1. Introduction

There is wide consensus within the scientific community that the world faces a sixth mass extinction with anthropogenic activities being the main driver [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Anthropogenic activities including resource extraction, land use change, vehicle traffic, extirpation and decreased fitness continue to threaten mammal populations as well as plants [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Such anthropogenic activities often include the pursuit of welfare assets by human communities across different scales. For instance, human recreation has been shown to negatively affect the natural environment and is the main cause of biodiversity degradation in developed countries [

11,

12]. Notably, recreation activities can result in avoidance of trails by mammals, alteration of behavior, increased mortality, introduction of non-native species and reduced fitness among others [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. For instance, moose, snowshoe hare, and red fox avoid areas used by tourists in the Isle Royale national park [

21]. Similarly, agricultural activities, including in the global south affect wildlife in different ways [

22,

23,

24].

Agriculture is the major cause of land cover change in the global south, threatening biodiversity across different scales [

25,

26,

27]. Given that the growing human population is predicted to be at 9.7 billion by 2050; 2.5 billion of whom will be in Africa [

28], unless the right interventions are put in place, biodiversity loss may increase at unprecedented rates [

29,

30,

31,

32]. A balance can be achieved through improved understanding of the dynamics of anthropogenic events and their consequences on biodiversity.

Bats play critical roles in sustaining ecosystems and provide opportunities for directly accessing critical welfare assets such as spiritual and cultural value, food security, and nutrient-rich guano to support crop production [

33,

34]. Despite these values, bat populations are threatened by anthropogenic factors including pollutants and habitat change [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Cave ecosystems that are critical roosting sites for bat populations commonly get severely affected by anthropogenic activities [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Anthropogenic cave disruption includes noise, light and actual cave destruction [

37,

47,

48,

49]. These threats may undermine the population of bats across different scales. The International Union for Conservation of Nature estimates that over 15% of species are considered endangered or near threatened (IUCN), with their populations decreasing globally [

37,

50]. This is especially common in tropical regions where anthropogenic activities cause land use changes threatening bat populations [

37,

51,

52]. Moreover tropical regions host substantial bat diversity contributing to sustainability of ecosystems [

53,

54]. Therefore, there is a need for interventions to mitigate threats to bat populations in tropical regions and elsewhere. These partly require understanding bat vulnerability within cave ecosystems. Vulnerability studies have been undertaken in Bulgaria [

46], Philippines [

55] and Ghana [

56] providing critical information that can be utilized to support conservation of bat populations. Beyond bat populations, such information provides opportunities for understanding the role of humans in landscape changes. Notably, bats are diverse and provide a model for better understanding of alterations within ecosystems across different scales [

35,

57,

58].

Caves are critical in sustaining bat populations as they are used for roosting [

59], breeding [

60,

61], hibernation and swarming [

45,

62]. Bats choose and use the different caves and cave sites depending on the environmental and geographical features [

63,

64]. Notably, temperature and humidity can influence the selection of caves for breeding and/or hibernation (especially in temperate regions) among other functions [

60,

65,

66]. Cave selection by bats varies across space and time depending on the species of the bat and foraging behavior among other factors [

67,

68]. While natural factors influence ambient conditions in caves, human activities can significantly make them unfit for bat utilization [

69,

70,

71,

72]. The vulnerability of caves is critical as bats are also good candidates as surrogate species (i.e., keystone, umbrella, and indicator taxa) of cave biodiversity and conservation value [

73,

74]. Adequate scientific data that provides for understanding of the vulnerability of cave bat roosts to anthropogenic disturbances provides opportunities for designing of suitable conservation interventions that try to accommodate human access needs while protecting the most vulnerable aspects of the cave ecosystem for bats. This approach contributes to sustaining ecosystems and human livelihoods. This study assessed vulnerability of caves used for roosting by bats to anthropogenic disturbances within Mount Elgon, Uganda.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

