutrition in Pakistan. 2016.

- Ibne Youaaf, A. Food Fortifications and Programs Running in Pakistan. 2022.

- McKillop, D.J.; et al. The effect of different cooking methods on folate retention in various foods that are amongst the major contributors to folate intake in the UK diet. Br J Nutr, 2002. 88(6): p. 681-8.

- Bajaj, S.R. and R.S. Singhal, Fortification of wheat flour and oil with vitamins B12 and D3: Effect of processing and storage. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2021. 96: p. 103703.

- Sedehi, M., N. Behnampour, and M.J. Golalipour, Deficiencies of the microelements, folate and vitamin B12 in women of the child bearing ages in gorgan, northern iran. J Clin Diagn Res, 2013. 7(6): p. 1102-4.

- Öner, N.; et al. The prevalence of folic acid deficiency among adolescent girls living in Edirne, Turkey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2006. 38(5): p. 599-606.

- Bueno, O.; et al. Common Polymorphisms That Affect Folate Transport or Metabolism Modify the Effect of the MTHFR 677C > T Polymorphism on Folate Status123. The Journal of Nutrition, 2016. 146(1): p. 1-8.

- Iglesia, I.; et al. Socioeconomic factors are associated with folate and vitamin B12 intakes and related biomarkers concentrations in European adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence study. Nutrition Research, 2014. 34(3): p. 199-209.

- Rosenthal, J.; et al. Folate and Vitamin B12 Deficiency Among Non-pregnant Women of Childbearing-Age in Guatemala 2009-2010: Prevalence and Identification of Vulnerable Populations. Matern Child Health J, 2015. 19(10): p. 2272-85.

- Kirkpatrick, S.I. and V. Tarasuk, Food Insecurity Is Associated with Nutrient Inadequacies among Canadian Adults and Adolescents123. The Journal of Nutrition, 2008. 138(3): p. 604-612.

- Baltaci, D.; et al. Association of vitamin B12 with obesity, overweight, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, and body fat composition; primary care-based study. Med Glas (Zenica), 2013. 10(2): p. 203-10.

- Sun, Y.; et al. Inverse Association Between Serum Vitamin B12 Concentration and Obesity Among Adults in the United States. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019. 10: p. 414.

- Krishnaveni, G.; et al. Low plasma vitamin B 12 in pregnancy is associated with gestational ‘diabesity’and later diabetes. Diabetologia, 2009. 52: p. 2350-2358.

- Troesch, B.; et al. Increased Intake of Foods with High Nutrient Density Can Help to Break the Intergenerational Cycle of Malnutrition and Obesity. Nutrients, 2015. 7(7): p. 6016-37.

- Siddiqui, M.; et al. Obesity in Pakistan; current and future perceptions. J Curr Trends Biomed Eng Biosci, 2018. 17(2): p. 555958.

- Shabnam, N., N. Aurangzeb, and S. Riaz, Rising food prices and poverty in Pakistan. PLOS ONE, 2023. 18(11): p. e0292071.

- University, O.s. Adolescents. 2012.

- Soofi, S.; et al. Prevalence and possible factors associated with anaemia, and vitamin B 12 and folate deficiencies in women of reproductive age in Pakistan: analysis of national-level secondary survey data. BMJ open, 2017. 7(12): p. e018007.

- Hampstead, V.p.o. Breastfeeding and Vitamin Deficiency. 2017.

- Bae, S.; et al. Vitamin B-12 Status Differs among Pregnant, Lactating, and Control Women with Equivalent Nutrient Intakes. J Nutr, 2015. 145(7): p. 1507-14.

- Shere, M.; et al. Association Between Use of Oral Contraceptives and Folate Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 2015. 37(5): p. 430-438.

- Berenson, A.B. and M. Rahman, Effect of hormonal contraceptives on vitamin B12 level and the association of the latter with bone mineral density. Contraception, 2012. 86(5): p. 481-7.

- Abdullahi, H. and N. Usman, Evaluation of serum Vitamin B12 levels in hormonal contraceptive users in some hospitals in Kano Metropolis. Bayero Journal of Medical Laboratory Science, 2020. 5(2): p. 69-73.

- Sultana, N. Factors influencing contraception choice and use among women of reproductive age in the LMICs of the South Asia region: a scoping review. 2023.

