1. Introduction

The virus-first theory proposes that viruses predate cellular life, emerging as self-replicating genetic elements in the early Earth. This concept can be traced back to early 20th-century thinkers such as Leonard Troland and H.J. Muller, who suggested that primitive “genetic enzymes” might represent the earliest forms of life (Fry, 2006). Later, one of the founders of the modern synthesis, J.B.S. Haldane, speculated that life passed through a “virus stage” before the emergence of cells (Haldane, 1929; Tirard, 2017).

Although viruses have long been regarded as obligate intracellular parasites—therefore, biologically dependent and unlikely to precede cellular life (van Regenmortel, 2000)—recent advances in virology and evolutionary theory challenge this view (Nasir and Caetano-Anolles 2015). Viruses are increasingly seen not as degenerate cells, but as evolutionarily stable strategies of life (Koonin et al., 2015). De Farias et al., (2019) proposed that viruses do not require cells for replication; in evolutionary terms, they need access to a protein synthesis machinery capable of translating their proteins. Recently, it was proposed that the protoribosomes were likely present within ribonucleoprotein (RNP) condensates in the prebiotic soup, providing the infrastructure for replicating progenotes and early viral particles (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a).

This perspective reframes viruses not as parasites, but as integral evolutionary agents, central to the origin and diversification of life. The concept of “dark viral matter”—the largely uncharacterized virosphere—supports the idea that viruses are the most abundant biological entities on Earth, with profound ecological and evolutionary impact (Rohwer & Thurber, 2009; Waldron, 2015; Koonin, 2016). Viruses modulate microbial community structure, drive horizontal gene transfer, contribute to nutrient cycling, and influenced the emergence of key cellular innovations, such as the eukaryotic nucleus (Koonin & Martin, 2005) and the mammalian placenta through the domestication of endogenous retroviruses (Lavialle et al., 2013; Villareal, 2016).

Moreover, the discovery of giant viruses, such as Mimivirus, Pandoravirus and Tupanvirus, which harbor large genomes and even translation-associated genes, has blurred the boundaries between viruses and cells, lending support to the view that viral architecture has deep evolutionary roots (Claverie & Abergel, 2010; Legendre et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2019). Even the ICTV’s concept of the virocell—which emphasizes the metabolically active phase of viruses inside host cells—indirectly acknowledges the central role of viruses in cellular evolution (Forterre, 2013). Still, this model often retains a host-centric bias, interpreting viruses mainly as infection agents (Forterre and Raoult, 2017).

In contrast, we aim to propose a broader and more fundamental narrative: that viruses, particularly in the form of RNP-based particles, are direct descendants of the RNP world (Prosdocimi et al., 2023). In this framework, viruses are not peripheral anomalies, but core evolutionary agents that link prebiotic RNP condensates (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a) to the emergence of cellular life. Our goal in this work is to offer a theoretical model connecting the origin of viruses to the RNP-world theory (Di Giulio, 1997; Farias & Prosdocimi, 2022), to the evolution of progenotes (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2024), and ultimately to the formation of cellular architecture (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025b).

2. A Current View of the RNP-World

The ribonucleoprotein (RNP) world theory proposes that the earliest biological systems that allowed the emergence of the life phenomenon were assemblies of RNAs and peptides (Di Giulio, 1997; Matera, 2015; Farias & Prosdocimi, 2022). According to this model, while the RNAs played a central role in the early development of biological systems due to its informational and catalytic capacities under the RNA-world perspective, it is unlikely that they would have achieved the complexity required for life in the absence of a symbiosis with peptides (Prosdocimi et al., 2021). Peptides are much more versatile molecules, built as a chain of amino acids that are very different in their chemical and physical characteristics. This structural versatility makes peptide polymers capable to interact and bind other molecules in the primitive soup more efficiently than nucleic acids. Together, a world of ribonucleoproteins offers a remarkable explanatory power: while the RNAs maintain their role in storing information, the molecular evolutionary processes ended by selecting peptides as the most important molecules for molecular binding and catalysis (Hansma, 2017). This limited catalytical capacities of RNAs is a strong criticism to the idea that enzymes from basal metabolism were once ribozymes that have been further substituted by amino acid polymers, as proposed by some RNA-world advocates. The combined properties of nucleic acids and peptides make RNP complexes the strongest drivers of molecular evolution on the prebiotic Earth (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2019).

In this theoretical scenario, the biological system referred to as the First Universal Common Ancestor (FUCA) originated as an RNP-based system, on which basic translation mechanisms and a primitive form of the genetic code have first arisen (Prosdocimi et al., 2019; de Farias et al., 2021). Meanwhile the genetic code maturated, nearly random peptides functioned as constituents of RNP aggregates. FUCA represents the conceptual link between the RNA world and the peptide-rich metabolic networks theorized in hypercycle models (Eigen and Schuster, 1977; Orgel, 2004; Keller et al., 2014; 2016). While creating a biological code of information displacement between chemical polymers (i. e., the genetic code), FUCA populations allowed the emergence of the first peptide-coding genes: stretches of RNA that organized the order and quality of amino acids in a peptide. It is within this interface that the concept of chemical symbiosis takes shape: RNAs and peptides co-evolved in a mutually beneficial interaction that incrementally increased molecular complexity (Lanier et al., 2017; Vitas & Dobovišek, 2018; Prosdocimi et al., 2021).

As this symbiosis progressed, peptides began to contribute to RNA stability and functional expansion, and RNP systems emerged as central players in the early molecular repertoire of life (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2023).