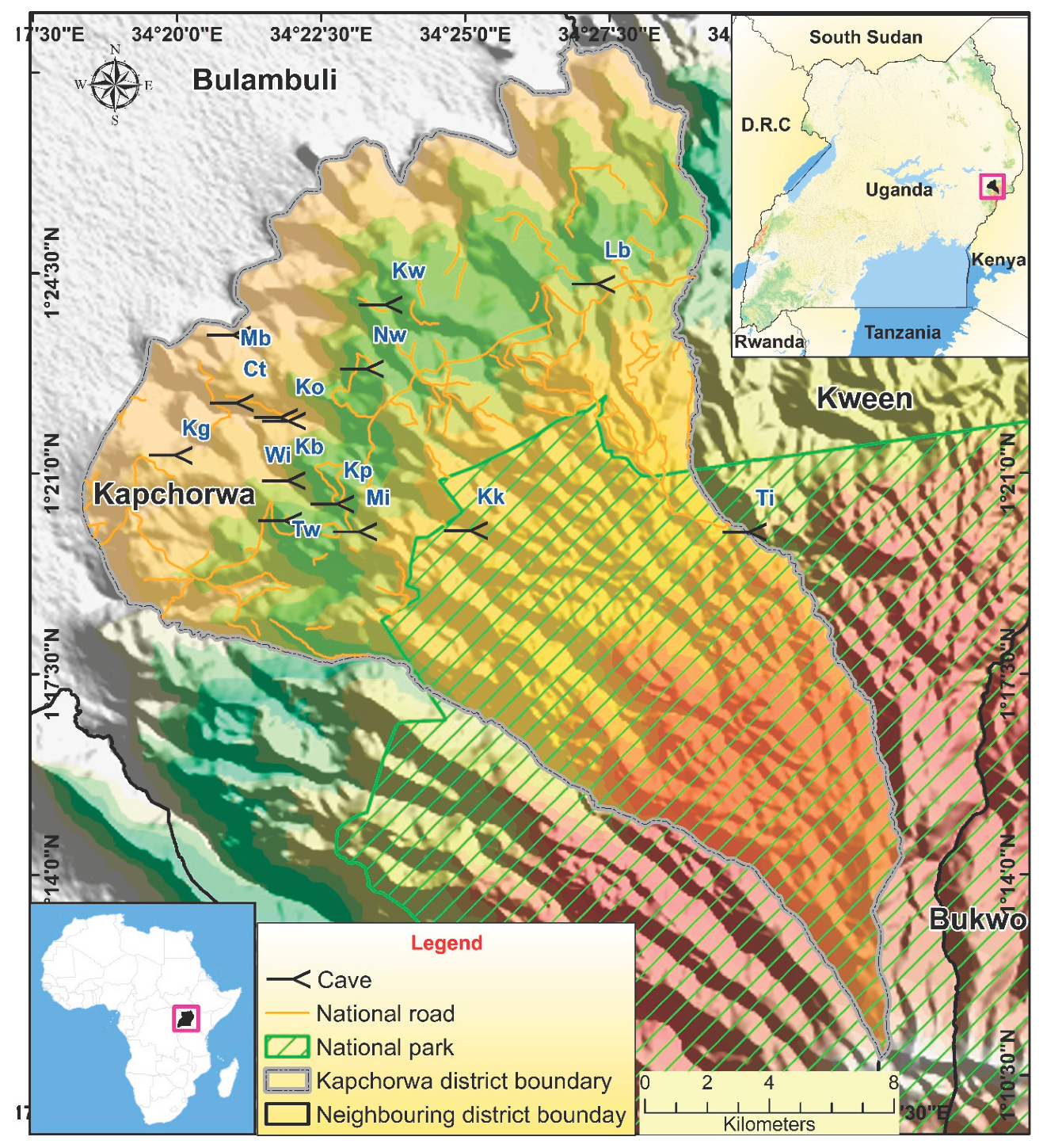

This study was undertaken on bat-occupied caves in the Mount Elgon region of Uganda with a focus on the Kapchorwa district (

Figure 1). Kapchorwa district is bordered by Kween District to the northeast and east, Sironko District to the south, and Bulambuli District to the west and northwest (

Figure 1). Kapchorwa has the largest human population within the region with a rapid growth rate of 2.5% (almost equivalent to the national rate 2.9%) [

75]. The district also has very diverse economic activities including tourism, agriculture and trade among others [

76].

2.2. Study Design and Approaches

A cross sectional survey design was applied in communities near cave sites utilizing mixed methods research approaches [

77,

78]. Mixed methods allowed for data integration thus better understanding of the research question [

79,

80]. The purpose of the community engagement was to gather insights on the activities undertaken in the caves. This insight provided by the communities would then validate findings of the vulnerability factors identified for the caves. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected.

2.3. Study Population

This study focused on both insect and fruit eating bats inhabiting caves whose populations formed the basis of the quantitative data. The measured parameters within each cave included bat numbers, bat species richness and human activities within caves. Households neighboring caves inhabited by bats formed the target population for qualitative data collection through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). FGDs focused on community perspectives about activities carried out within each of the caves. Two Focus Group Discussions were organized in villages near each cave involving persons that live nearest to caves. The distance to each cave from members of the local community was variable and we considered those that were closer until we reached a maximum of 10 individuals. The FGDs were held with adult (at least 18 years old) male and female participants after verbal consent was obtained. The consenting process included discussion of information shared about the study, participation, and privacy practices for the study. Participants were also informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks of the study and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time.

2.4. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

Only caves that were easily accessible (by the research team) within the district were selected for this study. Bat counts in the selected caves were performed over a period of 3 years (2022-2024) whenever the caves were visited for routine monitoring studies on the bats as a part of other projects. At each cave, bats species in the caves were identified and counts of individuals conducted using either visual counts or mist-netting to establish the population sizes. As some caves had several chambers, counting every single individual was difficult in which case an estimated maximum number was recorded. Using these approaches, all the parameters to describe Biotic potential (BP) and Biotic Vulnerability (BV) as described by Tanalgo and colleagues were collected [

44].

In addition to bat-specific data, anthropogenic source data including cave accessibility, cave size, and openings, the effort of exploration, tourism potential, cave use, land-use activities in areas adjacent to the cave, and the presence of temples and sacred structures in the caves was also investigated. Literature was used to gather data on some Biotic potential (BP) parameters that included species endemism (E) and conservation status ().

For prioritization of caves and suitable conservation interventions to sustain populations of bats, data were collected on the potential threats to the different bat roosts. This was undertaken using a checklist that covered anthropogenic and natural factors that could threaten bat populations (

Table S3 in Supplementary file). For instance, the check list covered; presence of collapsed entrances, household items, introduced twigs, among others.

2.5. Data Analysis

The Bat Cave Vulnerability Index (BCVI) was used to assess vulnerabilities of these caves to anthropogenic disturbance [

44]. The BCVI is described by the equation;

where;

BCVI = Bat Cave Vulnerability Index, BP = Biotic Potential Index, BV = Biotic Vulnerability Index.

2.6. Computation of Biotic Vulnerability (BV)

Biotic Vulnerability (BV) represents cave geophysical features and anthropogenic threats to the cave.

