Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

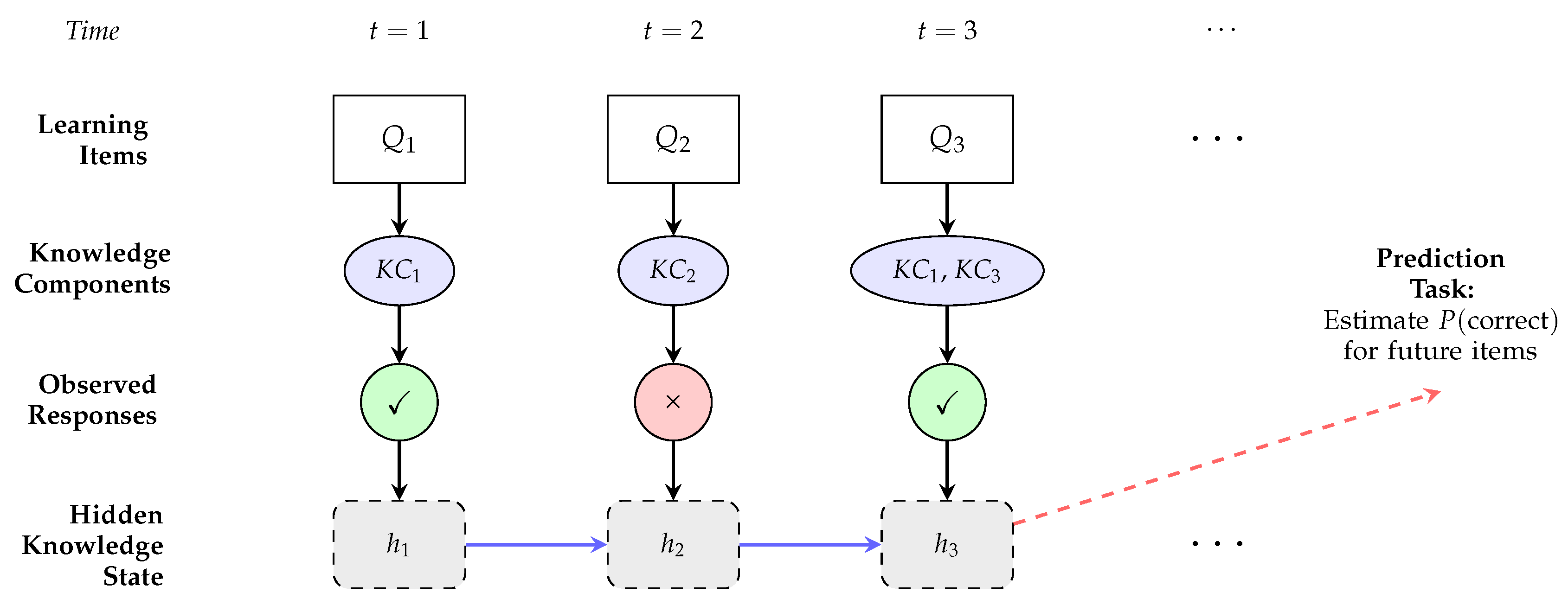

1.1. From Classical to Deep Knowledge Tracing

1.2. Critical Problems in DKT Deployment from Responsible AI Perspective

1.2.1. Data Inconsistency and Class Imbalance

1.2.2. Sequential Stability

1.2.3. Process-Level Interpretability

1.3. Existing Reviews and the Need for This Study

1.4. Research Questions

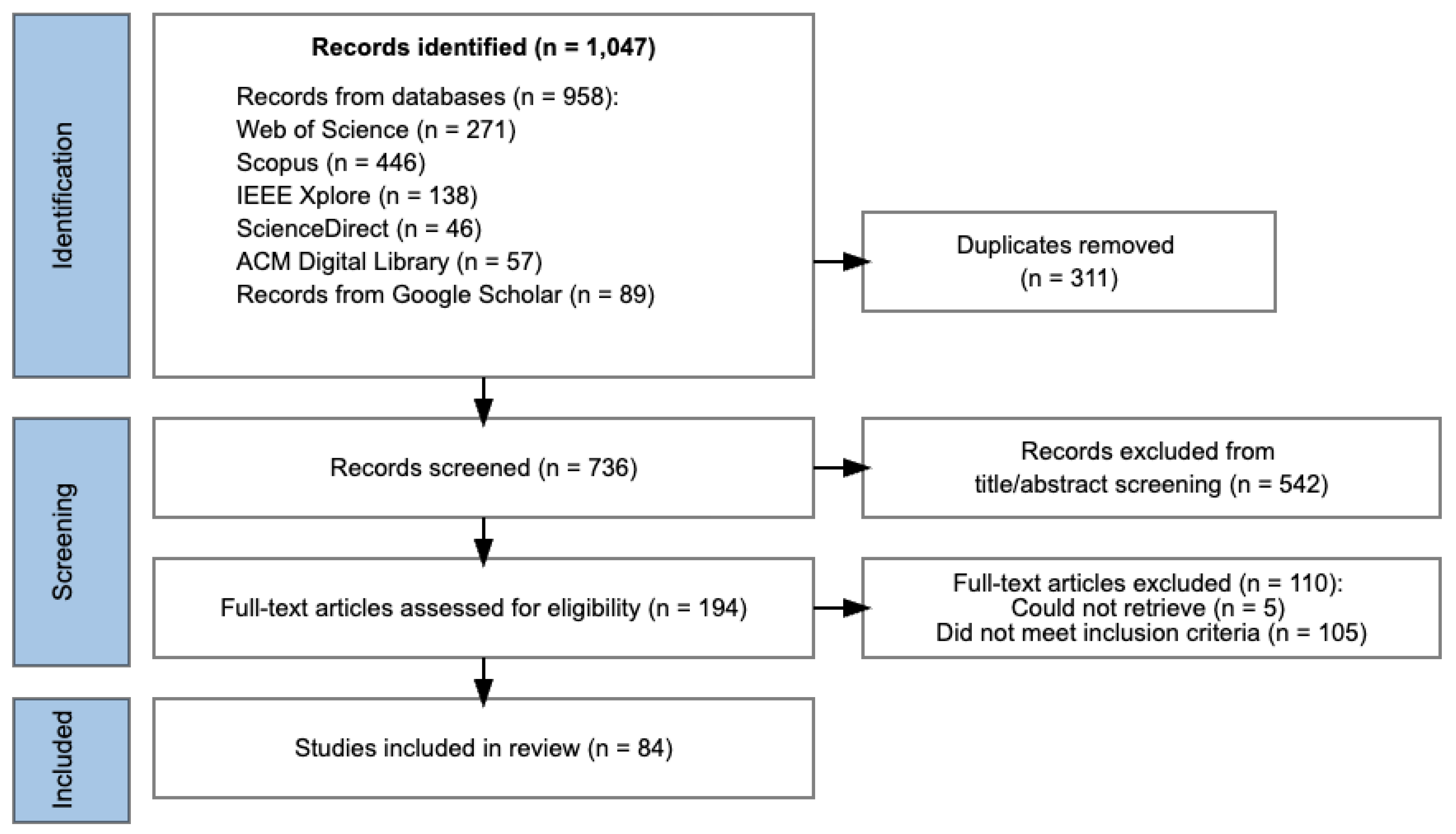

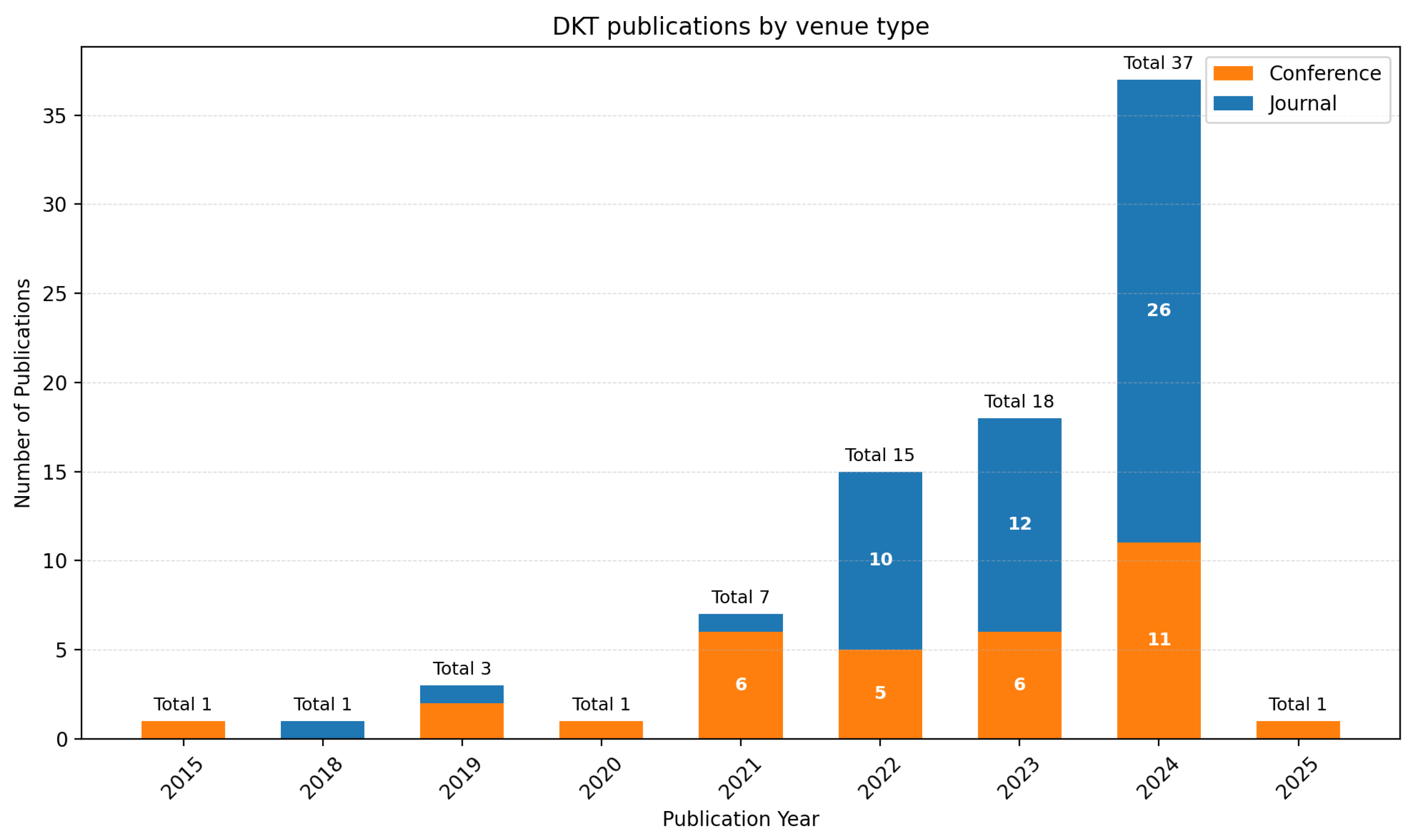

2. Method

2.1. Database and Keywords

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Quality Appraisal

- The quality assessment framework allocated points according to predefined criteria: a response of "Yes" indicated high quality (1 point), "To some extent" indicated medium quality (0.5 points), and "No" indicated low quality (0 points). The highest possible score was 5. Studies scoring 3.5 points or higher were classified as high quality, those between 1.5 and 3.5 points as moderate quality, and those scoring 1.5 points or less as low quality. This approach ensured that only studies of sufficient quality were included, thereby supporting valid and reliable conclusions. All included articles received scores above the low-quality threshold, with all 84 papers falling into the medium- or high-quality categories.

