1. Introduction

In the last few years, Internet of Things (IoT) has been gaining significant traction and proliferation especially in domestic environments. Marketed as "Smart Home" systems, IoT platforms aim to automate the operation of common household appliances and make controlling them more convenient. IoT products targeted at the consumer market are typically connected via a remote cloud-hosted server, commonly run by the device manufacturer. These online services offer limited interfaces for the end user to control their devices - often no more than a manufacturer-provided proprietary smartphone app, sometimes accompanied by voice control services. While this implementation - at least initially - satisfies the use cases of some customers, a multitude of users wish to control their devices fully locally within their own home network, without the need to connect to an external server hosted on the public Internet. However, most commercially available IoT devices do not offer such an application programming interface (API) to facilitate local control, instead running a closed-source device firmware that makes control possible solely via the aforementioned manufacturer cloud service and associated apps.

There are a multitude of reasons why a user may prefer to control their devices locally, of which some of the most prominent are outlined below:

Firstly, all security considerations are constrained to the network to which the device is connected and its immediate physical vicinity. While refraining from connecting to any external server alone does not adequately protect a device, it significantly reduces the number of possible attack vectors. Even if a manufacturer takes care to implement state-of-the-art security measures, regular updates might not be provided down the line, or they may not be installed by users. Given that device firmware, the control software used on cloud servers and end-user apps are all commonly proprietary, it becomes impossible to independently ascertain that the application contains no critically exploitable bugs or even deliberate backdoors. In contrast, open source software allows the user to verify and - if desired - modify the codebase. This allows for independent review, thus it is no longer a necessity to put unconditional trust in the manufacturer - both in their ability to produce safe, bug-free code and in their benevolence - to allow their device to connect to one’s internal network. However, even in the suboptimal case that device firmware is closed source, the existence of a feasible local control mechanism makes it possible to block the device from connecting to the Internet, which significantly limits the possible attack surface to exploit the device or even gain unauthorized access to the internal network itself.

Privacy is another common concern. Remotely controlled IoT devices usually require registering an account with the manufacturer, necessitating the disclosure of personally identifiable data, commonly at least an e-mail address. This puts the user at risk in the event the IoT control server is compromised. Particularly, their e-mail address might be exposed to third parties, which could lead to spam and phishing attacks. Ensuring an appropriate level of privacy protection is particularly essential with devices capable of recording and monitoring highly personal living spaces in a home, such as security cameras and voice assistants.

Furthermore, if storage in the server’s database is not implemented according to best practices, the user’s credentials - most commonly a password - might be trivial to obtain, a particular concern in case users re-use the same password on multiple services.

Another reason to prefer local control is

latency. Sending a network packet within one’s local network is typically accomplished within less then

, which is perceived as instant to the user. Contrast this with a remote manufacturer server that may be in another country, where sending the same packet may take about half a second. The user-perceived responsiveness of the device is severely impacted, as the minimum perceivable latency is only

at most (cmp. [

1] p. 32).

Availability is another major concern. If the IoT control server is unreachable or the user’s internet connection is disrupted, control of the devices is not possible.

Another essential factor is

longevity. After an IoT product has reached the end of its commercial availability, the manufacturer might opt to disable servers or support for that device. This could also occur due to manufacturer bankruptcy. If the remote IoT control server ceases to function, the device is not controllable and depending on its design, severely limited in its functionality or rendered entirely inoperable. An example for this are home security cameras and systems by Nest Secure, which have been disabled in April 2024[

2]. Such shutdowns are not only costly for the user, since they have to replace the device, but it is also unsustainable for the environment to dispose of a device in physically perfect working order merely because the means of controlling it no longer function.

Flexibility is another advantage. With a sufficiently open local API, advanced automation via software like Home Assistant or other custom integrations becomes a straightforward possibility. Such options are typically severely limited with proprietary servers. This often results in vendor lock, where a user is unable to automate a process despite owning hardware that has the technical capability to do so. As a simple example, consider a motion detector and a light. If only one of these two devices uses a proprietary app and there is no way to interface with it over a common API or compatibility adapter, even a simple automation use case such as turning on the light if motion is detected can not be implemented using these components. This example highlights the importance of open - and preferably local - APIs, as they are a base prerequisite for effective home automation. Without such basic provisions for interoperability, deeming IoT devices "smart" may be considered an overstatement.

Remote access is one of the key reasons manufacturers often opt for preferring remote server control over local control. It is a selling point to be able to e.g. turn on the heat at home before one leaves work, or check that all the lights are off after leaving the house. However, remote and local control APIs are not mutually exclusive, so a decision to not offer a local API might be due to manufactures desiring a higher degree of control or reducing implementation complexity by foregoing the need for e.g. an embedded webserver on the device. Philips Hue is a positive example for a large scale IoT ecosystem that offers both remote and local APIs.

Ownership of hardware should empower users to use the device as they see fit. The possibility for local control is essential to a non-revokable freedom of use.

1.1. Methods to Proliferate Local Control

In 2024, the

Open Home Foundation was created to facilitate the goals of

privacy,

choice and

sustainability (cmp. [

3]) with the vision of enabling a truly open and local smart home system. The WLED project, which will be used for the main example implementations in this work, is also a member of the Open Home Foundation.

Open source software is a key element in making IoT devices more accessible - including local control. When a device runs an open source firmware, users are free to customize its software behavior to their specific needs, which can include adding APIs to enable local control.

Consumer behavior is essential for a long-term improvement of implemented IoT solutions. If customers are sensitized to the issue and prefer purchasing devices that allow local control or are even fully open source, this is likely to influence manufacturer behavior to offer more flexible means to use their devices.

Web technology and in particular, JavaScript APIs present in modern browsers has evolved rapidly in the last few years, to the point where it is often feasible to replace proprietary native apps with open web-based apps that offer cross-platform compatibility with almost all Internet-connected end user devices that have a standard web browser installed. This could be expanded further in the future to offer built-in non-TLS means for browsers to communicate securely with low resource locally connected IoT devices.

