Introduction

The origin of viruses remains one of the most intriguing and unresolved questions in evolutionary biology. Despite major advances in comparative genomics, structural virology, and metagenomics, there is still no consensus on whether viruses originated before or after the emergence of cellular life. Their profound dependence on host organisms for replication, combined with their immense genetic diversity and the absence of universally conserved genes, has led to the development of multiple origin models. These include the virus-first hypothesis, which posits that viruses predate cellular life; the escape (or “exogenisation”) hypothesis, suggesting that viruses emerged from mobile genetic elements that acquired the ability to move between cells; and the reduction (or degeneration) hypothesis, which sees viruses as the remnants of once-independent cellular organisms that gradually lost their autonomy.

Among these, the exogenisation and microbe-degeneration models continue to receive considerable attention and refinement, especially as new large DNA viruses blur the distinction between viruses and cellular organisms. The discovery of nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses (NCLDVs), such as mimiviruses and pandoraviruses, has revived interest in the idea that some viral lineages may have descended from ancestral cells that underwent genome reduction, shedding genes no longer needed in a host-dependent lifestyle (Legendre et al., 2021; Yutin et al., 2014). Experimental evidence shows that genome size and gene content in giant viruses can shrink under certain conditions, supporting the degeneration hypothesis (Boyer, 2011). At the same time, the existence of autonomous mobile genetic elements—such as plasmids, transposons, and retroelements—that share functional features with viruses has lent support to models suggesting that viruses evolved through exogenisation processes: the outward escape of genomic material from host cells, eventually forming infectious agents capable of intercellular transfer (Koonin et al., 2015; Feschotte & Gilbert, 2012).

These models are not mutually exclusive and may reflect different origins for different classes of viruses. For example, RNA viruses may have followed an entirely distinct trajectory from DNA viruses, and even within DNA viruses, distinct clades could have emerged from separate ancestral events. In this context, some recent theoretical work—particularly from authors such as Peer Terborg and Peter Borger—has proposed variations on these classical hypotheses. These perspectives suggest that the origin of viruses might be intimately tied to the functional regulation of mobile genetic elements within cellular genomes, and that these elements may have been exogenised under specific conditions, potentially as part of adaptive mechanisms. The microbe-degeneration theory, on the other hand, is often framed not only in terms of genome reduction but also as a process of functional de-specialization from symbiotic or parasitic ancestors.

This paper aims to evaluate the explanatory power and limitations of these two competing models—exogenisation and microbe-degeneration—within the context of current virological knowledge. By considering genomic, structural, and molecular evidence, we aim to assess how well each theory accounts for the key features of viral biology, including genome composition, replication strategies, and phylogenetic distribution. Special attention is given to how the role of transposable elements and endogenous viral elements may inform our understanding of viral origins. The frequent integration of viral sequences into host genomes, and their regulation via epigenetic mechanisms, highlights the highly dynamic relationships between viruses and their hosts (Filée, 2015; Chen et al., 2021). In doing so, we seek to clarify whether the virus–host relationship is best seen as the result of genetic escape, degenerative evolution, or a more complex interplay of both processes.

Established Theories on the Origin of Viruses

A variety of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the origin of viruses, with the three most widely discussed being the escape hypothesis (also called the exogenisation hypothesis), the reduction or degeneration hypothesis, and the virus-first hypothesis. Each model attempts to reconcile the unique biological features of viruses—such as their dependence on host cells for replication and their diverse genomic architectures—with comparative genomic and phylogenetic data.

Escape (Exogenisation) Hypothesis

The escape hypothesis posits that viruses originated from autonomous genetic elements—such as plasmids, transposons, or retrotransposons—that acquired the ability to exit the cell, encapsulate themselves in protein coats, and move between host cells. Over time, these mobile genetic elements would have evolved increasing levels of complexity, acquiring genes necessary for infection, replication, and evasion of host defenses. This model is supported by the existence of transposable elements that resemble viral genomes in structure and function, and by the well-documented capacity of viruses to capture host genes (Feschotte & Gilbert, 2012; Koonin & Dolja, 2013).

