Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

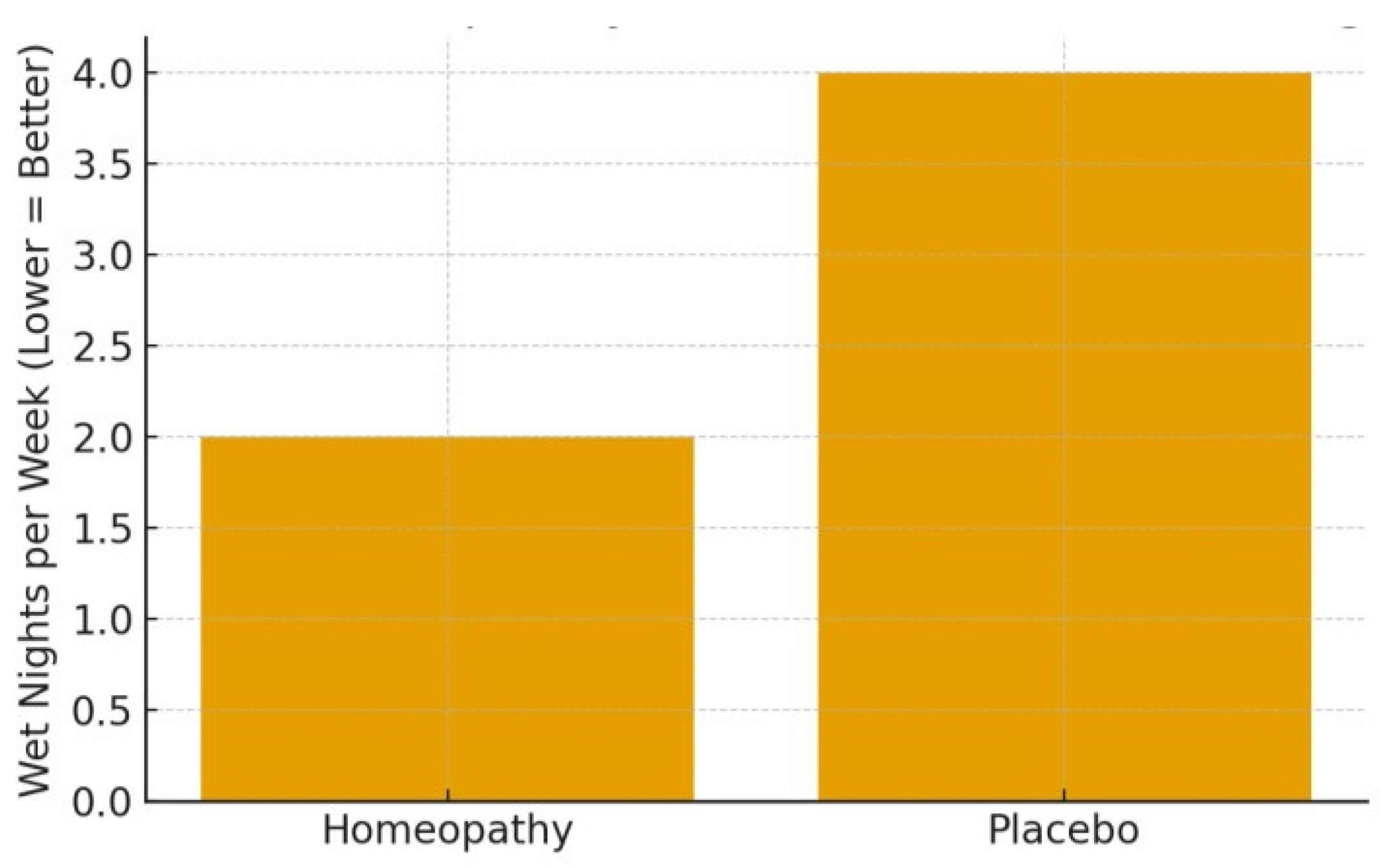

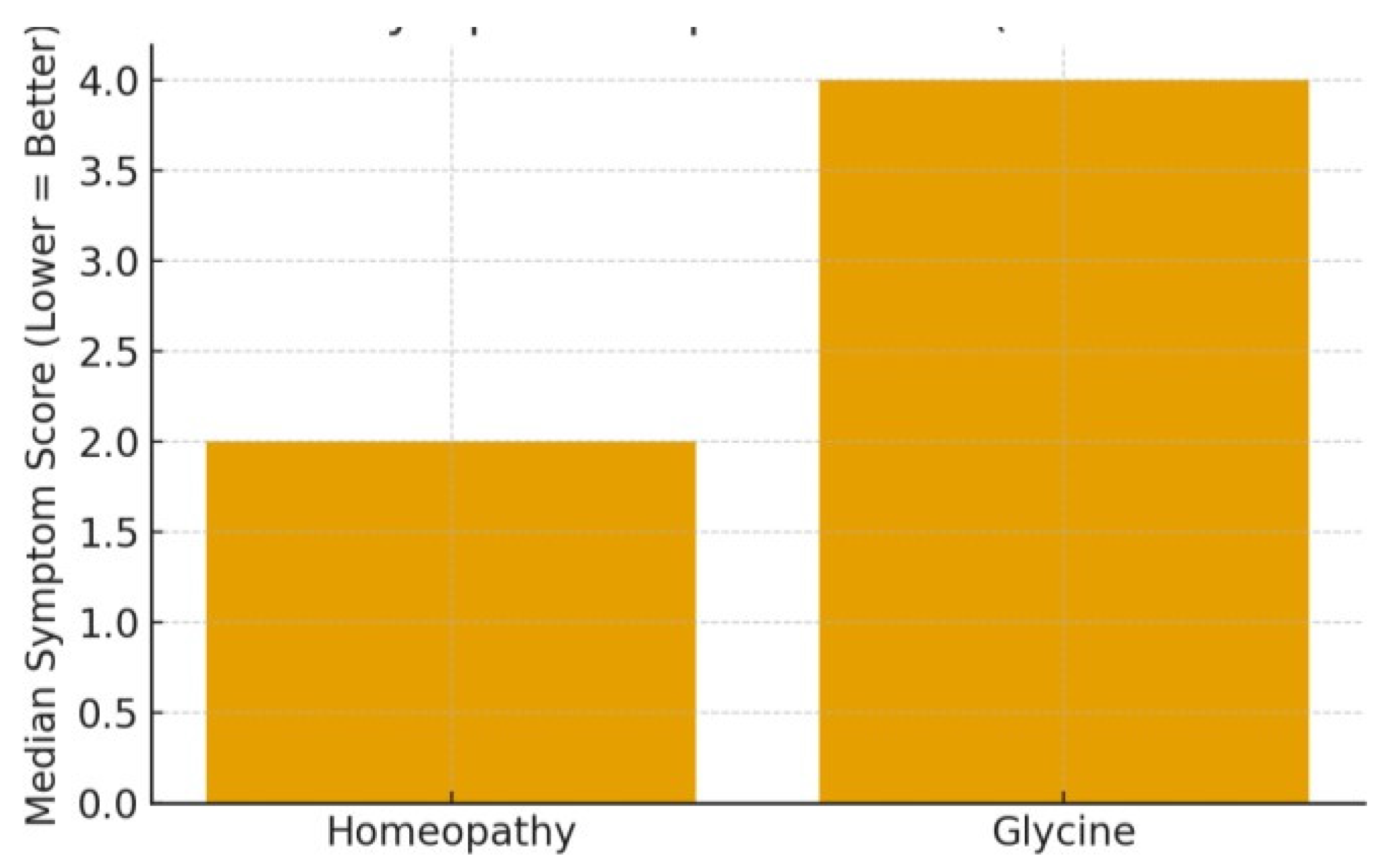

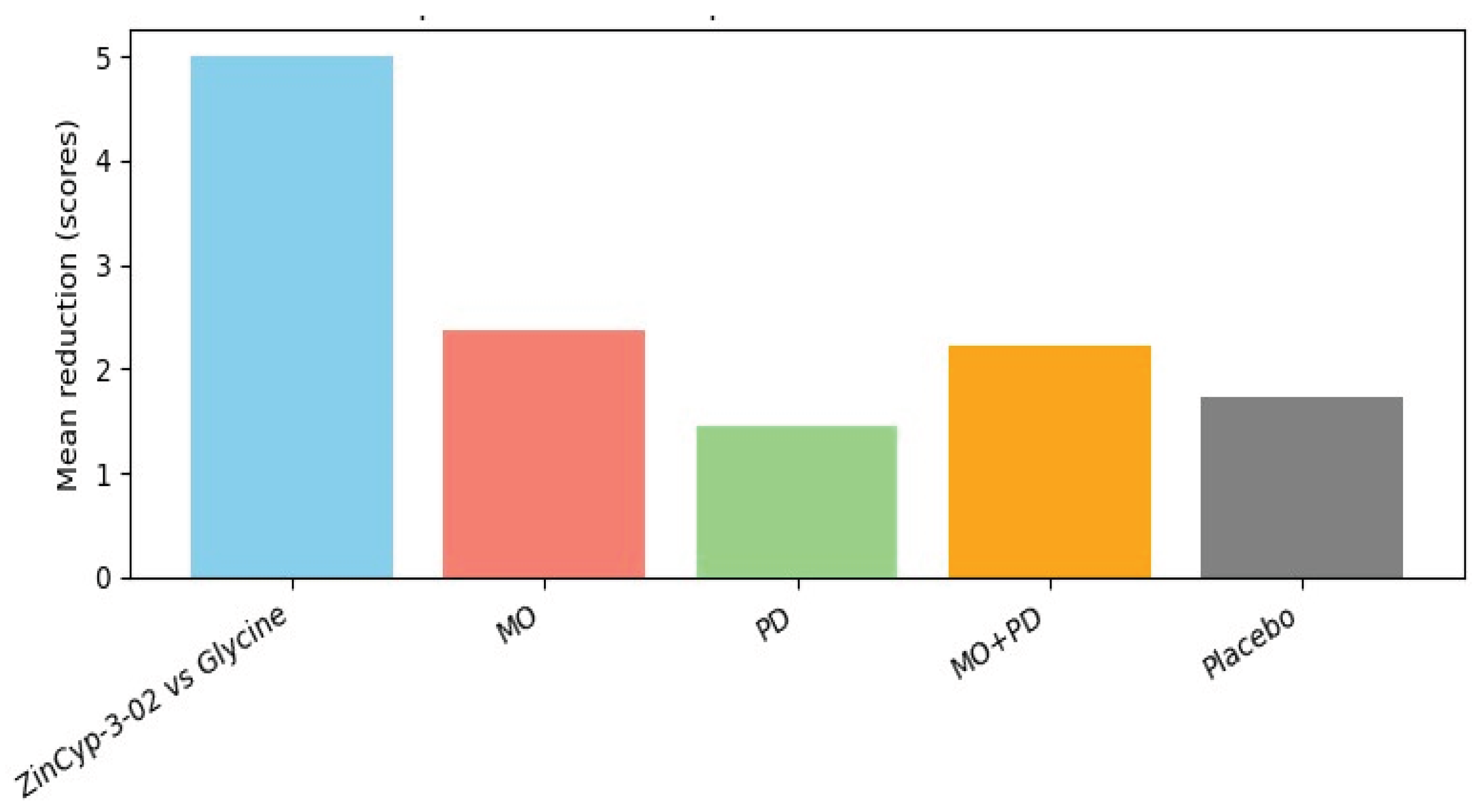

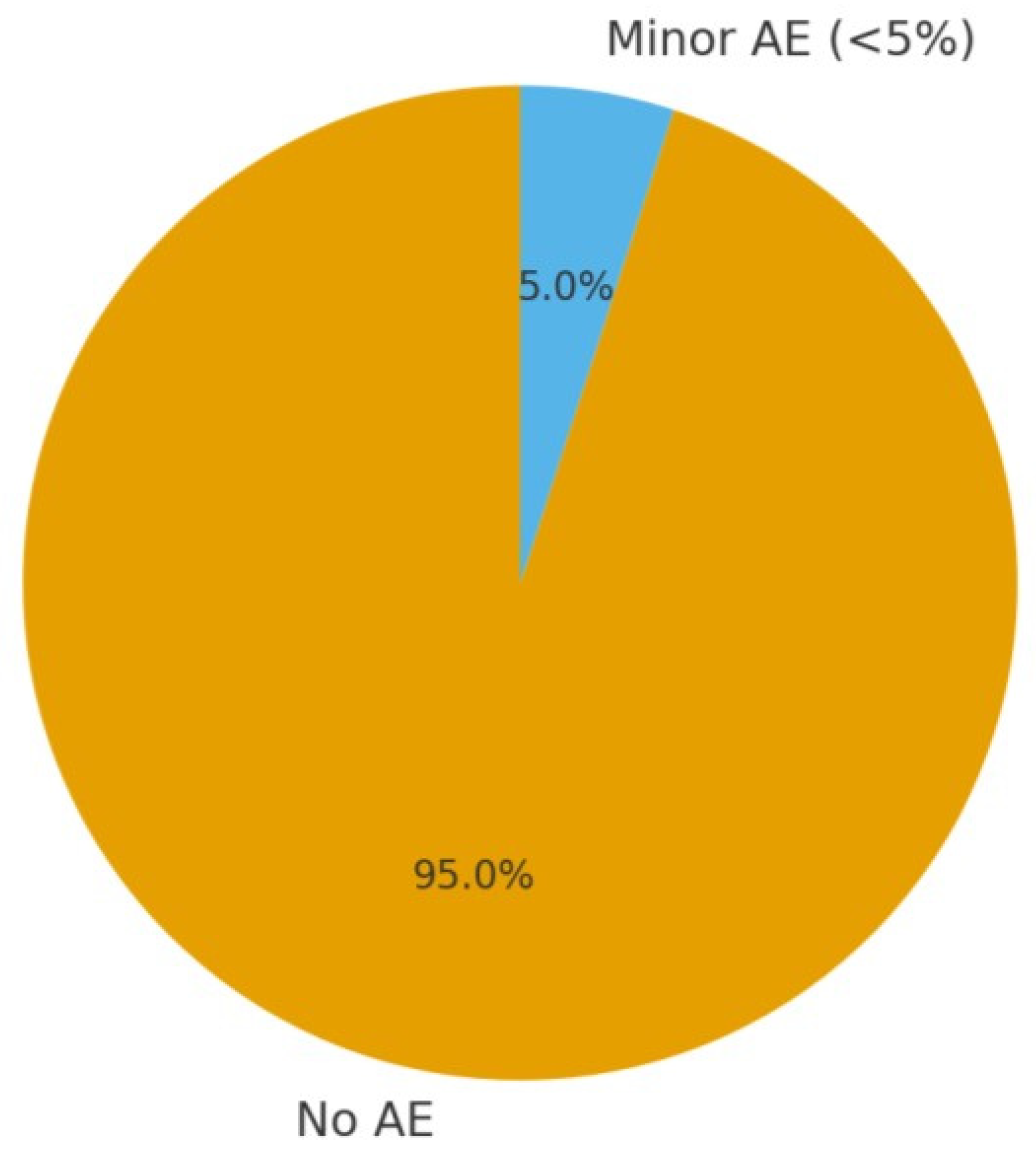

Background: Sleep disorders are common in childhood and adolescence and can negatively affect cognitive development, mood regulation, behaviour and quality of life. Parents frequently seek complementary therapies such as homoeopathy, yet the scientific evidence for homoeopathic treatments in paediatric sleep disorders remains uncertain. This systematic review examines the effectiveness of homoeopathic