The goal of this research is to identify and analyze methods for offering a secure local means of control for constrained IoT devices, with particular focus on browser-based web apps, i.e. without requiring the installation of custom software on client control devices. As an implementation example, the ESP8266 and ESP32 microcontrollers by Espressif are considered due to their widespread use both in home-made and commercial IoT devices. For demonstration, the open source lighting control project WLED is used - see

Section 3.8.

2. Materials and Methods

In the following, firstly the technical background is given in

Section 3. Furthermore, the novel approach for secure and lightweight browser-based device control is outlined in

Section 4.

3. Technical Background

Herein, fundamental concepts used for the subsequent implementation are outlined and the necessary prerequisites established, which encompass both the security objectives the solution aims to achieve as well as the possible ways to implement cryptographic protection measures in a web browser context.

3.1. Web-Based Apps as an Alternative to Native Apps and Browser-Based Cryptography

In order to successfully design a secure local IoT system controlled exclusively via a web app running in a standard browser, it is first necessary to gather an overview of the cryptographic functionalities present in modern browsers and their associated limitations.

The primary means of control for most commercially available IoT devices for home use are native smartphone applications. While major mobile operating system software development kits (SDKs) offer a high degree of flexibility for the application developer in the interfaces and device features they can utilize, they can have drawbacks for the end user. Since the source code is typically not accessible, users have to trust manufacturers and distributors not to abuse the power granted to them. Both modern operating systems and browsers implement a permission system to let the user decide which device functionality and data the app or website is allowed to access. A key problem with this system is that it is often not clear to the user why and in which scope particular permissions are required for the app to function; the choice given to them is often not granular enough. A specific example pertinent to IoT control apps is location access. Many Wi-Fi-based devices open an access point (AP) for initial setup. The app then scans for and connects to this AP to provision the device with the credentials for the user’s home Wi-Fi network. In recent versions of Android, the location permission is required to connect to Wi-Fi networks within the app, as network SSIDs could theoretically be referenced against publicly available SSID maps such as WiGLE and thus a likely location of the user inferred. Therefore, granting the location permission is often required for initial device setup. However, this allows the app to store the location of the user during setup or even to continually track them, which constitutes data collection that for most categories of smart home devices (such as lights, air conditioning, and cameras) is not strictly necessary and thus not only fails to adequately protect the users privacy, but also risks non-compliance with laws enacted to protect individual privacy, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU.

If control of an IoT device from user end devices is desired without requiring additional apps, web browsers can be a viable choice. Virtually all computers and smartphones and sometimes even more specialized devices such as e-book readers have modern browsers pre-installed. CSS offers a rich toolkit to create visually appealing user interfaces and JavaScript offers the majority of features needed to implement client-side logic - to the point that many natively installable apps are merely wrappers around a web page. This approach is used by the WLED project as well as other widely used applications such as the chat platform

Discord. An even more lightweight alternative are progressive web apps (PWA), which appear like native apps to the user - for instance by having a dedicated app icon, running full-screen without visible browser UI, and being able to run offline using caching[

4]. Additionally, the client-side code of a website or PWA is in most cases open source by definition, as JavaScript is an interpreted language that is executed directly from the corresponding source code. While code obfuscation and minification - that is, removing formatting and comments and shortening variable and function names - are possible and often advisable to reduce the size of the page when transferred over the network, such minified JavaScript can still be analyzed and customized more readily than an assembled and packaged binary application. Another feature built into modern browsers that is highly useful for secure local IoT control is the

Web Crypto subtle API, which implements select cryptographic primitives for in-browser use. However, particularly with devices that do not support transport encryption, one first has to carefully consider whether cryptography code downloaded from the device’s embedded web server and executed in the browser can be trusted.

3.2. Secure JavaScript Cryptography Code from Untrusted Origins

There is a theory of the so-called "Browser Cryptography Chicken and Egg Problem"[

5], which states that "

if you can’t trust the server [or message transport] with your secrets, then how can you trust the server [or message transport] to serve secure crypto code?"[

6]. Essentially, in a server and client architecture without TLS, the web page is sent to the client unencrypted. In that case, there is no easy way for one to implement client side cryptographic mechanisms without TLS communication, as all page JavaScript comes from the server and could thus be subject to a Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attack. Therefore it is inherently untrustworthy and any trust in JavaScript code run on the client side would first need to be established using either built-in browser functionality, or external HTTPS servers.

Using external servers for download or verification of certain client-side code is less than ideal, as part of the availability and privacy concerns of full remote device control still apply. However it is still deemed preferable to remote control, as no user accounts are required and caching - such as possible when deployed as a PWA - may allow the solution to continue working in temporary offline conditions. Moreover, users could host such a server themselves on more performant hardware.

3.3. Secure Contexts in Browsers

An important consideration in browser-based cryptography are Secure Contexts. A multitude of powerful browser APIs are only available in Secure Contexts, i.e. when the page is loaded via TLS. This is meant to protect personal data, as access to potentially sensitive APIs, for example camera, location, or microphone, is denied. One notable API that is also only available in a Secure Context is the aforementioned Web Crypto subtle API, which provides cryptographic primitives and useful functions, for instance password-based key derivation (PBKDF2) and implementations of various hash functions. The Subtle Crypto API is only available in Secure Contexts likely due to the fact that, as outlined above, any client-side JavaScript transferred over HTTP is inherently insecure - at least without additional integrity checking of the downloaded JavaScript via trusted in-browser code. The Subresource Integrity feature of modern browsers supports checking the integrity of additionally downloaded JavaScript files against a hash provided in the integrity attribute of the <script> tag to be loaded. However, to the authors knowledge, such a built-in integrity check mechanism is not natively available for the root HTML page itself, therefore a trusted root page served over TLS is still required.