2.5. Information Extraction and Data Analysis

3. Results

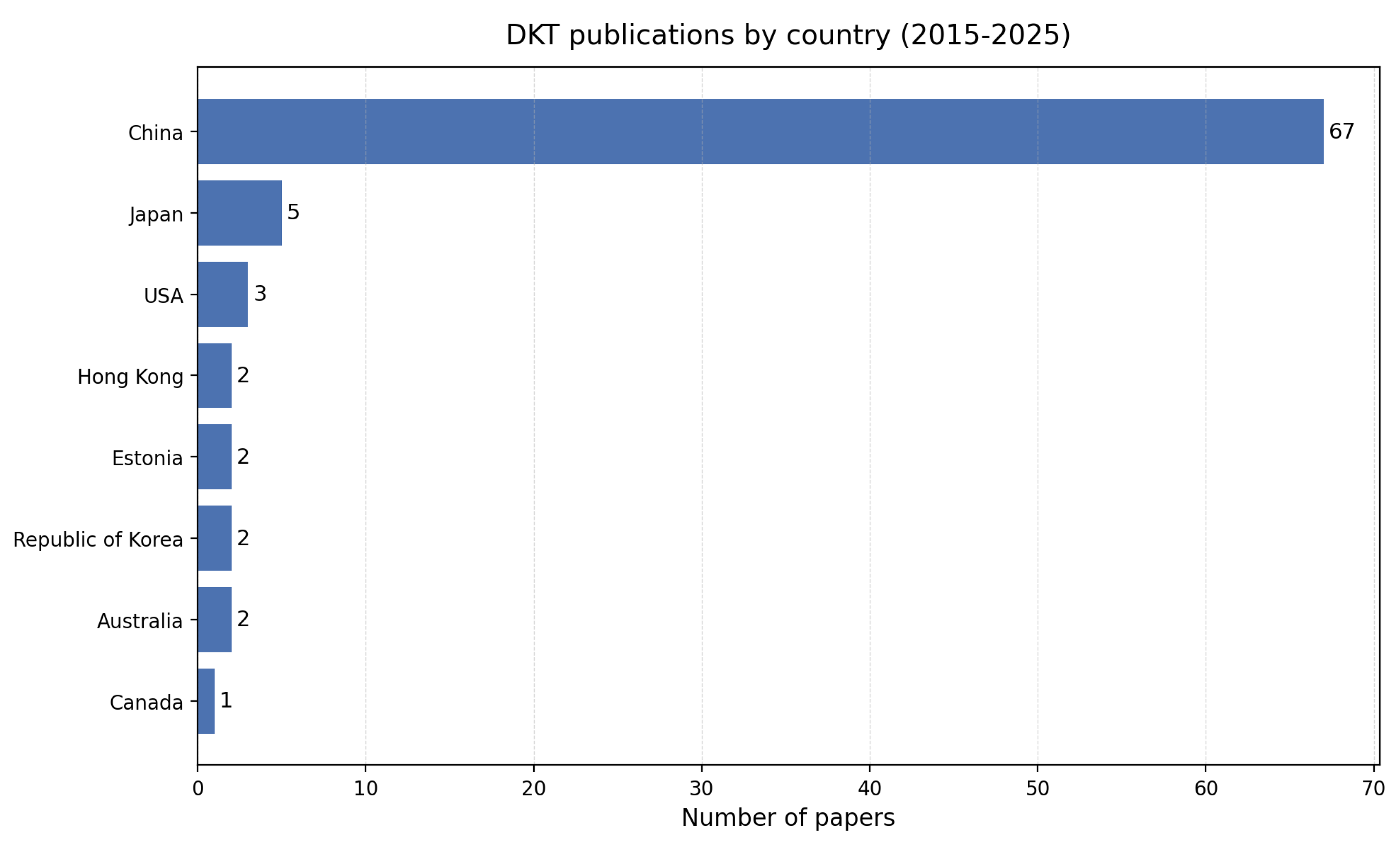

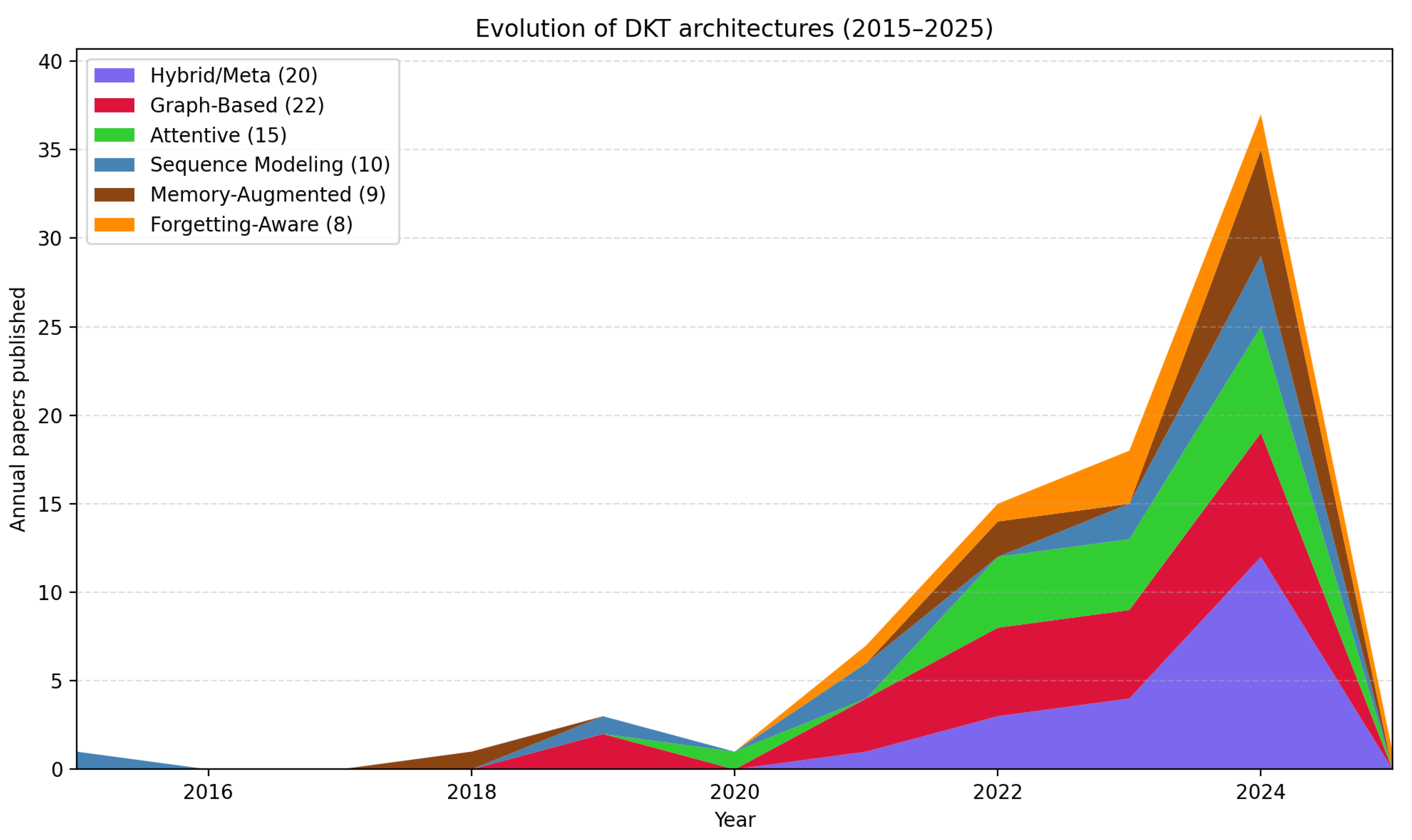

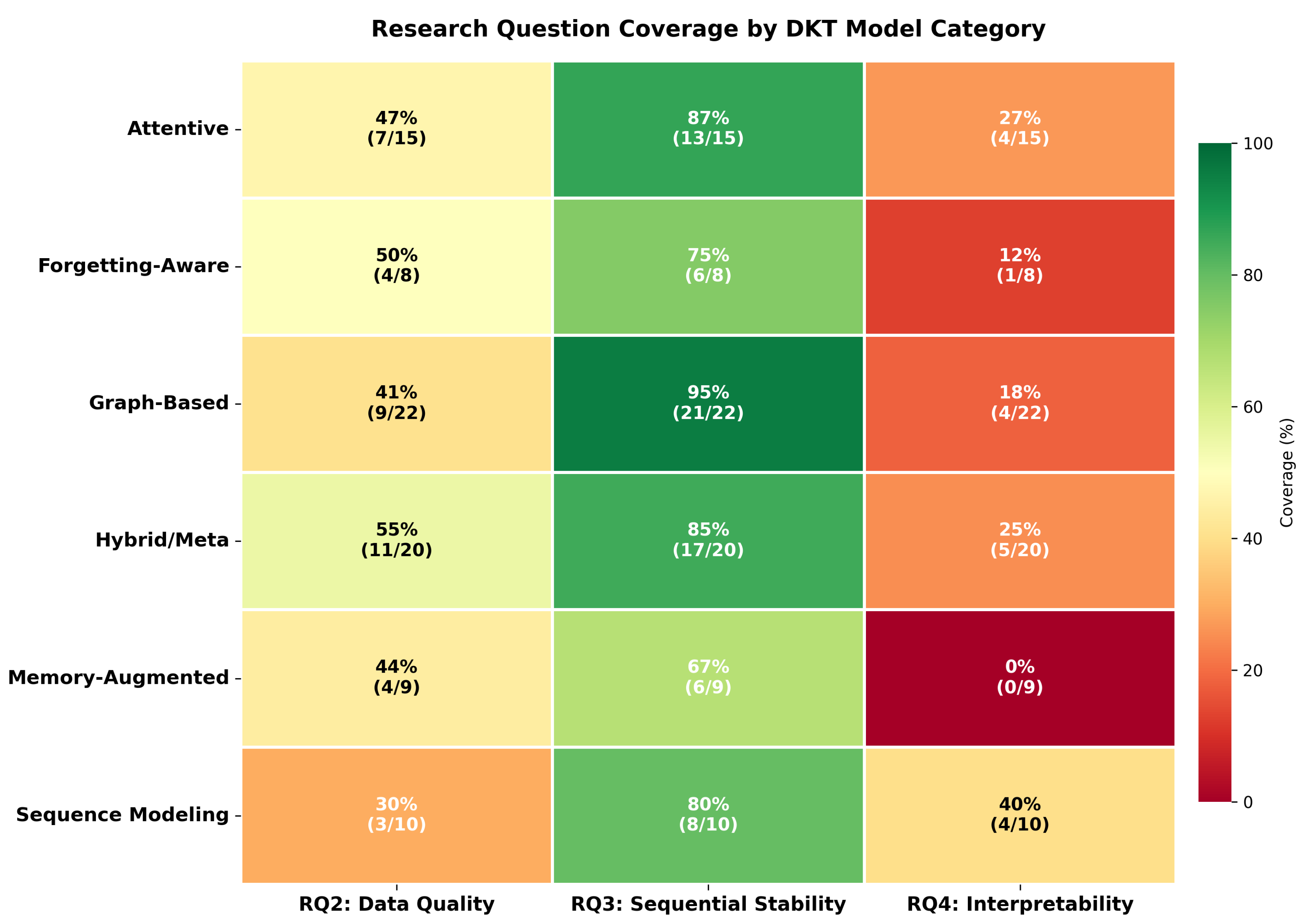

3.1. RQ1: Modeling Landscape

- Modeled characteristics. Beyond dataset selection, the reviewed studies exhibit substantial variation in how they represent and model learner characteristics, as detailed in Table 2. Using the inductive analysis and labeling of the methodology section for each paper where authors described features used as inputs to their DKT models, we identified 1–3-word summaries whose prevalence is as follows: Task performance (the sequence of correct/incorrect answers) in 52 studies; Knowledge components/skills in 40; Extended interaction logs (raw learner interaction traces beyond basic sequences) in 17; Item difficulty in 16; Time-related features (response time or inter-event intervals) in 11; Textual features in 7; Behavioral signals (e.g., speed, attempts, hints, option choices, or media usage) in 4; and Knowledge mapping (mappings of items to skills or multiple skill requirements) in 2. The analysis reveals that most models rely on performance data, often augmented with a subset of temporal, semantic, or difficulty features.

| Theme | Number of Articles | Article IDs |

|---|---|---|

| Task performance | 52 | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 53, 54, 59, 61, 62, 63, 65, 68, 69, 70, 71, 74, 75, 79, 81, 82, 83, 84 |

| Knowledge components/skills | 40 | 2, 3, 4, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 35, 38, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59, 62, 64, 66, 67, 72, 73, 77, 78, 82 |

| Time-related features | 11 | 2, 9, 11, 13, 16, 22, 43, 46, 64, 76, 80 |

| Textual features | 7 | 14, 18, 19, 54, 58, 60, 69 |

| Item difficulty | 16 | 7, 9, 10, 19, 27, 29, 34, 35, 43, 47, 48, 58, 60, 62, 66, 78 |

| Behavioral signals | 4 | 30, 61, 63, 73 |

| Knowledge mapping | 2 | 3, 4 |

| Extended interaction logs | 17 | 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 22, 28, 36, 38, 40, 51, 52, 55, 67, 77, 78, 80 |