interventions for sleep disorders in children and adolescents according to evidence-based medicine principles. Objectives: To systematically review and evaluate the effectiveness of homoeopathic treatments for sleep disorders in children and adolescents, following evidence-based principles. We aimed to summarize current clinical evidence from 2015–2025 on whether homoeopathy improves paediatric insomnia and other sleep-related disorders, and to assess the quality of that evidence. Methods: PubMed, Scopus, and allied databases were searched for RCTs and observational studies involving participants <18 years with sleep disorders (insomnia, bruxism, enuresis) treated with homoeopathy. English-language studies were screened manually, and bias was assessed qualitatively. Results: Five studies (three RCTs, two observational; ~400 participants) met inclusion criteria: A multicenter RCT found a complex homoeopathic remedy superior to glycine for insomnia symptom reduction. A crossover RCT reported significant bruxism improvement with Melissa officinalis 12C versus placebo (ΔVAS –2.36 vs –1.72, p≈0.05). A double-blind RCT in enuretic children showed individualized homoeopathy reduced weekly bedwetting episodes (median –2.4 nights, p<0.04). Observational studies also noted symptom improvement. No serious adverse effects were reported. Bias risk varied: one open-label trial showed high risk; others were adequately blinded. Conclusions: Homoeopathic treatments may provide modest benefits for paediatric insomnia, bruxism, and enuresis, with good safety. However, evidence remains limited and heterogeneous. Larger, high-quality trials are warranted before firm recommendations can be made.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Search strings used

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4.3. Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.4.5. Data Synthesis