Furthermore, mixed content prohibition complicates interconnection between TLS and non-TLS servers: unsecured sites may fetch additional content from TLS servers, but the inverse is not true - browsers will in general block all unsecured HTTP requests from pages loaded via HTTPS. In the context of a non-TLS capable locally controlled IoT device, approaches such as loading the control interface HTML, stylesheets, and JavaScript from a TLS-enabled external server and only establishing an HTTP connection with the device for some API control commands are therefore not trivially possible.

3.4. Inter-Window Messaging

Even though a direct HTTP or unencrypted WebSocket connection to the device from a Secure Context is disallowed by modern browsers, indirect communication is possible under certain conditions. Two different browser windows that have a mutual reference can communicate with each other using the window.postMessage() API to send a message and the window.messageEvent API to listen for incoming messages.

Note that window refers to a independent page context here, it does not need to be a different browser window as seen by a user, but can also be e.g. a second tab. The reference to the other window can be made by e.g. loading the second window in an <iframe> element embedded in the first window (though unencrypted iframe content is also disallowed on secure pages) and also by opening the second window in a new tab programmatically, which makes a reference to the original window available via window.opener, thereby allowing the opened window to send an initial message. The window message API is even available if the two windows have different origins - which often means they are hosted on different servers - and, for the JavaScript cryptography use case crucially, when one window is a Secure Context and the other is not. This allows developers a controlled circumvention of enforced Secure Context constraints, as they can pass a message to the Secure Context window, let it process the message in a trusted environment using an API that is only available in a Secure Context, like Web Crypto, and then return the result to the untrusted window via messaging.

3.5. TLS-Less Client Authentication Mechanisms

For a server to be able to discern authorized from unauthorized users, i.e. clients, an authorized user is required to present proof of their authorization to the server. Using TLS, this proof can be a client certificate, however this is not an option without TLS. Most commonly, passwords are used for authentication, though they require both transport and storage protection measures against eavesdropping and subsequent misuse.

3.6. Deriving a Shared Key from the User Password

Most servers that employ transport layer security (TLS) rely on it to transmit the cleartext password and then carry out hashing operations within the server itself. This raises the question why password hashing is not more commonly done on the client side, so that the cleartext password is at no time exposed to the server. One likely explanation may trace back to the "Browser Cryptography Chicken and Egg Problem" in the stance that if the server can not be trusted to handle the password, it can also not be trusted to serve secure cryptographic code for client-side password hashing. Another reason may be to reduce complexity or the reliance on JavaScript on the client side, or to increase performance when combining a slow client device and an expensive password hashing algorithm.

In an IoT device context where TLS is not available, client-side password hashing becomes indispensable in order to avoid exposing the cleartext password during the unencrypted transmission between the browser and IoT device.

An option for password hashing built-in to browsers is

HTTP Digest access authentication. It allows for client side password hashing and subsequently avoiding sending the password in the clear without any use of JavaScript, however unfortunately it is susceptible to MitM attacks ([

7], sec. 5.8). Since the connection is unencrypted, the attacker can downgrade the authentication scheme to use

HTTP Basic access authentication, which transmits the password in cleartext with a simple Base64 encoding. This manipulation is not readily detectable to the end user since the HTTP authentication dialog is rendered identically regardless whether Basic or Digest authentication is in use. Furthermore, the appearance is not customizable by the page, but is always rendered as a generic popup login dialog as shown in

Figure 1.

On a page sent via unencrypted HTTP, the JavaScript Web Crypto API is not available as the window is not in a secure context, therefore neither the built-in password based key derivation (PBKDF2) can be used directly, nor can one implement their own algorithm directly in JavaScript or download it from an external server in a secure manner due to the "Browser Cryptography Chicken and Egg Problem".

3.7. Non-TLS Data Transport Security Mechanisms

In order to implement confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity protected message transport, full TLS is not unconditionally required. In particular, the asymmetric key exchange steps and required buffers drive up implementation complexity and memory requirements. In cases where use of a pre-shared key (PSK) is acceptable, asymmetric cryptography is no longer required and in principle, symmetric ciphers can be used directly. Some symmetric cipher suites that may be suitable in the context of IoT devices and JavaScript client implementations include the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and ChaCha20, which "is considerably faster than AES in software-only implementations, making it around three times as fast on platforms that lack specialized AES hardware" ([

8], p. 3), a property that is very useful on constrained devices with low processing power and without hardware support for AES. ACORN and Ascon are noteworthy families of symmetric ciphers that are designed to be particularly lightweight, with the latter being first choice in the 2019 CAESAR competition for symmetric ciphers in the category for lightweight ciphers[

9].

In applications where confidentiality is not required, data encryption can be omitted entirely, as for integrity and authenticity protection a cryptographically secure message authentication code (MAC) is sufficient. This increases performance compared to data encryption, as calculating a cryptographic digest (hash) of the data and authenticating it is typically significantly faster than encrypting the entire message.

A widely used MAC is HMAC. The integrity of a message can be asserted by the sender calculating and including the resulting hash in the transmission. The receiver, which also possesses the PSK, may now repeat this calculation, if the calculated hash matches the one included by the sender, it is valid and the receiver can be assured that the message has not been tampered with and originated from someone who knows the PSK.

3.8. Introduction to WLED

WLED (backronym: Wireless Lighting Effects Driver) is an open-source software project conceived and maintained by the author C. Schwinne since 2016, designed for the ESP8266 and ESP32 microcontroller series by Espressif Systems. It is engineered to drive a large quantity of digital individually addressable full-color LEDs; each LED may be set to a different color and brightness via a serial protocol and thus enables an abundance of different lighting effects. WLED has over a hundred built-in effect modes - from simple blinking, flickering candles and twinkling fairy lights up to complex visualizations intended to be displayed on a two-dimensional matrix of LEDs. WLED offers an easy-to-use and feature complete web based control user interface, additionally native mobile applications and smart home automation system integrations are available.