The Biotic Vulnerability (BV) value is derived using the equation;

where: N=Threats assessed N

0 = Number of threats assessed/present

Threats for each of the caves were obtained through observations and interviews with community members. These respective threats were scored using a scale of 1-4 (as outlined in

Table S3 in the supplementary). Threats were then averaged to obtain the value of Biotic Vulnerability (BV). The value computed using the Biotic Vulnerability (BV) index was assigned to a category of “A”, “B”, “C” or “D”, following the methods of Tanalgo et al. [

44]. The lowest value of this index is 1.00 as ‘Status A’, which represents caves that are highly disturbed and/or prone to disturbance. The highest value is 4.00 as ‘Status D’, which represents pristine caves with no disturbance (

Table 1, as in [

44]).

2.7. Computation of Biotic Potential (BP)

Biotic potential (BP) of the caves integrated; species richness (S) and Population (A), species relative abundance (Ar), endemism (E) and conservation status (

) and species-site commonness index (site) (see [

44]). These variables included in the equation as;

In this study, the method for assessing bat populations was standardized among all cave sites. This included using the maximum number counted of each species from all the counts done or estimated over the three-year period i.e., 2022 to 2024 in the BP calculations (

Table S1 in Supplementary). The species richness (S) represents the number of bat species encountered in the caves.

The relative species abundance (

) indicates information on the status of the population relative to other caves. This value was calculated for each cave by dividing the maximum number of bats observed in that cave by the sum of the maximum numbers of bats of that species observed from all caves. By exploring relative abundance for each species, it provided for better understanding of how each cave performed relative to “global/regional” species average and not caves of particular importance [

44]. However, because accurate counts of bats in the cave roosts were difficult to establish, the population figures presented may be an under-representation of the population of bats in some of the caves.

The endemism value (

E) is based on bat species range distribution while conservation status (

cons) is based on the global population, distribution status as well as trends of bat species as described by Tanalgo and colleagues (see [

44]). These two variables were derived from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) where respective factors were given scores. For this paper, we adopted the scale utilized by Tanalgo and colleagues to indicate the scores for the endemism and conservation status of different bat species (see [

44]). The Species-site commonness index (

site) is as a measure of the rarity of the bat species from the caves assessed and is calculated as the frequency of occurrence of each bat species in the caves assessed [

44]. A species-site commonness index of less than 1 are interpreted as the species only occurring in very few caves whereas values equal to 1 reflect the presence of that species in all caves. For this study, the Biotic Potential (BP) values were set for this study ranging from 100 and below to 900 and above. Consequently, “Level 1” caves were classified as high in species diversity, while caves classified as “Level 4” are the least biodiverse caves (

Table 2).

The results from both indices, Biotic Potential (BP) and Biotic Vulnerability (BV) were multiplied to form an alphanumeric value that summarizes the general vulnerability and priority of the cave. When both indices are synergistically joint (alphanumeric index), different prioritization levels are derived.

2.8. Determining Bat Cave Vulnerability Indices (BCVI)

Cave sites were classified based on the combined values of BP and BV using criteria described by Tanalgo et al. [

44]. Caves rated as ‘1A, 1B, and 2A’ (High Priority) are especially vulnerable to anthropogenic threats and population declines and represent locations where conservation interventions should be implemented to control human activities. Additionally, caves rated as ‘1C’, ‘1D’, ‘2B’, ‘2C,’ ‘2D’, ‘3A’,’3B’, ‘3C’, and ‘3D’ are categorized as moderately vulnerable due to less frequent anthropogenic pressures and disturbance. Lastly, caves that are ranked as ‘4A’, ‘4B’, ‘4C’ and ‘4D’ are considered the least vulnerable (Low Priority) because they either have high populations of bats and/or are relatively undisturbed. All calculations were done in Excel 2023 for Windows [

81].

Qualitative data from FGD that was collected during the study, was analyzed using thematic approaches. This included the 6-step process i.e., familiarization, coding, theme development, reviewing themes, defining themes, and reporting findings. Familiarization includes understanding the data the way it is. At the coding stage, coding is assigned to the different key ideas, patterns and concepts. Thereafter, codes are grouped together into a theme reflecting broader patterns of data. These themes were grouped together to form broader themes. The developed themes were then reviewed and updated to ensure accuracy. After reviewing and refining themes, their consistency was ensured by providing clear definitions and names. Finally, the findings were reported with quotes and interpretation of the meaning of such quotes. This six stage process was carried out and with support of NVivo version 12 [

82].

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Caves Assessed

In total, fourteen caves were assessed within the study area (

Table S1 in Supplementary). The total number of bat species in the caves were seven including five insectivorous (

Coleura afra, Miniopterus spp

., Rhinolophus spp.

, Hipposideros ruber, Nycteris macrotis) and two fruit eating bats (

Rousettus aegyptiacus, and Myonycteris angolensis) species (

Table S1 in Supplementary file). For this study,

Rhinolophus spp. and

Miniopterus spp. bats are taken as one species owing to the complexity of characteristics of these genera, and the difficulty to separate species using the observational methods used in this study. In terms of conservation status, all the bats recorded were in “Least Concern” IUCN category (

Table S3 in Supplementary file). The

Rhinolophus genus was included in the IUCN “least concern” because all the potential species present in our study area fall within this category. All caves experienced at least one of the human activities (disturbances) including mining for guano and rocks, tourism, sociocultural activities and bat hunting (

Table S2 in Supplementary file).

