Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. System Architecture and Cloud Integration

| Domain | Chemistry | Temp (∘C) | #Packs | Split |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | LFP | –45 | TBD | 70/15/15 |

| EV | NMC | –45 | TBD | 70/15/15 |

| ESS | NCA | 0–50 | TBD | 70/15/15 |

| Config | Latency (ms) | Throughput (msgs/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Onboard-only | TBD | TBD |

| Cloud+Edge (proposed) | TBD | TBD |

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2. Cloud Infrastructure and Databases

2.3. Visualization and Analytics

2.4. Security and Compliance

2.5. Datasets and Testing Conditions

2.6. Performance Metrics

3. Cloud-Based State of Charge (SOC) Estimation

3.1. Limitations of Traditional Methods

3.2. ANN-Based Estimation with Cloud Support

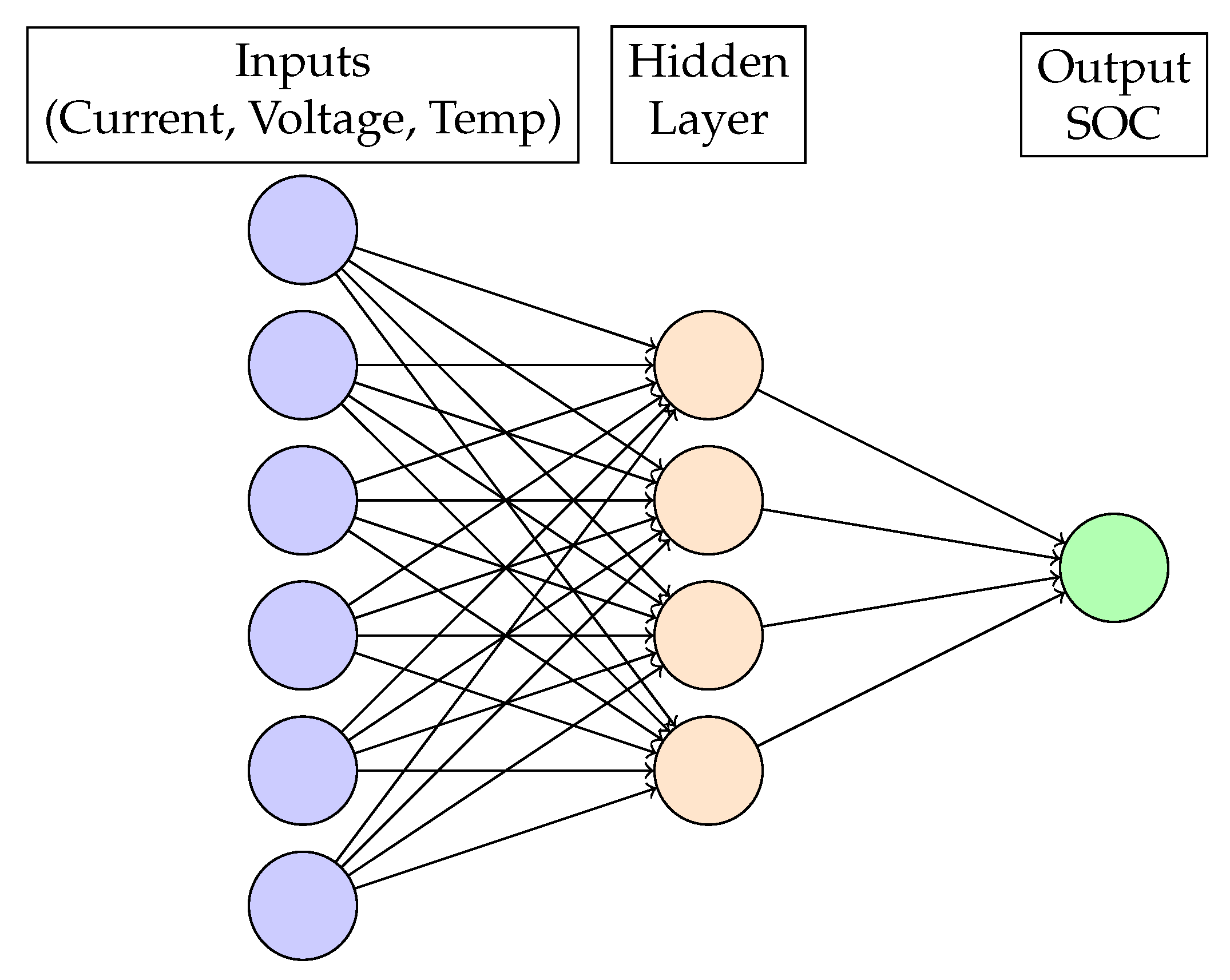

3.3. Neural Network Architecture and Training

3.4. Model Training and Deployment

3.5. Performance Evaluation

3.6. Advantages of Cloud-Aided SOC Estimation

3.7. Robustness Across Battery Types

3.8. Federated Digital-Twin Hybrid SOC/SOH

- Edge: train/update local SOC/SOH heads on recent traces.

