Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

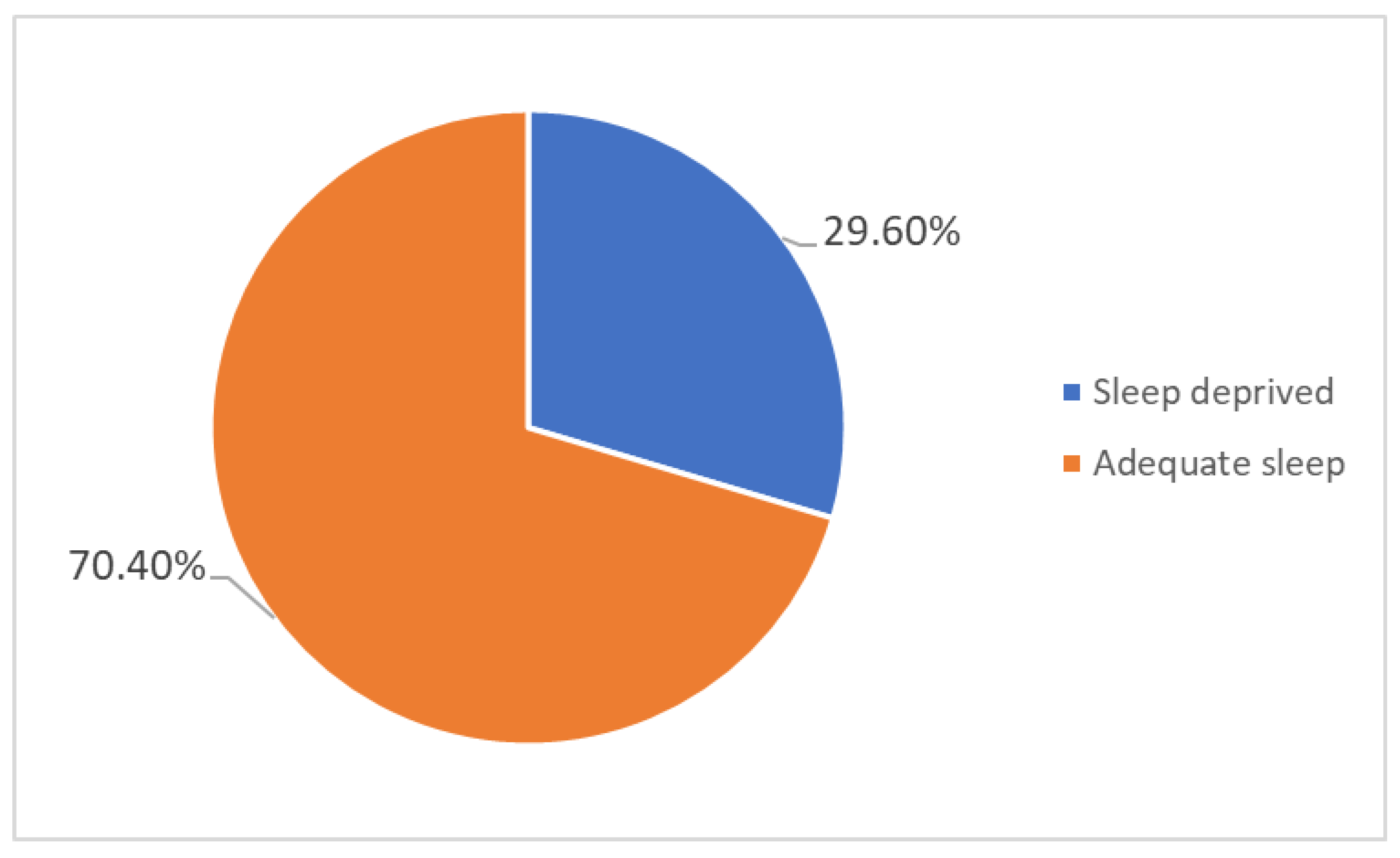

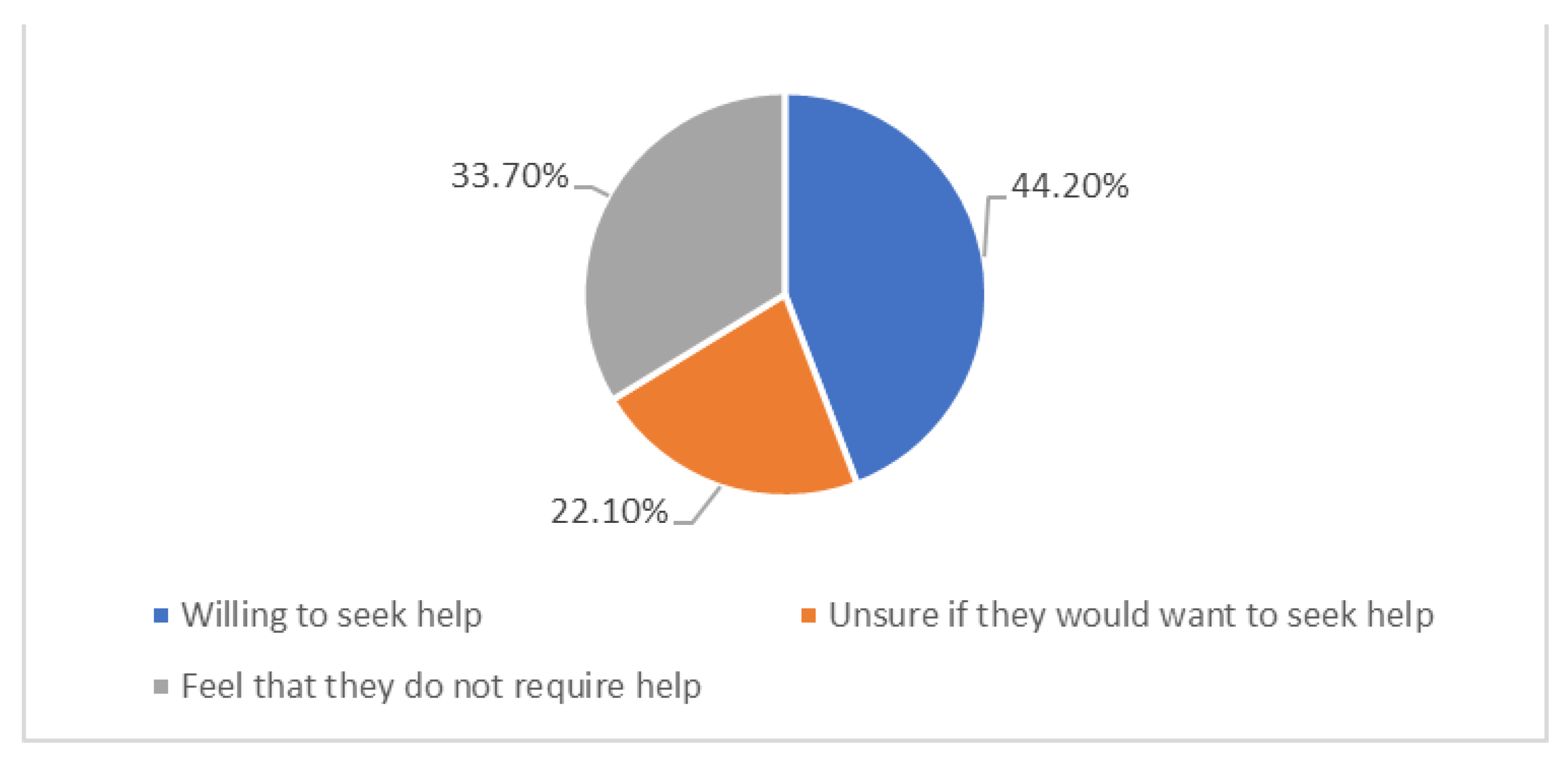

Introduction: Sleep deprivation is a global health concern with significant clinical, economic, and social consequences. The CDC recommends that adults aged 18-60 get at least 7 hours of sleep per night for optimal health. Studies conducted in Singapore, Japan and China have highlighted a significant prevalence of poor sleep quality and insomnia across Asia, with 26.4% of men and 31.1% of women in Japan reporting poor sleep. This study set out to determine the prevalence of sleep deprivation amongst adults in UAE on their physical and mental health. Methods: We used a cross-sectional design with mixed methods to explore sleep deprivation among adults aged 18-65 in all seven emirates of UAE. We used stratified cluster sampling to identify the sample. The sample size was calculated using StatCalc, and IBM software. Data was collected using a tool called 'Sleep Disorders Questionnaire for adults aged 11+' and the data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Results/DISCUSSION: The study sample consisted of 321 participants, and included all the ethnic groups resident in Dubai. The largest group of participants included South Asians (59%), and those younger than 25 years (51.4%). 29.6% (95) of the participants experienced sleep deprivation. Participants in the sleep deprived category reported frequent headaches (25%). 22% (21) of the participants in the sleep deprived category reported experiencing feelings of depression/hopelessness. Researchers often link sleep deprivation to metabolic and cardiovascular issues and frequent physical and mental symptoms, and the exact relationship and correlation between sleep and health requires more research Conclusion: The willingness of many sleep-deprived individuals to seek help offers a promising avenue for intervention. Policymakers have an opportunity to integrate sleep health into broader public health initiatives aimed at improving the well-being of UAE residents by addressing the root causes of sleep deprivation and promoting healthy sleep habits.

Keywords:

Introduction:

- -

- To determine the effect of sleep deprivation on mental health among adults in the UAE.

- -

- To determine the effect of sleep deprivation on physical health among adults in the UAE.

- -

