1. Introduction

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a leading cause of infertility and metabolic dysfunction, characterised by irregular menstruation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries. Globally, PCOS affects 6–13% of reproductive-age women, with higher prevalence in urban India (8–22%) and potentially in African populations, such as the Igbo of Nigeria [

4,

5,

9]. James V. Neel’s thrifty gene hypothesis (1962) provides a framework to understand this disparity, suggesting that populations exposed to cyclic famines evolved genetic adaptations for efficient fat storage, which become maladaptive in modern, calorie-abundant settings [

11]. Epigenetic modifications (reversible changes in gene expression (e.g., DNA methylation)) extend this hypothesis, as nutritional stress can imprint metabolic vulnerabilities across generations, per the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) model [

1,

3,

6]. Historical famines, such as the Dutch Hunger Winter (1944–45) and Chinese Great Famine (1959–61), demonstrate prenatal starvation’s lasting metabolic impact [

7,

10].

India and Nigeria, with their shared histories of severe famine and rapid urbanisation, offer compelling case studies. In India, recurrent faminesfrom ancient monsoonal droughts to colonial-era crises (e.g., Bengal Famine, 1770; Great Famine, 1876–78)have been linked to elevated PCOS prevalence, particularly in urban settings where dietary shifts exacerbate insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism [

4,

5]. Studies report urban Indian PCOS rates of 17–22%, with 35% of cases showing impaired glucose tolerance and 70–80% experiencing infertility [

4,

9]. Similarly, the Biafran War (1967–1970) caused severe famine among the Igbo, with up to 2 million deaths due to starvation [

8,

12,

14]. Metabolic studies on Biafran survivors show increased risks of hypertension (OR 2.87), glucose intolerance (OR 1.65), and obesity (OR 1.41), suggesting a thrifty phenotype that may parallel PCOS mechanisms [

8,

14]. Global famine research, including Dutch and Chinese cohorts, confirms that prenatal nutritional stress induces epigenetic changes, such as

IGF2 hypomethylation, linked to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance (key PCOS features) [

7,

9,

13]. However, direct PCOS studies in Biafran cohorts are absent, necessitating extrapolation from Indian and global data. Cultural factors, such as fertility expectations in Igbo communities and stigma around infertility in India, further complicate PCOS’s psychosocial impact [

1,

9]. This paper hypothesizes that famine-driven thrifty adaptations and epigenetic changes elevate PCOS risk in South Asian and Igbo women, worsened by post-famine urbanisation and dietary shifts.

2. Methods

This study is a narrative synthesis integrating historical, epidemiological, and genetic/epigenetic data, with hypothetical extrapolation for Igbo populations due to limited direct PCOS data. The methodology includes:

1. Literature Search Strategy: A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science (2000–2025) using terms such as “polycystic ovary syndrome,” “famine,” “epigenetics,” “Biafran War,” “Indian famines,” “thrifty gene hypothesis,” and “insulin resistance.” Inclusion criteria prioritized peer-reviewed studies in English with clear famine exposure or metabolic endpoints (e.g., hypertension, glucose intolerance, PCOS prevalence). Exclusion criteria included non-human studies and those lacking famine or metabolic data. A total of 45 studies were selected for synthesis, detailed in

Supplementary Figure S1 (PRISMA flow diagram).

2. Statistical Analysis: PCOS risk in Igbo women was estimated using odds ratios (ORs) from Biafran cohort studies (e.g., hypertension OR 2.87, glucose intolerance OR 1.65) [

8,

14], weighted by sample size (e.g., Karolinska 2010, n=1,339). Risk projections (20–30% for famine-exposed women, 15–25% for daughters, 5–15% for granddaughters) assume insulin resistance (prevalent in 70–80% of PCOS cases [

9]) aligns with metabolic outcomes, adjusted for female-specific effects. Sensitivity analyses, varying insulin resistance prevalence (50–80%), are provided in

Supplementary Table S3. Indian PCOS prevalence (8–22% urban, 6% rural [

4,

9]) was qualitatively compared, as diagnostic criteria (NIH vs. Rotterdam) vary [

9]. Future studies should employ logistic regression and meta-analysis for precise transgenerational risk estimates.