One of the major strengths of the exogenisation model lies in its ability to explain the mosaic nature of many viral genomes, which frequently contain host-derived genes and show signatures of recombination with other genetic elements. Additionally, the structural and functional similarities between some viral proteins and those involved in plasmid conjugation and transposition further support a common origin (Kazlauskas et al., 2019). Supporting this view, recent findings have shown that certain retroviruses share functional vulnerabilities with endogenous retroviral elements, as their activity can be effectively inhibited by the same reverse transcriptase-targeting drugs, such as zidovudine and efavirenz, suggesting a shared mechanistic basis and possibly a common origin from mobile genetic elements within the host genome (Schneider et al., 2021).

However, the escape hypothesis struggles to fully account for the origin of hallmark viral features such as capsid proteins and dedicated replication machinery, many of which lack close homologs in cellular life. The de novo emergence of such components remains speculative, and the phylogenetic disconnection of many viral hallmark genes from known cellular lineages limits the explanatory power of this model for certain virus groups (Yutin & Koonin, 2012; Forterre & Prangishvili, 2009). Nonetheless, the escape hypothesis is strongly supported by molecular genetic evidence, as illustrated by the following example.

The Origin of Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV)

RNA viruses contain compact yet highly functional genetic elements that enable them to replicate as molecular parasites. Typically, an RNA virus possesses only a limited number of genes. This raises a key question: where did these genes originate? The most parsimonious explanation is that RNA viruses escaped from genomic elements that already carried these genes, eliminating the need for their de novo origin. Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs)—recently reidentified as regulatory genetic elements—may represent the source of many retroviruses. These ancient genomic elements harbor gene architectures (gag, pol, env) virtually identical to those found in modern retroviruses, suggesting a direct lineage (Holmes, 2003).