The primary interface for controlling a WLED instance from external hosts such as home automation software, but also from the included web-based user interface, is the WLED JSON API, which is publicly documented in detail (cmp. [

10]). For the scope of this work, it is important to note that the JSON API is available both via an HTTP endpoint (

/json) and via a WebSocket connection. WebSocket is a protocol for bi-directional messaging communication between an HTTP server and client based on a persistent TCP connection. It can thus be used to replace resource-heavy and high latency HTTP polling for receiving status updates from the server. The syntax of a WLED API command is a simple JSON object containing the keys to be set. For instance, the following command turns on the light and set it to approximately half brightness (

bri is an 8-bit value denoting the current overall brightness, which has a range of 0-255):

{

"on": true, "bri": 128

}

4. New Approach Methodology

This section describes how the components outlined in

Section 3 are combined to facilitate secure and lightweight control of devices via standard web browsers.

4.1. Hosting of Browser-Based Secure Cryptography

Due to the "Browser Cryptography Chicken and Egg Problem" outlined in

Section 3.2, doing most cryptographic operations or even just accepting input of a user password is fundamentally insecure on pages that have been loaded via HTTP only. Thus, to avoid this problem, facilitate secure message authentication, and ensure the user password is not transmitted over an insecure connection, a trusted execution environment is required. This could for instance be a page locally stored on the user device - although loading pages from downloaded HTML/JS source files is typically not implemented in browser apps for mobile devices and is also inconvenient for users. Alternatively, it could be hosted via HTTPS on a domain the user trusts (e.g.

https://rc.wled.me, or alternatively the user could host their own server running this page for cryptographic functionality, denoted as the "secure crypto tab" in the following.

A key goal of the system to be implemented is handling all cryptographic operations within the browser client, which has two advantages: Firstly, apart from initial WLED ESP provisioning, where the PBKDF2-derived pre-shared key needs to be stored on the ESP for HMAC verification, no secrets have to leave the user device. Secondly, a static web page is sufficient for hosting, which greatly simplifies deployment and allows hosting on e.g. GitHub Pages or an out-of-the-box Apache server without advanced configuration as would be necessary for a full server-side framework such as Django.

For the secure crypto tab to be able to connect to the WLED instance despite the browser’s mixed content prohibition, inter-window messaging is used as explained in

Section 3.4. The user is unable to control the light by directly visiting the address of the WLED instance, instead they need to open the secure crypto tab first and open the instance user interface through it. The abbreviated code for the initial window messaging handshake is given below:

wled00/data/index.js (WLED UI, ll. 250+):

function onLoad() {

//...

if (window.opener) {

window.opener.postMessage(

’{"wled-ui":"onload"}’, ’*’);

);

}

//...

}

WLED-SecureRemoteAccess/src/messages.ts (secure crypto tab):

export function handleMessageEvent(event : MessageEvent) {

//... origin verification, error handling

var json = JSON.parse(event.data)

if (json[’wled-ui’] === ’onload’) {

event.source!.postMessage(

’{"wled-rc":"ready"}’,

{’targetOrigin’:event.origin}

);

}

// handling other message types

}

wled00/data/index.js (WLED UI, ll. 315+):

function handleWindowMessageEvent(event) {

//... origin verification, JSON parsing

if (json[’wled-rc’] === ’ready’) {

useSRA = true;

sraWindow = event.source;

sraOrigin = event.origin;

}

}

In the first UI code block, note the second parameter ’*’ in the call to postMessage. This sends the message to any opener window, regardless of its origin, which is necessary since browsers do not allow access to window.opener.origin for privacy reasons. This is not ideal, since with no initial way of verifying the opener origin, a malicious site could hypothetically link to the control UI and eavesdrop on the control commands sent. However, this is a largely theoretical concern and could also be prevented by only allowing the rc.wled.me origin here, at the cost of preventing users from hosting the secure crypto tab themselves on a different origin. Once the reply to the handshake message by the secure crypto tab is received, event.origin is accessible though and can be used for custom filtering rules.

4.2. Technology Stack

The ESP-side code, which expands the functionality of WLED by HMAC verification capabilities, is written in C++. The cryptographic primitive implementations for SHA256 and HMAC are provided by the ESP8266 Crypto library, though the code is expected to be fully portable except for the ESP-specific random number generator implementation. It also provides an AES encryption implementation that may be useful in case the implementation is to be modified to offer confidentiality protection. Being contained in a single source file Crypto.cpp that is below 1.000 lines of code, it is easy to independently analyze.

The WLED web UI functionality is implemented in a single JavaScript file, index.js.