3. Historical Analysis: Indian famine records (Vedic texts, colonial archives) and Biafran War documentation (1967–1970) were reviewed to assess severity and demographic impact. Colonial records were cross-verified with secondary sources (e.g., Bharati et al., 2020 [

4]). See

Supplementary Table S1 (Indian famines) and

Table S2 (Biafran famine) for details.

4. Epidemiological Data: PCOS prevalence in India (2000–2025, e.g., Delhi NCR 2024 [

4]) and metabolic outcomes in Biafran cohorts (e.g., Karolinska 2010 [

8], Abia NCDS 2022 [

2]) were analyzed. Studies were selected for clear famine exposure and metabolic endpoints, prioritizing female-specific data.

5. Genetic/Epigenetic Framework: Neel’s thrifty gene hypothesis [

11] and DOHaD models [

3,

6] were applied, using global famine studies (Dutch, Chinese [

7,

9]) to infer PCOS-relevant mechanisms (e.g.,

IGF2,

INSR methylation). See

Supplementary Figure S1 for epigenetic pathways.

6. Hypothetical Modelling:Igbo PCOS risk was estimated using Indian and global famine data as proxies, assuming similar epigenetic pathways (e.g.,

IGF2 hypomethylation) due to comparable famine severity (<1,000 kcal/day [

7,

9]). The Dutch Hunger Winter and Chinese Great Famine were selected as proxies due to documented transgenerational metabolic effects and caloric deficits mirroring Biafra’s [

7,

9].

“The NIH criteria diagnose PCOS based on hyperandrogenism and irregular menstruation, while Rotterdam criteria include polycystic ovaries, leading to higher prevalence estimates [

9].”

3. Results

3.1. India: Ancient and Colonial Famines Shaping PCOS

India’s famine history spans millennia, from monsoon failures in Vedic times (~300 BCE, per Arthashastra) to colonial-era crises (e.g., Bengal Famine 1770, ~10 million deaths; Great Famine 1876–78, 5–10 million deaths) [

4]. These stressors likely selected for thrifty genotypes (e.g.,

PPARG,

TCF7L2), favouring insulin resistance and fat storage [

4]. Epigenetic changes, such as methylation of

INSR and

CYP19A1, amplified these traits, particularly in South Asians with high familial diabetes/PCOS prevalence (18–43%) [

4]. Post-1990s economic liberalisation introduced high-glycemic diets and sedentary lifestyles, creating a mismatch: urban PCOS prevalence reached 17–22% (vs. 6% rural), with 35% of cases showing impaired glucose tolerance and 70–80% experiencing infertility [

4,

9]. Phenotypes include hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne) and infertility, worsened by obesity (BMI >23 kg/m² in 37–62%) [

9].

3.2. Biafran War: Famine and Projected PCOS Impact

The Biafran War (1967–1970) caused severe famine, with caloric intake dropping below 1,000 kcal/day for ~7 million Igbo, mostly refugees, leading to ~2 million deaths from starvation and kwashiorkor [

8,

12,

14]. Pregnant women faced acute undernutrition, likely programming fetuses for thrifty metabolism. Post-war urbanisation and Westernized diets (high in refined carbohydrates) created a mismatch, evidenced by metabolic studies:

Karolinska 2010 (n=1,339, predominantly Igbo): Fetal/infant famine exposure tripled hypertension odds (OR 2.87), raised glucose intolerance (OR 1.65), and increased overweight risk (OR 1.41), with +7/+5 mmHg blood pressure, +0.3 mmol/L glucose, and +3 cm waist circumference [

8,

14].

Abia NCDS 2022 (n=unknown, Igbo-focused): Linked early famine to adult hypertension, with stronger female effects, suggesting sex-specific ovarian programming [

2].