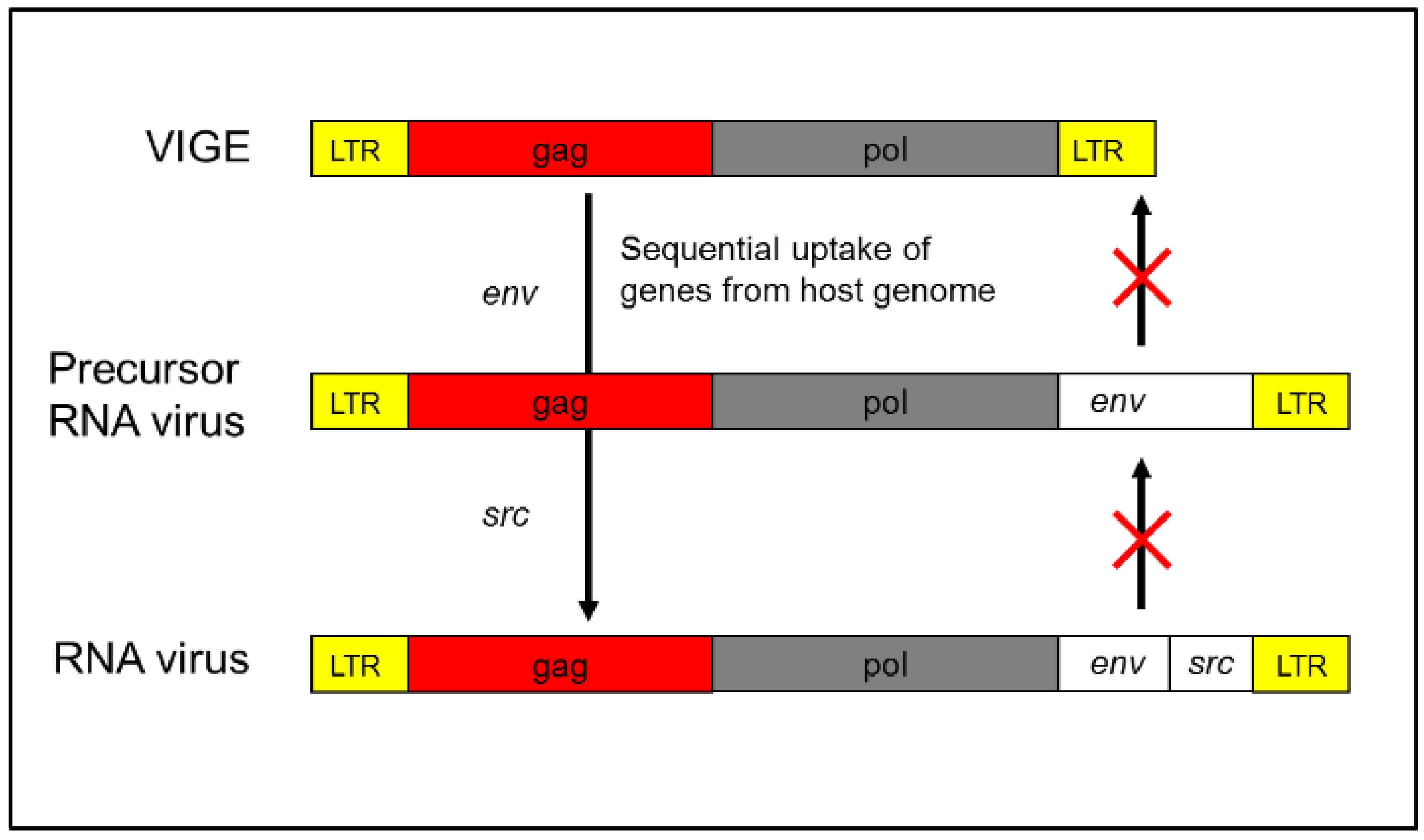

A compelling case is provided by Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV), an oncogenic retrovirus that harbors only four genes: gag, pol, env, and src. Flanking these coding regions are long terminal repeats (LTRs), which promote integration into the host genome and enhance viral replication. The gag, pol, and env genes are canonical retroviral genes and are frequently found in ERVs. The src gene, however, is of particular interest—it is a modified version of a host-derived src gene, originally encoding a tyrosine kinase involved in normal cell signaling. In RSV, this gene has been altered to function as a constitutive activator of cell proliferation, effectively converting it into an oncogene. Importantly, src is not essential for viral replication. RSV variants lacking src—retaining only gag, pol, and env—remain replication-competent but lack oncogenic potential (Vogt 2012). This strongly supports the view that the src gene was captured from the host genome. Given this, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the entire viral vector may have originated from host genetic material.

ERVs are particularly prone to acquiring host-derived sequences through mechanisms such as RNA polymerase II read-through transcription or incomplete excision events. Thus, many RNA viruses may have assembled from preexisting host sequences. For example, the outer envelope of the influenza virus is composed of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase—proteins with clear homologs in higher eukaryotes. Neuraminidase, in particular, plays a critical role in glycopeptide and oligosaccharide processing in humans. Mutations or deficiencies in this enzyme can lead to severe lysosomal storage disorders. Even so-called “orphan genes”—those with no known homologs in cellular life—are often found embedded within ERV loci in host genomes. This suggests that ERVs may serve as genetic reservoirs or intermediates in the origin of novel viral genes (Ueda et al., 2020).

These findings support the notion that RNA viruses likely originated through recombination events involving host genomic elements such as protein-coding genes, promoters, and enhancers—often mediated or facilitated by ERV activity. Occasionally, an “unfortunate” recombination event involving an ERV may produce a self-replicating molecular unit, marking the genesis of a novel viral particle. Once such a construct acquires the ability to re-enter host cells, it transitions into a fully infectious virus. It has long been recognized that bacteria can acquire advantageous traits from bacteriophages—viruses that integrate into the bacterial genome either transiently or permanently. In many cases, prophage genes are responsible for encoding major bacterial toxins. In such scenarios, viral genes confer selective advantages upon their bacterial hosts in specific environments. The emergence of such pathogenic viruses is thus best understood not as a purely linear descent, but as a dynamic process of genetic recombination and mosaic assembly, involving existing mobile elements such as plasmids, insertion sequences, and endogenous retroviruses. Rather than emerging de novo, many viruses appear to be recombinants of host-derived genetic modules, repurposed for parasitic replication.

Reduction (Degeneration) Hypothesis

The reduction hypothesis suggests that viruses originated from more complex, possibly cellular ancestors—such as parasitic or symbiotic microorganisms—that gradually lost genes no longer essential to a host-dependent lifestyle. This model is particularly supported by the discovery of giant viruses, such as mimiviruses and pandoraviruses, which possess large genomes encoding components typically associated with cellular life, including DNA repair, translation-related functions, and nucleotide metabolism (Legendre et al., 2014; Legendre et al., 2021; Yutin et al., 2014). These findings imply that such viruses may be remnants of once-free-living or parasitic cells that underwent reductive evolution (Koonin et al., 2018; Koonin et al., 2019).