Then, the most well-succeeded FUCA populations capable of primitive translation gave origin to more sophisticated RNP-based systems named progenotes: dynamic and membraneless RNP structures (Woese & Fox, 1997; de Farias et al., 2019). Some of those progenotes’ main roles were acting as coacervates, providing protected aqueous microenvironments (prebiotic refugia) that facilitated chemical reactions (Banani et al., 2017, Uversky 2024; Prosdocimi et al., 2022). With time, progenotes RNA-based genomes grew and developed increasingly elaborated genes capable of encoding more effective peptides (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2024a), which in turn facilitated the emergence of rudimentary metabolic circuits. This progression reinforces the theory that RNPs were the first supramolecular systems capable to orchestrate vital biochemical functions, including information replication, enzymatic activity, and primitive metabolism (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2023). Those populations of progenotes grew by mutation and by concatenation and mixing of their informational content. Together, molecular natural selection favored the progenotes populations capable of encoding peptides that bound to molecules in the prebiotic soup and accelerate their cycling (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2022). Little by little, spontaneous molecular cycles already happening in the milieu (Keller et al., 2014; 2016) were incorporated into biology as randomly formed peptides happened to bind some of these molecules and accelerate their transformation. Any encoded peptide capable of binding nucleotides and amino acids to facilitate and rise their production would be favored in that context. A strong piece of evidence supporting this view comes from the evolutionary history of ribosomes. Several authors suggest that the ribosome, an RNP complex, emerged very early in the history of life on our planet, possibly being the first structure to become established in forming biological systems (Belousoff et al., 2010, de Farias et al., 2014, Bowman et al., 2015)

Thus, the route of complexification was in course and different populations of progenotes possibly maturated different biochemical pathways until reaching about 300 specific genes and allowing the emergence of cellular life under the perspective of a Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) (Weiss et al., 2016; Moody et al., 2024).

3. The Emergence of Compartmentalization

We need to go back in time a little to understand how those progenotes could exist without any sort of membrane. At the molecular scale, it has been warmly discussed in the literature the fact that pre-cellular forms of compartmentalization could be acquired by some sort of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) (Patel et al., 2017; Poudyal et al., 2018; Smokers et al., 2024; Ruzov & Ermakov, 2025; Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a). LLPS are known as agglomerates formed mainly by RNP particles that provide some sort of compartmentalization inside cells, creating aggregates of organic molecules in aqueous substrates. Those protocompartments were primarily composed by intrinsically disordered peptides bound to RNAs, which formed dynamic, multivalent interactions capable that constitute flexible and responsive biomolecular condensates (Wright & Dyson, 2015; Brangwynne et al., 2015; Uversky, 2017; Feng et al., 2021; Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a). Current RNA-binding proteins such as FUS, TDP-43, and hnRNPA1 exemplify this behavior, assembling reversible, phase-separated structures crucial for intracellular organization (Banani et al., 2017; Hyman & Simons, 2012). In early evolution, similar interactions between RNAs and disordered peptides likely enabled the spontaneous formation of protocondensates under prebiotic conditions, offering a membraneless route to molecular compartmentalization (Franzmann & Alberti, 2019; Banani et al., 2017; Uversky, 2024). These droplets could concentrate biomolecules, accelerate reactions, and provide protection from environmental degradation — essential functions for the emergence of life (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a). Corroborating those ideas, experiments recreating the oldest portion of the ribosome demonstrated the capability of this molecule in forming peptide bonds (Bose et al., 2022).

4. The Emergence of Viruses from Progenotes

The initial level of compartmentalization in biological systems therefore involved LLPS-like systems operating by RNPs within the primordial soup, effectively sequestering nucleic acids and their building blocks, together with other ions ans inorganic molecules necessary for primitive metabolism. Once this first level of aqueous separation by LLPS-based coacervates was stable and well-established, the inherent process of modification by mutation and selection continued to happen. To understand the next stage along the evolution of biological compartmentalization, we must search for the simplest form of compartments found today in biological systems. Membranes are highly complex structures made of long hydrocarbon chains (lipids), a sort of molecule that is still poorly related with the RNPs that sparkled the life phenomenon (Farias and Prosdocimi, 2022). If we aim to praise for logic and coherence, we need to look for some encapsulation mechanism made only by peptides or RNPs.

4.1. The simplest form of biological encapsulation: single-protein capsids

The simplest forms of biological encapsulation known today are found in some viral families, including Leviviridae, Tombusviridae, and Nodaviridae. Those viruses are capable to produce capsids composed of slight variations of a protein encoded by a single gene product. Some of them are aided by the presence of ions putatively available in the primordial soup (Persson et al., 2008). These capsids typically assemble into icosahedral structures, creating sophisticated microenvironments capable of encapsulating and protecting the viral chromatin.