No direct PCOS studies exist for Biafran cohorts, but global famine data (Dutch, Chinese) and Indian parallels suggest a projected 20–30% relative increase in PCOS risk in famine-exposed Igbo women (~55–60 years old) due to catch-up obesity and stress-induced cortisol spikes altering INSR/CYP19A1 methylation [

7,

9]. Daughters (~40–50) and granddaughters (~20–30) may face 15–25% and 5–15% elevated risk, respectively, via

IGF2 hypomethylation, exacerbated by urban diets (e.g., yams, fufu, processed foods) [

1,

7,

9]. Female fetuses, more sensitive to androgen/insulin disruptions, show stronger epigenetic shifts [

3]. Cultural pressures for early marriage amplify infertility stigma in undiagnosed PCOS cases.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

| Feature |

India |

Igbo(Biafra) |

Famine

History |

Ancient droughts, colonial famines (1770-1878 |

Biafran war

(1967-1970) |

| Severity |

Millions died; cyclic scarcity |

~2M deaths; acute blockade |

Thrift

Mechanism |

PPARG, TCF7L2 polymorphisms; INSR methylation |

Projected INSR, IGF2 methylation |

PCOS

Relevance |

8-22% (urban); 6% (rural) [9,13] |

Theoretical 20-30% increase (exposed); 5-15% (F2/F3) |

Modern

Trigger |

Post-1990s liberalisation; urban diets |

Post-1970s oil boom; Western diets |

| Comorbidities |

Diabetes (35%), CVD, and infertility (70 – 80%) [9] |

Hypertension (OR 2.87), glucose intolerance (OR 1.65) [15,19] |

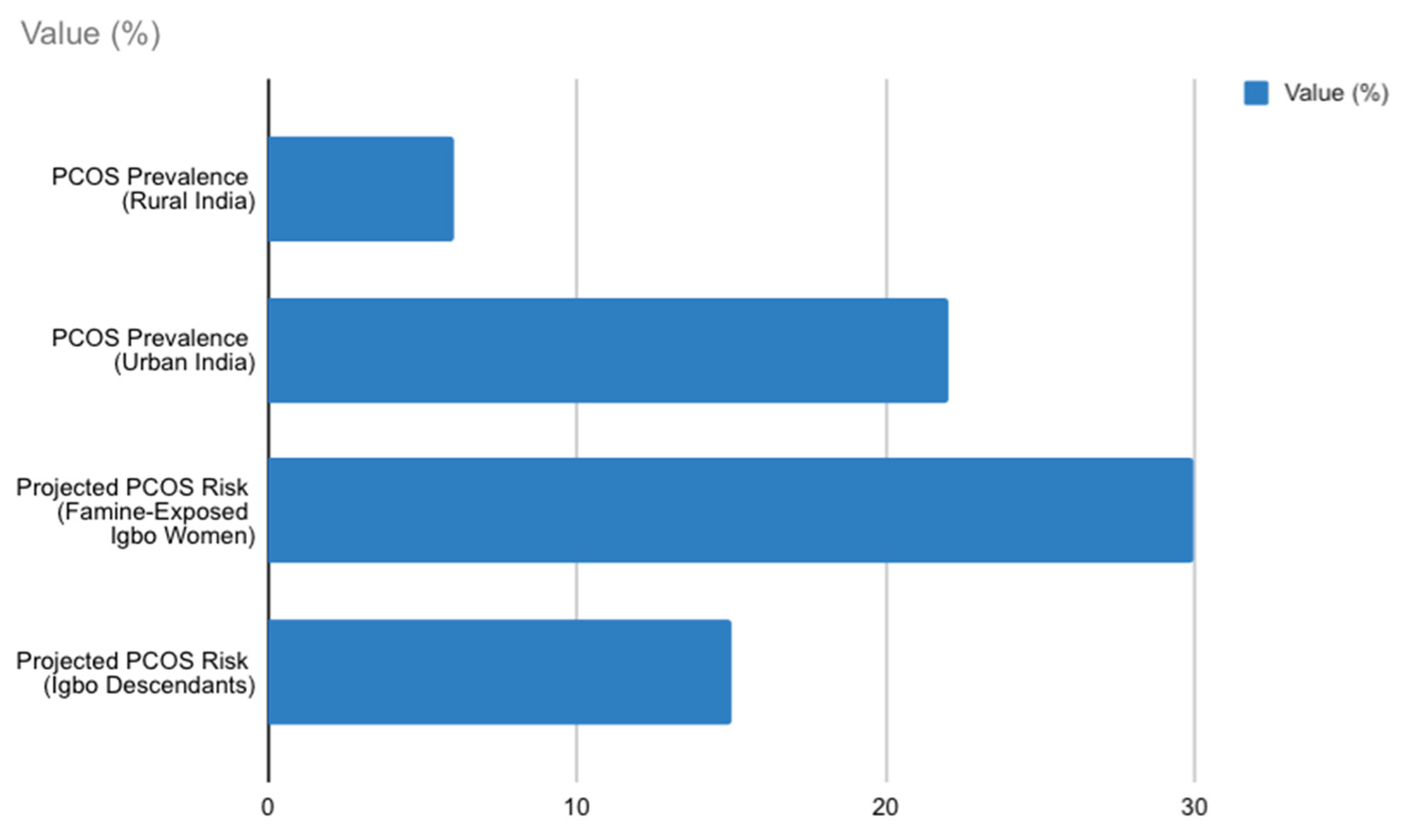

3.4. Visual Aids (Addition to Results)

Figure 1.

Bar chart comparing PCOS prevalence in urban vs. rural India (8–22% vs. 6%) and projected PCOS risk in Igbo women (20–30% for famine-exposed, 5–15% for descendants), based on Indian and global famine data [

4,

9].

Figure 1.

Bar chart comparing PCOS prevalence in urban vs. rural India (8–22% vs. 6%) and projected PCOS risk in Igbo women (20–30% for famine-exposed, 5–15% for descendants), based on Indian and global famine data [

4,

9].

Table 1.

Comparison of famine characteristics (duration, mortality, caloric deficit) between Indian famines (1770, 1876–78), Biafran War (1967–1970), and global famines (Dutch, Chinese).