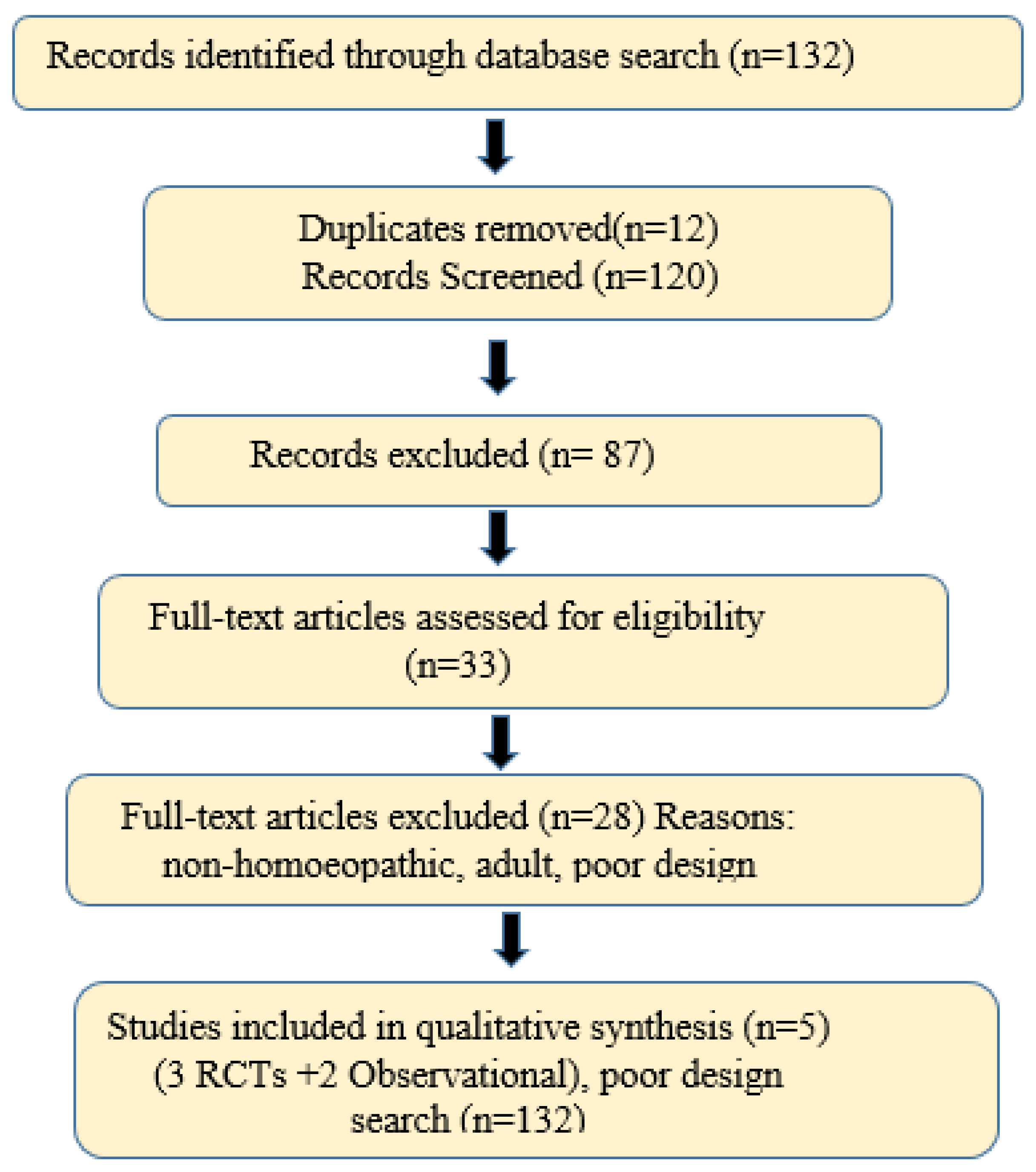

2.4.6. PRISMA Flow and Study Count

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Flow

3.2. Study Characteristics and Populations

3.3. Outcome Measures

3.4. Homoeopathic Interventions and Comparators

- Complex remedy (ZinCyp-3-02): In Jong et al. 2016, the intervention was a fixed combination product “ZinCyp-3-02,” containing three homoeopathic ingredients: Cypripedium pubescens D4, Magnesium carbonicum D10, and Zincum valerianicum D12 [17,21]. This product was formulated specifically for paediatric sleep troubles and restlessness. The dosage regimen was 1 tablet four times daily for 28 days [17]. The comparator was glycine (an amino acid) 100 mg tablets, given on the same schedule [17], as glycine is sometimes used as a mild sedative in Eastern Europe. Glycine served as an active control to benchmark efficacy.

- Individualized single remedies: In the Indian trials on enuresis [16,19], children received individualized homoeopathic medicines. In these, a qualified homoeopathic practitioner evaluated each child and prescribed a remedy tailored to that child’s constitution and symptoms. For instance, in the observational enuresis study, Kreosotum was the most frequently chosen remedy (in ~26% of cases) [19], with others like Calcarea salts and Sulphur also used. The potencies were not explicitly stated but likely in centesimal (commonly 30C or 200C), and dosing was adjusted per clinical response at monthly follow-ups. The RCT by Akram et al. similarly used individualized prescriptions (with Sulphur 30C being the single most common remedy, given to 18.6% of children) [16]. The control arm in that RCT received identical-looking placebo globules, with all children also receiving standard enuresis advice (routine behavioral strategies). The individualized approach means each child’s dosage schedule could differ, but generally remedies were given one to two times daily and changed or repeated as needed over the 3-month period.