- Cloud: aggregate gradients (FedAvg), calibrate twin parameters.

- Serve: deploy compressed models to edge; schedule periodic re-sync.

4. Advanced State of Health (SOH) Prediction Techniques

4.1. Understanding Battery Degradation

4.2. Limitations of Traditional Approaches

4.3. Cloud-Based SOH Analytics

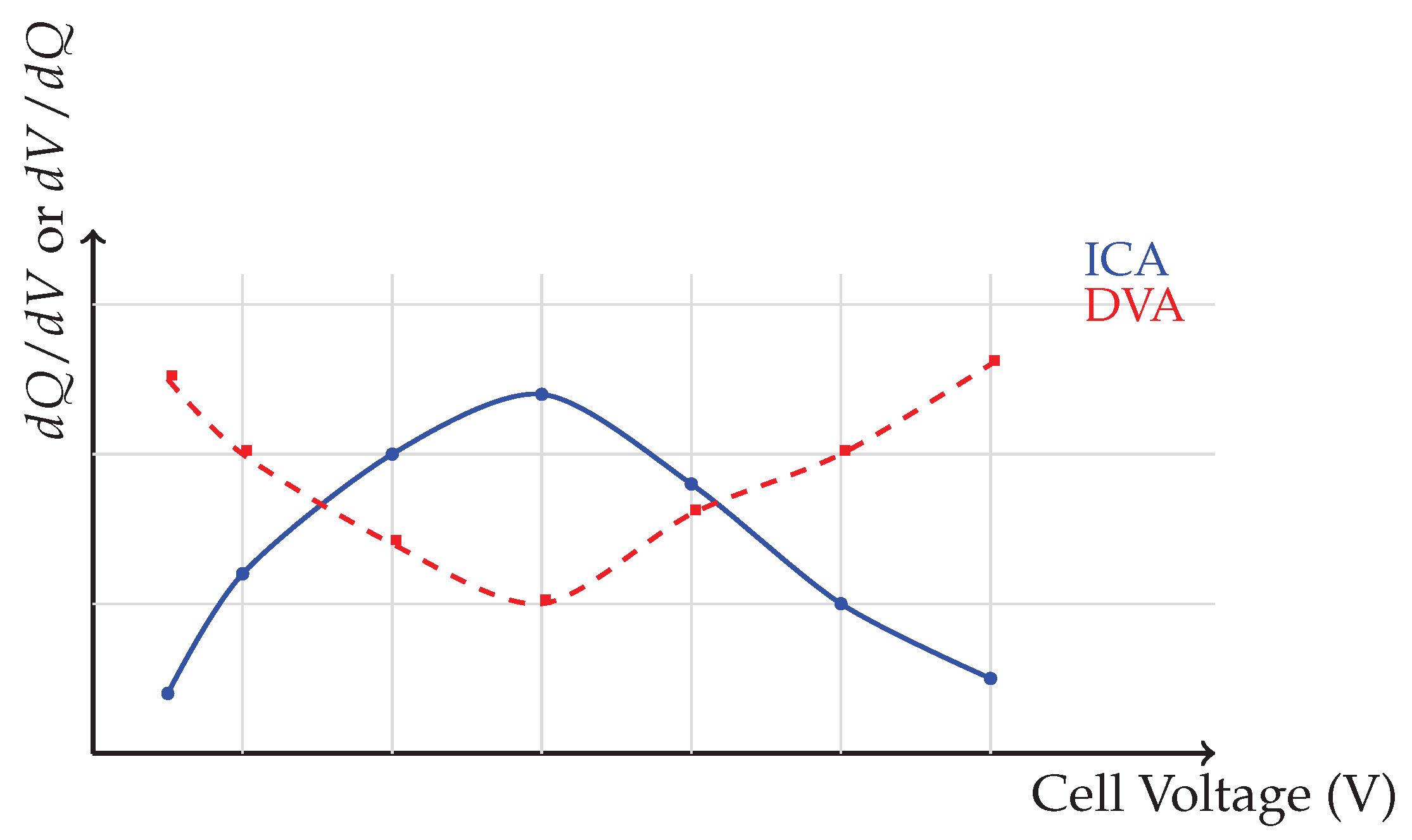

4.4. Feature-Based Methods: DVA and ICA

4.5. Data-Driven Mapping Techniques

4.6. Benefits of Cloud-Based SOH Estimation

4.7. Second-Life and End-of-Life Decisions

5. Cloud-Assisted Thermal Anomaly Detection

5.1. Causes of Thermal Anomalies

5.2. Challenges with Onboard Detection

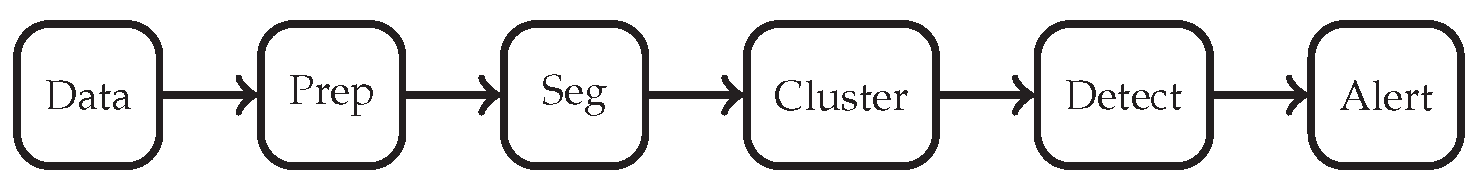

5.3. Cloud-Based Anomaly Detection Pipeline

5.4. Advantages of Pattern-Based Detection

5.5. Case Study and Early Warning Benefits

| Task | Baseline | Proposed | Metric | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC estimation | EKF / Coulomb | Cloud-ANN (edge deploy) | RMSE (%) | TBD |

| SOH prediction | ICA/DVA-only | Hybrid (Section 3.8) | MAE (%) | TBD |

| Thermal detection | Onboard thresholds | Cloud pattern-based | Lead time (min) | TBD |

6. Quantitative Comparative Results

6.1. System Integration and Feedback Loop

6.2. Future Directions

7. Challenges, Solutions, and Future Outlook

7.1. Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

7.2. Future Outlook and Conclusion

References

- Birkl, C.R.; Roberts, M.R.; McTurk, E.; Bruce, P.G.; Howey, D.A. Degradation diagnostics for lithium ion cells. Journal of Power Sources 2017, 341, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Hussain, A.; Mohamed, A. A review of lithium-ion battery state of charge estimation and management system in electric vehicle applications: Challenges and recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 78, 834–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Rentemeister, M.; Badeda, J.; Jöst, D.; Schulte, D.; Sauer, D.U. Digital twin for battery systems: Cloud battery management system with online state-of-charge and state-of-health estimation. Journal of Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Li, L.; Tian, J. Towards a smarter battery management system: A critical review on battery state of health monitoring methods. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 405, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, T.; Duquesnoy, M.; El-Bouysidy, H.; Årén, F.; Gallo-Bueno, A.; Jørgensen, P.B.; Bhowmik, A.; Demortière, A.; Ayerbe, E.; Alcaide, F.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Battery Research: Hype or Reality? Chemical Reviews 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.D.; He, W.; Li, S. Internet of things in industries: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2014, 10, 2233–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemali, E.; Kollmeyer, P.J.; Preindl, M.; Emadi, A. State-of-charge estimation of Li-ion batteries using deep neural networks: A machine learning approach. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 400, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berecibar, M.; Gandiaga, I.; Villarreal, I.; Omar, N.; Van Mierlo, J.; Van Den Bossche, P. Critical review of state of health estimation methods of Li-ion batteries for real applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, K.; Zhang, G.; Habetler, T.G. A survey of methods for monitoring and detecting thermal runaway of lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2019, 436, 226879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Abdollahi, A.; Jones, T.; Habeebullah, A. Data-driven Thermal Anomaly Detection for Batteries using Unsupervised Shape Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 30th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, J.; Nentwich, C.; Endres, F.; Kollenda, A.; Distel, F.; Knoche, T.; Reinhart, G. Data mining in lithium-ion battery cell production. Journal of Power Sources 2019, 413, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Gotion Monitors its EV Battery Solution with InfluxDB, Grafana and AWS, 2022. Available at: https://www.influxdata.com/resources/how-gotion-monitors-its-ev-battery-solution-with-influxdb-grafana-and-aws/.

- Apache Hadoop, 2022. Available at: https://hadoop.apache.org/.

- InfluxDB Overview, 2022. Available at: https://www.influxdata.com/products/influxdb-overview/.

- Amazon Web Services, 2022. Available at: https://aws.amazon.com/.

- Kabir, M.M.; Demirocak, D.E. Degradation mechanisms in Li-ion batteries: a state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Energy Research 2017, 41, 1963–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubarry, M.; Truchot, C.; Liaw, B.Y. Synthesize battery degradation modes via a diagnostic and prognostic model. Journal of Power Sources 2012, 219, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Alexander, M.; Bradley, T.H. Investigation of battery end-of-life conditions for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Journal of Power Sources 2011, 196, 5147–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal runaway mechanism of lithium ion battery for electric vehicles: A review. Energy Storage Materials 2018, 10, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Ouyang, M. A review on the key issues of the lithium ion battery degradation among the whole life cycle. eTransportation 2019, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. Journal of Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).