1. Introduction

Rapid advancements in robotics and artificial intelligence have driven the development of increasingly complex and adaptive systems capable of interacting efficiently with their environment [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among these, anthropomorphic robotic hands are essential for dexterous manipulation tasks [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], particularly in unstructured environments where adaptive grasping and safe physical interaction are critical. Their ability to emulate the motor and sensory capabilities of the human hand makes them versatile for a wide range of applications [

10,

11,

12], encompassing fields such as industrial automation, robot-assisted rehabilitation, assistive technologies, and scientific research. However, designing and controlling such robotic hands presents several challenges [

13,

14,

15]. These include, but are not limited to, inherent mechanical complexity [

6,

7,

8], the demand for reliable sensor integration [

16,

17,

18], and the critical need for precise coordination of multiple degrees of freedom [

19,

20,

21,

22].

In robotic manipulation, the concept of compliance has traditionally been associated with mechanical properties such as elastic joints or underactuated structures. Compliance can also be achieved through control strategies that deliberately modulate the relationship between motion and force, a principle formalized in Hogan’s seminal work on impedance control [

23]. This software-enforced compliance has since been widely recognized as fundamental in safe and adaptive physical human–robot interaction, where admittance and impedance control frameworks allow manipulators to yield passively to external contacts while maintaining stability [

24]. In the present work, the hand is actuated by servomotors operating in a current-based position control mode, enabling compliant grasping and intelligent control. This mechanism enforces compliant behavior through software, allowing the robotic hand to adapt passively to various object geometries, reduce excessive contact forces, and increase operational safety without requiring explicit trajectory replanning.

Built upon the open-source LEAP Hand platform [

25], the mechanical structure was fabricated and assembled, with modifications to support the integration of advanced sensing. A distributed sensor system, incorporating piezoresistive force sensors on the fingertips and palm, provides tactile feedback for contact detection. The entire system is managed by a ROS-based modular control architecture [

26], facilitating the execution of basic manipulation tasks and providing flexible access to sensor streams and actuator commands. The combination of software-enforced compliance and distributed tactile sensing results in a low-cost yet versatile solution for dexterous grasping and release, supporting robust interaction in unstructured environments.

A recurrent and critical problem is the occurrence of undesired finger overlaps during the hand opening sequence. These unintended configurations often result from suboptimal actuator activation ordering and can lead to internal collisions, excessive mechanical stress, and potential compromise of the system’s integrity. To address this challenge, a dedicated data acquisition pipeline was designed to collect comprehensive information on finger configurations. This data is then fed into a machine learning-based approach, specifically a multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifier, to automatically classify different types of finger overlap. As demonstrated by its high performance (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score all above 97%), this model highlights the potential for future predictive control strategies to ensure safe and coordinated finger motion.

This paper presents the full development pipeline, from hardware instrumentation and ROS-based control to the data-driven detection of unsafe configurations, providing a solid basis for intelligent and adaptable robotic hand control. Therefore, several contributions to the field of anthropomorphic robotic hand design and control are provided, including:

Development and integration of a distributed system of piezoresistive force sensors on the fingertips and palm of the LEAP Hand.

Implementation of a modular and reusable ROS-based control architecture, specifically designed for real-time sensor data acquisition and actuator command.

Employment of a hybrid actuator control strategy for the servomotors, allowing the fingers to naturally conform to the geometry of grasped objects without requiring complex active force control algorithms.

Development and validation of a machine learning-based coordination strategy to prevent undesired finger overlaps and collisions during the opening sequence of the hand.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work, focusing on anthropomorphic robotic hands, grasping strategies, and tactile sensing technologies.

Section 3 is dedicated to the force sensor implementation, describing the FSR sensor system and the procedures for testing and validation.

Section 4 presents the control architecture, detailing motor and finger control, the ROS 2-based software framework, and advanced control functionalities.

Section 5 introduces the machine learning approach for overlap detection, covering data acquisition, the neural network architecture, and experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main contributions and outlines the directions of future work.

2. Related Work

The field of robotic manipulation presents significant challenges, particularly in tasks that require robust grasping and physical interaction, whether between robots or in human-robot collaboration. In such contexts, the configuration and capabilities of the robotic end-effector play a crucial role in the effectiveness of the interaction. Anthropomorphic robotic hands have emerged as a promising approach due to their ability to replicate the dexterity and sensory feedback of the human hand. However, these systems entail substantial complexity in terms of design, control, and sensor integration.

2.1. Anthropomorphic Robotic Hands

Anthropomorphic robotic hands have long been a central topic in robotics research due to their potential to replicate the dexterity and versatility of the human hand [

1,

14,

27]. Numerous designs have been developed, ranging from high-performance commercial products to open-source, cost-effective platforms. Commercial robotic hands provide advanced capabilities but are often limited by their high cost, whereas open-source alternatives prioritize modularity, affordability, and accessibility for research and prototyping.

The Shadow Dexterous Hand [

28] and the Allegro Hand [

29] are two examples of commercial robotic hand widely adopted in both academic and industrial settings. The Shadow Hand offers over 20 degrees of freedom (DoF) via tendon-driven actuation, integrated tactile sensing, and compatibility with advanced teleoperation frameworks, making it one of the most sophisticated anthropomorphic hands available. The Allegro Hand, though more compact and cost-effective, provides 16 DoF with integrated torque sensing, being extensively used for reinforcement learning and dexterous manipulation research. Other platforms, such as the OceanTrix Hand and the Agile Hand, combine tactile sensing and active compliance control, but their cost limits accessibility for academic or prototyping purposes.

To overcome such limitations, open-source robotic hands have been developed as low-cost research alternatives [

30]. Examples include the HRI Hand, a ROS compatible platform with a sub-actuated mechanism and 6 DoF [

31]; the Robot Nano Hand, which integrates tendon-driven actuation with an onboard camera and Jetson Nano for AI-based tasks [

32]; and the Alaris Hand, which employs miniaturized linear actuators with worm gears to achieve 6 DoF and enhanced mechanical stability [

33]. Among open-source solutions, the LEAP Hand [

25] platform adopted in this work is particularly appealing. Designed as an open source alternative, this hand provides 16 DoF actuated by Dynamixel motors, with modularity, ROS integration, and simulation compatibility as core design principles. Fabricated primarily through 3D printing, it ensures affordability and adaptability while maintaining mechanical simplicity through servo-based actuation. This balance of dexterity, modularity, and accessibility makes the LEAP Hand especially well-suited for research on grasping, manipulation, and human-inspired control strategies.

2.2. Grasping Strategies

Recent advances in robotic grasping explore several strategies that balance perception, planning, and control in different ways. A first group of methods decouples grasp pose generation from joint control. These approaches typically begin by selecting a grasp configuration, either through analytic models or sampling-based techniques, and subsequently use a motion planner to perform the grasp. This decomposition simplifies the overall problem but introduces some limitations. Since the control policy relies entirely on the quality of the initial grasp and offers little possibility for correction during execution, errors in perception, object modeling, or grasp sampling directly affect performance. Notable examples of generative grasp synthesis include 6-DOF GraspNet [

34] and GG-CNN for real-time grasp prediction [

35]. A broader perspective on the trade-offs of such techniques is provided by the survey of Newbury et al. [

36].

To overcome the limitations of pose-based approaches, a second line of work focuses on learning control policies that directly command the hand using reinforcement learning (RL). These policies bypass the intermediate grasp sampling stage, enabling closed-loop adaptation to the object and the environment. However, the high-dimensionality of anthropomorphic hands presents a significant challenge to both sample efficiency and stability. Prior knowledge is frequently incorporated through behavior cloning and demonstration-guided rewards [

37], while an alternative strategy is to embed synergies that reduce the action representation space [

38]. More recent studies have explored robust simulation to reality (Sim2Real) transfer through domain randomization [

39]. Despite these advances, RL-based methods remain computationally demanding and sensitive to the quality of training data.

A third direction emphasizes compliance and contact-rich control, where mechanical adaptability and sensor feedback play a central role. Impedance and force control methods [

40] and point cloud/deep learning affordance-based strategies [

41] are representative of this line of research. Although these approaches rely on the physical interaction between the hand and the object, they often require precise integration and calibration of sensors such as force/torque sensors, tactile arrays, or high-resolution joint encoders. In contrast, the strategy proposed in this work explores the natural compliance of the robotic hand and the integration of contact sensors to allow the fingers to directly conform to the geometry and properties of the object. This reduces the dependency on explicit grasp pose generation or high-dimensional RL, while still providing robustness through tactile sensing and closed-loop control.

2.3. Tactile Sensing Technologies

Tactile feedback is essential for adaptive and safe robotic manipulation, providing critical information about contact forces, slip, and object properties [

42,

43,

44]. Several sensing technologies have been developed for robotic hands, each with distinct advantages and trade-offs. Magnetic-based tactile sensors provide high precision and robustness by exploiting magneto-elastomer composites or Hall-effect sensing [

45]. Their durability and ability to measure multi-axis forces are attractive for dexterous hands. However, they are costly and sensitive to electromagnetic interference, which can complicate compact integration. Conductive polymer sensors offer lightweight, flexible solutions by detecting deformation-induced changes in electrical conductivity [

46]. These sensors are inexpensive and conformable to curved surfaces, but they typically suffer from nonlinear responses and drift over time.