- Evaluation metrics. Our analysis reveals broad agreement on evaluation metrics, with AUC being the most common measure, used in 76 studies (90.5%; all paper IDs except: 21, 42, 44, 48, 49, 55, 63, 72), making it the dominant standardfor assessing DKT model performance across diverse educational contexts. Accuracy was reported in 48 studies (57.14%; e.g., IDs 3, 10, 20, 22, 23) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) in 13 studies (15.48%; e.g., IDs 10, 29, 62, 72) as additional metrics. The heavy reliance on AUC reflects the field’s focus on binary classification and its consideration of imbalanced classes, though it does not fully capture the temporal dynamics and sequential dependencies that are central to student learning processes (see Section 3.3).

| Category | Building-block sub-architecture | Representative KT models | Discriminative cue | Paper IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SequenceModeling | RNN / Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) / Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) layers | DKT [11], DKT+ variants | Hidden-state recurrence; no external memory or self-attention. | 8, 20, 23, 28, 36, 52, 53, 60, 70, 84 |

| Memory-Augmented | Key–value memory network | DKVMN, BCKVMN | External differentiable key–value slots updated each step. | 25, 35, 44, 47, 48, 67, 68, 73, 78 |

| Attentive | Pure self-attention / Transformer | SAKT, SAINT(+), AKT | Multi-head attention re-weights past items; no recurrence. | 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18, 38, 56, 61, 74, 81 |

| Graph-Based | Static concept-graph GCN | GKT, JKT | Learner state propagated on a fixed concept graph. | 4, 6, 13, 26, 29, 33, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 54, 55, 58, 59, 65, 66, 69, 72 |

| Forgetting-Aware | Time-decay gating | LPKT, DKT-Forget, DGMN | Explicit decay functions/gates reduce distant influences. | 16, 17, 24, 30, 51, 63, 76, 77 |

| Hybrid/Meta | Ensemble or novel architectures | Mixing-Framework, SAKT+DKT, Graph+Decay | Combines multiple paradigms or explores novel architectures. | 1, 10, 19, 21, 22, 27, 31, 32, 34, 37, 39, 57, 62, 64, 71, 75, 79, 80, 82, 83 |

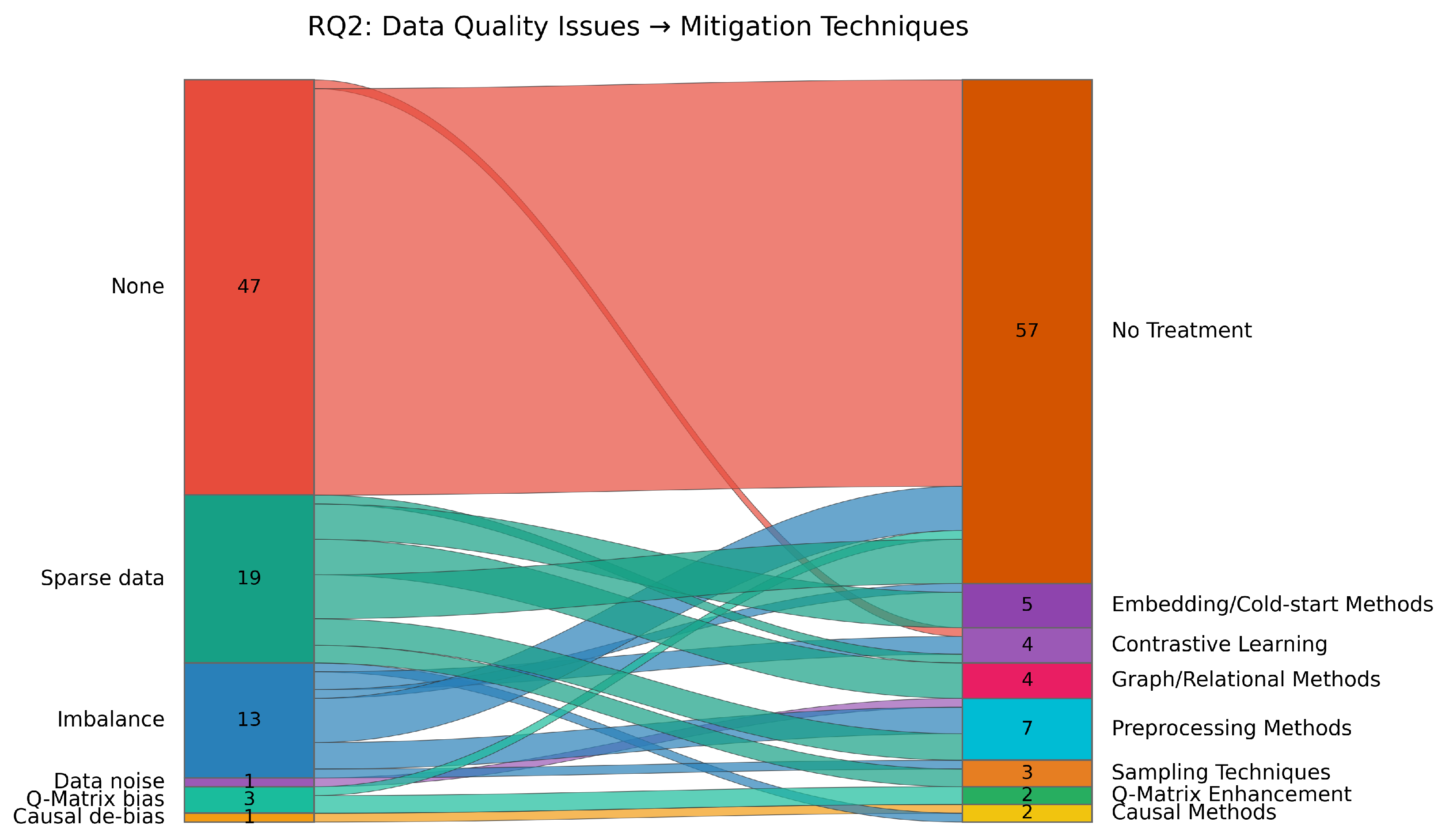

3.2. RQ2: Data Inconsistency and Bias

3.3. RQ3: Sequential Stability

3.4. RQ4: Process-Level Interpretability

4. Discussion

4.1. Modeling Landscape and Architectural Evolution

4.2. Data Quality and Methodological Rigor

4.3. Sequential Stability Assessment

4.4. Interpretability and Transparency

4.5. Cross-Cutting Patterns Across Responsible AI Dimensions

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Reference Table with Key Characteristics