Evidence for the Reduction Hypothesis

In 2003, the discovery of Mimivirus challenged conventional views on viral complexity. Mimivirus is an exceptionally large virus, approximately 750 nanometers in diameter, visible under light microscopy, and infects amoebae. Its genome, comprising 1.2 million base pairs and over 900 genes, rivals the size of some bacterial genomes (Raoult, 2004). Remarkably, Mimivirus encodes genes typically absent in viruses, such as those for tRNA synthetases—enzymes crucial for protein synthesis—and three types of topoisomerases (IA, IB, IIA) involved in DNA topology regulation during replication. These topoisomerase genes are homologous to those found in soil bacteria, suggesting a bacterial ancestry (Raoult, 2004). The presence of such genes implies that Mimivirus likely evolved from a free-living bacterium that progressively lost non-essential genes while adapting to an obligate parasitic lifestyle within amoebae (Claverie et al., 2009; Patil & Kondabagil, 2021)). This evidence strongly supports the reduction hypothesis, positing that certain viruses derive from degenerate cellular ancestors that gradually lost autonomy.

More recently, in 2025, researchers identified Sukunaarchaeum, a novel microorganism detected incidentally during the genomic analysis of the marine dinoflagellate Citharistes regius. Sukunaarchaeum possesses a remarkably small circular genome of only 238,000 base pairs encoding 189 genes, fewer than many viruses (Harada, 2025). Most genes facilitate self-replication, but the organism lacks key genes for energy metabolism and biosynthesis, indicating an obligate dependence on its host. This genomic minimalism, coupled with its virus-like lifestyle, suggests that Sukunaarchaeum is a degenerate archaeon undergoing reductive evolution, transitioning toward a virus-like existence (Harada, 2025).

Together, these findings from Mimivirus and Sukunaarchaeum reinforce the concept that viruses may originate from cellular organisms undergoing progressive gene loss and functional simplification. Rather than representing a primitive or early form of life, viruses might be the products of evolutionary regression from once free-living cells. This challenges traditional paradigms that view viruses solely as emergent biological entities and highlights their role as indicators of cellular degradation and genomic reduction. The reduction hypothesis effectively explains the presence of complex replication systems and large coding capacity in some viruses, aligning with the general evolutionary trend of genome reduction observed in many obligate intracellular parasites and symbionts. Moreover, experimental evidence has demonstrated that viral genomes can undergo rapid reduction when specific functions become redundant due to host dependence (PNAS, 2011). Nevertheless, the reduction model faces challenges as well. The hypothesized transitional forms between cellular organisms and modern viruses have not been clearly identified in extant life, and the loss of genes does not inherently explain the origin of unique viral features, such as capsid formation and highly efficient genome packaging systems. Furthermore, genome reduction is generally a process that optimizes existing parasitism rather than generating novel infectious mechanisms from scratch (Forterre, 2006; Claverie, 2020).

Virus-First Hypothesis

The virus-first hypothesis proposes that viruses predate cellular life and are remnants of a pre-cellular “RNA world” or other ancient replicator systems. In this model, viruses or virus-like genetic elements were already replicating independently in the primordial environment and later became obligate intracellular parasites following the emergence of the first cellular organisms (Koonin & Martin, 2005; Nasir & Caetano-Anollés, 2015).

This hypothesis offers a coherent framework for explaining why numerous viral genes—particularly those encoding capsid proteins and replication enzymes—lack detectable homologs in cellular genomes and appear to be uniquely restricted to the viral world. The structural conservation of viral capsids across highly divergent viral families, despite their lack of sequence similarity, may indicate that some viral components are deeply rooted in primordial biological systems (Abrescia et al., 2012; Krupovic & Koonin, 2017).

However, the virus-first model is also highly speculative, as all known viruses are obligate parasites that require host machinery for replication. No current virus is capable of independent existence or metabolism, making it difficult to infer how ancestral virus-like entities might have sustained themselves prior to the origin of cellular life. Moreover, the transition from hypothetical pre-cellular replicators to fully parasitic viruses remains not only poorly understood, but no plausible hypothesis has yet been formulated to account for how such a transition could have occurred (Moreira & López-García, 2009).

Evaluating the Hypotheses in Light of Empirical Data

Any credible theory of viral origin must account for a set of empirical observations derived from comparative genomics, structural biology, and metagenomics. Two competing models—exogenisation (escape) and microbe-degeneration (reduction)—differ in how well they explain such observations. Below I discuss several key data points and how each model fares, referencing recent literature.