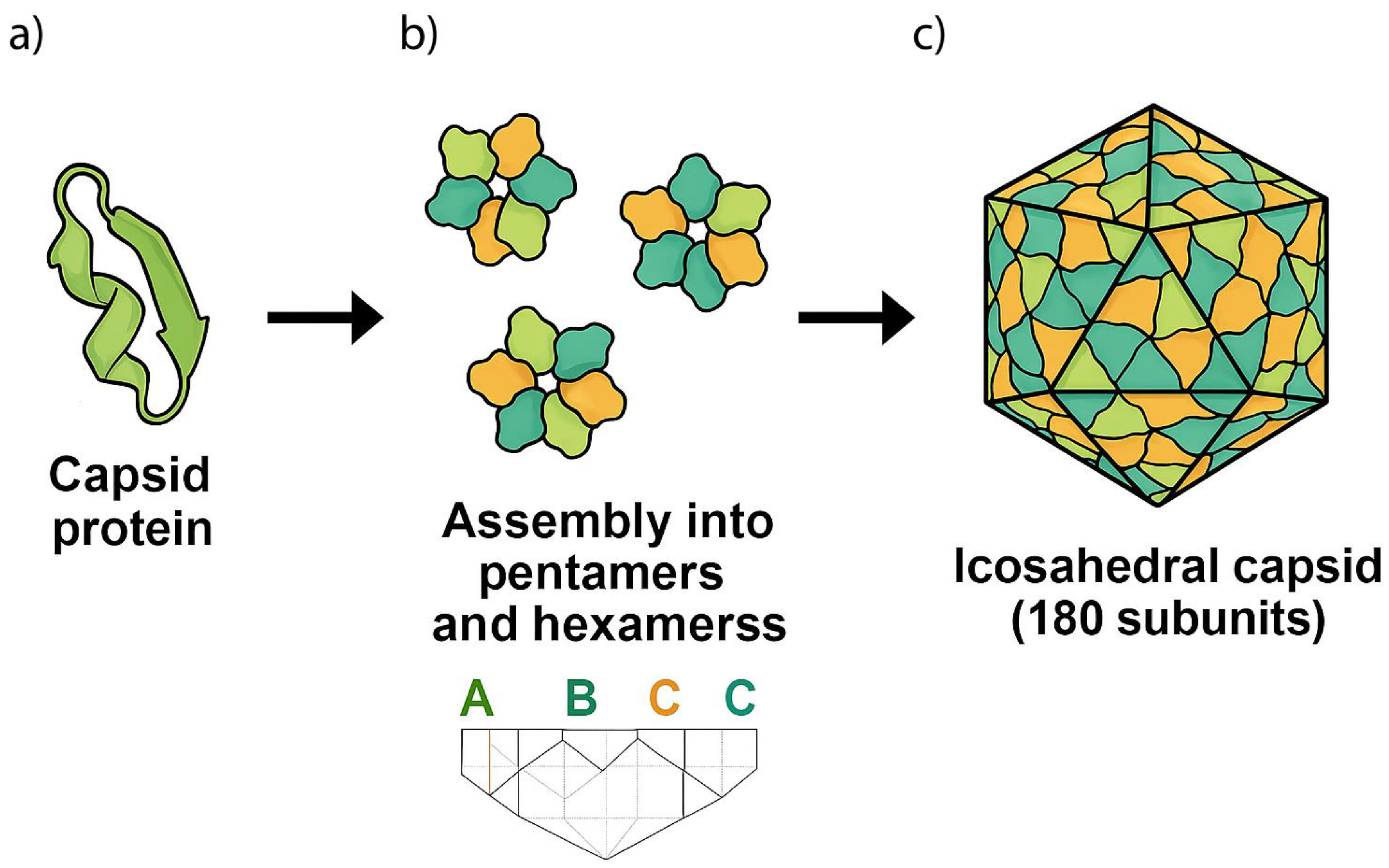

In the Leviviridae family, the bacteriophage MS2’s capsid is constructed from 180 copies of a single capsid protein (CP) with 14 kDa in size. These proteins arrange into an icosahedral structure with T=3 symmetry, forming 60 quasi-symmetric AB-dimers and 30 symmetric CC′-dimers. The A and C subunits are positioned around the three-fold axes, while the B subunits are located around the five-fold axes of the icosahedron. The CPs exhibit a unique fold distinct from the classic jellyroll motif observed in many other viral capsid proteins. During assembly, specific RNA sequences interact with CP dimers, facilitating the precise formation and stabilization of the capsid structure (Aksyuk and Rossmann, 2011).

In the Tombusviridae family, viruses such as the Tomato bushy stunt virus have capsids with approximately 32–35 nm in diameter, consisting of 180 identical CP subunits. These subunits also adopt the three conformational states labeled A, B, and C, achieving a T=3 icosahedral symmetry. Each CP subunit features a jellyroll β-barrel structure, comprising of two antiparallel β-sheets that create a stable, compact fold. The assembly involves intricate protein-protein interactions, where the N-terminal regions of the CPs contribute to the formation of the inner surface of the capsid, while the C-terminal regions participate in external contacts, ensuring structural integrity.

Within the Nodaviridae family, exemplified by the Black beetle virus, the capsid is also formed by 180 copies of the capsid protein alpha, which self-assemble into an icosahedral procapsid measuring about 30 nm in diameter. Again, each capsid protein adopts a core jellyroll topology, forming a face-to-face β-sandwich with two pairs of antiparallel β-sheets. During assembly, the capsid protein alpha undergoes a self-catalyzed cleavage, resulting in proteins beta and gamma, which are essential for the structural maturation of the capsid. This cleavage facilitates the stabilization of the capsid structure and is crucial for the infectivity of the virus (Chen et al, 2015).

Such assembly of viral capsids from 180 similar protein subunits into an icosahedral structure follows a well-defined geometric and structural principles (Caspar and Klug, 1962). Although an initial assumption might suggest that each of the 20 triangular faces is formed by exactly 9 proteins, this is not how the structure assembles. Instead, each face contributes with parts of different hexamers and pentamers, leading to the seamless icosahedral arrangement. Each triangular facet is a shared region where adjacent hexamers and pentamers interlock, forming a continuous network across the entire capsid. In the T=3 icosahedral symmetry, the 180 proteins are arranged in 60 asymmetric units, each containing those three subunits in different conformations (often labeled as A, B, and C). These proteins do not simply form 9-membered clusters on each triangular face but rather arrange into pentamers and hexamers that tessellate across the capsid surface to ensure a robust and energy-efficient assembly. Each triangular face of the icosahedron contains a mix of hexameric and pentameric clusters of proteins. The 12 vertices of the icosahedron are occupied by pentamers, each composed of 5 capsid proteins, while the triangular faces between them contain hexamers, each consisting of 6 proteins. Since an icosahedron has 12 vertices and 20 faces, the proteins distribute as follows: (i) 12 pentamers: 12 × 5 = 60 proteins; and (ii) 20 hexamers: 20 × 6 = 120 proteins; totaling 180 proteins. Each protein subunit is folded into a jellyroll β-barrel structure, which allows for stable lateral contact with neighboring proteins. The A, B, and C conformers exhibit slight variations in their orientation, allowing them to interact flexibly within hexameric and pentameric arrangements. The N-terminal arms of the proteins often engage in electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions, stabilizing the pentameric and hexameric contacts.