| ID | Reference | Category | Dataset | Metrics | Data Quality | Stability | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Li, et al. (2024). A Genetic Causal Explainer for Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, EdNet | AUC | None | None | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 2 | Cheng, et al. (2022). A Knowledge Query Network Model Based on Rasch Model Embedding for Personalized Online Learning. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | None | Forgetting | Not considered |

| 3 | Zhao, et al. (2023). A novel framework for deep knowledge tracing via gating-controlled forgetting and learning mechanisms. | Attentive | ASSIST15, ASSIST17, Junyi | AUC, ACC | Q-Matrix bias | Visual | Not considered |

| 4 | Liu, et al. (2024). A probabilistic generative model for tracking multi-knowledge concept mastery probability. | Graph-Based | Algebra2006, Algebra2008, POJ | AUC, ACC, RMSE, MAE, MSE, Precision, Recall | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 5 | Zhang, et al. (2024). A Question-centric Multi-experts Contrastive Learning Framework for Improving the Accuracy and Interpretability of Deep Sequential Knowledge Tracing Models. | Attentive | ASSIST09, EdNet, Algebra2005 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 6 | Liu, et al. (2022). Ability boosted knowledge tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, AICFE | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 7 | Cheng, et al. (2022). AdaptKT: A Domain Adaptable Method for Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC, F1 | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 8 | Wang, et al. (2023). An Efficient and Generic Method for Interpreting Deep Learning based Knowledge Tracing Models. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST15 | AUC | None | None | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 9 | Luo, et al. (2024). An efficient state-aware Coarse-Fine-Grained model for Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST15, ASSIST17, Junyi | AUC, ACC, RMSE, F1 | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 10 | Shen, et al. (2022). Assessing Student’s Dynamic Knowledge State by Exploring the Question Difficulty Effect. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST12, Eedi | AUC, ACC, RMSE | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 11 | Xu, et al. (2024). Bridging the Vocabulary Gap: Using Side Information for Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | Private dataset | AUC | Sparse data | None | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 12 | Zu, et al. (2023). CAKT: Coupling contrastive learning with attention networks for interpretable knowledge tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 13 | Li, et al. (2023). Calibrated Q-Matrix-Enhanced Deep Knowledge Tracing with Relational Attention Mechanism. | Graph-Based | ASSIST12, Eedi | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 14 | Ghosh, et al. (2020). Context-Aware Attentive Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 15 | Chen, et al. (2022). DCKT: A Novel Dual-Centric Learning Model for Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST15 | AUC | None | Forgetting | Not considered |

| 16 | Abdelrahman, et al. (2023). Deep Graph Memory Networks for Forgetting-Robust Knowledge Tracing. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, Statics2011, KDD2010 | AUC, ACC, Loss | None | Forgetting | Not considered |

| 17 | Tsutsumi, et al. (2024). Deep Knowledge Tracing Incorporating a Hypernetwork With Independent Student and Item Networks. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC, ACC, Loss | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 18 | Yang, et al. (2022). Deep Knowledge Tracing with Learning Curves. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | Sparse data | None | Not considered |

| 19 | Wang, et al. (2024). Deep Knowledge Tracking Integrating Programming Exercise Difficulty and Forgetting Factors. | Hybrid/Meta | Other dataset | AUC, F1 | None | Forgetting | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 20 | Tsutsumi, et al. (2024). Deep-IRT with a Temporal Convolutional Network for Reflecting Students’ Long-Term History of Ability Data. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, Junyi | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 21 | Lu, et al. (2024). Design and evaluation of Trustworthy Knowledge Tracing Model for Intelligent Tutoring System. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09 | AUC | None | None | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 22 | Wang, et al. (2024). DF-EGM: Personalised Knowledge Tracing with Dynamic Forgetting and Enhanced Gain Mechanisms. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Algebra2005 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 23 | Kim, et al. (2021). DiKT: Dichotomous Knowledge Tracing. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 24 | Zhou, et al. (2024). Discovering Multi-Relational Integration for Knowledge Tracing with Retentive Networks. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 25 | Zhang, et al. (2024). DKVMN-KAPS: Dynamic Key-Value Memory Networks Knowledge Tracing With Students’ Knowledge-Absorption Ability and Problem-Solving Ability. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 26 | Xu, et al. (2024). DKVMN&MRI: A new deep knowledge tracing model based on DKVMN incorporating multi-relational information. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, EdNet | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 27 | Wang, et al. (2023). Dynamic Cognitive Diagnosis: An Educational Priors-Enhanced Deep Knowledge Tracing Perspective. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST12 | AUC, ACC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 28 | Liu, et al. (2019). EKT: Exercise-Aware Knowledge Tracing for Student Performance Prediction. | Sequence Modeling | Other dataset | AUC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 29 | Pu, et al. (2024). ELAKT: Enhancing Locality for Attentive Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | Private dataset | AUC, ACC, RMSE, MAE | None | Quantitative | Not considered |

| 30 | Cai, et al. (2025). Enhanced Knowledge Tracing via Frequency Integration and Order Sensitivity. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, Statics2011 | AUC, ACC, MAE | Imbalance | Quantitative | Not considered |

| 31 | Qian, et al. (2024). Enhanced Knowledge Tracing With Learnable Filter. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST15 | AUC | None | Visual | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 32 | Liu, et al. (2023). Enhancing Deep Knowledge Tracing with Auxiliary Tasks. | Hybrid/Meta | Algebra2005, Algebra2006, Bridge | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 33 | Guo, et al. (2021). Enhancing Knowledge Tracing via Adversarial Training. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 34 | Zhao, et al. (2023). Exploiting multiple question factors for knowledge tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, EdNet, KT1 | AUC, ACC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 35 | Zhang, et al. (2024). Explore Bayesian analysis in Cognitive-aware Key-Value Memory Networks for knowledge tracing in online learning. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, Algebra2005 | AUC | Sparse data | None | Not considered |

| 36 | Wu, et al. (2021). Federated Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST (unspecified), MATH | AUC, ACC, RMSE, MSE | Imbalance | None | Not considered |

| 37 | Hooshyar, et al. (2022). GameDKT: Deep knowledge tracing in educational games. | Hybrid/Meta | Taiwan | AUC, ACC, Precision, Recall | Sparse data | None | Not considered |

| 38 | Liang, et al. (2024). GELT: A graph embeddings based lite-transformer for knowledge tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 39 | Yanyou, et al. (2024). Global Feature-guided Knowledge Tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST12, ASSIST17, FrcSub | AUC, ACC, RMSE | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 40 | Nakagawa, et al. (2019). Graph-based knowledge tracing: Modeling student proficiency using graph neural networks. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 41 | Wang, et al. (2023). GraphCA: Learning from Graph Counterfactual Augmentation for Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Algebra2006 | AUC, ACC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 42 | Liu, et al. (2024). Heterogeneous Evolution Network Embedding with Temporal Extension for Intelligent Tutoring Systems. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 43 | Yang, et al. (2024). Heterogeneous graph-based knowledge tracing with spatiotemporal evolution. | Graph-Based | Private dataset | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 44 | Yang, et al. (2018). Implicit Heterogeneous Features Embedding in Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST (unspecified), Junyi | AUC | Imbalance | None | Not considered |

| 45 | Chen, et al. (2023). Improving Interpretability of Deep Sequential Knowledge Tracing Models with Question-centric Cognitive Representations. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, Algebra2005 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 46 | Xu, et al. (2023). Improving knowledge tracing via a heterogeneous information network enhanced by student interactions. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, EdNet, Statics2011 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Embedding or trajectory visualisation |

| 47 | Shu, et al. (2024). Improving Knowledge Tracing via Considering Students’ Interaction Patterns. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST17 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 48 | Long, et al. (2022). Improving Knowledge Tracing with Collaborative Information. | Memory-Augmented | EdNet | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 49 | Tato, et al. (2022). Infusing Expert Knowledge Into a Deep Neural Network Using Attention Mechanism for Personalized Learning Environments. | Graph-Based | Other dataset | ACC, F1, Precision, Recall | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 50 | Zhang, et al. (2021). Input-Aware Neural Knowledge Tracing Machine. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Algebra2006 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 51 | He, et al. (2023). Integrating fine-grained attention into multi-task learning for knowledge tracing. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, Statics2011 | AUC, ACC | Imbalance | None | Not considered |

| 52 | Chen, et al. (2024). Interaction Sequence Temporal Convolutional Based Knowledge Tracing. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Algebra2005 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 53 | Sun, et al. (2024). Interpretable Knowledge Tracing with Multiscale State Representation. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 54 | Tong, et al. (2022). Introducing Problem Schema with Hierarchical Exercise Graph for Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | Other dataset | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 55 | Song, et al. (2021). JKT: A joint graph convolutional network based Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSISTChall | AUC, ACC | Imbalance | None | Not considered |