Many viral proteins lack detectable cellular homologues. Comparative genomic analyses show that a large fraction of viral genes are “ORFans,” i.e., open reading frames with no discernible similarity to known cellular proteins; in prokaryotic viruses roughly 80 %, and in eukaryotic viruses around 65 %, fall into this category. This suggests a substantial amount of viral genetic novelty (Frontiers in Microbiology, 2023). Under the exogenisation model, this observation is challenging: while mobile genetic elements might supply some novel sequences, the de novo origin of completely novel protein folds (such as many capsid proteins or replication enzymes) remains difficult to explain completely. The degeneration hypothesis can explain loss of genes in formerly more complex genomes but still must account for the emergence of entirely novel structures (capsids etc.) that apparently do not derive from known cellular homologues (Multiple Origins of Viral Capsid Proteins, PMC, 2017; Viral Complexity, MDPI, 2020).

Large DNA viruses with large gene repertoires—so-called giant viruses—present another vital datum of huge diversity (Aherfi et al 2016; Schulz et al., 2020). Viruses such as Mimivirus and Pandoravirus have genomes larger than those of many bacteria (exceeding 1 Mbp), encoding hundreds of proteins including metabolic, translation-related and other auxiliary functions that are typically associated with cellular life (DNA Viruses: The Really Big Ones, PMC; Viral Complexity, MDPI, 2020). In the exogenisation framework, such viruses must have acquired many genes via gene capture from hosts or mobile elements; in contrast, the degeneration view holds that these viruses descend from more complex cellular ancestors that gradually lost genes but retained many formerly core cellular functions.

Conserved capsid architectures across divergent viral lineages provide important structural constraints. Studies of major capsid protein (CP) folds show that many viruses share capsid architectures, such as single or double “jelly-roll” folds, or HK97 fold, even when their amino acid sequence similarity is minimal or absent (Multiple Origins of Viral Capsid Proteins, PMC, 2017; A Structural Dendrogram of Actinobacteriophage Major Capsid Proteins, PMC, 2022). Under exogenisation, such conservation implies either very early emergence of these capsid folds, or frequent horizontal transfer; the degeneration hypothesis more naturally accommodates the retention of capsid features if the ancestor already possessed them and structural constraints maintain stability.

The absolute dependence of viruses on living host cells for replication is shared by both models: neither escape nor degeneration can deny this core feature. It remains problematic primarily for the virus-first hypothesis, which proposes an origin independent of fully developed cells. Both exogenisation and degeneration accept parasitism or dependency as a central feature, though they diverge in the source of the ancestral entities.

Finally, the diversity of RNA vs. DNA viruses must be addressed. RNA viruses tend to exhibit higher mutation rates, smaller genomes, and more rapid adaptive dynamics, whereas DNA viruses often have larger, more complex genomes, sometimes encoding auxiliary metabolic genes and more elaborate replication machinery (Genomes – PMC, large virus studies; Viral Complexity, MDPI, 2020). The exogenisation hypothesis might posit that pathogenic RNA viruses may be best explained as originating from mobile RNA elements, while DNA viruses may derive in large part through exogenisation of huge DNA elements or through degeneration of former cellular lineages, including bacteria. The degeneration theory can explain why some viruses retain DNA-based replication machinery and greater complexity, but must also explain how RNA viruses arose with their distinct replication strategies and why many lineages show no trace of a cellular ancestral signature.

Changing Perspective: Viruses as Major Players in Marine Ecosystems

Recent metagenomic and viromic studies have profoundly shifted our understanding of viral abundance, diversity, and functional importance in the world’s oceans. Perhaps most striking is the finding that viruses are not marginal components, but central actors in marine ecosystems—regulating microbial populations, influencing biogeochemical cycles, and carrying genes that shape host metabolism (Vila-Nistal et al., 2023).

One study in the Atlantic Ocean, sampling from the surface down to depths of over 4,000 meters, used viromics and quantitative methods to characterize RNA viruses. This work identified 2,481 putative RNA viral contigs (>500 bp) and 107 complete RNA viral genomes (>2.5 kb), many belonging to largely novel clades such as the Yangshan assemblage and Nodaviridae. These viruses were found to be highly endemic (only ~15% matched sequences in Tara Oceans metatranscriptomes outside their locality), with virus-like particle counts reaching ~10⁶ VLP/mL in surface and deep chlorophyll maximum zones. The study estimated that RNA viruses may contribute approximately 5.2 %–24.4 % of the total virio plankton biomass in those zones, with DNA viruses remaining numerically dominant (~10⁷ VLP/mL) (Zayed et al., 2022).