Piezoelectric sensors, such as PVDF-based films, are effective for measuring dynamic forces and vibrations [

47], making them useful for slip detection and texture recognition. However, they are less suited for static force measurement and require complex signal conditioning circuitry. Piezoresistive tactile sensors are among the most widely used in robotic hands due to their compact form factor, mechanical flexibility, and low cost [

17]. Force Sensitive Resistors (FSRs), in particular, have been extensively deployed, as they change resistance in proportion to applied pressure and are straightforward to integrate into curved surfaces such as fingertips or palms [

48,

49].

After evaluating these alternatives, FSR sensors were selected for this project as the more adequate solution for tactile sensing. Although they exhibit limitations in precision, hysteresis, and long-term stability, their ease of integration, small footprint, and adequate real-time performance make them well-suited for low-cost robotic hands requiring reliable contact detection.

3. Contact Sensor Integration

The development of a contact force detection system is a fundamental step in endowing the robotic hand with tactile sensing capabilities, enabling more natural and precise interaction with the environment. In this context, resistive force sensors (FSRs) were adopted due to their compactness, low cost, and ease of integration into small contact surfaces. This section describes the integration, conditioning, and programming of these sensors, as well as the experimental tests carried out to validate their performance under representative conditions of use.

3.1. FSR Sensor System Implementation

The integration of tactile sensing into the robotic hand was achieved through the incorporation of Force Sensitive Resistor (FSR) sensors. These sensors were positioned at the fingertips to allow for contact detection during grasping tasks. Their small size and ease of integration made them a suitable choice for the compact geometry of the LEAP Hand, while providing a straightforward method to estimate the magnitude of forces applied at the fingertip level.

To ensure accurate signal acquisition, a dedicated conditioning circuit was developed for the FSR sensors. Each sensor is embedded within a voltage divider configuration, where the variable resistance of the FSR is translated into a measurable voltage output. This design allows for a reliable conversion of contact forces into analog signals, minimizing noise while maintaining the sensitivity required for grasp analysis. Particular attention was paid to the selection of resistor values to balance resolution and dynamic range, ensuring that both light and firm contacts could be effectively detected. The conditioned signals are then processed by a microcontroller, which is programmed to continuously read the analog input of all sensors. The firmware handles sampling, preprocessing, and communication with the robotic control system. Data are transmitted via serial communication to the main ROS 2 framework, where they are published on a dedicated topic for further use in grasp monitoring and control. Additionally, the microcontroller is programmed to log sensor readings with timestamps into CSV files, enabling offline analysis and validation of sensor performance.

This workflow, from mechanical integration to signal conditioning and software implementation, results in a modular and extensible tactile sensing subsystem. It not only enables real-time monitoring of contact events but also provides the foundation for evaluating the contribution of tactile feedback to grasp stability and adaptability in the robotic hand.

3.2. Sensor Testing and Validation

Following the integration of the FSR sensor subsystem, a series of experiments are conducted to validate sensor performance and evaluate the system under conditions that resemble the actual robotic hand operation. These tests are designed to assess both the individual sensor response and the behavior of the system with multiple sensors activated simultaneously. The initial characterization tests were performed on a test bench before the sensors were mounted on the robotic hand. This allows for controlled and reproducible conditions to verify the functionality and reliability of the sensor circuit.

The first set of experiments involves connecting four FSR sensors to the microcontroller and applying forces individually to each sensor. This allows for the verification of the independent response of each sensor and that the activation of one sensor do not interfere with the readings of the others.

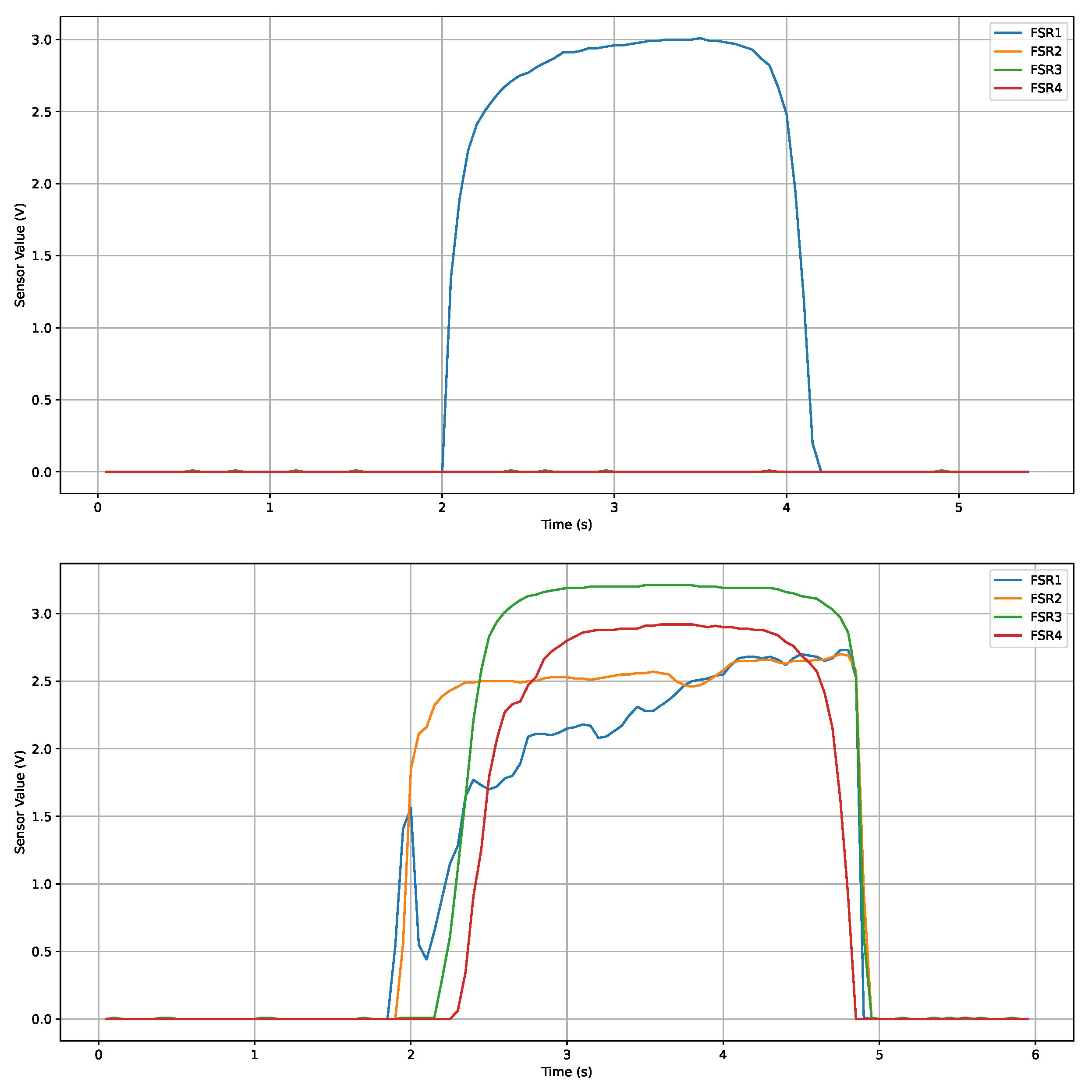

Figure 1(top) shows the output voltage during the application of a force on one of the sensors. The observed behavior is consistent across all sensors, with a clear increase in voltage output upon application of force. Non-activated sensors remain stable with minor residual fluctuations (approximately 0.01 V), which do not affect the system’s performance.

Subsequently, forces are applied simultaneously to multiple sensors to simulate real grasping conditions.

Figure 1(bottom) illustrates the time evolution of the output voltage when an external force is applied simultaneously to four sensors. These tests confirm that the system reliably capture concurrent contact events and sensor readings remain consistent, as well as the system’s ability to accurately distinguish forces applied at different fingertips. The effective sampling rate was measured at approximately 1000 Hz, ensuring sufficient temporal resolution for real-time applications.

