Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

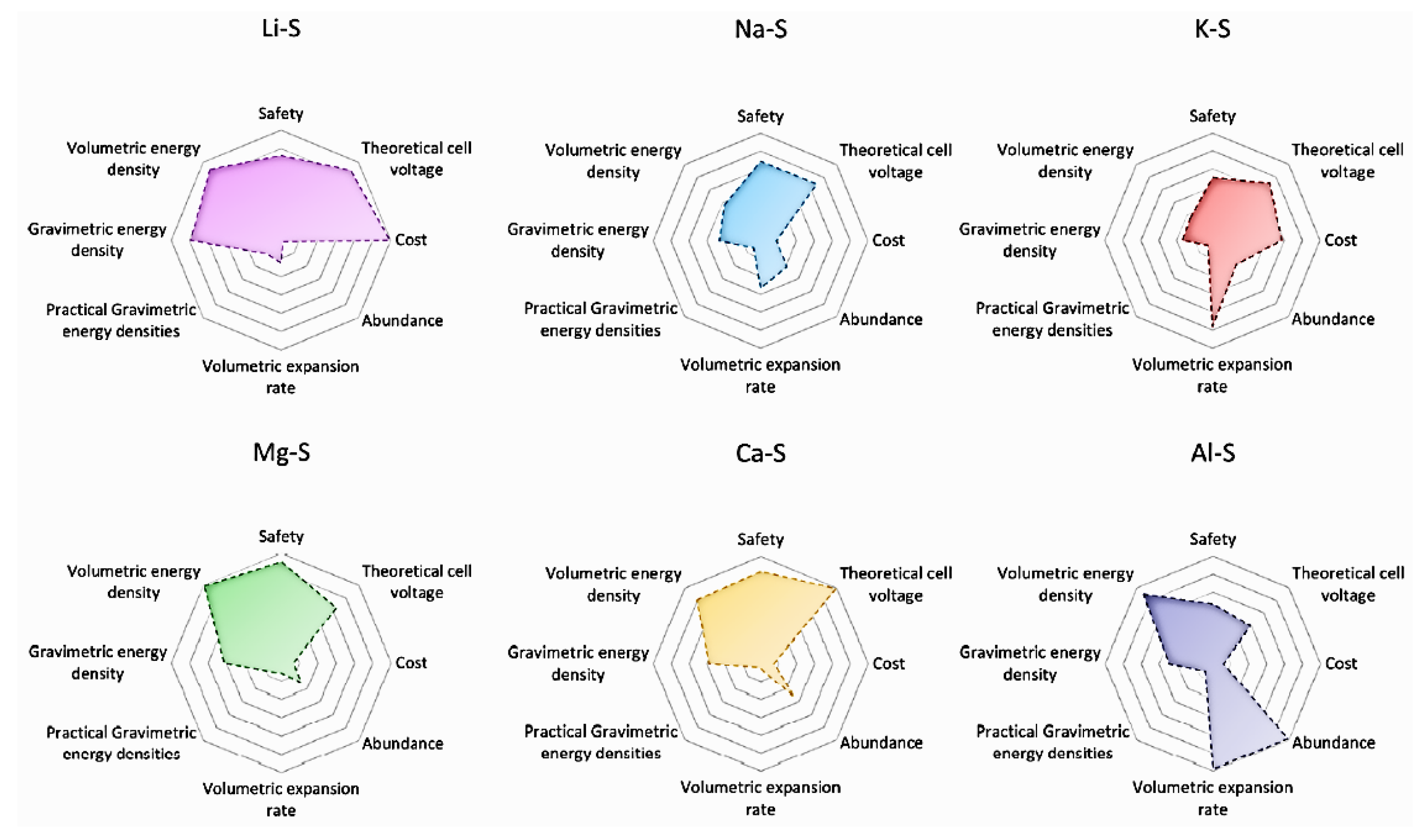

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices

3. Magnesium-Sulfur (Mg-S) Battery

4. Mg-S Battery Configuration and Mechanism of Operation

4.1. Electrolytes

4.2. Separator

4.3. Electrodes

4.3.2. Magnesium Anode

4.3.3. Sulfur Cathode

4.4. Reaction Mechanism of Mg-S Batteries

4.5. Controlling Polysulfide Shuttle Effect in Mg-S Batteries

5. Monitoring the Reaction Mechanism of Mg-S Batteries

6. Importance of Electrode Materials

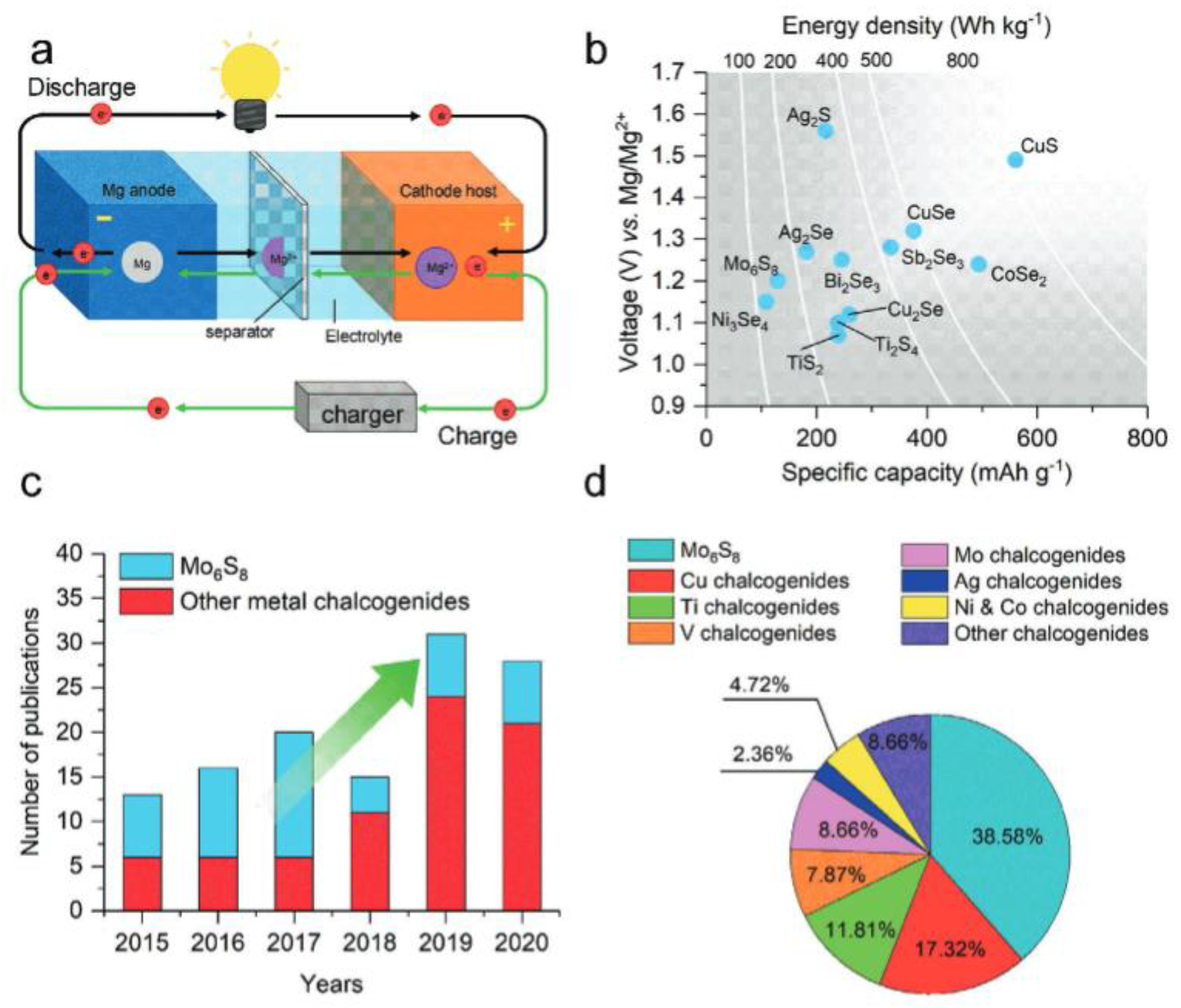

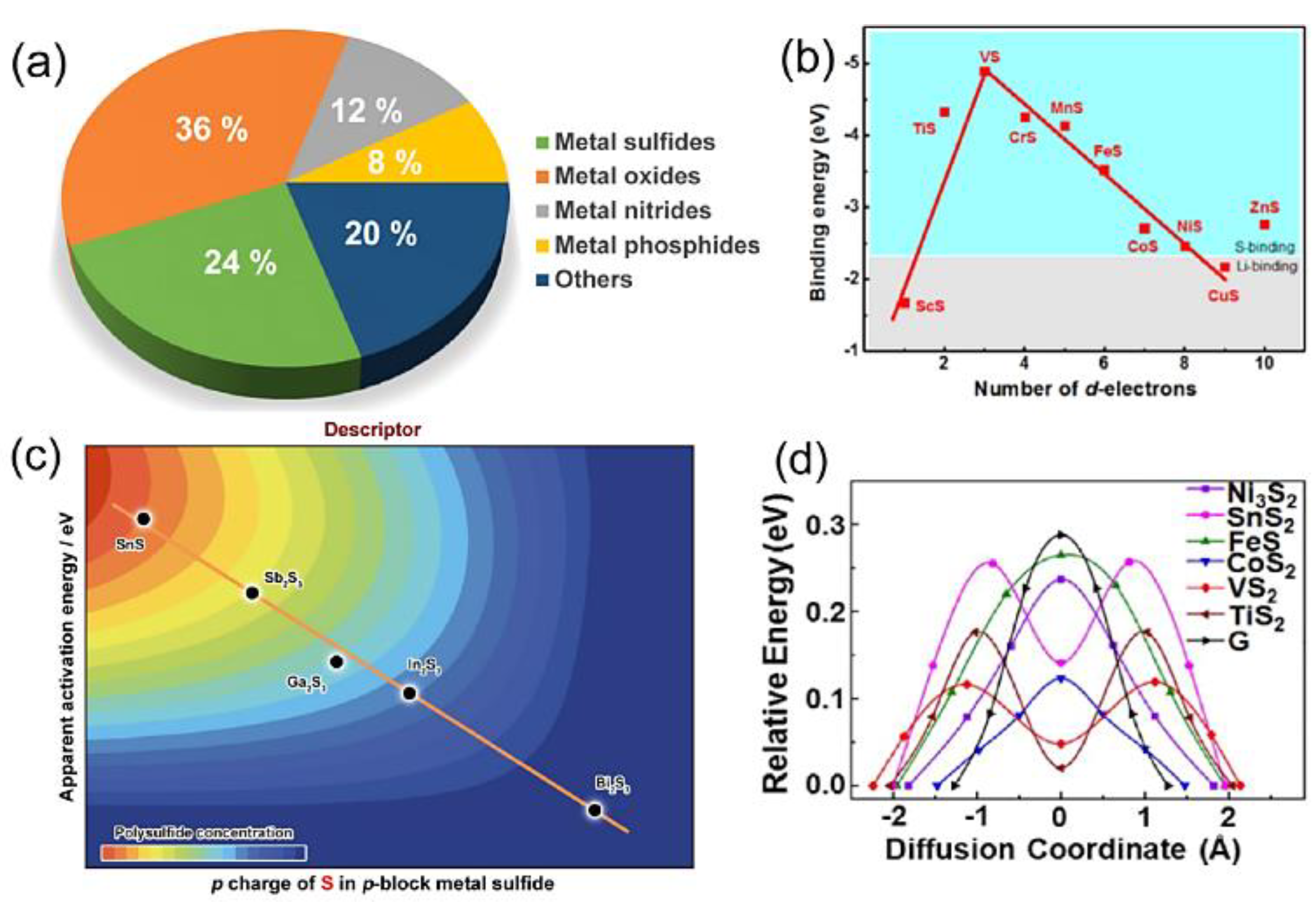

7. Metal Chalcogenides-Based Cathode Materials for Mg-S Batteries

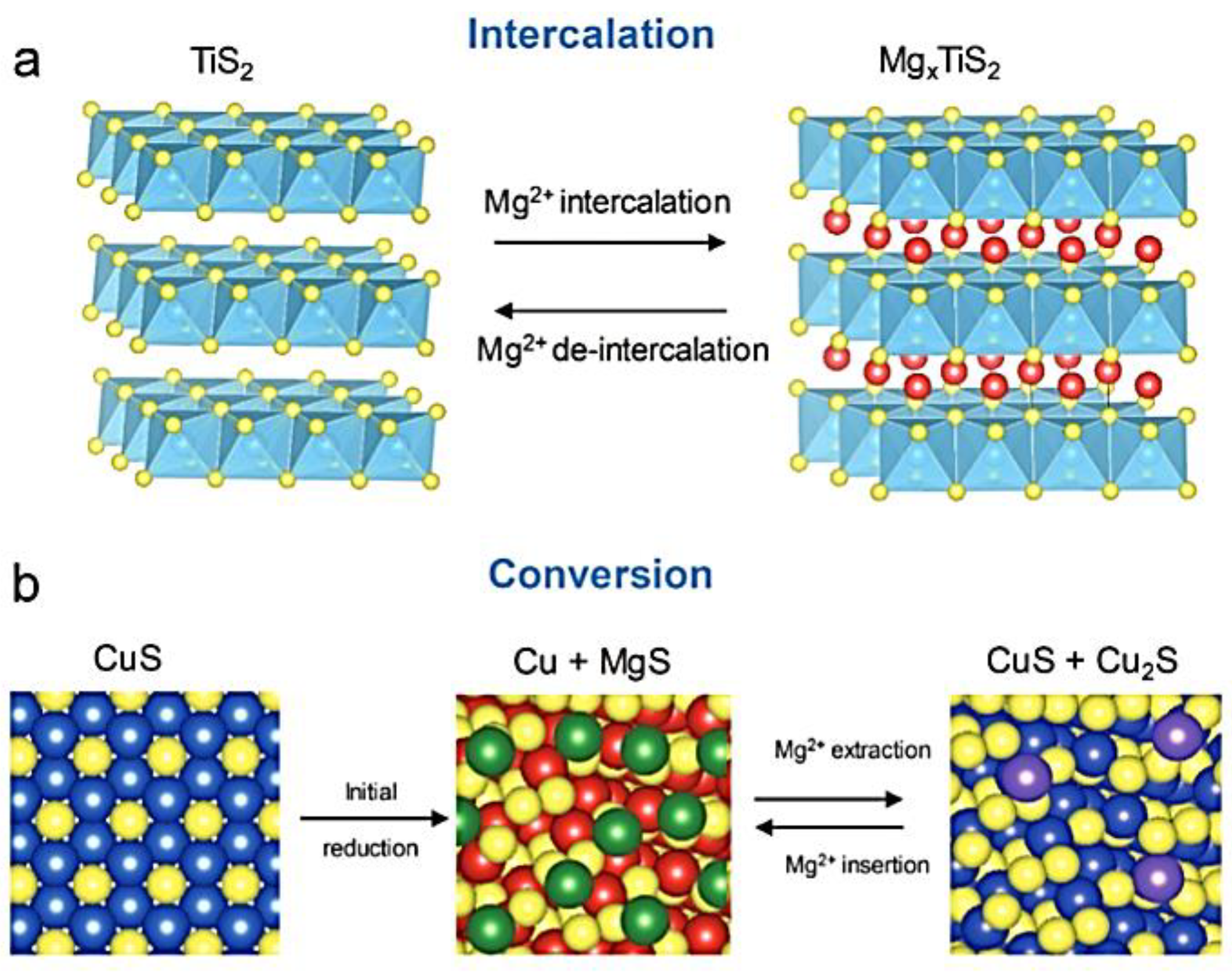

7.1. Metal Chalcogenide Cathodes: Types and Structures

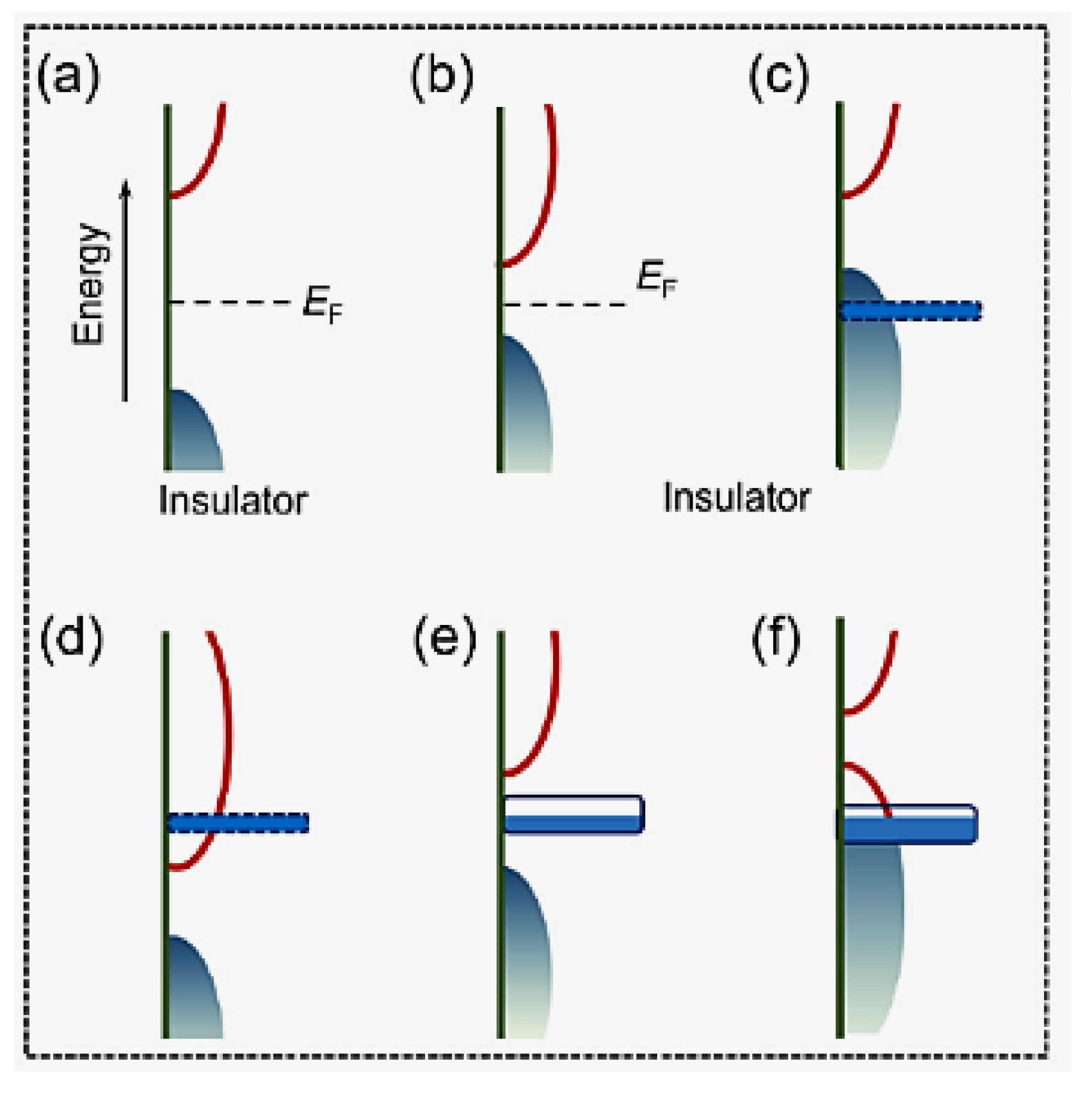

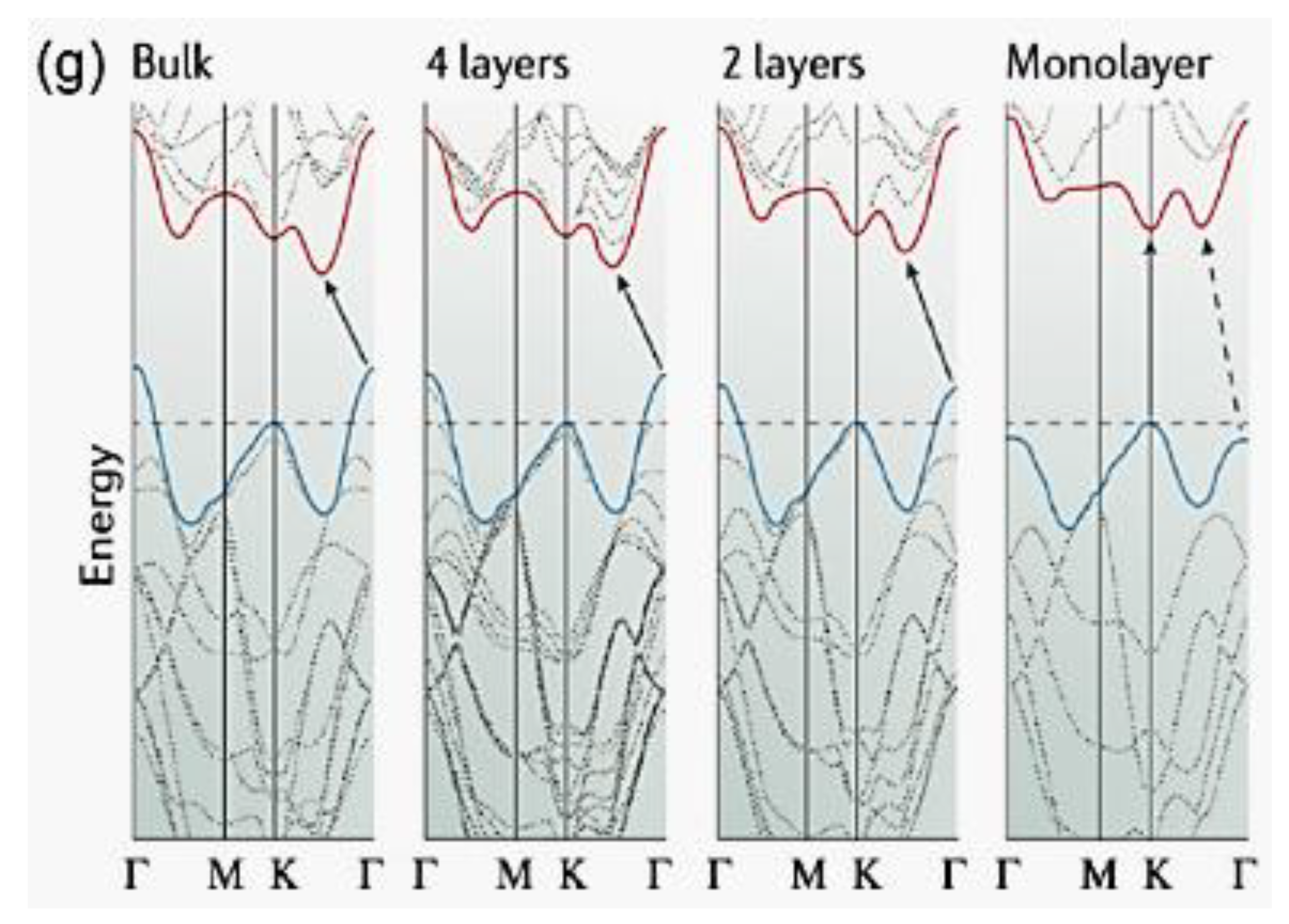

7.2. Transition Metal-Dichalcogenides (TMDCs): Composition and Properties

7.3. Advantages and Challenges of TMDs

8. Synthesis Methods

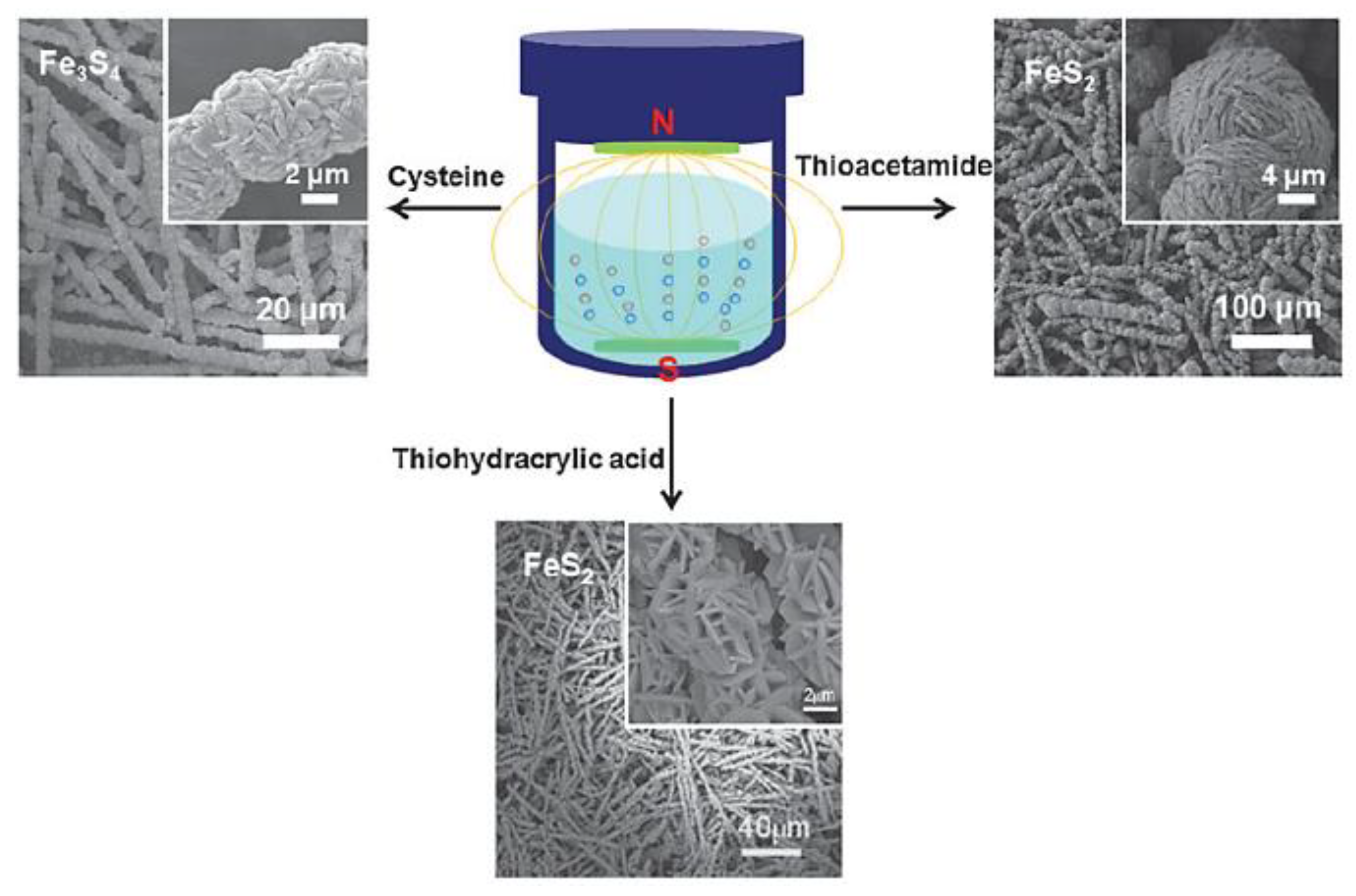

8.1. Hydrothermal Method

8.2. Solvothermal Method

8.3. Mixed solvent Method

8.4. Microwave Method

9. Morphology and Solvent Chemistry: Recipe for Improved Electrochemical and Battery Performance

10. Modification of MC Nanomaterials

10.1. Modification with Carbon Materials

10.2. Tuning of MC Nanostructured Materials with Noble Metals

10.3. Tunning MC Nanomaterials Using Metal Oxides

11. Application of Transition Metal-Chalcogenides in Mg-S Batteries

11.1. Copper (Cu)-Chalcogenide-Based Cathodes

11.2. Iron-Based Chalcogenide Cathodes

11.3. Cobalt-Based Chalcogenide Cathodes

11.4. Nickel-Based Chalcogenide Cathodes

12. Comparative Structure-Properties Performance Evaluation of TMCs in Mg-S Battery

12.1. Performance Metrics Analysis

13. Computational Perspectives

13.1. Materials/Device Simulation

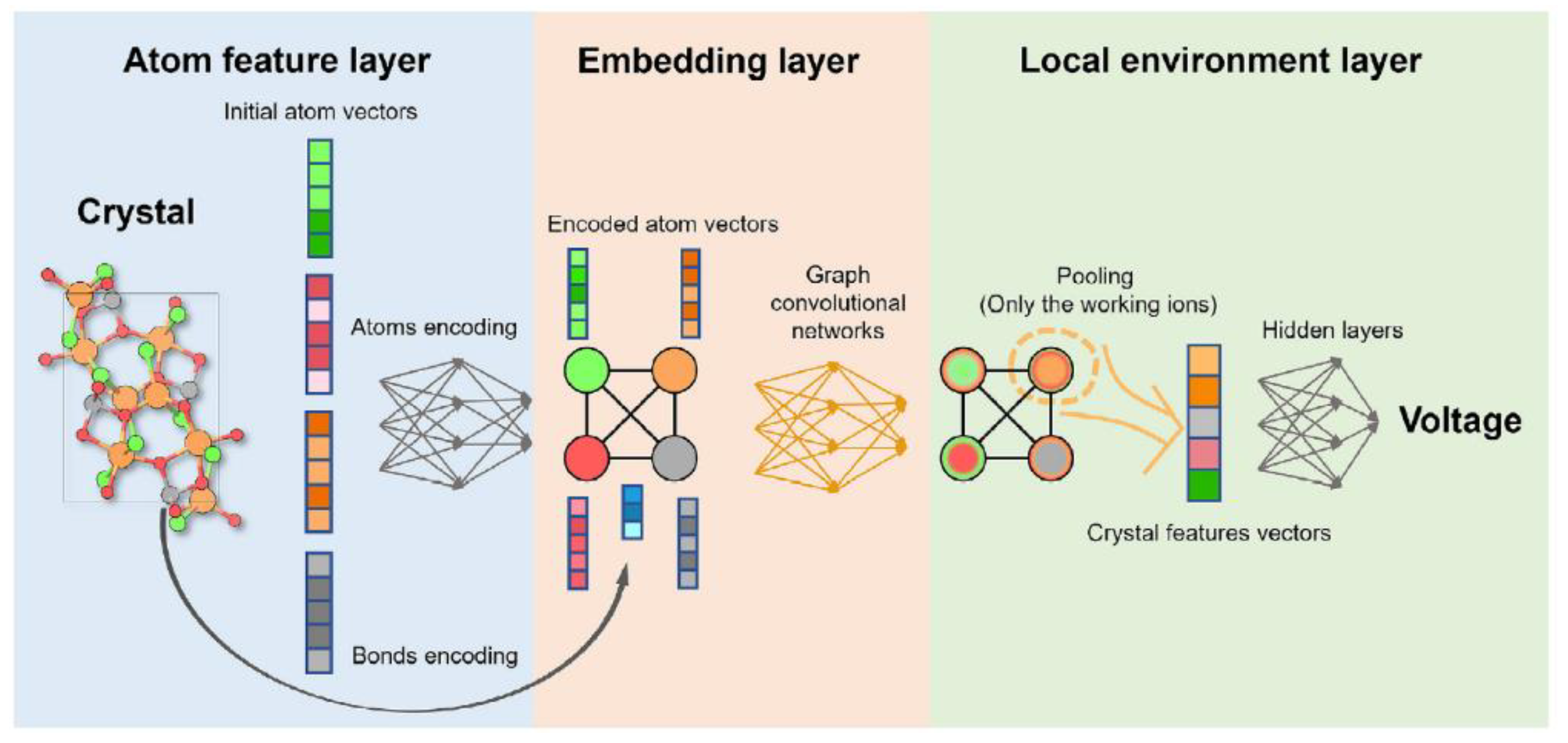

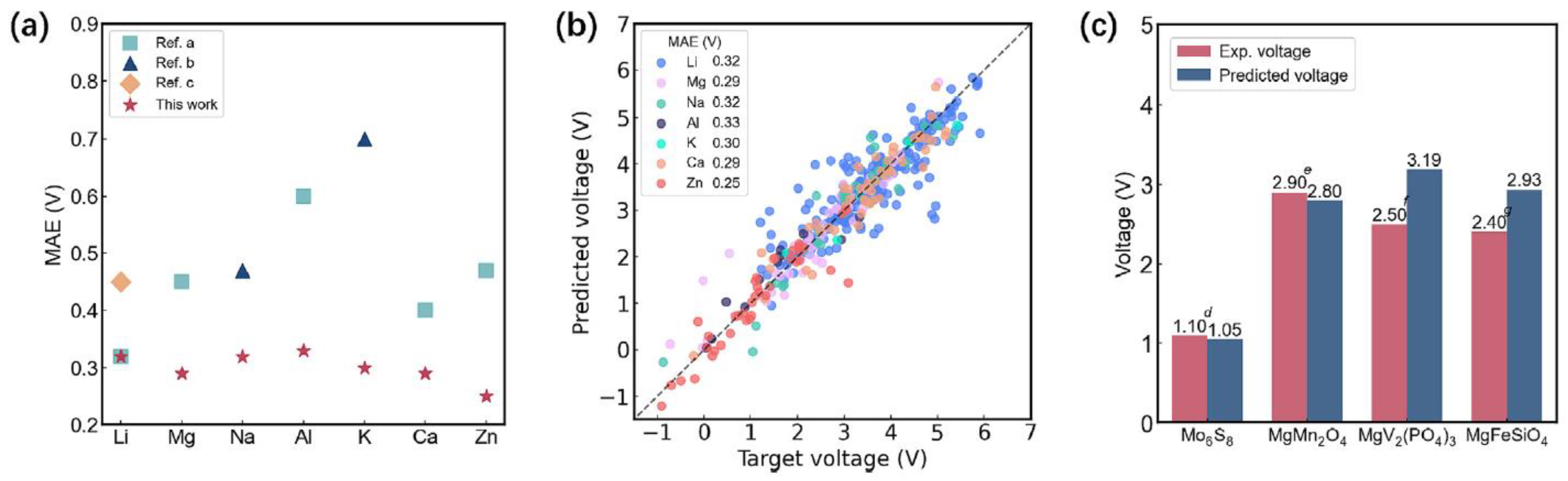

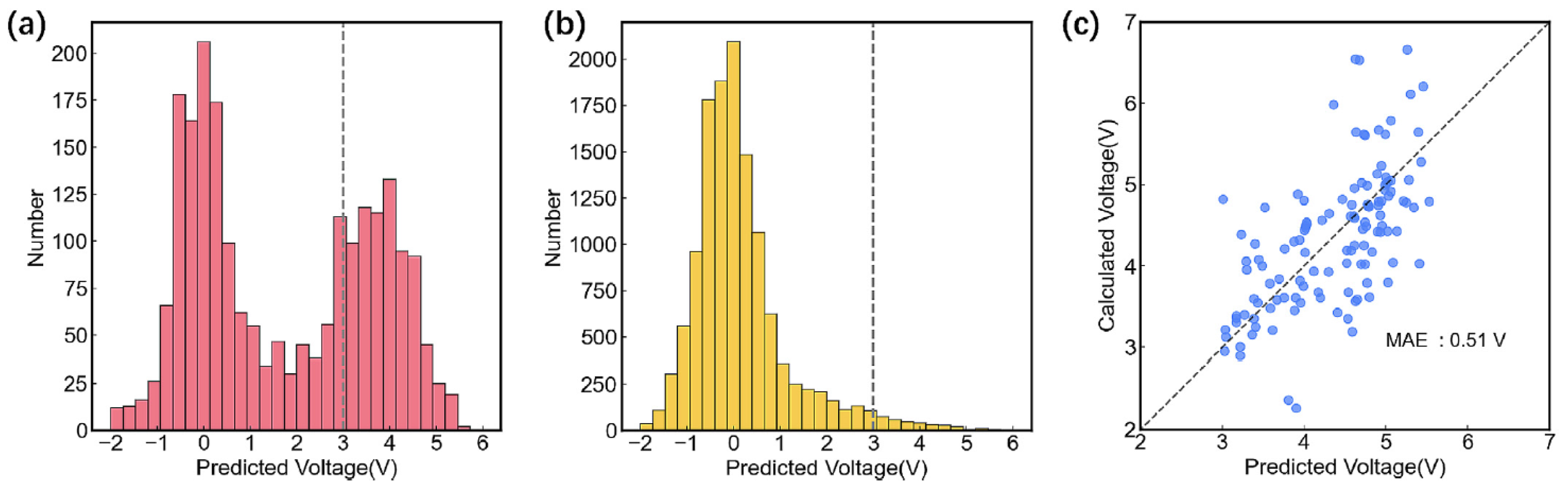

13.2. Machine Learning Approaches

13.3. Catalysis of Materials Discovery