| 56 | Pan, et al. (2024). Knowledge Graph and Personalized Answer Sequences for Programming Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | Other dataset | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 57 | Gan, et al. (2022). Knowledge interaction enhanced sequential modeling for interpretable learner knowledge diagnosis in intelligent tutoring systems. | Hybrid/Meta | Statics2011, Algebra2005, Algebra2006 | AUC, ACC, Loss | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 58 | Lee & Yeung (2019). Knowledge Query Network for Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 59 | Gan, et al. (2022). Knowledge structure enhanced graph representation learning model for attentive knowledge tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 60 | Xiao, et al. (2023). Knowledge tracing based on multi-feature fusion. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC | None | Visual | Interpretable architecture (IRT / rule-based layer) |

| 61 | Xu, et al. (2023). Learning Behavior-oriented Knowledge Tracing. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Junyi | AUC, ACC, RMSE | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 62 | Huang, et al. (2024). Learning consistent representations with temporal and causal enhancement for knowledge tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST12, EdNet, KT1 | AUC, ACC, RMSE | Causal de-bias | Visual | Not considered |

| 63 | Wang, et al. (2021). Learning from Non-Assessed Resources: Deep Multi-Type Knowledge Tracing. | Forgetting-Aware | EdNet, Junyi, MORF | AUC, RMSE, MSE | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 64 | Shen, et al. (2021). Learning Process-consistent Knowledge Tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST12, EdNet, KT1 | AUC, ACC | Q-Matrix bias | Visual | Not considered |

| 65 | Cui, et al. (2024). Leveraging Pedagogical Theories to Understand Student Learning Process with Graph-based Reasonable Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, Junyi | AUC | Sparse data | Forgetting | Not considered |

| 66 | Zhu, et al. (2024). Meta-path structured graph pre-training for improving knowledge tracing in intelligent tutoring. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, EdNet | AUC, ACC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 67 | Zhang, et al. (2024). MLC-DKT: A multi-layer context-aware deep knowledge tracing model. | Memory-Augmented | Junyi | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 68 | Cui, et al. (2024). Model-agnostic counterfactual reasoning for identifying and mitigating answer bias in knowledge tracing. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST09, ASSIST17, EdNet | AUC, ACC | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 69 | He, et al. (2022). Modeling knowledge proficiency using multi-hierarchical capsule graph neural network. | Graph-Based | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, ASSIST17 | AUC | Sparse data | Visual | Not considered |

| 70 | Xu, et al. (2024). Modeling Student Performance Using Feature Crosses Information for Knowledge Tracing. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | None | Visual | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 71 | Lee, et al. (2024). MonaCoBERT: Monotonic Attention Based ConvBERT for Knowledge Tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST17 | AUC, RMSE | Sparse data | Visual | Feature attribution / attention analysis |

| 72 | Shen, et al. (2023). Monitoring Student Progress for Learning Process-Consistent Knowledge Tracing. | Graph-Based | ASSIST12, EdNet, KT1 | AUC, ACC, RMSE, MSE | Q-Matrix bias | Visual | Not considered |

| 73 | Huang, et al. (2024). Pull together: Option-weighting-enhanced mixture-of-experts knowledge tracing. | Memory-Augmented | EdNet, Eedi, KT1 | AUC, ACC, RMSE | Sparse data | None | Not considered |

| 74 | Yu, et al. (2024). RIGL: A Unified Reciprocal Approach for Tracing the Independent and Group Learning Processes. | Attentive | ASSIST12, MATH | AUC, ACC, RMSE, MAE | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 75 | Dai, et al. (2024). Self-paced contrastive learning for knowledge tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, KDD2010 | AUC, ACC, F1 | Imbalance | Visual | Not considered |

| 76 | Song & Luo (2023). SFBKT: A Synthetically Forgetting Behavior Method for Knowledge Tracing. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST17 | AUC | Sparse data | None | Not considered |

| 77 | Wu, et al. (2022). SGKT: Session graph-based knowledge tracing for student performance prediction. | Forgetting-Aware | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC | Sparse data | Quantitative | Not considered |

| 78 | Ma, et al. (2022). SPAKT: A Self-Supervised Pre-TrAining Method for Knowledge Tracing. | Memory-Augmented | ASSIST09, ASSIST12, EdNet | AUC | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 79 | Zhu, et al. (2024). Stable Knowledge Tracing Using Causal Inference. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC, F1 | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 80 | Danial Hooshyar (2024). Temporal learner modelling through integration of neural and symbolic architectures. | Hybrid/Meta | Other dataset | ACC, F1, Precision, Recall | Imbalance | Sensitivity | Not considered |

| 81 | Chen, et al. (2023). TGKT-Based Personalized Learning Path Recommendation with Reinforcement Learning. | Attentive | ASSIST09, ASSIST12 | Other | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 82 | Duan, et al. (2024). Towards more accurate and interpretable model: Fusing multiple knowledge relations into deep knowledge tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST (unspecified), EdNet, Junyi | AUC, ACC, F1 | Data noise | Visual | Not considered |

| 83 | Wang, et al. (2023). What is wrong with deep knowledge tracing? Attention-based knowledge tracing. | Hybrid/Meta | ASSIST09, ASSIST15, Statics2011 | AUC, F1 | None | Visual | Not considered |

| 84 | Piech, et al. (2015). Deep Knowledge Tracing. | Sequence Modeling | ASSIST09 | AUC, ACC | None | Visual | Not considered |

Appendix B. Glossary of Acronyms

| ACC | Accuracy |

| AFM | Additive Factor Model |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASSIST | ASSISTments (various versions including ASSIST09, ASSIST12, ASSIST15, ASSIST17) |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BCKVMN | Bridging Concept-Key-Value Memory Networks |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BKT | Bayesian Knowledge Tracing |

| CAM | Class Activation Mapping |

| CAT-KT | Contrastive-Augmented Transformer for Knowledge Tracing |

| CGLKT | Contrastive Graph Learner for Knowledge Tracing |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DGMN | Dynamic Graph Memory Network |

| DKT | Deep Knowledge Tracing |

| DKTSR | Deep Knowledge Tracing via Self-Attention Residuals |

| DKVMN | Dynamic Key-Value Memory Network |

| DyKT | Dynamic Knowledge Tracing |

| EdNet | Education Neural Network dataset |

| EKT | Enhanced Knowledge Tracing |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| GAT-GKT | Graph Attention Network-Graph Knowledge Tracing |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GIKT | Graph-based Interaction Knowledge Tracing |

| GKT | Graph Knowledge Tracing |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| HMN | Hierarchical Memory Network |

| IRT | Item Response Theory |

| JKT | Joint Knowledge Tracing |

| KT | Knowledge Tracing |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LPKT | Learning Process-consistent Knowledge Tracing |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| MMAKT | Multi-Modal Attentive Knowledge Tracing |

| MOOCs | Massive Open Online Courses |

| NPA-KT | Neural Performance Assessment for Knowledge Tracing |

| PFA | Performance Factor Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RAI | Responsible AI |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SAINT | Separated Self-Attentive Neural Knowledge Tracing |

| SAKT | Self-Attentive Knowledge Tracing |

| SERKT | Sequential Event Representation for Knowledge Tracing |

| SGKT | Session Graph Knowledge Tracing |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| Statics2011 | Engineering statics course dataset from 2011 |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

References

- Xieling Chen, Di Zou, Haoran Xie, Gary Cheng, and Caixia Liu. Two decades of artificial intelligence in education. Educational Technology & Society, 25(1):28–47, 2022.

- Danial Hooshyar and Marek J. Druzdzel. Memory-based dynamic bayesian networks for learner modeling: Towards early prediction of learners’ performance in computational thinking. Education Sciences, 14(8):917, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin and Reyer Van der Vlies. Trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) in education: Promises and challenges. OECD education working papers, 1(218):0_1–17, 2020.

- Sarah Alwarthan, Nida Aslam, and Irfan Ullah Khan. An explainable model for identifying at-risk student at higher education. IEEE Access, 10:107649–107668, 2022.

- Danial Hooshyar, Yueh-Min Huang, Yeongwook Yang, et al. A three-layered student learning model for prediction of failure risk in online learning. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci, 12:28, 2022.

- Miao Dai, Jui-Long Hung, Xu Du, Hengtao Tang, and Hao Li. Knowledge tracing: A review of available technologies. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 14(2):1–20, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Abir Abyaa, Mohammed Khalidi Idrissi, and Samir Bennani. Learner modelling: systematic review of the literature from the last 5 years. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(5):1105–1143, 2019.

- Douglas B. Lenat, Mayank Prakash, and Mary Shepherd. Cyc: toward programs with common sense. Communications of the ACM, 28(8):739–752, 1985.

- Yu Lin, Hong Chen, Wei Xia, Fan Lin, Pengcheng Wu, Zongyue Wang, and Yong Li. A comprehensive survey on deep learning techniques in educational data mining. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.04761, 2023. Preprint.

- Eleni Ilkou and Maria Koutraki. Symbolic vs sub-symbolic AI methods: Friends or enemies? In CIKM (Workshops), volume 2699, 2020.

- Chris Piech, Jonathan Bassen, Jonathan Huang, Surya Ganguli, Mehran Sahami, Leonidas J. Guibas, and Jascha Sohl-Dickstein. Deep knowledge tracing. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015), pages 505–513, 2015. URL https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2015/hash/bac9162b47c56fc8a4d2a519803d51b3-Abstract.html.

- Mohammad Khajah, Robert V Lindsey, and Michael C Mozer. How deep is knowledge tracing? In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, pages 94–101, 2016.

- Xiaolu Xiong, Siyuan Zhao, Eric G. Van Inwegen, and Joseph E. Beck. Going deeper with deep knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, pages 545–550, 2016.

