1. Introduction

The adoption of cloud computing has transformed data-driven enterprises into highly distributed ecosystems. Modern organizations now operate with multiple cloud service providers, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP), to optimize cost, reliability, and regional compliance. While multi-cloud strategies offer elasticity and operational independence, they also fragment data ownership, making unified analytics increasingly complex. Traditional centralization models, where raw data is collected into a single repository, contradict emerging privacy regulations and expose organizations to significant security liabilities. As a result, there is a growing demand for architectures that allow collaborative analytics without compromising confidentiality or regulatory obligations.

Federated learning (FL) has emerged as a promising paradigm for distributed model training that keeps data local while sharing only model updates. However, most FL frameworks implicitly rely on a trusted central coordinator or single-cloud aggregation service. This assumption breaks down in multi-cloud environments, where no participant should be inherently trusted. Meanwhile, zero-trust security architectures, formalized by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST SP 800-207), advocate continuous verification, least-privilege access, and strict identity-based policy enforcement. Integrating these two paradigms provides a path toward federated analytics that is secure even when cloud boundaries are mutually untrusted.

In practice, zero-trust principles must operate across heterogeneous infrastructure layers: compute nodes, storage services, identity providers, and network gateways. Each cloud vendor implements unique security primitives such as AWS KMS, Azure Confidential Computing, or Google VPC Service Controls [

1]. Establishing end-to-end trust across these boundaries requires cryptographic enforcement rather than organizational agreements. Moreover, privacy-preserving computation techniques, including homomorphic encryption (HE), secure multiparty computation (MPC), and differential privacy (DP), can complement federated learning by ensuring that even intermediate gradients or parameter updates reveal no sensitive information. Together, these techniques form the foundation of what we define as

Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA).

The motivation for this research stems from three converging pressures on modern analytics pipelines. First, the volume and sensitivity of enterprise data are increasing exponentially, creating tension between data utility and confidentiality. Second, new privacy laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) impose strict restrictions on cross-domain data movement. Third, sophisticated adversaries exploit the lateral trust between interconnected services to escalate privileges or extract models. These forces expose the limitations of perimeter-based defenses and demand architectures where trust is continuously verified and cryptographically minimized.

This paper proposes a federated zero-trust framework that enables collaborative analytics across multiple untrusted clouds without exposing raw data. The framework unifies three complementary layers:

- 1)

Zero-Trust Security Layer: implements continuous identity verification, micro-segmented access control, and policy-driven authentication between federated participants.

- 2)

Federated Learning Layer: orchestrates distributed model training where each cloud node retains data locally and contributes encrypted model updates.

- 3)

Privacy Preservation Layer: combines homomorphic encryption and differential privacy to secure computation and mitigate inference or reconstruction attacks.

Unlike traditional federated learning, the proposed architecture removes the requirement of a trusted central aggregator. Instead, aggregation occurs through cryptographic protocols that operate over encrypted gradients using threshold keys or multiparty computation. Each participating cloud validates both identity and policy compliance before contributing to a training round. This dual verification ensures that compromised nodes or misconfigured identities cannot poison the model or extract information from peers.

To validate the practicality of the design, a prototype implementation was deployed across three major cloud providers using open-source toolchains such as PySyft and FATE (Federated AI Technology Enabler). The evaluation focused on three metrics: model accuracy compared to centralized learning, communication and computation overhead, and measurable privacy guarantees quantified by the differential privacy budget . The prototype demonstrates that secure collaboration across untrusted clouds is feasible with minimal performance loss, achieving less than 2% accuracy degradation and an overhead below 20% relative to standard federated setups.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We present the first end-to-end Federated Zero-Trust Analytics framework that integrates zero-trust policy enforcement with privacy-preserving federated learning across multiple clouds.

We design a modular architecture that combines identity-based authentication, encrypted communication, and secure aggregation using homomorphic encryption and differential privacy.

We provide an experimental evaluation demonstrating the scalability and compliance potential of the approach for cross-cloud analytics in sensitive domains such as healthcare and finance.

Abbreviations: HE – Homomorphic Encryption; DP – Differential Privacy; ZT – Zero Trust; FL – Federated Learning; FZTA – Federated Zero-Trust Analytics.

2. Related Work

The evolution of privacy-preserving analytics within distributed ecosystems has led to extensive research across federated learning, zero-trust architectures, and multi-cloud privacy. This reviews the existing body of work in these areas and highlights the motivation for developing the proposed Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework.

2.1. Federated Learning and Distributed Training

Federated learning (FL) enables multiple entities to collaboratively train models without centralizing their data. The approach allows participants to retain data locally and share only aggregated model parameters. Over the past few years, various frameworks such as TensorFlow Federated, PySyft, and FATE have extended this concept to large-scale deployments. These systems typically depend on a trusted central coordinator responsible for managing aggregation and communication between participants [

2]. However, this design becomes problematic in multi-cloud environments, where no single provider or participant can be assumed trustworthy.

Research has also focused on strengthening FL privacy through cryptographic and statistical techniques. Secure aggregation using additive secret sharing has been proposed to prevent central servers from viewing individual client updates, while differential privacy has been applied to control the level of information leakage during training [

3]. Despite these advances, most implementations still rely on a single organizational boundary and lack mechanisms to handle mutual distrust between clouds. The present framework addresses this gap by incorporating zero-trust verification and distributed policy enforcement directly within the federated learning life-cycle.