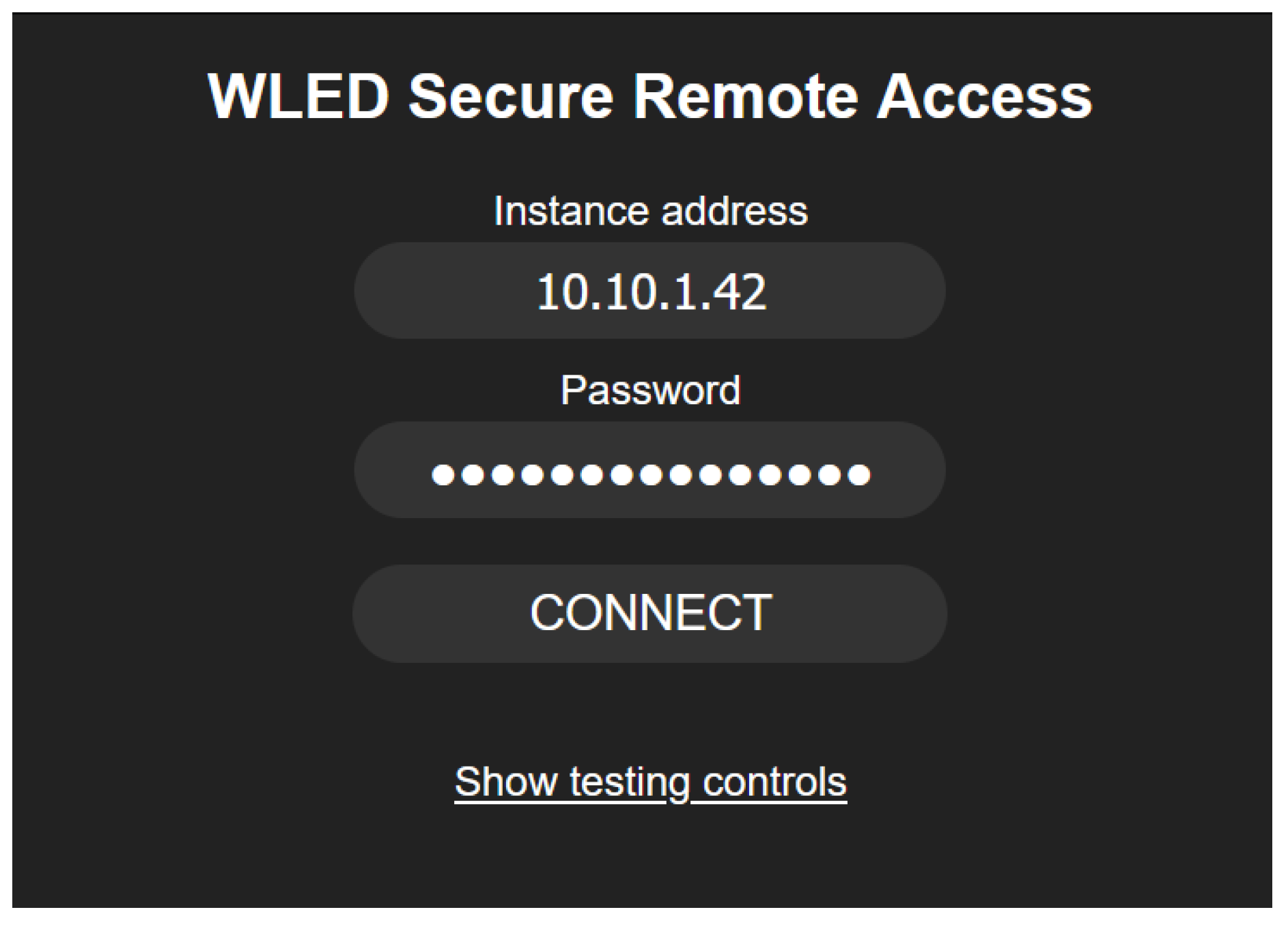

For the secure crypto tab, which implements all in-browser cryptographic operations, a TypeScript project is used that relies on modules to improve code structure. JavaScript modules allow for more efficient implementation of object-oriented programming concepts by for instance requiring all public functions of a module to be explicitly exported for use in other modules. Other functions are private by default. TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript that adds static typing and thus enables type checking. The

Vite build tool is used to transpile the modules back to JavaScript that can be executed in standard browsers and merge them into a single file again. The user-facing appearance of the secure crypto tab is shown in

Figure 2.

4.3. PBKDF2-Based PSK Derived from User Password

In order to avoid a potential unencrypted transmission of cleartext passwords between the browser and ESP, only a hash of the password is ever transmitted outside of the secure crypto tab. The

PBKDF2 algorithm is chosen, as it is the only algorithm available in the Web Crypto API that is suitable for deriving keys from low-entropy passwords (cmp. [

11]). Newer hashing algorithms designed to be used for passwords, for example

Argon2id would be preferable as it is more resistant to GPU (graphics processing unit) and ASIC (application specific integrated circuit) supported attacks by requiring the utilization of a large amount of system memory (cmp. [

12], sec. 4).

4.4. Generation of the MAC

The Web Crypto API is also used for generation of the HMAC message authentication code. The TypeScript function utilized for HMAC generation is given below - note that for brevity and readability, some non-critical lines are omitted:

WLED-SecureRemoteAccess/src/crypto.ts (secure crypto tab):

async function generateHMAC

(message: string, key: CryptoKey) : Promise<string>

{

const messageBuffer = new TextEncoder().encode(message);

const sig = await crypto.subtle.sign(’HMAC’, key, messageBuffer);

return Array.from(new Uint8Array(sig)).map(function(byte) {

return (’0’ + (byte & 0xFF).toString(16)).slice(-2);

}).join(’’);

}

This function is a good example for how the Web Crypto API can be used. Calling the primitives is usually accomplished by a single line, though some setup code is needed, particularly to set parameters correctly and to convert formats, as the Web Crypto API only operates on byte buffers (Uint8Array in TypeScript). The last three lines of code in the function merely convert the returned HMAC to a hexadecimal string for sending it to the ESP over the network.

4.5. Transport of the HMAC

After authenticating a JSON message, the HMAC is to be sent along the message in order for the receiver to be able to verify that the sender is in possession of the pre-shared key by calculating the HMAC of the message itself and comparing it to that sent along with the message. There are multiple ways to implement such data transfer with an associated authentication code, most relavant for the application in WLED are JSON payloads either over HTTP or WebSocket. In a pure HTTP environment where JSON API commands are transmitted via a HTTP POST request, a straightforward implementation method would include the HMAC as an HTTP header, separate from the JSON payload sent in the POST request. However, this approach is not possible when using a WebSocket connection, as this is just a persistent TCP connection allowing for bi-directional messaging. Thus, the HMAC needs to be integrated into the message itself. For this purpose, the WLED JSON API calls are be wrapped, for this the following JSON syntax is chosen:

{

"mac": "baddecafc0ffee[...]",

"msg": {

"on": true,

"n": {"sid":"5e55101d[...]","c":41}

}

}

Here, the msg object ({"on":true}) is the original API command, in this case to turn on the lights. An additional key n is added, this is a session ID and counter-based nonce used to prevent replay attacks. This is wrapped in another JSON object that also contains a string value mac containing the HMAC of the API command encoded as a hexadecimal string.