Figure 1 summarizes the current proposal. Additionally, some viruses encode auxiliary scaffolding proteins that temporarily guide this self-assembly, ensuring the proper curvature and spacing.

In summary, these viral families employ a highly efficient strategy in which multiple copies of a single capsid protein self-assemble into an icosahedral structure, achieving maximal stability with minimal genetic and energetic investment. Although seemingly intricate, this architecture represents the simplest known encapsulating system in biological systems, relying on fundamental principles of symmetry, self-organization, and cooperative protein-protein interactions (Caspar & Klug, 1962). The specific folding patterns and binding interfaces of these capsid proteins are crucial not only for structural integrity but also for the encapsulation and protection of nucleic acids, a feature that could have provided a significant evolutionary advantage in prebiotic systems. Also, it is known that viruses presenting icosahedric capsids and membranes can infect hosts from all life domains (Huiskonen & Butcher, 2007).

4.2. Simplicity and connection with RNP-world ideas

Considering the minimalistic yet highly effective nature of these viral capsids, we propose that similar self-assembling protein structures could have played a pivotal role in the early stages of biological evolution. In a pre-cellular world, capsid-like protein assemblies functioned as primordial protective enclosures for the genetic material, shielding them from degradation while facilitating molecular interactions necessary for early replication and metabolic-like processes (Forterre & Prangishvili, 2009; Krupovic & Koonin, 2017). An intriguing question would be why those forms of encapsulation did not acquire the ancestral ribosomes into them. It is plausible that the structural and physicochemical constraints of peptide-based capsids were incompatible with the spatial and functional requirements of ribosomes, possibly due to limited internal volume or the absence of a conducive microenvironment for translation. Although we cannot yet answer this question, this is the reason why cells were so highly successful when they emerged, as they could also contain those highly relevant complexes for peptide synthesis. In any case, the origin of capsids made of single peptides highlight the Haldane’s idea that viruses or virus-like systems were central to the evolution of life, providing early forms of genetic exchange and mobility across diverse microenvironments (Nasir & Caetano-Anollés, 2015).

Additionally, the self-assembly properties of icosahedral capsids suggest that such structures could have spontaneously emerged under prebiotic conditions, driven by similar thermodynamic and kinetic principles that govern modern viral assembly (Perlmutter & Hagan, 2015). The presence of symmetrical capsids in extant viruses across all domains of life further supports the notion that this strategy is deeply rooted in evolutionary history, potentially preceding cells (Koonin et al., 2006; Harish et al., 2016). In this context, viruses emerged as part of the community of progenotes that acquired a certain degree of compartmentalization without incorporating the translator progenotes necessary for the synthesis of their proteins. The absence of a protoribosome and the limited autonomy of those systems must have established selective pressure for the maintenance of intense interaction with other constituents of the progenote community. From this interaction, the relationship between viruses and cells may have emerged (de Farias et al., 2019).

5. A Brief Approach of Virus to Cell Transition

Over time, some progenote populations capable of producing simple self-assembling capsids began to increase the structural and functional complexity of those coats. This occurred through (ii) the progressive incorporation of additional proteins in the capsids-like structures, some of which were co-opted to serve specific roles such as molecular channels, environmental sensors (receptors), and binding interfaces for molecules. These functional enhancements allowed viral-like particles to interact more effectively with their surroundings and to regulate the transport of molecules across their boundaries. Eventually, (iii) the emergence and recruitment of peptides containing lipid-binding domains enabled the anchoring and organization of lipid molecules on the capsid surface (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025b). Emerging in some progenote populations, this interaction likely facilitated the transition from purely proteinaceous coats to hybrid proteolipidic structures, resembling modern cell membranes. These early membranes not only increased compartmentalization efficiency but also laid the foundation for the emergence of protocells, providing the physical and chemical boundary conditions necessary for the development of cellular metabolism, signaling, and replication control. And finally achieving a higher degree of autonomy and vertical inheritance. It is important to highlight that the autonomy observed in this part of the pre-cellular progenote populations occurred due to the incorporation of the ribosome into its constitution, thus differing from the other part of the progenote community that did not incorporate the ribosome and established viral lineages.

Contextualizing the emergence of proteolipidic membranes under the history of LUCA give us new insights. The most successful progenotes paved the way to the emergence of LUCA: the ancestor of the two basal cellular lineages (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2024). It is interesting to note that, while most basal pathways show homology between Archaea and Bacteria, at least in their central points, both (a) DNA biosynthesis and (b) lipid biosynthesis do not. This means that a completely different set of enzymes is responsible do make either DNA or lipids in Bacteria and Archaea (de Farias et al., 2021). One interpretation of this fact is that those two pathways were the last ones along the evolution of life and were acquired independently by each prokaryotic group (Sojo et al., 2014; Da Cunha et al., 2017; Di Giulio 2011, 2021, 2022). Membrane biogenesis therefore putatively arose two times in the evolution of life, when lipid-binding peptides were embedded into protein protocapsids in (i) Bacteria and (ii) Archaea (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025b). This fact highlights a broader evolutionary trend in which metabolic innovations emerge through stepwise modifications of pre-existing protein functions, rather than abrupt, de novo invention of entirely new molecular machinery (Peretó, 2012). The current stepwise explanation for viral-capsid evolution and the emergence of proteolipidic membranes provides logical, gradualistic and coherent view to solve this molecular puzzle.