- To determine the primary contributing factors that cause sleep deprivation

- -

- To investigate modifiable behaviour patterns that can improve sleep deprivation

- -

- To generate evidence to aid policy and public health education

Materials and Methods:

Study Design

Research Methods

Population and Sample

Data Collection and Tool

Ethics Approval

Data Analysis

Results:

Demographics

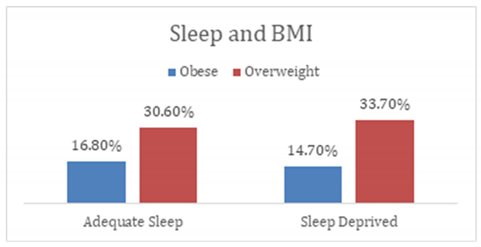

Sleep Deprivation and Physical Health

Sleep Deprivation and Mental Health

Discussion

Conclusion:

Author contributions

Funding statement

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- CDC. (2024, ). About Sleep. Sleep. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/how_much_sleep.html. 2 April.

- More than 40% of UAE residents are not getting enough quality sleep. (2024). Premierinn.com. https://mena.premierinn.

- Badri, M.; Alkhaili, M.; Aldhaheri, H.; Yang, G.; Albahar, M.; Alrashdi, A. From good sleep to health and to quality of life – a path analysis of determinants of sleep quality of working adults in Abu Dhabi. Sleep Sci. Pr. 2023, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, M.; Saade, M.; AlBuhairan, F. Sleep deprivation: prevalence and associated factors among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Sleep Med. 2019, 53, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.M.; Maslowsky, J.; Hamilton, A.; Schulenberg, J. The Great Sleep Recession: Changes in Sleep Duration Among US Adolescents, 1991–2012. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-López, J.; de Carvalho, H.; de Moraes, A.; Ruiz, J.; Sjöström, M.; Marcos, A.; Polito, A.; Gottrand, F.; Manios, Y.; Kafatos, A.; et al. Sleep time and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents: The HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) study. Sleep Med. 2013, 15, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shen, X.; Li, S. Sleep duration in Chinese adolescents: biological, environmental, and behavioral predictors. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohida, T.; Osaki, Y.; Doi, Y.; Tanihata, T.; Minowa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Wada, K.; Suzuki, K.; Kaneita, Y. An Epidemiologic Study of Self-Reported Sleep Problems among Japanese Adolescents. Sleep 2004, 27, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haifi, A.A.; Al-Majed, H.T.