4.6. Verification of the HMAC

The verification of the HMAC itself - without nonce validation for replay attack mitigation - is simply implemented by re-calculating the HMAC of the message data and comparing it to the MAC sent along with the message.

It is crucial that the nonce is included within the HMAC-authenticated message; if it was sent alongside the message, an attacker could tamper with the nonce without invalidating the MAC.

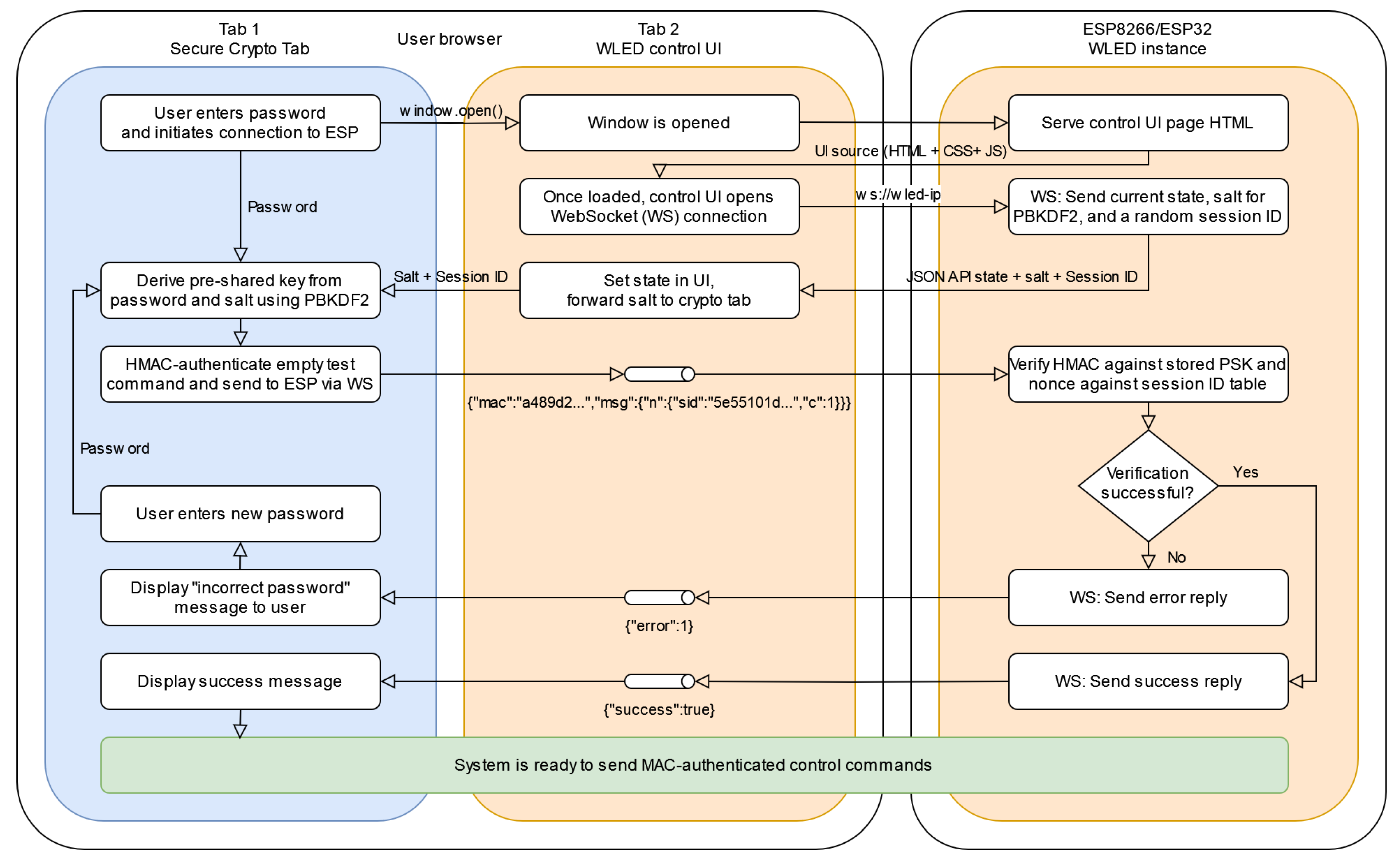

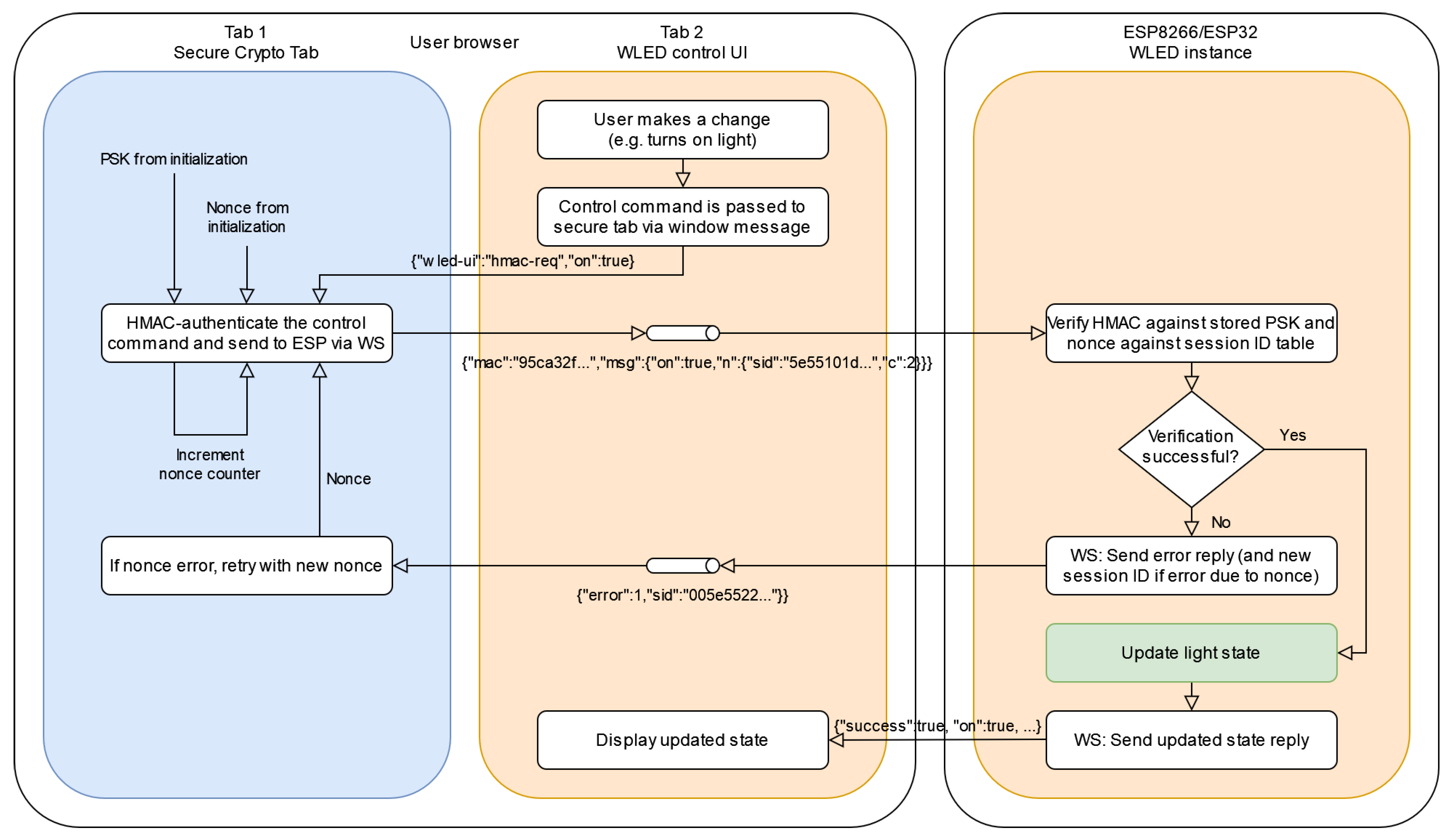

4.7. Communication Flow

The implemented system consists of three codebase components running independently: the secure crypto tab, the user interface tab, and the WLED firmware running on the IoT device.

There are two core interactions between the components - the initial login authentication and subsequent authentication of control commands. Both core interactions are visualized below.

Figure 3 shows the initial login process, while

Figure 4 outlines the control commands authentication process. The "pipe" symbol in the UI tab denotes gateway functionality - the UI tab does not process the message itself, but just forwards it from the secure crypto tab to the ESP or vice versa, changing the message transport protocol from window messaging to WebSocket or back from WebSocket to window messaging, respectively.

5. Results

The implemented PoC successfully uses browser inter-window messages to facilitate communication between a trusted client environment (Secure Context) and an IoT client device connected via insecure HTTP.

5.1. Resource Utilization

For a security solution for resource-constrained embedded devices to be viable in practice, it does not only need to be able to operate within the memory and computing resources available, but also leave enough resources available for the application logic to run. Especially in the case of more complex use cases - such as WLED hosting a full web server and lighting effects engine designed to drive hundreds of individual LEDs on the ESP8266 platform with just 80 kB of available user data memory - keeping the memory usage to a minimum is a crucial requirement. The additional memory usage of the HMAC functionality implemented on the ESP-side using the SHA256 hash based on the ESP8266 Crypto library is determined by comparing the