13.4. AI-Driven Discovery Workflow for Electrode Materials of Mg Batteries

14. Challenges and Limitations

15. Future Directions and Opportunities

16. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrolidone |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| POM | Polyoxometalate |

| ACC | Activated carbon cloth |

| CNFs | Carbon nanofiber |

| RMB | Rechargeable magnesium battery |

| HSAB | Hard and soft acids and bases |

| TMDs | Transition metal dichalcogenides |

| TMSs | Transition metal-based sulfides |

| HDS | Hydrodesulfurisation |

| DOS | Density of states |

| TEPA | Tetraethylenepentamine |

| ECS | Electrochemical storage |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotube |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| MC | Metal chalcogenide |

| TAA | Thioacetamide |

| GPE | Gel polymer electrolyte |

| DETA | Diethylenetriamine |

| PEMFCs | Proton exchange membrane fuel cells |

| DMFCs | Direct methanol fuel cells |

| GNS | Graphene nanosheet |

| DMF | Dimethyl formamide |

References

- Bielecki, A., S. Ernst, W. Skrodzka, I. Wojnicki, The externalities of energy production in the context of development of clean energy generation, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27 (2020) 11506-11530.

- Mensah-Darkwa, K., D. Nframah Ampong, E. Agyekum, F.M. de Souza, R.K. Gupta, Recent advancements in chalcogenides for electrochemical energy storage applications, Energies, 15 (2022) 4052.

- Dai, M. ,R. Wang, Synthesis and applications of nanostructured hollow transition metal chalcogenides, Small, 17 (2021) 2006813.

- Galek, P., A. Mackowiak, P. Bujewska, K. Fic, Three-dimensional architectures in electrochemical capacitor applications–insights, opinions, and perspectives, Frontiers in Energy Research, 8 (2020) 139.

- Budde-Meiwes, H., J. Drillkens, B. Lunz, J. Muennix, S. Rothgang, J. Kowal, D.U. Sauer, A review of current automotive battery technology and future prospects, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 227 (2013) 761-776.