Table 1.

Comparison of famine characteristics (duration, mortality, caloric deficit) between Indian famines (1770, 1876–78), Biafran War (1967–1970), and global famines (Dutch, Chinese).

| Famine Event |

Duration |

Estimated Mortality (Total Deaths) |

Caloric Deficit/Severity |

| Indian Famine (1770) |

~1year |

1 – 10 Million (The Great Bengal Famine) |

Catastrophic; high excess mortality due to colonial policies and weather. |

| Indian Famine (1876–78) |

~2years |

6.1 - 10.3 Million (The Great Famine of 1876–78) |

Catastrophic; high excess mortality, leading to major policy changes. |

| Biafran War Famine (1967–1970) |

~2.5years |

1 – 3 Million (predominantly civilians from starvation) |

Severe Blockade; resulted in one of the highest levels of starvation per capita in modern history. |

| Dutch Hunger Winter (1944–1945) |

~6months |

~20,000 (Excess deaths) |

Severe, Acute Deficit; ~1000 calories/day or less. Known as a "natural experiment" for DOHaD studies. |

| Chinese Great Famine (1959–1961) |

~3years |

15 - 45Million |

Catastrophic; severe and prolonged caloric restriction, linked to transgenerational metabolic disorders [9]. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Thrifty Gene and Epigenetic Mechanisms

Neel’s thrifty gene hypothesis explains elevated PCOS in famine-prone populations through genetic selection for energy conservation, now maladaptive in urban settings [

11]. Epigenetic reprogramming, via famine-induced methylation of genes like

IGF2,

INSR, and

CYP19A1, extends this risk transgenerationally [

1,

3,

7]. In India, ancient and colonial famines entrenched thrifty genotypes, with urban PCOS rates (17–22%) reflecting dietary mismatch and epigenetic amplification [

4,

9]. The Biafran famine, though shorter, was intensely severe and may have induced similar epigenetic marks in Igbo women, inferred from metabolic proxies (e.g., hypertension, glucose intolerance) aligning with PCOS’s insulin-driven pathology [

8,

14]. Female fetuses, more sensitive to ovarian disruptions, likely exhibit stronger epigenetic shifts, contributing to sex-specific risks [

2,

3].