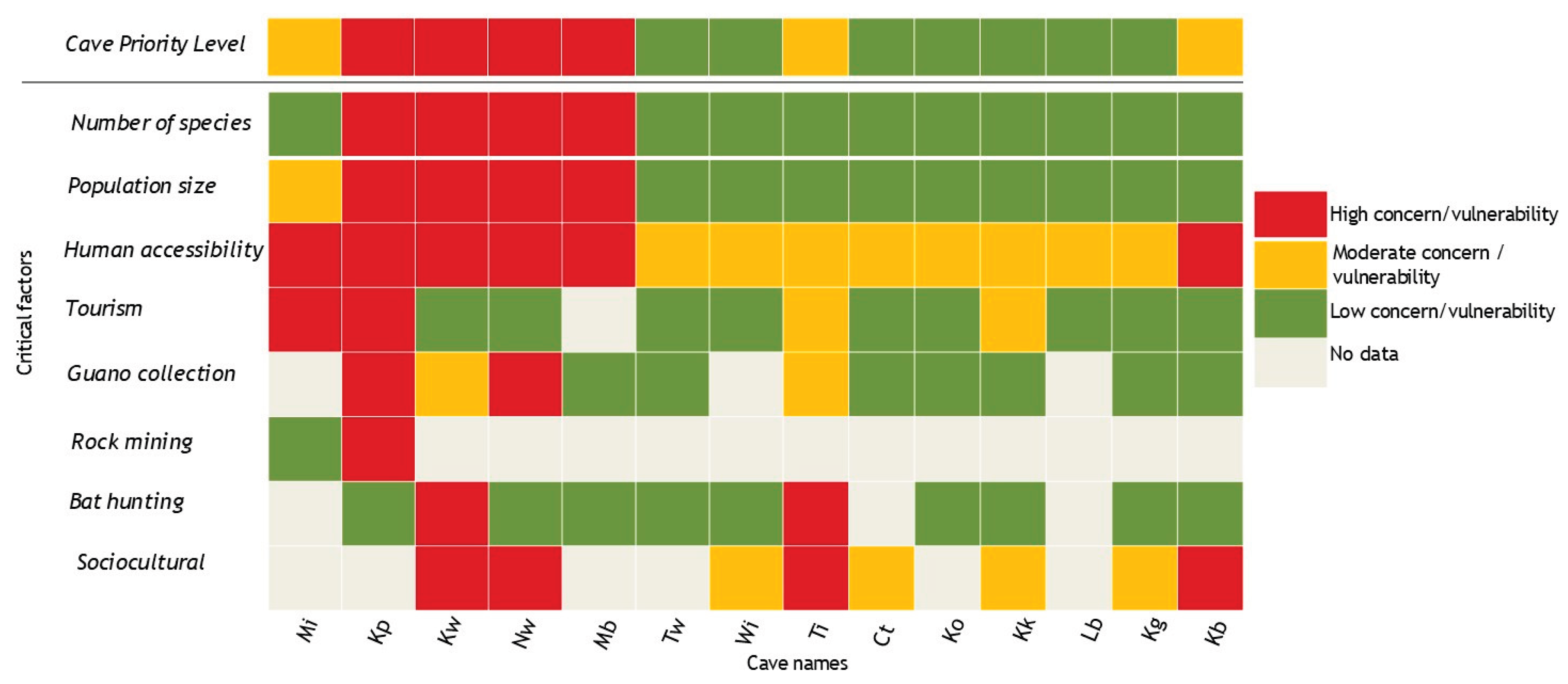

3.2. Vulnerability of the Different Caves to Anthropogenic Cave Disturbance

In terms of biotic potential, four of the caves ranked “Level 1” reflecting the high number of bats (

Table 3). The other caves had biotic potential of “Levels 3 & 4” (

Table 3). In terms of biotic vulnerability, over half (71.4%, n=14) of the caves were in category “A” of the biotic vulnerability reflecting greater accessibility and human activities carried out within these caves (

Table 3). The combined BCVI revealed up to half (50%) of the caves assessed ranked “High” or “Moderate” priority for conservation (

Table 3). These rankings suggest that these caves are critical in supporting bat populations and therefore require high prioritization for conservation action.

3.3. Human Dimensions

From the community engagements, it was clear that caves are widely utilized by communities for various activities. This mainly included their use as; shelter, performing sociocultural and spiritual activities, salt and guano mining. These uses present opportunities for increased vulnerability of bats to human disturbances. Notably, guano mining appeared to be commonly practiced increasing human presence in caves. This increased human presence in caves potentially causes disturbances to bat populations. Additionally, cultural and spiritual activities were undertaken in caves. Other activities included keeping livestock and hunting for bats. All of these activities pose disturbance to bat populations inside caves.

Within the caves which were ranked as high and moderate priority, some of the human activities that were observed and also reported during focus group discussions included;

- -

Guano mining was mainly in Kw, Ti, Nw and Kp. The mined guano gets used in banana and coffee plantations to as fertilizer to the crops.

“We get a lot of ‘buresik’ from this cave. You can get a full sac of 100 kgs and can enable production of big bunches of bananas”, one male elder noted regarding “Nw” cave.

- -

Some socio-cultural activities that were recorded in the caves included aspects of childbirth as well as initiation. This was indicated by the objects found in the caves as well as interviews with local residents. This was majorly reported in Nw and Kw.

“Women who give birth to twins are brought here with some food produce carried using ‘Kiiset’ (locally made container using bamboo). The women are the ones who do this to their fellow woman, and they sing while the drum is beaten. This is done to protect the children and enable them live longer”, one female elder noted regarding “Kw” cave.

- -

Most caves were utilized as shelter whenever it rains. This was reported to be a common practice for those who cultivate the land near the caves as well as those engaged in livestock rearing. This use was reported to happen more frequently in the wet season. This was reported in all the caves.