Complementing that, investigation into global deep-sea sediments (133 samples from three oceans) revealed 85,059 viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs), of which only 1.72 % corresponded to previously known virus types. Among these, 1,463 deep-sea RNA viruses with complete genomes were identified. The differentiation of viral communities was found to be driven primarily by deep-sea ecosystem type rather than geographic region. Further, virus-encoded metabolic genes—particularly involved in energy metabolism—played a major role in structuring community differences (Zhang et al., 2024).

Another seminal global RNA virome study, based on ~28 terabases of ocean RNA sequence data, proposed five novel RNA virus phyla—among them Taraviricota and Arctiviricota—which were widespread and relatively abundant. These additions imply that the current taxonomy of RNA viruses underestimates both diversity and ecological significance. The findings indicate that these new phyla occupy substantial ecological niches in oceanic waters, potentially acting as harmless fore-runners of potentially pathogenic RNA viruses (Zayed et al., 2022).

Together, these studies emphasize that any theory about the origin of viruses must account not only for their emergence (via exogenisation or degeneration, for example) but also for the fact that viruses are major biomass contributors in marine systems. They regularly influence nutrient and carbon cycling (e.g., the “viral shunt”), alter host metabolism via auxiliary metabolic genes, and drive host genetics through high diversity and frequent gene exchange. Understanding these ecological dimensions provides essential constraints and empirical data for evaluating origin hypotheses.

Understanding these ecological dimensions provides essential constraints and empirical data for evaluating origin hypotheses. Moreover, the recognition that viruses form an integral, quantitatively dominant, and functionally active component of marine ecosystems underscores the necessity of viewing viruses not merely as biological remnants or parasites, but as dynamic and essential agents within the biosphere, whose origin and evolution are deeply entwined with the history of life on Earth. Importantly, this vast oceanic virosphere also represents an immense reservoir of potential pathogenic viruses, which may become virulent through degenerative processes, or via genetic mechanisms such as recombination and the acquisition of virulence factors from other viruses or hosts.

Figure 1.

Origin of Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV). The Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) is hypothesized to have originated from an ancestral ERV through a two-step molecular genetic process. First, the acquisition of an envelope (env) gene enabled the element to form a functional virion, resembling members of the HERV-K family—human-specific endogenous retroviruses. Subsequently, a recombination event with host genomic material led to the incorporation of a portion of the SRC proto-oncogene, conferring oncogenic potential. Once these modifications were complete, the element emerged as an infectious retrovirus with the capacity for unregulated replication and horizontal transmission. This model highlights the dynamic role of ERVs as both genomic elements and potential reservoirs for the emergence of pathogenic retroviruses.

Figure 1.

Origin of Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV). The Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) is hypothesized to have originated from an ancestral ERV through a two-step molecular genetic process. First, the acquisition of an envelope (env) gene enabled the element to form a functional virion, resembling members of the HERV-K family—human-specific endogenous retroviruses. Subsequently, a recombination event with host genomic material led to the incorporation of a portion of the SRC proto-oncogene, conferring oncogenic potential. Once these modifications were complete, the element emerged as an infectious retrovirus with the capacity for unregulated replication and horizontal transmission. This model highlights the dynamic role of ERVs as both genomic elements and potential reservoirs for the emergence of pathogenic retroviruses.