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Musaiger, A.O.; Arab, M.A.; Hasan, R.A. Relative Contribution of Obesity, Sedentary Behaviors and Dietary Habits to Sleep Duration Among Kuwaiti Adolescents. Glob. J. Heal. Sci. 2015, 8, p107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Musaiger, A.O.; Abahussain, N.A.; Al-Sobayel, H.I.; Qahwaji, D.M. Lifestyle correlates of self-reported sleep duration among Saudi adolescents: a multicentre school-based cross-sectional study. Child: Care, Heal. Dev. 2013, 40, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Al-Jahdali, F.; AlALwan, A.; Abuabat, F.; Bin Salih, S.A.; Al-Harbi, A.; Baharoon, S.; Khan, M.; Ali, Y.Z.; Al-Jahdali, H. Prevalence of sleep duration among Saudi adults. Saudi Med J. 2017, 38, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Lau, J.H.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Sambasivam, R.; Shafie, S.; Chua, B.Y.; Chow, W.L.; Abdin, E.; Subramaniam, M. Sleep quality of Singapore residents: findings from the 2016 Singapore mental health study. Sleep Med. X 2022, 4, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Hsu, N.-W.; Chou, P. Subgrouping Poor Sleep Quality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Latent Class Analysis - The Yilan Study, Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Minowa, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Okawa, M. Subjective sleep quality and sleep problems in the general Japanese adult population. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001, 55, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Kelly, B.C.; Qi, C.; Pan, C.; Yang, M.; Hao, W.; Liu, T.; Tang, J. Sleep quality in cigarette smokers and nonsmokers: findings from the general population in central China. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liao, Y.; Kelly, B.C.; Xie, L.; Xiang, Y.-T.; Qi, C.; Pan, C.; Hao, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, F.; et al. Gender and Regional Differences in Sleep Quality and Insomnia: A General Population-based Study in Hunan Province of China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.S.; Fielding, R. Prevalence of insomnia among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a population-based study. J. Sleep Res. 2011, 20, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self-reported sleep quality in a multi-ethnic Asian population. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 14–14. [CrossRef]