- Pakistan, U. Successes of the SMK Project; Health Families for Pakistan.

| Characteristics | Folate (n=12662) % (95% CIs) |

Vitamin B12 (n=4442) % (95 CIs) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 40.0 (38.9-41.2) | 40.0 (38.3-41.7) |

| Rural | 60.0 (58.8-61.1) | 60.0 (58.3-61.7) |

| Province | ||

| Punjab | 49.7 (48.6-50.8) | 29.9 (28.3-31.6) |

| Sindh | 32.8 (31.7-33.9) | 60.4 (58.7-62.1) |

| KP | 9.5 (9.0-10.0) | 3.3 (2.8-3.9) |

| Baluchistan | 4.1 (3.8-4.3) | 1.8 (1.4-2.2) |

| ICT | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 2.5 (2.1-2.9) |

| KP-NMD | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) |

| AJK | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) |

| GB | 0.4 (0.3-0.4) | 0.1 (0.1-0.1) |

| HH size | ||

| <7 | 56.9 (55.8-58.0) | 57.3 (55.6-58.9) |

| 7 or more members | 43.1 (42.0-44.2) | 42.7 (41.1-44.4) |

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | 19.7 (18.9-20.5) | 27.3 (25.8-28.8) |

| Second | 19.1 (18.2-19.9) | 18.9 (17.6-20.2) |

| Middle | 20.3 (19.4-21.2) | 18.8 (17.5-20.2) |

| Fourth | 21.6 (20.7-22.6) | 18.7 (17.4-20.1) |

| Richest | 19.4 (18.5-20.3) | 16.3 (15.0-17.6) |

| Drinking water source | ||

| Improved sources | 92.2 (91.5-92.9) | 91.3 (90.2-92.2) |

| Unimproved sources | 7.8 (7.1-8.5) | 8.7 (7.8-9.8) |

| Sanitation | ||

| Improved sanitation facility | 83.5 (82.8-84.3) | 76.7 (75.3-78.1) |

| Unimproved sanitation facility | 16.5 (15.7-17.2) | 23.3 (21.9-24.7) |

| Food Insecurity Status | ||

| Food Secure | 59.8 (58.7-60.9) | 54.0 (52.4-55.7) |

| Milld food insecure | 12.5 (11.7-13.2) | 14.6 (13.5-15.9) |

| Moderate food insecure | 8.4 (7.8-9.0) | 10.0 (9.1-11.1) |

| Severe food insecure | 19.4 (18.5-20.3) | 21.3 (20.0-22.7) |

| Age | ||

| 15-19 years | 3.4 (3.0-3.8) | 3.4 (2.9-4.1) |

| 20-34 years | 63.2 (62.1-64.2) | 62.9 (61.3-64.6) |

| 35-49 years | 33.5 (32.4-34.5) | 33.7 (32.1-35.3) |

| Education | ||

| None | 55.7 (54.5-56.8) | 63.2 (61.6-64.9) |

| Primary | 11.5 (10.8-12.3) | 10.4 (9.4-11.4) |

| Middle | 9.0 (8.4-9.6) | 6.9 (6.1-7.8) |

| Secondary | 12.8 (12.1-13.7) | 10.5 (9.4-11.6) |

| Higher | 11.0 (10.3-11.7) | 9.0 (8.1-10.0) |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed | 4.6 (4.2-5.1) | 4.8 (4.2-5.6) |

| Unemployed | 95.4 (94.9-95.8) | 95.2 (94.4-95.8) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Currently Married | 93.3 (92.7-93.8) | 93.9 (93.1-94.7) |

| Ever Married | 1.6 (1.4-2.0) | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) |

| Un-Married | 5.1 (4.6-5.6) | 4.6 (4.0-5.4) |

| BMI of women | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 11.0 (10.4-11.7) | 14.3 (13.2-15.6) |

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 45.9 (44.8-47.0) | 46.1 (44.4-47.8) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 26.9 (25.9-27.9) | 24.8 (23.4-26.4) |

| Obese (>=30) | 16.2 (15.4-17.0) | 14.7 (13.5-15.9) |

| Parity | ||

| <3 | 45.8 (44.7-46.9) | 43.5 (41.8-45.2) |

| >=3 | 54.2 (53.1-55.3) | 56.5 (54.8-58.2) |

| Pregnancy status | ||

| Pregnant | 6.3 (5.8-6.9) | 6.3 (5.5-7.3) |

| Non-Pregnant | 93.7 (93.1-94.2) | 93.7 (92.7-94.5) |

| Minimum dietary diversity | ||

| <5 food groups | 74.7 (73.6-75.7) | 80.2 (78.7-81.6) |

| >=5 food groups | 25.3 (24.3-26.4) | 19.8 (18.4-21.3) |

| Characteristics | Folate (n=6690) Deficiency % (95% CIs) |

Vitamin B12 (n=2693) Deficiency % (95 CIs) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 45.3 (43.4-47.1) | 17.8 (15.8-20.0) |