- Besenhard, J.O. ,M. Winter, Advances in battery technology: Rechargeable magnesium batteries and novel negative-electrode materials for lithium ion batteries, ChemPhysChem, 3 (2002) 155-159.

- Zu, C.-X. ,H. Li, Thermodynamic analysis on energy densities of batteries, Energy & Environmental Science, 4 (2011) 2614-2624.

- Li, Z., J. Häcker, M. Fichtner, Z. Zhao-Karger, Cathode materials and chemistries for magnesium batteries: challenges and opportunities, Advanced Energy Materials, 13 (2023) 2300682.

- Häcker, J., D.H. Nguyen, T. Rommel, Z. Zhao-Karger, N. Wagner, K.A. Friedrich, Operando UV/vis spectroscopy providing insights into the sulfur and polysulfide dissolution in magnesium–sulfur batteries, ACS Energy Letters, 7 (2021) 1-9.

- Ji, Y., X. Liu-Théato, Y. Xiu, S. Indris, C. Njel, J. Maibach, H. Ehrenberg, M. Fichtner, Z. Zhao-Karger, Polyoxometalate modified separator for performance enhancement of magnesium–sulfur batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, 31 (2021) 2100868.

- Gao, T., M. Noked, A.J. Pearse, E. Gillette, X. Fan, Y. Zhu, C. Luo, L. Suo, M.A. Schroeder, K. Xu, Enhancing the reversibility of Mg/S battery chemistry through Li+ mediation, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137 (2015) 12388-12393.

- Gao, T., S. Hou, K. Huynh, F. Wang, N. Eidson, X. Fan, F. Han, C. Luo, M. Mao, X. Li, Existence of solid electrolyte interphase in Mg batteries: Mg/S chemistry as an example, ACS applied materials & interfaces, 10 (2018) 14767-14776.

- Yu, X. ,A. Manthiram, Performance enhancement and mechanistic studies of magnesium–sulfur cells with an advanced cathode structure, ACS Energy Letters, 1 (2016) 431-437.

- Du, A., Z. Zhang, H. Qu, Z. Cui, L. Qiao, L. Wang, J. Chai, T. Lu, S. Dong, T. Dong, An efficient organic magnesium borate-based electrolyte with non-nucleophilic characteristics for magnesium–sulfur battery, Energy & environmental science, 10 (2017) 2616-2625.

- Yin, L.-C., J. Liang, G.-M. Zhou, F. Li, R. Saito, H.-M. Cheng, Understanding the interactions between lithium polysulfides and N-doped graphene using density functional theory calculations, Nano Energy, 25 (2016) 203-210.