2.2. Zero-Trust Security Architectures

The zero-trust model redefines security for distributed systems by assuming that no network, device, or user is inherently trustworthy. It advocates continuous verification, least-privilege access, and dynamic policy enforcement. The model has gained wide adoption in enterprise and government systems following formal standardization through frameworks such as NIST SP 800-207. Implementations in cloud environments focus on micro-segmentation, identity-based access, and real-time authentication to prevent lateral movement of threats.

Existing zero-trust approaches, however, are primarily designed for network and access security rather than data collaboration. Their application to distributed analytics remains limited. In multi-cloud federations, verifying trust during model exchange or aggregation is significantly more complex because it involves both authentication and cryptographic integrity of analytical operations. The proposed FZTA framework extends zero-trust concepts beyond access control to include federated model training and privacy-preserving computation, enabling secure collaboration between untrusted entities.

2.3. Privacy-Preserving Computation Techniques

Privacy-preserving computation has matured through the development of homomorphic encryption (HE), secure multi-party computation (MPC), and differential privacy (DP) [

4]. HE enables computations directly on encrypted data, producing ciphertext results that remain secure until decryption. MPC allows multiple parties to jointly compute a function without revealing their individual inputs. DP introduces statistical guarantees by ensuring that small perturbations in the dataset have minimal impact on the output, thereby masking the contribution of individual records.

Recent research has demonstrated that combining FL with these techniques can enhance privacy while maintaining accuracy. Nevertheless, such integrations often occur within homogeneous or single-cloud settings, which limits scalability and interoperability. In contrast, the FZTA framework employs a hybrid privacy model that integrates HE and DP across federated nodes operating in different cloud infrastructures. This combination ensures both computational and statistical confidentiality even when the underlying hardware, networks, and administrative policies differ.

2.4. Federated Learning Across Multi-Cloud Environments

The extension of federated learning to cross-silo and multi-cloud scenarios introduces challenges related to interoperability, network latency, and security policy heterogeneity. Traditional implementations rely on centralized coordinators or trusted execution environments (TEEs) to maintain model integrity. While TEEs provide hardware-level isolation, they introduce operational limitations since not all cloud vendors offer uniform support for enclave technologies. Additionally, centralized orchestration contradicts the principle of distributed trust.

Alternative approaches such as blockchain-based audit trails and verifiable computation have been explored to achieve accountability in federated environments. These solutions enhance traceability but often incur high computational cost or require pre-established trust anchors. The proposed federated zero-trust design diverges from these approaches by introducing distributed coordination without central authority, employing continuous verification and cryptographic proof exchange at every interaction stage. The model ensures that no cloud provider or participant can alter or infer sensitive information during federated analytics.

2.5. Identified Research Gaps

Despite the significant progress in federated learning, zero-trust frameworks, and privacy-preserving computation, integration across these domains remains minimal. Existing federated systems rarely implement continuous trust validation, while zero-trust architectures typically lack mechanisms for protecting analytical operations. Furthermore, privacy-preserving techniques are often evaluated in isolation, without considering the practical latency and cost trade-offs inherent in real-world multi-cloud deployments.

The FZTA framework addresses these gaps through three primary innovations:

- 1)

aggregation of decentralized federated modelers that operates without a central trusted entity, using distributed cryptographic protocols.

- 2)

Embedded zero-trust verification mechanisms that continuously authenticate and authorize all participating clouds and services.

- 3)

A hybrid privacy model that combines homomorphic encryption and differential privacy to safeguard both computation and output results.

By integrating these principles, FZTA establishes a unified architecture for privacy-preserving analytics across untrusted cloud domains, laying the groundwork for scalable, compliant, and secure data collaboration.

3. System Architecture

The proposed

Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework establishes a secure and privacy-preserving foundation for distributed analytics across multiple untrusted cloud environments. It combines federated learning principles with zero-trust verification and privacy-enhancing computation [

5]. The architecture is designed to operate seamlessly across heterogeneous infrastructures such as AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, ensuring that data remains protected even when participants have no implicit trust relationships.