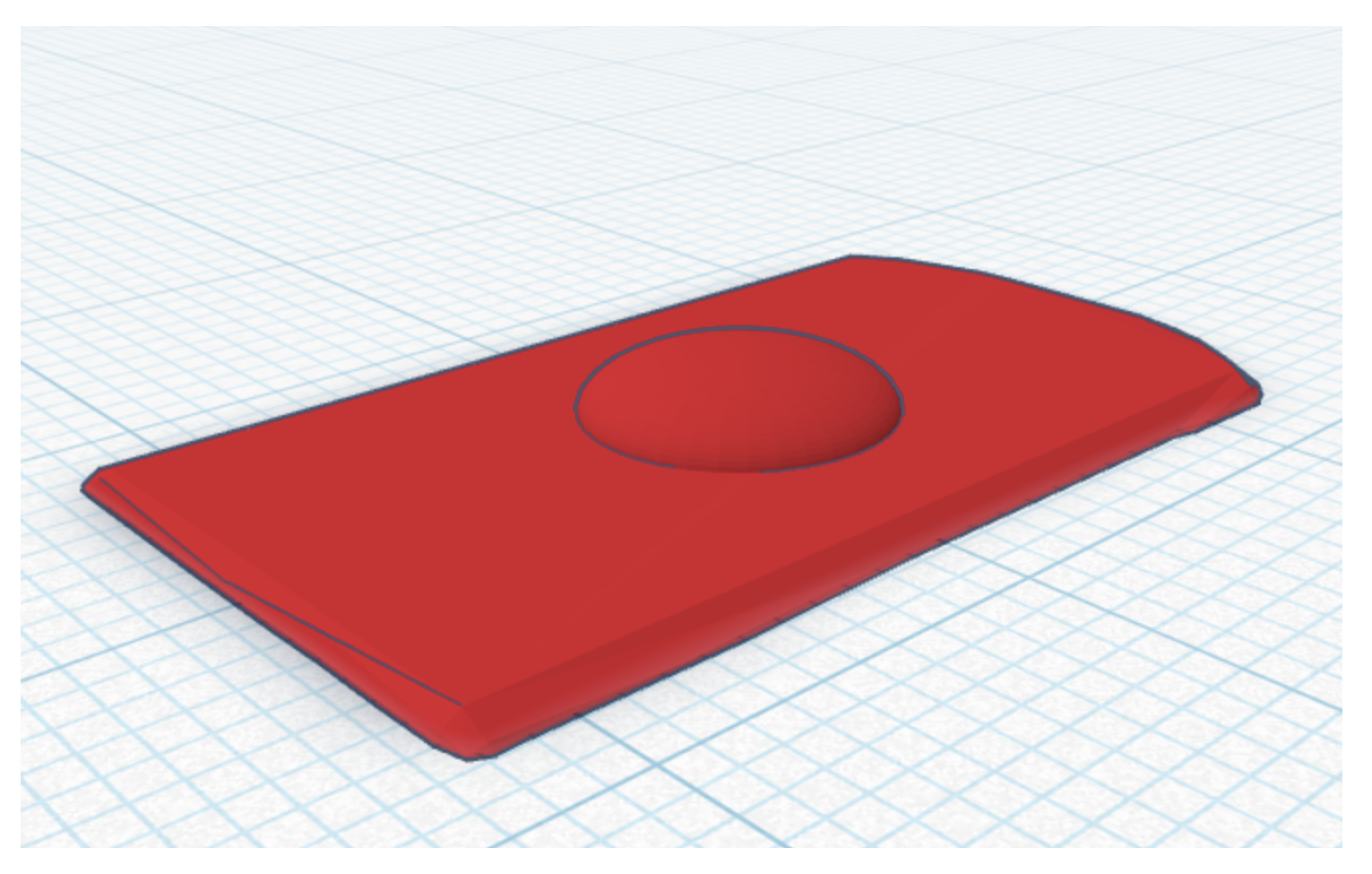

Preliminary testing revealed that the relatively small and flat sensors did not consistently capture forces applied on the curved fingertip surfaces of the LEAP Hand. To address this, a 3D printed force propagation element was designed and installed between the fingertip and each sensor. This component features a semi-spherical protrusion aligned with the active area of the sensor (see

Figure 2), ensuring that contact forces, even if applied off-center, are effectively transmitted to the sensor’s surface. The integration of this element significantly improves sensor response during grasping tasks.

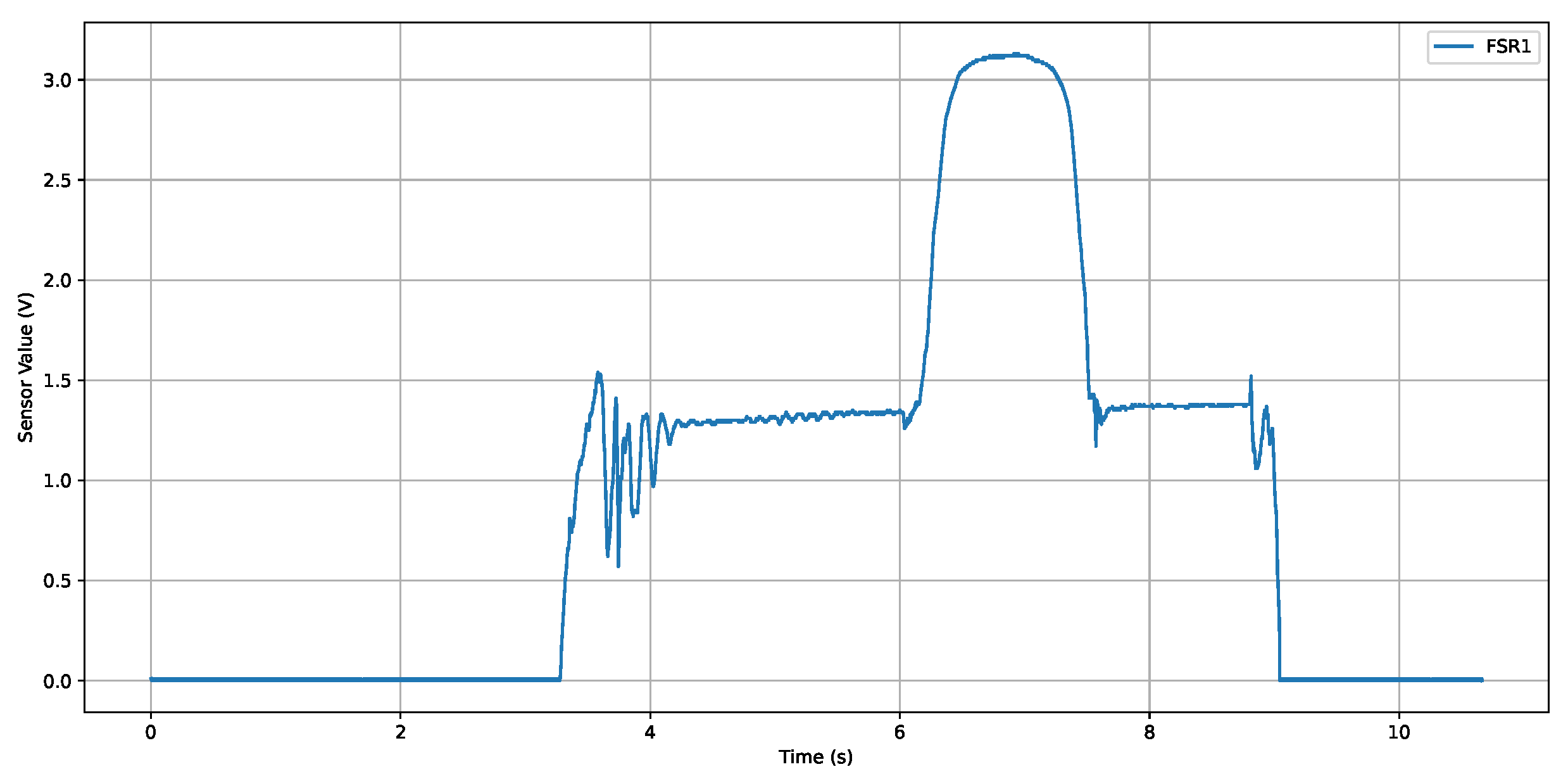

The FSR 406 sensor, which features a larger detection area than the FSR 400 units, is evaluated for its ability to detect distributed forces on its surface. To assess this behavior, a specific experiment was designed: an object of known mass was first placed on a specific region of the sensor’s active area. Following this initial load, a second force was applied to a distinct point on the sensor to analyze the system’s response to the simultaneous application of forces in multiple zones. The observed outputs confirm that the sensor accurately sums the forces applied in multiple zones (

Figure 3), demonstrating its suitability to capture distributed contact. However, initial signal oscillations highlighted the importance of stable sensor mounting for reliable measurements.

4. Control Architecture and System Implementation

This section describes the hardware and software architecture of the robotic platform, detailing the progression from single-motor operation to full-hand coordination. The architecture is implemented in a modular ROS 2 framework, enabling adaptive and scalable operation. Key features include dynamic current limiting, relative velocity scaling across fingers and phalanges, temporal offsets for gesture sequencing, and predictive finger coordination through a machine learning pipeline. The control strategy is based on synchronizing finger motions toward predefined positions, exploiting the hand’s inherent adaptability to conform to the geometry of objects during grasping.

4.1. Hardware Overview

The LEAP Hand comprises 16 Dynamixel XC330-M288-T servomotors [

25], chosen for their reliability, compact form factor, and precise control over position, velocity, and current. Each motor features a 12-bit encoder (4096 ticks per rotation, 0.088° per tick) and supports current-based position control, enabling compliant and reproducible finger movements. Motor parameters are accessed via a control table divided into EEPROM (permanent configuration) and RAM (dynamic states such as position, velocity, and current), providing flexible and efficient management of the actuators.

The motors are powered by a stabilized 5 V, 30 A industrial supply to accommodate simultaneous operation of all actuators, and communication is handled via the Dynamixel U2D2 USB-to-TTL converter, allowing daisy-chained control of multiple motors with high-speed serial communication (up to 4.5 Mbps). The UR10 robotic arm serves as a support structure for the LEAP Hand during data acquisition and experimental testing, enabling a precise and repeatable positioning of the hand in the workspace.

4.2. Motor Control Interface

Each motor is initialized by configuring the serial communication interface using the Dynamixel SDK through the PortHandler and PacketHandler objects. Once the port is opened and connectivity verified, torque is enabled to allow motor response. Motor parameters such as position, speed, and current can then be read and written via SDK functions (read2ByteTxRx(), read4ByteTxRx(), etc.). Positions are represented in ticks rather than degrees; for the XC330-M288-T, a 12-bit encoder provides 4096 discrete positions over a full rotation (approximately 0.088 inches per tick). The conversion to degrees is performed using . The velocity is represented similarly in ticks and converted to RPM using a factor of 0.229, with sign indicating rotation direction. Current consumption, provided in milliamperes, reflects the torque applied by the motor.

Each finger integrates four motors, requiring synchronous reading of motor states and simultaneous command transmission. The SDK functions sync_read and bulk_write are used for this purpose. sync_read allows efficient acquisition of position, velocity, and current for multiple motors at once ( 50 Hz), while bulk_write provides flexible command dispatch to all actuators. Motors operate in Current-Based Position Control Mode, with a maximum current set at initialization. Although direct velocity control is not possible, the Profile Velocity parameter limits motion speed.