- Danial Hooshyar, Gustav Šír, Yeongwook Yang, Eve Kikas, Raija Hämäläinen, Tommi Kärkkäinen, Dragan Gašević, and Roger Azevedo. Towards responsible AI for education: Hybrid human-AI to confront the elephant in the room, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.16148.

- Danial Hooshyar, Roger Azevedo, and Yeongwook Yang. Augmenting deep neural networks with symbolic educational knowledge: Towards trustworthy and interpretable AI for education. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 6(1):593–618, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Danial Hooshyar and Yeongwook Yang. Problems with SHAP and LIME in interpretable AI for education: A comparative study of post-hoc explanations and neural-symbolic rule extraction. IEEE Access, 2024.

- Yue Gong, Joseph Beck, and Neil Heffernan. How to construct more accurate student models: Comparing and optimizing knowledge tracing and performance factor analysis. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 21(1-2):27–46, 2011.

- Andrea Aler Tubella, Marçal Mora Cantallops, and Juan Carlos Nieves. How to teach responsible AI in higher education: challenges and opportunities. Ethics and Information Technology, 25(3):31, 2023.

- Florina Mihai Leta and Diane-Paula Vancea. Ethics in education: Exploring the ethical implications of artificial intelligence implementation. Ovidius University Annals: Economic Sciences Series, 23(1):445–451, 2023.

- Mirka Saarela, Sachini Gunasekara, and Ayaz Karimov. The EU AI act: Implications for ethical AI in education. In International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology, pages 36–50. Springer, 2025.

- Ghodai Abdelrahman, Qing Wang, and Bernardo Nunes. Knowledge tracing: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(11):1–37, 2023.

- Xiangyu Song, Jianxin Li, Taotao Cai, Shuiqiao Yang, Tingting Yang, and Chengfei Liu. A survey on deep learning based knowledge tracing. Knowledge-Based Systems, 258:110036, 2022.

- Albert T. Corbett and John R. Anderson. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User modeling and user-adapted interaction, 4(4):253–278, 1995.

- Brett van de Sande. Properties of the bayesian knowledge tracing model. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, pages 184–190, 2013.

- Radek Pelánek. Bayesian knowledge tracing, logistic models, and beyond: an overview of learner modeling techniques. User modeling and user-adapted interaction, 27(3):313–350, 2017.

- Ye Mao. Deep learning vs. bayesian knowledge tracing: Student models for interventions. Journal of educational data mining, 10(2), 2018.

- Joseph E. Beck and Kai-min Chang. Identifiability: A fundamental problem of student modeling. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4511:137–146, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ryan Shaun Baker, Albert T Corbett, and Vincent Aleven. More accurate student modeling through contextual estimation of slip and guess probabilities in bayesian knowledge tracing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5091:406–415, 2008.

- Philip I. Pavlik, Hao Cen, and Kenneth R. Koedinger. Performance factors analysis - a new alternative to knowledge tracing. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, pages 531–538. Springer, 2009.

- Théophile Gervet, Kenneth Koedinger, Jeff Schneider, and Tom M. Mitchell. When is deep learning the best approach to knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, pages 31–40, 2020.

- Christopher James Maclellan, Ran Liu, and Kenneth R. Koedinger. Accounting for slipping and other false negatives in logistic models of student learning. In Educational Data Mining, 2015.

- Christopher James Maclellan. Investigating the impact of slipping parameters on additive factors model parameter estimates. In Educational Data Mining, 2016.

- T Merembayev, S Amirgaliyeva, and K Kozhaly. Using item response theory in machine learning algorithms for student response data. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Information Systems and Technologies (SIST), 2021.

- Adrienne S. Kline, T. Kline, Zahra Shakeri Hossein Abad, and Joon Lee. Novel feature selection for artificial intelligence using item response theory for mortality prediction. In Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2020.

- Fanglan Ma, Changsheng Zhu, and Dukui Liu. A deeper knowledge tracking model integrating cognitive theory and learning behavior. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 2024.

- Sevvandi Kandanaarachchi and Kate Smith-Miles. Comprehensive algorithm portfolio evaluation using item response theory. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2023.

- Sein Minn, Jill-Jênn Vie, Koh Takeuchi, Hisashi Kashima, and Feida Zhu. Interpretable knowledge tracing: Simple and efficient student modeling with causal relations. In Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 35, pages 13468–13476, 2021.

- Bryan Lim and Stefan Zohren. Time-series forecasting with deep learning: a survey. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 379(2194):20200209, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos Benidis, Syama Sundar Rangapuram, Valentin Flunkert, Yuyang Wang, Danielle Maddix, Caner Turkmen, Jan Gasthaus, Michael Bohlke-Schneider, David Salinas, Lorenzo Stella, Laurent Callot, and Tim Januschowski. Deep learning for time series forecasting: Tutorial and literature survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(6):1–36, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Andrea Cini, Ivan Marisca, Daniele Zambon, and Cesare Alippi. Graph deep learning for time series forecasting. ACM Computing Surveys, 57(12):1–34, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 30, pages 5998–6008, 2017.

- Wilson Chango, Juan A. Lara, Rebeca Cerezo, and Cristóbal Romero. A review on data fusion in multimodal learning analytics and educational data mining. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 12(4):e1458, 2022.

- Sein Minn, Yi Yu, Michel C Desmarais, Feida Zhu, and Jill-Jênn Vie. Deep knowledge tracing and dynamic student classification for knowledge component mastery. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, pages 142–151, 2018.

- Chun-Kit Yeung and Dit-Yan Yeung. Addressing two problems in deep knowledge tracing via prediction-consistent regularization. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual ACM Conference on Learning at Scale, pages 1–10, 2018.

- Xianqing Wang, Zetao Zheng, Jia Zhu, and Weihao Yu. What is wrong with deep knowledge tracing? attention-based knowledge tracing. Applied Intelligence, 53:1–20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tarek R. Besold, Artur d’Avila Garcez, Sebastian Bader, Howard Bowman, Pedro Domingos, Pascal Hitzler, Kai-Uwe Kühnberger, Luis C. Lamb, Daniel Lowd, Priscila Machado Vieira Lima, et al. Neural-symbolic learning and reasoning: A survey and interpretation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021.

- Shalini Pandey and George Karypis. A self-attentive model for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, 2019. Reported ∼4.43% average AUC improvement over SOTA models.

- Yang Yang, Jian Shen, Yanru Qu, Yunfei Liu, Kerong Wang, Yaoming Zhu, Weinan Zhang, and Yong Yu. Gikt: a graph-based interaction model for knowledge tracing. In Joint European conference on machine learning and knowledge discovery in databases, pages 299–315. Springer, 2020.

- Charl Maree, Jan Erik Modal, and Christian W. Omlin. Towards responsible AI for financial transactions. In IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), pages 16–21, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alejandro Barredo Arrieta, Natalia Díaz-Rodríguez, Javier Del Ser, Adrien Bennetot, Siham Tabik, Alberto Barbado, Salvador García, Sergio Gil-Lopez, Daniel Molina, Richard Benjamins, Raja Chatila, and Francisco Herrera. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information Fusion, 58:82–115, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ray Eitel-Porter. Beyond the promise: implementing ethical AI. AI and Ethics, 1(1):73–80, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Karl Werder, Balasubramaniam Ramesh, and Rongen Zhang. Establishing data provenance for responsible artificial intelligence systems. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 13(2):1–23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Maurice Jakesch, Zana Buçinca, Saleema Amershi, and Alexandra Olteanu. How different groups prioritize ethical values for responsible AI. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pages 310–323, 2022.

- Sabrina Goellner, Marina Tropmann-Frick, and Boštjan Brumen. Responsible artificial intelligence: A structured literature review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06910, 2024. Preprint.

- A. Tato and R. Nkambou. Infusing expert knowledge into a deep neural network using attention mechanism for personalized learning environments. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chaoran Cui, Hebo Ma, Xiaolin Dong, Chen Zhang, Chunyun Zhang, Yumo Yao, Meng Chen, and Yuling Ma. Model-agnostic counterfactual reasoning for identifying and mitigating answer bias in knowledge tracing. Neural Networks, 178:106495, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yao-Yuan Yang, Chi-Ning Chou, and Kamalika Chaudhuri. Understanding rare spurious correlations in neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.05189, 2022. Preprint.

- Ninareh Mehrabi, Fred Morstatter, Nripsuta Saxena, Kristina Lerman, and Aram Galstyan. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54(6):1–35, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cristina Conati, Kaśka Porayska-Pomsta, and Manolis Mavrikis. AI in education needs interpretable machine learning: Lessons from open learner modelling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.00154, 2018. Preprint.

- Ryan S. Baker and Aaron Hawn. Algorithmic bias in education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, pages 1–41, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Linqing Li and Zhifeng Wang. Calibrated q-matrix-enhanced deep knowledge tracing with relational attention mechanism. Applied Sciences, 13(4):2541, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Changqin Huang, Hangjie Wei, Qionghao Huang, Fan Jiang, Zhongmei Han, and Xiaodi Huang. Learning consistent representations with temporal and causal enhancement for knowledge tracing. Expert Systems with Applications, 239:123128, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhongyi He, Wang Li, and Yonghong Yan. Modeling knowledge proficiency using multi-hierarchical capsule graph neural network. Applied Intelligence, 52(8):8847–8860, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Khosravi, Simon Buckingham Shum, Guanliang Chen, Cristina Conati, Yi-Shan Tsai, Judy Kay, Simon Knight, Roberto Martinez-Maldonado, Shazia Sadiq, and Dragan Gašević. Explainable artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education, 153:103912, 2022.

- Mirka Saarela, Ville Heilala, Päivikki Jääskelä, Anne Rantakaulio, and Tommi Kärkkäinen. Explainable student agency analytics. IEEE Access, 9:137444–137459, 2021.

- Christoph Molnar. Interpretable machine learning. Lulu. com, 2020.

- Cynthia Rudin. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(5):206–215, 2019.

- Zachary C. Lipton. The mythos of model interpretability. Queue, 16(3):31–57, 2018.