6. Discussion

While the “Virus-First” theory has gained renewed attention as an alternative to cell-centered models of the origin of life, the terminology itself warrants scrutiny. The notion of “first” suggests a primacy of viruses over all other biological systems yet fails to capture the complex evolutionary continuum between pre-biotic chemistry and cellular life. In the model proposed here, viruses do not precede all forms of biological systems but rather emerged as a crucial step following the formation of RNP-based progenotes and intermediating the rise of cells. These progenotes, composed of naked RNPs compartmentalized in coacervates made on their same constitution, represent a primitive form of molecular self-organization rooted in prebiotic chemistry and consistent with RNP-world scenarios (Farias & Prosdocimi, 2022; Di Giulio, 1997). Those progenote systems were capable of genetic encoding and translation when in symbiosis with other progenotes harboring translator systems. Thus, while we argue that viruses predate cells, been a necessary step to its emergence, it must be clear that they do not predate all biological systems. Instead, we argue that viruses emerged as a transitional strategy: encapsulated RNP systems optimized for genome protection, environmental mobility, and interaction with primitive translational machinery (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a; Koonin et al., 2006). Consequently, the “Virus-First” label can be misleading if interpreted literally.

Our argumentation focuses in the emergence of capsid-like structures in primordial conditions, evidencing this as crucial step in the early transition from nearly disordered prebiotic chemistry to the structured complexity of biological systems. The widespread conservation of simple capsid structures across diverse viral lineages suggests that some of them should not be understood as molecular innovations but rather the maintenance of ancient molecular architectures (Krupovic & Koonin, 2017; Koonin et al., 2006).

This perspective challenges the traditional view of viruses as cellular parasites, instead positioning them as molecular systems that rely on other ribosome-containing systems for replication (de Farias et al., 2019). In evolutionary terms, the idea that viruses are not strict cellular infectants, but rather ribosome-dependent RNP systems indicates that their existence was deeply intertwined with the emergence of translation-capable biological systems (Forterre & Prangishvili, 2009). In prebiotic terms, encapsulated genomes would have needed to meet progenotes containing the rudimentary translational machinery (FUCA-like) to enable their propagation, a scenario that aligns with theories proposing a co-evolutionary relationship between early genetic replicators and primitive translation systems (Prosdocimi et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the encapsulation of genetic material within proteinaceous capsids conferred significant selective advantages by promoting protection and endurance in highly fluctuating environmental conditions (Dyson, 1982; Perlmutter & Hagan, 2015). This protection increased the persistence and evolutionary potential of early capsid-containing progenotes and allowed for horizontal gene transfer between those systems (Koonin, 2016). Notably, the ability of capsids to transport genetic material across different microenvironments can be seen as a precursor to modern viral infection mechanisms and gene transfer strategies, reinforcing the idea that viruses also played this fundamental role in the emergence of complex biological systems (Nasir & Caetano-Anollés, 2015; Forterre, 2010; Prosdocimi et al., 2023).

The following significant step in the evolution of biological compartmentalization was the emergence of cells. This happened after the success of some capsid-containing progenotes in a moment on which different populations have already been in place and evolved other peptides capable to bind their capsids. At some point, some capsid peptides would gain lipid-binding domains, starting to recruit lipids from the milieu, eventually producing membranes. This idea is corroborated by the fact that cell membranes are not lipidic, but proteolipidic (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025b). The peptide parts of cellular membranes are therefore root in this ancient mechanism.