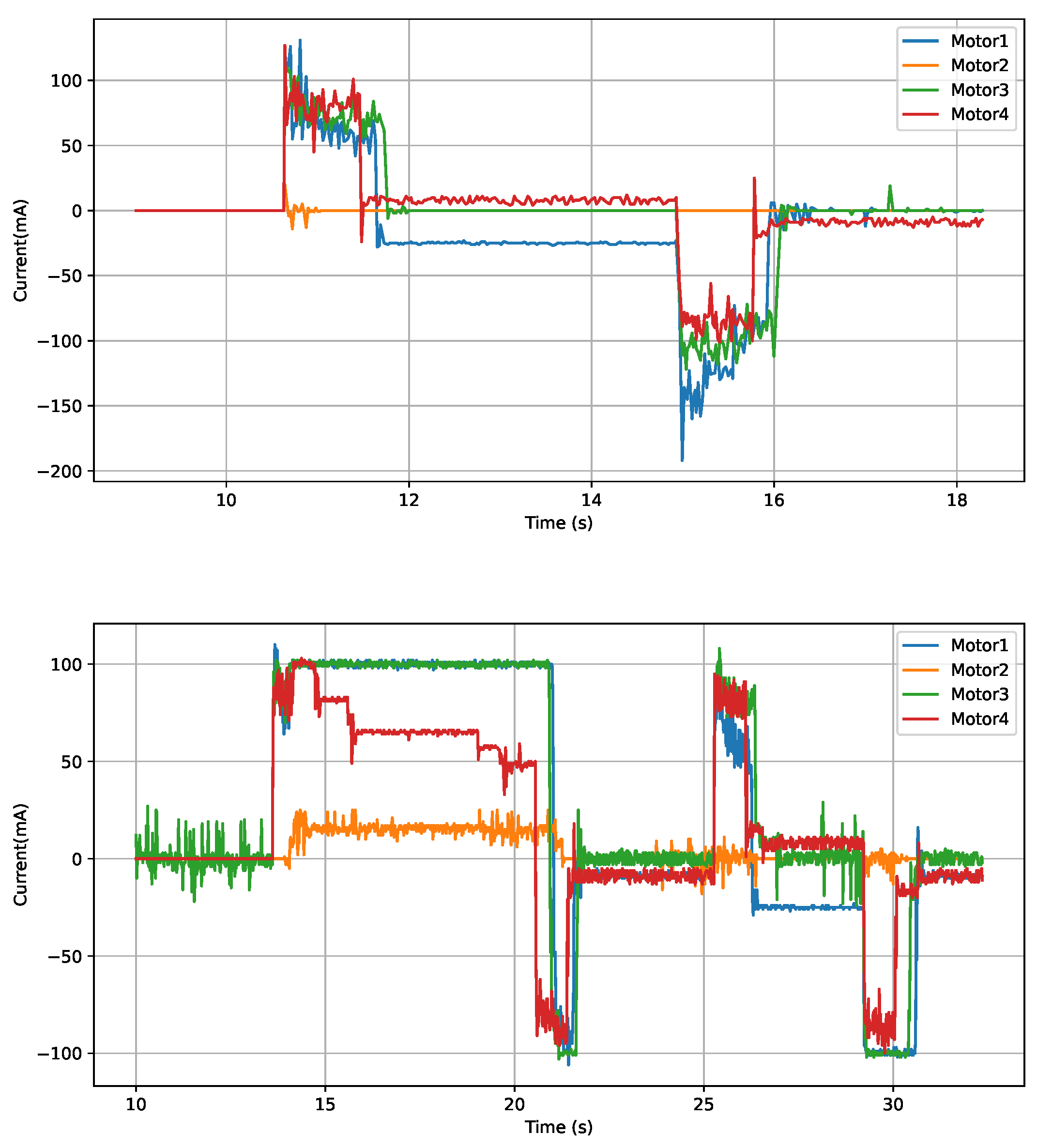

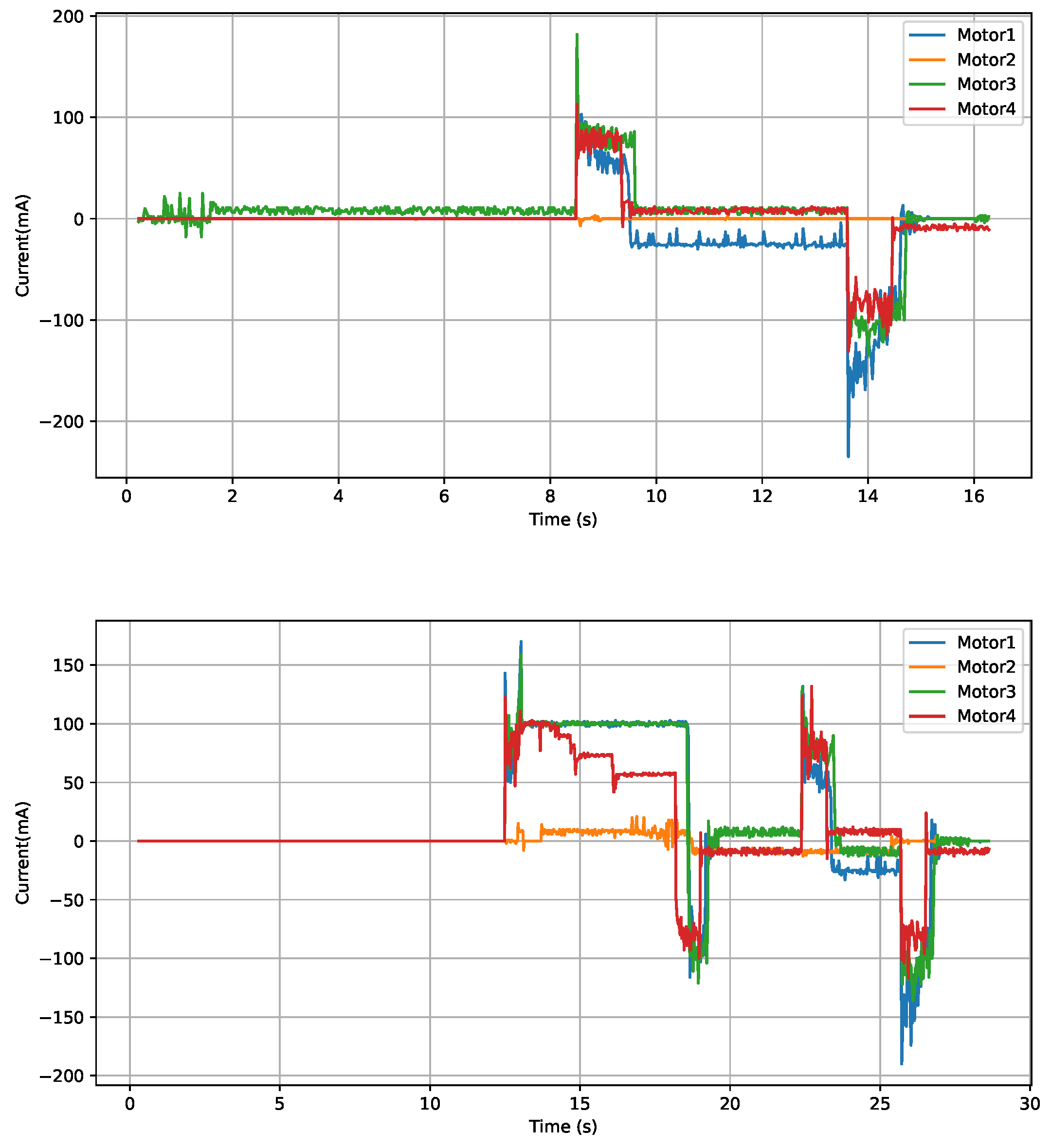

Experiments under both free-motion and obstacle interaction confirm that the "Current-Based Position Control" mode effectively prevents excessive force application without compromising the hand’s operational capabilities. To evaluate the motors’ behavior under ideal conditions, predefined target positions were commanded to induce a closing and subsequent opening movement of the finger, with a current limit of 100 mA defined for all motors. The graphs of the current consumption resulting from this "free motion" experiment are presented in

Figure 4(top). As observed, throughout the entire movement, the current values remain within the specified limits.

In the subsequent experiment, the same target positions are maintained, but a physical obstacle is introduced to impede the intended movement. Data analysis reveals clear differences between the two scenarios. In the presence of the obstacle, the finger is unable to reach the target position, resulting in an early stabilization of its position and a cessation of velocity. Simultaneously, a significant increase in consumed current is observed, as illustrated in

Figure 4(bottom), clearly indicating the effort of the motor against resistance without ever exceeding the defined current limit. Upon removal of the obstacle, the system resumes normal movement, reaching the desired position with greater stability and lower energy consumption. These results demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of the "Current-Based Position Control Mode." It successfully limits the force exerted by the motors during interaction with the environment, which is fundamental for applications where safety and adaptability to object contact are essential, such as compliant robotic manipulation.

The modular design allows seamless extension from single-finger control to full-hand operation. Automatic motor detection and instantiation of nodes for each finger enable coordinated control of all actuators. The same logic applied to individual fingers ensures consistent and synchronized operation throughout the entire hand, forming a solid basis for advanced functionalities such as dynamic current limiting, relative velocity control, and temporal offsets between finger movements.