- In recognition of World Sleep Day, Philips presents its annual global sleep survey results. (n.d.). Philips. https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2019/20190307-in-recognition-of-world-sleep-day-philips-presents-its-annual-global-sleep-survey-results.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Constitution of the world health organization. World Health Organization. https://www.who.

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2010, ). A healthy lifestyle - WHO recommendations. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations. 6 May.

- Cooper, C.B.; Neufeld, E.V.; Dolezal, B.A.; Martin, J.L. Sleep deprivation and obesity in adults: a brief narrative review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Dutil, C.; Featherstone, R.; Ross, R.; Giangregorio, L.; Saunders, T.J.; Janssen, I.; Poitras, V.J.; Kho, M.E.; Ross-White, A.; et al. Sleep duration and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, S218–S231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripke, D.F.; Simons, R.N.; Garfinkel, L.; Hammond, E.C. Short and Long Sleep and Sleeping Pills. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1979, 36, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medic, G. , Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017, ). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5449130/#:~:text=have%20been%20reported.-,Short%2Dterm%20consequences%20of%20sleep%20disruption%20include%20increased%20stress%20responsivity,problems%20in%20otherwise%20healthy%20individuals. 19 May.

- Al Balushi, M.; Al Balushi, S.; Javaid, S.; Leinberger-Jabari, A.; Al-Maskari, F.; Al-Houqani, M.; Al Dhaheri, A.; Al Nuaimi, A.; Al Junaibi, A.; Oumeziane, N.; et al. Association between depression, happiness, and sleep duration: data from the UAE healthy future pilot study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, M.G.; Mahboub, B.H.; Al Hariri, H.; Al Zaabi, A.; Vats, D. Obesity and Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in Middle East and UAE. Can. Respir. J. 2016, 2016, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good health and well-being | The Official Portal of the UAE Government. (n.d.). https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/leaving-no-one-behind/3goodhealthandwellbeing.

- Introduction | StatCalc | User Guide | Support | EPI InfoTM | CDC. (n.d.). https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/user-guide/statcalc/statcalcintro.html.

- Sleep Disorders Clinic, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, John Radcliffe Hospital, Sleep questionnaire for adults. (n.d.). https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/children/services/medical-services/documents/sleep-questionnaire-over-11.pdf.

- Stanford Medicine (2024), Pfizer Inc. - PHQ-9 Patient Depression Questionnaire, https://med.stanford.edu/fastlab/research/imapp/msrs/_jcr_content/main/accordion/accordion_content3/download_256324296/file.res/PHQ9%20id%20date%2008.03.pdf.

- Buchanan, B. (2024b, ). Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7). NovoPsych. https://novopsych.com. 9 September.