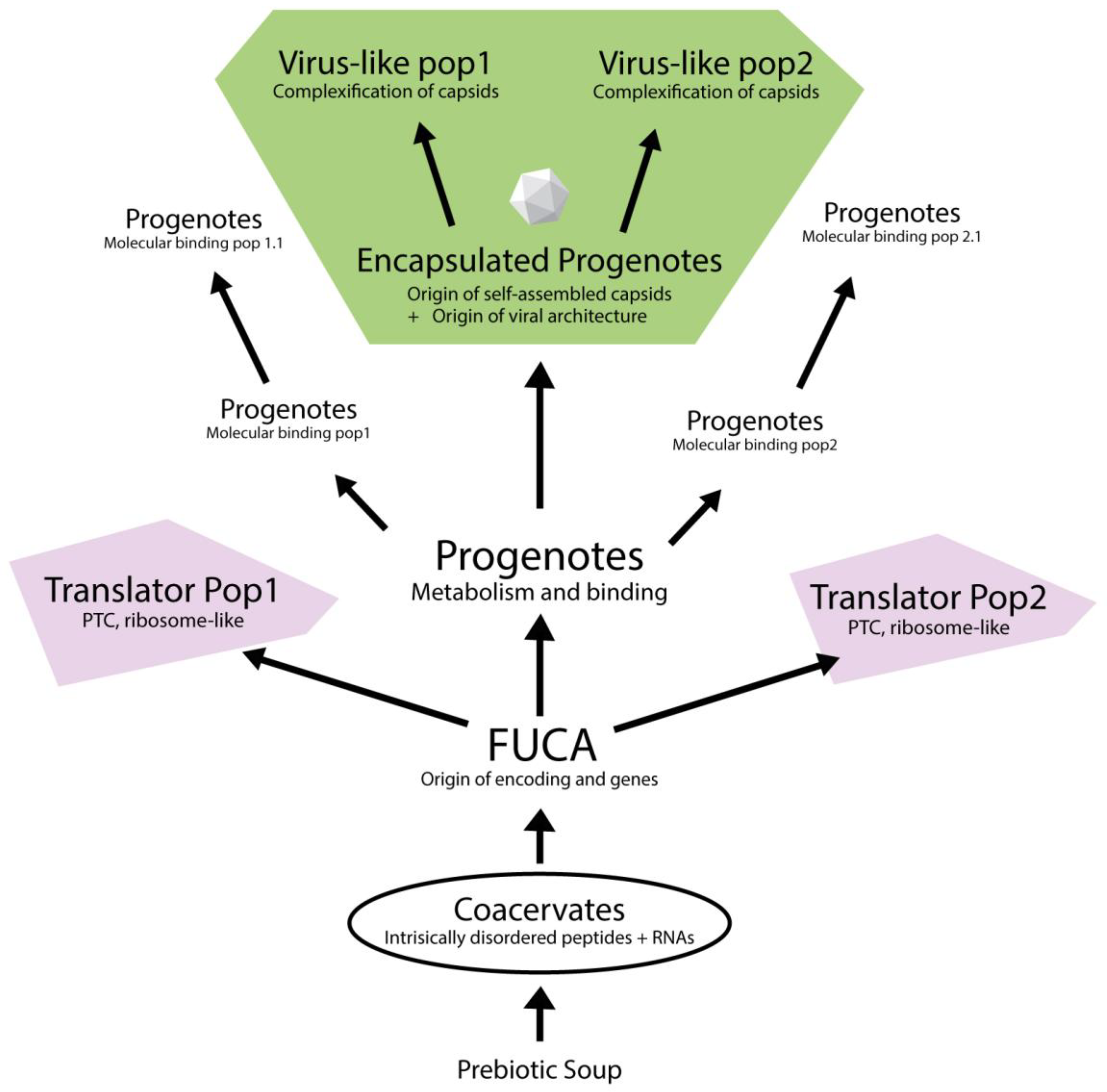

To summarize this model, we provide an illustration with the proposed evolutionary trajectory from prebiotic chemistry to the emergence of virus-like particles, grounded in the RNP-world framework (

Figure 2). Starting from coacervate-based systems composed of intrinsically disordered peptides and RNAs (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a), the model proposes the origin of FUCA as the point where primitive genetic encoding and peptide synthesis mechanisms first emerged (Prosdocimi et al., 2019). FUCA then diversified into distinct progenote populations, both translators and populations with distinct molecular binding abilities (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2022). Some of these progenotes evolved self-assembling capsid proteins, resulting in encapsulated forms that would later give rise to virus-like entities through structural complexification. Altogether, this scenario emphasizes a modular and stepwise progression in which encapsulated RNP systems and translation machinery co-evolved in separate but interacting populations, eventually converging toward the emergence of cellular complexity.

While the virocell concept has been an important step in redefining viruses as dynamic and metabolically active entities during their intracellular phase (Forterre, 2013), it remains conceptually anchored in a cell-first paradigm. The theory postulates that viruses acquire biological activity only within host cells, implicitly assuming that viruses arose from pre-existing cellular life. While this model effectively reframes viruses as agents of genetic innovation and ecological interactions, it does not account for their potential origins in prebiotic chemistry. In particular, it does not engage with current molecular evolution theories based on the RNP-world theory, which propose that life emerged gradually from self-organizing RNP condensates before the advent of cellular membranes (Farias & Prosdocimi, 2022; Smokers et al., 2024). In contrast, our model starts from a bottom-up framework, grounded in biophysics and chemical evolution. We propose that viruses, or virus-like entities, evolved as early ribosome-dependent RNP systems in a world where translation-capable progenotes already existed but lacked membranes, being compartmentalized in RNP aggregates (coacervates) (Prosdocimi & Farias, 2025a). At some point they have acquired a self-folding protein capable to box together with their copies. This molecular innovation allowed for a gradual and chemically plausible transition from progenotes to viral architecture. While we acknowledge that some modern viruses indeed evolved through reductive processes from cells—as posited by the virocell model—this scenario cannot explain the first appearance of capsid-based compartmentalization, nor does it address the origin of cellular membranes. The viral architecture is paraphyletic, and it is an evolutionarily stable strategy recurrently found by evolving biological systems. Plus, the current proposal opens interestingly a new venue in virus taxonomy in distinguishing (a) viral architectures and clades originated straight from progenotes, and (a’) the ones originated by simplification of cellular structures.

The current proposal supports the idea that the first biological systems did not arise in isolation but emerged within a dynamic network of interacting molecular entities, where virus-like particles played a central role as mediators of genetic exchange and evolutionary experimentation. The existence of viral systems before the advent of membrane-bound cells helps explain the deep structural and functional relationships between viral and cellular proteins, as well as the long-term persistence of viral lineages throughout evolutionary history (Iranzo et al., 2016; Koonin et al., 2021). Therefore, the study of ancient viral structures not only informs our understanding of early biological organization but also challenges conventional paradigms regarding the origin of life and the role of viruses in shaping the evolutionary landscape (Prosdocimi et al., 2023).

In conclusion, we hope to have (i) honored Haldane’s early proposition of a “virus stage” in the history of life, (ii) presented a coherent, gradualist scenario linking prebiotic chemistry to the emergence of virus and cells, and (iii) provided a contribution to the ongoing Virus-First debate.