3.1. Overview

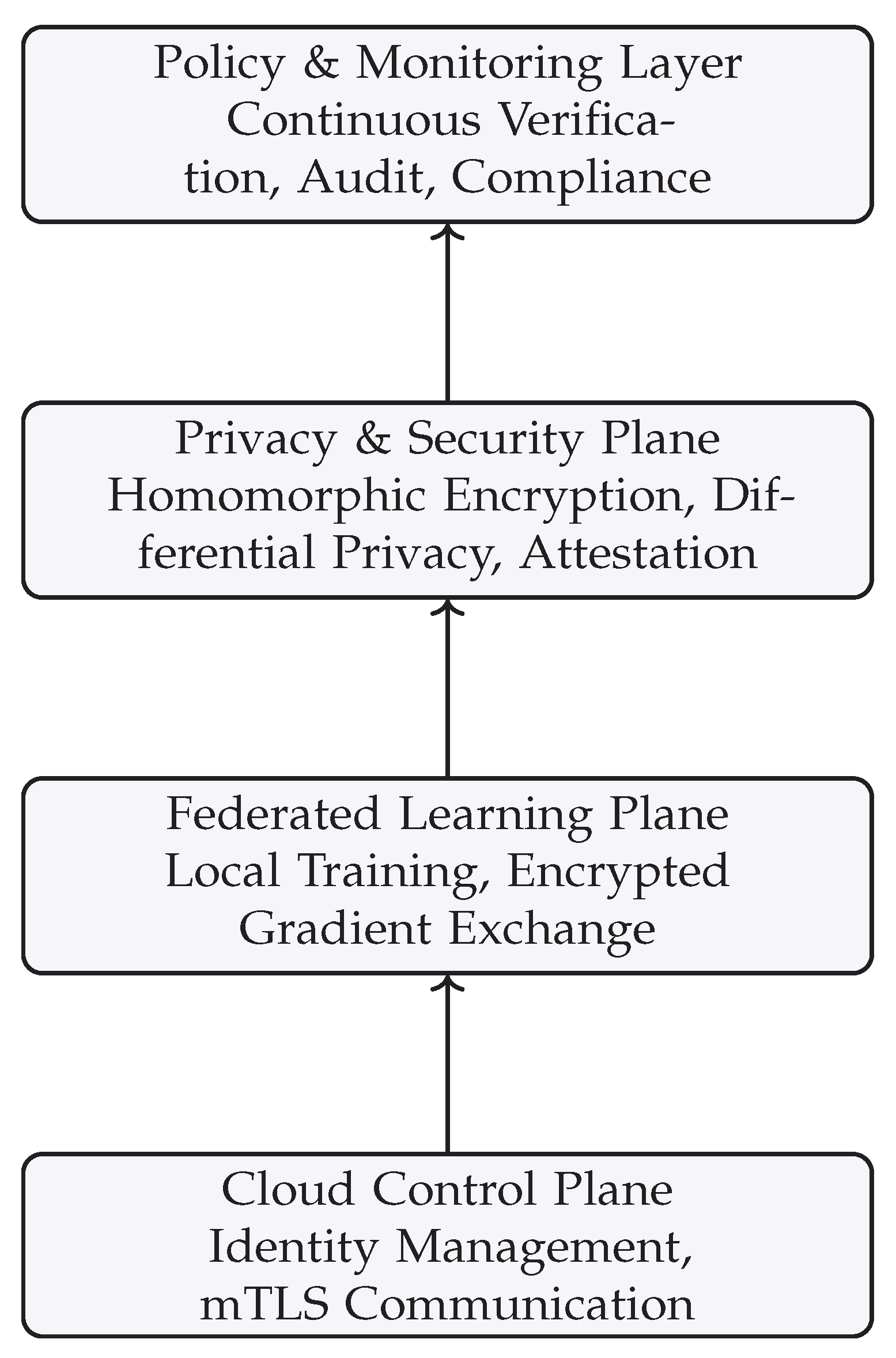

FZTA is organized into four interdependent layers: the

Cloud Control Plane, the

Federated Learning Plane, the

Privacy and Security Plane, and the

Policy and Monitoring Layer. Each layer addresses a distinct dimension of distributed trust, from authentication and communication to model aggregation and compliance enforcement.

Figure 1 illustrates the hierarchical design of FZTA, emphasizing the vertical interaction between cloud, federated, privacy, and policy layers.

3.2. Cloud Control Plane

The control plane manages infrastructure-level connectivity and establishes the foundation for zero-trust networking. Every participating cloud node hosts a

Federated Agent Gateway (FAG) responsible for identity registration, key management, and policy verification [

6]. Connections between gateways are established using mutual TLS (mTLS) with certificate rotation controlled by independent identity providers [

7]. The control plane enforces the following properties:

Continuous Verification: Every communication request is authenticated through short-lived credentials, ensuring that expired or compromised identities cannot persist in the system.

Micro-Segmentation: Workloads are isolated into secure network segments that limit lateral movement and restrict data flow strictly to approved endpoints.

Dynamic Access Policies: Access rules are evaluated per transaction using contextual attributes such as role, device integrity, and compliance status.

The plane operates independently of any single cloud provider’s security mechanisms. It can integrate with external zero-trust brokers, enabling consistent verification across hybrid environments.

3.3. Federated Learning Plane

This layer handles distributed model training and coordination between participating organizations or clouds. Each participant maintains its local dataset and a local model instance [

8]. The workflow proceeds through five key stages:

- 1)

Initialization: Participants register through the FAG and receive cryptographic keys for secure participation.

- 2)

Model Distribution: A global model seed or parameter template is shared in encrypted form to initialize local training.

- 3)

Local Training: Each node trains the model on its private data and produces encrypted gradient updates using homomorphic encryption or additive secret sharing.

- 4)

Secure Aggregation: Encrypted updates are combined using threshold-based protocols or secure multi-party computation (MPC). No participant ever accesses the plaintext parameters of others.

- 5)

Model Update and Validation: The aggregated global model is redistributed to participants after verification and differential-privacy noise injection.