4.3. Software Architecture

The software architecture was designed to ensure modularity, scalability, and robustness in the control of the robotic anthropomorphic hand. A modular structure based on ROS2 nodes was developed to coordinate hand operation, allowing a clear separation of responsibilities and facilitating extensibility and independent testing of system components.

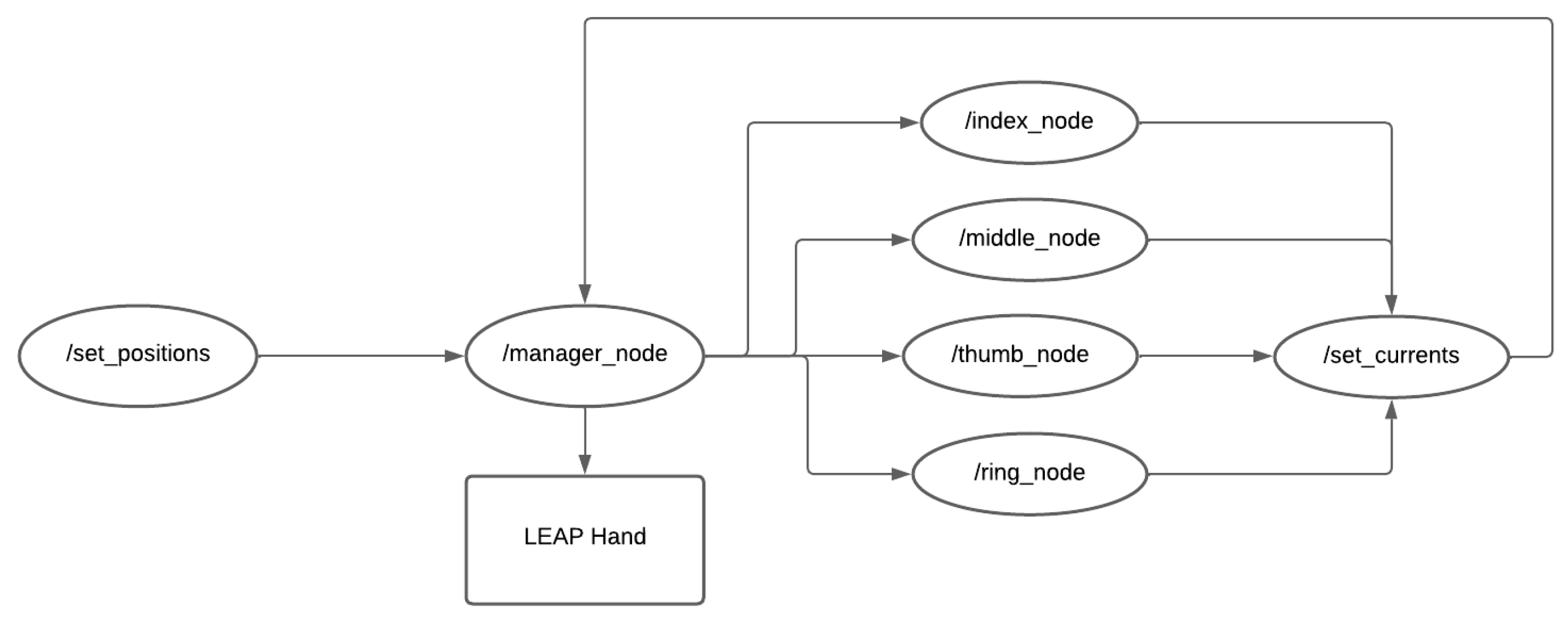

Figure 5 shows the ROS2 control architecture, illustrating the interaction between the nodes and the communication with the hardware.

At the top level, the system receives the target positions through the

set_positions_node, which acts as a high-level interface between the user and the robotic hand. These commands are then forwarded to the central

manager_node, responsible for coordinating all communication with the Dynamixel actuators. This node not only transmits target positions or current limits to motors, but also periodically retrieves their states (position, velocity, and current). For modularity,

manager_node distributes sensor data to finger-specific nodes (

thumb_node,

index_node,

middle_node, and

ring_node). Each node processes and controls its respective subset of motors, enabling both independent and coordinated control across fingers.

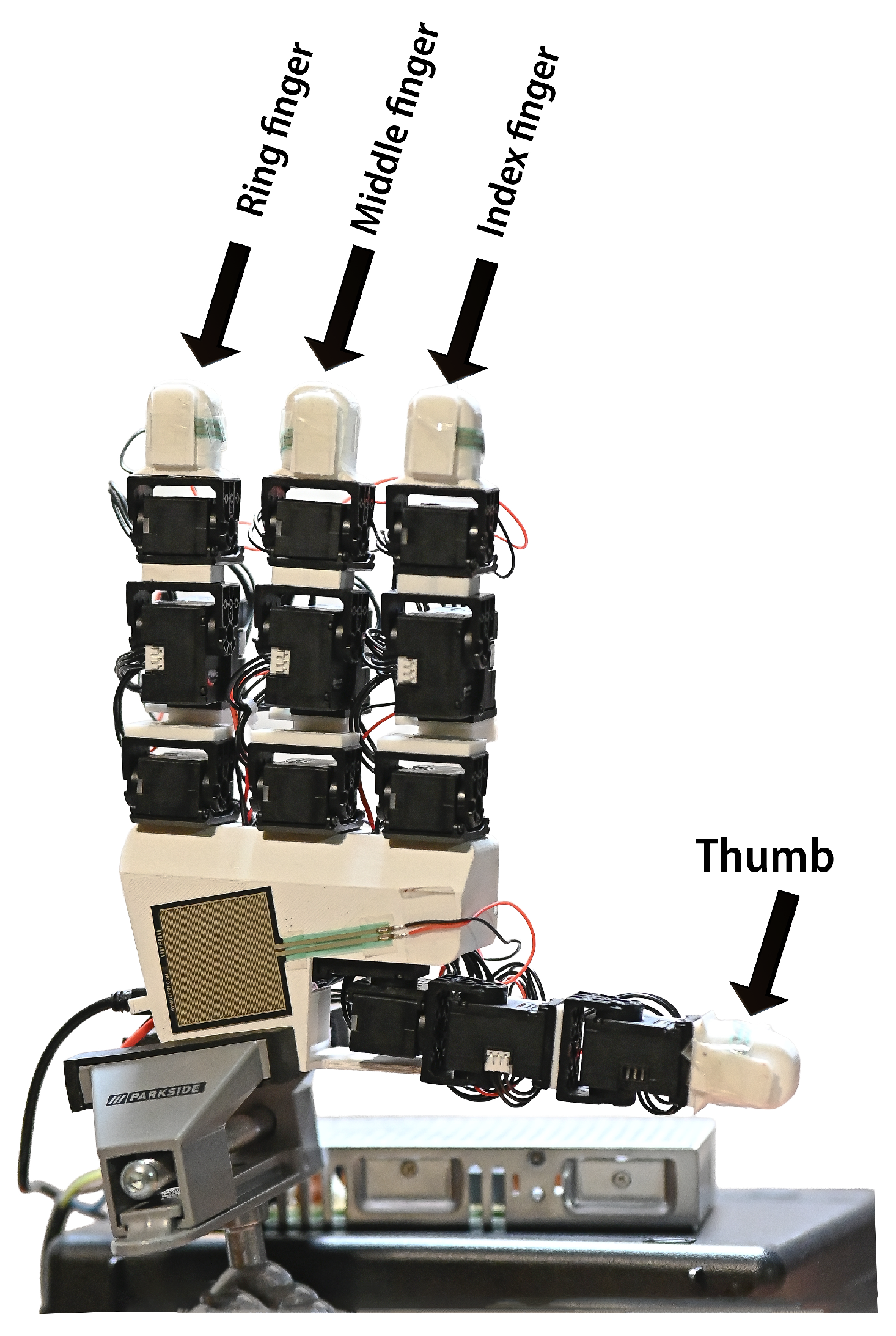

Figure 6 illustrates the robotic hand with its fingers clearly identified, which facilitates understanding of the modular structure of the nodes responsible for controlling each finger.

The proposed structure simplifies the integration of force sensors and other advanced functionalities, such as current-based safety mechanisms or relative motion strategies. Regarding contact sensors, a dedicated

fsr_sensor_node is developed to integrate the tactile data into the ROS-based system. This node establishes a serial connection with the microcontroller managing the force-sensitive resistors (FSRs) in the fingers and palm. It continuously reads sensor values and publishes them on the ROS topic

fsr_sensor_values, providing real-time tactile feedback for grasp regulation and collision detection. Additionally, all acquired sensor readings are recorded in a timestamped CSV file, enabling offline analysis, model validation, and further feature engineering for the overlap detection pipeline.

This integration of force sensors and a machine learning pipeline allows the control system to combine kinematic and tactile information, improving the adaptability and robustness of the hand in handling a variety of objects. Additionally, to streamline system deployment, a launch file was created to automatically initialize the main nodes and ensure proper synchronization of processes. This automation reduces the startup complexity and ensures a consistent system configuration across experimental sessions. Overall, the proposed architecture provides a hierarchical and modular control framework, ensuring reliable operation, facilitating the addition of new functionalities, and enabling flexible experimentation with different levels of hand control.

To evaluate the communication performance of the developed ROS2 framework, particular attention was paid to latency and synchronization. The synchronous read and bulk write operations provided by the Dynamixel SDK ensured that all motor states were acquired and updated within a single communication cycle, minimizing temporal offsets between fingers. Experimental measurements indicated an effective loop frequency of approximately 50 Hz, which proved sufficient for coordinated multi-finger operation. Occasional packet losses or delays are handled by the

manager_node through retry mechanisms, preventing desynchronization between actuators. Furthermore, the modular distribution of responsibilities across nodes ensure that a local failure (e.g., a single finger node crash) did not compromise the operation of the entire system, highlighting the robustness of the architecture under real experimental conditions.