| Rural | 44.5 (43.1-45.8) | 21.8 (20.1-23.7) |

| Province | ||

| Punjab | 43.4 (41.7-45.0) | 22.9 (20.2-25.8) |

| Sindh | 46.9 (44.9-48.9) | 17.5 (15.9-19.3) |

| KP | 43.5 (40.8-46.4) | 22.4 (16.6-29.4) |

| Baluchistan | 48.7 (45.4-52.1) | 31.8 (23.1-42.0) |

| ICT | 53.6 (45.9-61.1) | 32.8 (25.8-40.6) |

| KP-NMD | 43.6 (36.3-51.2) | 35.4 (26.4-45.6) |

| AJK | 39.1 (34.7-43.6) | 26.5 (18.5-36.5) |

| GB | 40.7 (36.1-45.5) | 37.1 (23.2-53.6) |

| HH size | ||

| <7 | 44.5 (43.0-46.0) | 22.5 (20.7-24.4) |

| 7 or more members | 45.2 (43.5-46.8) | 17.2 (15.3-19.2) |

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | 45.5 (43.2-47.9) | 18.3 (16.0-20.8) |

| Second | 45.1 (42.8-47.5) | 21.1 (18.2-24.4) |

| Middle | 44.9 (42.5-47.4) | 22.7 (19.5-26.3) |

| Fourth | 45.4 (42.9-47.9) | 17.9 (15.1-21.1) |

| Richest | 43.0 (40.3-45.6) | 22.1 (18.8-25.7) |

| Drinking water source | ||

| Improved sources | 44.1 (42.7-45.5) | 22.3 (20.4-24.2) |

| Unimproved sources | 46.2 (43.1-49.4) | 18.8 (15.6-22.5) |

| Sanitation | 47.1 (43.0-51.2) | 16.0 (12.5-20.3) |

| Improved sanitation facility | 45.1 (42.5-47.6) | 17.8 (15.2-20.8) |

| Unimproved sanitation facility | ||

| Food Insecurity Status | 44.5 (43.4-45.7) | 20.3 (19.0-21.8) |

| Food Secure | 47.7 (43.1-52.4) | 18.7 (14.3-24.2) |

| Milld food insecure | ||

| Moderate food insecure | 44.4 (43.2-45.7) | 20.4 (18.9-22.0) |

| Severe food insecure | 46.6 (44.1-49.2) | 19.4 (16.9-22.3) |

| Age | ||

| 15-19 years | 51.3 (45.3-57.3) | 16.1 (10.2-24.5) |

| 20-34 years | 44.1 (42.7-45.5) | 21.1 (19.4-22.9) |

| 35-49 years | 45.4 (43.5-47.3) | 19.0 (16.7-21.4) |

| Education | ||

| None | 45.7 (44.2-47.1) | 20.5 (18.8-22.3) |

| Primary | 42.8 (39.5-46.2) | 18.0 (14.5-22.1) |

| Middle | 44.9 (41.2-48.6) | 18.4 (14.2-23.7) |

| Secondary | 44.3 (41.0-47.7) | 17.3 (13.7-21.7) |

| Higher | 42.8 (39.5-46.2) | 25.4 (20.9-30.4) |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed | 44.0 (38.9-49.2) | 20.0 (14.8-26.4) |

| Unemployed | 44.8 (43.7-46.0) | 20.2 (18.9-21.6) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Currently Married | 44.8 (43.7-46.0) | 20.2 (18.9-21.7) |

| Ever Married | 44.8 (36.3-53.6) | 15.9 (8.2-28.5) |

| Un-Married | 44.3 (39.5-49.2) | 21.0 (15.2-28.1) |

| BMI of women | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 44.6 (41.4-47.8) | 13.3 (10.7-16.5) |

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 44.9 (43.2-46.5) | 18.3 (16.5-20.3) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 44.9 (42.7-47.1) | 24.6 (21.7-27.7) |

| Obese (>=30) | 44.5 (41.8-47.3) | 25.5 (21.9-29.5) |

| Parity | ||

| <3 | 44.7 (43.1-46.4) | 22.3 (20.3-24.5) |

| >=3 | 44.8 (43.3-46.3) | 18.5 (16.9-20.4) |

| Pregnancy status | ||

| Pregnant | 44.0 (39.5-48.6) | 32.2 (25.9-39.3) |

| Non-Pregnant | 44.8 (43.7-46.0) | 19.4 (18.1-20.8) |

| Minimum dietary diversity | ||

| <5 food groups | 45.3 (43.9-46.7) | 19.4 (18.1-20.8) |

| >=5 food groups | 43.9 (41.5-46.3) | 20.6 (17.6-24.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).