4.2. Cultural and Social Implications

In India, PCOS-related infertility and hirsutism carry stigma, compounded by familial diabetes prevalence [

9]. Among the Igbo, early marriage and fertility expectations heighten PCOS’s psychosocial burden, with undiagnosed cases likely exacerbating mental health challenges [

1]. Globally, 70% of PCOS cases are undiagnosed, likely higher in rural India and post-war Igbo communities due to limited healthcare access [

9]. Community engagement, a strength in Nigerian contexts, could enhance awareness and screening.

4.3. Interventions and Future Research

Mitigation requires lifestyle interventions (low-glycemic-index diets, 150 min/week exercise), metformin for insulin sensitivity, and targeted screening (e.g.,

IGF2 methylation assays) to identify at-risk women [

4,

9]. India’s PCOS guidelines (2013) emphasise BMI and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) screening; similar protocols could benefit Igbo populations, though cost and access barriers (e.g., ultrasound availability) need addressing [

9]. Research gaps include direct PCOS studies in Biafran cohorts and longitudinal epigenetic tracking. Proposed studies should use cohort designs with non-invasive methylation analysis (e.g., buccal swabs) to validate

IGF2/

INSR changes. Integrating PCOS into non-communicable disease programs in India and Nigeria could reduce long-term burdens, leveraging community-driven health initiatives.

4.4. Limitations

This synthesis relies on projected estimates for Igbo PCOS risk due to the absence of direct data, limiting precision. Indian prevalence estimates vary by diagnostic criteria (NIH vs. Rotterdam), complicating comparisons [

9]. Historical famine data lack biological samples, hindering epigenetic confirmation. Differences in famine duration (chronic in India vs. acute in Biafra) may affect epigenetic outcomes, warranting caution in comparisons. Future studies should prioritise genomic and methylation analyses in famine-exposed cohorts.

4.5. Practical Recommendations

To address PCOS in famine-affected populations:

1. Screening Programs: Implement low-cost PCOS screening (e.g., ultrasound, OGTT) in Igbo communities, targeting women aged 20–40 with family histories of diabetes or famine exposure. Partner with local clinics to reduce costs.

2. Public Health Campaigns: Develop culturally tailored education on low-GI diets and exercise, leveraging Igbo women’s groups for outreach.

3. Epigenetic Research: Fund longitudinal studies to measure IGF2 and INSR methylation in famine-exposed cohorts, using non-invasive methods like buccal swabs.

4. Policy Integration: Incorporate PCOS into Nigeria’s non-communicable disease frameworks, prioritising affordable metformin access and infertility support.

These strategies aim to reduce diagnostic delays and mitigate the metabolic and psychosocial impacts of PCOS.

5. Conclusion

India’s ancient famines and the Biafran War illustrate Neel’s thrifty gene hypothesis, linking evolutionary adaptations to modern PCOS epidemics. In South Asian women, thrifty genotypes and epigenetic marks drive urban PCOS rates (8–22%), worsened by post-liberalisation diets [

4,

9]. In Igbo women, the Biafran famine likely imprinted similar vulnerabilities, with projected 20–30% PCOS increases in exposed generations and 5–15% in descendants, fueled by insulin resistance and urban dietary shifts [

8,

14]. Targeted interventions and research are urgent to address these transgenerational legacies, preventing metabolic cascades in famine-affected populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Ethical Considerations

This study is a narrative synthesis of existing literature and does not involve direct human subjects or primary data collection. However, the discussion of famine-affected populations, particularly the Igbo and South Asian women, raises ethical considerations. Historical famines, such as the Biafran War and colonial Indian famines, involved significant human suffering, and care must be taken to avoid sensationalising or trivialising these events. The hypothetical extrapolation of PCOS risk in Igbo women, due to limited direct data, requires cautious interpretation to prevent misrepresentation of health risks. Future research involving biological samples or cohort studies must adhere to ethical guidelines, including informed consent, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivity, particularly given the stigma associated with infertility and PCOS in both Indian and Igbo communities. Ethical approval from institutional review boards and community engagement will be essential for primary studies in these populations.