memory usage of a build - of the revision with the commit hash f3429a6c that has the demo implementation integrated - with build of the base WLED software at the point of the commit with hash 6dc2c680, on which the implemented demo was based. The ESP8266 is considered, as in contrast to the ESP32 platforms - due to their significantly higher amount of available memory - optimization is essential. Both the static RAM usage as well as the flash utilization, which is equal to the compiled binary size of the firmware, are considered. As the static RAM usage merely includes static variables allocated at compile time, but not dynamic data allocated at runtime (e.g. with malloc or the C++ new keyword), in addition the free heap memory after a reboot of the microcontoller is considered, as it denotes the available memory after persistent dynamic variables - for example the buffer holding the color of each addressed LED - have been allocated.

It can be observed that static RAM use only increased by 280 bytes over build by implementing HMAC-SHA256 in build . The free heap memory decreased by approximately 600 bytes, though this value is subject to fluctuation due to factors like network packet caching. The compiled binary increases in size by 14 kB.

6. Discussion

In the following, several aspects of the implementation are reflected upon and analyzed in terms of their advised usability in production systems and their long-term safety against quantum computing algorithms.

6.1. Secure Production Deployment of the Implemented Solution

While the architecture drafted and implemented in the above was continuously scrutinized on a best faith effort to be secure, it should strictly be considered a demo implementation for research and testing purposes only. The authors do not guarantee the security of the implemented solution and it should only be used in practical applications once thoroughly and independently verified. Although only known and well-vetted cryptographic primitives are implemented, custom cryptographic system designs are easily prone to subtle errors that render the entire system ineffective - one example for an aspect that is not immediately obvious but essential for the security of the design is the nonce-based replay attack mitigation for HMAC-based message authentication schemes.