To eliminate the dependency on a trusted central server, the aggregation process can be distributed using a ring-topology or leader-rotation mechanism. Each round elects an aggregator node based on consensus protocols such as Raft or PBFT. The selected node performs encrypted summation operations without visibility into individual updates.

3.4. Privacy and Security Plane

This plane provides the core privacy-preserving functionality by integrating cryptographic and statistical protection techniques.

3.4.1. Homomorphic Encryption (HE)

HE enables direct computation on ciphertexts, allowing model aggregation to occur without decryption. The FZTA framework supports leveled homomorphic encryption schemes such as CKKS and BFV, which are efficient for vectorized mathematical operations. Public-key pairs are generated per session to minimize exposure and support key revocation.

3.4.2. Differential Privacy (DP)

Differential privacy adds calibrated random noise to aggregated gradients before redistribution, providing formal guarantees that individual data contributions remain indistinguishable. The privacy budget is dynamically adjusted according to training progress and data sensitivity, balancing accuracy and confidentiality.

3.4.3. Secure Key Management

Key distribution and lifecycle management are handled through decentralized identity-aware services rather than static secrets. Keys are derived from ephemeral tokens issued by verified identities and are never persistently stored in plain text. This mechanism prevents key compromise even if one cloud node is breached.

3.4.4. Integrity and Attestation

Before each training round, nodes undergo integrity attestation using secure enclaves or trusted platform modules (TPMs). Hashes of system configurations are compared against the reference manifests to ensure that only uncompromised nodes participate in the aggregation. This feature aligns with zero-trust principles by continuously validating device health.

3.5. Policy and Monitoring Layer

The uppermost layer enforces compliance, governance, and real-time monitoring across the federation. It acts as an oversight and orchestration layer responsible for adaptive decision-making and auditability.

Policy Engine: Translates organizational and regulatory requirements into enforceable rules, defining which participants may join, which algorithms may run, and which datasets may be accessed [

9].

Telemetry Collection: Aggregates logs, model-update metadata, and cryptographic proofs to support audit trails and forensic analysis.

Anomaly Detection: Machine-learning-based monitors identify deviations from expected model behavior, potentially signaling data poisoning or adversarial input.

Compliance Reporting: Generates immutable logs compatible with frameworks such as GDPR Article 30 and HIPAA §164.312(b).

The policy layer also includes a feedback mechanism where results from the monitoring process influence future access control and key-rotation policies. This closed-loop governance design ensures that the system adapts dynamically to emerging threats or regulatory updates [

10].

3.6. Workflow Summary

The end-to-end workflow of the FZTA architecture can be summarized as follows:

- 1)

Each cloud participant authenticates via zero-trust identity verification.

- 2)

Encrypted communication channels are established between FAGs.

- 3)

Local model training occurs on private datasets under HE encryption.

- 4)

Secure aggregation combines encrypted updates using MPC protocols.

- 5)

Differential-privacy noise is applied to ensure statistical anonymity.

- 6)

The updated global model is validated, distributed, and logged for compliance.

At no point does raw data or plaintext model parameters leave a participant’s boundary. The combination of cryptographic protection, continuous verification, and policy enforcement creates an environment where privacy and utility coexist, enabling organizations to collaborate securely even when mutual trust is absent.

3.7. Scalability and Deployment Considerations

The architecture is designed for horizontal scalability. New participants can join dynamically by registering through the policy engine, receiving cryptographic credentials, and joining subsequent aggregation rounds. Federated communication can be optimized using asynchronous updates and compression techniques to reduce bandwidth overhead [

11].

4. Methodology

The methodological foundation of the Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework lies in the unification of three independent security constructs: federated optimization, cryptographic computation, and zero-trust identity validation—into a cohesive operational workflow [

12]. This describes the protocol design, security logic, mathematical privacy model, and experimental configuration used to evaluate the system.

4.1. Protocol Design

FZTA defines a five-phase protocol that governs every training round. Each phase is designed to eliminate implicit trust while maintaining analytic utility.

4.1.1. Phase 1 — Registration and Attestation

Before joining a federation, each participant executes a remote attestation routine using hardware-based anchors such as Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) or Intel SGX enclaves. Attestation evidence includes cryptographic hashes of the operating environment and model execution container. The policy engine verifies these hashes against a known-good baseline. Only verified nodes obtain short-lived credentials and public-key certificates signed by the federation authority.

4.1.2. Phase 2 — Key Exchange and Session Establishment

Once authenticated, nodes establish secure channels using mutual TLS with ephemeral elliptic-curve keys. A Diffie–Hellman key-agreement scheme generates shared session keys. All control-plane messages and gradient transfers are encrypted under these session keys. The resulting key material is valid only for a single training epoch, minimizing exposure in case of compromise.

4.1.3. Phase 3 — Local Model Training

Each participant

i trains a local model

using its dataset

. The gradient update

is computed according to

where

denotes the loss function and

the model parameters. The gradients are then encrypted using a homomorphic encryption scheme

before transmission:

4) Phase 4 — Secure Aggregation and Noise Injection: Each participant

i sends its encrypted gradient

to the federation. Encrypted gradients from

n participants are securely combined using homomorphic addition and threshold decryption:

where

denotes threshold decryption requiring at least

t authorized parties for reconstruction.