“For us whenever it rains, we go to the cave because that’s the nearby house. Rain cannot of course get you when you are inside”, noted by one male elder regarding “Kp” cave

“Whenever we are in the lower altitude, we construct animal shelter near the cave, and we sleep inside. This is good because the cave is protective from hostile enemies”, one male respondent noted regarding “Nw” cave

3.4. Conservation Priorities

Our results show that half of (7/14; 50%) caves in the study site were in the “High” and “Moderate” conservation priority categories (

Figure 2). The main critical factors linked to these high and moderate conservation priorities included the high number of bat species and high human presence inside and outside the cave. Our results identified 4 caves (Kp, Kw, Nw and Mb) to be of high conservation priority, a fact we attribute to more species in the cave and human presence. Focus Group Discussions with members of the local community near some of the caves (i.e., Nw, Mi, Wi and Kw) suggested they were historically used as shelter for livestock (mainly cattle). However, this activity is no longer happening. Although we didn’t find the cows in the cave, Wi cave continued to have evidence (cow dung and footprints) of these having been in the cave before our visits happened.

“We used to use this cave for keeping our animals and protect them from raiders but now there are many crops around, so we have moved our cows further down the lower belts”, one male elder noted regarding “Nw” cave.

“This cave would accommodate cows for the whole community. It is so big that is why you see the cow dung is still a lot”, another male elder added regarding “Nw” cave.

4. Discussion

The results of this study revealed that a high number of caves of the Kapchorwa area of Mount Elgon, Uganda are vulnerable to anthropogenic disturbance (

Table 3). A half of the caves ranked “high” or “moderate” priority for bat conservation reflecting the incidences of broader socioeconomic activities on the cave ecosystems currently supporting high bat populations within this area. While similar studies are yet to be undertaken in Uganda and utilizing similar methodologies, the result obtained in this study is comparable to that in other areas. For instance, in Ghana, a study by Nkrumah and colleagues indicated caves to fall mainly within “high” and “moderate” conservation priorities [

56]. Similarly, a study in Bulgaria by Deleva and colleagues revealed 32% of the bat roosts to fell within the high priority conservation status [

46]. In Costa Rica, and the Philippines, some caves fell into the “high priority” conservation category [

83,

55]. While the scales for analyzing different parameters within the framework were different, the results from previous studies, and ours, suggest that increasing pressures from anthropogenic drivers may negatively affect bat populations in cave ecosystems. This difference in scaling for the framework parameters was necessary as the nature of caves, socio-economic and environmental factors are highly context dependent. This context-dependency implies conservation interventions have to be adaptable to the local contexts for significant outcomes to be realized.

Critical anthropogenic drivers for cave vulnerability included use of caves for tourism, accessing guano and undertaking cultural and spiritual events. In some cases, there were incidences of bat hunting activities evidenced by thorny twigs used for bat capture and information from community surveys. Evidence of fireplaces was recorded in the caves and community members indicated that some bats hunted are prepared onsite before being taken out to the community. Indeed, most of the caves that ranked high priority for conservation experienced hunting. These are critical anthropogenic threats to cave biota and have potential to affect bat populations. Declines in bat populations would threaten ecosystems within such sites as bats have been indicated to be umbrella species [

73,

74]. Notably, the nutrient rich guano provides energy to microbes that in turn support other organisms within the cave [

73,

74].

A study in Costa Rica found human activities including tourism to threaten cave systems [

83]. A study in Philippines found hunting, tourism and guano mining to be critical factors affecting cave dwelling bats [

55]. The frequent human visits have also been shown to increase noise disturbances which causes bats to fly losing energy while disrupting echolocation [

84,

85]. Such noise has been shown to affect foraging and roosting behavior of insectivorous bats [

86]. Some studies have shown that noise alters the gene expression associated with diseases and metabolism in bats [

87]. Therefore, while our study did not attempt to analyze the effects of human disturbances on bats, it is possible that such occurrences pose wide ranging effects on bats within cave ecosystems. Interventions thus ought to be implemented to mitigate such incidences to protect bat populations across different scales. This will contribute to sustaining ecological systems in and outside of caves.

The bat fauna in the caves studied included both insectivorous and frugivorous largely occurring in different associations in the different caves. Species recorded in Kapchorwa caves have been previously reported within this region as well as other areas [

88,

89]. This implies that it is critical to manage these caves already occupied by bats to ensure survival of the different species and their populations. [

90,

91,

92].

From the community engagement through FGDs, it was apparent that caves are central to socioeconomic aspects [

93]. This reflects their value in human societies as observed elsewhere [

94,

95,

96]. Such benefits derived from cave ecosystems if not balanced can have negative consequences on biota (e.g., bats) in such sites. In addition, healthy population of bats in cave ecosystems can fundamentally support human communities [

95,

96]. Interventions that integrate human dimensions and promote conservation messaging that educate communities about the benefits bats provide them can foster the sustainable management of caves in the Mount Elgon region. This approach will contribute to sustainability of bat populations as well as other biota within caves.

5. Strengths and Limitations of This Study

While the BCVI provides opportunities for adapting in different contexts through recalibration, it may be difficult to apply in areas where bats are migratory in nature. Such migrations of bats affect the parameters of the model resulting into inaccurate priority indices. Integration of the human dimensions through focus group discussions enhanced our understanding of anthropogenic factors within these caves. During implementation of conservation interventions, such human dimensions are useful in ensuring community participation as well as sustainability of the actions. Indeed, our study conducted in the same area indicated communities to be willing to support bat conservation through labor and monetary values [

97]. They can do this and moreover for the different ecosystem values derived from these mammals. This framework also provides an opportunity for extending conservation actions outside protected areas, in that caves already afforded some protection within the park had lower conservation priorities compared to those outside the park boundary. Moreover, some of the caves outside the park had more bats species and individuals compared to the one in the park.