- Ribana Roscher, Bastian Bohn, Marco F. Duarte, and Jochen Garcke. Explainable machine learning for scientific insights and discoveries. IEEE Access, 8:42200–42216, 2020.

- Joakim Linja, Joonas Hämäläinen, Paavo Nieminen, and Tommi Kärkkäinen. Feature selection for distance-based regression: An umbrella review and a one-shot wrapper. Neurocomputing, 518:344–359, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2022.10.024. [CrossRef]

- Shuanghong Shen, Qi Liu, Zhenya Huang, Yu Zheng, Mingyu Yin, Minjuan Wang, and Enhong Chen. A survey of knowledge tracing: Models, variants, and applications. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 17:1858–1879, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yujing Bai, Jiaqi Zhao, Tian Wei, Qiang Cai, and Lei He. A survey of explainable knowledge tracing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07279, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.07279. Preprint.

- Matthew J Page, Joanne E McKenzie, Patrick M Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C Hoffmann, Cynthia D Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M Tetzlaff, Elie A Akl, Sue E Brennan, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372:n71, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Neal R Haddaway, Alexandra M Collins, Deborah Coughlin, Stuart Kirk, and K. B. Wray. The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE, 10(9):e0138237, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Quan Nha Hong, Sergi Fàbregues, Gillian Bartlett, Felicity Boardman, Margaret Cargo, Pierre Dagenais, Marie-Pierre Gagnon, Frances Griffiths, Belinda Nicolau, Alicia O’Cathain, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4):285–291, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Fred Paas, Alexander Renkl, and John Sweller. Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1):1–4, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal Romero and Sebastián Ventura. Educational data mining: a review of the state of the art. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews), 40(6):601–618, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hengyuan Zhang, Zitao Liu, Chenming Shang, Dawei Li, and Yong Jiang. A question-centric multi-experts contrastive learning framework for improving the accuracy and interpretability of deep sequential knowledge tracing models. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sribala Vidyadhari Chinta, Zichong Wang, Zhipeng Yin, N Hoang, Matthew Gonzalez, Tai Le Quy, and Wenbin Zhang. Fairaied: Navigating fairness, bias, and ethics in educational AI applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.18745, 2024. Preprint.

- Zhiyu Chen, Wei Ji, Jing Xiao, and Zitao Liu. Personalized knowledge tracing through student representation reconstruction and class imbalance mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.06745, 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2409.06745. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Tarid Wongvorachan, Okan Bulut, Joyce Xinle Liu, and Elisabetta Mazzullo. A comparison of bias mitigation techniques for educational classification tasks using supervised machine learning. Information, 15(6):326, 2024.

- John Saint, Dragan Gašević, Wannisa Matcha, Nora’ayu Ahmad Uzir, and Alejandro Pardo. Combining analytic methods to unlock sequential and temporal patterns of self-regulated learning. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, pages 107–116, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Seif Gad, Sherif M. Abdelfattah, and Ghodai M. Abdelrahman. Temporal graph memory networks for knowledge tracing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.01836, 2024. Preprint.

- Younyoung Choi and Robert J. Mislevy. Evidence centered design framework and dynamic bayesian network for modeling learning progression in online assessment system. Frontiers in Psychology, 13:742956, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kenneth R Koedinger, Albert T Corbett, and Charles Perfetti. The knowledge-learning-instruction framework: Bridging the science-practice chasm to enhance robust student learning. Cognitive Science, 36(5):757–798, 2012.

- Dylan Slack, Sophie Hilgard, Emily Jia, Sameer Singh, and Himabindu Lakkaraju. Fooling LIME and SHAP: Adversarial attacks on post hoc explanation methods. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pages 180–186, 2020.

- Luciano Floridi, Josh Cowls, Monica Beltrametti, Raja Chatila, Patrice Chazerand, Virginia Dignum, Christoph Luetge, Robert Madelin, Ugo Pagallo, Francesca Rossi, et al. AI4People—an ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4):689–707, 2018.

- Zitao Liu, Teng Guo, Qianru Liang, Mingliang Hou, Bojun Zhan, Jiliang Tang, Weiqi Luo, and Jian Weng. pykt: A python library to benchmark deep learning based knowledge tracing models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.11460, 2022. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.11460. Preprint.

- James A Hanley and Barbara J McNeil. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (roc) curve. Radiology, 143(1):29–36, 1982.

- Nancy A. Obuchowski. Nonparametric analysis of clustered ROC curve data. Biometrics, 53(2):567–578, June 1997. ISSN 0006-341X. doi: 10.2307/2533958. [CrossRef]

- Qing Li, Xin Yuan, Sannyuya Liu, Lu Gao, Tianyu Wei, Xiaoxuan Shen, and Jianwen Sun. A genetic causal explainer for deep knowledge tracing. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yan Cheng, Gang Wu, Haifeng Zou, Pin Luo, and Zhuang Cai. A knowledge query network model based on rasch model embedding for personalized online learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Weizhong Zhao, Jun Xia, Xingpeng Jiang, and Tingting He. A novel framework for deep knowledge tracing via gating-controlled forgetting and learning mechanisms. Information Processing & Management, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hengyu Liu, Tiancheng Zhang, Fan Li, Minghe Yu, and Ge Yu. A probabilistic generative model for tracking multi-knowledge concept mastery probability. Frontiers of Computer Science, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sannyuya Liu, Jianwei Yu, Qing Li, Ruxia Liang, Yunhan Zhang, Xiaoxuan Shen, and Jianwen Sun. Ability boosted knowledge tracing. Information Sciences, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Song Cheng, Qi Liu, Enhong Chen, Kai Zhang, Zhenya Huang, Yu Yin, Xiaoqing Huang, and Yu Su. Adaptkt: A domain adaptable method for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Deliang Wang, Yu Lu, Zhi Zhang, and Penghe Chen. An efficient and generic method for interpreting deep learning based knowledge tracing models. IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Huazheng Luo, Zhichang Zhang, Lingyun Cui, Ziqin Zhang, and Yali Liang. An efficient state-aware coarse-fine-grained model for knowledge tracing. Knowledge-Based Systems, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shuanghong Shen, Zhenya Huang, Qi Liu, Yu Su, Shijin Wang, and Enhong Chen. Assessing student’s dynamic knowledge state by exploring the question difficulty effect. In Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Haoxin Xu, Jiaqi Yin, Changyong Qi, Xiaoqing Gu, Bo Jiang, and Longwei Zheng. Bridging the vocabulary gap: Using side information for deep knowledge tracing. Applied Sciences, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shuaishuai Zu, Li Li, and Jun Shen. CAKT: Coupling contrastive learning with attention networks for interpretable knowledge tracing. In IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Network, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aritra Ghosh, N. Heffernan, and Andrew S. Lan. Context-aware attentive knowledge tracing. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ghodai Abdelrahman, Qing Wang, AI Shaafi, S Ahmed, FT Sithil, and IEEE. Deep graph memory networks for forgetting-robust knowledge tracing. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Emiko Tsutsumi, Yiming Guo, Ryo Kinoshita, Maomi Ueno, S Yang, and L Guo. Deep knowledge tracing incorporating a hypernetwork with independent student and item networks. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shanghui Yang, Xin Liu, Hang Su, Mengxia Zhu, and Xuesong Lu. Deep knowledge tracing with learning curves. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dongqi Wang, Liping Zhang, Yubo Zhao, Yawen Zhang, Sheng Yan, and Min Hou. Deep knowledge tracking integrating programming exercise difficulty and forgetting factors. International Conference on Intelligent Computing, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Emiko Tsutsumi, Tetsurou Nishio, and Maomi Ueno. Deep-irt with a temporal convolutional network for reflecting students’ long-term history of ability data. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yu Lu, Deliang Wang, Penghe Chen, and Zhi Zhang. Design and evaluation of trustworthy knowledge tracing model for intelligent tutoring system. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hongyun Wang, Leilei Shi, Zixuan Han, Lu Liu, Xiang Sun, and Furqan Aziz. DF-EGM: Personalised knowledge tracing with dynamic forgetting and enhanced gain mechanisms. In International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seounghun Kim, Woojin Kim, HeeSeok Jung, and Hyeoncheol Kim. Dikt: Dichotomous knowledge tracing. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Linhao Zhou, Sheng hua Zhong, and Zhijiao Xiao. Discovering multi-relational integration for knowledge tracing with retentive networks. International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wei Zhang, Zhongwei Gong, Peihua Luo, and Zhixin Li. DKVMN-KAPS: Dynamic key-value memory networks knowledge tracing with students’ knowledge-absorption ability and problem-solving ability. IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fei Wang, Zhenya Huang, Qi Liu, Enhong Chen, Yu Yin, Jianhui Ma, and Shijin Wang. Dynamic cognitive diagnosis: An educational priors-enhanced deep knowledge tracing perspective. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qi Liu, Zhenya Huang, Yu Yin, Enhong Chen, Hui Xiong, Yu Su, and Guoping Hu. EKT: Exercise-aware knowledge tracing for student performance prediction. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yanjun Pu, Fang Liu, Rongye Shi, Haitao Yuan, Ruibo Chen, Tianhao Peng, and Wenjun Wu. ELAKT: Enhancing locality for attentive knowledge tracing. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst., 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Cai, L. Li, and LM Watterson. Enhanced knowledge tracing via frequency integration and order sensitivity. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ming Yin and Ruihe Huang. Enhanced knowledge tracing with learnable filter. In 2024 4th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zitao Liu, Qiongqiong Liu, Jiahao Chen, Shuyan Huang, Boyu Gao, Weiqing Luo, and Jian Weng. Enhancing deep knowledge tracing with auxiliary tasks. In The Web Conference, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xiaopeng Guo, Zhijie Huang, Jie Gao, Mingyu Shang, Maojing Shu, and Jun Sun. Enhancing knowledge tracing via adversarial training. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yan Zhao, Huanhuan Ma, Wentao Wang, Weiwei Gao, Fanyi Yang, and Xiangchun He. Exploiting multiple question factors for knowledge tracing. Expert systems with applications, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Juli Zhang, Ruoheng Xia, Qiguang Miao, and Quan Wang. Explore bayesian analysis in cognitive-aware key-value memory networks for knowledge tracing in online learning. Expert systems with applications, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jinze Wu, Zhenya Huang, Qi Liu, Defu Lian, Hao Wang, Enhong Chen, Haiping Ma, and Shijin Wang. Federated deep knowledge tracing. Web Search and Data Mining, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Danial Hooshyar, Yueh-Min Huang, and Yeongwook Yang. Gamedkt: Deep knowledge tracing in educational games. Expert systems with applications, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhijie Liang, Ruixia Wu, Zhao Liang, Juan Yang, Ling Wang, and Jianyu Su. GELT: A graph embeddings based lite-transformer for knowledge tracing. PLoS ONE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wei Yanyou, Guan Zheng, Wang Xue, Yan Yu, and Yang Zhijun. Global feature-guided knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 2024 16th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hiromi Nakagawa, Yusuke Iwasawa, and Yutaka Matsuo. Graph-based knowledge tracing: Modeling student proficiency using graph neural networks. In IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Xinhua Wang, Shasha Zhao, Lei Guo, Lei Zhu, Chaoran Cui, and Liancheng Xu. Graphca: Learning from graph counterfactual augmentation for knowledge tracing. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sannyuya Liu, Shengyingjie Liu, Zongkai Yang, Jianwen Sun, Xiaoxuan Shen, Qing Li, Rui Zou, and Shangheng Du. Heterogeneous evolution network embedding with temporal extension for intelligent tutoring systems. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Haiqin Yang and L. Cheung. Implicit heterogeneous features embedding in deep knowledge tracing. Cognitive Computation, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Chen, Zitao Liu, Shuyan Huang, Qiongqiong Liu, and Weiqing Luo. Improving interpretability of deep sequential knowledge tracing models with question-centric cognitive representations. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jia Xu, Xinyu Huang, Teng Xiao, and Pin Lv. Improving knowledge tracing via a heterogeneous information network enhanced by student interactions. Expert systems with applications, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shilong Shu, Liting Wang, and Junhua Tian. Improving knowledge tracing via considering students’ interaction patterns. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ting Long, Jiarui Qin, Jian Shen, Weinan Zhang, Wei Xia, Ruiming Tang, Xiuqiang He, and Yong Yu. Improving knowledge tracing with collaborative information. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, X. Zhu, Y. Ji, J Li, MG Newman, and JZ Wang. Input-aware neural knowledge tracing machine. Lecture notes in computer science, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liangliang He, Xiao Li, Pancheng Wang, Jintao Tang, and Ting Wang. Integrating fine-grained attention into multi-task learning for knowledge tracing. World wide web (Bussum), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhanxuan Chen, Zhengyang Wu, Qiuying Ye, and Yunxuan Lin. Interaction sequence temporal convolutional based knowledge tracing. Lecture notes in computer science, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jianwen Sun, Fenghua Yu, Qian Wan, Qing Li, Sannyuya Liu, and Xiaoxuan Shen. Interpretable knowledge tracing with multiscale state representation. In The Web Conference, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hanshuang Tong, Zhen Wang, Yun Zhou, Shiwei Tong, Wenyuan Han, and Qi Liu. Introducing problem schema with hierarchical exercise graph for knowledge tracing. In Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiangyu Song, Jianxin Li, Yifu Tang, Taige Zhao, Yunliang Chen, and Ziyu Guan. JKT: A joint graph convolutional network based deep knowledge tracing. Information Sciences, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jianguo Pan, Zhengyang Dong, Lijun Yan, and Xia Cai. Knowledge graph and personalized answer sequences for programming knowledge tracing. Applied Sciences, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wenbin Gan, Yuan Sun, Yi Sun, and HG He. Knowledge interaction enhanced sequential modeling for interpretable learner knowledge diagnosis in intelligent tutoring systems. Neurocomputing, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jinseok Lee and D. Yeung. Knowledge query network for knowledge tracing: How knowledge interacts with skills. International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wenbin Gan, Yuan Sun, Yi Sun, JM Jiang, and Y Liu. Knowledge structure enhanced graph representation learning model for attentive knowledge tracing. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yongkang Xiao, Rong Xiao, Ning Huang, Yixin Hu, Huan Li, Bo Sun, and AK Roy. Knowledge tracing based on multi-feature fusion. Computing and Informatics, 2023.