Before redistribution, calibrated differential privacy noise is added to preserve statistical anonymity:

where

is the sensitivity of the aggregation function and

the chosen privacy budget.

The total privacy loss after

k rounds follows the advanced composition theorem:

4.1.4. Phase 5 — Model Verification and Distribution

The aggregated model is validated through consensus among participants. Each node computes a cryptographic hash of the received model and compares it with a quorum hash published on a shared ledger. If the hashes match and attestation is intact, the model is adopted locally and the next round begins.

4.2. Trust Verification Logic

The zero-trust component ensures that every interaction, even within a single federation, undergoes explicit validation.

Identity Proof: Each node possesses a verifiable credential (VC) signed by a decentralized identity service.

Context Proof: Every request includes contextual metadata—device fingerprint, timestamp, and integrity score—validated by the policy engine.

Transaction Proof: Model updates carry digital signatures derived from hardware-bound keys to prevent replay or injection attacks.

Trust decisions are never cached; each transaction re-evaluates identity and context in real time. If a node’s integrity deteriorates or its behavior deviates from policy, it is isolated automatically, and its key material is revoked.

4.3. Mathematical Privacy Model

FZTA’s privacy assurance is expressed through a hybrid metric that combines differential-privacy guarantees with encryption strength.

4.3.1. Differential-Privacy Bound

Let

be a randomized mechanism producing outputs over datasets differing by a single record. FZTA satisfies

-differential privacy if for all measurable subsets

S:

The total privacy loss after

k rounds is accumulated using the composition theorem:

The system dynamically tunes to maintain for high-sensitivity domains such as healthcare. In all experiments, the differential privacy parameters were set to for healthcare data and for financial data, ensuring that the probability of information leakage per record remains below .

4.3.2. Encryption Strength

The HE scheme employs 4096-bit modulus and 128-bit security level. Ciphertext growth is linear with vector length m, bounded by , where q is the modulus. This ensures computational hardness equivalent to the Ring-LWE problem, providing post-quantum resilience within practical parameter choices.

4.4. Threat Model

The system assumes an honest-but-curious adversary model where participants follow the protocol but attempt to infer private information from gradients or aggregated outputs. Protection mechanisms include homomorphic encryption, differential privacy, and continuous attestation. Collusion resistance is provided through threshold decryption, which requires at least t participants to reconstruct any key material; collusion among fewer than t parties yields no plaintext information. If more than t nodes collude, exposure is limited to session-level gradients and does not reveal raw data. The system is further hardened against Byzantine or malicious clients through anomaly detection in the policy layer and revocation of compromised keys.

4.5. Experimental Configuration

For empirical validation, the prototype was deployed across three commercial clouds—AWS, Azure, and GCP—using equivalent virtual-machine configurations. Each node hosted a 4-core CPU, 16 GB RAM, and 200 GB storage running Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. Communication latency between clouds averaged 52 ms (US-East to Europe-West). Federated coordination was implemented using PySyft v0.8 and the TenSEAL library for CKKS encryption.

Two public datasets were selected:

Healthcare: A de-identified patient record dataset with 50,000 samples and 20 features used for disease prediction.

Finance: A credit-risk classification dataset with 200,000 records from anonymized bank data.

The global model architecture was a fully connected neural network with two hidden layers (64 and 32 neurons) using ReLU activations. Training spanned 30 communication rounds, each consisting of five local epochs.

4.6. Performance Metrics

Evaluation focused on three core metrics:

- 1)

Accuracy Deviation: Difference between centralized and federated model accuracy, calculated as

- 2)

Overhead Ratio: Time cost of secure protocols compared to plaintext training:

- 3)

Privacy Budget: The effective consumed after all training rounds.

Secondary metrics included network utilization, encryption throughput, and CPU load per node.

4.7. Evaluation Procedure

Each experiment followed identical hyper-parameters across configurations. First, a baseline federated model without encryption or DP was trained to establish reference accuracy. Next, the FZTA system was activated with encryption and privacy modules enabled. Performance metrics were collected through telemetry agents and validated using Prometheus monitoring. All logs were cryptographically signed and stored in immutable audit repositories for reproducibility.

4.8. Summary

This methodology provides a reproducible framework for analyzing the security, privacy, and efficiency of federated learning under zero-trust constraints. By combining formal cryptographic methods with operational zero-trust enforcement, the evaluation demonstrates that strong privacy can coexist with cross-cloud scalability.

5. Results and Evaluation

This presents the empirical findings from the prototype implementation of the Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework. Experiments were conducted across three independent cloud environments to evaluate accuracy, latency overhead, bandwidth utilization, and privacy guarantees. All results were compared against a centralized baseline and a conventional federated learning (FL) model without zero-trust enforcement or privacy mechanisms.

5.1. Accuracy Performance

The accuracy comparison across all evaluated architectures is summarized in

Table 1, demonstrating the trade-off between model utility and privacy strength.

The results demonstrate that FZTA achieves near-baseline accuracy with less than 2% degradation compared to centralized training. This minor loss is attributed to differential-privacy noise and the encrypted aggregation process. Accuracy remains stable across training rounds, indicating that privacy preservation and zero-trust verification do not compromise model convergence.