Furthermore, considering only the maximum number of bats counted on different occasions may likely have under-estimated/ over-estimated the real populations in some of the caves. However, because of our repeated visits to the caves, the errors associated with this can be minimal that it can have less effects on the final indices of the BCVI.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Our study highlights the vulnerability of a set of caves within Mount Elgon to anthropogenic disturbances, on the basis of which we highlight the need for targeted conservation actions to protect these unique habitats and their bat populations. Despite the absence of long-term monitoring data, current findings underscore the necessity of immediate interventions to sustain bat populations and maintain the ecological integrity of cave systems in the region. Working with members of the local community, it may be essential to implement urgent conservation interventions focused on the most vulnerable caves to safeguard resident bat populations. It will also be essential to design human livelihood strategies that align with the sustainability of cave ecosystems, ensuring that development does not compromise ecological balance. To reduce pressures on the caves and bat roosts, the community initiatives could consider opportunities to compensate for goods and services derived from bats and cave ecosystems. To better understand the integrity of caves and stability of roosts and bat communities therein, given the continued community interests - long-term monitoring efforts will be essential to generate robust data to inform any conservation interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Tables S1, S2, S3 and S4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., R.C.K., E.S.., I.B.R., C.M. and R.M.K.; formal analysis, A.S., and K.M.W.; investigation, A.S.; resources, R.C.K. and A.S.; data curation, A.S., and K.M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, B.M., L.N., M.M., B.N., K.C., T.D., N.R.W. and E.K.H.; visualization, K.M. W.; funding acquisition, R.C.K. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Colorado State University. Data collected on bats was funded in part by This research was funded by the United States Defense Threat Reduction Agency Biological Threat Reduction Program (DTRA-BTRP) project number HDTRA1-19-1-0030.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study will be sought from the Makerere University Ethics Committee at the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES-REC-2023-37). Permission and registration of this research were done at Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST). The UNCST approval number of the research is NS718ES. In addition to this, consent was sought from the respondents before the administration of the questionnaires. Anonymity of the respondents was ensured during reporting of the results. Field sampling of bats was approved by the Uganda Wildlife Authority (COD/96/05), the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (NS663), the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 1314), the US Department of Defense Animal Care and Use Committee (ACURO)(CT-2019-21.e001).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal consent was obtained from respondents. This was done after telling them the details of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Since the data with cave names can expose bats to increased human intensity, we will make it available on request from the corresponding author. Similarly, data from Focus Group Discussions will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

we also thank the Bat Ambassadors (Winnex Cherotwo, Chebet Phalti, Chekwemboi Prisca, Chelangat Enoch, Tongo Millat and Chebet Junior) for supporting fieldwork activities. We thank the people of Kapchorwa for allowing us to conduct research within their community.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCVI |

Bat Cave Vulnerability Index |

| BP |

Biotic Potential |

| BV |

Biotic Vulnerability |

| FGD |

Focus Group Discussion |

References

- Barnosky AD, Matzke N, Tomiya S, Wogan GOU, Swartz B, Quental TB, et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature. 2011.

- Pimm SL, Jenkins CN, Abell R, Brooks TM, Gittleman JL, Joppa LN, et al. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science. 2014.

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Barnosky AD, García A, Pringle RM, Palmer TM. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci Adv. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Dirzo R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Raven PH. Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cowie RH, Bouchet P, Fontaine B. The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation? Biol Rev. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR. Mammal population losses and the extinction crisis. Science (80- ). 2002. [CrossRef]

- Crooks KR, Burdett CL, Theobald DM, King SRB, Di Marco M, Rondinini C, et al. Quantification of habitat fragmentation reveals extinction risk in terrestrial mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bowler DE, Bjorkman AD, Dornelas M, Myers-Smith IH, Navarro LM, Niamir A, et al. Mapping human pressures on biodiversity across the planet uncovers anthropogenic threat complexes. People Nat. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Xu H, Pan S, Chen W, Zeng J. Identifying the impact of global human activities expansion on natural habitats. J Clean Prod. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne M, Pickering CM. Tourism and recreation: A common threat to IUCN red-listed vascular plants in Europe. Biodivers Conserv. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Larson CL, Reed SE, Merenlender AM, Crooks KR. Effects of recreation on animals revealed as widespread through a global systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016.

- Garber SD, Burger J. A 20-yr study documenting the relationship between turtle decline and human recreation. Ecol Appl. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Taylor AR, Knight RL. Wildlife responses to recreation and associated visitor perceptions. Ecol Appl. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Reed SE, Merenlender AM. Quiet, Nonconsumptive Recreation Reduces Protected Area Effectiveness. Conserv Lett. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Naylor LM, J. Wisdom M, G. Anthony R. Behavioral Responses of North American Elk to Recreational Activity. J Wildl Manage. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Steven R, Pickering C, Guy Castley J. A review of the impacts of nature based recreation on birds. Journal of Environmental Management. 2011.

- Zhou Y, Buesching CD, Newman C, Kaneko Y, Xie Z, Macdonald DW. Balancing the benefits of ecotourism and development: The effects of visitor trail-use on mammals in a Protected Area in rapidly developing China. Biol Conserv. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Dertien JS, Larson CL, Reed SE. Recreation effects on wildlife: A review of potential quantitative thresholds. Nature Conservation. 2021.

- Rosenthal J, Booth R, Carolan N, Clarke O, Curnew J, Hammond C, et al. The impact of recreational activities on species at risk in Canada. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Boone HM, Romanski M, Kellner K, Kays R, Potvin L, Roloff G, et al. Recreational trail use alters mammal diel and space use during and after COVID-19 restrictions in a U.S. national park. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2025;57:e03363.