- Bihan Xu, Zhenya Huang, Jia-Yin Liu, Shuanghong Shen, Qi Liu, Enhong Chen, Jinze Wu, and Shijin Wang. Learning behavior-oriented knowledge tracing. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chunpai Wang, Siqian Zhao, and Shaghayegh Sherry Sahebi. Learning from non-assessed resources: Deep multi-type knowledge tracing. Educational Data Mining, 2021.

- Shuanghong Shen, Qi Liu, Enhong Chen, Zhenya Huang, Wei Huang, Yu Yin, Yu Su, and Shijin Wang. Learning process-consistent knowledge tracing. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jiajun Cui, Hong Qian, Bo Jiang, and Wei Zhang. Leveraging pedagogical theories to understand student learning process with graph-based reasonable knowledge tracing. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Menglin Zhu, Liqing Qiu, and Jingcheng Zhou. Meta-path structured graph pre-training for improving knowledge tracing in intelligent tutoring. Expert systems with applications, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suojuan Zhang, Jie Pu, Jing Cui, Shuanghong Shen, Weiwei Chen, Kun Hu, and Enhong Chen. MLC-DKT: A multi-layer context-aware deep knowledge tracing model. Knowledge-Based Systems, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lixiang Xu, Zhanlong Wang, Suojuan Zhang, Xin Yuan, Minjuan Wang, and Enhong Chen. Modeling student performance using feature crosses information for knowledge tracing. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Unggi Lee, Yonghyun Park, Yujin Kim, Seongyune Choi, and Hyeoncheol Kim. Monacobert: Monotonic attention based convbert for knowledge tracing. Lecture notes in computer science, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shuanghong Shen, Enhong Chen, Qi Liu, Zhenya Huang, Wei Huang, Yu Yin, Yu Su, and Shijin Wang. Monitoring student progress for learning process-consistent knowledge tracing. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tao Huang, Xinjia Ou, Huali Yang, Shengze Hu, Jing Geng, Zhuoran Xu, and Zongkai Yang. Pull together: Option-weighting-enhanced mixture-of-experts knowledge tracing. Expert systems with applications, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xiaoshan Yu, Chuan Qin, Dazhong Shen, Shangshang Yang, Haiping Ma, Hengshu Zhu, and Xingyi Zhang. RIGL: A unified reciprocal approach for tracing the independent and group learning processes. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huan Dai, Yue Yun, Yupei Zhang, Rui An, Wenxin Zhang, and Xuequn Shang. Self-paced contrastive learning for knowledge tracing. Neurocomputing, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Qi Song and Wenjie Luo. SFBKT: A synthetically forgetting behavior method for knowledge tracing. Applied Sciences, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhengyang Wu, Li Huang, Qionghao Huang, Changqin Huang, Yong Tang, M Ahmad, and S Alanazi. SGKT: Session graph-based knowledge tracing for student performance prediction. Expert Systems with Applications, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yuling Ma, Peng Han, Huiyan Qiao, Chaoran Cui, Yilong Yin, Dehu Yu, and AS García. SPAKT: A self-supervised pre-training method for knowledge tracing. IEEE Access, 2022.

- Jia Zhu, Xiaodong Ma, and Changqin Huang. Stable knowledge tracing using causal inference. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhanxuan Chen, Zhengyang Wu, Yong Tang, and Jinwei Zhou. TGKT-based personalized learning path recommendation with reinforcement learning. Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhiyi Duan, Xiaoxiao Dong, Hengnian Gu, Xiong Wu, Zhen Li, and Dongdai Zhou. Towards more accurate and interpretable model: Fusing multiple knowledge relations into deep knowledge tracing. Expert Systems with Applications, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| I1 The year of publication includes studies from 2015 to 2025 |

| I2 Publications from conferences or peer-reviewed journals |

| I3 Written in English and full text accessible |

| I4 Focuses on deep knowledge tracing models |

| Exclusion criteria |

| E1 Study without evaluations: lacks validation or empirical studies |

| E2 Conference publications outside the main conference (e.g., short papers, posters), theses, or inaccessible full text |

| E3 The study focuses exclusively on classical (non-deep) knowledge tracing methods |

| E4 Applications of existing DKT frameworks without novel contributions |

| E5 Studies with insufficient methodological detail regarding model architecture or evaluation |

| E6 Studies not adequately addressing methodological challenges in educational contexts |

| Sequential stability approach | Papers | % | Typical techniques | Paper IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not evaluated | 13 | 15.5% | — | 1, 8, 11, 18, 21, 35, 36, 37, 44, 51, 55, 73, 76 |

| Qualitative visualization / examples | 62 | 73.8% | Heat-maps or illustrative mastery-trajectory plots | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 74, 75, 78, 79, 81, 82, 83, 84 |

| Quantitative stability metrics | 3 | 3.6% | Prediction waviness, -norm fluctuations, temporal-consistency coefficient | 29, 30, 77 |

| Forgetting / decay analysis | 5 | 6.0% | Forgetting-curve tracking and decay-aware proficiency plots | 2, 15, 16, 19, 65 |

| Sensitivity / robustness analysis | 1 | 1.2% | Perturbation-based sensitivity analysis | 80 |

| Interpretability approach | Papers | % | Typical techniques | Paper IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not considered | 74 | 88.1% | — | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84 |

| Interpretable architecture (IRT / rule-based layer) | 1 | 1.2% | IRT prediction layer; concept-level factorisation; rule-based gating | 60 |

| Feature attribution / attention analysis | 8 | 9.5% | SHAP, attention-weight analyses, Grad-CAM visualisations | 1, 8, 11, 19, 21, 31, 70, 71 |

| Embedding or trajectory visualisation | 1 | 1.2% | t-SNE plots of knowledge embeddings to reveal skill clusters | 46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).