4.4. Advanced Functionalities

The modular architecture supports three additional features that improve safety and efectiveness. First, the system allows one to assign relative velocity factors across fingers and within finger phalanges. For example, the thumb can reach its target position before other fingers, or the base phalanx can move faster than the fingertip, enabling natural coordinated gestures. Experiments with varied velocity ratios demonstrate that relative scaling produces realistic motion sequences, which influence both timing and mechanical interaction between fingers. Second, temporal offsets between finger movements replicate human-like sequential coordination. Commands are dispatched according to predefined offsets, allowing gestures such as a “wave” where fingers close sequentially with specific delays and symmetric motions with offset inversion during hand reopening. The resulting gestures illustrate flexible and contextually adaptive finger coordination.

One of the primary challenges in manipulating objects with anthropomorphic robotic hands is the ability to grasp sensitive or deformable items without causing damage, while simultaneously maintaining a stable grip. Excessive force application can lead to crushing or irreversible deformation of objects, thus necessitating the implementation of adaptive control mechanisms that regulate applied force in real-time. To address this, a third functionality for dynamic adjustment of the current limit in the motors was developed. This feature automatically restricts the effort exerted by the motors whenever contact with an object is detected. This is achieved by adapting the control code for each individual finger, allowing them to autonomously adjust their current limits based on two main criteria: a significant increase in consumed current and a notable decrease in motor acceleration.

The detection of increased current is based on the comparison of the measured current for each finger motor against a predefined maximum value, termed

GOAL_CURRENT_VALUE, set within the control node. If any measured current exceeds this threshold, it indicates that the motor is under excessive load. Crucially, contact with an obstacle is defined as occurring when both a significant increase in current and a substantial reduction in acceleration are simultaneously observed. This dual criterion approach indicates that the motor is applying force without achieving its intended positional advance, thereby confirming contact with an object. Upon such detection, the current limit value is adjusted iteratively downwards until the system stabilizes at the

GOAL_CURRENT_VALUE. A key requirement for optimal performance of this strategy is the pre-definition of appropriate settings, which are typically object-specific and may necessitate prior knowledge or object recognition during grasping tasks.

To validate this functionality, an experiment was conducted in which an obstacle was intentionally introduced to impede the movement of one of the robotic hand’s fingers.

Figure 7 shows the currents consumed for the four motors of a single finger in two scenarios: without (top) and with (bottom) the obstacle. In this experiment, the initial current limit is set to 200 mA, while the dynamically adjusted current limit upon contact detection is set to 100 mA. Analysis of the graphs reveals that during free-finger movement (without an obstacle), current peaks exceeding 100 mA are observed. These are normal, reflecting the effort required by the motors to overcome the mechanical resistance of the system. However, the moment the finger encounters the obstacle, the current stabilizes precisely at 100 mA. This clearly reflects the successful detection of contact with the obstacle and the consequent adaptive reduction of the current limit implemented by the control system. Upon removal of the obstacle, transient current peaks exceeding 100 mA are once again registered, which indicates that the actuator is no longer constrained and the finger is allowed to resume its normal movement, with the initial current limit being automatically re-established.

5. Overlap Detection

To address the problem of undesired finger overlaps during the hand opening sequence, we explore a supervised machine learning approach to classify three critical configurations: no overlap, overlap with thumb underneath, and overlap with thumb on top. In order to assess the scalability of our approach and anticipate future extensions involving a greater number of overlap categories or more complex motion patterns, we implement a fully connected neural network (NN) classifier. Neural networks offer greater flexibility in modeling high-dimensional feature spaces and are particularly advantageous when scaling to larger datasets or multiclass problems. Including this classifier serves to establish neural networks as a promising direction for scaling toward richer representations of hand configurations, namely anatomically inspired coordination strategies.

5.1. Data Preparation

The development of reliable machine learning models for overlap detection required the creation of a representative dataset of robotic hand configurations. To this end, we designed and implemented a systematic data acquisition pipeline that combines motor signals and tactile sensing with automated motion routines. Dynamixel servomotors provide several real-time parameters, including angular position, velocity, current, and internal status variables. For overlap detection purposes, we selected joint positions and motor currents as the most informative features. Angular positions directly describe the posture of the hand, whereas current variations reflect external resistance or contact events. In addition, distributed piezoresistive tactile sensors integrated in the fingertips and palm were included, providing complementary information about physical contact and enabling robust characterization of finger–finger and finger–object interactions. This combination of joint, current, and tactile data ensured a balance between descriptive richness and computational tractability.

To promote variability and robustness, data were collected using three objects with different geometries: a sphere, a cylindrical case, and a Rubik’s cube. Each object was tested in eight different spatial orientations, repeated ten times, resulting in a diverse set of contact conditions influenced by object shape, gravity, and hand posture. In order to cover the most relevant overlap scenarios observed during operation, three classes of finger configurations are defined:

Class 0 – No overlap: fingers open and close without interference, representing nominal operation.

Class 1 – Thumb underneath: the thumb collides with another finger, physically below it.

Class 2 – Thumb on top: overlap occurs with the thumb located above the contacting finger(s).

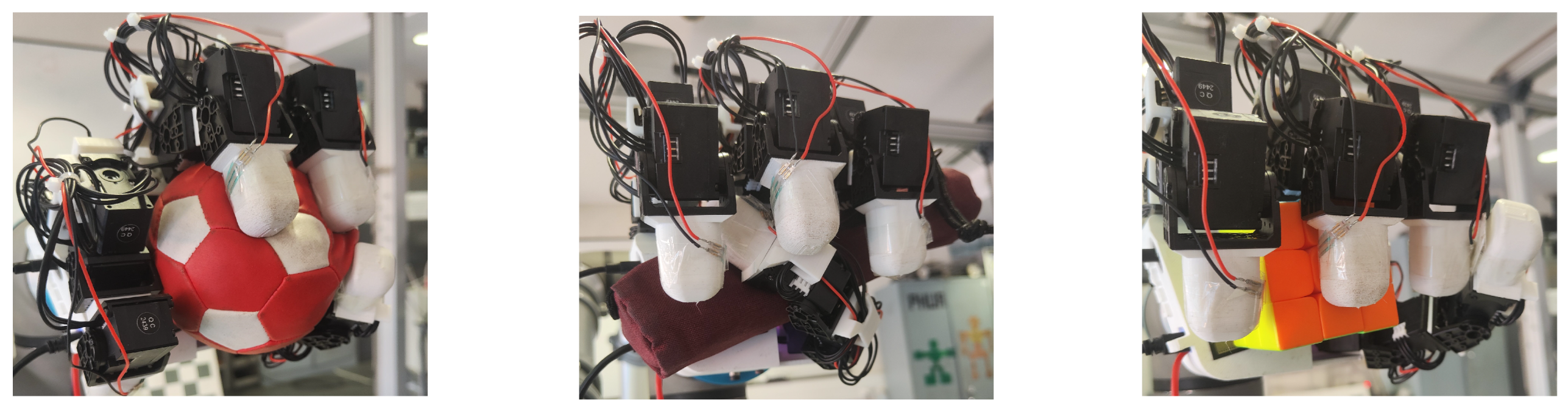

As illustrated in

Figure 8, these classes reflect typical interaction patterns that can compromise safe and reliable hand operation when grasping the selected objects. Correct identification enables informed control decisions, such as modifying the sequence of finger extension to avoid collisions. Data collection was automated through ROS2 nodes. Specific command inputs (0, 1, 2) triggered predefined opening and closing routines that systematically reproduced the three overlap scenarios. A dedicated acquisition node subscribed to motor and sensor topics and stored data only when physical contact was detected, as indicated by current adjustments or tactile sensor activation. This ensured that only relevant interaction events were recorded. The final dataset comprised 6,234 unique samples, each corresponding to a distinct interaction configuration. Each sample included synchronized motor position and current data, tactile readings, and the associated overlap class label. The dataset thus provides a comprehensive and diverse basis for training and evaluating machine learning models for overlap detection.

5.2. Neural Network Architecture

A fully connected neural network (NN) was developed and implemented to assess its effectiveness in addressing the overlap detection problem and to investigate its potential for scalability to more complex classification tasks. The dataset consists of 37 numerical features per sample, including motor joint positions, motor currents, and tactile sensor readings. The class distribution is relatively balanced, with 27.8% of samples belonging to Class 0 (no overlap), 35.7% to Class 1 (thumb underneath), and 36.6% to Class 2 (thumb on top), thus reducing the risk of bias during training.

For model development, the dataset is split into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets, ensuring that performance is evaluated on previously unseen data. To further improve reliability, we apply stratified 10-fold cross-validation during training, which provides a more robust estimate of the model’s generalization capability and mitigated the variance associated with a single train–test split.

A multilayer perceptron (MLP), a type of feedforward neural network, was implemented in TensorFlow/Keras using a standard fully connected architecture. The network comprises a single dense hidden layer, with the number of units and activation function selected via hyperparameter optimization, followed by a dropout layer to mitigate overfitting by randomly deactivating a fraction of units during training. The output layer contains three neurons corresponding to the three overlap classes and employs softmax activation to produce a normalized probability distribution across classes.