- Phillips HRP, Newbold T, Purvis A. Land-use effects on local biodiversity in tropical forests vary between continents. Biodivers Conserv. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Endenburg S, Mitchell GW, Kirby P, Fahrig L, Pasher J, Wilson S. The homogenizing influence of agriculture on forest bird communities at landscape scales. Landsc Ecol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi HG, Woollen ES, Carvalho M, Parr CL, Ryan CM. Agricultural expansion in African savannas: effects on diversity and composition of trees and mammals. Biodivers Conserv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Perrings C, Halkos G. Agriculture and the threat to biodiversity in sub-saharan Africa. Environ Res Lett. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Winkler K, Fuchs R, Rounsevell M, Herold M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat Commun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Leisher C, Robinson N, Brown M, Kujirakwinja D, Schmitz MC, Wieland M, et al. Ranking the direct threats to biodiversity in sub-Saharan Africa. Biodivers Conserv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World population projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 with most growth in developing regions, especially Africa. United Nations. 2015.

- McKee JK, Sciulli PW, David Fooce C, Waite TA. Forecasting global biodiversity threats associated with human population growth. Biol Conserv. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Luck, GW. A review of the relationships between human population density and biodiversity. Biological Reviews. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cafaro P, Hansson P, Götmark F. Overpopulation is a major cause of biodiversity loss and smaller human populations are necessary to preserve what is left. Biol Conserv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Fráncel LA, García-Herrera LV, Losada-Prado S, Reinoso-Flórez G, Sánchez-Hernández A, Estrada-Villegas S, et al. Bats and their vital ecosystem services: a global review. Integrative Zoology. 2022.

- Aggrey S, Rwego IB, Sande E, Khayiyi JD, Kityo RM, Masembe C, et al. Socioeconomic benefits associated with bats. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2024;20.

- Jones G, Jacobs DS, Kunz TH, Wilig MR, Racey PA. Carpe noctem: The importance of bats as bioindicators. Endangered Species Research. 2009.

- Naidoo S, Vosloo D, Schoeman MC. Pollutant exposure at wastewater treatment works affects the detoxification organs of an urban adapter, the Banana Bat. Environ Pollut. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Frick WF, Kingston T, Flanders J. A review of the major threats and challenges to global bat conservation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2020.

- Cory-Toussaint D, Taylor PJ. Anthropogenic Light, Noise, and Vegetation Cover Differentially Impact Different Foraging Guilds of Bat on an Opencast Mine in South Africa. Front Ecol Evol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo KC, Sritongchuay T, Agduma AR, Dela Cruz KC, Hughes AC. Are we hunting bats to extinction? Worldwide patterns of hunting risk in bats are driven by species ecology and regional economics. Biol Conserv. 2023;279.

- Zukal J, Pikula J, Bandouchova H. Bats as bioindicators of heavy metal pollution: History and prospect. Mammalian Biology. 2015.

- Sotero DF, Benvindo-Souza M, Pereira de Freitas R, de Melo e Silva D. Bats and pollution: Genetic approaches in ecotoxicology. Chemosphere. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cardiff SG, Ratrimomanarivo FH, Rembert G, Goodman SM. Hunting, disturbance and roost persistence of bats in caves at Ankarana, northern Madagascar. Afr J Ecol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo KC, Teves RD, Salvaña FRP, Baleva RE, Tabora JAG. Human-Bat Interactions in Caves of South Central Mindanao , Philippines. 2016; August 2017. [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo KC, Tabora JAG, Hughes AC. Bat cave vulnerability index (BCVI): A holistic rapid assessment tool to identify priorities for effective cave conservation in the tropics. Ecol Indic. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo KC, Oliveira HFM, Hughes AC. Mapping global conservation priorities and habitat vulnerabilities for cave-dwelling bats in a changing world. Sci Total Environ. 2022;843.

- Deleva S, Toshkova N, Kolev M, Tanalgo K. Important underground roosts for bats in Bulgaria: current state and priorities for conservation. Biodivers Data J. 2023;11.

- Voigt CC, Kingston T. Bats in the anthropocene. In: Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World. 2015.

- Schoeman, MC. Light pollution at stadiums favors urban exploiter bats. Anim Conserv. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung K, Threlfall CG. Trait-dependent tolerance of bats to urbanization: A global meta-analysis. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Welch JN, Beaulieu JM. Predicting extinction risk for data deficient bats. Diversity. 2018. [CrossRef]

- García-Morales R, Badano EI, Moreno CE. Response of Neotropical Bat Assemblages to Human Land Use. Conserv Biol. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Núñez SF, López-Baucells A, Rocha R, Farneda FZ, Bobrowiec PED, Palmeirim JM, et al. Echolocation and Stratum Preference: Key Trait Correlates of Vulnerability of Insectivorous Bats to Tropical Forest Fragmentation. Front Ecol Evol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, DM. Diversity of New World mammals: Universality of the latitudinal gradients of species and bauplans. J Mammal. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickleburgh SP, Hutson AM, Racey PA. A review of the global conservation status of bats. ORYX. 2002.

- Bejec GA, Bucol LA, Reyes TD, Jose RP, Ancog AB, Pagente AC, et al. Vulnerability Assessment of Cave Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) of Central Visayas, Philippines. Asian J Biodivers. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah EE, Baldwin HJ, Badu EK, Anti P, Vallo P, Klose S, et al. Diversity and Conservation of Cave-Roosting Bats in Central Ghana. Trop Conserv Sci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Park, KJ. Mitigating the impacts of agriculture on biodiversity: Bats and their potential role as bioindicators. Mammalian Biology. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo D, Salinas-Ramos VB, Cistrone L, Smeraldo S, Bosso L, Ancillotto L. Do we need to use bats as bioindicators? Biology (Basel). 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kunz TH. Roosting Ecology of Bats BT - Ecology of Bats. In: Kunz TH, editor. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1982. p. 1–55.