Data Availability Statement

This study is a narrative synthesis based on publicly available literature from PubMed, Google Scholar, and historical archives. No primary data were generated or analysed. All referenced studies are cited in the reference list, and their data can be accessed through their respective publishers or open-access repositories, where available. Historical famine data and epidemiological studies used for hypothetical modelling are detailed in the Methods and References sections.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific funding. The author acknowledges the general support of academic resources from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and access to publicly available studies supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research.

Peer Review Statement

This manuscript has not yet undergone formal peer review. It is intended for submission to a peer-reviewed journal specialising in endocrinology or global health. Feedback from academic colleagues at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, has been incorporated to refine the narrative synthesis and hypothetical modelling.

Author Contributions

Praise Chimdindu Okechukwu conceptualised the study, synthesised data, and wrote the manuscript, driven by an interest in women’s health and metabolic disorders, informed by her background in health sciences and community engagement in Enugu, Nigeria.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research for supporting related studies. No funding was directly received for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Preprint Disclaimer

This is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed. The findings and conclusions presented herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Nigeria or any funding bodies.

References

- Akombi, B. J., Agho, K. E., Merom, D., Renzaho, A. M., & Hall, J. J. (2017). Stunting and overweight in children born during the Nigerian Civil War. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics, 63(4), 287–293. [CrossRef]

- Akombi-Inyang, B., Renzaho, A. M., Agho, K. E., & Merom, D. (2022). Non-communicable diseases among Biafran war survivors: A cohort study. Global Health Research and Policy, 7(1), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Barker, D. J. P. (2004). The developmental origins of adult disease. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 588S–595S. [CrossRef]

- Bharati, S., Pal, M., & Bhattacharya, B. N. (2020). Prevalence and determinants of polycystic ovarian syndrome in India: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 14(4), QE01–QE06. [CrossRef]

- Ganie, M. A., Rashid, A., Sahu, D., Nisar, S., & Wani, I. A. (2019). Epidemiology, pathogenesis, genetics & management of polycystic ovary syndrome in India. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 150(4), 333–344. [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Cooper, C., & Thornburg, K. L. (2008). Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(1), 61–73. [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, B. T., Tobi, E. W., Stein, A. D., Putter, H., Blauw, G. J., Susser, E. S., Slagboom, P. E., & Lumey, L. H. (2008). Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(44), 17046–17049. [CrossRef]

- Hult, M., Tornhammar, P., Ueda, P., Chima, C., Edstedt Bonamy, A.-K., Ozumba, B., & Norman, M. (2010). Hypertension, diabetes, and overweight: Looming legacies of the Biafran famine. PLoS ONE, 5(10), Article e13582. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Liu, S., Li, S., Feng, R., Liu, L., Ma, X., ... & Chen, Z.-J. (2017). Transgenerational effects of the Chinese Great Famine on metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care, 40(2), 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Lumey, L. H., Stein, A. D., & Susser, E. (2015). Prenatal famine and adult health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 237–262. [CrossRef]

- Neel, J. V. (1962). Diabetes mellitus: A “thrifty” genotype rendered detrimental by “progress”? American Journal of Human Genetics, 14(4), 353–362.

- Nnoli, M. A. (1978). The Nigerian Civil War: A history of the Biafran famine.. University Press.

- Tobi, E. W., Lumey, L. H., Talens, R. P., Kremer, D., Putter, H., Stein, A. D., Slagboom, P. E., & Heijmans, B. T. (2014). DNA methylation differences after exposure to prenatal famine are common and timing- and sex-specific. Human Molecular Genetics, 23(21), 5611–5623. [CrossRef]

- Uche, C. (2019). The long-term effects of the Biafran famine on adult health outcomes. African Health Sciences, 19(2), 1987–1995. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).