7. Conclusions

Here we propose that the simplest viral capsids known today—formed by 180 copies of a single gene product—likely emerged within a population of progenotes in the RNP-world. These self-assembling capsid structures provided early encapsulation strategies for RNP-based systems. Over evolutionary time, some of these progenote systems increased in complexity through the incorporation of additional proteins co-opted to function as channels, receptors, and molecular binders. Eventually, the integration of peptides with lipid-binding domains into some populations presenting capsid-like structures enabled the formation of proteolipidic membranes, giving rise to cell-like entities. This transition also allowed the internalization of coacervate-like cytoplasmic elements and the recruitment of translational progenotes, such as protoribosomes, into a stable cellular framework. Altogether, this study presents a coherent theoretical model that bridges the Virus-First and RNP-world hypotheses, while also providing a plausible pathway for the origin of cellular membranes from primitive protein-based encapsulation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, FP and STF; investigation, FP and STF; writing—original draft preparation, FP; writing—review and editing, FP and STF; project administration, FP and STF.; funding acquisition, FP and STF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for providing research productivity fellowships for FP (CNE E-26/200.940/2022 and 306346/2022-2) and STF (313844/2021-6).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 3.5 and 4.0 for the purposes of revising text and language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aksyuk, A.A.; Rossmann, M.G. Bacteriophage Assembly. Viruses 2011, 3, 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousoff, M.J.; Davidovich, C.; Zimmerman, E.; Caspi, Y.; Wekselman, I.; Rozenszajn, L.; Shapira, T.; Sade-Falk, O.; Taha, L.; Bashan, A.; et al. Ancient machinery embedded in the contemporary ribosome. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, T.; Fridkin, G.; Davidovich, C.; Krupkin, M.; Dinger, N.; Falkovich, A.H.; Peleg, Y.; Agmon, I.; Bashan, A.; Yonath, A. Origin of life: protoribosome forms peptide bonds and links RNA and protein dominated worlds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.C.; Hud, N.V.; Williams, L.D. The Ribosome Challenge to the RNA World. J. Mol. Evol. 2015, 80, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, C.P.; Tompa, P.; Pappu, R.V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspar, D.L.D.; Klug, A. Physical Principles in the Construction of Regular Viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1962, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-C.; Yoshimura, M.; Guan, H.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Misumi, Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Chuankhayan, P.; Nakagawa, A.; Chan, S.I.; Tsukihara, T.; et al. Crystal Structures of a Piscine Betanodavirus: Mechanisms of Capsid Assembly and Viral Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005203–e1005203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverie, J.-M.; Abergel, C. Mimivirus: the emerging paradox of quasi-autonomous viruses. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, V.; Gaia, M.; Gadelle, D.; Nasir, A.; Forterre, P. Lokiarchaea are close relatives of Euryarchaeota, not bridging the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. PLOS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; Rãªgo, T.G.D.; Josã©, M.V. Evolution of transfer RNA and the origin of the translation system. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Farias, S.T.; Jheeta, S.; Prosdocimi, F. Viruses as a survival strategy in the armory of life. Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2019, 41, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Farias, S.T.; Jose, M.V.; Prosdocimi, F. Is it possible that cells have had more than one origin? Biosystems 2021, 202, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. On the RNA World: Evidence in Favor of an Early Ribonucleopeptide World. J. Mol. Evol. 1997, 45, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) and the Ancestors of Archaea and Bacteria were Progenotes. J. Mol. Evol. 2010, 72, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The late appearance of DNA, the nature of the LUCA and ancestors of the domains of life. Biosystems 2021, 202, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giulio, M. The origins of the cell membrane, the progenote, and the universal ancestor (LUCA). Biosystems 2022, 222, 104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.J. A model for the origin of life. J. Mol. Evol. 1982, 18, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigen, M.; Schuster, P. A principle of natural self-organization. Sci. Nat. 1977, 64, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias, S.T.; Prosdocimi, F. RNP-world: The ultimate essence of life is a ribonucleoprotein process. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2022, 45, e20220127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Jia, B.; Zhang, M. Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation in Biology: Specific Stoichiometric Molecular Interactions vs Promiscuous Interactions Mediated by Disordered Sequences. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 2397–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forterre, P. The virocell concept and environmental microbiology. ISME J. 2012, 7, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P. (2010). Defining life: the virus viewpoint. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres, 41(4), 367–372.

- Forterre, P.; Prangishvili, D. The Great Billion-year War between Ribosome- and Capsid-encoding Organisms (Cells and Viruses) as the Major Source of Evolutionary Novelties. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2009, 1178, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forterre, P.; Raoult, D. The transformation of a bacterium into a nucleated virocell reminds the viral eukaryogenesis hypothesis. . 2017, 21, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann, T.M.; Alberti, S. Protein Phase Separation as a Stress Survival Strategy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a034058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, I. The origins of research into the origins of life. Endeavour 2006, 30, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, J. B. S. (1929). The origin of life. Rationalist Annual, 148, 3–10.

- Hansma, H.G. Better than Membranes at the Origin of Life? Life 2017, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, A.; Abroi, A.; Gough, J.; Kurland, C. Did Viruses Evolve As a Distinct Supergroup from Common Ancestors of Cells? Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 2474–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huiskonen, J.T.; Butcher, S.J. Membrane-containing viruses with icosahedrally symmetric capsids. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, A.A.; Simons, K. Beyond Oil and Water--Phase Transitions in Cells. Science 2012, 337, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, J.; Krupovic, M.; Koonin, E.V. The Double-Stranded DNA Virosphere as a Modular Hierarchical Network of Gene Sharing. mBio 2016, 7, e00978–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Keller, M.; Turchyn, A.V.; Ralser, M. Non-enzymatic glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway-like reactions in a plausible Archean ocean. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014, 10, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.A.; Zylstra, A.; Castro, C.; Turchyn, A.V.; Griffin, J.L.; Ralser, M. Conditional iron and pH-dependent activity of a non-enzymatic glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V. Viruses and mobile elements as drivers of evolutionary transitions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Martin, W. On the origin of genomes and cells within inorganic compartments. Trends Genet. 2005, 21, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Dolja, V.V.; Krupovic, M. Origins and evolution of viruses of eukaryotes: The ultimate modularity. Virology 2015, 479-480, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Dolja, V.V.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H. Viruses Defined by the Position of the Virosphere within the Replicator Space. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Senkevich, T.G.; Dolja, V.V. The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells. Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 29–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupovic, M.; Koonin, E.V. Multiple origins of viral capsid proteins from cellular ancestors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2401–E2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, K.A.; Petrov, A.S.; Williams, L.D. The Central Symbiosis of Molecular Biology: Molecules in Mutualism. J. Mol. Evol. 2017, 85, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavialle, C.; Cornelis, G.; Dupressoir, A.; Esnault, C.; Heidmann, O.; Vernochet, C.; Heidmann, T. Paleovirology of ‘ syncytins ’, retroviral env genes exapted for a role in placentation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legendre, M.; Fabre, E.; Poirot, O.; Jeudy, S.; Lartigue, A.; Alempic, J.-M.; Beucher, L.; Philippe, N.; Bertaux, L.; Christo-Foroux, E.; et al. Diversity and evolution of the emerging Pandoraviridae family. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matera, A.G. Twenty years of RNA: reflections from the RNP world. RNA 2015, 21, 690–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, E.R.R.; Álvarez-Carretero, S.; Mahendrarajah, T.A.; Clark, J.W.; Betts, H.C.; Dombrowski, N.; Szánthó, L.L.; Boyle, R.A.; Daines, S.; Chen, X.; et al. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Caetano-Anollés, G. A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500527–e1500527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgel, L. E. (2004). Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 39(2), 99–123.