- Yuan, H., L. Kong, T. Li, Q. Zhang, A review of transition metal chalcogenide/graphene nanocomposites for energy storage and conversion, Chinese Chemical Letters, 28 (2017) 2180-2194.

- Yan, Z., M. Ji, J. Xia, H. Zhu, Recent advanced materials for electrochemical and photoelectrochemical synthesis of ammonia from dinitrogen: one step closer to a sustainable energy future, Advanced Energy Materials, 10 (2020) 1902020.

- Sun, X., P. Bonnick, V. Duffort, M. Liu, Z. Rong, K.A. Persson, G. Ceder, L.F. Nazar, A high capacity thiospinel cathode for Mg batteries, Energy & Environmental Science, 9 (2016) 2273-2277.

- Ponnambalam, S. ,M. Ilampoornan, Integration of Renewable Energy Technologies and Hybrid Electric Vehicle Challenges in Power Systems, in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Distributed Renewable Energy Conversion: Control and Vibration Analysis. 2025, IGI Global Scientific Publishing. p. 157-186.

- Jin, L., Energy storage in multi-energy carrier communities: Li-ion batteries and hydrogen multi-physical details for integration into the planning stage, (2024).

- Yang, Q., Y. Su, X. Wang, K. Xiao, T. Chen, J. Fu, Emerging Strategies for Sustainable Holistic Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, (2025) e14524.

- Sheng, L., High-performance cathode design and safety evaluation of magnesium-sulfur batteries. 2022, UCL (University College London).

- Yao, W., K. Liao, T. Lai, H. Sul, A. Manthiram, Rechargeable metal-sulfur batteries: key materials to mechanisms, Chemical Reviews, 124 (2024) 4935-5118.

- Razaq, R., P. Li, Y. Dong, Y. Li, Y. Mao, S.H. Bo, Practical energy densities, cost, and technical challenges for magnesium-sulfur batteries, EcoMat, 2 (2020) e12056.

- Betz, J., G. Bieker, P. Meister, T. Placke, M. Winter, R. Schmuch, Theoretical versus practical energy: a plea for more transparency in the energy calculation of different rechargeable battery systems, Advanced energy materials, 9 (2019) 1803170.