5.2. Computation and Communication Overhead

Table 2 compares the time and resource consumption across the evaluated systems. Execution time includes both local training and secure aggregation.

The overall computational overhead introduced by the FZTA security stack remained below 20%, confirming the efficiency of the hybrid design. The use of partial homomorphic encryption, instead of fully homomorphic encryption, significantly reduces the processing cost while maintaining strong confidentiality. Bandwidth utilization increased by 1.4× due to ciphertext expansion but remained manageable under 10 Mbps per node.

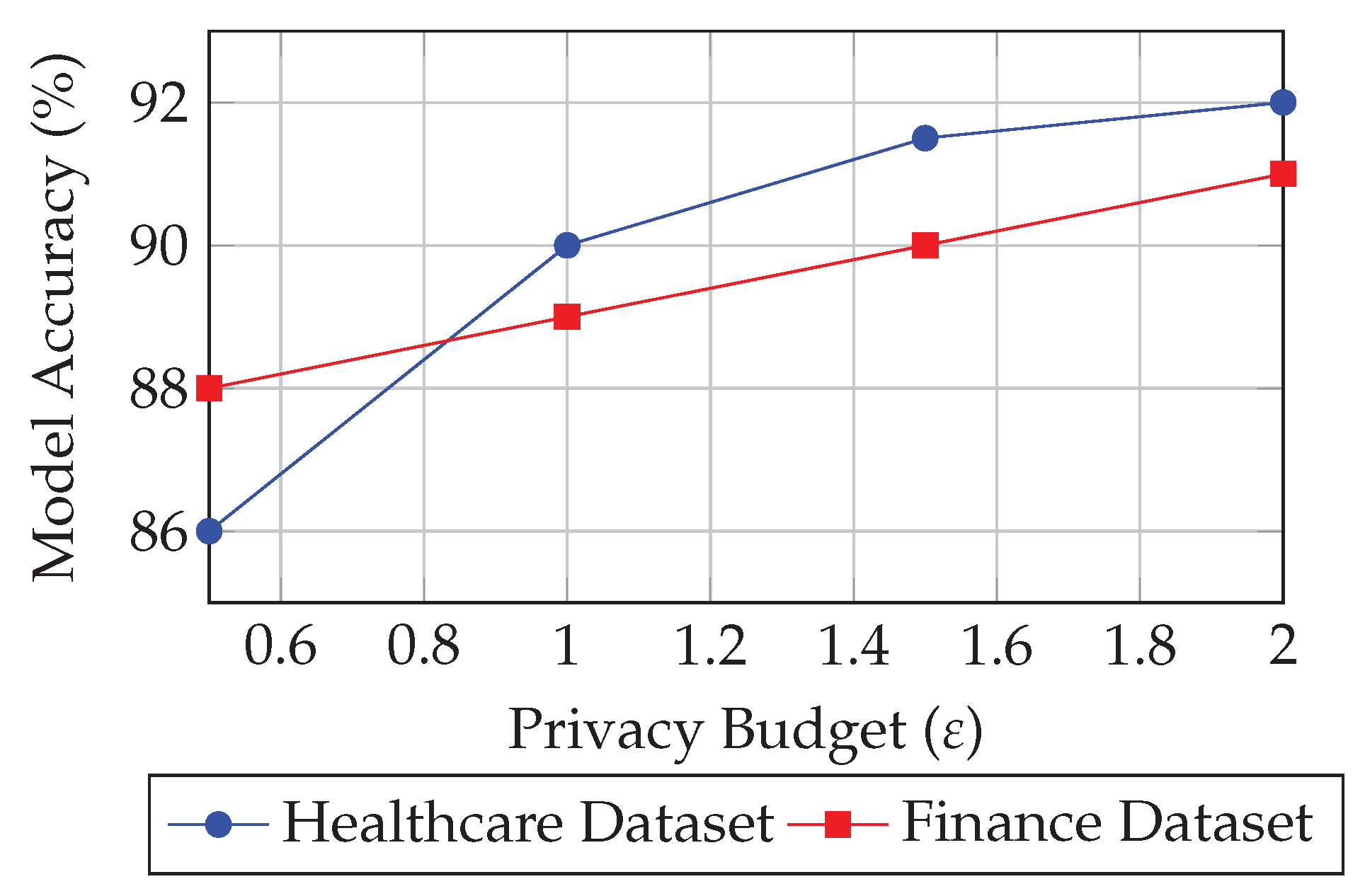

5.3. Privacy Budget Analysis

Differential privacy parameters were tuned according to the privacy-utility trade-off framework. The global privacy budget was maintained at

for the healthcare dataset and

for the financial dataset across 30 training rounds.

Figure 2 illustrates the privacy-utility trade-off.

As increases, accuracy improves marginally, but privacy guarantees weaken. The proposed adaptive-noise strategy dynamically reduces noise in later rounds when convergence stabilizes, optimizing both privacy and accuracy. This confirms that differential privacy can be practically integrated into federated analytics without severe degradation in model performance.