- Specific single remedies in a standardized crossover: Tavares-Silva et al. 2019 tested two specific single remedies for bruxism: Melissa officinalis 12C and Phytolacca decandra 12C [18]. These were chosen based on a prior hypothesis or pilot that they might help bruxism. The trial had four arms (in crossover form): Melissa alone, Phytolacca alone, Melissa + Phytolacca in combination, and placebo. Each treatment was given for 30 days. The dosing was reported as 5 globules once every night at bedtime (common practice in such trials, though the abstract did not detail it). There was a 15-day washout between each phase [18]. All participants eventually received each treatment in randomized order. No conventional treatment was given concurrently, and parents were advised to maintain regular bedtime routines.

- Homoeopathic complexes vs placebo: (No included study used an over-the-counter complex like Hyland’s Calming Tablets or Sedatif-PC vs placebo in the last 10 years, although older studies like Cialdella 2001 did that [21]. One open-label French study in 2016 observed Passiflora Compose use, but it was in adults so not in our table.)

| Author(s) (Year) | Homoeopathic Medicine Name(s) |

Potency & Dosage/Regimen |

Treatment Duration | Control/Comparator (if any) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jong et al. (2016)[17] | ZinCyp-3-02 (complex of Cypripedium D4, Magnesia carb. D10, Zincum valerianicum D12) |

1 tablet 4 times daily (dissolved in water for <3 yrs.) | 4 weeks (28 days) | Glycine 100 mg tablet, 4× daily (active comparator) |

| Tavares-Silva et al. (2019) [18] | Melissa officinalis 12C; Phytolacca decandra 12C; (also combined MO+PD) |

5 globules once nightly (implied); Crossover: each child got 30 days of each regimen, with 15-day washouts | 4 × 30-day phases (crossover, total ~5 months) | Placebo (matching globules) during one phase of crossover |

| Akram et al. (2025)[16] | Individualized homoeopathic remedy (e.g. Sulphur, Calc. phosphorica, Calc. carbonica, etc., chosen per case) | Potency varied (commonly 30C/200C); given typically once or twice daily; remedy could be adjusted at monthly visits |

3 months (with monthly follow-ups) | Placebo globules (identical look/taste) + standard care advice (fluid restriction, alarms etc.) |

| Saha et al. (2018)[19] | Individualized homoeopathic medicine (most common: Kreosotum in 26% cases, others like Sulphur, Nux vomica etc.) | Potency 30C or 200C (typical), dosage individualized (e.g. one dose nightly); adjustments made at 2-month and 4month visit if needed | 4 months total (evaluation at 2 and 4 months) | None (no control group in this single arm trial) |

| Harrison et al. (2013)[20] (not in final synthesis) | Complex Homoeopathic blend for insomnia (included Coffea 30C, etc.) |

2 tablets at bedtime (per author’s report) | 4 weeks | Placebo tablets (double-blind) |

3.5. Outcomes and Efficacy Results

3.5.1. Paediatric Insomnia/General Sleep Disturbance

3.5.2. Sleep Bruxism

3.5.3. Nocturnal Enuresis (Bedwetting)

3.5.4. Summary of Efficacy

3.5.5. Safety Profile

3.5.6. Results Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Consistency with Previous Work

4.3. Biological Plausibility

4.4. Clinical Significance

4.5. Limitations of Current Evidence

4.6. Comparative Effectiveness and Integrative Approach

4.7. Implications for Future Research

4.8. Limitations of this Review

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jong MC, Ilyenko L, Kholodova I, Verwer C, Burkart J, Weber S, Keller T, Klement P: A Comparative Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial on the Effectiveness, Safety, and Tolerability of a Homoeopathic Medicinal Product in Children with Sleep Disorders and Restlessness. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM 2016;2016:9539030. [CrossRef]

- Carter KA, Hathaway NE, Lettieri CF: Common sleep disorders in children. American family physician 2014;89:368-377.

- Nunes ML, Bruni O: Insomnia in childhood and adolescence: clinical aspects, diagnosis, and therapeutic approach. Jornal de pediatria 2015;91:S26-35.

- Beebe DW: Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Paediatric clinics of North America 2011;58:649-665. [CrossRef]

- Suri J, Sen M, Adhikari T: Epidemiology of Sleep Disorders in School Children of Delhi: A Questionnaire Based Study. Indian Journal of Sleep Medicine 2008;3:42-50. [CrossRef]

- Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, Moffitt TE, Oconnor TG, Poulton R: Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. Journal of abnormal child psychology 2005;33:157-163. [CrossRef]

- Ogundele MO, Yemula C: Management of sleep disorders among children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders: A practical guide for clinicians. World journal of clinical paediatrics 2022;11:239-252. [CrossRef]

- El Halal CDS, Nunes ML: Sleep disorder assessment in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders. Jornal de pediatria 2025;102 Suppl 1:101441.