- Salama, M., R. Attias, B. Hirsch, R. Yemini, Y. Gofer, M. Noked, D. Aurbach, On the feasibility of practical Mg–S batteries: practical limitations associated with metallic magnesium anodes, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 10 (2018) 36910-36917.

- Montenegro, C.T., J.F. Peters, M. Baumann, Z. Zhao-Karger, C. Wolter, M. Weil, Environmental assessment of a new generation battery: The magnesium-sulfur system, Journal of Energy Storage, 35 (2021) 102053.

- Zhao, J., Y.Y. Xiao, Q. Liu, J. Wu, Z.C. Jiang, H. Zeng, The rise of multivalent metal–sulfur batteries: advances, challenges, and opportunities, Advanced Functional Materials, 34 (2024) 2405358.

- Sheng, L., J. Feng, M. Gong, L. Zhang, J. Harding, Z. Hao, F.R. Wang, Advances and challenges in electrolyte development for magnesium–sulfur batteries: a comprehensive review, Molecules, 29 (2024) 1234.

- Zhou, X., T. Xu, M. Guo, H. Zhang, C. Li, W. Wang, M. Sun, G. Xia, X. Yu, Vertically Aligned Mesoporous Arrays Catalyzing Long-Chain Polysulfide Conversion to Unlock High-Energy Magnesium–Sulfur Batteries, ACS nano, (2025).

- Guan, Q., J. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Cheng, J. Dong, L. Jia, H. Lin, J. Wang, Prospect of Cascade Catalysis in Magnesium-Sulfur Batteries from Desolvation to Conversion Reactions, Advanced Science, (2025) e70008.

- Bai, X., X. Bai, T. Li, T. Li, U. Gulzar, U. Gulzar, R.P. Zaccaria, R.P. Zaccaria, C. Capiglia, Y.J. Bai, Comprehensive Understanding of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries: Current Status and Outlook, Advanced Battery Materials, (2019) 355-398.

- Flatscher, F., Lithium dendrites in solid-state batteries-Where they come from and how to mitigate them, (2023).

- Eng, A.Y.S., A. Ambrosi, Z. Sofer, P. Simek, M. Pumera, Electrochemistry of transition metal dichalcogenides: strong dependence on the metal-to-chalcogen composition and exfoliation method, Acs Nano, 8 (2014) 12185-12198.

- Tan, S.M., A. Ambrosi, Z. Sofer, Š. Huber, D. Sedmidubský, M. Pumera, Pristine basal-and edge-plane-oriented molybdenite MoS2 exhibiting highly anisotropic properties, Chemistry–A European Journal, 21 (2015) 7170-7178.

- Jayabal, S., J. Wu, J. Chen, D. Geng, X. Meng, Metallic 1T-MoS2 nanosheets and their composite materials: Preparation, properties and emerging applications, Materials today energy, 10 (2018) 264-279.

- Yuan, Z., H.-J. Peng, T.-Z. Hou, J.-Q. Huang, C.-M. Chen, D.-W. Wang, X.-B. Cheng, F. Wei, Q. Zhang, Powering lithium–sulfur battery performance by propelling polysulfide redox at sulfiphilic hosts, Nano letters, 16 (2016) 519-527.

- Shao, F., Z. Tian, P. Qin, K. Bu, W. Zhao, L. Xu, D. Wang, F. Huang, 2H-NbS2 film as a novel counter electrode for meso-structured perovskite solar cells, Scientific Reports, 8 (2018) 7033.

- Li, Y., Z. Zhou, S. Zhang, Z. Chen, MoS2 nanoribbons: high stability and unusual electronic and magnetic properties, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 130 (2008) 16739-16744.

- Chen, P., K. Xu, Y. Tong, X. Li, S. Tao, Z. Fang, W. Chu, X. Wu, C. Wu, Cobalt nitrides as a class of metallic electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction, Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 3 (2016) 236-242.

- Du, Y., A. Ji, L. Ma, Y. Wang, Z. Cao, Electrical conductivity and photoreflectance of nanocrystalline copper nitride thin films deposited at low temperature, Journal of crystal growth, 280 (2005) 490-494.

- Kaya, A.I., Determination of thermal conductivity and physical properties of Fe2O3 doped rigid polyurethane materials, Science of Advanced Materials, 12 (2020) 1790-1793.

- Stozhko, N.Y., E.I. Khamzina, M.A. Bukharinova, A.V. Tarasov, An electrochemical sensor based on carbon paper modified with graphite powder for sensitive determination of sunset yellow and tartrazine in drinks, Sensors, 22 (2022) 4092.

- Zhou, Z., K. Kato, T. Komaki, M. Yoshino, H. Yukawa, M. Morinaga, K. Morita, Effects of dopants and hydrogen on the electrical conductivity of ZnO, Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 24 (2004) 139-146.

- Muthu, P., S. Rajagopal, D. Saju, V. Kesavan, A. Dellus, L. Sadhasivam, N. Chandrasekaran, Review of transition metal chalcogenides and halides as electrode materials for thermal batteries and secondary energy storage systems, ACS omega, 9 (2024) 7357-7374.

- Reddy, B., M. Premasudha, N. Reddy, H.-J. Ahn, J.-H. Ahn, K.-K. Cho, Hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2/rGO composite as sulfur hosts for room temperature sodium-sulfur batteries and its electrochemical properties, Journal of Energy Storage, 39 (2021) 102660.

- Zhu, F., H. Zhang, Z. Lu, D. Kang, L. Han, Controlled defective engineering of MoS2 nanosheets for rechargeable Mg batteries, Journal of Energy Storage, 42 (2021) 103046.

- Liu, W., S. Yang, D. Fan, Y. Wu, J. Zhang, Y. Lu, L. Fu, PEG–PVP-assisted hydrothermal synthesis and electrochemical performance of N-doped MoS2/C composites as anode material for lithium-ion batteries, ACS omega, 9 (2024) 9792-9802.

- Cui, C., H. Pan, L. Wang, M. Baiyin, Transition Metal Germanium Chalcogenide Materials: Solvothermal Syntheses, Flexible Crystal, Structures, and Photoelectric Response Property, Crystal Growth & Design, 24 (2024) 1227-1234.

- Tian, X.-Y., C.-X. Du, G. ZhaoRi, M. SheLe, Y. Bao, M. Baiyin, The solvothermal synthesis and characterization of quaternary arsenic chalcogenides CsTMAsQ 3 (TM= Hg, Cd; Q= S, Se) using Cs+ as a structure directing agent: from 1D anionic chains to 2D anionic layers, RSC advances, 10 (2020) 34903-34909.

- Liu, Z., L. Zhang, R. Wang, S. Poyraz, J. Cook, M.J. Bozack, S. Das, X. Zhang, L. Hu, Ultrafast microwave nano-manufacturing of fullerene-like metal chalcogenides, Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 22503.

- Aslam, M.K., I.D. Seymour, N. Katyal, S. Li, T. Yang, S.-j. Bao, G. Henkelman, M. Xu, Metal chalcogenide hollow polar bipyramid prisms as efficient sulfur hosts for Na-S batteries, Nature communications, 11 (2020) 5242.

- Wang, J., T. Ghosh, Z. Ju, M.-F. Ng, G. Wu, G. Yang, X. Zhang, L. Zhang, A.D. Handoko, S. Kumar, Heterojunction structure of cobalt sulfide cathodes for high-performance magnesium-ion batteries, Matter, 7 (2024) 1833-1847.

- Szkoda, M., A. Ilnicka, K. Trzciński, Z. Zarach, D. Roda, A.P. Nowak, Synthesis and characterization of MoS2-carbon based materials for enhanced energy storage applications, Scientific Reports, 14 (2024) 26128.

- Li, P., J.Y. Jeong, B. Jin, K. Zhang, J.H. Park, Vertically oriented MoS2 with spatially controlled geometry on nitrogenous graphene sheets for high-performance sodium-ion batteries, Advanced Energy Materials, 8 (2018) 1703300.

- Cui, C., Z. Wei, J. Xu, Y. Zhang, S. Liu, H. Liu, M. Mao, S. Wang, J. Ma, S. Dou, Three-dimensional carbon frameworks enabling MoS2 as anode for dual ion batteries with superior sodium storage properties, Energy Storage Materials, 15 (2018) 22-30.

- Zhao, Z.-H., X.-D. Hu, H. Wang, M.-Y. Ye, Z.-Y. Sang, H.-M. Ji, X.-L. Li, Y. Dai, Superelastic 3D few-layer MoS2/carbon framework heterogeneous electrodes for highly reversible sodium-ion batteries, Nano Energy, 48 (2018) 526-535.

- Liu, Y., X. He, D. Hanlon, A. Harvey, J.N. Coleman, Y. Li, Liquid phase exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets percolated with carbon nanotubes for high volumetric/areal capacity sodium-ion batteries, Acs Nano, 10 (2016) 8821-8828.

- Cai, Y., H. Yang, J. Zhou, Z. Luo, G. Fang, S. Liu, A. Pan, S. Liang, Nitrogen doped hollow MoS2/C nanospheres as anode for long-life sodium-ion batteries, Chemical Engineering Journal, 327 (2017) 522-529.

- Sun, D., D. Ye, P. Liu, Y. Tang, J. Guo, L. Wang, H. Wang, MoS2/Graphene nanosheets from commercial bulky MoS2 and graphite as anode materials for high rate sodium-ion batteries, Advanced Energy Materials, 8 (2018) 1702383.

- Li, G., D. Luo, X. Wang, M.H. Seo, S. Hemmati, A. Yu, Z. Chen, Enhanced reversible sodium-ion intercalation by synergistic coupling of few-layered MoS2 and S-doped graphene, Advanced Functional Materials, 27 (2017) 1702562.

- Kong, D., C. Cheng, Y. Wang, Z. Huang, B. Liu, Y. Von Lim, Q. Ge, H.Y. Yang, Fe 3 O 4 quantum dot decorated MoS 2 nanosheet arrays on graphite paper as free-standing sodium-ion battery anodes, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 5 (2017) 9122-9131.

- Geng, X., Y. Jiao, Y. Han, A. Mukhopadhyay, L. Yang, H. Zhu, Freestanding metallic 1T MoS2 with dual ion diffusion paths as high rate anode for sodium-ion batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, 27 (2017) 1702998.

- Li, X., Y. Yang, J. Liu, L. Ouyang, J. Liu, R. Hu, L. Yang, M. Zhu, MoS2/cotton-derived carbon fibers with enhanced cyclic performance for sodium-ion batteries, Applied Surface Science, 413 (2017) 169-174.

- Wang, L., G. Yang, J. Wang, S. Peng, W. Yan, S. Ramakrishna, Controllable design of MoS2 nanosheets grown on nitrogen-doped branched TiO2/C nanofibers: toward enhanced sodium storage performance induced by pseudocapacitance behavior, Small, 16 (2020) 1904589.