The training objectives are defined as sparse categorical cross-entropy, a robust loss function suitable for multiclass classification. It is optimized with the Adam optimizer due to its efficiency in high-dimensional parameter spaces and adaptive learning rate adjustment. Hyperparameters were tuned using the Optuna optimization framework, employing a Bayesian search strategy over 120 trials. This search considers a range of critical architectural and training parameters, including specifically the number of hidden units, the choice of activation function (ReLU or tanh), the dropout rate, the learning rate, and the batch size. The best performance configuration, identified through this optimization process, is summarized in

Table 1. The final model consequently uses 66 hidden units with ReLU activation, a learning rate of 0.002, a batch size of 16, and no dropout, reflecting a highly optimized and streamlined architecture for the specific classification task.

5.3. Results

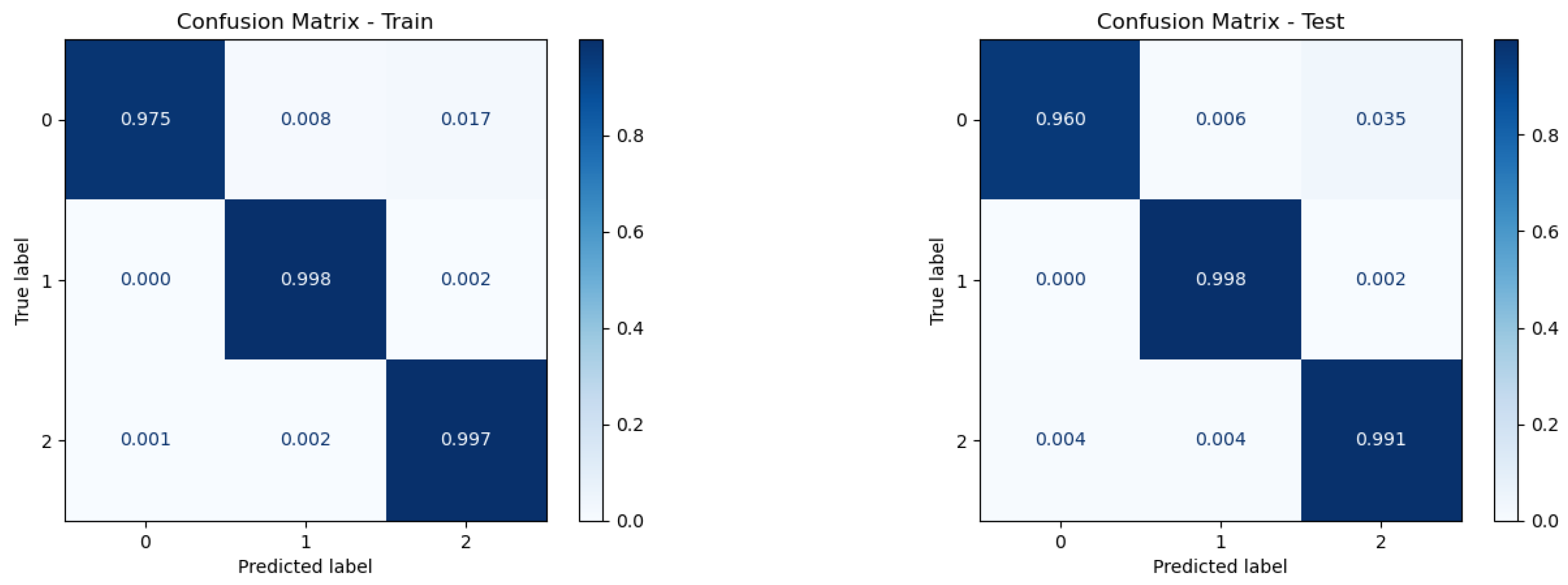

The performance of the neural network is evaluated using standard multiclass classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Additionally, confusion matrices provide a more complete analysis in terms of class-specific errors. The model achieved 99.2% accuracy on the training set and 98.5% on the test set, indicating strong generalization capability. Confusion matrices (

Figure 9) show consistently high per-class accuracy, with residual misclassifications primarily between classes 0 and 2. Class 1 achieved near-perfect recognition in both the train and test sets, while class 0 exhibited a slightly lower recall due to misclassifications into class 2 (around 3.5% in the test set).

Detailed metrics for the test set are summarized in

Table 2. All classes achieve F1-scores above 0.97, with macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score exceeding 98%. These results confirm the model’s robustness and its ability to capture class-specific patterns with minimal loss of generalization. Overall, the neural network demonstrates highly competitive performance, with only marginal degradation from training to test and minimal inter-class confusion. These findings highlight the suitability of the approach for scalable overlap detection in multi-fingered robotic hands.

6. Conclusions

This work presented the design, implementation, and validation of an anthropomorphic robotic hand aimed at compliant grasping and intelligent control. Building on the LEAP Hand platform, we developed a complete pipeline that integrates hardware instrumentation, modular software control, distributed tactile sensing, and a machine learning approach for predictive finger coordination. The integration of piezoresistive force sensors on the fingertips and palm proved to be effective in detecting contact, providing tactile information in real-time to support compliant manipulation. Combined with a modular ROS 2-based control architecture, the system enables flexible sensor-actuator integration, supports reproducible experimentation, and offers a basis for extensible control strategies. The adoption of current-based position control further improved the adaptability of the hand by allowing passive compliance without the need for complex active force regulation.

The challenge of undesired finger overlaps during hand opening was addressed through a machine learning pipeline based on a multilayer perceptron classifier. By systematically collecting and labeling sensorimotor data, the system achieved a classification performance above 98% in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. This demonstrates the feasibility of predictive overlap detection as a safeguard against internal collisions and mechanical stress, paving the way for robust and safe coordination of anthropomorphic robotic hands. Overall, the results highlight the potential of combining compliant actuation, distributed tactile sensing, and data-driven prediction to advance the robustness, adaptability, and intelligence of anthropomorphic robotic hands.

Future work will focus on extending the predictive capabilities of the classifier into closed-loop control, enabling proactive adjustment of finger trajectories before overlaps occur. Additional directions include refining tactile sensing with higher-resolution sensors, exploring adaptive learning methods to generalize across diverse manipulation tasks, and integrating the system into broader human-robot interaction contexts. The dynamic current limit adjustment represents a significant advancement in the safety and adaptability of the robotic hand, enabling more delicate and controlled interactions with objects of varying physical properties. Future work will also explore machine learning approaches to autonomously infer or learn appropriate

GOAL_CURRENT_VALUE settings based on real-time sensor feedback and object properties, thereby reducing the reliance on pre-defined parameters and enhancing the hand’s adaptability to novel objects.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marwan, Q.M.; Chua, S.C.; Kwek, L.C. Comprehensive review on reaching and grasping of objects in robotics. Robotica 2021, 39, 1849–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortenzi, V.; Cosgun, A.; Pardi, T.; Chan, W.P.; Croft, E.; Kulić, D. Object handovers: a review for robotics. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2021, 37, 1855–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Silva, F.; Santos, V. Trends of human-robot collaboration in industry contexts: Handover, learning, and metrics. Sensors 2021, 21, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Advancements in humanoid robots: A comprehensive review and future prospects. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2024, 11, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.H.; Chen, W.R.; Sun, B.Y.; Liu, M.J.; Yue, S.G.; Chen, W.B. Design and implementation of an anthropomorphic hand for replicating human grasping functions. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2016, 32, 652–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Todorov, E. Design of a highly biomimetic anthropomorphic robotic hand towards artificial limb regeneration. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2016; pp. 3485–3492. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Chang, U.; Lu, J.T.; Leung, C.C.Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z. A soft-robotic approach to anthropomorphic robotic hand dexterity. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 101483–101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.; Jung, D.; Jeong, H.; Park, J.; Jung, H.M.; Cheong, J.; Choi, H.R.; Do, H.; Park, C. Integrated linkage-driven dexterous anthropomorphic robotic hand. Nature communications 2021, 12, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.K.; Wang, N.; Wu, H.; Yang, C. Review on human-like robot manipulation using dexterous hands. Cogn. Comput. Syst. 2023, 5, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama Melo, E.N.; Aviles Sanchez, O.F.; Amaya Hurtado, D. Anthropomorphic robotic hands: a review. Ingeniería y desarrollo 2014, 32, 279–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorri, C.; Kaneko, M. Robot hands. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Springer, 2016; pp. 463–480.