References

- Abrescia, NGA; Bamford, DH; Grimes, JM; Stuart, DI. Structure unifies the viral universe. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012, 81, 795–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherfi, S; Colson, P; La Scola, B; Raoult, D. Giant viruses of amoebae: An update. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M; Azza, S; Barrassi, L; Klose, T; Campocasso, A; Pagnier, I; Fournous, G; Borg, A; Robert, C; Zhang, X; Desnues, C; Henrissat, B; Rossmann, MG; La Scola, B; Raoult, D. Mimivirus shows dramatic genome reduction after intraamoebal culture Erratum in. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108(25), 10296–10301, Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Oct 11;108(41):17234. PMID: 21646533; PMCID: PMC3121840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverie, JM; Abergel, C. Mimivirus and its virophage. Annu Rev Genet. 2009, 43, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverie, JM. Fundamental difficulties and false assumptions in identifying giant viruses and virophages from metagenomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117(11), 5743–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feschotte, C; Gilbert, C. Endogenous viruses: insights into viral evolution and impact on host biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2012, 13(4), 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P. The origin of viruses and their possible roles in major evolutionary transitions. Virus Res. 2006, 117(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P; Prangishvili, D. The origin of viruses. Res Microbiol. 2009, 160(7), 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, R; Nishimura, Y; Nomura, M; et al. A cellular entity retaining only its replicative core: Hidden archaeal lineage with an ultra-reduced genome-. bioRxiv (preprint). 2025. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.05.02.651781v1.full.

- Holmes, EC. Molecular clocks and the puzzle of RNA virus origins. J Virol 2003, 77(7), 3893–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskas, D; Varsani, A; Koonin, EV; Krupovic, M. Multiple origins of prokaryotic and eukaryotic single-stranded DNA viruses from bacterial and archaeal plasmids. Nat Commun. 2019, 10(1), 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, EV; Martin, W. On the origin of genomes and cells within inorganic compartments. Trends Genet. 2005, 21(12), 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, EV; Dolja, VV. A virocentric perspective on the evolution of life. Curr Opin Virol. 2013, 3(5), 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, EV; Dolja, VV; Krupovic, M. Origins and evolution of viruses of eukaryotes: The ultimate modularity. Virology 2015, 479–480, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, EV; Yutin, N. Multiple evolutionary origins of giant viruses. F1000Res 2018, 7, F1000 Faculty Rev–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koonin, EV; Yutin, N. The devolution hypothesis of viral evolution. Curr Opin Virol 2019, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupovic, M; Koonin, EV. Multiple origins of viral capsid proteins from cellular ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114(12), E2401–E2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, M; Bartoli, J; Shmakova, L; et al. Thirty-thousand-year-old distant relative of giant icosahedral DNA viruses with a pandoravirus morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111(11), 4274–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, M; Fabre, E; Poirot, O; et al. Origin and evolution of the giant Mimivirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118(7), e2025251118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D; López-García, P. Ten reasons to exclude viruses from the tree of life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009, 7(4), 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A; Caetano-Anollés, G. A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution. Sci Adv. 2015, 1(8), e1500527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S; Kondabagil, K. Coevolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis of Mimiviral Replication Machinery Suggest the Cellular Origin of Mimiviruses. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38(5), 2014–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raoult, D; Audic, S; Robert, C; et al. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science 2004, 306, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, MA; Buzdin, AA; Weber, A; Clavien, PA; Borger, P. Combination of Antiretroviral Drugs Zidovudine and Efavirenz Impairs Tumor Growths in a Mouse Model of Cancer. Viruses 2021, 13(12), 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schulz, F; Yutin, N; Ivanova, NN; et al. Giant virus diversity and host interactions through global metagenomics. Nature 2020, 578(7795), 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, MT; Kryukov, K; Mitsuhashi, S; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis reveals dynamic evolution of endogenous retroviruses that code for retroviral-like protein domains. Mobile DNA 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Nistal, M; Maestre-Carballa, L; Martinez-Hernández, F; Martinez-Garcia, M. Novel RNA viruses from the Atlantic Ocean: Ecogenomics, biogeography, and total virioplankton mass contribution from surface to the deep ocean. Environ Microbiol 2023, 25(12), 3151–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, PK. Retroviral oncogenes: a historical primer. Nature reviews. Cancer 2012, 12(9), 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yutin, N; Koonin, EV. Hidden evolutionary complexity of nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses of eukaryotes. Virol J 2012, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yutin, N; Wolf, YI; Koonin, EV. Origin of giant viruses from smaller DNA viruses not from a fourth domain of cellular life. Virology 2014, 466-467, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zayed, AA; Wainaina, JM; Dominguez-Huerta, G; et al. Cryptic and abundant marine viruses at the evolutionary origins of Earth’s RNA virome. Science 2022, 376(6589), 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X; Wan, H; Jin, M; Huang, L; Zhang, X. Environmental viromes reveal global virosphere of deep-sea sediment RNA viruses. J Adv Res. 2024, 56, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).