- Pang, Y., S. Zhang, L. Liu, J. Liang, Z. Sun, Y. Wang, C. Xiao, D. Ding, S. Ding, Few-layer MoS 2 anchored at nitrogen-doped carbon ribbons for sodium-ion battery anodes with high rate performance, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 5 (2017) 17963-17972.

- Zhang, Y., S. Yu, H. Wang, Z. Zhu, Q. Liu, E. Xu, D. Li, G. Tong, Y. Jiang, A novel carbon-decorated hollow flower-like MoS2 nanostructure wrapped with RGO for enhanced sodium-ion storage, Chemical Engineering Journal, 343 (2018) 180-188.

- Ye, H., L. Wang, S. Deng, X. Zeng, K. Nie, P.N. Duchesne, B. Wang, S. Liu, J. Zhou, F. Zhao, Amorphous MoS3 infiltrated with carbon nanotubes as an advanced anode material of sodium-ion batteries with large gravimetric, areal, and volumetric capacities, Advanced Energy Materials, 7 (2017) 1601602.

- Niu, F., J. Yang, N. Wang, D. Zhang, W. Fan, J. Yang, Y. Qian, MoSe2-covered N, P-doped carbon nanosheets as a long-life and high-rate anode material for sodium-ion batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, 27 (2017) 1700522.

- Zhang, Z., X. Yang, Y. Fu, K. Du, Ultrathin molybdenum diselenide nanosheets anchored on multi-walled carbon nanotubes as anode composites for high performance sodium-ion batteries, Journal of Power Sources, 296 (2015) 2-9.

- Wang, S., F. Gong, S. Yang, J. Liao, M. Wu, Z. Xu, C. Chen, X. Yang, F. Zhao, B. Wang, Graphene oxide-template controlled cuboid-shaped high-capacity VS4 nanoparticles as anode for sodium-ion batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, 28 (2018) 1801806.

- Sun, R., Q. Wei, Q. Li, W. Luo, Q. An, J. Sheng, D. Wang, W. Chen, L. Mai, Vanadium sulfide on reduced graphene oxide layer as a promising anode for sodium ion battery, ACS applied materials & interfaces, 7 (2015) 20902-20908.

- Zhang, Y., N. Wang, P. Xue, Y. Liu, B. Tang, Z. Bai, S. Dou, Co9S8@ carbon nanospheres as high-performance anodes for sodium ion battery, Chemical Engineering Journal, 343 (2018) 512-519.

- Pan, Y., X. Cheng, Y. Huang, L. Gong, H. Zhang, CoS2 nanoparticles wrapping on flexible freestanding multichannel carbon nanofibers with high performance for Na-ion batteries, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 9 (2017) 35820-35828.

- Freitas, F.S., A.S. Gonçalves, A. De Morais, J.E. Benedetti, A.F. Nogueira, Graphene-like MoS2 as a low-cost counter electrode material for dye-sensitized solar cells, J. NanoGe J. Energy Sustain, 1 (2012) 11002-11003.

- Kim, K., Unveiling the Unique Phase Transformation Behavior and Sodiation Kinetics of 1D van der Waals Sb2S3 Anodes for Sodium Ion Batteries Shanshan Yao, Jiang Cui, Ziheng Lu, Zheng-Long Xu, Lei Qin, Jiaqiang Huang, Zoya Sadighi, Francesco Ciucci,* and Jang,.

- Xiong, X., G. Wang, Y. Lin, Y. Wang, X. Ou, F. Zheng, C. Yang, J.-H. Wang, M. Liu, Enhancing sodium ion battery performance by strongly binding nanostructured Sb2S3 on sulfur-doped graphene sheets, ACS nano, 10 (2016) 10953-10959.

- Dong, S., C. Li, X. Ge, Z. Li, X. Miao, L. Yin, ZnS-Sb2S3@ C core-double shell polyhedron structure derived from metal–organic framework as anodes for high performance sodium ion batteries, Acs Nano, 11 (2017) 6474-6482.

- Ge, P., X. Cao, H. Hou, S. Li, X. Ji, Rodlike Sb2Se3 wrapped with carbon: the exploring of electrochemical properties in sodium-ion batteries, ACS applied materials & interfaces, 9 (2017) 34979-34989.

- Luo, W., A. Calas, C. Tang, F. Li, L. Zhou, L. Mai, Ultralong Sb2Se3 nanowire-based free-standing membrane anode for lithium/sodium ion batteries, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 8 (2016) 35219-35226.

- Xiong, X., C. Yang, G. Wang, Y. Lin, X. Ou, J.-H. Wang, B. Zhao, M. Liu, Z. Lin, K. Huang, SnS nanoparticles electrostatically anchored on three-dimensional N-doped graphene as an active and durable anode for sodium-ion batteries, Energy & Environmental Science, 10 (2017) 1757-1763.

- Lin, Y., Z. Qiu, D. Li, S. Ullah, Y. Hai, H. Xin, W. Liao, B. Yang, H. Fan, J. Xu, NiS2@ CoS2 nanocrystals encapsulated in N-doped carbon nanocubes for high performance lithium/sodium ion batteries, Energy Storage Materials, 11 (2018) 67-74.

- Ma, L., S. Wei, H.L. Zhuang, K.E. Hendrickson, R.G. Hennig, L.A. Archer, Hybrid cathode architectures for lithium batteries based on TiS 2 and sulfur, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 3 (2015) 19857-19866.

- Chung, S.-H., L. Luo, A. Manthiram, TiS2–polysulfide hybrid cathode with high sulfur loading and low electrolyte consumption for lithium–sulfur batteries, ACS Energy Letters, 3 (2018) 568-573.

- Tang, W., Electrical, electronic and optical properties of MoS2 & WS2, (2017).

- Chen, L., R. Wang, N. Li, Y. Bai, Y. Zhou, J. Wang, Optimized Adsorption–Catalytic Conversion for Lithium Polysulfides by Constructing Bimetallic Compounds for Lithium–Sulfur Batteries, Materials, 17 (2024) 3075.

- Wang, M., L. Fan, X. Sun, B. Guan, B. Jiang, X. Wu, D. Tian, K. Sun, Y. Qiu, X. Yin, Nitrogen-doped CoSe2 as a bifunctional catalyst for high areal capacity and lean electrolyte of Li–S battery, ACS Energy Letters, 5 (2020) 3041-3050.

- Fan, X., M. Tebyetekerwa, Y. Wu, R.R. Gaddam, X.S. Zhao, Magnesium/lithium hybrid batteries based on SnS2-MoS2 with reversible conversion reactions, Energy Material Advances, (2022).

- Han, X., J. Yang, Y.-W. Zhang, Z.G. Yu, Molecular engineering on a MoS 2 interlayer for high-capacity and rapid-charging aqueous ion batteries, Nanoscale Advances, 5 (2023) 2639-2645.

- Alshammari, G.M., M.A. Mohammed, A. Al Tamim, M.A. Yahya, A.E.A. Yagoub, Changes in nutrients, heavy metals, residual pesticides, bioactive compounds, and anti-oxidant activity following germination and fermentation of Sudanese and Yemeni sorghums, International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 60 (2025) vvaf069.

- Pang, B., L. Xiang, K. Wang, S. Zeng, J. Guo, N. Li, Interlayer-expanded 1T-phase MoS2 as a cathode material for enhanced capacitive deionization, Desalination, 593 (2025) 118211.

- Fan, C., R. Yang, Y. Yang, Y. Yang, Y. Huang, Y. Yan, L. Zhong, Y. Xu, Cubic CoSe2@ carbon as polysulfides adsorption-catalytic mediator for fast redox kinetics and advanced stability lithium-sulfur batteries, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 660 (2024) 246-256.

- Liu, X., Y. Zheng, M. Zhang, S. Qi, M. Tan, R. Zhao, M. Zhao, Surface-Dependent Electrocatalytic Activity of CoSe2 for Lithium Sulfur Battery, Advanced Materials Interfaces, 10 (2023) 2202205.

- Liu, G., Q. Zeng, Z. Fan, S. Tian, X. Li, X. Lv, W. Zhang, K. Tao, E. Xie, Z. Zhang, Boosting sulfur catalytic kinetics by defect engineering of vanadium disulfide for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries, Chemical Engineering Journal, 448 (2022) 137683.

- Tagliaferri, S., G. Nagaraju, M. Sokolikova, R. Quintin-Baxendale, C. Mattevi, 3D printing of layered vanadium disulfide for water-in-salt electrolyte zinc-ion batteries, Nanoscale Horizons, 9 (2024) 742-751.

- Roy, A., S. Dey, G. Singh, MoS2, WS2, and MoWS2 flakes as reversible host materials for sodium-ion and potassium-ion batteries, ACS omega, 9 (2024) 24933-24947.

- Bissett, M.A., S.D. Worrall, I.A. Kinloch, R.A. Dryfe, Comparison of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides for electrochemical supercapacitors, Electrochimica Acta, 201 (2016) 30-37.

- Al-Tahan, M.A., Y. Dong, A.E. Shrshr, X. Liu, R. Zhang, H. Guan, X. Kang, R. Wei, J. Zhang, Enormous-sulfur-content cathode and excellent electrochemical performance of Li-S battery accouched by surface engineering of Ni-doped WS2@ rGO nanohybrid as a modified separator, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 609 (2022) 235-248.

- Jing, P., S. Stevenson, H. Lu, P. Ren, I. Abrahams, D.H. Gregory, Pillared Vanadium Molybdenum Disulfide Nanosheets: Toward High-Performance Cathodes for Magnesium-Ion Batteries, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 15 (2023) 51036-51049.

- Zhang, J., X. Lu, J. Zhang, H. Li, B. Huang, B. Chen, J. Zhou, S. Jing, Metal-ions intercalation mechanism in layered anode from first-principles calculation, Frontiers in Chemistry, 9 (2021) 677620.

- Wang, Q., X. Wei, M. Li, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, Y. Tian, Z. Li, S. Wei, L. Duan, TiS2/VS2 heterostructures: A DFT study unveiling their potential as high-performance anodes for Li/Na/K-ion batteries, Materials Today Communications, 41 (2024) 111037.

- Sotoudeh, M., M. Dillenz, A. Groß, Mechanism of magnesium transport in spinel chalcogenides, Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research, 2 (2021) 2100113.

- Gong, K., K. Yang, C.E. White, Density functional modeling of the binding energies between aluminosilicate oligomers and different metal cations, Frontiers in Materials, 10 (2023) 1089216.

- Mizanuzzaman, M., M.A. Chowdhury, R. Ahmed, M.A. Mahmud, M.A. Kowser, DFT based investigation of Se doped MgMo6S8-ySey as promising cathode materials for Mg-ion battery application, Scientific Reports, 15 (2025) 30817.

- Imran, S., G.N. Shao, H. Kim, https://www. sciencedirect. com/science/article/abs/pii/S092633731500346X, (2016).

- Paul, A., M. Pandey, P. Johari, Computational study of adsorption of magnesium polysulfides on VS4 magnesium sulfur batteries, Materials Today: Proceedings, 76 (2023) 352-358.