- IBM SPSS Statistics. (n.d.). https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=43700077616110376&p5=e&p9=58700008513382664&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwpvK4BhDUARIsADHt9sRhNHK_UfgTZl79Rd-tjasfH0edAro57R9YrUo5cpYI9QMzSamDy8QaArfqEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Age-group-comparison-between-Young-adult-18-25-age-Adult-26-44-age-Middle-age_tbl1_338842581.

- Roberts, R.E.; Duong, H.T. The Prospective Association between Sleep Deprivation and Depression among Adolescents. Sleep 2014, 37, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2010, ). A healthy lifestyle - WHO recommendations. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations. 6 May.

- Wong, W.S.; Fielding, R. Prevalence of insomnia among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a population-based study. J. Sleep Res. 2011, 20, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J. A. , & Huecker, M. R. (2023, ). Sleep deprivation. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547676/. 12 June.

- Xiao, Q.; Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Matthews, C.E. A Large Prospective Investigation of Sleep Duration, Weight Change, and Obesity in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiology 2013, 178, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, D. Sleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Malaspina, D.; Boden-Albala, B.; Heymsfield, S.B. Inadequate Sleep as a Risk Factor for Obesity: Analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep 2005, 28, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattu, V.K.; Manzar, M.D.; Kumary, S.; Burman, D.; Spence, D.W.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. The Global Problem of Insufficient Sleep and Its Serious Public Health Implications. Healthcare 2018, 7, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.D.; Sabanayagam, C.; Shankar, A. The Relationship between Insufficient Sleep and Self-Rated Health in a Nationally Representative Sample. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeda, J.; Mezuk, B.; Ratliff, S.; Ning, Y. Association between duration and quality of sleep and the risk of pre-diabetes: evidence from NHANES. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, K.; Inaba, M.; Hamamoto, K.; Yoda, M.; Tsuda, A.; Mori, K.; Imanishi, Y.; Emoto, M.; Yamada, S. Association between Poor Glycemic Control, Impaired Sleep Quality, and Increased Arterial Thickening in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0122521–e0122521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyegha, I.D.; Chieh, A.Y.; Bryant, B.M.; Li, L. Associations between poor sleep and glucose intolerance in prediabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 110, 104444–104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humans.Txt. (n.d.). Oman Medical Journal-Archive. https://omjournal.org/articleDetails.aspx?coType=1&aId=1825.

- Spiegel, K.; Leproult, R.; Van Cauter, E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet 1999, 354, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, D. , & Pacheco, D. (2023, ). Lack of sleep and diabetes. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/physical-health/lack-of-sleep-and-diabetes. 26 October.

- Dutil, C.; Chaput, J.-P. Inadequate sleep as a contributor to type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Nutr. Diabetes 2017, 7, e266–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, C.; Hagen, E.W.; Johnson, H.M.; Brown, R.L.; Peppard, P.E. Longitudinal sleep characteristics and hypertension status: results from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. J. Hypertens. 2020, 39, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Boden-Albala, B.; Buijs, R.M.; Kreier, F.; Pickering, T.G.; Rundle, A.G.; Zammit, G.K.; Malaspina, D. Short Sleep Duration as a Risk Factor for Hypertension. Hypertension 2006, 47, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covassin, N.; Singh, P. Sleep Duration and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Epidemiologic and Experimental Evidence. 11, 89. [CrossRef]

- Covassin, N.; Singh, P. Sleep Duration and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Epidemiologic and Experimental Evidence. 11, 89. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-F.; Lee, K.-Y.; Lin, T.-C.; Liu, W.-T.; Ho, S.-C. Subjective sleep quality and association with depression syndrome, chronic diseases and health-related physical fitness in the middle-aged and elderly. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poor sleep quality increases inflammation, community study finds. (2010, ). ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/11/101114161939.htm. 10 November.