- Patel, A.; Malinovska, L.; Saha, S.; Wang, J.; Alberti, S.; Krishnan, Y.; Hyman, A.A. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 2017, 356, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretó, J. Out of fuzzy chemistry: from prebiotic chemistry to metabolic networks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 5394–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, J.D.; Hagan, M.F. Mechanisms of Virus Assembly. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2015, 66, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.; Tars, K.; Liljas, L. The Capsid of the Small RNA Phage PRR1 Is Stabilized by Metal Ions. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 383, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, R.R.; Cakmak, F.P.; Keating, C.D.; Bevilacqua, P.C. Physical Principles and Extant Biology Reveal Roles for RNA-Containing Membraneless Compartments in Origins of Life Chemistry. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F. & de Farias, S. T. (2025b). The Evolution of Biological Compartmentalization: Coacervates, Capsids, and Membranes. SSRN: April, 5th 2025. [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F.; de Farias, S.T. Entering the labyrinth: A hypothesis about the emergence of metabolism from protobiotic routes. Biosystems 2022, 220, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosdocimi, F.; de Farias, S.T. Origin of life: Drawing the big picture. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 180-181, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F.; de Farias, S.T. Major evolutionary transitions before cells: A journey from molecules to organisms. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2024, 191, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosdocimi, F.; de Farias, S.T. Coacervates meet the RNP-world: liquid-liquid phase separation and the emergence of biological compartmentalization. Biosystems 2025, 252, 105480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosdocimi, F.; Farias, S.T. (2019) A emergência dos sistemas biológicos: uma visão molecular sobre a origem da vida. ArteComCiencia (In portuguese). 1 ed. Rio de Janeiro. https://www.amazon.com.br/dp/B08WTHJPM4.

- Prosdocimi, F.; Cortines, J.R.; José, M.V.; Farias, S.T. Decoding viruses: An alternative perspective on their history, origins and role in nature. Biosystems 2023, 231, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F.; de Farias, S.T.; José, M.V. Prebiotic chemical refugia: multifaceted scenario for the formation of biomolecules in primitive Earth. Theory Biosci. 2022, 141, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F.; José, M.V.; de Farias, S.T. The First Universal Common Ancestor (FUCA) as the Earliest Ancestor of LUCA’s (Last UCA) Lineage. Chapter 3. In book: Evolution, Origin of Life, Concepts and Methods. Pierre Pontarotti (Editor). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, F.; José, M.V.; de Farias, S.T. The Theory of Chemical Symbiosis: A Margulian View for the Emergence of Biological Systems (Origin of Life). Acta Biotheor. 2020, 69, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.A.L.; Mougari, S.; Colson, P.; La Scola, B.; Abrahão, J.S. “Tupanvirus”, a new genus in the family Mimiviridae. Arch. Virol. 2018, 164, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwer, F.; Thurber, R.V. Viruses manipulate the marine environment. Nature 2009, 459, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzov, A.S.; Ermakov, A.S. The non-canonical nucleotides and prebiotic evolution. Biosystems 2025, 248, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokers, I.B.A.; Visser, B.S.; Slootbeek, A.D.; Huck, W.T.S.; Spruijt, E. How Droplets Can Accelerate Reactions─Coacervate Protocells as Catalytic Microcompartments. Accounts Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojo, V.; Pomiankowski, A.; Lane, N. A Bioenergetic Basis for Membrane Divergence in Archaea and Bacteria. PLOS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirard, S. J. B. S. Haldane and the origin of life. J. Genet. 2017, 96, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uversky, V.N. Protein intrinsic disorder-based liquid–liquid phase transitions in biological systems: Complex coacervates and membrane-less organelles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 239, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. On the Roles of Protein Intrinsic Disorder in the Origin of Life and Evolution. Life 2024, 14, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Regenmortel, M. H. V. (2000). Introduction to the species concept in virus taxonomy. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel et al. (Eds.), Virus taxonomy: Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (pp. 3–16). Academic Press: San Diego.

- Villarreal, L.P. Viruses and the placenta: the essential virus first view. APMIS 2016, 124, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitas, M.; Dobovišek, A. In the Beginning was a Mutualism - On the Origin of Translation. Discov. Life 2018, 48, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, D. Sorting out viral dark matter. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 526–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Preiner, M.; Xavier, J.C.; Zimorski, V.; Martin, W.F. The last universal common ancestor between ancient Earth chemistry and the onset of genetics. PLOS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woese, C.R.; Fox, G.E. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 5088–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).