- Lah S, Cao TV: Outcomes of remotely delivered behavioral insomnia interventions for children and adolescents: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Sleep 2024;Volume 2 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh MS, Holmes R, Hsu F: Pharmacologic Treatments for Sleep Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review. Journal of child neurology 2019;34:237-247. [CrossRef]

- Dhir S, Karim N, Berka H, Shatkin J: Pharmacological management of paediatric insomnia. Frontiers in Sleep 2024;Volume 3 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Paditz E, Renner B, Koch R, Schneider B, Schlarb A, Ipsiroglu O: Pharmacokinetics, Dosage, Preparation Forms, and Efficacy of Orally Administered Melatonin for Non-Organic Sleep Disorders in Autism Spectrum Disorder During Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. submitted for publication 2025. [CrossRef]

- Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD: Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner journal 2012;12:45-56.

- Gaertner K, Ulbrich-Zürni S, Baumgartner S, Walach H, Frass M, Weiermayer P: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in Homoeopathy: Recommendations for summarising evidence from homoeopathic intervention studies (Sum-HomIS recommendations). Complementary therapies in medicine 2023;79:102999.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2021;372:n71.

- Akram J, Basu A, Hossain MS, Bhattacharyya S, Shamim S, Debnath P, Rahaman R, Goswami S, Nag U, Ghosh P, Rahaman Shaikh A, Chatterjee C, Koley M, Saha S, Saha S, Mukherjee SK: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of individualized homoeopathic medicinal products in the treatment of nocturnal enuresis in children. Explore (New York, NY) 2025;21:103077. [CrossRef]

- Jong M, Ilyenko L, Хoлoдoва И, Verwer C, Burkart J, Weber S, Keller T, Klement P: A Comparative Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial on the Effectiveness, Safety, and Tolerability of a Homoeopathic Medicinal Product in Children with Sleep Disorders and Restlessness. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016;2016:1-11.

- Tavares-Silva C, Holandino C, Homsani F, Luiz RR, Prodestino J, Farah A, Lima JP, Simas RC, Castilho CVV, Leitão SG, Maia LC, Fonseca-Gonçalves A: Homoeopathic medicine of Melissa officinalis combined or not with Phytolacca decandra in the treatment of possible sleep bruxism in children: A crossover randomized triple-blinded controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine: international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2019;58:152869.

- Saha S, Tamkeen R, Saha S: An open observational trial evaluating the role of individualised homoeopathic medicines in the management of nocturnal enuresis. Indian Journal of Research in Homoeopathy 2018;12:149.

- Harrison CC, Solomon EM, Pellow J: The effect of a homoeopathic complex on psychophysiological onset insomnia in males: a randomized pilot study. Alternative therapies in health and medicine 2013;19:38-43.

- Kotian S, Noronha R: Insights on childhood insomnia and its Homoeopathic treatment approaches – A narrative review. Journal of Integrated Standardized Homoeopathy 2024;7:19-27. [CrossRef]

- Bell IR, Howerter A, Jackson N, Aickin M, Baldwin CM, Bootzin RR: Effects of homoeopathic medicines on polysomnographic sleep of young adults with histories of coffee-related insomnia. Sleep medicine 2011;12:505-511. [CrossRef]

- Michael J, Singh S, Sadhukhan S, Nath A, Kundu N, Magotra N, Dutta S, Parewa M, Koley M, Saha S: Efficacy of individualized homoeopathic treatment of insomnia: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complementary therapies in medicine 2019;43:53-59. [CrossRef]

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H: The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011;34:601-608. [CrossRef]

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM: Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine 2001;2:297-307. [CrossRef]

- Morin CM: Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford press; 1993.

- Baglioni C, Bostanova Z, Bacaro V, Benz F, Hertenstein E, Spiegelhalder K, Rücker G, Frase L, Riemann D, Feige B: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Evaluating the Evidence Base of Melatonin, Light Exposure, Exercise, and Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Patients with Insomnia Disorder. Journal of clinical medicine 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Sánchez J, Garza-Treviño G: Individualized Homoeopathic Treatment for Persistent Insomnia and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Case Report. Cureus 2024;16:e67203. [CrossRef]

- Brulé D, Landau-Halpern B, Nastase V, Zemans M, Mitsakakis N, Boon H: A Randomized Three-Arm Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study of Homoeopathic Treatment of Children and Youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of integrative and complementary medicine 2023;30:279-287. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA: Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for paediatric insomnia. Journal of paediatric psychology 2014;39:932-948. [CrossRef]

- van Geijlswijk IM, van der Heijden KB, Egberts AC, Korzilius HP, Smits MG: Dose finding of melatonin for chronic idiopathic childhood sleep onset insomnia: an RCT. Psychopharmacology 2010;212:379-391. [CrossRef]

- Paditz E: Melatonin bei Schlafstörungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde 2024;172:44-51.

- Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, Panunzi S, Valente D: Controlled-release melatonin, singly and combined with cognitive behavioural therapy, for persistent insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of sleep research 2012;21:700-709. [CrossRef]

- Tse ACY, Lee PH, Sit CHP, Poon ET, Sun F, Pang CL, Cheng JCH: Comparing the Effectiveness of Physical Exercise Intervention and Melatonin Supplement in Improving Sleep Quality in Children with ASD. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2024;54:4456-4464. [CrossRef]

| Author(s) (Year) | Country | Study Design | Sample Size |

Age Range | Sleep Disorder Type | Outcome Measures (Key) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jong et al. (2016)[17] | Russia (multicenter) |

RCT (open- label, active control) |

N = 179 (89 vs 90) | 1–6 years (young children) | Insomnia & restlessness (≥1 month) | Total complaints severity score; time to sleep onset; night awakenings; Integrative Medicine Outcome Scale (IMOS); patient/parent satisfaction (IMPSS) |

| Tavares- Silva et al. (2019)[18] |

Brazil | RCT (crossover, triple-blind, placebo controlled) |

N = 52 (crossover) |

Mean 6.6 ±1.8 years (range 5–12) |

Possible sleep bruxism (teeth grinding) | Parental VAS for bruxism severity; sleep diary (sleep quality); Trait Anxiety Scale for Children (TAS); side effects log |

| Akram et al. (2025) [16] |

India | RCT (parallel, double-blind, placebo controlled) | N = 140 (70 vs 70) | 5–16 years (children & adolescents) | Nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) | Frequency of bedwetting (episodes/week); Paediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) child & parent report; cure rate (dry nights); adverse events |

| Saha et al. (2018)[19] | India | Observational (pre–post single arm) | N = 34 | 5–18 years | Nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) | Nocturnal enuresis severity score (custom 0–15 scale counting nights and intensity); measured at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months |

| Harrison et al. (2013)[20] (Excluded from final) | UK (for context) | RCT (double-blind, placebo controlled) | N = 46 | 7–12 years (all male) |

Psychophysiological insomnia (PI) | Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS); sleep diaries; global improvement (Note: Older study, outside 10-year range) |

| Author(s) (Year) | Domain Assessed | Bias Assessment Method (Narrative) |

Judgment / Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jong et al. (2016)[17] | Blinding (Performance/Detection) |

Evaluated as openlabel design; outcome (symptom score) rated by investigators/parents aware of treatment | High risk – Lack of blinding could inflate perceived improvements in homoeopathy arm (observer expectancy bias) |

| Tavares-Silva et al. (2019) [18] | Selection Bias (Randomization) |

Reviewed randomization procedure in tripleblind RCT; assignment was random and crossover counterbalanced (each child as own control) | Low risk – Proper random sequence and allocation; crossover design with each child receiving all treatments reduces between-group differences |

| Tavares-Silva et al. (2019) [18] | Carryover Effect (Crossover) | Analyzed washout adequacy (15 days) and period effect; no significant period/order effects reported by authors | Some concerns – 15-day washout may not fully prevent carryover, but unlikely major issue given homoeopathic 12C likely has transient effect; overall design robust |

| Akram et al. (2025)[16] | Performance/Detection Bias |

Double-blind RCT: patients, prescribers, and evaluators blinded; outcomes (bedwetting frequency) objective count by parents, likely unbiased by group |

Low risk – Blinding was maintained; placebo identical to verum, minimizing expectation bias. (Slight risk if parents guessed treatment due to improvement, but unlikely) |

| Akram et al. (2025)[16] | Attrition Bias | Monitored drop-outs (only 4 total dropouts, evenly split); used intention-totreat analysis for primary outcome | Low risk – Minimal attrition and no differential loss between groups; results robust |

| Saha et al. (2018)[19] | Confounding (Study Design) | Observational onegroup pre-post; no control for placebo effect or maturation; baseline to outcome comparison only | High risk – Improvement could partly reflect spontaneous resolution or parent perception changes; positive results must be interpreted cautiously without a control group |

| All studies (general) | Reporting Bias | Checked outcomes vs methods for each study; all predefined outcomes reported, no selective omission noted (e.g. non significant diaries in Tavares study were acknowledged) |

Low risk – No evident selective reporting. Publication bias in field is possible (negative trials may be unpublished), but within included studies, reporting was transparent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).