6.2. Post-Quantum Cryptography Considerations

There are currently no indications that state-of-the-art symmetric ciphers, such as AES-256, or MAC-based approaches, such as implemented in this work, would be meaningfully reduced in their security value by quantum-based approaches; they are therefore deemed quantum-resistant (cmp. [

13], p. 11). Thus, given the current state of research, unlike for instance current TLS implementations, the security of the implemented solution is likely to remain unaffected by the availability of powerful quantum computing resources, which is particularly important with embedded systems such as used in IoT devices, as they are typically in use for significantly longer periods of time than conventional IT hardware.

6.3. Potential for MitM Command Injections

While the implemented solution demonstrates that implementing hash-based security measures is highly feasible on constrained devices with limited resources such as the ESP8266, there are some use cases and limitations not addressed by the current implementation yet.

While the implemented system already significantly raises the transport security value and makes it more difficult for unauthorized parties to send valid unauthorized commands, there is still a significant risk for MitM attacks allowing for MAC verification of unauthorized commands - which again has its root in the "Browser Cryptography Chicken and Egg Problem". Although the implemented system delegates the relevant cryptographic operations to the secure crypto tab, all commands to be authenticated still originate from the untrusted control UI that is loaded from the ESP web server via insecure HTTP. This would allow the attacker to insert arbitrary control commands into the UI page source that could automatically be authenticated by the HMAC generation in the secure crypto tab and pass the ESP-side HMAC verification as regular MAC-authenticated commands.

A possible way to address this problem is hosting the entire control UI in the secure crypto tab, which would ensure no MitM command injection would be possible. The page loaded from the ESP web server over the insecure HTTP connection would be reduced to acting as a gateway that receives the window message from the secure crypto tab and passing it to the ESP via the WebSocket connection. This approach has one drawback, namely the secure crypto tab must have a version of the UI available that is API-compatible with the WLED version installed on the ESP. While this may be straightforward for standard builds, it would once again make it difficult for developers of custom features to have their version of the UI used by the secure crypto tab. This problem could be in part alleviated by allowing the ESP to specify a URL where a compatible version of the UI is hosted. While this approach requires retrieving the UI code via that URL and incurs the associated limitations regarding availability of online services, this URL could be part of the ESP-side firmware and also be protected against MitM URL replacement attacks using an HMAC generated on the ESP side.

7. Conclusions

In the course of this research, alternative methods for securing the control command communication between the user browser and IoT device were identified, aiming to be more lightweight than a TLS server implementation. It was found that approaches involving purely symmetric ciphers with a pre-shared key can be feasible depending on the requirements of the specific application. Furthermore, message authentication codes are a viable option in cases where message integrity and authenticity protection are required, but confidentiality protection is not needed, which greatly reduces the amount of necessary computation and memory resources that would be needed for encipherment and decryption; and thus is an excellent candidate for implementation on constrained devices that do not handle sensitive data. As the WLED software meets these criteria, an HMAC-based command message authentication scheme was successfully realized in a proof-of-concept demonstrator implementation that uses particularly few resources - less than a kilobyte of additional RAM usage was observed for the HMAC functionality. Moreover, novel methods to securely use cryptographic functionality in client browsers - even when the connection to the IoT device itself is untrusted - were designed. This results in an overall more user-friendly implementation compared to a direct TLS server.

Conclusively, despite undebatable hurdles faced by system designers when designing local control schemes that are to both interoperate fully with standard browsers and be functional on resource constrained devices, the work demonstrated that a practically usable and secure implementation of a lightweight web-based local IoT control system is definitely feasible. Once further refined and more widely deployed, a similar solution to that implemented herein has the potential to elevate the IoT ecosystem towards a vision that enables complete privacy, choice and sustainability for device owners.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give credit to Michal Madziar of Doyensec, who in 2021 gave a security advisory on a buffer over-write vulnerability in the WLED API and sparked the idea to add a message authentication scheme to the WLED software. The authors have not used any GenAI tools during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AES |

Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AP |

Access Point |

| ASIC |

Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| CSS |

Cascading Style Sheets |

| ESP |

Microcontroller series by Espressif Systems |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| (H)MAC |

(Hash-based) Message Authentication Code |

| HTML |

HyperText Markup Language |

| HTTP(S) |

HyperText Transfer Protocol (Secure) |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IT |

Information Technology |

| JSON |

JavaScript Object Notation |

| LED |

Light-Emitting Diode |

| MitM |

Man-in-the-Middle (attack) |

| PBKDF2 |

Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2 |

| PoC |

Proof of Concept |

| PSK |

Pre-Shared Key |

| PWA |

Progressive Web App |

| RAM |

Random Access Memory |

| SDK |

Software Development Kit |

| TCP |

Transmission Control Protocol |

| TLS |

Transport Layer Security |

| UI |

User Interface |

| URL |

Uniform Resource Locator |

References

- Card, S.K.; Moran, T.P.; Newell, A. The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction; CRC Press, 1983.

- Google. Support for Nest Secure ended, 2024.

- Open Home Foundation. About us, 2024.

- MDN Web Docs. Progressive web apps.

- Ptacek, T. Javascript Cryptography Considered Harmful, 2011.

- Meixler Technologies Inc.. Browser Crypto, 2021.

- Shekh-Yusef, R.; Ahrens, D.; Bremer, S. HTTP Digest Access Authentication. RFC 7616, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Nir, Y.; Langley, A. ChaCha20 and Poly1305 for IETF Protocols. RFC 8439, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.J. CAESAR submissions, 2019.

- Schwinne, C.; et al. JSON API, 2024.

- MDN Web Docs. SubtleCrypto: deriveKey() method.

- Biryukov, A.; Dinu, D.; Khovratovich, D.; Josefsson, S. Argon2 Memory-Hard Function for Password Hashing and Proof-of-Work Applications. RFC 9106, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Preuß Mattsson, J.; Smeets, B.; Thormarker, E. Quantum-Resistant Cryptography, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).