- Piazza, C.; Grioli, G.; Catalano, M.G.; Bicchi, A. A century of robotic hands. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems 2019, 2, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Controzzi, M.; Cipriani, C.; Carrozza, M.C. Design of artificial hands: A review. In The Human Hand as an Inspiration for Robot Hand Development; 2014; pp. 219–246. [Google Scholar]

- Billard, A.; Kragic, D. Trends and challenges in robot manipulation. Science 2019, 364, eaat8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, R.; Xu, P.; Ye, Q.; Chen, J. The Developments and Challenges towards Dexterous and Embodied Robotic Manipulation: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.11840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Khamis, H.; Birznieks, I.; Lepora, N.F.; Redmond, S.J. Tactile sensors for friction estimation and incipient slip detection—Toward dexterous robotic manipulation: A review. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 9049–9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Atkeson, C.G. Recent progress in tactile sensing and sensors for robotic manipulation: can we turn tactile sensing into vision? Advanced Robotics 2019, 33, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Deng, Z.; Fang, B.; Yang, Y.; Sun, F. A review on sensory perception for dexterous robotic manipulation. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2022, 19, 17298806221095974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohg, J.; Morales, A.; Asfour, T.; Kragic, D. Data-driven grasp synthesis—A survey. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2014, 30, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswaran, A.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, A.; Vezzani, G.; Schulman, J.; Todorov, E.; Levine, S. Learning complex dexterous manipulation with deep reinforcement learning and demonstrations. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.10087 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nagabandi, A.; Konolige, K.; Levine, S.; Kumar, V. Deep dynamics models for learning dexterous manipulation. In Proceedings of the Conference on robot learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 1101–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, P. Dexterous manipulation for multi-fingered robotic hands with reinforcement learning: A review. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2022, 16, 861825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N. Impedance control: An approach to manipulation: Part II—Implementation. Journal of dynamic systems, measurement, and control 1985, 107, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keemink, A.Q.; Van der Kooij, H.; Stienen, A.H. Admittance control for physical human–robot interaction. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2018, 37, 1421–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; Agarwal, A.; Pathak, D. LEAP Hand: Low-cost, efficient, and anthropomorphic hand for robot learning. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Macenski, S.; Foote, T.; Gerkey, B.; Lalancette, C.; Woodall, W. Robot Operating System 2: Design, architecture, and uses in the wild. Science Robotics 2022, 7, eabm6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, I.M.; Ma, R.R.; Dollar, A.M. A hand-centric classification of human and robot dexterous manipulation. IEEE transactions on Haptics 2012, 6, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadow Robot Company. Shadow Dexterous Hand. https://www.shadowrobot.com/products/dexterous-hand/, 2023. Accessed: 2025-09-02.

- Wonik Robotics. Allegro Hand. https://www.wonikrobotics.com/research-robot-hand/, 2023. Accessed: 2025-09-02.

- Park, J.; Chang, M.; Jung, I.; Lee, H.; Cho, K. 3D Printing in the design and fabrication of anthropomorphic hands: a review. Advanced Intelligent Systems 2024, 6, 2300607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, D. An open-source anthropomorphic robot hand system: HRI hand. HardwareX 2020, 7, e00100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RobotNano Project. Robot Nano Hand. https://github.com/robotnano/hand, 2022. Accessed: 2025-09-02.

- Nurpeissova, A.; Tursynbekov, T.; Shintemirov, A. An open-source mechanical design of alaris hand: A 6-dof anthropomorphic robotic hand. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1177–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavian, A.; Eppner, C.; Fox, D. 6-DOF GraspNet: Variational Grasp Generation for Object Manipulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019; pp. 2017–2910. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.; Corke, P.; Leitner, J. Closing the Loop for Robotic Grasping: A Real-time, Generative Grasp Synthesis Approach. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS); 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbury, R.; Madan, C.; Walker, R.; Stolkin, R. Deep Learning Approaches to Grasp Synthesis: A Review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02556 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.; Gaber, M.M.; Elyan, E.; Jayne, C. Imitation learning: A survey of learning methods. ACM Computing Surveys 2017, 50, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Roveda, L.; Pedrocchi, N.; Molinari Tosatti, L. Object Manipulation With an Anthropomorphic Robotic Hand via Deep Reinforcement Learning in a Synergy Space. Sensors 2021, 21, 5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, H.; Adhar, D.; Shrawge, A.; Kanbaskar, P.; Hazarika, S.M. Reinforcement learning-based bionic reflex control for anthropomorphic robotic grasping exploiting domain randomization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.05023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, B.; Sciavicco, L.; Villani, L.; Oriolo, G. Robotics: Modelling, Planning and Control; Springer, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Wang, P.; Huang, Y.; Xu, G.; Wei, W.; Shen, X. Robotics dexterous grasping: The methods based on point cloud and deep learning. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2021, 15, 658280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.S.; Metta, G.; Valle, M.; Sandini, G. Tactile sensing—from humans to humanoids. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2009, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H.; Boukallel, M.; Althoefer, K. Tactile sensing for dexterous in-hand manipulation in robotics—A review. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2011, 167, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, M.I.; Redmond, S.J.; Lovell, N.H. A review of tactile sensing technologies with applications in biomedical engineering. Sensors and Actuators A: physical 2012, 179, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, J. Recent progress of biomimetic tactile sensing technology based on magnetic sensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.C.; Liatsis, P.; Alexandridis, P. Flexible and stretchable electrically conductive polymer materials for physical sensing applications. Polymer Reviews 2023, 63, 67–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, C.; et al. Conformal piezoelectric energy harvesting and storage from motions of the heart, lung, and diaphragm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J.S.; Evans, K.R.; Hebert, J.S.; Marasco, P.D.; Carey, J.P. The effect of biomechanical variables on force sensitive resistor error: Implications for calibration and improved accuracy. Journal of biomechanics 2016, 49, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.C.; Weathersby, E.J.; Cagle, J.C.; Sanders, J.E. Evaluation of force sensing resistors for the measurement of interface pressures in lower limb prosthetics. Journal of biomechanical engineering 2019, 141, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Output voltage of the FSR sensors over time, demonstrating the response to varying contact events. (Top) A single sensor is activated. (Bottom) The four sensors are activated simultaneously, confirming the system’s ability to reliably detect and distinguish concurrent contact events.

Figure 1.

Output voltage of the FSR sensors over time, demonstrating the response to varying contact events. (Top) A single sensor is activated. (Bottom) The four sensors are activated simultaneously, confirming the system’s ability to reliably detect and distinguish concurrent contact events.

Figure 2.

3D-printed force propagation element designed to improve sensor reliability. The semi-spherical protrusion transmits contact forces from the curved fingertip surface more effectively to the flat FSR sensor.

Figure 2.

3D-printed force propagation element designed to improve sensor reliability. The semi-spherical protrusion transmits contact forces from the curved fingertip surface more effectively to the flat FSR sensor.

Figure 3.

Output voltage of the FSR 406 sensor in response to sequential loads. The figure shows the sensor’s ability to accurately sum forces applied at distinct points on its surface, highlighting its suitability for detecting distributed contact.

Figure 3.

Output voltage of the FSR 406 sensor in response to sequential loads. The figure shows the sensor’s ability to accurately sum forces applied at distinct points on its surface, highlighting its suitability for detecting distributed contact.

Figure 4.

Current consumption of the motors of a single finger during a closing and opening sequence in free motion (top) and when movement is obstructed by a physical obstacle (bottom).

Figure 4.

Current consumption of the motors of a single finger during a closing and opening sequence in free motion (top) and when movement is obstructed by a physical obstacle (bottom).

Figure 5.

Modular ROS2-based control architecture of the robotic hand.

Figure 5.

Modular ROS2-based control architecture of the robotic hand.

Figure 6.

Robotic hand built from the open-source LEAP Hand project, with its fingers identified to illustrate the modular structure of the ROS nodes responsible for controlling each finger. The force sensors integrated in both the fingers and the palm are also illustrated.

Figure 6.

Robotic hand built from the open-source LEAP Hand project, with its fingers identified to illustrate the modular structure of the ROS nodes responsible for controlling each finger. The force sensors integrated in both the fingers and the palm are also illustrated.

Figure 7.

Current consumption of the four motors in a single finger over time, highlighting the effect of dynamic current limit adjustment. (Top) Without obstacle: typical current variations during free motion, with occasional peaks above 100 mA. (Bottom) With obstacle: upon contact, the system adapts by stabilizing the current at 100 mA, indicating successful contact detection and the subsequent reduction of the current limit.

Figure 7.

Current consumption of the four motors in a single finger over time, highlighting the effect of dynamic current limit adjustment. (Top) Without obstacle: typical current variations during free motion, with occasional peaks above 100 mA. (Bottom) With obstacle: upon contact, the system adapts by stabilizing the current at 100 mA, indicating successful contact detection and the subsequent reduction of the current limit.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the three objects and corresponding overlap classes used for data collection and training. Left: deformable rubber ball representing Class 0 (no overlaps). Middle: cylindrical pencil case representing Class 1 (overlap with thumb underneath). Right: rigid Rubik’s cube representing Class 2 (overlap with thumb on top).

Figure 8.

Illustration of the three objects and corresponding overlap classes used for data collection and training. Left: deformable rubber ball representing Class 0 (no overlaps). Middle: cylindrical pencil case representing Class 1 (overlap with thumb underneath). Right: rigid Rubik’s cube representing Class 2 (overlap with thumb on top).

Figure 9.

Confusion matrices of the multilayer perceptron (MLP) model: (left) training subset and (right) test subset. The results demonstrate high classification accuracy across all three overlap classes and strong generalization, with minimal signs of overfitting between training and test performance.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrices of the multilayer perceptron (MLP) model: (left) training subset and (right) test subset. The results demonstrate high classification accuracy across all three overlap classes and strong generalization, with minimal signs of overfitting between training and test performance.

Table 1.

Optimized hyperparameters for the multilayer perceptron used in overlap classification, including a dropout rate of 0 (indicating no dropout was applied).

Table 1.

Optimized hyperparameters for the multilayer perceptron used in overlap classification, including a dropout rate of 0 (indicating no dropout was applied).

| Hyperparameter |

Optimal Value |

| Hidden units |

66 |

| Activation function |

ReLU |

| Learning rate |

0.002 |

| Dropout rate |

0.0 |

| Batch size |

16 |

Table 2.

Performance metrics on the test set for the neural network.

Table 2.

Performance metrics on the test set for the neural network.

| Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| 0 |

0.994 |

0.960 |

0.976 |

| 1 |

0.991 |

0.998 |

0.994 |

| 2 |

0.972 |

0.991 |

0.982 |

| Macro Avg. |

0.986 |

0.983 |

0.984 |

| Weighted Avg. |

0.985 |

0.985 |

0.985 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).