- Kheralla, A. ,N. Chetty, A review of experimental and computational attempts to remedy stability issues of perovskite solar cells, Heliyon, 7 (2021).

- He, Q., B. Yu, Z. Li, Y. Zhao, Density functional theory for battery materials, Energy & Environmental Materials, 2 (2019) 264-279.

- Wu, J., Z. Yu, Y. Yao, L. Wang, Y. Wu, X. Cheng, Z. Ali, Y. Yu, Bifunctional catalyst for liquid–solid redox conversion in room-temperature sodium–sulfur batteries, Small Structures, 3 (2022) 2200020.

- Song, H., Y. Li, X.L. Li, Y. Li, D.s. Li, D. Wang, S. Huang, H.Y. Yang, Recent progress in heterostructured materials for room-temperature sodium-sulfur batteries, Interdisciplinary Materials, 3 (2024) 565-594.

- Salvatore, K.L., J. Fang, C.R. Tang, E.S. Takeuchi, A.C. Marschilok, K.J. Takeuchi, S.S. Wong, Microwave-assisted fabrication of high energy density binary metal sulfides for enhanced performance in battery applications, Nanomaterials, 13 (2023) 1599.

- Shen, M., S. Xu, X. Wang, Y. Zhang, Y. Feng, F. Xing, Y. Yang, Q. Gao, Modification and Functionalization of Separators for High Performance Lithium–Sulfur Batteries, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25 (2024) 11446.

- Wang, L., S. Riedel, J. Drews, Z. Zhao-Karger, Recent developments and future prospects of magnesium–sulfur batteries, Frontiers in Batteries and Electrochemistry, 3 (2024) 1358199.

- Du, S., Y. Yu, X. Liu, D. Lu, X. Yue, T. Liu, Y. Yin, Z. Wu, Catalytic engineering for polysulfide conversion in high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries, Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 186 (2024) 110-131.

- Li, T., Z. Wang, J. Hu, H. Song, Y. Shi, Y. Jiang, D. Zhang, S. Huang, Manipulating polysulfide catalytic conversion through edge site construction, hybrid phase engineering, and Se anion substitution for kinetics-enhanced lithium-sulfur battery, Chemical Engineering Journal, 471 (2023) 144736.

- Puntambekar, U., S. Veliah, R. Pandey, Point-defects in magnesium sulfide, Journal of materials research, 9 (1994) 132-134.

- Chen, T., G. Sai Gautam, P. Canepa, Ionic transport in potential coating materials for Mg batteries, Chemistry of Materials, 31 (2019) 8087-8099.

- Lu, J., T. Wu, K. Amine, State-of-the-art characterization techniques for advanced lithium-ion batteries, Nature Energy, 2 (2017) 1-13.

- Islam, M.S. ,C.A. Fisher, Lithium and sodium battery cathode materials: computational insights into voltage, diffusion and nanostructural properties, Chemical Society Reviews, 43 (2014) 185-204.

- Oganov, A.R., C.J. Pickard, Q. Zhu, R.J. Needs, Structure prediction drives materials discovery, Nature Reviews Materials, 4 (2019) 331-348.

- Vincent, S., J.H. Chang, P. Canepa, J.M. García-Lastra, Mechanisms of electronic and ionic transport during Mg intercalation in Mg–S cathode materials and their decomposition products, Chemistry of Materials, 35 (2023) 3503-3512.

- Rajput, N.N., X. Qu, N. Sa, A.K. Burrell, K.A. Persson, The coupling between stability and ion pair formation in magnesium electrolytes from first-principles quantum mechanics and classical molecular dynamics, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137 (2015) 3411-3420.

- Zhang, Z., Z. Cui, L. Qiao, J. Guan, H. Xu, X. Wang, P. Hu, H. Du, S. Li, X. Zhou, Novel design concepts of efficient Mg-Ion electrolytes toward high-performance magnesium–selenium and magnesium–sulfur batteries, Advanced Energy Materials, 7 (2017) 1602055.

- DeWitt, S., N. Hahn, K. Zavadil, K. Thornton, Computational examination of orientation-dependent morphological evolution during the electrodeposition and electrodissolution of magnesium, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 163 (2015) A513.

- Chadwick, A.F., G. Vardar, S. DeWitt, A.E. Sleightholme, C.W. Monroe, D.J. Siegel, K. Thornton, Computational model of magnesium deposition and dissolution for property determination via cyclic voltammetry, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 163 (2016) A1813.

- Latz, A. ,J. Zausch, Thermodynamic consistent transport theory of Li-ion batteries, Journal of Power Sources, 196 (2011) 3296-3302.

- Drews, J., P. Jankowski, J. Häcker, Z. Li, T. Danner, J.M. García Lastra, T. Vegge, N. Wagner, K.A. Friedrich, Z. Zhao-Karger, Modeling of Electron-Transfer Kinetics in Magnesium Electrolytes: Influence of the Solvent on the Battery Performance, ChemSusChem, 14 (2021) 4820-4835.

- Krauskopf, T., F.H. Richter, W.G. Zeier, J.r. Janek, Physicochemical concepts of the lithium metal anode in solid-state batteries, Chemical reviews, 120 (2020) 7745-7794.

- Richter, R., J. Häcker, Z. Zhao-Karger, T. Danner, N. Wagner, M. Fichtner, K.A. Friedrich, A. Latz, Degradation effects in metal–sulfur batteries, ACS Applied Energy Materials, 4 (2021) 2365-2376.

- Zhao, Q., R. Wang, Y. Zhang, G. Huang, B. Jiang, C. Xu, F. Pan, The design of Co3S4@ MXene heterostructure as sulfur host to promote the electrochemical kinetics for reversible magnesium-sulfur batteries, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 9 (2021) 78-89.

- Yang, Y., W. Fu, D. Zhang, W. Ren, S. Zhang, Y. Yan, Y. Zhang, S.-J. Lee, J.-S. Lee, Z.-F. Ma, Toward high-performance Mg-S batteries via a copper phosphide modified separator, ACS nano, 17 (2022) 1255-1267.

- Ladha, D.G., A review on density functional theory–based study on two-dimensional materials used in batteries, Materials Today Chemistry, 11 (2019) 94-111.

- Miao, W., H. Peng, S. Cui, J. Zeng, G. Ma, L. Zhu, Z. Lei, Y. Xu, Fine nanostructure design of metal chalcogenide conversion-based cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries, Iscience, 27 (2024).

- Liu, J., T. Shen, J.-C. Ren, S. Li, W. Liu, Role of van der Waals interactions on the binding energies of 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides, Applied Surface Science, 608 (2023) 155163.

- Giuffredi, G., T. Asset, Y. Liu, P. Atanassov, F. Di Fonzo, Transition metal chalcogenides as a versatile and tunable platform for catalytic CO2 and N2 electroreduction, ACS Materials Au, 1 (2021) 6-36.

- Liu, Y., B.V. Merinov, W.A. Goddard III, Origin of low sodium capacity in graphite and generally weak substrate binding of Na and Mg among alkali and alkaline earth metals, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113 (2016) 3735-3739.

- Gu, G.H., J. Noh, I. Kim, Y. Jung, Machine learning for renewable energy materials, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 7 (2019) 17096-17117.

- Agrawal, A. ,A. Choudhary, Perspective: Materials informatics and big data: Realization of the “fourth paradigm” of science in materials science, Apl Materials, 4 (2016).

- Gabardi, S., E. Baldi, E. Bosoni, D. Campi, S. Caravati, G. Sosso, J. Behler, M. Bernasconi, Atomistic simulations of the crystallization and aging of GeTe nanowires, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 121 (2017) 23827-23838.

- Herring, P., C.B. Gopal, M. Aykol, J.H. Montoya, A. Anapolsky, P.M. Attia, W. Gent, J.S. Hummelshøj, L. Hung, H.-K. Kwon, BEEP: A python library for battery evaluation and early prediction, SoftwareX, 11 (2020) 100506.

- Sulzer, V., S.G. Marquis, R. Timms, M. Robinson, S.J. Chapman, Python battery mathematical modelling (PyBaMM), Journal of Open Research Software, 9 (2021).

- Liu, X., X.-Q. Zhang, X. Chen, G.-L. Zhu, C. Yan, J.-Q. Huang, H.-J. Peng, A generalizable, data-driven online approach to forecast capacity degradation trajectory of lithium batteries, Journal of Energy Chemistry, 68 (2022) 548-555.

- Lombardo, T., M. Duquesnoy, H. El-Bouysidy, F. Årén, A. Gallo-Bueno, P.B. Jørgensen, A. Bhowmik, A. Demortiere, E. Ayerbe, F. Alcaide, Artificial intelligence applied to battery research: hype or reality?, Chemical reviews, 122 (2021) 10899-10969.

- Liu, X., H.J. Peng, B.Q. Li, X. Chen, Z. Li, J.Q. Huang, Q. Zhang, Untangling degradation chemistries of lithium-sulfur batteries through interpretable hybrid machine learning, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 61 (2022) e202214037.

- Orikasa, Y., T. Masese, Y. Koyama, T. Mori, M. Hattori, K. Yamamoto, T. Okado, Z.-D. Huang, T. Minato, C. Tassel, High energy density rechargeable magnesium battery using earth-abundant and non-toxic elements, Scientific reports, 4 (2014) 5622.

- Chen, W., Z. Lin, X. Zhang, H. Zhou, Y. Zhang, AI-driven accelerated discovery of intercalation-type cathode materials for magnesium batteries, Journal of Energy Chemistry, 108 (2025) 40-46.

- Jain, A., S.P. Ong, G. Hautier, W. Chen, W.D. Richards, S. Dacek, S. Cholia, D. Gunter, D. Skinner, G. Ceder, Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation, APL materials, 1 (2013).