- Kunz, TH. Population studies of the cave bat (Myotis velifer): reproduction, growth, and development. Occas Pap Museum Nat Hist Univ Kansas. 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann SL, Steidl RJ, Dalton VM. Effects of Cave Tours on Breeding Myotis velifer. J Wildl Manage. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Randall J, Broders HG. Identification and characterization of swarming sites used by bats in Nova Scotia, Canada. Acta Chiropterologica. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Leivers SJ, Meierhofer MB, Pierce BL, Evans JW, Morrison ML. External temperature and distance from nearest entrance influence microclimates of cave and culvert-roosting tri-colored bats (Perimyotis subflavus). Ecol Evol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Barros J de S, Bernard E, Ferreira RL. Ecological preferences of neotropical cave bats in roost site selection and their implications for conservation. Basic Appl Ecol. 2020;45:31–41.

- Siivonen Y, Wermundsen T. Characteristics of winter roosts of bat species in southern Finland. Mammalia. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Belkin V V., Panchenko D V., Tirronen KF, Yakimova AE, Fedorov F V. Ecological status of bats (Chiroptera) in winter roosts in eastern Fennoscandia. Russ J Ecol. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Thomas JP, Kukka PM, Benjamin JE, Barclay RMR, Johnson CJ, Schmiegelow FKA, et al. Foraging habitat drives the distribution of an endangered bat in an urbanizing boreal landscape. Ecosphere. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Neubaum DJ, Aagaard K. Use of predictive distribution models to describe habitat selection by bats in Colorado, USA. J Wildl Manage. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Clements R, Sodhi NS, Schilthuizen M, Ng PKL. Limestone karsts of southeast Asia: Imperiled arks of biodiversity. BioScience. 2006.

- Niu H, Wang N, Zhao L, Liu J. Distribution and underground habitats of cave-dwelling bats in China. Anim Conserv. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Furey NM, Racey PA. Conservation ecology of cave bats. Bats Anthr Conserv Bats a Chang World. 2015;:463–500.

- Medellin RA, Wiederholt R, Lopez-Hoffman L. Conservation relevance of bat caves for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Biol Conserv. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Trajano, E. Protecting caves for bats or bats for caves? Chiropt Neotrop. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Culver DC, Pipan T. The Biology of Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats. 2019.

- UBOS. National Population and Housing Census 2024: Preliminary Results. Natl Popul Househ Census. 2024;256 June:23.

- Kapchorwa District. Kapchorwa District. Opportunities. 2024. https://www.kapchorwa.go.ug/opportunites/agricultural-production. Accessed 12 Nov 2024.

- Levin, KA. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid Based Dent. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcomb E, Hickman L. Mixed methods research. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2015.

- Maxwell, JA. Expanding the History and Range of Mixed Methods Research. J Mix Methods Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibbett H, Jones JPG, Dorward L, Kohi EM, Dwiyahreni AA, Prayitno K, et al. A mixed methods approach for measuring topic sensitivity in conservation. People Nat. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2024.

- Lumivero. NVIVO 14. Lumivero. 2023.

- Deleva S, Chaverri G. Diversity and conservation of cave-dwelling bats in the Brunca region of Costa Rica. Diversity. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Whiting JC, Doering B, Aho K, Bybee BF. Disturbance of hibernating bats due to researchers entering caves to conduct hibernacula surveys. Sci Rep. 2024;14:13496.

- Bunkley JP, McClure CJW, Kleist NJ, Francis CD, Barber JR. Anthropogenic noise alters bat activity levels and echolocation calls. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Domer A, Korine C, Slack M, Rojas I, Mathieu D, Mayo A, et al. Adverse effects of noise pollution on foraging and drinking behaviour of insectivorous desert bats. Mamm Biol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Song S, Chang Y, Wang D, Jiang T, Feng J, Lin A. Chronic traffic noise increases food intake and alters gene expression associated with metabolism and disease in bats. J Appl Ecol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thorn E, Peterhans JK. Small Mammals of Uganda. Bonn Zool Monogr. 2009;:9-+.

- Kityo .R., Howell .K., Nakibuka .M., Ngalaso .W., Tushabe .H. WP. East African Bat Atlas. 2009.

- Ghanem SJ, Voigt CC. Increasing Awareness of Ecosystem Services Provided by Bats. In: Advances in the Study of Behavior. 2012.

- Kasso M, Balakrishnan M. Ecological and Economic Importance of Bats (Order Chiroptera). ISRN Biodivers. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ripperger SP, Kalko EKV, Rodríguez-Herrera B, Mayer F, Tschapka M. Frugivorous bats maintain functional habitat connectivity in agricultural landscapes but rely strongly on natural forest fragments. PLoS One. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Aggrey S, Rwego IB, Sande E, Khayiyi JD, Kityo RM, Masembe C, et al. Socioeconomic benefits associated with bats. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2024;20:78.

- Benedetto G, Madau FA, Carzedda M, Marangon F, Troiano S. Social Economic Benefits of an Underground Heritage: Measuring Willingness to Pay for Karst Caves in Italy. Geoheritage. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Algeo, K. Underground Tourists/Tourists Underground: African American Tourism to Mammoth Cave. Tour Geogr. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo B, Morales T, Uriarte JA, Antigüedad I. Implementing a comprehensive approach for evaluating significance and disturbance in protected karst areas to guide management strategies. J Environ Manage. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Siya A, Rwego IB, Sande E, Kityo RM, Masembe C, Kading RC. Household perceptions regarding bats and willingness to pay for their conservation within Mount Elgon Biosphere Reserve of Uganda. Front Conserv Sci. 2025;Volume 6-.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).