- Dzierzewski, J.M.; Donovan, E.K.; Kay, D.B.; Sannes, T.S.; Bradbrook, K.E. Sleep Inconsistency and Markers of Inflammation. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.-J.; Yun, C.-H.; Cho, S.-J.; Kim, W.-J.; Yang, K.I.; Chu, M.K. Short sleep duration and poor sleep quality among migraineurs: A population-based study. Cephalalgia 2017, 38, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelman, L.; Rains, J.C. Headache and Sleep: Examination of Sleep Patterns and Complaints in a Large Clinical Sample of Migraineurs. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2005, 45, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whale, K.; Gooberman-Hill, R. The Importance of Sleep for People With Chronic Pain: Current Insights and Evidence. JBMR Plus 2022, 6, e10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.R.; Almeida, D.M.; Klick, B.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Smith, M.T. Duration of sleep contributes to next-day pain report in the general population ☆. PAIN® 2008, 137, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinstrup, J.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Calatayud, J.; Jay, K.; Andersen, L.L. Association of Stress and Musculoskeletal Pain With Poor Sleep: Cross-Sectional Study Among 3,600 Hospital Workers. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinstrup, J.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Andersen, L.L. Poor Sleep Is a Risk Factor for Low-Back Pain among Healthcare Workers: Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, M.; Simpson, N.; Sethna, N.; Kaur, S.; Mullington, J. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 45, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H. (2022, ). Sleep deprivation and memory loss. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/sleep-disorders/sleep-deprivation-effects-on-memory. 2 August.

- Alhola, P.; Polo-Kantola, P. Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. 2007, 3, 553–567.

- Chen, P.; Ban, W.; Wang, W.; You, Y.; Yang, Z. The Devastating Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Memory: Lessons from Rodent Models. Clocks Sleep 2023, 5, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaso, C.C.; Johnson, A.B.; Nelson, T.D. The effect of sleep deprivation and restriction on mood, emotion, and emotion regulation: three meta-analyses in one. Sleep 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Balkin, T.J.; Wesensten, N.J. Impaired decision making following 49 h of sleep deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2006, 15, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghvaee, L.; Mazandarani, A.A. Poor sleep is associated with sensation-seeking and risk behavior in college students. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salfi, F.; Lauriola, M.; Tempesta, D.; Calanna, P.; Socci, V.; De Gennaro, L.; Ferrara, M. Effects of Total and Partial Sleep Deprivation on Reflection Impulsivity and Risk-Taking in Deliberative Decision-Making. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, ume 12, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-024-02549-6.

- Davidson, J. D. (n.d.). The impact of sleep on academic burnout with the effects of perceived stress and general well-being. Scholarship@Western. https://ir.lib.uwo.

- Saintila, J.; Soriano-Moreno, A.N.; Ramos-Vera, C.; Oblitas-Guerrero, S.M.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E. Association between sleep duration and burnout in healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 11, 1268164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Bernert, R. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: A review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, ume 3, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, J.; McDaniel, K.; DiBlanda, A. Association Between Insufficient Sleep, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidality Among Florida High School Students. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Shin, D.; Ahn, Y.M. Association between the number of hours of sleep during weekdays and suicidality among Korean adolescents: Mediating role of depressive and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 320, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summer, J. , & Summer, J. (2023, ). Microsleep: What is it, what causes it, and is it safe? Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/microsleep. 6 January.

- Boyle, L.N.; Tippin, J.; Paul, A.; Rizzo, M. Driver performance in the moments surrounding a microsleep. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C. (2024, ). Microsleeps: The naps that may only last seconds. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240130-microsleeps-the-naps-that-may-only-last-seconds. 31 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, R.; et al. Effect of Sleep Quality on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms among College Students in China’s Xizang Region: The Mediating Effect of Cognitive Emotion Regulation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andishmand, Z.; Amini, A.; Naderi, F.; Garmabi, M.; Sharifnezhad, A.; Darrudi, F.; Gholami, A. Is Sleep Duration Associated With Depression and Anxiety? A Cross-Sectional Study on Medical Students in Iran. Sleep Med. Res. 2023, 14, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, D.J.; Ellenbogen, J.M.; Bianchi, M.T.; Czeisler, C.A. Sleep deficiency and motor vehicle crash risk in the general population: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Houqani, M.; Eid, H.O.; Abu-Zidan, F.M. Sleep-related collisions in United Arab Emirates. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 50, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Percentage (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 76.3% (245) |