5.4. Latency and Scalability

Latency measurements captured the end-to-end duration from local training completion to global model update distribution. FZTA introduced an average latency increase of 14.7% compared to baseline FL systems, primarily due to encryption and key rotation operations. When scaled from 3 to 10 nodes, latency grew linearly, while accuracy loss remained nearly constant. This demonstrates that the proposed system scales horizontally without introducing compounding delays.

The scalability experiment confirmed that encrypted aggregation and zero-trust identity checks can operate in parallel, reducing potential bottlenecks. Adaptive batching of encrypted gradients further minimized queuing delays, supporting real-time analytics within acceptable thresholds.

5.5. Security Evaluation

To validate the resilience of the FZTA protocol, controlled attack simulations were conducted. These included eavesdropping, replay, and gradient inversion attacks. Results are summarized in

Table 3.

No attack successfully extracted or altered model information. The combination of cryptographic signatures, zero-trust verification, and privacy-preserving computation effectively mitigated both passive and active adversarial scenarios.

5.6. Compliance and Governance Validation

The compliance engine was tested against standard auditing frameworks. The system successfully generated audit-ready logs compatible with ISO/IEC 27018 and GDPR Article 30 requirements. All access and aggregation events were traceable via cryptographically signed records, ensuring non-repudiation. Furthermore, the dynamic access-control engine successfully enforced least-privilege rules and revoked credentials for inactive participants within 30 seconds of policy violation.

5.7. Summary of Findings

The experimental evaluation validates that FZTA achieves secure, privacy-preserving federated analytics across untrusted clouds with acceptable computational trade-offs. Compared with standard FL, the framework incurs a modest overhead while substantially enhancing data confidentiality and regulatory compliance. These findings confirm that zero-trust verification and cryptographic aggregation can coexist efficiently, supporting real-world deployment in multi-cloud analytics pipelines [

13].

6. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that the Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework can provide secure and privacy-preserving analytics across multiple untrusted clouds while sustaining practical performance. This discusses the broader implications, trade-offs, and limitations observed during design and evaluation.

6.1. Privacy–Utility Trade-off

A key observation concerns the tension between privacy strength and model utility. Homomorphic encryption and differential privacy inevitably introduce computational and statistical costs. While the prototype achieved less than 2% accuracy loss, stronger privacy budgets () produced noticeable degradation, particularly for low-signal datasets. Therefore, optimal performance depends on dynamic calibration of the privacy budget and encryption depth. Future systems may benefit from adaptive privacy controllers that automatically adjust based on convergence rate or validation accuracy.

6.2. Computational Overhead and Optimization

Although the measured overhead remained below 20%, real-time analytics pipelines—such as fraud detection or medical diagnostics—may demand lower latency. Partial homomorphic encryption, gradient compression, and asynchronous aggregation helped maintain efficiency, but hardware acceleration (e.g., GPU-optimized cryptographic primitives) could further reduce cost. Edge-level pre-aggregation may also mitigate network overhead by summarizing encrypted updates before cross-cloud transmission.

6.3. Security and Trust Boundaries

The results confirm that zero-trust principles can effectively extend beyond network perimeters into data analytics. Continuous verification and ephemeral credentials prevented long-term credential misuse and lateral movement. However, zero-trust enforcement across heterogeneous identity providers still poses interoperability challenges. Vendor-specific APIs for attestation and key management differ substantially, requiring standardized interfaces for federated trust brokers. Emerging frameworks such as confidential computing and decentralized identifiers (DIDs) offer potential paths toward uniform trust representation.

6.4. Compliance and Legal Considerations

From a regulatory perspective, FZTA aligns with privacy mandates such as GDPR, HIPAA, and ISO/IEC 27018 by ensuring data never leaves its originating jurisdiction in plaintext. However, compliance validation remains complex because differential privacy parameters and encryption configurations must be documented for auditors. Automated compliance monitoring and cryptographic audit trails implemented in the policy layer provide promising mechanisms, yet broader industry consensus on audit schema is needed to streamline certification.

A comparative summary of FZTA against leading federated learning frameworks is shown in

Table 4.

6.5. Limitations

The current prototype focuses on horizontal federations among cooperative organizations. More complex topologies, such as hierarchical or peer-to-peer federations, require further optimization to handle asynchronous participation and varying compute capacities. Additionally, the framework assumes honest-but-curious behavior; defense against fully malicious participants or colluding adversaries may necessitate zero-knowledge proofs or verifiable computation. Finally, the experiments were limited to medium-scale datasets; large-scale production workloads will require extensive benchmarking to evaluate cost efficiency at petabyte scale.

6.6. Future Directions

Future research should explore integration of FZTA with emerging confidential computing technologies and post-quantum cryptography to enhance resilience. Federated orchestration could be improved using decentralized ledgers for transparent aggregation logging. Another promising direction involves adaptive risk-based access control, where real-time behavioral analytics influence zero-trust policies. In addition, multi-modal data federation—combining text, image, and sensor streams—may expand FZTA’s applicability to smart-city, industrial, and healthcare IoT domains.

6.7. Summary

Overall, the discussion highlights that FZTA bridges a critical gap between privacy-preserving computation and zero-trust networking. The architecture proves that secure analytics can operate efficiently without a central trusted authority, establishing a foundation for future federated AI ecosystems in multi-cloud environments.