- Batzner, S., A. Musaelian, L. Sun, M. Geiger, J.P. Mailoa, M. Kornbluth, N. Molinari, T.E. Smidt, B. Kozinsky, E (3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials, Nature communications, 13 (2022) 2453.

| Objects | Metal compound | Conductivity (S cm−1) | Ref. |

| Sulfides | WS2 | 3.7×105 | [34] |

| MoS2 (1T edge) | 2.0× 104 | [35] | |

| MoS2 (2H) | 2.0×10−3 | [36] | |

| CoS2 | 6.7×103 | [37] | |

| Nitride | NbS2 | 8.7×103 | [38] |

| MoN | 2.3×10−1 | [39] | |

| Co2N | 2.1 ×102 | [40] | |

| Cu3N | 2.5×102 | [41] | |

| Oxides | Fe2O3 | 2.0×10−1 | [42] |

| TiO2 (rutile) | 1.1×10−1 | [43] | |

| ZnO | 5.0×10−2 | [44] |

| Cathode material | Synthesis techniques | Voltage range (V) | Cycling performance (mAhg-1/No. of cycles | Maximum rate capacity (mAhg-1) | Current density (A/g/mAg-1 | Ref |

| MoS2/N-doped carbon Nanowall/carbon cloth |

Solvothermal | 0.01-3 | 619.2/100 | 235 | 2 | [55] |

| MoS2/carbon fiber @MoS2@C |

Electrospinning | 0.01-2.5 | 332.6/1000 | 233.6 | 10 | [56] |

| MoS2/CF | Vaccum infiltration | 0.05-3 | 240/500 | 171 | 5 | [57] |

| MoS2/single-wall carbon nanotubes |

Liquid phase exfoliation | 0.1-3 | 390/100 | 192 | 20 | [58] |

| N-doped hollow MoS2/C Nanospheres |

Hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 128/5000 | 242 | 5 | [59] |

| MoS2/graphene | Ball milling/exfoliation | 0.01-2.7 | 421/250 | 201 | 50 | [60] |

| MoS2/S-doped graphene | Hydrothermal | 0.005-3 | 309/1000 | 264 | 5 | [61] |

| Fe3O4/MoS2 graphite paper | Modified hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 388/300 | 231 | 3.2 | [62] |

| 1T MoS2/graphene tube | Solvothermal | 0.01-3 | 313/200 | 175 | 2 | [63] |

| MoS2/cotton-derived carbon fibers |

Electrospinning | 0.01-3.0 | 323.1/150 | 355.6 | 2 | [64] |

| NBT/C/MoS2 NFs | Hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 448.2/600 | 2000 | 200 | [65] |

| N-doped amorphous micron-sized carbon ribbons /MoS2 |

One-pot hydrothermal | 0.01-3.0 | 305/300 | 302 | 2 | [66] |

| Hollow flower-like MoS2/C-RGO |

Facile acid precipitation | 0.01-3 | 637/50 | 467 | 1 | [67] |

| amorphous MoS3/carbon nanotube |

Solvothermal | 0.05-2.8 | 565/100 | 2350 | 20 | [68] |

| MoSe2/N, P-rGO | One-step hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 378/1000 | 216 | 15 | [69] |

| MoSe2/MWCNT | In-situ hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 459/90 | 385 | 2 | [70] |

| VS4-rGO | Hydrothermal | 0.01-3 | 540/50 | 123 | 20 | [71] |

| VS4-rGO | Facile hydrothermal | 0.01-2.2 | 241/50 | 219.9 | 0.5 | [72] |

| CogSg/C nanospheres | Facile solvothermal | 0.01-3 | 305/1000 | 297 | 5 | [73] |

| CoS2/multichannel carbon nanofibers |

0.4-2.9 | 315.7/1000 | 201.9 | 10 | [74] | |

| CoSe2MWCNT | Simple hydrothermal | 1-2.9 | 568/100 | 550.5 | 0.8 | [75] |

| Sb2S3 nanorods/C | Facile hydrothermal | 0-2 | 570/100 | 337 | 2 | [76] |

| Sb2S3/S-doped graphene sheets |

Ultrasonication | 0.01-2.5 | 524.4/900 | 591.6 | 5 | [77] |

| ZnSeSb2S3/C | Sulfurisation reaction | 0.01-1.8 | 630/120 | 390.6 | 0.8 | [78] |

| Sb2Se3/C rods | Self-assembly reaction | 0.01-2.5 | 485.2/100 | 311.5 | 2 | [79] |

| Sb2Se3 nanowire-based membrāne |

Hydrothermal/vaccum filtration | 0.01-2 | 296/50 | 153 | 1.6 | [80] |

| SnS/3D N-doped graphene | Facile, self-assembly method | 0.01-25 | 509.9/1000 | 404.8 | 6 | [81] |

| NiS2/CoS2/N-doped carbon coreshell nanocubes |

Co-precipitation method | 0.01-3 | 600/250 | 560 | 5 | [82] |

| TMC/Cathode Composite | Initial Capacity (mAh g−1) | Sustained Capacity/Retention | Rate Capability mA g−1 | Cycle Life/Retention | Ref. |

| 2H–MoS2 | 100–150 | ~100 after 50 cycles | 100 | 50 cycles | [99,100] |

| 1T–VS2 | 133 | 95% after 100 cycles | 100 | 100 cycles | [101] |

| V0.63Mo0.46S2 (VMS) | 211 | 82.7% after 500 cycles (1000 mA/g) | 100–1000 | 500 cycles | [99] |

| Expanded TiS2 | 239 | >80% after 200 cycles | 24 | 200 cycles | [99] |

| Mo6S8 (Chevrel phase) | ~120 | Stable >2000 cycles | 20 | >2000 cycles | [102] |

| MoS2/rGO composite | 160–190 | 95% after 100 cycles | 20-50 | 100 cycles | [99] |

| VS4@rGO (pillar ext.) | 268 | — | 50 | — | [99] |

| N-doped MoS2 | 120–132 | — | 100 | — | [103] |

| TiS2/VS2 hetero | Not specified | Predicted stable | — | — (DFT-guided) | [104] |

| MoS2-CoSe2 hybrids | 200–240 | — | 100 | — | [105] |

| MgMo6S8₋ySey (Se-doped) | 140–154 | — | — | — | [106] |

| WS2 nanosheets | 98 | — | 100 | — | [107] |

| TiS2/MoS2 composites | >220 | Good after >100 cycles | 50 | >100 cycles | [99] |

| VS2 (defective) | Up to 160 | — | 100 | — | [99] |

| NiS2 | 120–170 | — | 50-100 | — | [103] |

| CoS2/CoSe2 hybrids | 225 | — | 100 | — | [103] |

| TiS2/MgO composite | 200 | — | 80 | — | [102] |

| VSe2 | 178 | — | 100 | — | [102] |

| NiCo2S4 | 185 | Cycle stability enhanced | 100 | — | [103] |

| MoWS2 | 950 | — | — | — | [108] |

| CoS2-CoSe2 in carbon nanofibers | 749 | - | 1000 | 200 | [109,110] |

| Material Class | Specific Material/Composite | Initial Capacity (mAh/g) | Cycle Life/Capacity Retention | Rate Capability | Key Advantages of TMC Over Others | Ref. |

| Transition Metal Chalcogenides (TMC) | CoSe2, N-doped CoSe2, TiS2, VS2, MoS2/rGO | 1200–1500 | >80% retention after 500–1000 cycles | Up to 2C or higher | Superior Mg2+ diffusion, strong polysulfide binding & catalytic activity | [86,111] |

| Metal-Carbon Composites | Sulfur/Graphene, N-doped Carbon/S | 500–900 | Moderate, ~60–70% after 100 cycles | Up to 1C | Lower catalytic activity and polysulfide anchoring compared to TMCs | [46,103] |

| Metal Oxides | MnO2, MoO3, TiO2 | ~400–900 | Good, but fast capacity decay at high current | Up to 1C | Lower electronic conductivity and slower Mg2+ diffusion than TMCs | [112] |

| Metal Nitrides | VN, MoN, TiN | 600–1100 | Moderate cycle retention | Up to 2C | Generally lower catalytic activity for polysulfides compared to TMCs | [112] |

| Metal Sulfides (non-TMC) | NiS2, FeS2 | 1100–1300 | Fair cycling stability (~70% after 200 cycles) | Up to 1–2C | Often less structural stability and poorer rate capabilities | [113] |

| Metal Phosphides | FeP, CoP | 400–1000 | Moderate, typically 50–70% retention | Limited (<1C) | Lower polysulfide affinity, worse cycling stability | [114] |

| Metal Fluorides | FeF3 | <400 | Poor cycling due to insulating nature | Low | Poor conductivity and polysulfide conversion | [115] |

| Material/System | DFT Predicted Mg2+ Diffusion Barrier (eV) | DFT Predicted Binding Energy (eV) | Relevant DFT Electronic Feature | Experimental Capacity (mAh g−1) | Rate/Retention/Remark | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2H–MoS2 | 0.47 | -0.97 (centre hex) | Semiconducting (bandgap) | ~100 at 100 | Poor Mg-ion mobility, poor rate, low retention | [99,100] |

| 1T–VS2 | 0.41 | -1.36 (centre hex est.) | Metallic, low Eg. | ~133 at 100 | Higher Mg-ion mobility, stable | [99] |

| V0.63Mo0.46S2 (VMS) | ~0.44 | – | Defected, expanded layer | 211 at 100 | 82.7% after 500 cycles (1000 mA/g) | [99] |

| TiS2 (expanded) | 0.35 | – | Semi-metallic, expanded | 239 at 24 | Good rate and reversibility | [99] |

| Mo6S8 (Chevrel phase) | <0.2 | – | Metallic, strong Mg2+ affinity | ~120 at 20 | Best cycling cathode, >2000 cycles | [8,102] |

| MoS2/rGO composite | 0.47 | – | Interlayer-coordinated | 160–190 at 20–50 | Improved by a graphene conductive matrix | [99] |

| VS4@rGO (pillar ext.) | 0.61 (Zn)–0.47 (Mg) | – | Open, flexible structure | 268 at 50 | Excellent initial activity | [99] |

| N-doped MoS2 | Lowered barrier by 0.05 - 0.1 | Up to -1.1 | Fermi level upshift | 120–132 at 100 | Improved via dopants | [103] |

| TiS2/VS2 hetero | 0.33 | – | Heterointerface, metallic | Not stated | Predicted best for alkali-experimental data pending | [101] |

| MoS2–CoSe2 hybrids | 0.42–0.45 | -1.0 to -1.4 (composite) | Band alignment, dual redox | 200–240 at 100 | Synergy effect, stable | [102] |

| MgMo6S8₋ySey (Se-doped) | ~0.14 for y=1 | – | Band narrowing, higher DOS | 140–154 (DFT-based) | Improved by Se substitution | [104] |

| WS2 nanosheets | 0.50 | -0.62 | Larger bandgap (pristine) | 98 at 100 | Lower rates than MoS2 | [105] |

| TiS2/MoS2 composites | 0.41–0.44 | – | Expanded band, mixed valence | >220 at 50 | Fast Mg diffusion | [99] |

| VS2 (defective) | <0.40 (vacancy, DFT) | – | More active sites | Up to 160 at 100 | Enhanced by sulfur vacancies | [99] |

| MoS2 (1T phase) | 0.34 | – | Metallic after Li/Na insertion | Not stable for Mg | Phase change is hindered for Mg | [100] |

| NiS2 | 0.39 | -1.22 (center hex) | Conductive | 120–170 at 50–100 | Rapid Mg2+ uptake | [103] |

| CoS2/CoSe2 hybrids | 0.28–0.35 | -1.30 (CoSe2) | High redox eletcronic density | 225 at 100 | Excellent cycling, catalyst [211] | [103] |

| TiS2/MgO composite | <0.3–0.4 (surface) | – | Grain-boundary assisted | 200 at 80 | Improved by grain boundary | [102] |

| VSe2 | 0.37 | -1.05 (center hex) | Metallic, open structure | 178 at 100 | High rate and stability | [102] |

| NiCo2S4 | 0.40 | -1.15 | Multiple redox | 185 at 100 | Cycle stability enhanced | [103] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).