| Male | 23.7% (76) | |

| Emirate | Dubai | 45.8% (147) |

| Sharjah | 27.4% (88) | |

| Abu Dhabi | 10.6% (34) | |

| Ajman | 7.8% (25) | |

| Fujairah | 6.5% (21) | |

| Umm Al Quwain | 0.9% (3) | |

| Ras Al Khaimah | 0.9% (3) | |

| Ethnicity | South Asia | 59.2% (190) |

| Middle East | 17.8% (57) | |

| Southeast Asia | 12.55% (40) | |

| African/Caribbean | 5% (16) | |

| East Asia | 4.4% (14) | |

| Americans | 0.9% (3) | |

| European | 0.3% (3) | |

| Age [34] (in years) | Youth (18-24) | 51.4% (165) |

| Young Adult (25-44) | 35.2% (113) | |

| Middle Age (45-65) | 13.4% (43) |

| Physical health conditions | Sleep Duration | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-diabetic/diabetes | Sleep Deprived (4) 4.21% | 0.88 |

| Adequate sleep (16) 7.07% | ||

| High Cholesterol | Sleep Deprived (3) 3.15% | |

| Adequate sleep (9) 3.98% | ||

| Hypertension | Sleep Deprived (2) 2.1% | |

| Adequate sleep (3) 1.32% | ||

| Three comorbidities | Sleep Deprived (1) 1.05% | |

| Adequate sleep (2) 0.88% | ||

| Two comorbidities | Sleep Deprived (5) 5.26% | |

| Adequate sleep (8) 3.53% | ||

| No health conditions | Sleep Deprived (80) 84.2% | |

| Adequate sleep (188) 83.1% |

| Physical symptoms | Sleep duration | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | Sleep Deprived (24) 25.26% | 0.07 |

| Adequate sleep (45) 19.91% | ||

| Muscle pain | Sleep Deprived (15) 15.7% | |

| Adequate sleep (26) 11.5% | ||

| Abdominal Pain | Sleep Deprived (1) 1.05% | |

| Adequate sleep (8) 3.53% | ||

| None of the above | Sleep Deprived (35) 36.8% | |

| Adequate sleep (115) 50.88% | ||

| More than one physical symptom | Sleep Deprived (20) 21.05% | |

| Adequate sleep (32) 14.1% |

| Category | Sleep duration | Frequently | Sometimes/Infrequently | P - Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Duration and Forgetfulness | Sleep Deprived (95) | 24.2% (23) | 72 (75.7%) | 0.5 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 19.0% (43) | 183 (81 %) | ||

| Sleep duration and difficulty in concentrating during daily tasks |

Sleep deprived (95) | 28.4% (27) | 71.5% (68) | 0.04 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 16.8% (38) | 83.1% (188) | ||

| Irritability/ Annoyance | Sleep Deprived (95) | 29.47% (28) | 70.5% (67) | 0.277 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 23.4% (53) | 76.5% (173) | ||

| Decision Making | Sleep Deprived (95) |

8.7% (28) |

70.5% (67) | 0.211 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 20.8% (47) | 79.2% (179) |

| Category | Sleep duration | Frequently | Sometimes/Infrequently | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaging in risky behaviours | Sleep Deprived (95) |

5.3% (5) |

94.7% (90) | 0.539 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 7.1% (16) |

92.9% (210) | ||

| Feelings of Depression / Hopelessness |

Sleep Deprived (95) |

22.10% (21) | 77.89% (74) | 0.016 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 15.04% (34) | 84.95% (192) | ||

| Sleep Duration and Micro Sleep Episodes (Falling asleep while doing daily tasks) | Sleep Deprived (95) | 7.36% (7) | 92.63% (88) | 0.08 |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 4.86% (11) | 95.13% (215) |

|

Feelings of Anxiety/ Nervous/ On Edge |

Sleep duration | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | P- value |

| Sleep Deprived (95) |

7.4% (7) | 21.1% (20) |

44.2% (42) | 11.6% (11) | 15.8% (15) | 0.054 | |

| Adequate sleep (226) | 7.5% (17) | 14.2 %(32) | 37.2% (84) | 26.1% (59) | 15% (38) |

| Category | Sleep duration | Yes | No | I do not drive | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road Traffic Accident | Sleep Deprived (95) | 5.26% (5) | 66.3% (63) | 28.42% (27) | 0.64 |

| Adequate Sleep (226) | 3.53% (8) | 70.79% (160) | 25.66% (58) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).