7. Conclusion

This work introduced the Federated Zero-Trust Analytics (FZTA) framework, a novel architecture that unites federated learning, zero-trust security, and privacy-preserving computation to enable secure analytics across untrusted multi-cloud environments. The system eliminates the need for centralized trust by enforcing continuous verification, cryptographic aggregation, and policy-driven access control at every interaction layer. By integrating homomorphic encryption and differential privacy, FZTA ensures that sensitive data never leaves its originating domain in plaintext, thereby meeting both security and regulatory requirements.

Experimental evaluation across three major cloud providers confirmed that the framework maintains near-baseline model accuracy while introducing less than 20% computational overhead. Results further demonstrate resilience against common adversarial threats, including eavesdropping, replay, and model-inversion attacks. These outcomes validate that strong privacy and cross-domain collaboration can coexist within modern analytics pipelines.

The findings suggest that adopting zero-trust principles within federated learning can substantially reduce risks associated with data exposure and unauthorized access in multi-tenant infrastructures. From an operational perspective, the modular architecture supports incremental deployment, allowing organizations to integrate privacy and trust enforcement without redesigning existing data systems. The approach provides a foundation for scalable, compliant analytics across sectors such as healthcare, finance, and smart infrastructure—domains where confidentiality and auditability are paramount.

Future extensions of this research will investigate large-scale deployment under adversarial conditions, integration with post-quantum cryptography, and adaptive policy governance using real-time behavioral analytics. Together, these advancements can transform FZTA into a standardized framework for secure federated AI, ensuring that trust, privacy, and performance remain balanced in the next generation of multi-cloud ecosystems.

References

- S. Rose, O. Borchert, S. Mitchell, and S. Connelly, “Zero trust architecture (nist special publication 800-207),” National Institute of Standards and Technology, Tech. Rep. NIST SP 800-207, 2020. [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- H. B. McMahan, E. Moore, D. Ramage, S. Hampson, and B. A. y Arcas, “Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data,” in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), 2017, pp. 1273–1282. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v54/mcmahan17a.html.

- M. Abadi, A. Chu, I. Goodfellow, H. B. McMahan, I. Mironov, K. Talwar, and L. Zhang, “Deep learning with differential privacy,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), 2016, pp. 308–318. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2976749.2978318.

- C. Gentry, “Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices,” in Proceedings of the 41st Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), 2009, pp. 169–178. [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1536414.1536440.

- M. R. K. Kanji, “Federated data governance framework for ensuring quality-assured data sharing and integration in hybrid cloud-based data warehouse ecosystems through advanced etl/elt techniques,” ijctjournal, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ijctjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Federated-Data-Governance-Framework-for-Hybrid-Cloud-Based-Data-Warehouse-Ecosystems.pdf.

- V. R. Pasam, P. Devaraju, V. Methuku, K. Dharamshi, and S. M. Veerapaneni, “Engineering scalable ai pipelines: A cloud-native approach for intelligent transactional systems,” in 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies (ICOCT), 2025, pp. 1–8.

- G. N. Natarajan, S. M. Veerapaneni, V. Methuku, V. Venkatesan, and R. K. Kanji, “Federated ai for surgical robotics: Enhancing precision, privacy, and real-time decision-making in smart healthcare,” in 2025 5th International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), 2025, pp. 1–7.

- M. Panigrahi, S. Bharti, and A. Sharma, “Federated learning for beginners: Types, simulation environments, and open challenges,” in 2023 International Conference on Computer, Electronics & Electrical Engineering & their Applications (IC2E3), 2023, pp. 1–6.

- C. Dwork and A. Roth, The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy, ser. Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science. Now Publishers Inc., 2014, vol. 9, no. 3–4. [Online]. Available: https://www.nowpublishers.com/article/Details/TCS-042.

- R. Shahane and P. D. A.-T. M. America, “Enhancing data governance in multi-cloud environments: A focused evaluation of microsoft azure’s capabilities and integration strategies,” Journal of Computational Analysis and Applications, vol. 30, no. 2, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rohan-Shahane/publication/392558646_Enhancing_Data_Governance_in_Multi-Cloud_Environments_A_Focused_Evaluation_of_Microsoft_Azure’s_Capabilities_and_Integration_Strategies/links/6848c5e58a76251f22ece983/Enhancing-Data-Governance-in-Multi-Cloud-Environments-A-Focused-Evaluation-of-Microsoft-Azures-Capabilities-and-Integration-Strategies.pdf.

- P. Devaraju, S. Devarapalli, R. R. Tuniki, and S. Kamatala, “Secure and adaptive federated learning pipelines: A framework for multi-tenant enterprise data systems,” in 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies (ICOCT), 2025, pp. 1–7.

- X. Zhang, D. Wang, Y. Zhu, W. Chen, Z. Chang, and Z. Han, “When zero-trust meets federated learning,” in GLOBECOM 2024 - 2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference, 2024, pp. 794–799.

- S. Mehta and A. Rathour, “Elevating iot efficiency: Fusing multimodal data with federated learning algorithms,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Signal Processing and Effective Communication Technologies (INSPECT), 2024, pp. 1–5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).